User login

Children and COVID: Vaccinations, new cases both rising

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

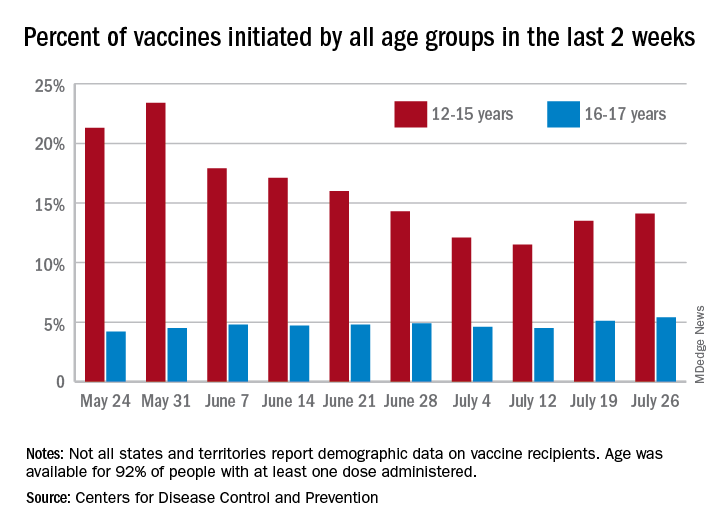

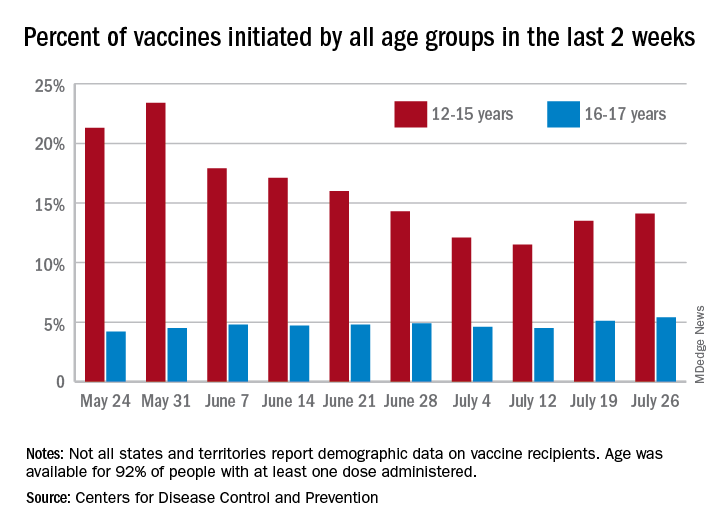

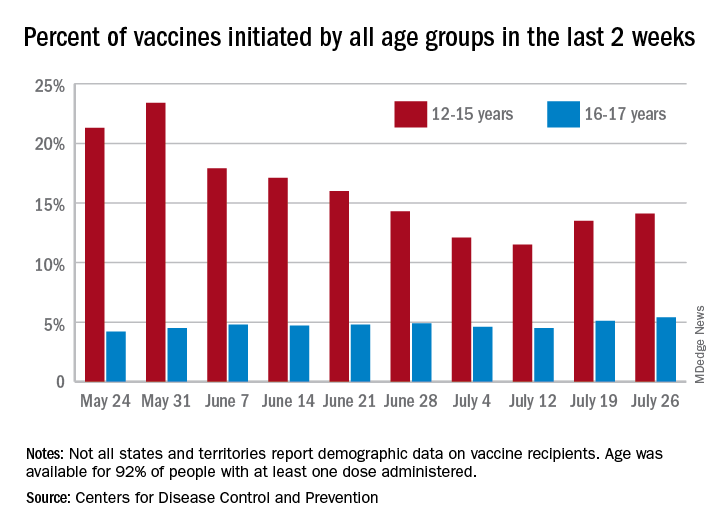

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

Nowhere to run and nowhere to hide

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Not surprisingly, the pandemic has torn at the already fraying fabric of many families. Cooped up away from friends and the emotional relief valve of school, even children who had been relatively easy to manage in the past have posed disciplinary challenges beyond their parents’ abilities to cope.

In a recent study from the Parenting in Context Lab of the University of Michigan (“Child Discipline During the Covid-19 Pandemic,” Family Snapshots: Life During the Pandemic, American Academy of Pediatrics, June 8 2021) researchers found that one in six parents surveyed (n = 3,000 adults) admitted to spanking. Nearly half of the parents said that they had yelled at or threatened their children.

Five out of six parents reported using what the investigators described as less harsh “positive discipline measures.” Three-quarters of these parents used “explaining” as a strategy and nearly the same number used either time-outs or sent the children to their rooms.

Again, not surprisingly, parents who had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) were more than twice as likely to spank. And parents who reported an episode of intimate partner violence (IPV) were more likely to resort to a harsh discipline strategy (yelling, threatening, or spanking).

Over my professional career I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about discipline and I have attempted to summarize my thoughts in a book titled, “How to Say No to Your Toddler” (Simon and Schuster, 2003), that has been published in four languages. Based on my observations, trying to explain to a misbehaving child the error of his ways is generally parental time not well spent. A well-structured time-out, preferably in a separate room with a door closed, is the most effective and safest discipline strategy.

