User login

Neutropenia affects clinical presentation of pulmonary mucormycosis

, based on data from 114 individuals.

Diagnosis of pulmonary mucormycosis (PM), an invasive and potentially life-threatening fungal infection, is often delayed because of its variable presentation, wrote Anne Coste, MD, of La Cavale Blanche Hospital and Brest (France) University Hospital, and colleagues.

Improved diagnostic tools including molecular identification and image-guided lung biopsies are now available in many centers, but relations between underlying conditions, clinical presentations, and diagnostic methods have not been described, they said.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from all cases of PM seen at six hospitals in France between 2008 and 2019. PM cases were based on European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) criteria. Diabetes and trauma were included as additional host factors, and positive serum or tissue PCR (serum qPCR) were included as mycological evidence. Participants also underwent thoracic computed tomography (CT) scans.

The most common underlying conditions among the 114 patients were hematological malignancy (49%), allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (21%), and solid organ transplantation (17%).

Among the 40% of the cases that involved dissemination, the most common sites were the liver (48%), spleen (48%), brain (44%), and kidneys (37%).

A review of radiology findings showed consolidation in a majority of patients (58%), as well as pleural effusion (52%). Other findings included reversed halo sign (RHS, 26%), halo sign (24%), vascular abnormalities (26%), and cavity (23%).

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was present in 46 of 96 patients (50%), and transthoracic lung biopsy was used for diagnosis in 8 of 11 (73%) patients with previous negative BALs.

Seventy patients had neutropenia. Overall, patients with neutropenia were significantly more likely than were those without neutropenia to show an angioinvasive presentation that included both RHS and disease dissemination (P < .05).

In addition, serum qPCR was positive in 42 of 53 patients for whom data were available (79%). Serum qPCR was significantly more likely to be positive in neutropenic patients (91% vs. 62%, P = .02). Positive qPCR was associated with an early diagnosis (P = .03) and treatment onset (P = .01).

Possible reasons for the high rate of disseminated PM in the current study may be the large number of patients with pulmonary involvement, use of body CT data, and availability of autopsy results (for 11% of cases), the researchers wrote in their discussion.

Neutropenia and radiological findings influence disease presentation and contribution of diagnostic tools during PM. Serum qPCR is more contributive in neutropenic patients and BAL examination in nonneutropenic patients. Lung biopsies are highly contributive in case of non-contributive BAL.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design, the inability to calculate sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic methods, and lack of data on patients with COVID-19, the researchers noted. However, the results provide real-life information for clinicians in centers with current mycological platforms, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Coste had no financial conflicts to disclose.

, based on data from 114 individuals.

Diagnosis of pulmonary mucormycosis (PM), an invasive and potentially life-threatening fungal infection, is often delayed because of its variable presentation, wrote Anne Coste, MD, of La Cavale Blanche Hospital and Brest (France) University Hospital, and colleagues.

Improved diagnostic tools including molecular identification and image-guided lung biopsies are now available in many centers, but relations between underlying conditions, clinical presentations, and diagnostic methods have not been described, they said.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from all cases of PM seen at six hospitals in France between 2008 and 2019. PM cases were based on European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) criteria. Diabetes and trauma were included as additional host factors, and positive serum or tissue PCR (serum qPCR) were included as mycological evidence. Participants also underwent thoracic computed tomography (CT) scans.

The most common underlying conditions among the 114 patients were hematological malignancy (49%), allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (21%), and solid organ transplantation (17%).

Among the 40% of the cases that involved dissemination, the most common sites were the liver (48%), spleen (48%), brain (44%), and kidneys (37%).

A review of radiology findings showed consolidation in a majority of patients (58%), as well as pleural effusion (52%). Other findings included reversed halo sign (RHS, 26%), halo sign (24%), vascular abnormalities (26%), and cavity (23%).

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was present in 46 of 96 patients (50%), and transthoracic lung biopsy was used for diagnosis in 8 of 11 (73%) patients with previous negative BALs.

Seventy patients had neutropenia. Overall, patients with neutropenia were significantly more likely than were those without neutropenia to show an angioinvasive presentation that included both RHS and disease dissemination (P < .05).

In addition, serum qPCR was positive in 42 of 53 patients for whom data were available (79%). Serum qPCR was significantly more likely to be positive in neutropenic patients (91% vs. 62%, P = .02). Positive qPCR was associated with an early diagnosis (P = .03) and treatment onset (P = .01).

Possible reasons for the high rate of disseminated PM in the current study may be the large number of patients with pulmonary involvement, use of body CT data, and availability of autopsy results (for 11% of cases), the researchers wrote in their discussion.

Neutropenia and radiological findings influence disease presentation and contribution of diagnostic tools during PM. Serum qPCR is more contributive in neutropenic patients and BAL examination in nonneutropenic patients. Lung biopsies are highly contributive in case of non-contributive BAL.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design, the inability to calculate sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic methods, and lack of data on patients with COVID-19, the researchers noted. However, the results provide real-life information for clinicians in centers with current mycological platforms, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Coste had no financial conflicts to disclose.

, based on data from 114 individuals.

Diagnosis of pulmonary mucormycosis (PM), an invasive and potentially life-threatening fungal infection, is often delayed because of its variable presentation, wrote Anne Coste, MD, of La Cavale Blanche Hospital and Brest (France) University Hospital, and colleagues.

Improved diagnostic tools including molecular identification and image-guided lung biopsies are now available in many centers, but relations between underlying conditions, clinical presentations, and diagnostic methods have not been described, they said.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from all cases of PM seen at six hospitals in France between 2008 and 2019. PM cases were based on European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) criteria. Diabetes and trauma were included as additional host factors, and positive serum or tissue PCR (serum qPCR) were included as mycological evidence. Participants also underwent thoracic computed tomography (CT) scans.

The most common underlying conditions among the 114 patients were hematological malignancy (49%), allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (21%), and solid organ transplantation (17%).

Among the 40% of the cases that involved dissemination, the most common sites were the liver (48%), spleen (48%), brain (44%), and kidneys (37%).

A review of radiology findings showed consolidation in a majority of patients (58%), as well as pleural effusion (52%). Other findings included reversed halo sign (RHS, 26%), halo sign (24%), vascular abnormalities (26%), and cavity (23%).

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was present in 46 of 96 patients (50%), and transthoracic lung biopsy was used for diagnosis in 8 of 11 (73%) patients with previous negative BALs.

Seventy patients had neutropenia. Overall, patients with neutropenia were significantly more likely than were those without neutropenia to show an angioinvasive presentation that included both RHS and disease dissemination (P < .05).

In addition, serum qPCR was positive in 42 of 53 patients for whom data were available (79%). Serum qPCR was significantly more likely to be positive in neutropenic patients (91% vs. 62%, P = .02). Positive qPCR was associated with an early diagnosis (P = .03) and treatment onset (P = .01).

Possible reasons for the high rate of disseminated PM in the current study may be the large number of patients with pulmonary involvement, use of body CT data, and availability of autopsy results (for 11% of cases), the researchers wrote in their discussion.

Neutropenia and radiological findings influence disease presentation and contribution of diagnostic tools during PM. Serum qPCR is more contributive in neutropenic patients and BAL examination in nonneutropenic patients. Lung biopsies are highly contributive in case of non-contributive BAL.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design, the inability to calculate sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic methods, and lack of data on patients with COVID-19, the researchers noted. However, the results provide real-life information for clinicians in centers with current mycological platforms, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Coste had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL CHEST

Offering HPV vaccine at age 9 linked to greater series completion

BALTIMORE – , according to a retrospective cohort study of commercially insured youth presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The research was published ahead of print in Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics.

Changing attitudes

“These findings are novel because they emphasize starting at age 9, and that is different than prior studies that emphasize bundling of these vaccines,” Kevin Ault, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine and a former member of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, said in an interview.

Dr. Ault was not involved in the study but noted that these findings support the AAP’s recommendation to start the HPV vaccine series at age 9. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends giving the first dose of the HPV vaccine at ages 11-12, at the same time as the Tdap and meningitis vaccines. This recommendation to “bundle” the HPV vaccine with the Tdap and meningitis vaccines aims to facilitate provider-family discussion about the HPV vaccine, ideally reducing parent hesitancy and concerns about the vaccines. Multiple studies have shown improved HPV vaccine uptake when providers offer the HPV vaccine at the same time as the Tdap and meningococcal vaccines.

However, shifts in parents’ attitudes have occurred toward the HPV vaccine since those studies on bundling: Concerns about sexual activity have receded while concerns about safety remain high. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society both advise starting the HPV vaccine series at age 9, based on evidence showing that more children complete the series when they get the first shot before age 11 compared to getting it at 11 or 12.

“The bundling was really to vaccinate people by the age of 13, thinking that onset of sexual activity was after that,” study author Sidika Kajtezovic, MD, a resident at Boston Medical Center and Boston University Obstetrics and Gynecology, said in an interview. But Dr. Kajtezovic said she delivers babies for 13-year-old patients. “Kids are having sex sooner or sooner.” It’s also clear that using the bundling strategy is not making up the entire gap right now: Ninety percent of children are getting the meningococcal vaccine while only 49% are getting the HPV vaccine, Dr. Kajtezovic pointed out. “There’s a disconnect happening there, even with the bundling,” she said.

Debundling vaccines

Dr. Kajtezovic and her colleagues used a national database of employee-sponsored health insurance to analyze the records of 100,857 children who were continuously enrolled in a plan from age 9 in 2015 to age 13 in 2019. They calculated the odds of children completing the HPV vaccine series based on whether they started the series before, at the same time as, or after the Tdap vaccination.

Youth who received the HPV vaccine before their Tdap vaccine had 38% greater odds of completing the series – getting both doses – than did those who received the HPV vaccine at the same time as the Tdap vaccine. Meanwhile, in line with prior evidence, those who got the first HPV dose after their Tdap were less likely – 68% lower odds – to complete the two- or three-dose (if starting above age 14) series.

The researchers identified several other factors that were linked to completing the HPV vaccine series. Females had greater odds than did males of completing the series, as did those living in urban, rather than rural, areas. Other factors associated with completing the series included living in the Northeast United States and receiving primary care from a pediatrician rather than a family medicine physician.

