User login

Survival similar with hearts donated after circulatory or brain death

in the first randomized trial comparing the two approaches.

“This randomized trial showing recipient survival with DCD to be similar to DBD should lead to DCD becoming the standard of care alongside DBD,” lead author Jacob Schroder, MD, surgical director, heart transplantation program, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“This should enable many more heart transplants to take place and for us to be able to cast the net further and wider for donors,” he said.

The trial was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Schroder estimated that only around one-fifth of the 120 U.S. heart transplant centers currently carry out DCD transplants, but he is hopeful that the publication of this study will encourage more transplant centers to do these DCD procedures.

“The problem is there are many low-volume heart transplant centers, which may not be keen to do DCD transplants as they are a bit more complicated and expensive than DBD heart transplants,” he said. “But we need to look at the big picture of how many lives can be saved by increasing the number of heart transplant procedures and the money saved by getting more patients off the waiting list.”

The authors explain that heart transplantation has traditionally been limited to the use of hearts obtained from donors after brain death, which allows in situ assessment of cardiac function and of the suitability for transplantation of the donor allograft before surgical procurement.

But because the need for heart transplants far exceeds the availability of suitable donors, the use of DCD hearts has been investigated and this approach is now being pursued in many countries. In the DCD approach, the heart will have stopped beating in the donor, and perfusion techniques are used to restart the organ.

There are two different approaches to restarting the heart in DCD. The first approach involves the heart being removed from the donor and reanimated, preserved, assessed, and transported with the use of a portable extracorporeal perfusion and preservation system (Organ Care System, TransMedics). The second involves restarting the heart in the donor’s body for evaluation before removal and transportation under the traditional cold storage method used for donations after brain death.

The current trial was designed to compare clinical outcomes in patients who had received a heart from a circulatory death donor using the portable extracorporeal perfusion method for DCD transplantation, with outcomes from the traditional method of heart transplantation using organs donated after brain death.

For the randomized, noninferiority trial, adult candidates for heart transplantation were assigned to receive a heart after the circulatory death of the donor or a heart from a donor after brain death if that heart was available first (circulatory-death group) or to receive only a heart that had been preserved with the use of traditional cold storage after the brain death of the donor (brain-death group).

The primary end point was the risk-adjusted survival at 6 months in the as-treated circulatory-death group, as compared with the brain-death group. The primary safety end point was serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

A total of 180 patients underwent transplantation, 90 of whom received a heart donated after circulatory death and 90 who received a heart donated after brain death. A total of 166 transplant recipients were included in the as-treated primary analysis (80 who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor and 86 who received a heart from a brain-death donor).

The risk-adjusted 6-month survival in the as-treated population was 94% among recipients of a heart from a circulatory-death donor, as compared with 90% among recipients of a heart from a brain-death donor (P < .001 for noninferiority).

There were no substantial between-group differences in the mean per-patient number of serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

Of 101 hearts from circulatory-death donors that were preserved with the use of the perfusion system, 90 were successfully transplanted according to the criteria for lactate trend and overall contractility of the donor heart, which resulted in overall utilization percentage of 89%.

More patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor had moderate or severe primary graft dysfunction (22%) than those who received a heart from a brain-death donor (10%). However, graft failure that resulted in retransplantation occurred in two (2.3%) patients who received a heart from a brain-death donor versus zero patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor.

The researchers note that the higher incidence of primary graft dysfunction in the circulatory-death group is expected, given the period of warm ischemia that occurs in this approach. But they point out that this did not affect patient or graft survival at 30 days or 1 year.

“Primary graft dysfunction is when the heart doesn’t fully work immediately after transplant and some mechanical support is needed,” Dr. Schroder commented to this news organization. “This occurred more often in the DCD group, but this mechanical support is only temporary, and generally only needed for a day or two.

“It looks like it might take the heart a little longer to start fully functioning after DCD, but our results show this doesn’t seem to affect recipient survival.”

He added: “We’ve started to become more comfortable with DCD. Sometimes it may take a little longer to get the heart working properly on its own, but the rate of mechanical support is now much lower than when we first started doing these procedures. And cardiac MRI on the recipient patients before discharge have shown that the DCD hearts are not more damaged than those from DBD donors.”

The authors also report that there were six donor hearts in the DCD group for which there were protocol deviations of functional warm ischemic time greater than 30 minutes or continuously rising lactate levels and these hearts did not show primary graft dysfunction.

On this observation, Dr. Schroder said: “I think we need to do more work on understanding the ischemic time limits. The current 30 minutes time limit was estimated in animal studies. We need to look more closely at data from actual DCD transplants. While 30 minutes may be too long for a heart from an older donor, the heart from a younger donor may be fine for a longer period of ischemic time as it will be healthier.”

“Exciting” results

In an editorial, Nancy K. Sweitzer, MD, PhD, vice chair of clinical research, department of medicine, and director of clinical research, division of cardiology, Washington University in St. Louis, describes the results of the current study as “exciting,” adding that, “They clearly show the feasibility and safety of transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors.”

However, Dr. Sweitzer points out that the sickest patients in the study – those who were United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) status 1 and 2 – were more likely to receive a DBD heart and the more stable patients (UNOS 3-6) were more likely to receive a DCD heart.

“This imbalance undoubtedly contributed to the success of the trial in meeting its noninferiority end point. Whether transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors is truly safe in our sickest patients with heart failure is not clear,” she says.

However, she concludes, “Although caution and continuous evaluation of data are warranted, the increased use of hearts from circulatory-death donors appears to be safe in the hands of experienced transplantation teams and will launch an exciting phase of learning and improvement.”

“A safely expanded pool of heart donors has the potential to increase fairness and equity in heart transplantation, allowing more persons with heart failure to have access to this lifesaving therapy,” she adds. “Organ donors and transplantation teams will save increasing numbers of lives with this most precious gift.”

The current study was supported by TransMedics. Dr. Schroder reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in the first randomized trial comparing the two approaches.

“This randomized trial showing recipient survival with DCD to be similar to DBD should lead to DCD becoming the standard of care alongside DBD,” lead author Jacob Schroder, MD, surgical director, heart transplantation program, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“This should enable many more heart transplants to take place and for us to be able to cast the net further and wider for donors,” he said.

The trial was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Schroder estimated that only around one-fifth of the 120 U.S. heart transplant centers currently carry out DCD transplants, but he is hopeful that the publication of this study will encourage more transplant centers to do these DCD procedures.

“The problem is there are many low-volume heart transplant centers, which may not be keen to do DCD transplants as they are a bit more complicated and expensive than DBD heart transplants,” he said. “But we need to look at the big picture of how many lives can be saved by increasing the number of heart transplant procedures and the money saved by getting more patients off the waiting list.”

The authors explain that heart transplantation has traditionally been limited to the use of hearts obtained from donors after brain death, which allows in situ assessment of cardiac function and of the suitability for transplantation of the donor allograft before surgical procurement.

But because the need for heart transplants far exceeds the availability of suitable donors, the use of DCD hearts has been investigated and this approach is now being pursued in many countries. In the DCD approach, the heart will have stopped beating in the donor, and perfusion techniques are used to restart the organ.

There are two different approaches to restarting the heart in DCD. The first approach involves the heart being removed from the donor and reanimated, preserved, assessed, and transported with the use of a portable extracorporeal perfusion and preservation system (Organ Care System, TransMedics). The second involves restarting the heart in the donor’s body for evaluation before removal and transportation under the traditional cold storage method used for donations after brain death.

The current trial was designed to compare clinical outcomes in patients who had received a heart from a circulatory death donor using the portable extracorporeal perfusion method for DCD transplantation, with outcomes from the traditional method of heart transplantation using organs donated after brain death.

For the randomized, noninferiority trial, adult candidates for heart transplantation were assigned to receive a heart after the circulatory death of the donor or a heart from a donor after brain death if that heart was available first (circulatory-death group) or to receive only a heart that had been preserved with the use of traditional cold storage after the brain death of the donor (brain-death group).

