User login

For MD-IQ use only

COVID-19 and Venous Thromboembolism Pharmacologic Thromboprophylaxis

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and resulting viral syndrome (COVID-19) was first reported in China during December 2019 and within weeks emerged in the US.1 Since it is a rapidly evolving situation, clinicians must remain current on best practices—a challenging institutional responsibility. According to LitCovid, a curated literature hub for tracking scientific information on COVID-19, there are > 54,000 articles on the subject in PubMed. Among these include venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis guidance from 4 respected thrombosis organizations/societies and the US National Institutes of Health.1-5

Observations

COVID-19 predisposes patients with and without a history of cardiovascular disease to thrombotic complications, occurring in either the venous or arterial circulation system.2,6 Early observational studies suggest that thrombotic rates may be in excess of 20 to 30%; however, the use of prophylactic anticoagulation was inconsistent among studies that were rushed to publication.6

Autopsy data have demonstrated the presence of fibrin thrombi within distended small vessels and capillaries and extensive extracellular fibrin deposition.6 Investigators compared the characteristics of acute pulmonary embolism in 23 cases with COVID-19 but with no clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis with 100 controls without COVID-19.7 They observed that thrombotic lesions had a greater distribution in peripheral lung segments (ie, peripheral arteries) and were less extensive for those with COVID-19 vs without COVID-19 infection. Thus, experts currently hypothesize that COVID-19 has a distinct “pathomechanism.” As a unique phenotype, thrombotic events represent a combination of thromboembolic disease influenced by components of the Virchow triad (eg, acute illness and immobility) and in situ immunothrombosis, a local inflammatory response.6,7

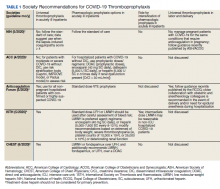

Well-established surgical and nonsurgical VTE thromboprophylaxis guidelines serve as the foundation for current COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guidance.8,9 Condition specific guidance is extrapolated from small, retrospective observational studies or based on expert opinion, representing levels 2 and 3 evidence, respectively.1-5 Table 1 captures similarities and differences among COVID-19 VTE thromboprophylaxis recommendations which vary by time to publication and by society member expertise gained from practice in the field.

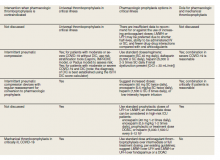

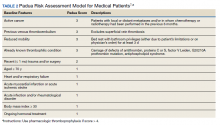

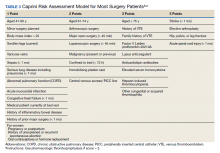

Three thrombosis societies recommend universal pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for acutely ill COVID-19 patients who lack contraindications.3-5 Others recommend use of risk stratification scoring tools, such as the Padua risk assessment model (RAM) for medical patients or Caprini RAM for surgical patients, the disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) score, or the sepsis-induced coagulopathy score to determine therapeutic appropriateness (Tables 2 and 3).1,2 Since most patients hospitalized for COVID-19 will present with a pathognomonic pneumonia and an oxygen requirement, they will generally achieve a score of ≥ 4 when the Padua RAM is applied; thus, representing a clear indication for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.8,9 If the patient is pregnant, the Anticoagulation Forum recommends pharmacologic prophylaxis, consultation with an obstetrician, and use of obstetrical thromboprophylaxis guidelines.3,10,11

Most thrombosis experts prefer parenteral thromboprophylaxis, specifically low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or fondaparinux, for inpatients over use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in order to minimize the potential for drug interactions particularly when investigational antivirals are in use.4 Once-daily agents (eg, rivaroxaban, fondaparinux, and enoxaparin) are preferred over multiple daily doses to minimize staff contact with patients infected with COVID-19.4,5 Fondaparinux and DOACs should preferentially be used in patients with a recent history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with and without thrombosis (HIT/HITTS). Subcutaneous heparin is reserved for patients who are scheduled for invasive procedures or have reduced renal function (eg, creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min).1,3-5 In line with existing pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis guidance, standard prophylactic LMWH doses are recommended unless patients are obese (body mass index [BMI] > 30) or morbidly obese (BMI > 40) necessitating selection of intermediate doses.4

Since early non-US studies demonstrated high thrombotic risk without signaling a potential for harm from pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, some organizations recommend empiric escalation of anticoagulation doses for critical illness.3,4,6 Thus, it may be reasonable to advance to either intermediate pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis dosing or therapeutic doses.3 However, observational studies question this aggressive practice unless a clear indication exists for intensification (ie, atrial fibrillation, known VTE).

A large multi-institutional registry study that included 400 subjects from 5 centers demonstrated a radiographically confirmed VTE rate of 4.8% and an arterial thrombosis rate of 2.8%.6 When limiting to the critically ill setting, VTE and arterial thrombosis occurred at slightly higher rates (7.6% and 5.6%, respectively). Patients also were at risk for nonvessel thrombotic complications (eg, CVVH circuit, central venous catheters, and arterial lines). Subsequently, the overall thrombotic complication rate was 9.5%. All thrombotic events except one arose in patients who were receiving standard doses of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. Unfortunately, D-dimer elevation at admission was not only predictive of thrombosis and death, but portended bleeding. The overall bleeding rate was 4.8%, with a major bleeding rate of 2.3%. In the context of observing thromboses at normally expected rates during critical illness in association with a significant bleeding risk, the authors recommended further investigation into the net clinical benefit.

Similarly, a National Institutes of Health funded, observational, single center US study evaluated 4,389 inpatients infected with COVID-19 and determined that therapeutic and prophylactic anticoagulation reduced inpatient mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.53 and 0.50, respectively for the primary outcome) and intubation (aHR, 0.69 and 0.72, respectively) over no anticoagulation.12 Notably, use of inpatient therapeutic anticoagulation commonly represented a continuation of preadmission therapy or progressive COVID-19. A subanalysis demonstrated that timely use (eg, within 48 hours of admission) of prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation, resulted in no difference (P < .08) in the primary outcome. Bleeding rates were low overall: 3%, 1.7%, and 1.9% for therapeutic, prophylactic, and no anticoagulation groups, respectively. Furthermore, selection of DOACs seems to be associated with lower bleeding rates when compared with that of LMWH heparin (1.3% vs 2.6%, respectively). In those where site of bleeding could be ascertained, the most common sites were the gastrointestinal tract (50.7%) followed by mucocutaneous (19.4%), bronchopulmonary (14.9%), and intracranial (6%). In summary, prophylactic thromboprophylaxis doses seem to be associated with positive net clinical benefit.

