User login

For MD-IQ use only

Product Update: Osphena’s NDA, new hysteroscope, TempSure RF technology, Resilient stirrup covers

OSPHENA HAS NEW INDICATION

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.osphena.com/.

NEW 3-IN-1 HYSTEROSCOPE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-hysteroscope/.

SURGICAL RF TECHNOLOGY

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.cynosure.com/tempsure-platform.

PROFESSIONAL FOOT SUPPORTS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.comenitymed.com.

OSPHENA HAS NEW INDICATION

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.osphena.com/.

NEW 3-IN-1 HYSTEROSCOPE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-hysteroscope/.

SURGICAL RF TECHNOLOGY

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.cynosure.com/tempsure-platform.

PROFESSIONAL FOOT SUPPORTS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.comenitymed.com.

OSPHENA HAS NEW INDICATION

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.osphena.com/.

NEW 3-IN-1 HYSTEROSCOPE

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://gynsurgicalsolutions.com/product/omni-hysteroscope/.

SURGICAL RF TECHNOLOGY

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.cynosure.com/tempsure-platform.

PROFESSIONAL FOOT SUPPORTS

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.comenitymed.com.

Use of Mobile Messaging System for Self-Management of Chemotherapy Symptoms in Patients with Advanced Cancer (FULL)

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

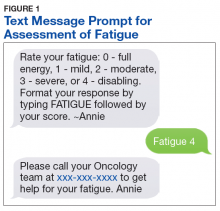

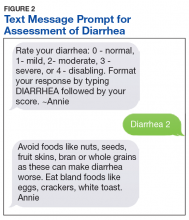

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

1. Bruera E, Dev R. Overview of managing common non-pain symptoms in palliative care. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-managing-common-non-pain-symptoms-in-palliative-care. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

2. Pirschel C. The crucial role of symptom management in cancer care. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/the-crucial-role-of-symptom-management-in-cancer-care. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P. Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):373-382.

4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

5. Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Patel RA, Halpenny B, McReynolds J. Exposure to a patient-centered, Web-based intervention for managing cancer symptom and quality of life issues: Impact on symptom distress. J Med Internet Res. 2015;3(7):e136.

6. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615

7. Kamdar MM, Centi AJ, Fischer N, Jetwani K. A randomized controlled trial of a novel artificial-intelligence based smartphone application to optimize the management of cancer-related pain. Presented at: 2018 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium; November 16-17, 2018; San Diego, CA.

8. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546.

9. Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Proof of concept of a mobile health short message service text message intervention that promotes adherence to oral anticancer agent medications: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(6):497-506.

10. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):3370-351.

11. Kim AR, Park HA. Web-based self-management support intervention for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:142-147.

12. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al; PROMPT-Care Program Group. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

13. Moradian S, Krzyzanowska MK, Maguire R, et al. Usability evaluation of a mobile phone-based system for remote monitoring and management of chemotherapy-related side effects in cancer patients: Mixed methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2018;4(2): e10932.

14. Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, et al. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e219.

15. The Health Foundation. Overview of Florence simple telehealth text messaging system. https://www.health.org.uk/article/overview-of-the-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system. Accessed July 31, 2019.

16. Bragg DD, Edis H, Clark S, Parsons SL, Perumpalath B…Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Development of a telehealth monitoring service after colorectal surgery: a feasibility study. 2017;9(9):193-199.

17. O’Connell P. Annie-the VA’s self-care game changer. http://www.simple.uk.net/home/blog/blogcontent/annie-thevasself-caregamechanger. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2019.

18. Kataria L, Sundahl, C, Skalina L, et al. Text message reminders and intensive education improves positive airway pressure compliance and cognition in veterans with traumatic brain injury and obstructive sleep apnea: ANNIE pilot study (P1.097). Neurology, 2018; 90(suppl 15):P1.097.

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

Cancer and cancer-related treatment can cause a myriad of adverse effects.1,2 Early identification and management of these symptoms is paramount to the success of cancer treatment completion; however, clinic and telephonic strategies for addressing symptoms often result in delays in care.1 New strategies for patient engagement in the management of cancer and treatment-related symptoms are needed.

The use of online self-management tools can result in improvement in symptoms, reduce cancer symptom distress, improve quality-of-life, and improve medication adherence.3-9 A meta-analysis concluded that online interventions showed promise, but optimizing interventions would require additional research.10 Another meta-analysis found that online self-management was effective in managing several symptoms.11 An e-health method of collecting patient self-reported symptoms has been found to be acceptable to patients and feasible for use.12-14 We postulated that a mobile text messaging strategy may be an effective modality for augmenting symptom management for cancer patients in real time.

In the US Departmant of Veterans Affairs (VA), “Annie,” a self-care tool utilizing a text-messaging system has been implemented. Annie was developed modeling “Flo,” a messaging system in the United Kingdom that has been used for case management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, stress incontinence, asthma, as a medication reminder tool, and to provide support for weight loss or post-operatively.15-17 Using Annie in the US, veterans have the ability to receive and track health information. Use of the Annie program has demonstrated improved continuous positive airway pressure monitor utilization in veterans with traumatic brain injury.18 Other uses within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) include assisting patients with anger management, liver disease, anxiety, asthma, diabetes, HIV, hypertension, weight loss, and smoking cessation.

