User login

Why Aren’t More Primary Care Physicians Prescribing Contraceptives?

In 2024, the Guttmacher Institute reported that eight states enacted or proposed limits on contraceptive access. Currently, more than 19 million women aged 13-44 years in the United States live in “contraceptive deserts” or places that lack access to a full range of birth control methods. About 1.2 million of those women live in counties that don’t have a single health center that has complete birth control services.

Providing contraceptive care in primary care settings has long been deemed a best practice by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But the percentage of primary care physicians (PCPs) prescribing contraception or offering contraceptive procedures is strikingly low.

Only Half of Family Physicians (FPs) Prescribe Contraceptives

Research by Candice Chen, MD, MPH, and colleagues found that while 73.1% of obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs) and 72.6% of nurse-midwives prescribed the pill, patch, or vaginal ring; only 51% of FPs, 32.4% of pediatricians, and 19.8% of internal medicine physicians did so. And while 92.8% of OB/GYNs provided intrauterine device (IUD) services, only 16.4% of FPs, 2.6% of internists, and 0.6% of pediatricians did so.

One reason primary care is positioned so well to fill contraception gaps is found in the sheer numbers of PCPs. Chen and colleagues found that while the percentage of FPs prescribing contraception was much smaller (51.4%) than the percentage of OB/GYN prescribers (72.6%), the numbers translate to 72,725 FPs prescribing contraceptives, which is nearly double the number of OB/GYNs prescribing them (36,887).

Access to contraception services took a big hit with the COVID-19 pandemic as did access to healthcare in general. And the 2022 Supreme Court ruling that struck down Roe V. Wade has shaken up the landscape for reproductive services with potential consequences for contraceptive access.

Why Aren’t More PCPs Offering Contraceptive Services?

Reasons for the relatively low numbers of PCPs prescribing contraceptives include lack of training in residency, health systems’ financial choices, insurance barriers, and expectation by some physicians and many patients that birth control belongs in the OB/GYN sector. Access, patient awareness that PCPs can provide the care, expectations, and options vary by states and regions.

Angeline Ti, MD, an FP who teaches in a residency program at Wellstar Douglasville Medical Center in Douglasville, Georgia, told this news organization that the awareness issue might be the easiest change for PCPs as many patients aren’t aware you can get contraceptive services in primary care.

Things PCPs ‘Could Do Tomorrow’

Those physicians who want to add those services might want to start with universal screening, Ti said — having conversations with patients about contraceptive needs and letting them know they don’t have to get those prescriptions from an OB/GYN. The conversations could center on laying out the options and counseling on risks and benefits of various options and providing referrals, if that is the best option. “There are definitely things that you could do tomorrow,” she said.

PCPs should be familiar with the CDC’s Contraceptive Guidance for Health Care Providers and the federal Office of Population Affairs’ Quality Family Planning Recommendations for providers, which offer practice-level information, Ti said.

PCPs should not feel they need to be able to provide same-day contraceptive care to get started. Having nurses and medical assistants and practice managers on board who are passionate about adding the services can also help bring about change with a team approach, she said.

Even when the provider is enthusiastic about providing the care and is trained to do so, however, insurance barriers may exist, Ti acknowledged. For example, at her clinic a common IUD insertion requires prior authorization.

Including Other Providers

Julia Strasser, DrPH, MPH, a member of the core faculty at the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity in Washington, DC, told this news organization that including other clinicians could help expand contraceptive services in primary care. Her research showed that the proportion of the contraception workforce that is made up of advanced practice clinicians and nurse practitioners is increasing, whereas the proportion that includes physicians is either static or declining.

A paper by her team found that although OB/GYNs and nurse-midwives were more likely to prescribe the pill, patch, or ring, the largest numbers of contraception prescribers were FPs (72,725) and advanced practice nurses (70,115).

“We also know that pharmacists can safely prescribe contraception, and some states have authorized this practice, but uptake is low and policies vary by state,” she said. “Some health systems have pharmacists embedded in their practice — for example in federally qualified health centers and others.”

It’s important, she said, not to frame the gaps in contraceptive care as a failure on the part of individual clinicians but rather as: “How can we change some of the system-level factors that have gotten us to this point?”

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, an FP and director of the Robert Graham Center of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said sometimes it’s the health center’s cost analysis that stands in the way. She gave an example from her own health system.

“The health system doesn’t want to pay for us to have the IUDs stored in our offices and provide that procedure because they feel it’s more cost effective if the OB/GYNs do it.” IUD insertions take more appointment time than the standard appointment, which also goes into the cost analysis. “Even though you’re trained to do it, you can’t necessarily do it when you get to the real world,” Jabbarpour said.

She said the thinking is that while OB/GYNs focus on women, FPs cover all ages and family members, so having the equipment and the storage space is best left to the OB/GYNs. She said that thinking may be short sighted.

“We have good data that the highest number of office visits in the United States actually happen in the family physician’s office,” she said. Not providing the services injects a barrier into the system as women are being referred for a simple procedure to a physician they’ve never seen. “That’s not very patient centered,” Jabbarpour noted.

In systems that refer contraceptive procedures to OB/GYNs, doctors also can’t practice skills they learned in residency and then may not feel comfortable performing the procedures when they enter a health system that offers the procedures in primary care.

Number of FPs Prescribing Long-Acting Contraception Growing

Jabbarpour said there has been some improvement in that area in terms of long-acting reversible contraception.

She pointed to a study of recertifying FPs that found that the percent of FPs who offer either IUDs or implants increased from 23.9% in 2018 to 30% in 2022. The share of FPs providing implant insertion increased from 12.9% to 20.8%; those providing IUDs also increased from 22.9% to 25.5% from 2018 to 2022.

FPs also have the advantage of being more widely distributed in rural and remote areas than OB/GYNs, she noted. “They are in almost every county in the United States.”

Jabbarpour said the education must start with health system leaders. If they deem it important to offer these services in primary care, then residency programs will see that their residents must be appropriately trained to provide it.

“Right now, it’s not an expectation of many of the employers that primary care physicians should do this,” she said.

Ti said that expectation should change. The value proposition for all PCPs and health systems, she said, is this: “Most of contraceptive care is well within the scope of primary care providers. This is care that we can do, and it’s care that we should be doing. So why aren’t we doing it?”

Ti, Strasser, and Jabbarpour reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2024, the Guttmacher Institute reported that eight states enacted or proposed limits on contraceptive access. Currently, more than 19 million women aged 13-44 years in the United States live in “contraceptive deserts” or places that lack access to a full range of birth control methods. About 1.2 million of those women live in counties that don’t have a single health center that has complete birth control services.

Providing contraceptive care in primary care settings has long been deemed a best practice by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But the percentage of primary care physicians (PCPs) prescribing contraception or offering contraceptive procedures is strikingly low.

Only Half of Family Physicians (FPs) Prescribe Contraceptives

Research by Candice Chen, MD, MPH, and colleagues found that while 73.1% of obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs) and 72.6% of nurse-midwives prescribed the pill, patch, or vaginal ring; only 51% of FPs, 32.4% of pediatricians, and 19.8% of internal medicine physicians did so. And while 92.8% of OB/GYNs provided intrauterine device (IUD) services, only 16.4% of FPs, 2.6% of internists, and 0.6% of pediatricians did so.

One reason primary care is positioned so well to fill contraception gaps is found in the sheer numbers of PCPs. Chen and colleagues found that while the percentage of FPs prescribing contraception was much smaller (51.4%) than the percentage of OB/GYN prescribers (72.6%), the numbers translate to 72,725 FPs prescribing contraceptives, which is nearly double the number of OB/GYNs prescribing them (36,887).

Access to contraception services took a big hit with the COVID-19 pandemic as did access to healthcare in general. And the 2022 Supreme Court ruling that struck down Roe V. Wade has shaken up the landscape for reproductive services with potential consequences for contraceptive access.

Why Aren’t More PCPs Offering Contraceptive Services?

Reasons for the relatively low numbers of PCPs prescribing contraceptives include lack of training in residency, health systems’ financial choices, insurance barriers, and expectation by some physicians and many patients that birth control belongs in the OB/GYN sector. Access, patient awareness that PCPs can provide the care, expectations, and options vary by states and regions.

Angeline Ti, MD, an FP who teaches in a residency program at Wellstar Douglasville Medical Center in Douglasville, Georgia, told this news organization that the awareness issue might be the easiest change for PCPs as many patients aren’t aware you can get contraceptive services in primary care.

Things PCPs ‘Could Do Tomorrow’

Those physicians who want to add those services might want to start with universal screening, Ti said — having conversations with patients about contraceptive needs and letting them know they don’t have to get those prescriptions from an OB/GYN. The conversations could center on laying out the options and counseling on risks and benefits of various options and providing referrals, if that is the best option. “There are definitely things that you could do tomorrow,” she said.

PCPs should be familiar with the CDC’s Contraceptive Guidance for Health Care Providers and the federal Office of Population Affairs’ Quality Family Planning Recommendations for providers, which offer practice-level information, Ti said.

PCPs should not feel they need to be able to provide same-day contraceptive care to get started. Having nurses and medical assistants and practice managers on board who are passionate about adding the services can also help bring about change with a team approach, she said.

Even when the provider is enthusiastic about providing the care and is trained to do so, however, insurance barriers may exist, Ti acknowledged. For example, at her clinic a common IUD insertion requires prior authorization.

Including Other Providers

Julia Strasser, DrPH, MPH, a member of the core faculty at the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity in Washington, DC, told this news organization that including other clinicians could help expand contraceptive services in primary care. Her research showed that the proportion of the contraception workforce that is made up of advanced practice clinicians and nurse practitioners is increasing, whereas the proportion that includes physicians is either static or declining.

A paper by her team found that although OB/GYNs and nurse-midwives were more likely to prescribe the pill, patch, or ring, the largest numbers of contraception prescribers were FPs (72,725) and advanced practice nurses (70,115).

