User login

Pulmonary embolism confers higher mortality long term

Topline

Long-term mortality rates among individuals who have had a pulmonary embolism are significantly higher than rates in the general population.

Methodology

Researchers investigated long-term outcomes of patients with pulmonary embolism in a single-center registry.

They followed 896 patients for up to 14 years.

Data were from consecutive cases treated between May 2005 and December 2017.

Takeaway

The total follow-up time was 3,908 patient-years (median, 3.1 years).

One-year and five-year mortality rates were 19.7% (95% confidence interval, 17.2%-22.4%) and 37.1% (95% CI, 33.6%-40.5%), respectively, for patients with pulmonary embolism.

The most frequent causes of death were cancer (28.5%), pulmonary embolism (19.4%), infections (13.9%), and cardiovascular events (11.6%).

Late mortality (>30 days) was more frequent than in the general population for patients with cancer (5-year standardized mortality ratio, 2.77; 95% CI, 2.41-3.16) and for patients without cancer (1.80; 95% CI, 1.50-2.14), compared with expected rates.

In practice

stated Johannes Eckelt, Clinic of Cardiology and Pneumology, University Medical Center Göttingen (Germany).

Source

“Long-term Mortality in Pulmonary Embolism: Results in a Single-Center Registry,” by Mr. Eckelt and colleagues was published in Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

Limitations

Owing to the single-center study design, selection bias cannot be excluded, limiting the generalizability of the study findings, the authors stated.

Disclosures

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Topline

Long-term mortality rates among individuals who have had a pulmonary embolism are significantly higher than rates in the general population.

Methodology

Researchers investigated long-term outcomes of patients with pulmonary embolism in a single-center registry.

They followed 896 patients for up to 14 years.

Data were from consecutive cases treated between May 2005 and December 2017.

Takeaway

The total follow-up time was 3,908 patient-years (median, 3.1 years).

One-year and five-year mortality rates were 19.7% (95% confidence interval, 17.2%-22.4%) and 37.1% (95% CI, 33.6%-40.5%), respectively, for patients with pulmonary embolism.

The most frequent causes of death were cancer (28.5%), pulmonary embolism (19.4%), infections (13.9%), and cardiovascular events (11.6%).

Late mortality (>30 days) was more frequent than in the general population for patients with cancer (5-year standardized mortality ratio, 2.77; 95% CI, 2.41-3.16) and for patients without cancer (1.80; 95% CI, 1.50-2.14), compared with expected rates.

In practice

stated Johannes Eckelt, Clinic of Cardiology and Pneumology, University Medical Center Göttingen (Germany).

Source

“Long-term Mortality in Pulmonary Embolism: Results in a Single-Center Registry,” by Mr. Eckelt and colleagues was published in Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

Limitations

Owing to the single-center study design, selection bias cannot be excluded, limiting the generalizability of the study findings, the authors stated.

Disclosures

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Topline

Long-term mortality rates among individuals who have had a pulmonary embolism are significantly higher than rates in the general population.

Methodology

Researchers investigated long-term outcomes of patients with pulmonary embolism in a single-center registry.

They followed 896 patients for up to 14 years.

Data were from consecutive cases treated between May 2005 and December 2017.

Takeaway

The total follow-up time was 3,908 patient-years (median, 3.1 years).

One-year and five-year mortality rates were 19.7% (95% confidence interval, 17.2%-22.4%) and 37.1% (95% CI, 33.6%-40.5%), respectively, for patients with pulmonary embolism.

The most frequent causes of death were cancer (28.5%), pulmonary embolism (19.4%), infections (13.9%), and cardiovascular events (11.6%).

Late mortality (>30 days) was more frequent than in the general population for patients with cancer (5-year standardized mortality ratio, 2.77; 95% CI, 2.41-3.16) and for patients without cancer (1.80; 95% CI, 1.50-2.14), compared with expected rates.

In practice

stated Johannes Eckelt, Clinic of Cardiology and Pneumology, University Medical Center Göttingen (Germany).

Source

“Long-term Mortality in Pulmonary Embolism: Results in a Single-Center Registry,” by Mr. Eckelt and colleagues was published in Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

Limitations

Owing to the single-center study design, selection bias cannot be excluded, limiting the generalizability of the study findings, the authors stated.

Disclosures

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Comorbid respiratory disease key predictor of NTM-PD

(NTM-PD), data from a systematic review of 99 studies indicate.

NTM-PD is frequently underdiagnosed, and data on specific risk factors are lacking, especially for high-risk individuals with preexisting respiratory diseases, wrote Michael R. Loebinger, PhD, of Imperial College London, and colleagues.

“NTM-PD can be a substantial burden for patients, contributing to lung function decline and reduced health-related quality of life, and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality,” they said.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers identified 99 studies published between 2011 and 2021. Of these, 24 reported an association between risk factors and NTM-PD among patients with respiratory disease compared with patients without NTM-PD and with healthy control persons without NTM-PD; these studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Overall, comorbid respiratory disease was significantly associated with an increased risk of NTM-PD, with odds ratios ranging from 4.15 for asthma to 21.43 for bronchiectasis. Other conditions significantly associated with NTM-PD risk included history of tuberculosis (odds ratio, 12.69), interstitial lung disease (OR, 6.39), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (OR, 6.63).

Other factors associated with increased NTM-PD risk included inhaled corticosteroids (OR, 4.46), oral corticosteroids (OR, 3.37), and other immunosuppressants (OR, 2.60). Additional risk factors were use of anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha for rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.13), solid tumors (OR, 4.66), current pneumonia (OR, 5.54), cardiovascular disease (OR, 1.73), and low body mass index (OR, 3.04).

Additional marginal or nonsignificant associations with NTM-PD risk were found for lung function, diabetes, renal disease, cancer, healthy weight, and infection with either Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus.

Possible protective factors, though not significant, included increasing or high BMI and long-term macrolide use.

Bronchiectasis, which is associated with the highest risk of NTM-PD, was assessed in four studies. It was evaluated less frequently because it was often considered a reason for study exclusion, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“However, many studies report high numbers of patients with nodular bronchiectatic NTM-PD and is suggested to be almost universal in patients with noncavitary NTM-PD,” they said.

The most common risk factors for NTM-PD in the included studies were the use of immunosuppressants, female sex, COPD comorbidity, and history of suspected tuberculosis.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the high level of heterogeneity among the included studies, the lack of data on attributable risk, and inconsistent definitions of NTM-PD, the researchers noted. However, the results may be useful for highlighting risk factors that could be used to identify high-risk patients and to promote early diagnosis and treatment, they said. In addition, long-term studies are needed regarding the impact of multiple potential risk factors on individual risk for NTM-PD among patients with respiratory disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by Insmed BV. Dr. Loebinger has relationships with Insmed, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Savara, Parion, Zambon, 30T, Electromed, Recode, AN2 Therapeutics, and Armata.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(NTM-PD), data from a systematic review of 99 studies indicate.

NTM-PD is frequently underdiagnosed, and data on specific risk factors are lacking, especially for high-risk individuals with preexisting respiratory diseases, wrote Michael R. Loebinger, PhD, of Imperial College London, and colleagues.

“NTM-PD can be a substantial burden for patients, contributing to lung function decline and reduced health-related quality of life, and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality,” they said.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers identified 99 studies published between 2011 and 2021. Of these, 24 reported an association between risk factors and NTM-PD among patients with respiratory disease compared with patients without NTM-PD and with healthy control persons without NTM-PD; these studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Overall, comorbid respiratory disease was significantly associated with an increased risk of NTM-PD, with odds ratios ranging from 4.15 for asthma to 21.43 for bronchiectasis. Other conditions significantly associated with NTM-PD risk included history of tuberculosis (odds ratio, 12.69), interstitial lung disease (OR, 6.39), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (OR, 6.63).

