User login

For MD-IQ use only

Are oncologists any better at facing their own mortality?

Douglas Flora, MD, an oncologist with St. Elizabeth Healthcare, in Edgewood, Ky., considers himself a deep empath. It’s one reason he became an oncologist.

But when he was diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2017, he was shocked at the places his brain took him. His mind fast-forwarded through treatment options, statistical probabilities, and anguish over his wife and children.

“It’s a very surreal experience,” Dr. Flora said. “In 20 seconds, you go from diagnostics to, ‘What videos will I have to film for my babies?’ “

He could be having a wonderful evening surrounded by friends, music, and beer. Then he would go to the restroom and the realization of what was lurking inside his would body hit him like a brick.

“It’s like the scene in the Harry Potter movies where the Dementors fly over,” he explained. “Everything feels dark. There’s no hope. Everything you thought was good is gone.”

Oncologists counsel patients through life-threatening diagnoses and frightening decisions every day, so one might think they’d be ready to confront their own diagnosis, treatment, and mortality better than anyone. But that’s not always the case.

Does their expertise equip them to navigate their diagnosis and treatment better than their patients? How does the emotional toll of their personal cancer journey change the way they interact with their patients?

Navigating the diagnosis and treatment

In January 2017, Karen Hendershott, MD, a breast surgical oncologist, felt a lump in her armpit while taking a shower. The blunt force of her fate came into view in an instant: It was almost certainly a locally advanced breast cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes and would require surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.

She said a few unprintable words and headed to work at St. Mary’s Hospital, in Tucson, Ariz., where her assumptions were confirmed.

Taylor Riall, MD, PhD, also suspected cancer.

Last December, Dr. Riall, a general surgeon and surgical oncologist at the University of Arizona Cancer Center, in Tucson, developed a persistent cough. An x-ray revealed a mass in her lung. Initially, she was misdiagnosed with a fungal infection and was given medication that made her skin peel off.

Doctors advised Dr. Riall to monitor her condition for another 6 months. But her knowledge of oncology made her think cancer, so she insisted on more tests. In June 2021, a biopsy confirmed she had lung cancer.

Having oncology expertise helped Dr. Riall and Dr. Hendershott recognize the signs of cancer and push for a diagnosis. But there are also downsides to being hyper-informed, Dr. Hendershott, said.

“I think sometimes knowing everything at once is harder vs. giving yourself time to wrap your mind around this and do it in baby steps,” she explained. “There weren’t any baby steps here.”

Still, oncology practitioners who are diagnosed with cancer are navigating a familiar landscape and are often buoyed by a support network of expert colleagues. That makes a huge difference psychologically, explained Shenitha Edwards, a pharmacy technician at Cancer Specialists of North Florida, in Jacksonville, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in July.

“I felt stronger and a little more ready to fight because I had resources, whereas my patients sometimes do not,” Ms. Edwards said. “I was connected with a lot of people who could help me make informed decisions, so I didn’t have to walk so much in fear.”

It can also prepare practitioners to make bold treatment choices. In Dr. Riall’s case, surgeons were reluctant to excise her tumor because they would have to remove the entire upper lobe of her lung, and she is a marathoner and triathlete. Still, because of her surgical oncology experience, Dr. Riall didn’t flinch at the prospect of a major operation.

“I was, like, ‘Look, just take it out.’ I’m less afraid to have cancer than I am to not know and let it grow,” said Dr. Riall, whose Peloton name is WhoNeeds2Lungs.

Similarly, Dr. Hendershott’s experience gave her the assurance to pursue a more intense strategy. “Because I had a really candid understanding of the risks and what the odds looked like, it helped me be more comfortable with a more aggressive approach,” she said. “There wasn’t a doubt in my mind, particularly [having] a 10-year-old child, that I wanted to do everything I could, and even do a couple of things that were still in clinical trials.”

Almost paradoxically, Mark Lewis’ oncology training gave him the courage to risk watching and waiting after finding benign growths in his parathyroid and malignant tumors in his pancreas. Dr. Lewis monitored the tumors amassing in his pancreas for 8 years. When some grew so large they threatened to metastasize to his liver, he underwent the Whipple procedure to remove the head of the pancreas, part of the small intestine, and the gallbladder.

“It was a bit of a gamble, but one that paid off and allowed me to get my career off the ground and have another child,” said Dr. Lewis, a gastrointestinal oncologist at Intermountain Healthcare, in Salt Lake City. Treating patients for nearly a decade also showed him how fortunate he was to have a slow-growing, operable cancer. That gratitude, he said, gave him mental strength to endure the ordeal.

Whether taking a more aggressive or minimalist approach to their own care, each practitioner’s decision was deeply personal and deeply informed by their oncology expertise.

Although research on this question is scarce, studies show that differences in end-of-life care may occur. According to a 2016 study published in JAMA, physicians choose significantly less intensive end-stage care in three of five categories — undergoing surgery, being admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and dying in the hospital — than the general U.S. population. The reason, the researchers posited, is because doctors know these eleventh-hour interventions are typically brutal and futile.

But these differences were fairly small, and a 2019 study published in JAMA Open Network found the opposite: Physicians with cancer were more likely to die in an ICU and receive chemotherapy in the last 6 months of life, suggesting a more aggressive approach to end-of-life care.

When it comes to their own long-term or curative cancer care, oncologists generally don’t seem to approach treatment differently than their patients. In a 2015 study, researchers compared two groups of people with early breast cancer — 46 physicians and 230 well-educated, nonmedically qualified patients — and found no differences in the choices the groups made about whether to undergo mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or breast reconstruction.

Still, no amount of oncology expertise can fully prepare a person for the emotional crucible of cancer.

“A very surreal experience”

Although the fear can become less intense and more manageable over time, it may never truly go away.

At first, despair dragged Flora into an abyss for 6 hours a night, then overcame him 10 times a day, then gripped him briefly at random moments. Four years later and cancer-free, the dread still returns.

Hendershott cried every time she got into her car and contemplated her prognosis. Now 47, she has about a 60% chance of being alive in 15 years, and the fear still hits her.

“I think it’s hard to understand the moments of sheer terror that you have at 2 AM when you’re confronting your own mortality,” she said. “The implications that has not just for you but more importantly for the people that you love and want to protect. That just kind of washes over you in waves that you don’t have much control over.”

Cancer, Riall felt, had smashed her life, but she figured out a way to help herself cope. Severe blood loss, chest tubes, and tests and needles ad nauseum left Riall feeling excruciatingly exhausted after her surgery and delayed her return to work. At the same time, she was passed over for a promotion. Frustrated and dejected, she took comfort in the memory of doing Kintsugi with her surgery residents. The Japanese art form involves shattering pottery with a hammer, fitting the fragments back together, and painting the cracks gold.

“My instinct as a surgeon is to pick up those pieces and put them back together so nobody sees it’s broken,” she reflected. But as a patient, she learned that an important part of recovery is to allow yourself to sit in a broken state and feel angry, miserable, and betrayed by your body. And then examine your shattered priorities and consider how you want to reassemble them.

For Barbara Buttin, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at Cancer Treatment Centers of America, in Chicago, Illinois, it wasn’t cancer that almost took her life. Rather, a near-death experience and life-threatening diagnosis made her a better, more empathetic cancer doctor — a refrain echoed by many oncologist-patients. Confronting her own mortality crystallized what matters in life. She uses that understanding to make sure she understands what matters to her patients ― what they care about most, what their greatest fear is, what is going to keep them up at night.

“We’re part of the same club”

Ultimately, when oncology practitioners become patients, it balances the in-control and vulnerable, the rational and emotional. And their patients respond positively.

In fall 2020, oncology nurse Jenn Adams, RN, turned 40 and underwent her first mammogram. Unexpectedly, it revealed invasive stage I cancer that would require a double mastectomy, chemotherapy, and a year of immunotherapy. A week after her diagnosis, she was scheduled to start a new job at Cancer Clinic, in Bryan, Tex. So, she asked her manager if she could become a patient and an employee.

Ms. Adams worked 5 days a week, but every Thursday at 2 PM, she sat next to her patients while her coworkers became her nurses. Her chemo port was implanted, she lost her hair, and she felt terrible along with her patients. “It just created this incredible bond,” said the mother of three.

Having cancer, Dr. Flora said, “was completely different than I had imagined. When I thought I was walking with [my patients] in the depths of their caves, I wasn’t even visiting their caves.” But, he added, it has also “let me connect with [patients] on a deeper level because we’re part of the same club. You can see their body language change when I share that. They almost relax, like, ‘Oh, this guy gets it. He does understand how terrified I am.’ And I do.”

