User login

Screening for diabetes at normal BMIs could cut racial disparities

Use of race-based diabetes screening thresholds could reduce the disparity that arises from current screening guidelines in the United States, new research suggests.

In August 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended age for type 2 diabetes screening from 40 to 35 years among people with a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or greater.

However, the diabetes rate among ethnic minorities aged 35-70 years in the United States is not just higher overall but, in certain populations, also occurs more frequently at a younger age and at lower BMIs, the new study indicates.

Among people with a BMI below 25 kg/m2, the diabetes prevalence is two to four times higher among Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans than among the U.S. White population.

And the authors of the new study, led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, predict that if screening begins at age 35 years, the BMI cut-off equivalent to 25 kg/m2 for White Americans would be 18.5 kg/m2 for Hispanic and Black Americans and 20 kg/m2 for Asian Americans.

“While diabetes has often been thought of as a disease that primarily affects adults with overweight or [obesity], our findings suggest that normal-weight adults in minority groups have surprisingly high rates of diabetes,” Dr. Aggarwal, senior resident physician in internal medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“Assessing diabetes risks in certain racial/ethnic groups will be necessary, even if these adults do not have overweight or [obesity],” he added.

Not screening in this way “is a missed opportunity for early intervention,” he noted.

And both the authors and an editorialist stress that the issue isn’t just theoretical.

“USPSTF recommendations influence what payers choose to cover, which in turn determines access to preventative services ... Addressing the staggering inequities in diabetes outcomes will require substantial investments in diabetes prevention and treatment, but making screening more equitable is a good place to start,” said senior author Dhruv S. Kazi, MD, of the Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology and director of the Cardiac Critical Care Unit at Beth Israel, Boston.

Screen minorities at a younger age if current BMI threshold kept

In their study, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 2011-2018, Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues also calculated that, if the BMI threshold is kept at 25 kg/m2, then the equivalent age cut-offs for Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans would be 23, 21, and 25 years, respectively, compared with 35 years for White Americans.

The findings were published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The prevalence of diabetes in those aged 35-70 years in the NHANES population was 17.3% for Asian Americans and 12.5% for those who were White (odds ratio, 1.51 vs. Whites). Among Black Americans and Mexican Americans, the prevalence was 20.7% and 20.6%, respectively, almost twice the prevalence in Whites (OR, 1.85 and 1.80). For other Hispanic Americans, the prevalence was 16.4% (OR, 1.37 vs. Whites). All of those differences were significant, compared with White Americans.

Undiagnosed diabetes was also significantly more common among minority populations, at 27.6%, 22.8%, 21.2%, and 23.5% for Asian, Black, Mexican, and other Hispanic Americans, respectively, versus 12.5% for White Americans.

‘The time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance’

“While there is more work to be done on carefully examining the long-term risk–benefit trade-off of various diabetes screening, I believe the time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance on the use of lower thresholds for screening higher-risk individuals,” Dr. Kazi told this news organization.

The author of an accompanying editorial agrees, noting that in a recent commentary the USPSTF, itself, “acknowledged the persistent inequalities across the screening-to-treatment continuum that result in racial/ethnic health disparities in the United States.”

And the USPSTF “emphasized the need to improve systems of care to ensure equitable and consistent delivery of high-quality preventive and treatment services, with special attention to racial/ethnic groups who may experience worse health outcomes,” continues Quyen Ngo-Metzger, MD, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, California.

For other conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and infectious disease, the USPSTF already recommends risk-based preventive services.

“To address the current inequity in diabetes screening, the USPSTF should apply the same consideration to its diabetes screening recommendation,” she notes.

‘Implementation will require an eye for pragmatism’

Asked about how this recommendation might be carried out in the real world, Dr. Aggarwal said in an interview that, because all three minority groups with normal weight had similar diabetes risk profiles to White adults with overweight, “one way for clinicians to easily implement these findings is by screening all Asian, Black, and Hispanic adults ages 35-70 years with normal weight for diabetes, similarly to how all White adults ages 35-70 years with overweight are currently recommended for screening.”

Dr. Kazi said: “I believe that implementation will require an eye for pragmatism,” noting that another option would be to have screening algorithms embedded in the electronic health record to flag individuals who qualify.

In any case, “the simplicity of the current one-size-fits-all approach is alluring, but it is profoundly inequitable. The more I look at the empiric evidence on diabetes burden in our communities, the more the status quo becomes untenable.”

However, Dr. Kazi also noted, “the benefit of any screening program relates to what we do with the information. The key is to ensure that folks identified as having diabetes – or better still prediabetes – receive timely lifestyle and pharmacological interventions to avert its long-term complications.”

This study was supported by institutional funds from the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology. Dr. Aggarwal, Dr. Kazi, and Dr. Ngo-Metzger have reported no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of race-based diabetes screening thresholds could reduce the disparity that arises from current screening guidelines in the United States, new research suggests.

In August 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended age for type 2 diabetes screening from 40 to 35 years among people with a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or greater.

However, the diabetes rate among ethnic minorities aged 35-70 years in the United States is not just higher overall but, in certain populations, also occurs more frequently at a younger age and at lower BMIs, the new study indicates.

Among people with a BMI below 25 kg/m2, the diabetes prevalence is two to four times higher among Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans than among the U.S. White population.

And the authors of the new study, led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, predict that if screening begins at age 35 years, the BMI cut-off equivalent to 25 kg/m2 for White Americans would be 18.5 kg/m2 for Hispanic and Black Americans and 20 kg/m2 for Asian Americans.

“While diabetes has often been thought of as a disease that primarily affects adults with overweight or [obesity], our findings suggest that normal-weight adults in minority groups have surprisingly high rates of diabetes,” Dr. Aggarwal, senior resident physician in internal medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“Assessing diabetes risks in certain racial/ethnic groups will be necessary, even if these adults do not have overweight or [obesity],” he added.

Not screening in this way “is a missed opportunity for early intervention,” he noted.

And both the authors and an editorialist stress that the issue isn’t just theoretical.

“USPSTF recommendations influence what payers choose to cover, which in turn determines access to preventative services ... Addressing the staggering inequities in diabetes outcomes will require substantial investments in diabetes prevention and treatment, but making screening more equitable is a good place to start,” said senior author Dhruv S. Kazi, MD, of the Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology and director of the Cardiac Critical Care Unit at Beth Israel, Boston.

Screen minorities at a younger age if current BMI threshold kept

In their study, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 2011-2018, Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues also calculated that, if the BMI threshold is kept at 25 kg/m2, then the equivalent age cut-offs for Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans would be 23, 21, and 25 years, respectively, compared with 35 years for White Americans.

The findings were published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The prevalence of diabetes in those aged 35-70 years in the NHANES population was 17.3% for Asian Americans and 12.5% for those who were White (odds ratio, 1.51 vs. Whites). Among Black Americans and Mexican Americans, the prevalence was 20.7% and 20.6%, respectively, almost twice the prevalence in Whites (OR, 1.85 and 1.80). For other Hispanic Americans, the prevalence was 16.4% (OR, 1.37 vs. Whites). All of those differences were significant, compared with White Americans.

Undiagnosed diabetes was also significantly more common among minority populations, at 27.6%, 22.8%, 21.2%, and 23.5% for Asian, Black, Mexican, and other Hispanic Americans, respectively, versus 12.5% for White Americans.

‘The time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance’

“While there is more work to be done on carefully examining the long-term risk–benefit trade-off of various diabetes screening, I believe the time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance on the use of lower thresholds for screening higher-risk individuals,” Dr. Kazi told this news organization.

The author of an accompanying editorial agrees, noting that in a recent commentary the USPSTF, itself, “acknowledged the persistent inequalities across the screening-to-treatment continuum that result in racial/ethnic health disparities in the United States.”

And the USPSTF “emphasized the need to improve systems of care to ensure equitable and consistent delivery of high-quality preventive and treatment services, with special attention to racial/ethnic groups who may experience worse health outcomes,” continues Quyen Ngo-Metzger, MD, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, California.