However, as in all of my books, this advice on discipline was colored by the families in my practice and the audience for which I was writing, primarily middle class and upper middle class, reasonably affluent parents who buy books. These are usually folks who have homes in which children often have their own rooms, or where at least there are multiple rooms with doors – spaces to escape when tensions rise. Few of these parents have endured ACEs. Few have they experienced – nor have their children witnessed – IPV.

My advice that parents make only threats that can be safely carried, out such as time-out, and to always follow up on threats and promises, is valid regardless of a family’s socioeconomic situation. However, when it comes to choosing a consequence, my standard recommendation of a time-out can be difficult to follow for a family of six living in a three-room apartment, particularly during pandemic-dictated restrictions and lockdowns.

Of course there are alternatives to time-outs in a separate space, including an extended hug in a parental lap, but these responses require that the parents have been able to compose themselves well enough, and that they have the time. One of the important benefits of time-outs is that they can provide parents the time and space to reassess the situation and consider their role in the conflict. The bottom line is that a time-out is the safest and most effective form of discipline, but it requires space and a parent relatively unburdened of financial or emotional stress. Families without these luxuries are left with few alternatives other than physical or verbal abuse.

The AAP’s Family Snapshot concludes with the observation that “pediatricians and pediatric health care providers can continue to play an important role in supporting positive discipline strategies.” That is a difficult assignment even in prepandemic times, but for those of you working with families who lack the space and time to defuse disciplinary tensions, it is a heroic task.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Genetic testing for neurofibromatosis 1: An imperfect science

According to Peter Kannu, MB, ChB, DCH, PhD, a definitive diagnosis of NF1 can be made in most children using National Institutes of Health criteria published in 1988, which include the presence of two of the following:

- Six or more café au lait macules over 5 mm in diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

- Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma

- Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions

- Two or more Lisch nodules

- Optic glioma

- A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of long bone cortex, with or without pseudarthrosis

- Having a first-degree relative with NF1

For example, in the case of an 8-year-old child who presents with multiple café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, Lisch nodules, and an optic glioma, “the diagnosis is secure and genetic testing is not going to change clinical management or surveillance,” Dr. Kannu, a clinical geneticist at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The only reason for genetic testing in this situation is so that we know the mutation in order to inform reproductive risk counseling in the future.”

However, while a diagnosis of NF1 may be suspected in a 6- to 12-month-old presenting with only café au lait macules, “the diagnosis is not secure because the clinical criteria cannot be met. In this situation, a genetic test can speed up the diagnosis,” he added. “Or, if the test is negative, it can decrease your suspicion for NF1 and you wouldn’t refer the child on to an NF1 screening clinic for intensive surveillance.”

Dr. Kannu based his remarks largely on his 5 years working at the multidisciplinary Genodermatoses Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Founded in 2015, the clinic is a “one-stop shop” designed to reduce the wait time for diagnosis and management and the number of hospital visits. The team – composed of a dermatologist, medical geneticist, genetic counselor, residents, and fellows – meets to review the charts of each patient before the appointment, and decides on a preliminary management plan. All children are then seen by one of the trainees in the clinic who devises a differential diagnosis that is presented to staff physicians, at which point genetic testing is decided on. A genetics counselor handles follow-up for those who do have genetic testing.

In 2018, Dr. Kannu and colleagues conducted an informal review of 300 patients who had been seen in the clinic. The mean age at referral was about 6 years, 51% were female, and the top three referral sources were pediatricians (51%), dermatologists (18%), and family physicians (18%). Of the 300 children, 84 (28%) were confirmed to have a diagnosis of NF1. Two patients were diagnosed with NF2 and 5% of the total cohort was diagnosed with mosaic NF1 (MNF1), “which is higher than what you would expect based on the incidence of MNF1 in the literature,” he said.

He separates genetic tests for NF1 into one of two categories: Conventional testing, which is offered by most labs in North America; and comprehensive testing, which is offered by the medical genomics lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Conventional testing focuses on the exons, “the protein coding regions of the gene where most of the mutations lie,” he said. “The test also sequences about 20 base pairs or so of the intron exon boundary and may pick up some intronic mutations. But this test will not detect anything that’s hidden deep in the intronic region.”

Comprehensive testing, meanwhile, checks for mutations in both introns and exons.

Dr. Kannu and colleagues published a case of a paraspinal ganglioneuroma in the proband of a large family with mild cutaneous manifestations of NF1, carrying a deep NF1 intronic mutation. “The clinicians were suspicious that this was NF1, rightly so. The diagnosis was only confirmed after we sent samples to the University of Alabama lab where the deep intronic mutation was found,” he said.

The other situation where conventional genetic testing may be negative is in the case of MNF1, where there “are mutations in some cells but not all cells,” Dr. Kannu explained. “It may only be present in the melanocytes of the skin but not present in the lymphocytes in the blood. Mosaicism is characterized by the regional distribution of pigmentary or other NF1 associated findings. Mosaicism may be detected in the blood if it’s more than 20%. Anything less than that is not detected with conventional genetic testing using DNA from blood and requires extracting DNA from a punch biopsy sample of a café au lait macule.”

The differential diagnosis of café au lait macules includes several conditions associated mutations in the RAS pathway. “Neurofibromin is a key signal of molecules which regulates the activation of RAS,” Dr. Kannu said. “A close binding partner of NF1 is SPRED 1. We know that mutations in this gene cause Legius syndrome, a condition which presents with multiple café au lait macules.”

