User login

Physician sues AMA for defamation over 2022 election controversy

If Willarda Edwards, MD, MBA, had won her 2022 campaign for president-elect of the American Medical Association (AMA), she would have been the second Black woman to head the group.

The lawsuit sheds light on the power dynamics of a politically potent organization that has more than 271,000 members and holds assets of $1.2 billion. The AMA president is one of the most visible figures in American medicine.

“The AMA impugned Dr. Edwards with these false charges, which destroyed her candidacy and irreparably damaged her reputation,” according to the complaint, which was filed Nov. 9, 2022, in Baltimore County Circuit Court. The case was later moved to federal court.

The AMA “previously rejected our attempt to resolve this matter without litigation,” Dr. Edwards’ attorney, Timothy Maloney, told this news organization. An AMA spokesman said the organization had no comment on Dr. Edwards’ suit.

Dr. Edwards is a past president of the National Medical Association, MedChi, the Baltimore City Medical Society, the Monumental City Medical Society, and the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America. She joined the AMA in 1994 and has served as a trustee since 2016.

As chair of the AMA Task Force on Health Equity, “she helped lead the way in consensus building and driving action that in 2019 resulted in the AMA House of Delegates establishing the AMA Center on Health Equity,” according to her AMA bio page.

‘Quid pro quo’ alleged

In June 2022, Dr. Edwards was one of three individuals running to be AMA president-elect.

According to Dr. Edwards’ complaint, she was “incorrectly advised by colleagues” that Virginia urologist William Reha, MD, had decided not to seek the AMA vice-speakership in 2023. This was important because both Dr. Edwards and Dr. Reha were in the Southeastern delegation. It could be in Dr. Edwards’ favor if Dr. Reha was not running, as it would mean one less leadership candidate from the same region.

Dr. Edwards called Dr. Reha on June 6 to discuss the matter. When they talked, Dr. Reha allegedly recorded the call without Dr. Edwards’ knowledge or permission – a felony in Maryland – and also steered her toward discussions about how his decision could benefit her campaign, according to the complaint.

The suit alleges that Dr. Reha’s questions were “clearly calculated to draw some statements by Dr. Edwards that he could use later to thwart her candidacy and to benefit her opponent.”

On June 10, at the AMA’s House of Delegates meeting in Chicago, Dr. Edwards was taken aside and questioned by members of the AMA’s Election Campaign Committee, according to the complaint. They accused her of “vote trading” but did not provide any evidence or a copy of a complaint they said had been filed against her, the suit said.

Dr. Edwards was given no opportunity to produce her own evidence or rebut the accusations, the suit alleges.

Just before the delegates started formal business on June 13, House Speaker Bruce Scott, MD, read a statement to the assembly saying that a complaint of a possible campaign violation had been filed against Dr. Edwards.

Dr. Scott told the delegates that “committee members interviewed the complainant and multiple other individuals said to have knowledge of the circumstances. In addition to conducting multiple interviews, the committee reviewed evidence that was deemed credible and corroborated that a campaign violation did in fact occur,” according to the complaint.

The supposed violation: A “quid pro quo” in which an unnamed delegation would support Dr. Edwards’ current candidacy, and the Southeastern delegation would support a future candidate from that other unnamed delegation.

Dr. Edwards was given a short opportunity to speak, in which she denied any violations.

According to a news report, Dr. Edwards said, “I’ve been in the House of Delegates for 30 years, and you know me as a process person – a person who truly believes in the process and trying to follow the complexities of our election campaign.”

The lawsuit alleges that “this defamatory conduct was repeated the next day to more than 600 delegates just minutes prior to the casting of votes, when Dr Scott repeated these allegations.”

Dr. Edwards lost the election.

AMA: Nothing more to add

The suit alleges that neither the Election Campaign Committee nor the AMA itself has made any accusers or complaints available to Dr. Edwards and that it has not provided any audio or written evidence of her alleged violation.

In July, the AMA’s Southeastern delegation told its membership, “We continue to maintain that Willarda was ‘set up’ ... The whole affair lacked any reasonable semblance of due process.”

The delegation has filed a counter claim against the AMA seeking “to address this lack of due process as well as the reputational harm” to the delegation.

The AMA said that it has nothing it can produce. “The Speaker of the House presented a verbal report to the attending delegates,” said a spokesman. “The Speaker’s report remains the only remarks from an AMA officer, and no additional remarks can be expected at this time.”

He added that there “is no official transcript of the Speaker’s report.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If Willarda Edwards, MD, MBA, had won her 2022 campaign for president-elect of the American Medical Association (AMA), she would have been the second Black woman to head the group.

The lawsuit sheds light on the power dynamics of a politically potent organization that has more than 271,000 members and holds assets of $1.2 billion. The AMA president is one of the most visible figures in American medicine.

“The AMA impugned Dr. Edwards with these false charges, which destroyed her candidacy and irreparably damaged her reputation,” according to the complaint, which was filed Nov. 9, 2022, in Baltimore County Circuit Court. The case was later moved to federal court.

The AMA “previously rejected our attempt to resolve this matter without litigation,” Dr. Edwards’ attorney, Timothy Maloney, told this news organization. An AMA spokesman said the organization had no comment on Dr. Edwards’ suit.

Dr. Edwards is a past president of the National Medical Association, MedChi, the Baltimore City Medical Society, the Monumental City Medical Society, and the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America. She joined the AMA in 1994 and has served as a trustee since 2016.

As chair of the AMA Task Force on Health Equity, “she helped lead the way in consensus building and driving action that in 2019 resulted in the AMA House of Delegates establishing the AMA Center on Health Equity,” according to her AMA bio page.

‘Quid pro quo’ alleged

In June 2022, Dr. Edwards was one of three individuals running to be AMA president-elect.

According to Dr. Edwards’ complaint, she was “incorrectly advised by colleagues” that Virginia urologist William Reha, MD, had decided not to seek the AMA vice-speakership in 2023. This was important because both Dr. Edwards and Dr. Reha were in the Southeastern delegation. It could be in Dr. Edwards’ favor if Dr. Reha was not running, as it would mean one less leadership candidate from the same region.

Dr. Edwards called Dr. Reha on June 6 to discuss the matter. When they talked, Dr. Reha allegedly recorded the call without Dr. Edwards’ knowledge or permission – a felony in Maryland – and also steered her toward discussions about how his decision could benefit her campaign, according to the complaint.

