User login

Lesbian, gay, bisexual youth miss out on health care

Youth identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual were significantly less likely than were their peers to communicate with a physician or utilize health care in the past 12 months, according to data from a cohort study of approximately 4,000 adolescents.

Disparities in physical and mental health outcomes for individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) persist in the United States, and emerge in adolescents and young adults, wrote Sari L. Reisner, ScD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and colleagues.

“LGB adult research indicates substantial unmet medical needs, including needed care and preventive care,” for reasons including “reluctance to disclose sexual identity to clinicians, lower health insurance rates, lack of culturally appropriate preventive services, and lack of clinician LGB care competence,” they said.

However, health use trends by adolescents who identify as LGB have not been well studied, they noted.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers analyzed data from 4,256 participants in the third wave (10th grade) of adolescents in Healthy Passages, a longitudinal, observational cohort study of diverse public school students in Birmingham, Ala.; Houston; and Los Angeles County. Data were collected in grades 5, 7, and 10.

The study population included 640 youth who identified as LGB, and 3,616 non-LGB youth. Sexual status was based on responses to questions in the grade 10 youth survey. Health care use was based on the responses to questions about routine care, such as a regular checkup, and other care, such as a sick visit. Data on delayed care were collected from parents and youth. At baseline, the average age of the study participants in fifth grade was 11 years, 48.9% were female, 44.5% were Hispanic or Latino, and 28.9% were Black.

Overall, more LGB youth reported not receiving needed medical care when they thought they needed it within the past 12 months compared with non-LGB youth (42.4% of LGB vs. 30.2% of non-LGB youth; adjusted odds ratio 1.68). The most common conditions for which LGB youth did not seek care were sexually transmitted infections, contraception, and substance use.

Overall, the main reason given for not seeking medical care was that they thought the problem would go away (approximately 26% for LGB and non-LGB). Approximately twice as many LGB youth as non-LGB youth said they avoided medical care because they did not want their parents to know (14.5% vs. 9.4%).

Significantly more LGB youth than non-LGB youth reported difficulty communicating with their physicians in the past 12 months (15.3% vs. 9.4%; aOR 1.71). The main reasons for not communicating with a clinician about a topic of concern were that the adolescent did not want parents to know (40.7% of LGB and 30.2% of non-LGB) and that they were too embarrassed to talk about the topic (37.5% of LGB and 25.9% of non-LGB).

The researchers were not surprised that “LGB youth self-reported greater difficulty communicating with a clinician about topics they wanted to discuss,” but they found no significant differences in reasons for communication difficulty based on sexual orientation.

Approximately two-thirds (65.8%) of LGB youth reported feeling “a little or not at all comfortable” talking to a health care clinician about their sexual attractions, compared with approximately one-third (37.8%) of non-LGB youth.

Only 12.5% of the LGB youth said that their clinicians knew their sexual orientation, the researchers noted. However, clinicians need to know youths’ sexual orientation to provide appropriate and comprehensive care, they said, especially in light of the known negative health consequences of LGB internalized stigma, as well as the pertinence of certain sexual behaviors to preventive care and screening.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and inability to show causality, and by the incongruence of different dimensions of sexual orientation, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use only of English and Spanish language, and a lack of complete information on disclosure of sexual orientation to parents, the researchers noted.

The results were strengthened by the diverse demographics, although they may not be generalizable to a wider population, they added.

However, the data show that responsive health care is needed to reduce disparities for LGB youth, they emphasized. “Care should be sensitive and respectful to sexual orientation for all youth, with clinicians taking time to ask adolescents about their sexual identity, attractions, and behaviors, particularly in sexual and reproductive health,” they concluded.

Adolescents suffer barriers similar to those of adults

“We know that significant health disparities exist for LGBTQ adults and adolescents,” Kelly Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, said in an interview. “LGBTQ adults often have had poor experiences during health care encounters – ranging from poor interactions with inadequately trained clinicians to frank discrimination,” she said. “These experiences can prevent individuals from seeking health care in the future or disclosing important information during a medical visit, both of which can contribute to worsened health outcomes,” she emphasized.

Prior to this study, data to confirm similar patterns of decreased health care utilization in LGB youth were limited, Dr. Curran said. “Identifying and understanding barriers to health care for LGBTQ youth are essential to help address the disparities in this population,” she said.

Dr. Curran said she was not surprised by the study findings for adolescents, which reflect patterns seen in LGBTQ adults.

Overcoming barriers to encourage LGB youth to seek regular medical care involves “training health care professionals about LGBTQ health, teaching the skill of taking a nonjudgmental, inclusive history, and making health care facilities welcoming and inclusive, such as displaying a pride flag in clinic, and using forms asking for pronouns,” Dr. Curran said.

Dr. Curran said she thinks the trends in decreased health care use are similar for transgender youth. “I suspect, if anything, that transgender youth will have even further decreased health care utilization when compared to cisgender heterosexual peers and LGB peers,” she noted.

Going forward, it will be important to understand the reasons behind decreased health care use among LGB youth, such as poor experiences, discrimination, or fears about confidentiality, said Dr. Curran. “Additionally, it would be important to understand if this decreased health utilization also occurs with transgender youth,” she said.

The Healthy Passages Study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One of the study coauthors disclosed funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Harvard-wide Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship Program. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Youth identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual were significantly less likely than were their peers to communicate with a physician or utilize health care in the past 12 months, according to data from a cohort study of approximately 4,000 adolescents.

Disparities in physical and mental health outcomes for individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) persist in the United States, and emerge in adolescents and young adults, wrote Sari L. Reisner, ScD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and colleagues.

“LGB adult research indicates substantial unmet medical needs, including needed care and preventive care,” for reasons including “reluctance to disclose sexual identity to clinicians, lower health insurance rates, lack of culturally appropriate preventive services, and lack of clinician LGB care competence,” they said.

However, health use trends by adolescents who identify as LGB have not been well studied, they noted.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers analyzed data from 4,256 participants in the third wave (10th grade) of adolescents in Healthy Passages, a longitudinal, observational cohort study of diverse public school students in Birmingham, Ala.; Houston; and Los Angeles County. Data were collected in grades 5, 7, and 10.

The study population included 640 youth who identified as LGB, and 3,616 non-LGB youth. Sexual status was based on responses to questions in the grade 10 youth survey. Health care use was based on the responses to questions about routine care, such as a regular checkup, and other care, such as a sick visit. Data on delayed care were collected from parents and youth. At baseline, the average age of the study participants in fifth grade was 11 years, 48.9% were female, 44.5% were Hispanic or Latino, and 28.9% were Black.

Overall, more LGB youth reported not receiving needed medical care when they thought they needed it within the past 12 months compared with non-LGB youth (42.4% of LGB vs. 30.2% of non-LGB youth; adjusted odds ratio 1.68). The most common conditions for which LGB youth did not seek care were sexually transmitted infections, contraception, and substance use.

Overall, the main reason given for not seeking medical care was that they thought the problem would go away (approximately 26% for LGB and non-LGB). Approximately twice as many LGB youth as non-LGB youth said they avoided medical care because they did not want their parents to know (14.5% vs. 9.4%).