Timing is important

“I am encouraged by the findings of this study,” Dr. Ault said in an interview. “However, I would have liked the authors to expand the age range a bit higher. There are data that continuing to discuss the HPV vaccine with parents and teens will increase uptake into the later teen years.”

One challenge is that research shows attendance at primary care visits declines in older adolescence. Since there is no second Tdap or meningitis shot, families need to return for the second HPV vaccine dose after those shots, though they could get the second dose at the same time as other two vaccines if they receive the first dose before age 11. There’s also evidence suggesting that providers find conversations about the HPV vaccine easier when sexual activity is not the focus.

“I often feel that, before a child reaches adolescence, they’re almost, in a way, not sexualized yet, so talking about cancer prevention for an 8- or 9-year-old sometimes sounds a little different to patients versus protecting your 12-year-old, who’s starting to go through adolescence and developing breasts” and other signs of puberty, Dr. Kajtezovic said. Keeping the focus of HPV vaccine discussions on cancer prevention also allows providers to point out the protection against anal cancer, vulvar cancer, vaginal cancer, and head and neck cancer. “They are horrible, and even if they’re treatable, they’re often very hard to treat at an advanced stage,” Dr. Kajtezovic said. “The surgery required is so life disabling and disfiguring.”

The HPV Roundtable advises continuing bundling at practices having success with it but encourages practices to consider earlier vaccination if their uptake is lagging. Quality improvement initiatives, such as earlier electronic medical record prompts and multi-level interventions in pediatric practices, have shown substantial increases in HPV vaccine uptake at 9 and 10 years old. One survey in 2021 found that one in five primary care providers already routinely recommend the HPV vaccine at ages 9-10, and nearly half of others would consider doing so.

“My hope is in the next few years, when [the CDC] refreshes their vaccine recommendations, that they will either unbundle it or move the bar a few years earlier so that you can initiate it to encourage earlier initiation,” Dr. Kajtezovic said.

Dr. Ault had no other disclosures besides prior service on ACIP. Dr. Kajtezovic had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – , according to a retrospective cohort study of commercially insured youth presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The research was published ahead of print in Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics.

Changing attitudes

“These findings are novel because they emphasize starting at age 9, and that is different than prior studies that emphasize bundling of these vaccines,” Kevin Ault, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine and a former member of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, said in an interview.

Dr. Ault was not involved in the study but noted that these findings support the AAP’s recommendation to start the HPV vaccine series at age 9. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends giving the first dose of the HPV vaccine at ages 11-12, at the same time as the Tdap and meningitis vaccines. This recommendation to “bundle” the HPV vaccine with the Tdap and meningitis vaccines aims to facilitate provider-family discussion about the HPV vaccine, ideally reducing parent hesitancy and concerns about the vaccines. Multiple studies have shown improved HPV vaccine uptake when providers offer the HPV vaccine at the same time as the Tdap and meningococcal vaccines.

However, shifts in parents’ attitudes have occurred toward the HPV vaccine since those studies on bundling: Concerns about sexual activity have receded while concerns about safety remain high. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society both advise starting the HPV vaccine series at age 9, based on evidence showing that more children complete the series when they get the first shot before age 11 compared to getting it at 11 or 12.

“The bundling was really to vaccinate people by the age of 13, thinking that onset of sexual activity was after that,” study author Sidika Kajtezovic, MD, a resident at Boston Medical Center and Boston University Obstetrics and Gynecology, said in an interview. But Dr. Kajtezovic said she delivers babies for 13-year-old patients. “Kids are having sex sooner or sooner.” It’s also clear that using the bundling strategy is not making up the entire gap right now: Ninety percent of children are getting the meningococcal vaccine while only 49% are getting the HPV vaccine, Dr. Kajtezovic pointed out. “There’s a disconnect happening there, even with the bundling,” she said.

Debundling vaccines

Dr. Kajtezovic and her colleagues used a national database of employee-sponsored health insurance to analyze the records of 100,857 children who were continuously enrolled in a plan from age 9 in 2015 to age 13 in 2019. They calculated the odds of children completing the HPV vaccine series based on whether they started the series before, at the same time as, or after the Tdap vaccination.

Youth who received the HPV vaccine before their Tdap vaccine had 38% greater odds of completing the series – getting both doses – than did those who received the HPV vaccine at the same time as the Tdap vaccine. Meanwhile, in line with prior evidence, those who got the first HPV dose after their Tdap were less likely – 68% lower odds – to complete the two- or three-dose (if starting above age 14) series.

The researchers identified several other factors that were linked to completing the HPV vaccine series. Females had greater odds than did males of completing the series, as did those living in urban, rather than rural, areas. Other factors associated with completing the series included living in the Northeast United States and receiving primary care from a pediatrician rather than a family medicine physician.

Timing is important

“I am encouraged by the findings of this study,” Dr. Ault said in an interview. “However, I would have liked the authors to expand the age range a bit higher. There are data that continuing to discuss the HPV vaccine with parents and teens will increase uptake into the later teen years.”

One challenge is that research shows attendance at primary care visits declines in older adolescence. Since there is no second Tdap or meningitis shot, families need to return for the second HPV vaccine dose after those shots, though they could get the second dose at the same time as other two vaccines if they receive the first dose before age 11. There’s also evidence suggesting that providers find conversations about the HPV vaccine easier when sexual activity is not the focus.

“I often feel that, before a child reaches adolescence, they’re almost, in a way, not sexualized yet, so talking about cancer prevention for an 8- or 9-year-old sometimes sounds a little different to patients versus protecting your 12-year-old, who’s starting to go through adolescence and developing breasts” and other signs of puberty, Dr. Kajtezovic said. Keeping the focus of HPV vaccine discussions on cancer prevention also allows providers to point out the protection against anal cancer, vulvar cancer, vaginal cancer, and head and neck cancer. “They are horrible, and even if they’re treatable, they’re often very hard to treat at an advanced stage,” Dr. Kajtezovic said. “The surgery required is so life disabling and disfiguring.”

The HPV Roundtable advises continuing bundling at practices having success with it but encourages practices to consider earlier vaccination if their uptake is lagging. Quality improvement initiatives, such as earlier electronic medical record prompts and multi-level interventions in pediatric practices, have shown substantial increases in HPV vaccine uptake at 9 and 10 years old. One survey in 2021 found that one in five primary care providers already routinely recommend the HPV vaccine at ages 9-10, and nearly half of others would consider doing so.

“My hope is in the next few years, when [the CDC] refreshes their vaccine recommendations, that they will either unbundle it or move the bar a few years earlier so that you can initiate it to encourage earlier initiation,” Dr. Kajtezovic said.

Dr. Ault had no other disclosures besides prior service on ACIP. Dr. Kajtezovic had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – , according to a retrospective cohort study of commercially insured youth presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The research was published ahead of print in Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics.

Changing attitudes

“These findings are novel because they emphasize starting at age 9, and that is different than prior studies that emphasize bundling of these vaccines,” Kevin Ault, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine and a former member of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, said in an interview.

Dr. Ault was not involved in the study but noted that these findings support the AAP’s recommendation to start the HPV vaccine series at age 9. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends giving the first dose of the HPV vaccine at ages 11-12, at the same time as the Tdap and meningitis vaccines. This recommendation to “bundle” the HPV vaccine with the Tdap and meningitis vaccines aims to facilitate provider-family discussion about the HPV vaccine, ideally reducing parent hesitancy and concerns about the vaccines. Multiple studies have shown improved HPV vaccine uptake when providers offer the HPV vaccine at the same time as the Tdap and meningococcal vaccines.

However, shifts in parents’ attitudes have occurred toward the HPV vaccine since those studies on bundling: Concerns about sexual activity have receded while concerns about safety remain high. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society both advise starting the HPV vaccine series at age 9, based on evidence showing that more children complete the series when they get the first shot before age 11 compared to getting it at 11 or 12.

“The bundling was really to vaccinate people by the age of 13, thinking that onset of sexual activity was after that,” study author Sidika Kajtezovic, MD, a resident at Boston Medical Center and Boston University Obstetrics and Gynecology, said in an interview. But Dr. Kajtezovic said she delivers babies for 13-year-old patients. “Kids are having sex sooner or sooner.” It’s also clear that using the bundling strategy is not making up the entire gap right now: Ninety percent of children are getting the meningococcal vaccine while only 49% are getting the HPV vaccine, Dr. Kajtezovic pointed out. “There’s a disconnect happening there, even with the bundling,” she said.

Debundling vaccines

Dr. Kajtezovic and her colleagues used a national database of employee-sponsored health insurance to analyze the records of 100,857 children who were continuously enrolled in a plan from age 9 in 2015 to age 13 in 2019. They calculated the odds of children completing the HPV vaccine series based on whether they started the series before, at the same time as, or after the Tdap vaccination.

Youth who received the HPV vaccine before their Tdap vaccine had 38% greater odds of completing the series – getting both doses – than did those who received the HPV vaccine at the same time as the Tdap vaccine. Meanwhile, in line with prior evidence, those who got the first HPV dose after their Tdap were less likely – 68% lower odds – to complete the two- or three-dose (if starting above age 14) series.

The researchers identified several other factors that were linked to completing the HPV vaccine series. Females had greater odds than did males of completing the series, as did those living in urban, rather than rural, areas. Other factors associated with completing the series included living in the Northeast United States and receiving primary care from a pediatrician rather than a family medicine physician.

Timing is important

“I am encouraged by the findings of this study,” Dr. Ault said in an interview. “However, I would have liked the authors to expand the age range a bit higher. There are data that continuing to discuss the HPV vaccine with parents and teens will increase uptake into the later teen years.”

One challenge is that research shows attendance at primary care visits declines in older adolescence. Since there is no second Tdap or meningitis shot, families need to return for the second HPV vaccine dose after those shots, though they could get the second dose at the same time as other two vaccines if they receive the first dose before age 11. There’s also evidence suggesting that providers find conversations about the HPV vaccine easier when sexual activity is not the focus.

“I often feel that, before a child reaches adolescence, they’re almost, in a way, not sexualized yet, so talking about cancer prevention for an 8- or 9-year-old sometimes sounds a little different to patients versus protecting your 12-year-old, who’s starting to go through adolescence and developing breasts” and other signs of puberty, Dr. Kajtezovic said. Keeping the focus of HPV vaccine discussions on cancer prevention also allows providers to point out the protection against anal cancer, vulvar cancer, vaginal cancer, and head and neck cancer. “They are horrible, and even if they’re treatable, they’re often very hard to treat at an advanced stage,” Dr. Kajtezovic said. “The surgery required is so life disabling and disfiguring.”