“We also know that pharmacists can safely prescribe contraception, and some states have authorized this practice, but uptake is low and policies vary by state,” she said. “Some health systems have pharmacists embedded in their practice — for example in federally qualified health centers and others.”

It’s important, she said, not to frame the gaps in contraceptive care as a failure on the part of individual clinicians but rather as: “How can we change some of the system-level factors that have gotten us to this point?”

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, an FP and director of the Robert Graham Center of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said sometimes it’s the health center’s cost analysis that stands in the way. She gave an example from her own health system.

“The health system doesn’t want to pay for us to have the IUDs stored in our offices and provide that procedure because they feel it’s more cost effective if the OB/GYNs do it.” IUD insertions take more appointment time than the standard appointment, which also goes into the cost analysis. “Even though you’re trained to do it, you can’t necessarily do it when you get to the real world,” Jabbarpour said.

She said the thinking is that while OB/GYNs focus on women, FPs cover all ages and family members, so having the equipment and the storage space is best left to the OB/GYNs. She said that thinking may be short sighted.

“We have good data that the highest number of office visits in the United States actually happen in the family physician’s office,” she said. Not providing the services injects a barrier into the system as women are being referred for a simple procedure to a physician they’ve never seen. “That’s not very patient centered,” Jabbarpour noted.

In systems that refer contraceptive procedures to OB/GYNs, doctors also can’t practice skills they learned in residency and then may not feel comfortable performing the procedures when they enter a health system that offers the procedures in primary care.

Number of FPs Prescribing Long-Acting Contraception Growing

Jabbarpour said there has been some improvement in that area in terms of long-acting reversible contraception.

She pointed to a study of recertifying FPs that found that the percent of FPs who offer either IUDs or implants increased from 23.9% in 2018 to 30% in 2022. The share of FPs providing implant insertion increased from 12.9% to 20.8%; those providing IUDs also increased from 22.9% to 25.5% from 2018 to 2022.

FPs also have the advantage of being more widely distributed in rural and remote areas than OB/GYNs, she noted. “They are in almost every county in the United States.”

Jabbarpour said the education must start with health system leaders. If they deem it important to offer these services in primary care, then residency programs will see that their residents must be appropriately trained to provide it.

“Right now, it’s not an expectation of many of the employers that primary care physicians should do this,” she said.

Ti said that expectation should change. The value proposition for all PCPs and health systems, she said, is this: “Most of contraceptive care is well within the scope of primary care providers. This is care that we can do, and it’s care that we should be doing. So why aren’t we doing it?”

Ti, Strasser, and Jabbarpour reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2024, the Guttmacher Institute reported that eight states enacted or proposed limits on contraceptive access. Currently, more than 19 million women aged 13-44 years in the United States live in “contraceptive deserts” or places that lack access to a full range of birth control methods. About 1.2 million of those women live in counties that don’t have a single health center that has complete birth control services.

Providing contraceptive care in primary care settings has long been deemed a best practice by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But the percentage of primary care physicians (PCPs) prescribing contraception or offering contraceptive procedures is strikingly low.

Only Half of Family Physicians (FPs) Prescribe Contraceptives

Research by Candice Chen, MD, MPH, and colleagues found that while 73.1% of obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs) and 72.6% of nurse-midwives prescribed the pill, patch, or vaginal ring; only 51% of FPs, 32.4% of pediatricians, and 19.8% of internal medicine physicians did so. And while 92.8% of OB/GYNs provided intrauterine device (IUD) services, only 16.4% of FPs, 2.6% of internists, and 0.6% of pediatricians did so.

One reason primary care is positioned so well to fill contraception gaps is found in the sheer numbers of PCPs. Chen and colleagues found that while the percentage of FPs prescribing contraception was much smaller (51.4%) than the percentage of OB/GYN prescribers (72.6%), the numbers translate to 72,725 FPs prescribing contraceptives, which is nearly double the number of OB/GYNs prescribing them (36,887).

Access to contraception services took a big hit with the COVID-19 pandemic as did access to healthcare in general. And the 2022 Supreme Court ruling that struck down Roe V. Wade has shaken up the landscape for reproductive services with potential consequences for contraceptive access.

Why Aren’t More PCPs Offering Contraceptive Services?

Reasons for the relatively low numbers of PCPs prescribing contraceptives include lack of training in residency, health systems’ financial choices, insurance barriers, and expectation by some physicians and many patients that birth control belongs in the OB/GYN sector. Access, patient awareness that PCPs can provide the care, expectations, and options vary by states and regions.

Angeline Ti, MD, an FP who teaches in a residency program at Wellstar Douglasville Medical Center in Douglasville, Georgia, told this news organization that the awareness issue might be the easiest change for PCPs as many patients aren’t aware you can get contraceptive services in primary care.

Things PCPs ‘Could Do Tomorrow’

Those physicians who want to add those services might want to start with universal screening, Ti said — having conversations with patients about contraceptive needs and letting them know they don’t have to get those prescriptions from an OB/GYN. The conversations could center on laying out the options and counseling on risks and benefits of various options and providing referrals, if that is the best option. “There are definitely things that you could do tomorrow,” she said.

PCPs should be familiar with the CDC’s Contraceptive Guidance for Health Care Providers and the federal Office of Population Affairs’ Quality Family Planning Recommendations for providers, which offer practice-level information, Ti said.

PCPs should not feel they need to be able to provide same-day contraceptive care to get started. Having nurses and medical assistants and practice managers on board who are passionate about adding the services can also help bring about change with a team approach, she said.

Even when the provider is enthusiastic about providing the care and is trained to do so, however, insurance barriers may exist, Ti acknowledged. For example, at her clinic a common IUD insertion requires prior authorization.

Including Other Providers

Julia Strasser, DrPH, MPH, a member of the core faculty at the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity in Washington, DC, told this news organization that including other clinicians could help expand contraceptive services in primary care. Her research showed that the proportion of the contraception workforce that is made up of advanced practice clinicians and nurse practitioners is increasing, whereas the proportion that includes physicians is either static or declining.

A paper by her team found that although OB/GYNs and nurse-midwives were more likely to prescribe the pill, patch, or ring, the largest numbers of contraception prescribers were FPs (72,725) and advanced practice nurses (70,115).

“We also know that pharmacists can safely prescribe contraception, and some states have authorized this practice, but uptake is low and policies vary by state,” she said. “Some health systems have pharmacists embedded in their practice — for example in federally qualified health centers and others.”

It’s important, she said, not to frame the gaps in contraceptive care as a failure on the part of individual clinicians but rather as: “How can we change some of the system-level factors that have gotten us to this point?”

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, an FP and director of the Robert Graham Center of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said sometimes it’s the health center’s cost analysis that stands in the way. She gave an example from her own health system.

“The health system doesn’t want to pay for us to have the IUDs stored in our offices and provide that procedure because they feel it’s more cost effective if the OB/GYNs do it.” IUD insertions take more appointment time than the standard appointment, which also goes into the cost analysis. “Even though you’re trained to do it, you can’t necessarily do it when you get to the real world,” Jabbarpour said.

She said the thinking is that while OB/GYNs focus on women, FPs cover all ages and family members, so having the equipment and the storage space is best left to the OB/GYNs. She said that thinking may be short sighted.

“We have good data that the highest number of office visits in the United States actually happen in the family physician’s office,” she said. Not providing the services injects a barrier into the system as women are being referred for a simple procedure to a physician they’ve never seen. “That’s not very patient centered,” Jabbarpour noted.

In systems that refer contraceptive procedures to OB/GYNs, doctors also can’t practice skills they learned in residency and then may not feel comfortable performing the procedures when they enter a health system that offers the procedures in primary care.

Number of FPs Prescribing Long-Acting Contraception Growing

Jabbarpour said there has been some improvement in that area in terms of long-acting reversible contraception.

She pointed to a study of recertifying FPs that found that the percent of FPs who offer either IUDs or implants increased from 23.9% in 2018 to 30% in 2022. The share of FPs providing implant insertion increased from 12.9% to 20.8%; those providing IUDs also increased from 22.9% to 25.5% from 2018 to 2022.

FPs also have the advantage of being more widely distributed in rural and remote areas than OB/GYNs, she noted. “They are in almost every county in the United States.”

Jabbarpour said the education must start with health system leaders. If they deem it important to offer these services in primary care, then residency programs will see that their residents must be appropriately trained to provide it.

“Right now, it’s not an expectation of many of the employers that primary care physicians should do this,” she said.

Ti said that expectation should change. The value proposition for all PCPs and health systems, she said, is this: “Most of contraceptive care is well within the scope of primary care providers. This is care that we can do, and it’s care that we should be doing. So why aren’t we doing it?”

Ti, Strasser, and Jabbarpour reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ADHD Myths

In the second half of the school year, you may find that there is a surge of families coming to appointments with concerns about school performance, wondering if their child has ADHD. We expect you are very familiar with this condition, both diagnosing and treating it. So this month we will offer “mythbusters” for ADHD: Responding to common misperceptions about ADHD with a summary of what the research has demonstrated as emerging facts, what is clearly fiction and what falls into the gray space between.

Demographics

A CDC survey of parents from 2022 indicates that 11.4% of children aged 3-17 have ever been diagnosed with ADHD in the United States. This is more than double the ADHD global prevalence of 5%, suggesting that there is overdiagnosis of this condition in this country. Boys are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed (14.5%) as girls (8%), and White children were more likely to be diagnosed than were Black and Hispanic children. The prevalence of ADHD diagnosis decreases as family income increases, and the condition is more frequently diagnosed in 12- to 17-year-olds than in children 11 and younger. The great majority of youth with an ADHD diagnosis (78%) have at least one co-occurring psychiatric condition. Of the children diagnosed with ADHD, slightly over half receive medication treatment (53.6%) whereas nearly a third (30.1%) receive no ADHD-specific treatment.