Significantly more LGB youth than non-LGB youth reported difficulty communicating with their physicians in the past 12 months (15.3% vs. 9.4%; aOR 1.71). The main reasons for not communicating with a clinician about a topic of concern were that the adolescent did not want parents to know (40.7% of LGB and 30.2% of non-LGB) and that they were too embarrassed to talk about the topic (37.5% of LGB and 25.9% of non-LGB).

The researchers were not surprised that “LGB youth self-reported greater difficulty communicating with a clinician about topics they wanted to discuss,” but they found no significant differences in reasons for communication difficulty based on sexual orientation.

Approximately two-thirds (65.8%) of LGB youth reported feeling “a little or not at all comfortable” talking to a health care clinician about their sexual attractions, compared with approximately one-third (37.8%) of non-LGB youth.

Only 12.5% of the LGB youth said that their clinicians knew their sexual orientation, the researchers noted. However, clinicians need to know youths’ sexual orientation to provide appropriate and comprehensive care, they said, especially in light of the known negative health consequences of LGB internalized stigma, as well as the pertinence of certain sexual behaviors to preventive care and screening.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and inability to show causality, and by the incongruence of different dimensions of sexual orientation, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use only of English and Spanish language, and a lack of complete information on disclosure of sexual orientation to parents, the researchers noted.

The results were strengthened by the diverse demographics, although they may not be generalizable to a wider population, they added.

However, the data show that responsive health care is needed to reduce disparities for LGB youth, they emphasized. “Care should be sensitive and respectful to sexual orientation for all youth, with clinicians taking time to ask adolescents about their sexual identity, attractions, and behaviors, particularly in sexual and reproductive health,” they concluded.

Adolescents suffer barriers similar to those of adults

“We know that significant health disparities exist for LGBTQ adults and adolescents,” Kelly Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, said in an interview. “LGBTQ adults often have had poor experiences during health care encounters – ranging from poor interactions with inadequately trained clinicians to frank discrimination,” she said. “These experiences can prevent individuals from seeking health care in the future or disclosing important information during a medical visit, both of which can contribute to worsened health outcomes,” she emphasized.

Prior to this study, data to confirm similar patterns of decreased health care utilization in LGB youth were limited, Dr. Curran said. “Identifying and understanding barriers to health care for LGBTQ youth are essential to help address the disparities in this population,” she said.

Dr. Curran said she was not surprised by the study findings for adolescents, which reflect patterns seen in LGBTQ adults.

Overcoming barriers to encourage LGB youth to seek regular medical care involves “training health care professionals about LGBTQ health, teaching the skill of taking a nonjudgmental, inclusive history, and making health care facilities welcoming and inclusive, such as displaying a pride flag in clinic, and using forms asking for pronouns,” Dr. Curran said.

Dr. Curran said she thinks the trends in decreased health care use are similar for transgender youth. “I suspect, if anything, that transgender youth will have even further decreased health care utilization when compared to cisgender heterosexual peers and LGB peers,” she noted.

Going forward, it will be important to understand the reasons behind decreased health care use among LGB youth, such as poor experiences, discrimination, or fears about confidentiality, said Dr. Curran. “Additionally, it would be important to understand if this decreased health utilization also occurs with transgender youth,” she said.

The Healthy Passages Study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One of the study coauthors disclosed funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Harvard-wide Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship Program. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Youth identifying as lesbian, gay, or bisexual were significantly less likely than were their peers to communicate with a physician or utilize health care in the past 12 months, according to data from a cohort study of approximately 4,000 adolescents.

Disparities in physical and mental health outcomes for individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) persist in the United States, and emerge in adolescents and young adults, wrote Sari L. Reisner, ScD, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and colleagues.

“LGB adult research indicates substantial unmet medical needs, including needed care and preventive care,” for reasons including “reluctance to disclose sexual identity to clinicians, lower health insurance rates, lack of culturally appropriate preventive services, and lack of clinician LGB care competence,” they said.

However, health use trends by adolescents who identify as LGB have not been well studied, they noted.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers analyzed data from 4,256 participants in the third wave (10th grade) of adolescents in Healthy Passages, a longitudinal, observational cohort study of diverse public school students in Birmingham, Ala.; Houston; and Los Angeles County. Data were collected in grades 5, 7, and 10.

The study population included 640 youth who identified as LGB, and 3,616 non-LGB youth. Sexual status was based on responses to questions in the grade 10 youth survey. Health care use was based on the responses to questions about routine care, such as a regular checkup, and other care, such as a sick visit. Data on delayed care were collected from parents and youth. At baseline, the average age of the study participants in fifth grade was 11 years, 48.9% were female, 44.5% were Hispanic or Latino, and 28.9% were Black.

Overall, more LGB youth reported not receiving needed medical care when they thought they needed it within the past 12 months compared with non-LGB youth (42.4% of LGB vs. 30.2% of non-LGB youth; adjusted odds ratio 1.68). The most common conditions for which LGB youth did not seek care were sexually transmitted infections, contraception, and substance use.

Overall, the main reason given for not seeking medical care was that they thought the problem would go away (approximately 26% for LGB and non-LGB). Approximately twice as many LGB youth as non-LGB youth said they avoided medical care because they did not want their parents to know (14.5% vs. 9.4%).

Significantly more LGB youth than non-LGB youth reported difficulty communicating with their physicians in the past 12 months (15.3% vs. 9.4%; aOR 1.71). The main reasons for not communicating with a clinician about a topic of concern were that the adolescent did not want parents to know (40.7% of LGB and 30.2% of non-LGB) and that they were too embarrassed to talk about the topic (37.5% of LGB and 25.9% of non-LGB).

The researchers were not surprised that “LGB youth self-reported greater difficulty communicating with a clinician about topics they wanted to discuss,” but they found no significant differences in reasons for communication difficulty based on sexual orientation.

Approximately two-thirds (65.8%) of LGB youth reported feeling “a little or not at all comfortable” talking to a health care clinician about their sexual attractions, compared with approximately one-third (37.8%) of non-LGB youth.

Only 12.5% of the LGB youth said that their clinicians knew their sexual orientation, the researchers noted. However, clinicians need to know youths’ sexual orientation to provide appropriate and comprehensive care, they said, especially in light of the known negative health consequences of LGB internalized stigma, as well as the pertinence of certain sexual behaviors to preventive care and screening.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and inability to show causality, and by the incongruence of different dimensions of sexual orientation, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use only of English and Spanish language, and a lack of complete information on disclosure of sexual orientation to parents, the researchers noted.

The results were strengthened by the diverse demographics, although they may not be generalizable to a wider population, they added.

However, the data show that responsive health care is needed to reduce disparities for LGB youth, they emphasized. “Care should be sensitive and respectful to sexual orientation for all youth, with clinicians taking time to ask adolescents about their sexual identity, attractions, and behaviors, particularly in sexual and reproductive health,” they concluded.

