User login

‘Round Face’: A Viral Term’s Real Diagnostic Implications

“Cortisol” has become a household word, popularized by social media and tagged in videos that garnered nearly 800 million views in 2023. This is linked to the also-trending term “moon face,” which TikTok influencers and others have suggested is caused by high cortisol levels and, conversely, can be reduced through stress reduction.

“When we hear the term ‘moon face,’ we’re typically referring to Cushing syndrome [CS] or treatment with prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids,” said Anat Ben-Shlomo, MD, co-director of the Multidisciplinary Adrenal Program, Pituitary Center, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Medscape Medical News previously discussed moon face in an article detailing how to diagnose CS.

Ben-Shlomo noted that the labels “moon face” and “moon facies” should be avoided for their potentially derogatory, unprofessional-sounding connotations, and that the preferred terms are “rounded face” or “round plethoric face.”

There are several disorders that can be associated with facial roundness, not all of which relate to elevated cortisol.

“It’s important for clinicians to be able distinguish between presentations due to other pathophysiologies, identify the unique constellation of Cushing-associated signs and symptoms, engage in a differential diagnosis, and treat whatever the condition is appropriately,” Katherine Sherif, MD, professor and vice chair of academic affairs, Department of Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The Unique Presentation of CS

CS results from “prolonged elevation” in plasma cortisol levels caused by either exogenous steroid use or excess endogenous steroid production.

“The shape of the face isn’t the only feature associated with CS,” Ben-Shlomo said. “There’s central obesity, particularly in the neck, supraclavicular area, chest, and abdomen. You sometimes see a posterior cervical thoracic fat pad, colloquially — but unprofessionally — called a ‘cervical hump.’ Simultaneously, the arms and legs are getting thinner.” The development of a round, plethoric face is common in long-standing significant CS, and a reddening of the skin can appear.

Additional symptoms include hirsutism and acne. “These can also be seen in other conditions, such as PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome] but, combined with the other facial features, are more suggestive of CS,” Ben-Shlomo said.

Deep, wide purple striae appear in the trunk, breast, upper arms, and thighs, but not in the face, Ben-Shlomo advised. These appear as the fragile, thinning under-skin breaks when the patient gains weight.

Additional metabolic issues that can occur comorbidly include insulin resistance and diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, dyslipidemia, ecchymoses, increased susceptibility to infections, mood changes, cognitive dysfunction, low libido, infertility, weakness of muscles in the shoulders and thighs, episodes of bleeding and/or clotting, and an increased risk for heart attacks and strokes, Ben-Shlomo said.

“Not everyone presents with full-blown disease, but if you see any of these symptoms, be suspicious of CS and conduct a biochemical evaluation.” Three screening tests to use as a starting point are recommended by the Pituitary Society’s updated Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Cushing’s Disease. The tests should be repeated to account for intra-patient variability. If two or all three tests are positive, clinicians should be suspicious of CS and move to additional testing to identify the underlying cause, Ben-Shlomo said.

‘Subclinical’ CS

Ben-Shlomo highlighted a condition called minimal autonomous cortisol secretion (formerly “subclinical CS”). “This condition is found when a person has an adrenal nodule that produces cortisol in excess, however not to levels observed in CS. An abnormal finding on the overnight 1-mg low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST) will identify this disorder, showing mildly unsuppressed morning cortisol level, while all other tests will be within normal range.”

She described minimal autonomous cortisol secretion as a form of “smoldering CS,” which has become more commonly diagnosed. “The condition needs to be treated because the patient can develop insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and osteoporosis over time.”

Once a cause has been determined, the optimal course of action is to take a multidisciplinary approach because CS affects multiple systems.

‘Pseudo-Cushing Syndrome’

A variety of abnormalities of the hypothalamus-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis can be associated with hypercortisolemia and a rounder facial appearance but aren’t actually CS, Ben-Shlomo said.

Often called “pseudo-Cushing syndrome,” these conditions have recently been renamed “non-neoplastic hypercortisolism” or “physiologic non-neoplastic endogenous hypercortisolism.” They share some clinical and biochemical features of CS, but the hypercortisolemia is usually secondary to other factors. They increase the secretion of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone, which stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and adrenal cortisol secretion.

Identifying PCOS

PCOS is often associated with central obesity, Sherif noted, but not all women with PCOS have overweight or a central distribution of fat.

“Ask about menstrual periods and whether they come monthly,” Sherif advised. “If women using hormonal contraception say they have a regular cycle, ask if their cycle was regular prior to starting contraception. So many women with PCOS are undiagnosed because they started contraception in their teens to ‘regulate their periods’ and never realized they had PCOS.”

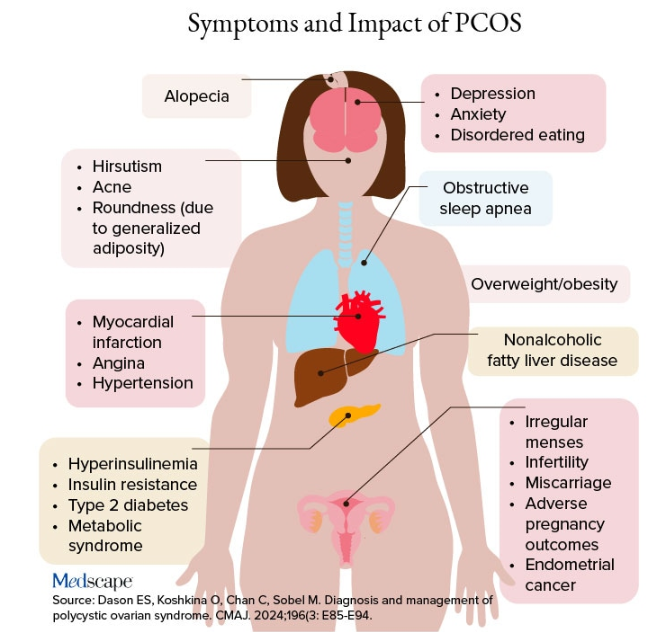

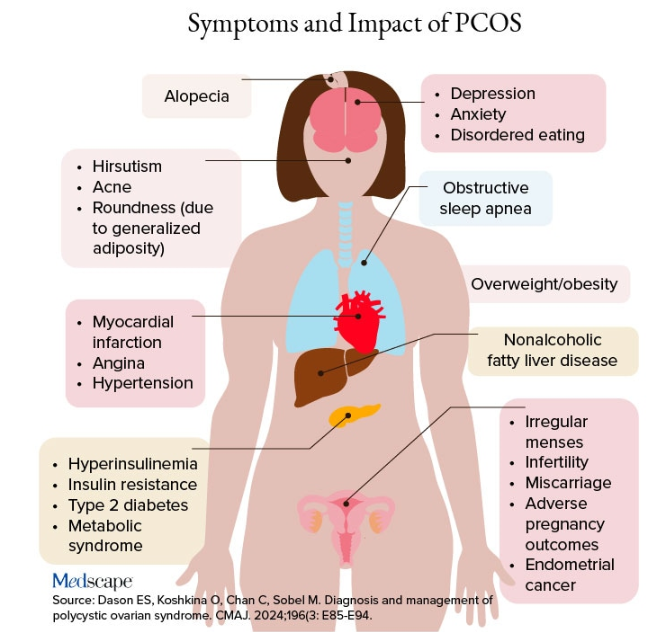

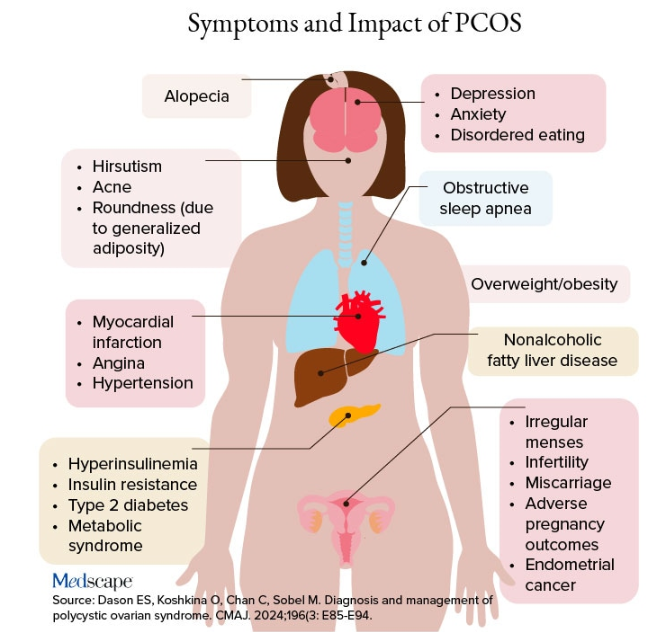

Additional symptoms of PCOS and its impact are found in the figure below.