The Multimodal Treatment of ADHD Study (MTA), a large (600 children, aged 7-9 years), multicenter, longitudinal study of treatment outcomes for medication as well as behavioral and combination therapies demonstrated in every site that medication alone and combination therapy were significantly superior to intensive behavioral treatment alone and to routine community care in the reduction of ADHD symptoms. Of note, problems commonly associated with ADHD (parent-child conflict, anxiety symptoms, poor academic performance, and limited social skills) improved only with the combination treatment. This suggests that while core ADHD symptoms require medication, associated problems will also require behavioral treatment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has a useful resource guide (healthychildren.org) highlighting the possible symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that should be investigated when considering this diagnosis. It is a clinical diagnosis, but screening instruments (such as the Vanderbilt) can be very helpful to identifying symptoms that should be present in more than one setting (home and school). While a child with ADHD can appear calm and focused when receiving direct one-to-one attention (as during a pediatrician’s appointment), symptoms may flourish in less structured or supervised settings. Sometimes parents are keen reporters of a child’s behaviors, but some loving (and exhausted) parents may overreact to a normal degree of inattention or disobedience. This can be especially true when a parent has a more detail-oriented temperament than the child, or with younger children and first-time parents. It is important to consider ADHD when you hear about social difficulties as well as academic ones, where there is a family history of ADHD or when a child is more impulsive, hyperactive, or inattentive than you would expect given their age and developmental stage. Confirm your clinical exam with teacher and parent reports. If the reports don’t line up or there are persistent learning problems in school, consider neuropsychological testing to root out a learning disability.

Myth 1: “ADHD never starts in adolescence; you can’t diagnose it after elementary school.”

Diagnostic criteria used to require that symptoms were present before the age of 7 (DSM 3). But current criteria allow for diagnosis before 12 years of age or after. While the consensus is that ADHD is present in childhood, its symptoms are often not apparent. This is because normal development in much younger children is marked by higher levels of activity, distractibility, and impulsivity. Also, children with inattentive-type ADHD may not be apparent to adults if they are performing adequately in school. These youth often do not present for assessment until the challenges of a busy course load make their inattention and consequent inefficiency apparent, in high school or even college. Certainly, when a teenager presents complaining of trouble performing at school, it is critical to rule out an overburdened schedule, anxiety or mood disorder, poor sleep habits or sleep disorder, and substance use disorders, all of which are more common in adolescence. But inattentive-type ADHD that was previously missed is also a possibility worth investigating.

Myth 2: “Most children outgrow ADHD; it’s best to find natural solutions and wait it out.”

Early epidemiological studies suggested that as many as 30% of ADHD cases remitted by adulthood, but more recent data has adjusted that number down substantially, closer to 9%. Interestingly, it appears that 10% of patients will experience sustained symptoms, 9% will experience recovery (sustained remission without treatment), and a large majority will have a remitting and relapsing course into adulthood.1

This emerging evidence suggests that ADHD is almost always a lifelong condition. Untreated, it can threaten healthy development (including social skills and self-esteem) and day-to-day function (academic, social and athletic performance and even vulnerability to accidents) in ways that can be profound. The MTA Study has powerfully demonstrated the efficacy of pharmacological treatment and of specific behavioral treatments for ADHD and associated problems.

Myth 3: “You should exhaust natural cures first before trying medications.”

There has been a large amount of research into a variety of “natural” treatments for ADHD: special diets, supplements, increased exercise, and interventions like neurofeedback. While high-dose omega 3 fatty acid supplementation has demonstrated mild improvement in ADHD symptoms, no “natural” treatment has come close to the efficacy of stimulant medications. Interventions such as neurofeedback are expensive and time-consuming without any demonstrated efficacy. That said, improving a child’s routines around sleep, nutrition, and regular exercise are broadly useful strategies to improve any child’s (or adult’s) energy, impulse control, attention, motivation, and capacity to manage adversity and stress. Start any treatment by addressing sleep and exercise, including moderating time spent on screens, to support healthy function. But only medication will achieve symptom remission if your patient has underlying ADHD.

Myth 4: “All medications are equally effective in ADHD.”

It is well-established that stimulants are more effective than non-stimulants in the treatment of ADHD symptoms, with an effect size that is almost double that of non-stimulants.2

Amphetamine-based medications are slightly more effective than methylphenidate-based medications, but they are also generally less well-tolerated. Individual patients commonly have a better response to one class than the other, but you will need a trial to determine which one. It is reasonable to start a patient with an extended formulation of one class, based on your assessment of their vulnerability to side effects or a family history of medication response. Non-stimulants are of use when stimulants are not tolerated (ie, use of atomoxetine with patients who have comorbid anxiety), or to target specific symptoms, such as guanfacine or clonidine for hyperactivity.

Myth 5: “You can’t treat ADHD in substance abusing teens, stimulant medications are addictive.”

ADHD itself (not medications) increases the risk for addiction; those with ADHD are almost twice as likely to develop a substance use disorder, with highest risk for marijuana, alcohol, and nicotine abuse.3

This may be a function of limited impulse control or increased sensitivity in the ADHD brain to a drug’s addictive potential. Importantly, there is growing evidence that youth whose ADHD is treated pharmacologically are at lower risk for addiction than their peers with untreated ADHD.4

Those youth who have both ADHD and addiction are more likely to stay engaged in treatment for addiction when their ADHD is effectively treated, and there are medication formulations (lisdexamfetamine) that are safe in addiction (cannot be absorbed nasally or intravenously). It is important for you to talk about the heightened vulnerability to addiction with your ADHD patients and their parents, and the value of effective treatment in preventing this complication.

Myth 6: “ADHD is usually behavioral. Help parents to set rules, expectations, and limits instead of medicating the problem.”

Bad parenting does not cause ADHD. ADHD is marked by difficulties with impulse control, hyperactivity, and sustaining attention with matters that are not intrinsically engaging. “Behavioral issues” are patterns of behavior children learn to seek rewards or avoid negative consequences. Youth with ADHD can develop behavioral problems, but these are usually driven by negative feedback about their activity level, forgetfulness, or impulse control, which they are not able to change. This can lead to frustration and irritability, poor self-esteem, and even hopelessness — in parents and children both!

While parents are not the source of ADHD symptoms, there is a great deal of parent education and support that can be powerfully effective for these families. Parents benefit from learning strategies that can help their children to shift their attention, plan ahead, and manage frustration, especially for times when their children are unmedicated (vacations and bedtime). It is worth noting that ADHD is among the most heritable of youth psychiatric illnesses, so it is not uncommon for a parent of a child with ADHD to have similar symptoms. If the parents’ ADHD is untreated, they may be more impulsive themselves. They may also be extra sensitive to the qualities they dislike in themselves, inadvertently adding to their children’s sense of shame. ADHD is very treatable, and those with it can learn executive function skills and organizational strategies that can equip them to manage residual symptoms. Parents will benefit from strategies to understand their children and to help them learn adaptive skills in a realistic way. Your discussions with parents could help the families in your practice make adjustments that can translate into big differences in their child’s healthiest development.

Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Sibley MH et al. MTA Cooperative Group. Variable Patterns of Remission From ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022 Feb;179(2):142-151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032.

2. Cortese S et al. Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of Medications for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;5(9):727-738. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4.

3. Lee SS et al. Prospective Association of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Substance Use and Abuse/Dependence: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011 Apr;31(3):328-41. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006.

4. Chorniy A, Kitashima L. Sex, Drugs, and ADHD: The Effects of ADHD Pharmacological Treatment on Teens’ Risky Behaviors. Labour Economics. 2016;43:87-105. doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.06.014.

In the second half of the school year, you may find that there is a surge of families coming to appointments with concerns about school performance, wondering if their child has ADHD. We expect you are very familiar with this condition, both diagnosing and treating it. So this month we will offer “mythbusters” for ADHD: Responding to common misperceptions about ADHD with a summary of what the research has demonstrated as emerging facts, what is clearly fiction and what falls into the gray space between.

Demographics

A CDC survey of parents from 2022 indicates that 11.4% of children aged 3-17 have ever been diagnosed with ADHD in the United States. This is more than double the ADHD global prevalence of 5%, suggesting that there is overdiagnosis of this condition in this country. Boys are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed (14.5%) as girls (8%), and White children were more likely to be diagnosed than were Black and Hispanic children. The prevalence of ADHD diagnosis decreases as family income increases, and the condition is more frequently diagnosed in 12- to 17-year-olds than in children 11 and younger. The great majority of youth with an ADHD diagnosis (78%) have at least one co-occurring psychiatric condition. Of the children diagnosed with ADHD, slightly over half receive medication treatment (53.6%) whereas nearly a third (30.1%) receive no ADHD-specific treatment.

The Multimodal Treatment of ADHD Study (MTA), a large (600 children, aged 7-9 years), multicenter, longitudinal study of treatment outcomes for medication as well as behavioral and combination therapies demonstrated in every site that medication alone and combination therapy were significantly superior to intensive behavioral treatment alone and to routine community care in the reduction of ADHD symptoms. Of note, problems commonly associated with ADHD (parent-child conflict, anxiety symptoms, poor academic performance, and limited social skills) improved only with the combination treatment. This suggests that while core ADHD symptoms require medication, associated problems will also require behavioral treatment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has a useful resource guide (healthychildren.org) highlighting the possible symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that should be investigated when considering this diagnosis. It is a clinical diagnosis, but screening instruments (such as the Vanderbilt) can be very helpful to identifying symptoms that should be present in more than one setting (home and school). While a child with ADHD can appear calm and focused when receiving direct one-to-one attention (as during a pediatrician’s appointment), symptoms may flourish in less structured or supervised settings. Sometimes parents are keen reporters of a child’s behaviors, but some loving (and exhausted) parents may overreact to a normal degree of inattention or disobedience. This can be especially true when a parent has a more detail-oriented temperament than the child, or with younger children and first-time parents. It is important to consider ADHD when you hear about social difficulties as well as academic ones, where there is a family history of ADHD or when a child is more impulsive, hyperactive, or inattentive than you would expect given their age and developmental stage. Confirm your clinical exam with teacher and parent reports. If the reports don’t line up or there are persistent learning problems in school, consider neuropsychological testing to root out a learning disability.