Adolescents suffer barriers similar to those of adults

“We know that significant health disparities exist for LGBTQ adults and adolescents,” Kelly Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, said in an interview. “LGBTQ adults often have had poor experiences during health care encounters – ranging from poor interactions with inadequately trained clinicians to frank discrimination,” she said. “These experiences can prevent individuals from seeking health care in the future or disclosing important information during a medical visit, both of which can contribute to worsened health outcomes,” she emphasized.

Prior to this study, data to confirm similar patterns of decreased health care utilization in LGB youth were limited, Dr. Curran said. “Identifying and understanding barriers to health care for LGBTQ youth are essential to help address the disparities in this population,” she said.

Dr. Curran said she was not surprised by the study findings for adolescents, which reflect patterns seen in LGBTQ adults.

Overcoming barriers to encourage LGB youth to seek regular medical care involves “training health care professionals about LGBTQ health, teaching the skill of taking a nonjudgmental, inclusive history, and making health care facilities welcoming and inclusive, such as displaying a pride flag in clinic, and using forms asking for pronouns,” Dr. Curran said.

Dr. Curran said she thinks the trends in decreased health care use are similar for transgender youth. “I suspect, if anything, that transgender youth will have even further decreased health care utilization when compared to cisgender heterosexual peers and LGB peers,” she noted.

Going forward, it will be important to understand the reasons behind decreased health care use among LGB youth, such as poor experiences, discrimination, or fears about confidentiality, said Dr. Curran. “Additionally, it would be important to understand if this decreased health utilization also occurs with transgender youth,” she said.

The Healthy Passages Study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One of the study coauthors disclosed funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Harvard-wide Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship Program. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

HCV in pregnancy: One piece of a bigger problem

Mirroring the opioid crisis, maternal and newborn hepatitis C infections (HCV) more than doubled in the United States between 2009 and 2019, with disproportionate increases in people of White, American Indian, and Alaska Native race, especially those with less education, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Health Forum. However, the level of risk within these populations was mitigated in counties with higher employment, reported Stephen W. Patrick, MD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., and coauthors.

“As we develop public health approaches to prevent HCV infections, connect to treatment, and monitor exposed infants, understanding these factors can be of critical importance to tailoring interventions,” Dr. Patrick said in an interview. “HCV is one more complication of the opioid crisis,” he added. “These data also enable us to step back a bit from HCV and look at the landscape of how the opioid crisis continues to grow in complexity and scope. Throughout the opioid crisis we have often failed to recognize and address the unique needs of pregnant people and infants.”

The study authors used data from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and from the Area Health Resource File to examine maternal-infant HCV infection among all U.S. births between 2009 and 2019. The researchers also examined community-level risk factors including rurality, employment, and access to medical care.

In counties reporting HCV, there were 39,380,122 people who had live births, of whom 138,343 (0.4%) were diagnosed with HCV. The overall rate of maternal HCV infection increased from 1.8 to 5.1 per 1,000 live births between 2009 and 2019.

Infection rates were highest in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) and White people (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94 and 7.37, respectively) compared with Black people. They were higher among individuals without a 4-year degree compared to those with higher education (aOR, 3.19).

Among these groups considered to be at higher risk for HCV infection, high employment rates somewhat mitigated the risk. Specifically, in counties in the 10th percentile of employment, the predicted probability of HCV increased from 0.16% to 1.37%, between 2009 and 2019, whereas in counties at the 90th percentile of employment, the predicted probability remained similar, at 0.36% in 2009 and 0.48% in 2019.

“With constrained national resources, understanding both individual and community-level factors associated with HCV infections in pregnant people could inform strategies to mitigate its spread, such as harm reduction efforts (e.g., syringe service programs), improving access to treatment for [opioid use disorder] or increasing the obstetrical workforce in high-risk communities, HCV testing strategies in pregnant people and people of childbearing age, and treatment with novel antiviral therapies,” wrote the authors.

In the time since the authors began the study, universal HCV screening for every pregnancy has been recommended by a number of groups, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). However, Dr. Patrick says even though such recommendations are now adopted, it will be some time before they are fully operational, making knowledge of HCV risk factors important for obstetricians as well as pediatricians and family physicians. “We don’t know how if hospitals and clinicians have started universal screening for HCV and even when it is completely adopted, understanding individual and community-level factors associated with HCV in pregnant people is still of critical importance,” he explained. “In some of our previous work we have found that non-White HCV-exposed infants are less likely to be tested for HCV than are White infants, even after accounting for multiple individual and hospital-level factors. The pattern we are seeing in our research and in research in other groups is one of unequal treatment of pregnant people with substance use disorder in terms of being given evidence-based treatments, being tested for HCV, and even in child welfare outcomes like foster placement. It is important to know these issues are occurring, but we need specific equitable approaches to ensuring optimal outcomes for all families.

Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, one of the authors of the SMFM’s new recommendations for universal HCV screening in pregnancy, agreed that until universal screening is widely adopted, awareness of maternal HCV risk factors is important, “to better determine who is at highest risk for hep C, barriers to care, and patients to better target.” This information also affects procedure at the time of delivery, added Dr. Kuller, professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “We do not perform C-sections for the presence of hep C,” he told this publication. However, in labor, “we try to avoid internal fetal monitoring when possible, and early artificial rupture of membranes when possible, and avoid the use of routine episiotomy,” he said. “Hep C–positive patients should also be assessed for other sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and hep B. “Although we do not typically treat hep C pharmacologically during pregnancy, we try to get the patient placed with a hepatologist for long-term management.”

The study has important implications for pediatric patients, added Audrey R. Lloyd, MD, a med-peds infectious disease fellow who is studying HCV in pregnancy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “In the setting of maternal HCV viremia, maternal-fetal transmission occurs in around 6% of exposed infants and around 10% if there is maternal HIV-HCV coinfection,” she said in an interview. “With the increasing rates of HCV in pregnant women described by Dr. Patrick et al., HCV infections among infants will also rise. Even when maternal HCV infection is documented, we often do not do a good job screening the infants for infection and linking them to treatment. This new data makes me worried we may see more complications of pediatric HCV infection in the future,” she added. She explained that safe and effective treatments for HCV infection are approved down to 3 years of age, but patients must first be diagnosed to receive treatment.

From whichever angle you approach it, tackling both the opioid epidemic and HCV infection in pregnancy will inevitably end up helping both parts of the mother-infant dyad, said Dr. Patrick. “Not too long ago I was caring for an opioid-exposed infant at the hospital where I practice who had transferred in from another center hours away. The mother had not been tested for HCV, so I tested the infant for HCV antibodies which were positive. Imagine that, determining a mother is HCV positive by testing the infant. There are so many layers of systems that should be fixed to make this not happen. And what are the chances the mother, after she found out, was able to access treatment for HCV? What about the infant being tested? The systems are just fragmented and we need to do better.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Patrick, Dr. Kuller, nor Dr. Lloyd reported any conflicts of interest.

Mirroring the opioid crisis, maternal and newborn hepatitis C infections (HCV) more than doubled in the United States between 2009 and 2019, with disproportionate increases in people of White, American Indian, and Alaska Native race, especially those with less education, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Health Forum. However, the level of risk within these populations was mitigated in counties with higher employment, reported Stephen W. Patrick, MD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., and coauthors.

