User login

For MD-IQ use only

Caffeinated coffee intake linked to lower rosacea risk

Caffeinated coffee intake is linked to a decreased incidence of rosacea, results of a large, observational study suggest.

Increased levels of caffeinated coffee consumption were associated with progressively lower levels of incident rosacea in a study of more than 82,000 participants representing more than 1.1 million person-years of follow-up.

By contrast, caffeine from other foods was not associated with rosacea incidence, reported Wen-Qing Li, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his coinvestigators. Those findings may have implications for the “causes and clinical approach” to rosacea.

“Our findings do not support limiting caffeine intake as a preventive strategy for rosacea,” they concluded in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

This is not the first study looking for potential links between rosacea and caffeine or coffee intake. However, previous studies didn’t distinguish between caffeinated coffee versus other beverages, and only one previous study made a distinction between the amounts of caffeine and coffee consumed, according to the authors.

Their research was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study started in 1989. They looked specifically at 82,737 women who, in 2005, responded to the question about whether they had been diagnosed with rosacea. They identified 4,945 incident rosacea cases over the 1,120,051 person-years of follow-up.

A significant inverse association was found between caffeinated coffee intake and rosacea: Individuals who consumed four or more servings a day had a significantly lower risk of rosacea, compared with those who consumed one or fewer servings per month (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87; P less than .001). They also found a dose-dependent effect, with the absolute risk of rosacea decreased by 131 per 100,000 person-years with at least four daily servings of caffeinated coffee, compared with under one serving a month.

By contrast, decaffeinated coffee was not associated with a reduced risk of rosacea, and in further analysis, the investigators found that there was no significant inverse association when they looked just at caffeine intake from sources other than coffee, such as chocolate, tea, and soda.

Caffeine could influence rosacea incidence by one of several mechanisms, including its effect on vascular contractility, the investigators hypothesized. “Increased caffeine intake may decrease vasodilation and consequently lead to diminution of rosacea symptoms.”

However, caffeine also has documented immunosuppressant effects that could possibly decrease rosacea-associated inflammation and has been shown to modulate hormone levels. “Hormonal factors have been implicated in the development of rosacea, and caffeine can modulate hormone levels,” they wrote.

Two study authors reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, among others. Funding for the study came from several sources, including National Institutes of Health grants for the Nurses’ Health Study II.

SOURCE: Li W-Q et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3301.

This study shows an inverse association between caffeine intake and incidence rosacea, which suggests that patients with rosacea need not avoid coffee, according to Mackenzie R. Wehner, MD, and Eleni Linos, MD, MPH.

For everyone else, the findings offer yet another reason to keep indulging in one of “life’s habitual pleasures,” they wrote. “We will raise an insulated travel mug to that.”

This latest study fits in with numerous studies suggesting coffee may be protective against a number of maladies, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease, they wrote in their editorial published in JAMA Dermatology.

However, this is an observational study, not a rigorous, randomized trial that could more conclusively prove coffee actually provides an antirosacea benefit that cannot be explained by other factors, such as systematic differences between people who do and do not drink coffee. Enrollment of all women, mostly white, in the Nurses’ Health Study II is another limitation, they added.

Nevertheless, studies like this are the “next-best option” in lieu of randomized, controlled trials to evaluate these relationships, they wrote. “Importantly, the strength of the protective effect noted and the dose-response relationship with increasing coffee and caffeine intake are convincing.”

Dr. Wehner , is with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Linos is with the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Wehner reported support from a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/National Institutes of Health Dermatology Research Training grant. Dr. Linos reported support from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging.

This study shows an inverse association between caffeine intake and incidence rosacea, which suggests that patients with rosacea need not avoid coffee, according to Mackenzie R. Wehner, MD, and Eleni Linos, MD, MPH.

For everyone else, the findings offer yet another reason to keep indulging in one of “life’s habitual pleasures,” they wrote. “We will raise an insulated travel mug to that.”

This latest study fits in with numerous studies suggesting coffee may be protective against a number of maladies, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease, they wrote in their editorial published in JAMA Dermatology.

However, this is an observational study, not a rigorous, randomized trial that could more conclusively prove coffee actually provides an antirosacea benefit that cannot be explained by other factors, such as systematic differences between people who do and do not drink coffee. Enrollment of all women, mostly white, in the Nurses’ Health Study II is another limitation, they added.

Nevertheless, studies like this are the “next-best option” in lieu of randomized, controlled trials to evaluate these relationships, they wrote. “Importantly, the strength of the protective effect noted and the dose-response relationship with increasing coffee and caffeine intake are convincing.”

Dr. Wehner , is with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Linos is with the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Wehner reported support from a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/National Institutes of Health Dermatology Research Training grant. Dr. Linos reported support from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging.

This study shows an inverse association between caffeine intake and incidence rosacea, which suggests that patients with rosacea need not avoid coffee, according to Mackenzie R. Wehner, MD, and Eleni Linos, MD, MPH.

For everyone else, the findings offer yet another reason to keep indulging in one of “life’s habitual pleasures,” they wrote. “We will raise an insulated travel mug to that.”

This latest study fits in with numerous studies suggesting coffee may be protective against a number of maladies, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease, they wrote in their editorial published in JAMA Dermatology.

However, this is an observational study, not a rigorous, randomized trial that could more conclusively prove coffee actually provides an antirosacea benefit that cannot be explained by other factors, such as systematic differences between people who do and do not drink coffee. Enrollment of all women, mostly white, in the Nurses’ Health Study II is another limitation, they added.

Nevertheless, studies like this are the “next-best option” in lieu of randomized, controlled trials to evaluate these relationships, they wrote. “Importantly, the strength of the protective effect noted and the dose-response relationship with increasing coffee and caffeine intake are convincing.”

Dr. Wehner , is with the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Linos is with the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Wehner reported support from a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/National Institutes of Health Dermatology Research Training grant. Dr. Linos reported support from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging.

Caffeinated coffee intake is linked to a decreased incidence of rosacea, results of a large, observational study suggest.

Increased levels of caffeinated coffee consumption were associated with progressively lower levels of incident rosacea in a study of more than 82,000 participants representing more than 1.1 million person-years of follow-up.

By contrast, caffeine from other foods was not associated with rosacea incidence, reported Wen-Qing Li, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his coinvestigators. Those findings may have implications for the “causes and clinical approach” to rosacea.

“Our findings do not support limiting caffeine intake as a preventive strategy for rosacea,” they concluded in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

This is not the first study looking for potential links between rosacea and caffeine or coffee intake. However, previous studies didn’t distinguish between caffeinated coffee versus other beverages, and only one previous study made a distinction between the amounts of caffeine and coffee consumed, according to the authors.

Their research was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study started in 1989. They looked specifically at 82,737 women who, in 2005, responded to the question about whether they had been diagnosed with rosacea. They identified 4,945 incident rosacea cases over the 1,120,051 person-years of follow-up.