Myth 1: “ADHD never starts in adolescence; you can’t diagnose it after elementary school.”

Diagnostic criteria used to require that symptoms were present before the age of 7 (DSM 3). But current criteria allow for diagnosis before 12 years of age or after. While the consensus is that ADHD is present in childhood, its symptoms are often not apparent. This is because normal development in much younger children is marked by higher levels of activity, distractibility, and impulsivity. Also, children with inattentive-type ADHD may not be apparent to adults if they are performing adequately in school. These youth often do not present for assessment until the challenges of a busy course load make their inattention and consequent inefficiency apparent, in high school or even college. Certainly, when a teenager presents complaining of trouble performing at school, it is critical to rule out an overburdened schedule, anxiety or mood disorder, poor sleep habits or sleep disorder, and substance use disorders, all of which are more common in adolescence. But inattentive-type ADHD that was previously missed is also a possibility worth investigating.

Myth 2: “Most children outgrow ADHD; it’s best to find natural solutions and wait it out.”

Early epidemiological studies suggested that as many as 30% of ADHD cases remitted by adulthood, but more recent data has adjusted that number down substantially, closer to 9%. Interestingly, it appears that 10% of patients will experience sustained symptoms, 9% will experience recovery (sustained remission without treatment), and a large majority will have a remitting and relapsing course into adulthood.1

This emerging evidence suggests that ADHD is almost always a lifelong condition. Untreated, it can threaten healthy development (including social skills and self-esteem) and day-to-day function (academic, social and athletic performance and even vulnerability to accidents) in ways that can be profound. The MTA Study has powerfully demonstrated the efficacy of pharmacological treatment and of specific behavioral treatments for ADHD and associated problems.

Myth 3: “You should exhaust natural cures first before trying medications.”

There has been a large amount of research into a variety of “natural” treatments for ADHD: special diets, supplements, increased exercise, and interventions like neurofeedback. While high-dose omega 3 fatty acid supplementation has demonstrated mild improvement in ADHD symptoms, no “natural” treatment has come close to the efficacy of stimulant medications. Interventions such as neurofeedback are expensive and time-consuming without any demonstrated efficacy. That said, improving a child’s routines around sleep, nutrition, and regular exercise are broadly useful strategies to improve any child’s (or adult’s) energy, impulse control, attention, motivation, and capacity to manage adversity and stress. Start any treatment by addressing sleep and exercise, including moderating time spent on screens, to support healthy function. But only medication will achieve symptom remission if your patient has underlying ADHD.

Myth 4: “All medications are equally effective in ADHD.”

It is well-established that stimulants are more effective than non-stimulants in the treatment of ADHD symptoms, with an effect size that is almost double that of non-stimulants.2

Amphetamine-based medications are slightly more effective than methylphenidate-based medications, but they are also generally less well-tolerated. Individual patients commonly have a better response to one class than the other, but you will need a trial to determine which one. It is reasonable to start a patient with an extended formulation of one class, based on your assessment of their vulnerability to side effects or a family history of medication response. Non-stimulants are of use when stimulants are not tolerated (ie, use of atomoxetine with patients who have comorbid anxiety), or to target specific symptoms, such as guanfacine or clonidine for hyperactivity.

Myth 5: “You can’t treat ADHD in substance abusing teens, stimulant medications are addictive.”

ADHD itself (not medications) increases the risk for addiction; those with ADHD are almost twice as likely to develop a substance use disorder, with highest risk for marijuana, alcohol, and nicotine abuse.3

This may be a function of limited impulse control or increased sensitivity in the ADHD brain to a drug’s addictive potential. Importantly, there is growing evidence that youth whose ADHD is treated pharmacologically are at lower risk for addiction than their peers with untreated ADHD.4

Those youth who have both ADHD and addiction are more likely to stay engaged in treatment for addiction when their ADHD is effectively treated, and there are medication formulations (lisdexamfetamine) that are safe in addiction (cannot be absorbed nasally or intravenously). It is important for you to talk about the heightened vulnerability to addiction with your ADHD patients and their parents, and the value of effective treatment in preventing this complication.

Myth 6: “ADHD is usually behavioral. Help parents to set rules, expectations, and limits instead of medicating the problem.”

Bad parenting does not cause ADHD. ADHD is marked by difficulties with impulse control, hyperactivity, and sustaining attention with matters that are not intrinsically engaging. “Behavioral issues” are patterns of behavior children learn to seek rewards or avoid negative consequences. Youth with ADHD can develop behavioral problems, but these are usually driven by negative feedback about their activity level, forgetfulness, or impulse control, which they are not able to change. This can lead to frustration and irritability, poor self-esteem, and even hopelessness — in parents and children both!

While parents are not the source of ADHD symptoms, there is a great deal of parent education and support that can be powerfully effective for these families. Parents benefit from learning strategies that can help their children to shift their attention, plan ahead, and manage frustration, especially for times when their children are unmedicated (vacations and bedtime). It is worth noting that ADHD is among the most heritable of youth psychiatric illnesses, so it is not uncommon for a parent of a child with ADHD to have similar symptoms. If the parents’ ADHD is untreated, they may be more impulsive themselves. They may also be extra sensitive to the qualities they dislike in themselves, inadvertently adding to their children’s sense of shame. ADHD is very treatable, and those with it can learn executive function skills and organizational strategies that can equip them to manage residual symptoms. Parents will benefit from strategies to understand their children and to help them learn adaptive skills in a realistic way. Your discussions with parents could help the families in your practice make adjustments that can translate into big differences in their child’s healthiest development.

Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Sibley MH et al. MTA Cooperative Group. Variable Patterns of Remission From ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022 Feb;179(2):142-151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032.

2. Cortese S et al. Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of Medications for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;5(9):727-738. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4.

3. Lee SS et al. Prospective Association of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Substance Use and Abuse/Dependence: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011 Apr;31(3):328-41. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006.

4. Chorniy A, Kitashima L. Sex, Drugs, and ADHD: The Effects of ADHD Pharmacological Treatment on Teens’ Risky Behaviors. Labour Economics. 2016;43:87-105. doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.06.014.

In the second half of the school year, you may find that there is a surge of families coming to appointments with concerns about school performance, wondering if their child has ADHD. We expect you are very familiar with this condition, both diagnosing and treating it. So this month we will offer “mythbusters” for ADHD: Responding to common misperceptions about ADHD with a summary of what the research has demonstrated as emerging facts, what is clearly fiction and what falls into the gray space between.

Demographics

A CDC survey of parents from 2022 indicates that 11.4% of children aged 3-17 have ever been diagnosed with ADHD in the United States. This is more than double the ADHD global prevalence of 5%, suggesting that there is overdiagnosis of this condition in this country. Boys are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed (14.5%) as girls (8%), and White children were more likely to be diagnosed than were Black and Hispanic children. The prevalence of ADHD diagnosis decreases as family income increases, and the condition is more frequently diagnosed in 12- to 17-year-olds than in children 11 and younger. The great majority of youth with an ADHD diagnosis (78%) have at least one co-occurring psychiatric condition. Of the children diagnosed with ADHD, slightly over half receive medication treatment (53.6%) whereas nearly a third (30.1%) receive no ADHD-specific treatment.

The Multimodal Treatment of ADHD Study (MTA), a large (600 children, aged 7-9 years), multicenter, longitudinal study of treatment outcomes for medication as well as behavioral and combination therapies demonstrated in every site that medication alone and combination therapy were significantly superior to intensive behavioral treatment alone and to routine community care in the reduction of ADHD symptoms. Of note, problems commonly associated with ADHD (parent-child conflict, anxiety symptoms, poor academic performance, and limited social skills) improved only with the combination treatment. This suggests that while core ADHD symptoms require medication, associated problems will also require behavioral treatment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has a useful resource guide (healthychildren.org) highlighting the possible symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that should be investigated when considering this diagnosis. It is a clinical diagnosis, but screening instruments (such as the Vanderbilt) can be very helpful to identifying symptoms that should be present in more than one setting (home and school). While a child with ADHD can appear calm and focused when receiving direct one-to-one attention (as during a pediatrician’s appointment), symptoms may flourish in less structured or supervised settings. Sometimes parents are keen reporters of a child’s behaviors, but some loving (and exhausted) parents may overreact to a normal degree of inattention or disobedience. This can be especially true when a parent has a more detail-oriented temperament than the child, or with younger children and first-time parents. It is important to consider ADHD when you hear about social difficulties as well as academic ones, where there is a family history of ADHD or when a child is more impulsive, hyperactive, or inattentive than you would expect given their age and developmental stage. Confirm your clinical exam with teacher and parent reports. If the reports don’t line up or there are persistent learning problems in school, consider neuropsychological testing to root out a learning disability.

Myth 1: “ADHD never starts in adolescence; you can’t diagnose it after elementary school.”

Diagnostic criteria used to require that symptoms were present before the age of 7 (DSM 3). But current criteria allow for diagnosis before 12 years of age or after. While the consensus is that ADHD is present in childhood, its symptoms are often not apparent. This is because normal development in much younger children is marked by higher levels of activity, distractibility, and impulsivity. Also, children with inattentive-type ADHD may not be apparent to adults if they are performing adequately in school. These youth often do not present for assessment until the challenges of a busy course load make their inattention and consequent inefficiency apparent, in high school or even college. Certainly, when a teenager presents complaining of trouble performing at school, it is critical to rule out an overburdened schedule, anxiety or mood disorder, poor sleep habits or sleep disorder, and substance use disorders, all of which are more common in adolescence. But inattentive-type ADHD that was previously missed is also a possibility worth investigating.

Myth 2: “Most children outgrow ADHD; it’s best to find natural solutions and wait it out.”