The primary end point was the risk-adjusted survival at 6 months in the as-treated circulatory-death group, as compared with the brain-death group. The primary safety end point was serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

A total of 180 patients underwent transplantation, 90 of whom received a heart donated after circulatory death and 90 who received a heart donated after brain death. A total of 166 transplant recipients were included in the as-treated primary analysis (80 who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor and 86 who received a heart from a brain-death donor).

The risk-adjusted 6-month survival in the as-treated population was 94% among recipients of a heart from a circulatory-death donor, as compared with 90% among recipients of a heart from a brain-death donor (P < .001 for noninferiority).

There were no substantial between-group differences in the mean per-patient number of serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

Of 101 hearts from circulatory-death donors that were preserved with the use of the perfusion system, 90 were successfully transplanted according to the criteria for lactate trend and overall contractility of the donor heart, which resulted in overall utilization percentage of 89%.

More patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor had moderate or severe primary graft dysfunction (22%) than those who received a heart from a brain-death donor (10%). However, graft failure that resulted in retransplantation occurred in two (2.3%) patients who received a heart from a brain-death donor versus zero patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor.

The researchers note that the higher incidence of primary graft dysfunction in the circulatory-death group is expected, given the period of warm ischemia that occurs in this approach. But they point out that this did not affect patient or graft survival at 30 days or 1 year.

“Primary graft dysfunction is when the heart doesn’t fully work immediately after transplant and some mechanical support is needed,” Dr. Schroder commented to this news organization. “This occurred more often in the DCD group, but this mechanical support is only temporary, and generally only needed for a day or two.

“It looks like it might take the heart a little longer to start fully functioning after DCD, but our results show this doesn’t seem to affect recipient survival.”

He added: “We’ve started to become more comfortable with DCD. Sometimes it may take a little longer to get the heart working properly on its own, but the rate of mechanical support is now much lower than when we first started doing these procedures. And cardiac MRI on the recipient patients before discharge have shown that the DCD hearts are not more damaged than those from DBD donors.”

The authors also report that there were six donor hearts in the DCD group for which there were protocol deviations of functional warm ischemic time greater than 30 minutes or continuously rising lactate levels and these hearts did not show primary graft dysfunction.

On this observation, Dr. Schroder said: “I think we need to do more work on understanding the ischemic time limits. The current 30 minutes time limit was estimated in animal studies. We need to look more closely at data from actual DCD transplants. While 30 minutes may be too long for a heart from an older donor, the heart from a younger donor may be fine for a longer period of ischemic time as it will be healthier.”

“Exciting” results

In an editorial, Nancy K. Sweitzer, MD, PhD, vice chair of clinical research, department of medicine, and director of clinical research, division of cardiology, Washington University in St. Louis, describes the results of the current study as “exciting,” adding that, “They clearly show the feasibility and safety of transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors.”

However, Dr. Sweitzer points out that the sickest patients in the study – those who were United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) status 1 and 2 – were more likely to receive a DBD heart and the more stable patients (UNOS 3-6) were more likely to receive a DCD heart.

“This imbalance undoubtedly contributed to the success of the trial in meeting its noninferiority end point. Whether transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors is truly safe in our sickest patients with heart failure is not clear,” she says.

However, she concludes, “Although caution and continuous evaluation of data are warranted, the increased use of hearts from circulatory-death donors appears to be safe in the hands of experienced transplantation teams and will launch an exciting phase of learning and improvement.”

“A safely expanded pool of heart donors has the potential to increase fairness and equity in heart transplantation, allowing more persons with heart failure to have access to this lifesaving therapy,” she adds. “Organ donors and transplantation teams will save increasing numbers of lives with this most precious gift.”

The current study was supported by TransMedics. Dr. Schroder reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in the first randomized trial comparing the two approaches.

“This randomized trial showing recipient survival with DCD to be similar to DBD should lead to DCD becoming the standard of care alongside DBD,” lead author Jacob Schroder, MD, surgical director, heart transplantation program, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., said in an interview.

“This should enable many more heart transplants to take place and for us to be able to cast the net further and wider for donors,” he said.

The trial was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Schroder estimated that only around one-fifth of the 120 U.S. heart transplant centers currently carry out DCD transplants, but he is hopeful that the publication of this study will encourage more transplant centers to do these DCD procedures.

“The problem is there are many low-volume heart transplant centers, which may not be keen to do DCD transplants as they are a bit more complicated and expensive than DBD heart transplants,” he said. “But we need to look at the big picture of how many lives can be saved by increasing the number of heart transplant procedures and the money saved by getting more patients off the waiting list.”

The authors explain that heart transplantation has traditionally been limited to the use of hearts obtained from donors after brain death, which allows in situ assessment of cardiac function and of the suitability for transplantation of the donor allograft before surgical procurement.

But because the need for heart transplants far exceeds the availability of suitable donors, the use of DCD hearts has been investigated and this approach is now being pursued in many countries. In the DCD approach, the heart will have stopped beating in the donor, and perfusion techniques are used to restart the organ.

There are two different approaches to restarting the heart in DCD. The first approach involves the heart being removed from the donor and reanimated, preserved, assessed, and transported with the use of a portable extracorporeal perfusion and preservation system (Organ Care System, TransMedics). The second involves restarting the heart in the donor’s body for evaluation before removal and transportation under the traditional cold storage method used for donations after brain death.

The current trial was designed to compare clinical outcomes in patients who had received a heart from a circulatory death donor using the portable extracorporeal perfusion method for DCD transplantation, with outcomes from the traditional method of heart transplantation using organs donated after brain death.

For the randomized, noninferiority trial, adult candidates for heart transplantation were assigned to receive a heart after the circulatory death of the donor or a heart from a donor after brain death if that heart was available first (circulatory-death group) or to receive only a heart that had been preserved with the use of traditional cold storage after the brain death of the donor (brain-death group).

The primary end point was the risk-adjusted survival at 6 months in the as-treated circulatory-death group, as compared with the brain-death group. The primary safety end point was serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

A total of 180 patients underwent transplantation, 90 of whom received a heart donated after circulatory death and 90 who received a heart donated after brain death. A total of 166 transplant recipients were included in the as-treated primary analysis (80 who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor and 86 who received a heart from a brain-death donor).

The risk-adjusted 6-month survival in the as-treated population was 94% among recipients of a heart from a circulatory-death donor, as compared with 90% among recipients of a heart from a brain-death donor (P < .001 for noninferiority).

There were no substantial between-group differences in the mean per-patient number of serious adverse events associated with the heart graft at 30 days after transplantation.

Of 101 hearts from circulatory-death donors that were preserved with the use of the perfusion system, 90 were successfully transplanted according to the criteria for lactate trend and overall contractility of the donor heart, which resulted in overall utilization percentage of 89%.

More patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor had moderate or severe primary graft dysfunction (22%) than those who received a heart from a brain-death donor (10%). However, graft failure that resulted in retransplantation occurred in two (2.3%) patients who received a heart from a brain-death donor versus zero patients who received a heart from a circulatory-death donor.

The researchers note that the higher incidence of primary graft dysfunction in the circulatory-death group is expected, given the period of warm ischemia that occurs in this approach. But they point out that this did not affect patient or graft survival at 30 days or 1 year.

“Primary graft dysfunction is when the heart doesn’t fully work immediately after transplant and some mechanical support is needed,” Dr. Schroder commented to this news organization. “This occurred more often in the DCD group, but this mechanical support is only temporary, and generally only needed for a day or two.

“It looks like it might take the heart a little longer to start fully functioning after DCD, but our results show this doesn’t seem to affect recipient survival.”

He added: “We’ve started to become more comfortable with DCD. Sometimes it may take a little longer to get the heart working properly on its own, but the rate of mechanical support is now much lower than when we first started doing these procedures. And cardiac MRI on the recipient patients before discharge have shown that the DCD hearts are not more damaged than those from DBD donors.”

The authors also report that there were six donor hearts in the DCD group for which there were protocol deviations of functional warm ischemic time greater than 30 minutes or continuously rising lactate levels and these hearts did not show primary graft dysfunction.

