User login

Applications for laser-assisted drug delivery on the horizon, expert says

For those who view fractional ablative laser–assisted drug delivery as a pie-in-the-sky procedure that will take years to work its way into routine clinical practice, think again.

According to Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, DMSc, .

“The groundwork has been established over a decade with more than 100 publications available on PubMed,” Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, said during a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy. “There is no doubt that by drilling tiny little holes or channels with ablative fractional lasers, we enhance drug delivery to the skin, and we also empower different topical treatment regimens. Also, laser-assisted drug delivery holds the potential to bring new innovations into established medicine.”

Many studies have demonstrated that clinicians can enhance drug uptake into the skin with the fractional 10,600 nm CO2 laser, the fractional 2,940 nm erbium:YAG laser, and the 1,927 nm thulium laser, but proper tuning of the devices is key. The lower the density, the better, Dr. Haedersdal said.

“Typically, we use 5% density or 5% coverage, sometimes 10%-15%, but don’t go higher in order to avoid the risk of having a systemic uptake,” she said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “Also, the pulse energy for channel depth needs to be tailored to the specific dermatologic disease being treated,” she said, noting that for melasma, for example, “very low pulse energies” would be used, but they would be higher for treating thicker lesions, such as a hypertrophic scar.

Treatment with ablative fractional lasers enhances drug accumulation in the skin of any drug or substance applied to the skin, and clinical indications are expanding rapidly. Established indications include combining ablative fractional lasers and photodynamic therapy (PDT) for AKs and combining ablative fractional lasers and triamcinolone or 5-FU for scars. “Although we have a good body of evidence, particularly for AKs, it’s still an off-label use,” she emphasized.

Evolving indications include concomitant use of ablative fractional laser and vitamins and cosmeceuticals for rejuvenation; lidocaine for local anesthetics; tranexamic acid and hydroquinone for melasma; antifungals for onychomycosis; Botox for hyperhidrosis; minoxidil for alopecia; and betamethasone for vitiligo. A promising treatment for skin cancer “on the horizon,” she said, is the “combination of ablative fractional laser with PD1 inhibitors and chemotherapy.”

Data on AKs

Evidence supporting laser-assisted drug delivery for AKs comes from more than 10 randomized, controlled trials in the dermatology literature involving 400-plus immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. These trials have found ablative fractional laser–assisted PDT to be significantly more efficacious than PDT alone up to 12 months postoperatively and to foster lower rates of AK recurrence.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review, German researchers concluded that PDT combined with ablative laser treatment for AKs is more efficient but not more painful than either therapy alone. They recommended the combined regimen for patients with severe photodamage, field cancerization, and multiple AKs.

In 2020, an international consensus panel of experts, including Dr. Haedersdal, published recommendations regarding laser treatment of traumatic scars and contractures. The panel members determined that laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroids and antimetabolites was recommended for hypertrophic scars and cited triamcinolone acetonide suspension (TAC) as the most common corticosteroid used in combination with ablative fractional lasers. “It can be applied in concentrations of 40 mg/mL or less depending on the degree of hypertrophy,” they wrote.

In addition, they stated that 5-FU solution is “most commonly applied in a concentration of 50 mg/mL alone, or mixed with TAC in ratios of 9:1 or 3:1.”

According to the best available evidence, the clinical approach for hypertrophic scars supports combination treatment with ablative fractional laser and triamcinolone acetonide either alone or in combination with 5-FU. For atrophic scars, laser-assisted delivery of poly-L-lactic acid has been shown to be efficient. “Both of these treatments improve texture and thickness but also dyschromia and scar functionality,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is also a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Boston.

Commenting on patient safety with laser-assisted drug delivery, “the combination of lasers and topicals can be a powerful cocktail,” she said. “You can expect intensified local skin reactions. When treating larger areas, consider the risk of systemic absorption and the risk of potential toxicity. There is also the potential for infection with pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus. The take-home message here is that you should only use the type and amount of drug no higher than administered during intradermal injection.”

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received equipment from Cherry Imaging, Cynosure-Hologic, MiraDry, and PerfAction Technologies. She has also received research grants from Leo Pharma, Lutronic, Mirai Medical, Novoxel, and Venus Concept.

For those who view fractional ablative laser–assisted drug delivery as a pie-in-the-sky procedure that will take years to work its way into routine clinical practice, think again.

According to Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, DMSc, .

“The groundwork has been established over a decade with more than 100 publications available on PubMed,” Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, said during a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy. “There is no doubt that by drilling tiny little holes or channels with ablative fractional lasers, we enhance drug delivery to the skin, and we also empower different topical treatment regimens. Also, laser-assisted drug delivery holds the potential to bring new innovations into established medicine.”

Many studies have demonstrated that clinicians can enhance drug uptake into the skin with the fractional 10,600 nm CO2 laser, the fractional 2,940 nm erbium:YAG laser, and the 1,927 nm thulium laser, but proper tuning of the devices is key. The lower the density, the better, Dr. Haedersdal said.

“Typically, we use 5% density or 5% coverage, sometimes 10%-15%, but don’t go higher in order to avoid the risk of having a systemic uptake,” she said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “Also, the pulse energy for channel depth needs to be tailored to the specific dermatologic disease being treated,” she said, noting that for melasma, for example, “very low pulse energies” would be used, but they would be higher for treating thicker lesions, such as a hypertrophic scar.

Treatment with ablative fractional lasers enhances drug accumulation in the skin of any drug or substance applied to the skin, and clinical indications are expanding rapidly. Established indications include combining ablative fractional lasers and photodynamic therapy (PDT) for AKs and combining ablative fractional lasers and triamcinolone or 5-FU for scars. “Although we have a good body of evidence, particularly for AKs, it’s still an off-label use,” she emphasized.

Evolving indications include concomitant use of ablative fractional laser and vitamins and cosmeceuticals for rejuvenation; lidocaine for local anesthetics; tranexamic acid and hydroquinone for melasma; antifungals for onychomycosis; Botox for hyperhidrosis; minoxidil for alopecia; and betamethasone for vitiligo. A promising treatment for skin cancer “on the horizon,” she said, is the “combination of ablative fractional laser with PD1 inhibitors and chemotherapy.”

Data on AKs

Evidence supporting laser-assisted drug delivery for AKs comes from more than 10 randomized, controlled trials in the dermatology literature involving 400-plus immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. These trials have found ablative fractional laser–assisted PDT to be significantly more efficacious than PDT alone up to 12 months postoperatively and to foster lower rates of AK recurrence.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review, German researchers concluded that PDT combined with ablative laser treatment for AKs is more efficient but not more painful than either therapy alone. They recommended the combined regimen for patients with severe photodamage, field cancerization, and multiple AKs.

In 2020, an international consensus panel of experts, including Dr. Haedersdal, published recommendations regarding laser treatment of traumatic scars and contractures. The panel members determined that laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroids and antimetabolites was recommended for hypertrophic scars and cited triamcinolone acetonide suspension (TAC) as the most common corticosteroid used in combination with ablative fractional lasers. “It can be applied in concentrations of 40 mg/mL or less depending on the degree of hypertrophy,” they wrote.

In addition, they stated that 5-FU solution is “most commonly applied in a concentration of 50 mg/mL alone, or mixed with TAC in ratios of 9:1 or 3:1.”

According to the best available evidence, the clinical approach for hypertrophic scars supports combination treatment with ablative fractional laser and triamcinolone acetonide either alone or in combination with 5-FU. For atrophic scars, laser-assisted delivery of poly-L-lactic acid has been shown to be efficient. “Both of these treatments improve texture and thickness but also dyschromia and scar functionality,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is also a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Boston.

Commenting on patient safety with laser-assisted drug delivery, “the combination of lasers and topicals can be a powerful cocktail,” she said. “You can expect intensified local skin reactions. When treating larger areas, consider the risk of systemic absorption and the risk of potential toxicity. There is also the potential for infection with pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus. The take-home message here is that you should only use the type and amount of drug no higher than administered during intradermal injection.”

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received equipment from Cherry Imaging, Cynosure-Hologic, MiraDry, and PerfAction Technologies. She has also received research grants from Leo Pharma, Lutronic, Mirai Medical, Novoxel, and Venus Concept.

For those who view fractional ablative laser–assisted drug delivery as a pie-in-the-sky procedure that will take years to work its way into routine clinical practice, think again.

According to Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, DMSc, .

“The groundwork has been established over a decade with more than 100 publications available on PubMed,” Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, said during a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy. “There is no doubt that by drilling tiny little holes or channels with ablative fractional lasers, we enhance drug delivery to the skin, and we also empower different topical treatment regimens. Also, laser-assisted drug delivery holds the potential to bring new innovations into established medicine.”

Many studies have demonstrated that clinicians can enhance drug uptake into the skin with the fractional 10,600 nm CO2 laser, the fractional 2,940 nm erbium:YAG laser, and the 1,927 nm thulium laser, but proper tuning of the devices is key. The lower the density, the better, Dr. Haedersdal said.

“Typically, we use 5% density or 5% coverage, sometimes 10%-15%, but don’t go higher in order to avoid the risk of having a systemic uptake,” she said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “Also, the pulse energy for channel depth needs to be tailored to the specific dermatologic disease being treated,” she said, noting that for melasma, for example, “very low pulse energies” would be used, but they would be higher for treating thicker lesions, such as a hypertrophic scar.