A significant inverse association was found between caffeinated coffee intake and rosacea: Individuals who consumed four or more servings a day had a significantly lower risk of rosacea, compared with those who consumed one or fewer servings per month (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87; P less than .001). They also found a dose-dependent effect, with the absolute risk of rosacea decreased by 131 per 100,000 person-years with at least four daily servings of caffeinated coffee, compared with under one serving a month.

By contrast, decaffeinated coffee was not associated with a reduced risk of rosacea, and in further analysis, the investigators found that there was no significant inverse association when they looked just at caffeine intake from sources other than coffee, such as chocolate, tea, and soda.

Caffeine could influence rosacea incidence by one of several mechanisms, including its effect on vascular contractility, the investigators hypothesized. “Increased caffeine intake may decrease vasodilation and consequently lead to diminution of rosacea symptoms.”

However, caffeine also has documented immunosuppressant effects that could possibly decrease rosacea-associated inflammation and has been shown to modulate hormone levels. “Hormonal factors have been implicated in the development of rosacea, and caffeine can modulate hormone levels,” they wrote.

Two study authors reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, among others. Funding for the study came from several sources, including National Institutes of Health grants for the Nurses’ Health Study II.

SOURCE: Li W-Q et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3301.

Caffeinated coffee intake is linked to a decreased incidence of rosacea, results of a large, observational study suggest.

Increased levels of caffeinated coffee consumption were associated with progressively lower levels of incident rosacea in a study of more than 82,000 participants representing more than 1.1 million person-years of follow-up.

By contrast, caffeine from other foods was not associated with rosacea incidence, reported Wen-Qing Li, PhD, of the department of dermatology at Brown University, Providence, R.I., and his coinvestigators. Those findings may have implications for the “causes and clinical approach” to rosacea.

“Our findings do not support limiting caffeine intake as a preventive strategy for rosacea,” they concluded in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

This is not the first study looking for potential links between rosacea and caffeine or coffee intake. However, previous studies didn’t distinguish between caffeinated coffee versus other beverages, and only one previous study made a distinction between the amounts of caffeine and coffee consumed, according to the authors.

Their research was based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study started in 1989. They looked specifically at 82,737 women who, in 2005, responded to the question about whether they had been diagnosed with rosacea. They identified 4,945 incident rosacea cases over the 1,120,051 person-years of follow-up.

A significant inverse association was found between caffeinated coffee intake and rosacea: Individuals who consumed four or more servings a day had a significantly lower risk of rosacea, compared with those who consumed one or fewer servings per month (hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.69-0.87; P less than .001). They also found a dose-dependent effect, with the absolute risk of rosacea decreased by 131 per 100,000 person-years with at least four daily servings of caffeinated coffee, compared with under one serving a month.

By contrast, decaffeinated coffee was not associated with a reduced risk of rosacea, and in further analysis, the investigators found that there was no significant inverse association when they looked just at caffeine intake from sources other than coffee, such as chocolate, tea, and soda.

Caffeine could influence rosacea incidence by one of several mechanisms, including its effect on vascular contractility, the investigators hypothesized. “Increased caffeine intake may decrease vasodilation and consequently lead to diminution of rosacea symptoms.”

However, caffeine also has documented immunosuppressant effects that could possibly decrease rosacea-associated inflammation and has been shown to modulate hormone levels. “Hormonal factors have been implicated in the development of rosacea, and caffeine can modulate hormone levels,” they wrote.

Two study authors reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, among others. Funding for the study came from several sources, including National Institutes of Health grants for the Nurses’ Health Study II.

SOURCE: Li W-Q et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3301.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Caffeinated coffee intake was linked to decreased incidence of rosacea, while decaffeinated coffee and noncoffee sources of caffeine had no such effect.

Major finding: Consuming four or more servings of caffeinated coffee was associated with lower risk of rosacea versus one or fewer servings per month (hazard ratio, 0.77; P less than .001).

Study details: An analysis based on 82,737 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study II who responded to a question about rosacea.

Disclosures: Two study authors reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer, among others. Funding for the study came from National Institutes of Health grants for the Nurses’ Health Study II and other sources.

Source: Li W-Q et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Oct 17. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3301.

Most nonemergent diagnoses can’t be predicted

Also today, opioids have a negative effect on breathing during sleep, the American Academy of Pediatrics renews its public health approach regarding gun injury prevention, and fever and intestinal symptoms can delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children.

Also today, opioids have a negative effect on breathing during sleep, the American Academy of Pediatrics renews its public health approach regarding gun injury prevention, and fever and intestinal symptoms can delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children.

Also today, opioids have a negative effect on breathing during sleep, the American Academy of Pediatrics renews its public health approach regarding gun injury prevention, and fever and intestinal symptoms can delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children.

New cholesterol, physical activity guidelines on tap at AHA 2018

Two new guidelines are set to be presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago.

First up will be the first update to the controversial 2013 cholesterol guidelines, which will be presented on Saturday, Nov. 10, in two sessions.

Second, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will unveil its new national guidelines for physical activity on Monday, Nov. 12.

Cholesterol guidelines

For the cholesterol guidelines, the most important messages for clinical practice will be presented in a session beginning at 10:45 a.m. A second session, beginning at 5:30 p.m. on Saturday, can be considered more of a “deep dive” into the details and rationale, Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, cochair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program, said in a teleconference with reporters.

“In the 10:45 session, we plan to cover the most important take-home messages and top-line issues,” explained Dr. Lloyd-Jones, a professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago, as well as one of the authors of both the 2013 cholesterol guidelines and these updated ones.

This will include the key changes since the AHA/American College of Cardiology Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk guidelines were released 2013. One major update will be the inclusion of the role of PCSK9 inhibitors, which were introduced after the 2013 guidelines were written. Moreover, the new guidelines will devote attention to personalizing treatment choices, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

“The deep-dive session later that day will cover such issues as risk assessment and cost effectiveness of drug treatments for specific populations,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who added that case studies will be presented to illustrate how the new recommendations should affect practice.

Because of changes in risk assessment, the 2013 guidelines, which greatly expanded the candidates for lipid-lowering therapies, were labeled “controversial” in numerous critiques published in peer-reviewed journals and elsewhere. The authors of the new guidelines hope to avoid these problems.

“Since 2013, I think there have been questions about when we should use risk scores, whether there are risk scores that might be better than others, or if there are strategies of risk assessment we should be employing beyond just risk scores,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones acknowledged. “This was a big part of the discussion in developing these guidelines, and I think you will see some pretty significant advances in how we think about which patients are appropriate for treatment and which patients in whom we might think of withholding statin therapy when benefit is unlikely.”

Despite the large number of changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones emphasized that the document will be more concise and easier to use than the guidelines from 2013.

“The organization is modular, meaning that if you have a question about a certain aspect of management, you can go straight to the recommendation, which is accompanied by very brief text to explain the rationale,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported. “The presentation has been very much streamlined.”

