User login

For MD-IQ use only

FDA approves rituximab to treat children with rare vasculitis

The Food and Drug Administration approved rituximab (Rituxan) by injection to treat granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) in children 2 years of age and older in combination with glucocorticoid treatment, according to an FDA news release.

These rare forms of vasculitis damage small blood vessels through inflammation and can lead to serious organ failure, including lungs and kidneys.

The Genentech drug received priority review and an orphan drug designation based on the results of a pediatric clinical trial of 25 patients aged 6-17 years with active GPA or MPA who were treated with rituximab in an international multicenter, open-label, uncontrolled study. Patients in the trial were also given methylprednisolone prior to starting treatment.

The trial consisted of a 6-month remission induction phase where patients were treated only with rituximab and glucocorticoids. In addition, patients who had not achieved remission could receive additional treatment, including other therapies, at the discretion of the investigator, according to the FDA. By 6 months, 14 of the patients were in remission, and after 18 months, all 25 patients were in remission.

Rituximab contains a boxed warning regarding increased risks of fatal infusion reactions, potentially fatal severe skin and mouth reactions, hepatitis B virus reactivation that may cause serious or lethal liver problems, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a rare, potentially lethal brain infection.

The trial was conducted and sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, which owns Genentech.

The Food and Drug Administration approved rituximab (Rituxan) by injection to treat granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) in children 2 years of age and older in combination with glucocorticoid treatment, according to an FDA news release.

These rare forms of vasculitis damage small blood vessels through inflammation and can lead to serious organ failure, including lungs and kidneys.

The Genentech drug received priority review and an orphan drug designation based on the results of a pediatric clinical trial of 25 patients aged 6-17 years with active GPA or MPA who were treated with rituximab in an international multicenter, open-label, uncontrolled study. Patients in the trial were also given methylprednisolone prior to starting treatment.

The trial consisted of a 6-month remission induction phase where patients were treated only with rituximab and glucocorticoids. In addition, patients who had not achieved remission could receive additional treatment, including other therapies, at the discretion of the investigator, according to the FDA. By 6 months, 14 of the patients were in remission, and after 18 months, all 25 patients were in remission.

Rituximab contains a boxed warning regarding increased risks of fatal infusion reactions, potentially fatal severe skin and mouth reactions, hepatitis B virus reactivation that may cause serious or lethal liver problems, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a rare, potentially lethal brain infection.

The trial was conducted and sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, which owns Genentech.

The Food and Drug Administration approved rituximab (Rituxan) by injection to treat granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) in children 2 years of age and older in combination with glucocorticoid treatment, according to an FDA news release.

These rare forms of vasculitis damage small blood vessels through inflammation and can lead to serious organ failure, including lungs and kidneys.

The Genentech drug received priority review and an orphan drug designation based on the results of a pediatric clinical trial of 25 patients aged 6-17 years with active GPA or MPA who were treated with rituximab in an international multicenter, open-label, uncontrolled study. Patients in the trial were also given methylprednisolone prior to starting treatment.

The trial consisted of a 6-month remission induction phase where patients were treated only with rituximab and glucocorticoids. In addition, patients who had not achieved remission could receive additional treatment, including other therapies, at the discretion of the investigator, according to the FDA. By 6 months, 14 of the patients were in remission, and after 18 months, all 25 patients were in remission.

Rituximab contains a boxed warning regarding increased risks of fatal infusion reactions, potentially fatal severe skin and mouth reactions, hepatitis B virus reactivation that may cause serious or lethal liver problems, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a rare, potentially lethal brain infection.

The trial was conducted and sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, which owns Genentech.

October 2019 - Quick Quiz Question 2

Q2. Correct answer: C

Rationale

Vitamin B12 absorption requires intrinsic factor to bind B12 to facilitate absorption in the terminal ileum. Any interruption of terminal ileal absorptive capacity can thus lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. Crohn's disease, ileal resection). Intrinsic factor is produced by parietal cells, so any condition that leads to decreased parietal cell mass or function can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. atrophic gastritis). In order for intrinsic factor to bind vitamin B12, B12 must first be released from binding with the R-protein, which occurs via pancreatic protease breakdown of the R-protein. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are not able to break down the R-protein as efficiently, and thus can develop vitamin B12 deficiency.

References

1. Green R. Vitamin B12 deficiency from the perspective of a practicing hematologist. Blood. 2017;129(19):2603-11.

2. Gueant GL, at al. Malabsorption of vitamin B12 in pancreatic insufficiency of the adult and of the child. Pancreas 1990 Sep;5(5):559-67.

ginews@gastro.org

Q2. Correct answer: C

Rationale

Vitamin B12 absorption requires intrinsic factor to bind B12 to facilitate absorption in the terminal ileum. Any interruption of terminal ileal absorptive capacity can thus lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. Crohn's disease, ileal resection). Intrinsic factor is produced by parietal cells, so any condition that leads to decreased parietal cell mass or function can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. atrophic gastritis). In order for intrinsic factor to bind vitamin B12, B12 must first be released from binding with the R-protein, which occurs via pancreatic protease breakdown of the R-protein. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are not able to break down the R-protein as efficiently, and thus can develop vitamin B12 deficiency.

References

1. Green R. Vitamin B12 deficiency from the perspective of a practicing hematologist. Blood. 2017;129(19):2603-11.

2. Gueant GL, at al. Malabsorption of vitamin B12 in pancreatic insufficiency of the adult and of the child. Pancreas 1990 Sep;5(5):559-67.

ginews@gastro.org

Q2. Correct answer: C

Rationale

Vitamin B12 absorption requires intrinsic factor to bind B12 to facilitate absorption in the terminal ileum. Any interruption of terminal ileal absorptive capacity can thus lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. Crohn's disease, ileal resection). Intrinsic factor is produced by parietal cells, so any condition that leads to decreased parietal cell mass or function can lead to vitamin B12 deficiency (e.g. atrophic gastritis). In order for intrinsic factor to bind vitamin B12, B12 must first be released from binding with the R-protein, which occurs via pancreatic protease breakdown of the R-protein. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are not able to break down the R-protein as efficiently, and thus can develop vitamin B12 deficiency.

References

1. Green R. Vitamin B12 deficiency from the perspective of a practicing hematologist. Blood. 2017;129(19):2603-11.

2. Gueant GL, at al. Malabsorption of vitamin B12 in pancreatic insufficiency of the adult and of the child. Pancreas 1990 Sep;5(5):559-67.

ginews@gastro.org

A 65-year-old man with chronic pancreatitis related to long-standing alcohol use comes to see you for a second opinion. He has been abstinent from alcohol for 20 years. He reports a 1-year history of six loose, oily stools per day, but minimal abdominal pain. He was recently found to have vitamin B12 deficiency by his primary care provider.

October 2019 - Quick Question 1

Q1. Correct Answer: B

Rationale

In patients 70 years or older with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding and on chronic NSAIDs, the use of a PPI can reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding. In the setting of an acute bleeding episode, aspirin should resume within 7 days of adequate hemostasis. However, there are no advantages of enteric coated or buffered aspirin in reducing the risk of recurrent bleeding.

References

1. Kelly JP, Kaufmann DW, et al. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet 1996;348:1413-6.

2. Laine L, Jensen D. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345-60.

Q1. Correct Answer: B

Rationale

In patients 70 years or older with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding and on chronic NSAIDs, the use of a PPI can reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding. In the setting of an acute bleeding episode, aspirin should resume within 7 days of adequate hemostasis. However, there are no advantages of enteric coated or buffered aspirin in reducing the risk of recurrent bleeding.