The suit alleges that Dr. Reha’s questions were “clearly calculated to draw some statements by Dr. Edwards that he could use later to thwart her candidacy and to benefit her opponent.”

On June 10, at the AMA’s House of Delegates meeting in Chicago, Dr. Edwards was taken aside and questioned by members of the AMA’s Election Campaign Committee, according to the complaint. They accused her of “vote trading” but did not provide any evidence or a copy of a complaint they said had been filed against her, the suit said.

Dr. Edwards was given no opportunity to produce her own evidence or rebut the accusations, the suit alleges.

Just before the delegates started formal business on June 13, House Speaker Bruce Scott, MD, read a statement to the assembly saying that a complaint of a possible campaign violation had been filed against Dr. Edwards.

Dr. Scott told the delegates that “committee members interviewed the complainant and multiple other individuals said to have knowledge of the circumstances. In addition to conducting multiple interviews, the committee reviewed evidence that was deemed credible and corroborated that a campaign violation did in fact occur,” according to the complaint.

The supposed violation: A “quid pro quo” in which an unnamed delegation would support Dr. Edwards’ current candidacy, and the Southeastern delegation would support a future candidate from that other unnamed delegation.

Dr. Edwards was given a short opportunity to speak, in which she denied any violations.

According to a news report, Dr. Edwards said, “I’ve been in the House of Delegates for 30 years, and you know me as a process person – a person who truly believes in the process and trying to follow the complexities of our election campaign.”

The lawsuit alleges that “this defamatory conduct was repeated the next day to more than 600 delegates just minutes prior to the casting of votes, when Dr Scott repeated these allegations.”

Dr. Edwards lost the election.

AMA: Nothing more to add

The suit alleges that neither the Election Campaign Committee nor the AMA itself has made any accusers or complaints available to Dr. Edwards and that it has not provided any audio or written evidence of her alleged violation.

In July, the AMA’s Southeastern delegation told its membership, “We continue to maintain that Willarda was ‘set up’ ... The whole affair lacked any reasonable semblance of due process.”

The delegation has filed a counter claim against the AMA seeking “to address this lack of due process as well as the reputational harm” to the delegation.

The AMA said that it has nothing it can produce. “The Speaker of the House presented a verbal report to the attending delegates,” said a spokesman. “The Speaker’s report remains the only remarks from an AMA officer, and no additional remarks can be expected at this time.”

He added that there “is no official transcript of the Speaker’s report.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If Willarda Edwards, MD, MBA, had won her 2022 campaign for president-elect of the American Medical Association (AMA), she would have been the second Black woman to head the group.

The lawsuit sheds light on the power dynamics of a politically potent organization that has more than 271,000 members and holds assets of $1.2 billion. The AMA president is one of the most visible figures in American medicine.

“The AMA impugned Dr. Edwards with these false charges, which destroyed her candidacy and irreparably damaged her reputation,” according to the complaint, which was filed Nov. 9, 2022, in Baltimore County Circuit Court. The case was later moved to federal court.

The AMA “previously rejected our attempt to resolve this matter without litigation,” Dr. Edwards’ attorney, Timothy Maloney, told this news organization. An AMA spokesman said the organization had no comment on Dr. Edwards’ suit.

Dr. Edwards is a past president of the National Medical Association, MedChi, the Baltimore City Medical Society, the Monumental City Medical Society, and the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America. She joined the AMA in 1994 and has served as a trustee since 2016.

As chair of the AMA Task Force on Health Equity, “she helped lead the way in consensus building and driving action that in 2019 resulted in the AMA House of Delegates establishing the AMA Center on Health Equity,” according to her AMA bio page.

‘Quid pro quo’ alleged

In June 2022, Dr. Edwards was one of three individuals running to be AMA president-elect.

According to Dr. Edwards’ complaint, she was “incorrectly advised by colleagues” that Virginia urologist William Reha, MD, had decided not to seek the AMA vice-speakership in 2023. This was important because both Dr. Edwards and Dr. Reha were in the Southeastern delegation. It could be in Dr. Edwards’ favor if Dr. Reha was not running, as it would mean one less leadership candidate from the same region.

Dr. Edwards called Dr. Reha on June 6 to discuss the matter. When they talked, Dr. Reha allegedly recorded the call without Dr. Edwards’ knowledge or permission – a felony in Maryland – and also steered her toward discussions about how his decision could benefit her campaign, according to the complaint.

The suit alleges that Dr. Reha’s questions were “clearly calculated to draw some statements by Dr. Edwards that he could use later to thwart her candidacy and to benefit her opponent.”

On June 10, at the AMA’s House of Delegates meeting in Chicago, Dr. Edwards was taken aside and questioned by members of the AMA’s Election Campaign Committee, according to the complaint. They accused her of “vote trading” but did not provide any evidence or a copy of a complaint they said had been filed against her, the suit said.

Dr. Edwards was given no opportunity to produce her own evidence or rebut the accusations, the suit alleges.

Just before the delegates started formal business on June 13, House Speaker Bruce Scott, MD, read a statement to the assembly saying that a complaint of a possible campaign violation had been filed against Dr. Edwards.

Dr. Scott told the delegates that “committee members interviewed the complainant and multiple other individuals said to have knowledge of the circumstances. In addition to conducting multiple interviews, the committee reviewed evidence that was deemed credible and corroborated that a campaign violation did in fact occur,” according to the complaint.

The supposed violation: A “quid pro quo” in which an unnamed delegation would support Dr. Edwards’ current candidacy, and the Southeastern delegation would support a future candidate from that other unnamed delegation.

Dr. Edwards was given a short opportunity to speak, in which she denied any violations.

According to a news report, Dr. Edwards said, “I’ve been in the House of Delegates for 30 years, and you know me as a process person – a person who truly believes in the process and trying to follow the complexities of our election campaign.”

The lawsuit alleges that “this defamatory conduct was repeated the next day to more than 600 delegates just minutes prior to the casting of votes, when Dr Scott repeated these allegations.”

Dr. Edwards lost the election.

AMA: Nothing more to add

The suit alleges that neither the Election Campaign Committee nor the AMA itself has made any accusers or complaints available to Dr. Edwards and that it has not provided any audio or written evidence of her alleged violation.