Methods

The Hematology/Oncology division of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System (MVAHCS) is a tertiary care facility that administers about 260 new chemotherapy regimens annually. The MVAHCS interdisciplinary hematology/oncology group initiated a quality improvement project to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and experience of tailoring the Annie tool for self-management of cancer symptoms. The group consisted of 2 physicians, 3 advanced practice registered nurses, 1 physician assistant, 2 registered nurses, and 2 Annie program team members.

We first created a symptom management pilot protocol as a result of multidisciplinary team discussions. Examples of discussion points for consideration included, but were not limited to, timing of texts, amount of information to ask for and provide, what potential symptoms to consider, and which patient population to pilot first.

The initial protocol was agreed upon and is as follows: Patients were sent text messages twice daily Monday through Friday, and asked to rate 2 symptoms per day, using a severity scale of 0 to 4 (absent, mild, moderate, severe, or disabling): nausea/vomiting, mouth sores, fatigue (Figure 1), trouble breathing, appetite, constipation, diarrhea (Figure 2), numbness/tingling, pain. In addition, patients were asked whether they had had a fever or not. Based on their response to the symptom inquiries, the patient received an automated text response. The text may have provided positive affirmation that they were doing well, given them advice for home management, referred them to an educational hyperlink, asked them to call a direct number to the clinic, or instructed them to report directly to the emergency department (ED). Patients could input a particular symptom on any day, even if they were not specifically asked about that symptom on that day. Patients also were instructed to text, only if it was not an inconvenience to them, as we wanted the intervention to be helpful and not a burden.

Results

Through screening new patient consults or those referred for chemotherapy education, 15 male veterans enrolled in the symptom monitoring program over an 8 month period. There were additional patients who were not offered the program or chose not to participate; often due to not having texting capabilities on their phone or not liking the texting feature. The majority of those who participated in the program (n = 14) were enrolled at the start of Cycle 1; the other patient was enrolled at the start of Cycle 2. Patients were enrolled an average of 89 days (range 8-204). Average response rate was 84.2% (range 30-100%).

Although symptoms were not reviewed in real time, we reviewed responses to determine the utilization of the instructions given for the program. No veteran had 0 symptoms reported. There were numerous occurrences of a score of 1 or 2. Many of these patients had baseline symptoms due to their underlying cancer. A score of 3 or 4 on the system prompted the patient to call the clinic or go to the ED. Seven patients (some with multiple occurrences) were prompted to call; only 4 of these made the follow-up call to the clinic. All were offered a same day visit, but each declined. Only 1 patient reported a symptom on a day not prompted for that symptom. Symptoms that were reported are listed in order of frequency: fatigue, appetite loss, numbness, pain, mouth sore, and breathing difficulty. There were no visits to the ED.

Program Evaluation

An evaluation was conducted 30 to 60 days after program enrollment. We elicited feedback to determine who was reading and responding to the text message: the patient, a family member, or a caregiver; whether they found the prompts helpful and took action; how they felt about the number of texts; if they felt the program was helpful; and any other feedback that would improve the program. In general, the patients (8) answered the texts independently. In 4 cases, the spouse answered the texts, and 3 patients answered the texts together with their spouses. Most patients (11) found the amount of texting to be “just right.” However, 3 found it to be too many texts and 1 didn’t find the amount of texting to be enough.

Three veterans did not have enough symptoms to feel the program was of benefit to them, but they did feel it would have been helpful if they had been more symptomatic. One veteran recalled taking loperamide as needed, as a result of prompting. No veterans felt as though the texting feature was difficult to use; and overall, were very positive about the program. Several appreciated receiving messages that validated when they were doing well, and they felt empowered by self-management. One of the spouses was a registered nurse and found the information too basic to be of use.

Discussion

Initial evaluation of the program via survey found no technology challenges. Patients have been very positive about the program including ease of use, appreciation of messages that validated when they were doing well, empowerment of self-management, and some utilization of the texting advice for symptom management. Educational hyperlinks for constipation, fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea/vomiting were added after this evaluation, and patients felt that these additions provided a higher level of education.

Staff time for this intervention was minimal. A nurse navigator offered the texting program to the patient during chemotherapy education, along with some instructions, which generally took about 5 minutes. One of the Annie program staff enrolled the patient. From that point forward, this was a self-management tool, beyond checking to ensure that the patient was successful in starting the program and evaluating use for the purposes of this quality improvement project. This self-management tool did not replace any other mechanism that a patient would normally have in our department for seeking help for symptoms. The MVAHSC typical process for symptom management is to have patients call a 24/7 nurse line. If the triage nurse feels the symptoms are related to the patient’s cancer or cancer treatment, they are referred to the physician assistant who is assigned to take those calls and has the option to see the patient the same day. Patients could continue to call the nurse line or speak with providers at the next appointment at their discretion.

Conclusion

Although Annie has the option of using either text messaging or a mobile application, this project only utilized text messaging. The study by Basch and colleagues was the closest randomized trial we could identify to compare to our quality improvement intervention.5 The 2 main, distinct differences were that Basch and colleagues utilized online monitoring; and nurses were utilized to screen and intervene on responses, as appropriate.

The ability of our program to text patients without the use of an application or tablet, may enable more patients to participate due to ease of use. There would be no increased in expected workload for clinical staff, and may lead to decreased call burden. Since our program is automated, while still providing patients with the option to call and speak with a staff member as needed, this is a cost-effective, first-line option for symptom management for those experiencing cancer-related symptoms. We believe this text messaging tool can have system wide use and benefit throughout the VHA.