Treatment with ablative fractional lasers enhances drug accumulation in the skin of any drug or substance applied to the skin, and clinical indications are expanding rapidly. Established indications include combining ablative fractional lasers and photodynamic therapy (PDT) for AKs and combining ablative fractional lasers and triamcinolone or 5-FU for scars. “Although we have a good body of evidence, particularly for AKs, it’s still an off-label use,” she emphasized.

Evolving indications include concomitant use of ablative fractional laser and vitamins and cosmeceuticals for rejuvenation; lidocaine for local anesthetics; tranexamic acid and hydroquinone for melasma; antifungals for onychomycosis; Botox for hyperhidrosis; minoxidil for alopecia; and betamethasone for vitiligo. A promising treatment for skin cancer “on the horizon,” she said, is the “combination of ablative fractional laser with PD1 inhibitors and chemotherapy.”

Data on AKs

Evidence supporting laser-assisted drug delivery for AKs comes from more than 10 randomized, controlled trials in the dermatology literature involving 400-plus immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. These trials have found ablative fractional laser–assisted PDT to be significantly more efficacious than PDT alone up to 12 months postoperatively and to foster lower rates of AK recurrence.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review, German researchers concluded that PDT combined with ablative laser treatment for AKs is more efficient but not more painful than either therapy alone. They recommended the combined regimen for patients with severe photodamage, field cancerization, and multiple AKs.

In 2020, an international consensus panel of experts, including Dr. Haedersdal, published recommendations regarding laser treatment of traumatic scars and contractures. The panel members determined that laser-assisted delivery of corticosteroids and antimetabolites was recommended for hypertrophic scars and cited triamcinolone acetonide suspension (TAC) as the most common corticosteroid used in combination with ablative fractional lasers. “It can be applied in concentrations of 40 mg/mL or less depending on the degree of hypertrophy,” they wrote.

In addition, they stated that 5-FU solution is “most commonly applied in a concentration of 50 mg/mL alone, or mixed with TAC in ratios of 9:1 or 3:1.”

According to the best available evidence, the clinical approach for hypertrophic scars supports combination treatment with ablative fractional laser and triamcinolone acetonide either alone or in combination with 5-FU. For atrophic scars, laser-assisted delivery of poly-L-lactic acid has been shown to be efficient. “Both of these treatments improve texture and thickness but also dyschromia and scar functionality,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is also a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Boston.

Commenting on patient safety with laser-assisted drug delivery, “the combination of lasers and topicals can be a powerful cocktail,” she said. “You can expect intensified local skin reactions. When treating larger areas, consider the risk of systemic absorption and the risk of potential toxicity. There is also the potential for infection with pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus. The take-home message here is that you should only use the type and amount of drug no higher than administered during intradermal injection.”

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received equipment from Cherry Imaging, Cynosure-Hologic, MiraDry, and PerfAction Technologies. She has also received research grants from Leo Pharma, Lutronic, Mirai Medical, Novoxel, and Venus Concept.

FROM A LASER & AESTHETIC SKIN THERAPY COURSE

Fungi that cause lung infections now found in most states: Study

Soil-dwelling fungi that can cause lung infections are more widespread than most doctors thought, sometimes leading to missed diagnoses, according to a new study.

Researchers studying fungi-linked lung infections realized that many infections were occurring in places the fungi weren’t thought to exist. They found that maps doctors use to know if the fungi are a threat in their area hadn’t been updated in half a century.

University of California, Davis infectious disease professor George Thompson, MD, said in a commentary published along with the study.

Published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, the study sought to identify illnesses linked to three types of soil fungi in the United States that are known to cause lung infections. They are called histoplasma, blastomyces, and coccidioides, the latter of which causes an illness known as Valley fever, which has been on the rise in California.

Researchers used data for more than 45 million people who use Medicare and found that at least 1 of these 3 fungi are present in 48 of 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.

Symptoms after breathing in the fungi spores include fever and cough and can be similar to symptoms of other illnesses, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The researchers said health care providers need to increase their suspicion for these fungi, which “would likely result in fewer missed diagnoses, fewer diagnostic delays, and improved patient outcomes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Soil-dwelling fungi that can cause lung infections are more widespread than most doctors thought, sometimes leading to missed diagnoses, according to a new study.

Researchers studying fungi-linked lung infections realized that many infections were occurring in places the fungi weren’t thought to exist. They found that maps doctors use to know if the fungi are a threat in their area hadn’t been updated in half a century.

University of California, Davis infectious disease professor George Thompson, MD, said in a commentary published along with the study.

Published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, the study sought to identify illnesses linked to three types of soil fungi in the United States that are known to cause lung infections. They are called histoplasma, blastomyces, and coccidioides, the latter of which causes an illness known as Valley fever, which has been on the rise in California.

Researchers used data for more than 45 million people who use Medicare and found that at least 1 of these 3 fungi are present in 48 of 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.

Symptoms after breathing in the fungi spores include fever and cough and can be similar to symptoms of other illnesses, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The researchers said health care providers need to increase their suspicion for these fungi, which “would likely result in fewer missed diagnoses, fewer diagnostic delays, and improved patient outcomes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Soil-dwelling fungi that can cause lung infections are more widespread than most doctors thought, sometimes leading to missed diagnoses, according to a new study.

Researchers studying fungi-linked lung infections realized that many infections were occurring in places the fungi weren’t thought to exist. They found that maps doctors use to know if the fungi are a threat in their area hadn’t been updated in half a century.

University of California, Davis infectious disease professor George Thompson, MD, said in a commentary published along with the study.

Published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, the study sought to identify illnesses linked to three types of soil fungi in the United States that are known to cause lung infections. They are called histoplasma, blastomyces, and coccidioides, the latter of which causes an illness known as Valley fever, which has been on the rise in California.

Researchers used data for more than 45 million people who use Medicare and found that at least 1 of these 3 fungi are present in 48 of 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.

Symptoms after breathing in the fungi spores include fever and cough and can be similar to symptoms of other illnesses, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The researchers said health care providers need to increase their suspicion for these fungi, which “would likely result in fewer missed diagnoses, fewer diagnostic delays, and improved patient outcomes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Ohio measles outbreak sickens nearly 60 children

None of the children had been fully vaccinated against measles, and 23 of them have been hospitalized, local officials report.

“Measles can be very serious, especially for children under age 5,” Columbus Public Health spokesperson Kelli Newman told CNN.

Nearly all of the infected children are under age 5, with 12 of them being under 1 year old.

“Many children are hospitalized for dehydration,” Ms. Newman told CNN in an email. “Other serious complications also can include pneumonia and neurological conditions such as encephalitis. There’s no way of knowing which children will become so sick they have to be hospitalized. The safest way to protect children from measles is to make sure they are vaccinated with MMR.”

Of the 59 infected children, 56 were unvaccinated and three had been partially vaccinated. The MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine is recommended for children beginning at 12 months old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and American Academy of Pediatrics. Two doses are needed to be considered fully vaccinated, and the second dose is usually given between 4 and 6 years old.

Measles “is one of the most infectious agents known to man,” the academy says.

It is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 9 out of 10 people around that person will also become infected if they are not protected, the CDC explains. Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, or death.

Last month, the World Health Organization and CDC warned that 40 million children worldwide missed their measles vaccinations in 2021, partly due to pandemic disruptions. The American Academy of Pediatrics also notes that many parents choose not to vaccinate their children due to misinformation.

Infants are at heightened risk because they are too young to be vaccinated.

The academy offered several tips for protecting unvaccinated infants during a measles outbreak:

- Limit your baby’s exposure to crowds, other children, and people with cold symptoms.

- Disinfect objects and surfaces at home regularly, because the measles virus can live on surfaces or suspended in the air for 2 hours.

- If possible, feed your baby breast milk, because it has antibodies to prevent and fight infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

None of the children had been fully vaccinated against measles, and 23 of them have been hospitalized, local officials report.

“Measles can be very serious, especially for children under age 5,” Columbus Public Health spokesperson Kelli Newman told CNN.

Nearly all of the infected children are under age 5, with 12 of them being under 1 year old.

“Many children are hospitalized for dehydration,” Ms. Newman told CNN in an email. “Other serious complications also can include pneumonia and neurological conditions such as encephalitis. There’s no way of knowing which children will become so sick they have to be hospitalized. The safest way to protect children from measles is to make sure they are vaccinated with MMR.”

Of the 59 infected children, 56 were unvaccinated and three had been partially vaccinated. The MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine is recommended for children beginning at 12 months old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and American Academy of Pediatrics. Two doses are needed to be considered fully vaccinated, and the second dose is usually given between 4 and 6 years old.

Measles “is one of the most infectious agents known to man,” the academy says.

It is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 9 out of 10 people around that person will also become infected if they are not protected, the CDC explains. Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, or death.

Last month, the World Health Organization and CDC warned that 40 million children worldwide missed their measles vaccinations in 2021, partly due to pandemic disruptions. The American Academy of Pediatrics also notes that many parents choose not to vaccinate their children due to misinformation.

Infants are at heightened risk because they are too young to be vaccinated.

The academy offered several tips for protecting unvaccinated infants during a measles outbreak:

- Limit your baby’s exposure to crowds, other children, and people with cold symptoms.

- Disinfect objects and surfaces at home regularly, because the measles virus can live on surfaces or suspended in the air for 2 hours.