HHS Guidelines on Physical Activity

The HHS guidelines on physical activity will be presented at 9 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 12. The 2018 version will be the first update since the original guidelines were made available in 2008.

“It has been 10 years since the last set of guidelines, and I think we are all looking forward to what these new recommendations will offer,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said. He believes that the science has progressed significantly over the past decade.

“In addition to our longstanding understanding that doing something is better than doing nothing and doing more is better than doing something, I think we have seen some really interesting data in the last 10 years on intensity and duration of exercise and how those can be considered when trying to improve health-related outcomes,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

The specifics of these guidelines will not be known until they are presented on Monday, but there is abundant evidence that a healthy lifestyle is the first defense against illness in general and against cardiovascular disease in particular. Dr. Lloyd-Jones indicated that authoritative and evidence-based guidelines could prove to a useful tool for empowering patients to make changes that reduce an array of health risks not just those related to vascular disease.

Two new guidelines are set to be presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago.

First up will be the first update to the controversial 2013 cholesterol guidelines, which will be presented on Saturday, Nov. 10, in two sessions.

Second, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will unveil its new national guidelines for physical activity on Monday, Nov. 12.

Cholesterol guidelines

For the cholesterol guidelines, the most important messages for clinical practice will be presented in a session beginning at 10:45 a.m. A second session, beginning at 5:30 p.m. on Saturday, can be considered more of a “deep dive” into the details and rationale, Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, cochair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program, said in a teleconference with reporters.

“In the 10:45 session, we plan to cover the most important take-home messages and top-line issues,” explained Dr. Lloyd-Jones, a professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago, as well as one of the authors of both the 2013 cholesterol guidelines and these updated ones.

This will include the key changes since the AHA/American College of Cardiology Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk guidelines were released 2013. One major update will be the inclusion of the role of PCSK9 inhibitors, which were introduced after the 2013 guidelines were written. Moreover, the new guidelines will devote attention to personalizing treatment choices, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

“The deep-dive session later that day will cover such issues as risk assessment and cost effectiveness of drug treatments for specific populations,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who added that case studies will be presented to illustrate how the new recommendations should affect practice.

Because of changes in risk assessment, the 2013 guidelines, which greatly expanded the candidates for lipid-lowering therapies, were labeled “controversial” in numerous critiques published in peer-reviewed journals and elsewhere. The authors of the new guidelines hope to avoid these problems.

“Since 2013, I think there have been questions about when we should use risk scores, whether there are risk scores that might be better than others, or if there are strategies of risk assessment we should be employing beyond just risk scores,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones acknowledged. “This was a big part of the discussion in developing these guidelines, and I think you will see some pretty significant advances in how we think about which patients are appropriate for treatment and which patients in whom we might think of withholding statin therapy when benefit is unlikely.”

Despite the large number of changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones emphasized that the document will be more concise and easier to use than the guidelines from 2013.

“The organization is modular, meaning that if you have a question about a certain aspect of management, you can go straight to the recommendation, which is accompanied by very brief text to explain the rationale,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported. “The presentation has been very much streamlined.”

HHS Guidelines on Physical Activity

The HHS guidelines on physical activity will be presented at 9 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 12. The 2018 version will be the first update since the original guidelines were made available in 2008.

“It has been 10 years since the last set of guidelines, and I think we are all looking forward to what these new recommendations will offer,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said. He believes that the science has progressed significantly over the past decade.

“In addition to our longstanding understanding that doing something is better than doing nothing and doing more is better than doing something, I think we have seen some really interesting data in the last 10 years on intensity and duration of exercise and how those can be considered when trying to improve health-related outcomes,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

The specifics of these guidelines will not be known until they are presented on Monday, but there is abundant evidence that a healthy lifestyle is the first defense against illness in general and against cardiovascular disease in particular. Dr. Lloyd-Jones indicated that authoritative and evidence-based guidelines could prove to a useful tool for empowering patients to make changes that reduce an array of health risks not just those related to vascular disease.

Two new guidelines are set to be presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Chicago.

First up will be the first update to the controversial 2013 cholesterol guidelines, which will be presented on Saturday, Nov. 10, in two sessions.

Second, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will unveil its new national guidelines for physical activity on Monday, Nov. 12.

Cholesterol guidelines

For the cholesterol guidelines, the most important messages for clinical practice will be presented in a session beginning at 10:45 a.m. A second session, beginning at 5:30 p.m. on Saturday, can be considered more of a “deep dive” into the details and rationale, Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, cochair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program, said in a teleconference with reporters.

“In the 10:45 session, we plan to cover the most important take-home messages and top-line issues,” explained Dr. Lloyd-Jones, a professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago, as well as one of the authors of both the 2013 cholesterol guidelines and these updated ones.

This will include the key changes since the AHA/American College of Cardiology Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk guidelines were released 2013. One major update will be the inclusion of the role of PCSK9 inhibitors, which were introduced after the 2013 guidelines were written. Moreover, the new guidelines will devote attention to personalizing treatment choices, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

“The deep-dive session later that day will cover such issues as risk assessment and cost effectiveness of drug treatments for specific populations,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who added that case studies will be presented to illustrate how the new recommendations should affect practice.

Because of changes in risk assessment, the 2013 guidelines, which greatly expanded the candidates for lipid-lowering therapies, were labeled “controversial” in numerous critiques published in peer-reviewed journals and elsewhere. The authors of the new guidelines hope to avoid these problems.

“Since 2013, I think there have been questions about when we should use risk scores, whether there are risk scores that might be better than others, or if there are strategies of risk assessment we should be employing beyond just risk scores,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones acknowledged. “This was a big part of the discussion in developing these guidelines, and I think you will see some pretty significant advances in how we think about which patients are appropriate for treatment and which patients in whom we might think of withholding statin therapy when benefit is unlikely.”

Despite the large number of changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones emphasized that the document will be more concise and easier to use than the guidelines from 2013.

“The organization is modular, meaning that if you have a question about a certain aspect of management, you can go straight to the recommendation, which is accompanied by very brief text to explain the rationale,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones reported. “The presentation has been very much streamlined.”

HHS Guidelines on Physical Activity

The HHS guidelines on physical activity will be presented at 9 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 12. The 2018 version will be the first update since the original guidelines were made available in 2008.

“It has been 10 years since the last set of guidelines, and I think we are all looking forward to what these new recommendations will offer,” Dr. Lloyd-Jones said. He believes that the science has progressed significantly over the past decade.

“In addition to our longstanding understanding that doing something is better than doing nothing and doing more is better than doing something, I think we have seen some really interesting data in the last 10 years on intensity and duration of exercise and how those can be considered when trying to improve health-related outcomes,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

The specifics of these guidelines will not be known until they are presented on Monday, but there is abundant evidence that a healthy lifestyle is the first defense against illness in general and against cardiovascular disease in particular. Dr. Lloyd-Jones indicated that authoritative and evidence-based guidelines could prove to a useful tool for empowering patients to make changes that reduce an array of health risks not just those related to vascular disease.