1. Bruera E, Dev R. Overview of managing common non-pain symptoms in palliative care. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-managing-common-non-pain-symptoms-in-palliative-care. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

2. Pirschel C. The crucial role of symptom management in cancer care. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/the-crucial-role-of-symptom-management-in-cancer-care. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P. Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):373-382.

4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

5. Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Patel RA, Halpenny B, McReynolds J. Exposure to a patient-centered, Web-based intervention for managing cancer symptom and quality of life issues: Impact on symptom distress. J Med Internet Res. 2015;3(7):e136.

6. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615

7. Kamdar MM, Centi AJ, Fischer N, Jetwani K. A randomized controlled trial of a novel artificial-intelligence based smartphone application to optimize the management of cancer-related pain. Presented at: 2018 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium; November 16-17, 2018; San Diego, CA.

8. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546.

9. Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Proof of concept of a mobile health short message service text message intervention that promotes adherence to oral anticancer agent medications: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(6):497-506.

10. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):3370-351.

11. Kim AR, Park HA. Web-based self-management support intervention for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:142-147.

12. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al; PROMPT-Care Program Group. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

13. Moradian S, Krzyzanowska MK, Maguire R, et al. Usability evaluation of a mobile phone-based system for remote monitoring and management of chemotherapy-related side effects in cancer patients: Mixed methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2018;4(2): e10932.

14. Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, et al. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e219.

15. The Health Foundation. Overview of Florence simple telehealth text messaging system. https://www.health.org.uk/article/overview-of-the-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system. Accessed July 31, 2019.

16. Bragg DD, Edis H, Clark S, Parsons SL, Perumpalath B…Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Development of a telehealth monitoring service after colorectal surgery: a feasibility study. 2017;9(9):193-199.

17. O’Connell P. Annie-the VA’s self-care game changer. http://www.simple.uk.net/home/blog/blogcontent/annie-thevasself-caregamechanger. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2019.

18. Kataria L, Sundahl, C, Skalina L, et al. Text message reminders and intensive education improves positive airway pressure compliance and cognition in veterans with traumatic brain injury and obstructive sleep apnea: ANNIE pilot study (P1.097). Neurology, 2018; 90(suppl 15):P1.097.

1. Bruera E, Dev R. Overview of managing common non-pain symptoms in palliative care. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-managing-common-non-pain-symptoms-in-palliative-care. Updated June 12, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

2. Pirschel C. The crucial role of symptom management in cancer care. https://voice.ons.org/news-and-views/the-crucial-role-of-symptom-management-in-cancer-care. Published December 14, 2017. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. Adam R, Burton CD, Bond CM, de Bruin M, Murchie P. Can patient-reported measurements of pain be used to improve cancer pain management? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(4):373-382.

4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565.

5. Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Patel RA, Halpenny B, McReynolds J. Exposure to a patient-centered, Web-based intervention for managing cancer symptom and quality of life issues: Impact on symptom distress. J Med Internet Res. 2015;3(7):e136.

6. Kolb NA, Smith AG, Singleton JR, et al. Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptom management: a randomized trial of an automated symptom-monitoring system paired with nurse practitioner follow-up. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1607-1615

7. Kamdar MM, Centi AJ, Fischer N, Jetwani K. A randomized controlled trial of a novel artificial-intelligence based smartphone application to optimize the management of cancer-related pain. Presented at: 2018 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium; November 16-17, 2018; San Diego, CA.

8. Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):537-546.

9. Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Proof of concept of a mobile health short message service text message intervention that promotes adherence to oral anticancer agent medications: a randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(6):497-506.

10. Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, Ingadottir B, Hafsteinsdottir EJG. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):3370-351.

11. Kim AR, Park HA. Web-based self-management support intervention for cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:142-147.

12. Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al; PROMPT-Care Program Group. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

13. Moradian S, Krzyzanowska MK, Maguire R, et al. Usability evaluation of a mobile phone-based system for remote monitoring and management of chemotherapy-related side effects in cancer patients: Mixed methods study. JMIR Cancer. 2018;4(2): e10932.

14. Voruganti T, Grunfeld E, Jamieson T, et al. My team of care study: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a web-based communication tool for collaborative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e219.

15. The Health Foundation. Overview of Florence simple telehealth text messaging system. https://www.health.org.uk/article/overview-of-the-florence-simple-telehealth-text-messaging-system. Accessed July 31, 2019.

16. Bragg DD, Edis H, Clark S, Parsons SL, Perumpalath B…Maxwell-Armstrong CA. Development of a telehealth monitoring service after colorectal surgery: a feasibility study. 2017;9(9):193-199.

17. O’Connell P. Annie-the VA’s self-care game changer. http://www.simple.uk.net/home/blog/blogcontent/annie-thevasself-caregamechanger. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed August 2, 2019.

18. Kataria L, Sundahl, C, Skalina L, et al. Text message reminders and intensive education improves positive airway pressure compliance and cognition in veterans with traumatic brain injury and obstructive sleep apnea: ANNIE pilot study (P1.097). Neurology, 2018; 90(suppl 15):P1.097.