As of October 30, 2020, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) had reported 75,156 COVID-19 cases and 3,961 deaths.13 Since the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) does not disseminate nationally prepared anticoagulation order sets to the field, facility anticoagulation leads should be encouraged to develop local guidance-based policies to help standardize care and minimize further variations in practice, which would likely lack evidential support. Per the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS)- Nashville/Murfreesboro anticoagulation policy, we limit the ordering of parenteral anticoagulation to Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) order sets in order to provide decision support (eFigure 1, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0063). Other facilities have shown that embedded clinical decision support tools increase adherence to guideline VTE prophylaxis recommendations within the VA.14

In April 2020, the TVHS anticoagulation clinical pharmacy leads developed a COVID-19 specific order set based on review of societal guidance and the evolving, supportive literature summarized in this review with consideration of provider familiarity (eFigure 2, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0063)). Between April and June 2020, the COVID-19 order set content consistently evolved with publication of each COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guideline.1-5

Since TVHS is a high-complexity facility, we elected to use universal pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19. This construct bypasses the use of scoring tools (eg, RAM), although we use Padua and Caprini RAMS for medical and surgical patients, respectively, who are not diagnosed with COVID-19. The order set displays all acceptable guideline recommended options, delineated by location of care (eg, medical ward vs intensive care unit), prior history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and renal function. Subsequently, all potential agents, doses, and dosing interval options are offered so that the provider autonomously determines how to individualize the clinical care. Since TVHS has only diagnosed 932 ambulatory/inpatient COVID-19 cases combined, our plans are to complete a future observational analysis to determine the effectiveness of the inpatient COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis order set for our internal customers.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in arguably the most challenging medical climate in the evidence-based medicine era. Until high-quality randomized controlled trials are published, the medical community is, in a sense, operating within a crucible of crisis having to navigate therapeutic policy with little certainty. This principle holds true for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19 despite the numerous advancements in this field over the past decade.

A review of societal guidance shows there is universal agreement with regards to supporting standard doses of pharmacologicalprophylaxis in acutely ill patients either when universally applied or guided by a RAM as well as the use of universal thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients. All societies discourage the use of antiplatelet therapy for arterial thrombosis prevention and advocate for mechanical compression in patients with contraindications to pharmacologic anticoagulation. Beyond this, divergence between guidance statements begins to appear. For example, societies do not currently agree on the role and approach for extended pharmacologic prophylaxis postdischarge. The differences between societal guidance speaks to the degree of uncertainty among leading experts, which is considered to be the logical outworking of the current level of evidence. Regardless, these guidance documents should be considered the best resource currently available.

The medical community is fortunate to have robust societies that have published guidance on thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. The novelty of COVID-19 precludes these societal guidance publications from being based on high-quality evidence, but at the very least, they provide insight into how leading experts in the field of thrombosis and hemostasis are currently navigating the therapeutic landscape.

While this paper provides a summary of the current guidance, evidence is evolving at an unprecedented pace. Facilities and anticoagulation leads should be actively and frequently evaluating literature and guidance to ensure their practices and policies remain current.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville/Murfreesboro.

1. National Institutes of Health. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/whats-new/. Updated October 9, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

2. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950-2973. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031

3. Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):72-81. doi:10.1007/s11239-020-02138-z

4. Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: Clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1859-1865. doi:10.1111/jth.14929

5. Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, et al. Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of VTE in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2020;158(3):1143-1163. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559

6. Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489-500. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006520.

7. van Dam LF, Kroft LJM, van der Wal LI, et al. Clinical and computed tomography characteristics of COVID-19 associated acute pulmonary embolism: a different phenotype of thrombotic disease?. Thromb Res. 2020;193:86-89. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.010

8. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e195S-e226S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2296

9. Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 May;141(5):1369]. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e227S-e277S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2297

10. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196 Summary: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):243-248. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002707

11. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. Green-top Guideline. No. 37a. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-37a.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed October 15, 2020.

12. Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, et al. Anticoagulation, mortality, bleeding and pathology among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a single health system study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 24]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(16):1815-1826. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.041

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs COVID-19 national summary. https://www.accesstocare.va.gov/Healthcare/COVID19NationalSummary. Updated November 1, 2020. Accessed November 1, 2020.

14. George B, Gonzales S, Patel K, Petit S, Franck AJ, Bovio Franck J. Impact of a clinical decision-support tool on venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. J Pharm Technol. 2020;36(4):141-147. doi:10.1177/8755122520930288

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and resulting viral syndrome (COVID-19) was first reported in China during December 2019 and within weeks emerged in the US.1 Since it is a rapidly evolving situation, clinicians must remain current on best practices—a challenging institutional responsibility. According to LitCovid, a curated literature hub for tracking scientific information on COVID-19, there are > 54,000 articles on the subject in PubMed. Among these include venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis guidance from 4 respected thrombosis organizations/societies and the US National Institutes of Health.1-5

Observations

COVID-19 predisposes patients with and without a history of cardiovascular disease to thrombotic complications, occurring in either the venous or arterial circulation system.2,6 Early observational studies suggest that thrombotic rates may be in excess of 20 to 30%; however, the use of prophylactic anticoagulation was inconsistent among studies that were rushed to publication.6

Autopsy data have demonstrated the presence of fibrin thrombi within distended small vessels and capillaries and extensive extracellular fibrin deposition.6 Investigators compared the characteristics of acute pulmonary embolism in 23 cases with COVID-19 but with no clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis with 100 controls without COVID-19.7 They observed that thrombotic lesions had a greater distribution in peripheral lung segments (ie, peripheral arteries) and were less extensive for those with COVID-19 vs without COVID-19 infection. Thus, experts currently hypothesize that COVID-19 has a distinct “pathomechanism.” As a unique phenotype, thrombotic events represent a combination of thromboembolic disease influenced by components of the Virchow triad (eg, acute illness and immobility) and in situ immunothrombosis, a local inflammatory response.6,7

Well-established surgical and nonsurgical VTE thromboprophylaxis guidelines serve as the foundation for current COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guidance.8,9 Condition specific guidance is extrapolated from small, retrospective observational studies or based on expert opinion, representing levels 2 and 3 evidence, respectively.1-5 Table 1 captures similarities and differences among COVID-19 VTE thromboprophylaxis recommendations which vary by time to publication and by society member expertise gained from practice in the field.

Three thrombosis societies recommend universal pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for acutely ill COVID-19 patients who lack contraindications.3-5 Others recommend use of risk stratification scoring tools, such as the Padua risk assessment model (RAM) for medical patients or Caprini RAM for surgical patients, the disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) score, or the sepsis-induced coagulopathy score to determine therapeutic appropriateness (Tables 2 and 3).1,2 Since most patients hospitalized for COVID-19 will present with a pathognomonic pneumonia and an oxygen requirement, they will generally achieve a score of ≥ 4 when the Padua RAM is applied; thus, representing a clear indication for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.8,9 If the patient is pregnant, the Anticoagulation Forum recommends pharmacologic prophylaxis, consultation with an obstetrician, and use of obstetrical thromboprophylaxis guidelines.3,10,11

Most thrombosis experts prefer parenteral thromboprophylaxis, specifically low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or fondaparinux, for inpatients over use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in order to minimize the potential for drug interactions particularly when investigational antivirals are in use.4 Once-daily agents (eg, rivaroxaban, fondaparinux, and enoxaparin) are preferred over multiple daily doses to minimize staff contact with patients infected with COVID-19.4,5 Fondaparinux and DOACs should preferentially be used in patients with a recent history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with and without thrombosis (HIT/HITTS). Subcutaneous heparin is reserved for patients who are scheduled for invasive procedures or have reduced renal function (eg, creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min).1,3-5 In line with existing pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis guidance, standard prophylactic LMWH doses are recommended unless patients are obese (body mass index [BMI] > 30) or morbidly obese (BMI > 40) necessitating selection of intermediate doses.4

Since early non-US studies demonstrated high thrombotic risk without signaling a potential for harm from pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, some organizations recommend empiric escalation of anticoagulation doses for critical illness.3,4,6 Thus, it may be reasonable to advance to either intermediate pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis dosing or therapeutic doses.3 However, observational studies question this aggressive practice unless a clear indication exists for intensification (ie, atrial fibrillation, known VTE).