PCOS is diagnosed when two of the following three Rotterdam criteria are met, and other diagnoses are excluded:

- Irregular menstrual cycles

- Clinical hyperandrogenism or biochemical hyperandrogenism

- Polycystic ovarian morphology on transvaginal ultrasonography or high anti-mullerian hormone (applicable only if patient is ≥ 8 years from menarche)

If PCOS is suspected, further tests can be conducted to confirm or rule out the diagnosis.

Alcohol Abuse: Alcohol abuse stimulates hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone, leading to increased ACTH levels. It’s associated with a higher fasting cortisol level, particularly at 8:30 AM or so, and attributable to impaired cortisol clearance due to alcohol-related hepatic dysfunction. The LDDST will show abnormal cortisol suppression.

Sherif advised asking patients about alcohol use, recommending treatment for alcohol use disorder, and repeating clinical and biochemical workup after patients have discontinued alcohol consumption for ≥ 1 month.

Eating Disorders Mimicking CS: Eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa, are associated with endocrine abnormalities, amenorrhea, impaired body temperature regulation, and hypercortisolism, likely due to chronic fasting-related stress. Dysregulation of the HPA axis may linger, even after weight recovery.

It’s unlikely that patients with anorexia will display the “rounded face” associated with hypercortisolism, but some research suggests that anorexia can result in a disproportionate accumulation of central adiposity after recovery from the illness.

Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with HPA axis hyperactivity, with 20%-30% of patients with MDD showing hypercortisolemia. The post-awakening cortisol surge is more pronounced in those with MDD, and about half of patients with MDD also have high evening cortisol levels, suggesting disrupted diurnal cortisol rhythms.

Some patients with MDD have greater resistance to the feedback action of glucocorticoids on HPA axis activity, with weaker sensitivity often restored by effective pharmacotherapy of the depressive condition. Neuropsychiatric disorders are also associated with reduced activity of cortisol-deactivating enzymes. Posttraumatic stress disorder and anxiety are similarly associated with hypercortisolemia.

Addressing neuropsychiatric conditions with appropriate pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy can restore cortisol levels to normal proportions.

Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolic Syndrome: Diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome can occur comorbidly with CS, and many patients with these conditions may display both a rounder face, some central adiposity, and hypercortisolemia. For example, obesity is often related to a hyperresponsive HPA axis, with elevated cortisol secretion but normal-to-low circulatory concentrations.

Obesity is associated with increased cortisol reactivity after acute physical and/or psychosocial stressors but preserved pituitary sensitivity to feedback inhibition by the LDDST. When these conditions are appropriately managed with pharmacotherapy and lifestyle changes, cortisol levels should normalize, according to the experts.

Hypothyroidism: Hypothyroidism— Hashimoto disease as well as the subclinical variety — can be associated with weight gain, which may take the form of central obesity. Some research suggests a bidirectional relationship between hypothyroidism and obesity.

“Years ago, we didn’t conduct thyroid tests very often but now they’re easy to do, so we usually catch people with hypothyroidism at the beginning of the condition,” Sherif said. “If the patient’s thyroid hasn’t been checked in a year or so, thyroid hormone testing should be conducted.”

Thyroid disease can easily be managed with the administration of thyroid hormones.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA): OSA has an impact on HPA axis activation, especially when accompanied by obesity and hypertension. A meta-analysis of 22 studies, encompassing over 600 participants, found that continuous positive airway pressure treatment in patients with OSA reduced cortisol levels as well as blood pressure.

Treatment With Exogenous Corticosteroids: Oral corticosteroid treatment is a cornerstone of therapy in transplant, rheumatic, and autoimmune diseases. The impact of chronic exposure to exogenous glucocorticoids is similar to that with endogenous glucocorticoids.

Sherif said corticosteroid treatment can cause facial roundness in as little as 2 weeks and is characteristic in people taking these agents for longer periods. Although the effects are most pronounced with oral agents, systemic effects can be associated with inhaled corticosteroids as well.

Finding alternative anti-inflammatory treatments is advisable, if possible. The co-administration of metformin might lead to improvements in both the metabolic profile and the clinical outcomes of patients receiving glucocorticoids for inflammatory conditions.

Educating Patients: “There’s much we still don’t know about hypercortisolemia and CS, including the reasons for its impact on metabolic derangement and for the accumulation of fat in particular adipose patterns,” Ben-Shlomo said. “But experienced endocrinologists do know relatively well how to diagnose the condition, distinguish it from other conditions presenting with central obesity or a rounder face, and treat it.”

Given the casual use of the terms “moon face” and “extra cortisol” on social media, it’s important for physicians to educate patients about what elevated cortisol does and doesn’t do, and design treatment strategies accordingly.

Neither Ben-Shlomo nor Sherif reported having any disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“Cortisol” has become a household word, popularized by social media and tagged in videos that garnered nearly 800 million views in 2023. This is linked to the also-trending term “moon face,” which TikTok influencers and others have suggested is caused by high cortisol levels and, conversely, can be reduced through stress reduction.

“When we hear the term ‘moon face,’ we’re typically referring to Cushing syndrome [CS] or treatment with prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids,” said Anat Ben-Shlomo, MD, co-director of the Multidisciplinary Adrenal Program, Pituitary Center, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Medscape Medical News previously discussed moon face in an article detailing how to diagnose CS.

Ben-Shlomo noted that the labels “moon face” and “moon facies” should be avoided for their potentially derogatory, unprofessional-sounding connotations, and that the preferred terms are “rounded face” or “round plethoric face.”

There are several disorders that can be associated with facial roundness, not all of which relate to elevated cortisol.

“It’s important for clinicians to be able distinguish between presentations due to other pathophysiologies, identify the unique constellation of Cushing-associated signs and symptoms, engage in a differential diagnosis, and treat whatever the condition is appropriately,” Katherine Sherif, MD, professor and vice chair of academic affairs, Department of Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The Unique Presentation of CS

CS results from “prolonged elevation” in plasma cortisol levels caused by either exogenous steroid use or excess endogenous steroid production.

“The shape of the face isn’t the only feature associated with CS,” Ben-Shlomo said. “There’s central obesity, particularly in the neck, supraclavicular area, chest, and abdomen. You sometimes see a posterior cervical thoracic fat pad, colloquially — but unprofessionally — called a ‘cervical hump.’ Simultaneously, the arms and legs are getting thinner.” The development of a round, plethoric face is common in long-standing significant CS, and a reddening of the skin can appear.

Additional symptoms include hirsutism and acne. “These can also be seen in other conditions, such as PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome] but, combined with the other facial features, are more suggestive of CS,” Ben-Shlomo said.

Deep, wide purple striae appear in the trunk, breast, upper arms, and thighs, but not in the face, Ben-Shlomo advised. These appear as the fragile, thinning under-skin breaks when the patient gains weight.

Additional metabolic issues that can occur comorbidly include insulin resistance and diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, dyslipidemia, ecchymoses, increased susceptibility to infections, mood changes, cognitive dysfunction, low libido, infertility, weakness of muscles in the shoulders and thighs, episodes of bleeding and/or clotting, and an increased risk for heart attacks and strokes, Ben-Shlomo said.

“Not everyone presents with full-blown disease, but if you see any of these symptoms, be suspicious of CS and conduct a biochemical evaluation.” Three screening tests to use as a starting point are recommended by the Pituitary Society’s updated Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Cushing’s Disease. The tests should be repeated to account for intra-patient variability. If two or all three tests are positive, clinicians should be suspicious of CS and move to additional testing to identify the underlying cause, Ben-Shlomo said.