Other factors associated with increased NTM-PD risk included inhaled corticosteroids (OR, 4.46), oral corticosteroids (OR, 3.37), and other immunosuppressants (OR, 2.60). Additional risk factors were use of anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha for rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.13), solid tumors (OR, 4.66), current pneumonia (OR, 5.54), cardiovascular disease (OR, 1.73), and low body mass index (OR, 3.04).

Additional marginal or nonsignificant associations with NTM-PD risk were found for lung function, diabetes, renal disease, cancer, healthy weight, and infection with either Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus.

Possible protective factors, though not significant, included increasing or high BMI and long-term macrolide use.

Bronchiectasis, which is associated with the highest risk of NTM-PD, was assessed in four studies. It was evaluated less frequently because it was often considered a reason for study exclusion, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“However, many studies report high numbers of patients with nodular bronchiectatic NTM-PD and is suggested to be almost universal in patients with noncavitary NTM-PD,” they said.

The most common risk factors for NTM-PD in the included studies were the use of immunosuppressants, female sex, COPD comorbidity, and history of suspected tuberculosis.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the high level of heterogeneity among the included studies, the lack of data on attributable risk, and inconsistent definitions of NTM-PD, the researchers noted. However, the results may be useful for highlighting risk factors that could be used to identify high-risk patients and to promote early diagnosis and treatment, they said. In addition, long-term studies are needed regarding the impact of multiple potential risk factors on individual risk for NTM-PD among patients with respiratory disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by Insmed BV. Dr. Loebinger has relationships with Insmed, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Savara, Parion, Zambon, 30T, Electromed, Recode, AN2 Therapeutics, and Armata.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(NTM-PD), data from a systematic review of 99 studies indicate.

NTM-PD is frequently underdiagnosed, and data on specific risk factors are lacking, especially for high-risk individuals with preexisting respiratory diseases, wrote Michael R. Loebinger, PhD, of Imperial College London, and colleagues.

“NTM-PD can be a substantial burden for patients, contributing to lung function decline and reduced health-related quality of life, and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality,” they said.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers identified 99 studies published between 2011 and 2021. Of these, 24 reported an association between risk factors and NTM-PD among patients with respiratory disease compared with patients without NTM-PD and with healthy control persons without NTM-PD; these studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Overall, comorbid respiratory disease was significantly associated with an increased risk of NTM-PD, with odds ratios ranging from 4.15 for asthma to 21.43 for bronchiectasis. Other conditions significantly associated with NTM-PD risk included history of tuberculosis (odds ratio, 12.69), interstitial lung disease (OR, 6.39), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (OR, 6.63).

Other factors associated with increased NTM-PD risk included inhaled corticosteroids (OR, 4.46), oral corticosteroids (OR, 3.37), and other immunosuppressants (OR, 2.60). Additional risk factors were use of anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha for rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.13), solid tumors (OR, 4.66), current pneumonia (OR, 5.54), cardiovascular disease (OR, 1.73), and low body mass index (OR, 3.04).

Additional marginal or nonsignificant associations with NTM-PD risk were found for lung function, diabetes, renal disease, cancer, healthy weight, and infection with either Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus aureus.

Possible protective factors, though not significant, included increasing or high BMI and long-term macrolide use.

Bronchiectasis, which is associated with the highest risk of NTM-PD, was assessed in four studies. It was evaluated less frequently because it was often considered a reason for study exclusion, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“However, many studies report high numbers of patients with nodular bronchiectatic NTM-PD and is suggested to be almost universal in patients with noncavitary NTM-PD,” they said.

The most common risk factors for NTM-PD in the included studies were the use of immunosuppressants, female sex, COPD comorbidity, and history of suspected tuberculosis.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the high level of heterogeneity among the included studies, the lack of data on attributable risk, and inconsistent definitions of NTM-PD, the researchers noted. However, the results may be useful for highlighting risk factors that could be used to identify high-risk patients and to promote early diagnosis and treatment, they said. In addition, long-term studies are needed regarding the impact of multiple potential risk factors on individual risk for NTM-PD among patients with respiratory disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by Insmed BV. Dr. Loebinger has relationships with Insmed, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Savara, Parion, Zambon, 30T, Electromed, Recode, AN2 Therapeutics, and Armata.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

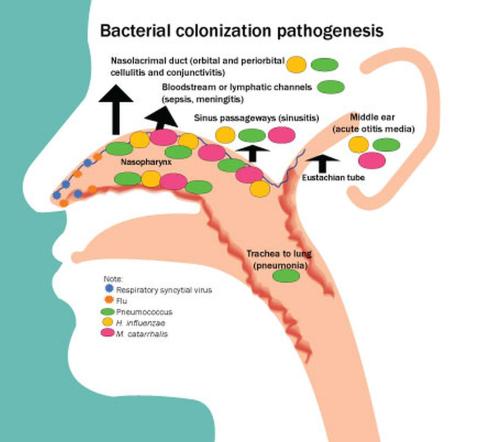

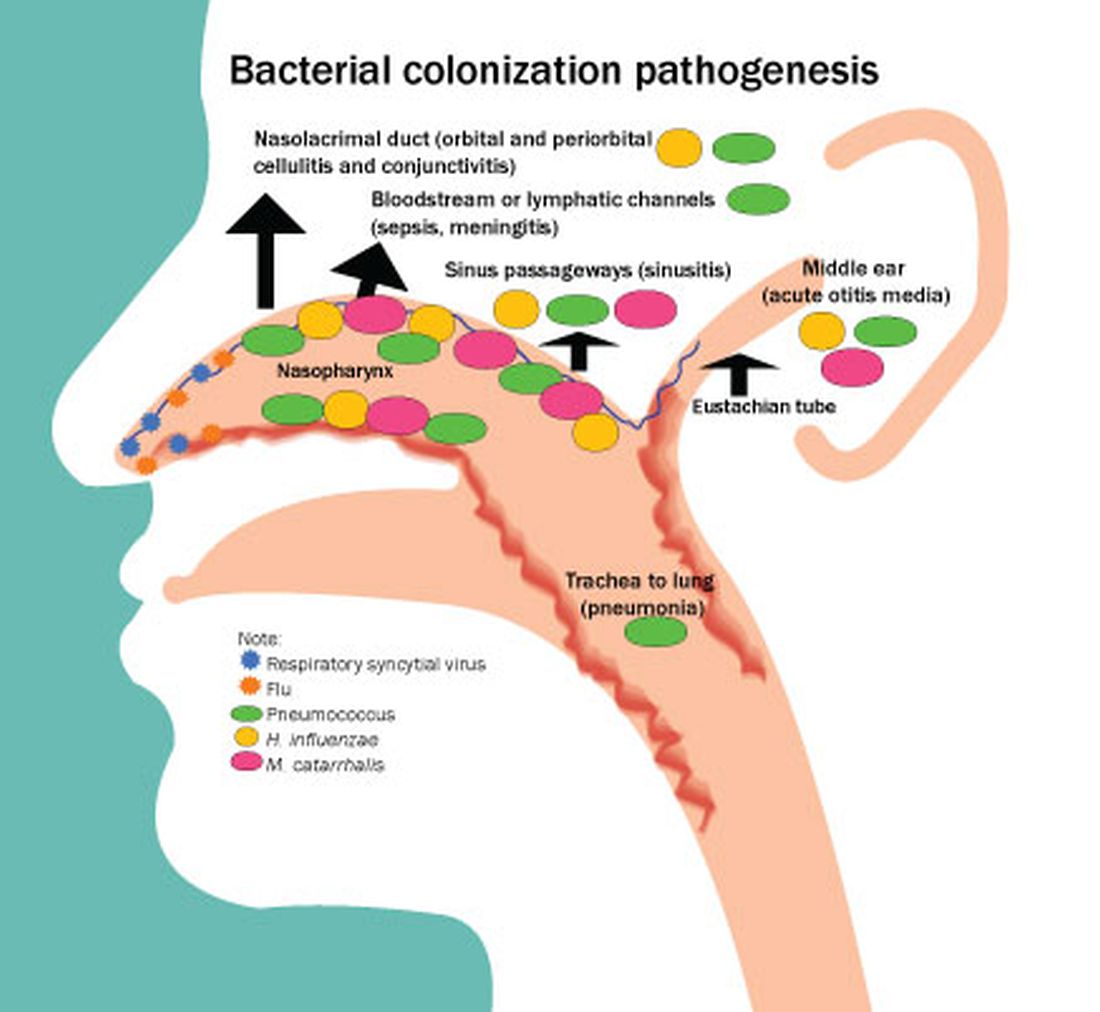

CDC signs off on RSV vaccine for older adults

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has given a green light to two new vaccines to protect against respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, in older adults.

CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, agreed with and endorsed the recommendations made earlier by CDC advisors that people age 60 and over may get one of two new vaccines for RSV. Decisions should be made based on discussions with one’s health care provider about whether the vaccine is right for them, the federal health agency said.

The new vaccines, the first licensed in the United States to protect against the respiratory illness, are expected to be available this fall.

On June 21, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), an independent panel, stopped short of recommending the vaccines for everyone age 65 and above, which was the original question the committee was to consider. The experts amended that question, changing it to whether the panel should recommend the vaccine for those 65 and above if the person and their doctor agreed. The committee voted 9 to 5 in favor.

RSV vaccines

RSV leads to 6,000 to 10,000 deaths a year in the United States among those age 65 and older and 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations in that group. Seniors and infants are among the most vulnerable to the lower respiratory infection, marked by runny nose, wheezing, sneezing, decreased appetite, and fever.

The FDA in May approved two vaccines — GSK’s Arexvy and Pfizer’s Abrysvo — for adults age 60 and above.

The vote recommending shared decision-making about the vaccine, instead of a routine vaccination recommended for all, “is a weaker recommendation,” said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville and medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Dr. Schaffner is a non-voting member of ACIP. He attended the meeting.

He said the experts voiced concern about a number of issues, including what some saw as a lack of sufficient data from trials on the most vulnerable groups, such as nursing home residents.

Experts also wanted more information about the duration of protection and exactly when a second dose might be needed. At the meeting, a GSK official said its vaccine was 84.6% effective after one and a half seasons, down from 94.1% after one season. A Pfizer official said its vaccine decreased the risk of RSV with three or more symptoms by 78.6% after a season and a half, down from 88.9% after one season.

The panel also wanted more data on whether the RSV vaccines could be administered at the same time as other vaccines recommended for adults.

Both companies gave a range of cost estimates. Pfizer expects its vaccine to cost $180 to $270 but said it could not guarantee that range. GSK said it expects a price of $200 to $295. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, recommended vaccines are covered under Medicare for those with Part D plans, which 51 million of 65 million Medicare patients have. Commercial insurance is likely to cover the vaccines if the CDC recommends them.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 7/5/23.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has given a green light to two new vaccines to protect against respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, in older adults.

CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, agreed with and endorsed the recommendations made earlier by CDC advisors that people age 60 and over may get one of two new vaccines for RSV. Decisions should be made based on discussions with one’s health care provider about whether the vaccine is right for them, the federal health agency said.

The new vaccines, the first licensed in the United States to protect against the respiratory illness, are expected to be available this fall.

On June 21, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), an independent panel, stopped short of recommending the vaccines for everyone age 65 and above, which was the original question the committee was to consider. The experts amended that question, changing it to whether the panel should recommend the vaccine for those 65 and above if the person and their doctor agreed. The committee voted 9 to 5 in favor.

RSV vaccines

RSV leads to 6,000 to 10,000 deaths a year in the United States among those age 65 and older and 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations in that group. Seniors and infants are among the most vulnerable to the lower respiratory infection, marked by runny nose, wheezing, sneezing, decreased appetite, and fever.

The FDA in May approved two vaccines — GSK’s Arexvy and Pfizer’s Abrysvo — for adults age 60 and above.

The vote recommending shared decision-making about the vaccine, instead of a routine vaccination recommended for all, “is a weaker recommendation,” said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville and medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Dr. Schaffner is a non-voting member of ACIP. He attended the meeting.

He said the experts voiced concern about a number of issues, including what some saw as a lack of sufficient data from trials on the most vulnerable groups, such as nursing home residents.

Experts also wanted more information about the duration of protection and exactly when a second dose might be needed. At the meeting, a GSK official said its vaccine was 84.6% effective after one and a half seasons, down from 94.1% after one season. A Pfizer official said its vaccine decreased the risk of RSV with three or more symptoms by 78.6% after a season and a half, down from 88.9% after one season.

The panel also wanted more data on whether the RSV vaccines could be administered at the same time as other vaccines recommended for adults.

Both companies gave a range of cost estimates. Pfizer expects its vaccine to cost $180 to $270 but said it could not guarantee that range. GSK said it expects a price of $200 to $295. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, recommended vaccines are covered under Medicare for those with Part D plans, which 51 million of 65 million Medicare patients have. Commercial insurance is likely to cover the vaccines if the CDC recommends them.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 7/5/23.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has given a green light to two new vaccines to protect against respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, in older adults.

CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, agreed with and endorsed the recommendations made earlier by CDC advisors that people age 60 and over may get one of two new vaccines for RSV. Decisions should be made based on discussions with one’s health care provider about whether the vaccine is right for them, the federal health agency said.

The new vaccines, the first licensed in the United States to protect against the respiratory illness, are expected to be available this fall.

On June 21, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), an independent panel, stopped short of recommending the vaccines for everyone age 65 and above, which was the original question the committee was to consider. The experts amended that question, changing it to whether the panel should recommend the vaccine for those 65 and above if the person and their doctor agreed. The committee voted 9 to 5 in favor.

RSV vaccines

RSV leads to 6,000 to 10,000 deaths a year in the United States among those age 65 and older and 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations in that group. Seniors and infants are among the most vulnerable to the lower respiratory infection, marked by runny nose, wheezing, sneezing, decreased appetite, and fever.

The FDA in May approved two vaccines — GSK’s Arexvy and Pfizer’s Abrysvo — for adults age 60 and above.

The vote recommending shared decision-making about the vaccine, instead of a routine vaccination recommended for all, “is a weaker recommendation,” said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville and medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. Dr. Schaffner is a non-voting member of ACIP. He attended the meeting.

He said the experts voiced concern about a number of issues, including what some saw as a lack of sufficient data from trials on the most vulnerable groups, such as nursing home residents.

Experts also wanted more information about the duration of protection and exactly when a second dose might be needed. At the meeting, a GSK official said its vaccine was 84.6% effective after one and a half seasons, down from 94.1% after one season. A Pfizer official said its vaccine decreased the risk of RSV with three or more symptoms by 78.6% after a season and a half, down from 88.9% after one season.

The panel also wanted more data on whether the RSV vaccines could be administered at the same time as other vaccines recommended for adults.

Both companies gave a range of cost estimates. Pfizer expects its vaccine to cost $180 to $270 but said it could not guarantee that range. GSK said it expects a price of $200 to $295. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, recommended vaccines are covered under Medicare for those with Part D plans, which 51 million of 65 million Medicare patients have. Commercial insurance is likely to cover the vaccines if the CDC recommends them.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 7/5/23.

Observation recommended as first-line therapy in select cases of primary spontaneous pneumothorax

Observation should be considered the first-line treatment of choice in appropriately selected primary spontaneous pneumothorax patients, according to a review comparing observation alone with aspiration or chest tube placement.

Observation was the dominant choice, based on economic modeling showing it to offer both the highest utility and the lowest cost, according to the review, published in CHEST, which encompassed 20 years of relevant publications.

, Gilgamesh Eamer, MD, MSc, FRCSC, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, and colleagues wrote. They pointed to recent studies suggesting equivalent or improved outcomes with simple observation in appropriately selected patients. The authors asked, “What management strategy derives the most utility for patients given the cost and morbidity of chest tube placement, hospital admission, surgical intervention and the risk of recurrence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax.”