For other conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and infectious disease, the USPSTF already recommends risk-based preventive services.

“To address the current inequity in diabetes screening, the USPSTF should apply the same consideration to its diabetes screening recommendation,” she notes.

‘Implementation will require an eye for pragmatism’

Asked about how this recommendation might be carried out in the real world, Dr. Aggarwal said in an interview that, because all three minority groups with normal weight had similar diabetes risk profiles to White adults with overweight, “one way for clinicians to easily implement these findings is by screening all Asian, Black, and Hispanic adults ages 35-70 years with normal weight for diabetes, similarly to how all White adults ages 35-70 years with overweight are currently recommended for screening.”

Dr. Kazi said: “I believe that implementation will require an eye for pragmatism,” noting that another option would be to have screening algorithms embedded in the electronic health record to flag individuals who qualify.

In any case, “the simplicity of the current one-size-fits-all approach is alluring, but it is profoundly inequitable. The more I look at the empiric evidence on diabetes burden in our communities, the more the status quo becomes untenable.”

However, Dr. Kazi also noted, “the benefit of any screening program relates to what we do with the information. The key is to ensure that folks identified as having diabetes – or better still prediabetes – receive timely lifestyle and pharmacological interventions to avert its long-term complications.”

This study was supported by institutional funds from the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology. Dr. Aggarwal, Dr. Kazi, and Dr. Ngo-Metzger have reported no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of race-based diabetes screening thresholds could reduce the disparity that arises from current screening guidelines in the United States, new research suggests.

In August 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lowered the recommended age for type 2 diabetes screening from 40 to 35 years among people with a body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or greater.

However, the diabetes rate among ethnic minorities aged 35-70 years in the United States is not just higher overall but, in certain populations, also occurs more frequently at a younger age and at lower BMIs, the new study indicates.

Among people with a BMI below 25 kg/m2, the diabetes prevalence is two to four times higher among Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans than among the U.S. White population.

And the authors of the new study, led by Rahul Aggarwal, MD, predict that if screening begins at age 35 years, the BMI cut-off equivalent to 25 kg/m2 for White Americans would be 18.5 kg/m2 for Hispanic and Black Americans and 20 kg/m2 for Asian Americans.

“While diabetes has often been thought of as a disease that primarily affects adults with overweight or [obesity], our findings suggest that normal-weight adults in minority groups have surprisingly high rates of diabetes,” Dr. Aggarwal, senior resident physician in internal medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“Assessing diabetes risks in certain racial/ethnic groups will be necessary, even if these adults do not have overweight or [obesity],” he added.

Not screening in this way “is a missed opportunity for early intervention,” he noted.

And both the authors and an editorialist stress that the issue isn’t just theoretical.

“USPSTF recommendations influence what payers choose to cover, which in turn determines access to preventative services ... Addressing the staggering inequities in diabetes outcomes will require substantial investments in diabetes prevention and treatment, but making screening more equitable is a good place to start,” said senior author Dhruv S. Kazi, MD, of the Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology and director of the Cardiac Critical Care Unit at Beth Israel, Boston.

Screen minorities at a younger age if current BMI threshold kept

In their study, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 2011-2018, Dr. Aggarwal and colleagues also calculated that, if the BMI threshold is kept at 25 kg/m2, then the equivalent age cut-offs for Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans would be 23, 21, and 25 years, respectively, compared with 35 years for White Americans.

The findings were published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The prevalence of diabetes in those aged 35-70 years in the NHANES population was 17.3% for Asian Americans and 12.5% for those who were White (odds ratio, 1.51 vs. Whites). Among Black Americans and Mexican Americans, the prevalence was 20.7% and 20.6%, respectively, almost twice the prevalence in Whites (OR, 1.85 and 1.80). For other Hispanic Americans, the prevalence was 16.4% (OR, 1.37 vs. Whites). All of those differences were significant, compared with White Americans.

Undiagnosed diabetes was also significantly more common among minority populations, at 27.6%, 22.8%, 21.2%, and 23.5% for Asian, Black, Mexican, and other Hispanic Americans, respectively, versus 12.5% for White Americans.

‘The time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance’

“While there is more work to be done on carefully examining the long-term risk–benefit trade-off of various diabetes screening, I believe the time has come for USPSTF to offer more concrete guidance on the use of lower thresholds for screening higher-risk individuals,” Dr. Kazi told this news organization.

The author of an accompanying editorial agrees, noting that in a recent commentary the USPSTF, itself, “acknowledged the persistent inequalities across the screening-to-treatment continuum that result in racial/ethnic health disparities in the United States.”

And the USPSTF “emphasized the need to improve systems of care to ensure equitable and consistent delivery of high-quality preventive and treatment services, with special attention to racial/ethnic groups who may experience worse health outcomes,” continues Quyen Ngo-Metzger, MD, Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Pasadena, California.

For other conditions, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and infectious disease, the USPSTF already recommends risk-based preventive services.

“To address the current inequity in diabetes screening, the USPSTF should apply the same consideration to its diabetes screening recommendation,” she notes.

‘Implementation will require an eye for pragmatism’

Asked about how this recommendation might be carried out in the real world, Dr. Aggarwal said in an interview that, because all three minority groups with normal weight had similar diabetes risk profiles to White adults with overweight, “one way for clinicians to easily implement these findings is by screening all Asian, Black, and Hispanic adults ages 35-70 years with normal weight for diabetes, similarly to how all White adults ages 35-70 years with overweight are currently recommended for screening.”

Dr. Kazi said: “I believe that implementation will require an eye for pragmatism,” noting that another option would be to have screening algorithms embedded in the electronic health record to flag individuals who qualify.

In any case, “the simplicity of the current one-size-fits-all approach is alluring, but it is profoundly inequitable. The more I look at the empiric evidence on diabetes burden in our communities, the more the status quo becomes untenable.”

However, Dr. Kazi also noted, “the benefit of any screening program relates to what we do with the information. The key is to ensure that folks identified as having diabetes – or better still prediabetes – receive timely lifestyle and pharmacological interventions to avert its long-term complications.”

This study was supported by institutional funds from the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology. Dr. Aggarwal, Dr. Kazi, and Dr. Ngo-Metzger have reported no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Melanoma

THE COMPARISON

A Acral lentiginous melanoma on the sole of the foot of a 30-year-old Black woman. The depth of the lesion was 2 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

B Nodular melanoma on the shoulder of a 63-year-old Hispanic woman. The depth of the lesion was 5.5 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Melanoma occurs less frequently in individuals with darker skin types than in those with lighter skin types but is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality in this patient population.1-7 In the cases shown here (A and B), both patients had advanced melanomas with large primary lesions and lymph node metastases.

Epidemiology

A systematic review by Higgins et al6 reported the following on the epidemiology of melanomas in patients with skin of color:

- African Americans have deeper tumors at the time of diagnosis, in addition to increased rates of regionally advanced and distant disease. Lesions generally are located on the lower extremities and have an increased propensity for ulceration. Acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype found in African American patients.6

- In Hispanic individuals, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype. Lower extremity lesions are more common relative to White individuals. Hispanic individuals have the highest rate of oral cavity melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

- In Asian individuals, acral and subungual sites are most common. Specifically, Pacific Islanders have the highest proportion of mucosal melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melanomas are found more often on the palms, soles, nail units, oral cavity, and mucosae.6 The melanomas have the same clinical and dermoscopic features found in individuals with lighter skin tones.

Worth noting

Factors that may contribute to the diagnosis of more advanced melanomas in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States include:

- decreased access to health care based on lack of health insurance and low socioeconomic status,

- less awareness of the risk of melanoma among patients and health care providers because melanoma is less common in persons of color, and

- lesions found in areas less likely to be seen in screening examinations, such as the soles of the feet and the oral and genital mucosae.