“As we develop public health approaches to prevent HCV infections, connect to treatment, and monitor exposed infants, understanding these factors can be of critical importance to tailoring interventions,” Dr. Patrick said in an interview. “HCV is one more complication of the opioid crisis,” he added. “These data also enable us to step back a bit from HCV and look at the landscape of how the opioid crisis continues to grow in complexity and scope. Throughout the opioid crisis we have often failed to recognize and address the unique needs of pregnant people and infants.”

The study authors used data from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and from the Area Health Resource File to examine maternal-infant HCV infection among all U.S. births between 2009 and 2019. The researchers also examined community-level risk factors including rurality, employment, and access to medical care.

In counties reporting HCV, there were 39,380,122 people who had live births, of whom 138,343 (0.4%) were diagnosed with HCV. The overall rate of maternal HCV infection increased from 1.8 to 5.1 per 1,000 live births between 2009 and 2019.

Infection rates were highest in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) and White people (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94 and 7.37, respectively) compared with Black people. They were higher among individuals without a 4-year degree compared to those with higher education (aOR, 3.19).

Among these groups considered to be at higher risk for HCV infection, high employment rates somewhat mitigated the risk. Specifically, in counties in the 10th percentile of employment, the predicted probability of HCV increased from 0.16% to 1.37%, between 2009 and 2019, whereas in counties at the 90th percentile of employment, the predicted probability remained similar, at 0.36% in 2009 and 0.48% in 2019.

“With constrained national resources, understanding both individual and community-level factors associated with HCV infections in pregnant people could inform strategies to mitigate its spread, such as harm reduction efforts (e.g., syringe service programs), improving access to treatment for [opioid use disorder] or increasing the obstetrical workforce in high-risk communities, HCV testing strategies in pregnant people and people of childbearing age, and treatment with novel antiviral therapies,” wrote the authors.

In the time since the authors began the study, universal HCV screening for every pregnancy has been recommended by a number of groups, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). However, Dr. Patrick says even though such recommendations are now adopted, it will be some time before they are fully operational, making knowledge of HCV risk factors important for obstetricians as well as pediatricians and family physicians. “We don’t know how if hospitals and clinicians have started universal screening for HCV and even when it is completely adopted, understanding individual and community-level factors associated with HCV in pregnant people is still of critical importance,” he explained. “In some of our previous work we have found that non-White HCV-exposed infants are less likely to be tested for HCV than are White infants, even after accounting for multiple individual and hospital-level factors. The pattern we are seeing in our research and in research in other groups is one of unequal treatment of pregnant people with substance use disorder in terms of being given evidence-based treatments, being tested for HCV, and even in child welfare outcomes like foster placement. It is important to know these issues are occurring, but we need specific equitable approaches to ensuring optimal outcomes for all families.

Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, one of the authors of the SMFM’s new recommendations for universal HCV screening in pregnancy, agreed that until universal screening is widely adopted, awareness of maternal HCV risk factors is important, “to better determine who is at highest risk for hep C, barriers to care, and patients to better target.” This information also affects procedure at the time of delivery, added Dr. Kuller, professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “We do not perform C-sections for the presence of hep C,” he told this publication. However, in labor, “we try to avoid internal fetal monitoring when possible, and early artificial rupture of membranes when possible, and avoid the use of routine episiotomy,” he said. “Hep C–positive patients should also be assessed for other sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and hep B. “Although we do not typically treat hep C pharmacologically during pregnancy, we try to get the patient placed with a hepatologist for long-term management.”

The study has important implications for pediatric patients, added Audrey R. Lloyd, MD, a med-peds infectious disease fellow who is studying HCV in pregnancy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “In the setting of maternal HCV viremia, maternal-fetal transmission occurs in around 6% of exposed infants and around 10% if there is maternal HIV-HCV coinfection,” she said in an interview. “With the increasing rates of HCV in pregnant women described by Dr. Patrick et al., HCV infections among infants will also rise. Even when maternal HCV infection is documented, we often do not do a good job screening the infants for infection and linking them to treatment. This new data makes me worried we may see more complications of pediatric HCV infection in the future,” she added. She explained that safe and effective treatments for HCV infection are approved down to 3 years of age, but patients must first be diagnosed to receive treatment.

From whichever angle you approach it, tackling both the opioid epidemic and HCV infection in pregnancy will inevitably end up helping both parts of the mother-infant dyad, said Dr. Patrick. “Not too long ago I was caring for an opioid-exposed infant at the hospital where I practice who had transferred in from another center hours away. The mother had not been tested for HCV, so I tested the infant for HCV antibodies which were positive. Imagine that, determining a mother is HCV positive by testing the infant. There are so many layers of systems that should be fixed to make this not happen. And what are the chances the mother, after she found out, was able to access treatment for HCV? What about the infant being tested? The systems are just fragmented and we need to do better.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Patrick, Dr. Kuller, nor Dr. Lloyd reported any conflicts of interest.

Mirroring the opioid crisis, maternal and newborn hepatitis C infections (HCV) more than doubled in the United States between 2009 and 2019, with disproportionate increases in people of White, American Indian, and Alaska Native race, especially those with less education, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Health Forum. However, the level of risk within these populations was mitigated in counties with higher employment, reported Stephen W. Patrick, MD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., and coauthors.

“As we develop public health approaches to prevent HCV infections, connect to treatment, and monitor exposed infants, understanding these factors can be of critical importance to tailoring interventions,” Dr. Patrick said in an interview. “HCV is one more complication of the opioid crisis,” he added. “These data also enable us to step back a bit from HCV and look at the landscape of how the opioid crisis continues to grow in complexity and scope. Throughout the opioid crisis we have often failed to recognize and address the unique needs of pregnant people and infants.”

The study authors used data from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and from the Area Health Resource File to examine maternal-infant HCV infection among all U.S. births between 2009 and 2019. The researchers also examined community-level risk factors including rurality, employment, and access to medical care.

In counties reporting HCV, there were 39,380,122 people who had live births, of whom 138,343 (0.4%) were diagnosed with HCV. The overall rate of maternal HCV infection increased from 1.8 to 5.1 per 1,000 live births between 2009 and 2019.

Infection rates were highest in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) and White people (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94 and 7.37, respectively) compared with Black people. They were higher among individuals without a 4-year degree compared to those with higher education (aOR, 3.19).

Among these groups considered to be at higher risk for HCV infection, high employment rates somewhat mitigated the risk. Specifically, in counties in the 10th percentile of employment, the predicted probability of HCV increased from 0.16% to 1.37%, between 2009 and 2019, whereas in counties at the 90th percentile of employment, the predicted probability remained similar, at 0.36% in 2009 and 0.48% in 2019.

“With constrained national resources, understanding both individual and community-level factors associated with HCV infections in pregnant people could inform strategies to mitigate its spread, such as harm reduction efforts (e.g., syringe service programs), improving access to treatment for [opioid use disorder] or increasing the obstetrical workforce in high-risk communities, HCV testing strategies in pregnant people and people of childbearing age, and treatment with novel antiviral therapies,” wrote the authors.