Of God and Country

Whoever seeks to set one religion against another seeks to destroy all religion.1

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Recently, a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) colleague knowing of my background in religious studies asked me what I thought of the recent change in VA religious policy. VA Secretary Robert Wilke had announced on July 3 that VA was revising its policies on religious symbols at all VA facilities and religious and pastoral care in the Veterans Health Administration, respectively.2,3 A news release from the VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs designated the changes as an “overhaul.”4

The revisions in these VA directives are designed to address confusion and inconsistency regarding displays of religious matters, not just between different VA medical centers (VAMCs) but even within a single facility. From my decades as a federal practitioner and ethicist, I can attest to the confusion. I have heard or read from staff and leaders of VAMCs everything from “VA prohibits all religious symbols so take that Christmas tree down” to “it is fine to host holiday parties complete with decorations.” There certainly was a need for clarity, transparency, and fairness in VA policy regarding religious and spiritual symbolism. This editorial will discuss how, why, and whether the policy accomplishes this organizational ethics purpose.

The new policies have 3 aims: (1) to permit VA facilities to publicly display religious content in appropriate circumstances; (2) to allow patients and their guests to request and receive religious literature, sacred texts, and spiritual symbols during visits to VA chapels or episodes of treatment; and (3) to permit VA facilities to receive and dispense donations of religious literature, cards, and symbols to VA patrons under appropriate circumstances or when they ask for them.

Secretary Wilke announced the aim of the revised directives: “These important changes will bring simplicity and clarity to our policies governing religious and spiritual symbols, helping ensure we are consistently complying with the First Amendment to the US Constitution at thousands of facilities across the department.”4 As with most US Department of Defense (DoD) and VA decisions about potentially controversial issues, this one has a backstory involving 2 high-profile court cases that provide a deeper understanding of the subtext of the policy change.

In February 2019, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments for The American Legion v American Humanist Association, the most recent of a long line of important cases about the First Amendment and its freedom of religion guarantee.5 This case involved veterans—although not the VA or DoD—and is of prima facie interest for those invested or interested in the VA’s position on religion. A 40-foot cross had stood in a veteran memorial park in Bladensburg, Maryland, for decades. In the 1960s the park became the property of the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission (MNCPPC), which assumed the responsibility for upkeep for the cross at considerable expense. The American Humanist Association, an organization advocating for church-state separation, sued the MNCPPC on the grounds it violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment by promoting Christianity as a federally supported religion.

The US District Court found in favor of MNCPPC, but an appeals court reversed that decision. The American Legion, a major force in VA politics, joined MNCPPC to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. The Court issued a 7 to 2 decision, which ruled that the cross did not violate the establishment clause. Even though the cross began as religious symbol, with the passage of time the High Court opined that the cross had become a historic memorial honoring those who fought in the First World War, which rose above its purely Christian meaning.5

The American Legion website explicitly credited their success before the Supreme Court as the impetus for VA policy changes.6 Hence, from the perspective of VA leadership, this wider latitude for religious expression, which the revised policy now allows, renderings VA practice consonant with the authoritative interpreters of constitutional law—the highest court in the land.

Of course, on a question that has been so divisive for the nation since its founding, there are many who protest this extension of religious liberty in the federal health care system. Veterans stand tall on both sides of this divide. In May 2019 a US Air Force veteran filed a federal lawsuit against the Manchester VAMC director asking the court to remove a Christian Bible from a public display.

Air Force Times compared the resulting melee to actual combat!7 As with the first case, such legal battles are ripe territory for advocacy and lobbying organizations of all political stripes to weigh in while promoting their own ideologic agendas. The Military Religious Freedom Foundation assumed the mantle on behalf of the Air Force veteran in the Manchester suit. The news media reported that the plaintiff in the case identified himself as a committed Christian. According to the news reports, what worried this veteran was the same thing that troubled President Roosevelt in 1940: By featuring the Christian Bible, the VA excluded other faith groups.1 Other veterans and some veteran religious organizations objected just as strenuously to its removal, likely done to reduce potential for violence. Veterans opposing the inclusion of the Bible in the display also grounded their arguments in the First Amendment clause that prohibits the federal government from establishing or favoring any religion.8

Presumptively, displays of such religious symbols may well be supported in VA policy as a protected expression of religion, which Secretary Wilke stated was the other primary aim of the revisions. “We want to make sure that all of our veterans and their families feel welcome at VA, no matter their religious beliefs. Protecting religious liberty is a key part of how we accomplish that goal.”4

In the middle of this sensitive controversy are the many veterans and their families that third parties—for profit, for politics, for publicity—have far too often manipulated for their own purposes. If you want to get an idea of the scope of these diverse stakeholders, just peruse the amicus briefs submitted to the Supreme Court on both sides of the issues in The American Legion v American Humanist Association.8

VA data show that veterans while being more religious than the general public are religiously diverse: 2015 data on the religion of veterans in every state listed 13 different faith communities.9 My response to the colleague who asked me about my opinion of the VA policies changes was based on the background narrative recounted here. My rsponse, in light of Roosevelt’s concern and this snippet of a much larger swath of legal machinations, is the change in the VA policy is reasonable as long as it “has room for the expression of those whose trust is in God, in country, in neither, and in both.” We know from research that religion is a strength and a support to many veterans and that spirituality as an aspect of psychological therapies and pastoral counseling has shown healing power for the wounds of war.10 Yet we also know that religiously based hatred and discrimination are among the most divisive and destructive forces that threaten our democracy. Let’s all hope—and those who pray do so—that these policy changes deter the latter and promote the former.