- If possible, feed your baby breast milk, because it has antibodies to prevent and fight infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

None of the children had been fully vaccinated against measles, and 23 of them have been hospitalized, local officials report.

“Measles can be very serious, especially for children under age 5,” Columbus Public Health spokesperson Kelli Newman told CNN.

Nearly all of the infected children are under age 5, with 12 of them being under 1 year old.

“Many children are hospitalized for dehydration,” Ms. Newman told CNN in an email. “Other serious complications also can include pneumonia and neurological conditions such as encephalitis. There’s no way of knowing which children will become so sick they have to be hospitalized. The safest way to protect children from measles is to make sure they are vaccinated with MMR.”

Of the 59 infected children, 56 were unvaccinated and three had been partially vaccinated. The MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine is recommended for children beginning at 12 months old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and American Academy of Pediatrics. Two doses are needed to be considered fully vaccinated, and the second dose is usually given between 4 and 6 years old.

Measles “is one of the most infectious agents known to man,” the academy says.

It is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 9 out of 10 people around that person will also become infected if they are not protected, the CDC explains. Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, or death.

Last month, the World Health Organization and CDC warned that 40 million children worldwide missed their measles vaccinations in 2021, partly due to pandemic disruptions. The American Academy of Pediatrics also notes that many parents choose not to vaccinate their children due to misinformation.

Infants are at heightened risk because they are too young to be vaccinated.

The academy offered several tips for protecting unvaccinated infants during a measles outbreak:

- Limit your baby’s exposure to crowds, other children, and people with cold symptoms.

- Disinfect objects and surfaces at home regularly, because the measles virus can live on surfaces or suspended in the air for 2 hours.

- If possible, feed your baby breast milk, because it has antibodies to prevent and fight infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A 9-year old female presented with 1 day of fever, fatigue, and sore throat

This condition typically presents in the setting of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis, or strep throat, and is spread via mucosal transfer in close proximity such as classrooms and nurseries. The dermatologic symptoms are a result of the endotoxin produced by S. pyogenes, which is part of the group A Strep bacteria. Clinically, the presentation can be differentiated from an allergic eruption by its relation to acute pharyngitis, insidious onset, and lack of confluence of the lesions. Diagnosis is supported by a throat culture and rapid strep test, although a rapid test lacks reliability in older patients who are less commonly affected and likely to be carriers. First-line treatment is penicillin or amoxicillin, but first-generation cephalosporins, clindamycin, or erythromycin are sufficient if the patient is allergic to penicillins. Prognosis worsens as time between onset and treatment increases, but is overall excellent now with the introduction of antibiotics and improved hygiene.

Scarlet fever is among a list of many common childhood rashes, and it can be difficult to differentiate between these pathologies on clinical presentation. A few notable childhood dermatologic eruptions include erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), roseola (exanthema subitum or sixth disease), and measles. These cases can be distinguished clinically by the age of the patient, distribution, and quality of the symptoms. Laboratory testing may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Erythema infectiosum is known as fifth disease or slapped-cheek rash because it commonly presents on the cheeks as a pink, maculopapular rash in a reticular pattern. The disease is caused by parvovirus B19 and is accompanied by low fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, and nausea, which precedes the erythematous rash. The facial rash appears first and is followed by patchy eruptions on the extremities. Appearance of the rash typically indicates the patient is no longer contagious, and patients are treated symptomatically with NSAIDs and antihistamines for associated pruritus.

Roseola infantum is commonly caused by human herpesvirus 6 and is usually found in children 3 years and younger. The defining symptom is a high fever, which is paired with a mild cough, runny nose, and diarrhea. A maculopapular rash appears after the fever subsides, starting centrally and spreading outward to the extremities. Although this rash is similar to measles, they can be differentiated by the order of onset. The rash caused by measles begins on the face and mouth (Koplik spots) and moves downward. Additionally, the patient appears generally healthy and the disease is self-limiting in roseola, while patients with measles will appear more ill and require further attention. Measles is caused by the measles virus of the genus Morbillivirus and is highly contagious. It is spread via respiratory route presenting with fever, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis followed by the rash. Fortunately, the measles vaccine is in widespread use, so cases have declined over the years.

Our patient had a positive strep test. Influenza and coronavirus tests were negative. She was started on daily amoxicillin and the rash resolved within 2 days of taking the antibiotics.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University, Tampa, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Allmon A et al.. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Aug 1;92(3):211-6.

Moss WJ. Lancet. 2017 Dec 2;390(10111):2490-502.

Mullins TB and Krishnamurthy K. Roseola Infantum, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Islan, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

Pardo S and Perera TB. Scarlet Fever, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

This condition typically presents in the setting of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis, or strep throat, and is spread via mucosal transfer in close proximity such as classrooms and nurseries. The dermatologic symptoms are a result of the endotoxin produced by S. pyogenes, which is part of the group A Strep bacteria. Clinically, the presentation can be differentiated from an allergic eruption by its relation to acute pharyngitis, insidious onset, and lack of confluence of the lesions. Diagnosis is supported by a throat culture and rapid strep test, although a rapid test lacks reliability in older patients who are less commonly affected and likely to be carriers. First-line treatment is penicillin or amoxicillin, but first-generation cephalosporins, clindamycin, or erythromycin are sufficient if the patient is allergic to penicillins. Prognosis worsens as time between onset and treatment increases, but is overall excellent now with the introduction of antibiotics and improved hygiene.

Scarlet fever is among a list of many common childhood rashes, and it can be difficult to differentiate between these pathologies on clinical presentation. A few notable childhood dermatologic eruptions include erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), roseola (exanthema subitum or sixth disease), and measles. These cases can be distinguished clinically by the age of the patient, distribution, and quality of the symptoms. Laboratory testing may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Erythema infectiosum is known as fifth disease or slapped-cheek rash because it commonly presents on the cheeks as a pink, maculopapular rash in a reticular pattern. The disease is caused by parvovirus B19 and is accompanied by low fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, and nausea, which precedes the erythematous rash. The facial rash appears first and is followed by patchy eruptions on the extremities. Appearance of the rash typically indicates the patient is no longer contagious, and patients are treated symptomatically with NSAIDs and antihistamines for associated pruritus.

Roseola infantum is commonly caused by human herpesvirus 6 and is usually found in children 3 years and younger. The defining symptom is a high fever, which is paired with a mild cough, runny nose, and diarrhea. A maculopapular rash appears after the fever subsides, starting centrally and spreading outward to the extremities. Although this rash is similar to measles, they can be differentiated by the order of onset. The rash caused by measles begins on the face and mouth (Koplik spots) and moves downward. Additionally, the patient appears generally healthy and the disease is self-limiting in roseola, while patients with measles will appear more ill and require further attention. Measles is caused by the measles virus of the genus Morbillivirus and is highly contagious. It is spread via respiratory route presenting with fever, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis followed by the rash. Fortunately, the measles vaccine is in widespread use, so cases have declined over the years.

Our patient had a positive strep test. Influenza and coronavirus tests were negative. She was started on daily amoxicillin and the rash resolved within 2 days of taking the antibiotics.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University, Tampa, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Allmon A et al.. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Aug 1;92(3):211-6.

Moss WJ. Lancet. 2017 Dec 2;390(10111):2490-502.

Mullins TB and Krishnamurthy K. Roseola Infantum, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Islan, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

Pardo S and Perera TB. Scarlet Fever, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

This condition typically presents in the setting of Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis, or strep throat, and is spread via mucosal transfer in close proximity such as classrooms and nurseries. The dermatologic symptoms are a result of the endotoxin produced by S. pyogenes, which is part of the group A Strep bacteria. Clinically, the presentation can be differentiated from an allergic eruption by its relation to acute pharyngitis, insidious onset, and lack of confluence of the lesions. Diagnosis is supported by a throat culture and rapid strep test, although a rapid test lacks reliability in older patients who are less commonly affected and likely to be carriers. First-line treatment is penicillin or amoxicillin, but first-generation cephalosporins, clindamycin, or erythromycin are sufficient if the patient is allergic to penicillins. Prognosis worsens as time between onset and treatment increases, but is overall excellent now with the introduction of antibiotics and improved hygiene.

Scarlet fever is among a list of many common childhood rashes, and it can be difficult to differentiate between these pathologies on clinical presentation. A few notable childhood dermatologic eruptions include erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), roseola (exanthema subitum or sixth disease), and measles. These cases can be distinguished clinically by the age of the patient, distribution, and quality of the symptoms. Laboratory testing may be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Erythema infectiosum is known as fifth disease or slapped-cheek rash because it commonly presents on the cheeks as a pink, maculopapular rash in a reticular pattern. The disease is caused by parvovirus B19 and is accompanied by low fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, and nausea, which precedes the erythematous rash. The facial rash appears first and is followed by patchy eruptions on the extremities. Appearance of the rash typically indicates the patient is no longer contagious, and patients are treated symptomatically with NSAIDs and antihistamines for associated pruritus.

Roseola infantum is commonly caused by human herpesvirus 6 and is usually found in children 3 years and younger. The defining symptom is a high fever, which is paired with a mild cough, runny nose, and diarrhea. A maculopapular rash appears after the fever subsides, starting centrally and spreading outward to the extremities. Although this rash is similar to measles, they can be differentiated by the order of onset. The rash caused by measles begins on the face and mouth (Koplik spots) and moves downward. Additionally, the patient appears generally healthy and the disease is self-limiting in roseola, while patients with measles will appear more ill and require further attention. Measles is caused by the measles virus of the genus Morbillivirus and is highly contagious. It is spread via respiratory route presenting with fever, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis followed by the rash. Fortunately, the measles vaccine is in widespread use, so cases have declined over the years.