On this observation, Dr. Schroder said: “I think we need to do more work on understanding the ischemic time limits. The current 30 minutes time limit was estimated in animal studies. We need to look more closely at data from actual DCD transplants. While 30 minutes may be too long for a heart from an older donor, the heart from a younger donor may be fine for a longer period of ischemic time as it will be healthier.”

“Exciting” results

In an editorial, Nancy K. Sweitzer, MD, PhD, vice chair of clinical research, department of medicine, and director of clinical research, division of cardiology, Washington University in St. Louis, describes the results of the current study as “exciting,” adding that, “They clearly show the feasibility and safety of transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors.”

However, Dr. Sweitzer points out that the sickest patients in the study – those who were United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) status 1 and 2 – were more likely to receive a DBD heart and the more stable patients (UNOS 3-6) were more likely to receive a DCD heart.

“This imbalance undoubtedly contributed to the success of the trial in meeting its noninferiority end point. Whether transplantation of hearts from circulatory-death donors is truly safe in our sickest patients with heart failure is not clear,” she says.

However, she concludes, “Although caution and continuous evaluation of data are warranted, the increased use of hearts from circulatory-death donors appears to be safe in the hands of experienced transplantation teams and will launch an exciting phase of learning and improvement.”

“A safely expanded pool of heart donors has the potential to increase fairness and equity in heart transplantation, allowing more persons with heart failure to have access to this lifesaving therapy,” she adds. “Organ donors and transplantation teams will save increasing numbers of lives with this most precious gift.”

The current study was supported by TransMedics. Dr. Schroder reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Transplant centers often skip the top spot on the kidney waitlist

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

The idea of rationing medical care is anathema to most doctors. Sure, we acknowledge that the realities of health care costs and insurance companies might limit our options, but there is always a sense that when something is truly, truly needed, we can get it done.

Except in one very particular situation, a situation where rationing of care is the norm. That situation? Organ transplantation.

There is no way around this: More patients need organ transplants than there are organs available to transplant. It is cold, hard arithmetic. No amount of negotiating with an insurance company or engaging in prior authorization can change that.

As a kidney doctor, this issue is close to my heart. There are around 100,000 people on the kidney transplant waiting list in the U.S., with 3,000 new patients being added per month. There are only 25,000 kidney transplants per year. And each year, around 5,000 people die while waiting for a transplant.

A world of scarcity, like the world of kidney transplant, is ripe for bias at best and abuse at worst. It is in part for that reason that the Kidney Allocation System exists. It answers the cold, hard arithmetic of transplant scarcity with the cold, hard arithmetic of a computer algorithm, ranking individuals on the waitlist on a variety of factors to ensure that those who will benefit most from a transplant get it first.

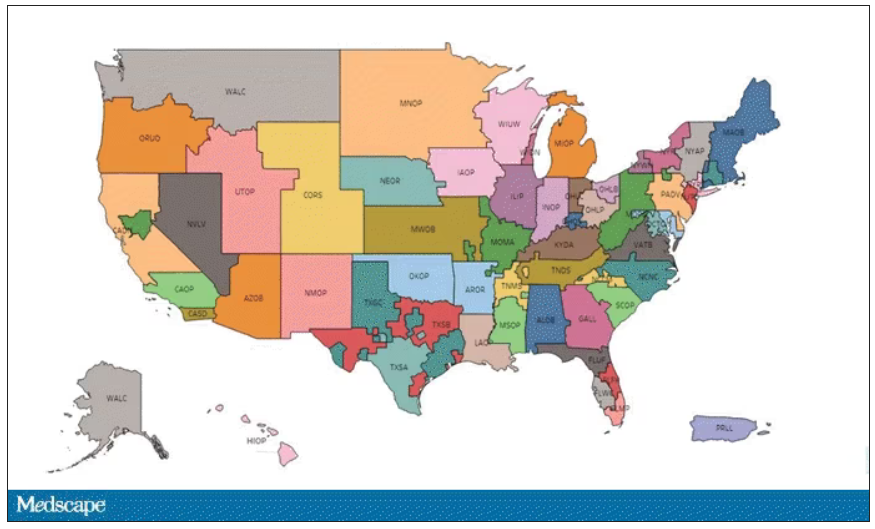

This area is a bit complex but I’ll try to break it down into what you need to know. There are 56 organ procurement organizations (OPOs) in the United States. These are nonprofits with the responsibility to recover organs from deceased donors in their area.

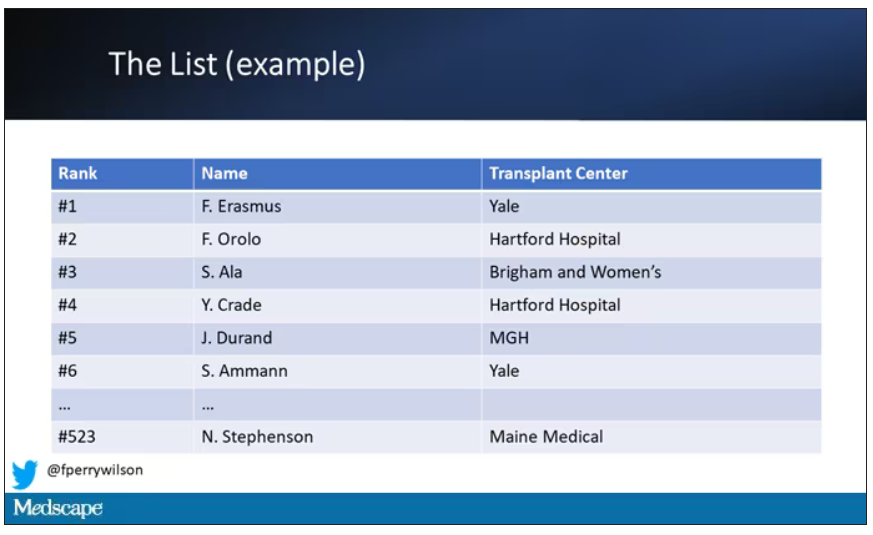

Each of those OPOs maintains a ranked list of those waiting for a kidney transplant. Depending on the OPO, the list may range from a couple hundred people to a couple thousand, but one thing is the same, no matter what: If you are at the top of the list, you should be the next to get a transplant.

Most OPOs have multiple transplant centers in them, and each center is going to prioritize its own patients. If a Yale patient is No. 1 on the list and a kidney offer comes in, it would be a good idea for us to accept, because if we reject the offer, the organ may go to a competing center whose patients is ranked No. 2.

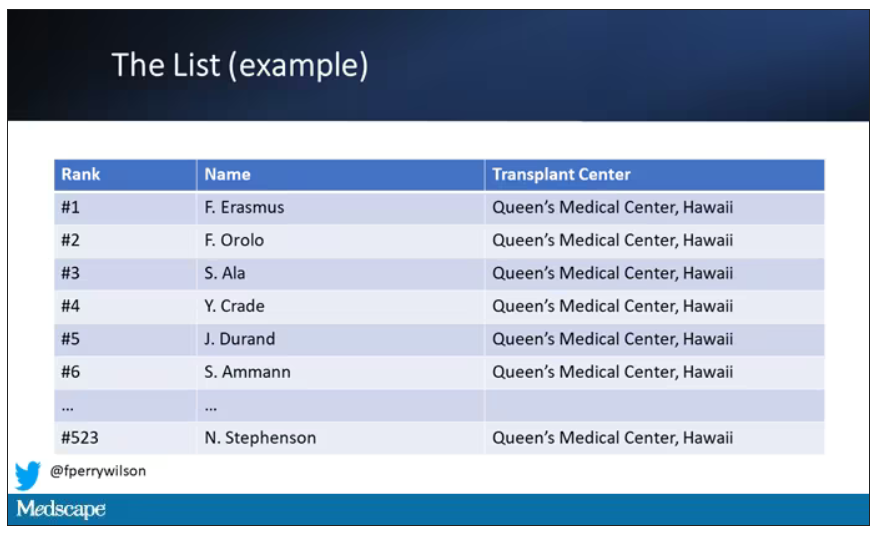

But 11 OPOs around the country are served by only one center. This gives that center huge flexibility to determine who gets what kidney, because if they refuse an offer for whoever is at the top of their list, they can still give the kidney to the second person on their list, or third, or 30th, theoretically.

