User login

Study identifies predictors of bariatric surgery attrition

BALTIMORE – Even in a public health system like Canada’s, almost and researchers have identified patient characteristics that could be predictive of dropout risk that would potentially have implications in a nonuniversal system, such as that of the United States, according to a study of almost 18,000 patients reported at the annual meeting Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons.

“Even in a universal health care system, clear disparities exist among patient populations having bariatric surgery,” said Aristithes Doumouras, MD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “Extensive work-ups and long wait times can have an impact on the delivery of bariatric care.”

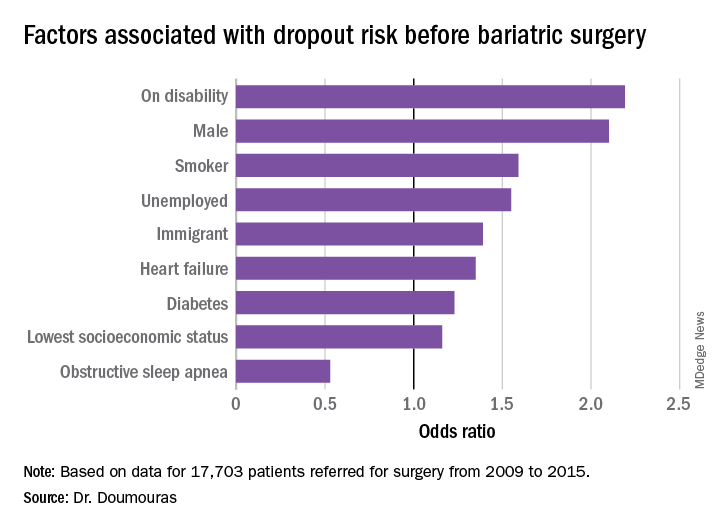

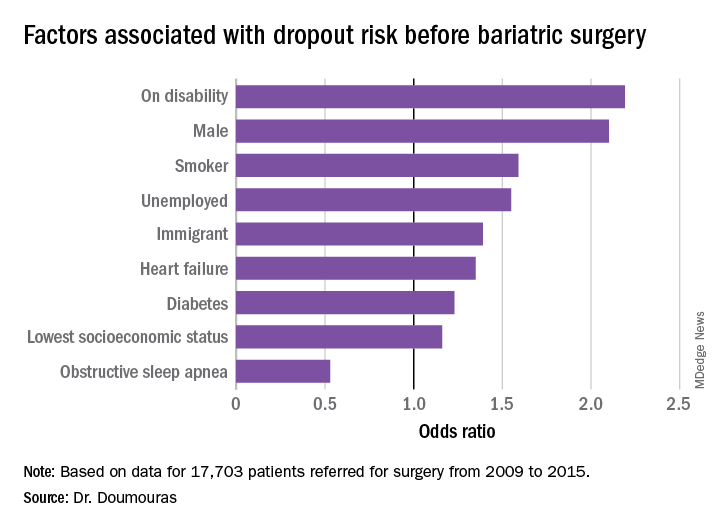

Dr. Doumouras reported on results of a retrospective, population-based study of 17,703 patients referred for surgery during 2009-2015 in the Ontario Bariatric Network, a province-wide network of 11 hospitals credentialed to perform bariatric surgery. The study found that 23.2% of patients referred for bariatric surgery did not go through with it and that overall average wait times between referral and the operation were just short of a year – 362.2 days to be precise.

The goal of the study was to identify any factors associated with attrition, Dr. Doumouras said.

“Predictors of interest included patient demographics – age, sex, income quintile, immigration status, employment status, smoking status – and comorbidities, such as diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, sleep apnea, and renal disease,” he said. “The study also evaluated health services factors, such as overall wait time to bariatric surgery, presence of centers of excellence, and health care utilization.”

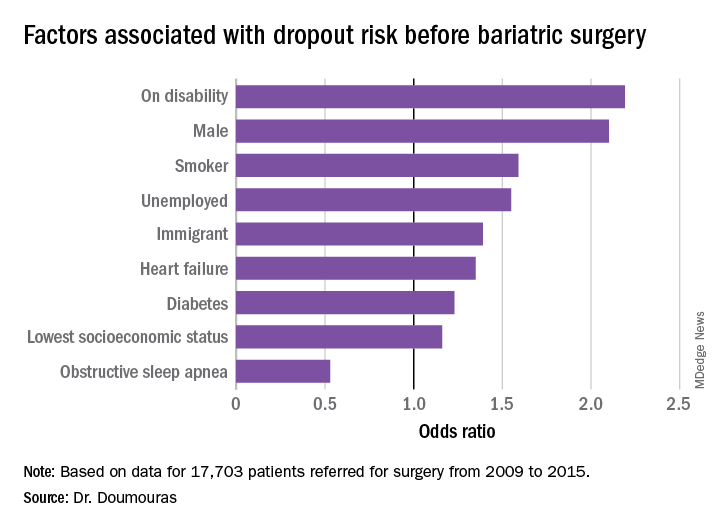

The study found that demographics with more than twice the odds of attrition were male gender and presence of a disability (P less than .01). Smokers were 60% more likely to drop out (P less than .01), he said. “To receive bariatric surgery in Ontario, smokers must go through a smoking cessation program.”

Unemployed individuals and immigrants also had higher rates of attrition, at 55% and 39%, respectively, and were more likely to not go through with the operation (P less than .01). Health factors associated with attrition, but to a lesser extent, were diabetes (odds ratio, 1.23) and heart failure (OR, 1.35; P less than .01).

“Low socioeconomic status actually had a very low impact in our system on attrition after adjustment for other demographic factors such as disability and unemployment,” Dr. Doumouras said, noting a 16% greater risk of attrition in this group (P = .02).

“Interestingly,” he noted, “there was one factor associated with less dropout – obstructive sleep apnea – probably because people hate using the CPAP machines every single night.” People with OSA were 47% less likely to drop out than were people without the disease (P less than .001).

When asked if the findings would be applicable in the United States, Dr. Doumouras said they would to an extent.

“I think we can say confidently that they would apply to most universal health care systems,” he said. “In nonuniversal health care systems, the interplay between insurance status, socioeconomic status, and the like makes it more of a complex relationship, but if you were to take any kind of health care system, even in the United States, you would probably see very similar trends in terms of who can get bariatric surgery.”

He added, “I think also the length of work-up matters. Only a 3- or 4-week work-up probably affects attrition as well. These are relatively universal things.”

Dr. Doumouras has no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Doumouras A et al. SAGES 2019, Abstract S118.

BALTIMORE – Even in a public health system like Canada’s, almost and researchers have identified patient characteristics that could be predictive of dropout risk that would potentially have implications in a nonuniversal system, such as that of the United States, according to a study of almost 18,000 patients reported at the annual meeting Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons.

“Even in a universal health care system, clear disparities exist among patient populations having bariatric surgery,” said Aristithes Doumouras, MD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “Extensive work-ups and long wait times can have an impact on the delivery of bariatric care.”

Dr. Doumouras reported on results of a retrospective, population-based study of 17,703 patients referred for surgery during 2009-2015 in the Ontario Bariatric Network, a province-wide network of 11 hospitals credentialed to perform bariatric surgery. The study found that 23.2% of patients referred for bariatric surgery did not go through with it and that overall average wait times between referral and the operation were just short of a year – 362.2 days to be precise.

The goal of the study was to identify any factors associated with attrition, Dr. Doumouras said.

“Predictors of interest included patient demographics – age, sex, income quintile, immigration status, employment status, smoking status – and comorbidities, such as diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, sleep apnea, and renal disease,” he said. “The study also evaluated health services factors, such as overall wait time to bariatric surgery, presence of centers of excellence, and health care utilization.”

The study found that demographics with more than twice the odds of attrition were male gender and presence of a disability (P less than .01). Smokers were 60% more likely to drop out (P less than .01), he said. “To receive bariatric surgery in Ontario, smokers must go through a smoking cessation program.”

Unemployed individuals and immigrants also had higher rates of attrition, at 55% and 39%, respectively, and were more likely to not go through with the operation (P less than .01). Health factors associated with attrition, but to a lesser extent, were diabetes (odds ratio, 1.23) and heart failure (OR, 1.35; P less than .01).

“Low socioeconomic status actually had a very low impact in our system on attrition after adjustment for other demographic factors such as disability and unemployment,” Dr. Doumouras said, noting a 16% greater risk of attrition in this group (P = .02).