In July, the AMA’s Southeastern delegation told its membership, “We continue to maintain that Willarda was ‘set up’ ... The whole affair lacked any reasonable semblance of due process.”

The delegation has filed a counter claim against the AMA seeking “to address this lack of due process as well as the reputational harm” to the delegation.

The AMA said that it has nothing it can produce. “The Speaker of the House presented a verbal report to the attending delegates,” said a spokesman. “The Speaker’s report remains the only remarks from an AMA officer, and no additional remarks can be expected at this time.”

He added that there “is no official transcript of the Speaker’s report.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mothers with disabilities less likely to start breastfeeding

Mothers with intellectual or developmental disabilities are less likely to initiate breastfeeding and to receive in-hospital breastfeeding support than are those without a disability, new data suggest.

In a population-based cohort study of more than 600,000 mothers, patients with an intellectual or developmental disability were about 18% less likely to have a chance to initiate breastfeeding during their hospital stay.

“Overall, we did see lower rates of breastfeeding practices and supports in people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, as well as those with multiple disabilities, compared to people without disabilities,” study author Hilary K. Brown, PhD, assistant professor of health and society at University of Toronto Scarborough in Ontario, told this news organization.

The study was published in The Lancet Public Health.

Disparities in breastfeeding

“There hasn’t been a lot of research on breastfeeding outcomes in people with disabilities,” said Dr. Brown, who noted that the study outcomes were based on the WHO-UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative guidelines. “There have been a number of qualitative studies that have suggested that they do experience barriers accessing care related to breastfeeding and different challenges related to breastfeeding. But as far as quantitative outcomes, there has only been a handful of studies.”

To examine these outcomes, the investigators analyzed health administrative data from Ontario. They included in their analysis all birthing parents aged 15-49 years who had a single live birth between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2018. Patients with a physical disability, sensory disability, intellectual or developmental disability, or two or more disabilities were identified via diagnostic algorithms and were compared with individuals without disabilities with respect to the opportunity to initiate breastfeeding, to engage in in-hospital breastfeeding, to engage in exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge, to have skin-to-skin contact, and to be provided with breastfeeding assistance.

The investigators considered a physical disability to encompass conditions such as congenital anomalies, musculoskeletal disorders, neurologic disorders, or permanent injuries. They defined sensory disability as hearing loss or vision loss. Intellectual or developmental disability was defined as having autism spectrum disorder, chromosomal anomaly, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, or other intellectual disability. Patients with multiple disabilities had two or more of these conditions.

The study population included 634,111 birthing parents, of whom 54,476 (8.6%) had a physical disability, 19,227 (3.0%) had a sensory disability, 1,048 (0.2%) had an intellectual or developmental disability, 4,050 (0.6%) had multiple disabilities, and 555,310 (87.6%) had no disability.

The investigators found that patients with intellectual or developmental disabilities were less likely than were those without a disability to have an opportunity to initiate breastfeeding (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 0.82), to engage in any in-hospital breastfeeding (aRR, 0.85), to be breastfeeding exclusively at hospital discharge (aRR, 0.73), to have skin-to-skin contact (aRR, 0.90), and to receive breastfeeding assistance (aRR, 0.85) compared with patients without a disability.

They also found that individuals with multiple disabilities were less likely to have an opportunity to initiate breastfeeding (aRR, 0.93), to engage in any in-hospital breastfeeding (aRR, 0.93), to be exclusively breastfeeding at hospital discharge (aRR, 0.90), to have skin-to-skin contact (aRR, 0.93), and to receive breastfeeding assistance (aRR, 0.95) compared with patients without a disability.

An understudied population

Commenting on the study, Lori Feldman-Winter, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Rowan University in Camden, N.J., said that one of its strengths is that it included patients who may be excluded from studies of breastfeeding practices. The finding of few differences in breastfeeding practices and supports for people with physical and sensory disabilities, compared with those without disabilities, was positive, she added.

“This is an understudied population, and it is important to call out that there may be practices related to breastfeeding care that suffer, due to implicit bias regarding persons with intellectual and multiple disabilities,” said Dr. Feldman-Winter. “The good news is that other disabilities did not show the same disparities. This study also shows how important it is to measure potential gaps in care across multiple sociodemographic and other variables, such as disabilities, to ensure equitable and inclusive care.”

Health care professionals need to be aware of disparities in breastfeeding care, she added. They need to be open to exploring potential biases when it comes to providing equitable care.

R. Douglas Wilson, MD, president of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and professor emeritus of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Calgary in Alberta, noted that the size of the cohort represents a strength of the study and that the findings suggest the possible need for closer follow-up of a new mother who is breastfeeding and who has an intellectual disability or multiple disabilities.

“You might keep that patient in hospital for an extra day, and then the home care nurse may look in on them more frequently than they would for someone who does not need that extra oversight,” said Dr. Wilson. When their patients are pregnant, obstetricians and gynecologists can find out whether their patients intend to breastfeed and put them in touch with nurses or lactation consultants to assist them, he added.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Canada Research Chairs Program. Dr. Brown, Dr. Feldman-Winter, and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mothers with intellectual or developmental disabilities are less likely to initiate breastfeeding and to receive in-hospital breastfeeding support than are those without a disability, new data suggest.

In a population-based cohort study of more than 600,000 mothers, patients with an intellectual or developmental disability were about 18% less likely to have a chance to initiate breastfeeding during their hospital stay.

“Overall, we did see lower rates of breastfeeding practices and supports in people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, as well as those with multiple disabilities, compared to people without disabilities,” study author Hilary K. Brown, PhD, assistant professor of health and society at University of Toronto Scarborough in Ontario, told this news organization.

The study was published in The Lancet Public Health.

Disparities in breastfeeding

“There hasn’t been a lot of research on breastfeeding outcomes in people with disabilities,” said Dr. Brown, who noted that the study outcomes were based on the WHO-UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative guidelines. “There have been a number of qualitative studies that have suggested that they do experience barriers accessing care related to breastfeeding and different challenges related to breastfeeding. But as far as quantitative outcomes, there has only been a handful of studies.”

To examine these outcomes, the investigators analyzed health administrative data from Ontario. They included in their analysis all birthing parents aged 15-49 years who had a single live birth between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2018. Patients with a physical disability, sensory disability, intellectual or developmental disability, or two or more disabilities were identified via diagnostic algorithms and were compared with individuals without disabilities with respect to the opportunity to initiate breastfeeding, to engage in in-hospital breastfeeding, to engage in exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge, to have skin-to-skin contact, and to be provided with breastfeeding assistance.