AHA 3-day format syncs with new direction in scientific meetings

Although a day shorter than meetings over recent years, more than 4,000 abstracts, keynote addresses, special sessions, and education programs have been squeezed into 800 sessions divided into 26 tracks of interest at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“We think that, for both for the presenters as well as for the attendees, ,” explained Eric Peterson, MD, chair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program in a teleconference with reporters.

The shorter program is just one of many substantive changes made by the program committee to enhance the value of attendance, according to Dr. Peterson, professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. In particular, the committee worked to make the sessions more interactive.

“There will be much less of someone just standing up and delivering slides,” he said. Through phone apps that will allow the audience to pose questions and comments to speakers in every major session, “there will be more opportunities for the audience to give their impression of the science being delivered.”

From the beginning, it was the intention of the program committee “to do things differently,” according to Dr. Peterson as well as his cochair Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

“The 3-day format means full days, but I think that we have packed in some really exciting science,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who described a diverse slate of programming goals. In addition to the traditional emphasis on new science, he said there will be more attention on “new management and new practice opportunities for clinicians to really hone their skills.”

Those coming to the Scientific Sessions will see a difference on the first day. In place of an awards ceremony and presidential address, which have long been staples of the opening sessions, this year’s meeting will begin with a series of simultaneous programs delving into key issues in cardiology and medical practice.

“We are starting things off with a bang with TED-like lectures given in multiple locations addressing the cutting edge of where we are with the hottest things in science,” Dr. Peterson said. “These will cover everything from how your microbiome might be affecting your risk for cardiovascular events to progress toward vaccines that might some day prevent cardiovascular disease.”

Innovative and forward-thinking programs unfold from there, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

Health technology will be a common thread across all 3 days of the Scientific Sessions, according to Dr. Peterson. One of the 26 tracks of this year’s meeting, health technology is imposing fundamental shifts in medical practice and how health care is delivered.

“This is a topic that covers electronic medical records, your cell phone, and mobile wearable devices that can help us as clinicians better understand what is going on with cardiovascular disease as well as help ourselves as individuals modify our risks,” said Dr. Peterson. Within this track, session programs range from how-to instruction to a technology forum organized like the “Shark Tank” television program.

“Health technology is moving rapidly,” Dr. Peterson pointed out. He suggested that the AHA Scientific Sessions provide a unique opportunity for cardiologists to stay current with evolving strategies for efficient care.

Within the effort to update the meeting format, traditional forms of late-breaking science, particularly late-breaking trials with potentially practice changing data, will not be lost. However, Dr. Peterson indicated that he expects this year’s meeting to have a somewhat different pace and sensibility.

“We believe that what we have been doing will not work any longer, and we needed to do things differently,” Dr. Peterson said. While the shorter more concentrated program is one example, Dr. Peterson also believes that the effort to diminish the distance between those who are speaking and those who are listening will lead to a richer experience for everyone.

Although a day shorter than meetings over recent years, more than 4,000 abstracts, keynote addresses, special sessions, and education programs have been squeezed into 800 sessions divided into 26 tracks of interest at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“We think that, for both for the presenters as well as for the attendees, ,” explained Eric Peterson, MD, chair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program in a teleconference with reporters.

The shorter program is just one of many substantive changes made by the program committee to enhance the value of attendance, according to Dr. Peterson, professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. In particular, the committee worked to make the sessions more interactive.

“There will be much less of someone just standing up and delivering slides,” he said. Through phone apps that will allow the audience to pose questions and comments to speakers in every major session, “there will be more opportunities for the audience to give their impression of the science being delivered.”

From the beginning, it was the intention of the program committee “to do things differently,” according to Dr. Peterson as well as his cochair Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

“The 3-day format means full days, but I think that we have packed in some really exciting science,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who described a diverse slate of programming goals. In addition to the traditional emphasis on new science, he said there will be more attention on “new management and new practice opportunities for clinicians to really hone their skills.”

Those coming to the Scientific Sessions will see a difference on the first day. In place of an awards ceremony and presidential address, which have long been staples of the opening sessions, this year’s meeting will begin with a series of simultaneous programs delving into key issues in cardiology and medical practice.

“We are starting things off with a bang with TED-like lectures given in multiple locations addressing the cutting edge of where we are with the hottest things in science,” Dr. Peterson said. “These will cover everything from how your microbiome might be affecting your risk for cardiovascular events to progress toward vaccines that might some day prevent cardiovascular disease.”

Innovative and forward-thinking programs unfold from there, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

Health technology will be a common thread across all 3 days of the Scientific Sessions, according to Dr. Peterson. One of the 26 tracks of this year’s meeting, health technology is imposing fundamental shifts in medical practice and how health care is delivered.

“This is a topic that covers electronic medical records, your cell phone, and mobile wearable devices that can help us as clinicians better understand what is going on with cardiovascular disease as well as help ourselves as individuals modify our risks,” said Dr. Peterson. Within this track, session programs range from how-to instruction to a technology forum organized like the “Shark Tank” television program.

“Health technology is moving rapidly,” Dr. Peterson pointed out. He suggested that the AHA Scientific Sessions provide a unique opportunity for cardiologists to stay current with evolving strategies for efficient care.

Within the effort to update the meeting format, traditional forms of late-breaking science, particularly late-breaking trials with potentially practice changing data, will not be lost. However, Dr. Peterson indicated that he expects this year’s meeting to have a somewhat different pace and sensibility.

“We believe that what we have been doing will not work any longer, and we needed to do things differently,” Dr. Peterson said. While the shorter more concentrated program is one example, Dr. Peterson also believes that the effort to diminish the distance between those who are speaking and those who are listening will lead to a richer experience for everyone.

Although a day shorter than meetings over recent years, more than 4,000 abstracts, keynote addresses, special sessions, and education programs have been squeezed into 800 sessions divided into 26 tracks of interest at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“We think that, for both for the presenters as well as for the attendees, ,” explained Eric Peterson, MD, chair of this year’s Committee on Scientific Sessions Program in a teleconference with reporters.

The shorter program is just one of many substantive changes made by the program committee to enhance the value of attendance, according to Dr. Peterson, professor of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. In particular, the committee worked to make the sessions more interactive.

“There will be much less of someone just standing up and delivering slides,” he said. Through phone apps that will allow the audience to pose questions and comments to speakers in every major session, “there will be more opportunities for the audience to give their impression of the science being delivered.”

From the beginning, it was the intention of the program committee “to do things differently,” according to Dr. Peterson as well as his cochair Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

“The 3-day format means full days, but I think that we have packed in some really exciting science,” said Dr. Lloyd-Jones, who described a diverse slate of programming goals. In addition to the traditional emphasis on new science, he said there will be more attention on “new management and new practice opportunities for clinicians to really hone their skills.”