Health disparity highlight

- In a large US study of 96,953 patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma from 1992 to 2009, the proportion of later-stage melanoma—stages II to IV—was greater in Black patients compared to White patients.7

- Based on this same data set, White patients had the longest survival time (P <. 05), followed by Hispanic (P < .05), Asian American/Native American/Pacific Islander (P < .05), and Black (P < .05) patients, respectively.7

- In Miami-Dade County, one study of 1690 melanoma cases found that 48% of Black patients had regional or distant disease at presentation compared to 22% of White patients (P = .015).5 Analysis of multiple factors found that only race was a significant predictor for late-stage melanoma (P < .001). Black patients in this study were 3 times more likely than others to be diagnosed with melanoma at a late stage (P = .07).5

- Black patients in the United States are more likely to have a delayed time from diagnosis to definitive surgery even when researchers controlled for type of health insurance and stage of diagnosis.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to overcome these disparities by:

- educating patients with skin of color and their health care providers about the risks of advanced melanoma with the goal of prevention and earlier diagnosis;

- breaking down barriers to care caused by poverty, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism; and

- eliminating factors that lead to delays from diagnosis to definitive surgery.

1. Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2001.05.034

2. Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

3. Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California cancer registry data, 1988-93. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252. doi: 10.1023/a:1018432632528

4. Hu S, Parker DF, Thomas AG, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans: the Miami-Dade County experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1031-1032. doi: 10.1016/ j.jaad.2004.05.005

5. Hu S, Soza-Vento RM, Parker DF, et al. Comparison of stage at diagnosis of melanoma among Hispanic, black, and white patients in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142: 704-708. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.704

6. Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:791-801. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001759

7. Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival [published online July 28, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.006

8. Qian Y, Johannet P, Sawyers A, et al. The ongoing racial disparities in melanoma: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1975-2016) [published online August 27, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1585-1593. doi: 10.1016/ j.jaad.2020.08.097

THE COMPARISON

A Acral lentiginous melanoma on the sole of the foot of a 30-year-old Black woman. The depth of the lesion was 2 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

B Nodular melanoma on the shoulder of a 63-year-old Hispanic woman. The depth of the lesion was 5.5 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Melanoma occurs less frequently in individuals with darker skin types than in those with lighter skin types but is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality in this patient population.1-7 In the cases shown here (A and B), both patients had advanced melanomas with large primary lesions and lymph node metastases.

Epidemiology

A systematic review by Higgins et al6 reported the following on the epidemiology of melanomas in patients with skin of color:

- African Americans have deeper tumors at the time of diagnosis, in addition to increased rates of regionally advanced and distant disease. Lesions generally are located on the lower extremities and have an increased propensity for ulceration. Acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype found in African American patients.6

- In Hispanic individuals, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype. Lower extremity lesions are more common relative to White individuals. Hispanic individuals have the highest rate of oral cavity melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

- In Asian individuals, acral and subungual sites are most common. Specifically, Pacific Islanders have the highest proportion of mucosal melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melanomas are found more often on the palms, soles, nail units, oral cavity, and mucosae.6 The melanomas have the same clinical and dermoscopic features found in individuals with lighter skin tones.

Worth noting

Factors that may contribute to the diagnosis of more advanced melanomas in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States include:

- decreased access to health care based on lack of health insurance and low socioeconomic status,

- less awareness of the risk of melanoma among patients and health care providers because melanoma is less common in persons of color, and

- lesions found in areas less likely to be seen in screening examinations, such as the soles of the feet and the oral and genital mucosae.

Health disparity highlight

- In a large US study of 96,953 patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma from 1992 to 2009, the proportion of later-stage melanoma—stages II to IV—was greater in Black patients compared to White patients.7

- Based on this same data set, White patients had the longest survival time (P <. 05), followed by Hispanic (P < .05), Asian American/Native American/Pacific Islander (P < .05), and Black (P < .05) patients, respectively.7

- In Miami-Dade County, one study of 1690 melanoma cases found that 48% of Black patients had regional or distant disease at presentation compared to 22% of White patients (P = .015).5 Analysis of multiple factors found that only race was a significant predictor for late-stage melanoma (P < .001). Black patients in this study were 3 times more likely than others to be diagnosed with melanoma at a late stage (P = .07).5

- Black patients in the United States are more likely to have a delayed time from diagnosis to definitive surgery even when researchers controlled for type of health insurance and stage of diagnosis.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to overcome these disparities by:

- educating patients with skin of color and their health care providers about the risks of advanced melanoma with the goal of prevention and earlier diagnosis;

- breaking down barriers to care caused by poverty, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism; and

- eliminating factors that lead to delays from diagnosis to definitive surgery.

THE COMPARISON

A Acral lentiginous melanoma on the sole of the foot of a 30-year-old Black woman. The depth of the lesion was 2 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

B Nodular melanoma on the shoulder of a 63-year-old Hispanic woman. The depth of the lesion was 5.5 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Melanoma occurs less frequently in individuals with darker skin types than in those with lighter skin types but is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality in this patient population.1-7 In the cases shown here (A and B), both patients had advanced melanomas with large primary lesions and lymph node metastases.

Epidemiology

A systematic review by Higgins et al6 reported the following on the epidemiology of melanomas in patients with skin of color:

- African Americans have deeper tumors at the time of diagnosis, in addition to increased rates of regionally advanced and distant disease. Lesions generally are located on the lower extremities and have an increased propensity for ulceration. Acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype found in African American patients.6

- In Hispanic individuals, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype. Lower extremity lesions are more common relative to White individuals. Hispanic individuals have the highest rate of oral cavity melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

- In Asian individuals, acral and subungual sites are most common. Specifically, Pacific Islanders have the highest proportion of mucosal melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melanomas are found more often on the palms, soles, nail units, oral cavity, and mucosae.6 The melanomas have the same clinical and dermoscopic features found in individuals with lighter skin tones.

Worth noting

Factors that may contribute to the diagnosis of more advanced melanomas in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States include:

- decreased access to health care based on lack of health insurance and low socioeconomic status,

- less awareness of the risk of melanoma among patients and health care providers because melanoma is less common in persons of color, and

- lesions found in areas less likely to be seen in screening examinations, such as the soles of the feet and the oral and genital mucosae.

Health disparity highlight

- In a large US study of 96,953 patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma from 1992 to 2009, the proportion of later-stage melanoma—stages II to IV—was greater in Black patients compared to White patients.7

- Based on this same data set, White patients had the longest survival time (P <. 05), followed by Hispanic (P < .05), Asian American/Native American/Pacific Islander (P < .05), and Black (P < .05) patients, respectively.7

- In Miami-Dade County, one study of 1690 melanoma cases found that 48% of Black patients had regional or distant disease at presentation compared to 22% of White patients (P = .015).5 Analysis of multiple factors found that only race was a significant predictor for late-stage melanoma (P < .001). Black patients in this study were 3 times more likely than others to be diagnosed with melanoma at a late stage (P = .07).5

- Black patients in the United States are more likely to have a delayed time from diagnosis to definitive surgery even when researchers controlled for type of health insurance and stage of diagnosis.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to overcome these disparities by:

- educating patients with skin of color and their health care providers about the risks of advanced melanoma with the goal of prevention and earlier diagnosis;

- breaking down barriers to care caused by poverty, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism; and

- eliminating factors that lead to delays from diagnosis to definitive surgery.

1. Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2001.05.034

2. Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

3. Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California cancer registry data, 1988-93. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252. doi: 10.1023/a:1018432632528

4. Hu S, Parker DF, Thomas AG, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans: the Miami-Dade County experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1031-1032. doi: 10.1016/ j.jaad.2004.05.005

5. Hu S, Soza-Vento RM, Parker DF, et al. Comparison of stage at diagnosis of melanoma among Hispanic, black, and white patients in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142: 704-708. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.704

6. Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:791-801. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001759

7. Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival [published online July 28, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.006

8. Qian Y, Johannet P, Sawyers A, et al. The ongoing racial disparities in melanoma: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1975-2016) [published online August 27, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1585-1593. doi: 10.1016/ j.jaad.2020.08.097

1. Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2001.05.034

2. Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

3. Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California cancer registry data, 1988-93. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252. doi: 10.1023/a:1018432632528

4. Hu S, Parker DF, Thomas AG, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans: the Miami-Dade County experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1031-1032. doi: 10.1016/ j.jaad.2004.05.005

5. Hu S, Soza-Vento RM, Parker DF, et al. Comparison of stage at diagnosis of melanoma among Hispanic, black, and white patients in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142: 704-708. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.704

6. Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:791-801. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001759

7. Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival [published online July 28, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.006

8. Qian Y, Johannet P, Sawyers A, et al. The ongoing racial disparities in melanoma: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1975-2016) [published online August 27, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1585-1593. doi: 10.1016/ j.jaad.2020.08.097

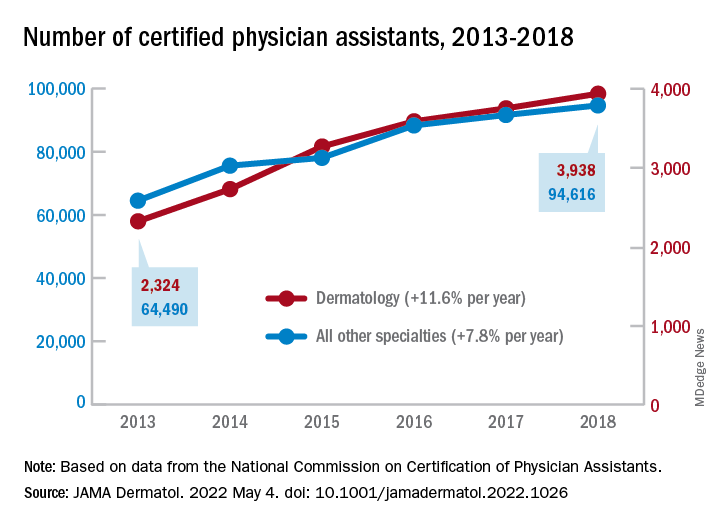

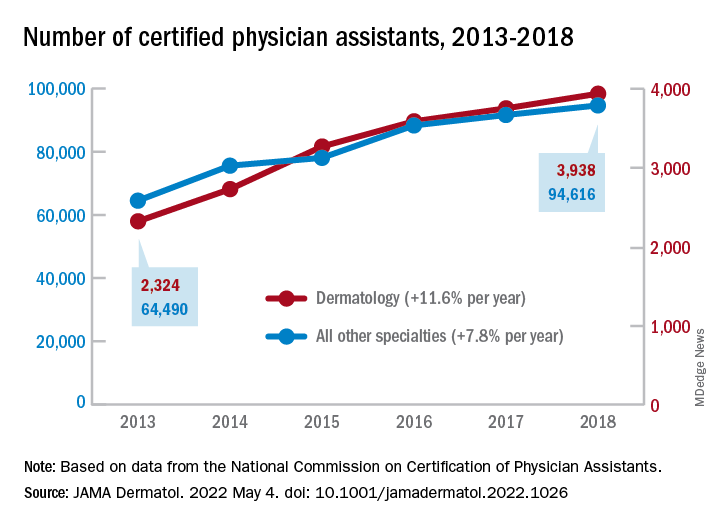

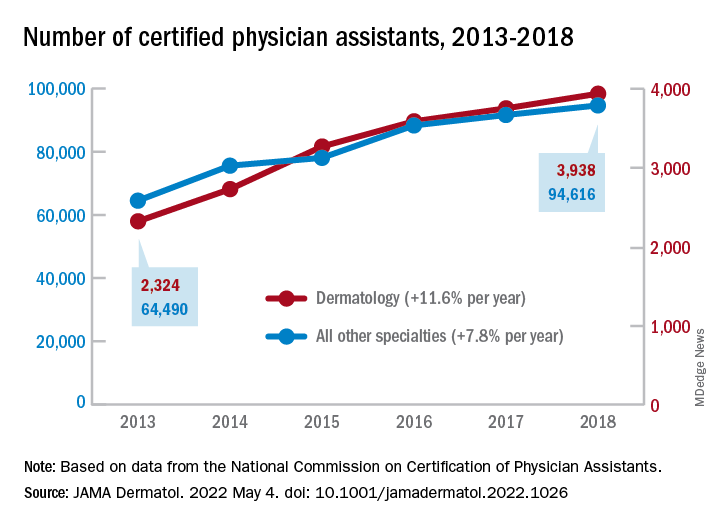

Dermatology attracts more than its share of physician assistants

Dermatology added PAs at a mean rate of 11.6% annually over that 6-year period, compared with a mean of 7.8% for all other specialties (P <.001), as the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) tallied 2,324 working in dermatology and 64,490 in all other specialties in 2013 and 3,938/94,616, respectively, in 2018, Justin D. Arnold, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

“There is, however, a lack of racial and ethnic diversity within the dermatology PA workforce,” they noted. A detailed comparison using the 2018 data showed that only 1.6% of dermatology PAs identified as Black, compared with 3.7% of those in all other specialties (P <.001), although “similar rates of Hispanic ethnicity were observed” in dermatology PAs (6.0%) and PAs in other fields (6.5%), the investigators added.

That was not the case for women in the profession, as 82% of PAs in dermatology were female in 2018, compared with 67% in the other specialties. Dermatology PAs also were significantly more likely to work in office-based practices than their nondermatology peers (93% vs. 37%, P < .001) and to reside in metropolitan areas (95% vs. 92%, P < .001), Dr. Arnold and associates said in the research letter.

The dermatology PAs also were more likely to work part time (30 or fewer hours per week) than those outside dermatology, 19.1% vs. 12.9% (P < .001). Despite that, the dermatology PAs reported seeing more patients per week (a mean of 119) than those in all of the other specialties (a mean of 71), the investigators said.

The total number of certified PAs was over 131,000 in 2018, but about 25% had not selected a principal specialty in their PA Professional Profiles and were not included in the study, they explained.

“Although this study did not assess the reasons for the substantial increase of dermatology PAs, numerous factors, such as a potential physician shortage or the expansion of private equity–owned practices, may contribute to the accelerating use of PAs within the field,” they wrote.

Dermatology added PAs at a mean rate of 11.6% annually over that 6-year period, compared with a mean of 7.8% for all other specialties (P <.001), as the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) tallied 2,324 working in dermatology and 64,490 in all other specialties in 2013 and 3,938/94,616, respectively, in 2018, Justin D. Arnold, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

“There is, however, a lack of racial and ethnic diversity within the dermatology PA workforce,” they noted. A detailed comparison using the 2018 data showed that only 1.6% of dermatology PAs identified as Black, compared with 3.7% of those in all other specialties (P <.001), although “similar rates of Hispanic ethnicity were observed” in dermatology PAs (6.0%) and PAs in other fields (6.5%), the investigators added.

That was not the case for women in the profession, as 82% of PAs in dermatology were female in 2018, compared with 67% in the other specialties. Dermatology PAs also were significantly more likely to work in office-based practices than their nondermatology peers (93% vs. 37%, P < .001) and to reside in metropolitan areas (95% vs. 92%, P < .001), Dr. Arnold and associates said in the research letter.

The dermatology PAs also were more likely to work part time (30 or fewer hours per week) than those outside dermatology, 19.1% vs. 12.9% (P < .001). Despite that, the dermatology PAs reported seeing more patients per week (a mean of 119) than those in all of the other specialties (a mean of 71), the investigators said.

The total number of certified PAs was over 131,000 in 2018, but about 25% had not selected a principal specialty in their PA Professional Profiles and were not included in the study, they explained.

“Although this study did not assess the reasons for the substantial increase of dermatology PAs, numerous factors, such as a potential physician shortage or the expansion of private equity–owned practices, may contribute to the accelerating use of PAs within the field,” they wrote.