The HPV Roundtable advises continuing bundling at practices having success with it but encourages practices to consider earlier vaccination if their uptake is lagging. Quality improvement initiatives, such as earlier electronic medical record prompts and multi-level interventions in pediatric practices, have shown substantial increases in HPV vaccine uptake at 9 and 10 years old. One survey in 2021 found that one in five primary care providers already routinely recommend the HPV vaccine at ages 9-10, and nearly half of others would consider doing so.

“My hope is in the next few years, when [the CDC] refreshes their vaccine recommendations, that they will either unbundle it or move the bar a few years earlier so that you can initiate it to encourage earlier initiation,” Dr. Kajtezovic said.

Dr. Ault had no other disclosures besides prior service on ACIP. Dr. Kajtezovic had no disclosures.

AT ACOG 2023

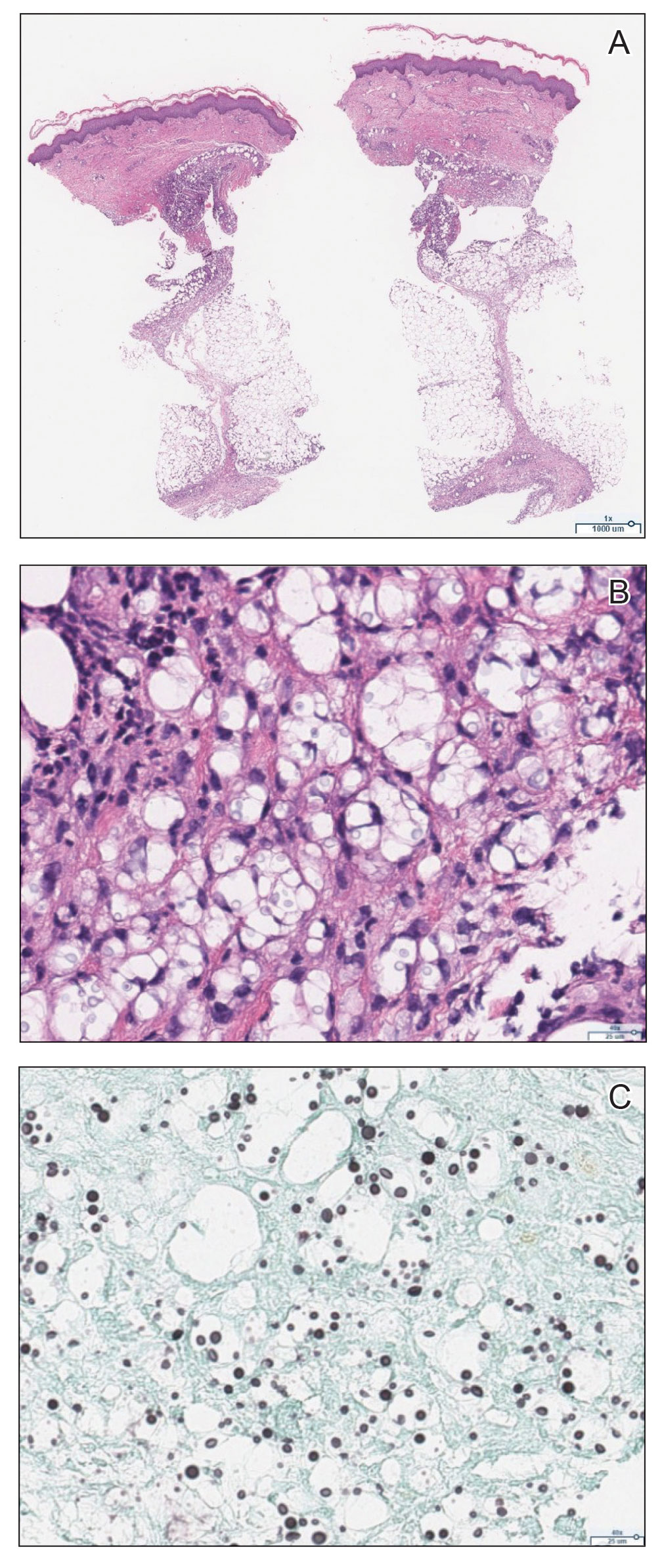

Violaceous Plaque on the Metacarpophalangeal Joints

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

Mycobacterium marinum is a waterborne nontuberculous mycobacterium prevailing in salt water, brackish water, and still or streaming fresh water that infects fish and amphibians worldwide.1,2 Although first described in 1926 as the organism responsible for the demise of fish in an aquarium in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it was not until 1954 that the organism was linked to the cause of infection in humans after it was identified in 80 individuals who had utilized the same swimming pool.1 Due to its ability to secondarily contaminate aquariums, swimming pools, and rivers, this species can give rise to infection in humans, likely though an impaired skin barrier or points of trauma. It commonly is known as swimming pool or fish tank granuloma.3,4

Infection by M marinum commonly presents with lesions on the upper extremities, particularly the hands, that appear approximately 2 to 3 weeks following exposure to the organism.2 Lesions are categorized as superficial (type 1), granulomatous (type 2), or deep (type 3).1 Superficial lesions usually are solitary and painless; may exhibit purulent secretions; and consist of papulonodular, verrucose, or ulcerated granulomatous inflammation.1 These lesions may spread in a sporotrichoidlike pattern or in a linear fashion along lymphatic channels, similar to sporotrichosis. Granulomatous lesions present as solitary or numerous granulomas that typically are swollen, tender, and purulent. Deep lesions are the rarest form and primarily are seen in immunocompromised patients, particularly transplant recipients. Infection can lead to arthritis, tenosynovitis, or osteomyelitis.1

Mycobacterium marinum infection is diagnosed via tissue biopsy for concomitant histopathologic examination and culture from a nonulcerated area close to the lesion.1,2 If cultures do not grow, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis can be conducted. These techniques can exclude other potential diagnoses; however, PCR is unable to provide information on antibiotic susceptibility.1 Biopsy of lesions reveals a nonspecific inflammatory type of reaction within the dermis consisting of lymphocytes, polymorphonuclear cells, and histiocytes.1,4 Additionally, a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate resembling tuberculoid granuloma, sarcoidlike granuloma, or rheumatoidlike nodules also may be observed.1 With staining, the acid-fast organisms can be viewed within histiocytes, sometimes demonstrating transverse bands.4

The preferred treatment of M marinum infection is antibiotic therapy.2 It generally is not recommended to obtain in vitro drug sensitivity testing, as mutational resistance to the commonly utilized drugs is minimal. Microbiologic investigation may be warranted in cases of treatment failure or persistently positive cultures over a period of several months.1,2 Due to its rarity, no clinical trials exist to guide optimal management of M marinum infection, according to a search of ClinicalTrials.gov. Nonetheless, anecdotal evidence of prior cases can direct the selection of antibiotics. Mycobacterium marinum appears to respond to certain tetracyclines, including minocycline followed by doxycycline. Other options include clarithromycin, clarithromycin in combination with rifampin, rifampin in combination with ethambutol, trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.1,2 Surgical debridement or excision may be indicated, especially in an infection involving deep structures, though recurrences have been reported in some individuals following surgery.2,4 Nonspecific treatment such as hyperthermic or liquid nitrogen local treatment have been used experimentally with positive outcomes; however, experience with this treatment modality is limited.2

Sarcoidosis is an immune-mediated systemic disorder that most commonly affects the lungs and skin. Histopathology shows sarcoidal granulomas with features similar to M marinum infection. The clinical presentation often is described as red-brown macules or papules affecting the face, rarely with overlying scale or ulceration.5 Majocchi granuloma is a dermatophyte fungal infection involving the hair follicles. Although application of topical steroids can worsen the involvement, it commonly displays perifollicular pustules,6 which were not seen in our patient. Granuloma annulare is a benign granulomatous disorder that will spontaneously resolve, typically within 2 years of onset. It presents as an annular or arcuate red-brown papule or plaque without overlying scale or ulceration,7 unlike the lesion seen in our patient. Cutaneous lymphoma is a malignant lymphoproliferative disease most commonly affecting middle-aged White men. The presentation is variable and may include an ulcerated plaque8; the lack of systemic symptoms and notable progression over several years in our patient made this a less likely diagnosis.

- Karim S, Devani A, Brassard A. Dermacase. can you identify this condition? Mycobacterium marinum infection. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:53-54.

- Petrini B. Mycobacterium marinum: ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006; 25:609-613. doi:10.1007/s10096-006-0201-4

- Gray SF, Smith RS, Reynolds NJ, et al. Fish tank granuloma. BMJ. 1990;300:1069-1070. doi:10.1136/bmj.300.6731.1069

- Philpott JA Jr, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, et al. Swimming pool granuloma: a study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158-162. doi:10.1001/archderm.1963.01590200046008

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:685-702. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.010

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives [published online May 22, 2018]. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760. doi:10.2147/IDR.S145027

- Joshi TP, Duvic M. Granuloma annulare: an updated review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:37-50. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00636-1

- Charli-Joseph YV, Gatica-Torres M, Pincus LB. Approach to cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates: when to consider lymphoma? Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:351-374. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.185698

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

Mycobacterium marinum is a waterborne nontuberculous mycobacterium prevailing in salt water, brackish water, and still or streaming fresh water that infects fish and amphibians worldwide.1,2 Although first described in 1926 as the organism responsible for the demise of fish in an aquarium in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it was not until 1954 that the organism was linked to the cause of infection in humans after it was identified in 80 individuals who had utilized the same swimming pool.1 Due to its ability to secondarily contaminate aquariums, swimming pools, and rivers, this species can give rise to infection in humans, likely though an impaired skin barrier or points of trauma. It commonly is known as swimming pool or fish tank granuloma.3,4