When Dr. Flora’s patients are scanned, he gives them their results immediately, because he knows what it’s like to wait on tenterhooks. He tells his patients to text him anytime they’re afraid or depressed, which he admits isn’t great for his own mental health but believes is worth it.

Likewise, Dr. Hendershott can hold out her shoulder-length locks to reassure a crying patient that hair does grow back after chemo. She can describe her experience with hormone-blocking pills to allay the fears of a pharmaceutical skeptic.

This role equalizer fosters so much empathy that doctors sometimes find themselves being helped by their patients. When one of Dr. Flora’s patients heard he had cancer, she sent him an email that began. “A wise doctor once told me....” and repeated the advice he’d given her years before.

Dr. Lewis has a special bond with his patients because people who have pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors seek him out for treatment. “I’m getting to take care of people who, on some level, are like my kindred spirits,” he said. “So, I get to see their coping mechanisms and how they do.”

Ms. Edwards told some of her patients about her breast cancer diagnosis, and now they give each other high-fives and share words of encouragement. “I made it a big thing of mine to associate my patients as my family,” she said. “If you’ve learned to embrace love and love people, there’s nothing you wouldn’t do for people. I’ve chosen that to be my practice when I’m dealing with all of my patients.”

Ms. Adams is on a similar mission. She joined a group of moms with cancer so she can receive guidance and then become a guide for others. “I feel like that’s what I want to be at my cancer practice,” she said, “so [my patients] have someone to say, ‘I’m gonna walk alongside you because I’ve been there.’ “

That transformation has made all the heartbreaking moments worth it, Ms. Adams said. “I love the oncology nurse that I get to be now because of my diagnosis. I don’t love the diagnosis. But I love the way it’s changed what I do.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Douglas Flora, MD, an oncologist with St. Elizabeth Healthcare, in Edgewood, Ky., considers himself a deep empath. It’s one reason he became an oncologist.

But when he was diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2017, he was shocked at the places his brain took him. His mind fast-forwarded through treatment options, statistical probabilities, and anguish over his wife and children.

“It’s a very surreal experience,” Dr. Flora said. “In 20 seconds, you go from diagnostics to, ‘What videos will I have to film for my babies?’ “

He could be having a wonderful evening surrounded by friends, music, and beer. Then he would go to the restroom and the realization of what was lurking inside his would body hit him like a brick.

“It’s like the scene in the Harry Potter movies where the Dementors fly over,” he explained. “Everything feels dark. There’s no hope. Everything you thought was good is gone.”

Oncologists counsel patients through life-threatening diagnoses and frightening decisions every day, so one might think they’d be ready to confront their own diagnosis, treatment, and mortality better than anyone. But that’s not always the case.

Does their expertise equip them to navigate their diagnosis and treatment better than their patients? How does the emotional toll of their personal cancer journey change the way they interact with their patients?

Navigating the diagnosis and treatment

In January 2017, Karen Hendershott, MD, a breast surgical oncologist, felt a lump in her armpit while taking a shower. The blunt force of her fate came into view in an instant: It was almost certainly a locally advanced breast cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes and would require surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.

She said a few unprintable words and headed to work at St. Mary’s Hospital, in Tucson, Ariz., where her assumptions were confirmed.

Taylor Riall, MD, PhD, also suspected cancer.

Last December, Dr. Riall, a general surgeon and surgical oncologist at the University of Arizona Cancer Center, in Tucson, developed a persistent cough. An x-ray revealed a mass in her lung. Initially, she was misdiagnosed with a fungal infection and was given medication that made her skin peel off.

Doctors advised Dr. Riall to monitor her condition for another 6 months. But her knowledge of oncology made her think cancer, so she insisted on more tests. In June 2021, a biopsy confirmed she had lung cancer.

Having oncology expertise helped Dr. Riall and Dr. Hendershott recognize the signs of cancer and push for a diagnosis. But there are also downsides to being hyper-informed, Dr. Hendershott, said.

“I think sometimes knowing everything at once is harder vs. giving yourself time to wrap your mind around this and do it in baby steps,” she explained. “There weren’t any baby steps here.”

Still, oncology practitioners who are diagnosed with cancer are navigating a familiar landscape and are often buoyed by a support network of expert colleagues. That makes a huge difference psychologically, explained Shenitha Edwards, a pharmacy technician at Cancer Specialists of North Florida, in Jacksonville, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in July.

“I felt stronger and a little more ready to fight because I had resources, whereas my patients sometimes do not,” Ms. Edwards said. “I was connected with a lot of people who could help me make informed decisions, so I didn’t have to walk so much in fear.”

It can also prepare practitioners to make bold treatment choices. In Dr. Riall’s case, surgeons were reluctant to excise her tumor because they would have to remove the entire upper lobe of her lung, and she is a marathoner and triathlete. Still, because of her surgical oncology experience, Dr. Riall didn’t flinch at the prospect of a major operation.

“I was, like, ‘Look, just take it out.’ I’m less afraid to have cancer than I am to not know and let it grow,” said Dr. Riall, whose Peloton name is WhoNeeds2Lungs.

Similarly, Dr. Hendershott’s experience gave her the assurance to pursue a more intense strategy. “Because I had a really candid understanding of the risks and what the odds looked like, it helped me be more comfortable with a more aggressive approach,” she said. “There wasn’t a doubt in my mind, particularly [having] a 10-year-old child, that I wanted to do everything I could, and even do a couple of things that were still in clinical trials.”

Almost paradoxically, Mark Lewis’ oncology training gave him the courage to risk watching and waiting after finding benign growths in his parathyroid and malignant tumors in his pancreas. Dr. Lewis monitored the tumors amassing in his pancreas for 8 years. When some grew so large they threatened to metastasize to his liver, he underwent the Whipple procedure to remove the head of the pancreas, part of the small intestine, and the gallbladder.

“It was a bit of a gamble, but one that paid off and allowed me to get my career off the ground and have another child,” said Dr. Lewis, a gastrointestinal oncologist at Intermountain Healthcare, in Salt Lake City. Treating patients for nearly a decade also showed him how fortunate he was to have a slow-growing, operable cancer. That gratitude, he said, gave him mental strength to endure the ordeal.

Whether taking a more aggressive or minimalist approach to their own care, each practitioner’s decision was deeply personal and deeply informed by their oncology expertise.

Although research on this question is scarce, studies show that differences in end-of-life care may occur. According to a 2016 study published in JAMA, physicians choose significantly less intensive end-stage care in three of five categories — undergoing surgery, being admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and dying in the hospital — than the general U.S. population. The reason, the researchers posited, is because doctors know these eleventh-hour interventions are typically brutal and futile.

But these differences were fairly small, and a 2019 study published in JAMA Open Network found the opposite: Physicians with cancer were more likely to die in an ICU and receive chemotherapy in the last 6 months of life, suggesting a more aggressive approach to end-of-life care.

When it comes to their own long-term or curative cancer care, oncologists generally don’t seem to approach treatment differently than their patients. In a 2015 study, researchers compared two groups of people with early breast cancer — 46 physicians and 230 well-educated, nonmedically qualified patients — and found no differences in the choices the groups made about whether to undergo mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or breast reconstruction.

Still, no amount of oncology expertise can fully prepare a person for the emotional crucible of cancer.

“A very surreal experience”

Although the fear can become less intense and more manageable over time, it may never truly go away.

At first, despair dragged Flora into an abyss for 6 hours a night, then overcame him 10 times a day, then gripped him briefly at random moments. Four years later and cancer-free, the dread still returns.

Hendershott cried every time she got into her car and contemplated her prognosis. Now 47, she has about a 60% chance of being alive in 15 years, and the fear still hits her.

“I think it’s hard to understand the moments of sheer terror that you have at 2 AM when you’re confronting your own mortality,” she said. “The implications that has not just for you but more importantly for the people that you love and want to protect. That just kind of washes over you in waves that you don’t have much control over.”

Cancer, Riall felt, had smashed her life, but she figured out a way to help herself cope. Severe blood loss, chest tubes, and tests and needles ad nauseum left Riall feeling excruciatingly exhausted after her surgery and delayed her return to work. At the same time, she was passed over for a promotion. Frustrated and dejected, she took comfort in the memory of doing Kintsugi with her surgery residents. The Japanese art form involves shattering pottery with a hammer, fitting the fragments back together, and painting the cracks gold.

“My instinct as a surgeon is to pick up those pieces and put them back together so nobody sees it’s broken,” she reflected. But as a patient, she learned that an important part of recovery is to allow yourself to sit in a broken state and feel angry, miserable, and betrayed by your body. And then examine your shattered priorities and consider how you want to reassemble them.