In the time since the authors began the study, universal HCV screening for every pregnancy has been recommended by a number of groups, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). However, Dr. Patrick says even though such recommendations are now adopted, it will be some time before they are fully operational, making knowledge of HCV risk factors important for obstetricians as well as pediatricians and family physicians. “We don’t know how if hospitals and clinicians have started universal screening for HCV and even when it is completely adopted, understanding individual and community-level factors associated with HCV in pregnant people is still of critical importance,” he explained. “In some of our previous work we have found that non-White HCV-exposed infants are less likely to be tested for HCV than are White infants, even after accounting for multiple individual and hospital-level factors. The pattern we are seeing in our research and in research in other groups is one of unequal treatment of pregnant people with substance use disorder in terms of being given evidence-based treatments, being tested for HCV, and even in child welfare outcomes like foster placement. It is important to know these issues are occurring, but we need specific equitable approaches to ensuring optimal outcomes for all families.

Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, one of the authors of the SMFM’s new recommendations for universal HCV screening in pregnancy, agreed that until universal screening is widely adopted, awareness of maternal HCV risk factors is important, “to better determine who is at highest risk for hep C, barriers to care, and patients to better target.” This information also affects procedure at the time of delivery, added Dr. Kuller, professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “We do not perform C-sections for the presence of hep C,” he told this publication. However, in labor, “we try to avoid internal fetal monitoring when possible, and early artificial rupture of membranes when possible, and avoid the use of routine episiotomy,” he said. “Hep C–positive patients should also be assessed for other sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and hep B. “Although we do not typically treat hep C pharmacologically during pregnancy, we try to get the patient placed with a hepatologist for long-term management.”

The study has important implications for pediatric patients, added Audrey R. Lloyd, MD, a med-peds infectious disease fellow who is studying HCV in pregnancy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “In the setting of maternal HCV viremia, maternal-fetal transmission occurs in around 6% of exposed infants and around 10% if there is maternal HIV-HCV coinfection,” she said in an interview. “With the increasing rates of HCV in pregnant women described by Dr. Patrick et al., HCV infections among infants will also rise. Even when maternal HCV infection is documented, we often do not do a good job screening the infants for infection and linking them to treatment. This new data makes me worried we may see more complications of pediatric HCV infection in the future,” she added. She explained that safe and effective treatments for HCV infection are approved down to 3 years of age, but patients must first be diagnosed to receive treatment.

From whichever angle you approach it, tackling both the opioid epidemic and HCV infection in pregnancy will inevitably end up helping both parts of the mother-infant dyad, said Dr. Patrick. “Not too long ago I was caring for an opioid-exposed infant at the hospital where I practice who had transferred in from another center hours away. The mother had not been tested for HCV, so I tested the infant for HCV antibodies which were positive. Imagine that, determining a mother is HCV positive by testing the infant. There are so many layers of systems that should be fixed to make this not happen. And what are the chances the mother, after she found out, was able to access treatment for HCV? What about the infant being tested? The systems are just fragmented and we need to do better.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Patrick, Dr. Kuller, nor Dr. Lloyd reported any conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA HEALTH FORUM

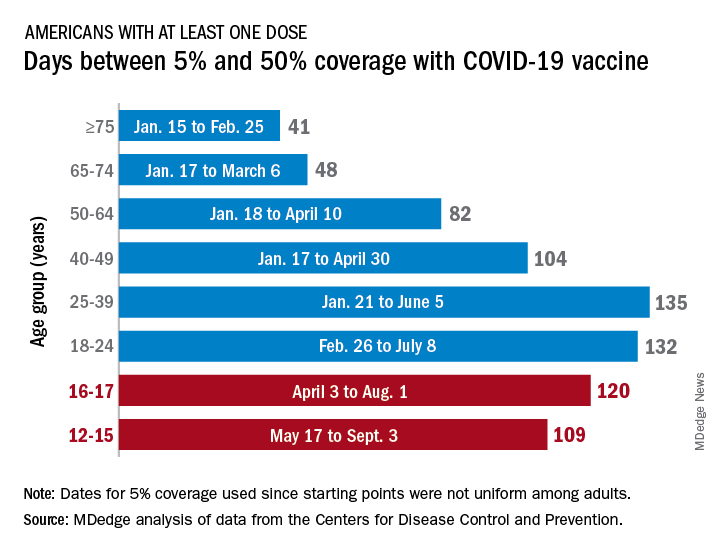

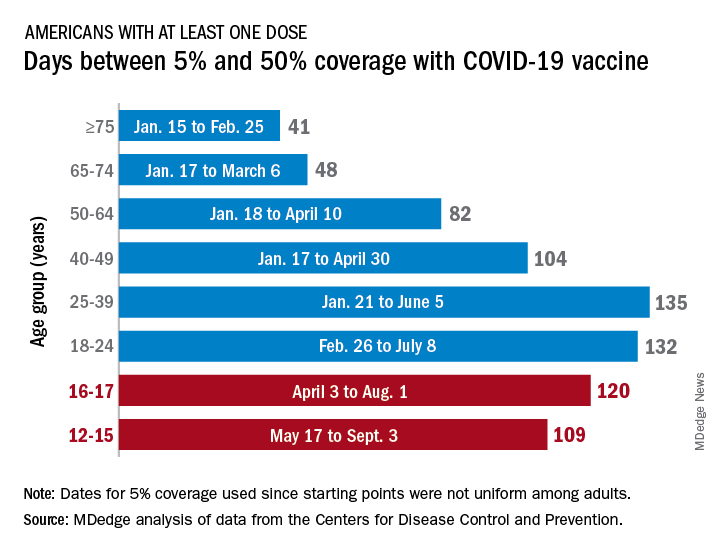

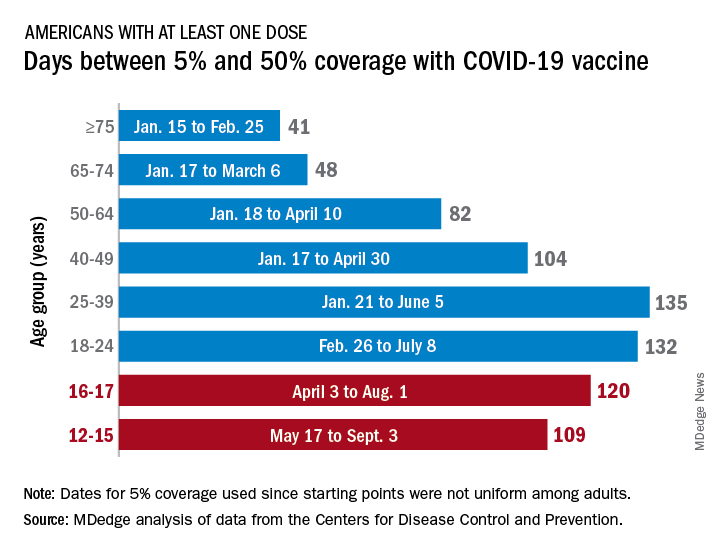

Children and COVID: A look at the pace of vaccination

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

The impact of modifiable risk factors such as diet and obesity in Pediatric MS patients

James Nicholas Brenton, M.D., is the director of the University of Virginia’s Pediatric and Young Adult MS and Related Disorders Clinic. He is also associate professor of neurology and pediatrics for clinical research and performs collaborative clinical research within the field of pediatric MS. His research focuses on pediatric demyelinating disease and autoimmune epilepsies.