Those coming to the Scientific Sessions will see a difference on the first day. In place of an awards ceremony and presidential address, which have long been staples of the opening sessions, this year’s meeting will begin with a series of simultaneous programs delving into key issues in cardiology and medical practice.

“We are starting things off with a bang with TED-like lectures given in multiple locations addressing the cutting edge of where we are with the hottest things in science,” Dr. Peterson said. “These will cover everything from how your microbiome might be affecting your risk for cardiovascular events to progress toward vaccines that might some day prevent cardiovascular disease.”

Innovative and forward-thinking programs unfold from there, according to Dr. Lloyd-Jones.

Health technology will be a common thread across all 3 days of the Scientific Sessions, according to Dr. Peterson. One of the 26 tracks of this year’s meeting, health technology is imposing fundamental shifts in medical practice and how health care is delivered.

“This is a topic that covers electronic medical records, your cell phone, and mobile wearable devices that can help us as clinicians better understand what is going on with cardiovascular disease as well as help ourselves as individuals modify our risks,” said Dr. Peterson. Within this track, session programs range from how-to instruction to a technology forum organized like the “Shark Tank” television program.

“Health technology is moving rapidly,” Dr. Peterson pointed out. He suggested that the AHA Scientific Sessions provide a unique opportunity for cardiologists to stay current with evolving strategies for efficient care.

Within the effort to update the meeting format, traditional forms of late-breaking science, particularly late-breaking trials with potentially practice changing data, will not be lost. However, Dr. Peterson indicated that he expects this year’s meeting to have a somewhat different pace and sensibility.

“We believe that what we have been doing will not work any longer, and we needed to do things differently,” Dr. Peterson said. While the shorter more concentrated program is one example, Dr. Peterson also believes that the effort to diminish the distance between those who are speaking and those who are listening will lead to a richer experience for everyone.

CMS pulls back on E/M payment proposal

Also today, exercise improves outcomes for patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea, FDA panels back brexanolone infusion for postpartum depression, and sleep could be the new frontier in cardiovascular prevention.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, exercise improves outcomes for patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea, FDA panels back brexanolone infusion for postpartum depression, and sleep could be the new frontier in cardiovascular prevention.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, exercise improves outcomes for patients with heart failure and obstructive sleep apnea, FDA panels back brexanolone infusion for postpartum depression, and sleep could be the new frontier in cardiovascular prevention.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Initiative to Minimize Pharmaceutical Risk in Older Veterans (IMPROVE) Polypharmacy Clinic

An interprofessional polypharmacy clinic for intensive management of medication regimens helps high-risk patients manage their medications.

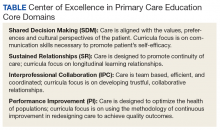

In 2011, 5 VA medical centers (VAMCs) were selected by the Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish CoEPCE. Part of the VA New Models of Care initiative, the 5 Centers of Excellence (CoE) in Boise, Idaho; Cleveland, Ohio; San Francisco, California; Seattle, Washington; and West Haven, Connecticut, are utilizing VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents and students, advanced practice nurse residents and undergraduate nursing students, and other professions of health trainees (eg, pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants [PAs], physical therapists) for primary care practice in the 21st century. The CoEs are developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula designed to prepare learners from relevant professions to practice in patient-centered, interprofessional team-based primary care settings. The curricula at all CoEs must address 4 core domains (Table).

Health care professional education programs do not have many opportunities for workplace learning where trainees from different professions can learn and work together to provide care to patients in real time.

The VA Connecticut Healthcare System CoEPCE developed and implemented an education and practice-based immersion learning model with physician residents, nurse practitioner (NP) residents and NP students, pharmacy residents, postdoctorate psychology learners, and PA and physical therapy learners and faculty. This interprofessional, collaborative team model breaks from the traditional independent model of siloed primary care providers (PCPs) caring for a panel of patients.

Methods

In 2015, OAA evaluators reviewed background documents and conducted open-ended interviews with 12 West Haven CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, VA faculty, VA facility leadership, and affiliate faculty. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the Initiative to Minimize Pharmaceutical Risk in Older Veterans (IMPROVE) program to trainees, veterans, and the VA.

Lack of Clinical Approaches to Interprofessional Education and Care

Polypharmacy is a common problem among older adults with multiple chronic conditions, which places patients at higher risk for multiple negative health outcomes.2,3 The typical primary care visit rarely allows for a thorough review of a patient’s medications, much less the identification of strategies to reduce polypharmacy and improve medication management. Rather, the complexity inherent to polypharmacy makes it an ideal challenge for a team-based approach.

Team Approach to Medication Needs

A key CoEPCE program aim is to expand workplace learning instruction strategies and to create more clinical opportunities for CoEPCE trainees to work together as a team to anticipate and address the health care needs of veterans. To address this training need, the West Haven CoEPCE developed IMPROVE to focus on high-need patients and provides a venue in which trainees and supervisors from different professions can collaborate on a specific patient case, using a patient-centered framework. IMPROVE can be easily applied to a range of medication-related aims, such as reducing medications, managing medications and adherence, and addressing adverse effects (AEs). These goals are 2-fold: (1) implement a trainee-led performance improvement project that reduces polypharmacy in elderly veterans; and (2) develop a hands-on, experiential geriatrics training program that enhances trainee skills and knowledge related to safe prescribing.

Planning and Implementation

IMPROVE has its origins in a scholarly project developed by a West Haven CoE physician resident trainee. Development of the IMPROVE program involved VA health psychology, internal medicine faculty, geriatric medicine faculty, NP faculty, and geriatric pharmacy residents and faculty. Planning started in 2013 with a series of pilot clinics and became an official project of the West Haven CoE in September 2014. The intervention required no change in West Haven VAMC policy. However, the initiative required buy-in from West Haven CoE leadership and the director of the West Haven primary care clinic.

Curriculum

IMPROVE is an educational, workplace learning, and clinical activity that combines a 1-hour trainee teaching session, a 45-minute group visit, and a 60-minute individual clinic visit to address the complex problem of polypharmacy. It emphasizes the sharing of trainee and faculty backgrounds by serving as a venue for interprofessional trainees and providers to discuss pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment in the elderly and brainstorm strategies to optimize treatment regimens, minimize risk, and execute medication plans with patients.

All CoEPCE trainees in West Haven are required to participate in IMPROVE and on average, each trainee presents and sees one of their patients at least 3 times per year in the program. Up to 5 trainees participate in each IMPROVE session. Trainees are responsible for reviewing their panels to identify patients who might benefit from participation, followed by inviting the patient to participate. Patients are instructed to bring their pill bottles to the visit. To prepare for the polypharmacy clinic, the trainees, the geriatrician, and the geriatric pharmacist perform an extensive medication chart review, using the medication review worksheet developed by West Haven VAMC providers.4 They also work with a protocol for medication discontinuation, which was compiled by West Haven VAMC clinicians. The teams use a variety of tools that guide appropriate prescribing in older adult populations.5,6 During a preclinic conference, trainees present their patients to the interprofessional team for discussion and participate in a short discussion led by a pharmacist, geriatrician, or health psychologist on a topic related to prescribing safety in older adults or nonpharmacologic treatments.