References

1. Kelly JP, Kaufmann DW, et al. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet 1996;348:1413-6.

2. Laine L, Jensen D. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345-60.

Q1. Correct Answer: B

Rationale

In patients 70 years or older with a history of gastrointestinal bleeding and on chronic NSAIDs, the use of a PPI can reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding. In the setting of an acute bleeding episode, aspirin should resume within 7 days of adequate hemostasis. However, there are no advantages of enteric coated or buffered aspirin in reducing the risk of recurrent bleeding.

References

1. Kelly JP, Kaufmann DW, et al. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet 1996;348:1413-6.

2. Laine L, Jensen D. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345-60.

A 73-year-old man with coronary artery disease requiring coronary artery bypass grafting and daily low-dose plain aspirin is hospitalized with acute anemia and melena. His aspirin is withheld and he is placed empirically on intravenous proton pump inhibitors with continuous infusion. He undergoes upper endoscopy, which reveals a single 8-mm ulcer in the duodenal bulb with a visible vessel. After successful endoscopic therapy with epinephrine injection and the use of hemoclips, he remains stable. Prior to discharge, he is recommended to resume aspirin therapy.

What is your diagnosis? - October 2019

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

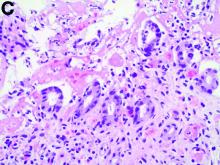

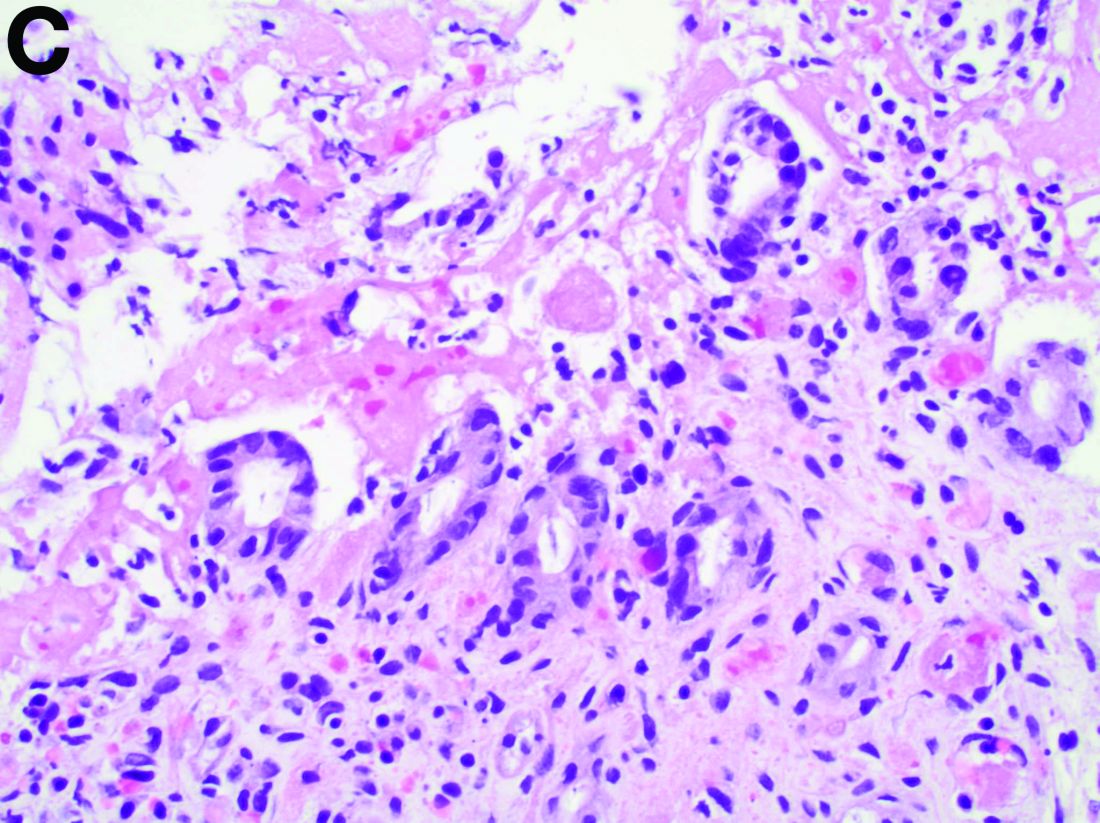

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

Exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis or “runner’s colitis”

Biopsies of the abnormal mucosa noted on colonoscopy revealed mucosal necrosis with stromal hyalinization, crypt atrophy, and acute inflammation (Figure C), consistent with a diagnosis of exercise-induced acute ischemic colitis. Exercise-induced ischemic colitis, sometimes referred to colloquially as “runner’s colitis,” is a rare but well-documented complication of long distance running.1

A number of physiologic changes occur in the human body during prolonged exercise, including redirection of blood flow from the gut to exercising muscles. Although this process usually serves to better manage available oxygen and nutrients during times of stress, it can occasionally result in unfavorable outcomes as depicted herein. During exercise, the increased sympathetic tone influences rerouting blood with some studies demonstrating up to 80% reduction in splanchnic blood flow with prolonged exercise.2 In addition, the transient hypovolemia many runners experience if they do not remain adequately hydrated can impair mesenteric perfusion. The splenic flexure of the colon and the rectosigmoid junction are particularly prone to ischemic injury in these settings, given the “watershed” nature of their blood supply.

An extensive review of published cases revealed the reversible nature of this ailment, as all but one subject, who required subtotal colectomy for colonic perforation, had resolution of ischemia on repeat evaluation.3 The patient had a follow-up computed tomography angiogram 2 months after discharge that revealed unremarkable mesenteric vasculature and resolution of the previously seen colonic wall thickening and pericolonic fat stranding.

References

1. Buckman MT. Gastrointestinal bleeding in long-distance runners. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:127-8.

2. Qamar MI, Read AE. Effects of exercise on mesenteric blood flow in man. Gut.1987;28:583-7.

3. Beaumont AC, Teare JP. Subtotal colectomy following marathon running in a female patient. J R Soc Med, 1991;84:439-40.

A 28-year-old woman with a history of mild iron-deficiency anemia presented with acute onset of lower abdominal pain and bloody bowel movements. The patient reported actively training for a marathon and on the day of presentation she ran approximately 20 miles before developing acute sharp, crampy lower abdominal pain. This discomfort forced her to stop her run early and she subsequently had several loose bowel movements streaked with bright red blood that prompted evaluation.

In the emergency department, she was afebrile and hemodynamically stable with physical examination revealing slight tenderness to palpation in the left upper quadrant of her abdomen. Laboratory results were significant for mild leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.1 × 103/microL), anemia (hemoglobin, 10.3 g/dL), and iron deficiency (ferritin, 14 ng/mL; iron, 11 microg/dL; and iron saturation, 2%). Of note, lactate, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels were all within normal limits.

Building Blocks: AVAHO Past President Looks Back

MINNEAPOLIS -- Oncologist Mark Klein, MD, may have just stepped down as president of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), but his main legacy—a foundation that AVAHO can call its own—is set in stone.