The investigators considered a physical disability to encompass conditions such as congenital anomalies, musculoskeletal disorders, neurologic disorders, or permanent injuries. They defined sensory disability as hearing loss or vision loss. Intellectual or developmental disability was defined as having autism spectrum disorder, chromosomal anomaly, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, or other intellectual disability. Patients with multiple disabilities had two or more of these conditions.

The study population included 634,111 birthing parents, of whom 54,476 (8.6%) had a physical disability, 19,227 (3.0%) had a sensory disability, 1,048 (0.2%) had an intellectual or developmental disability, 4,050 (0.6%) had multiple disabilities, and 555,310 (87.6%) had no disability.

The investigators found that patients with intellectual or developmental disabilities were less likely than were those without a disability to have an opportunity to initiate breastfeeding (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 0.82), to engage in any in-hospital breastfeeding (aRR, 0.85), to be breastfeeding exclusively at hospital discharge (aRR, 0.73), to have skin-to-skin contact (aRR, 0.90), and to receive breastfeeding assistance (aRR, 0.85) compared with patients without a disability.

They also found that individuals with multiple disabilities were less likely to have an opportunity to initiate breastfeeding (aRR, 0.93), to engage in any in-hospital breastfeeding (aRR, 0.93), to be exclusively breastfeeding at hospital discharge (aRR, 0.90), to have skin-to-skin contact (aRR, 0.93), and to receive breastfeeding assistance (aRR, 0.95) compared with patients without a disability.

An understudied population

Commenting on the study, Lori Feldman-Winter, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Rowan University in Camden, N.J., said that one of its strengths is that it included patients who may be excluded from studies of breastfeeding practices. The finding of few differences in breastfeeding practices and supports for people with physical and sensory disabilities, compared with those without disabilities, was positive, she added.

“This is an understudied population, and it is important to call out that there may be practices related to breastfeeding care that suffer, due to implicit bias regarding persons with intellectual and multiple disabilities,” said Dr. Feldman-Winter. “The good news is that other disabilities did not show the same disparities. This study also shows how important it is to measure potential gaps in care across multiple sociodemographic and other variables, such as disabilities, to ensure equitable and inclusive care.”

Health care professionals need to be aware of disparities in breastfeeding care, she added. They need to be open to exploring potential biases when it comes to providing equitable care.

R. Douglas Wilson, MD, president of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and professor emeritus of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Calgary in Alberta, noted that the size of the cohort represents a strength of the study and that the findings suggest the possible need for closer follow-up of a new mother who is breastfeeding and who has an intellectual disability or multiple disabilities.

“You might keep that patient in hospital for an extra day, and then the home care nurse may look in on them more frequently than they would for someone who does not need that extra oversight,” said Dr. Wilson. When their patients are pregnant, obstetricians and gynecologists can find out whether their patients intend to breastfeed and put them in touch with nurses or lactation consultants to assist them, he added.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Canada Research Chairs Program. Dr. Brown, Dr. Feldman-Winter, and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mothers with intellectual or developmental disabilities are less likely to initiate breastfeeding and to receive in-hospital breastfeeding support than are those without a disability, new data suggest.

In a population-based cohort study of more than 600,000 mothers, patients with an intellectual or developmental disability were about 18% less likely to have a chance to initiate breastfeeding during their hospital stay.

“Overall, we did see lower rates of breastfeeding practices and supports in people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, as well as those with multiple disabilities, compared to people without disabilities,” study author Hilary K. Brown, PhD, assistant professor of health and society at University of Toronto Scarborough in Ontario, told this news organization.

The study was published in The Lancet Public Health.

Disparities in breastfeeding

“There hasn’t been a lot of research on breastfeeding outcomes in people with disabilities,” said Dr. Brown, who noted that the study outcomes were based on the WHO-UNICEF Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative guidelines. “There have been a number of qualitative studies that have suggested that they do experience barriers accessing care related to breastfeeding and different challenges related to breastfeeding. But as far as quantitative outcomes, there has only been a handful of studies.”

To examine these outcomes, the investigators analyzed health administrative data from Ontario. They included in their analysis all birthing parents aged 15-49 years who had a single live birth between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2018. Patients with a physical disability, sensory disability, intellectual or developmental disability, or two or more disabilities were identified via diagnostic algorithms and were compared with individuals without disabilities with respect to the opportunity to initiate breastfeeding, to engage in in-hospital breastfeeding, to engage in exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge, to have skin-to-skin contact, and to be provided with breastfeeding assistance.

The investigators considered a physical disability to encompass conditions such as congenital anomalies, musculoskeletal disorders, neurologic disorders, or permanent injuries. They defined sensory disability as hearing loss or vision loss. Intellectual or developmental disability was defined as having autism spectrum disorder, chromosomal anomaly, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, or other intellectual disability. Patients with multiple disabilities had two or more of these conditions.

The study population included 634,111 birthing parents, of whom 54,476 (8.6%) had a physical disability, 19,227 (3.0%) had a sensory disability, 1,048 (0.2%) had an intellectual or developmental disability, 4,050 (0.6%) had multiple disabilities, and 555,310 (87.6%) had no disability.

The investigators found that patients with intellectual or developmental disabilities were less likely than were those without a disability to have an opportunity to initiate breastfeeding (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 0.82), to engage in any in-hospital breastfeeding (aRR, 0.85), to be breastfeeding exclusively at hospital discharge (aRR, 0.73), to have skin-to-skin contact (aRR, 0.90), and to receive breastfeeding assistance (aRR, 0.85) compared with patients without a disability.

They also found that individuals with multiple disabilities were less likely to have an opportunity to initiate breastfeeding (aRR, 0.93), to engage in any in-hospital breastfeeding (aRR, 0.93), to be exclusively breastfeeding at hospital discharge (aRR, 0.90), to have skin-to-skin contact (aRR, 0.93), and to receive breastfeeding assistance (aRR, 0.95) compared with patients without a disability.

An understudied population

Commenting on the study, Lori Feldman-Winter, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Rowan University in Camden, N.J., said that one of its strengths is that it included patients who may be excluded from studies of breastfeeding practices. The finding of few differences in breastfeeding practices and supports for people with physical and sensory disabilities, compared with those without disabilities, was positive, she added.