But in practice, does this phenomenon, known colloquially as “list diving,” actually happen? This manuscript from Sumit Mohan and colleagues suggests that it does, and at rates that are, frankly, eye-popping.

The Columbia team used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to conduct the analysis. The database tracks all aspects of the transplant process, from listing to ranking to, eventually, the transplant itself. With that data, they could determine how often, across these 11 OPOs, the No. 1 person on the list did not get the available kidney.

The answer? Out of 4,668 transplants conducted from 2015 to 2019, the transplant centers skipped their highest-ranked person 3,169 times – 68% of the time.

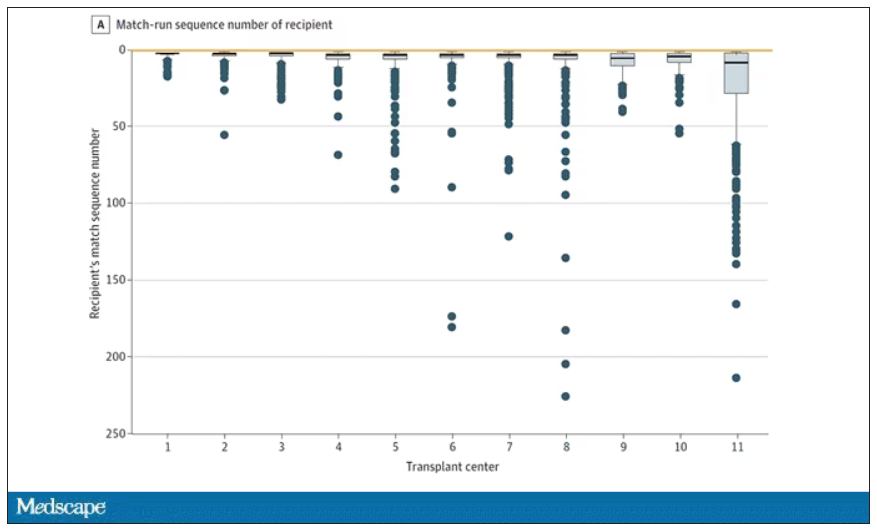

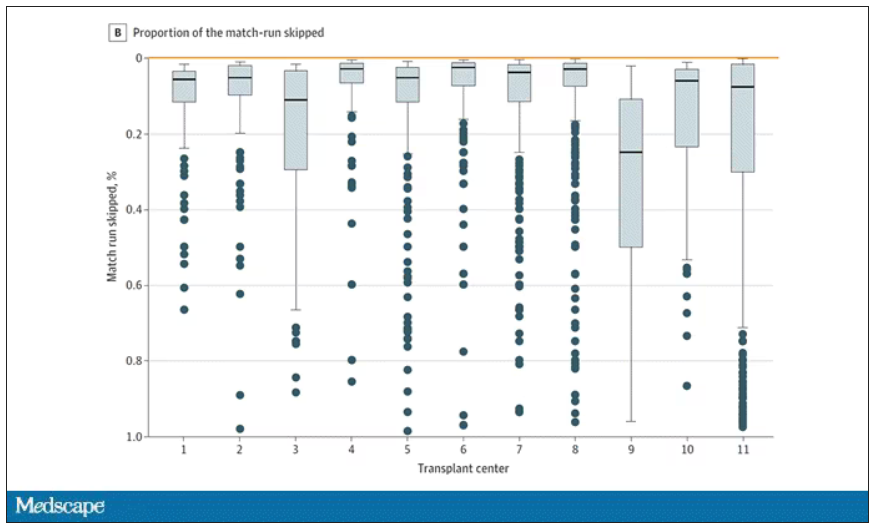

This graph shows the distribution of where on the list these kidneys went. You can see some centers diving down 100 or 200 places.

Transplant centers have lists of different lengths, so this graph shows you how far down on the percentage scale the centers dived. You can see centers skipping right to the bottom of their list in some cases.

Now, I should make it clear that transplant centers do have legitimate discretion here. Transplant centers may pass up a less-than-perfect kidney for their No. 1 spot, knowing that that individual will get more offers soon, in favor of someone further down the list who will not see an offer for a while. It’s gaming the system a bit, but not, you know, for evil. And the data support this. Top-ranked people who got skipped had received a lower-quality kidney offer than those who did not get skipped. But I will also note that those who were skipped were less likely to be White, less likely to be Hispanic, and more likely to be male. That should raise your eyebrows.

Interestingly, this practice may not be limited to those cases where the OPO has only one transplant center. Conducting the same analysis across all 231 kidney transplant centers in the U.S., the authors found that the top candidate was skipped 76% of the time.

So, what’s going on here? I’m sure that some of this list-skipping is for legitimate medical reasons. And it should be pointed out that recipients have a right to refuse an offer as well – and might be more picky if they know they are at the top of the list. But patient preference was listed as the reason for list diving in only about 14% of cases. The vast majority (65%) of reasons given were based on donor quality. The problem is that donor quality can be quite subjective. And remember, these organs were transplanted eventually so they couldn’t have been that bad.

Putting the data together, though, I can’t shake the sense that centers are using the list more for guidance than as a real mechanism to ensure an equitable allocation system. With all the flexibility that centers have to bypass individuals on the list, the list loses its meaning and its power.

I spoke to one transplant nephrologist who suggested that these data should prompt an investigation by the United Network for Organ Sharing, the body that governs all these OPOs. That may be a necessary step.

I hope there comes a day when this issue is moot, when growing kidneys in the lab – or regenerating one’s own kidneys – is a possibility. But that day is not yet here and we must deal with the scarcity we have. In this world, we need the list to prevent abuse. But the list only works if the list is followed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He reported having no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

The idea of rationing medical care is anathema to most doctors. Sure, we acknowledge that the realities of health care costs and insurance companies might limit our options, but there is always a sense that when something is truly, truly needed, we can get it done.

Except in one very particular situation, a situation where rationing of care is the norm. That situation? Organ transplantation.

There is no way around this: More patients need organ transplants than there are organs available to transplant. It is cold, hard arithmetic. No amount of negotiating with an insurance company or engaging in prior authorization can change that.

As a kidney doctor, this issue is close to my heart. There are around 100,000 people on the kidney transplant waiting list in the U.S., with 3,000 new patients being added per month. There are only 25,000 kidney transplants per year. And each year, around 5,000 people die while waiting for a transplant.

A world of scarcity, like the world of kidney transplant, is ripe for bias at best and abuse at worst. It is in part for that reason that the Kidney Allocation System exists. It answers the cold, hard arithmetic of transplant scarcity with the cold, hard arithmetic of a computer algorithm, ranking individuals on the waitlist on a variety of factors to ensure that those who will benefit most from a transplant get it first.

This area is a bit complex but I’ll try to break it down into what you need to know. There are 56 organ procurement organizations (OPOs) in the United States. These are nonprofits with the responsibility to recover organs from deceased donors in their area.

Each of those OPOs maintains a ranked list of those waiting for a kidney transplant. Depending on the OPO, the list may range from a couple hundred people to a couple thousand, but one thing is the same, no matter what: If you are at the top of the list, you should be the next to get a transplant.

Most OPOs have multiple transplant centers in them, and each center is going to prioritize its own patients. If a Yale patient is No. 1 on the list and a kidney offer comes in, it would be a good idea for us to accept, because if we reject the offer, the organ may go to a competing center whose patients is ranked No. 2.

But 11 OPOs around the country are served by only one center. This gives that center huge flexibility to determine who gets what kidney, because if they refuse an offer for whoever is at the top of their list, they can still give the kidney to the second person on their list, or third, or 30th, theoretically.

But in practice, does this phenomenon, known colloquially as “list diving,” actually happen? This manuscript from Sumit Mohan and colleagues suggests that it does, and at rates that are, frankly, eye-popping.

The Columbia team used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to conduct the analysis. The database tracks all aspects of the transplant process, from listing to ranking to, eventually, the transplant itself. With that data, they could determine how often, across these 11 OPOs, the No. 1 person on the list did not get the available kidney.