Over the past year, Klein has guided AVAHO as it leveraged its remarkable growth in recent years into the landmark creation of a foundation devoted to research. “We want to provide funds to researchers and support access to clinical trials for patients within the VA,” said Klein in an interview after he stepped down as association president at the 2019 AVAHO annual meeting.

Dr. Klein, who works for the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and University of Minnesota in Minneapolis said the foundation is being seeded with $250,000. One goal is to use the foundation to support unique research projects that may not otherwise draw funding, he said.

For example, he said, the foundation could fund a research project by dietitians into severe weight loss in cancer. Or it could support a study by speech pathologists into swallowing in cancer patients.

In addition, he said, the foundation will focus on providing grants to support junior faculty, including researchers who aren’t MDs. And its funds will be used to boost access to clinical trials in cancer.

Klein said he has also focused on strategic planning and developing partnerships with industry and the leadership of both the VA and the National Cancer Institute. “We’re working to come up with unique ways to get people thinking about the barriers to clinical trials and providing better access for veterans.”

He is especially proud of AVAHO’s partnership with National Association of Veterans’ Research and Education Foundations, which includes partial support of a program manager position.

On the corporate front, he said, “we’re going to start offering corporate memberships so that we can form more industry relationships. That’s another new change and a step in our growth as we work to help more veterans and make a bigger difference.”

MINNEAPOLIS -- Oncologist Mark Klein, MD, may have just stepped down as president of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), but his main legacy—a foundation that AVAHO can call its own—is set in stone.

Over the past year, Klein has guided AVAHO as it leveraged its remarkable growth in recent years into the landmark creation of a foundation devoted to research. “We want to provide funds to researchers and support access to clinical trials for patients within the VA,” said Klein in an interview after he stepped down as association president at the 2019 AVAHO annual meeting.

Dr. Klein, who works for the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and University of Minnesota in Minneapolis said the foundation is being seeded with $250,000. One goal is to use the foundation to support unique research projects that may not otherwise draw funding, he said.

For example, he said, the foundation could fund a research project by dietitians into severe weight loss in cancer. Or it could support a study by speech pathologists into swallowing in cancer patients.

In addition, he said, the foundation will focus on providing grants to support junior faculty, including researchers who aren’t MDs. And its funds will be used to boost access to clinical trials in cancer.

Klein said he has also focused on strategic planning and developing partnerships with industry and the leadership of both the VA and the National Cancer Institute. “We’re working to come up with unique ways to get people thinking about the barriers to clinical trials and providing better access for veterans.”

He is especially proud of AVAHO’s partnership with National Association of Veterans’ Research and Education Foundations, which includes partial support of a program manager position.

On the corporate front, he said, “we’re going to start offering corporate memberships so that we can form more industry relationships. That’s another new change and a step in our growth as we work to help more veterans and make a bigger difference.”

MINNEAPOLIS -- Oncologist Mark Klein, MD, may have just stepped down as president of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), but his main legacy—a foundation that AVAHO can call its own—is set in stone.

Over the past year, Klein has guided AVAHO as it leveraged its remarkable growth in recent years into the landmark creation of a foundation devoted to research. “We want to provide funds to researchers and support access to clinical trials for patients within the VA,” said Klein in an interview after he stepped down as association president at the 2019 AVAHO annual meeting.

Dr. Klein, who works for the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and University of Minnesota in Minneapolis said the foundation is being seeded with $250,000. One goal is to use the foundation to support unique research projects that may not otherwise draw funding, he said.

For example, he said, the foundation could fund a research project by dietitians into severe weight loss in cancer. Or it could support a study by speech pathologists into swallowing in cancer patients.

In addition, he said, the foundation will focus on providing grants to support junior faculty, including researchers who aren’t MDs. And its funds will be used to boost access to clinical trials in cancer.

Klein said he has also focused on strategic planning and developing partnerships with industry and the leadership of both the VA and the National Cancer Institute. “We’re working to come up with unique ways to get people thinking about the barriers to clinical trials and providing better access for veterans.”

He is especially proud of AVAHO’s partnership with National Association of Veterans’ Research and Education Foundations, which includes partial support of a program manager position.

On the corporate front, he said, “we’re going to start offering corporate memberships so that we can form more industry relationships. That’s another new change and a step in our growth as we work to help more veterans and make a bigger difference.”

Serum testosterone and estradiol levels associated with current asthma in women

possibly explaining in part the different prevalence of asthma in men and women, according to the findings of a large cross-sectional population based study.

Yueh-Ying Han, PhD, of the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and colleagues investigated the role of free testosterone and estradiol levels and current asthma among adults. The impact of obesity on that association was also examined. The investigators analyzed data from 7,615 adults (3,953 men and 3,662 women) who participated in the 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The data included health interviews, examination components, and laboratory tests on each patient. Serum samples were analyzed by the division of laboratory sciences of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Logistic regression was used for the multivariable analysis of sex hormone levels (as quartiles) and current asthma, and the analysis was done separately on men and women. Pregnant women were excluded, in addition to individuals with incomplete data. The exclusions tended to be Hispanic, former smokers, lower income, and lacking private insurance. The overall prevalence of current asthma in the sample was 9% (6% in men and 13% in women).

Three models were generated based on serum levels in women and in men.

For model 1 (unadjusted for estradiol), women whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 30%-45% significantly lower odds of having current asthma than those whose serum testosterone level was in the lowest quartile. Among men, those whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 12%-13% lower odds for current asthma.

For model 2 (unadjusted for free testosterone), women whose serum estradiol levels were in the third quartile had 34% significantly lower odds of having current asthma than those whose estradiol levels were in the lowest quartile. The findings were similar for men, that is, those whose serum estradiol levels were in the third quartile had 30% lower odds for having asthma, compared with those with in the lowest quartile.

For model 3 (a multivariable model including serum levels of both estradiol and free testosterone), women whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 30% and 44% lower odds of current asthma than those whose serum testosterone levels were in the lowest quartile. But in this multivariable model, the association between serum estradiol and current asthma was not significant. Among men (models 1-3), the magnitude of the estimated effect of serum testosterone and serum estradiol on current asthma was similar to that observed in female participants, but neither serum testosterone nor serum estradiol was significantly associated with current asthma.

The investigators then analyzed the impact of obesity on the relationship between serum hormone levels and obesity. Obesity was defined as body mass index equal to or greater than 30 kg/m2. A total of 1,370 men and 1,653 women were included in this analysis. In multivariable analyses of the obese participants, adjustment without (model 1) and with (model 3) serum estradiol, serum free-testosterone levels in the highest (fourth) quartile were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in obese women. In multivariable analyses without (model 2) and with (model 3), serum estradiol levels above the first quartile were significantly associated with reduced odds of current asthma in obese women.

In contrast to the results in obese women, neither serum free testosterone nor serum estradiol was significantly associated with current asthma in obese men or nonobese women.

Dr. Han and coauthors suggested a possible mechanism of the role of sex hormones in asthma. “Androgens such as testosterone may reduce innate and adaptive immune responses, while estrogen and progesterone may enhance T-helper cell type 2 allergic airway inflammation.”

They concluded: “We found that elevated serum levels of both free testosterone and estradiol were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in obese women, and that elevated levels of serum estradiol were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in nonobese men. Our findings further suggest that sex steroid hormones play a role in known sex differences in asthma among adults.”