For Barbara Buttin, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at Cancer Treatment Centers of America, in Chicago, Illinois, it wasn’t cancer that almost took her life. Rather, a near-death experience and life-threatening diagnosis made her a better, more empathetic cancer doctor — a refrain echoed by many oncologist-patients. Confronting her own mortality crystallized what matters in life. She uses that understanding to make sure she understands what matters to her patients ― what they care about most, what their greatest fear is, what is going to keep them up at night.

“We’re part of the same club”

Ultimately, when oncology practitioners become patients, it balances the in-control and vulnerable, the rational and emotional. And their patients respond positively.

In fall 2020, oncology nurse Jenn Adams, RN, turned 40 and underwent her first mammogram. Unexpectedly, it revealed invasive stage I cancer that would require a double mastectomy, chemotherapy, and a year of immunotherapy. A week after her diagnosis, she was scheduled to start a new job at Cancer Clinic, in Bryan, Tex. So, she asked her manager if she could become a patient and an employee.

Ms. Adams worked 5 days a week, but every Thursday at 2 PM, she sat next to her patients while her coworkers became her nurses. Her chemo port was implanted, she lost her hair, and she felt terrible along with her patients. “It just created this incredible bond,” said the mother of three.

Having cancer, Dr. Flora said, “was completely different than I had imagined. When I thought I was walking with [my patients] in the depths of their caves, I wasn’t even visiting their caves.” But, he added, it has also “let me connect with [patients] on a deeper level because we’re part of the same club. You can see their body language change when I share that. They almost relax, like, ‘Oh, this guy gets it. He does understand how terrified I am.’ And I do.”

When Dr. Flora’s patients are scanned, he gives them their results immediately, because he knows what it’s like to wait on tenterhooks. He tells his patients to text him anytime they’re afraid or depressed, which he admits isn’t great for his own mental health but believes is worth it.

Likewise, Dr. Hendershott can hold out her shoulder-length locks to reassure a crying patient that hair does grow back after chemo. She can describe her experience with hormone-blocking pills to allay the fears of a pharmaceutical skeptic.

This role equalizer fosters so much empathy that doctors sometimes find themselves being helped by their patients. When one of Dr. Flora’s patients heard he had cancer, she sent him an email that began. “A wise doctor once told me....” and repeated the advice he’d given her years before.

Dr. Lewis has a special bond with his patients because people who have pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors seek him out for treatment. “I’m getting to take care of people who, on some level, are like my kindred spirits,” he said. “So, I get to see their coping mechanisms and how they do.”

Ms. Edwards told some of her patients about her breast cancer diagnosis, and now they give each other high-fives and share words of encouragement. “I made it a big thing of mine to associate my patients as my family,” she said. “If you’ve learned to embrace love and love people, there’s nothing you wouldn’t do for people. I’ve chosen that to be my practice when I’m dealing with all of my patients.”

Ms. Adams is on a similar mission. She joined a group of moms with cancer so she can receive guidance and then become a guide for others. “I feel like that’s what I want to be at my cancer practice,” she said, “so [my patients] have someone to say, ‘I’m gonna walk alongside you because I’ve been there.’ “

That transformation has made all the heartbreaking moments worth it, Ms. Adams said. “I love the oncology nurse that I get to be now because of my diagnosis. I don’t love the diagnosis. But I love the way it’s changed what I do.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Douglas Flora, MD, an oncologist with St. Elizabeth Healthcare, in Edgewood, Ky., considers himself a deep empath. It’s one reason he became an oncologist.

But when he was diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2017, he was shocked at the places his brain took him. His mind fast-forwarded through treatment options, statistical probabilities, and anguish over his wife and children.

“It’s a very surreal experience,” Dr. Flora said. “In 20 seconds, you go from diagnostics to, ‘What videos will I have to film for my babies?’ “

He could be having a wonderful evening surrounded by friends, music, and beer. Then he would go to the restroom and the realization of what was lurking inside his would body hit him like a brick.

“It’s like the scene in the Harry Potter movies where the Dementors fly over,” he explained. “Everything feels dark. There’s no hope. Everything you thought was good is gone.”

Oncologists counsel patients through life-threatening diagnoses and frightening decisions every day, so one might think they’d be ready to confront their own diagnosis, treatment, and mortality better than anyone. But that’s not always the case.

Does their expertise equip them to navigate their diagnosis and treatment better than their patients? How does the emotional toll of their personal cancer journey change the way they interact with their patients?

Navigating the diagnosis and treatment

In January 2017, Karen Hendershott, MD, a breast surgical oncologist, felt a lump in her armpit while taking a shower. The blunt force of her fate came into view in an instant: It was almost certainly a locally advanced breast cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes and would require surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.

She said a few unprintable words and headed to work at St. Mary’s Hospital, in Tucson, Ariz., where her assumptions were confirmed.

Taylor Riall, MD, PhD, also suspected cancer.

Last December, Dr. Riall, a general surgeon and surgical oncologist at the University of Arizona Cancer Center, in Tucson, developed a persistent cough. An x-ray revealed a mass in her lung. Initially, she was misdiagnosed with a fungal infection and was given medication that made her skin peel off.

Doctors advised Dr. Riall to monitor her condition for another 6 months. But her knowledge of oncology made her think cancer, so she insisted on more tests. In June 2021, a biopsy confirmed she had lung cancer.

Having oncology expertise helped Dr. Riall and Dr. Hendershott recognize the signs of cancer and push for a diagnosis. But there are also downsides to being hyper-informed, Dr. Hendershott, said.

“I think sometimes knowing everything at once is harder vs. giving yourself time to wrap your mind around this and do it in baby steps,” she explained. “There weren’t any baby steps here.”

Still, oncology practitioners who are diagnosed with cancer are navigating a familiar landscape and are often buoyed by a support network of expert colleagues. That makes a huge difference psychologically, explained Shenitha Edwards, a pharmacy technician at Cancer Specialists of North Florida, in Jacksonville, who was diagnosed with breast cancer in July.

“I felt stronger and a little more ready to fight because I had resources, whereas my patients sometimes do not,” Ms. Edwards said. “I was connected with a lot of people who could help me make informed decisions, so I didn’t have to walk so much in fear.”

It can also prepare practitioners to make bold treatment choices. In Dr. Riall’s case, surgeons were reluctant to excise her tumor because they would have to remove the entire upper lobe of her lung, and she is a marathoner and triathlete. Still, because of her surgical oncology experience, Dr. Riall didn’t flinch at the prospect of a major operation.

“I was, like, ‘Look, just take it out.’ I’m less afraid to have cancer than I am to not know and let it grow,” said Dr. Riall, whose Peloton name is WhoNeeds2Lungs.

Similarly, Dr. Hendershott’s experience gave her the assurance to pursue a more intense strategy. “Because I had a really candid understanding of the risks and what the odds looked like, it helped me be more comfortable with a more aggressive approach,” she said. “There wasn’t a doubt in my mind, particularly [having] a 10-year-old child, that I wanted to do everything I could, and even do a couple of things that were still in clinical trials.”

Almost paradoxically, Mark Lewis’ oncology training gave him the courage to risk watching and waiting after finding benign growths in his parathyroid and malignant tumors in his pancreas. Dr. Lewis monitored the tumors amassing in his pancreas for 8 years. When some grew so large they threatened to metastasize to his liver, he underwent the Whipple procedure to remove the head of the pancreas, part of the small intestine, and the gallbladder.

“It was a bit of a gamble, but one that paid off and allowed me to get my career off the ground and have another child,” said Dr. Lewis, a gastrointestinal oncologist at Intermountain Healthcare, in Salt Lake City. Treating patients for nearly a decade also showed him how fortunate he was to have a slow-growing, operable cancer. That gratitude, he said, gave him mental strength to endure the ordeal.

Whether taking a more aggressive or minimalist approach to their own care, each practitioner’s decision was deeply personal and deeply informed by their oncology expertise.

Although research on this question is scarce, studies show that differences in end-of-life care may occur. According to a 2016 study published in JAMA, physicians choose significantly less intensive end-stage care in three of five categories — undergoing surgery, being admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and dying in the hospital — than the general U.S. population. The reason, the researchers posited, is because doctors know these eleventh-hour interventions are typically brutal and futile.

But these differences were fairly small, and a 2019 study published in JAMA Open Network found the opposite: Physicians with cancer were more likely to die in an ICU and receive chemotherapy in the last 6 months of life, suggesting a more aggressive approach to end-of-life care.

When it comes to their own long-term or curative cancer care, oncologists generally don’t seem to approach treatment differently than their patients. In a 2015 study, researchers compared two groups of people with early breast cancer — 46 physicians and 230 well-educated, nonmedically qualified patients — and found no differences in the choices the groups made about whether to undergo mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or breast reconstruction.