“This is an understudied population, and it is important to call out that there may be practices related to breastfeeding care that suffer, due to implicit bias regarding persons with intellectual and multiple disabilities,” said Dr. Feldman-Winter. “The good news is that other disabilities did not show the same disparities. This study also shows how important it is to measure potential gaps in care across multiple sociodemographic and other variables, such as disabilities, to ensure equitable and inclusive care.”

Health care professionals need to be aware of disparities in breastfeeding care, she added. They need to be open to exploring potential biases when it comes to providing equitable care.

R. Douglas Wilson, MD, president of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and professor emeritus of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Calgary in Alberta, noted that the size of the cohort represents a strength of the study and that the findings suggest the possible need for closer follow-up of a new mother who is breastfeeding and who has an intellectual disability or multiple disabilities.

“You might keep that patient in hospital for an extra day, and then the home care nurse may look in on them more frequently than they would for someone who does not need that extra oversight,” said Dr. Wilson. When their patients are pregnant, obstetricians and gynecologists can find out whether their patients intend to breastfeed and put them in touch with nurses or lactation consultants to assist them, he added.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Canada Research Chairs Program. Dr. Brown, Dr. Feldman-Winter, and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET PUBLIC HEALTH

Black Veterans Disproportionately Denied VA Benefits

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

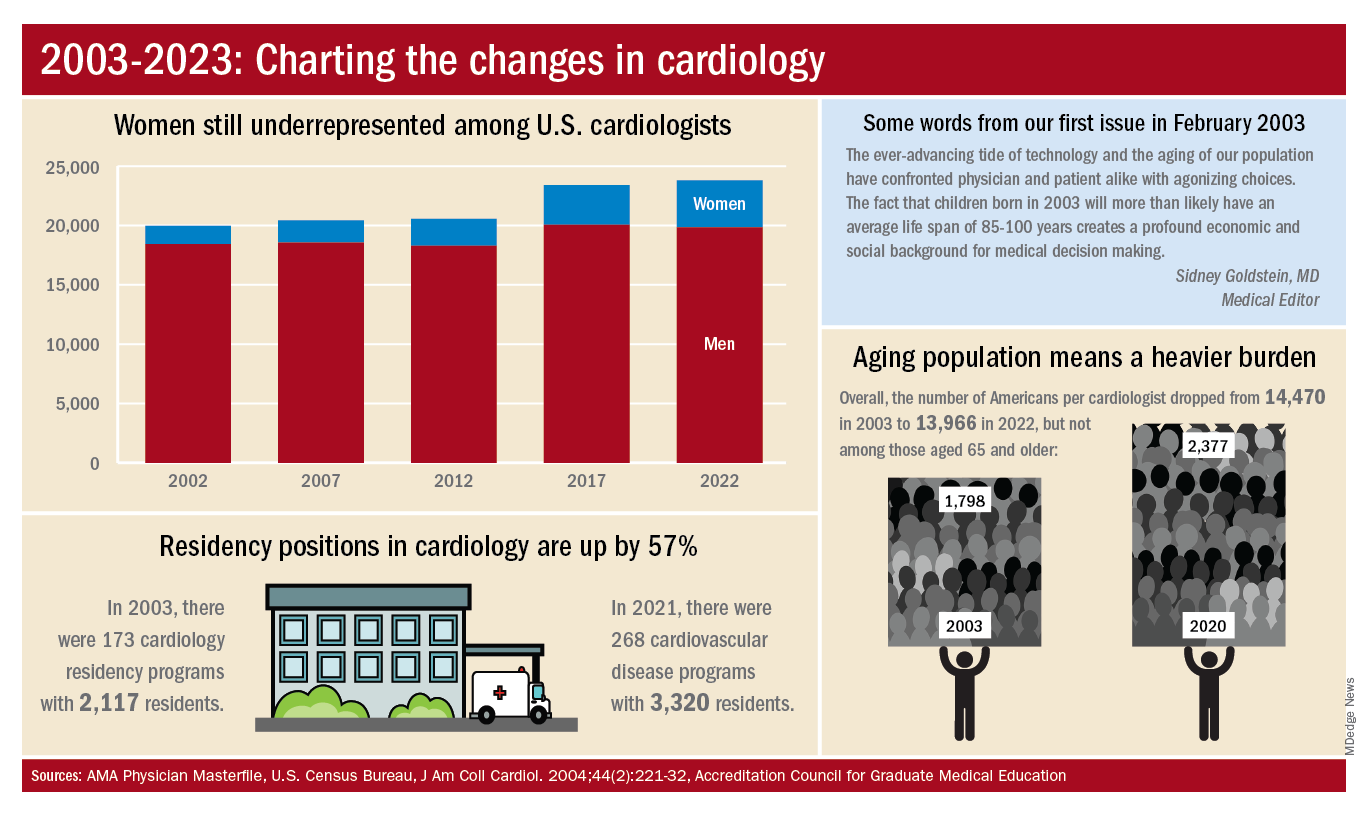

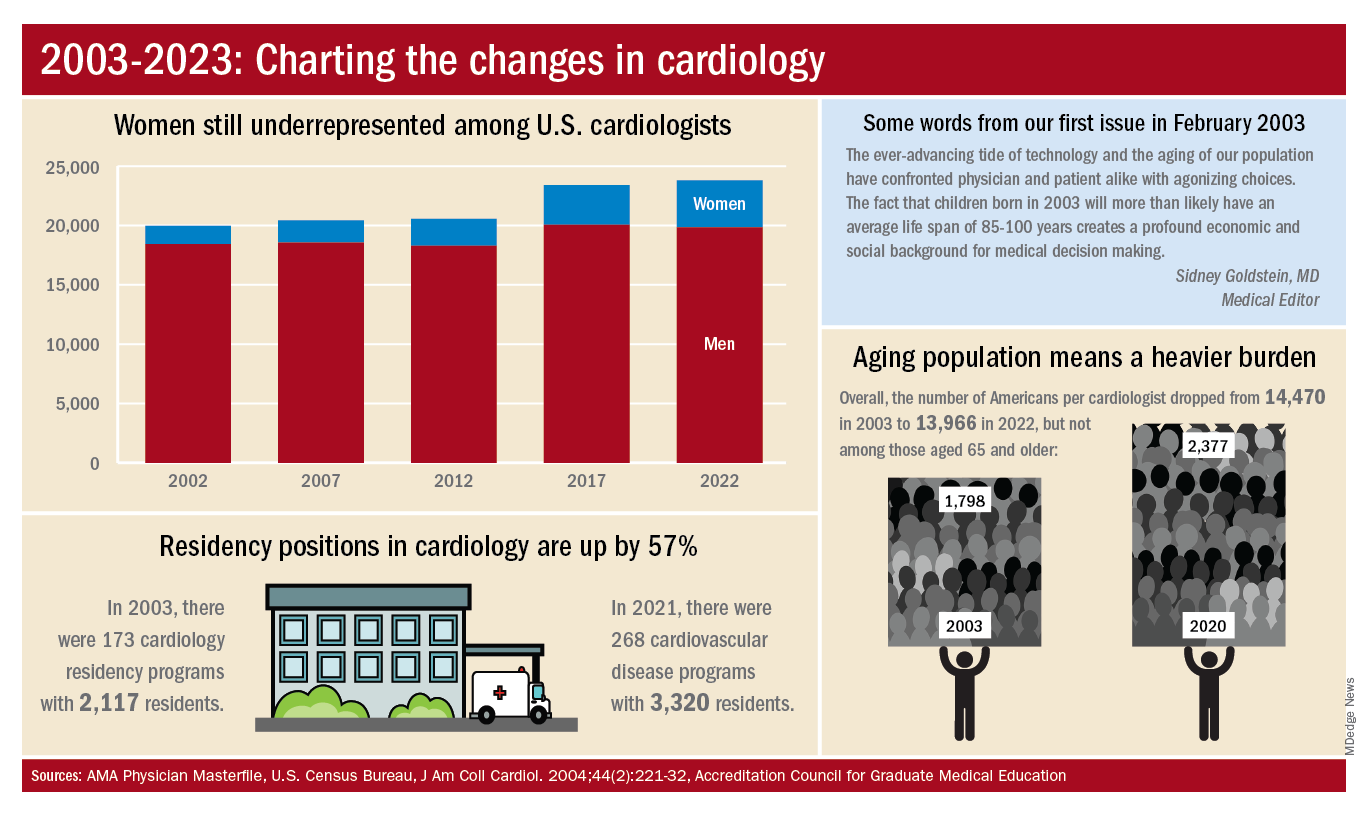

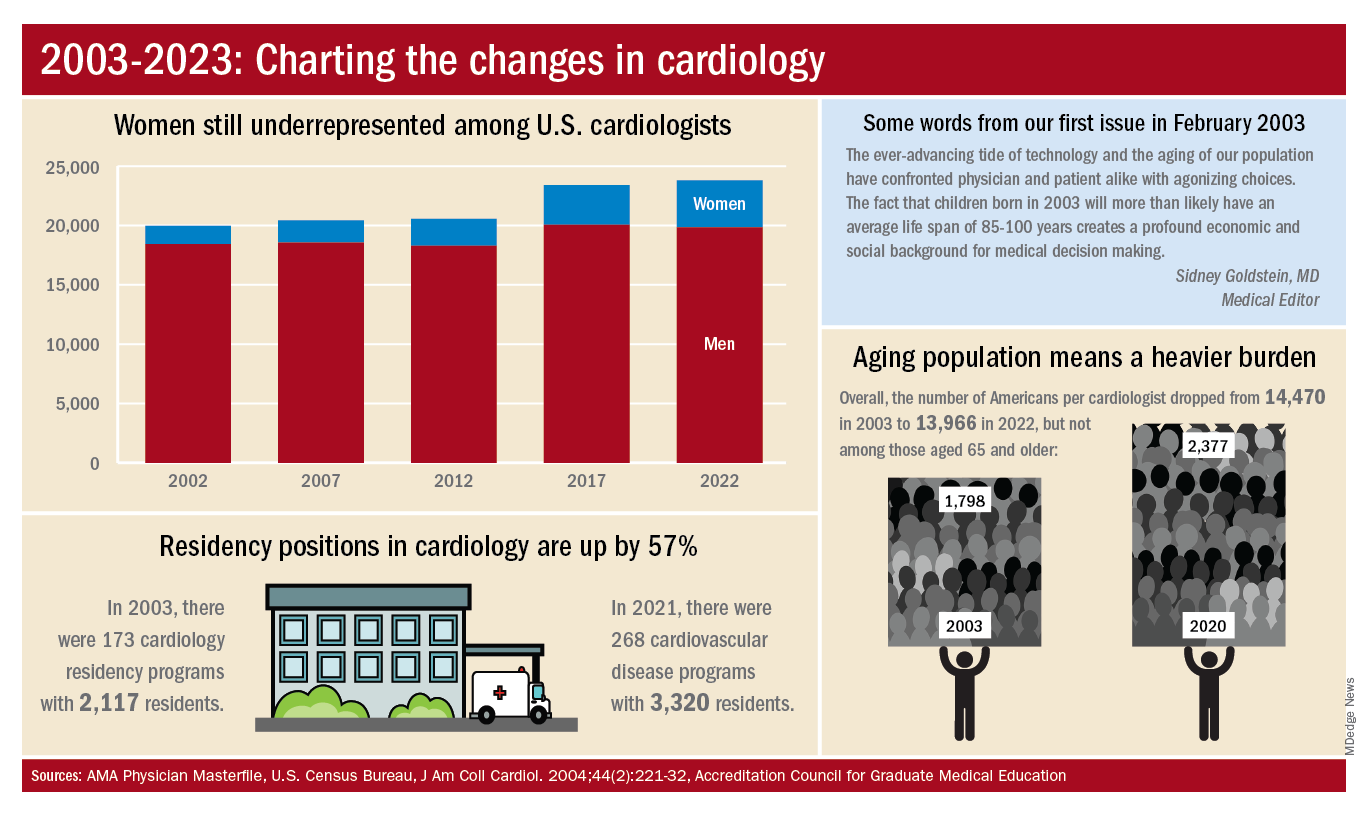

By the numbers: Cardiology slow to add women, IMGs join more quickly

Despite Mark Twain’s assertion that “there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics,” we’re going to dive into 20 years’ worth of data and, hopefully, come up with a few statistics that shed some light on the specialty’s workforce since Cardiology News published its first issue in February 2003.

We start with a major issue over these last 20 years: The participation of women in the specialty.