One coauthor has received research materials from Merck and GlaxoSmithKline (inhaled steroids), as well as Pharmavite (vitamin D and placebo capsules), to provide medications free of cost to participants in National Institutes for Health–funded studies, unrelated to the current work. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Han Y-Y et al. J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201905-0996OC.

possibly explaining in part the different prevalence of asthma in men and women, according to the findings of a large cross-sectional population based study.

Yueh-Ying Han, PhD, of the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and colleagues investigated the role of free testosterone and estradiol levels and current asthma among adults. The impact of obesity on that association was also examined. The investigators analyzed data from 7,615 adults (3,953 men and 3,662 women) who participated in the 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The data included health interviews, examination components, and laboratory tests on each patient. Serum samples were analyzed by the division of laboratory sciences of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Logistic regression was used for the multivariable analysis of sex hormone levels (as quartiles) and current asthma, and the analysis was done separately on men and women. Pregnant women were excluded, in addition to individuals with incomplete data. The exclusions tended to be Hispanic, former smokers, lower income, and lacking private insurance. The overall prevalence of current asthma in the sample was 9% (6% in men and 13% in women).

Three models were generated based on serum levels in women and in men.

For model 1 (unadjusted for estradiol), women whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 30%-45% significantly lower odds of having current asthma than those whose serum testosterone level was in the lowest quartile. Among men, those whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 12%-13% lower odds for current asthma.

For model 2 (unadjusted for free testosterone), women whose serum estradiol levels were in the third quartile had 34% significantly lower odds of having current asthma than those whose estradiol levels were in the lowest quartile. The findings were similar for men, that is, those whose serum estradiol levels were in the third quartile had 30% lower odds for having asthma, compared with those with in the lowest quartile.

For model 3 (a multivariable model including serum levels of both estradiol and free testosterone), women whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 30% and 44% lower odds of current asthma than those whose serum testosterone levels were in the lowest quartile. But in this multivariable model, the association between serum estradiol and current asthma was not significant. Among men (models 1-3), the magnitude of the estimated effect of serum testosterone and serum estradiol on current asthma was similar to that observed in female participants, but neither serum testosterone nor serum estradiol was significantly associated with current asthma.

The investigators then analyzed the impact of obesity on the relationship between serum hormone levels and obesity. Obesity was defined as body mass index equal to or greater than 30 kg/m2. A total of 1,370 men and 1,653 women were included in this analysis. In multivariable analyses of the obese participants, adjustment without (model 1) and with (model 3) serum estradiol, serum free-testosterone levels in the highest (fourth) quartile were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in obese women. In multivariable analyses without (model 2) and with (model 3), serum estradiol levels above the first quartile were significantly associated with reduced odds of current asthma in obese women.

In contrast to the results in obese women, neither serum free testosterone nor serum estradiol was significantly associated with current asthma in obese men or nonobese women.

Dr. Han and coauthors suggested a possible mechanism of the role of sex hormones in asthma. “Androgens such as testosterone may reduce innate and adaptive immune responses, while estrogen and progesterone may enhance T-helper cell type 2 allergic airway inflammation.”

They concluded: “We found that elevated serum levels of both free testosterone and estradiol were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in obese women, and that elevated levels of serum estradiol were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in nonobese men. Our findings further suggest that sex steroid hormones play a role in known sex differences in asthma among adults.”

One coauthor has received research materials from Merck and GlaxoSmithKline (inhaled steroids), as well as Pharmavite (vitamin D and placebo capsules), to provide medications free of cost to participants in National Institutes for Health–funded studies, unrelated to the current work. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Han Y-Y et al. J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201905-0996OC.

possibly explaining in part the different prevalence of asthma in men and women, according to the findings of a large cross-sectional population based study.

Yueh-Ying Han, PhD, of the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and colleagues investigated the role of free testosterone and estradiol levels and current asthma among adults. The impact of obesity on that association was also examined. The investigators analyzed data from 7,615 adults (3,953 men and 3,662 women) who participated in the 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The data included health interviews, examination components, and laboratory tests on each patient. Serum samples were analyzed by the division of laboratory sciences of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Logistic regression was used for the multivariable analysis of sex hormone levels (as quartiles) and current asthma, and the analysis was done separately on men and women. Pregnant women were excluded, in addition to individuals with incomplete data. The exclusions tended to be Hispanic, former smokers, lower income, and lacking private insurance. The overall prevalence of current asthma in the sample was 9% (6% in men and 13% in women).

Three models were generated based on serum levels in women and in men.

For model 1 (unadjusted for estradiol), women whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 30%-45% significantly lower odds of having current asthma than those whose serum testosterone level was in the lowest quartile. Among men, those whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 12%-13% lower odds for current asthma.

For model 2 (unadjusted for free testosterone), women whose serum estradiol levels were in the third quartile had 34% significantly lower odds of having current asthma than those whose estradiol levels were in the lowest quartile. The findings were similar for men, that is, those whose serum estradiol levels were in the third quartile had 30% lower odds for having asthma, compared with those with in the lowest quartile.

For model 3 (a multivariable model including serum levels of both estradiol and free testosterone), women whose serum testosterone levels were in the second and fourth quartiles had 30% and 44% lower odds of current asthma than those whose serum testosterone levels were in the lowest quartile. But in this multivariable model, the association between serum estradiol and current asthma was not significant. Among men (models 1-3), the magnitude of the estimated effect of serum testosterone and serum estradiol on current asthma was similar to that observed in female participants, but neither serum testosterone nor serum estradiol was significantly associated with current asthma.

The investigators then analyzed the impact of obesity on the relationship between serum hormone levels and obesity. Obesity was defined as body mass index equal to or greater than 30 kg/m2. A total of 1,370 men and 1,653 women were included in this analysis. In multivariable analyses of the obese participants, adjustment without (model 1) and with (model 3) serum estradiol, serum free-testosterone levels in the highest (fourth) quartile were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in obese women. In multivariable analyses without (model 2) and with (model 3), serum estradiol levels above the first quartile were significantly associated with reduced odds of current asthma in obese women.

In contrast to the results in obese women, neither serum free testosterone nor serum estradiol was significantly associated with current asthma in obese men or nonobese women.

Dr. Han and coauthors suggested a possible mechanism of the role of sex hormones in asthma. “Androgens such as testosterone may reduce innate and adaptive immune responses, while estrogen and progesterone may enhance T-helper cell type 2 allergic airway inflammation.”

They concluded: “We found that elevated serum levels of both free testosterone and estradiol were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in obese women, and that elevated levels of serum estradiol were significantly associated with reduced odds of asthma in nonobese men. Our findings further suggest that sex steroid hormones play a role in known sex differences in asthma among adults.”

One coauthor has received research materials from Merck and GlaxoSmithKline (inhaled steroids), as well as Pharmavite (vitamin D and placebo capsules), to provide medications free of cost to participants in National Institutes for Health–funded studies, unrelated to the current work. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Han Y-Y et al. J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201905-0996OC.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

New 2020 Priorities: Expanding AVAHO Outreach and Influence

MINNEAPOLIS -- When William “Bill” Wachsman, MD, PhD, joined the executive board of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology earlier this decade, the organization revolved around its annual meeting. Now, AVAHO is expanding its horizons, and Dr. Wachsman plans to push for a wider focus and greater impact as its new president.