A large multi-institutional registry study that included 400 subjects from 5 centers demonstrated a radiographically confirmed VTE rate of 4.8% and an arterial thrombosis rate of 2.8%.6 When limiting to the critically ill setting, VTE and arterial thrombosis occurred at slightly higher rates (7.6% and 5.6%, respectively). Patients also were at risk for nonvessel thrombotic complications (eg, CVVH circuit, central venous catheters, and arterial lines). Subsequently, the overall thrombotic complication rate was 9.5%. All thrombotic events except one arose in patients who were receiving standard doses of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. Unfortunately, D-dimer elevation at admission was not only predictive of thrombosis and death, but portended bleeding. The overall bleeding rate was 4.8%, with a major bleeding rate of 2.3%. In the context of observing thromboses at normally expected rates during critical illness in association with a significant bleeding risk, the authors recommended further investigation into the net clinical benefit.

Similarly, a National Institutes of Health funded, observational, single center US study evaluated 4,389 inpatients infected with COVID-19 and determined that therapeutic and prophylactic anticoagulation reduced inpatient mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.53 and 0.50, respectively for the primary outcome) and intubation (aHR, 0.69 and 0.72, respectively) over no anticoagulation.12 Notably, use of inpatient therapeutic anticoagulation commonly represented a continuation of preadmission therapy or progressive COVID-19. A subanalysis demonstrated that timely use (eg, within 48 hours of admission) of prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation, resulted in no difference (P < .08) in the primary outcome. Bleeding rates were low overall: 3%, 1.7%, and 1.9% for therapeutic, prophylactic, and no anticoagulation groups, respectively. Furthermore, selection of DOACs seems to be associated with lower bleeding rates when compared with that of LMWH heparin (1.3% vs 2.6%, respectively). In those where site of bleeding could be ascertained, the most common sites were the gastrointestinal tract (50.7%) followed by mucocutaneous (19.4%), bronchopulmonary (14.9%), and intracranial (6%). In summary, prophylactic thromboprophylaxis doses seem to be associated with positive net clinical benefit.

As of October 30, 2020, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) had reported 75,156 COVID-19 cases and 3,961 deaths.13 Since the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) does not disseminate nationally prepared anticoagulation order sets to the field, facility anticoagulation leads should be encouraged to develop local guidance-based policies to help standardize care and minimize further variations in practice, which would likely lack evidential support. Per the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS)- Nashville/Murfreesboro anticoagulation policy, we limit the ordering of parenteral anticoagulation to Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) order sets in order to provide decision support (eFigure 1, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0063). Other facilities have shown that embedded clinical decision support tools increase adherence to guideline VTE prophylaxis recommendations within the VA.14

In April 2020, the TVHS anticoagulation clinical pharmacy leads developed a COVID-19 specific order set based on review of societal guidance and the evolving, supportive literature summarized in this review with consideration of provider familiarity (eFigure 2, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0063)). Between April and June 2020, the COVID-19 order set content consistently evolved with publication of each COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guideline.1-5

Since TVHS is a high-complexity facility, we elected to use universal pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19. This construct bypasses the use of scoring tools (eg, RAM), although we use Padua and Caprini RAMS for medical and surgical patients, respectively, who are not diagnosed with COVID-19. The order set displays all acceptable guideline recommended options, delineated by location of care (eg, medical ward vs intensive care unit), prior history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and renal function. Subsequently, all potential agents, doses, and dosing interval options are offered so that the provider autonomously determines how to individualize the clinical care. Since TVHS has only diagnosed 932 ambulatory/inpatient COVID-19 cases combined, our plans are to complete a future observational analysis to determine the effectiveness of the inpatient COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis order set for our internal customers.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in arguably the most challenging medical climate in the evidence-based medicine era. Until high-quality randomized controlled trials are published, the medical community is, in a sense, operating within a crucible of crisis having to navigate therapeutic policy with little certainty. This principle holds true for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19 despite the numerous advancements in this field over the past decade.

A review of societal guidance shows there is universal agreement with regards to supporting standard doses of pharmacologicalprophylaxis in acutely ill patients either when universally applied or guided by a RAM as well as the use of universal thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients. All societies discourage the use of antiplatelet therapy for arterial thrombosis prevention and advocate for mechanical compression in patients with contraindications to pharmacologic anticoagulation. Beyond this, divergence between guidance statements begins to appear. For example, societies do not currently agree on the role and approach for extended pharmacologic prophylaxis postdischarge. The differences between societal guidance speaks to the degree of uncertainty among leading experts, which is considered to be the logical outworking of the current level of evidence. Regardless, these guidance documents should be considered the best resource currently available.

The medical community is fortunate to have robust societies that have published guidance on thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. The novelty of COVID-19 precludes these societal guidance publications from being based on high-quality evidence, but at the very least, they provide insight into how leading experts in the field of thrombosis and hemostasis are currently navigating the therapeutic landscape.

While this paper provides a summary of the current guidance, evidence is evolving at an unprecedented pace. Facilities and anticoagulation leads should be actively and frequently evaluating literature and guidance to ensure their practices and policies remain current.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville/Murfreesboro.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and resulting viral syndrome (COVID-19) was first reported in China during December 2019 and within weeks emerged in the US.1 Since it is a rapidly evolving situation, clinicians must remain current on best practices—a challenging institutional responsibility. According to LitCovid, a curated literature hub for tracking scientific information on COVID-19, there are > 54,000 articles on the subject in PubMed. Among these include venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis guidance from 4 respected thrombosis organizations/societies and the US National Institutes of Health.1-5

Observations

COVID-19 predisposes patients with and without a history of cardiovascular disease to thrombotic complications, occurring in either the venous or arterial circulation system.2,6 Early observational studies suggest that thrombotic rates may be in excess of 20 to 30%; however, the use of prophylactic anticoagulation was inconsistent among studies that were rushed to publication.6

Autopsy data have demonstrated the presence of fibrin thrombi within distended small vessels and capillaries and extensive extracellular fibrin deposition.6 Investigators compared the characteristics of acute pulmonary embolism in 23 cases with COVID-19 but with no clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis with 100 controls without COVID-19.7 They observed that thrombotic lesions had a greater distribution in peripheral lung segments (ie, peripheral arteries) and were less extensive for those with COVID-19 vs without COVID-19 infection. Thus, experts currently hypothesize that COVID-19 has a distinct “pathomechanism.” As a unique phenotype, thrombotic events represent a combination of thromboembolic disease influenced by components of the Virchow triad (eg, acute illness and immobility) and in situ immunothrombosis, a local inflammatory response.6,7

Well-established surgical and nonsurgical VTE thromboprophylaxis guidelines serve as the foundation for current COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guidance.8,9 Condition specific guidance is extrapolated from small, retrospective observational studies or based on expert opinion, representing levels 2 and 3 evidence, respectively.1-5 Table 1 captures similarities and differences among COVID-19 VTE thromboprophylaxis recommendations which vary by time to publication and by society member expertise gained from practice in the field.