Two key receptors in the RAS pathway include EGFR and KITL, he continued. Mutations in the EGFR receptor cause a rare condition known as neonatal skin and bowel disease, while mutations in the KITL receptor cause familial progressive hyperpigmentation with or without hypopigmentation. “Looking into the pathway and focusing downstream of RAS, we have genes such as RAF and CBL, which are mutated in Noonan syndrome,” he said. “Further along in the pathway you have mutations in PTEN, which cause Cowden syndrome, and mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which cause tuberous sclerosis. Mutations in any of these genes can also present with café au lait macules.”

During a question-and-answer session Dr. Kannu was asked to comment about revised diagnostic criteria for NF1 based on an international consensus recommendation, such as changes in the eye that require a formal opthalmologic examination, which were recently published.

“We are understanding more about the phenotype,” he said. “If you fulfill diagnostic criteria for NF1, the main reasons for doing genetic testing are, one, if the family wants to know that information, and two, it informs our reproductive risk counseling. Genotype-phenotype correlations do exist in NF1 but they’re not very robust, so that information is not clinically useful.”

Dr. Kannu disclosed that he has been an advisory board member for Ipsen, Novartis, and Alexion. He has also been a primary investigator for QED and Clementia.

According to Peter Kannu, MB, ChB, DCH, PhD, a definitive diagnosis of NF1 can be made in most children using National Institutes of Health criteria published in 1988, which include the presence of two of the following:

- Six or more café au lait macules over 5 mm in diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

- Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma

- Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions

- Two or more Lisch nodules

- Optic glioma

- A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of long bone cortex, with or without pseudarthrosis

- Having a first-degree relative with NF1

For example, in the case of an 8-year-old child who presents with multiple café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, Lisch nodules, and an optic glioma, “the diagnosis is secure and genetic testing is not going to change clinical management or surveillance,” Dr. Kannu, a clinical geneticist at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The only reason for genetic testing in this situation is so that we know the mutation in order to inform reproductive risk counseling in the future.”

However, while a diagnosis of NF1 may be suspected in a 6- to 12-month-old presenting with only café au lait macules, “the diagnosis is not secure because the clinical criteria cannot be met. In this situation, a genetic test can speed up the diagnosis,” he added. “Or, if the test is negative, it can decrease your suspicion for NF1 and you wouldn’t refer the child on to an NF1 screening clinic for intensive surveillance.”

Dr. Kannu based his remarks largely on his 5 years working at the multidisciplinary Genodermatoses Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Founded in 2015, the clinic is a “one-stop shop” designed to reduce the wait time for diagnosis and management and the number of hospital visits. The team – composed of a dermatologist, medical geneticist, genetic counselor, residents, and fellows – meets to review the charts of each patient before the appointment, and decides on a preliminary management plan. All children are then seen by one of the trainees in the clinic who devises a differential diagnosis that is presented to staff physicians, at which point genetic testing is decided on. A genetics counselor handles follow-up for those who do have genetic testing.

In 2018, Dr. Kannu and colleagues conducted an informal review of 300 patients who had been seen in the clinic. The mean age at referral was about 6 years, 51% were female, and the top three referral sources were pediatricians (51%), dermatologists (18%), and family physicians (18%). Of the 300 children, 84 (28%) were confirmed to have a diagnosis of NF1. Two patients were diagnosed with NF2 and 5% of the total cohort was diagnosed with mosaic NF1 (MNF1), “which is higher than what you would expect based on the incidence of MNF1 in the literature,” he said.

He separates genetic tests for NF1 into one of two categories: Conventional testing, which is offered by most labs in North America; and comprehensive testing, which is offered by the medical genomics lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Conventional testing focuses on the exons, “the protein coding regions of the gene where most of the mutations lie,” he said. “The test also sequences about 20 base pairs or so of the intron exon boundary and may pick up some intronic mutations. But this test will not detect anything that’s hidden deep in the intronic region.”

Comprehensive testing, meanwhile, checks for mutations in both introns and exons.

Dr. Kannu and colleagues published a case of a paraspinal ganglioneuroma in the proband of a large family with mild cutaneous manifestations of NF1, carrying a deep NF1 intronic mutation. “The clinicians were suspicious that this was NF1, rightly so. The diagnosis was only confirmed after we sent samples to the University of Alabama lab where the deep intronic mutation was found,” he said.

The other situation where conventional genetic testing may be negative is in the case of MNF1, where there “are mutations in some cells but not all cells,” Dr. Kannu explained. “It may only be present in the melanocytes of the skin but not present in the lymphocytes in the blood. Mosaicism is characterized by the regional distribution of pigmentary or other NF1 associated findings. Mosaicism may be detected in the blood if it’s more than 20%. Anything less than that is not detected with conventional genetic testing using DNA from blood and requires extracting DNA from a punch biopsy sample of a café au lait macule.”

The differential diagnosis of café au lait macules includes several conditions associated mutations in the RAS pathway. “Neurofibromin is a key signal of molecules which regulates the activation of RAS,” Dr. Kannu said. “A close binding partner of NF1 is SPRED 1. We know that mutations in this gene cause Legius syndrome, a condition which presents with multiple café au lait macules.”