1. Roosevelt FD. The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. 1940 volume, War-and Aid to Democracies: With a Special Introduction and Explanatory Notes by President Roosevelt [Book 1]. New York: Macmillan; 1941:537.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VA Directive 0022: Religious symbols in VA facilities. https://www.va.gov/vapubs/viewPublication.asp?Pub_ID=849. Published July 3, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. SVA Directive 1111(1): Spiritual and pastoral care in the Veterans Health Administration. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=4299. Published November 22, 2016. Amended July 3, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

4. VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA overhauls religious and spiritual symbol policies to protect religious liberty. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5279. Updated July 3, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

5. Oyez. The American Legion v American Humanist Association. www.oyez.org/cases/2018/17-1717. Accessed July 16, 2019.

6. The American Legion. Legion salutes VA policy change for religious freedom. https://www.legion.org/honor/246151/legion-salutes-va-policy-change-victory-religious-freedom. Published July 03, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

7. Miller K. Lawsuit filed over Bible display at New Hampshire VA Hospital; uproar ensues. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2019/05/07/lawsuit-filed-over-bible-display-at-new-hampshire-va-hospital-uproar-ensues. Published May 7, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

8. Scotusblog. The American Legion v American Humanist Association. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/the-american-legion-v-american-humanist-association. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans religions by state 2015. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Veterans_Religion_by_State.xlsx. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Smothers ZPW. Koenig HG. Spiritual interventions in veterans with PTSD: a systematic review. J Relig Health. 2018;57(5):2033-2048.

Whoever seeks to set one religion against another seeks to destroy all religion.1

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Recently, a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) colleague knowing of my background in religious studies asked me what I thought of the recent change in VA religious policy. VA Secretary Robert Wilke had announced on July 3 that VA was revising its policies on religious symbols at all VA facilities and religious and pastoral care in the Veterans Health Administration, respectively.2,3 A news release from the VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs designated the changes as an “overhaul.”4

The revisions in these VA directives are designed to address confusion and inconsistency regarding displays of religious matters, not just between different VA medical centers (VAMCs) but even within a single facility. From my decades as a federal practitioner and ethicist, I can attest to the confusion. I have heard or read from staff and leaders of VAMCs everything from “VA prohibits all religious symbols so take that Christmas tree down” to “it is fine to host holiday parties complete with decorations.” There certainly was a need for clarity, transparency, and fairness in VA policy regarding religious and spiritual symbolism. This editorial will discuss how, why, and whether the policy accomplishes this organizational ethics purpose.

The new policies have 3 aims: (1) to permit VA facilities to publicly display religious content in appropriate circumstances; (2) to allow patients and their guests to request and receive religious literature, sacred texts, and spiritual symbols during visits to VA chapels or episodes of treatment; and (3) to permit VA facilities to receive and dispense donations of religious literature, cards, and symbols to VA patrons under appropriate circumstances or when they ask for them.

Secretary Wilke announced the aim of the revised directives: “These important changes will bring simplicity and clarity to our policies governing religious and spiritual symbols, helping ensure we are consistently complying with the First Amendment to the US Constitution at thousands of facilities across the department.”4 As with most US Department of Defense (DoD) and VA decisions about potentially controversial issues, this one has a backstory involving 2 high-profile court cases that provide a deeper understanding of the subtext of the policy change.

In February 2019, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments for The American Legion v American Humanist Association, the most recent of a long line of important cases about the First Amendment and its freedom of religion guarantee.5 This case involved veterans—although not the VA or DoD—and is of prima facie interest for those invested or interested in the VA’s position on religion. A 40-foot cross had stood in a veteran memorial park in Bladensburg, Maryland, for decades. In the 1960s the park became the property of the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission (MNCPPC), which assumed the responsibility for upkeep for the cross at considerable expense. The American Humanist Association, an organization advocating for church-state separation, sued the MNCPPC on the grounds it violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment by promoting Christianity as a federally supported religion.

The US District Court found in favor of MNCPPC, but an appeals court reversed that decision. The American Legion, a major force in VA politics, joined MNCPPC to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. The Court issued a 7 to 2 decision, which ruled that the cross did not violate the establishment clause. Even though the cross began as religious symbol, with the passage of time the High Court opined that the cross had become a historic memorial honoring those who fought in the First World War, which rose above its purely Christian meaning.5

The American Legion website explicitly credited their success before the Supreme Court as the impetus for VA policy changes.6 Hence, from the perspective of VA leadership, this wider latitude for religious expression, which the revised policy now allows, renderings VA practice consonant with the authoritative interpreters of constitutional law—the highest court in the land.

Of course, on a question that has been so divisive for the nation since its founding, there are many who protest this extension of religious liberty in the federal health care system. Veterans stand tall on both sides of this divide. In May 2019 a US Air Force veteran filed a federal lawsuit against the Manchester VAMC director asking the court to remove a Christian Bible from a public display.