“Interestingly,” he noted, “there was one factor associated with less dropout – obstructive sleep apnea – probably because people hate using the CPAP machines every single night.” People with OSA were 47% less likely to drop out than were people without the disease (P less than .001).

When asked if the findings would be applicable in the United States, Dr. Doumouras said they would to an extent.

“I think we can say confidently that they would apply to most universal health care systems,” he said. “In nonuniversal health care systems, the interplay between insurance status, socioeconomic status, and the like makes it more of a complex relationship, but if you were to take any kind of health care system, even in the United States, you would probably see very similar trends in terms of who can get bariatric surgery.”

He added, “I think also the length of work-up matters. Only a 3- or 4-week work-up probably affects attrition as well. These are relatively universal things.”

Dr. Doumouras has no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Doumouras A et al. SAGES 2019, Abstract S118.

BALTIMORE – Even in a public health system like Canada’s, almost and researchers have identified patient characteristics that could be predictive of dropout risk that would potentially have implications in a nonuniversal system, such as that of the United States, according to a study of almost 18,000 patients reported at the annual meeting Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons.

“Even in a universal health care system, clear disparities exist among patient populations having bariatric surgery,” said Aristithes Doumouras, MD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. “Extensive work-ups and long wait times can have an impact on the delivery of bariatric care.”

Dr. Doumouras reported on results of a retrospective, population-based study of 17,703 patients referred for surgery during 2009-2015 in the Ontario Bariatric Network, a province-wide network of 11 hospitals credentialed to perform bariatric surgery. The study found that 23.2% of patients referred for bariatric surgery did not go through with it and that overall average wait times between referral and the operation were just short of a year – 362.2 days to be precise.

The goal of the study was to identify any factors associated with attrition, Dr. Doumouras said.

“Predictors of interest included patient demographics – age, sex, income quintile, immigration status, employment status, smoking status – and comorbidities, such as diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, sleep apnea, and renal disease,” he said. “The study also evaluated health services factors, such as overall wait time to bariatric surgery, presence of centers of excellence, and health care utilization.”

The study found that demographics with more than twice the odds of attrition were male gender and presence of a disability (P less than .01). Smokers were 60% more likely to drop out (P less than .01), he said. “To receive bariatric surgery in Ontario, smokers must go through a smoking cessation program.”

Unemployed individuals and immigrants also had higher rates of attrition, at 55% and 39%, respectively, and were more likely to not go through with the operation (P less than .01). Health factors associated with attrition, but to a lesser extent, were diabetes (odds ratio, 1.23) and heart failure (OR, 1.35; P less than .01).

“Low socioeconomic status actually had a very low impact in our system on attrition after adjustment for other demographic factors such as disability and unemployment,” Dr. Doumouras said, noting a 16% greater risk of attrition in this group (P = .02).

“Interestingly,” he noted, “there was one factor associated with less dropout – obstructive sleep apnea – probably because people hate using the CPAP machines every single night.” People with OSA were 47% less likely to drop out than were people without the disease (P less than .001).

When asked if the findings would be applicable in the United States, Dr. Doumouras said they would to an extent.

“I think we can say confidently that they would apply to most universal health care systems,” he said. “In nonuniversal health care systems, the interplay between insurance status, socioeconomic status, and the like makes it more of a complex relationship, but if you were to take any kind of health care system, even in the United States, you would probably see very similar trends in terms of who can get bariatric surgery.”

He added, “I think also the length of work-up matters. Only a 3- or 4-week work-up probably affects attrition as well. These are relatively universal things.”

Dr. Doumouras has no financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Doumouras A et al. SAGES 2019, Abstract S118.

REPORTING FROM SAGES 2019

Severe OSA increases cardiovascular risk after surgery

Unrecognized severe obstructive sleep apnea is a risk factor for cardiovascular complications after major noncardiac surgery, according to a study published in JAMA.

The researchers state that perioperative mismanagement of obstructive sleep apnea can lead to serious medical consequences. “General anesthetics, sedatives, and postoperative analgesics are potent respiratory depressants that relax the upper airway dilator muscles and impair ventilatory response to hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Each of these events exacerbates [obstructive sleep apnea] and may predispose patients to postoperative cardiovascular complications,” said researchers who conducted the The Postoperative vascular complications in unrecognised Obstructive Sleep apnoea (POSA) study (NCT01494181).

They undertook a prospective observational cohort study involving 1,218 patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery, who were already considered at high risk of postoperative cardiovascular events – having, for example, a history of coronary artery disease, stroke, diabetes, or renal impairment. However, none had a prior diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea.

Preoperative sleep monitoring revealed that two-thirds of the cohort had unrecognized and untreated obstructive sleep apnea, including 11.2% with severe obstructive sleep apnea.

At 30 days after surgery, patients with obstructive sleep apnea had a 49% higher risk of the primary outcome of myocardial injury, cardiac death, heart failure, thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, or stroke, compared with those without obstructive sleep apnea.

However, this association was largely due to a significant 2.23-fold higher risk among patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea, while those with only moderate or mild sleep apnea did not show a significant increased risk of cardiovascular complications.

Patients in this study with severe obstructive sleep apnea had a 13-fold higher risk of cardiac death, 80% higher risk of myocardial injury, more than sixfold higher risk of heart failure, and nearly fourfold higher risk of atrial fibrillation.

Researchers also saw an association between obstructive sleep apnea and increased risk of infective outcomes, unplanned tracheal intubation, postoperative lung ventilation, and readmission to the ICU.

The majority of patients received nocturnal oximetry monitoring during their first 3 nights after surgery. This revealed that patients without obstructive sleep apnea had significant increases in oxygen desaturation index during their first night after surgery, while those with sleep apnea did not return to their baseline oxygen desaturation index until the third night after surgery.

“Despite a substantial decrease in ODI [oxygen desaturation index] with oxygen therapy in patients with OSA during the first 3 postoperative nights, supplemental oxygen did not modify the association between OSA and postoperative cardiovascular event,” wrote Matthew T.V. Chan, MD, of Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, and coauthors.

Given that the events were associated with longer durations of severe oxyhemoglobin desaturation, more aggressive interventions such as positive airway pressure or oral appliances may be required, they noted.

“However, high-level evidence demonstrating the effect of these measures on perioperative outcomes is lacking [and] further clinical trials are now required to test if additional monitoring or alternative interventions would reduce the risk,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund (Hong Kong), National Healthcare Group–Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, University Health Network Foundation, University of Malaya, Malaysian Society of Anaesthesiologists, Auckland Medical Research Foundation, and ResMed. One author declared grants from private industry and a patent pending on an obstructive sleep apnea risk questionnaire used in the study.

SOURCE: Chan M et al. JAMA 2019;321[18]:1788-98. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4783.

This study is large, prospective, and rigorous and adds important new information to the puzzle of the impact of sleep apnea on postoperative risk, Dennis Auckley, MD, and Stavros Memtsoudis, MD, wrote in an editorial accompanying this study. The study focused on predetermined clinically significant and measurable events, used standardized and objective sleep apnea testing, and attempted to control for many of the confounders that might have influenced outcomes.

The results suggest that obstructive sleep apnea should be recognized as a major perioperative risk factor, and it should receive the same attention and optimization efforts as comorbidities such as diabetes.

Dr. Auckley is from the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine at MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and Dr. Memtsoudis is clinical professor of anesthesiology at Cornell University, New York. These comments are adapted from an editorial (JAMA 2019;231[18]:1775-6). Both declared board and executive positions with the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine. Dr. Auckley declared research funding from Medtronic, and Dr. Memtsoudis declared personal fees from Teikoku and Sandoz.

This study is large, prospective, and rigorous and adds important new information to the puzzle of the impact of sleep apnea on postoperative risk, Dennis Auckley, MD, and Stavros Memtsoudis, MD, wrote in an editorial accompanying this study. The study focused on predetermined clinically significant and measurable events, used standardized and objective sleep apnea testing, and attempted to control for many of the confounders that might have influenced outcomes.

The results suggest that obstructive sleep apnea should be recognized as a major perioperative risk factor, and it should receive the same attention and optimization efforts as comorbidities such as diabetes.

Dr. Auckley is from the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine at MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and Dr. Memtsoudis is clinical professor of anesthesiology at Cornell University, New York. These comments are adapted from an editorial (JAMA 2019;231[18]:1775-6). Both declared board and executive positions with the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine. Dr. Auckley declared research funding from Medtronic, and Dr. Memtsoudis declared personal fees from Teikoku and Sandoz.