Two key receptors in the RAS pathway include EGFR and KITL, he continued. Mutations in the EGFR receptor cause a rare condition known as neonatal skin and bowel disease, while mutations in the KITL receptor cause familial progressive hyperpigmentation with or without hypopigmentation. “Looking into the pathway and focusing downstream of RAS, we have genes such as RAF and CBL, which are mutated in Noonan syndrome,” he said. “Further along in the pathway you have mutations in PTEN, which cause Cowden syndrome, and mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which cause tuberous sclerosis. Mutations in any of these genes can also present with café au lait macules.”

During a question-and-answer session Dr. Kannu was asked to comment about revised diagnostic criteria for NF1 based on an international consensus recommendation, such as changes in the eye that require a formal opthalmologic examination, which were recently published.

“We are understanding more about the phenotype,” he said. “If you fulfill diagnostic criteria for NF1, the main reasons for doing genetic testing are, one, if the family wants to know that information, and two, it informs our reproductive risk counseling. Genotype-phenotype correlations do exist in NF1 but they’re not very robust, so that information is not clinically useful.”

Dr. Kannu disclosed that he has been an advisory board member for Ipsen, Novartis, and Alexion. He has also been a primary investigator for QED and Clementia.

According to Peter Kannu, MB, ChB, DCH, PhD, a definitive diagnosis of NF1 can be made in most children using National Institutes of Health criteria published in 1988, which include the presence of two of the following:

- Six or more café au lait macules over 5 mm in diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

- Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma

- Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions

- Two or more Lisch nodules

- Optic glioma

- A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of long bone cortex, with or without pseudarthrosis

- Having a first-degree relative with NF1

For example, in the case of an 8-year-old child who presents with multiple café au lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, Lisch nodules, and an optic glioma, “the diagnosis is secure and genetic testing is not going to change clinical management or surveillance,” Dr. Kannu, a clinical geneticist at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The only reason for genetic testing in this situation is so that we know the mutation in order to inform reproductive risk counseling in the future.”

However, while a diagnosis of NF1 may be suspected in a 6- to 12-month-old presenting with only café au lait macules, “the diagnosis is not secure because the clinical criteria cannot be met. In this situation, a genetic test can speed up the diagnosis,” he added. “Or, if the test is negative, it can decrease your suspicion for NF1 and you wouldn’t refer the child on to an NF1 screening clinic for intensive surveillance.”

Dr. Kannu based his remarks largely on his 5 years working at the multidisciplinary Genodermatoses Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Founded in 2015, the clinic is a “one-stop shop” designed to reduce the wait time for diagnosis and management and the number of hospital visits. The team – composed of a dermatologist, medical geneticist, genetic counselor, residents, and fellows – meets to review the charts of each patient before the appointment, and decides on a preliminary management plan. All children are then seen by one of the trainees in the clinic who devises a differential diagnosis that is presented to staff physicians, at which point genetic testing is decided on. A genetics counselor handles follow-up for those who do have genetic testing.

In 2018, Dr. Kannu and colleagues conducted an informal review of 300 patients who had been seen in the clinic. The mean age at referral was about 6 years, 51% were female, and the top three referral sources were pediatricians (51%), dermatologists (18%), and family physicians (18%). Of the 300 children, 84 (28%) were confirmed to have a diagnosis of NF1. Two patients were diagnosed with NF2 and 5% of the total cohort was diagnosed with mosaic NF1 (MNF1), “which is higher than what you would expect based on the incidence of MNF1 in the literature,” he said.

He separates genetic tests for NF1 into one of two categories: Conventional testing, which is offered by most labs in North America; and comprehensive testing, which is offered by the medical genomics lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Conventional testing focuses on the exons, “the protein coding regions of the gene where most of the mutations lie,” he said. “The test also sequences about 20 base pairs or so of the intron exon boundary and may pick up some intronic mutations. But this test will not detect anything that’s hidden deep in the intronic region.”

Comprehensive testing, meanwhile, checks for mutations in both introns and exons.

Dr. Kannu and colleagues published a case of a paraspinal ganglioneuroma in the proband of a large family with mild cutaneous manifestations of NF1, carrying a deep NF1 intronic mutation. “The clinicians were suspicious that this was NF1, rightly so. The diagnosis was only confirmed after we sent samples to the University of Alabama lab where the deep intronic mutation was found,” he said.

The other situation where conventional genetic testing may be negative is in the case of MNF1, where there “are mutations in some cells but not all cells,” Dr. Kannu explained. “It may only be present in the melanocytes of the skin but not present in the lymphocytes in the blood. Mosaicism is characterized by the regional distribution of pigmentary or other NF1 associated findings. Mosaicism may be detected in the blood if it’s more than 20%. Anything less than that is not detected with conventional genetic testing using DNA from blood and requires extracting DNA from a punch biopsy sample of a café au lait macule.”

The differential diagnosis of café au lait macules includes several conditions associated mutations in the RAS pathway. “Neurofibromin is a key signal of molecules which regulates the activation of RAS,” Dr. Kannu said. “A close binding partner of NF1 is SPRED 1. We know that mutations in this gene cause Legius syndrome, a condition which presents with multiple café au lait macules.”

Two key receptors in the RAS pathway include EGFR and KITL, he continued. Mutations in the EGFR receptor cause a rare condition known as neonatal skin and bowel disease, while mutations in the KITL receptor cause familial progressive hyperpigmentation with or without hypopigmentation. “Looking into the pathway and focusing downstream of RAS, we have genes such as RAF and CBL, which are mutated in Noonan syndrome,” he said. “Further along in the pathway you have mutations in PTEN, which cause Cowden syndrome, and mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which cause tuberous sclerosis. Mutations in any of these genes can also present with café au lait macules.”