Our patient had a positive strep test. Influenza and coronavirus tests were negative. She was started on daily amoxicillin and the rash resolved within 2 days of taking the antibiotics.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University, Tampa, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Allmon A et al.. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Aug 1;92(3):211-6.

Moss WJ. Lancet. 2017 Dec 2;390(10111):2490-502.

Mullins TB and Krishnamurthy K. Roseola Infantum, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Islan, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

Pardo S and Perera TB. Scarlet Fever, in “StatPearls.” Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

Erythrasma

THE COMPARISON

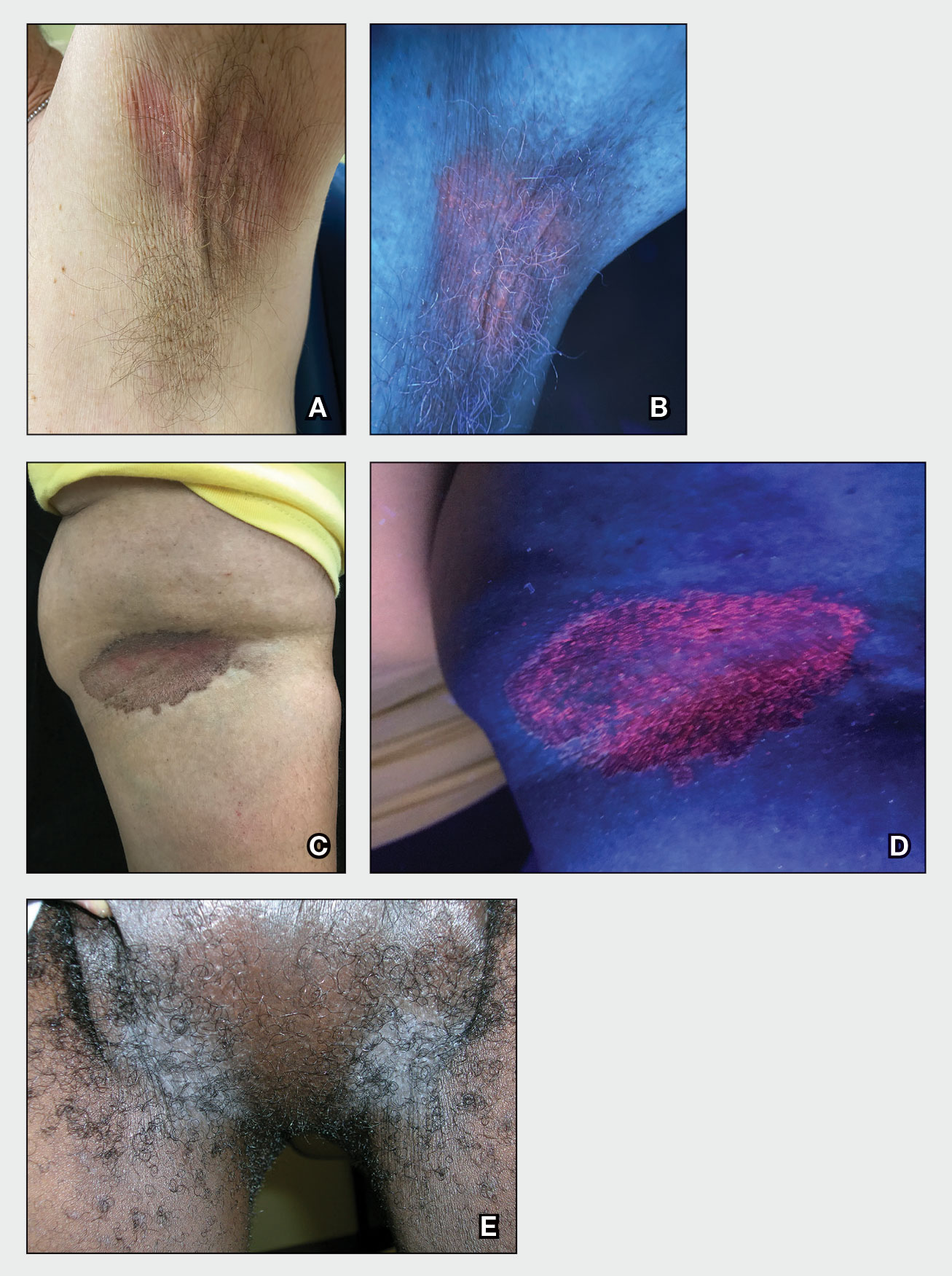

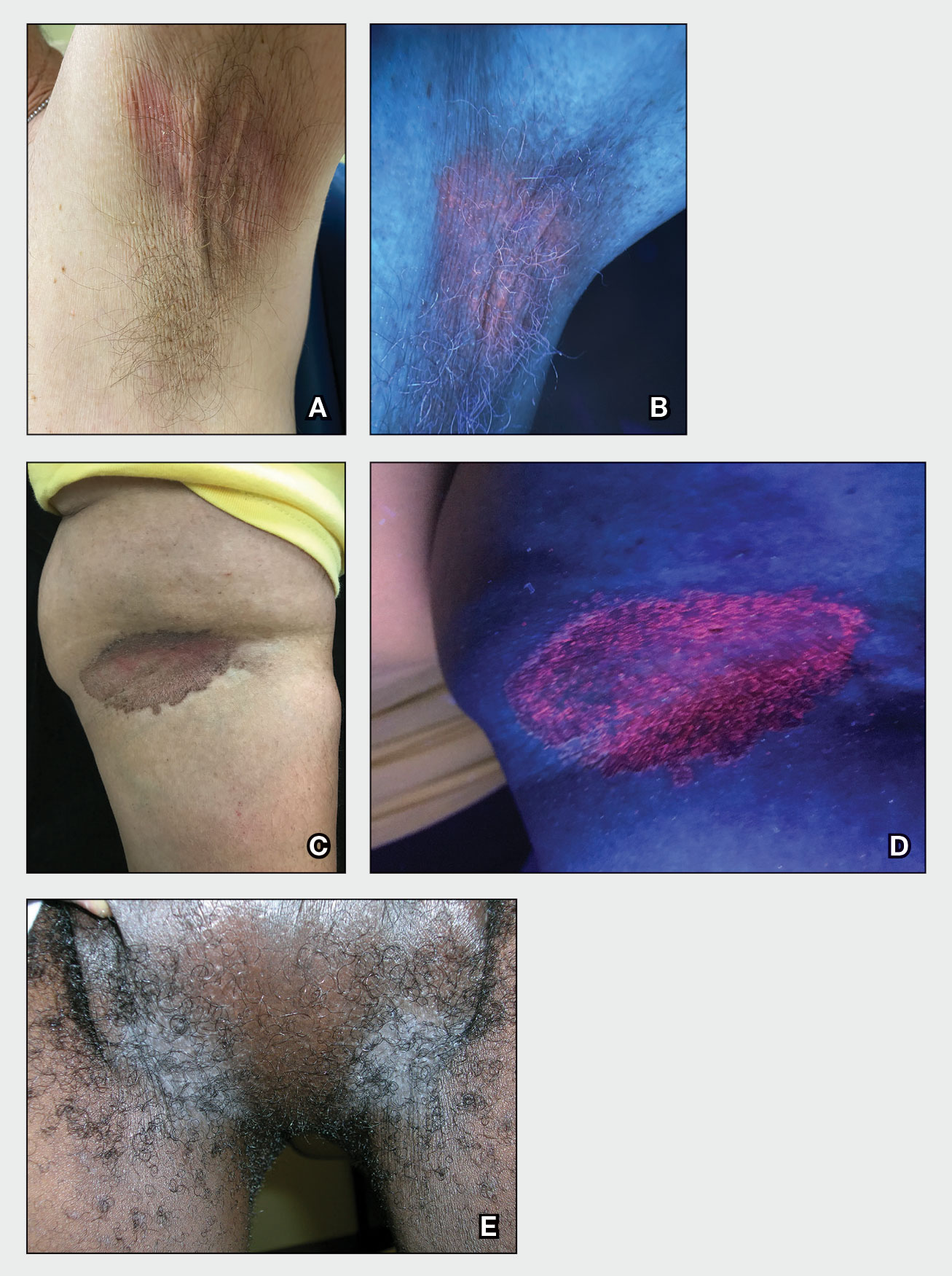

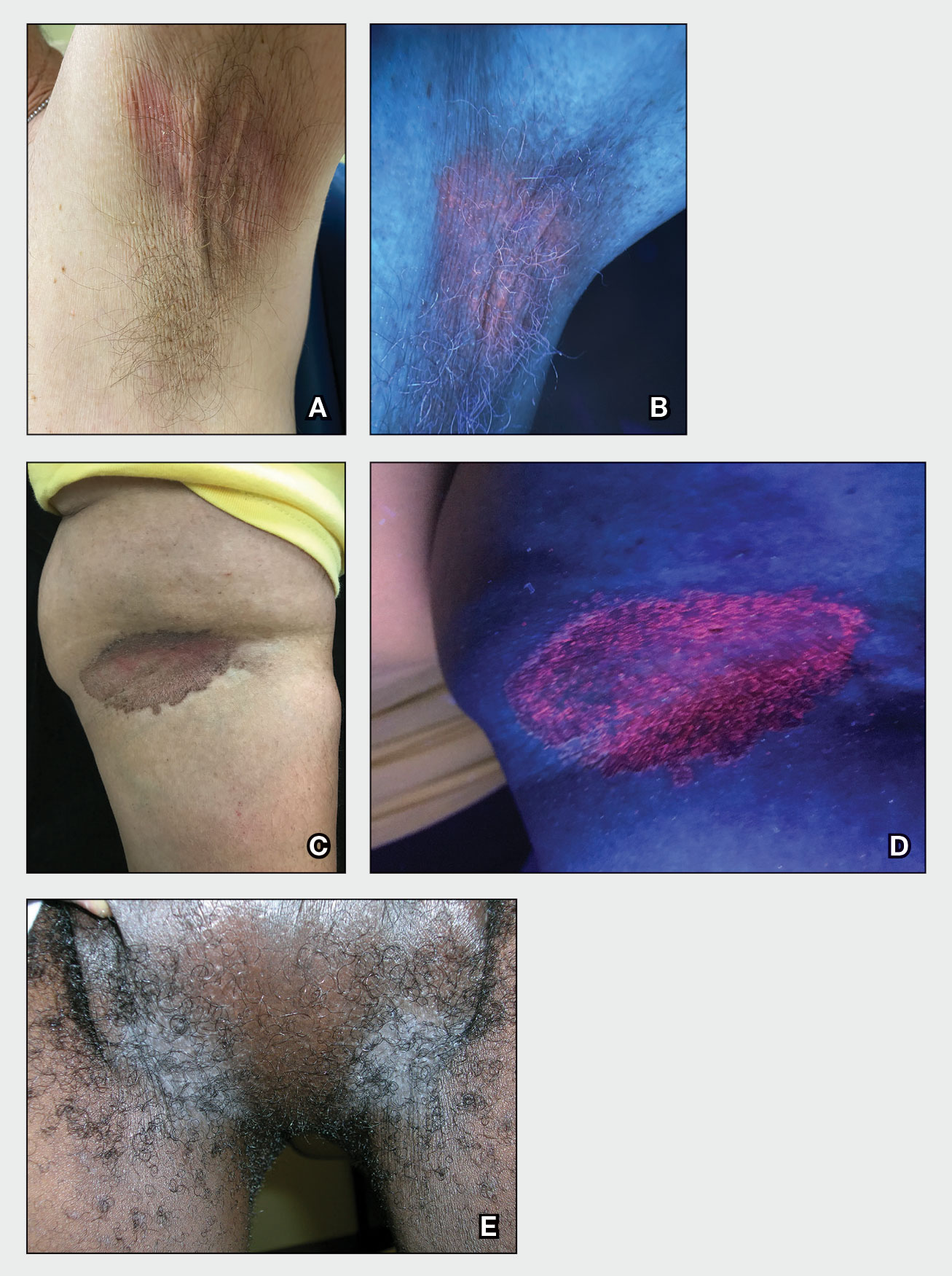

A and B Axilla of a 65-year-old White man with erythrasma showing a well-demarcated erythematous plaque with fine scale (A). Wood lamp examination of the area showed characteristic bright coral red fluorescence (B).

C and D A well-demarcated, red-brown plaque with fine scale in the antecubital fossa of an obese Hispanic woman (C). Wood lamp examination revealed bright coral red fluorescence (D).

E Hypopigmented patches in the groin with pruritus in a Black man. He also had erythrasma between the toes.

Erythrasma is a skin condition caused by acute or chronic infection of the outermost layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum) with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It has a predilection for intertriginous regions such as the axillae, groin, and interdigital spaces of the toes. It can be associated with pruritus or can be asymptomatic.

Epidemiology

Erythrasma typically affects adults, with greater prevalence among those residing in shared living facilities, such as dormitories or nursing homes, or in humid climates.1 It is a common disorder with an estimated prevalence of 17.6% of bacterial skin infections in elderly patients and 44% of diabetic interdigital toe space infections.2,3

Key clinical features

Erythrasma can manifest as red-brown hyperpigmented plaques with fine scale and little central clearing (Figures A and C) or as a hypopigmented patch (Figure E) with a sharply marginated, hyperpigmented border in patients with skin of color. In the interdigital toe spaces, the skin often is white and macerated. These findings may appear in patients of all skin tones.

Worth noting

• Corynebacterium minutissimum produces coproporphyrin III, which glows fluorescent red under Wood lamp examination (Figures B and D). A recent shower or bath may remove the fluorescent coproporphyrins and cause a false-negative result. The interdigital space between the fourth and fifth toes is a common location for C minutissimum; thus clinicians should consider examining these areas with a Wood lamp.

• Associated risk factors include obesity, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and excessive sweating.1

• The differential diagnosis includes intertrigo, inverse psoriasis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome), acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea pedis when present in the interdigital toe spaces. Plaques occurring in circular patterns may be mistaken for tinea corporis or pityriasis rotunda.

• There is a high prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis, and it may exacerbate psoriatic plaques.4

• Treatment options include application of topical clindamycin or erythromycin to the affected area.1 Some patients have responded to topical mupiricin.2 For larger areas, a 1-g dose of clarithromycin5 or a 14-day course of erythromycin may be appropriate.1 Avoid prescribing clarithromycin to patients with preexisting heart disease due to its increased risk for cardiac events or death; consider other agents.

Health disparity highlight

Obesity, most prevalent in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%) and Hispanic adults (45.6%) followed by non- Hispanic White adults (41.4%),6 may cause velvety dark plaques on the neck called acanthosis nigricans. However, acute or chronic erythrasma also may cause hyperpigmentation of the body folds. Although the pathology of erythrasma is due to bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the stratum corneum, acanthosis nigricans is due to fibroblast proliferation and stimulation of epidermal keratinocytes likely from increased growth factors and insulinlike growth factor.7 If erythrasma is mistaken for acanthosis nigricans, the patient may be counseled inappropriately that the hyperpigmentation is something not easily resolved and subsequently left with an active treatable condition that adversely affects their quality of life.