As the director of a clinic focusing on pediatric and young adults MS and related disorders, how do modifiable risk factors such as obesity, smoking, et cetera, increase the risk of MS in general?

Dr. Brenton: There are several risk factors for pediatric-onset MS. When I say pediatric-onset, I'm referring to patients with clinical onset of MS prior to the age of 18 years. Some MS risk factors are not considered “modifiable,” such as genetic risks. The greatest genetic risk for MS is related to specific haplotypes in the HLA-DRB1 gene. Another risk factor that is less amenable to modification is early exposure to certain viruses, like the Epstein-Barr virus (Makhani, et al 2016).

On the other hand, there are several potentially modifiable risk factors for MS. This includes smoking - either first or second-hand smoke. In the case of pediatric MS patients, it is most often related to second-hand (or passive) smoke exposure (Lavery, et al 2019). Another example of a modifiable MS risk factor is vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D levels are influenced significantly by duration and intensity of direct exposure to sunlight, which depends (in part) on the geographic location of where you grow up. For example, those who live at higher latitudes (e.g. live further away from the equator) have less exposure to direct sunlight than a child who lives at lower latitudes (e.g. closer to the equator) (Banwell, et al 2011).

Obesity during childhood or adolescence is another modifiable risk factor for MS. Obesity’s risk for MS (like smoking) is dose-dependent – meaning, the more obese that you are, the higher your overall risk for future development of MS. In fact, the BMI in children with MS is markedly higher than their non-MS peers, and begins in early childhood, years before the clinical onset of the disease (Brenton, et al 2019).

There is mixed evidence regarding the impact of certain perinatal factors on future risk for MS. For example, some literature suggests that Caesarean delivery increases the risk of MS (Maghzi, et al 2012). Our research has found that infantile breastfeeding is associated with a lower future risk of pediatric-onset MS (Brenton, et al 2017).

Children are two to three times more likely to experience MS relapses compared with adults. How likely is it for the childhood obesity epidemic to lead to increased morbidity from MS or CIS, particularly in adolescent girls?

Dr. Brenton: Obesity is a systemic disease that manifests as excessive or abnormal accumulation of body fat. We know that chronic obesity leads to higher overall morbidity, lower quality of life, and reduced life expectancy. There are several common co-morbidities associated with obesity - like cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, polycystic ovarian syndrome, dyslipidemia, infertility, and some cancers (Abdelaal, et al 2017). Certainly, all these implications for the general population would pertain to those with MS who exhibit chronic obesity.

While we have fairly good evidence that obesity is a causal risk factor for the development of MS, there actually is a paucity of literature that has studied the impact of persistent obesity on an already established MS disease state. Several recent studies show that obesity is associated with a pro-inflammatory state in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients (Stampanoni, et al 2019). There are other studies that shown a direct association between MS-related neurologic disability and obesity – such that those with a greater waist circumference exhibit higher rates of neurologic disability (Fitzgerald, et al 2019).

Recent studies have assessed whether SNAP factors are associated with health outcomes. How does a modifiable SNAP risk score in people with multiple sclerosis impacts the likelihood of disability worsening??

Dr. Brenton: SNAP factors may not be as well known to some people in this field. SNAP factors refer to smoking (“S”), poor nutrition (“N”), alcohol consumption (“A”) and insufficient physical activity (“P”). These four factors appear to be the most preventable causes of morbidity within the general population. SNAP factors are common in people with MS. The most common SNAP factors in MS patients are poor nutrition and insufficient physical activity. Cross-sectionally, these factors appear to be associated with worsening neurologic disability (Marck, et al 2019).

There is data suggesting that SNAP factors, particularly those that increase over time, can associate with worsening disability when followed over several years. Importantly, your baseline SNAP score does not appear to predict your future level of disability (Marck, et al 2019). Collective SNAP scores have not yet been well-studied in pediatric MS patients, but are important to study - particularly given that children with MS reach maximum neurologic disability at a younger age than adult-onset MS patients (Renoux, et al 2007).

What are some of the best practices MS health care providers can engage in to promote exercise and rehabilitative protocols to significantly impact the physical and cognitive performance of MS patients?

Dr. Brenton: Even though pediatric MS patients exhibit relatively low levels of physical neurologic disability early in their disease, the physical activity levels of youth with MS are quite low. These patients engage in less moderate and vigorous physical activity when you compare them to their non-MS peers (Grover, et al 2016), but we still don't fully understand why this is the case. In fact, it may be related to several different factors - including pain, fatigue, sleep quality, MS disease activity, and psychological factors (such as depression, social anxiety, and perceptions of self-efficacy). In order to truly provide patient-specific interventions that positively impact physical activity we need to better understand what factors to study and how these factors play into the individual patient. For example, if high levels of fatigue are inhibiting a patient from being physically active, the provider should explore sources of fatigue: “how are sleep patterns?”, “are they napping throughout the day?”, “does the fatigue occur only after a period of physical activity, or is it persistent despite how active they are?” These are examples of questions that may lead a neurologist to different approaches for managing reduced physical activity.

Generally speaking however, pediatric and adult MS providers would ideally provide healthy nutrition guidance and counseling to all patients, regardless of their weight. Though there is no particular proven “MS diet,” in general, we recommend a balanced diet that is lower in saturated fats and processed sugars and higher in fruits and vegetables. In the case of a pediatric MS patient, it's important to have the family on board with consuming a healthier diet, as parental involvement increases the likelihood of healthy behavioral changes in the child.

It is important to ask patients targeted questions about their physical activity and assist with goal setting toward achievable targets. If the patient is receptive, a provider can advise on the use of digital interventions, like apps or internet-based social groups that incorporate education, accountability, and self-monitoring. What we do not know yet, but hope to know soon, is if physical activity and/or reducing obesity/improving diet can serve as a modifier of disease in kids and adults with MS. My current research is focused on studying the role of obesity and diet on the clinical course of children with MS. Many others are studying the role of physical activity on the disease course of children with MS. Suffice to say, there is much more to learn on the role of diet, body composition, and physical activity in youth with MS.

Lavery AM, Collins BN, Waldman AT, Hart CN, Bar-Or A, Marrie RA, Arnold D, O'Mahony J, Banwell B. The contribution of secondhand tobacco smoke exposure to pediatric multiple sclerosis risk. Mult Scler. 2019 Apr;25(4):515-522.

Maghzi AH, Etemadifar M, Heshmat-Ghahdarijani K, Nonahal S, Minagar A, Moradi V. Cesarean delivery may increase the risk of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18:468-471.