This study is large, prospective, and rigorous and adds important new information to the puzzle of the impact of sleep apnea on postoperative risk, Dennis Auckley, MD, and Stavros Memtsoudis, MD, wrote in an editorial accompanying this study. The study focused on predetermined clinically significant and measurable events, used standardized and objective sleep apnea testing, and attempted to control for many of the confounders that might have influenced outcomes.

The results suggest that obstructive sleep apnea should be recognized as a major perioperative risk factor, and it should receive the same attention and optimization efforts as comorbidities such as diabetes.

Dr. Auckley is from the division of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine at MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and Dr. Memtsoudis is clinical professor of anesthesiology at Cornell University, New York. These comments are adapted from an editorial (JAMA 2019;231[18]:1775-6). Both declared board and executive positions with the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine. Dr. Auckley declared research funding from Medtronic, and Dr. Memtsoudis declared personal fees from Teikoku and Sandoz.

Unrecognized severe obstructive sleep apnea is a risk factor for cardiovascular complications after major noncardiac surgery, according to a study published in JAMA.

The researchers state that perioperative mismanagement of obstructive sleep apnea can lead to serious medical consequences. “General anesthetics, sedatives, and postoperative analgesics are potent respiratory depressants that relax the upper airway dilator muscles and impair ventilatory response to hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Each of these events exacerbates [obstructive sleep apnea] and may predispose patients to postoperative cardiovascular complications,” said researchers who conducted the The Postoperative vascular complications in unrecognised Obstructive Sleep apnoea (POSA) study (NCT01494181).

They undertook a prospective observational cohort study involving 1,218 patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery, who were already considered at high risk of postoperative cardiovascular events – having, for example, a history of coronary artery disease, stroke, diabetes, or renal impairment. However, none had a prior diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea.

Preoperative sleep monitoring revealed that two-thirds of the cohort had unrecognized and untreated obstructive sleep apnea, including 11.2% with severe obstructive sleep apnea.

At 30 days after surgery, patients with obstructive sleep apnea had a 49% higher risk of the primary outcome of myocardial injury, cardiac death, heart failure, thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, or stroke, compared with those without obstructive sleep apnea.

However, this association was largely due to a significant 2.23-fold higher risk among patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea, while those with only moderate or mild sleep apnea did not show a significant increased risk of cardiovascular complications.

Patients in this study with severe obstructive sleep apnea had a 13-fold higher risk of cardiac death, 80% higher risk of myocardial injury, more than sixfold higher risk of heart failure, and nearly fourfold higher risk of atrial fibrillation.

Researchers also saw an association between obstructive sleep apnea and increased risk of infective outcomes, unplanned tracheal intubation, postoperative lung ventilation, and readmission to the ICU.

The majority of patients received nocturnal oximetry monitoring during their first 3 nights after surgery. This revealed that patients without obstructive sleep apnea had significant increases in oxygen desaturation index during their first night after surgery, while those with sleep apnea did not return to their baseline oxygen desaturation index until the third night after surgery.

“Despite a substantial decrease in ODI [oxygen desaturation index] with oxygen therapy in patients with OSA during the first 3 postoperative nights, supplemental oxygen did not modify the association between OSA and postoperative cardiovascular event,” wrote Matthew T.V. Chan, MD, of Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, and coauthors.

Given that the events were associated with longer durations of severe oxyhemoglobin desaturation, more aggressive interventions such as positive airway pressure or oral appliances may be required, they noted.

“However, high-level evidence demonstrating the effect of these measures on perioperative outcomes is lacking [and] further clinical trials are now required to test if additional monitoring or alternative interventions would reduce the risk,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund (Hong Kong), National Healthcare Group–Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, University Health Network Foundation, University of Malaya, Malaysian Society of Anaesthesiologists, Auckland Medical Research Foundation, and ResMed. One author declared grants from private industry and a patent pending on an obstructive sleep apnea risk questionnaire used in the study.

SOURCE: Chan M et al. JAMA 2019;321[18]:1788-98. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4783.

Unrecognized severe obstructive sleep apnea is a risk factor for cardiovascular complications after major noncardiac surgery, according to a study published in JAMA.

The researchers state that perioperative mismanagement of obstructive sleep apnea can lead to serious medical consequences. “General anesthetics, sedatives, and postoperative analgesics are potent respiratory depressants that relax the upper airway dilator muscles and impair ventilatory response to hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Each of these events exacerbates [obstructive sleep apnea] and may predispose patients to postoperative cardiovascular complications,” said researchers who conducted the The Postoperative vascular complications in unrecognised Obstructive Sleep apnoea (POSA) study (NCT01494181).

They undertook a prospective observational cohort study involving 1,218 patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery, who were already considered at high risk of postoperative cardiovascular events – having, for example, a history of coronary artery disease, stroke, diabetes, or renal impairment. However, none had a prior diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea.

Preoperative sleep monitoring revealed that two-thirds of the cohort had unrecognized and untreated obstructive sleep apnea, including 11.2% with severe obstructive sleep apnea.

At 30 days after surgery, patients with obstructive sleep apnea had a 49% higher risk of the primary outcome of myocardial injury, cardiac death, heart failure, thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, or stroke, compared with those without obstructive sleep apnea.

However, this association was largely due to a significant 2.23-fold higher risk among patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea, while those with only moderate or mild sleep apnea did not show a significant increased risk of cardiovascular complications.

Patients in this study with severe obstructive sleep apnea had a 13-fold higher risk of cardiac death, 80% higher risk of myocardial injury, more than sixfold higher risk of heart failure, and nearly fourfold higher risk of atrial fibrillation.

Researchers also saw an association between obstructive sleep apnea and increased risk of infective outcomes, unplanned tracheal intubation, postoperative lung ventilation, and readmission to the ICU.

The majority of patients received nocturnal oximetry monitoring during their first 3 nights after surgery. This revealed that patients without obstructive sleep apnea had significant increases in oxygen desaturation index during their first night after surgery, while those with sleep apnea did not return to their baseline oxygen desaturation index until the third night after surgery.

“Despite a substantial decrease in ODI [oxygen desaturation index] with oxygen therapy in patients with OSA during the first 3 postoperative nights, supplemental oxygen did not modify the association between OSA and postoperative cardiovascular event,” wrote Matthew T.V. Chan, MD, of Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, and coauthors.

Given that the events were associated with longer durations of severe oxyhemoglobin desaturation, more aggressive interventions such as positive airway pressure or oral appliances may be required, they noted.

“However, high-level evidence demonstrating the effect of these measures on perioperative outcomes is lacking [and] further clinical trials are now required to test if additional monitoring or alternative interventions would reduce the risk,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund (Hong Kong), National Healthcare Group–Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, University Health Network Foundation, University of Malaya, Malaysian Society of Anaesthesiologists, Auckland Medical Research Foundation, and ResMed. One author declared grants from private industry and a patent pending on an obstructive sleep apnea risk questionnaire used in the study.

SOURCE: Chan M et al. JAMA 2019;321[18]:1788-98. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4783.

FROM JAMA

Appendectomy linked to increased risk of subsequent Parkinson’s

.

“One of the factors that’s seen in the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease is accumulation of an abnormal protein known as alpha-synuclein,” one of the study authors, Gregory S. Cooper, MD, said during a media briefing in advance of the annual Digestive Disease Week. “It’s released by damaged nerve cells in the brain. Not only is alpha-synuclein found in the brain of patients with Parkinson’s disease; it’s also found in the GI tract. It’s thought that its accumulation in the GI tract occurs prior to the development of its accumulation in the brain.”

This has prompted scientists around the world to evaluate the GI tract, including the appendix, for evidence about the pathophysiology and onset of Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Cooper, professor of medicine, oncology, and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. “It’s thought that, potentially, in the presence of inflammation, [molecules] of this protein are released from damaged nerves in the gut and then are transported to the brain, where they accumulate,” he said. “Or, it could be that the appendix is a storage place for this protein and gets released at the time of appendectomy.”

To investigate if appendectomy increases the risk of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Cooper and colleagues drew from the Explorys database, which contains EHRs from 26 integrated U.S. health care systems. They limited their search to patients who underwent appendectomies and those who were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease based on Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terms. The researchers chose a washout period of 6 months to the development of Parkinson’s disease after appendectomy, and compared the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in the general population to those with appendectomies.