- Groves JB, Nassereddin A, Freeman AM. Erythrasma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; August 11, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513352/

- Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment [published online September 30, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E10733. doi:10.7759/cureus.10733

- Polat M, I˙lhan MN. Dermatological complaints of the elderly attending a dermatology outpatient clinic in Turkey: a prospective study over a one-year period. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:277-281.

- Janeczek M, Kozel Z, Bhasin R, et al. High prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:12-14.

- Khan MJ. Interdigital pedal erythrasma treated with one-time dose of oral clarithromycin 1 g: two case reports [published online February 6, 2020]. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:672-674. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2712

- Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll M, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports. Published June 14, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273

- Brady MF, Rawla P. Acanthosis nigricans. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated October 9, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431057

THE COMPARISON

A and B Axilla of a 65-year-old White man with erythrasma showing a well-demarcated erythematous plaque with fine scale (A). Wood lamp examination of the area showed characteristic bright coral red fluorescence (B).

C and D A well-demarcated, red-brown plaque with fine scale in the antecubital fossa of an obese Hispanic woman (C). Wood lamp examination revealed bright coral red fluorescence (D).

E Hypopigmented patches in the groin with pruritus in a Black man. He also had erythrasma between the toes.

Erythrasma is a skin condition caused by acute or chronic infection of the outermost layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum) with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It has a predilection for intertriginous regions such as the axillae, groin, and interdigital spaces of the toes. It can be associated with pruritus or can be asymptomatic.

Epidemiology

Erythrasma typically affects adults, with greater prevalence among those residing in shared living facilities, such as dormitories or nursing homes, or in humid climates.1 It is a common disorder with an estimated prevalence of 17.6% of bacterial skin infections in elderly patients and 44% of diabetic interdigital toe space infections.2,3

Key clinical features

Erythrasma can manifest as red-brown hyperpigmented plaques with fine scale and little central clearing (Figures A and C) or as a hypopigmented patch (Figure E) with a sharply marginated, hyperpigmented border in patients with skin of color. In the interdigital toe spaces, the skin often is white and macerated. These findings may appear in patients of all skin tones.

Worth noting

• Corynebacterium minutissimum produces coproporphyrin III, which glows fluorescent red under Wood lamp examination (Figures B and D). A recent shower or bath may remove the fluorescent coproporphyrins and cause a false-negative result. The interdigital space between the fourth and fifth toes is a common location for C minutissimum; thus clinicians should consider examining these areas with a Wood lamp.

• Associated risk factors include obesity, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and excessive sweating.1

• The differential diagnosis includes intertrigo, inverse psoriasis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome), acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea pedis when present in the interdigital toe spaces. Plaques occurring in circular patterns may be mistaken for tinea corporis or pityriasis rotunda.

• There is a high prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis, and it may exacerbate psoriatic plaques.4

• Treatment options include application of topical clindamycin or erythromycin to the affected area.1 Some patients have responded to topical mupiricin.2 For larger areas, a 1-g dose of clarithromycin5 or a 14-day course of erythromycin may be appropriate.1 Avoid prescribing clarithromycin to patients with preexisting heart disease due to its increased risk for cardiac events or death; consider other agents.