Dermatology added PAs at a mean rate of 11.6% annually over that 6-year period, compared with a mean of 7.8% for all other specialties (P <.001), as the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) tallied 2,324 working in dermatology and 64,490 in all other specialties in 2013 and 3,938/94,616, respectively, in 2018, Justin D. Arnold, MD, of the University of California, Irvine, and associates reported in JAMA Dermatology.

“There is, however, a lack of racial and ethnic diversity within the dermatology PA workforce,” they noted. A detailed comparison using the 2018 data showed that only 1.6% of dermatology PAs identified as Black, compared with 3.7% of those in all other specialties (P <.001), although “similar rates of Hispanic ethnicity were observed” in dermatology PAs (6.0%) and PAs in other fields (6.5%), the investigators added.

That was not the case for women in the profession, as 82% of PAs in dermatology were female in 2018, compared with 67% in the other specialties. Dermatology PAs also were significantly more likely to work in office-based practices than their nondermatology peers (93% vs. 37%, P < .001) and to reside in metropolitan areas (95% vs. 92%, P < .001), Dr. Arnold and associates said in the research letter.

The dermatology PAs also were more likely to work part time (30 or fewer hours per week) than those outside dermatology, 19.1% vs. 12.9% (P < .001). Despite that, the dermatology PAs reported seeing more patients per week (a mean of 119) than those in all of the other specialties (a mean of 71), the investigators said.

The total number of certified PAs was over 131,000 in 2018, but about 25% had not selected a principal specialty in their PA Professional Profiles and were not included in the study, they explained.

“Although this study did not assess the reasons for the substantial increase of dermatology PAs, numerous factors, such as a potential physician shortage or the expansion of private equity–owned practices, may contribute to the accelerating use of PAs within the field,” they wrote.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Telehealth continues to loom large, say experts

This physician, Brian Hasselfeld, MD, said his university’s health system did 50-80 telemedicine visits a month before COVID, during a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. This soared to close to 100,000 a month in the pandemic, and now the health system does close to 40,000 a month, he continued.

“Life is definitely different in how we engage with our patients on a day-to-day basis,” said Dr. Hasselfeld, who oversees the telehealth for six hospitals and 50 ambulatory-care locations in Maryland and three other states.

Attitudes gauged in Johns Hopkins surveys suggest that a lot of medical care will continue to be provided by telemedicine. Nine out of 10 patients said they would likely recommend telemedicine to friends and family, and 88% said it would be either moderately, very, or extremely important to have video visit options in the future, he said.

A survey of the Hopkins system’s 3,600 physicians, which generated about 1,300 responses, found that physicians would like to have a considerable chunk of time set aside for telemedicine visits – the median response was 30%.

Virtual care is in ‘early-adopter phase’

But Dr. Hasselfeld said virtual care is still in the “early-adopter phase.” While many physicians said they would like more than half of their time devoted to telehealth, a larger proportion was more likely to say they wanted very little time devoted to it, Dr. Hasselfeld said. Among those wanting to do it are some who want to do all of their visits virtually, he said.

Those who are eager to do it will be those guiding the change, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

“As we move forward – and thinking about how to optimize virtual-care options for your patients – it’s not going to be a forced issue,” he said.

Providing better access to certain patient groups continues to be a challenge. A dashboard developed at Hopkins to identify groups who are at a technological disadvantage and don’t have ready access to telemedicine found that those living in low-income zip codes, African-Americans, and those on Medicaid and Medicare tend to have higher percentages of “audio-only” visits, mainly because of lack of connectivity allowing video visits, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

The lower share of video visits in the inner city suggests that access to telemedicine isn’t just a problem in remote rural areas, as the conventional wisdom has gone, he said.

“It doesn’t matter how many towers we have in downtown Baltimore, or how much fiber we have in the ground,” he said. “If you can’t have a data plan to access that high-speed Internet, or have a home with high-speed Internet, it doesn’t matter.”

Hopkins has developed a tool to assess how likely it is that someone will have trouble connecting for a telemedicine visit – if they’ve previously had an audio-only visit, for instance – and try to get in touch with those patients shortly before a visit so that it runs smoothly, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

The explosion of telemedicine has led to the rise of companies providing care through apps on phones and tablets, he said.

“This is real care being provided to our patients through nontraditional routes, and this is a new force, one our patients see out in the marketplace,” he said. “We have to acknowledge and wrestle with the fact that convenience is a new part of what it means to [provide] access [to] care for patients.”

Heather Hirsch, MD, an internist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview after the session that telemedicine is poised to improve care.

“I think the good is definitely going to outweigh the bad so long as the infrastructure and the legislation will allow it,” said Dr. Hirsch, who does about half of her visits in person and half through telemedicine, which she performs while at the office. “It does allow for a lot of flexibility for both patients and providers.”

But health care at academic medical centers, she said, needs to adjust to the times.

“We need [academic medicine] for so many reasons,” she said, “but the reality is that it moves very slowly, and the old infrastructure and the slowness to catch up with technology is the worry.”

Dr. Hasselfeld reported financial relationships with Humana and TRUE-See Systems.

This physician, Brian Hasselfeld, MD, said his university’s health system did 50-80 telemedicine visits a month before COVID, during a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. This soared to close to 100,000 a month in the pandemic, and now the health system does close to 40,000 a month, he continued.

“Life is definitely different in how we engage with our patients on a day-to-day basis,” said Dr. Hasselfeld, who oversees the telehealth for six hospitals and 50 ambulatory-care locations in Maryland and three other states.

Attitudes gauged in Johns Hopkins surveys suggest that a lot of medical care will continue to be provided by telemedicine. Nine out of 10 patients said they would likely recommend telemedicine to friends and family, and 88% said it would be either moderately, very, or extremely important to have video visit options in the future, he said.

A survey of the Hopkins system’s 3,600 physicians, which generated about 1,300 responses, found that physicians would like to have a considerable chunk of time set aside for telemedicine visits – the median response was 30%.

Virtual care is in ‘early-adopter phase’

But Dr. Hasselfeld said virtual care is still in the “early-adopter phase.” While many physicians said they would like more than half of their time devoted to telehealth, a larger proportion was more likely to say they wanted very little time devoted to it, Dr. Hasselfeld said. Among those wanting to do it are some who want to do all of their visits virtually, he said.

Those who are eager to do it will be those guiding the change, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

“As we move forward – and thinking about how to optimize virtual-care options for your patients – it’s not going to be a forced issue,” he said.

Providing better access to certain patient groups continues to be a challenge. A dashboard developed at Hopkins to identify groups who are at a technological disadvantage and don’t have ready access to telemedicine found that those living in low-income zip codes, African-Americans, and those on Medicaid and Medicare tend to have higher percentages of “audio-only” visits, mainly because of lack of connectivity allowing video visits, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

The lower share of video visits in the inner city suggests that access to telemedicine isn’t just a problem in remote rural areas, as the conventional wisdom has gone, he said.

“It doesn’t matter how many towers we have in downtown Baltimore, or how much fiber we have in the ground,” he said. “If you can’t have a data plan to access that high-speed Internet, or have a home with high-speed Internet, it doesn’t matter.”

Hopkins has developed a tool to assess how likely it is that someone will have trouble connecting for a telemedicine visit – if they’ve previously had an audio-only visit, for instance – and try to get in touch with those patients shortly before a visit so that it runs smoothly, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

The explosion of telemedicine has led to the rise of companies providing care through apps on phones and tablets, he said.

“This is real care being provided to our patients through nontraditional routes, and this is a new force, one our patients see out in the marketplace,” he said. “We have to acknowledge and wrestle with the fact that convenience is a new part of what it means to [provide] access [to] care for patients.”

Heather Hirsch, MD, an internist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview after the session that telemedicine is poised to improve care.

“I think the good is definitely going to outweigh the bad so long as the infrastructure and the legislation will allow it,” said Dr. Hirsch, who does about half of her visits in person and half through telemedicine, which she performs while at the office. “It does allow for a lot of flexibility for both patients and providers.”