During a question-and-answer session Dr. Kannu was asked to comment about revised diagnostic criteria for NF1 based on an international consensus recommendation, such as changes in the eye that require a formal opthalmologic examination, which were recently published.

“We are understanding more about the phenotype,” he said. “If you fulfill diagnostic criteria for NF1, the main reasons for doing genetic testing are, one, if the family wants to know that information, and two, it informs our reproductive risk counseling. Genotype-phenotype correlations do exist in NF1 but they’re not very robust, so that information is not clinically useful.”

Dr. Kannu disclosed that he has been an advisory board member for Ipsen, Novartis, and Alexion. He has also been a primary investigator for QED and Clementia.

FROM SPD 2021

Childhood deprivation affects later executive function

Exposure to deprivation in early life was significantly associated with impaired executive functioning in children and adolescents, based on data from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 91 studies.

Previous research has shown connections between early-life adversity (ELA) and changes in psychological, cognitive, and neurobiological development, including increased risk of anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, suicidality, and substance use disorder; however, research focusing on the associations between different types of ELA and specific processes is limited, wrote Dylan Johnson, MSc, of the University of Toronto and colleagues.

“We directly addressed this gap in the literature by examining the association between the type of ELA and executive functioning in children and youth,” they said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 91 articles including 82 unique cohorts and 31,188 unique individuals aged 1-18 years.

The articles were selected from Embase, ERIC, MEDLINE, and PsycInfo databases and published up to Dec. 31, 2020. The primary outcomes were measures of the three domains of executive functioning: cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory. To correct for small sample sizes in some studies, the researchers standardized their measures of association into Hedges g effect sizes.

Overall, the pooled estimates of the association of any childhood adversity with the three domains of executive functioning showed significant heterogeneity, with Hedges g effects of –0.49 for cognitive flexibility, –0.39 for inhibitory control, and –0.47 for working memory.

The researchers also examined a subsample of ELA–executive functioning associations in categories of early-life exposure to threat, compared with early-life deprivation, including 56 of the original 91 articles. In this analysis, significantly lower inhibitory control was associated with deprivation compared to threat (Hedges g –0.43 vs. –0.27). Similarly, significantly lower working memory was associated with deprivation, compared with threat (Hedges g –0.54 vs. Hedges g –0.28). For both inhibitory control and working memory, the association of adversity was not moderated by the age or sex of the study participants, study design, outcome quality, or selection quality, the researchers noted.

No significant difference in affect of exposure threat vs. deprivation was noted for the association with cognitive flexibility. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear, the researchers said. “Some evidence suggests that individuals who grow up in unpredictable environments may have reduced inhibitory control but enhanced cognitive flexibility,” they noted.

However, the overall results suggest that exposure to deprivation may be associated with neurodevelopmental changes that support the development of executive functioning, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the substantial heterogeneity in the pooled estimates and the need to consider variation in study design, the researchers noted. In addition, the cross-sectional design of many studies prevented conclusions about causality between ELA and executive functioning, they said.

“Future research should explore the differences between threat and deprivation when emotionally salient executive functioning measures are used,” the researchers emphasized. “Threat experiences are often associated with alterations in emotional processing, and different findings may be observed when investigating emotionally salient executive functioning outcomes,” they concluded.

Prevention and intervention plans needed

“Although numerous studies have examined associations between ELA and executive functioning, the associations of threat and deprivation with specific executive functioning domains (e.g., cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory) have not been explored comprehensively,” wrote Beth S. Slomine, PhD, and Nikeea Copeland-Linder, PhD, of the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Johns Hopkins University School, Baltimore, in an accompanying editorial.

The study is “critical and timely” because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s exposure to deprivation, the authors said. “Many children have experienced the death of family members or friends, food and housing insecurity owing to the economic recession, school closures, loss of critical support services, and increased isolation because of social distancing measures,” and these effects are even greater for children already living in poverty and those with developmental disabilities, they noted.

More resources are needed to develop and implement ELA prevention policies, as well as early intervention plans, the editorialists said.

“Early intervention programs have a great potential to reduce the risk of ELA and promote executive functioning development,” they said. “These programs, such as family support and preschool services, are viable solutions for children and their families,” they added. Although the pandemic prevented the use of many support services for children at risk, the adoption of telehealth technology means that “it is now more feasible for cognitive rehabilitation experts to implement the telehealth technology to train parents and school staff on how to assist with the delivery of interventions in real-world settings and how to promote executive functioning in daily life,” they noted.

Overall, the study findings highlight the urgency of identifying ELA and implementing strategies to reduce and prevent ELA, and to provide early intervention to mitigate the impact of ELA on executive function in children, the editorialists emphasized.

Data bring understanding, but barriers remain

“At this point, there are data demonstrating the significant impact that adverse childhood experiences have on health outcomes – from worsened mental health to an increased risk for cancer and diabetes,” said Kelly A. Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, in an interview.