Back in July of 2002, just a few months before the first issue of Cardiology News was published, W. Bruce Fye, MD, then-president of the American College of Cardiology, wrote, “We need to do more to attract female medical graduates to our specialty because they represent almost one-half of the new doctors trained in this country. Cardiology needs to take full advantage of this large talent pool”

Data from the American Medical Association confirm that assertion: Of the nearly 20,000 postgraduate cardiologists in practice that year, only 7.8% were women. And that was at a time when more than 42% of medical school graduates were women, Dr. Fye noted, while also pointing out that “only 10% of cardiology trainees are female, and just 6% of ACC fellows are women.”

The gap between men and women has closed somewhat in the last 20 years, but the specialty continues to lag behind the profession as a whole. Women represented 16.7% of cardiologists in 2022, versus 37% of physicians overall, AMA data show. In 2019, for the first time, the majority of U.S. medical school students (50.5%) were women, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

A look at residency numbers from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education shows that continued slow improvement in the number of women can be expected, as 25.5% of cardiovascular disease residents were women during the 2021-2022 academic year. Only 2 of the 19 other internal medicine subspecialties were lower, and they happened to be interventional cardiology (20.1%) and clinical cardiac electrophysiology (14.5%).

When men are added to the mix, cardiovascular disease had a total of 3,320 active residents training in 268 programs in 2021-2022, making it the largest of the IM subspecialties in both respects. The resident total is up 57% since 2003, when it came in at 2,117, while programs have increased 55% from the 173 that were operating 2 decades ago. During the year in the middle (2011-2012), there were 2,521 residents in 187 programs, so a larger share of the growth has occurred in the last 10 years, the ACGME data indicate.

The shortage of cardiologists that Dr. Fye and others wrote about 20 years ago has not gone away. A 2018 report from health consulting firm PYA noted the increase in obesity and the low number of medical school graduates choosing the specialty. “Older and fewer physicians specializing in cardiology, coupled with the aging of baby boomers and gravitation toward practice in urban areas, will continue to exacerbate shortages in physician services in the specialty of cardiology, especially in rural areas, over the next decade,” PYA principal Lyle Oelrich wrote.

A little math appears to back up the claims of a cardiologist shortage. Based on census figures for the U.S. population in 2003, there were 14,470 Americans for each of the cardiologists reported by the AMA. That figure dropped to 13,966 by 2022, which seems like an improvement, but it comes with a caveat. The number of Americans aged 65 years and older increased from 1,798 to 2,377 per cardiologist as of 2020, the latest year for which population data were available by age.

One source of growth in the cardiology workforce has been perhaps its most significant minority: international medical graduates. Even by 2004, IMGs represented a much larger segment of all cardiologists (30.0%) than did women (9.3%), based on AMA data. To put it another way, there were more IMGs specializing in cardiovascular disease (6,615) in 2004 than there were women (3,963) in 2022.

The latest data on cardiology training programs – overall numbers were not available – put IMGs at 39.2% for the 2019-2020 academic year. The 2022 fellowship match provides a slightly smaller proportion of IMGs (37.4%) filling cardiovascular disease positions, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

Despite Mark Twain’s assertion that “there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics,” we’re going to dive into 20 years’ worth of data and, hopefully, come up with a few statistics that shed some light on the specialty’s workforce since Cardiology News published its first issue in February 2003.

We start with a major issue over these last 20 years: The participation of women in the specialty.

Back in July of 2002, just a few months before the first issue of Cardiology News was published, W. Bruce Fye, MD, then-president of the American College of Cardiology, wrote, “We need to do more to attract female medical graduates to our specialty because they represent almost one-half of the new doctors trained in this country. Cardiology needs to take full advantage of this large talent pool”

Data from the American Medical Association confirm that assertion: Of the nearly 20,000 postgraduate cardiologists in practice that year, only 7.8% were women. And that was at a time when more than 42% of medical school graduates were women, Dr. Fye noted, while also pointing out that “only 10% of cardiology trainees are female, and just 6% of ACC fellows are women.”

The gap between men and women has closed somewhat in the last 20 years, but the specialty continues to lag behind the profession as a whole. Women represented 16.7% of cardiologists in 2022, versus 37% of physicians overall, AMA data show. In 2019, for the first time, the majority of U.S. medical school students (50.5%) were women, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

A look at residency numbers from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education shows that continued slow improvement in the number of women can be expected, as 25.5% of cardiovascular disease residents were women during the 2021-2022 academic year. Only 2 of the 19 other internal medicine subspecialties were lower, and they happened to be interventional cardiology (20.1%) and clinical cardiac electrophysiology (14.5%).

When men are added to the mix, cardiovascular disease had a total of 3,320 active residents training in 268 programs in 2021-2022, making it the largest of the IM subspecialties in both respects. The resident total is up 57% since 2003, when it came in at 2,117, while programs have increased 55% from the 173 that were operating 2 decades ago. During the year in the middle (2011-2012), there were 2,521 residents in 187 programs, so a larger share of the growth has occurred in the last 10 years, the ACGME data indicate.

The shortage of cardiologists that Dr. Fye and others wrote about 20 years ago has not gone away. A 2018 report from health consulting firm PYA noted the increase in obesity and the low number of medical school graduates choosing the specialty. “Older and fewer physicians specializing in cardiology, coupled with the aging of baby boomers and gravitation toward practice in urban areas, will continue to exacerbate shortages in physician services in the specialty of cardiology, especially in rural areas, over the next decade,” PYA principal Lyle Oelrich wrote.

A little math appears to back up the claims of a cardiologist shortage. Based on census figures for the U.S. population in 2003, there were 14,470 Americans for each of the cardiologists reported by the AMA. That figure dropped to 13,966 by 2022, which seems like an improvement, but it comes with a caveat. The number of Americans aged 65 years and older increased from 1,798 to 2,377 per cardiologist as of 2020, the latest year for which population data were available by age.

One source of growth in the cardiology workforce has been perhaps its most significant minority: international medical graduates. Even by 2004, IMGs represented a much larger segment of all cardiologists (30.0%) than did women (9.3%), based on AMA data. To put it another way, there were more IMGs specializing in cardiovascular disease (6,615) in 2004 than there were women (3,963) in 2022.