Air Force Times compared the resulting melee to actual combat!7 As with the first case, such legal battles are ripe territory for advocacy and lobbying organizations of all political stripes to weigh in while promoting their own ideologic agendas. The Military Religious Freedom Foundation assumed the mantle on behalf of the Air Force veteran in the Manchester suit. The news media reported that the plaintiff in the case identified himself as a committed Christian. According to the news reports, what worried this veteran was the same thing that troubled President Roosevelt in 1940: By featuring the Christian Bible, the VA excluded other faith groups.1 Other veterans and some veteran religious organizations objected just as strenuously to its removal, likely done to reduce potential for violence. Veterans opposing the inclusion of the Bible in the display also grounded their arguments in the First Amendment clause that prohibits the federal government from establishing or favoring any religion.8

Presumptively, displays of such religious symbols may well be supported in VA policy as a protected expression of religion, which Secretary Wilke stated was the other primary aim of the revisions. “We want to make sure that all of our veterans and their families feel welcome at VA, no matter their religious beliefs. Protecting religious liberty is a key part of how we accomplish that goal.”4

In the middle of this sensitive controversy are the many veterans and their families that third parties—for profit, for politics, for publicity—have far too often manipulated for their own purposes. If you want to get an idea of the scope of these diverse stakeholders, just peruse the amicus briefs submitted to the Supreme Court on both sides of the issues in The American Legion v American Humanist Association.8

VA data show that veterans while being more religious than the general public are religiously diverse: 2015 data on the religion of veterans in every state listed 13 different faith communities.9 My response to the colleague who asked me about my opinion of the VA policies changes was based on the background narrative recounted here. My rsponse, in light of Roosevelt’s concern and this snippet of a much larger swath of legal machinations, is the change in the VA policy is reasonable as long as it “has room for the expression of those whose trust is in God, in country, in neither, and in both.” We know from research that religion is a strength and a support to many veterans and that spirituality as an aspect of psychological therapies and pastoral counseling has shown healing power for the wounds of war.10 Yet we also know that religiously based hatred and discrimination are among the most divisive and destructive forces that threaten our democracy. Let’s all hope—and those who pray do so—that these policy changes deter the latter and promote the former.

Whoever seeks to set one religion against another seeks to destroy all religion.1

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Recently, a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) colleague knowing of my background in religious studies asked me what I thought of the recent change in VA religious policy. VA Secretary Robert Wilke had announced on July 3 that VA was revising its policies on religious symbols at all VA facilities and religious and pastoral care in the Veterans Health Administration, respectively.2,3 A news release from the VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs designated the changes as an “overhaul.”4

The revisions in these VA directives are designed to address confusion and inconsistency regarding displays of religious matters, not just between different VA medical centers (VAMCs) but even within a single facility. From my decades as a federal practitioner and ethicist, I can attest to the confusion. I have heard or read from staff and leaders of VAMCs everything from “VA prohibits all religious symbols so take that Christmas tree down” to “it is fine to host holiday parties complete with decorations.” There certainly was a need for clarity, transparency, and fairness in VA policy regarding religious and spiritual symbolism. This editorial will discuss how, why, and whether the policy accomplishes this organizational ethics purpose.

The new policies have 3 aims: (1) to permit VA facilities to publicly display religious content in appropriate circumstances; (2) to allow patients and their guests to request and receive religious literature, sacred texts, and spiritual symbols during visits to VA chapels or episodes of treatment; and (3) to permit VA facilities to receive and dispense donations of religious literature, cards, and symbols to VA patrons under appropriate circumstances or when they ask for them.

Secretary Wilke announced the aim of the revised directives: “These important changes will bring simplicity and clarity to our policies governing religious and spiritual symbols, helping ensure we are consistently complying with the First Amendment to the US Constitution at thousands of facilities across the department.”4 As with most US Department of Defense (DoD) and VA decisions about potentially controversial issues, this one has a backstory involving 2 high-profile court cases that provide a deeper understanding of the subtext of the policy change.

In February 2019, the US Supreme Court heard oral arguments for The American Legion v American Humanist Association, the most recent of a long line of important cases about the First Amendment and its freedom of religion guarantee.5 This case involved veterans—although not the VA or DoD—and is of prima facie interest for those invested or interested in the VA’s position on religion. A 40-foot cross had stood in a veteran memorial park in Bladensburg, Maryland, for decades. In the 1960s the park became the property of the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission (MNCPPC), which assumed the responsibility for upkeep for the cross at considerable expense. The American Humanist Association, an organization advocating for church-state separation, sued the MNCPPC on the grounds it violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment by promoting Christianity as a federally supported religion.

The US District Court found in favor of MNCPPC, but an appeals court reversed that decision. The American Legion, a major force in VA politics, joined MNCPPC to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. The Court issued a 7 to 2 decision, which ruled that the cross did not violate the establishment clause. Even though the cross began as religious symbol, with the passage of time the High Court opined that the cross had become a historic memorial honoring those who fought in the First World War, which rose above its purely Christian meaning.5

The American Legion website explicitly credited their success before the Supreme Court as the impetus for VA policy changes.6 Hence, from the perspective of VA leadership, this wider latitude for religious expression, which the revised policy now allows, renderings VA practice consonant with the authoritative interpreters of constitutional law—the highest court in the land.

Of course, on a question that has been so divisive for the nation since its founding, there are many who protest this extension of religious liberty in the federal health care system. Veterans stand tall on both sides of this divide. In May 2019 a US Air Force veteran filed a federal lawsuit against the Manchester VAMC director asking the court to remove a Christian Bible from a public display.