Still, no amount of oncology expertise can fully prepare a person for the emotional crucible of cancer.

“A very surreal experience”

Although the fear can become less intense and more manageable over time, it may never truly go away.

At first, despair dragged Flora into an abyss for 6 hours a night, then overcame him 10 times a day, then gripped him briefly at random moments. Four years later and cancer-free, the dread still returns.

Hendershott cried every time she got into her car and contemplated her prognosis. Now 47, she has about a 60% chance of being alive in 15 years, and the fear still hits her.

“I think it’s hard to understand the moments of sheer terror that you have at 2 AM when you’re confronting your own mortality,” she said. “The implications that has not just for you but more importantly for the people that you love and want to protect. That just kind of washes over you in waves that you don’t have much control over.”

Cancer, Riall felt, had smashed her life, but she figured out a way to help herself cope. Severe blood loss, chest tubes, and tests and needles ad nauseum left Riall feeling excruciatingly exhausted after her surgery and delayed her return to work. At the same time, she was passed over for a promotion. Frustrated and dejected, she took comfort in the memory of doing Kintsugi with her surgery residents. The Japanese art form involves shattering pottery with a hammer, fitting the fragments back together, and painting the cracks gold.

“My instinct as a surgeon is to pick up those pieces and put them back together so nobody sees it’s broken,” she reflected. But as a patient, she learned that an important part of recovery is to allow yourself to sit in a broken state and feel angry, miserable, and betrayed by your body. And then examine your shattered priorities and consider how you want to reassemble them.

For Barbara Buttin, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at Cancer Treatment Centers of America, in Chicago, Illinois, it wasn’t cancer that almost took her life. Rather, a near-death experience and life-threatening diagnosis made her a better, more empathetic cancer doctor — a refrain echoed by many oncologist-patients. Confronting her own mortality crystallized what matters in life. She uses that understanding to make sure she understands what matters to her patients ― what they care about most, what their greatest fear is, what is going to keep them up at night.

“We’re part of the same club”

Ultimately, when oncology practitioners become patients, it balances the in-control and vulnerable, the rational and emotional. And their patients respond positively.

In fall 2020, oncology nurse Jenn Adams, RN, turned 40 and underwent her first mammogram. Unexpectedly, it revealed invasive stage I cancer that would require a double mastectomy, chemotherapy, and a year of immunotherapy. A week after her diagnosis, she was scheduled to start a new job at Cancer Clinic, in Bryan, Tex. So, she asked her manager if she could become a patient and an employee.

Ms. Adams worked 5 days a week, but every Thursday at 2 PM, she sat next to her patients while her coworkers became her nurses. Her chemo port was implanted, she lost her hair, and she felt terrible along with her patients. “It just created this incredible bond,” said the mother of three.

Having cancer, Dr. Flora said, “was completely different than I had imagined. When I thought I was walking with [my patients] in the depths of their caves, I wasn’t even visiting their caves.” But, he added, it has also “let me connect with [patients] on a deeper level because we’re part of the same club. You can see their body language change when I share that. They almost relax, like, ‘Oh, this guy gets it. He does understand how terrified I am.’ And I do.”

When Dr. Flora’s patients are scanned, he gives them their results immediately, because he knows what it’s like to wait on tenterhooks. He tells his patients to text him anytime they’re afraid or depressed, which he admits isn’t great for his own mental health but believes is worth it.

Likewise, Dr. Hendershott can hold out her shoulder-length locks to reassure a crying patient that hair does grow back after chemo. She can describe her experience with hormone-blocking pills to allay the fears of a pharmaceutical skeptic.

This role equalizer fosters so much empathy that doctors sometimes find themselves being helped by their patients. When one of Dr. Flora’s patients heard he had cancer, she sent him an email that began. “A wise doctor once told me....” and repeated the advice he’d given her years before.

Dr. Lewis has a special bond with his patients because people who have pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors seek him out for treatment. “I’m getting to take care of people who, on some level, are like my kindred spirits,” he said. “So, I get to see their coping mechanisms and how they do.”

Ms. Edwards told some of her patients about her breast cancer diagnosis, and now they give each other high-fives and share words of encouragement. “I made it a big thing of mine to associate my patients as my family,” she said. “If you’ve learned to embrace love and love people, there’s nothing you wouldn’t do for people. I’ve chosen that to be my practice when I’m dealing with all of my patients.”

Ms. Adams is on a similar mission. She joined a group of moms with cancer so she can receive guidance and then become a guide for others. “I feel like that’s what I want to be at my cancer practice,” she said, “so [my patients] have someone to say, ‘I’m gonna walk alongside you because I’ve been there.’ “

That transformation has made all the heartbreaking moments worth it, Ms. Adams said. “I love the oncology nurse that I get to be now because of my diagnosis. I don’t love the diagnosis. But I love the way it’s changed what I do.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tiny insects reveal some big secrets in cancer

Uncontrolled growth isn’t the only way cancers wreak havoc on the human body. These aggregations of freely dividing cells also release chemicals that can cause damage from a distance. But pinning down how they harm faraway healthy tissues isn’t straightforward.

Fortunately, biologists can turn to the tiny fruit fly to address some of these questions: This insect’s body is not as complex as ours in many ways, but we share important genes and organ functions.

Fruit flies already are a crucial and inexpensive animal for genetics research. Because their life span is about 7 weeks, investigators can track the effects of mutations across several generations in a short period. The animals also are proving useful for learning how chemicals released by malignant tumors can harm tissues in the body that are not near the cancer.

One recent lesson from the fruit flies involves the blood-brain barrier, which determines which molecules gain access to the brain. Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, have found that malignant tumors in the tiny insects release interleukin 6 (IL-6), an inflammatory chemical that disrupts this important barrier. The investigators showed that the tumors act similarly in mice.

Even if cancer cells persisted, damage related to IL-6 could be diminished.

Fruit flies and mice are only distant relatives of each other and of humans, and the relevance of this discovery to human cancers has not been established. One hurdle is that IL-6 has many important, normal functions related to health. Researchers need to learn how to target only its unwanted blood-brain barrier effects.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Uncontrolled growth isn’t the only way cancers wreak havoc on the human body. These aggregations of freely dividing cells also release chemicals that can cause damage from a distance. But pinning down how they harm faraway healthy tissues isn’t straightforward.

Fortunately, biologists can turn to the tiny fruit fly to address some of these questions: This insect’s body is not as complex as ours in many ways, but we share important genes and organ functions.

Fruit flies already are a crucial and inexpensive animal for genetics research. Because their life span is about 7 weeks, investigators can track the effects of mutations across several generations in a short period. The animals also are proving useful for learning how chemicals released by malignant tumors can harm tissues in the body that are not near the cancer.

One recent lesson from the fruit flies involves the blood-brain barrier, which determines which molecules gain access to the brain. Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, have found that malignant tumors in the tiny insects release interleukin 6 (IL-6), an inflammatory chemical that disrupts this important barrier. The investigators showed that the tumors act similarly in mice.

Even if cancer cells persisted, damage related to IL-6 could be diminished.

Fruit flies and mice are only distant relatives of each other and of humans, and the relevance of this discovery to human cancers has not been established. One hurdle is that IL-6 has many important, normal functions related to health. Researchers need to learn how to target only its unwanted blood-brain barrier effects.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Uncontrolled growth isn’t the only way cancers wreak havoc on the human body. These aggregations of freely dividing cells also release chemicals that can cause damage from a distance. But pinning down how they harm faraway healthy tissues isn’t straightforward.

Fortunately, biologists can turn to the tiny fruit fly to address some of these questions: This insect’s body is not as complex as ours in many ways, but we share important genes and organ functions.

Fruit flies already are a crucial and inexpensive animal for genetics research. Because their life span is about 7 weeks, investigators can track the effects of mutations across several generations in a short period. The animals also are proving useful for learning how chemicals released by malignant tumors can harm tissues in the body that are not near the cancer.

One recent lesson from the fruit flies involves the blood-brain barrier, which determines which molecules gain access to the brain. Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, have found that malignant tumors in the tiny insects release interleukin 6 (IL-6), an inflammatory chemical that disrupts this important barrier. The investigators showed that the tumors act similarly in mice.

Even if cancer cells persisted, damage related to IL-6 could be diminished.