Early epidemiological studies suggested that as many as 30% of ADHD cases remitted by adulthood, but more recent data has adjusted that number down substantially, closer to 9%. Interestingly, it appears that 10% of patients will experience sustained symptoms, 9% will experience recovery (sustained remission without treatment), and a large majority will have a remitting and relapsing course into adulthood.1

This emerging evidence suggests that ADHD is almost always a lifelong condition. Untreated, it can threaten healthy development (including social skills and self-esteem) and day-to-day function (academic, social and athletic performance and even vulnerability to accidents) in ways that can be profound. The MTA Study has powerfully demonstrated the efficacy of pharmacological treatment and of specific behavioral treatments for ADHD and associated problems.

Myth 3: “You should exhaust natural cures first before trying medications.”

There has been a large amount of research into a variety of “natural” treatments for ADHD: special diets, supplements, increased exercise, and interventions like neurofeedback. While high-dose omega 3 fatty acid supplementation has demonstrated mild improvement in ADHD symptoms, no “natural” treatment has come close to the efficacy of stimulant medications. Interventions such as neurofeedback are expensive and time-consuming without any demonstrated efficacy. That said, improving a child’s routines around sleep, nutrition, and regular exercise are broadly useful strategies to improve any child’s (or adult’s) energy, impulse control, attention, motivation, and capacity to manage adversity and stress. Start any treatment by addressing sleep and exercise, including moderating time spent on screens, to support healthy function. But only medication will achieve symptom remission if your patient has underlying ADHD.

Myth 4: “All medications are equally effective in ADHD.”

It is well-established that stimulants are more effective than non-stimulants in the treatment of ADHD symptoms, with an effect size that is almost double that of non-stimulants.2

Amphetamine-based medications are slightly more effective than methylphenidate-based medications, but they are also generally less well-tolerated. Individual patients commonly have a better response to one class than the other, but you will need a trial to determine which one. It is reasonable to start a patient with an extended formulation of one class, based on your assessment of their vulnerability to side effects or a family history of medication response. Non-stimulants are of use when stimulants are not tolerated (ie, use of atomoxetine with patients who have comorbid anxiety), or to target specific symptoms, such as guanfacine or clonidine for hyperactivity.

Myth 5: “You can’t treat ADHD in substance abusing teens, stimulant medications are addictive.”

ADHD itself (not medications) increases the risk for addiction; those with ADHD are almost twice as likely to develop a substance use disorder, with highest risk for marijuana, alcohol, and nicotine abuse.3

This may be a function of limited impulse control or increased sensitivity in the ADHD brain to a drug’s addictive potential. Importantly, there is growing evidence that youth whose ADHD is treated pharmacologically are at lower risk for addiction than their peers with untreated ADHD.4

Those youth who have both ADHD and addiction are more likely to stay engaged in treatment for addiction when their ADHD is effectively treated, and there are medication formulations (lisdexamfetamine) that are safe in addiction (cannot be absorbed nasally or intravenously). It is important for you to talk about the heightened vulnerability to addiction with your ADHD patients and their parents, and the value of effective treatment in preventing this complication.

Myth 6: “ADHD is usually behavioral. Help parents to set rules, expectations, and limits instead of medicating the problem.”

Bad parenting does not cause ADHD. ADHD is marked by difficulties with impulse control, hyperactivity, and sustaining attention with matters that are not intrinsically engaging. “Behavioral issues” are patterns of behavior children learn to seek rewards or avoid negative consequences. Youth with ADHD can develop behavioral problems, but these are usually driven by negative feedback about their activity level, forgetfulness, or impulse control, which they are not able to change. This can lead to frustration and irritability, poor self-esteem, and even hopelessness — in parents and children both!

While parents are not the source of ADHD symptoms, there is a great deal of parent education and support that can be powerfully effective for these families. Parents benefit from learning strategies that can help their children to shift their attention, plan ahead, and manage frustration, especially for times when their children are unmedicated (vacations and bedtime). It is worth noting that ADHD is among the most heritable of youth psychiatric illnesses, so it is not uncommon for a parent of a child with ADHD to have similar symptoms. If the parents’ ADHD is untreated, they may be more impulsive themselves. They may also be extra sensitive to the qualities they dislike in themselves, inadvertently adding to their children’s sense of shame. ADHD is very treatable, and those with it can learn executive function skills and organizational strategies that can equip them to manage residual symptoms. Parents will benefit from strategies to understand their children and to help them learn adaptive skills in a realistic way. Your discussions with parents could help the families in your practice make adjustments that can translate into big differences in their child’s healthiest development.

Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Sibley MH et al. MTA Cooperative Group. Variable Patterns of Remission From ADHD in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022 Feb;179(2):142-151. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032.

2. Cortese S et al. Comparative Efficacy and Tolerability of Medications for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;5(9):727-738. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4.

3. Lee SS et al. Prospective Association of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Substance Use and Abuse/Dependence: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011 Apr;31(3):328-41. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006.

4. Chorniy A, Kitashima L. Sex, Drugs, and ADHD: The Effects of ADHD Pharmacological Treatment on Teens’ Risky Behaviors. Labour Economics. 2016;43:87-105. doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.06.014.

Early Patching Benefits Kids Born With Cataract in One Eye

TOPLINE:

particularly in the morning or at regular times every day.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study to examine the association between the reported consistency in patching during the first year after unilateral cataract surgery and visual acuity.

- They included data from 101 children whose caregivers completed 7-day patching diaries at 2 months after surgery or at age 13 months.

- The treatment protocol required caregivers to have their child wear a patch over the fellow eye for 1 hour daily from the second week after cataract surgery until age 8 months, followed by patching for 50% of waking hours until age 5 years.

- Consistent patching was defined as daily patching with an average start time before 9 AM or an interquartile range of the first application time of 60 minutes or less.

- Visual acuity in the treated eye was the primary outcome, assessed at ages 54 + 1 months and 10.5 years; participants with a visual acuity of 20/40 or better were said to have near-normal vision.

TAKEAWAY:

- Children whose caregivers reported consistent patching patterns demonstrated better average visual acuity at age 54 months than those whose caregivers reported inconsistent patching patterns (mean difference in logMAR visual acuity, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.22-0.87); the results were promising for children aged 10.5 years, as well.

- Data from the diary completed at age 13 months showed children whose caregivers reported patching before 9 AM or around the same time daily were more likely to achieve near-normal vision at age 54 + 1 months and 10.5 years (relative risk, 3.55; 95% CI, 1.61-7.80, and 2.31; 95% CI, 1.12-4.78, respectively) than those whose caregivers did not report such behavior.

- Children whose caregivers reported consistent vs inconsistent patching patterns achieved more average daily hours of patching both during the first year (4.82 h vs 3.50 h) and between ages 12 and 48 months (4.96 h vs 3.03 h).

IN PRACTICE:

“This information can be used by healthcare providers to motivate caregivers to develop consistent patching habits. Further, providers can present caregivers with simple advice: Apply the patch every day either first thing in the morning or about the same time every day,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carolyn Drews-Botsch, PhD, MPH, of the Department of Global and Community Health at George Mason University, in Fairfax, Virginia. It was published online in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The diaries covered only 14 days of the first year following surgery, which may not have fully represented patching patterns during other periods. The researchers noted that establishing a routine for patching was particularly challenging for infants aged less than 5 months at the time of the first diary completion as these infants may not yet have established regular sleep and feeding routines. Parents who participated in this trial may have differed from those in routine practice, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings to general clinical populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the following grants: 1 R21 EY032152, 2 UG1 EY031287, 5 U10 EY013287, 5 UG1 EY02553, and 7 UG1 EY013272. The authors declared having no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

particularly in the morning or at regular times every day.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study to examine the association between the reported consistency in patching during the first year after unilateral cataract surgery and visual acuity.

- They included data from 101 children whose caregivers completed 7-day patching diaries at 2 months after surgery or at age 13 months.

- The treatment protocol required caregivers to have their child wear a patch over the fellow eye for 1 hour daily from the second week after cataract surgery until age 8 months, followed by patching for 50% of waking hours until age 5 years.

- Consistent patching was defined as daily patching with an average start time before 9 AM or an interquartile range of the first application time of 60 minutes or less.

- Visual acuity in the treated eye was the primary outcome, assessed at ages 54 + 1 months and 10.5 years; participants with a visual acuity of 20/40 or better were said to have near-normal vision.

TAKEAWAY:

- Children whose caregivers reported consistent patching patterns demonstrated better average visual acuity at age 54 months than those whose caregivers reported inconsistent patching patterns (mean difference in logMAR visual acuity, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.22-0.87); the results were promising for children aged 10.5 years, as well.

- Data from the diary completed at age 13 months showed children whose caregivers reported patching before 9 AM or around the same time daily were more likely to achieve near-normal vision at age 54 + 1 months and 10.5 years (relative risk, 3.55; 95% CI, 1.61-7.80, and 2.31; 95% CI, 1.12-4.78, respectively) than those whose caregivers did not report such behavior.

- Children whose caregivers reported consistent vs inconsistent patching patterns achieved more average daily hours of patching both during the first year (4.82 h vs 3.50 h) and between ages 12 and 48 months (4.96 h vs 3.03 h).

IN PRACTICE:

“This information can be used by healthcare providers to motivate caregivers to develop consistent patching habits. Further, providers can present caregivers with simple advice: Apply the patch every day either first thing in the morning or about the same time every day,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carolyn Drews-Botsch, PhD, MPH, of the Department of Global and Community Health at George Mason University, in Fairfax, Virginia. It was published online in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The diaries covered only 14 days of the first year following surgery, which may not have fully represented patching patterns during other periods. The researchers noted that establishing a routine for patching was particularly challenging for infants aged less than 5 months at the time of the first diary completion as these infants may not yet have established regular sleep and feeding routines. Parents who participated in this trial may have differed from those in routine practice, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings to general clinical populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the following grants: 1 R21 EY032152, 2 UG1 EY031287, 5 U10 EY013287, 5 UG1 EY02553, and 7 UG1 EY013272. The authors declared having no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

particularly in the morning or at regular times every day.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a post hoc analysis of the Infant Aphakia Treatment Study to examine the association between the reported consistency in patching during the first year after unilateral cataract surgery and visual acuity.

- They included data from 101 children whose caregivers completed 7-day patching diaries at 2 months after surgery or at age 13 months.