Of the 62,218,050 records in the database, Dr. Cooper and colleagues identified 488,190 patients who underwent appendectomies. In all, 4,470 cases of Parkinson’s disease were observed in patients with appendectomies, and 177,230 cases of Parkinson’s disease in patients without appendectomies. The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomies was 3.19 (95% confidence interval, 3.10-3.28; P less than .0001), compared with those who did not undergo the procedure. The relative risk was higher in patients aged 18-64 years (RR, 4.27; 95% CI, 3.99-4.57; P less than .0001), compared with those 65 years and older (RR, 2.20; 95% CI, 2.13-2.27; P less than .0001). “We know that Parkinson’s disease is more common in the elderly,” Dr. Cooper said. “But at virtually all ages, the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease was higher in patients who had an appendectomy, compared to those without an appendectomy.”

The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomies was slightly higher in females (RR, 3.86; 95% CI, 3.71-4.02; P less than .0001), compared with males (RR, 2.67; 95% CI, 2.56-2.79; P less than .0001). The researchers also observed a similar effect of appendectomy by race. The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomy was slightly higher in African Americans (RR, 3.11; 95% CI, 2.69-3.58; P less than .0001), compared with Asians (RR, 2.73; 95% CI, 2.19-3.41; P less than .0001), and whites (RR, 2.55; 95% CI, 2.48-2.63; P less than .0001).

“If these data get borne out, it may question the role of doing a discretionary appendectomy in a patient who’s having surgery for another reason,” Dr. Cooper said. “Our research does show a clear relationship between appendectomy and Parkinson’s disease. However, at this point, it’s only an association. As a next step, we’d like to conduct additional research to confirm this connection and better understand the mechanisms involved.”

He pointed out that, because of the nature of the Explorys database, he and his colleagues were unable to determine the length of time following appendectomy to the development of Parkinson’s disease.

The study’s lead author was Mohammed Z. Sheriff, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sheriff MZ et al. DDW 2019, Abstract 739.

.

“One of the factors that’s seen in the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease is accumulation of an abnormal protein known as alpha-synuclein,” one of the study authors, Gregory S. Cooper, MD, said during a media briefing in advance of the annual Digestive Disease Week. “It’s released by damaged nerve cells in the brain. Not only is alpha-synuclein found in the brain of patients with Parkinson’s disease; it’s also found in the GI tract. It’s thought that its accumulation in the GI tract occurs prior to the development of its accumulation in the brain.”

This has prompted scientists around the world to evaluate the GI tract, including the appendix, for evidence about the pathophysiology and onset of Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Cooper, professor of medicine, oncology, and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. “It’s thought that, potentially, in the presence of inflammation, [molecules] of this protein are released from damaged nerves in the gut and then are transported to the brain, where they accumulate,” he said. “Or, it could be that the appendix is a storage place for this protein and gets released at the time of appendectomy.”

To investigate if appendectomy increases the risk of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Cooper and colleagues drew from the Explorys database, which contains EHRs from 26 integrated U.S. health care systems. They limited their search to patients who underwent appendectomies and those who were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease based on Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terms. The researchers chose a washout period of 6 months to the development of Parkinson’s disease after appendectomy, and compared the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in the general population to those with appendectomies.

Of the 62,218,050 records in the database, Dr. Cooper and colleagues identified 488,190 patients who underwent appendectomies. In all, 4,470 cases of Parkinson’s disease were observed in patients with appendectomies, and 177,230 cases of Parkinson’s disease in patients without appendectomies. The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomies was 3.19 (95% confidence interval, 3.10-3.28; P less than .0001), compared with those who did not undergo the procedure. The relative risk was higher in patients aged 18-64 years (RR, 4.27; 95% CI, 3.99-4.57; P less than .0001), compared with those 65 years and older (RR, 2.20; 95% CI, 2.13-2.27; P less than .0001). “We know that Parkinson’s disease is more common in the elderly,” Dr. Cooper said. “But at virtually all ages, the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease was higher in patients who had an appendectomy, compared to those without an appendectomy.”

The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomies was slightly higher in females (RR, 3.86; 95% CI, 3.71-4.02; P less than .0001), compared with males (RR, 2.67; 95% CI, 2.56-2.79; P less than .0001). The researchers also observed a similar effect of appendectomy by race. The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomy was slightly higher in African Americans (RR, 3.11; 95% CI, 2.69-3.58; P less than .0001), compared with Asians (RR, 2.73; 95% CI, 2.19-3.41; P less than .0001), and whites (RR, 2.55; 95% CI, 2.48-2.63; P less than .0001).

“If these data get borne out, it may question the role of doing a discretionary appendectomy in a patient who’s having surgery for another reason,” Dr. Cooper said. “Our research does show a clear relationship between appendectomy and Parkinson’s disease. However, at this point, it’s only an association. As a next step, we’d like to conduct additional research to confirm this connection and better understand the mechanisms involved.”

He pointed out that, because of the nature of the Explorys database, he and his colleagues were unable to determine the length of time following appendectomy to the development of Parkinson’s disease.

The study’s lead author was Mohammed Z. Sheriff, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sheriff MZ et al. DDW 2019, Abstract 739.

.

“One of the factors that’s seen in the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease is accumulation of an abnormal protein known as alpha-synuclein,” one of the study authors, Gregory S. Cooper, MD, said during a media briefing in advance of the annual Digestive Disease Week. “It’s released by damaged nerve cells in the brain. Not only is alpha-synuclein found in the brain of patients with Parkinson’s disease; it’s also found in the GI tract. It’s thought that its accumulation in the GI tract occurs prior to the development of its accumulation in the brain.”

This has prompted scientists around the world to evaluate the GI tract, including the appendix, for evidence about the pathophysiology and onset of Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Cooper, professor of medicine, oncology, and population and quantitative health sciences at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. “It’s thought that, potentially, in the presence of inflammation, [molecules] of this protein are released from damaged nerves in the gut and then are transported to the brain, where they accumulate,” he said. “Or, it could be that the appendix is a storage place for this protein and gets released at the time of appendectomy.”

To investigate if appendectomy increases the risk of Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Cooper and colleagues drew from the Explorys database, which contains EHRs from 26 integrated U.S. health care systems. They limited their search to patients who underwent appendectomies and those who were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease based on Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terms. The researchers chose a washout period of 6 months to the development of Parkinson’s disease after appendectomy, and compared the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in the general population to those with appendectomies.

Of the 62,218,050 records in the database, Dr. Cooper and colleagues identified 488,190 patients who underwent appendectomies. In all, 4,470 cases of Parkinson’s disease were observed in patients with appendectomies, and 177,230 cases of Parkinson’s disease in patients without appendectomies. The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomies was 3.19 (95% confidence interval, 3.10-3.28; P less than .0001), compared with those who did not undergo the procedure. The relative risk was higher in patients aged 18-64 years (RR, 4.27; 95% CI, 3.99-4.57; P less than .0001), compared with those 65 years and older (RR, 2.20; 95% CI, 2.13-2.27; P less than .0001). “We know that Parkinson’s disease is more common in the elderly,” Dr. Cooper said. “But at virtually all ages, the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease was higher in patients who had an appendectomy, compared to those without an appendectomy.”

The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomies was slightly higher in females (RR, 3.86; 95% CI, 3.71-4.02; P less than .0001), compared with males (RR, 2.67; 95% CI, 2.56-2.79; P less than .0001). The researchers also observed a similar effect of appendectomy by race. The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomy was slightly higher in African Americans (RR, 3.11; 95% CI, 2.69-3.58; P less than .0001), compared with Asians (RR, 2.73; 95% CI, 2.19-3.41; P less than .0001), and whites (RR, 2.55; 95% CI, 2.48-2.63; P less than .0001).

“If these data get borne out, it may question the role of doing a discretionary appendectomy in a patient who’s having surgery for another reason,” Dr. Cooper said. “Our research does show a clear relationship between appendectomy and Parkinson’s disease. However, at this point, it’s only an association. As a next step, we’d like to conduct additional research to confirm this connection and better understand the mechanisms involved.”

He pointed out that, because of the nature of the Explorys database, he and his colleagues were unable to determine the length of time following appendectomy to the development of Parkinson’s disease.