Fruit flies and mice are only distant relatives of each other and of humans, and the relevance of this discovery to human cancers has not been established. One hurdle is that IL-6 has many important, normal functions related to health. Researchers need to learn how to target only its unwanted blood-brain barrier effects.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ulcer on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Calcinosis Cutis Due to Systemic Sclerosis Sine Scleroderma

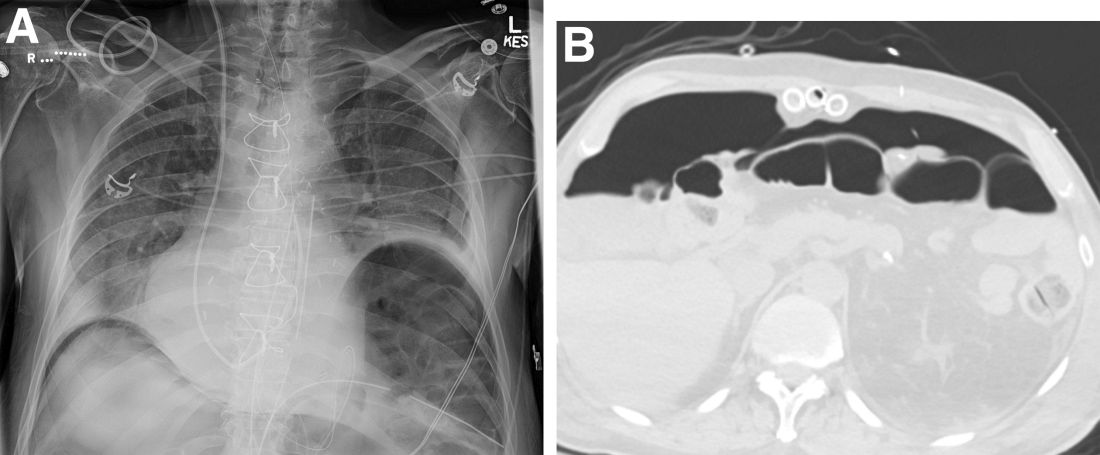

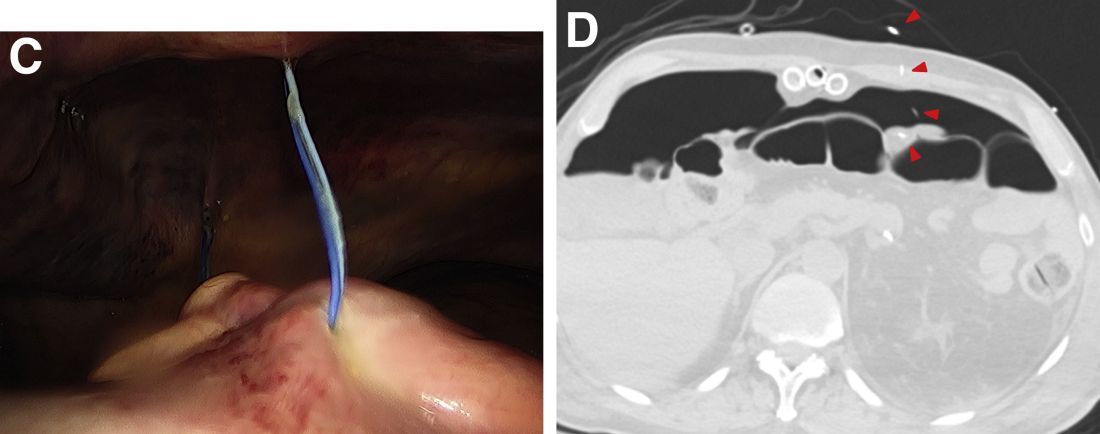

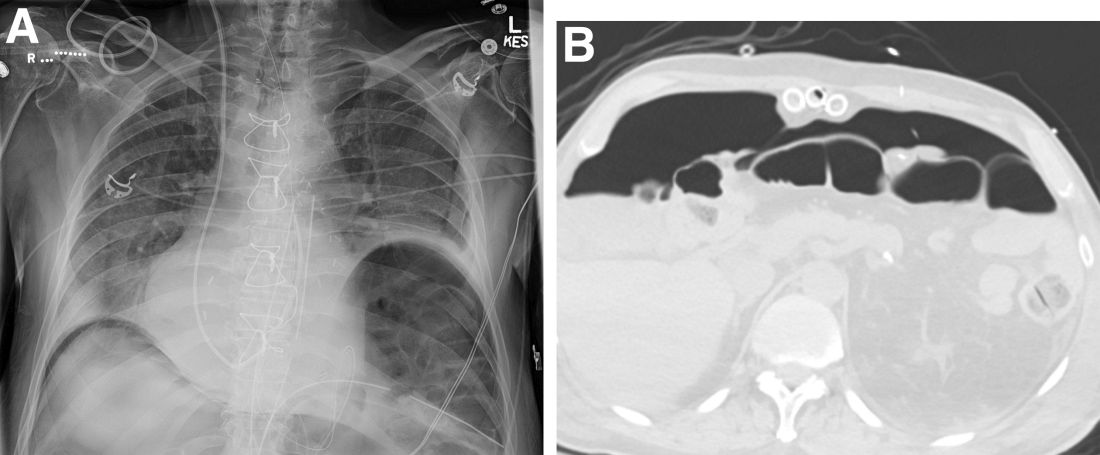

Laboratory evaluation was notable for high titers of antinuclear antibodies (>1/320; reference range, 0–1/80) and positive anticentromere antibodies. There were no other relevant laboratory findings; phosphocalcic metabolism was within normal limits, and urinary sediment was normal. Biopsy of the edge of the ulcer revealed basophilic material compatible with calcium deposits. In a 3D volume rendering reconstruction from the lower limb scanner, grouped calcifications were observed in subcutaneous cellular tissue near the ulcer (Figure). The patient had a restrictive ventilatory pattern observed in a pulmonary function test. An esophageal motility study was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) type II because she met the 4 criteria established by Poormoghim et al1 : (1) Raynaud phenomenon or a peripheral vascular equivalent (ie, digital pitting scars, digital-tip ulcers, digital-tip gangrene, abnormal nail fold capillaries); (2) positive antinuclear antibodies; (3) distal esophageal hypomotility, small bowel hypomotility, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, primary pulmonary arterial hypertension (without fibrosis), cardiac involvement typical of scleroderma, or renal failure; and (4) no other defined connective tissue or other disease as a cause of the prior conditions.

Systemic sclerosis is a chronic disease characterized by progressive fibrosis of the skin and other internal organs—especially the lungs, kidneys, digestive tract, and heart—as well as generalized vascular dysfunction. Cutaneous induration is its hallmark; however, up to 10% of affected patients have ssSSc.2 This entity is characterized by the total or partial absence of cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis with the occurrence of internal organ involvement and serologic abnormalities. There are 3 types of ssSSc depending on the grade of skin involvement. Type I is characterized by the lack of any typical cutaneous stigmata of the disease. Type II is without sclerodactyly but can coexist with other cutaneous findings such as calcifications, telangiectases, or pitting scars. Type III is characterized clinically by internal organ involvement, typical of systemic sclerosis, that has appeared before skin changes.2

An abnormal deposit of calcium in the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue is called calcinosis cutis. There are 5 subtypes of calcinosis cutis: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, iatrogenic, and calciphylaxis. Dystrophic skin calcifications may appear in patients with connective tissue diseases such as dermatomyositis or systemic sclerosis.3 Up to 25% of patients with systemic sclerosis can develop calcinosis cutis due to local tissue damage, with normal phosphocalcic metabolism.3

Calcinosis cutis is more common in patients with systemic sclerosis and positive anticentromere antibodies.4 The calcifications usually are located in areas that are subject to repeated trauma, such as the fingers or arms, though other locations have been described such as cervical, paraspinal, or on the hips.5,6 Our patient developed calcifications on both legs, which represent atypical areas for this process.

Dermatomyositis also can present with calcinosis cutis. There are 4 patterns of calcification: superficial nodulelike calcified masses; deep calcified masses; deep sheetlike calcifications within the fascial planes; and a rare, diffuse, superficial lacy and reticular calcification that involves almost the entire body surface area.7 Patients with calcinosis cutis secondary to dermatomyositis usually develop proximal muscle weakness, high titers of creatine kinase, heliotrope rash, or interstitial lung disease with specific antibodies.

Calciphylaxis is a serious disorder involving the calcification of dermal and subcutaneous arterioles and capillaries. It presents with painful cutaneous areas of necrosis.

Venous ulcers also can present with secondary dystrophic calcification due to local tissue damage. These patients usually have cutaneous signs of chronic venous insufficiency. Our patient denied prior trauma to the area; therefore, a traumatic ulcer with secondary calcification was ruled out.

The most concerning complication of calcinosis cutis is the development of ulcers, which occurred in 154 of 316 calcinoses (48.7%) in patients with systemic sclerosis and secondary calcifications.8 These ulcers can cause disabling pain or become superinfected, as in our patient.