Air Force Times compared the resulting melee to actual combat!7 As with the first case, such legal battles are ripe territory for advocacy and lobbying organizations of all political stripes to weigh in while promoting their own ideologic agendas. The Military Religious Freedom Foundation assumed the mantle on behalf of the Air Force veteran in the Manchester suit. The news media reported that the plaintiff in the case identified himself as a committed Christian. According to the news reports, what worried this veteran was the same thing that troubled President Roosevelt in 1940: By featuring the Christian Bible, the VA excluded other faith groups.1 Other veterans and some veteran religious organizations objected just as strenuously to its removal, likely done to reduce potential for violence. Veterans opposing the inclusion of the Bible in the display also grounded their arguments in the First Amendment clause that prohibits the federal government from establishing or favoring any religion.8

Presumptively, displays of such religious symbols may well be supported in VA policy as a protected expression of religion, which Secretary Wilke stated was the other primary aim of the revisions. “We want to make sure that all of our veterans and their families feel welcome at VA, no matter their religious beliefs. Protecting religious liberty is a key part of how we accomplish that goal.”4

In the middle of this sensitive controversy are the many veterans and their families that third parties—for profit, for politics, for publicity—have far too often manipulated for their own purposes. If you want to get an idea of the scope of these diverse stakeholders, just peruse the amicus briefs submitted to the Supreme Court on both sides of the issues in The American Legion v American Humanist Association.8

VA data show that veterans while being more religious than the general public are religiously diverse: 2015 data on the religion of veterans in every state listed 13 different faith communities.9 My response to the colleague who asked me about my opinion of the VA policies changes was based on the background narrative recounted here. My rsponse, in light of Roosevelt’s concern and this snippet of a much larger swath of legal machinations, is the change in the VA policy is reasonable as long as it “has room for the expression of those whose trust is in God, in country, in neither, and in both.” We know from research that religion is a strength and a support to many veterans and that spirituality as an aspect of psychological therapies and pastoral counseling has shown healing power for the wounds of war.10 Yet we also know that religiously based hatred and discrimination are among the most divisive and destructive forces that threaten our democracy. Let’s all hope—and those who pray do so—that these policy changes deter the latter and promote the former.

1. Roosevelt FD. The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. 1940 volume, War-and Aid to Democracies: With a Special Introduction and Explanatory Notes by President Roosevelt [Book 1]. New York: Macmillan; 1941:537.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VA Directive 0022: Religious symbols in VA facilities. https://www.va.gov/vapubs/viewPublication.asp?Pub_ID=849. Published July 3, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. SVA Directive 1111(1): Spiritual and pastoral care in the Veterans Health Administration. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=4299. Published November 22, 2016. Amended July 3, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

4. VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA overhauls religious and spiritual symbol policies to protect religious liberty. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5279. Updated July 3, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

5. Oyez. The American Legion v American Humanist Association. www.oyez.org/cases/2018/17-1717. Accessed July 16, 2019.

6. The American Legion. Legion salutes VA policy change for religious freedom. https://www.legion.org/honor/246151/legion-salutes-va-policy-change-victory-religious-freedom. Published July 03, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

7. Miller K. Lawsuit filed over Bible display at New Hampshire VA Hospital; uproar ensues. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2019/05/07/lawsuit-filed-over-bible-display-at-new-hampshire-va-hospital-uproar-ensues. Published May 7, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

8. Scotusblog. The American Legion v American Humanist Association. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/the-american-legion-v-american-humanist-association. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans religions by state 2015. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Veterans_Religion_by_State.xlsx. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Smothers ZPW. Koenig HG. Spiritual interventions in veterans with PTSD: a systematic review. J Relig Health. 2018;57(5):2033-2048.

1. Roosevelt FD. The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. 1940 volume, War-and Aid to Democracies: With a Special Introduction and Explanatory Notes by President Roosevelt [Book 1]. New York: Macmillan; 1941:537.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VA Directive 0022: Religious symbols in VA facilities. https://www.va.gov/vapubs/viewPublication.asp?Pub_ID=849. Published July 3, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. SVA Directive 1111(1): Spiritual and pastoral care in the Veterans Health Administration. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=4299. Published November 22, 2016. Amended July 3, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

4. VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs. VA overhauls religious and spiritual symbol policies to protect religious liberty. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5279. Updated July 3, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

5. Oyez. The American Legion v American Humanist Association. www.oyez.org/cases/2018/17-1717. Accessed July 16, 2019.

6. The American Legion. Legion salutes VA policy change for religious freedom. https://www.legion.org/honor/246151/legion-salutes-va-policy-change-victory-religious-freedom. Published July 03, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

7. Miller K. Lawsuit filed over Bible display at New Hampshire VA Hospital; uproar ensues. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-military/2019/05/07/lawsuit-filed-over-bible-display-at-new-hampshire-va-hospital-uproar-ensues. Published May 7, 2019. Accessed July 22, 2019.

8. Scotusblog. The American Legion v American Humanist Association. https://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/the-american-legion-v-american-humanist-association. Accessed July 22, 2019.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans religions by state 2015. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Veterans_Religion_by_State.xlsx. Accessed July 22, 2019.

10. Smothers ZPW. Koenig HG. Spiritual interventions in veterans with PTSD: a systematic review. J Relig Health. 2018;57(5):2033-2048.

A Novel Pharmaceutical Care Model for High-Risk Patients

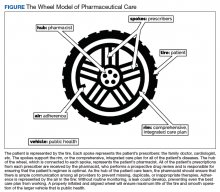

Nonadherence is a significant problem that has a negative impact on both patients and public health. Patients with multiple diseases often have complicated medication regimens, which can be difficult for them to manage. Unfortunately, nonadherence in these high-risk patients can have drastic consequences, including disease progression, hospitalization, and death, resulting in billions of dollars in unnecessary costs nationwide.1,2 The Wheel Model of Pharmaceutical Care (Figure) is a novel care model developed at the Gallup Indian Medical Center (GIMC) in New Mexico to address these problems by positioning pharmacy as a proactive service. The Wheel Model of Pharmaceutical Care was designed to improve adherence and patient outcomes and to encourage communication among the patient, pharmacists, prescribers, and other health care team members.