The answer? Out of 4,668 transplants conducted from 2015 to 2019, the transplant centers skipped their highest-ranked person 3,169 times – 68% of the time.

This graph shows the distribution of where on the list these kidneys went. You can see some centers diving down 100 or 200 places.

Transplant centers have lists of different lengths, so this graph shows you how far down on the percentage scale the centers dived. You can see centers skipping right to the bottom of their list in some cases.

Now, I should make it clear that transplant centers do have legitimate discretion here. Transplant centers may pass up a less-than-perfect kidney for their No. 1 spot, knowing that that individual will get more offers soon, in favor of someone further down the list who will not see an offer for a while. It’s gaming the system a bit, but not, you know, for evil. And the data support this. Top-ranked people who got skipped had received a lower-quality kidney offer than those who did not get skipped. But I will also note that those who were skipped were less likely to be White, less likely to be Hispanic, and more likely to be male. That should raise your eyebrows.

Interestingly, this practice may not be limited to those cases where the OPO has only one transplant center. Conducting the same analysis across all 231 kidney transplant centers in the U.S., the authors found that the top candidate was skipped 76% of the time.

So, what’s going on here? I’m sure that some of this list-skipping is for legitimate medical reasons. And it should be pointed out that recipients have a right to refuse an offer as well – and might be more picky if they know they are at the top of the list. But patient preference was listed as the reason for list diving in only about 14% of cases. The vast majority (65%) of reasons given were based on donor quality. The problem is that donor quality can be quite subjective. And remember, these organs were transplanted eventually so they couldn’t have been that bad.

Putting the data together, though, I can’t shake the sense that centers are using the list more for guidance than as a real mechanism to ensure an equitable allocation system. With all the flexibility that centers have to bypass individuals on the list, the list loses its meaning and its power.

I spoke to one transplant nephrologist who suggested that these data should prompt an investigation by the United Network for Organ Sharing, the body that governs all these OPOs. That may be a necessary step.

I hope there comes a day when this issue is moot, when growing kidneys in the lab – or regenerating one’s own kidneys – is a possibility. But that day is not yet here and we must deal with the scarcity we have. In this world, we need the list to prevent abuse. But the list only works if the list is followed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He reported having no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

The idea of rationing medical care is anathema to most doctors. Sure, we acknowledge that the realities of health care costs and insurance companies might limit our options, but there is always a sense that when something is truly, truly needed, we can get it done.

Except in one very particular situation, a situation where rationing of care is the norm. That situation? Organ transplantation.

There is no way around this: More patients need organ transplants than there are organs available to transplant. It is cold, hard arithmetic. No amount of negotiating with an insurance company or engaging in prior authorization can change that.

As a kidney doctor, this issue is close to my heart. There are around 100,000 people on the kidney transplant waiting list in the U.S., with 3,000 new patients being added per month. There are only 25,000 kidney transplants per year. And each year, around 5,000 people die while waiting for a transplant.

A world of scarcity, like the world of kidney transplant, is ripe for bias at best and abuse at worst. It is in part for that reason that the Kidney Allocation System exists. It answers the cold, hard arithmetic of transplant scarcity with the cold, hard arithmetic of a computer algorithm, ranking individuals on the waitlist on a variety of factors to ensure that those who will benefit most from a transplant get it first.

This area is a bit complex but I’ll try to break it down into what you need to know. There are 56 organ procurement organizations (OPOs) in the United States. These are nonprofits with the responsibility to recover organs from deceased donors in their area.

Each of those OPOs maintains a ranked list of those waiting for a kidney transplant. Depending on the OPO, the list may range from a couple hundred people to a couple thousand, but one thing is the same, no matter what: If you are at the top of the list, you should be the next to get a transplant.

Most OPOs have multiple transplant centers in them, and each center is going to prioritize its own patients. If a Yale patient is No. 1 on the list and a kidney offer comes in, it would be a good idea for us to accept, because if we reject the offer, the organ may go to a competing center whose patients is ranked No. 2.

But 11 OPOs around the country are served by only one center. This gives that center huge flexibility to determine who gets what kidney, because if they refuse an offer for whoever is at the top of their list, they can still give the kidney to the second person on their list, or third, or 30th, theoretically.

But in practice, does this phenomenon, known colloquially as “list diving,” actually happen? This manuscript from Sumit Mohan and colleagues suggests that it does, and at rates that are, frankly, eye-popping.

The Columbia team used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to conduct the analysis. The database tracks all aspects of the transplant process, from listing to ranking to, eventually, the transplant itself. With that data, they could determine how often, across these 11 OPOs, the No. 1 person on the list did not get the available kidney.

The answer? Out of 4,668 transplants conducted from 2015 to 2019, the transplant centers skipped their highest-ranked person 3,169 times – 68% of the time.

This graph shows the distribution of where on the list these kidneys went. You can see some centers diving down 100 or 200 places.

Transplant centers have lists of different lengths, so this graph shows you how far down on the percentage scale the centers dived. You can see centers skipping right to the bottom of their list in some cases.

Now, I should make it clear that transplant centers do have legitimate discretion here. Transplant centers may pass up a less-than-perfect kidney for their No. 1 spot, knowing that that individual will get more offers soon, in favor of someone further down the list who will not see an offer for a while. It’s gaming the system a bit, but not, you know, for evil. And the data support this. Top-ranked people who got skipped had received a lower-quality kidney offer than those who did not get skipped. But I will also note that those who were skipped were less likely to be White, less likely to be Hispanic, and more likely to be male. That should raise your eyebrows.

Interestingly, this practice may not be limited to those cases where the OPO has only one transplant center. Conducting the same analysis across all 231 kidney transplant centers in the U.S., the authors found that the top candidate was skipped 76% of the time.

So, what’s going on here? I’m sure that some of this list-skipping is for legitimate medical reasons. And it should be pointed out that recipients have a right to refuse an offer as well – and might be more picky if they know they are at the top of the list. But patient preference was listed as the reason for list diving in only about 14% of cases. The vast majority (65%) of reasons given were based on donor quality. The problem is that donor quality can be quite subjective. And remember, these organs were transplanted eventually so they couldn’t have been that bad.

Putting the data together, though, I can’t shake the sense that centers are using the list more for guidance than as a real mechanism to ensure an equitable allocation system. With all the flexibility that centers have to bypass individuals on the list, the list loses its meaning and its power.

I spoke to one transplant nephrologist who suggested that these data should prompt an investigation by the United Network for Organ Sharing, the body that governs all these OPOs. That may be a necessary step.

I hope there comes a day when this issue is moot, when growing kidneys in the lab – or regenerating one’s own kidneys – is a possibility. But that day is not yet here and we must deal with the scarcity we have. In this world, we need the list to prevent abuse. But the list only works if the list is followed.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He reported having no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Phase 3 trial: Maribavir yields post-transplant benefits

Overall mortality in the 109 patients from these subcohorts from SOLSTICE was lower, compared with mortality reported for similar populations treated with conventional therapies used to treat relapsed or refractory (R/R) CMV, according to findings presented in April at the annual meeting of the European Society for Bone and Marrow Transplantation.

“These results, in addition to the superior efficacy in CMV clearance observed for maribavir in SOLSTICE provide supportive evidence of the potential for the long-term benefit of maribavir treatment for post-transplant CMV infection,” Ishan Hirji, of Takeda Development Center Americas, and colleagues reported during a poster session at the meeting.

A retrospective chart review of the 41 hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients and 68 solid organ transplant (SOT) patients randomized to receive maribavir showed an overall mortality rate of 15.6% at 52 weeks after initiation of treatment with the antiviral agent. Among the HSCT patients, 14 deaths occurred (34.1%), with 8 occurring during the study periods and 6 occurring during follow-up. Among the SOT patients, three deaths occurred (4.4%), all during follow-up chart review.

Causes of death included underlying disease relapse in four patients, infection other than CMV in six patients, and one case each of CMV-related factors, transplant-related factors, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and septic shock. Causes of death in the SOT patients included one case each of CMV-related factors, anemia, and renal failure.

“No patients had new graft loss or retransplantation during the chart review period,” the investigators noted.