There currently is no drug capable of removing dystrophic calcifications, but diltiazem, minocycline, or colchicine can reduce their size and prevent their progression. In the event of neurologic compromise or intractable pain, the treatment of choice is surgical removal of the calcification.9 Curettage, intralesional sodium thiosulfate, and intravenous sodium thiosulfate also have been suggested as therapeutic options.10 Antibiotic treatment was carried out in our patient, which controlled the superinfection of the ulcers. Diltiazem also was started, with stabilization of the calcium deposits without a reduction in their size.

There are few studies evaluating the presence of nondigital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Shanmugam et al11 calculated a 4% (N=249) prevalence of ulcers in the lower limbs of systemic sclerosis patients. In a study by Bohelay et al12 of 45 patients, the estimated prevalence of lower limb ulcers was 12.8%, and the etiologies consisted of 22 cases of venous insufficiency (49%), 21 cases of ischemic causes (47%), and 2 cases of other causes (4%).

We present the case of a woman with ssSSc who developed dystrophic calcinosis cutis in atypical areas with secondary ulceration and superinfection. The skin usually plays a key role in the diagnosis of systemic sclerosis, as sclerodactyly and the characteristic generalized skin induration stand out in affected individuals. Although our patient was diagnosed with ssSSc, her skin manifestations also were crucial for the diagnosis, as she had ulcers on the lower limbs.

- Poormoghim H, Lucas M, Fertig N, et al. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in forty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:444-451.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛ drek M. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:875-880.

- Valenzuela A, Baron M, Herrick AL, et al. Calcinosis is associated with digital ulcers and osteoporosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: a scleroderma clinical trials consortium study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:344-349.

- D’Aoust J, Hudson M, Tatibouet S, et al. Clinical and serologic correlates of antiPM/Scl antibodies in systemic sclerosis: a multicenter study of 763 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:1608-1615.

- Contreras I, Sallés M, Mínguez S, et al. Hard paracervical tumor in a patient with limited systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Clin. 2014; 10:336-337.

- Meriglier E, Lafourcade F, Gombert B, et al. Giant calcinosis revealing systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:1787-1788.

- Chung CH. Calcinosis universalis in juvenile dermatomyositis [published online September 24, 2020]. Chonnam Med J. 2020;56:212-213.

- Bartoli F, Fiori G, Braschi F, et al. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis: subsets, distribution and complications [published online May 30, 2016]. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1610-1614.

- Jung H, Lee D, Cho J, et al. Surgical treatment of extensive tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;48:151-154.

- Badawi AH, Patel V, Warner AE, et al. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis: treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Cutis. 2020;106:E15-E17.

- Shanmugam V, Price P, Attinger C, et al. Lower extremity ulcers in systemic sclerosis: features and response to therapy [published online August 18, 2010]. Int J Rheumatol. doi:10.1155/2010/747946

- Bohelay G, Blaise S, Levy P, et al. Lower-limb ulcers in systemic sclerosis: a multicentre retrospective case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:677-682.

The Diagnosis: Calcinosis Cutis Due to Systemic Sclerosis Sine Scleroderma

Laboratory evaluation was notable for high titers of antinuclear antibodies (>1/320; reference range, 0–1/80) and positive anticentromere antibodies. There were no other relevant laboratory findings; phosphocalcic metabolism was within normal limits, and urinary sediment was normal. Biopsy of the edge of the ulcer revealed basophilic material compatible with calcium deposits. In a 3D volume rendering reconstruction from the lower limb scanner, grouped calcifications were observed in subcutaneous cellular tissue near the ulcer (Figure). The patient had a restrictive ventilatory pattern observed in a pulmonary function test. An esophageal motility study was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) type II because she met the 4 criteria established by Poormoghim et al1 : (1) Raynaud phenomenon or a peripheral vascular equivalent (ie, digital pitting scars, digital-tip ulcers, digital-tip gangrene, abnormal nail fold capillaries); (2) positive antinuclear antibodies; (3) distal esophageal hypomotility, small bowel hypomotility, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, primary pulmonary arterial hypertension (without fibrosis), cardiac involvement typical of scleroderma, or renal failure; and (4) no other defined connective tissue or other disease as a cause of the prior conditions.

Systemic sclerosis is a chronic disease characterized by progressive fibrosis of the skin and other internal organs—especially the lungs, kidneys, digestive tract, and heart—as well as generalized vascular dysfunction. Cutaneous induration is its hallmark; however, up to 10% of affected patients have ssSSc.2 This entity is characterized by the total or partial absence of cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis with the occurrence of internal organ involvement and serologic abnormalities. There are 3 types of ssSSc depending on the grade of skin involvement. Type I is characterized by the lack of any typical cutaneous stigmata of the disease. Type II is without sclerodactyly but can coexist with other cutaneous findings such as calcifications, telangiectases, or pitting scars. Type III is characterized clinically by internal organ involvement, typical of systemic sclerosis, that has appeared before skin changes.2

An abnormal deposit of calcium in the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue is called calcinosis cutis. There are 5 subtypes of calcinosis cutis: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, iatrogenic, and calciphylaxis. Dystrophic skin calcifications may appear in patients with connective tissue diseases such as dermatomyositis or systemic sclerosis.3 Up to 25% of patients with systemic sclerosis can develop calcinosis cutis due to local tissue damage, with normal phosphocalcic metabolism.3

Calcinosis cutis is more common in patients with systemic sclerosis and positive anticentromere antibodies.4 The calcifications usually are located in areas that are subject to repeated trauma, such as the fingers or arms, though other locations have been described such as cervical, paraspinal, or on the hips.5,6 Our patient developed calcifications on both legs, which represent atypical areas for this process.

Dermatomyositis also can present with calcinosis cutis. There are 4 patterns of calcification: superficial nodulelike calcified masses; deep calcified masses; deep sheetlike calcifications within the fascial planes; and a rare, diffuse, superficial lacy and reticular calcification that involves almost the entire body surface area.7 Patients with calcinosis cutis secondary to dermatomyositis usually develop proximal muscle weakness, high titers of creatine kinase, heliotrope rash, or interstitial lung disease with specific antibodies.

Calciphylaxis is a serious disorder involving the calcification of dermal and subcutaneous arterioles and capillaries. It presents with painful cutaneous areas of necrosis.

Venous ulcers also can present with secondary dystrophic calcification due to local tissue damage. These patients usually have cutaneous signs of chronic venous insufficiency. Our patient denied prior trauma to the area; therefore, a traumatic ulcer with secondary calcification was ruled out.

The most concerning complication of calcinosis cutis is the development of ulcers, which occurred in 154 of 316 calcinoses (48.7%) in patients with systemic sclerosis and secondary calcifications.8 These ulcers can cause disabling pain or become superinfected, as in our patient.

There currently is no drug capable of removing dystrophic calcifications, but diltiazem, minocycline, or colchicine can reduce their size and prevent their progression. In the event of neurologic compromise or intractable pain, the treatment of choice is surgical removal of the calcification.9 Curettage, intralesional sodium thiosulfate, and intravenous sodium thiosulfate also have been suggested as therapeutic options.10 Antibiotic treatment was carried out in our patient, which controlled the superinfection of the ulcers. Diltiazem also was started, with stabilization of the calcium deposits without a reduction in their size.

There are few studies evaluating the presence of nondigital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Shanmugam et al11 calculated a 4% (N=249) prevalence of ulcers in the lower limbs of systemic sclerosis patients. In a study by Bohelay et al12 of 45 patients, the estimated prevalence of lower limb ulcers was 12.8%, and the etiologies consisted of 22 cases of venous insufficiency (49%), 21 cases of ischemic causes (47%), and 2 cases of other causes (4%).

We present the case of a woman with ssSSc who developed dystrophic calcinosis cutis in atypical areas with secondary ulceration and superinfection. The skin usually plays a key role in the diagnosis of systemic sclerosis, as sclerodactyly and the characteristic generalized skin induration stand out in affected individuals. Although our patient was diagnosed with ssSSc, her skin manifestations also were crucial for the diagnosis, as she had ulcers on the lower limbs.

The Diagnosis: Calcinosis Cutis Due to Systemic Sclerosis Sine Scleroderma

Laboratory evaluation was notable for high titers of antinuclear antibodies (>1/320; reference range, 0–1/80) and positive anticentromere antibodies. There were no other relevant laboratory findings; phosphocalcic metabolism was within normal limits, and urinary sediment was normal. Biopsy of the edge of the ulcer revealed basophilic material compatible with calcium deposits. In a 3D volume rendering reconstruction from the lower limb scanner, grouped calcifications were observed in subcutaneous cellular tissue near the ulcer (Figure). The patient had a restrictive ventilatory pattern observed in a pulmonary function test. An esophageal motility study was normal.