Health disparity highlight

Obesity, most prevalent in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%) and Hispanic adults (45.6%) followed by non- Hispanic White adults (41.4%),6 may cause velvety dark plaques on the neck called acanthosis nigricans. However, acute or chronic erythrasma also may cause hyperpigmentation of the body folds. Although the pathology of erythrasma is due to bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the stratum corneum, acanthosis nigricans is due to fibroblast proliferation and stimulation of epidermal keratinocytes likely from increased growth factors and insulinlike growth factor.7 If erythrasma is mistaken for acanthosis nigricans, the patient may be counseled inappropriately that the hyperpigmentation is something not easily resolved and subsequently left with an active treatable condition that adversely affects their quality of life.

THE COMPARISON

A and B Axilla of a 65-year-old White man with erythrasma showing a well-demarcated erythematous plaque with fine scale (A). Wood lamp examination of the area showed characteristic bright coral red fluorescence (B).

C and D A well-demarcated, red-brown plaque with fine scale in the antecubital fossa of an obese Hispanic woman (C). Wood lamp examination revealed bright coral red fluorescence (D).

E Hypopigmented patches in the groin with pruritus in a Black man. He also had erythrasma between the toes.

Erythrasma is a skin condition caused by acute or chronic infection of the outermost layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum) with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It has a predilection for intertriginous regions such as the axillae, groin, and interdigital spaces of the toes. It can be associated with pruritus or can be asymptomatic.

Epidemiology

Erythrasma typically affects adults, with greater prevalence among those residing in shared living facilities, such as dormitories or nursing homes, or in humid climates.1 It is a common disorder with an estimated prevalence of 17.6% of bacterial skin infections in elderly patients and 44% of diabetic interdigital toe space infections.2,3

Key clinical features

Erythrasma can manifest as red-brown hyperpigmented plaques with fine scale and little central clearing (Figures A and C) or as a hypopigmented patch (Figure E) with a sharply marginated, hyperpigmented border in patients with skin of color. In the interdigital toe spaces, the skin often is white and macerated. These findings may appear in patients of all skin tones.

Worth noting

• Corynebacterium minutissimum produces coproporphyrin III, which glows fluorescent red under Wood lamp examination (Figures B and D). A recent shower or bath may remove the fluorescent coproporphyrins and cause a false-negative result. The interdigital space between the fourth and fifth toes is a common location for C minutissimum; thus clinicians should consider examining these areas with a Wood lamp.

• Associated risk factors include obesity, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and excessive sweating.1

• The differential diagnosis includes intertrigo, inverse psoriasis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome), acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea pedis when present in the interdigital toe spaces. Plaques occurring in circular patterns may be mistaken for tinea corporis or pityriasis rotunda.

• There is a high prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis, and it may exacerbate psoriatic plaques.4

• Treatment options include application of topical clindamycin or erythromycin to the affected area.1 Some patients have responded to topical mupiricin.2 For larger areas, a 1-g dose of clarithromycin5 or a 14-day course of erythromycin may be appropriate.1 Avoid prescribing clarithromycin to patients with preexisting heart disease due to its increased risk for cardiac events or death; consider other agents.

Health disparity highlight

Obesity, most prevalent in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%) and Hispanic adults (45.6%) followed by non- Hispanic White adults (41.4%),6 may cause velvety dark plaques on the neck called acanthosis nigricans. However, acute or chronic erythrasma also may cause hyperpigmentation of the body folds. Although the pathology of erythrasma is due to bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the stratum corneum, acanthosis nigricans is due to fibroblast proliferation and stimulation of epidermal keratinocytes likely from increased growth factors and insulinlike growth factor.7 If erythrasma is mistaken for acanthosis nigricans, the patient may be counseled inappropriately that the hyperpigmentation is something not easily resolved and subsequently left with an active treatable condition that adversely affects their quality of life.

- Groves JB, Nassereddin A, Freeman AM. Erythrasma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; August 11, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513352/

- Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment [published online September 30, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E10733. doi:10.7759/cureus.10733

- Polat M, I˙lhan MN. Dermatological complaints of the elderly attending a dermatology outpatient clinic in Turkey: a prospective study over a one-year period. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:277-281.

- Janeczek M, Kozel Z, Bhasin R, et al. High prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:12-14.

- Khan MJ. Interdigital pedal erythrasma treated with one-time dose of oral clarithromycin 1 g: two case reports [published online February 6, 2020]. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:672-674. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2712

- Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll M, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports. Published June 14, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273

- Brady MF, Rawla P. Acanthosis nigricans. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated October 9, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431057

- Groves JB, Nassereddin A, Freeman AM. Erythrasma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; August 11, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513352/

- Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment [published online September 30, 2020]. Cureus. 2020;12:E10733. doi:10.7759/cureus.10733

- Polat M, I˙lhan MN. Dermatological complaints of the elderly attending a dermatology outpatient clinic in Turkey: a prospective study over a one-year period. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:277-281.

- Janeczek M, Kozel Z, Bhasin R, et al. High prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:12-14.

- Khan MJ. Interdigital pedal erythrasma treated with one-time dose of oral clarithromycin 1 g: two case reports [published online February 6, 2020]. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:672-674. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2712

- Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll M, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports. Published June 14, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273

- Brady MF, Rawla P. Acanthosis nigricans. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated October 9, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431057

Immunity debt and the tripledemic

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza cases are surging to record numbers this winter in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic when children were sheltering in the home, receiving virtual education, masking, and hand sanitizing, and when other precautionary health measures were in place.

RSV and flu illness in children now have hospital emergency rooms and pediatric ICUs and wards over capacity. As these respiratory infections increase and variants of SARS-CoV-2 come to dominate, we may expect the full impact of a tripledemic (RSV + flu + SARS-CoV-2).

It has been estimated that RSV causes 33 million lower respiratory infections and 3.6 million hospitalizations annually worldwide in children younger than 5 years old (Lancet. 2022 May 19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0). RSV is typically a seasonal respiratory infection occurring in late fall through early winter, when it gives way to dominance by flu. Thus, we have experienced an out-of-season surge in RSV since it began in early fall 2022, and it persists. A likely explanation for the early and persisting surge in RSV is immunity debt (Infect Dis Now. 2021 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.05.004).

Immunity debt is an unintended consequence of prevention of infections that occurred because of public health measures to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 infections. The COVID-19 lockdown undoubtedly saved many lives. However, while we were sheltering from SARS-CoV-2 infections, we also were avoiding other infections, especially other respiratory infections such as RSV and flu.

Our group studied this in community-based pediatric practices in Rochester, N.Y. Physician-diagnosed, medically attended infectious disease illness visits were assessed in two child cohorts, age 6-36 months from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (the pandemic period), compared with the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). One hundred forty-four children were included in the pandemic cohort and 215 in the prepandemic cohort. Visits for bronchiolitis were 7.4-fold lower (P = .04), acute otitis media 3.7-fold lower (P < .0001), viral upper respiratory infections (URI) 3.8-fold lower (P < .0001), and croup 27.5-fold lower (P < .0001) in the pandemic than the prepandemic cohort (Front Pediatr. 2021 Sep 13. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.72248).

The significant reduction in respiratory illness during the COVID-19 epidemic we and others observed resulted in a large pool of children who did not experience RSV or flu infections for an entire year or more. Herd immunity dropped. The susceptible child population increased, including children older than typically seen. We had an immunity debt that had to be repaid, and the repayment is occurring now.

As a consequence of the surge in RSV, interest in prevention has gained more attention. In 1966, tragically, two infant deaths and hospitalization of 80% of the participating infants occurred during a clinical trial of an experimental candidate RSV vaccine, which contained an inactivated version of the entire virus. The severe side effect was later found to be caused by both an antibody and a T-cell problem. The antibody produced in response to the inactivated whole virus didn’t have very good functional activity at blocking or neutralizing the virus. That led to deposition of immune complexes and activation of complement that damaged the airways. The vaccine also triggered a T-cell response with inflammatory cytokine release that added to airway obstruction and lack of clearance of the virus. RSV vaccine development was halted and the bar for further studies was raised very high to ensure safety of any future RSV vaccines. Now, 55 years later, two RSV vaccines and a new preventive monoclonal antibody are nearing licensure.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Pfizer are in phase 3 clinical trials of a safer RSV vaccine that contains only the RSV surface protein known as protein F. Protein F changes its structure when the virus infects and fuses with human respiratory epithelial cells. The GSK and Pfizer vaccines use a molecular strategy developed at the National Institutes of Health to lock protein F into its original, prefusion configuration. A similar strategy was used by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna in their design of mRNA vaccines to the SARS-CoV-2 spike surface protein.

A vaccine with the F protein in its prefusion form takes care of the antibody problem that caused the severe side-effects from the 1966 version of inactivated whole virus vaccine because it induces very high-efficiency, high-potency antibodies that neutralize the RSV. The T-cell response is not as well understood and that is why studies are being done in adults first and then moving to young infants.

The new RSV vaccines are being developed for use in adults over age 60, adults with comorbidities, maternal immunization, and infants. Encouraging results were recently reported by GSK and Pfizer from adult trials. In an interim analysis, Pfizer also recently reported that maternal immunization in the late second or third trimester with their vaccine had an efficacy of 82% within a newborn’s first 90 days of life against severe lower respiratory tract illness. At age 6 months, the efficacy was sustained at 69%. So far, both the GSK and Pfizer RSV vaccines have shown a favorable safety profile.