‘Subclinical’ CS

Ben-Shlomo highlighted a condition called minimal autonomous cortisol secretion (formerly “subclinical CS”). “This condition is found when a person has an adrenal nodule that produces cortisol in excess, however not to levels observed in CS. An abnormal finding on the overnight 1-mg low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST) will identify this disorder, showing mildly unsuppressed morning cortisol level, while all other tests will be within normal range.”

She described minimal autonomous cortisol secretion as a form of “smoldering CS,” which has become more commonly diagnosed. “The condition needs to be treated because the patient can develop insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and osteoporosis over time.”

Once a cause has been determined, the optimal course of action is to take a multidisciplinary approach because CS affects multiple systems.

‘Pseudo-Cushing Syndrome’

A variety of abnormalities of the hypothalamus-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis can be associated with hypercortisolemia and a rounder facial appearance but aren’t actually CS, Ben-Shlomo said.

Often called “pseudo-Cushing syndrome,” these conditions have recently been renamed “non-neoplastic hypercortisolism” or “physiologic non-neoplastic endogenous hypercortisolism.” They share some clinical and biochemical features of CS, but the hypercortisolemia is usually secondary to other factors. They increase the secretion of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone, which stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and adrenal cortisol secretion.

Identifying PCOS

PCOS is often associated with central obesity, Sherif noted, but not all women with PCOS have overweight or a central distribution of fat.

“Ask about menstrual periods and whether they come monthly,” Sherif advised. “If women using hormonal contraception say they have a regular cycle, ask if their cycle was regular prior to starting contraception. So many women with PCOS are undiagnosed because they started contraception in their teens to ‘regulate their periods’ and never realized they had PCOS.”

Additional symptoms of PCOS and its impact are found in the figure below.

PCOS is diagnosed when two of the following three Rotterdam criteria are met, and other diagnoses are excluded:

- Irregular menstrual cycles

- Clinical hyperandrogenism or biochemical hyperandrogenism

- Polycystic ovarian morphology on transvaginal ultrasonography or high anti-mullerian hormone (applicable only if patient is ≥ 8 years from menarche)

If PCOS is suspected, further tests can be conducted to confirm or rule out the diagnosis.

Alcohol Abuse: Alcohol abuse stimulates hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone, leading to increased ACTH levels. It’s associated with a higher fasting cortisol level, particularly at 8:30 AM or so, and attributable to impaired cortisol clearance due to alcohol-related hepatic dysfunction. The LDDST will show abnormal cortisol suppression.

Sherif advised asking patients about alcohol use, recommending treatment for alcohol use disorder, and repeating clinical and biochemical workup after patients have discontinued alcohol consumption for ≥ 1 month.

Eating Disorders Mimicking CS: Eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa, are associated with endocrine abnormalities, amenorrhea, impaired body temperature regulation, and hypercortisolism, likely due to chronic fasting-related stress. Dysregulation of the HPA axis may linger, even after weight recovery.

It’s unlikely that patients with anorexia will display the “rounded face” associated with hypercortisolism, but some research suggests that anorexia can result in a disproportionate accumulation of central adiposity after recovery from the illness.

Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with HPA axis hyperactivity, with 20%-30% of patients with MDD showing hypercortisolemia. The post-awakening cortisol surge is more pronounced in those with MDD, and about half of patients with MDD also have high evening cortisol levels, suggesting disrupted diurnal cortisol rhythms.

Some patients with MDD have greater resistance to the feedback action of glucocorticoids on HPA axis activity, with weaker sensitivity often restored by effective pharmacotherapy of the depressive condition. Neuropsychiatric disorders are also associated with reduced activity of cortisol-deactivating enzymes. Posttraumatic stress disorder and anxiety are similarly associated with hypercortisolemia.

Addressing neuropsychiatric conditions with appropriate pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy can restore cortisol levels to normal proportions.

Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolic Syndrome: Diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome can occur comorbidly with CS, and many patients with these conditions may display both a rounder face, some central adiposity, and hypercortisolemia. For example, obesity is often related to a hyperresponsive HPA axis, with elevated cortisol secretion but normal-to-low circulatory concentrations.

Obesity is associated with increased cortisol reactivity after acute physical and/or psychosocial stressors but preserved pituitary sensitivity to feedback inhibition by the LDDST. When these conditions are appropriately managed with pharmacotherapy and lifestyle changes, cortisol levels should normalize, according to the experts.

Hypothyroidism: Hypothyroidism— Hashimoto disease as well as the subclinical variety — can be associated with weight gain, which may take the form of central obesity. Some research suggests a bidirectional relationship between hypothyroidism and obesity.

“Years ago, we didn’t conduct thyroid tests very often but now they’re easy to do, so we usually catch people with hypothyroidism at the beginning of the condition,” Sherif said. “If the patient’s thyroid hasn’t been checked in a year or so, thyroid hormone testing should be conducted.”

Thyroid disease can easily be managed with the administration of thyroid hormones.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA): OSA has an impact on HPA axis activation, especially when accompanied by obesity and hypertension. A meta-analysis of 22 studies, encompassing over 600 participants, found that continuous positive airway pressure treatment in patients with OSA reduced cortisol levels as well as blood pressure.

Treatment With Exogenous Corticosteroids: Oral corticosteroid treatment is a cornerstone of therapy in transplant, rheumatic, and autoimmune diseases. The impact of chronic exposure to exogenous glucocorticoids is similar to that with endogenous glucocorticoids.

Sherif said corticosteroid treatment can cause facial roundness in as little as 2 weeks and is characteristic in people taking these agents for longer periods. Although the effects are most pronounced with oral agents, systemic effects can be associated with inhaled corticosteroids as well.

Finding alternative anti-inflammatory treatments is advisable, if possible. The co-administration of metformin might lead to improvements in both the metabolic profile and the clinical outcomes of patients receiving glucocorticoids for inflammatory conditions.

Educating Patients: “There’s much we still don’t know about hypercortisolemia and CS, including the reasons for its impact on metabolic derangement and for the accumulation of fat in particular adipose patterns,” Ben-Shlomo said. “But experienced endocrinologists do know relatively well how to diagnose the condition, distinguish it from other conditions presenting with central obesity or a rounder face, and treat it.”

Given the casual use of the terms “moon face” and “extra cortisol” on social media, it’s important for physicians to educate patients about what elevated cortisol does and doesn’t do, and design treatment strategies accordingly.

Neither Ben-Shlomo nor Sherif reported having any disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

“Cortisol” has become a household word, popularized by social media and tagged in videos that garnered nearly 800 million views in 2023. This is linked to the also-trending term “moon face,” which TikTok influencers and others have suggested is caused by high cortisol levels and, conversely, can be reduced through stress reduction.

“When we hear the term ‘moon face,’ we’re typically referring to Cushing syndrome [CS] or treatment with prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids,” said Anat Ben-Shlomo, MD, co-director of the Multidisciplinary Adrenal Program, Pituitary Center, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Medscape Medical News previously discussed moon face in an article detailing how to diagnose CS.

Ben-Shlomo noted that the labels “moon face” and “moon facies” should be avoided for their potentially derogatory, unprofessional-sounding connotations, and that the preferred terms are “rounded face” or “round plethoric face.”

There are several disorders that can be associated with facial roundness, not all of which relate to elevated cortisol.

“It’s important for clinicians to be able distinguish between presentations due to other pathophysiologies, identify the unique constellation of Cushing-associated signs and symptoms, engage in a differential diagnosis, and treat whatever the condition is appropriately,” Katherine Sherif, MD, professor and vice chair of academic affairs, Department of Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

The Unique Presentation of CS

CS results from “prolonged elevation” in plasma cortisol levels caused by either exogenous steroid use or excess endogenous steroid production.

“The shape of the face isn’t the only feature associated with CS,” Ben-Shlomo said. “There’s central obesity, particularly in the neck, supraclavicular area, chest, and abdomen. You sometimes see a posterior cervical thoracic fat pad, colloquially — but unprofessionally — called a ‘cervical hump.’ Simultaneously, the arms and legs are getting thinner.” The development of a round, plethoric face is common in long-standing significant CS, and a reddening of the skin can appear.