The patient was diagnosed with systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma (ssSSc) type II because she met the 4 criteria established by Poormoghim et al1 : (1) Raynaud phenomenon or a peripheral vascular equivalent (ie, digital pitting scars, digital-tip ulcers, digital-tip gangrene, abnormal nail fold capillaries); (2) positive antinuclear antibodies; (3) distal esophageal hypomotility, small bowel hypomotility, pulmonary interstitial fibrosis, primary pulmonary arterial hypertension (without fibrosis), cardiac involvement typical of scleroderma, or renal failure; and (4) no other defined connective tissue or other disease as a cause of the prior conditions.

Systemic sclerosis is a chronic disease characterized by progressive fibrosis of the skin and other internal organs—especially the lungs, kidneys, digestive tract, and heart—as well as generalized vascular dysfunction. Cutaneous induration is its hallmark; however, up to 10% of affected patients have ssSSc.2 This entity is characterized by the total or partial absence of cutaneous manifestations of systemic sclerosis with the occurrence of internal organ involvement and serologic abnormalities. There are 3 types of ssSSc depending on the grade of skin involvement. Type I is characterized by the lack of any typical cutaneous stigmata of the disease. Type II is without sclerodactyly but can coexist with other cutaneous findings such as calcifications, telangiectases, or pitting scars. Type III is characterized clinically by internal organ involvement, typical of systemic sclerosis, that has appeared before skin changes.2

An abnormal deposit of calcium in the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue is called calcinosis cutis. There are 5 subtypes of calcinosis cutis: dystrophic, metastatic, idiopathic, iatrogenic, and calciphylaxis. Dystrophic skin calcifications may appear in patients with connective tissue diseases such as dermatomyositis or systemic sclerosis.3 Up to 25% of patients with systemic sclerosis can develop calcinosis cutis due to local tissue damage, with normal phosphocalcic metabolism.3

Calcinosis cutis is more common in patients with systemic sclerosis and positive anticentromere antibodies.4 The calcifications usually are located in areas that are subject to repeated trauma, such as the fingers or arms, though other locations have been described such as cervical, paraspinal, or on the hips.5,6 Our patient developed calcifications on both legs, which represent atypical areas for this process.

Dermatomyositis also can present with calcinosis cutis. There are 4 patterns of calcification: superficial nodulelike calcified masses; deep calcified masses; deep sheetlike calcifications within the fascial planes; and a rare, diffuse, superficial lacy and reticular calcification that involves almost the entire body surface area.7 Patients with calcinosis cutis secondary to dermatomyositis usually develop proximal muscle weakness, high titers of creatine kinase, heliotrope rash, or interstitial lung disease with specific antibodies.

Calciphylaxis is a serious disorder involving the calcification of dermal and subcutaneous arterioles and capillaries. It presents with painful cutaneous areas of necrosis.

Venous ulcers also can present with secondary dystrophic calcification due to local tissue damage. These patients usually have cutaneous signs of chronic venous insufficiency. Our patient denied prior trauma to the area; therefore, a traumatic ulcer with secondary calcification was ruled out.

The most concerning complication of calcinosis cutis is the development of ulcers, which occurred in 154 of 316 calcinoses (48.7%) in patients with systemic sclerosis and secondary calcifications.8 These ulcers can cause disabling pain or become superinfected, as in our patient.

There currently is no drug capable of removing dystrophic calcifications, but diltiazem, minocycline, or colchicine can reduce their size and prevent their progression. In the event of neurologic compromise or intractable pain, the treatment of choice is surgical removal of the calcification.9 Curettage, intralesional sodium thiosulfate, and intravenous sodium thiosulfate also have been suggested as therapeutic options.10 Antibiotic treatment was carried out in our patient, which controlled the superinfection of the ulcers. Diltiazem also was started, with stabilization of the calcium deposits without a reduction in their size.

There are few studies evaluating the presence of nondigital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. Shanmugam et al11 calculated a 4% (N=249) prevalence of ulcers in the lower limbs of systemic sclerosis patients. In a study by Bohelay et al12 of 45 patients, the estimated prevalence of lower limb ulcers was 12.8%, and the etiologies consisted of 22 cases of venous insufficiency (49%), 21 cases of ischemic causes (47%), and 2 cases of other causes (4%).

We present the case of a woman with ssSSc who developed dystrophic calcinosis cutis in atypical areas with secondary ulceration and superinfection. The skin usually plays a key role in the diagnosis of systemic sclerosis, as sclerodactyly and the characteristic generalized skin induration stand out in affected individuals. Although our patient was diagnosed with ssSSc, her skin manifestations also were crucial for the diagnosis, as she had ulcers on the lower limbs.

- Poormoghim H, Lucas M, Fertig N, et al. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in forty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:444-451.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛ drek M. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:875-880.

- Valenzuela A, Baron M, Herrick AL, et al. Calcinosis is associated with digital ulcers and osteoporosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: a scleroderma clinical trials consortium study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:344-349.

- D’Aoust J, Hudson M, Tatibouet S, et al. Clinical and serologic correlates of antiPM/Scl antibodies in systemic sclerosis: a multicenter study of 763 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:1608-1615.

- Contreras I, Sallés M, Mínguez S, et al. Hard paracervical tumor in a patient with limited systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Clin. 2014; 10:336-337.

- Meriglier E, Lafourcade F, Gombert B, et al. Giant calcinosis revealing systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:1787-1788.

- Chung CH. Calcinosis universalis in juvenile dermatomyositis [published online September 24, 2020]. Chonnam Med J. 2020;56:212-213.

- Bartoli F, Fiori G, Braschi F, et al. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis: subsets, distribution and complications [published online May 30, 2016]. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1610-1614.

- Jung H, Lee D, Cho J, et al. Surgical treatment of extensive tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;48:151-154.

- Badawi AH, Patel V, Warner AE, et al. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis: treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Cutis. 2020;106:E15-E17.

- Shanmugam V, Price P, Attinger C, et al. Lower extremity ulcers in systemic sclerosis: features and response to therapy [published online August 18, 2010]. Int J Rheumatol. doi:10.1155/2010/747946

- Bohelay G, Blaise S, Levy P, et al. Lower-limb ulcers in systemic sclerosis: a multicentre retrospective case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:677-682.

- Poormoghim H, Lucas M, Fertig N, et al. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in forty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:444-451.

- Kucharz EJ, Kopec´-Me˛ drek M. Systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:875-880.

- Valenzuela A, Baron M, Herrick AL, et al. Calcinosis is associated with digital ulcers and osteoporosis in patients with systemic sclerosis: a scleroderma clinical trials consortium study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:344-349.

- D’Aoust J, Hudson M, Tatibouet S, et al. Clinical and serologic correlates of antiPM/Scl antibodies in systemic sclerosis: a multicenter study of 763 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66:1608-1615.

- Contreras I, Sallés M, Mínguez S, et al. Hard paracervical tumor in a patient with limited systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Clin. 2014; 10:336-337.

- Meriglier E, Lafourcade F, Gombert B, et al. Giant calcinosis revealing systemic sclerosis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2019;22:1787-1788.

- Chung CH. Calcinosis universalis in juvenile dermatomyositis [published online September 24, 2020]. Chonnam Med J. 2020;56:212-213.

- Bartoli F, Fiori G, Braschi F, et al. Calcinosis in systemic sclerosis: subsets, distribution and complications [published online May 30, 2016]. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1610-1614.

- Jung H, Lee D, Cho J, et al. Surgical treatment of extensive tumoral calcinosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;48:151-154.

- Badawi AH, Patel V, Warner AE, et al. Dystrophic calcinosis cutis: treatment with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Cutis. 2020;106:E15-E17.

- Shanmugam V, Price P, Attinger C, et al. Lower extremity ulcers in systemic sclerosis: features and response to therapy [published online August 18, 2010]. Int J Rheumatol. doi:10.1155/2010/747946

- Bohelay G, Blaise S, Levy P, et al. Lower-limb ulcers in systemic sclerosis: a multicentre retrospective case-control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:677-682.

A 49-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, pulmonary fibrosis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension presented to our hospital with an ulcer on the left leg of unknown etiology that was superinfected by multidrug-resistant Klebsiella according to bacterial culture. She had an axillary temperature of 38.6 °C. She underwent amputation of the second and third toes on the left foot 5 years prior to presentation due to distal necrotic ulcers of ischemic origin. Physical examination revealed an 8×2-cm deep ulcer with abrupt edges on the left leg with fibrin and a purulent exudate. Deep palpation of the perilesional skin revealed indurated subcutaneous nodules. She also had scars on the fingertips of both hands with no induration on the rest of the skin surface. Capillaroscopy showed no pathologic findings. Blood cultures were performed, and she was admitted to the hospital for intravenous antibiotic therapy. During ulcer debridement, some solid whitish material was released.