“Physicians – myself included – tend to lump all these experiences together when thinking about future health outcomes,” Dr. Curran said. “However, there are evolving data that neurocognitive outcomes may be different based on the type of early-life adversity experienced. This meta-analysis examines the risk of different neurocognitive impact of threat versus deprivation types of adversity, which is important to pediatricians because it helps us to better understand the risks that our patients may experience,” she explained.

“The results of this meta-analysis were especially intriguing because I hadn’t previously considered the impact that different types of adversity had on neurocognitive development,” said Dr. Curran. “This study caused me to think about these experiences differently, and as I reflect on the patients I have cared for over the years, I can see the difference in their outcomes,” she said.

Many barriers persist in addressing the effects of early-life deprivation on executive function, Dr. Curran said.

“First are barriers around identification of these children and adolescents, who may not have regular contact with the medical system. Additionally, it’s important to provide resources for parents and caregivers – this includes creating a strong support network and providing education about the impact of these experiences,” she noted. “There are also barriers to identifying and connecting with what resources will help children at risk of poor neurodevelopmental outcomes,” she added.

“Now that we know that children who have experienced early-life deprivation are at increased risk of worsened neurodevelopmental outcomes, it will be important to understand what interventions can help improve their outcomes,” Dr. Curran said.

The study was supported by a Connaught New Researcher Award from the University of Toronto. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Slomine disclosed book royalties from Cambridge University Press unrelated to this study. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Exposure to deprivation in early life was significantly associated with impaired executive functioning in children and adolescents, based on data from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 91 studies.

Previous research has shown connections between early-life adversity (ELA) and changes in psychological, cognitive, and neurobiological development, including increased risk of anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, suicidality, and substance use disorder; however, research focusing on the associations between different types of ELA and specific processes is limited, wrote Dylan Johnson, MSc, of the University of Toronto and colleagues.

“We directly addressed this gap in the literature by examining the association between the type of ELA and executive functioning in children and youth,” they said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 91 articles including 82 unique cohorts and 31,188 unique individuals aged 1-18 years.

The articles were selected from Embase, ERIC, MEDLINE, and PsycInfo databases and published up to Dec. 31, 2020. The primary outcomes were measures of the three domains of executive functioning: cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory. To correct for small sample sizes in some studies, the researchers standardized their measures of association into Hedges g effect sizes.

Overall, the pooled estimates of the association of any childhood adversity with the three domains of executive functioning showed significant heterogeneity, with Hedges g effects of –0.49 for cognitive flexibility, –0.39 for inhibitory control, and –0.47 for working memory.

The researchers also examined a subsample of ELA–executive functioning associations in categories of early-life exposure to threat, compared with early-life deprivation, including 56 of the original 91 articles. In this analysis, significantly lower inhibitory control was associated with deprivation compared to threat (Hedges g –0.43 vs. –0.27). Similarly, significantly lower working memory was associated with deprivation, compared with threat (Hedges g –0.54 vs. Hedges g –0.28). For both inhibitory control and working memory, the association of adversity was not moderated by the age or sex of the study participants, study design, outcome quality, or selection quality, the researchers noted.

No significant difference in affect of exposure threat vs. deprivation was noted for the association with cognitive flexibility. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear, the researchers said. “Some evidence suggests that individuals who grow up in unpredictable environments may have reduced inhibitory control but enhanced cognitive flexibility,” they noted.

However, the overall results suggest that exposure to deprivation may be associated with neurodevelopmental changes that support the development of executive functioning, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the substantial heterogeneity in the pooled estimates and the need to consider variation in study design, the researchers noted. In addition, the cross-sectional design of many studies prevented conclusions about causality between ELA and executive functioning, they said.

“Future research should explore the differences between threat and deprivation when emotionally salient executive functioning measures are used,” the researchers emphasized. “Threat experiences are often associated with alterations in emotional processing, and different findings may be observed when investigating emotionally salient executive functioning outcomes,” they concluded.

Prevention and intervention plans needed

“Although numerous studies have examined associations between ELA and executive functioning, the associations of threat and deprivation with specific executive functioning domains (e.g., cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory) have not been explored comprehensively,” wrote Beth S. Slomine, PhD, and Nikeea Copeland-Linder, PhD, of the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Johns Hopkins University School, Baltimore, in an accompanying editorial.

The study is “critical and timely” because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s exposure to deprivation, the authors said. “Many children have experienced the death of family members or friends, food and housing insecurity owing to the economic recession, school closures, loss of critical support services, and increased isolation because of social distancing measures,” and these effects are even greater for children already living in poverty and those with developmental disabilities, they noted.

More resources are needed to develop and implement ELA prevention policies, as well as early intervention plans, the editorialists said.

“Early intervention programs have a great potential to reduce the risk of ELA and promote executive functioning development,” they said. “These programs, such as family support and preschool services, are viable solutions for children and their families,” they added. Although the pandemic prevented the use of many support services for children at risk, the adoption of telehealth technology means that “it is now more feasible for cognitive rehabilitation experts to implement the telehealth technology to train parents and school staff on how to assist with the delivery of interventions in real-world settings and how to promote executive functioning in daily life,” they noted.

Overall, the study findings highlight the urgency of identifying ELA and implementing strategies to reduce and prevent ELA, and to provide early intervention to mitigate the impact of ELA on executive function in children, the editorialists emphasized.

Data bring understanding, but barriers remain

“At this point, there are data demonstrating the significant impact that adverse childhood experiences have on health outcomes – from worsened mental health to an increased risk for cancer and diabetes,” said Kelly A. Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, in an interview.