Additional symptoms include hirsutism and acne. “These can also be seen in other conditions, such as PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome] but, combined with the other facial features, are more suggestive of CS,” Ben-Shlomo said.

Deep, wide purple striae appear in the trunk, breast, upper arms, and thighs, but not in the face, Ben-Shlomo advised. These appear as the fragile, thinning under-skin breaks when the patient gains weight.

Additional metabolic issues that can occur comorbidly include insulin resistance and diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, dyslipidemia, ecchymoses, increased susceptibility to infections, mood changes, cognitive dysfunction, low libido, infertility, weakness of muscles in the shoulders and thighs, episodes of bleeding and/or clotting, and an increased risk for heart attacks and strokes, Ben-Shlomo said.

“Not everyone presents with full-blown disease, but if you see any of these symptoms, be suspicious of CS and conduct a biochemical evaluation.” Three screening tests to use as a starting point are recommended by the Pituitary Society’s updated Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Cushing’s Disease. The tests should be repeated to account for intra-patient variability. If two or all three tests are positive, clinicians should be suspicious of CS and move to additional testing to identify the underlying cause, Ben-Shlomo said.

‘Subclinical’ CS

Ben-Shlomo highlighted a condition called minimal autonomous cortisol secretion (formerly “subclinical CS”). “This condition is found when a person has an adrenal nodule that produces cortisol in excess, however not to levels observed in CS. An abnormal finding on the overnight 1-mg low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST) will identify this disorder, showing mildly unsuppressed morning cortisol level, while all other tests will be within normal range.”

She described minimal autonomous cortisol secretion as a form of “smoldering CS,” which has become more commonly diagnosed. “The condition needs to be treated because the patient can develop insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and osteoporosis over time.”

Once a cause has been determined, the optimal course of action is to take a multidisciplinary approach because CS affects multiple systems.

‘Pseudo-Cushing Syndrome’

A variety of abnormalities of the hypothalamus-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis can be associated with hypercortisolemia and a rounder facial appearance but aren’t actually CS, Ben-Shlomo said.

Often called “pseudo-Cushing syndrome,” these conditions have recently been renamed “non-neoplastic hypercortisolism” or “physiologic non-neoplastic endogenous hypercortisolism.” They share some clinical and biochemical features of CS, but the hypercortisolemia is usually secondary to other factors. They increase the secretion of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone, which stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and adrenal cortisol secretion.

Identifying PCOS

PCOS is often associated with central obesity, Sherif noted, but not all women with PCOS have overweight or a central distribution of fat.

“Ask about menstrual periods and whether they come monthly,” Sherif advised. “If women using hormonal contraception say they have a regular cycle, ask if their cycle was regular prior to starting contraception. So many women with PCOS are undiagnosed because they started contraception in their teens to ‘regulate their periods’ and never realized they had PCOS.”

Additional symptoms of PCOS and its impact are found in the figure below.

PCOS is diagnosed when two of the following three Rotterdam criteria are met, and other diagnoses are excluded:

- Irregular menstrual cycles

- Clinical hyperandrogenism or biochemical hyperandrogenism

- Polycystic ovarian morphology on transvaginal ultrasonography or high anti-mullerian hormone (applicable only if patient is ≥ 8 years from menarche)

If PCOS is suspected, further tests can be conducted to confirm or rule out the diagnosis.

Alcohol Abuse: Alcohol abuse stimulates hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone, leading to increased ACTH levels. It’s associated with a higher fasting cortisol level, particularly at 8:30 AM or so, and attributable to impaired cortisol clearance due to alcohol-related hepatic dysfunction. The LDDST will show abnormal cortisol suppression.

Sherif advised asking patients about alcohol use, recommending treatment for alcohol use disorder, and repeating clinical and biochemical workup after patients have discontinued alcohol consumption for ≥ 1 month.

Eating Disorders Mimicking CS: Eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa, are associated with endocrine abnormalities, amenorrhea, impaired body temperature regulation, and hypercortisolism, likely due to chronic fasting-related stress. Dysregulation of the HPA axis may linger, even after weight recovery.

It’s unlikely that patients with anorexia will display the “rounded face” associated with hypercortisolism, but some research suggests that anorexia can result in a disproportionate accumulation of central adiposity after recovery from the illness.

Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with HPA axis hyperactivity, with 20%-30% of patients with MDD showing hypercortisolemia. The post-awakening cortisol surge is more pronounced in those with MDD, and about half of patients with MDD also have high evening cortisol levels, suggesting disrupted diurnal cortisol rhythms.

Some patients with MDD have greater resistance to the feedback action of glucocorticoids on HPA axis activity, with weaker sensitivity often restored by effective pharmacotherapy of the depressive condition. Neuropsychiatric disorders are also associated with reduced activity of cortisol-deactivating enzymes. Posttraumatic stress disorder and anxiety are similarly associated with hypercortisolemia.

Addressing neuropsychiatric conditions with appropriate pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy can restore cortisol levels to normal proportions.

Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolic Syndrome: Diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome can occur comorbidly with CS, and many patients with these conditions may display both a rounder face, some central adiposity, and hypercortisolemia. For example, obesity is often related to a hyperresponsive HPA axis, with elevated cortisol secretion but normal-to-low circulatory concentrations.

Obesity is associated with increased cortisol reactivity after acute physical and/or psychosocial stressors but preserved pituitary sensitivity to feedback inhibition by the LDDST. When these conditions are appropriately managed with pharmacotherapy and lifestyle changes, cortisol levels should normalize, according to the experts.

Hypothyroidism: Hypothyroidism— Hashimoto disease as well as the subclinical variety — can be associated with weight gain, which may take the form of central obesity. Some research suggests a bidirectional relationship between hypothyroidism and obesity.

“Years ago, we didn’t conduct thyroid tests very often but now they’re easy to do, so we usually catch people with hypothyroidism at the beginning of the condition,” Sherif said. “If the patient’s thyroid hasn’t been checked in a year or so, thyroid hormone testing should be conducted.”

Thyroid disease can easily be managed with the administration of thyroid hormones.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA): OSA has an impact on HPA axis activation, especially when accompanied by obesity and hypertension. A meta-analysis of 22 studies, encompassing over 600 participants, found that continuous positive airway pressure treatment in patients with OSA reduced cortisol levels as well as blood pressure.

Treatment With Exogenous Corticosteroids: Oral corticosteroid treatment is a cornerstone of therapy in transplant, rheumatic, and autoimmune diseases. The impact of chronic exposure to exogenous glucocorticoids is similar to that with endogenous glucocorticoids.

Sherif said corticosteroid treatment can cause facial roundness in as little as 2 weeks and is characteristic in people taking these agents for longer periods. Although the effects are most pronounced with oral agents, systemic effects can be associated with inhaled corticosteroids as well.

Finding alternative anti-inflammatory treatments is advisable, if possible. The co-administration of metformin might lead to improvements in both the metabolic profile and the clinical outcomes of patients receiving glucocorticoids for inflammatory conditions.

Educating Patients: “There’s much we still don’t know about hypercortisolemia and CS, including the reasons for its impact on metabolic derangement and for the accumulation of fat in particular adipose patterns,” Ben-Shlomo said. “But experienced endocrinologists do know relatively well how to diagnose the condition, distinguish it from other conditions presenting with central obesity or a rounder face, and treat it.”

Given the casual use of the terms “moon face” and “extra cortisol” on social media, it’s important for physicians to educate patients about what elevated cortisol does and doesn’t do, and design treatment strategies accordingly.

Neither Ben-Shlomo nor Sherif reported having any disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Update Coming for Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy Guidelines

CHICAGO — A preview of much-anticipated updates to guidelines on managing thyroid disease in pregnancy shows key changes to recommendations in the evolving field, ranging from consideration of the chance of spontaneous normalization of thyroid levels during pregnancy to a heightened emphasis on shared decision-making and the nuances can factor into personalized treatment.

The guidelines, expected to be published in early 2025, have not been updated since 2017, and with substantial advances and evidence from countless studies since then, the new guidelines were developed with a goal to start afresh, said ATA Thyroid and Pregnancy Guidelines Task Force cochair Tim IM Korevaar, MD, PhD, in presenting the final draft guidelines at the American Thyroid Association (ATA) 2024 Meeting.