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax, which leads to progressive pulmonary collapse and respiratory compromise, is thought to be attributable to rupture of air-containing blisters (or bullae) formed under the visceral pleura of the lung, according to the researchers. They stated that, while prior systematic reviews have examined various primary spontaneous pneumothorax management techniques, no reviews encompass more recently published high-quality studies comparing aspiration to other interventions such as observation or Heimlich valve devices.

The authors identified 22 articles for systematic review and meta-analysis after screening an initial list of 5,179 potentially relevant articles (Jan. 1, 2000 to April 10, 2020). They compared observation, needle aspiration, and chest tube placement, and created an economic model for these three treatment pathways based on Canadian medical cost data. The primary outcome measure was resolution following the initial intervention. Secondary outcomes included primary spontaneous pneumothorax recurrence, length of hospital stay, and treatment complications.

The analysis revealed that, compared with observation, chest tube and aspiration had higher resolution without additional intervention (relative risk for chest tube, 0.81; P < .01; RR for aspiration, 0.73; P < .01). Compared with a chest tube, observation and aspiration had shorter length of stay (mean difference for observation, 5.17; P < .01): (MD for aspiration, 2.72; P < .01).

Two-year recurrence rates did not differ between management strategies. Cost utility modeling found a cost of $14,658 (Canadian dollars [CAD] with 1.2535 = 1 US dollar) for chest tube placement, $13,126 CAD for aspiration, and $6,408 CAD for observation.

The utility (a measure including both quantity and quality of life) for each management arm was 0.77 for CT placement, 0.79 for aspiration, and 0.82 for observation. “The observation arm dominates the other two arms meaning it results in a more desirable (higher) utility with lower cost and results in a negative ICER [incremental cost-effectiveness ratio],” the authors stated.

They observed further that it is not typical for a medical intervention to improve patient outcomes, compared with standard care, and at the same time to bring costs down. “Given this, and the increasing evidence that observation is safe and effective in appropriately selected patients presenting with primary spontaneous pneumothorax,” they concluded that “observation should be considered in all patients presenting with primary spontaneous pneumothorax who meet predefined criteria.” They added that, because aspiration is favored over chest tube placement, it should be considered second-line therapy in well-selected primary spontaneous pneumothorax patients presenting with recurrence or who have failed a trial of observation.

“This review sheds light on ‘less is better’ for primary spontaneous pneumothorax management,” commented Dharani K. Narendra, MD, of the department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “It allows clinicians to utilize a ‘wait approach’ versus invasive treatment. Interestingly, recurrence was lower in the observation group.” She said further, in an interview, “In general we assume that if no intervention is done, there is higher chance of recurrence. However, this meta-analysis reveals that is not the case; there is no difference in recurrence of pneumothorax in all groups and fewer complications in the observation group. The invasive treatments such as aspiration or chest tube are risky as they have more complications like pain, bleeding, injury to surrounding structures, etc.”

Neither Dr. Eamer nor Dr. Narendra reported any conflicts of interest. The study was self-funded.

Observation should be considered the first-line treatment of choice in appropriately selected primary spontaneous pneumothorax patients, according to a review comparing observation alone with aspiration or chest tube placement.

Observation was the dominant choice, based on economic modeling showing it to offer both the highest utility and the lowest cost, according to the review, published in CHEST, which encompassed 20 years of relevant publications.

, Gilgamesh Eamer, MD, MSc, FRCSC, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, and colleagues wrote. They pointed to recent studies suggesting equivalent or improved outcomes with simple observation in appropriately selected patients. The authors asked, “What management strategy derives the most utility for patients given the cost and morbidity of chest tube placement, hospital admission, surgical intervention and the risk of recurrence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax.”

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax, which leads to progressive pulmonary collapse and respiratory compromise, is thought to be attributable to rupture of air-containing blisters (or bullae) formed under the visceral pleura of the lung, according to the researchers. They stated that, while prior systematic reviews have examined various primary spontaneous pneumothorax management techniques, no reviews encompass more recently published high-quality studies comparing aspiration to other interventions such as observation or Heimlich valve devices.

The authors identified 22 articles for systematic review and meta-analysis after screening an initial list of 5,179 potentially relevant articles (Jan. 1, 2000 to April 10, 2020). They compared observation, needle aspiration, and chest tube placement, and created an economic model for these three treatment pathways based on Canadian medical cost data. The primary outcome measure was resolution following the initial intervention. Secondary outcomes included primary spontaneous pneumothorax recurrence, length of hospital stay, and treatment complications.

The analysis revealed that, compared with observation, chest tube and aspiration had higher resolution without additional intervention (relative risk for chest tube, 0.81; P < .01; RR for aspiration, 0.73; P < .01). Compared with a chest tube, observation and aspiration had shorter length of stay (mean difference for observation, 5.17; P < .01): (MD for aspiration, 2.72; P < .01).

Two-year recurrence rates did not differ between management strategies. Cost utility modeling found a cost of $14,658 (Canadian dollars [CAD] with 1.2535 = 1 US dollar) for chest tube placement, $13,126 CAD for aspiration, and $6,408 CAD for observation.

The utility (a measure including both quantity and quality of life) for each management arm was 0.77 for CT placement, 0.79 for aspiration, and 0.82 for observation. “The observation arm dominates the other two arms meaning it results in a more desirable (higher) utility with lower cost and results in a negative ICER [incremental cost-effectiveness ratio],” the authors stated.

They observed further that it is not typical for a medical intervention to improve patient outcomes, compared with standard care, and at the same time to bring costs down. “Given this, and the increasing evidence that observation is safe and effective in appropriately selected patients presenting with primary spontaneous pneumothorax,” they concluded that “observation should be considered in all patients presenting with primary spontaneous pneumothorax who meet predefined criteria.” They added that, because aspiration is favored over chest tube placement, it should be considered second-line therapy in well-selected primary spontaneous pneumothorax patients presenting with recurrence or who have failed a trial of observation.

“This review sheds light on ‘less is better’ for primary spontaneous pneumothorax management,” commented Dharani K. Narendra, MD, of the department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “It allows clinicians to utilize a ‘wait approach’ versus invasive treatment. Interestingly, recurrence was lower in the observation group.” She said further, in an interview, “In general we assume that if no intervention is done, there is higher chance of recurrence. However, this meta-analysis reveals that is not the case; there is no difference in recurrence of pneumothorax in all groups and fewer complications in the observation group. The invasive treatments such as aspiration or chest tube are risky as they have more complications like pain, bleeding, injury to surrounding structures, etc.”

Neither Dr. Eamer nor Dr. Narendra reported any conflicts of interest. The study was self-funded.

Observation should be considered the first-line treatment of choice in appropriately selected primary spontaneous pneumothorax patients, according to a review comparing observation alone with aspiration or chest tube placement.

Observation was the dominant choice, based on economic modeling showing it to offer both the highest utility and the lowest cost, according to the review, published in CHEST, which encompassed 20 years of relevant publications.

, Gilgamesh Eamer, MD, MSc, FRCSC, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, and colleagues wrote. They pointed to recent studies suggesting equivalent or improved outcomes with simple observation in appropriately selected patients. The authors asked, “What management strategy derives the most utility for patients given the cost and morbidity of chest tube placement, hospital admission, surgical intervention and the risk of recurrence of primary spontaneous pneumothorax.”

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax, which leads to progressive pulmonary collapse and respiratory compromise, is thought to be attributable to rupture of air-containing blisters (or bullae) formed under the visceral pleura of the lung, according to the researchers. They stated that, while prior systematic reviews have examined various primary spontaneous pneumothorax management techniques, no reviews encompass more recently published high-quality studies comparing aspiration to other interventions such as observation or Heimlich valve devices.

The authors identified 22 articles for systematic review and meta-analysis after screening an initial list of 5,179 potentially relevant articles (Jan. 1, 2000 to April 10, 2020). They compared observation, needle aspiration, and chest tube placement, and created an economic model for these three treatment pathways based on Canadian medical cost data. The primary outcome measure was resolution following the initial intervention. Secondary outcomes included primary spontaneous pneumothorax recurrence, length of hospital stay, and treatment complications.