Infection by M marinum commonly presents with lesions on the upper extremities, particularly the hands, that appear approximately 2 to 3 weeks following exposure to the organism.2 Lesions are categorized as superficial (type 1), granulomatous (type 2), or deep (type 3).1 Superficial lesions usually are solitary and painless; may exhibit purulent secretions; and consist of papulonodular, verrucose, or ulcerated granulomatous inflammation.1 These lesions may spread in a sporotrichoidlike pattern or in a linear fashion along lymphatic channels, similar to sporotrichosis. Granulomatous lesions present as solitary or numerous granulomas that typically are swollen, tender, and purulent. Deep lesions are the rarest form and primarily are seen in immunocompromised patients, particularly transplant recipients. Infection can lead to arthritis, tenosynovitis, or osteomyelitis.1

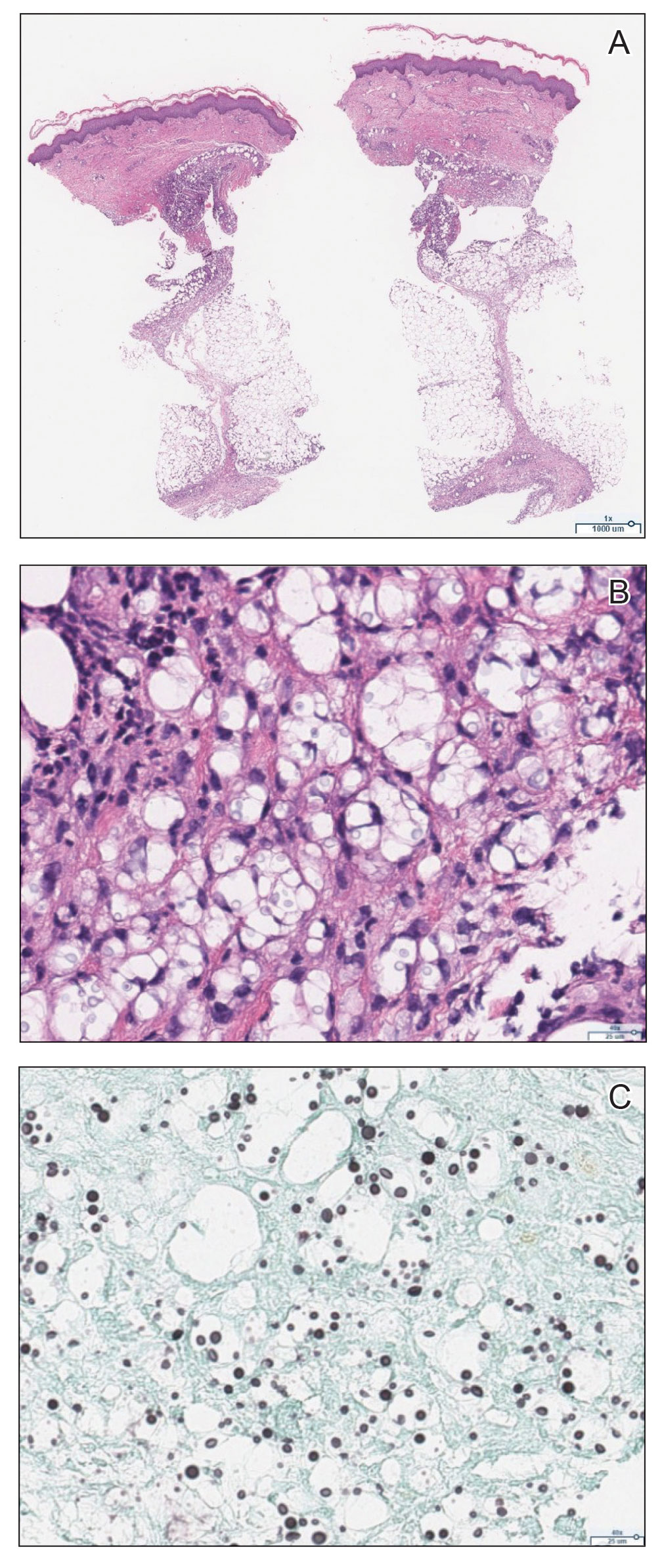

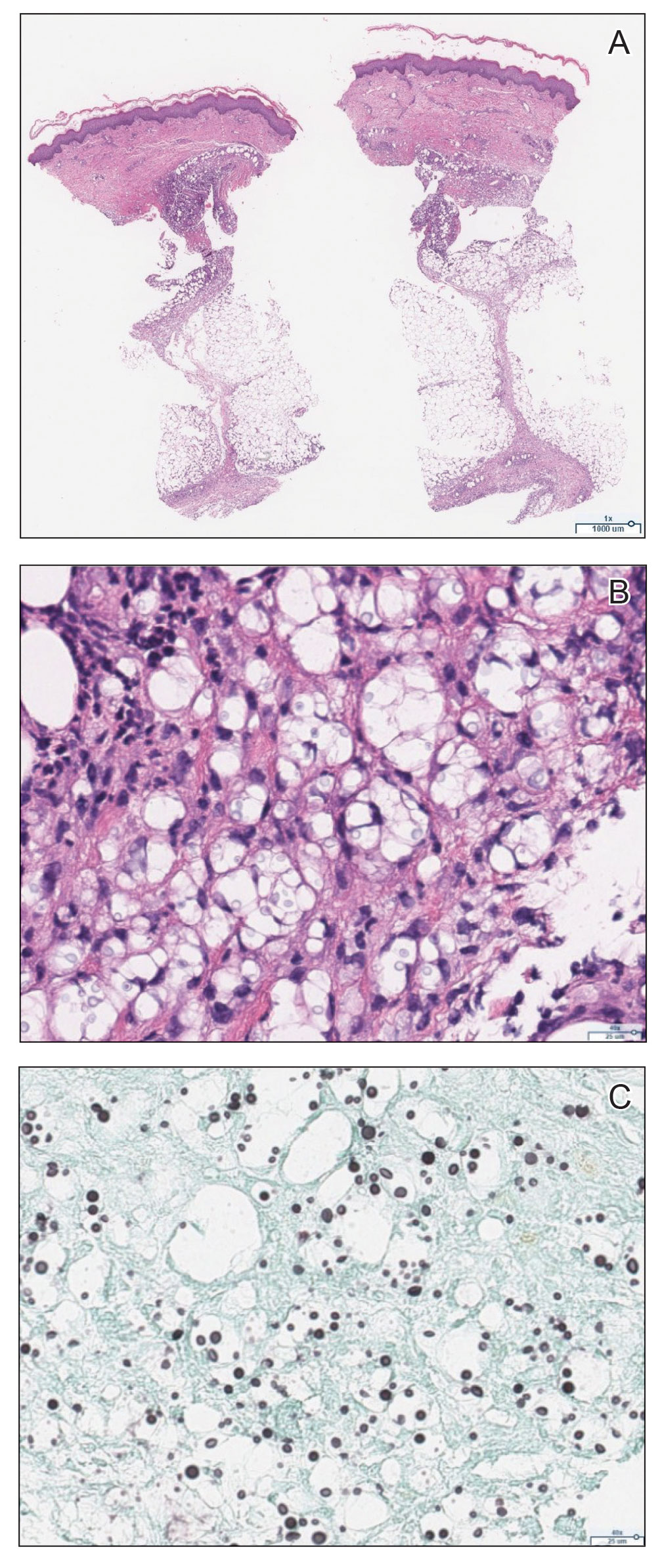

Mycobacterium marinum infection is diagnosed via tissue biopsy for concomitant histopathologic examination and culture from a nonulcerated area close to the lesion.1,2 If cultures do not grow, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis can be conducted. These techniques can exclude other potential diagnoses; however, PCR is unable to provide information on antibiotic susceptibility.1 Biopsy of lesions reveals a nonspecific inflammatory type of reaction within the dermis consisting of lymphocytes, polymorphonuclear cells, and histiocytes.1,4 Additionally, a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate resembling tuberculoid granuloma, sarcoidlike granuloma, or rheumatoidlike nodules also may be observed.1 With staining, the acid-fast organisms can be viewed within histiocytes, sometimes demonstrating transverse bands.4

The preferred treatment of M marinum infection is antibiotic therapy.2 It generally is not recommended to obtain in vitro drug sensitivity testing, as mutational resistance to the commonly utilized drugs is minimal. Microbiologic investigation may be warranted in cases of treatment failure or persistently positive cultures over a period of several months.1,2 Due to its rarity, no clinical trials exist to guide optimal management of M marinum infection, according to a search of ClinicalTrials.gov. Nonetheless, anecdotal evidence of prior cases can direct the selection of antibiotics. Mycobacterium marinum appears to respond to certain tetracyclines, including minocycline followed by doxycycline. Other options include clarithromycin, clarithromycin in combination with rifampin, rifampin in combination with ethambutol, trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.1,2 Surgical debridement or excision may be indicated, especially in an infection involving deep structures, though recurrences have been reported in some individuals following surgery.2,4 Nonspecific treatment such as hyperthermic or liquid nitrogen local treatment have been used experimentally with positive outcomes; however, experience with this treatment modality is limited.2

Sarcoidosis is an immune-mediated systemic disorder that most commonly affects the lungs and skin. Histopathology shows sarcoidal granulomas with features similar to M marinum infection. The clinical presentation often is described as red-brown macules or papules affecting the face, rarely with overlying scale or ulceration.5 Majocchi granuloma is a dermatophyte fungal infection involving the hair follicles. Although application of topical steroids can worsen the involvement, it commonly displays perifollicular pustules,6 which were not seen in our patient. Granuloma annulare is a benign granulomatous disorder that will spontaneously resolve, typically within 2 years of onset. It presents as an annular or arcuate red-brown papule or plaque without overlying scale or ulceration,7 unlike the lesion seen in our patient. Cutaneous lymphoma is a malignant lymphoproliferative disease most commonly affecting middle-aged White men. The presentation is variable and may include an ulcerated plaque8; the lack of systemic symptoms and notable progression over several years in our patient made this a less likely diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

Mycobacterium marinum is a waterborne nontuberculous mycobacterium prevailing in salt water, brackish water, and still or streaming fresh water that infects fish and amphibians worldwide.1,2 Although first described in 1926 as the organism responsible for the demise of fish in an aquarium in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it was not until 1954 that the organism was linked to the cause of infection in humans after it was identified in 80 individuals who had utilized the same swimming pool.1 Due to its ability to secondarily contaminate aquariums, swimming pools, and rivers, this species can give rise to infection in humans, likely though an impaired skin barrier or points of trauma. It commonly is known as swimming pool or fish tank granuloma.3,4