Three thrombosis societies recommend universal pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for acutely ill COVID-19 patients who lack contraindications.3-5 Others recommend use of risk stratification scoring tools, such as the Padua risk assessment model (RAM) for medical patients or Caprini RAM for surgical patients, the disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) score, or the sepsis-induced coagulopathy score to determine therapeutic appropriateness (Tables 2 and 3).1,2 Since most patients hospitalized for COVID-19 will present with a pathognomonic pneumonia and an oxygen requirement, they will generally achieve a score of ≥ 4 when the Padua RAM is applied; thus, representing a clear indication for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.8,9 If the patient is pregnant, the Anticoagulation Forum recommends pharmacologic prophylaxis, consultation with an obstetrician, and use of obstetrical thromboprophylaxis guidelines.3,10,11

Most thrombosis experts prefer parenteral thromboprophylaxis, specifically low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or fondaparinux, for inpatients over use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in order to minimize the potential for drug interactions particularly when investigational antivirals are in use.4 Once-daily agents (eg, rivaroxaban, fondaparinux, and enoxaparin) are preferred over multiple daily doses to minimize staff contact with patients infected with COVID-19.4,5 Fondaparinux and DOACs should preferentially be used in patients with a recent history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with and without thrombosis (HIT/HITTS). Subcutaneous heparin is reserved for patients who are scheduled for invasive procedures or have reduced renal function (eg, creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min).1,3-5 In line with existing pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis guidance, standard prophylactic LMWH doses are recommended unless patients are obese (body mass index [BMI] > 30) or morbidly obese (BMI > 40) necessitating selection of intermediate doses.4

Since early non-US studies demonstrated high thrombotic risk without signaling a potential for harm from pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, some organizations recommend empiric escalation of anticoagulation doses for critical illness.3,4,6 Thus, it may be reasonable to advance to either intermediate pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis dosing or therapeutic doses.3 However, observational studies question this aggressive practice unless a clear indication exists for intensification (ie, atrial fibrillation, known VTE).

A large multi-institutional registry study that included 400 subjects from 5 centers demonstrated a radiographically confirmed VTE rate of 4.8% and an arterial thrombosis rate of 2.8%.6 When limiting to the critically ill setting, VTE and arterial thrombosis occurred at slightly higher rates (7.6% and 5.6%, respectively). Patients also were at risk for nonvessel thrombotic complications (eg, CVVH circuit, central venous catheters, and arterial lines). Subsequently, the overall thrombotic complication rate was 9.5%. All thrombotic events except one arose in patients who were receiving standard doses of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. Unfortunately, D-dimer elevation at admission was not only predictive of thrombosis and death, but portended bleeding. The overall bleeding rate was 4.8%, with a major bleeding rate of 2.3%. In the context of observing thromboses at normally expected rates during critical illness in association with a significant bleeding risk, the authors recommended further investigation into the net clinical benefit.

Similarly, a National Institutes of Health funded, observational, single center US study evaluated 4,389 inpatients infected with COVID-19 and determined that therapeutic and prophylactic anticoagulation reduced inpatient mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.53 and 0.50, respectively for the primary outcome) and intubation (aHR, 0.69 and 0.72, respectively) over no anticoagulation.12 Notably, use of inpatient therapeutic anticoagulation commonly represented a continuation of preadmission therapy or progressive COVID-19. A subanalysis demonstrated that timely use (eg, within 48 hours of admission) of prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation, resulted in no difference (P < .08) in the primary outcome. Bleeding rates were low overall: 3%, 1.7%, and 1.9% for therapeutic, prophylactic, and no anticoagulation groups, respectively. Furthermore, selection of DOACs seems to be associated with lower bleeding rates when compared with that of LMWH heparin (1.3% vs 2.6%, respectively). In those where site of bleeding could be ascertained, the most common sites were the gastrointestinal tract (50.7%) followed by mucocutaneous (19.4%), bronchopulmonary (14.9%), and intracranial (6%). In summary, prophylactic thromboprophylaxis doses seem to be associated with positive net clinical benefit.

As of October 30, 2020, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) had reported 75,156 COVID-19 cases and 3,961 deaths.13 Since the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) does not disseminate nationally prepared anticoagulation order sets to the field, facility anticoagulation leads should be encouraged to develop local guidance-based policies to help standardize care and minimize further variations in practice, which would likely lack evidential support. Per the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS)- Nashville/Murfreesboro anticoagulation policy, we limit the ordering of parenteral anticoagulation to Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) order sets in order to provide decision support (eFigure 1, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0063). Other facilities have shown that embedded clinical decision support tools increase adherence to guideline VTE prophylaxis recommendations within the VA.14

In April 2020, the TVHS anticoagulation clinical pharmacy leads developed a COVID-19 specific order set based on review of societal guidance and the evolving, supportive literature summarized in this review with consideration of provider familiarity (eFigure 2, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0063)). Between April and June 2020, the COVID-19 order set content consistently evolved with publication of each COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis guideline.1-5

Since TVHS is a high-complexity facility, we elected to use universal pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19. This construct bypasses the use of scoring tools (eg, RAM), although we use Padua and Caprini RAMS for medical and surgical patients, respectively, who are not diagnosed with COVID-19. The order set displays all acceptable guideline recommended options, delineated by location of care (eg, medical ward vs intensive care unit), prior history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and renal function. Subsequently, all potential agents, doses, and dosing interval options are offered so that the provider autonomously determines how to individualize the clinical care. Since TVHS has only diagnosed 932 ambulatory/inpatient COVID-19 cases combined, our plans are to complete a future observational analysis to determine the effectiveness of the inpatient COVID-19 thromboprophylaxis order set for our internal customers.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in arguably the most challenging medical climate in the evidence-based medicine era. Until high-quality randomized controlled trials are published, the medical community is, in a sense, operating within a crucible of crisis having to navigate therapeutic policy with little certainty. This principle holds true for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19 despite the numerous advancements in this field over the past decade.

A review of societal guidance shows there is universal agreement with regards to supporting standard doses of pharmacologicalprophylaxis in acutely ill patients either when universally applied or guided by a RAM as well as the use of universal thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients. All societies discourage the use of antiplatelet therapy for arterial thrombosis prevention and advocate for mechanical compression in patients with contraindications to pharmacologic anticoagulation. Beyond this, divergence between guidance statements begins to appear. For example, societies do not currently agree on the role and approach for extended pharmacologic prophylaxis postdischarge. The differences between societal guidance speaks to the degree of uncertainty among leading experts, which is considered to be the logical outworking of the current level of evidence. Regardless, these guidance documents should be considered the best resource currently available.