But health care at academic medical centers, she said, needs to adjust to the times.

“We need [academic medicine] for so many reasons,” she said, “but the reality is that it moves very slowly, and the old infrastructure and the slowness to catch up with technology is the worry.”

Dr. Hasselfeld reported financial relationships with Humana and TRUE-See Systems.

This physician, Brian Hasselfeld, MD, said his university’s health system did 50-80 telemedicine visits a month before COVID, during a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. This soared to close to 100,000 a month in the pandemic, and now the health system does close to 40,000 a month, he continued.

“Life is definitely different in how we engage with our patients on a day-to-day basis,” said Dr. Hasselfeld, who oversees the telehealth for six hospitals and 50 ambulatory-care locations in Maryland and three other states.

Attitudes gauged in Johns Hopkins surveys suggest that a lot of medical care will continue to be provided by telemedicine. Nine out of 10 patients said they would likely recommend telemedicine to friends and family, and 88% said it would be either moderately, very, or extremely important to have video visit options in the future, he said.

A survey of the Hopkins system’s 3,600 physicians, which generated about 1,300 responses, found that physicians would like to have a considerable chunk of time set aside for telemedicine visits – the median response was 30%.

Virtual care is in ‘early-adopter phase’

But Dr. Hasselfeld said virtual care is still in the “early-adopter phase.” While many physicians said they would like more than half of their time devoted to telehealth, a larger proportion was more likely to say they wanted very little time devoted to it, Dr. Hasselfeld said. Among those wanting to do it are some who want to do all of their visits virtually, he said.

Those who are eager to do it will be those guiding the change, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

“As we move forward – and thinking about how to optimize virtual-care options for your patients – it’s not going to be a forced issue,” he said.

Providing better access to certain patient groups continues to be a challenge. A dashboard developed at Hopkins to identify groups who are at a technological disadvantage and don’t have ready access to telemedicine found that those living in low-income zip codes, African-Americans, and those on Medicaid and Medicare tend to have higher percentages of “audio-only” visits, mainly because of lack of connectivity allowing video visits, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

The lower share of video visits in the inner city suggests that access to telemedicine isn’t just a problem in remote rural areas, as the conventional wisdom has gone, he said.

“It doesn’t matter how many towers we have in downtown Baltimore, or how much fiber we have in the ground,” he said. “If you can’t have a data plan to access that high-speed Internet, or have a home with high-speed Internet, it doesn’t matter.”

Hopkins has developed a tool to assess how likely it is that someone will have trouble connecting for a telemedicine visit – if they’ve previously had an audio-only visit, for instance – and try to get in touch with those patients shortly before a visit so that it runs smoothly, Dr. Hasselfeld said.

The explosion of telemedicine has led to the rise of companies providing care through apps on phones and tablets, he said.

“This is real care being provided to our patients through nontraditional routes, and this is a new force, one our patients see out in the marketplace,” he said. “We have to acknowledge and wrestle with the fact that convenience is a new part of what it means to [provide] access [to] care for patients.”

Heather Hirsch, MD, an internist with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in an interview after the session that telemedicine is poised to improve care.

“I think the good is definitely going to outweigh the bad so long as the infrastructure and the legislation will allow it,” said Dr. Hirsch, who does about half of her visits in person and half through telemedicine, which she performs while at the office. “It does allow for a lot of flexibility for both patients and providers.”

But health care at academic medical centers, she said, needs to adjust to the times.

“We need [academic medicine] for so many reasons,” she said, “but the reality is that it moves very slowly, and the old infrastructure and the slowness to catch up with technology is the worry.”

Dr. Hasselfeld reported financial relationships with Humana and TRUE-See Systems.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2022

How Dermatology Residents Can Best Serve the Needs of the LGBT Community

The chances are good that at least one patient you saw today could have been provided a better environment to foster your patient-physician relationship. A 2020 Gallup poll revealed that an estimated 5.6% of US adults identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT).1 Based on the estimated US population of 331.7 million individuals on December 3, 2020, this means that approximately 18.6 million identified as LGBT and could potentially require health care services.2 These numbers highlight the increasing need within the medical community to provide quality and accessible care to the LGBT community, and dermatologists have a role to play. They treat conditions that are apparent to the patient and others around them, attracting those that may not be motivated to see different physicians. They can not only help with skin diseases that affect all patients but also can train other physicians to screen for some dermatologic diseases that may have a higher prevalence within the LGBT community. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to help patients better reflect themselves through both surgical and nonsurgical modalities.

Demographics and Definitions

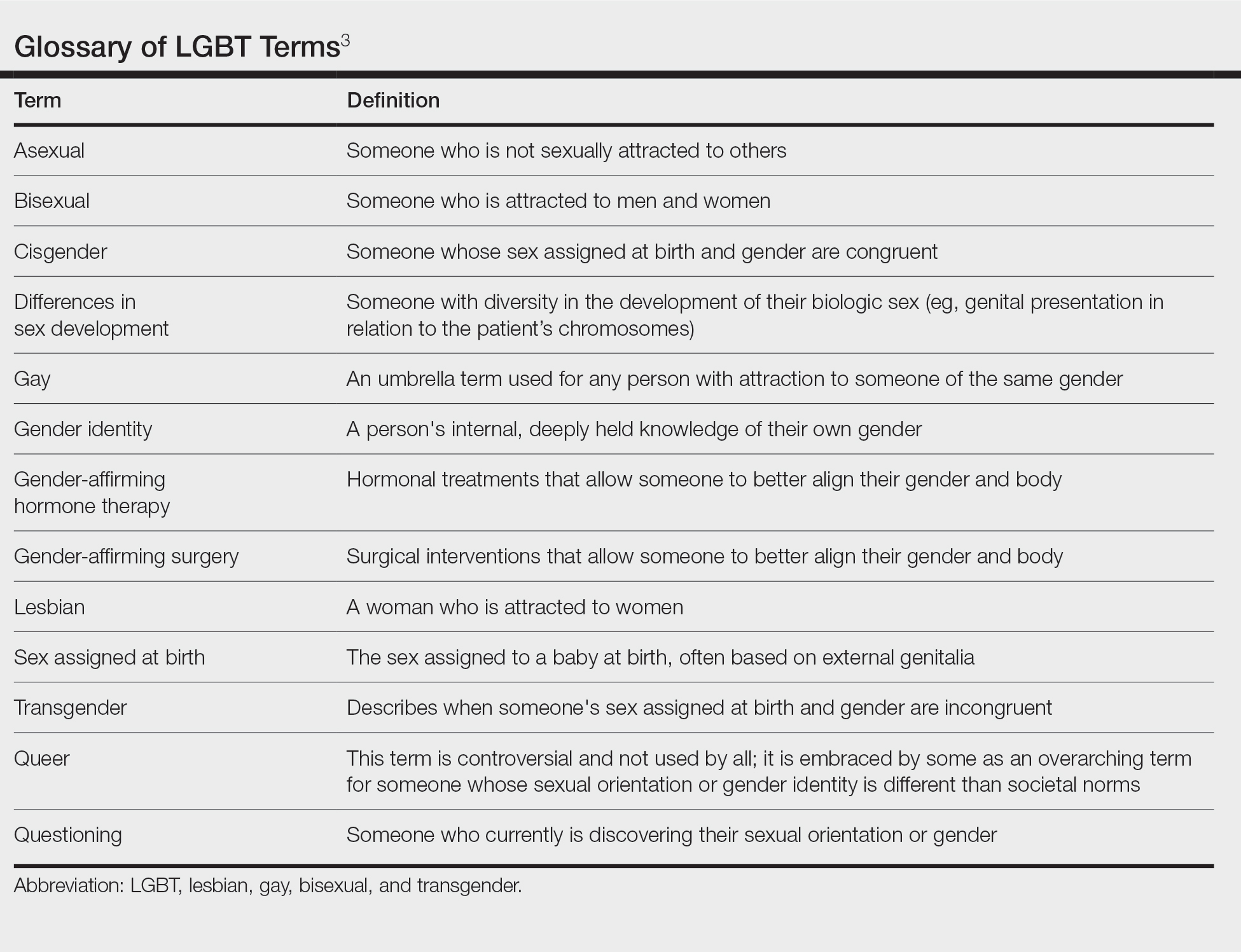

To discuss this topic effectively, it is important to define LGBT terms (Table).3 As a disclaimer, language is fluid. Despite a word or term currently being used and accepted, it quickly can become obsolete. A clinician can always do research, follow the lead of the patient, and respectfully ask questions if there is ever confusion surrounding terminology. Patients do not expect every physician they encounter to be an expert in this subject. What is most important is that patients are approached with an open mind and humility with the goal of providing optimal care.