Infection by M marinum commonly presents with lesions on the upper extremities, particularly the hands, that appear approximately 2 to 3 weeks following exposure to the organism.2 Lesions are categorized as superficial (type 1), granulomatous (type 2), or deep (type 3).1 Superficial lesions usually are solitary and painless; may exhibit purulent secretions; and consist of papulonodular, verrucose, or ulcerated granulomatous inflammation.1 These lesions may spread in a sporotrichoidlike pattern or in a linear fashion along lymphatic channels, similar to sporotrichosis. Granulomatous lesions present as solitary or numerous granulomas that typically are swollen, tender, and purulent. Deep lesions are the rarest form and primarily are seen in immunocompromised patients, particularly transplant recipients. Infection can lead to arthritis, tenosynovitis, or osteomyelitis.1

Mycobacterium marinum infection is diagnosed via tissue biopsy for concomitant histopathologic examination and culture from a nonulcerated area close to the lesion.1,2 If cultures do not grow, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis can be conducted. These techniques can exclude other potential diagnoses; however, PCR is unable to provide information on antibiotic susceptibility.1 Biopsy of lesions reveals a nonspecific inflammatory type of reaction within the dermis consisting of lymphocytes, polymorphonuclear cells, and histiocytes.1,4 Additionally, a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate resembling tuberculoid granuloma, sarcoidlike granuloma, or rheumatoidlike nodules also may be observed.1 With staining, the acid-fast organisms can be viewed within histiocytes, sometimes demonstrating transverse bands.4

The preferred treatment of M marinum infection is antibiotic therapy.2 It generally is not recommended to obtain in vitro drug sensitivity testing, as mutational resistance to the commonly utilized drugs is minimal. Microbiologic investigation may be warranted in cases of treatment failure or persistently positive cultures over a period of several months.1,2 Due to its rarity, no clinical trials exist to guide optimal management of M marinum infection, according to a search of ClinicalTrials.gov. Nonetheless, anecdotal evidence of prior cases can direct the selection of antibiotics. Mycobacterium marinum appears to respond to certain tetracyclines, including minocycline followed by doxycycline. Other options include clarithromycin, clarithromycin in combination with rifampin, rifampin in combination with ethambutol, trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.1,2 Surgical debridement or excision may be indicated, especially in an infection involving deep structures, though recurrences have been reported in some individuals following surgery.2,4 Nonspecific treatment such as hyperthermic or liquid nitrogen local treatment have been used experimentally with positive outcomes; however, experience with this treatment modality is limited.2

Sarcoidosis is an immune-mediated systemic disorder that most commonly affects the lungs and skin. Histopathology shows sarcoidal granulomas with features similar to M marinum infection. The clinical presentation often is described as red-brown macules or papules affecting the face, rarely with overlying scale or ulceration.5 Majocchi granuloma is a dermatophyte fungal infection involving the hair follicles. Although application of topical steroids can worsen the involvement, it commonly displays perifollicular pustules,6 which were not seen in our patient. Granuloma annulare is a benign granulomatous disorder that will spontaneously resolve, typically within 2 years of onset. It presents as an annular or arcuate red-brown papule or plaque without overlying scale or ulceration,7 unlike the lesion seen in our patient. Cutaneous lymphoma is a malignant lymphoproliferative disease most commonly affecting middle-aged White men. The presentation is variable and may include an ulcerated plaque8; the lack of systemic symptoms and notable progression over several years in our patient made this a less likely diagnosis.

- Karim S, Devani A, Brassard A. Dermacase. can you identify this condition? Mycobacterium marinum infection. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:53-54.

- Petrini B. Mycobacterium marinum: ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006; 25:609-613. doi:10.1007/s10096-006-0201-4

- Gray SF, Smith RS, Reynolds NJ, et al. Fish tank granuloma. BMJ. 1990;300:1069-1070. doi:10.1136/bmj.300.6731.1069

- Philpott JA Jr, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, et al. Swimming pool granuloma: a study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158-162. doi:10.1001/archderm.1963.01590200046008

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:685-702. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.010

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives [published online May 22, 2018]. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760. doi:10.2147/IDR.S145027

- Joshi TP, Duvic M. Granuloma annulare: an updated review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:37-50. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00636-1

- Charli-Joseph YV, Gatica-Torres M, Pincus LB. Approach to cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates: when to consider lymphoma? Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:351-374. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.185698

- Karim S, Devani A, Brassard A. Dermacase. can you identify this condition? Mycobacterium marinum infection. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:53-54.

- Petrini B. Mycobacterium marinum: ubiquitous agent of waterborne granulomatous skin infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006; 25:609-613. doi:10.1007/s10096-006-0201-4

- Gray SF, Smith RS, Reynolds NJ, et al. Fish tank granuloma. BMJ. 1990;300:1069-1070. doi:10.1136/bmj.300.6731.1069

- Philpott JA Jr, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, et al. Swimming pool granuloma: a study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158-162. doi:10.1001/archderm.1963.01590200046008

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:685-702. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.010

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives [published online May 22, 2018]. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760. doi:10.2147/IDR.S145027

- Joshi TP, Duvic M. Granuloma annulare: an updated review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:37-50. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00636-1

- Charli-Joseph YV, Gatica-Torres M, Pincus LB. Approach to cutaneous lymphoid infiltrates: when to consider lymphoma? Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:351-374. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.185698

A 24-year-old man presented with a slowly growing, asymptomatic lesion on the left dorsal fourth and fifth metacarpophalangeal joints of 5 years’ duration that was recalcitrant to potent topical corticosteroids. Physical examination revealed an L-shaped, violaceous, firm plaque with focal areas of serous crust. There was no regional lymphadenopathy or lymphangitic spread. The patient had no history of recent travel, and he reported no associated pain or signs of systemic infection.

Family physicians get lowest net return for HPV vaccine

Family physicians receive less private insurer reimbursement for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine than do pediatricians, according to a new analysis in Family Medicine.

HPV is the most expensive of all routine pediatric vaccines and the reimbursement by third-party payers varies widely. The concerns about HPV reimbursement often appear on clinician surveys.

This study, led by Yenan Zhu, PhD, who was with the department of public health sciences, college of medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, at the time of the research, found that, on average, pediatricians received higher reimbursement ($216.07) for HPV vaccine cost when compared with family physicians ($211.33), internists ($212.97), nurse practitioners ($212.91), and “other” clinicians who administer the vaccine ($213.29) (P values for all comparisons were < .001).

The final sample for this study included 34,247 clinicians.

The net return from vaccine cost reimbursements was lowest for family physicians ($0.34 per HPV vaccine dose administered) and highest for pediatricians ($5.08 per HPV vaccine dose administered).

“Adequate cost reimbursement by third-party payers is a critical enabling factor for clinicians to continue offering vaccines,” the authors wrote.

The authors concluded that “reimbursement for HPV vaccine costs by private payers is adequate; however, return margins are small for nonpediatric specialties.”

CDC, AAP differ in recommendations

In the United States, private insurers use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine list price as a benchmark.

Overall in this study, HPV vaccine cost reimbursement by private payers was at or above the CDC list price of $210.99 but below the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations ($263.74).

The study found that every $1 increment in return was associated with an increase in HPV vaccine doses administered. That was highest for family physicians at 0.08% per dollar.

The modeling showed that changing the HPV vaccine reimbursement to the AAP-recommended level could translate to “an estimated 18,643 additional HPV vaccine doses administrated by pediatricians, 4,041 additional doses by family physicians, and 433 doses by ‘other’ specialties in 2017-2018.”

The authors noted that U.S. vaccination coverage has improved in recent years but initiation and completion rates are lower among privately insured adolescents (4.6% lower for initiation and 2.0% points lower for completion in 2021), compared with adolescents covered under public insurance.

Why the difference among specialties?

Variation in reimbursements might be tied to the ability to negotiate reimbursements for adolescent vaccines, the authors said.

“For instance, pediatricians may be able to negotiate higher cost reimbursement, compared with nonpediatric specialties, given that adolescents constitute a large fraction of their patient volume,” they wrote.

Dr. Zhu and colleagues wrote that it should be noted that HPV vaccine cost reimbursement to family practitioners was considerably less than other specialties and they are barely breaking even though they have the second-highest volume of HPV vaccinations (after pediatricians).

The authors acknowledged that it may not be possible to raise reimbursement to the AAP level, but added that “a reasonable increase that can cover direct and indirect expenses (acquisition cost, storage cost, personnel cost for monitoring inventory, insurance, waste, and lost opportunity costs) will reduce the financial strain on nonpediatric clinicians.” That may encourage clinicians to stock and offer the vaccine.

Limitations

The researchers acknowledged several limitations. The models did not account for factors such as vaccination bundling, physicians’ recommendation style or differences in knowledge of the vaccination schedule.

The models were also not able to adjust for whether a clinic had reminder prompts in the electronic health records, the overhead costs of vaccines, or vaccine knowledge or hesitancy on the part of the adolescents’ parents.

Additionally, they used data from one private payer, which limits generalizability.

Researchers identified a sample of adolescents eligible for the HPV vaccine (9-14 years old) enrolled in a large private health insurance plan during 2017-2018. Data from states with universal or universal select vaccine purchasing were excluded. These states included Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, South Dakota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

One coauthor reported receiving a consulting fee from Merck on unrelated projects. Another coauthor has provided consultancy to Value Analytics Labs on unrelated projects. All other authors declared no competing interests.

Family physicians receive less private insurer reimbursement for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine than do pediatricians, according to a new analysis in Family Medicine.

HPV is the most expensive of all routine pediatric vaccines and the reimbursement by third-party payers varies widely. The concerns about HPV reimbursement often appear on clinician surveys.

This study, led by Yenan Zhu, PhD, who was with the department of public health sciences, college of medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, at the time of the research, found that, on average, pediatricians received higher reimbursement ($216.07) for HPV vaccine cost when compared with family physicians ($211.33), internists ($212.97), nurse practitioners ($212.91), and “other” clinicians who administer the vaccine ($213.29) (P values for all comparisons were < .001).

The final sample for this study included 34,247 clinicians.

The net return from vaccine cost reimbursements was lowest for family physicians ($0.34 per HPV vaccine dose administered) and highest for pediatricians ($5.08 per HPV vaccine dose administered).