“Physicians – myself included – tend to lump all these experiences together when thinking about future health outcomes,” Dr. Curran said. “However, there are evolving data that neurocognitive outcomes may be different based on the type of early-life adversity experienced. This meta-analysis examines the risk of different neurocognitive impact of threat versus deprivation types of adversity, which is important to pediatricians because it helps us to better understand the risks that our patients may experience,” she explained.

“The results of this meta-analysis were especially intriguing because I hadn’t previously considered the impact that different types of adversity had on neurocognitive development,” said Dr. Curran. “This study caused me to think about these experiences differently, and as I reflect on the patients I have cared for over the years, I can see the difference in their outcomes,” she said.

Many barriers persist in addressing the effects of early-life deprivation on executive function, Dr. Curran said.

“First are barriers around identification of these children and adolescents, who may not have regular contact with the medical system. Additionally, it’s important to provide resources for parents and caregivers – this includes creating a strong support network and providing education about the impact of these experiences,” she noted. “There are also barriers to identifying and connecting with what resources will help children at risk of poor neurodevelopmental outcomes,” she added.

“Now that we know that children who have experienced early-life deprivation are at increased risk of worsened neurodevelopmental outcomes, it will be important to understand what interventions can help improve their outcomes,” Dr. Curran said.

The study was supported by a Connaught New Researcher Award from the University of Toronto. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Slomine disclosed book royalties from Cambridge University Press unrelated to this study. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

Exposure to deprivation in early life was significantly associated with impaired executive functioning in children and adolescents, based on data from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 91 studies.

Previous research has shown connections between early-life adversity (ELA) and changes in psychological, cognitive, and neurobiological development, including increased risk of anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, suicidality, and substance use disorder; however, research focusing on the associations between different types of ELA and specific processes is limited, wrote Dylan Johnson, MSc, of the University of Toronto and colleagues.

“We directly addressed this gap in the literature by examining the association between the type of ELA and executive functioning in children and youth,” they said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 91 articles including 82 unique cohorts and 31,188 unique individuals aged 1-18 years.

The articles were selected from Embase, ERIC, MEDLINE, and PsycInfo databases and published up to Dec. 31, 2020. The primary outcomes were measures of the three domains of executive functioning: cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory. To correct for small sample sizes in some studies, the researchers standardized their measures of association into Hedges g effect sizes.

Overall, the pooled estimates of the association of any childhood adversity with the three domains of executive functioning showed significant heterogeneity, with Hedges g effects of –0.49 for cognitive flexibility, –0.39 for inhibitory control, and –0.47 for working memory.

The researchers also examined a subsample of ELA–executive functioning associations in categories of early-life exposure to threat, compared with early-life deprivation, including 56 of the original 91 articles. In this analysis, significantly lower inhibitory control was associated with deprivation compared to threat (Hedges g –0.43 vs. –0.27). Similarly, significantly lower working memory was associated with deprivation, compared with threat (Hedges g –0.54 vs. Hedges g –0.28). For both inhibitory control and working memory, the association of adversity was not moderated by the age or sex of the study participants, study design, outcome quality, or selection quality, the researchers noted.

No significant difference in affect of exposure threat vs. deprivation was noted for the association with cognitive flexibility. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear, the researchers said. “Some evidence suggests that individuals who grow up in unpredictable environments may have reduced inhibitory control but enhanced cognitive flexibility,” they noted.

However, the overall results suggest that exposure to deprivation may be associated with neurodevelopmental changes that support the development of executive functioning, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the substantial heterogeneity in the pooled estimates and the need to consider variation in study design, the researchers noted. In addition, the cross-sectional design of many studies prevented conclusions about causality between ELA and executive functioning, they said.

“Future research should explore the differences between threat and deprivation when emotionally salient executive functioning measures are used,” the researchers emphasized. “Threat experiences are often associated with alterations in emotional processing, and different findings may be observed when investigating emotionally salient executive functioning outcomes,” they concluded.

Prevention and intervention plans needed

“Although numerous studies have examined associations between ELA and executive functioning, the associations of threat and deprivation with specific executive functioning domains (e.g., cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory) have not been explored comprehensively,” wrote Beth S. Slomine, PhD, and Nikeea Copeland-Linder, PhD, of the Kennedy Krieger Institute, Johns Hopkins University School, Baltimore, in an accompanying editorial.

The study is “critical and timely” because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s exposure to deprivation, the authors said. “Many children have experienced the death of family members or friends, food and housing insecurity owing to the economic recession, school closures, loss of critical support services, and increased isolation because of social distancing measures,” and these effects are even greater for children already living in poverty and those with developmental disabilities, they noted.

More resources are needed to develop and implement ELA prevention policies, as well as early intervention plans, the editorialists said.

“Early intervention programs have a great potential to reduce the risk of ELA and promote executive functioning development,” they said. “These programs, such as family support and preschool services, are viable solutions for children and their families,” they added. Although the pandemic prevented the use of many support services for children at risk, the adoption of telehealth technology means that “it is now more feasible for cognitive rehabilitation experts to implement the telehealth technology to train parents and school staff on how to assist with the delivery of interventions in real-world settings and how to promote executive functioning in daily life,” they noted.