Although the federal government now uses the term sexual and gender minorities (SGM), the more specific terms lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender usually are preferred.3,4 Other letters are at times added to the acronym LGBT, including Q for questioning or queer, I for intersex, and A for asexual; all of these letters are under the larger SGM umbrella. Because LGBT is the most commonly used acronym in the daily vernacular, it will be the default for this article.

A term describing sexual orientation does not necessarily describe sexual practices. A woman who identifies as straight may have sex with both men and women, and a gay man may not have sex at all. To be more descriptive regarding sexual practices, one may use the terms men who have sex with men or women who have sex with women.3 Because of this nuance, it is important to elicit a sexual history when speaking to all patients in a forward nonjudgmental manner.

The term transgender is used to describe people whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. Two examples of transgender individuals would be transgender women who were assigned male at birth and transgender men who were assigned female at birth. The term transgender is used in opposition to the term cisgender, which is applied to a person whose gender and sex assigned at birth align.3 When a transgender patient presents to a physician, they may want to discuss methods of gender affirmation or transitioning. These terms encompass any action a person may take to align their body or gender expression with that of the gender they identify with. This could be in the form of gender-affirming hormone therapy (ie, estrogen or testosterone treatment) or gender-affirming surgery (ie, “top” and “bottom” surgeries, in which someone surgically treats their chest or genitals, respectively).3

Creating a Safe Space

The physician is responsible for providing a safe space for patients to disclose medically pertinent information. It is then the job of the dermatologist to be cognizant of health concerns that directly affect the LGBT population and to be prepared if one of these concerns should arise. A safe space consists of both the physical location in which the patient encounter will occur and the people that will be conducting and assisting in the patient encounter. Safe spaces provide a patient with reassurance that they will receive care in a judgement-free location. To create a safe space, both the physical and interpersonal aspects must be addressed to provide an environment that strengthens the patient-physician alliance.

Dermatology residents often spend more time with patients than their attending physicians, providing them the opportunity to foster robust relationships with those served. Although they may not be able to change the physical environment, residents can advocate for patients in their departments and show solidarity in subtle ways. One way to show support for the LGBT community is to publicly display a symbol of solidarity, which could be done by wearing a symbol of support on a white coat lapel. Although there are many designs and styles to choose from, one example is the American Medical Student Association pins that combine the caduceus (a common symbol for medicine) with a rainbow design.5 Whichever symbol is chosen, this small gesture allows patients to immediately know that their physician is an ally. Residents also can encourage their department to add a rainbow flag, a pink triangle, or another symbol somewhere prominent in the check-in area that conveys a message of support.6 Many institutions require residents to perform quality improvement projects. The resident can make a substantial difference in their patients’ experiences by revising their office’s intake forms as a quality improvement project, which can be done by including a section on assigned sex at birth separate from gender.7 When inquiring about gender, in addition to “male” and “female,” a space can be left for people that do not identify with the traditional binary. When asking about sexual orientation, inclusive language options can be provided with additional space for self-identification. Finally, residents can incorporate pronouns below their name in their email signature to normalize this disclosure of information.8 These small changes can have a substantial impact on the health care experience of SGM patients.

Medical Problems Encountered

The previously described changes can be implemented by residents to provide better care to SGM patients, a group usually considered to be more burdened by physical and psychological diseases.9 Furthermore, dermatologists can provide care for these patients in ways that other physicians cannot. There are special considerations for LGBT patients, as some dermatologic conditions may be more common in this patient population.

Prior studies have shown that men who have sex with men have a higher rate of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections, and potentially nonmelanoma skin cancer.10-14 Transgender women also have been found to have higher rates of HIV, in addition to a higher incidence of anal human papillomavirus.15,16 Women who have sex with women have been shown to see physicians less frequently and to be less up to date on their pertinent cancer-related screenings.10,17 Although these associations should not dictate the patient encounter, awareness of them will lead to better patient care. Such awareness also can provide further motivation for dermatologists to discuss safe sexual practices, potential initiation of pre-exposure prophylactic antiretroviral therapy, sun-protective practices, and the importance of following up with a primary physician for examinations and age-specific cancer screening.

Transgender patients may present with unique dermatologic concerns. For transgender male patients, testosterone therapy can cause acne breakouts and androgenetic alopecia. Usually considered worse during the start of treatment, hormone-related acne can be managed with topical retinoids, topical and oral antibiotics, and isotretinoin (if severe).18,19 The iPLEDGE system necessary for prescribing isotretinoin to patients in the United States recently has changed its language to “patients who can get pregnant” and “patients who cannot get pregnant,” following urging by the medical community for inclusivity and progress.20,21 This change creates an inclusive space where registration is no longer centered around gender and instead focuses on the presence of anatomy. Although androgenetic alopecia is a side effect of hormone therapy, it may not be unwanted.18 Discussion about patient desires is important. If the alopecia is unwanted, the Endocrine Society recommends treating cisgender and transgender patients the same in terms of treatment modalities.22

Transgender female patients also can experience dermatologic manifestations of gender-affirming hormone therapy. Melasma may develop secondary to estrogen replacement and can be treated with topical bleaching creams, lasers, and phototherapy.23 Hair removal may be pursued for patients with refractory unwanted body hair, with laser hair removal being the most commonly pursued treatment. Patients also may desire cosmetic procedures, such as botulinum toxin or fillers, to augment their physical appearance.24 Providing these services to patients may allow them to better express themselves and live authentically.

Final Thoughts

There is no way to summarize the experience of everyone within a community. Each person has different thoughts, values, and goals. It also is impossible to encompass every topic that is important for SGM patients. The goal of this article is to empower clinicians to be comfortable discussing issues related to sexuality and gender while also offering resources to learn more, allowing optimal care to be provided to this population. Thus, this article is not comprehensive. There are articles to provide further resources and education, such as the continuing medical education series by Yeung et al10,25 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, as well as organizations within medicine, such as the GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality (https://www.glma.org/), and in dermatology, such as GALDA, the Gay and Lesbian Dermatology Association (https://www.glderm.org/). By providing a safe space for our patients and learning about specific health-related risk factors, dermatologists can provide the best possible care to the LGBT community.

Acknowledgments—I thank Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), and Howa Yeung, MD, MSc (Atlanta, Georgia), for their guidance and mentorship in the creation of this article.

- Jones JM. LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup website. Published February 24, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx

- U.S. and world population clock. US Census Bureau website. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/popclock/

- National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. LGBTQIA+ glossary of terms for health care teams. Published February 2, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Glossary-2022.02.22-1.pdf

- National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Coordinating Committee. NIH FY 2016-2020 strategic plan to advance research on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities. NIH website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.edi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/EDI_Public_files/sgm-strategic-plan.pdf

- Caduceus pin—rainbow. American Medical Student Association website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.amsa.org/member-center/store/Caduceus-Pin-Rainbow-p67375123

- 10 tips for caring for LGBTQIA+ patients. Nurse.org website. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://nurse.org/articles/culturally-competent-healthcare-for-LGBTQ-patients/

- Cartron AM, Raiciulescu S, Trinidad JC. Culturally competent care for LGBT patients in dermatology clinics. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:786-787.