“We’re a group of like-minded individuals who came together about 15 years ago and said we want to take better care of our patients, coordinate our services, and better educate ourselves,” said Dr. Wachsman, a hematologist/oncologist with US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) San Diego Health Care System, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, and Moores Cancer Center. “We’re still dedicated to this mission. Moving forward, I want to improve educational opportunities, encourage our interest groups to develop initiatives, and utilize our foundation to support medical professionals and improve patient care within the VA.”

Dr. Wachsman took over as AVAHO’s president on the last day of the organization’s annual meeting in Minneapolis. He replaces immediate past president Mark Klein, MD, and will serve for 1 year.

According to Dr. Wachsman, AVAHO is unique among cancer/hematology associations because it’s not limited to physicians. “Everyone who’s involved with the care of patients with hematologic or oncologic disease can be involved. You don’t need to be an employee of the VA.”

Indeed, AVAHO’s approximately 800 members include medical oncologists and hematologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pharmacists, nurses, nurse practitioners, advanced practice registered nurses, physician assistants, social workers, cancer registrars, and other allied health professionals.

AVAHO is also unique because it’s not a VA organization. “It’s an association of people are interested in better care for patients at the VA,” Dr. Wachsman said.

Over the next year, Dr. Wachsman hopes to form a community advisory board “that can not only give us advice, but reach out to other associations in the VA and in oncology to spread the word about what we’re doing.” Other forms of outreach can help AVAHO gain influence among policymakers, he said.

As for AVAHO’s foundation, he hopes to bring in funding through grants to support fellowship awards and to help VA sites around the nation develop infrastructure to support clinical trials.

On another national level, he said, AVAHO can improve its relationship with the VA with a goal of promoting honest and productive communication that goes both ways. “You have to get to know each other,” he said, “before you jump into the same pool and begin to swim.”

MINNEAPOLIS -- When William “Bill” Wachsman, MD, PhD, joined the executive board of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology earlier this decade, the organization revolved around its annual meeting. Now, AVAHO is expanding its horizons, and Dr. Wachsman plans to push for a wider focus and greater impact as its new president.

“We’re a group of like-minded individuals who came together about 15 years ago and said we want to take better care of our patients, coordinate our services, and better educate ourselves,” said Dr. Wachsman, a hematologist/oncologist with US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) San Diego Health Care System, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, and Moores Cancer Center. “We’re still dedicated to this mission. Moving forward, I want to improve educational opportunities, encourage our interest groups to develop initiatives, and utilize our foundation to support medical professionals and improve patient care within the VA.”

Dr. Wachsman took over as AVAHO’s president on the last day of the organization’s annual meeting in Minneapolis. He replaces immediate past president Mark Klein, MD, and will serve for 1 year.

According to Dr. Wachsman, AVAHO is unique among cancer/hematology associations because it’s not limited to physicians. “Everyone who’s involved with the care of patients with hematologic or oncologic disease can be involved. You don’t need to be an employee of the VA.”

Indeed, AVAHO’s approximately 800 members include medical oncologists and hematologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pharmacists, nurses, nurse practitioners, advanced practice registered nurses, physician assistants, social workers, cancer registrars, and other allied health professionals.

AVAHO is also unique because it’s not a VA organization. “It’s an association of people are interested in better care for patients at the VA,” Dr. Wachsman said.

Over the next year, Dr. Wachsman hopes to form a community advisory board “that can not only give us advice, but reach out to other associations in the VA and in oncology to spread the word about what we’re doing.” Other forms of outreach can help AVAHO gain influence among policymakers, he said.

As for AVAHO’s foundation, he hopes to bring in funding through grants to support fellowship awards and to help VA sites around the nation develop infrastructure to support clinical trials.

On another national level, he said, AVAHO can improve its relationship with the VA with a goal of promoting honest and productive communication that goes both ways. “You have to get to know each other,” he said, “before you jump into the same pool and begin to swim.”

MINNEAPOLIS -- When William “Bill” Wachsman, MD, PhD, joined the executive board of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology earlier this decade, the organization revolved around its annual meeting. Now, AVAHO is expanding its horizons, and Dr. Wachsman plans to push for a wider focus and greater impact as its new president.

“We’re a group of like-minded individuals who came together about 15 years ago and said we want to take better care of our patients, coordinate our services, and better educate ourselves,” said Dr. Wachsman, a hematologist/oncologist with US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) San Diego Health Care System, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, and Moores Cancer Center. “We’re still dedicated to this mission. Moving forward, I want to improve educational opportunities, encourage our interest groups to develop initiatives, and utilize our foundation to support medical professionals and improve patient care within the VA.”

Dr. Wachsman took over as AVAHO’s president on the last day of the organization’s annual meeting in Minneapolis. He replaces immediate past president Mark Klein, MD, and will serve for 1 year.

According to Dr. Wachsman, AVAHO is unique among cancer/hematology associations because it’s not limited to physicians. “Everyone who’s involved with the care of patients with hematologic or oncologic disease can be involved. You don’t need to be an employee of the VA.”

Indeed, AVAHO’s approximately 800 members include medical oncologists and hematologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pharmacists, nurses, nurse practitioners, advanced practice registered nurses, physician assistants, social workers, cancer registrars, and other allied health professionals.

AVAHO is also unique because it’s not a VA organization. “It’s an association of people are interested in better care for patients at the VA,” Dr. Wachsman said.

Over the next year, Dr. Wachsman hopes to form a community advisory board “that can not only give us advice, but reach out to other associations in the VA and in oncology to spread the word about what we’re doing.” Other forms of outreach can help AVAHO gain influence among policymakers, he said.

As for AVAHO’s foundation, he hopes to bring in funding through grants to support fellowship awards and to help VA sites around the nation develop infrastructure to support clinical trials.

On another national level, he said, AVAHO can improve its relationship with the VA with a goal of promoting honest and productive communication that goes both ways. “You have to get to know each other,” he said, “before you jump into the same pool and begin to swim.”

Q&A with DDW 2019 Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality Improvement Projects session abstract reviewers

The AGA Education & Training Committee sponsors a session during Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) entitled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality Improvement (QI) Projects.” Session participants are selected to give an oral or poster presentation of a quality improvement project they complete during fellowship. The QI project abstracts are peer reviewed and chosen by volunteers from the AGA Young Delegates. We asked several abstract reviewers from the 2019 session for advice on what makes an exceptional QI project and how to make an abstract stand out.

This session will be held again during DDW 2020. Interested participants should submit their abstract to the DDW descriptor GI Fellow-Directed QI Session via the DDW abstract submission site between Oct. 17 and Dec. 1, 2019.

What are the top 3 things that make an exceptional QI project?

Mohammad Bilal, MD, fellow, advanced endoscopy

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Harvard Medical School in Boston

Quality improvement projects are essential to identify areas of improvement in a health care system/institution and to be able to improve them. The best kind of QI projects are those that lead to sustainable positive outcomes. This is not always easy and usually requires a multifocal intervention strategy. In my opinion, the top three things that make an exceptional QI project are:

1. A clear, focused, concise, realistic, and achievable “aim statement,” also known as a “SMART” (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant/Realistic, Time-Bound) aim statement.

2. A project that directly impacts patient-related outcomes.

3. A project that involves multiple members of the health care team in addition to physicians and patients, such as pharmacists, therapists, schedulers, or IT staff.