IMPROVE emphasizes a patient-centered approach to develop, execute, and monitor medication plans. Patients and their family members are invited by their trainee clinician to participate in a group visit. Typically, trainees invite patients aged ≥ 65 years who have ≥ 10 medications and are considered appropriate for a group visit.

The group visit process is based on health psychology strategies, which often incorporate group-based engagement with patients. The health psychologist can give advice to facilitate the visit and optimize participant involvement. There is a discussion facilitator guide that lists the education points to be covered by a designated trainee facilitator and sample questions to guide the discussion.7 A health psychology resident and other rotating trainees cofacilitate the group visit with a goal to reach out to each group member, including family members, and have them discuss perceptions and share concerns and treatment goals. There is shared responsibility among the trainees to address the educational material as well as involve their respective patients during the sessions.

Immediately following the group visit, trainees conduct a 1-hour clinic session that includes medication reconciliation, a review of an IMPROVE questionnaire, orthostatic vital signs, and the St. Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) exam to assess changes in cognition.7,8 Discussion involved the patient’s medication list as well as possible changes that could be made to the list. Using shared decision-making techniques, this conversation considers the patients’ treatment goals, feelings about the medications, which medications they would like to stop, and AEs they may be experiencing. After the individual visit is completed, the trainee participates in a 10-minute interprofessional precepting session, which may include a geriatrician, a pharmacist, and a health psychologist. In the session they may discuss adjustments to medications and a safe follow-up plan, including appropriate referrals. Trainees discuss the plan with the patient and send a letter describing the plan shortly after the visit.

IMPROVE combines didactic teaching with experiential education. It embodies the 4 core domains that shape the CoEPCE curriculum. First, trainees learn interprofessional collaboration concepts, including highlighting the roles of each profession and working with an interprofessional team to solve problems. Second, CoEPCE trainees learn performance improvement under the supervision of faculty. Third, IMPROVE allows trainees to develop sustained relationships with other team members while improving the quality of the clinic experience as well as with patients through increased continuity of care. Trainees see patients on their panel and are responsible for outreach before and after the visit. Finally, with a focus on personalized patient goals, trainees have the opportunity to further develop skills in shared decision making (SDM).

Related: Reducing Benzodiazepine Prescribing in Older Veterans: A Direct-to-Consumer Educational Brochure

The IMPROVE model continues to evolve. The original curriculum involved an hour-long preclinic preparation session before the group visit in which trainees and faculty discussed the medication review for each patient scheduled that day. This preparation session was later shortened to 40 minutes, and a 20-minute didactic component was added to create the current preclinic session. The didactic component focused on a specific topic in appropriate prescribing for older patients. For example, one didactic lesson is on a particular class of medications, its common AEs, and practical prescribing and “deprescribing” strategies for that class. Initially, the oldest patients or patients who could be grouped thematically, such as those taking both narcotics and benzodiazepines, were invited to participate, but that limited the number of appropriate patients within the CoEPCE. Currently, trainees identify patients from their panels who might benefit, based on age, number of medications, or potential medication-related concerns, such as falls, cognitive impairment, or other concerns for adverse drug effects. These trainees have the unique opportunity to apply learned strategies to their patients to continue to optimize the medication regimen even after the IMPROVE visit. Another significant change was the inclusion of veterans who are comanaged with PCPs outside the VA, because we found that patients with multiple providers could benefit from improved coordination of care.

Faculty Role

CoE faculty and non-CoE VA faculty participate in supervisory, consulting, teaching and precepting roles. Some faculty members such as the health psychologists are already located in or near the VA primary care clinic, so they can assist in curriculum development and execution during their regular clinic duties. The geriatrician reviews the patients’ health records before the patients come into the clinic, participates in the group visit, and coprecepts during the 1:1 patient visits. Collaboration is inherent in IMPROVE. For example, the geriatrician works with the geriatric pharmacist to identify and teach an educational topic. IMPROVE is characterized by a strong faculty/trainee partnership, with trainees playing roles as both teacher and facilitator in addition to learning how to take a team approach to polypharmacy.

Resources

IMPROVE requires administrative and academic support, especially faculty and trainee preparation of education sessions. The CoEPCE internal medicine resident and the internal medicine chief resident work with the health technicians for each patient aligned care team (PACT) to enter the information into the VA medical scheduling system. Trainee clinic time is blocked for their group visits in advance. Patients are scheduled 1 to 3 weeks in advance. Trainees and faculty are expected to review the medication review worksheet and resources prior to the visit. One CoEPCE faculty member reviews patients prior to the preclinic session (about an hour of preparation per session). Sufficient space also is required: a room large enough to accommodate up to 10 people for both didactic lessons and preclinic sessions, a facility patient education conference room for the group visit, and up to 5 clinic exam rooms. CoEPCE staff developed a templated note in the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), the VA electronic health record system to guide trainees step-by-step through the clinic visit and allow them to directly enter information into the system.7

Monitoring and Assessment

CoEPCE staff are evaluating IMPROVE by building a database for patient-level and trainee-level outcomes, including changes in trainee knowledge and attitudes over time. The CoEPCE also validated the polypharmacy knowledge assessment tool for medicine and NP trainees.

Partnerships

IMPROVE has greatly benefited from partnerships with facility department leadership, particularly involvement of pharmacy staff. In addition, we have partnered with both the health psychology and pharmacy faculty and trainees to participate in the program. Geriatrics faculty and trainees also have contributed extensively to IMPROVE. Future goals include offering the program to non-COEPCE patients throughout primary care.

The Yale Primary Care Internal Medicine Residency program and the Yale Categorical Internal Medicine Residency Program are integral partners to the CoEPCE. IMPROVE supports their mandate to encourage interprofessional teamwork in primary care, meet the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education interprofessional milestones, and promote individual trainee scholarship and performance improvement in areas of broad applicability. IMPROVE also is an opportunity to share ideas across institutions and stimulate new collaborations and dissemination of the model to other primary care settings outside the VA.

Challenges and Solutions

The demand for increased direct patient care pressures programs like IMPROVE, which is a time-intensive process with high impact on a few complex patients. The assumption is that managing medications will save money in the long run, but in the short-term, a strong case has to be made for securing resources, particularly blocking provider time and securing an education room for group visits and clinic exam rooms for individual visits. First, decision makers need to be convinced that polypharmacy is important and should be a training priority. The CoEPCE has tried different configurations to increase the number of patients being seen, such as having ≥ 1 IMPROVE session in an afternoon, but trainees found this to be labor intensive and stressful.