“Adequate cost reimbursement by third-party payers is a critical enabling factor for clinicians to continue offering vaccines,” the authors wrote.

The authors concluded that “reimbursement for HPV vaccine costs by private payers is adequate; however, return margins are small for nonpediatric specialties.”

CDC, AAP differ in recommendations

In the United States, private insurers use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine list price as a benchmark.

Overall in this study, HPV vaccine cost reimbursement by private payers was at or above the CDC list price of $210.99 but below the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations ($263.74).

The study found that every $1 increment in return was associated with an increase in HPV vaccine doses administered. That was highest for family physicians at 0.08% per dollar.

The modeling showed that changing the HPV vaccine reimbursement to the AAP-recommended level could translate to “an estimated 18,643 additional HPV vaccine doses administrated by pediatricians, 4,041 additional doses by family physicians, and 433 doses by ‘other’ specialties in 2017-2018.”

The authors noted that U.S. vaccination coverage has improved in recent years but initiation and completion rates are lower among privately insured adolescents (4.6% lower for initiation and 2.0% points lower for completion in 2021), compared with adolescents covered under public insurance.

Why the difference among specialties?

Variation in reimbursements might be tied to the ability to negotiate reimbursements for adolescent vaccines, the authors said.

“For instance, pediatricians may be able to negotiate higher cost reimbursement, compared with nonpediatric specialties, given that adolescents constitute a large fraction of their patient volume,” they wrote.

Dr. Zhu and colleagues wrote that it should be noted that HPV vaccine cost reimbursement to family practitioners was considerably less than other specialties and they are barely breaking even though they have the second-highest volume of HPV vaccinations (after pediatricians).

The authors acknowledged that it may not be possible to raise reimbursement to the AAP level, but added that “a reasonable increase that can cover direct and indirect expenses (acquisition cost, storage cost, personnel cost for monitoring inventory, insurance, waste, and lost opportunity costs) will reduce the financial strain on nonpediatric clinicians.” That may encourage clinicians to stock and offer the vaccine.

Limitations

The researchers acknowledged several limitations. The models did not account for factors such as vaccination bundling, physicians’ recommendation style or differences in knowledge of the vaccination schedule.

The models were also not able to adjust for whether a clinic had reminder prompts in the electronic health records, the overhead costs of vaccines, or vaccine knowledge or hesitancy on the part of the adolescents’ parents.

Additionally, they used data from one private payer, which limits generalizability.

Researchers identified a sample of adolescents eligible for the HPV vaccine (9-14 years old) enrolled in a large private health insurance plan during 2017-2018. Data from states with universal or universal select vaccine purchasing were excluded. These states included Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, South Dakota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

One coauthor reported receiving a consulting fee from Merck on unrelated projects. Another coauthor has provided consultancy to Value Analytics Labs on unrelated projects. All other authors declared no competing interests.

Family physicians receive less private insurer reimbursement for the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine than do pediatricians, according to a new analysis in Family Medicine.

HPV is the most expensive of all routine pediatric vaccines and the reimbursement by third-party payers varies widely. The concerns about HPV reimbursement often appear on clinician surveys.

This study, led by Yenan Zhu, PhD, who was with the department of public health sciences, college of medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, at the time of the research, found that, on average, pediatricians received higher reimbursement ($216.07) for HPV vaccine cost when compared with family physicians ($211.33), internists ($212.97), nurse practitioners ($212.91), and “other” clinicians who administer the vaccine ($213.29) (P values for all comparisons were < .001).

The final sample for this study included 34,247 clinicians.

The net return from vaccine cost reimbursements was lowest for family physicians ($0.34 per HPV vaccine dose administered) and highest for pediatricians ($5.08 per HPV vaccine dose administered).

“Adequate cost reimbursement by third-party payers is a critical enabling factor for clinicians to continue offering vaccines,” the authors wrote.

The authors concluded that “reimbursement for HPV vaccine costs by private payers is adequate; however, return margins are small for nonpediatric specialties.”

CDC, AAP differ in recommendations

In the United States, private insurers use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine list price as a benchmark.

Overall in this study, HPV vaccine cost reimbursement by private payers was at or above the CDC list price of $210.99 but below the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations ($263.74).

The study found that every $1 increment in return was associated with an increase in HPV vaccine doses administered. That was highest for family physicians at 0.08% per dollar.

The modeling showed that changing the HPV vaccine reimbursement to the AAP-recommended level could translate to “an estimated 18,643 additional HPV vaccine doses administrated by pediatricians, 4,041 additional doses by family physicians, and 433 doses by ‘other’ specialties in 2017-2018.”

The authors noted that U.S. vaccination coverage has improved in recent years but initiation and completion rates are lower among privately insured adolescents (4.6% lower for initiation and 2.0% points lower for completion in 2021), compared with adolescents covered under public insurance.

Why the difference among specialties?

Variation in reimbursements might be tied to the ability to negotiate reimbursements for adolescent vaccines, the authors said.

“For instance, pediatricians may be able to negotiate higher cost reimbursement, compared with nonpediatric specialties, given that adolescents constitute a large fraction of their patient volume,” they wrote.

Dr. Zhu and colleagues wrote that it should be noted that HPV vaccine cost reimbursement to family practitioners was considerably less than other specialties and they are barely breaking even though they have the second-highest volume of HPV vaccinations (after pediatricians).

The authors acknowledged that it may not be possible to raise reimbursement to the AAP level, but added that “a reasonable increase that can cover direct and indirect expenses (acquisition cost, storage cost, personnel cost for monitoring inventory, insurance, waste, and lost opportunity costs) will reduce the financial strain on nonpediatric clinicians.” That may encourage clinicians to stock and offer the vaccine.

Limitations

The researchers acknowledged several limitations. The models did not account for factors such as vaccination bundling, physicians’ recommendation style or differences in knowledge of the vaccination schedule.

The models were also not able to adjust for whether a clinic had reminder prompts in the electronic health records, the overhead costs of vaccines, or vaccine knowledge or hesitancy on the part of the adolescents’ parents.

Additionally, they used data from one private payer, which limits generalizability.

Researchers identified a sample of adolescents eligible for the HPV vaccine (9-14 years old) enrolled in a large private health insurance plan during 2017-2018. Data from states with universal or universal select vaccine purchasing were excluded. These states included Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Massachusetts, South Dakota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

One coauthor reported receiving a consulting fee from Merck on unrelated projects. Another coauthor has provided consultancy to Value Analytics Labs on unrelated projects. All other authors declared no competing interests.