Chung Sang Tse, MD, gastroenterology fellow

Brown University Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Some of the most impressive QI abstracts that stood out to my fellow cojudges and I were those that employed novel yet widely applicable solutions to common problems, along with empiric data to assess their effects. For example, one of the most highly rated abstracts was one that used an electronic order set to standardize the acute care of inflammatory bowel disease flare in the emergency department and measured the impact on treatment outcomes. Another memorable abstract tested the use of meditation (via an instructional soundtrack) in the endoscopy suite to assess its effect on sedation use, procedural time, and patient comfort; although the results in the abstract did not reach statistical significance, the reviewers rated this abstract favorably for its attempt to improve the endoscopy experience in a low-cost and replicable manner. For this QI category, the reviewers weighed most heavily on a study’s impact, the rigor of methodology, and novelty of the problem/solution.

What advice would you give to prospective authors to make their abstracts stand out?

Michelle Hughes, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine

Section of digestive diseases, Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn.

Turning your hard work from a QI project into a successful abstract can seem daunting. There are a few things to consider to help your findings reach your target audience. First, an abstract should be clear and concise. Limit background content and focus on highlighting your project’s methodology and results. Remember, readers look for a comprehensive overview so they can easily understand what you did and found without a lot of extra content obscuring the main points. Everything in your abstract should tie back to your stated aim. Does the background build a case for your project? Do the results and conclusion clearly answer the hypothesis and/or clinical question? If a reported result does not help answer your question, then it should probably be left out. Another tip is to always carefully follow the guidelines for abstract submission. Ensure you use correct formatting and follow all outlined rules. Ask a colleague to review and proofread your abstract draft prior to submission. Lastly, before you start writing, decide what take-away message or statement makes your project meaningful. Refer to this as you write and finalize your abstract so that you keep your message clear and remain focused. You did the hard work to execute your project – but without an effective abstract, the impact of your work may get lost.

Manol Jovani, MD, MPH, therapeutic endoscopy fellow

Division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore

The abstract is the “elevator pitch” of your year(s)-long work, and as such it must be very carefully crafted. Dedicate specific time to the style and quality of your presentation long before the deadline. As for elevator pitches, first impressions are very important. For an abstract, it begins with the title. Select a declarative title that draws the interest of the reviewers/readers and tells them exactly what to expect, which also accurately represents the main findings. The introduction and aims should be very short and to the point. For example, it is counterproductive to start with “Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are the two major types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).” This does not add any information, states what is obvious to any GI reviewer, uses up 92 characters, and possibly gives a subconscious sense of unoriginality. Throughout the description of your methods/results, use clear language. A well-written abstract will explicitly and concisely state the populations included, statistical analyses performed, and specific outcomes. Make it easy for reviewers to follow along by presenting the results in a logical progression and by striving to use as few acronyms as possible. In addition, less is often more. The abstract should have only one main message, enunciated with the title, evident in the results, and interpreted with the conclusion. If you have additional space, use it to make compelling concluding remarks. As in an elevator pitch, the conclusion is as important as the introduction. Conclude by giving a clear message to the audience/reviewers on what the main findings are and suggest specific implications for future research. Do not end with “more studies are needed,” but rather suggest specifically how these results will influence our future understanding. Finally, know your audience and adapt your presentation to their needs, knowledge, and interests. This includes being mindful of the section to which you are submitting your abstract. An excellent abstract that could have been an oral presentation in one section may end up being a poster in another. Something important to remember about abstracts is that, while the content of the research is the most important part, the quality of its presentation serves to alert the reviewers and readers about it.

Ms. Mietzelfeld is a coordinator of data and training initiatives for the American Gastroenterological Association in Bethesda, Md.

The AGA Education & Training Committee sponsors a session during Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) entitled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality Improvement (QI) Projects.” Session participants are selected to give an oral or poster presentation of a quality improvement project they complete during fellowship. The QI project abstracts are peer reviewed and chosen by volunteers from the AGA Young Delegates. We asked several abstract reviewers from the 2019 session for advice on what makes an exceptional QI project and how to make an abstract stand out.

This session will be held again during DDW 2020. Interested participants should submit their abstract to the DDW descriptor GI Fellow-Directed QI Session via the DDW abstract submission site between Oct. 17 and Dec. 1, 2019.

What are the top 3 things that make an exceptional QI project?

Mohammad Bilal, MD, fellow, advanced endoscopy

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Harvard Medical School in Boston

Quality improvement projects are essential to identify areas of improvement in a health care system/institution and to be able to improve them. The best kind of QI projects are those that lead to sustainable positive outcomes. This is not always easy and usually requires a multifocal intervention strategy. In my opinion, the top three things that make an exceptional QI project are:

1. A clear, focused, concise, realistic, and achievable “aim statement,” also known as a “SMART” (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant/Realistic, Time-Bound) aim statement.

2. A project that directly impacts patient-related outcomes.

3. A project that involves multiple members of the health care team in addition to physicians and patients, such as pharmacists, therapists, schedulers, or IT staff.

Chung Sang Tse, MD, gastroenterology fellow

Brown University Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Some of the most impressive QI abstracts that stood out to my fellow cojudges and I were those that employed novel yet widely applicable solutions to common problems, along with empiric data to assess their effects. For example, one of the most highly rated abstracts was one that used an electronic order set to standardize the acute care of inflammatory bowel disease flare in the emergency department and measured the impact on treatment outcomes. Another memorable abstract tested the use of meditation (via an instructional soundtrack) in the endoscopy suite to assess its effect on sedation use, procedural time, and patient comfort; although the results in the abstract did not reach statistical significance, the reviewers rated this abstract favorably for its attempt to improve the endoscopy experience in a low-cost and replicable manner. For this QI category, the reviewers weighed most heavily on a study’s impact, the rigor of methodology, and novelty of the problem/solution.

What advice would you give to prospective authors to make their abstracts stand out?

Michelle Hughes, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine

Section of digestive diseases, Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn.

Turning your hard work from a QI project into a successful abstract can seem daunting. There are a few things to consider to help your findings reach your target audience. First, an abstract should be clear and concise. Limit background content and focus on highlighting your project’s methodology and results. Remember, readers look for a comprehensive overview so they can easily understand what you did and found without a lot of extra content obscuring the main points. Everything in your abstract should tie back to your stated aim. Does the background build a case for your project? Do the results and conclusion clearly answer the hypothesis and/or clinical question? If a reported result does not help answer your question, then it should probably be left out. Another tip is to always carefully follow the guidelines for abstract submission. Ensure you use correct formatting and follow all outlined rules. Ask a colleague to review and proofread your abstract draft prior to submission. Lastly, before you start writing, decide what take-away message or statement makes your project meaningful. Refer to this as you write and finalize your abstract so that you keep your message clear and remain focused. You did the hard work to execute your project – but without an effective abstract, the impact of your work may get lost.