Another strategy in the RSV prevention field has been a monoclonal antibody. Palivizumab (Synagis, AstraZeneca) is used to prevent severe RSV infections in prematurely born and other infants who are at higher risk of mortality and severe morbidity. Soon there will likely be another monoclonal antibody, called nirsevimab (Beyfortus, AstraZeneca and Sanofi). It is approved in Europe but not yet approved in the United States as I prepare this column. Nirsevimab may be even better than palivizumab – based on phase 3 trial data – and a single injection lasts through an entire normal RSV season while palivizumab requires monthly injections.

Similar to the situation with RSV, the flu season started earlier than usual in fall 2022 and has been picking up steam, likely also because of immunity debt. The WHO estimates that annual epidemics of influenza cause 1 billion infections, 3 million to 5 million severe cases, and 300,000-500,000 deaths. Seasonal flu vaccines provide modest protection. Current flu vaccine formulations consist of the hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) proteins but those proteins change sufficiently (called antigenic drift) such that production of the vaccines based on a best guess each year often is not correct for the influenza A or influenza B strains that circulate in a given year (antigenic mismatch).

Public health authorities have long worried about a major change in the composition of the H and N proteins of the influenza virus (called antigenic shift). Preparedness and response to the COVID-19 pandemic was based on preparedness and response to an anticipated influenza pandemic similar to the 1918 flu pandemic. For flu, new “universal” vaccines are in development. Among the candidate vaccines are mRNA vaccines, building on the success of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines (Science. 2022 Nov 24. doi: 10.1126/science.abm0271).

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza cases are surging to record numbers this winter in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic when children were sheltering in the home, receiving virtual education, masking, and hand sanitizing, and when other precautionary health measures were in place.

RSV and flu illness in children now have hospital emergency rooms and pediatric ICUs and wards over capacity. As these respiratory infections increase and variants of SARS-CoV-2 come to dominate, we may expect the full impact of a tripledemic (RSV + flu + SARS-CoV-2).

It has been estimated that RSV causes 33 million lower respiratory infections and 3.6 million hospitalizations annually worldwide in children younger than 5 years old (Lancet. 2022 May 19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0). RSV is typically a seasonal respiratory infection occurring in late fall through early winter, when it gives way to dominance by flu. Thus, we have experienced an out-of-season surge in RSV since it began in early fall 2022, and it persists. A likely explanation for the early and persisting surge in RSV is immunity debt (Infect Dis Now. 2021 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.05.004).

Immunity debt is an unintended consequence of prevention of infections that occurred because of public health measures to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 infections. The COVID-19 lockdown undoubtedly saved many lives. However, while we were sheltering from SARS-CoV-2 infections, we also were avoiding other infections, especially other respiratory infections such as RSV and flu.

Our group studied this in community-based pediatric practices in Rochester, N.Y. Physician-diagnosed, medically attended infectious disease illness visits were assessed in two child cohorts, age 6-36 months from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (the pandemic period), compared with the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). One hundred forty-four children were included in the pandemic cohort and 215 in the prepandemic cohort. Visits for bronchiolitis were 7.4-fold lower (P = .04), acute otitis media 3.7-fold lower (P < .0001), viral upper respiratory infections (URI) 3.8-fold lower (P < .0001), and croup 27.5-fold lower (P < .0001) in the pandemic than the prepandemic cohort (Front Pediatr. 2021 Sep 13. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.72248).

The significant reduction in respiratory illness during the COVID-19 epidemic we and others observed resulted in a large pool of children who did not experience RSV or flu infections for an entire year or more. Herd immunity dropped. The susceptible child population increased, including children older than typically seen. We had an immunity debt that had to be repaid, and the repayment is occurring now.

As a consequence of the surge in RSV, interest in prevention has gained more attention. In 1966, tragically, two infant deaths and hospitalization of 80% of the participating infants occurred during a clinical trial of an experimental candidate RSV vaccine, which contained an inactivated version of the entire virus. The severe side effect was later found to be caused by both an antibody and a T-cell problem. The antibody produced in response to the inactivated whole virus didn’t have very good functional activity at blocking or neutralizing the virus. That led to deposition of immune complexes and activation of complement that damaged the airways. The vaccine also triggered a T-cell response with inflammatory cytokine release that added to airway obstruction and lack of clearance of the virus. RSV vaccine development was halted and the bar for further studies was raised very high to ensure safety of any future RSV vaccines. Now, 55 years later, two RSV vaccines and a new preventive monoclonal antibody are nearing licensure.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Pfizer are in phase 3 clinical trials of a safer RSV vaccine that contains only the RSV surface protein known as protein F. Protein F changes its structure when the virus infects and fuses with human respiratory epithelial cells. The GSK and Pfizer vaccines use a molecular strategy developed at the National Institutes of Health to lock protein F into its original, prefusion configuration. A similar strategy was used by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna in their design of mRNA vaccines to the SARS-CoV-2 spike surface protein.

A vaccine with the F protein in its prefusion form takes care of the antibody problem that caused the severe side-effects from the 1966 version of inactivated whole virus vaccine because it induces very high-efficiency, high-potency antibodies that neutralize the RSV. The T-cell response is not as well understood and that is why studies are being done in adults first and then moving to young infants.

The new RSV vaccines are being developed for use in adults over age 60, adults with comorbidities, maternal immunization, and infants. Encouraging results were recently reported by GSK and Pfizer from adult trials. In an interim analysis, Pfizer also recently reported that maternal immunization in the late second or third trimester with their vaccine had an efficacy of 82% within a newborn’s first 90 days of life against severe lower respiratory tract illness. At age 6 months, the efficacy was sustained at 69%. So far, both the GSK and Pfizer RSV vaccines have shown a favorable safety profile.

Another strategy in the RSV prevention field has been a monoclonal antibody. Palivizumab (Synagis, AstraZeneca) is used to prevent severe RSV infections in prematurely born and other infants who are at higher risk of mortality and severe morbidity. Soon there will likely be another monoclonal antibody, called nirsevimab (Beyfortus, AstraZeneca and Sanofi). It is approved in Europe but not yet approved in the United States as I prepare this column. Nirsevimab may be even better than palivizumab – based on phase 3 trial data – and a single injection lasts through an entire normal RSV season while palivizumab requires monthly injections.

Similar to the situation with RSV, the flu season started earlier than usual in fall 2022 and has been picking up steam, likely also because of immunity debt. The WHO estimates that annual epidemics of influenza cause 1 billion infections, 3 million to 5 million severe cases, and 300,000-500,000 deaths. Seasonal flu vaccines provide modest protection. Current flu vaccine formulations consist of the hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) proteins but those proteins change sufficiently (called antigenic drift) such that production of the vaccines based on a best guess each year often is not correct for the influenza A or influenza B strains that circulate in a given year (antigenic mismatch).

Public health authorities have long worried about a major change in the composition of the H and N proteins of the influenza virus (called antigenic shift). Preparedness and response to the COVID-19 pandemic was based on preparedness and response to an anticipated influenza pandemic similar to the 1918 flu pandemic. For flu, new “universal” vaccines are in development. Among the candidate vaccines are mRNA vaccines, building on the success of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines (Science. 2022 Nov 24. doi: 10.1126/science.abm0271).

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza cases are surging to record numbers this winter in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic when children were sheltering in the home, receiving virtual education, masking, and hand sanitizing, and when other precautionary health measures were in place.

RSV and flu illness in children now have hospital emergency rooms and pediatric ICUs and wards over capacity. As these respiratory infections increase and variants of SARS-CoV-2 come to dominate, we may expect the full impact of a tripledemic (RSV + flu + SARS-CoV-2).

It has been estimated that RSV causes 33 million lower respiratory infections and 3.6 million hospitalizations annually worldwide in children younger than 5 years old (Lancet. 2022 May 19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0). RSV is typically a seasonal respiratory infection occurring in late fall through early winter, when it gives way to dominance by flu. Thus, we have experienced an out-of-season surge in RSV since it began in early fall 2022, and it persists. A likely explanation for the early and persisting surge in RSV is immunity debt (Infect Dis Now. 2021 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.05.004).

Immunity debt is an unintended consequence of prevention of infections that occurred because of public health measures to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 infections. The COVID-19 lockdown undoubtedly saved many lives. However, while we were sheltering from SARS-CoV-2 infections, we also were avoiding other infections, especially other respiratory infections such as RSV and flu.

Our group studied this in community-based pediatric practices in Rochester, N.Y. Physician-diagnosed, medically attended infectious disease illness visits were assessed in two child cohorts, age 6-36 months from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (the pandemic period), compared with the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). One hundred forty-four children were included in the pandemic cohort and 215 in the prepandemic cohort. Visits for bronchiolitis were 7.4-fold lower (P = .04), acute otitis media 3.7-fold lower (P < .0001), viral upper respiratory infections (URI) 3.8-fold lower (P < .0001), and croup 27.5-fold lower (P < .0001) in the pandemic than the prepandemic cohort (Front Pediatr. 2021 Sep 13. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.72248).

The significant reduction in respiratory illness during the COVID-19 epidemic we and others observed resulted in a large pool of children who did not experience RSV or flu infections for an entire year or more. Herd immunity dropped. The susceptible child population increased, including children older than typically seen. We had an immunity debt that had to be repaid, and the repayment is occurring now.