The medical community is fortunate to have robust societies that have published guidance on thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. The novelty of COVID-19 precludes these societal guidance publications from being based on high-quality evidence, but at the very least, they provide insight into how leading experts in the field of thrombosis and hemostasis are currently navigating the therapeutic landscape.

While this paper provides a summary of the current guidance, evidence is evolving at an unprecedented pace. Facilities and anticoagulation leads should be actively and frequently evaluating literature and guidance to ensure their practices and policies remain current.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville/Murfreesboro.

1. National Institutes of Health. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/whats-new/. Updated October 9, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

2. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950-2973. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031

3. Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):72-81. doi:10.1007/s11239-020-02138-z

4. Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: Clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1859-1865. doi:10.1111/jth.14929

5. Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, et al. Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of VTE in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2020;158(3):1143-1163. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559

6. Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489-500. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006520.

7. van Dam LF, Kroft LJM, van der Wal LI, et al. Clinical and computed tomography characteristics of COVID-19 associated acute pulmonary embolism: a different phenotype of thrombotic disease?. Thromb Res. 2020;193:86-89. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.010

8. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e195S-e226S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2296

9. Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 May;141(5):1369]. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e227S-e277S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2297

10. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196 Summary: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):243-248. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002707

11. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. Green-top Guideline. No. 37a. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-37a.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed October 15, 2020.

12. Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, et al. Anticoagulation, mortality, bleeding and pathology among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a single health system study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 24]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(16):1815-1826. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.041

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs COVID-19 national summary. https://www.accesstocare.va.gov/Healthcare/COVID19NationalSummary. Updated November 1, 2020. Accessed November 1, 2020.

14. George B, Gonzales S, Patel K, Petit S, Franck AJ, Bovio Franck J. Impact of a clinical decision-support tool on venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. J Pharm Technol. 2020;36(4):141-147. doi:10.1177/8755122520930288

1. National Institutes of Health. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/whats-new/. Updated October 9, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

2. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950-2973. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031

3. Barnes GD, Burnett A, Allen A, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):72-81. doi:10.1007/s11239-020-02138-z

4. Spyropoulos AC, Levy JH, Ageno W, et al. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: Clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1859-1865. doi:10.1111/jth.14929

5. Moores LK, Tritschler T, Brosnahan S, et al. Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of VTE in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2020;158(3):1143-1163. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559

6. Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489-500. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006520.

7. van Dam LF, Kroft LJM, van der Wal LI, et al. Clinical and computed tomography characteristics of COVID-19 associated acute pulmonary embolism: a different phenotype of thrombotic disease?. Thromb Res. 2020;193:86-89. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.06.010

8. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e195S-e226S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2296

9. Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Chest. 2012 May;141(5):1369]. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e227S-e277S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2297

10. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196 Summary: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):243-248. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002707

11. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. Green-top Guideline. No. 37a. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-37a.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed October 15, 2020.

12. Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, et al. Anticoagulation, mortality, bleeding and pathology among patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a single health system study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 24]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(16):1815-1826. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.041

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Department of Veterans Affairs COVID-19 national summary. https://www.accesstocare.va.gov/Healthcare/COVID19NationalSummary. Updated November 1, 2020. Accessed November 1, 2020.

14. George B, Gonzales S, Patel K, Petit S, Franck AJ, Bovio Franck J. Impact of a clinical decision-support tool on venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. J Pharm Technol. 2020;36(4):141-147. doi:10.1177/8755122520930288

Coaching in medicine: A perspective

Coaching is a new topic in medicine. I first heard about coaching several years ago and met the term with skepticism. I was unsure how coaching was different than mentoring or advising and I wondered about its usefulness. However, the reason that I even started to learn about coaching was because I was struggling. I had finally arrived in my career, I had my dream job with two healthy kids, a perfect house, and good marriage. I kept hearing the refrain in my head: “Is this all there is?” I had this arrival fallacy that after all this striving and straining that I would finally be content. I felt unfulfilled and was dissatisfied with where I was that was affecting all parts of my life.

As I was wrestling with these thoughts, I had an opportunity to become a coach to residents around the country through the Association of Women Surgeons. I discussed with them what fills them up, what gets them down, how to set goals, and what their goals were for the year, as well as imposter syndrome. Impostor syndrome is defined as a pattern in which an individual doubts their accomplishments or talents and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud.” Despite external evidence of their competence, those experiencing this phenomenon remain convinced that they are fooling everyone around them and do not deserve all they have achieved. Individuals incorrectly attribute their success to luck or interpret it as a result of deceiving others into thinking they are more intelligent than they perceive themselves to be. Imposter syndrome is prevalent and deep in medicine. As perfectionists, we are especially vulnerable to imposter syndrome as we set unrealistic ideals for ourselves. When we fail to reach these ideals, we feel like frauds, setting up this cycle of self-doubt that is toxic. When we feel that we can’t achieve the goals that we are striving for we will always find ourselves lacking. There is a slow, insidious erosion of self over the years. Imposter syndrome is well documented in medicine and is even felt as early as medical school.1,2

When I began coaching these residents the most profound thing that came out of these sessions was that my life was getting better – I knew what filled me up, what got me down, what my goals were for the year, and how I still deal with imposter syndrome. Coaching gave me a framework for helping determine what I wanted for the rest of my life. As I began coaching, I started learning all the ways in which I could figure out my values, my personal and professional goals, and perhaps most importantly, my relationships with myself and others.

Another perspective on coaching is to look at a professional athlete such as Tom Brady, one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time. He has a quarterback coach. No coach is going to be a better quarterback than Tom Brady. A coach for him is to be there as an advocate, break his fundamentals down technically, and help him improve upon what he already knows. A coach also identifies strengths and weaknesses, and helps him capitalize on both by bringing awareness, reflection, accountability, and support. If world-class athletes still want and benefit from coaching in a sport they have already mastered, coaching for physicians is just another tool to help us improve our abilities in and out of medicine.

Coaching is more encompassing than advising or mentoring. It is about examining deeply held beliefs to see if they are really serving us, if they are in line with our values and how we want to live our lives.

Coaching has also been validated in medicine in several papers. In an article by Dyrbye et al. in JAMA Internal Medicine, measures of emotional exhaustion and burnout decreased in physicians who were coached and increased in those who were not.3 In another study from this year by McGonagle et al., a randomized, controlled trial showed that primary care physicians who had sessions (as short as 6 weeks) to address burnout, psychological capital, and job satisfaction experienced an improvement in measures which persisted for 6 months after intervention.4 Numerous other articles in medicine also exist to demonstrate the effect of coaching on mitigating burnout at an institutional level.

Physicians are inherently driven by their love of learning. As physicians, we love getting to the root cause of any problem and coming up with creative solutions. Any challenge we have, or just wanting to improve the quality of our lives, can be addressed with coaching. As perpetual students we can use coaching to truly master ourselves.