The findings are notable as CMV infection occurs in 30%-70% of HSCT recipients and 16%-56% of SOT recipients and can lead to complications, including transplant failure and death. Reported 1-year mortality rates following standard therapies for CMV range from 31% to 50%, they explained.

Patients in the SOLSTICE trial received 8 weeks of treatment and were followed for 12 additional weeks. CMV clearance at the end of treatment was 55.7% in the maribavir treatment arm versus 23.9% in a control group of patients treated with investigator choice of therapy. As reported by this news organization, the findings formed the basis for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of maribavir in November 2021.

The current analysis included a chart review period that started 1 day after the SOLSTICE trial period and continued for 32 additional weeks.

These long-term follow-up data confirm the benefits of maribavir for the treatment of post-transplant CMV, according to the investigators, and findings from a separate study reported at the ESBMT meeting underscore the importance of the durable benefits observed with maribavir treatment.

For that retrospective study, Maria Laura Fox, of Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, and colleagues pooled de-identified data from 250 adult HSCT recipients with R/R CMV who were treated with agents other than maribavir at transplant centers in the United States or Europe. They aimed to “generate real-world evidence on the burden of CMV infection/disease in HSCT recipients who had refractory/resistant CMV or were intolerant to current treatments.”

Nearly 92% of patients received two or more therapies to treat CMV, and 92.2% discontinued treatment or had one or more therapy dose changes or discontinuation, and 42 patients failed to achieve clearance of the CMV index episode.

CMV recurred in 35.2% of patients, and graft failure occurred in 4% of patients, the investigators reported.

All-cause mortality was 56.0%, and mortality at 1 year after identification of R/R disease or treatment intolerance was 45.2%, they noted, adding that the study results “highlight the real-world complexities and high burden of CMV infection for HSCT recipients.”

“With available anti-CMV agents [excluding maribavir], a notable proportion of patients failed to achieve viremia clearance once developing RRI [resistant, refractory, or intolerant] CMV and/or experienced recurrence, and were at risk of adverse outcomes, including myelosuppression and mortality. There is a need for therapies that achieve and maintain CMV clearance with improved safety profiles,” they concluded.

Both studies were funded by Takeda Development Center Americas, the maker of Levtencity. Ms. Hirji is an employee of Takeda and reported stock ownership. Ms. Fox reported relationships with Sierra Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, and AbbVie.

Overall mortality in the 109 patients from these subcohorts from SOLSTICE was lower, compared with mortality reported for similar populations treated with conventional therapies used to treat relapsed or refractory (R/R) CMV, according to findings presented in April at the annual meeting of the European Society for Bone and Marrow Transplantation.

“These results, in addition to the superior efficacy in CMV clearance observed for maribavir in SOLSTICE provide supportive evidence of the potential for the long-term benefit of maribavir treatment for post-transplant CMV infection,” Ishan Hirji, of Takeda Development Center Americas, and colleagues reported during a poster session at the meeting.

A retrospective chart review of the 41 hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients and 68 solid organ transplant (SOT) patients randomized to receive maribavir showed an overall mortality rate of 15.6% at 52 weeks after initiation of treatment with the antiviral agent. Among the HSCT patients, 14 deaths occurred (34.1%), with 8 occurring during the study periods and 6 occurring during follow-up. Among the SOT patients, three deaths occurred (4.4%), all during follow-up chart review.

Causes of death included underlying disease relapse in four patients, infection other than CMV in six patients, and one case each of CMV-related factors, transplant-related factors, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and septic shock. Causes of death in the SOT patients included one case each of CMV-related factors, anemia, and renal failure.

“No patients had new graft loss or retransplantation during the chart review period,” the investigators noted.

The findings are notable as CMV infection occurs in 30%-70% of HSCT recipients and 16%-56% of SOT recipients and can lead to complications, including transplant failure and death. Reported 1-year mortality rates following standard therapies for CMV range from 31% to 50%, they explained.

Patients in the SOLSTICE trial received 8 weeks of treatment and were followed for 12 additional weeks. CMV clearance at the end of treatment was 55.7% in the maribavir treatment arm versus 23.9% in a control group of patients treated with investigator choice of therapy. As reported by this news organization, the findings formed the basis for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of maribavir in November 2021.

The current analysis included a chart review period that started 1 day after the SOLSTICE trial period and continued for 32 additional weeks.

These long-term follow-up data confirm the benefits of maribavir for the treatment of post-transplant CMV, according to the investigators, and findings from a separate study reported at the ESBMT meeting underscore the importance of the durable benefits observed with maribavir treatment.

For that retrospective study, Maria Laura Fox, of Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, and colleagues pooled de-identified data from 250 adult HSCT recipients with R/R CMV who were treated with agents other than maribavir at transplant centers in the United States or Europe. They aimed to “generate real-world evidence on the burden of CMV infection/disease in HSCT recipients who had refractory/resistant CMV or were intolerant to current treatments.”

Nearly 92% of patients received two or more therapies to treat CMV, and 92.2% discontinued treatment or had one or more therapy dose changes or discontinuation, and 42 patients failed to achieve clearance of the CMV index episode.

CMV recurred in 35.2% of patients, and graft failure occurred in 4% of patients, the investigators reported.

All-cause mortality was 56.0%, and mortality at 1 year after identification of R/R disease or treatment intolerance was 45.2%, they noted, adding that the study results “highlight the real-world complexities and high burden of CMV infection for HSCT recipients.”

“With available anti-CMV agents [excluding maribavir], a notable proportion of patients failed to achieve viremia clearance once developing RRI [resistant, refractory, or intolerant] CMV and/or experienced recurrence, and were at risk of adverse outcomes, including myelosuppression and mortality. There is a need for therapies that achieve and maintain CMV clearance with improved safety profiles,” they concluded.

Both studies were funded by Takeda Development Center Americas, the maker of Levtencity. Ms. Hirji is an employee of Takeda and reported stock ownership. Ms. Fox reported relationships with Sierra Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, and AbbVie.

Overall mortality in the 109 patients from these subcohorts from SOLSTICE was lower, compared with mortality reported for similar populations treated with conventional therapies used to treat relapsed or refractory (R/R) CMV, according to findings presented in April at the annual meeting of the European Society for Bone and Marrow Transplantation.

“These results, in addition to the superior efficacy in CMV clearance observed for maribavir in SOLSTICE provide supportive evidence of the potential for the long-term benefit of maribavir treatment for post-transplant CMV infection,” Ishan Hirji, of Takeda Development Center Americas, and colleagues reported during a poster session at the meeting.

A retrospective chart review of the 41 hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients and 68 solid organ transplant (SOT) patients randomized to receive maribavir showed an overall mortality rate of 15.6% at 52 weeks after initiation of treatment with the antiviral agent. Among the HSCT patients, 14 deaths occurred (34.1%), with 8 occurring during the study periods and 6 occurring during follow-up. Among the SOT patients, three deaths occurred (4.4%), all during follow-up chart review.

Causes of death included underlying disease relapse in four patients, infection other than CMV in six patients, and one case each of CMV-related factors, transplant-related factors, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and septic shock. Causes of death in the SOT patients included one case each of CMV-related factors, anemia, and renal failure.

“No patients had new graft loss or retransplantation during the chart review period,” the investigators noted.

The findings are notable as CMV infection occurs in 30%-70% of HSCT recipients and 16%-56% of SOT recipients and can lead to complications, including transplant failure and death. Reported 1-year mortality rates following standard therapies for CMV range from 31% to 50%, they explained.

Patients in the SOLSTICE trial received 8 weeks of treatment and were followed for 12 additional weeks. CMV clearance at the end of treatment was 55.7% in the maribavir treatment arm versus 23.9% in a control group of patients treated with investigator choice of therapy. As reported by this news organization, the findings formed the basis for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of maribavir in November 2021.

The current analysis included a chart review period that started 1 day after the SOLSTICE trial period and continued for 32 additional weeks.

These long-term follow-up data confirm the benefits of maribavir for the treatment of post-transplant CMV, according to the investigators, and findings from a separate study reported at the ESBMT meeting underscore the importance of the durable benefits observed with maribavir treatment.