Marck CH, Aitken Z, Simpson S, Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA. Does a modifiable risk factor score predict disability worsening in people with multiple sclerosis? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019 Oct 11;5(4):2055217319881769.

Stampanoni Bassi M, Iezzi E, Buttari F, et al. Obesity worsens central inflammation and disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019:1352458519853473.

James Nicholas Brenton, M.D., is the director of the University of Virginia’s Pediatric and Young Adult MS and Related Disorders Clinic. He is also associate professor of neurology and pediatrics for clinical research and performs collaborative clinical research within the field of pediatric MS. His research focuses on pediatric demyelinating disease and autoimmune epilepsies.

As the director of a clinic focusing on pediatric and young adults MS and related disorders, how do modifiable risk factors such as obesity, smoking, et cetera, increase the risk of MS in general?

Dr. Brenton: There are several risk factors for pediatric-onset MS. When I say pediatric-onset, I'm referring to patients with clinical onset of MS prior to the age of 18 years. Some MS risk factors are not considered “modifiable,” such as genetic risks. The greatest genetic risk for MS is related to specific haplotypes in the HLA-DRB1 gene. Another risk factor that is less amenable to modification is early exposure to certain viruses, like the Epstein-Barr virus (Makhani, et al 2016).

On the other hand, there are several potentially modifiable risk factors for MS. This includes smoking - either first or second-hand smoke. In the case of pediatric MS patients, it is most often related to second-hand (or passive) smoke exposure (Lavery, et al 2019). Another example of a modifiable MS risk factor is vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D levels are influenced significantly by duration and intensity of direct exposure to sunlight, which depends (in part) on the geographic location of where you grow up. For example, those who live at higher latitudes (e.g. live further away from the equator) have less exposure to direct sunlight than a child who lives at lower latitudes (e.g. closer to the equator) (Banwell, et al 2011).

Obesity during childhood or adolescence is another modifiable risk factor for MS. Obesity’s risk for MS (like smoking) is dose-dependent – meaning, the more obese that you are, the higher your overall risk for future development of MS. In fact, the BMI in children with MS is markedly higher than their non-MS peers, and begins in early childhood, years before the clinical onset of the disease (Brenton, et al 2019).

There is mixed evidence regarding the impact of certain perinatal factors on future risk for MS. For example, some literature suggests that Caesarean delivery increases the risk of MS (Maghzi, et al 2012). Our research has found that infantile breastfeeding is associated with a lower future risk of pediatric-onset MS (Brenton, et al 2017).

Children are two to three times more likely to experience MS relapses compared with adults. How likely is it for the childhood obesity epidemic to lead to increased morbidity from MS or CIS, particularly in adolescent girls?

Dr. Brenton: Obesity is a systemic disease that manifests as excessive or abnormal accumulation of body fat. We know that chronic obesity leads to higher overall morbidity, lower quality of life, and reduced life expectancy. There are several common co-morbidities associated with obesity - like cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, polycystic ovarian syndrome, dyslipidemia, infertility, and some cancers (Abdelaal, et al 2017). Certainly, all these implications for the general population would pertain to those with MS who exhibit chronic obesity.

While we have fairly good evidence that obesity is a causal risk factor for the development of MS, there actually is a paucity of literature that has studied the impact of persistent obesity on an already established MS disease state. Several recent studies show that obesity is associated with a pro-inflammatory state in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients (Stampanoni, et al 2019). There are other studies that shown a direct association between MS-related neurologic disability and obesity – such that those with a greater waist circumference exhibit higher rates of neurologic disability (Fitzgerald, et al 2019).

Recent studies have assessed whether SNAP factors are associated with health outcomes. How does a modifiable SNAP risk score in people with multiple sclerosis impacts the likelihood of disability worsening??

Dr. Brenton: SNAP factors may not be as well known to some people in this field. SNAP factors refer to smoking (“S”), poor nutrition (“N”), alcohol consumption (“A”) and insufficient physical activity (“P”). These four factors appear to be the most preventable causes of morbidity within the general population. SNAP factors are common in people with MS. The most common SNAP factors in MS patients are poor nutrition and insufficient physical activity. Cross-sectionally, these factors appear to be associated with worsening neurologic disability (Marck, et al 2019).

There is data suggesting that SNAP factors, particularly those that increase over time, can associate with worsening disability when followed over several years. Importantly, your baseline SNAP score does not appear to predict your future level of disability (Marck, et al 2019). Collective SNAP scores have not yet been well-studied in pediatric MS patients, but are important to study - particularly given that children with MS reach maximum neurologic disability at a younger age than adult-onset MS patients (Renoux, et al 2007).

What are some of the best practices MS health care providers can engage in to promote exercise and rehabilitative protocols to significantly impact the physical and cognitive performance of MS patients?

Dr. Brenton: Even though pediatric MS patients exhibit relatively low levels of physical neurologic disability early in their disease, the physical activity levels of youth with MS are quite low. These patients engage in less moderate and vigorous physical activity when you compare them to their non-MS peers (Grover, et al 2016), but we still don't fully understand why this is the case. In fact, it may be related to several different factors - including pain, fatigue, sleep quality, MS disease activity, and psychological factors (such as depression, social anxiety, and perceptions of self-efficacy). In order to truly provide patient-specific interventions that positively impact physical activity we need to better understand what factors to study and how these factors play into the individual patient. For example, if high levels of fatigue are inhibiting a patient from being physically active, the provider should explore sources of fatigue: “how are sleep patterns?”, “are they napping throughout the day?”, “does the fatigue occur only after a period of physical activity, or is it persistent despite how active they are?” These are examples of questions that may lead a neurologist to different approaches for managing reduced physical activity.

Generally speaking however, pediatric and adult MS providers would ideally provide healthy nutrition guidance and counseling to all patients, regardless of their weight. Though there is no particular proven “MS diet,” in general, we recommend a balanced diet that is lower in saturated fats and processed sugars and higher in fruits and vegetables. In the case of a pediatric MS patient, it's important to have the family on board with consuming a healthier diet, as parental involvement increases the likelihood of healthy behavioral changes in the child.

It is important to ask patients targeted questions about their physical activity and assist with goal setting toward achievable targets. If the patient is receptive, a provider can advise on the use of digital interventions, like apps or internet-based social groups that incorporate education, accountability, and self-monitoring. What we do not know yet, but hope to know soon, is if physical activity and/or reducing obesity/improving diet can serve as a modifier of disease in kids and adults with MS. My current research is focused on studying the role of obesity and diet on the clinical course of children with MS. Many others are studying the role of physical activity on the disease course of children with MS. Suffice to say, there is much more to learn on the role of diet, body composition, and physical activity in youth with MS.

James Nicholas Brenton, M.D., is the director of the University of Virginia’s Pediatric and Young Adult MS and Related Disorders Clinic. He is also associate professor of neurology and pediatrics for clinical research and performs collaborative clinical research within the field of pediatric MS. His research focuses on pediatric demyelinating disease and autoimmune epilepsies.

As the director of a clinic focusing on pediatric and young adults MS and related disorders, how do modifiable risk factors such as obesity, smoking, et cetera, increase the risk of MS in general?