- The treatment protocol required caregivers to have their child wear a patch over the fellow eye for 1 hour daily from the second week after cataract surgery until age 8 months, followed by patching for 50% of waking hours until age 5 years.

- Consistent patching was defined as daily patching with an average start time before 9 AM or an interquartile range of the first application time of 60 minutes or less.

- Visual acuity in the treated eye was the primary outcome, assessed at ages 54 + 1 months and 10.5 years; participants with a visual acuity of 20/40 or better were said to have near-normal vision.

TAKEAWAY:

- Children whose caregivers reported consistent patching patterns demonstrated better average visual acuity at age 54 months than those whose caregivers reported inconsistent patching patterns (mean difference in logMAR visual acuity, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.22-0.87); the results were promising for children aged 10.5 years, as well.

- Data from the diary completed at age 13 months showed children whose caregivers reported patching before 9 AM or around the same time daily were more likely to achieve near-normal vision at age 54 + 1 months and 10.5 years (relative risk, 3.55; 95% CI, 1.61-7.80, and 2.31; 95% CI, 1.12-4.78, respectively) than those whose caregivers did not report such behavior.

- Children whose caregivers reported consistent vs inconsistent patching patterns achieved more average daily hours of patching both during the first year (4.82 h vs 3.50 h) and between ages 12 and 48 months (4.96 h vs 3.03 h).

IN PRACTICE:

“This information can be used by healthcare providers to motivate caregivers to develop consistent patching habits. Further, providers can present caregivers with simple advice: Apply the patch every day either first thing in the morning or about the same time every day,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carolyn Drews-Botsch, PhD, MPH, of the Department of Global and Community Health at George Mason University, in Fairfax, Virginia. It was published online in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The diaries covered only 14 days of the first year following surgery, which may not have fully represented patching patterns during other periods. The researchers noted that establishing a routine for patching was particularly challenging for infants aged less than 5 months at the time of the first diary completion as these infants may not yet have established regular sleep and feeding routines. Parents who participated in this trial may have differed from those in routine practice, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings to general clinical populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the following grants: 1 R21 EY032152, 2 UG1 EY031287, 5 U10 EY013287, 5 UG1 EY02553, and 7 UG1 EY013272. The authors declared having no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis Diagnosis

It’s wintertime, peak season for GAS pharyngitis, and you’d think that this far into the 21st century we would have a foolproof process for diagnosing which among the many patients with pharyngitis have true GAS pharyngitis. Thinking back to the 1980s, we have come a long way from simple throat cultures for detecting GAS, e.g., numerous point of care (POC) Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), waved rapid antigen detection tests (RADT), and numerous highly sensitive molecular assays, e.g. nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). But if you think the issues surrounding management of GAS pharyngitis have been solved by these newer tests, think again.

Several good reviews1-3 are excellent resources for those wishing a refresher on GAS diagnosis/management issues. They present nitty gritty details on comparative advantages/disadvantages of the many testing options while reminding us of the nuts and bolts of GAS pharyngitis. The following are a few nuggets from these articles.

Properly collected throat specimen. A quality throat specimen involves swabbing both tonsillar pillars plus posterior pharynx without touching tongue or inner cheeks. Two swab collections increase sensitivity by almost 10% compared with a single swab. Transport media is preferred if samples will not be cultured within 24 hours. Caveat: RADT testing of a transport media-diluted sample lowers sensitivity compared with direct swab use.

Reliable GAS detection. Commercially available tests in 2025 are well studied. Culture is considered a gold standard for detecting clinically relevant GAS by CDC.4 Culture has good sensitivity (estimated 80%-90% varying among studies and by quality of specimens) and 99% specificity but requires 16-24 hours for results. RADT solves the time-delay issues and has near 100% specificity but sensitivity used to be as low as 65%, hence the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommendation for backup throat culture for negative tests.5 However, current RADT have sensitivities in the 85%-90% range.3,4 So a positive RADT reliably and quickly indicates GAS antigens are present. NAAT have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity, near 100% for each, and a positive reliably indicates GAS nucleic acids are present.

So why not simply always use NAAT? First, it’s a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. NAAT can, and do, detect dead remnants and colonizing GAS way more than culture.2,3 So NAAT are overly sensitive, adding an extra layer of interpretation difficulty, ie, as many as 20% of positive NAAT detections may be carriers or dead GAS. Second, NAAT often requires special instrumentation and kits are more expensive. That said, reimbursement is often higher for NAAT.

Choice based on accuracy in detecting GAS. If time delays were not a problem, culture would still seem the answer. If more rapid detection is needed, either RADT with culture back up or NAAT could be the answer. That said, consider that in the real world, throat cultures are less sensitive and RADT are less specific than indicated by some published data.6 So, the ideal answer, it seems, would be NAAT GAS detection coupled with a confirmatory biomarker of GAS infection. Such innate immune biomarkers may be on the horizon.3

But first, pretest screening. In 2025 what do we do with a positive result? Do we prescribe antibiotics? Do we think the detected GAS bacteria/antigens/nucleic acids represent the cause of the pharyngitis? Or did we just detect dead GAS or even a carrier, while a virus is the true cause? Challenges for this decision include most pharyngitis (up to 70%) being due to viruses, not GAS, plus up to 20% of GAS detections even by less sensitive culture or RADT can be carriers, plus an added 10%-20% of RADT and NAAT detections are dead GAS. Thus, with indiscriminate testing of all pharyngitis patients, the number of truly positive GAS detections that are actually “false positives” (GAS in some form is present but not causing pharyngitis) may be almost as high as for those representing true GAS pharyngitis.