Second, patients with medications prescribed by providers outside the VA require additional communication and coordination to reduce medications. The CoEPCE initially excluded these patients, but after realizing that some of these patients needed the most help, it developed a process for reaching out to non-VA providers and coordinating care. Additionally, there is significant diversity in patient polypharmacy needs. These can range from adherence problems to the challenge of complex psychosocial needs that are more easily (but less effectively) addressed with medications. The issue of polypharmacy is further complicated by evolving understanding of medications’ relative risks and benefits in older adults with multiple chronic conditions. IMPROVE is an effective vehicle for synthesizing current science in medications and their management, especially in complex older patients with multiple chronic conditions.

Other challenges include developing a templated CPRS electronic note that interfaces with the VA information technology system. The process of creating a template, obtaining approval from the forms committee, and working with information technology personnel to implement the template was more time intensive than anticipated and required multiple iterations of proofreading and editing.

Factors for Success

The commitment to support new models of trainee education by West Haven CoEPCE faculty and leadership, and West Haven VAMC and primary care clinic leadership facilitated the implementation of IMPROVE. Additionally, there is strong CoEPCE collaboration at all levels—codirectors, faculty, and trainees—for the program. High interprofessional trainee interest, organizational insight, and an academic orientation were critical for developing and launching IMPROVE.

Additionally, there is synergy with other team-based professions. Geriatrics has a tradition of working in multidisciplinary teams as well as working with SDM concepts as part of care discussions. High interest and collaboration by a geriatrician and an experienced geriatric pharmacist has been key. The 2 specialties complement each other and address the complex health needs of participating veterans. Health psychologists transition patients to nonpharmacologic treatments, such as sleep hygiene education and cognitive behavioral therapy, in addition to exploring barriers to behavior change.

Another factor for success has been the CoEPCE framework and expertise in interprofessional education. While refining the model, program planners tapped into existing expertise in polypharmacy within the VA from the geriatrics, pharmacy, and clinical health psychology departments. The success of the individual components—the preparation session, the group visit, and the 1:1 patient visit—is in large part the result of a collective effort by CoEPCE staff and the integration of CoEPCE staff through coordination, communications, logistics, quality improvement, and faculty involvement from multiple professions.

The IMPROVE model is flexible and can accommodate diverse patient interests and issues. Model components are based on sound practices that have demonstrated success in other arenas, such as diabetes mellitus group visits. The model can also accommodate diverse trainee levels. Senior trainees can be more independent in developing their care plans, teaching the didactic topic, or precepting during the 1:1 patient exam.

Accomplishments and Benefits

Trainees are using team skills to provide patient-centered care. They are strengthening their clinical skills through exposure to patients in a group visit and 1:1 clinic visit. There have been significant improvements in the trainees’ provision of individual patient care. Key IMPROVE outcomes are outlined below.

Interprofessional Education

Unlike a traditional didactic, IMPROVE is an opportunity for health care professionals to work together to provide care in a clinic setting. It also expands CoEPCE interprofessional education capacity through colocation of different trainee and faculty professions during the conference session. This combination trains participants to work as a team and reflect on patients together, which has strengthened communications among professions. The model provides sufficient time and expertise to discuss the medications in detail and as a team, something that would not normally happen during a regular primary care visit.

CoEPCE trainees learn about medication management, its importance in preventing complications and improving patient health outcomes. Trainees of all professions learn to translate the skills they learn in IMPROVE to other patients, such as how to perform a complete medication reconciliation or lead a discussion using SDM. IMPROVE also provides techniques useful in other contexts, such as group visits and consideration of different medication options for patients who have been cared for by other (VA and non-VA) providers.

Interprofessional Collaboration

Understanding and leveraging the expertise of trainees and faculty from different professions is a primary goal of IMPROVE. Education sessions, the group visit, and precepting model are intentionally designed to break down silos and foster a team approach to care, which supports the PACT team model. Trainees and faculty all have their unique strengths and look at the issue from a different perspective, which increases the likelihood that the patient will hear a cohesive solution or strategy. The result is that trainees are more well rounded and become better practitioners who seek advice from other professions and work well in teams.

Trainees are expected to learn about other professions and their skill sets. For example, trainees learn early about the roles and scopes of practice of pharmacists and health psychologists for more effective referrals. Discussions during the session before the group visit may bring conditions like depression or dementia to the trainees’ attention. This is significant because issues like patient motivation may be better handled from a behavioral perspective.

Expanded Clinical Performance

IMPROVE is an opportunity for CoEPCE trainees to expand their clinical expertise. It provides exposure to a variety of patients and patient care needs and is an opportunity to present a high-risk patient to colleagues of various professions. As of December 2015, about 30 internal medicine residents and 6 NP residents have seen patients in the polypharmacy clinic. Each year, 4 NP residents, 2 health psychology residents, 4 clinical pharmacy residents, and 1 geriatric pharmacy resident participate in the IMPROVE clinic during their yearlong training program. During their 3-year training program, 17 to 19 internal medicine residents participate in IMPROVE.

A structured forum for discussing patients and their care options supports professionals’ utilization of the full scope of their practice. Trainees learn and apply team skills, such as communication and the warm handoff, which can be used in other clinic settings. A warm handoff is often described as an intervention in which “a clinician directly introduces a patient to another clinician at the time of the patient’s visit and often a brief encounter between the patient and the health care professional occurs.”9 An interprofessional care plan supports trainee clinical performance, providing a more robust approach to patient care than individual providers might on their own.

Patient Outcomes

IMPROVE is an enriched care plan informed by multiple professions with the potential to improve medication use and provide better care. Veterans also are receiving better medication education as well as access to a health psychologist who can help them with goal setting and effective behavioral interventions. On average, 5 patients participate each month. As of December 2015, 68 patients have participated in IMPROVE.

The group visit and the 1:1 patient visits focus exclusively on medication issues and solutions, which would be less common in a typical primary care visit with a complex patient who brings a list of agenda items. In addition to taking a thorough look at their medications and related problems, it also educates patients on related issues such as sleep hygiene. Participating veterans also are encouraged to share their concerns, experiences, and solutions with the group, which may increase the saliency of the message beyond what is offered in counseling from a provider.

To date, preliminary data suggest that in some patients, cognition (as measured with SLUMS after 6 months) has modestly improved after decreasing their medications. Other outcomes being monitored in follow-up are utilization of care, reported history of falls, number of medications, and vital signs at initial and follow-up visits.

Patients experience increased continuity of care because the patient now has a team focusing on his or her care. Team members have a shared understanding of the patient’s situation and are better able to establish therapeutic rapport with patients during the group visit. Moreover, CoEPCE trainees and faculty try to ensure that everyone knows about and concurs with medication changes, including outside providers and family members.

Satisfaction Questionnaire

Patients that are presented at IMPROVE can be particularly challenging, and there may be a psychological benefit to working with a team to develop a new care plan. Providers are able to get input and look at the patient in a new light.

Results of postvisit patient satisfaction questionnaires are encouraging and result in a high level of patient satisfaction and perception of clinical benefit. Patients identify an improvement in the understanding of their medications, feel they are able to safely decrease their medications, and are interested in participating again.