“Obviously, we’re not going to ignore the 2017 guidelines, which have been a very good resource for us so far, but we really wanted to start from scratch and follow a ‘blank canvas’ approach in optimizing the evidence,” said Korevaar, an endocrinologist and obstetric internist with the Division of Pharmacology and Vascular Medicine & Academic Center for Thyroid Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

The guidelines, developed through a collaborative effort involving a wide variety of related medical societies, involved 14 systematic literature reviews. While the pregnancy issues covered by the guidelines is extensive, key highlights include:

Management in Preconception

Beginning with preconception, a key change in the guidelines will be that patients with euthyroid thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies, which can be indicative of thyroid dysfunction, routine treatment with levothyroxine is not recommended, based on new evidence from randomized trials of high-risk patients showing no clear benefit from the treatment.

“In these trials, and across analyses, there was absolutely no beneficial effect of levothyroxine in these patients [with euthyroid TPO antibody positivity],” he said.

With evidence showing, however, that TPO antibody positivity can lead to subclinical or overt hypothyroidism within 1 or 2 years, the guidelines will recommend that TPO antibody–positive patients do have thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels tested every 3-6 months until pregnancy, and existing recommendations to test during pregnancy among those patients remain in place, Korevaar reported.

In terms of preconception subclinical hypothyroidism, the guidelines will emphasize the existing recommendation “to always strive to reassess” thyroid levels, and if subclinical hypothyroidism does persist, to treat with low-dose levothyroxine.

During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, the new proposed recommendations will reflect the important change that three key risk factors, including age over 30 years, having at least two prior pregnancies, and morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] at least 40 kg/m2), previously considered a risk for thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy, should not, on their own, suggest the need for thyroid testing, based on low evidence of an increased risk in pregnancy.

Research on the issue includes a recent study from Korevaar’s team showing these factors to in fact have low predictability of thyroid dysfunction.

“We deemed that these risk differences weren’t really clinically meaningful (in predicting risk), and so we have removed to maternal age, BMI, and parity as risk factors for thyroid testing indications in pregnancy,” Korevaar said.

Factors considered a risk, resulting in recommended testing at presentation include a history of subclinical or clinical hypo- or hyperthyroidism, postpartum thyroiditis, known thyroid antibody positivity, symptoms of thyroid dysfunction or goiter, and other factors.

Treatment for Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

Whereas current guidelines recommend TPO antibody status in determining when to consider treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism, the new proposed guideline will instead recommend treatment based on the timing of the diagnosis of the subclinical hypothyroidism, with consideration of treatment during the first trimester, but not in the second or third trimester, based on newer evidence of the absolute risk for pregnancy complications and randomized trial data.

“The recommendations are now to no longer based on TPO antibody status, but instead according to the timing of the diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism,” Korevaar said.

Based on the collective data, “due to the low risk, we do not recommend for routine levothyroxine treatment in the second or third trimester groups with TSH levels under 10 mU/L now.”

“However, for subclinical hypothyroidism diagnosed in the first trimester, the recommendation would be that you can consider levothyroxine treatment,” he said.

While a clear indication for treatment in any trimester is the presence of overt hypothyroidism, or TSH levels over 10 mU/L, Korevaar underscored the importance of considering nuances of the recommendations that may warrant flexibility, for instance among patients with borderline TSH levels.

Spontaneous Normalization of Thyroid Levels in Pregnancy

Another new recommendation addresses the issue of spontaneous normalization of abnormal thyroid function during pregnancy, with several large studies showing a large proportion of subclinical hypothyroidism cases spontaneously revert to euthyroidism by the third trimester — despite no treatment having been provided.

Under the important proposed recommendation, retesting of subclinical hypothyroidism is suggested within 3 weeks.

“The data shows that a large proportion of patients spontaneously revert to euthyroidism,” Korevaar said.

“Upon identifying subclinical hypothyroidism in the first trimester, there will be essentially two options that clinicians can discuss with their patient — one would be to consider confirmatory tests in 3 weeks or to discuss the starting the lower dose levothyroxine in the first trimester,” he said.

In terms of overt hypothyroidism, likewise, if patients have a TSH levels below 6 mU/L in pregnancy, “you can either consider doing confirmatory testing within 3 weeks, or discussing with the patient starting levothyroxine treatment,” Korevaar added.

Overt Hyperthyroidism

For overt hyperthyroidism, no significant changes from current guidelines are being proposed, with the key exception of a heightened emphasis on the need for shared decision-making with patients, Korevaar said.

“We want to emphasize shared decision-making especially for women who have Graves’ disease prior to pregnancy, because the antithyroid treatment modalities, primarily methimazole (MMI) and propylthiouracil (PTU), have different advantages and disadvantages for an upcoming pregnancy,” he said.

“If you help a patient become involved in the decision-making process, that can also be very helpful in managing the disease and following-up on the pregnancy.”

Under the recommendations, PTU remains the preferred drug in overt hyperthyroidism, due to a more favorable profile in terms of potential birth defects vs MMI, with research showing a higher absolute risk of 3% vs 5%.

The guidelines further suggest the option of stopping the antithyroid medications upon a positive pregnancy test, with the exception of high-risk patients.

Korevaar noted that, if the treatment is stopped early in pregnancy, relapse is not likely to occur until after approximately 3 months, or 12 weeks, at which time, the high-risk teratogenic period, which is between week 5 and week 15, will have passed.

Current guidelines regarding whether to stop treatment in higher-risk hyperthyroid patients are recommended to remain unchanged.

Thyroid Nodules and Cancer

Recommendations regarding thyroid nodules and cancer during pregnancy are also expected to remain largely similar to those in the 2017 guidelines, with the exception of an emphasis on simply considering how the patient would normally be managed outside of pregnancy.

For instance, regarding the question of whether treatment can be withheld for 9 months during pregnancy. “A lot of times, the answer is yes,” Korevaar said.

Other topics that will be largely unchanged include issues of universal screening, definitions of normal and abnormal TSH and free T4 reference ranges and isolated hypothyroxinemia.

Steps Forward in Improving Updates, Readability

In addition to recommendation updates, the new guidelines are being revised to better reflect more recent evidence-based developments and user-friendliness.

“We have now made the step to a more systematic and replicable methodology to ensure for easier updates with a shorter interval,” Korevaar told this news organization.

“Furthermore, since 2006, the ATA guideline documents have followed a question-and-answer format, lacked recommendation tables and had none or only a few graphic illustrations,” he added.

“We are now further developing the typical outline of the guidelines to improve the readability and dissemination of the guideline document.”

Korevaar’s disclosures include lectureship fees from IBSA, Merck, and Berlin Chemie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO — A preview of much-anticipated updates to guidelines on managing thyroid disease in pregnancy shows key changes to recommendations in the evolving field, ranging from consideration of the chance of spontaneous normalization of thyroid levels during pregnancy to a heightened emphasis on shared decision-making and the nuances can factor into personalized treatment.

The guidelines, expected to be published in early 2025, have not been updated since 2017, and with substantial advances and evidence from countless studies since then, the new guidelines were developed with a goal to start afresh, said ATA Thyroid and Pregnancy Guidelines Task Force cochair Tim IM Korevaar, MD, PhD, in presenting the final draft guidelines at the American Thyroid Association (ATA) 2024 Meeting.

“Obviously, we’re not going to ignore the 2017 guidelines, which have been a very good resource for us so far, but we really wanted to start from scratch and follow a ‘blank canvas’ approach in optimizing the evidence,” said Korevaar, an endocrinologist and obstetric internist with the Division of Pharmacology and Vascular Medicine & Academic Center for Thyroid Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

The guidelines, developed through a collaborative effort involving a wide variety of related medical societies, involved 14 systematic literature reviews. While the pregnancy issues covered by the guidelines is extensive, key highlights include:

Management in Preconception

Beginning with preconception, a key change in the guidelines will be that patients with euthyroid thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies, which can be indicative of thyroid dysfunction, routine treatment with levothyroxine is not recommended, based on new evidence from randomized trials of high-risk patients showing no clear benefit from the treatment.

“In these trials, and across analyses, there was absolutely no beneficial effect of levothyroxine in these patients [with euthyroid TPO antibody positivity],” he said.