Overall, the study findings highlight the urgency of identifying ELA and implementing strategies to reduce and prevent ELA, and to provide early intervention to mitigate the impact of ELA on executive function in children, the editorialists emphasized.

Data bring understanding, but barriers remain

“At this point, there are data demonstrating the significant impact that adverse childhood experiences have on health outcomes – from worsened mental health to an increased risk for cancer and diabetes,” said Kelly A. Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, in an interview.

“Physicians – myself included – tend to lump all these experiences together when thinking about future health outcomes,” Dr. Curran said. “However, there are evolving data that neurocognitive outcomes may be different based on the type of early-life adversity experienced. This meta-analysis examines the risk of different neurocognitive impact of threat versus deprivation types of adversity, which is important to pediatricians because it helps us to better understand the risks that our patients may experience,” she explained.

“The results of this meta-analysis were especially intriguing because I hadn’t previously considered the impact that different types of adversity had on neurocognitive development,” said Dr. Curran. “This study caused me to think about these experiences differently, and as I reflect on the patients I have cared for over the years, I can see the difference in their outcomes,” she said.

Many barriers persist in addressing the effects of early-life deprivation on executive function, Dr. Curran said.

“First are barriers around identification of these children and adolescents, who may not have regular contact with the medical system. Additionally, it’s important to provide resources for parents and caregivers – this includes creating a strong support network and providing education about the impact of these experiences,” she noted. “There are also barriers to identifying and connecting with what resources will help children at risk of poor neurodevelopmental outcomes,” she added.

“Now that we know that children who have experienced early-life deprivation are at increased risk of worsened neurodevelopmental outcomes, it will be important to understand what interventions can help improve their outcomes,” Dr. Curran said.

The study was supported by a Connaught New Researcher Award from the University of Toronto. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Slomine disclosed book royalties from Cambridge University Press unrelated to this study. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

No link between childhood vaccinations and allergies or asthma

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first signs of elusive dysautonomia may appear on the skin

During the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, defined dysautonomia as an umbrella term describing conditions that result in a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system. “This encompasses both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic components of the nervous system,” said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, and chief of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston. “Clinical findings may be neurometabolic, developmental, and/or degenerative,” representing a “whole constellation of issues” that physicians may encounter in practice, she noted. Of particular interest is postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which affects between 1 million and 3 million people in the United States. Typical symptoms include lightheadedness, fainting, and a rapid increase in heartbeat after standing up from a seated position. Other conditions associated with dysautonomia include neurocardiogenic syncope and multiple system atrophy.

Dysautonomia can impact the brain, heart, mouth, blood vessels, eyes, immune cells, and bladder, as well as the skin. Patient presentations vary with symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis of dysautonomia is 7 years. “It is very difficult to put together these mysterious symptoms that patients have unless one really thinks about dysautonomia as a possible diagnosis,” Dr. Hebert said.

One of the common symptoms that she has seen in her clinical practice is joint hypermobility. “There is a known association between dysautonomia and hypermobile-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), and these patients often have hyperhidrosis,” she said. “So, keep in mind that you could see hypermobility, especially in those with EDS, with associated hyperhidrosis and dysautonomia.” Two key references that she recommends to clinicians when evaluating patients with possible dysautonomia are a study on postural tachycardia in hypermobile EDS, and an article on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in hypermobile EDS.

The Beighton Scoring System, which measures joint mobility on a 9-point scale, involves assessment of the joint mobility of the knuckle of both pinky fingers, the base of both thumbs, the elbows, knees, and spine. An instructional video on how to perform a joint hypermobility assessment is available on the Ehler-Danlos Society website.

Literature review

In March 2021, Dr. Hebert and colleagues from other medical specialties published a summary of the literature on cutaneous manifestations in dysautonomia, with an emphasis on syndromes of orthostatic intolerance. “We had neurology, cardiology, along with dermatology involved in contributing the findings they had seen in the UTHealth McGovern Dysautonomia Center of Excellence as there was a dearth of literature that taught us about the cutaneous manifestations of orthostatic intolerance syndromes,” Dr. Hebert said.

One study included in the review showed that 23 out of 26 patients with POTS had at least one of the following cutaneous manifestations: flushing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, evanescent hyperemia, livedo reticularis, erythromelalgia, and hypo- or hyperhidrosis. “If you see a patient with any of these findings, you want to think about the possibility of dysautonomia,” she said, adding that urticaria can also be a finding.

To screen for dysautonomia, she advised, “ask patients if they have difficulty sitting or standing upright, if they have indigestion or other gastric symptoms, abnormal blood vessel functioning such as low or high blood pressure, increased or decreased sweating, changes in urinary frequency or urinary incontinence, or challenges with vision.”

If the patient answers yes to two or more of these questions, she said, consider a referral to neurology and/or cardiology or a center of excellence for further evaluation with tilt-table testing and other screening tools. She also recommended a review published in 2015 that describes the dermatological manifestations of postural tachycardia syndrome and includes illustrated cases.

One of Dr. Hebert’s future dermatology residents assembled a composite of data from the Dysautonomia Center of Excellence, and in the study, found that, compared with males, females with dysautonomia suffer more from excessive sweating, paleness of the face, pale extremities, swelling, cyanosis, cold intolerance, flushing, and hot flashes.

Dr. Hebert disclosed that she has been a consultant to and an adviser for several pharmaceutical companies.