As a consequence of the surge in RSV, interest in prevention has gained more attention. In 1966, tragically, two infant deaths and hospitalization of 80% of the participating infants occurred during a clinical trial of an experimental candidate RSV vaccine, which contained an inactivated version of the entire virus. The severe side effect was later found to be caused by both an antibody and a T-cell problem. The antibody produced in response to the inactivated whole virus didn’t have very good functional activity at blocking or neutralizing the virus. That led to deposition of immune complexes and activation of complement that damaged the airways. The vaccine also triggered a T-cell response with inflammatory cytokine release that added to airway obstruction and lack of clearance of the virus. RSV vaccine development was halted and the bar for further studies was raised very high to ensure safety of any future RSV vaccines. Now, 55 years later, two RSV vaccines and a new preventive monoclonal antibody are nearing licensure.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Pfizer are in phase 3 clinical trials of a safer RSV vaccine that contains only the RSV surface protein known as protein F. Protein F changes its structure when the virus infects and fuses with human respiratory epithelial cells. The GSK and Pfizer vaccines use a molecular strategy developed at the National Institutes of Health to lock protein F into its original, prefusion configuration. A similar strategy was used by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna in their design of mRNA vaccines to the SARS-CoV-2 spike surface protein.

A vaccine with the F protein in its prefusion form takes care of the antibody problem that caused the severe side-effects from the 1966 version of inactivated whole virus vaccine because it induces very high-efficiency, high-potency antibodies that neutralize the RSV. The T-cell response is not as well understood and that is why studies are being done in adults first and then moving to young infants.

The new RSV vaccines are being developed for use in adults over age 60, adults with comorbidities, maternal immunization, and infants. Encouraging results were recently reported by GSK and Pfizer from adult trials. In an interim analysis, Pfizer also recently reported that maternal immunization in the late second or third trimester with their vaccine had an efficacy of 82% within a newborn’s first 90 days of life against severe lower respiratory tract illness. At age 6 months, the efficacy was sustained at 69%. So far, both the GSK and Pfizer RSV vaccines have shown a favorable safety profile.

Another strategy in the RSV prevention field has been a monoclonal antibody. Palivizumab (Synagis, AstraZeneca) is used to prevent severe RSV infections in prematurely born and other infants who are at higher risk of mortality and severe morbidity. Soon there will likely be another monoclonal antibody, called nirsevimab (Beyfortus, AstraZeneca and Sanofi). It is approved in Europe but not yet approved in the United States as I prepare this column. Nirsevimab may be even better than palivizumab – based on phase 3 trial data – and a single injection lasts through an entire normal RSV season while palivizumab requires monthly injections.

Similar to the situation with RSV, the flu season started earlier than usual in fall 2022 and has been picking up steam, likely also because of immunity debt. The WHO estimates that annual epidemics of influenza cause 1 billion infections, 3 million to 5 million severe cases, and 300,000-500,000 deaths. Seasonal flu vaccines provide modest protection. Current flu vaccine formulations consist of the hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) proteins but those proteins change sufficiently (called antigenic drift) such that production of the vaccines based on a best guess each year often is not correct for the influenza A or influenza B strains that circulate in a given year (antigenic mismatch).

Public health authorities have long worried about a major change in the composition of the H and N proteins of the influenza virus (called antigenic shift). Preparedness and response to the COVID-19 pandemic was based on preparedness and response to an anticipated influenza pandemic similar to the 1918 flu pandemic. For flu, new “universal” vaccines are in development. Among the candidate vaccines are mRNA vaccines, building on the success of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines (Science. 2022 Nov 24. doi: 10.1126/science.abm0271).

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

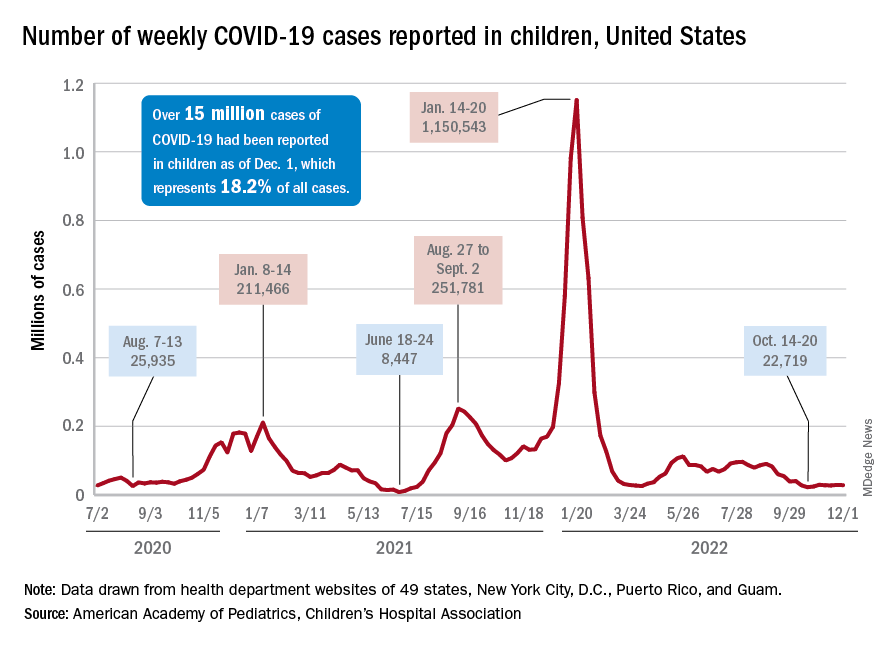

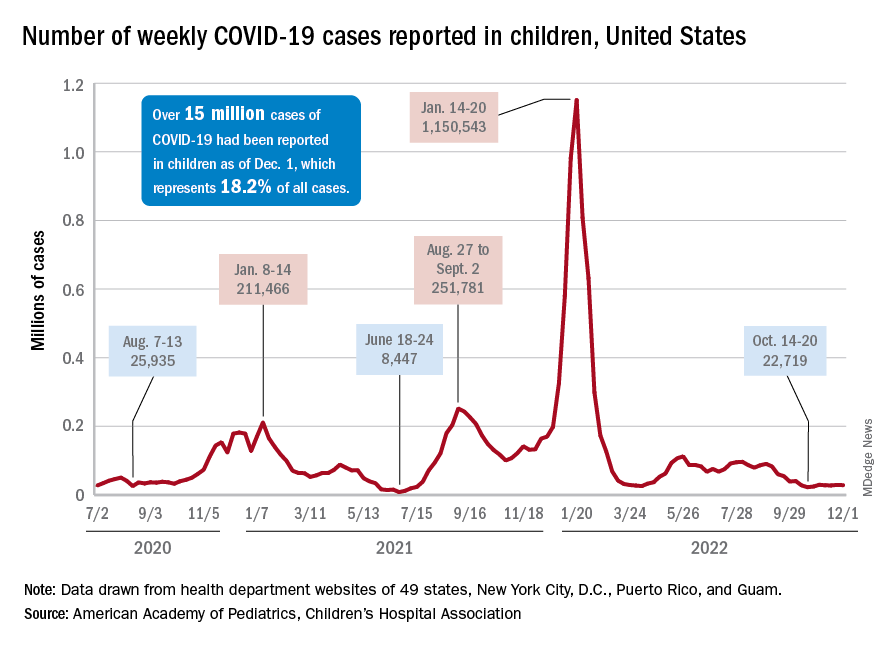

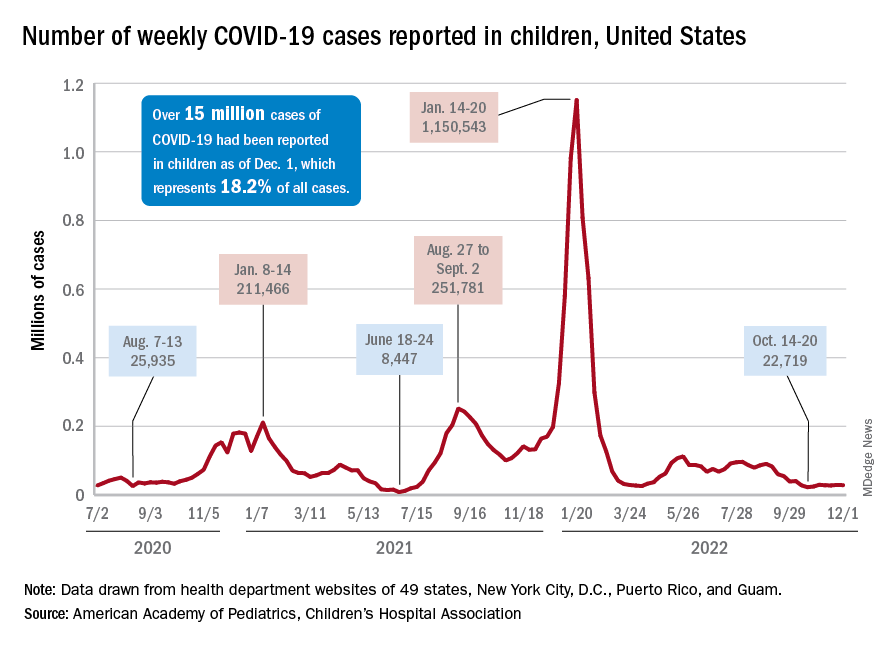

Children and COVID: Hospitalizations provide a tale of two sources

New cases of COVID-19 in children largely held steady over the Thanksgiving holiday, but hospital admissions are telling a somewhat different story.