With evidence showing, however, that TPO antibody positivity can lead to subclinical or overt hypothyroidism within 1 or 2 years, the guidelines will recommend that TPO antibody–positive patients do have thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels tested every 3-6 months until pregnancy, and existing recommendations to test during pregnancy among those patients remain in place, Korevaar reported.

In terms of preconception subclinical hypothyroidism, the guidelines will emphasize the existing recommendation “to always strive to reassess” thyroid levels, and if subclinical hypothyroidism does persist, to treat with low-dose levothyroxine.

During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, the new proposed recommendations will reflect the important change that three key risk factors, including age over 30 years, having at least two prior pregnancies, and morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] at least 40 kg/m2), previously considered a risk for thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy, should not, on their own, suggest the need for thyroid testing, based on low evidence of an increased risk in pregnancy.

Research on the issue includes a recent study from Korevaar’s team showing these factors to in fact have low predictability of thyroid dysfunction.

“We deemed that these risk differences weren’t really clinically meaningful (in predicting risk), and so we have removed to maternal age, BMI, and parity as risk factors for thyroid testing indications in pregnancy,” Korevaar said.

Factors considered a risk, resulting in recommended testing at presentation include a history of subclinical or clinical hypo- or hyperthyroidism, postpartum thyroiditis, known thyroid antibody positivity, symptoms of thyroid dysfunction or goiter, and other factors.

Treatment for Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

Whereas current guidelines recommend TPO antibody status in determining when to consider treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism, the new proposed guideline will instead recommend treatment based on the timing of the diagnosis of the subclinical hypothyroidism, with consideration of treatment during the first trimester, but not in the second or third trimester, based on newer evidence of the absolute risk for pregnancy complications and randomized trial data.

“The recommendations are now to no longer based on TPO antibody status, but instead according to the timing of the diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism,” Korevaar said.

Based on the collective data, “due to the low risk, we do not recommend for routine levothyroxine treatment in the second or third trimester groups with TSH levels under 10 mU/L now.”

“However, for subclinical hypothyroidism diagnosed in the first trimester, the recommendation would be that you can consider levothyroxine treatment,” he said.

While a clear indication for treatment in any trimester is the presence of overt hypothyroidism, or TSH levels over 10 mU/L, Korevaar underscored the importance of considering nuances of the recommendations that may warrant flexibility, for instance among patients with borderline TSH levels.

Spontaneous Normalization of Thyroid Levels in Pregnancy

Another new recommendation addresses the issue of spontaneous normalization of abnormal thyroid function during pregnancy, with several large studies showing a large proportion of subclinical hypothyroidism cases spontaneously revert to euthyroidism by the third trimester — despite no treatment having been provided.

Under the important proposed recommendation, retesting of subclinical hypothyroidism is suggested within 3 weeks.

“The data shows that a large proportion of patients spontaneously revert to euthyroidism,” Korevaar said.

“Upon identifying subclinical hypothyroidism in the first trimester, there will be essentially two options that clinicians can discuss with their patient — one would be to consider confirmatory tests in 3 weeks or to discuss the starting the lower dose levothyroxine in the first trimester,” he said.

In terms of overt hypothyroidism, likewise, if patients have a TSH levels below 6 mU/L in pregnancy, “you can either consider doing confirmatory testing within 3 weeks, or discussing with the patient starting levothyroxine treatment,” Korevaar added.

Overt Hyperthyroidism

For overt hyperthyroidism, no significant changes from current guidelines are being proposed, with the key exception of a heightened emphasis on the need for shared decision-making with patients, Korevaar said.

“We want to emphasize shared decision-making especially for women who have Graves’ disease prior to pregnancy, because the antithyroid treatment modalities, primarily methimazole (MMI) and propylthiouracil (PTU), have different advantages and disadvantages for an upcoming pregnancy,” he said.

“If you help a patient become involved in the decision-making process, that can also be very helpful in managing the disease and following-up on the pregnancy.”

Under the recommendations, PTU remains the preferred drug in overt hyperthyroidism, due to a more favorable profile in terms of potential birth defects vs MMI, with research showing a higher absolute risk of 3% vs 5%.

The guidelines further suggest the option of stopping the antithyroid medications upon a positive pregnancy test, with the exception of high-risk patients.

Korevaar noted that, if the treatment is stopped early in pregnancy, relapse is not likely to occur until after approximately 3 months, or 12 weeks, at which time, the high-risk teratogenic period, which is between week 5 and week 15, will have passed.

Current guidelines regarding whether to stop treatment in higher-risk hyperthyroid patients are recommended to remain unchanged.

Thyroid Nodules and Cancer

Recommendations regarding thyroid nodules and cancer during pregnancy are also expected to remain largely similar to those in the 2017 guidelines, with the exception of an emphasis on simply considering how the patient would normally be managed outside of pregnancy.

For instance, regarding the question of whether treatment can be withheld for 9 months during pregnancy. “A lot of times, the answer is yes,” Korevaar said.

Other topics that will be largely unchanged include issues of universal screening, definitions of normal and abnormal TSH and free T4 reference ranges and isolated hypothyroxinemia.

Steps Forward in Improving Updates, Readability

In addition to recommendation updates, the new guidelines are being revised to better reflect more recent evidence-based developments and user-friendliness.

“We have now made the step to a more systematic and replicable methodology to ensure for easier updates with a shorter interval,” Korevaar told this news organization.

“Furthermore, since 2006, the ATA guideline documents have followed a question-and-answer format, lacked recommendation tables and had none or only a few graphic illustrations,” he added.

“We are now further developing the typical outline of the guidelines to improve the readability and dissemination of the guideline document.”

Korevaar’s disclosures include lectureship fees from IBSA, Merck, and Berlin Chemie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO — A preview of much-anticipated updates to guidelines on managing thyroid disease in pregnancy shows key changes to recommendations in the evolving field, ranging from consideration of the chance of spontaneous normalization of thyroid levels during pregnancy to a heightened emphasis on shared decision-making and the nuances can factor into personalized treatment.

The guidelines, expected to be published in early 2025, have not been updated since 2017, and with substantial advances and evidence from countless studies since then, the new guidelines were developed with a goal to start afresh, said ATA Thyroid and Pregnancy Guidelines Task Force cochair Tim IM Korevaar, MD, PhD, in presenting the final draft guidelines at the American Thyroid Association (ATA) 2024 Meeting.

“Obviously, we’re not going to ignore the 2017 guidelines, which have been a very good resource for us so far, but we really wanted to start from scratch and follow a ‘blank canvas’ approach in optimizing the evidence,” said Korevaar, an endocrinologist and obstetric internist with the Division of Pharmacology and Vascular Medicine & Academic Center for Thyroid Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

The guidelines, developed through a collaborative effort involving a wide variety of related medical societies, involved 14 systematic literature reviews. While the pregnancy issues covered by the guidelines is extensive, key highlights include:

Management in Preconception

Beginning with preconception, a key change in the guidelines will be that patients with euthyroid thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies, which can be indicative of thyroid dysfunction, routine treatment with levothyroxine is not recommended, based on new evidence from randomized trials of high-risk patients showing no clear benefit from the treatment.

“In these trials, and across analyses, there was absolutely no beneficial effect of levothyroxine in these patients [with euthyroid TPO antibody positivity],” he said.

With evidence showing, however, that TPO antibody positivity can lead to subclinical or overt hypothyroidism within 1 or 2 years, the guidelines will recommend that TPO antibody–positive patients do have thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels tested every 3-6 months until pregnancy, and existing recommendations to test during pregnancy among those patients remain in place, Korevaar reported.

In terms of preconception subclinical hypothyroidism, the guidelines will emphasize the existing recommendation “to always strive to reassess” thyroid levels, and if subclinical hypothyroidism does persist, to treat with low-dose levothyroxine.

During Pregnancy

During pregnancy, the new proposed recommendations will reflect the important change that three key risk factors, including age over 30 years, having at least two prior pregnancies, and morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] at least 40 kg/m2), previously considered a risk for thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy, should not, on their own, suggest the need for thyroid testing, based on low evidence of an increased risk in pregnancy.

Research on the issue includes a recent study from Korevaar’s team showing these factors to in fact have low predictability of thyroid dysfunction.