The study’s lead author was Mohammed Z. Sheriff, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sheriff MZ et al. DDW 2019, Abstract 739.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2019

Key clinical point: Appendectomy appears to increase the risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Major finding: The overall relative risk of developing Parkinson’s disease in patients after appendectomy was 3.19 (95% CI, 3.10-3.28; P less than .0001), compared with those who did not undergo the procedure.

Study details: A population-based study of more than 62 million medical records from a national database.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Sheriff MZ et al. DDW 2019, Abstract 739.

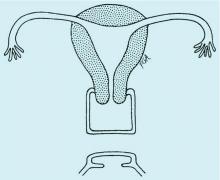

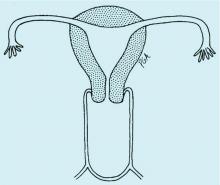

Managing 2nd trimester loss: Shared decision making, honor patient preference

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to Sara W. Prager, MD.

Information transfer between the physician and patient, as opposed to a provider-driven or patient-driven decision-making process, better ensures that “the best possible decision” will be reached, Dr. Prager, director of the family planning division and family planning fellowship at the University of Washington in Seattle, said at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Engaging the patient in the process – actively involving and supporting her in health care and treatment decision-making activities – is critically important, especially when dealing with pregnancy loss, which involves an acute sense of powerlessness, she said. Patient engagement is essential for respecting her autonomy, enhancing her agency, improving health status, reducing decisional conflict, and improving overall satisfaction.

Shared decision making requires a discussion about how the two approaches compare, particularly with respect to specific complications associated with each, Dr. Prager said, noting that discussion of values also should be encouraged.

Although surgical management is used more often, both approaches are safe and effective, and in the absence of clear contraindications in settings where both medication and a practitioner skilled in dilatation and evacuation are available, patient preference should honored, she said.

In this video interview, Dr. Prager further explains her position. “Using evidence-based medicine to have a shared decision-making process ... is extremely helpful for patients to feel like they have some control in this out-of-control situation where they’re experiencing a pregnancy loss.”

She also discussed how the use of mifepristone plus misoprostol for medical management of second-trimester loss has the potential to improve access.

“This is medication that, because of stigma surrounding abortion, is not always available ... so actually using it for non–abortion-related activities can be a way to help reduce that stigma around the medication itself, and get it into clinical sites, because it really does meaningfully improve management in the second trimester, as well as in the first trimester.”

In fact, the combination can cut nearly in half the amount of time it takes from the start of an induction until the end of the induction process, she said.

Dr. Prager also discussed surgical training resources and how to advocate for patient access to family planning experts who have the appropriate training.

Dr. Prager said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to Sara W. Prager, MD.

Information transfer between the physician and patient, as opposed to a provider-driven or patient-driven decision-making process, better ensures that “the best possible decision” will be reached, Dr. Prager, director of the family planning division and family planning fellowship at the University of Washington in Seattle, said at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Engaging the patient in the process – actively involving and supporting her in health care and treatment decision-making activities – is critically important, especially when dealing with pregnancy loss, which involves an acute sense of powerlessness, she said. Patient engagement is essential for respecting her autonomy, enhancing her agency, improving health status, reducing decisional conflict, and improving overall satisfaction.

Shared decision making requires a discussion about how the two approaches compare, particularly with respect to specific complications associated with each, Dr. Prager said, noting that discussion of values also should be encouraged.

Although surgical management is used more often, both approaches are safe and effective, and in the absence of clear contraindications in settings where both medication and a practitioner skilled in dilatation and evacuation are available, patient preference should honored, she said.

In this video interview, Dr. Prager further explains her position. “Using evidence-based medicine to have a shared decision-making process ... is extremely helpful for patients to feel like they have some control in this out-of-control situation where they’re experiencing a pregnancy loss.”

She also discussed how the use of mifepristone plus misoprostol for medical management of second-trimester loss has the potential to improve access.

“This is medication that, because of stigma surrounding abortion, is not always available ... so actually using it for non–abortion-related activities can be a way to help reduce that stigma around the medication itself, and get it into clinical sites, because it really does meaningfully improve management in the second trimester, as well as in the first trimester.”

In fact, the combination can cut nearly in half the amount of time it takes from the start of an induction until the end of the induction process, she said.

Dr. Prager also discussed surgical training resources and how to advocate for patient access to family planning experts who have the appropriate training.

Dr. Prager said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to Sara W. Prager, MD.

Information transfer between the physician and patient, as opposed to a provider-driven or patient-driven decision-making process, better ensures that “the best possible decision” will be reached, Dr. Prager, director of the family planning division and family planning fellowship at the University of Washington in Seattle, said at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Engaging the patient in the process – actively involving and supporting her in health care and treatment decision-making activities – is critically important, especially when dealing with pregnancy loss, which involves an acute sense of powerlessness, she said. Patient engagement is essential for respecting her autonomy, enhancing her agency, improving health status, reducing decisional conflict, and improving overall satisfaction.

Shared decision making requires a discussion about how the two approaches compare, particularly with respect to specific complications associated with each, Dr. Prager said, noting that discussion of values also should be encouraged.

Although surgical management is used more often, both approaches are safe and effective, and in the absence of clear contraindications in settings where both medication and a practitioner skilled in dilatation and evacuation are available, patient preference should honored, she said.

In this video interview, Dr. Prager further explains her position. “Using evidence-based medicine to have a shared decision-making process ... is extremely helpful for patients to feel like they have some control in this out-of-control situation where they’re experiencing a pregnancy loss.”

She also discussed how the use of mifepristone plus misoprostol for medical management of second-trimester loss has the potential to improve access.

“This is medication that, because of stigma surrounding abortion, is not always available ... so actually using it for non–abortion-related activities can be a way to help reduce that stigma around the medication itself, and get it into clinical sites, because it really does meaningfully improve management in the second trimester, as well as in the first trimester.”

In fact, the combination can cut nearly in half the amount of time it takes from the start of an induction until the end of the induction process, she said.

Dr. Prager also discussed surgical training resources and how to advocate for patient access to family planning experts who have the appropriate training.

Dr. Prager said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACOG 2019

Time to embrace minimally invasive colorectal surgery?

LAS VEGAS – Two-thirds of colon resections in the United States are open procedures, but a colorectal surgeon told colleagues that evidence shows minimally invasive surgery deserves a wider place in his field.

Why? Because minimally invasive surgery – despite its limited utilization – is linked to multiple improved outcomes in colorectal surgery, said Matthew G. Mutch, MD, chief of colon and rectal surgery at Washington University, St. Louis, in a presentation at the Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Our goal should be to offer minimally invasive surgery to as many patients as possible by as many different methods as needed,” Dr. Mutch said. “If you’re willing to take this on and do this over a regular basis, you’ll get over that learning curve and expand the number of patients you can offer laparoscopy to.”

According to Dr. Mutch, benefits of minimally invasive colorectal surgery include:

- Improved short-term outcomes – length of stay and return of bowel function, and morbidity and mortality. A 2012 retrospective study of 85,712 colon resections that found laparoscopic resections, when feasible, “had better outcomes than open colectomy in the immediate perioperative period.” (Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256[3]462-8).

- Improved long-term outcomes: faster recovery, fewer hernias, and fewer bowel obstructions.

- Lower overall costs.

- Fewer complications in the elderly.

When it comes to laparoscopic colorectal surgery, Dr. Mutch cautioned that the robotic technology has unclear benefit in rectal cancer, and the cost in colorectal cancer is unclear.

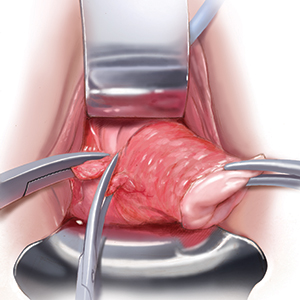

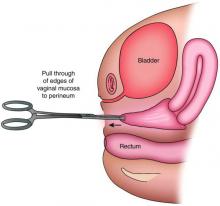

Another alternative is to perform laparoscopic colorectal surgery through alternative extraction sites such as the rectum, vagina, stomach, and even a stoma site or perineal wound. Both transanal and transvaginal extraction are feasible and safe, he said, adding that transvaginal procedures are best performed in conjunction with a hysterectomy. One benefit of these procedures is that they avoid abdominal wall trauma. However, he cautioned that colorectal surgery is unique because a cancerous specimen cannot be morcellated and must instead be removed whole.