The latest data on cardiology training programs – overall numbers were not available – put IMGs at 39.2% for the 2019-2020 academic year. The 2022 fellowship match provides a slightly smaller proportion of IMGs (37.4%) filling cardiovascular disease positions, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

Despite Mark Twain’s assertion that “there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics,” we’re going to dive into 20 years’ worth of data and, hopefully, come up with a few statistics that shed some light on the specialty’s workforce since Cardiology News published its first issue in February 2003.

We start with a major issue over these last 20 years: The participation of women in the specialty.

Back in July of 2002, just a few months before the first issue of Cardiology News was published, W. Bruce Fye, MD, then-president of the American College of Cardiology, wrote, “We need to do more to attract female medical graduates to our specialty because they represent almost one-half of the new doctors trained in this country. Cardiology needs to take full advantage of this large talent pool”

Data from the American Medical Association confirm that assertion: Of the nearly 20,000 postgraduate cardiologists in practice that year, only 7.8% were women. And that was at a time when more than 42% of medical school graduates were women, Dr. Fye noted, while also pointing out that “only 10% of cardiology trainees are female, and just 6% of ACC fellows are women.”

The gap between men and women has closed somewhat in the last 20 years, but the specialty continues to lag behind the profession as a whole. Women represented 16.7% of cardiologists in 2022, versus 37% of physicians overall, AMA data show. In 2019, for the first time, the majority of U.S. medical school students (50.5%) were women, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

A look at residency numbers from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education shows that continued slow improvement in the number of women can be expected, as 25.5% of cardiovascular disease residents were women during the 2021-2022 academic year. Only 2 of the 19 other internal medicine subspecialties were lower, and they happened to be interventional cardiology (20.1%) and clinical cardiac electrophysiology (14.5%).

When men are added to the mix, cardiovascular disease had a total of 3,320 active residents training in 268 programs in 2021-2022, making it the largest of the IM subspecialties in both respects. The resident total is up 57% since 2003, when it came in at 2,117, while programs have increased 55% from the 173 that were operating 2 decades ago. During the year in the middle (2011-2012), there were 2,521 residents in 187 programs, so a larger share of the growth has occurred in the last 10 years, the ACGME data indicate.

The shortage of cardiologists that Dr. Fye and others wrote about 20 years ago has not gone away. A 2018 report from health consulting firm PYA noted the increase in obesity and the low number of medical school graduates choosing the specialty. “Older and fewer physicians specializing in cardiology, coupled with the aging of baby boomers and gravitation toward practice in urban areas, will continue to exacerbate shortages in physician services in the specialty of cardiology, especially in rural areas, over the next decade,” PYA principal Lyle Oelrich wrote.

A little math appears to back up the claims of a cardiologist shortage. Based on census figures for the U.S. population in 2003, there were 14,470 Americans for each of the cardiologists reported by the AMA. That figure dropped to 13,966 by 2022, which seems like an improvement, but it comes with a caveat. The number of Americans aged 65 years and older increased from 1,798 to 2,377 per cardiologist as of 2020, the latest year for which population data were available by age.

One source of growth in the cardiology workforce has been perhaps its most significant minority: international medical graduates. Even by 2004, IMGs represented a much larger segment of all cardiologists (30.0%) than did women (9.3%), based on AMA data. To put it another way, there were more IMGs specializing in cardiovascular disease (6,615) in 2004 than there were women (3,963) in 2022.

The latest data on cardiology training programs – overall numbers were not available – put IMGs at 39.2% for the 2019-2020 academic year. The 2022 fellowship match provides a slightly smaller proportion of IMGs (37.4%) filling cardiovascular disease positions, according to the National Resident Matching Program.

Hyperpigmented Papules on the Tongue of a Child

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

- Romiti R, Molina De Medeiros L. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:398-399. doi:10.1111/j .1525-1470.2010.01183.x

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Sechi A, et al. Pigmented fungiform lingual papillae: dermoscopic and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:935-939. doi:10.1111/jdv.14809

- Rice SM, Lal K. Successful treatment of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue with Q-switched ruby laser. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:368-369. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003371

- Mizawa M, Makino T, Furukawa F, et al. Efficacy of Q-switched ruby laser treatment for pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E133-E134. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16270

- Holzwanger JM, Rudolph RI, Heaton CL. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a common variant of oral pigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974. tb05073.x

- Mukamal LV, Ormiga P, Ramos-E-Silva M. Dermoscopy of the pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2012;39:397-399. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01328.x

- Surboyo MDC, Santosh ABR, Hariyani N, et al. Clinical utility of dermoscopy on diagnosing pigmented papillary fungiform papillae of the tongue: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2021;11:618-623. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.09.008

- Chamseddin B, Vandergriff T. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a clinical and histologic description [published online September 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8674c519.

- Jayasree P, Kaliyadan F, Ashique KT. Black hairy tongue. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5314

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0268-y

- Sandru F, Petca A, Dumitrascu MC, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: skin manifestations and endocrine anomalies (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1387. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10823

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189.e1-210. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.037

- Lee K, Lian C, Vaidya A, et al. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:993-995. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.013

- Haitjema T, Westermann CJ, Overtoom TT, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease): new insights in pathogenesis, complications, and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:714-719.

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Ugajin T, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber’s disease): detailed assessment of skin lesions by dermoscopy and ultrasound. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E224-E226. doi:10.1111/ijd.14578

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

- Romiti R, Molina De Medeiros L. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:398-399. doi:10.1111/j .1525-1470.2010.01183.x

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Sechi A, et al. Pigmented fungiform lingual papillae: dermoscopic and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:935-939. doi:10.1111/jdv.14809

- Rice SM, Lal K. Successful treatment of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue with Q-switched ruby laser. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:368-369. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003371

- Mizawa M, Makino T, Furukawa F, et al. Efficacy of Q-switched ruby laser treatment for pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E133-E134. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16270

- Holzwanger JM, Rudolph RI, Heaton CL. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a common variant of oral pigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974. tb05073.x

- Mukamal LV, Ormiga P, Ramos-E-Silva M. Dermoscopy of the pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2012;39:397-399. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01328.x

- Surboyo MDC, Santosh ABR, Hariyani N, et al. Clinical utility of dermoscopy on diagnosing pigmented papillary fungiform papillae of the tongue: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2021;11:618-623. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.09.008

- Chamseddin B, Vandergriff T. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a clinical and histologic description [published online September 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8674c519.