Manol Jovani, MD, MPH, therapeutic endoscopy fellow

Division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore

The abstract is the “elevator pitch” of your year(s)-long work, and as such it must be very carefully crafted. Dedicate specific time to the style and quality of your presentation long before the deadline. As for elevator pitches, first impressions are very important. For an abstract, it begins with the title. Select a declarative title that draws the interest of the reviewers/readers and tells them exactly what to expect, which also accurately represents the main findings. The introduction and aims should be very short and to the point. For example, it is counterproductive to start with “Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are the two major types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).” This does not add any information, states what is obvious to any GI reviewer, uses up 92 characters, and possibly gives a subconscious sense of unoriginality. Throughout the description of your methods/results, use clear language. A well-written abstract will explicitly and concisely state the populations included, statistical analyses performed, and specific outcomes. Make it easy for reviewers to follow along by presenting the results in a logical progression and by striving to use as few acronyms as possible. In addition, less is often more. The abstract should have only one main message, enunciated with the title, evident in the results, and interpreted with the conclusion. If you have additional space, use it to make compelling concluding remarks. As in an elevator pitch, the conclusion is as important as the introduction. Conclude by giving a clear message to the audience/reviewers on what the main findings are and suggest specific implications for future research. Do not end with “more studies are needed,” but rather suggest specifically how these results will influence our future understanding. Finally, know your audience and adapt your presentation to their needs, knowledge, and interests. This includes being mindful of the section to which you are submitting your abstract. An excellent abstract that could have been an oral presentation in one section may end up being a poster in another. Something important to remember about abstracts is that, while the content of the research is the most important part, the quality of its presentation serves to alert the reviewers and readers about it.

Ms. Mietzelfeld is a coordinator of data and training initiatives for the American Gastroenterological Association in Bethesda, Md.

The AGA Education & Training Committee sponsors a session during Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) entitled “Advancing Clinical Practice: GI Fellow-Directed Quality Improvement (QI) Projects.” Session participants are selected to give an oral or poster presentation of a quality improvement project they complete during fellowship. The QI project abstracts are peer reviewed and chosen by volunteers from the AGA Young Delegates. We asked several abstract reviewers from the 2019 session for advice on what makes an exceptional QI project and how to make an abstract stand out.

This session will be held again during DDW 2020. Interested participants should submit their abstract to the DDW descriptor GI Fellow-Directed QI Session via the DDW abstract submission site between Oct. 17 and Dec. 1, 2019.

What are the top 3 things that make an exceptional QI project?

Mohammad Bilal, MD, fellow, advanced endoscopy

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Harvard Medical School in Boston

Quality improvement projects are essential to identify areas of improvement in a health care system/institution and to be able to improve them. The best kind of QI projects are those that lead to sustainable positive outcomes. This is not always easy and usually requires a multifocal intervention strategy. In my opinion, the top three things that make an exceptional QI project are:

1. A clear, focused, concise, realistic, and achievable “aim statement,” also known as a “SMART” (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant/Realistic, Time-Bound) aim statement.

2. A project that directly impacts patient-related outcomes.

3. A project that involves multiple members of the health care team in addition to physicians and patients, such as pharmacists, therapists, schedulers, or IT staff.

Chung Sang Tse, MD, gastroenterology fellow

Brown University Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Some of the most impressive QI abstracts that stood out to my fellow cojudges and I were those that employed novel yet widely applicable solutions to common problems, along with empiric data to assess their effects. For example, one of the most highly rated abstracts was one that used an electronic order set to standardize the acute care of inflammatory bowel disease flare in the emergency department and measured the impact on treatment outcomes. Another memorable abstract tested the use of meditation (via an instructional soundtrack) in the endoscopy suite to assess its effect on sedation use, procedural time, and patient comfort; although the results in the abstract did not reach statistical significance, the reviewers rated this abstract favorably for its attempt to improve the endoscopy experience in a low-cost and replicable manner. For this QI category, the reviewers weighed most heavily on a study’s impact, the rigor of methodology, and novelty of the problem/solution.

What advice would you give to prospective authors to make their abstracts stand out?

Michelle Hughes, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine

Section of digestive diseases, Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn.

Turning your hard work from a QI project into a successful abstract can seem daunting. There are a few things to consider to help your findings reach your target audience. First, an abstract should be clear and concise. Limit background content and focus on highlighting your project’s methodology and results. Remember, readers look for a comprehensive overview so they can easily understand what you did and found without a lot of extra content obscuring the main points. Everything in your abstract should tie back to your stated aim. Does the background build a case for your project? Do the results and conclusion clearly answer the hypothesis and/or clinical question? If a reported result does not help answer your question, then it should probably be left out. Another tip is to always carefully follow the guidelines for abstract submission. Ensure you use correct formatting and follow all outlined rules. Ask a colleague to review and proofread your abstract draft prior to submission. Lastly, before you start writing, decide what take-away message or statement makes your project meaningful. Refer to this as you write and finalize your abstract so that you keep your message clear and remain focused. You did the hard work to execute your project – but without an effective abstract, the impact of your work may get lost.

Manol Jovani, MD, MPH, therapeutic endoscopy fellow

Division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore

The abstract is the “elevator pitch” of your year(s)-long work, and as such it must be very carefully crafted. Dedicate specific time to the style and quality of your presentation long before the deadline. As for elevator pitches, first impressions are very important. For an abstract, it begins with the title. Select a declarative title that draws the interest of the reviewers/readers and tells them exactly what to expect, which also accurately represents the main findings. The introduction and aims should be very short and to the point. For example, it is counterproductive to start with “Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are the two major types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).” This does not add any information, states what is obvious to any GI reviewer, uses up 92 characters, and possibly gives a subconscious sense of unoriginality. Throughout the description of your methods/results, use clear language. A well-written abstract will explicitly and concisely state the populations included, statistical analyses performed, and specific outcomes. Make it easy for reviewers to follow along by presenting the results in a logical progression and by striving to use as few acronyms as possible. In addition, less is often more. The abstract should have only one main message, enunciated with the title, evident in the results, and interpreted with the conclusion. If you have additional space, use it to make compelling concluding remarks. As in an elevator pitch, the conclusion is as important as the introduction. Conclude by giving a clear message to the audience/reviewers on what the main findings are and suggest specific implications for future research. Do not end with “more studies are needed,” but rather suggest specifically how these results will influence our future understanding. Finally, know your audience and adapt your presentation to their needs, knowledge, and interests. This includes being mindful of the section to which you are submitting your abstract. An excellent abstract that could have been an oral presentation in one section may end up being a poster in another. Something important to remember about abstracts is that, while the content of the research is the most important part, the quality of its presentation serves to alert the reviewers and readers about it.

Ms. Mietzelfeld is a coordinator of data and training initiatives for the American Gastroenterological Association in Bethesda, Md.

Symmetrical Pruriginous Nasal Rash

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

A slang term for volatile alkyl nitrites, poppers are inhaled for recreational purposes. They produce rapid-onset euphoria and sexual arousal, as well as relax anal and vaginal sphincters, facilitating sexual intercourse. Alkyl nitrites initially were developed to treat coronary disease and angina but were replaced by more potent drugs.1 Because of their psychoactive effects and smooth muscle relaxation properties, they are widely used by homosexual and bisexual men.1-3 The term poppers was originated by the sound generated when the glass vials are crushed; currently, they also may be found in other formats.1

Nausea, hypotension, and headache are mild common adverse effects of volatile alkyl nitrites1; cardiac arrhythmia, oxidative hemolysis,4 and poppers maculopathy5,6 with permanent eye damage also have been reported.7 On the skin, volatile alkyl nitrites induce irritant contact dermatitis that heals without scarring, characteristically involving the face and upper thoracic region, as they are volatile vapors.2 However, the reaction can occur elsewhere. There have been reports of contact dermatitis on other locations, such as the thigh or the ankle, due to vials broken while stored in pockets or on the cuff of the socks.1 There also is a report of irritant contact dermatitis manifesting as a penile ulcer.3 Albeit rare, allergic contact dermatitis to volatile alkyl nitrites and other nitrites also can occur.8

The abuse of alkyl nitrites may increase the risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as they may decrease safer sexual practices and increase the propensity to engage in risky sexual behavior. It has been suggested to screen for STIs in patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use. In the past, volatile alkyl nitrites were believed to be a potential vector of human immunodeficiency virus.9 Other popular drugs used in social context or "club drugs," such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, gamma hydroxybutyrate, methamphetamine, and ketamine, do not produce irritant dermatitis as an adverse cutaneous reaction.10 The differential diagnosis in our patient included herpes simplex virus and contagious impetigo1 as well as bullous lupus erythematosus and periorificial dermatitis; however, the clinical picture, acute onset of the reaction, and the patient's medical history were critical in making the correct diagnosis.