FROM FAMILY MEDICINE

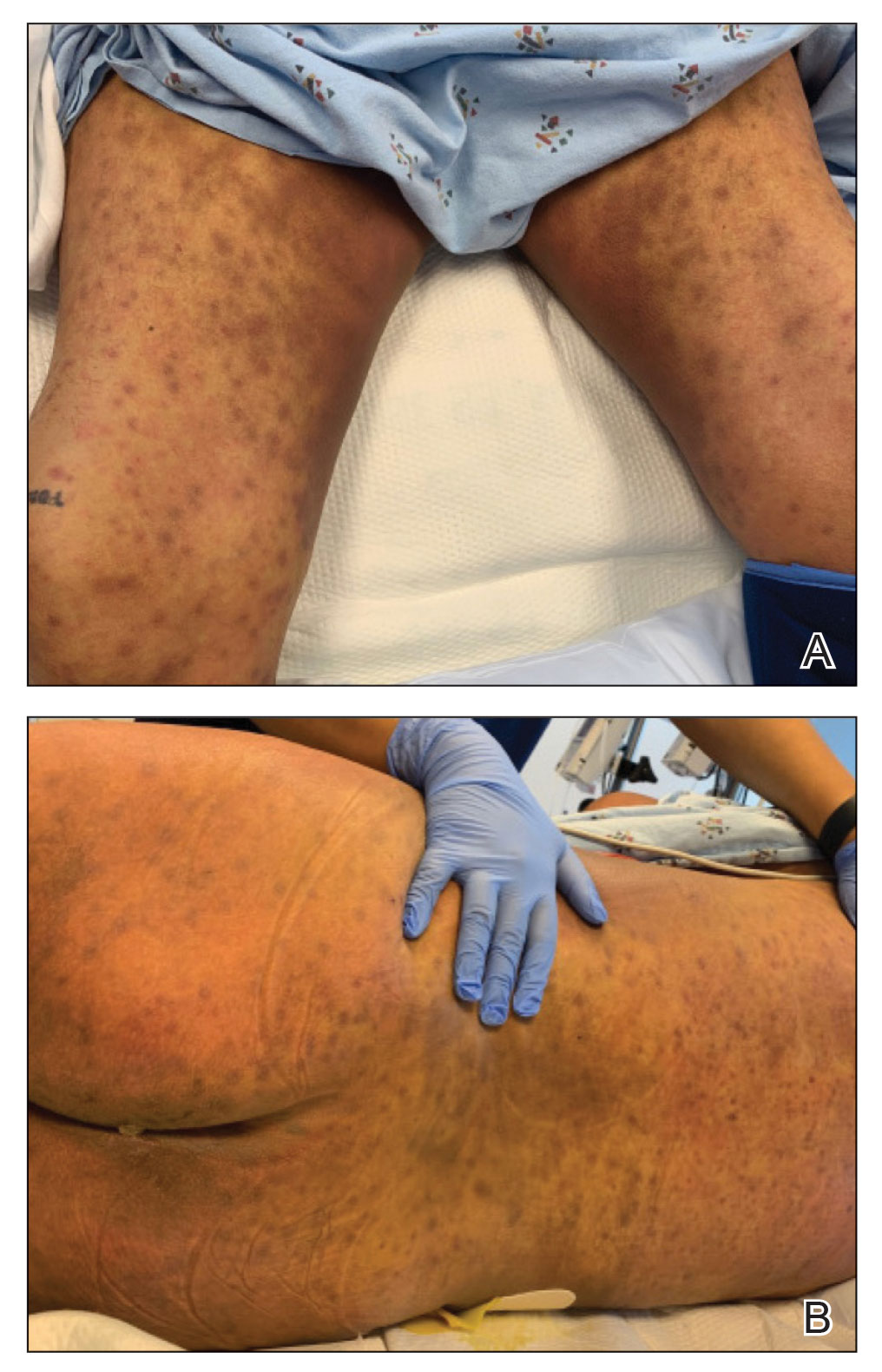

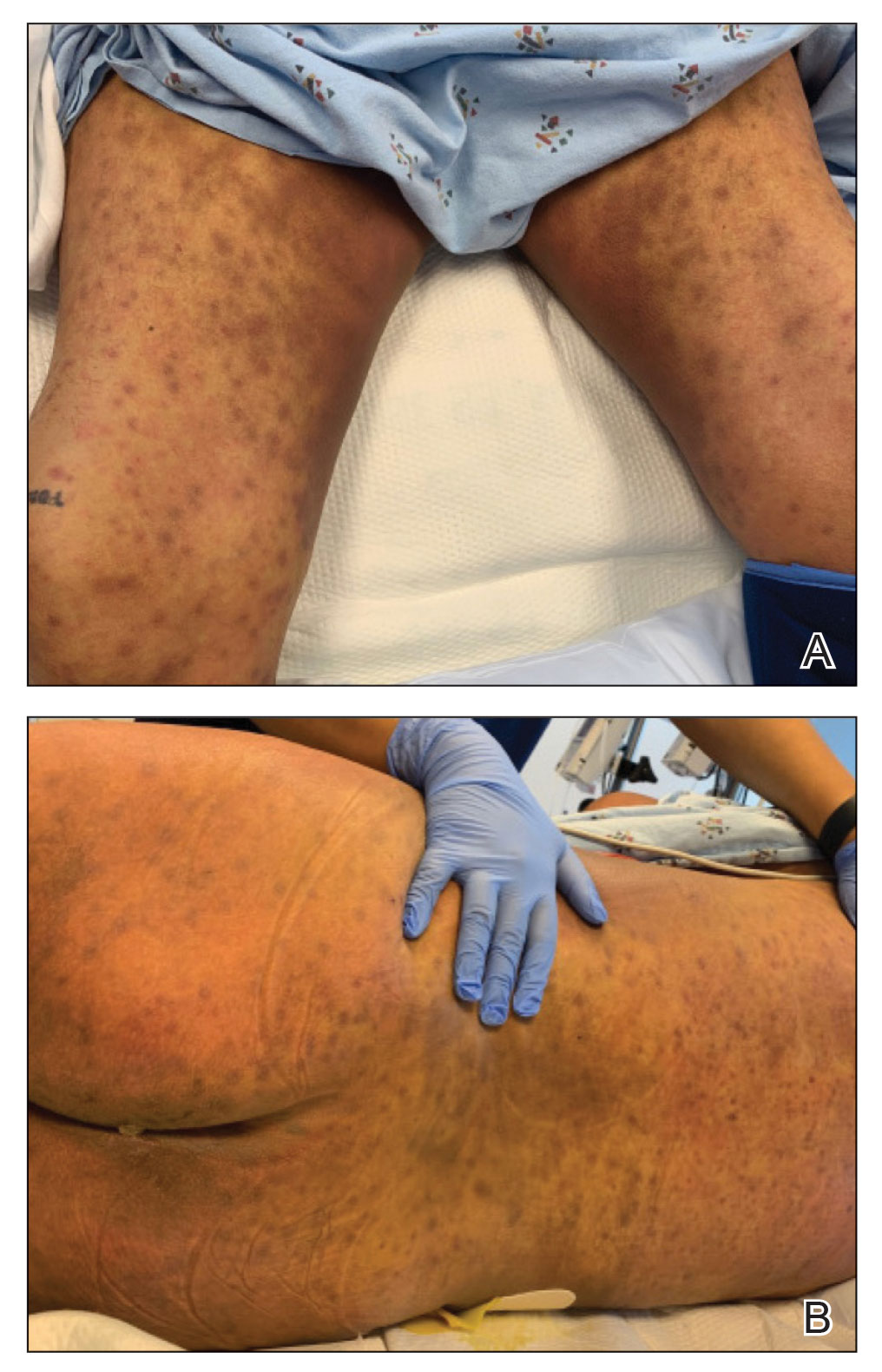

Erythematous Plaques on the Dorsal Aspect of the Hand

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

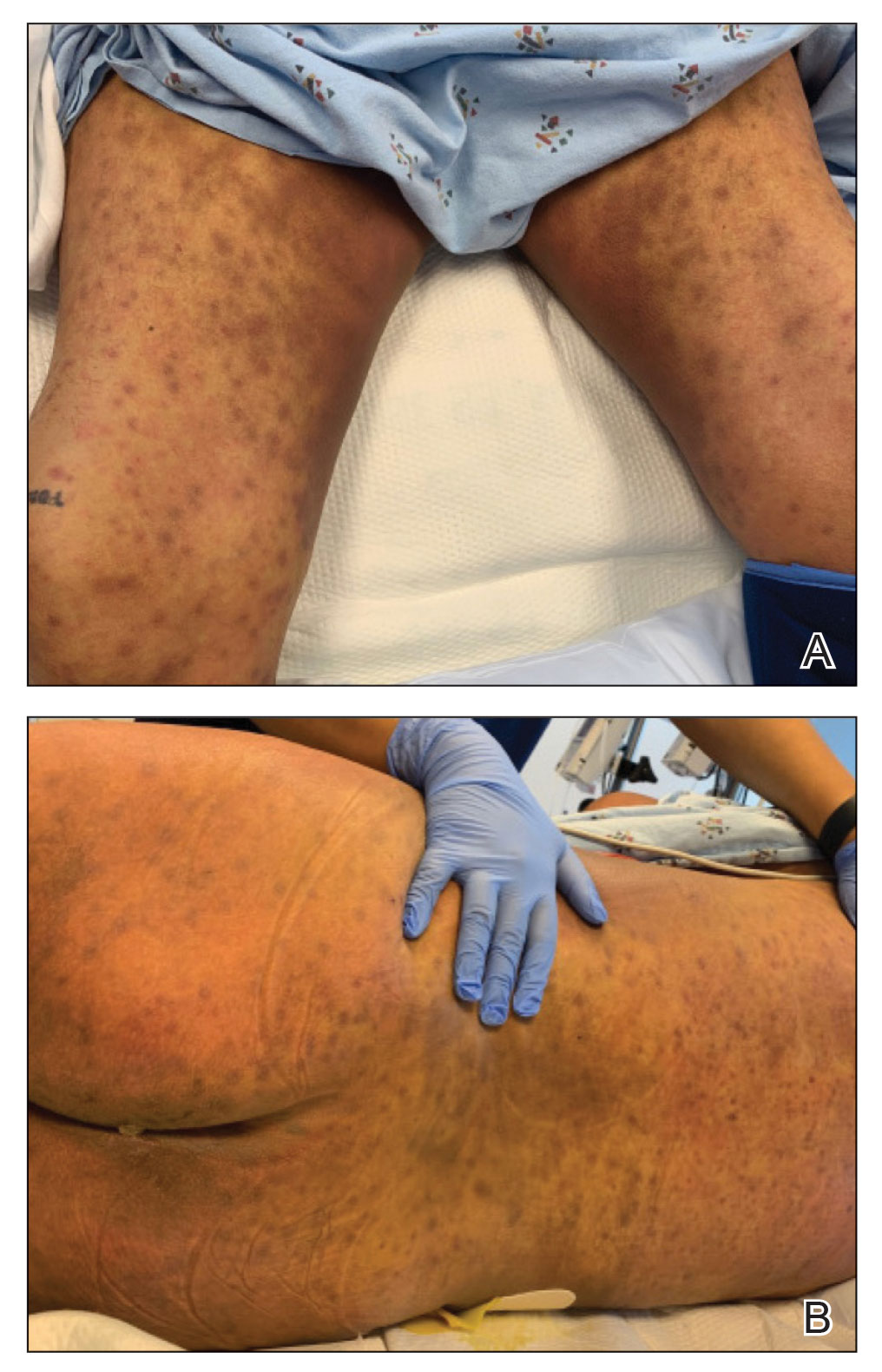

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

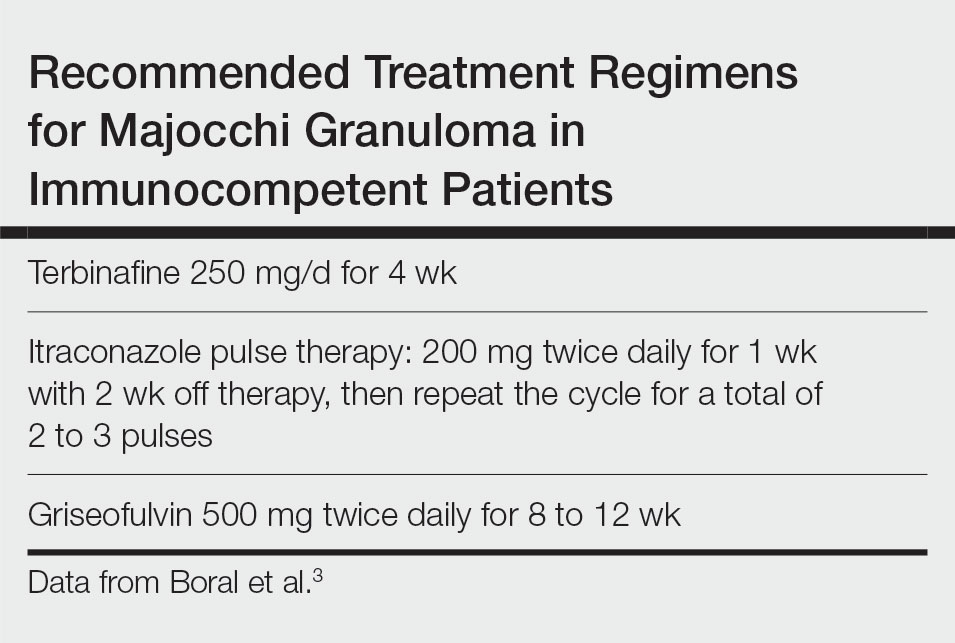

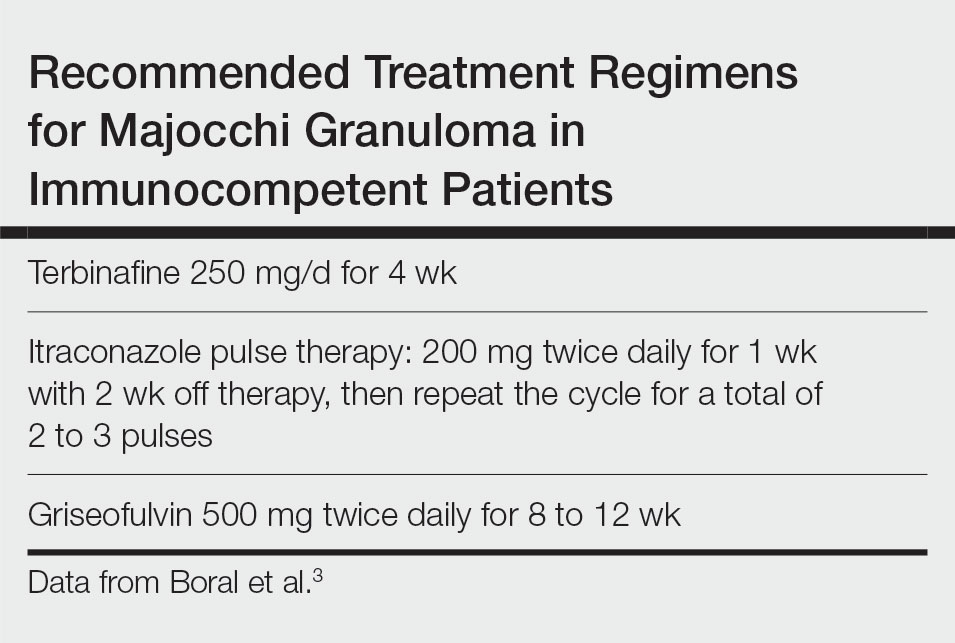

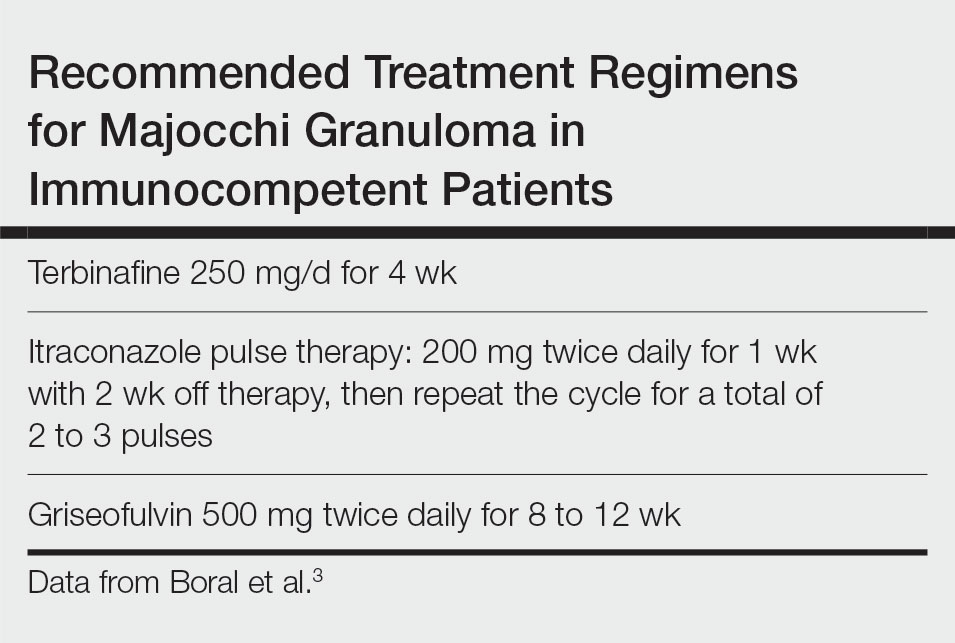

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

The Diagnosis: Majocchi Granuloma

Histopathology showed rare follicular-based organisms highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff staining. This finding along with her use of clobetasol ointment on the hands led to a diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma in our patient. Clobetasol and crisaborole ointments were discontinued, and she was started on oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks, which resulted in resolution of the rash.

Majocchi granuloma (also known as nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis) is a perifollicular granulomatous process caused by a dermatophyte infection of the hair follicles. Trichophyton rubrum is the most commonly implicated organism, followed by Trichophyton mentagrophytes and Epidermophyton floccosum, which also cause tinea corporis and tinea pedis.1 This condition most commonly occurs in women aged 20 to 35 years. Risk factors include trauma, occlusion of the hair follicles, immunosuppression, and use of potent topical corticosteroids in patients with tinea.2,3 Immunocompetent patients present with perifollicular papules or pustules with erythematous scaly plaques on the extremities, while immunocompromised patients may have subcutaneous nodules or abscesses on any hair-bearing parts of the body.3

Majocchi granuloma is considered a dermal fungal infection in which the disruption of hair follicles from occlusion or trauma allows fungal organisms and keratinaceous material substrates to be introduced into the dermis. The differential diagnosis is based on the types of presenting lesions. The papules of Majocchi granuloma can resemble folliculitis, acne, or insect bites, while nodules can resemble erythema nodosum or furunculosis.4 Plaques, such as those seen in our patient, can mimic cellulitis and allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.4 Additionally, the plaques may appear annular or figurate, which may resemble erythema gyratum repens or erythema annulare centrifugum.

The diagnosis of Majocchi granuloma often requires fungal culture and biopsy because a potassium hydroxide preparation is unable to distinguish between superficial and invasive dermatophytes.3 Histopathology will show perifollicular granulomatous inflammation. Fungal elements can be detected with periodic acid–Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the hairs and hair follicles as well as dermal infiltrates.4

Topical corticosteroids should be discontinued. Systemic antifungals are the treatment of choice for Majocchi granuloma, as topical antifungals are not effective against deep fungal infections. Although there are no standard guidelines on duration or dosage, recommended regimens in immunocompetent patients include terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks; itraconazole pulse therapy consisting of 200 mg twice daily for 1 week with 2 weeks off therapy, then repeat the cycle for a total of 2 to 3 pulses; and griseofulvin 500 mg twice daily for 8 to 12 weeks (Table).3 For immunocompromised patients, combination therapy with more than one antifungal may be necessary.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston DM. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts. In: James WD, Berger T, Elston D, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2016:285-318.

- Li FQ, Lv S, Xia JX. Majocchi’s granuloma after topical corticosteroids therapy. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2014;2014:507176.

- Boral H, Durdu M, Ilkit M. Majocchi’s granuloma: current perspectives. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:751-760.

- I˙lkit M, Durdu M, Karakas¸ M. Majocchi’s granuloma: a symptom complex caused by fungal pathogens. Med Mycol. 2012;50:449-457.

A 33-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic rash on the left hand that was suspected by her primary care physician to be a flare of hand dermatitis. The patient had a history of irritant hand dermatitis diagnosed 2 years prior that was suspected to be secondary to frequent handwashing and was well controlled with clobetasol and crisaborole ointments for 1 year. Four months prior to the current presentation, she developed a flare that was refractory to these topical therapies; treatment with biweekly dupilumab 300 mg was initiated by dermatology, but the rash continued to evolve. A punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Injecting long-acting antiretrovirals into clinic care