The analysis revealed that, compared with observation, chest tube and aspiration had higher resolution without additional intervention (relative risk for chest tube, 0.81; P < .01; RR for aspiration, 0.73; P < .01). Compared with a chest tube, observation and aspiration had shorter length of stay (mean difference for observation, 5.17; P < .01): (MD for aspiration, 2.72; P < .01).

Two-year recurrence rates did not differ between management strategies. Cost utility modeling found a cost of $14,658 (Canadian dollars [CAD] with 1.2535 = 1 US dollar) for chest tube placement, $13,126 CAD for aspiration, and $6,408 CAD for observation.

The utility (a measure including both quantity and quality of life) for each management arm was 0.77 for CT placement, 0.79 for aspiration, and 0.82 for observation. “The observation arm dominates the other two arms meaning it results in a more desirable (higher) utility with lower cost and results in a negative ICER [incremental cost-effectiveness ratio],” the authors stated.

They observed further that it is not typical for a medical intervention to improve patient outcomes, compared with standard care, and at the same time to bring costs down. “Given this, and the increasing evidence that observation is safe and effective in appropriately selected patients presenting with primary spontaneous pneumothorax,” they concluded that “observation should be considered in all patients presenting with primary spontaneous pneumothorax who meet predefined criteria.” They added that, because aspiration is favored over chest tube placement, it should be considered second-line therapy in well-selected primary spontaneous pneumothorax patients presenting with recurrence or who have failed a trial of observation.

“This review sheds light on ‘less is better’ for primary spontaneous pneumothorax management,” commented Dharani K. Narendra, MD, of the department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “It allows clinicians to utilize a ‘wait approach’ versus invasive treatment. Interestingly, recurrence was lower in the observation group.” She said further, in an interview, “In general we assume that if no intervention is done, there is higher chance of recurrence. However, this meta-analysis reveals that is not the case; there is no difference in recurrence of pneumothorax in all groups and fewer complications in the observation group. The invasive treatments such as aspiration or chest tube are risky as they have more complications like pain, bleeding, injury to surrounding structures, etc.”

Neither Dr. Eamer nor Dr. Narendra reported any conflicts of interest. The study was self-funded.

FROM CHEST

Few of those eligible get lung cancer screening, despite USPSTF recommendations

Only 12.8% of eligible adults get CT screening for lung cancer, despite recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Kristin G. Maki, PhD, with Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, led a team that estimated lung cancer screening (LCS) from the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in four states (Maine, Michigan, New Jersey, and Rhode Island).

“Increasing LCS among eligible adults is a national priority,” the authors wrote in the study, published online in JAMA Network Open. Lung cancer remains the top cause of cancer in the United States and smoking accounts for approximately 90% of cases.

Screening much higher for other cancers

The authors pointed out that screening rates for eligible people are much higher for other cancers. Melzer and colleagues wrote in a 2021 editorial that breast and colon cancer screening rates are near 70% “despite combined annual death rates less than two-thirds that of lung cancer.”

The USPSTF updated its recommendations for lung cancer screening in March 2021.

Eligibility now includes anyone aged between 50 and 80 years who has smoked at least 20 pack-years and either still smokes or quit within the last 15 years.

The researchers found that, when comparing screening by health status, the highest odds for screening were seen in those who reported they were in poor health, which is concerning, the authors note, because those patients may not be healthy enough to benefit from treatment for their lung cancer.

The odds ratio for getting screening was 2.88 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-9.77) times higher than that of the reference group, which reported excellent health.

Rates differ by state

Consistent with previous studies, this analysis found that screening rates differed by state. Their analysis, for example, showed a higher likelihood of screening for respondents in Rhode Island, compared with Maine (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.05-3.67; P = .03).

Patients who reported having a primary health professional were more than five times more likely to undergo screening, compared with those without one (OR, 5.62; 95% CI, 1.19-26.49).

The authors said their results also highlight the need for Medicare coverage for screening as those with public insurance had lower odds of screening than those with private insurance (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.42-1.56).

Neelima Navuluri, MD, assistant professor in the division of pulmonary, allergy, and critical care at Duke University and the Duke Global Health Institute, both in Durham, N.C., pointed out that the study highlights age, smoking status, and health care access as key factors associated with lack of uptake.

Work needed on all levels

Dr. Navuluri said in an interview that multifaceted patient-, provider- and system-level interventions are needed to improve screening rates.

“For example, we need more community engagement to increase knowledge and awareness of eligibility for lung cancer screening,” she said.

She highlighted the need for interventions around improving and streamlining shared decision-making conversations about screening (a CMS requirement that does not exist for other cancer screening).

Emphasis is needed on younger age groups, people who currently smoke, and communities of color as well as policy to improve insurance coverage of screening, she said.

Dr. Navuluri, who also works with the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, was lead author on a study published in JAMA Network Open on racial disparities in screening among veterans.

“We demonstrate similar findings related to age, smoking status, and poor health status,” she said. “We discuss the need for more qualitative studies to better understand the role of these factors as well as implementation studies to assess effectiveness of various interventions to improve disparities in lung cancer screening rates.”

“Research to identify facilitators for LCS among persons who currently smoke is needed, including a focus on the role of stigma as a barrier to screening,” they wrote.

One coauthor is supported by the cancer prevention and research training program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Navuluri receives funding from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for work on lung cancer screening.

Only 12.8% of eligible adults get CT screening for lung cancer, despite recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Kristin G. Maki, PhD, with Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, led a team that estimated lung cancer screening (LCS) from the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in four states (Maine, Michigan, New Jersey, and Rhode Island).

“Increasing LCS among eligible adults is a national priority,” the authors wrote in the study, published online in JAMA Network Open. Lung cancer remains the top cause of cancer in the United States and smoking accounts for approximately 90% of cases.

Screening much higher for other cancers

The authors pointed out that screening rates for eligible people are much higher for other cancers. Melzer and colleagues wrote in a 2021 editorial that breast and colon cancer screening rates are near 70% “despite combined annual death rates less than two-thirds that of lung cancer.”

The USPSTF updated its recommendations for lung cancer screening in March 2021.

Eligibility now includes anyone aged between 50 and 80 years who has smoked at least 20 pack-years and either still smokes or quit within the last 15 years.

The researchers found that, when comparing screening by health status, the highest odds for screening were seen in those who reported they were in poor health, which is concerning, the authors note, because those patients may not be healthy enough to benefit from treatment for their lung cancer.

The odds ratio for getting screening was 2.88 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-9.77) times higher than that of the reference group, which reported excellent health.

Rates differ by state

Consistent with previous studies, this analysis found that screening rates differed by state. Their analysis, for example, showed a higher likelihood of screening for respondents in Rhode Island, compared with Maine (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.05-3.67; P = .03).

Patients who reported having a primary health professional were more than five times more likely to undergo screening, compared with those without one (OR, 5.62; 95% CI, 1.19-26.49).

The authors said their results also highlight the need for Medicare coverage for screening as those with public insurance had lower odds of screening than those with private insurance (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.42-1.56).

Neelima Navuluri, MD, assistant professor in the division of pulmonary, allergy, and critical care at Duke University and the Duke Global Health Institute, both in Durham, N.C., pointed out that the study highlights age, smoking status, and health care access as key factors associated with lack of uptake.

Work needed on all levels

Dr. Navuluri said in an interview that multifaceted patient-, provider- and system-level interventions are needed to improve screening rates.

“For example, we need more community engagement to increase knowledge and awareness of eligibility for lung cancer screening,” she said.

She highlighted the need for interventions around improving and streamlining shared decision-making conversations about screening (a CMS requirement that does not exist for other cancer screening).

Emphasis is needed on younger age groups, people who currently smoke, and communities of color as well as policy to improve insurance coverage of screening, she said.

Dr. Navuluri, who also works with the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, was lead author on a study published in JAMA Network Open on racial disparities in screening among veterans.