For that retrospective study, Maria Laura Fox, of Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, and colleagues pooled de-identified data from 250 adult HSCT recipients with R/R CMV who were treated with agents other than maribavir at transplant centers in the United States or Europe. They aimed to “generate real-world evidence on the burden of CMV infection/disease in HSCT recipients who had refractory/resistant CMV or were intolerant to current treatments.”

Nearly 92% of patients received two or more therapies to treat CMV, and 92.2% discontinued treatment or had one or more therapy dose changes or discontinuation, and 42 patients failed to achieve clearance of the CMV index episode.

CMV recurred in 35.2% of patients, and graft failure occurred in 4% of patients, the investigators reported.

All-cause mortality was 56.0%, and mortality at 1 year after identification of R/R disease or treatment intolerance was 45.2%, they noted, adding that the study results “highlight the real-world complexities and high burden of CMV infection for HSCT recipients.”

“With available anti-CMV agents [excluding maribavir], a notable proportion of patients failed to achieve viremia clearance once developing RRI [resistant, refractory, or intolerant] CMV and/or experienced recurrence, and were at risk of adverse outcomes, including myelosuppression and mortality. There is a need for therapies that achieve and maintain CMV clearance with improved safety profiles,” they concluded.

Both studies were funded by Takeda Development Center Americas, the maker of Levtencity. Ms. Hirji is an employee of Takeda and reported stock ownership. Ms. Fox reported relationships with Sierra Oncology, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, and AbbVie.

FROM ESBMT 2023

Experts debate reducing ASCT for multiple myeloma

NEW YORK –

Hematologist-oncologists whose top priority is ensuring that patients have the best chance of progression-free survival (PFS) will continue to choose ASCT as a best practice, argued Amrita Krishnan, MD, hematologist at the Judy and Bernard Briskin Center for Multiple Myeloma Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, Calif.

A differing perspective was presented by C. Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, hematologist at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami. Dr. Landgren cited evidence that, for newly diagnosed MM patients treated successfully with modern combination therapies, ASCT is not a mandatory treatment step before starting maintenance therapy.

Making a case for ASCT as the SoC, Dr. Krishnan noted, “based on the DETERMINATION trial [DT], there is far superior rate of PFS with patients who get ASCT up front, compared patients who got only conventional chemotherapy with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone [RVd]. PFS is the endpoint we look for in our treatment regimens.

“If you don’t use ASCT up front, you may lose the opportunity at later relapse. This is not to say that transplant is the only tool at our disposal. It is just an indispensable one. The GRIFFIN trial [GT] has shown us that robust combinations of drugs [both RVd and dexamethasone +RVd] can improve patient outcomes both before and after ASCT,” Dr. Krishnan concluded.

In his presentation, Dr. Landgren stated that, in the DT, while PFS is prolonged by the addition of ASCT to RVd, adding ASCT did not significantly increase overall survival (OS) rates. He added that treatment-related AEs of grade 3+ occurred in only 78.2% of patients on RVd versus 94.2% of RVd + ASCT patients.

“ASCT should not be the SoC frontline treatment in MM because it does not prolong OS. The IFM trial and the DT both show that there is no difference in OS between drug combination therapy followed by transplant and maintenance versus combination therapy alone, followed by transplant and maintenance. Furthermore, patients who get ASCT have higher risk of developing secondary malignancies, worse quality of life, and higher long-term morbidity with other conditions,” Dr. Landgren said.

He cited the MAIA trial administered daratumumab and lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (DRd) to patients who were too old or too frail to qualify for ASCT. Over half of patients in the DRd arm of MAIA had an estimated progression-free survival rate at 60 months.

“Furthermore, GT and the MANHATTAN clinical trials showed that we can safely add CD38-targeted monoclonal antibodies to standard combination therapies [lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (KRd)], resulting in higher rates of minimal-residual-disease (MRD) negativity. That means modern four-drug combination therapies [DR-RVd and DR-KRd] will allow more [and more newly diagnosed] MM patients to achieve MRD negativity in the absence of ASCT,” Dr. Landgren concluded.

Asked to comment on the two viewpoints, Joshua Richter, MD, director of myeloma treatment at the Blavatnik Family Center at Chelsea Mount Sinai, New York, said: “With some patients, we can get similar outcomes, whether or not we do a transplant. Doctors need to be better at choosing who really needs ASCT. Older people with standard-risk disease or people who achieve MRD-negative status after pharmacological treatment might not need to receive a transplant as much as those who have bulk disease or high-risk cytogenetics.

“Although ASCT might not be the best frontline option for everyone, collecting cells from most patients and storing them has many advantages. It allows us to do have the option of ASCT in later lines of therapy. In some patients with low blood counts, we can use stored cells to reboot their marrow and make them eligible for trials of promising new drugs,” Dr. Richter said.

Dr. Krishnan disclosed relationships with Takeda, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, Pfizer, Adaptive, Regeneron, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Artiva, and Sutro. Dr. Landgren reported ties with Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Takedam Glenmark, Juno, Pfizer, Merck, and others. Dr. Richter disclosed relationships with Janssen, BMS, and Takeda.

NEW YORK –

Hematologist-oncologists whose top priority is ensuring that patients have the best chance of progression-free survival (PFS) will continue to choose ASCT as a best practice, argued Amrita Krishnan, MD, hematologist at the Judy and Bernard Briskin Center for Multiple Myeloma Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, Calif.

A differing perspective was presented by C. Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, hematologist at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami. Dr. Landgren cited evidence that, for newly diagnosed MM patients treated successfully with modern combination therapies, ASCT is not a mandatory treatment step before starting maintenance therapy.

Making a case for ASCT as the SoC, Dr. Krishnan noted, “based on the DETERMINATION trial [DT], there is far superior rate of PFS with patients who get ASCT up front, compared patients who got only conventional chemotherapy with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone [RVd]. PFS is the endpoint we look for in our treatment regimens.

“If you don’t use ASCT up front, you may lose the opportunity at later relapse. This is not to say that transplant is the only tool at our disposal. It is just an indispensable one. The GRIFFIN trial [GT] has shown us that robust combinations of drugs [both RVd and dexamethasone +RVd] can improve patient outcomes both before and after ASCT,” Dr. Krishnan concluded.

In his presentation, Dr. Landgren stated that, in the DT, while PFS is prolonged by the addition of ASCT to RVd, adding ASCT did not significantly increase overall survival (OS) rates. He added that treatment-related AEs of grade 3+ occurred in only 78.2% of patients on RVd versus 94.2% of RVd + ASCT patients.

“ASCT should not be the SoC frontline treatment in MM because it does not prolong OS. The IFM trial and the DT both show that there is no difference in OS between drug combination therapy followed by transplant and maintenance versus combination therapy alone, followed by transplant and maintenance. Furthermore, patients who get ASCT have higher risk of developing secondary malignancies, worse quality of life, and higher long-term morbidity with other conditions,” Dr. Landgren said.

He cited the MAIA trial administered daratumumab and lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (DRd) to patients who were too old or too frail to qualify for ASCT. Over half of patients in the DRd arm of MAIA had an estimated progression-free survival rate at 60 months.

“Furthermore, GT and the MANHATTAN clinical trials showed that we can safely add CD38-targeted monoclonal antibodies to standard combination therapies [lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (KRd)], resulting in higher rates of minimal-residual-disease (MRD) negativity. That means modern four-drug combination therapies [DR-RVd and DR-KRd] will allow more [and more newly diagnosed] MM patients to achieve MRD negativity in the absence of ASCT,” Dr. Landgren concluded.

Asked to comment on the two viewpoints, Joshua Richter, MD, director of myeloma treatment at the Blavatnik Family Center at Chelsea Mount Sinai, New York, said: “With some patients, we can get similar outcomes, whether or not we do a transplant. Doctors need to be better at choosing who really needs ASCT. Older people with standard-risk disease or people who achieve MRD-negative status after pharmacological treatment might not need to receive a transplant as much as those who have bulk disease or high-risk cytogenetics.

“Although ASCT might not be the best frontline option for everyone, collecting cells from most patients and storing them has many advantages. It allows us to do have the option of ASCT in later lines of therapy. In some patients with low blood counts, we can use stored cells to reboot their marrow and make them eligible for trials of promising new drugs,” Dr. Richter said.