Rural hospitalists confront COVID-19

Unique demands of patient care in small hospitals

In 2018, Atashi Mandal, MD, a hospitalist residing in Orange County, Calif., was recruited along with several other doctors to fill hospitalist positions in rural Bishop, Calif. She has since driven 600 miles round trip every month for a week of hospital medicine shifts at Northern Inyo Hospital.

Dr. Mandal said she has really enjoyed her time at the small rural hospital and found it professionally fulfilling to participate so fully in the health of its local community. She was building personal bonds and calling the experience the pinnacle of her career when the COVID-19 pandemic swept across America and the world, even reaching up into Bishop, population 3,760, in the isolated Owens Valley.

The 25-bed hospital has seen at least 100 COVID patients in the past year and some months. Responsibility for taking care of these patients has been both humbling and gratifying, Dr. Mandal said. The facility’s hospitalists made a commitment to keep working through the pandemic. “We were able to come together (around COVID) as a team and our teamwork really made a difference,” she said.

“One of the advantages in a smaller hospital is you can have greater cohesiveness and your communication can be tighter. That played a big role in how we were able to accomplish so much with fewer resources as a rural hospital.” But staffing shortages, recruitment, and retention remain a perennial challenge for rural hospitals. “And COVID only exacerbated the problems,” she said. “I’ve had my challenges trying to make proper treatment plans without access to specialists.”

It was also difficult to witness so many patients severely ill or dying from COVID, Dr. Mandal said, especially since patients were not allowed family visitors – even though that was for a good reason, to minimize the virus’s spread.

HM in rural communities

Hospital medicine continues to extend into rural communities and small rural hospitals. In 2018, 35.7% of all rural counties in America had hospitals staffed with hospitalists, and 63.3% of rural hospitals had hospitalist programs (compared with 79.2% of urban hospitals). These numbers come from Medicare resources files from the Department of Health & Human Services, analyzed by Peiyin Hung, PhD, assistant professor of health services management and policy at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.1 Hospitalist penetration rates rose steadily from 2011 to 2017, with a slight dip in 2018, Dr. Hung said in an interview.

A total of 138 rural hospitals have closed since 2010, according to the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research in Chapel Hill, N.C. Nineteen rural hospitals closed in 2020 alone, although many of those were caused by factors predating the pandemic. Only one has closed so far in 2021. But financial pressures, including low patient volumes and loss of revenue from canceled routine services like elective surgeries during the pandemic, have added to hospitals’ difficulties. Pandemic relief funding may have helped some hospitals stay open, but that support eventually will go away.

Experts emphasize the diversity of rural America and its health care systems. Rural economies are volatile and more diverse than is often appreciated. The hospital may be a cornerstone of the local economy; when one closes, it can devastate the community. Workforce is one of the chief components of a hospital’s ability to meet its strategic vision, and hospitalists are a big part in that. But while hospitalists are valued and appreciated, if the hospital is suffering severe financial problems, that will impact its doctors’ jobs and livelihoods.

“Bandwidth” varies widely for rural hospitalists and their hospitalist groups, said Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, executive chair of SHM’s Rural Special Interest Group and founder and principal of KGS Consultants, a Hospital Medicine and Primary Care Practice Management Consulting company. They may face scarce resources, scarce clinical staffing, lack of support staff to help operations run smoothly, lack of access to specialists locally, and lack of technology. While practicing in a rural setting presents various challenges, it can be rewarding for those clinicians who embrace its autonomy and broad scope of services, Dr. Simone said.

SHM’s Rural SIG focuses on the unique needs of rural hospitalists, providing them with an opportunity to share their concerns, challenges and solutions through roundtable discussions every other month and a special interest forum held in conjunction with the SHM Converge annual conference, Dr. Simone said. (The next SHM Converge will be April 7-10, 2022, in Nashville, Tenn.) The Rural SIG also collaborates with other hospital medicine SIGs and committees and is working on a white paper, “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Rural Hospital Medicine Group.” It is also looking to develop a rural mentorship exchange program.

COVID reaches rural America

Early COVID caseloads tended to be in urban areas, but subsequent surges of infections have spread to many rural areas. Some rural settings became epicenters for the pandemic in November and December 2020. More recent troubling rises in COVID cases, particularly in areas with lower vaccination rates – suggest that the challenges of the pandemic are still not behind us.

“By no means is the crisis done in rural America,” said Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association, in a Virtual Rural Health Journalism workshop on rural health care sponsored by the Association of Health Care Journalists.2

Mr. Morgan’s colleague, Brock Slabach, NRHA’s chief operations officer, said in an interview that, while 453 of the 1,800 hospitals in rural areas fit NRHA’s criteria as being vulnerable to closure, the rest are not, and are fulfilling their missions for their communities. Hospitalists are becoming more common in these hospitals, he said, and rural hospitalists can be an important asset in attracting primary care physicians – who might not appreciate being perpetually on call for their hospitalized patients – to rural communities.

In many cases, traveling doctors like Dr. Mandal or telemedicine backup, particularly for after-hours coverage or ICU beds, are important pieces of the puzzle for smaller hospitals. There are different ways to use the spectrum of telemedicine services to interact with a hospital’s daytime and night routines. In some isolated locations, nurse practitioners or physician assistants provide on-the-ground coverage with virtual backup. Rural hospitals often affiliate with telemedicine networks within health systems – or else contract with independent specialized providers of telemedicine consultation.

Mr. Slabach said another alternative for staffing hospitals with smaller ED and inpatient volumes is to have one doctor on duty who can cover both departments simultaneously. Meanwhile, the new federal Rural Emergency Hospital Program proposes to allow rural hospitals to become essentially freestanding EDs – starting Jan. 1, 2023 – that can manage patients for a maximum of 24 hours.3

Community connections and proactive staffing

Lisa Kaufmann, MD, works as a hospitalist for a two-hospital system in North Carolina, Appalachian Regional Health Care. She practices at Watauga Medical Center, with 100 licensed beds in Boone, and at Cannon Memorial Hospital, a critical access hospital in unincorporated Linville. “We are proud of what we have been able to accomplish during the pandemic,” she said.

A former critical care unit at Watauga had been shut down, but its wiring remained intact. “We turned it into a COVID unit in three days. Then we opened another COVID unit with 18 beds, but that still wasn’t enough. We converted half of our med/surg capacity into a COVID unit. At one point almost half of all of our acute beds were for COVID patients. We made plans for what we would do if it got worse, since we had almost run out of beds,” she said. Demand peaked at the end of January 2021.

“The biggest barrier for us was if someone needed to be transferred, for example, if they needed ECMO [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation], and we couldn’t find another hospital to provide that technology.” In ARHC’s mountainous region – known as the “High Country” – weather can also make it difficult to transport patients. “Sometimes the ambulance can’t make it off the mountain, and half of the time the medical helicopter can’t fly. So we have to be prepared to keep people who we might think ought to be transferred,” she said.

Like many rural communities, the High Country is tightly knit, and its hospitals are really connected to their communities, Dr. Kaufmann said. The health system already had a lot of community connections beyond acute care, and that meant the pandemic wasn’t experienced as severely as it was in some other rural communities. “But without hospitalists in our hospitals, it would have been much more difficult.”

Proactive supply fulfillment meant that her hospitals never ran out of personal protective equipment. “Staffing was a challenge, but we were proactive in getting traveling doctors to come here. We also utilized extra doctors from the local community,” she said. Another key was well-established disaster planning, with regular drills, and a robust incident command structure, which just needed to be activated in the crisis. “Small hospitals need to be prepared for disaster,” Dr. Kaufmann said.

For Dale Wiersma, MD, a hospitalist with Spectrum Health, a 14-hospital system in western Michigan, telemedicine services are coordinated across 8 rural regional hospitals. “We don’t tend to use it for direct hospitalist work during daytime hours, unless a facility is swamped, in which case we can cross-cover. We do more telemedicine at night. But during daytime hours we have access to stroke neurology, cardiology, psychiatry, critical care and infectious disease specialists who are able to offer virtual consults,” Dr. Wiersma said. A virtual critical care team of doctor and nurse is often the only intensivist service covering Spectrum’s rural hospitals.

“In our system, the pandemic accelerated the adoption of telemedicine,” Dr. Wiersma said. “We had been working on the tele-ICU program, trying to get it rolled out. When the pandemic hit, we launched it in just 6 weeks.”