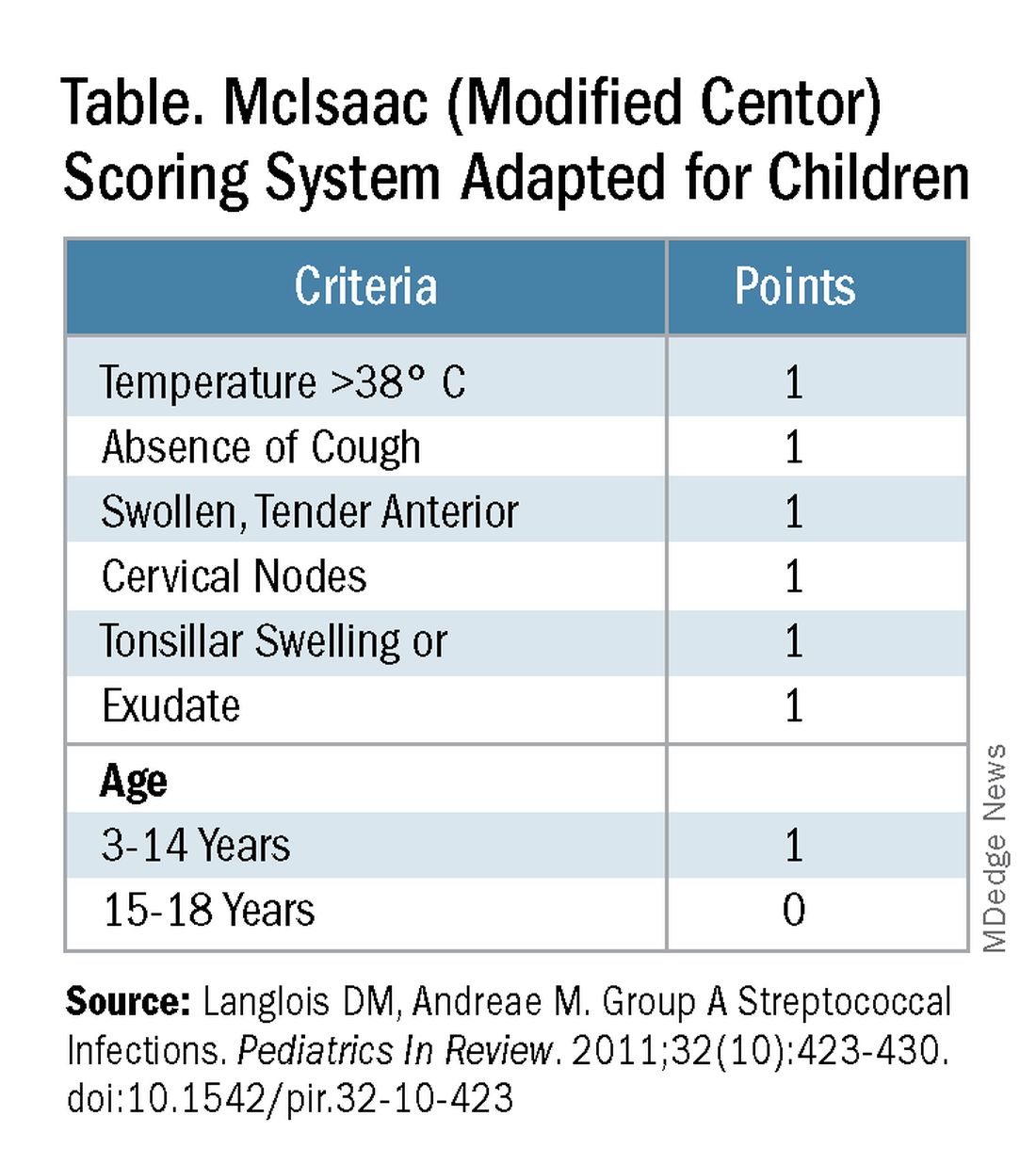

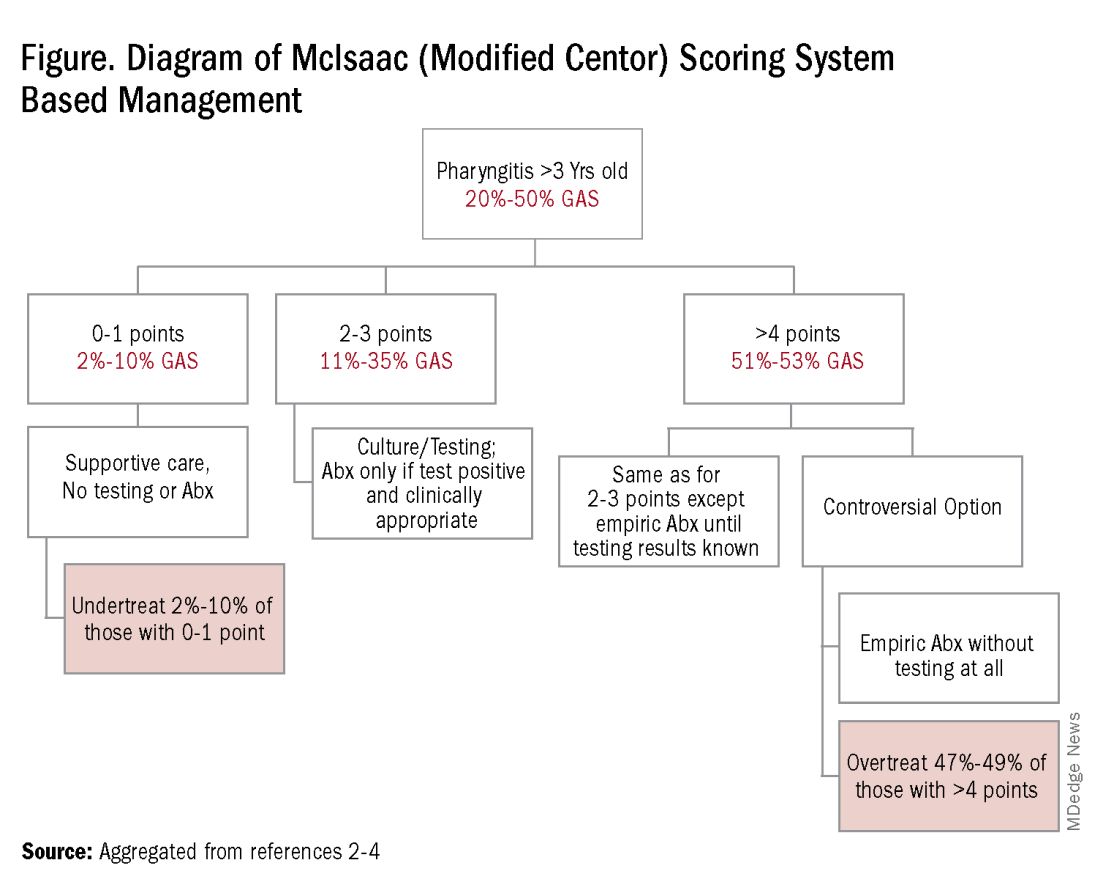

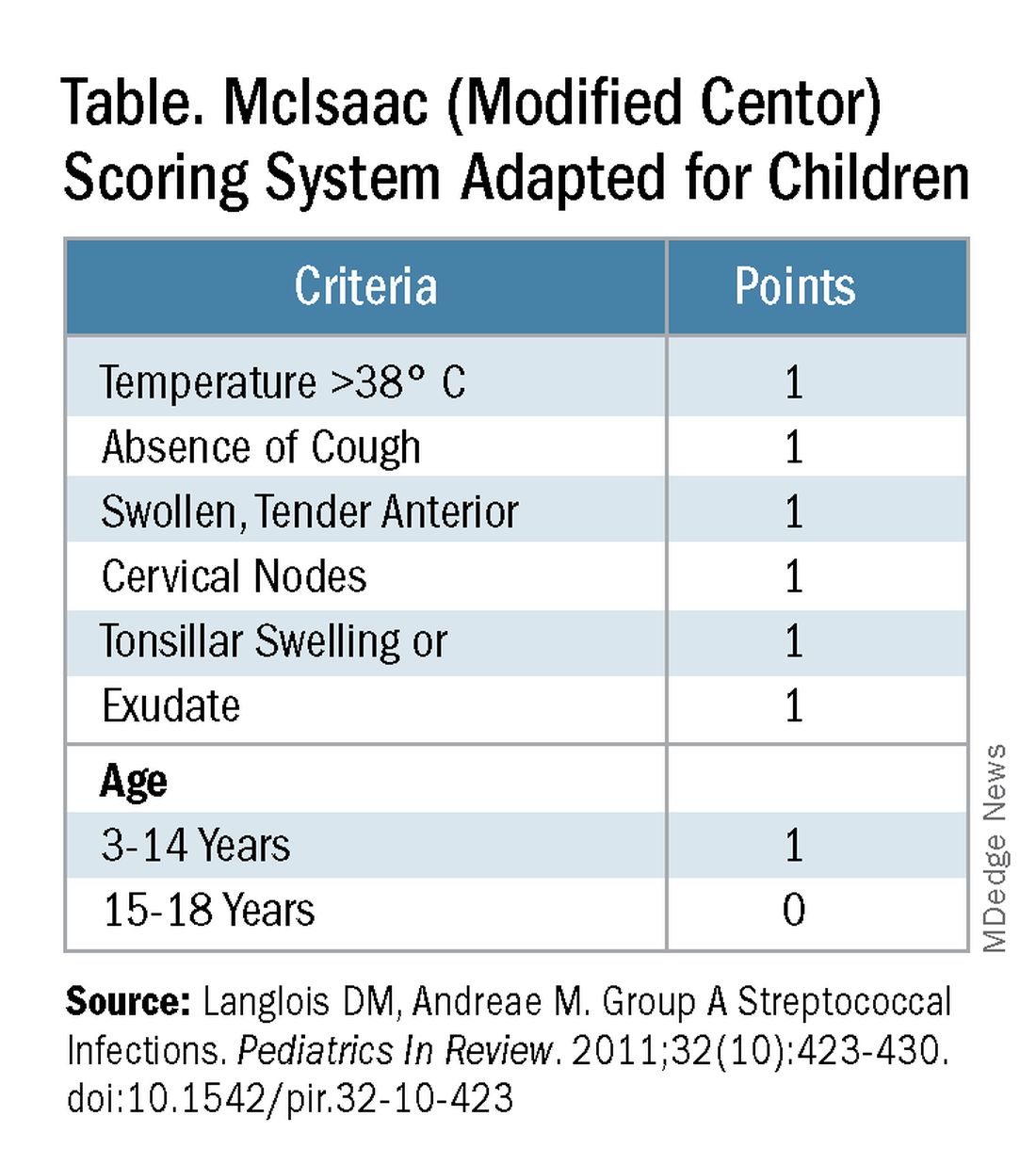

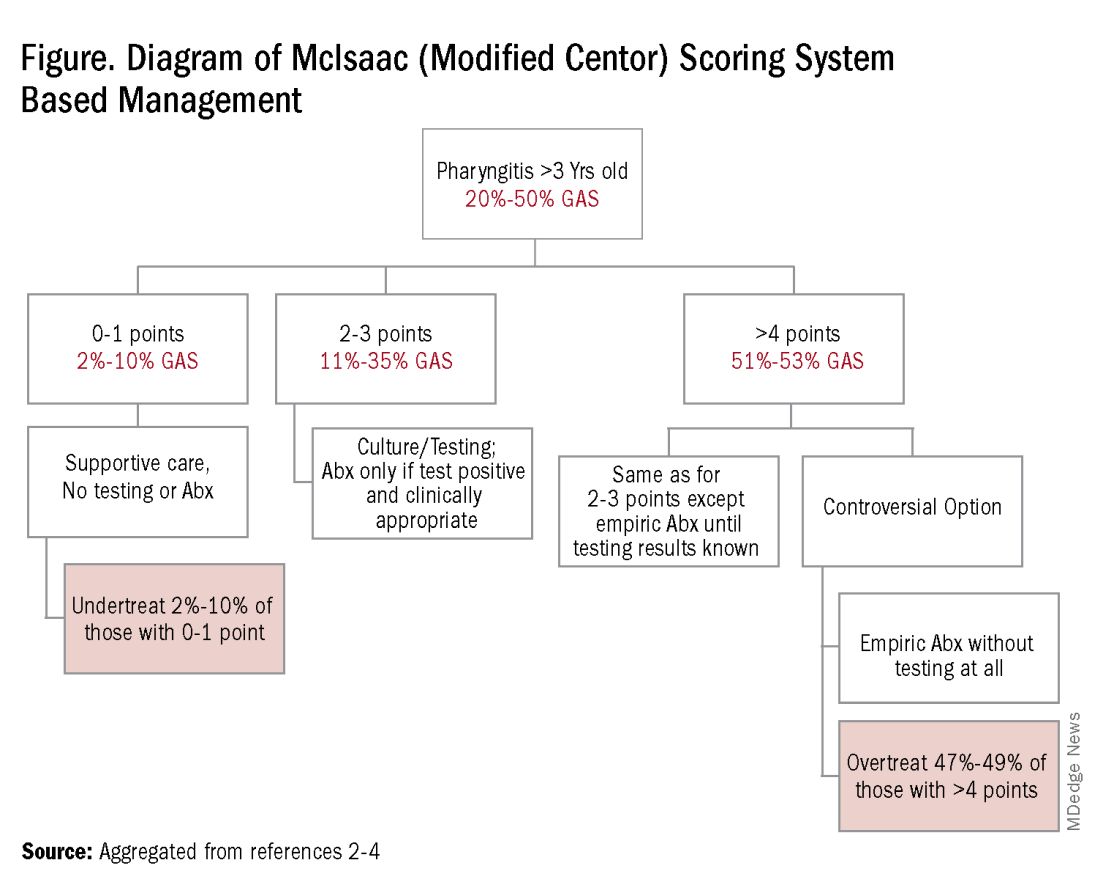

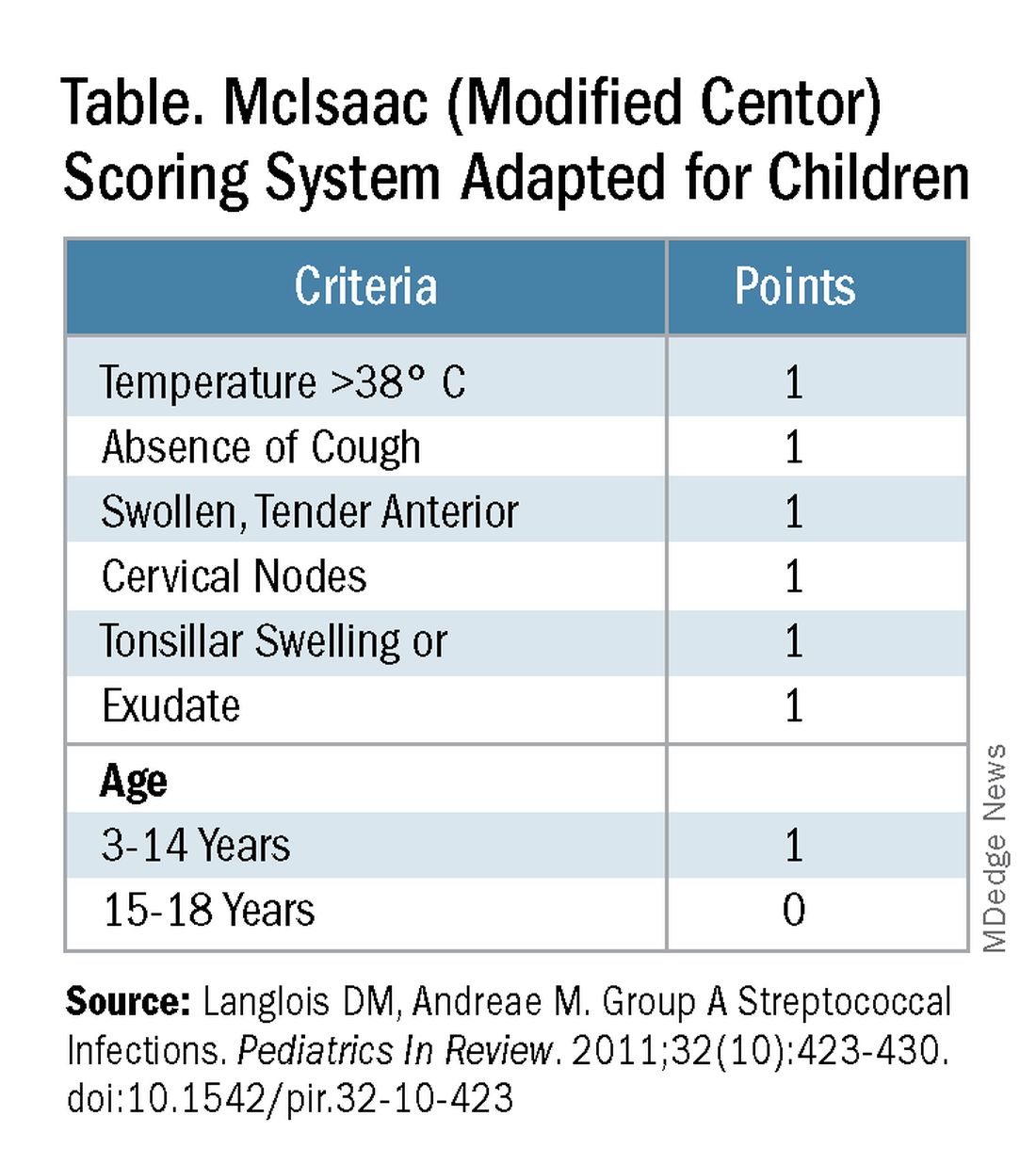

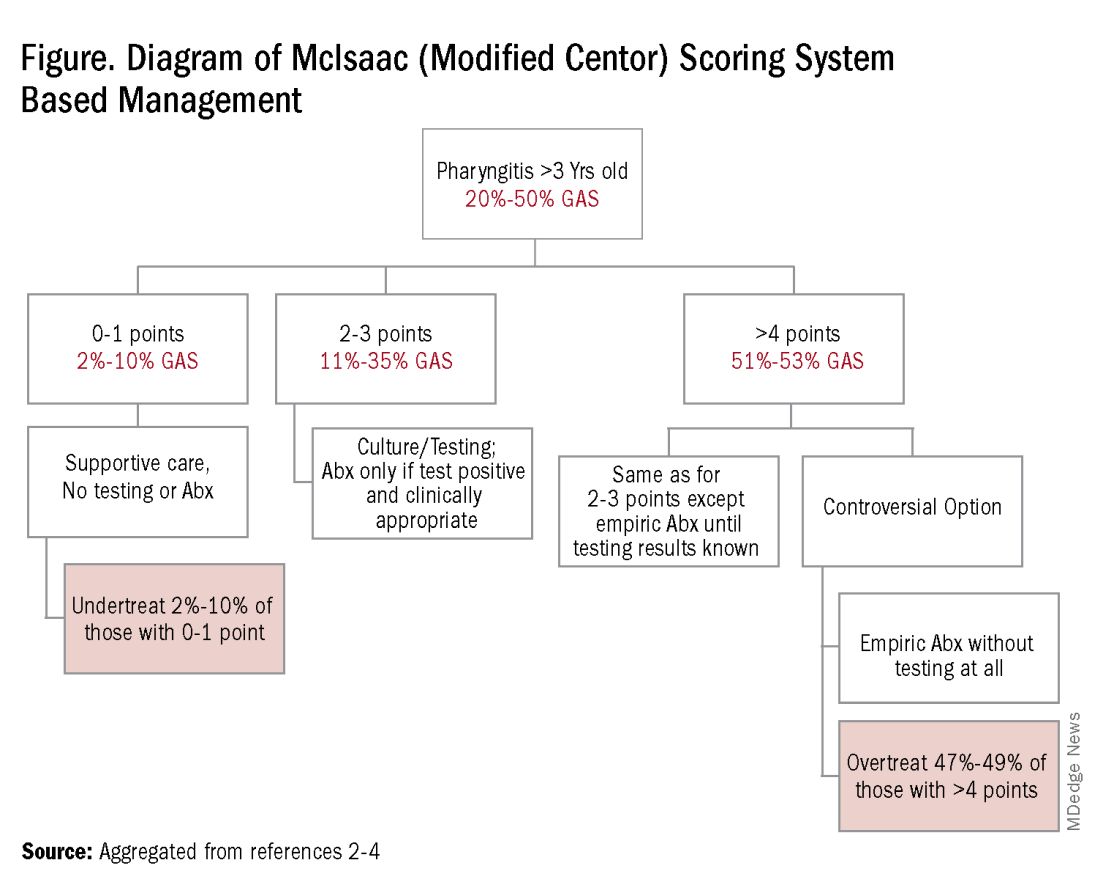

Some tool is needed to minimize testing patients who are likely to have viral pharyngitis to reduce test-positive/GAS-pharyngitis-negative scenarios. Pretest patient screening therefore is critical to increase the positive predictive value of positive GAS testing results. The history and physical can be helpful. In the simplest form of pretest screening, eliminate those younger than 3 years old* or those with viral type sign/symptoms, eg conjunctivitis, cough, coryza.7 This could cut “false” positives by as much as a half. More complete validated scoring systems are also available but remain imperfect. The most published is the McIsaac score (modified Centor score).3-5,8 (See Table and Figure.)

However, even with this validated scoring system, misdiagnoses and some antibiotic misuse will likely occur, particularly if the controversial option to treat a patient with a score above 4 without testing is used. For example, a 2004 study in patients older than 3 years old revealed that 45% with a score above 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis. (McIsaac et al.) A 2012 study showed similar potential overdiagnosis from using the score without testing (45% with > 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis). Of note, clinical scores of below 2 comprised up to 10% and would be neither tested nor treated. (Figure.)

Best clinical judgment. Regardless of the chosen test, we still need to interpret positive results, ie, use best clinical judgment. We know that even with pretest screening some positives tests will represent carriers or nonviable GAS. Yet true GAS pharyngitis needs antibiotic treatment to minimize nonpyogenic and pyogenic complications, plus reduce contagion/transmission risk and days of illness. Thus, we are forced to use best clinical judgment when considering if what could be GAS pharyngitis, particularly exudative pharyngitis, could actually be due to EBV, adenovirus, or gonococcus, each of which can mimic GAS findings. Differentiating these requires discussion beyond the scope of this article, but clues are often found in the history, the patient’s age, associated symptoms and distribution of tonsillopharyngeal exudate. Likewise Group C and G streptococcal pharyngitis can mimic GAS. Note: A comprehensive throat culture can identify these streptococci but requires a special order and likely a call to the laboratory.