Dr. Brenton: There are several risk factors for pediatric-onset MS. When I say pediatric-onset, I'm referring to patients with clinical onset of MS prior to the age of 18 years. Some MS risk factors are not considered “modifiable,” such as genetic risks. The greatest genetic risk for MS is related to specific haplotypes in the HLA-DRB1 gene. Another risk factor that is less amenable to modification is early exposure to certain viruses, like the Epstein-Barr virus (Makhani, et al 2016).

On the other hand, there are several potentially modifiable risk factors for MS. This includes smoking - either first or second-hand smoke. In the case of pediatric MS patients, it is most often related to second-hand (or passive) smoke exposure (Lavery, et al 2019). Another example of a modifiable MS risk factor is vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D levels are influenced significantly by duration and intensity of direct exposure to sunlight, which depends (in part) on the geographic location of where you grow up. For example, those who live at higher latitudes (e.g. live further away from the equator) have less exposure to direct sunlight than a child who lives at lower latitudes (e.g. closer to the equator) (Banwell, et al 2011).

Obesity during childhood or adolescence is another modifiable risk factor for MS. Obesity’s risk for MS (like smoking) is dose-dependent – meaning, the more obese that you are, the higher your overall risk for future development of MS. In fact, the BMI in children with MS is markedly higher than their non-MS peers, and begins in early childhood, years before the clinical onset of the disease (Brenton, et al 2019).

There is mixed evidence regarding the impact of certain perinatal factors on future risk for MS. For example, some literature suggests that Caesarean delivery increases the risk of MS (Maghzi, et al 2012). Our research has found that infantile breastfeeding is associated with a lower future risk of pediatric-onset MS (Brenton, et al 2017).

Children are two to three times more likely to experience MS relapses compared with adults. How likely is it for the childhood obesity epidemic to lead to increased morbidity from MS or CIS, particularly in adolescent girls?

Dr. Brenton: Obesity is a systemic disease that manifests as excessive or abnormal accumulation of body fat. We know that chronic obesity leads to higher overall morbidity, lower quality of life, and reduced life expectancy. There are several common co-morbidities associated with obesity - like cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, polycystic ovarian syndrome, dyslipidemia, infertility, and some cancers (Abdelaal, et al 2017). Certainly, all these implications for the general population would pertain to those with MS who exhibit chronic obesity.

While we have fairly good evidence that obesity is a causal risk factor for the development of MS, there actually is a paucity of literature that has studied the impact of persistent obesity on an already established MS disease state. Several recent studies show that obesity is associated with a pro-inflammatory state in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid of MS patients (Stampanoni, et al 2019). There are other studies that shown a direct association between MS-related neurologic disability and obesity – such that those with a greater waist circumference exhibit higher rates of neurologic disability (Fitzgerald, et al 2019).

Recent studies have assessed whether SNAP factors are associated with health outcomes. How does a modifiable SNAP risk score in people with multiple sclerosis impacts the likelihood of disability worsening??

Dr. Brenton: SNAP factors may not be as well known to some people in this field. SNAP factors refer to smoking (“S”), poor nutrition (“N”), alcohol consumption (“A”) and insufficient physical activity (“P”). These four factors appear to be the most preventable causes of morbidity within the general population. SNAP factors are common in people with MS. The most common SNAP factors in MS patients are poor nutrition and insufficient physical activity. Cross-sectionally, these factors appear to be associated with worsening neurologic disability (Marck, et al 2019).

There is data suggesting that SNAP factors, particularly those that increase over time, can associate with worsening disability when followed over several years. Importantly, your baseline SNAP score does not appear to predict your future level of disability (Marck, et al 2019). Collective SNAP scores have not yet been well-studied in pediatric MS patients, but are important to study - particularly given that children with MS reach maximum neurologic disability at a younger age than adult-onset MS patients (Renoux, et al 2007).

What are some of the best practices MS health care providers can engage in to promote exercise and rehabilitative protocols to significantly impact the physical and cognitive performance of MS patients?

Dr. Brenton: Even though pediatric MS patients exhibit relatively low levels of physical neurologic disability early in their disease, the physical activity levels of youth with MS are quite low. These patients engage in less moderate and vigorous physical activity when you compare them to their non-MS peers (Grover, et al 2016), but we still don't fully understand why this is the case. In fact, it may be related to several different factors - including pain, fatigue, sleep quality, MS disease activity, and psychological factors (such as depression, social anxiety, and perceptions of self-efficacy). In order to truly provide patient-specific interventions that positively impact physical activity we need to better understand what factors to study and how these factors play into the individual patient. For example, if high levels of fatigue are inhibiting a patient from being physically active, the provider should explore sources of fatigue: “how are sleep patterns?”, “are they napping throughout the day?”, “does the fatigue occur only after a period of physical activity, or is it persistent despite how active they are?” These are examples of questions that may lead a neurologist to different approaches for managing reduced physical activity.

Generally speaking however, pediatric and adult MS providers would ideally provide healthy nutrition guidance and counseling to all patients, regardless of their weight. Though there is no particular proven “MS diet,” in general, we recommend a balanced diet that is lower in saturated fats and processed sugars and higher in fruits and vegetables. In the case of a pediatric MS patient, it's important to have the family on board with consuming a healthier diet, as parental involvement increases the likelihood of healthy behavioral changes in the child.

It is important to ask patients targeted questions about their physical activity and assist with goal setting toward achievable targets. If the patient is receptive, a provider can advise on the use of digital interventions, like apps or internet-based social groups that incorporate education, accountability, and self-monitoring. What we do not know yet, but hope to know soon, is if physical activity and/or reducing obesity/improving diet can serve as a modifier of disease in kids and adults with MS. My current research is focused on studying the role of obesity and diet on the clinical course of children with MS. Many others are studying the role of physical activity on the disease course of children with MS. Suffice to say, there is much more to learn on the role of diet, body composition, and physical activity in youth with MS.

Lavery AM, Collins BN, Waldman AT, Hart CN, Bar-Or A, Marrie RA, Arnold D, O'Mahony J, Banwell B. The contribution of secondhand tobacco smoke exposure to pediatric multiple sclerosis risk. Mult Scler. 2019 Apr;25(4):515-522.

Maghzi AH, Etemadifar M, Heshmat-Ghahdarijani K, Nonahal S, Minagar A, Moradi V. Cesarean delivery may increase the risk of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18:468-471.

Marck CH, Aitken Z, Simpson S, Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA. Does a modifiable risk factor score predict disability worsening in people with multiple sclerosis? Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019 Oct 11;5(4):2055217319881769.

Stampanoni Bassi M, Iezzi E, Buttari F, et al. Obesity worsens central inflammation and disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019:1352458519853473.

Lavery AM, Collins BN, Waldman AT, Hart CN, Bar-Or A, Marrie RA, Arnold D, O'Mahony J, Banwell B. The contribution of secondhand tobacco smoke exposure to pediatric multiple sclerosis risk. Mult Scler. 2019 Apr;25(4):515-522.