“We demonstrate similar findings related to age, smoking status, and poor health status,” she said. “We discuss the need for more qualitative studies to better understand the role of these factors as well as implementation studies to assess effectiveness of various interventions to improve disparities in lung cancer screening rates.”

“Research to identify facilitators for LCS among persons who currently smoke is needed, including a focus on the role of stigma as a barrier to screening,” they wrote.

One coauthor is supported by the cancer prevention and research training program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Navuluri receives funding from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for work on lung cancer screening.

Only 12.8% of eligible adults get CT screening for lung cancer, despite recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Kristin G. Maki, PhD, with Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, led a team that estimated lung cancer screening (LCS) from the 2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in four states (Maine, Michigan, New Jersey, and Rhode Island).

“Increasing LCS among eligible adults is a national priority,” the authors wrote in the study, published online in JAMA Network Open. Lung cancer remains the top cause of cancer in the United States and smoking accounts for approximately 90% of cases.

Screening much higher for other cancers

The authors pointed out that screening rates for eligible people are much higher for other cancers. Melzer and colleagues wrote in a 2021 editorial that breast and colon cancer screening rates are near 70% “despite combined annual death rates less than two-thirds that of lung cancer.”

The USPSTF updated its recommendations for lung cancer screening in March 2021.

Eligibility now includes anyone aged between 50 and 80 years who has smoked at least 20 pack-years and either still smokes or quit within the last 15 years.

The researchers found that, when comparing screening by health status, the highest odds for screening were seen in those who reported they were in poor health, which is concerning, the authors note, because those patients may not be healthy enough to benefit from treatment for their lung cancer.

The odds ratio for getting screening was 2.88 (95% confidence interval, 0.85-9.77) times higher than that of the reference group, which reported excellent health.

Rates differ by state

Consistent with previous studies, this analysis found that screening rates differed by state. Their analysis, for example, showed a higher likelihood of screening for respondents in Rhode Island, compared with Maine (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.05-3.67; P = .03).

Patients who reported having a primary health professional were more than five times more likely to undergo screening, compared with those without one (OR, 5.62; 95% CI, 1.19-26.49).

The authors said their results also highlight the need for Medicare coverage for screening as those with public insurance had lower odds of screening than those with private insurance (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.42-1.56).

Neelima Navuluri, MD, assistant professor in the division of pulmonary, allergy, and critical care at Duke University and the Duke Global Health Institute, both in Durham, N.C., pointed out that the study highlights age, smoking status, and health care access as key factors associated with lack of uptake.

Work needed on all levels

Dr. Navuluri said in an interview that multifaceted patient-, provider- and system-level interventions are needed to improve screening rates.

“For example, we need more community engagement to increase knowledge and awareness of eligibility for lung cancer screening,” she said.

She highlighted the need for interventions around improving and streamlining shared decision-making conversations about screening (a CMS requirement that does not exist for other cancer screening).

Emphasis is needed on younger age groups, people who currently smoke, and communities of color as well as policy to improve insurance coverage of screening, she said.

Dr. Navuluri, who also works with the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, was lead author on a study published in JAMA Network Open on racial disparities in screening among veterans.

“We demonstrate similar findings related to age, smoking status, and poor health status,” she said. “We discuss the need for more qualitative studies to better understand the role of these factors as well as implementation studies to assess effectiveness of various interventions to improve disparities in lung cancer screening rates.”

“Research to identify facilitators for LCS among persons who currently smoke is needed, including a focus on the role of stigma as a barrier to screening,” they wrote.

One coauthor is supported by the cancer prevention and research training program at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Navuluri receives funding from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for work on lung cancer screening.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Rehabilitation improves walk test results for post–pulmonary embolism patients with persistent dyspnea

In patients with persistent dyspnea following a pulmonary embolism, rehabilitation should be considered as a treatment option, according to findings from a randomized, controlled trial comparing usual care to a twice-weekly, 8-week physical exercise program.

The prevalence of persistent dyspnea, functional limitations, and reduced quality of life (QoL) after pulmonary embolism (PE) ranges from 30% to 50% in published studies. While the underlying mechanisms remain unclear and are likely multifactorial, Øyvind Jervan, MD, and colleagues reported, research suggests that deconditioning and psychological factors contribute substantially to post-PE impairment. Optimal management remains unknown.

The investigators randomized adult patients 1:1 from two hospitals (Osfold Hospital and Akershus University Hospital) with PE identified via computed tomography pulmonary angiography 6-72 months prior to study inclusion to either a supervised outpatient exercise program or usual care. The once- or twice-weekly home-based program was tailored to each participant and included a 90-minute educational session on the cardiopulmonary system, diagnosis and treatment of PE and its possible long-term effects, the benefits of exercise and physical activity, and the management of breathlessness. Also during the intervention period, participants were given a simple home-based exercise program to be performed once or twice weekly. Differences between groups in the Incremental Shuttle Walk Test (ISWT), a standardized walking test that assesses exercise capacity, was the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints included an endurance walk test (ESWT) and measures of symptoms and QoL.

Among 211 participants (median age 57 years; 56% men), the median time from diagnosis to inclusion was 10.3 months. Median baseline walking distance on the ISWT was 695 m with 21% achieving the 1,020-m maximum distance. At follow-up, a between-group difference of 53.0 m favored the rehabilitation group (89 evaluable subjects; 87 in usual care) (P = .0035). While subgroup analysis revealed a greater difference for those with shorter time from diagnosis (6-12 months vs. 12.1-72 months), the between-group differences were nonsignificant. Also, no ISWT differences between the intervention and control group were found for those with higher pulmonary embolism severity and dyspnea scores. The walk endurance test revealed no between-group differences.

Scores at follow-up on the Pulmonary Embolism-QoL questionnaire favored the rehabilitation group (mean difference –4%; P = .041), but there were no differences in generic QoL, dyspnea scores, or the ESWT.

“The present study adds to the growing evidence of the benefits of rehabilitation after PE,” the researchers stated. Although several recent studies have shown rehabilitation after PE results that were promising, the authors pointed out that most of these studies have been small or have lacked a control group, with great variations between them with respect to time, mode, and duration of intervention. In addition, the current study is the largest one addressing the effect of rehabilitation after PE to demonstrate in subjects with persistent dyspnea a positive effect on exercise capacity and QoL.

The researchers also commented that the small detected mean difference of 53 m in walking distance was lower than has been considered a worthwhile improvement by some, and its clinical relevance can be debated. Other studies, however, have used mean group differences of 40-62 m as clinically meaningful. The authors underscored also that the ISWT data were subject to a considerable ceiling effect which may underestimate the effect size.

Addressing study limitations, the researchers added that: “The rehabilitation program in the present study consisted mainly of exercise training. It is unknown whether the addition of occupational therapy, psychology, or dietary therapy would provide additional benefits for the participants. Most participants had mild symptoms, which may have limited the potential benefits of our rehabilitation program.”

The project was funded by Østfold Hospital Trust. Dr. Jervan reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

In patients with persistent dyspnea following a pulmonary embolism, rehabilitation should be considered as a treatment option, according to findings from a randomized, controlled trial comparing usual care to a twice-weekly, 8-week physical exercise program.

The prevalence of persistent dyspnea, functional limitations, and reduced quality of life (QoL) after pulmonary embolism (PE) ranges from 30% to 50% in published studies. While the underlying mechanisms remain unclear and are likely multifactorial, Øyvind Jervan, MD, and colleagues reported, research suggests that deconditioning and psychological factors contribute substantially to post-PE impairment. Optimal management remains unknown.

The investigators randomized adult patients 1:1 from two hospitals (Osfold Hospital and Akershus University Hospital) with PE identified via computed tomography pulmonary angiography 6-72 months prior to study inclusion to either a supervised outpatient exercise program or usual care. The once- or twice-weekly home-based program was tailored to each participant and included a 90-minute educational session on the cardiopulmonary system, diagnosis and treatment of PE and its possible long-term effects, the benefits of exercise and physical activity, and the management of breathlessness. Also during the intervention period, participants were given a simple home-based exercise program to be performed once or twice weekly. Differences between groups in the Incremental Shuttle Walk Test (ISWT), a standardized walking test that assesses exercise capacity, was the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints included an endurance walk test (ESWT) and measures of symptoms and QoL.