Dr. Mutch also discussed laparoendoscopic resection of colon polyps. Benefits include shorter length of stay and faster recovery, he said, but complications can include perforation and bleeding. And, he said, there’s currently no code for the procedure.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Mutch has no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Two-thirds of colon resections in the United States are open procedures, but a colorectal surgeon told colleagues that evidence shows minimally invasive surgery deserves a wider place in his field.

Why? Because minimally invasive surgery – despite its limited utilization – is linked to multiple improved outcomes in colorectal surgery, said Matthew G. Mutch, MD, chief of colon and rectal surgery at Washington University, St. Louis, in a presentation at the Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Our goal should be to offer minimally invasive surgery to as many patients as possible by as many different methods as needed,” Dr. Mutch said. “If you’re willing to take this on and do this over a regular basis, you’ll get over that learning curve and expand the number of patients you can offer laparoscopy to.”

According to Dr. Mutch, benefits of minimally invasive colorectal surgery include:

- Improved short-term outcomes – length of stay and return of bowel function, and morbidity and mortality. A 2012 retrospective study of 85,712 colon resections that found laparoscopic resections, when feasible, “had better outcomes than open colectomy in the immediate perioperative period.” (Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256[3]462-8).

- Improved long-term outcomes: faster recovery, fewer hernias, and fewer bowel obstructions.

- Lower overall costs.

- Fewer complications in the elderly.

When it comes to laparoscopic colorectal surgery, Dr. Mutch cautioned that the robotic technology has unclear benefit in rectal cancer, and the cost in colorectal cancer is unclear.

Another alternative is to perform laparoscopic colorectal surgery through alternative extraction sites such as the rectum, vagina, stomach, and even a stoma site or perineal wound. Both transanal and transvaginal extraction are feasible and safe, he said, adding that transvaginal procedures are best performed in conjunction with a hysterectomy. One benefit of these procedures is that they avoid abdominal wall trauma. However, he cautioned that colorectal surgery is unique because a cancerous specimen cannot be morcellated and must instead be removed whole.

Dr. Mutch also discussed laparoendoscopic resection of colon polyps. Benefits include shorter length of stay and faster recovery, he said, but complications can include perforation and bleeding. And, he said, there’s currently no code for the procedure.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Mutch has no relevant disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Two-thirds of colon resections in the United States are open procedures, but a colorectal surgeon told colleagues that evidence shows minimally invasive surgery deserves a wider place in his field.

Why? Because minimally invasive surgery – despite its limited utilization – is linked to multiple improved outcomes in colorectal surgery, said Matthew G. Mutch, MD, chief of colon and rectal surgery at Washington University, St. Louis, in a presentation at the Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Our goal should be to offer minimally invasive surgery to as many patients as possible by as many different methods as needed,” Dr. Mutch said. “If you’re willing to take this on and do this over a regular basis, you’ll get over that learning curve and expand the number of patients you can offer laparoscopy to.”

According to Dr. Mutch, benefits of minimally invasive colorectal surgery include:

- Improved short-term outcomes – length of stay and return of bowel function, and morbidity and mortality. A 2012 retrospective study of 85,712 colon resections that found laparoscopic resections, when feasible, “had better outcomes than open colectomy in the immediate perioperative period.” (Ann Surg. 2012 Sep;256[3]462-8).

- Improved long-term outcomes: faster recovery, fewer hernias, and fewer bowel obstructions.

- Lower overall costs.

- Fewer complications in the elderly.

When it comes to laparoscopic colorectal surgery, Dr. Mutch cautioned that the robotic technology has unclear benefit in rectal cancer, and the cost in colorectal cancer is unclear.

Another alternative is to perform laparoscopic colorectal surgery through alternative extraction sites such as the rectum, vagina, stomach, and even a stoma site or perineal wound. Both transanal and transvaginal extraction are feasible and safe, he said, adding that transvaginal procedures are best performed in conjunction with a hysterectomy. One benefit of these procedures is that they avoid abdominal wall trauma. However, he cautioned that colorectal surgery is unique because a cancerous specimen cannot be morcellated and must instead be removed whole.

Dr. Mutch also discussed laparoendoscopic resection of colon polyps. Benefits include shorter length of stay and faster recovery, he said, but complications can include perforation and bleeding. And, he said, there’s currently no code for the procedure.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Mutch has no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MISS

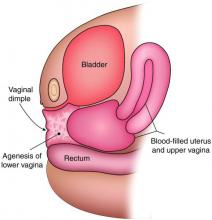

Energy-based therapies in female genital cosmetic surgery: Hype, hope, and a way forward

Energy-based therapy use in gynecology dates back to the early 1970s, when ablative carbon dioxide (C02) lasers were employed to treat cervical erosions.1 Soon after, reports were published on laser treatment for diethylstilbestrol-associated vaginal adenosis, laser laparoscopy for adhesiolysis, laser hysteroscopy, and laser genital wart ablation.2 Starting around 2011, the first articles were published on the use of fractional C02 laser treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy.3,4 Use of laser and light-based therapies to treat “vaginal rejuvenation” is now increasing at an annual rate of 26%. In a few years, North America is expected to be the largest market for vaginal laser rejuvenation. In 2016, more than 500,000 feminine rejuvenation procedures were performed in the United States, and it is estimated that more than 27,000 energy-based devices will be in operation by 2021.5

Clearly, there is considerable public interest and intrigue in office-based female genital cosmetic procedures. In 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration contacted 7 manufacturers of energy-based devices to request revision and clarification for marketing of these devices, since these technologies are neither cleared nor approved for cosmetic vulvovaginal conditions.6 The companies responded within 30 days.

In this article, we appraise the existing literature regarding the mechanism of action of energy-based therapies used in gynecology and review outcomes of their use in female genital cosmetic surgery.

Laser technology devices and how they work

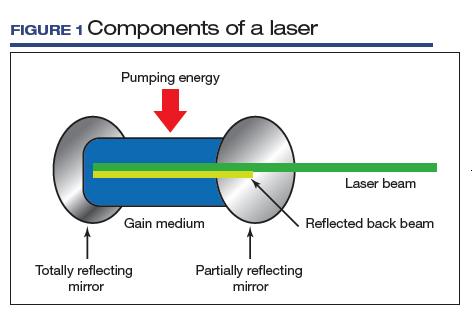

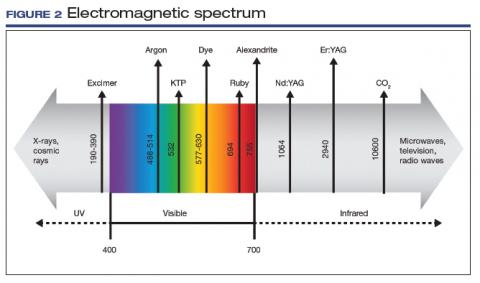

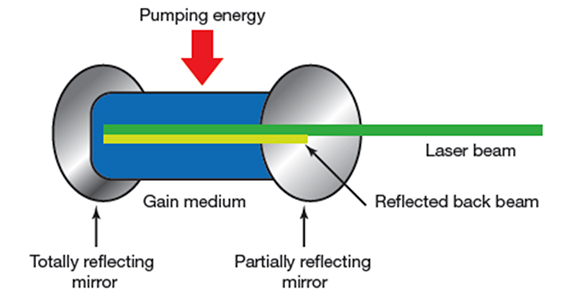

LASER is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Laser devices are composed of 1) an excitable medium (gas, liquid, solid) needed to emit light, 2) an energy source to excite the medium, 3) mirrors to bounce the light back and forth, and 4) a delivery and cooling system (FIGURE 1).

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all the wavelengths of light, including visible light, radio waves, infrared light, ultraviolet light, x-rays, and gamma rays (FIGURE 2). Most lasers used for the treatment of vulvovaginal disorders, typically C02 and erbium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) lasers, involve the infrared wavelengths.

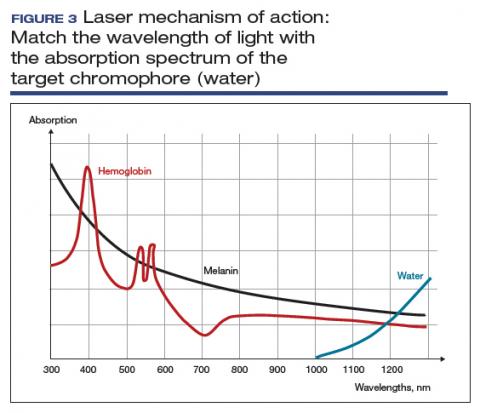

The basic principle of laser treatment is to match the wavelength of the laser with the absorption spectrum of the desired target—a chromophore such as hemoglobin, melanin, or water (FIGURE 3). In essence, light is absorbed by the chromophore (which in vulvar and vaginal tissues is mostly water) and transformed into heat, leading to target destruction. In a fractionated (or fractional) laser beam, the laser is broken up into many smaller beams that treat only portions of the treatment area, with areas of intact epithelium in between the treated areas. At appropriately low thermal denaturation temperatures (45° to 50°C), tissue regeneration can occur through activation of heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors, creating neocollagenesis and neovascularization.