Pharmacists are central to managing patients’ medication therapies and coordinating communication among the health care providers (HCPs).1,3 Medication therapy management (MTM), a required component of Medicare Part D plans, helps ensure appropriate drug use and reduce the risk of adverse events.3 Since pharmacists receive prescriptions from all of the patient’s HCPs, patients may see pharmacists more often than they see any other HCP. GIMC is currently piloting a new clinic, the Medication Optimization, Synchronization, and Adherence Improvement Clinic (MOSAIC), that was created to implement the Wheel Model of Pharmaceutical Care. MOSAIC aims to provide proactive pharmacy services and continuous MTM to high-risk patients and will enable the effectiveness of this new pharmaceutical care model to be assessed.

Methods

Studies have identified certain populations who are at an increased risk for nonadherence: the elderly, patients with complex or extensive medication regimens, patients with multiple chronic medical conditions, substance misusers, certain ethnicities, patients of lower socioeconomic status, patients with limited literacy, and the homeless.2,4 Federal regulations require that Medicare Part D plans target beneficiaries who meet specific criteria for MTM programs. Under these rules, plans must target beneficiaries with ≥ 3 chronic diseases and ≥ 8 chronic medications, although plans also may include patients with fewer medications and diseases.3 Although the Wheel Model of Pharmaceutical Care is postulated to be an accurate model for the ideal care of all patients, initial implementation should be targeted toward populations who are likely to benefit the most from intervention. For these reasons, elderly Native American patients who have ≥ 2 chronic diseases and who take ≥ 5 chronic medications were targeted for initial enrollment in MOSAIC at GIMC.

Overview

In MOSAIC, pharmacists act as the hub of the pharmaceutical care wheel. Pharmacists work to ensure optimization of the patient’s comprehensive, integrated care plan—the rim of the wheel. As a part of this optimization process, MOSAIC pharmacists facilitate synchronization of the patient’s prescriptions to a monthly or quarterly target fill date. The patient’s current medication therapy is organized, and pharmacists track which medications are due to be filled instead of depending on the patient to request each prescription refill. This process effectively changes pharmacy from a requested service to a provided service.

Pharmacists also monitor the air in the tire to promote adherence. This is accomplished by providing efficient monthly or quarterly telephone or in-person consultations, which helps the patient better understand his or her comprehensive, integrated care plan. MOSAIC eliminates the possibility of nonadherence due to running out of refills. Specialized packaging, such as pill boxes or blister packs, can also improve adherence for certain patients.

MOSAIC ensures that pharmacists stay connected with the spokes, which represent a patient’s numerous prescribers, and close communication loops. Pharmacists can make prescribers aware of potential gaps or overlaps in treatment and assist them in the optimization and development of the patient’s comprehensive, integrated care plan. Pharmacists also make sure that the patient’s medication profile is current and accurate in the electronic health record (EHR). Any pertinent information discovered during MOSAIC encounters, such as abnormal laboratory results or changes in medications or disease, is documented in an EHR note. The patient’s prescribers are made aware of this information by tagging them as additional signers to the note in the EHR.

Keeping patients—the tires—healthy will ensure smooth operation of the vehicle and have a positive impact on public health. MOSAIC is expected to not only improve individual patient outcomes, but also decrease health care costs for patients and society due to nonadherence, suboptimal regimens, stockpiled home medications, and preventable hospital admissions.

Traditionally, pharmacy has been a requested service: A patient requests each of their prescriptions to be refilled, and the pharmacy fills the prescription. Ideally, pharmacy must become a provided service, with pharmacists keeping track of when a patient’s medications are due to be filled and actively looking for medication therapy optimization opportunities. This is accomplished by synchronizing the patient’s medications to the same monthly or quarterly fill date; screening for any potentially inappropriate medications, including high-risk medications in elderly patients, duplications, and omissions; verifying any medication changes with the patient each fill; and then providing all needed medications to the patient at a scheduled time.

To facilitate this process, custom software was developed for MOSAIC. In addition, a collaborative practice agreement (CPA) was drafted that allowed MOSAIC pharmacists to make certain medication therapy optimizations on behalf of the patient’s primary care provider. As part of this CPA, pharmacists also may order and act on certain laboratory tests, which helps to monitor disease progression, ensure safe medication use, and meet Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) measures. As a novel model of pharmaceutical care, the effects of this approach are not yet known; however, research suggests that increased communication among HCPs and patient-centered approaches to care are beneficial to patient outcomes, adherence, and public health.1,5

Investigated Outcomes

As patients continue to enroll in MOSAIC, the effectiveness of the clinic will be evaluated. Specifically, quality of life, patient and HCP satisfaction with the program, adherence metrics, hospitalization rates, and all-cause mortality will be assessed for patients enrolled in MOSAIC as well as similar patients who are not enrolled in MOSAIC. Also, pharmacists will log all recommended medication therapy interventions so that the optimization component of MOSAIC may be quantified. GPRA measures and the financial implications of the interventions made by MOSAIC will also be evaluated.

Discussion