Among 211 participants (median age 57 years; 56% men), the median time from diagnosis to inclusion was 10.3 months. Median baseline walking distance on the ISWT was 695 m with 21% achieving the 1,020-m maximum distance. At follow-up, a between-group difference of 53.0 m favored the rehabilitation group (89 evaluable subjects; 87 in usual care) (P = .0035). While subgroup analysis revealed a greater difference for those with shorter time from diagnosis (6-12 months vs. 12.1-72 months), the between-group differences were nonsignificant. Also, no ISWT differences between the intervention and control group were found for those with higher pulmonary embolism severity and dyspnea scores. The walk endurance test revealed no between-group differences.

Scores at follow-up on the Pulmonary Embolism-QoL questionnaire favored the rehabilitation group (mean difference –4%; P = .041), but there were no differences in generic QoL, dyspnea scores, or the ESWT.

“The present study adds to the growing evidence of the benefits of rehabilitation after PE,” the researchers stated. Although several recent studies have shown rehabilitation after PE results that were promising, the authors pointed out that most of these studies have been small or have lacked a control group, with great variations between them with respect to time, mode, and duration of intervention. In addition, the current study is the largest one addressing the effect of rehabilitation after PE to demonstrate in subjects with persistent dyspnea a positive effect on exercise capacity and QoL.

The researchers also commented that the small detected mean difference of 53 m in walking distance was lower than has been considered a worthwhile improvement by some, and its clinical relevance can be debated. Other studies, however, have used mean group differences of 40-62 m as clinically meaningful. The authors underscored also that the ISWT data were subject to a considerable ceiling effect which may underestimate the effect size.

Addressing study limitations, the researchers added that: “The rehabilitation program in the present study consisted mainly of exercise training. It is unknown whether the addition of occupational therapy, psychology, or dietary therapy would provide additional benefits for the participants. Most participants had mild symptoms, which may have limited the potential benefits of our rehabilitation program.”

The project was funded by Østfold Hospital Trust. Dr. Jervan reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

In patients with persistent dyspnea following a pulmonary embolism, rehabilitation should be considered as a treatment option, according to findings from a randomized, controlled trial comparing usual care to a twice-weekly, 8-week physical exercise program.

The prevalence of persistent dyspnea, functional limitations, and reduced quality of life (QoL) after pulmonary embolism (PE) ranges from 30% to 50% in published studies. While the underlying mechanisms remain unclear and are likely multifactorial, Øyvind Jervan, MD, and colleagues reported, research suggests that deconditioning and psychological factors contribute substantially to post-PE impairment. Optimal management remains unknown.

The investigators randomized adult patients 1:1 from two hospitals (Osfold Hospital and Akershus University Hospital) with PE identified via computed tomography pulmonary angiography 6-72 months prior to study inclusion to either a supervised outpatient exercise program or usual care. The once- or twice-weekly home-based program was tailored to each participant and included a 90-minute educational session on the cardiopulmonary system, diagnosis and treatment of PE and its possible long-term effects, the benefits of exercise and physical activity, and the management of breathlessness. Also during the intervention period, participants were given a simple home-based exercise program to be performed once or twice weekly. Differences between groups in the Incremental Shuttle Walk Test (ISWT), a standardized walking test that assesses exercise capacity, was the primary endpoint. Secondary endpoints included an endurance walk test (ESWT) and measures of symptoms and QoL.

Among 211 participants (median age 57 years; 56% men), the median time from diagnosis to inclusion was 10.3 months. Median baseline walking distance on the ISWT was 695 m with 21% achieving the 1,020-m maximum distance. At follow-up, a between-group difference of 53.0 m favored the rehabilitation group (89 evaluable subjects; 87 in usual care) (P = .0035). While subgroup analysis revealed a greater difference for those with shorter time from diagnosis (6-12 months vs. 12.1-72 months), the between-group differences were nonsignificant. Also, no ISWT differences between the intervention and control group were found for those with higher pulmonary embolism severity and dyspnea scores. The walk endurance test revealed no between-group differences.

Scores at follow-up on the Pulmonary Embolism-QoL questionnaire favored the rehabilitation group (mean difference –4%; P = .041), but there were no differences in generic QoL, dyspnea scores, or the ESWT.

“The present study adds to the growing evidence of the benefits of rehabilitation after PE,” the researchers stated. Although several recent studies have shown rehabilitation after PE results that were promising, the authors pointed out that most of these studies have been small or have lacked a control group, with great variations between them with respect to time, mode, and duration of intervention. In addition, the current study is the largest one addressing the effect of rehabilitation after PE to demonstrate in subjects with persistent dyspnea a positive effect on exercise capacity and QoL.

The researchers also commented that the small detected mean difference of 53 m in walking distance was lower than has been considered a worthwhile improvement by some, and its clinical relevance can be debated. Other studies, however, have used mean group differences of 40-62 m as clinically meaningful. The authors underscored also that the ISWT data were subject to a considerable ceiling effect which may underestimate the effect size.

Addressing study limitations, the researchers added that: “The rehabilitation program in the present study consisted mainly of exercise training. It is unknown whether the addition of occupational therapy, psychology, or dietary therapy would provide additional benefits for the participants. Most participants had mild symptoms, which may have limited the potential benefits of our rehabilitation program.”

The project was funded by Østfold Hospital Trust. Dr. Jervan reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL CHEST

The evolving pulmonary landscape in HIV

Chronic pulmonary disease continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in individuals living with the human immunodeficiency virus, even with optimal HIV control. And this is independent, as seen in many studies, of age, smoking, and pulmonary infections.

Both chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (COPD) and lung cancer occur more frequently in people living with HIV than in the general population, and at earlier ages, and with worse outcomes. The risk for emphysema and interstitial lung abnormalities also appears to be higher, research has shown. And asthma has also recently emerged as another important lung disease in people with HIV (PWH).

“There is evidence that the severity of immunocompromise associated with HIV infection is linked with chronic lung diseases. People who have a lower CD4 cell count or a higher viral load do have an increased risk of COPD and emphysema as well as potentially lung cancer. ,” said Kristina Crothers, MD, professor in the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Research has evolved from a focus on the epidemiology of HIV-related chronic lung diseases to a current emphasis on “trying to understand further the mechanisms [behind the heightened risk] through more benchwork and corollary translational studies, and then to the next level of trying to understand what this means for how we should manage people with HIV who have chronic lung diseases,” Dr. Crothers said. “Should management be tailored for people with HIV infection?”

Impairments in immune pathways, local and systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, dysbiosis, and accelerated cellular senescence are among potential mechanisms, but until ongoing mechanistic research yields more answers, pulmonologists should simply – but importantly – be aware of the increased risk and have a low threshold for investigating respiratory symptoms, she and other experts said in interviews. Referral of eligible patients for lung cancer screening is also a priority, as is smoking cessation, they said.

Notably, while spirometry has been the most commonly studied lung function measure in PWH, another noninvasive measure, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), has garnered attention in the past decade and thus far appears to be the more frequent lung function abnormality.

In an analysis published in 2020 from the longitudinal Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) – a study of a subcohort of 591 men with HIV and 476 without HIV – those with HIV were found to have a 1.6-fold increased risk of mild DLCO impairment (< 80% of predicted normal) and a 3-fold higher risk of more severe DLCO impairment (< 60% of predicted normal). There was no significant difference in spirometry findings by HIV status.

Such findings on DLCO are worthy of consideration in clinical practice, even in the absence of HIV-specific screening guidelines for noncommunicable lung diseases, Dr. Crothers said. “In thinking about screening and diagnosing chronic lung diseases in these patients, I’d not only consider spirometry, but also diffusing capacity” when possible, she said. Impaired DLCO is seen with emphysema and pulmonary vascular diseases like pulmonary hypertension and also interstitial lung diseases.