- Wareham J. Should you put pronouns in email signatures and social media bios? Forbes website. Published Dec 30, 2019. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiewareham/2020/12/30/should-you-put-pronouns-in-email-signatures-and-social-media-bios/?sh=5b74f1246320

- Hafeez H, Zeshan M, Tahir MA, et al. Healthcare disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9:E1184.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. part II. epidemiology, screening, and disease prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:591-602.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC fact sheet: HIV among gay and bisexual men. CDC website. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-msm-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2016. CDC website. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/CDC_2016_STDS_Report-for508WebSep21_2017_1644.pdf

- Galindo GR, Casey AJ, Yeung A, et al. Community associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among New York City men who have sex with men: qualitative research findings and implications for public health practice. J Community Health. 2012;37:458-467.

- Blashill AJ. Indoor tanning and skin cancer risk among diverse US youth: results from a national sample. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:344-345.

- Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, et al. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:1-17.

- Uaamnuichai S, Panyakhamlerd K, Suwan A, et al. Neovaginal and anal high-risk human papillomavirus DNA among Thai transgender women in gender health clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2021;48:547-549.

- Valanis BG, Bowen DJ, Bassford T, et al. Sexual orientation and health: comparisons in the women’s health initiative sample. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:843-853.

- Wierckx K, Van de Peer F, Verhaeghe E, et al. Short- and long-term clinical skin effects of testosterone treatment in trans men. J Sex Med. 2014;11:222-229.

- Turrion-Merino L, Urech-Garcia-de-la-Vega M, Miguel-Gomez L, et al. Severe acne in female-to-male transgender patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1260-1261.

- Questions and answers on the iPLEDGE REMS. US Food and Drug Administration website. Published October 12, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/questions-and-answers-ipledge-rems#:~:text=The%20modification%20will%20become%20effective,verify%20authorization%20to%20dispense%20isotretinoin

- Gao JL, Thoreson N, Dommasch ED. Navigating iPLEDGE enrollment for transgender and gender diverse patients: a guide for providing culturally competent care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:790-791.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3869-3903.

- Garcia-Rodriguez L, Spiegel JH. Melasma in a transgender woman. Am J Otolaryngol. 2018;39:788-790.

- Ginsberg BA, Calderon M, Seminara NM, et al. A potential role for the dermatologist in the physical transformation of transgender people: a survey of attitudes and practices within the transgender community.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:303-308.

- Yeung H, Luk KM, Chen SC, et al. Dermatologic care for lesbian,gay, bisexual, and transgender persons. part I. terminology, demographics, health disparities, and approaches to care. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:581-589.

The chances are good that at least one patient you saw today could have been provided a better environment to foster your patient-physician relationship. A 2020 Gallup poll revealed that an estimated 5.6% of US adults identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT).1 Based on the estimated US population of 331.7 million individuals on December 3, 2020, this means that approximately 18.6 million identified as LGBT and could potentially require health care services.2 These numbers highlight the increasing need within the medical community to provide quality and accessible care to the LGBT community, and dermatologists have a role to play. They treat conditions that are apparent to the patient and others around them, attracting those that may not be motivated to see different physicians. They can not only help with skin diseases that affect all patients but also can train other physicians to screen for some dermatologic diseases that may have a higher prevalence within the LGBT community. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to help patients better reflect themselves through both surgical and nonsurgical modalities.

Demographics and Definitions

To discuss this topic effectively, it is important to define LGBT terms (Table).3 As a disclaimer, language is fluid. Despite a word or term currently being used and accepted, it quickly can become obsolete. A clinician can always do research, follow the lead of the patient, and respectfully ask questions if there is ever confusion surrounding terminology. Patients do not expect every physician they encounter to be an expert in this subject. What is most important is that patients are approached with an open mind and humility with the goal of providing optimal care.

Although the federal government now uses the term sexual and gender minorities (SGM), the more specific terms lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender usually are preferred.3,4 Other letters are at times added to the acronym LGBT, including Q for questioning or queer, I for intersex, and A for asexual; all of these letters are under the larger SGM umbrella. Because LGBT is the most commonly used acronym in the daily vernacular, it will be the default for this article.

A term describing sexual orientation does not necessarily describe sexual practices. A woman who identifies as straight may have sex with both men and women, and a gay man may not have sex at all. To be more descriptive regarding sexual practices, one may use the terms men who have sex with men or women who have sex with women.3 Because of this nuance, it is important to elicit a sexual history when speaking to all patients in a forward nonjudgmental manner.

The term transgender is used to describe people whose gender identity differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. Two examples of transgender individuals would be transgender women who were assigned male at birth and transgender men who were assigned female at birth. The term transgender is used in opposition to the term cisgender, which is applied to a person whose gender and sex assigned at birth align.3 When a transgender patient presents to a physician, they may want to discuss methods of gender affirmation or transitioning. These terms encompass any action a person may take to align their body or gender expression with that of the gender they identify with. This could be in the form of gender-affirming hormone therapy (ie, estrogen or testosterone treatment) or gender-affirming surgery (ie, “top” and “bottom” surgeries, in which someone surgically treats their chest or genitals, respectively).3

Creating a Safe Space

The physician is responsible for providing a safe space for patients to disclose medically pertinent information. It is then the job of the dermatologist to be cognizant of health concerns that directly affect the LGBT population and to be prepared if one of these concerns should arise. A safe space consists of both the physical location in which the patient encounter will occur and the people that will be conducting and assisting in the patient encounter. Safe spaces provide a patient with reassurance that they will receive care in a judgement-free location. To create a safe space, both the physical and interpersonal aspects must be addressed to provide an environment that strengthens the patient-physician alliance.

Dermatology residents often spend more time with patients than their attending physicians, providing them the opportunity to foster robust relationships with those served. Although they may not be able to change the physical environment, residents can advocate for patients in their departments and show solidarity in subtle ways. One way to show support for the LGBT community is to publicly display a symbol of solidarity, which could be done by wearing a symbol of support on a white coat lapel. Although there are many designs and styles to choose from, one example is the American Medical Student Association pins that combine the caduceus (a common symbol for medicine) with a rainbow design.5 Whichever symbol is chosen, this small gesture allows patients to immediately know that their physician is an ally. Residents also can encourage their department to add a rainbow flag, a pink triangle, or another symbol somewhere prominent in the check-in area that conveys a message of support.6 Many institutions require residents to perform quality improvement projects. The resident can make a substantial difference in their patients’ experiences by revising their office’s intake forms as a quality improvement project, which can be done by including a section on assigned sex at birth separate from gender.7 When inquiring about gender, in addition to “male” and “female,” a space can be left for people that do not identify with the traditional binary. When asking about sexual orientation, inclusive language options can be provided with additional space for self-identification. Finally, residents can incorporate pronouns below their name in their email signature to normalize this disclosure of information.8 These small changes can have a substantial impact on the health care experience of SGM patients.

Medical Problems Encountered

The previously described changes can be implemented by residents to provide better care to SGM patients, a group usually considered to be more burdened by physical and psychological diseases.9 Furthermore, dermatologists can provide care for these patients in ways that other physicians cannot. There are special considerations for LGBT patients, as some dermatologic conditions may be more common in this patient population.

Prior studies have shown that men who have sex with men have a higher rate of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections, and potentially nonmelanoma skin cancer.10-14 Transgender women also have been found to have higher rates of HIV, in addition to a higher incidence of anal human papillomavirus.15,16 Women who have sex with women have been shown to see physicians less frequently and to be less up to date on their pertinent cancer-related screenings.10,17 Although these associations should not dictate the patient encounter, awareness of them will lead to better patient care. Such awareness also can provide further motivation for dermatologists to discuss safe sexual practices, potential initiation of pre-exposure prophylactic antiretroviral therapy, sun-protective practices, and the importance of following up with a primary physician for examinations and age-specific cancer screening.