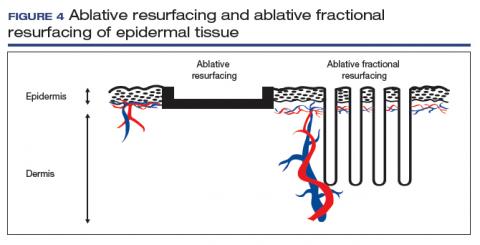

The concept of ablative resurfacing versus fractional resurfacing is borrowed from dermatology (FIGURE 4), understanding that tissue ablation and thermal denaturation occur at temperatures greater than 100°C, as occurs with carbonization of vulvar condylomata.

Continue to: In dermatology, fractionated lasers...

In dermatology, fractionated lasers have been used in the treatment of hair removal, vascular and pigmented lesions, scars, wound healing, tattoo removal, warts, and actinic keratoses. For these conditions, the targeted chromophores are water, hemoglobin, melanosomes, and tattoo ink. The laser pulses must be shorter than the target tissue thermal relaxation times in order to avoid excess heating and collateral tissue damage. Choosing appropriate settings is critical to achieve selective heating, or destruction, of the target tissue. These settings include appropriate wavelengths, pulse durations, and fluence, which is energy delivered per unit area (typically, joules per square centimeter).

For gynecologic conditions, the lasers used are most often CO2, Er:YAG, and hybrid (which include ablative and nonablative wavelengths) devices. In the epithelium of the vagina and vulva, these lasers generally have a very shallow depth of optical penetration, on the order of 10 to 200 µm.

Radiofrequency-based devices emit focused electromagnetic waves

Radiofrequency systems use a wand to deliver radiofrequency energy to create heat within the subepithelial layers of vulvar and vaginal tissues, while the surface remains cool. These devices can use monopolar or bipolar energy (current) to create a reverse thermal gradient designed to heat the deeper tissues transepithelially at a higher temperature while a coolant protects the surface epithelium. Some wand technologies require multiple treatments, while others require only a single treatment.

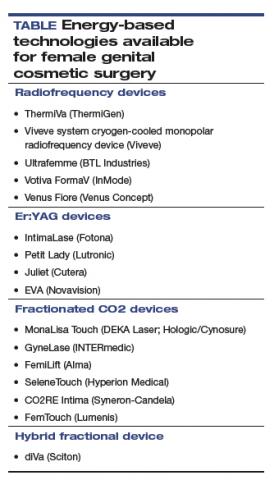

The TABLE lists currently available energy-based technologies.

Therapeutic uses for energy-based devices

Investigators have studied laser devices for treating various gynecologic conditions, including vulvovaginal atrophy, stress urinary incontinence (UI), vaginal laxity, lichen sclerosus, and vulvodynia.

Vulvovaginal atrophy

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) includes symptoms of vulvovaginal irritation, burning, itching, discharge, dyspareunia, lower urinary tract symptoms such as frequency and urinary tract infections, and vaginal dryness or vulvovaginal atrophy.7 First-line treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy includes the use of nonhormonal lubricants for intercourse and vaginal moisturizers, which temporarily moisten the vaginal epithelium. Low-dose vaginal estrogen is a second-line therapy for symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy; newer pharmacologic options include dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories (prasterone), solubilized estradiol capsules, and the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) ospemifene.

Fractionated CO2, Erb:YAG, and hybrid lasers also have been used to treat women with symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy and GSM through similar mechanisms described in dermatologic conditions with low-temperature laser activation of tissue proteins and growth factors creating new connective tissue and angiogenesis. A number of landmark studies have been published detailing patient outcomes with energy-based treatments for these symptoms.

Three-arm trial. Cruz and colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser vaginal treatment compared with local estriol therapy and the combination of laser plus estriol.8 The investigators randomly assigned 45 postmenopausal women to treatment with fractional CO2 laser with placebo vaginal cream, estriol with sham laser, or laser plus estriol. Treatment consisted of 2 sessions 4 weeks apart, with 20 consecutive weeks of estriol or placebo 3 times per week.

At weeks 8 and 20, the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) average score was significantly higher in all study arms. At week 20, the laser plus estriol group also showed incremental improvement in the VHI score (P = .01). The laser and the laser plus estriol groups had significant improvement in dyspareunia, burning, and dryness, while the estriol group improved only in dryness (P<.001). The laser plus estriol group had significant improvement in the total Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) score (P = .02) and in the individual domains of pain, desire, and lubrication. Although the laser-alone group had significant worsening in the FSFI pain domain (P = .04), all treatment arms had comparable FSFI total scores at week 20. No adverse events were recorded during the study period.

Continue to: Retrospective study...

Retrospective study. To assess the efficacy of 3, 4, or 5 treatments with microablative fractional CO2 laser therapy for symptoms of GSM, Athanasiou and colleagues studied outcomes in 94 postmenopausal women.9 The intensity or bothersomeness of GSM symptoms as well as sexual function significantly improved in this cohort. The intensity of dyspareunia and dryness decreased from a median of 9 (minimum–maximum, 5–10) and 8 (0–10), respectively, at baseline to 0 (0–6) and 0 (0–8) at 1 month after the last laser therapy (P<.001 for all). The FSFI score and the frequency of sexual intercourse rose from 10.8 (2–26.9) and 1 (0–8) at baseline to 27.8 (15.2–35.4) and 4 (2–8) at 1 month after the last laser therapy (P<.001 for all).

The positive effects of laser therapy were unchanged throughout the 12 months of follow-up, and the pattern was the same for symptom-free rates. No adverse events were recorded during the study period.

The investigators noted that, based on short- and long-term follow-up, 4 or 5 laser treatments may be superior to 3 treatments for lowering the intensity of GSM symptoms. They found no differences in outcomes between 4 and 5 laser treatments.

Prospective comparative cohort study. Gaspar and colleagues recruited 50 postmenopausal women with GSM and assigned 25 participants to 2 weeks of pretreatment with estriol ovules 3 times per week (for epithelial hydration) followed by 3 sessions of Er:YAG nonablative laser treatments; 25 women in the active control group received treatment with estriol ovules over 8 weeks.10 Pre- and posttreatment biopsies, maturation index, maturation value, pH, and VAS symptom analysis were recorded up to 18 months after treatment.

Up to the 6-month follow-up, both treatment groups had a statistically significant reduction of all GSM symptoms. At all follow-ups, however, symptom relief was more prominent in the laser-treated group. In addition, the effects of the laser therapy remained statistically significant at the 12- and 18-month follow-ups, while the treatment effects of estriol were diminished at 12 months and, at 18 months, this group had some symptoms that were significantly worse than before treatment.

Overall, adverse effects were minimal and transient in both groups, affecting 4% of participants in the laser group, and 12% in the estriol group.

Long-term effectiveness evaluation. To assess the long-term efficacy and acceptability of vaginal laser treatment for the management of GSM, Gambacciani and colleagues treated 205 postmenopausal women with an Er:YAG laser for 3 applications every 30 days, with evaluations performed after 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months from the last laser treatment.11 An active control group (n = 49) received 3 months of local treatment with either hormonal (estriol gel twice weekly) or nonhormonal (hyaluronic acid-based preparations or moisturizers and lubricants) agents.

Treatment with the ER:YAG laser induced a significant decrease (P<.01) in scores of the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for vulvovaginal atrophy symptoms for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia and an increase in the VHI score (P<.01) up to 12 months after the last treatment. After 18 and 24 months, values returned to levels similar to those at baseline.

Women who also had stress UI (n = 114) received additional laser treatment of the anterior vaginal wall specifically designed for UI, with assessment based on the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF). Laser treatment induced a significant decrease (P<.05) in ICIQ-UI SF scores compared with baseline values, and scores remained lower than baseline values after 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after the last laser treatment. Values measured after 18 and 24 months, however, did not differ significantly from baseline.