The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone and fusidic acid cream twice daily for 7 days with complete response. Sexually transmitted infection screening was unremarkable. We suggest performing an STI workup on patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use.

- Schauber J, Herzinger T. 'Poppers' dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:587-588.

- Foroozan M, Studer M, Splingard B, et al. Facial dermatitis due to inhalation of poppers [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:298-299.

- Latini A, Lora V, Zaccarelli M, et al. Unusual presentation of poppers dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:233-234.

- Shortt J, Polizzotto MN, Opat SS, et al. Oxidative haemolysis due to 'poppers'. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:328.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Naylor SG, et al. Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of 'poppers maculopathy'. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:1479-1486.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Bhatt PR. 'Poppers maculopathy'--an emerging ophthalmic reaction to recreational substance abuse. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:888.

- Vignal-Clermont C, Audo I, Sahel JA, et al. Poppers-associated retinal toxicity. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1583-1585.

- Bos JD, Jansen FC, Timmer JG. Allergic contact dermatitis to amyl nitrite ('poppers'). Contact Dermatitis. 1985;12:109.

- Stratford M, Wilson PD. Agitation effects on microbial cell-cell interactions. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1990;11:1-6.

- Romanelli F, Smith KM, Thornton AC, et al. Poppers: epidemiology and clinical management of inhaled nitrite abuse. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:69-78.

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

A slang term for volatile alkyl nitrites, poppers are inhaled for recreational purposes. They produce rapid-onset euphoria and sexual arousal, as well as relax anal and vaginal sphincters, facilitating sexual intercourse. Alkyl nitrites initially were developed to treat coronary disease and angina but were replaced by more potent drugs.1 Because of their psychoactive effects and smooth muscle relaxation properties, they are widely used by homosexual and bisexual men.1-3 The term poppers was originated by the sound generated when the glass vials are crushed; currently, they also may be found in other formats.1

Nausea, hypotension, and headache are mild common adverse effects of volatile alkyl nitrites1; cardiac arrhythmia, oxidative hemolysis,4 and poppers maculopathy5,6 with permanent eye damage also have been reported.7 On the skin, volatile alkyl nitrites induce irritant contact dermatitis that heals without scarring, characteristically involving the face and upper thoracic region, as they are volatile vapors.2 However, the reaction can occur elsewhere. There have been reports of contact dermatitis on other locations, such as the thigh or the ankle, due to vials broken while stored in pockets or on the cuff of the socks.1 There also is a report of irritant contact dermatitis manifesting as a penile ulcer.3 Albeit rare, allergic contact dermatitis to volatile alkyl nitrites and other nitrites also can occur.8

The abuse of alkyl nitrites may increase the risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as they may decrease safer sexual practices and increase the propensity to engage in risky sexual behavior. It has been suggested to screen for STIs in patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use. In the past, volatile alkyl nitrites were believed to be a potential vector of human immunodeficiency virus.9 Other popular drugs used in social context or "club drugs," such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, gamma hydroxybutyrate, methamphetamine, and ketamine, do not produce irritant dermatitis as an adverse cutaneous reaction.10 The differential diagnosis in our patient included herpes simplex virus and contagious impetigo1 as well as bullous lupus erythematosus and periorificial dermatitis; however, the clinical picture, acute onset of the reaction, and the patient's medical history were critical in making the correct diagnosis.

The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone and fusidic acid cream twice daily for 7 days with complete response. Sexually transmitted infection screening was unremarkable. We suggest performing an STI workup on patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use.

The Diagnosis: Irritant Contact Dermatitis

A slang term for volatile alkyl nitrites, poppers are inhaled for recreational purposes. They produce rapid-onset euphoria and sexual arousal, as well as relax anal and vaginal sphincters, facilitating sexual intercourse. Alkyl nitrites initially were developed to treat coronary disease and angina but were replaced by more potent drugs.1 Because of their psychoactive effects and smooth muscle relaxation properties, they are widely used by homosexual and bisexual men.1-3 The term poppers was originated by the sound generated when the glass vials are crushed; currently, they also may be found in other formats.1

Nausea, hypotension, and headache are mild common adverse effects of volatile alkyl nitrites1; cardiac arrhythmia, oxidative hemolysis,4 and poppers maculopathy5,6 with permanent eye damage also have been reported.7 On the skin, volatile alkyl nitrites induce irritant contact dermatitis that heals without scarring, characteristically involving the face and upper thoracic region, as they are volatile vapors.2 However, the reaction can occur elsewhere. There have been reports of contact dermatitis on other locations, such as the thigh or the ankle, due to vials broken while stored in pockets or on the cuff of the socks.1 There also is a report of irritant contact dermatitis manifesting as a penile ulcer.3 Albeit rare, allergic contact dermatitis to volatile alkyl nitrites and other nitrites also can occur.8

The abuse of alkyl nitrites may increase the risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), as they may decrease safer sexual practices and increase the propensity to engage in risky sexual behavior. It has been suggested to screen for STIs in patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use. In the past, volatile alkyl nitrites were believed to be a potential vector of human immunodeficiency virus.9 Other popular drugs used in social context or "club drugs," such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, gamma hydroxybutyrate, methamphetamine, and ketamine, do not produce irritant dermatitis as an adverse cutaneous reaction.10 The differential diagnosis in our patient included herpes simplex virus and contagious impetigo1 as well as bullous lupus erythematosus and periorificial dermatitis; however, the clinical picture, acute onset of the reaction, and the patient's medical history were critical in making the correct diagnosis.

The patient was treated with topical hydrocortisone and fusidic acid cream twice daily for 7 days with complete response. Sexually transmitted infection screening was unremarkable. We suggest performing an STI workup on patients with history of volatile alkyl nitrite use.

- Schauber J, Herzinger T. 'Poppers' dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:587-588.

- Foroozan M, Studer M, Splingard B, et al. Facial dermatitis due to inhalation of poppers [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:298-299.

- Latini A, Lora V, Zaccarelli M, et al. Unusual presentation of poppers dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:233-234.

- Shortt J, Polizzotto MN, Opat SS, et al. Oxidative haemolysis due to 'poppers'. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:328.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Naylor SG, et al. Adverse ophthalmic reaction in poppers users: case series of 'poppers maculopathy'. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:1479-1486.

- Davies AJ, Kelly SP, Bhatt PR. 'Poppers maculopathy'--an emerging ophthalmic reaction to recreational substance abuse. Eye (Lond). 2012;26:888.

- Vignal-Clermont C, Audo I, Sahel JA, et al. Poppers-associated retinal toxicity. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1583-1585.