“We deemed that these risk differences weren’t really clinically meaningful (in predicting risk), and so we have removed to maternal age, BMI, and parity as risk factors for thyroid testing indications in pregnancy,” Korevaar said.

Factors considered a risk, resulting in recommended testing at presentation include a history of subclinical or clinical hypo- or hyperthyroidism, postpartum thyroiditis, known thyroid antibody positivity, symptoms of thyroid dysfunction or goiter, and other factors.

Treatment for Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

Whereas current guidelines recommend TPO antibody status in determining when to consider treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism, the new proposed guideline will instead recommend treatment based on the timing of the diagnosis of the subclinical hypothyroidism, with consideration of treatment during the first trimester, but not in the second or third trimester, based on newer evidence of the absolute risk for pregnancy complications and randomized trial data.

“The recommendations are now to no longer based on TPO antibody status, but instead according to the timing of the diagnosis of subclinical hypothyroidism,” Korevaar said.

Based on the collective data, “due to the low risk, we do not recommend for routine levothyroxine treatment in the second or third trimester groups with TSH levels under 10 mU/L now.”

“However, for subclinical hypothyroidism diagnosed in the first trimester, the recommendation would be that you can consider levothyroxine treatment,” he said.

While a clear indication for treatment in any trimester is the presence of overt hypothyroidism, or TSH levels over 10 mU/L, Korevaar underscored the importance of considering nuances of the recommendations that may warrant flexibility, for instance among patients with borderline TSH levels.

Spontaneous Normalization of Thyroid Levels in Pregnancy

Another new recommendation addresses the issue of spontaneous normalization of abnormal thyroid function during pregnancy, with several large studies showing a large proportion of subclinical hypothyroidism cases spontaneously revert to euthyroidism by the third trimester — despite no treatment having been provided.

Under the important proposed recommendation, retesting of subclinical hypothyroidism is suggested within 3 weeks.

“The data shows that a large proportion of patients spontaneously revert to euthyroidism,” Korevaar said.

“Upon identifying subclinical hypothyroidism in the first trimester, there will be essentially two options that clinicians can discuss with their patient — one would be to consider confirmatory tests in 3 weeks or to discuss the starting the lower dose levothyroxine in the first trimester,” he said.

In terms of overt hypothyroidism, likewise, if patients have a TSH levels below 6 mU/L in pregnancy, “you can either consider doing confirmatory testing within 3 weeks, or discussing with the patient starting levothyroxine treatment,” Korevaar added.

Overt Hyperthyroidism

For overt hyperthyroidism, no significant changes from current guidelines are being proposed, with the key exception of a heightened emphasis on the need for shared decision-making with patients, Korevaar said.

“We want to emphasize shared decision-making especially for women who have Graves’ disease prior to pregnancy, because the antithyroid treatment modalities, primarily methimazole (MMI) and propylthiouracil (PTU), have different advantages and disadvantages for an upcoming pregnancy,” he said.

“If you help a patient become involved in the decision-making process, that can also be very helpful in managing the disease and following-up on the pregnancy.”

Under the recommendations, PTU remains the preferred drug in overt hyperthyroidism, due to a more favorable profile in terms of potential birth defects vs MMI, with research showing a higher absolute risk of 3% vs 5%.

The guidelines further suggest the option of stopping the antithyroid medications upon a positive pregnancy test, with the exception of high-risk patients.

Korevaar noted that, if the treatment is stopped early in pregnancy, relapse is not likely to occur until after approximately 3 months, or 12 weeks, at which time, the high-risk teratogenic period, which is between week 5 and week 15, will have passed.

Current guidelines regarding whether to stop treatment in higher-risk hyperthyroid patients are recommended to remain unchanged.

Thyroid Nodules and Cancer

Recommendations regarding thyroid nodules and cancer during pregnancy are also expected to remain largely similar to those in the 2017 guidelines, with the exception of an emphasis on simply considering how the patient would normally be managed outside of pregnancy.

For instance, regarding the question of whether treatment can be withheld for 9 months during pregnancy. “A lot of times, the answer is yes,” Korevaar said.

Other topics that will be largely unchanged include issues of universal screening, definitions of normal and abnormal TSH and free T4 reference ranges and isolated hypothyroxinemia.

Steps Forward in Improving Updates, Readability

In addition to recommendation updates, the new guidelines are being revised to better reflect more recent evidence-based developments and user-friendliness.

“We have now made the step to a more systematic and replicable methodology to ensure for easier updates with a shorter interval,” Korevaar told this news organization.

“Furthermore, since 2006, the ATA guideline documents have followed a question-and-answer format, lacked recommendation tables and had none or only a few graphic illustrations,” he added.

“We are now further developing the typical outline of the guidelines to improve the readability and dissemination of the guideline document.”

Korevaar’s disclosures include lectureship fees from IBSA, Merck, and Berlin Chemie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ATA 2024

Many Patients With Cancer Visit EDs Before Diagnosis

Researchers examined Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) data that had been gathered from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2021. The study focused on patients aged 18 years or older with confirmed primary cancer diagnoses.

Factors associated with an increased likelihood of an ED visit ahead of diagnosis included having certain cancers, living in rural areas, and having less access to primary care, according to study author Keerat Grewal, MD, an emergency physician and clinician scientist at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute at Sinai Health in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and coauthors.

“The ED is a distressing environment for patients to receive a possible cancer diagnosis,” the authors wrote. “Moreover, it is frequently ill equipped to provide ongoing continuity of care, which can lead patients down a poorly defined diagnostic pathway before receiving a confirmed diagnosis based on tissue and a subsequent treatment plan.”

The findings were published online on November 4 in CMAJ).

Neurologic Cancers Prominent

In an interview, Grewal said in an interview that the study reflects her desire as an emergency room physician to understand why so many patients with cancer get the initial reports about their disease from clinicians whom they often have just met for the first time.

Among patients with an ED visit before cancer diagnosis, 51.4% were admitted to hospital from the most recent visit.

Compared with patients with a family physician on whom they could rely for routine care, those who had no outpatient visits (odds ratio [OR], 2.09) or fewer than three outpatient visits (OR, 1.41) in the 6-30 months before cancer diagnosis were more likely to have an ED visit before their cancer diagnosis.

Other factors associated with increased odds of ED use before cancer diagnosis included rurality (OR, 1.15), residence in northern Ontario (northeast region: OR, 1.14 and northwest region: OR, 1.27 vs Toronto region), and living in the most marginalized areas (material resource deprivation: OR, 1.37 and housing stability: OR, 1.09 vs least marginalized area).

The researchers also found that patients with certain cancers were more likely to have sought care in the ED. They compared these cancers with breast cancer, which is often detected through screening.

“Patients with neurologic cancers had extremely high odds of ED use before cancer diagnosis,” the authors wrote. “This is likely because of the emergent nature of presentation, with acute neurologic symptoms such as weakness, confusion, or seizures, which require urgent assessment.” On the other hand, pancreatic, liver, or thoracic cancer can trigger nonspecific symptoms that may be ignored until they reach a crisis level that prompts an ED visit.

The limitations of the study included its inability to identify cancer-related ED visits and its narrow focus on patients in Ontario, according to the researchers. But the use of the ICES databases also allowed researchers access to a broader pool of data than are available in many other cases.

The findings in the new paper echo those of previous research, the authors noted. Research in the United Kingdom found that 24%-31% of cancer diagnoses involved the ED. In addition, a study of people enrolled in the US Medicare program, which serves patients aged 65 years or older, found that 23% were seen in the ED in the 30 days before diagnosis.

‘Unpacking the Data’

The current findings also are consistent with those of an International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership study that was published in 2022 in The Lancet Oncology, said Erika Nicholson, MHS, vice president of cancer systems and innovation at the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. The latter study analyzed cancer registration and linked hospital admissions data from 14 jurisdictions in Australia, Canada, Denmark, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

“We see similar trends in terms of people visiting EDs and being diagnosed through EDs internationally,” Nicholson said. “We’re working with partners to put in place different strategies to address the challenges” that this phenomenon presents in terms of improving screening and follow-up care.

“Cancer is not one disease, but many diseases,” she said. “They present differently. We’re focused on really unpacking the data and understanding them.”