In the control group, the VAS score showed a similar decrease and comparable pattern during the treatment period. However, after the end of the treatment period, the control group’s VAS scores for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia showed a progressive increase, and after 6 months, the values were significantly different from corresponding values measured in the laser therapy group. The follow-up period in the control group ended after 6 months, because almost all patients started a new local or systemic treatment for their GSM symptoms. No adverse events related to treatment were recorded throughout the study period.

In an earlier pilot study by the same authors, 19 women with GSM who also had mild to moderate stress UI were treated with a vaginal Er:YAG laser.12 Compared with vaginal estriol treatment in the active control group, laser treatment was associated with a significant improvement (P<.01) in ICIQ-SF scores, with rapid and long-lasting effects that persisted up to week 24 of the observation period.

Continue to: Urinary incontinence...

Urinary incontinence

The cause of UI is considered to be multifactorial, including disruption in connective tissue supports of the urethrovesical junction leading to urethral hypermobility, pelvic floor muscle weakness, nerve damage to the urethral rhabdosphincter related to pudendal neuropathy or pelvic plexopathy, and atrophic changes of the urethra mucosa and submucosa. Purported mechanisms of action for energy-based therapies designed for treatment of UI relate to direct effects on connective tissue, blood vessels, and possibly nerves.

In 3 clinical trials designed specifically to treat UI with an Er:YAG laser, women showed subjective symptomatic improvement.

Ogrinc and colleagues followed 175 pre- and postmenopausal women with stress UI or mixed UI in a prospective nonrandomized study.13 They treated women with an Er:YAG laser for an average of 2.5 (0.5) procedures separated by a 2-month period and performed follow-up assessments at 2, 6, and 12 months after treatment.

After treatment, 77% of women with stress UI had significant improvement in symptoms based on the ICIQ SF and the Incontinence Severity Index (ISI), while only 34% of those with mixed UI had no symptoms at 1-year follow-up. No major adverse effects were noted in either group.

Okui compared the effects of Er:YAG laser treatment with those of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) or transobturator tape (TOT) sling procedures (n = 50 in each group) in women with stress UI or mixed UI.14 At 12 months after treatment, all 3 treatments demonstrated comparable improvements in the women with stress UI. Some patients with mixed UI in the TVT and TOT groups showed exacerbation, while all women in the laser-treated group tended to have symptom improvement.

In another recent study, Blaganje and colleagues randomly assigned 114 premenopausal parous women with stress UI to an Er:YAG laser procedure or sham treatment.15 Three months after treatment, ICIQ-UI SF scores were significantly more improved (P<.001) in the laser-treated group than in the sham group. In addition, 21% of laser-treated patients were dry at follow-up compared with 4% of the sham-treated group.

Key takeaway. While these studies showed promising short-term results for laser treatment of UI, they need to be replicated in appropriately powered clinical trials that include critical subjective and objective outcomes as well as longer-term follow-up for both effectiveness and safety.

Vaginal laxity/pre-prolapse

Vaginal laxity is defined as the symptom of excessive vaginal looseness.16 Also referred to as “pre-prolapse,” this subjective symptom generally refers to a widened vaginal opening (genital hiatus) but with pelvic organ prolapse that is within the vagina or hymen.17 Notably, the definition is ambiguous, and rigorous clinical data based on validated outcomes and prolapse grading are lacking.

Krychman and colleagues conducted the first randomized controlled study comparing monopolar radiofrequency at the vaginal introitus with sham therapy for vaginal laxity in 174 premenopausal women, known as the VIVEVE I trial.18 The primary outcome, the proportion of women reporting no vaginal laxity at 6 months after treatment, was assessed using a vaginal laxity questionnaire, a 7-point rating scale for laxity or tightness ranging from very loose to very tight. With a single radiofrequency treatment, 43.5% of the active group and 19.6% (P = .002) of the sham group obtained the primary outcome.

There were also statistically significant improvements in overall sexual function and decreased sexual distress. The adjusted odds ratio (OR, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 1.54–7.45) showed that the likelihood of no vaginal laxity at 6 months was more than 3 times greater for women who received the active treatment compared with those who received sham treatment. Adverse events were mild, resolved spontaneously, and were similar in the 2 groups.

Continue to: Outlook for energy-based...

Outlook for energy-based therapies: Cautiously optimistic

Preliminary outcome data on the use of energy-based therapies for female genital cosmetic surgery is largely positive for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy, but some case series suggest the potential for scarring, burning, and inefficacy. This prompted the FDA to send “It has come to our attention” letters to a number of device manufacturers in 2018.6

Supportive evidence is weak. Early data are encouraging regarding fractionated laser therapy for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and stress UI and radiofrequency wand therapy for vaginal laxity and stress UI. Unfortunately, the level of evidence to support wide use of these technologies for all pelvic floor disorders is weak. A recent committee opinion from the International Urogynecology Association noted that only 8 studies (1 randomized trial and 7 observational studies) on these conditions fulfilled the criteria of good quality.19 The International Continence Society and the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disorders recently published a best practice consensus document declaring laser and energy-based treatments in gynecology and urology to be largely experimental.20

Questions persist. Knowledge gaps exist, and recommendations related to subspecialty training—who should perform these procedures (gynecologists, plastic surgeons, urologists, dermatologists, family practitioners) and the level of training needed to safely perform them—are lacking. Patient selection and physician knowledge and experience related to female genital anatomy, female sexual function and dysfunction, multidisciplinary treatment options for various pelvic support problems and UI, as well as psychologic screening for body dysmorphic disorders, need to be considered in terms of treating both the functional and aesthetic aspects related to cosmetic and reconstructive gynecologic surgery.

Special considerations. The use of energy-based therapies in special populations, such as survivors of breast cancer or other gynecologic cancers, as well as women undergoing chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormonal manipulation (particularly with antiestrogenic SERMs and aromatase inhibitors) has not been adequately evaluated. A discussion of the risks, benefits, alternatives, and limited long-term outcome data for energy-based therapies in cancer survivors, as for all patients, must be included for adequate informed consent prior to undertaking these treatments.

Guidelines for appropriate tissue priming, laser settings, and concomitant energy-based technology with local hormone treatment (also known as laser-augmented drug delivery) need to be developed. Comparative long-term studies are needed to determine the safety and effectiveness of these technologies.

Caution advised. Given the lack of long-term safety and effectiveness data on energy-based therapies for the vague indications of vaginal laxity, and even for the well-defined conditions of stress UI and vulvovaginal atrophy, clinicians should exercise caution before promoting treatment, which can be expensive and is not without potential complications, such as vaginal pain, adhesive agglutination, and persistent dryness and dyspareunia.21

Fortunately, many randomized trials on various energy-based devices for gynecologic indications (GSM, stress UI, vaginal laxity, lichen sclerosus) are underway, and results from these studies will help inform future clinical practice and guideline development.

- Kaplan I, Goldman J, Ger R. The treatment of erosions of the uterine cervix by means of the CO2 laser. Obstet Gynecol. 1973;41:795-796.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy-based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:137-159.

- Gaspar A, Addamo G, Brandi H. Vaginal fractional CO2 laser: a minimally invasive option for vaginal rejuvenation. Am J Cosmetic Surg. 2011;28:156-162.

- Salvatore S, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Athanasiou S, et al. Histological study on the effects of microablative fractional CO2 laser on atrophic vaginal tissue: an ex vivo study. Menopause. 2015;22:845-849.

- Benedetto AV. What's new in cosmetic dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:117-128.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal rejuvenation or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21:1063-1068.

- Cruz VL, Steiner ML, Pompei LM, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial for evaluating the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol in the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018;25:21-28.

- Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Grigoradis T, et al. Microablative fractional CO2 laser for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause: up to 12-month results. Menopause. 2019;26:248-255.

- Gaspar A, Brandi H, Gomez V, et al. Efficacy of Erbium:YAG laser treatment compared to topical estriol treatment for symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:160-168.

- Gambacciani M, Levancini M, Russo E, et al. Long-term effects of vaginal erbium laser in the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric. 2018;21:148-152.

- Gambacciani M, Levancini M, Cervigni M. Vaginal erbium laser: the second-generation thermotherapy for the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric. 2015;18:757-763.

- Ogrinc UB, Sencar S, Lenasi H. Novel minimally invasive laser treatment of urinary incontinence in women. Lasers Surg Med. 2015;47:689-697.