Dr. Shah is associate professor of surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. Instagram: ami.shahmdcoaching.

References

1. Gottlieb M et al. Med Educ. 2020 Feb;54(2):116-24.

2. Villwock JA et al. Int J Med Educ. 2016 Oct 31;7:364-9.

3. Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5;179(10):1406-14.

4. McGonagle AK et al. J Occup Health Psychol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000180.

Coaching is a new topic in medicine. I first heard about coaching several years ago and met the term with skepticism. I was unsure how coaching was different than mentoring or advising and I wondered about its usefulness. However, the reason that I even started to learn about coaching was because I was struggling. I had finally arrived in my career, I had my dream job with two healthy kids, a perfect house, and good marriage. I kept hearing the refrain in my head: “Is this all there is?” I had this arrival fallacy that after all this striving and straining that I would finally be content. I felt unfulfilled and was dissatisfied with where I was that was affecting all parts of my life.

As I was wrestling with these thoughts, I had an opportunity to become a coach to residents around the country through the Association of Women Surgeons. I discussed with them what fills them up, what gets them down, how to set goals, and what their goals were for the year, as well as imposter syndrome. Impostor syndrome is defined as a pattern in which an individual doubts their accomplishments or talents and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud.” Despite external evidence of their competence, those experiencing this phenomenon remain convinced that they are fooling everyone around them and do not deserve all they have achieved. Individuals incorrectly attribute their success to luck or interpret it as a result of deceiving others into thinking they are more intelligent than they perceive themselves to be. Imposter syndrome is prevalent and deep in medicine. As perfectionists, we are especially vulnerable to imposter syndrome as we set unrealistic ideals for ourselves. When we fail to reach these ideals, we feel like frauds, setting up this cycle of self-doubt that is toxic. When we feel that we can’t achieve the goals that we are striving for we will always find ourselves lacking. There is a slow, insidious erosion of self over the years. Imposter syndrome is well documented in medicine and is even felt as early as medical school.1,2

When I began coaching these residents the most profound thing that came out of these sessions was that my life was getting better – I knew what filled me up, what got me down, what my goals were for the year, and how I still deal with imposter syndrome. Coaching gave me a framework for helping determine what I wanted for the rest of my life. As I began coaching, I started learning all the ways in which I could figure out my values, my personal and professional goals, and perhaps most importantly, my relationships with myself and others.

Another perspective on coaching is to look at a professional athlete such as Tom Brady, one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time. He has a quarterback coach. No coach is going to be a better quarterback than Tom Brady. A coach for him is to be there as an advocate, break his fundamentals down technically, and help him improve upon what he already knows. A coach also identifies strengths and weaknesses, and helps him capitalize on both by bringing awareness, reflection, accountability, and support. If world-class athletes still want and benefit from coaching in a sport they have already mastered, coaching for physicians is just another tool to help us improve our abilities in and out of medicine.

Coaching is more encompassing than advising or mentoring. It is about examining deeply held beliefs to see if they are really serving us, if they are in line with our values and how we want to live our lives.

Coaching has also been validated in medicine in several papers. In an article by Dyrbye et al. in JAMA Internal Medicine, measures of emotional exhaustion and burnout decreased in physicians who were coached and increased in those who were not.3 In another study from this year by McGonagle et al., a randomized, controlled trial showed that primary care physicians who had sessions (as short as 6 weeks) to address burnout, psychological capital, and job satisfaction experienced an improvement in measures which persisted for 6 months after intervention.4 Numerous other articles in medicine also exist to demonstrate the effect of coaching on mitigating burnout at an institutional level.

Physicians are inherently driven by their love of learning. As physicians, we love getting to the root cause of any problem and coming up with creative solutions. Any challenge we have, or just wanting to improve the quality of our lives, can be addressed with coaching. As perpetual students we can use coaching to truly master ourselves.

Dr. Shah is associate professor of surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. Instagram: ami.shahmdcoaching.

References

1. Gottlieb M et al. Med Educ. 2020 Feb;54(2):116-24.

2. Villwock JA et al. Int J Med Educ. 2016 Oct 31;7:364-9.

3. Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5;179(10):1406-14.

4. McGonagle AK et al. J Occup Health Psychol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000180.

Coaching is a new topic in medicine. I first heard about coaching several years ago and met the term with skepticism. I was unsure how coaching was different than mentoring or advising and I wondered about its usefulness. However, the reason that I even started to learn about coaching was because I was struggling. I had finally arrived in my career, I had my dream job with two healthy kids, a perfect house, and good marriage. I kept hearing the refrain in my head: “Is this all there is?” I had this arrival fallacy that after all this striving and straining that I would finally be content. I felt unfulfilled and was dissatisfied with where I was that was affecting all parts of my life.

As I was wrestling with these thoughts, I had an opportunity to become a coach to residents around the country through the Association of Women Surgeons. I discussed with them what fills them up, what gets them down, how to set goals, and what their goals were for the year, as well as imposter syndrome. Impostor syndrome is defined as a pattern in which an individual doubts their accomplishments or talents and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud.” Despite external evidence of their competence, those experiencing this phenomenon remain convinced that they are fooling everyone around them and do not deserve all they have achieved. Individuals incorrectly attribute their success to luck or interpret it as a result of deceiving others into thinking they are more intelligent than they perceive themselves to be. Imposter syndrome is prevalent and deep in medicine. As perfectionists, we are especially vulnerable to imposter syndrome as we set unrealistic ideals for ourselves. When we fail to reach these ideals, we feel like frauds, setting up this cycle of self-doubt that is toxic. When we feel that we can’t achieve the goals that we are striving for we will always find ourselves lacking. There is a slow, insidious erosion of self over the years. Imposter syndrome is well documented in medicine and is even felt as early as medical school.1,2

When I began coaching these residents the most profound thing that came out of these sessions was that my life was getting better – I knew what filled me up, what got me down, what my goals were for the year, and how I still deal with imposter syndrome. Coaching gave me a framework for helping determine what I wanted for the rest of my life. As I began coaching, I started learning all the ways in which I could figure out my values, my personal and professional goals, and perhaps most importantly, my relationships with myself and others.

Another perspective on coaching is to look at a professional athlete such as Tom Brady, one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time. He has a quarterback coach. No coach is going to be a better quarterback than Tom Brady. A coach for him is to be there as an advocate, break his fundamentals down technically, and help him improve upon what he already knows. A coach also identifies strengths and weaknesses, and helps him capitalize on both by bringing awareness, reflection, accountability, and support. If world-class athletes still want and benefit from coaching in a sport they have already mastered, coaching for physicians is just another tool to help us improve our abilities in and out of medicine.

Coaching is more encompassing than advising or mentoring. It is about examining deeply held beliefs to see if they are really serving us, if they are in line with our values and how we want to live our lives.