CoEPCE Benefits

IMPROVE expands the prevention and treatment options for populations at risk of hospitalization and adverse outcomes from medication complications, such as AEs and drug-drug or drug-disease interactions. Embedding the polypharmacy clinic within the primary care setting rather than in a separate specialty clinic results in an increased likelihood of implementation of pharmacist and geriatrician recommendations for polypharmacy and allows for direct interprofessional education and collaboration.

IMPROVE also combines key components of interprofessional education—an enriched clinical training model and knowledge of medications in an elderly population—into a training activity that complements other CoEPCE activities. The model not only has strengthened CoEPCE partnerships with other VA departments and specialties, but also revealed opportunities for collaboration with academic affiliates as a means to break down traditional silos among medicine, nursing, pharmacy, geriatrics, and psychology.

IMPROVE combines key components of interprofessional education, including all 4 CoEPCE core domains, to provide hands-on experience with knowledge learned in other aspects of the CoEPCE training program (eg, shared decision-making strategies for eliciting patient goals, weighing risks and benefits in complex clinical situations). Physician and NP trainees work together with trainees in pharmacy and health psychology in the complex approach to polypharmacy. IMPROVE provides the framework for an interprofessional clinic that could be used in the treatment of other complex or high-risk chronic conditions.

The Future

An opportunity for improvement and expansion includes increased patient involvement (as patients continue to learn they have a team working on their behalf). Opportunities exist to connect with patients who have several clinicians prescribing medications outside the CoEPCE to provide comprehensive care and decrease medication complexity.

The CoEPCE has been proactive in increasing the visibility of IMPROVE through multiple presentations at local and national meetings, facilitating collaborations and greater adoption in primary care. Individual and collective IMPROVE components can be adapted to other contexts. For example, the 20-minute geriatrics education session and the forms completed prior and during the patient visit can be readily applied to other complex patients that trainees meet in clinic. Under stage 2 of the CoEPCE program, the CoEPCE is developing an implementation kit that describes the training process and includes the medication worksheet, assessment tools, and directions for conducting the group visit.

It is hoped that working collaboratively with the West Haven COEPCE polypharmacy faculty, a similar model of education and training will be implemented at other health professional training sites at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Additionally, the West Haven CoEPCE is planning to partner with the other original CoEPCE program sites to implement similar interprofessional polypharmacy clinics.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Research and Quality. Transforming the organization and delivery of primary care. http://www.pcmh.ahrq .gov/. Accessed August 14, 2018.

2. Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818-1831.

3. Fried TR, O’Leary J, Towle V, Goldstein MK, Trentalange M, Martin DK. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2261-2272.

4. Mecca M, Niehoff K, Grammas M. Medication review worksheet 2015. http://pogoe.org/productid/21872. Accessed August 14, 2018.

5. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers criteria update expert panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

6. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218.

7. Yale University. IMPROVE Polypharmacy Project. http://improvepolypharmacy.yale.edu. Accessed August 14, 2018.

8. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH III, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910.

9. Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Davis M, et al. Understanding care integration from the ground up: Five organizing constructs that shape integrated practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(suppl):S7-S20.

An interprofessional polypharmacy clinic for intensive management of medication regimens helps high-risk patients manage their medications.

An interprofessional polypharmacy clinic for intensive management of medication regimens helps high-risk patients manage their medications.

In 2011, 5 VA medical centers (VAMCs) were selected by the Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish CoEPCE. Part of the VA New Models of Care initiative, the 5 Centers of Excellence (CoE) in Boise, Idaho; Cleveland, Ohio; San Francisco, California; Seattle, Washington; and West Haven, Connecticut, are utilizing VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents and students, advanced practice nurse residents and undergraduate nursing students, and other professions of health trainees (eg, pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants [PAs], physical therapists) for primary care practice in the 21st century. The CoEs are developing, implementing, and evaluating curricula designed to prepare learners from relevant professions to practice in patient-centered, interprofessional team-based primary care settings. The curricula at all CoEs must address 4 core domains (Table).

Health care professional education programs do not have many opportunities for workplace learning where trainees from different professions can learn and work together to provide care to patients in real time.

The VA Connecticut Healthcare System CoEPCE developed and implemented an education and practice-based immersion learning model with physician residents, nurse practitioner (NP) residents and NP students, pharmacy residents, postdoctorate psychology learners, and PA and physical therapy learners and faculty. This interprofessional, collaborative team model breaks from the traditional independent model of siloed primary care providers (PCPs) caring for a panel of patients.

Methods

In 2015, OAA evaluators reviewed background documents and conducted open-ended interviews with 12 West Haven CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, VA faculty, VA facility leadership, and affiliate faculty. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the Initiative to Minimize Pharmaceutical Risk in Older Veterans (IMPROVE) program to trainees, veterans, and the VA.

Lack of Clinical Approaches to Interprofessional Education and Care

Polypharmacy is a common problem among older adults with multiple chronic conditions, which places patients at higher risk for multiple negative health outcomes.2,3 The typical primary care visit rarely allows for a thorough review of a patient’s medications, much less the identification of strategies to reduce polypharmacy and improve medication management. Rather, the complexity inherent to polypharmacy makes it an ideal challenge for a team-based approach.

Team Approach to Medication Needs

A key CoEPCE program aim is to expand workplace learning instruction strategies and to create more clinical opportunities for CoEPCE trainees to work together as a team to anticipate and address the health care needs of veterans. To address this training need, the West Haven CoEPCE developed IMPROVE to focus on high-need patients and provides a venue in which trainees and supervisors from different professions can collaborate on a specific patient case, using a patient-centered framework. IMPROVE can be easily applied to a range of medication-related aims, such as reducing medications, managing medications and adherence, and addressing adverse effects (AEs). These goals are 2-fold: (1) implement a trainee-led performance improvement project that reduces polypharmacy in elderly veterans; and (2) develop a hands-on, experiential geriatrics training program that enhances trainee skills and knowledge related to safe prescribing.

Planning and Implementation

IMPROVE has its origins in a scholarly project developed by a West Haven CoE physician resident trainee. Development of the IMPROVE program involved VA health psychology, internal medicine faculty, geriatric medicine faculty, NP faculty, and geriatric pharmacy residents and faculty. Planning started in 2013 with a series of pilot clinics and became an official project of the West Haven CoE in September 2014. The intervention required no change in West Haven VAMC policy. However, the initiative required buy-in from West Haven CoE leadership and the director of the West Haven primary care clinic.

Curriculum

IMPROVE is an educational, workplace learning, and clinical activity that combines a 1-hour trainee teaching session, a 45-minute group visit, and a 60-minute individual clinic visit to address the complex problem of polypharmacy. It emphasizes the sharing of trainee and faculty backgrounds by serving as a venue for interprofessional trainees and providers to discuss pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment in the elderly and brainstorm strategies to optimize treatment regimens, minimize risk, and execute medication plans with patients.