At the Whitman-Walker Health Center, Washington, community health workers see about 3,200 antiretroviral users a year. With long-acting injections now available, the clinic opted to integrate the new medications into its peer staff program.

“Our peer workers are very competent,” said Rupa Patel, MD, MPH, medical liason of the pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention program at Washington University at St. Louis.* “They do phlebotomy, they give you your meds. They’re your main doctor until you really need to see the doctor.”

In the peer staff program, workers are trained in a 4-month medical residency–style program that shows them how to test for HIV, inject long-acting formulations of new drugs, and conduct follow-up visits.

Presenting the new approach at the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science, Dr. Patel reported that 139 people have received long-acting injections at the clinic since the program launched with a total of 314 injections administered.

The training program includes lectures, mock injection, and client care sessions, observation and supervised administration, a written exam, and case review sessions.

Retention for the second injection was 95%, with 91% of injections given within the 14-day window. For the third injection, retention was 91%, with 63% given within the window.

The program reports a high level of client satisfaction with the peer-administered injections, which are also given in a room decorated with a beach theme and music to help calm people who might be nervous of receiving shots.

“Our retention is going to be the highest compared to other clinics because your peer, your friend, is reminding you and comforting you and telling you: ‘Don’t worry, I’m on the injection too,’ ” Dr. Patel said.

Andrew Grulich, MD, PhD, head of the HIV epidemiology and prevention program at the Kirby Institute, Sydney, pointed out there is tension between wanting to use long-acting injectables for people who are struggling with taking oral therapies daily and the need to ensure that they come back for their injections on time.

“I think it’s a potential way forward – we’re learning as we’re going with these new forms of therapy,” he said in an interview. “It is absolutely critical that people turn up on time for those injections, and if they don’t, resistance can be an issue.”

Presenting new data from another project at the HIV Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital, Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, told the conference: “There are multiple reasons why it’s hard to take oral antiretrovirals every day.”

At the HIV Clinic in San Francisco General, people without homes, those with mental illness, and those using stimulants receive care.

The clinical trials for long-acting injectable antiretrovirals included only people who were virologically suppressed, which is also the Food and Drug Administration criteria for use. However, this clinic offered long-acting injections to patients with viremia because it was too difficult for them to take a daily pill.

In a comment, Dr. Gandhi, director of the University of California, San Francisco’s Center for AIDS Research, said: “We don’t call people hard to reach, we call them hardly reached because it’s not their fault.” There are just all of these issues that have made it harder for them to take medication consistently.

Dr. Gandhi reported that, of the 133 people being treated with long-acting injectable cabotegravir and rilpivirine at the clinic through this program, 57 had viremia at baseline.

However, only two of these patients experienced virologic failure while on the injectable antiretroviral program. The overall virologic failure rate was 1.5%, which was equivalent to that seen in clinical trials in virologically suppressed individuals.

The results presented at the conference and were also published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The clinic found that 73% of people attended their injection appointments on time, and those who did not were followed up with telephone calls to ensure they received their injection within the 14-day window.

Dr. Gandhi said people were highly motivated to turn up for their injection appointments. “They are virologically suppressed, so it feels so amazing. They’re self-motivated for the first time to want to get an injection.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 8/4/23: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Patel's university affiliation.