All this research highlights the need for more services and personnel to address cancer, including people who are trained to help patients cope after getting concerning news through emergency care, she said.

“That means having a system that fully supports you and helps you navigate through that diagnostic process,” Nicholson said. Addressing the added challenges for patients who don’t have secure housing is a special need, she added.

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Grewal reported receiving grants from CIHR and the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. Nicholson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers examined Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) data that had been gathered from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2021. The study focused on patients aged 18 years or older with confirmed primary cancer diagnoses.

Factors associated with an increased likelihood of an ED visit ahead of diagnosis included having certain cancers, living in rural areas, and having less access to primary care, according to study author Keerat Grewal, MD, an emergency physician and clinician scientist at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute at Sinai Health in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and coauthors.

“The ED is a distressing environment for patients to receive a possible cancer diagnosis,” the authors wrote. “Moreover, it is frequently ill equipped to provide ongoing continuity of care, which can lead patients down a poorly defined diagnostic pathway before receiving a confirmed diagnosis based on tissue and a subsequent treatment plan.”

The findings were published online on November 4 in CMAJ).

Neurologic Cancers Prominent

In an interview, Grewal said in an interview that the study reflects her desire as an emergency room physician to understand why so many patients with cancer get the initial reports about their disease from clinicians whom they often have just met for the first time.

Among patients with an ED visit before cancer diagnosis, 51.4% were admitted to hospital from the most recent visit.

Compared with patients with a family physician on whom they could rely for routine care, those who had no outpatient visits (odds ratio [OR], 2.09) or fewer than three outpatient visits (OR, 1.41) in the 6-30 months before cancer diagnosis were more likely to have an ED visit before their cancer diagnosis.

Other factors associated with increased odds of ED use before cancer diagnosis included rurality (OR, 1.15), residence in northern Ontario (northeast region: OR, 1.14 and northwest region: OR, 1.27 vs Toronto region), and living in the most marginalized areas (material resource deprivation: OR, 1.37 and housing stability: OR, 1.09 vs least marginalized area).

The researchers also found that patients with certain cancers were more likely to have sought care in the ED. They compared these cancers with breast cancer, which is often detected through screening.

“Patients with neurologic cancers had extremely high odds of ED use before cancer diagnosis,” the authors wrote. “This is likely because of the emergent nature of presentation, with acute neurologic symptoms such as weakness, confusion, or seizures, which require urgent assessment.” On the other hand, pancreatic, liver, or thoracic cancer can trigger nonspecific symptoms that may be ignored until they reach a crisis level that prompts an ED visit.

The limitations of the study included its inability to identify cancer-related ED visits and its narrow focus on patients in Ontario, according to the researchers. But the use of the ICES databases also allowed researchers access to a broader pool of data than are available in many other cases.

The findings in the new paper echo those of previous research, the authors noted. Research in the United Kingdom found that 24%-31% of cancer diagnoses involved the ED. In addition, a study of people enrolled in the US Medicare program, which serves patients aged 65 years or older, found that 23% were seen in the ED in the 30 days before diagnosis.

‘Unpacking the Data’

The current findings also are consistent with those of an International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership study that was published in 2022 in The Lancet Oncology, said Erika Nicholson, MHS, vice president of cancer systems and innovation at the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. The latter study analyzed cancer registration and linked hospital admissions data from 14 jurisdictions in Australia, Canada, Denmark, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

“We see similar trends in terms of people visiting EDs and being diagnosed through EDs internationally,” Nicholson said. “We’re working with partners to put in place different strategies to address the challenges” that this phenomenon presents in terms of improving screening and follow-up care.

“Cancer is not one disease, but many diseases,” she said. “They present differently. We’re focused on really unpacking the data and understanding them.”

All this research highlights the need for more services and personnel to address cancer, including people who are trained to help patients cope after getting concerning news through emergency care, she said.

“That means having a system that fully supports you and helps you navigate through that diagnostic process,” Nicholson said. Addressing the added challenges for patients who don’t have secure housing is a special need, she added.

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Grewal reported receiving grants from CIHR and the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. Nicholson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers examined Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) data that had been gathered from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2021. The study focused on patients aged 18 years or older with confirmed primary cancer diagnoses.

Factors associated with an increased likelihood of an ED visit ahead of diagnosis included having certain cancers, living in rural areas, and having less access to primary care, according to study author Keerat Grewal, MD, an emergency physician and clinician scientist at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute at Sinai Health in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and coauthors.

“The ED is a distressing environment for patients to receive a possible cancer diagnosis,” the authors wrote. “Moreover, it is frequently ill equipped to provide ongoing continuity of care, which can lead patients down a poorly defined diagnostic pathway before receiving a confirmed diagnosis based on tissue and a subsequent treatment plan.”

The findings were published online on November 4 in CMAJ).

Neurologic Cancers Prominent

In an interview, Grewal said in an interview that the study reflects her desire as an emergency room physician to understand why so many patients with cancer get the initial reports about their disease from clinicians whom they often have just met for the first time.

Among patients with an ED visit before cancer diagnosis, 51.4% were admitted to hospital from the most recent visit.

Compared with patients with a family physician on whom they could rely for routine care, those who had no outpatient visits (odds ratio [OR], 2.09) or fewer than three outpatient visits (OR, 1.41) in the 6-30 months before cancer diagnosis were more likely to have an ED visit before their cancer diagnosis.

Other factors associated with increased odds of ED use before cancer diagnosis included rurality (OR, 1.15), residence in northern Ontario (northeast region: OR, 1.14 and northwest region: OR, 1.27 vs Toronto region), and living in the most marginalized areas (material resource deprivation: OR, 1.37 and housing stability: OR, 1.09 vs least marginalized area).

The researchers also found that patients with certain cancers were more likely to have sought care in the ED. They compared these cancers with breast cancer, which is often detected through screening.

“Patients with neurologic cancers had extremely high odds of ED use before cancer diagnosis,” the authors wrote. “This is likely because of the emergent nature of presentation, with acute neurologic symptoms such as weakness, confusion, or seizures, which require urgent assessment.” On the other hand, pancreatic, liver, or thoracic cancer can trigger nonspecific symptoms that may be ignored until they reach a crisis level that prompts an ED visit.

The limitations of the study included its inability to identify cancer-related ED visits and its narrow focus on patients in Ontario, according to the researchers. But the use of the ICES databases also allowed researchers access to a broader pool of data than are available in many other cases.

The findings in the new paper echo those of previous research, the authors noted. Research in the United Kingdom found that 24%-31% of cancer diagnoses involved the ED. In addition, a study of people enrolled in the US Medicare program, which serves patients aged 65 years or older, found that 23% were seen in the ED in the 30 days before diagnosis.

‘Unpacking the Data’

The current findings also are consistent with those of an International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership study that was published in 2022 in The Lancet Oncology, said Erika Nicholson, MHS, vice president of cancer systems and innovation at the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. The latter study analyzed cancer registration and linked hospital admissions data from 14 jurisdictions in Australia, Canada, Denmark, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

“We see similar trends in terms of people visiting EDs and being diagnosed through EDs internationally,” Nicholson said. “We’re working with partners to put in place different strategies to address the challenges” that this phenomenon presents in terms of improving screening and follow-up care.

“Cancer is not one disease, but many diseases,” she said. “They present differently. We’re focused on really unpacking the data and understanding them.”

All this research highlights the need for more services and personnel to address cancer, including people who are trained to help patients cope after getting concerning news through emergency care, she said.

“That means having a system that fully supports you and helps you navigate through that diagnostic process,” Nicholson said. Addressing the added challenges for patients who don’t have secure housing is a special need, she added.

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Grewal reported receiving grants from CIHR and the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. Nicholson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CMAJ

ATA: Updates on Risk, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Thyroid Cancer

The study, presented by Juan Brito Campana, MBBS, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, used Medicare records to perform a secondary analysis of 41,000 adults with type 2 diabetes and moderate cardiovascular risk who were new users of GLP-1 receptor agonists, compared to users of other diabetes medications.

“We took the innovative approach of applying the methodological rigor of a randomized clinical trial to the very large dataset of observational studies,” said Brito Campana.