Key chronic lung diseases

Ken M. Kunisaki, MD, MS, associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and the first author of the MACS analysis of lung function – one of the most recent and largest reports of DLCO impairment – points out that studies of chest computed tomography (CT) have also documented higher rates of emphysema and interstitial lung abnormalities.

A chest CT analysis from a cohort in Denmark (the Copenhagen Comorbidity in HIV Infection [COCOMO] cohort) found interstitial lung abnormalities in 10.9% of more than 700 PWH which represented a 1.8-fold increased risk compared to HIV-negative controls. And a study from an Italian sample of never-smoking PWH and controls reported emphysema in 18% and 4%, respectively. These studies, which did not measure DLCO, are among those discussed in a 2021 review by Dr. Kunisaki of advances in HIV-associated chronic lung disease research.

COPD is the best studied and most commonly encountered chronic lung disease in PWH. “Particularly for COPD, what’s both interesting and unfortunate is that we haven’t really seen any changes in the epidemiology with ART (antiretroviral therapy) – we’re still seeing the same findings, like the association of HIV with worse COPD at younger ages,” said Alison Morris, MD, MS, professor of medicine, immunology, and clinical and translational research at the University of Pittsburgh. “It doesn’t seem to have improved.”

Its prevalence has varied widely from cohort to cohort, from as low as 3% (similar to the general population) to over 40%, Dr. Kunisaki said, emphasizing that many studies, including studies showing higher rates, have controlled for current and past smoking. In evaluating patients with low or no smoking burden, “don’t discount respiratory symptoms as possibly reflecting underlying lung disease because COPD can develop with low to no smoking history in those with HIV,” he advised.

A better understanding of how a chronic viral infection like HIV leads to heightened COPD risk will not only help those with HIV, he notes, but also people without HIV who have COPD but have never smoked – a woefully underappreciated and understudied population. Ongoing research, he said, “should help us understand COPD pathogenesis generally.”

Research on asthma is relatively limited thus far, but it does appear that PWH may be more prone to developing severe asthma, just as with COPD, said Dr. Kunisaki, also a staff physician at the Minneapolis Veterans Administration Health Care System. Research has shown, for instance, that people with HIV more frequently needed aggressive respiratory support when hospitalized for asthma exacerbations.

It’s unclear how much of this potentially increased severity is attributable to the biology of HIV’s impact on the body and how much relates to social factors like disparities in income and access to care, Dr. Kunisaki said, noting that the same questions apply to the more frequent COPD exacerbations documented in PWH.

Dr. Crothers points out that, while most studies do not suggest a difference in the incidence of asthma in PWH, “there is some data from researchers looking at asthma profiles [suggesting] that the biomarkers associated with asthma may be different in people with and without HIV,” signaling potentially different molecular or biologic underpinnings of the disease.

Incidence rates of lung cancer in PWH, meanwhile, have declined over the last 2 decades, but lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in PWH and occurs at a rate that is 2-2.5 times higher than that of individuals not infected with HIV, according to

Janice Leung, MD, of the division of respiratory medicine at the University of British Columbia and the Centre for Heart Lung Innovation at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver.

Patients with HIV have “worse outcomes overall and a higher risk of mortality, even when presenting at the same stage,” said Dr. Leung, who reviewed trends in COPD and lung cancer in a recently published opinion piece.

Potential drivers

A bird’s eye view of potential – and likely interrelated – mechanisms for chronic lung disease includes chronic immune activation that impairs innate and adaptive immune pathways; chronic inflammation systemically and in the lung despite viral suppression; persistence of the virus in latent reservoirs in the lung, particularly in alveolar macrophages and T cells; HIV-related proteins contributing to oxidative stress; accelerated cellular aging; dysbiosis; and ongoing injury from inhaled toxins.

All are described in the literature and are being further explored. “It’s likely that multiple pathways are playing a role,” said Dr. Crothers, “and it could be that the balance of one to another leads to different manifestations of disease.”

Biomarkers that have been elevated and associated with different features of chronic lung disease – such as airflow obstruction, low DLCO, and emphysema – include markers of inflammation (e.g., C-reactive protein, interleukin-6), monocyte activation (e.g., soluble CD14), and markers of endothelial dysfunction, she noted in a 2021 commentary marking 40 years since the first reported cases of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

In her laboratory, Dr. Leung is using new epigenetic markers to look at the pathogenesis of accelerated aging in the lung. By profiling bronchial epithelial brushings for DNA methylation and gene expression, they have found that “people living with both HIV and COPD have the fastest epigenetic age acceleration in their airway epithelium,” she said. The findings “suggest that the HIV lung is aging faster.”

They reported their findings in 2022, describing methylation disruptions along age-related pathways such as cellular senescence, longevity regulation, and insulin signaling.

Dr. Leung and her team have also studied the lung microbiome and found lower microbial diversity in the airway epithelium in patients with HIV than those without, especially in those with HIV and COPD. The National Institutes of Health–sponsored Lung HIV Microbiome Project found that changes in the lung microbiome are most pronounced in patients who haven’t yet initiated ART, but research in her lab suggests ongoing suppression of microbial diversity even after ART, she said.

Dr. Morris is particularly interested in the oral microbiome, having found through her research that changes in the oral microbiome in PWH were more related to impaired lung function than alterations in the lung and gut microbiome. “That may be in part because of the way we measure things,” she said. “But we also think that the oral microbiome probably seeds the lung [through micro-aspiration].” A study published in 2020 from the Pittsburgh site of the MACS described alterations in oral microbial communities in PWH with abnormal lung function.

Preliminary research suggests that improved dental cleaning and periodontal work in PWH and COPD may influence the severity of COPD, she noted.

“We don’t see as much of a signal with the gut microbiome [and HIV status or lung function], though there could still be ways in which gut microbiome influences the lung,” through systemic inflammation, the release of metabolites into the bloodstream, or microbial translocation, for instance, she said.

The potential role of translocation of members of the microbiome, in fact, is an area of active research for Dr. Morris. Members of the microbiome – viruses and fungi in addition to bacteria – “can get into the bloodstream from the mouth, from the lung, from the gut, to stimulate inflammation and worsen lung disease,” she said.

Key questions in an evolving research landscape

Dr. Kunisaki looks forward to research providing a more longitudinal look at lung function decline– a move beyond a dominance of cross-sectional studies – as well as research that is more comprehensive, with simultaneous collection of various functional measures (eg., DLCO with chest imaging and fractional excretion of nitric oxide (FENO – a standardized breath measure of Th2 airway inflammation).

The several-year-old NIH-supported MACS/WIHS (Women’s Interagency HIV Study) Combined Cohort study, in which Dr. Kunisaki and Dr. Morris participate, aims in part to identity biomarkers of increased risk for chronic lung disease and other chronic disorders and to develop strategies for more effective interventions and treatments.

Researchers will also share biospecimens, “which will allow more mechanistic work,” Dr. Kunisaki noted. (The combined cohort study includes participants from the earlier, separate MACS and WIHS studies.)

Questions about treatment strategies include the risks versus benefits of inhaled corticosteroids, which may increase an already elevated risk of respiratory infections like bacterial pneumonia in PWH, Dr. Kunisaki said.

[An aside: Inhaled corticosteroids also have well-described interactions with ART regimens that contain CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., ritonavir and cobicistat) that can lead to hypercortisolism. In patients who require both types of drugs, he said, beclomethasone has the least interactions and is the preferred inhaled corticosteroid.]

For Dr. Crothers, unanswered critical questions include – as she wrote in her 2021 commentary – the question of how guidelines for the management of COPD and asthma should be adapted for PWH. Is COPD in PWH more or less responsive to inhaled corticosteroids, for instance? And are antifibrotic treatments for interstitial lung disease and immunotherapies for asthma or lung cancer similarly effective, and are there any increased risks for harms in people with HIV?