Coaching has also been validated in medicine in several papers. In an article by Dyrbye et al. in JAMA Internal Medicine, measures of emotional exhaustion and burnout decreased in physicians who were coached and increased in those who were not.3 In another study from this year by McGonagle et al., a randomized, controlled trial showed that primary care physicians who had sessions (as short as 6 weeks) to address burnout, psychological capital, and job satisfaction experienced an improvement in measures which persisted for 6 months after intervention.4 Numerous other articles in medicine also exist to demonstrate the effect of coaching on mitigating burnout at an institutional level.

Physicians are inherently driven by their love of learning. As physicians, we love getting to the root cause of any problem and coming up with creative solutions. Any challenge we have, or just wanting to improve the quality of our lives, can be addressed with coaching. As perpetual students we can use coaching to truly master ourselves.

Dr. Shah is associate professor of surgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. Instagram: ami.shahmdcoaching.

References

1. Gottlieb M et al. Med Educ. 2020 Feb;54(2):116-24.

2. Villwock JA et al. Int J Med Educ. 2016 Oct 31;7:364-9.

3. Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5;179(10):1406-14.

4. McGonagle AK et al. J Occup Health Psychol. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000180.

Poor and minority children with food allergies overlooked and in danger

As Emily Brown stood in a food pantry looking at her options, she felt alone. Up to that point, she had never struggled financially. But there she was, desperate to find safe food for her young daughter with food allergies. What she found was a jar of salsa and some potatoes.

“That was all that was available,” said Ms. Brown, who lives in Kansas City, Kansas. “It was just a desperate place.”

When she became a parent, Ms. Brown left her job for lack of child care that would accommodate her daughter’s allergies to peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, wheat, and soy. When she and her husband then turned to a federal food assistance program, they found few allowable allergy substitutions. The closest allergy support group she could find was an hour away. She was almost always the only Black parent, and the only poor parent, there.

Ms. Brown called national food allergy advocacy organizations to ask for guidance to help poor families find safe food and medical resources, but she said she was told that wasn’t their focus. Support groups, fundraising activities, and advocacy efforts, plus clinical and research outreach, were targeted at wealthier – and White – families. Advertising rarely reflected families that looked like hers. She felt unseen.

“In many ways, food allergy is an invisible disease. The burden of the disease, the activities and energy it takes to avoid allergens, are mostly invisible to those not impacted,” Ms. Brown said. “Black and other minority patients often lack voice and visibility in the health care system. Add the additional burden of an invisible condition and you are in a really vulnerable position.”

An estimated 6 million children in the United States have food allergies, 40% of them with more than one. Though limited research has been done on race and class breakdowns, recent studies show that poor children and some groups of minority children not only have a higher incidence of food allergies than White children, but their families also have more difficulty accessing appropriate child care, safe food, medical care, and lifesaving medicine like epinephrine for them.

Black children are 7% more likely to have food allergies than white children, according to a 2020 study by Dr. Ruchi Gupta, MD, at Northwestern University, Chicago. To be sure, the study shows that Asian children are 24% more likely than White children to have food allergies. But Black and Hispanic children are disproportionately more likely to live in poor communities, to have asthma, and to suffer from systemic racism in the delivery of medical care.

“Many times, a mother is frank and says: ‘I have $20-$40 to buy groceries for the week, and if I buy these foods that you are telling me to buy, I will not be able to feed my entire family,’” said Carla Davis, MD, director of the food allergy program at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital. “If you are diagnosed with a food allergy and you don’t have disposable income or disposable time, there is really no way that you will be able to alter your diet in a way that your child is going to stay away from their allergen.”

Fed up with the lack of support, Ms. Brown founded the Food Equality Initiative advocacy organization in 2014. It offers an online marketplace to income-eligible families in Kansas and Missouri who, with a doctor’s note about the allergy, can order free allergy-safe food to fit their needs.

Nationwide, though, families’ needs far outstrip what her group can offer – and the problem has gotten worse amid the economic squeeze of the COVID pandemic. Job losses and business closures have exacerbated the barriers to finding and affording nutritious food, according to a report from Feeding America, an association of food banks.

Ms. Brown said her organization more than doubled its clientele in March through August, compared with the same period in 2019. And though it currently serves only Missouri and Kansas, she said the organization has been fielding an increasing number of calls from across the country since the pandemic began.

For low-income minorities, who live disproportionately in food deserts, fresh and allergy-friendly foods can be especially expensive and difficult to find in the best of times.

Food assistance programs are heavily weighted to prepackaged and processed foods, which often include the very ingredients that are problematic. Black children are more likely to be allergic to wheat and soy than White children, and both Black and Hispanic children are more likely to be allergic to corn, shellfish, and fish, according to a 2016 study.

Some programs allow few allergy substitutions. For example, the federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children allows only canned beans as a substitute for peanut butter. While nutritionally similar, beans are not as easy to pack for a kid’s lunch. Ms. Brown questions why WIC won’t allow a seed butter, such as sunflower butter, instead. She said they are nutritionally and functionally similar and are offered as allergy substitutions in other food programs.

Making matters worse, low-income households pay more than twice as much as higher-income families for the emergency medical care their children receive for their allergies, according to a 2016 study by Dr. Gupta. The kids often arrive at the hospital in more distress because they lack safe food and allergy medications – and because asthma, which disproportionately hits Black and Puerto Rican children and low-income communities, complicates allergic reactions.

“So, in these vulnerable populations, it’s like a double whammy, and we see that reflected in the data,” said Lakiea Wright-Bello, MD, a medical director in specialty diagnostics at Thermo Fisher Scientific and an allergist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Thomas and Dina Silvera, who are Black and Latina, lived this horror firsthand. After their 3-year-old son, Elijah-Alavi, died as a result of a dairy allergy when fed a grilled cheese instead of his allergen-free food at his preschool, they launched the Elijah-Alavi Foundation to address the dearth of information about food allergies and the critical lack of culturally sensitive medical care in low-income communities.

“We started it for a cause, not because we wanted to, but because we had to,” said Thomas Silvera. “Our main focus is to bring to underserved communities – especially communities of color – this information at no cost to them.”

Recently, other advocacy groups, including Food Allergy Research & Education, a national advocacy organization, also have started to turn their attention to a lack of access and support in poor and minority communities. When Lisa Gable, who is White, took over at the group known as FARE in 2018, she began to diversify the organization internally and to make it more inclusive.

“There wasn’t a big tent when I walked in the door,” said Ms. Gable. “What we have been focused on doing is trying to find partners and relationships that will allow us to diversify those engaged in the community, because it has not been a diverse community.”

FARE has funded research into the cost of food allergies. It is also expanding its patient registry, which collects data for research, as well as its clinical network of medical institutions to include more diverse communities.

Dr. Gupta is now leading one of the first studies funded by the National Institutes of Health to investigate food allergy in children by race and ethnicity. It looks at all aspects of food allergies, including family life, management, access to care, and genetics.

“That’s a big deal,” said Dr. Gupta. “Because if we really want to improve food allergy management, care and understanding, we really need to understand how it impacts different groups. And that hasn’t been done.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

As Emily Brown stood in a food pantry looking at her options, she felt alone. Up to that point, she had never struggled financially. But there she was, desperate to find safe food for her young daughter with food allergies. What she found was a jar of salsa and some potatoes.