Summary: The age-old problem persists, ie, differentiating the minority (~30%) of pharyngitis cases needing antibiotics from the majority that do not. We all wish to promptly treat true GAS pharyngitis; however our current tools remain imperfect. That said, we should strive to correctly diagnose/manage as many patients with pharyngitis as possible. I, for one, can’t wait until we get a validated biomarker that confirms GAS as the culprit in pharyngitis episodes. In the meantime, most providers likely have clinic or hospital approved pathways for managing GAS pharyngitis, many of which are at least in part based on data from sources for this discussion. If not, a firm foundation for creating one can be found in sources among the reference list below. Finally, if you think such pathways somehow interfere with patient flow, consider that a busy multi-provider private practice successfully integrated pretest screening and a pathway while maintaining patient flow and improving antibiotic stewardship.7

*Focal pharyngotonsillar GAS infection is rare in children younger than 3 years old, when GAS nasal passage infection may manifest as streptococcosis.9

Dr Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bannerjee D, Selvarangan RS. The Evolution of Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis Testing. Association for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine, 2018, Sep 1.

2. Cohen JF et al. Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis in Children: New Perspectives on Rapid Diagnostic Testing and Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2024 Apr 24;13(4):250-256. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piae0223.

3. Boyanton Jr BL et al. Current Laboratory and Point-of-Care Pharyngitis Diagnostic Testing and Knowledge Gaps. J Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 23;230(Suppl 3):S182–S189. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiae415.

4. Group A Strep Infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024, Mar 1.