“That was all that was available,” said Ms. Brown, who lives in Kansas City, Kansas. “It was just a desperate place.”

When she became a parent, Ms. Brown left her job for lack of child care that would accommodate her daughter’s allergies to peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, wheat, and soy. When she and her husband then turned to a federal food assistance program, they found few allowable allergy substitutions. The closest allergy support group she could find was an hour away. She was almost always the only Black parent, and the only poor parent, there.

Ms. Brown called national food allergy advocacy organizations to ask for guidance to help poor families find safe food and medical resources, but she said she was told that wasn’t their focus. Support groups, fundraising activities, and advocacy efforts, plus clinical and research outreach, were targeted at wealthier – and White – families. Advertising rarely reflected families that looked like hers. She felt unseen.

“In many ways, food allergy is an invisible disease. The burden of the disease, the activities and energy it takes to avoid allergens, are mostly invisible to those not impacted,” Ms. Brown said. “Black and other minority patients often lack voice and visibility in the health care system. Add the additional burden of an invisible condition and you are in a really vulnerable position.”

An estimated 6 million children in the United States have food allergies, 40% of them with more than one. Though limited research has been done on race and class breakdowns, recent studies show that poor children and some groups of minority children not only have a higher incidence of food allergies than White children, but their families also have more difficulty accessing appropriate child care, safe food, medical care, and lifesaving medicine like epinephrine for them.

Black children are 7% more likely to have food allergies than white children, according to a 2020 study by Dr. Ruchi Gupta, MD, at Northwestern University, Chicago. To be sure, the study shows that Asian children are 24% more likely than White children to have food allergies. But Black and Hispanic children are disproportionately more likely to live in poor communities, to have asthma, and to suffer from systemic racism in the delivery of medical care.

“Many times, a mother is frank and says: ‘I have $20-$40 to buy groceries for the week, and if I buy these foods that you are telling me to buy, I will not be able to feed my entire family,’” said Carla Davis, MD, director of the food allergy program at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital. “If you are diagnosed with a food allergy and you don’t have disposable income or disposable time, there is really no way that you will be able to alter your diet in a way that your child is going to stay away from their allergen.”

Fed up with the lack of support, Ms. Brown founded the Food Equality Initiative advocacy organization in 2014. It offers an online marketplace to income-eligible families in Kansas and Missouri who, with a doctor’s note about the allergy, can order free allergy-safe food to fit their needs.

Nationwide, though, families’ needs far outstrip what her group can offer – and the problem has gotten worse amid the economic squeeze of the COVID pandemic. Job losses and business closures have exacerbated the barriers to finding and affording nutritious food, according to a report from Feeding America, an association of food banks.

Ms. Brown said her organization more than doubled its clientele in March through August, compared with the same period in 2019. And though it currently serves only Missouri and Kansas, she said the organization has been fielding an increasing number of calls from across the country since the pandemic began.

For low-income minorities, who live disproportionately in food deserts, fresh and allergy-friendly foods can be especially expensive and difficult to find in the best of times.

Food assistance programs are heavily weighted to prepackaged and processed foods, which often include the very ingredients that are problematic. Black children are more likely to be allergic to wheat and soy than White children, and both Black and Hispanic children are more likely to be allergic to corn, shellfish, and fish, according to a 2016 study.

Some programs allow few allergy substitutions. For example, the federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children allows only canned beans as a substitute for peanut butter. While nutritionally similar, beans are not as easy to pack for a kid’s lunch. Ms. Brown questions why WIC won’t allow a seed butter, such as sunflower butter, instead. She said they are nutritionally and functionally similar and are offered as allergy substitutions in other food programs.

Making matters worse, low-income households pay more than twice as much as higher-income families for the emergency medical care their children receive for their allergies, according to a 2016 study by Dr. Gupta. The kids often arrive at the hospital in more distress because they lack safe food and allergy medications – and because asthma, which disproportionately hits Black and Puerto Rican children and low-income communities, complicates allergic reactions.

“So, in these vulnerable populations, it’s like a double whammy, and we see that reflected in the data,” said Lakiea Wright-Bello, MD, a medical director in specialty diagnostics at Thermo Fisher Scientific and an allergist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Thomas and Dina Silvera, who are Black and Latina, lived this horror firsthand. After their 3-year-old son, Elijah-Alavi, died as a result of a dairy allergy when fed a grilled cheese instead of his allergen-free food at his preschool, they launched the Elijah-Alavi Foundation to address the dearth of information about food allergies and the critical lack of culturally sensitive medical care in low-income communities.

“We started it for a cause, not because we wanted to, but because we had to,” said Thomas Silvera. “Our main focus is to bring to underserved communities – especially communities of color – this information at no cost to them.”

Recently, other advocacy groups, including Food Allergy Research & Education, a national advocacy organization, also have started to turn their attention to a lack of access and support in poor and minority communities. When Lisa Gable, who is White, took over at the group known as FARE in 2018, she began to diversify the organization internally and to make it more inclusive.

“There wasn’t a big tent when I walked in the door,” said Ms. Gable. “What we have been focused on doing is trying to find partners and relationships that will allow us to diversify those engaged in the community, because it has not been a diverse community.”

FARE has funded research into the cost of food allergies. It is also expanding its patient registry, which collects data for research, as well as its clinical network of medical institutions to include more diverse communities.

Dr. Gupta is now leading one of the first studies funded by the National Institutes of Health to investigate food allergy in children by race and ethnicity. It looks at all aspects of food allergies, including family life, management, access to care, and genetics.

“That’s a big deal,” said Dr. Gupta. “Because if we really want to improve food allergy management, care and understanding, we really need to understand how it impacts different groups. And that hasn’t been done.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

As Emily Brown stood in a food pantry looking at her options, she felt alone. Up to that point, she had never struggled financially. But there she was, desperate to find safe food for her young daughter with food allergies. What she found was a jar of salsa and some potatoes.

“That was all that was available,” said Ms. Brown, who lives in Kansas City, Kansas. “It was just a desperate place.”

When she became a parent, Ms. Brown left her job for lack of child care that would accommodate her daughter’s allergies to peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, wheat, and soy. When she and her husband then turned to a federal food assistance program, they found few allowable allergy substitutions. The closest allergy support group she could find was an hour away. She was almost always the only Black parent, and the only poor parent, there.

Ms. Brown called national food allergy advocacy organizations to ask for guidance to help poor families find safe food and medical resources, but she said she was told that wasn’t their focus. Support groups, fundraising activities, and advocacy efforts, plus clinical and research outreach, were targeted at wealthier – and White – families. Advertising rarely reflected families that looked like hers. She felt unseen.

“In many ways, food allergy is an invisible disease. The burden of the disease, the activities and energy it takes to avoid allergens, are mostly invisible to those not impacted,” Ms. Brown said. “Black and other minority patients often lack voice and visibility in the health care system. Add the additional burden of an invisible condition and you are in a really vulnerable position.”