Dr. Krishnan disclosed relationships with Takeda, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, Pfizer, Adaptive, Regeneron, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Artiva, and Sutro. Dr. Landgren reported ties with Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Takedam Glenmark, Juno, Pfizer, Merck, and others. Dr. Richter disclosed relationships with Janssen, BMS, and Takeda.

NEW YORK –

Hematologist-oncologists whose top priority is ensuring that patients have the best chance of progression-free survival (PFS) will continue to choose ASCT as a best practice, argued Amrita Krishnan, MD, hematologist at the Judy and Bernard Briskin Center for Multiple Myeloma Research, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, Calif.

A differing perspective was presented by C. Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, hematologist at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami. Dr. Landgren cited evidence that, for newly diagnosed MM patients treated successfully with modern combination therapies, ASCT is not a mandatory treatment step before starting maintenance therapy.

Making a case for ASCT as the SoC, Dr. Krishnan noted, “based on the DETERMINATION trial [DT], there is far superior rate of PFS with patients who get ASCT up front, compared patients who got only conventional chemotherapy with lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone [RVd]. PFS is the endpoint we look for in our treatment regimens.

“If you don’t use ASCT up front, you may lose the opportunity at later relapse. This is not to say that transplant is the only tool at our disposal. It is just an indispensable one. The GRIFFIN trial [GT] has shown us that robust combinations of drugs [both RVd and dexamethasone +RVd] can improve patient outcomes both before and after ASCT,” Dr. Krishnan concluded.

In his presentation, Dr. Landgren stated that, in the DT, while PFS is prolonged by the addition of ASCT to RVd, adding ASCT did not significantly increase overall survival (OS) rates. He added that treatment-related AEs of grade 3+ occurred in only 78.2% of patients on RVd versus 94.2% of RVd + ASCT patients.

“ASCT should not be the SoC frontline treatment in MM because it does not prolong OS. The IFM trial and the DT both show that there is no difference in OS between drug combination therapy followed by transplant and maintenance versus combination therapy alone, followed by transplant and maintenance. Furthermore, patients who get ASCT have higher risk of developing secondary malignancies, worse quality of life, and higher long-term morbidity with other conditions,” Dr. Landgren said.

He cited the MAIA trial administered daratumumab and lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (DRd) to patients who were too old or too frail to qualify for ASCT. Over half of patients in the DRd arm of MAIA had an estimated progression-free survival rate at 60 months.

“Furthermore, GT and the MANHATTAN clinical trials showed that we can safely add CD38-targeted monoclonal antibodies to standard combination therapies [lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (KRd)], resulting in higher rates of minimal-residual-disease (MRD) negativity. That means modern four-drug combination therapies [DR-RVd and DR-KRd] will allow more [and more newly diagnosed] MM patients to achieve MRD negativity in the absence of ASCT,” Dr. Landgren concluded.

Asked to comment on the two viewpoints, Joshua Richter, MD, director of myeloma treatment at the Blavatnik Family Center at Chelsea Mount Sinai, New York, said: “With some patients, we can get similar outcomes, whether or not we do a transplant. Doctors need to be better at choosing who really needs ASCT. Older people with standard-risk disease or people who achieve MRD-negative status after pharmacological treatment might not need to receive a transplant as much as those who have bulk disease or high-risk cytogenetics.

“Although ASCT might not be the best frontline option for everyone, collecting cells from most patients and storing them has many advantages. It allows us to do have the option of ASCT in later lines of therapy. In some patients with low blood counts, we can use stored cells to reboot their marrow and make them eligible for trials of promising new drugs,” Dr. Richter said.

Dr. Krishnan disclosed relationships with Takeda, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, Pfizer, Adaptive, Regeneron, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Artiva, and Sutro. Dr. Landgren reported ties with Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Takedam Glenmark, Juno, Pfizer, Merck, and others. Dr. Richter disclosed relationships with Janssen, BMS, and Takeda.

AT 2023 GREAT DEBATES AND UPDATES HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES CONFERENCE

Motixafortide may improve MM outcomes

Motixafortide, a novel cyclic-peptide CXCR4 inhibitor with extended in vivo activity , appears to increase the number of stem cells that can be harvested from transplant candidates, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful transplant, the authors reported.

An application for a new drug approval is currently under review by the Food and Drug Administration.

In the prospective, international, phase 3 GENESIS clinical trial , motixafortide plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) – the standard therapy for mobilizing stem cells – significantly increased the number stem cells harvested, when compared with standard therapy plus placebo. After one collection procedure, the combination approach allowed for harvesting of an optimal number of cells in 88% versus 9% of patients who received G-CSF plus placebo. After two collections, optimal collection occurred in 92% versus 26% of patients in the groups, respectively, first author Zachary D. Crees, MD, and colleagues found.

Motixafortide plus G-CSF was also associated with a tenfold increase in the number of primitive stem cells that could be collected. These stem cells are particularly effective for reconstituting red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets, which all are important for patients’ recovery, they noted.

Stem cells mobilized by motixafortide were also associated with increased expression of genes and genetic pathways involved in self-renewal and regeneration, which are also of benefit for increasing the effectiveness of stem cell transplantation.

The findings were published in Nature Medicine.

“Stem cell transplantation is central to the treatment of multiple myeloma, but some patients don’t see as much benefit because standard therapies can’t harvest enough stem cells for the transplant to be effective, senior author John F. DiPersio, MD, PhD, stated in a news release . “This study suggests motixafortide works extremely well in combination with [G-CSF] in mobilizing stem cells in patients with multiple myeloma.

“The study also found that the combination worked rapidly and was generally well tolerated by patients,” added Dr. DiPersio, the Virginia E. & Sam J. Goldman Professor of Medicine at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University.

Dr. DiPersio is the lead author of another study investigating therapies beyond stem cell transplants. He and his colleagues recently reported the first comprehensive genomic and protein-based analysis of bone marrow samples from patients with multiple myeloma in an effort to identify targets for immunotherapies.

That study, published online in Cancer Research, identified 53 genes that could be targets, including 38 that are responsible for creating abnormal proteins on the surface of multiple myeloma cells; 11 of the 38 had not been previously identified as potential targets.

Dr. DiPersio and Dr. Crees, an assistant professor of medicine and the assistant clinical director of the Washington University Center for Gene and Cellular Immunotherapy, are also evaluating motixafortide’s potential for mobilizing stem cells to support “the genetic correction of the inherited disease sickle cell anemia.”

“This work is of particular importance because patients with sickle cell disease can’t be treated with G-CSF … due to dangerous side effects,” the news release stated. “The hope is that development of a novel, effective, and well-tolerated stem cell mobilizing regimen for a viral-based gene therapy approach using CRISPR-based gene editing will lead to improved outcomes for patients with sickle cell disease.”

The study published in Nature Medicine was supported by the National Institutes of Health and BioLineRx, which makes motixafortide. The study published in Cancer Research was supported by the Paula C. And Rodger O. Riney Blood Cancer Research Fund and the National Cancer Institute.

Dr. Crees reported research funding from BioLineRx. Dr. DiPersio reported relationships with Magenta Therapeutics, WUGEN, Incyte, RiverVest Venture Partners, Cellworks Group, Amphivena Therapeutics, NeoImmune Tech, Macrogenics, and BioLineRx.

Correction, 4/26/23: The headline on an earlier version of this article mischaracterized the study findings.

Motixafortide, a novel cyclic-peptide CXCR4 inhibitor with extended in vivo activity , appears to increase the number of stem cells that can be harvested from transplant candidates, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful transplant, the authors reported.

An application for a new drug approval is currently under review by the Food and Drug Administration.

In the prospective, international, phase 3 GENESIS clinical trial , motixafortide plus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) – the standard therapy for mobilizing stem cells – significantly increased the number stem cells harvested, when compared with standard therapy plus placebo. After one collection procedure, the combination approach allowed for harvesting of an optimal number of cells in 88% versus 9% of patients who received G-CSF plus placebo. After two collections, optimal collection occurred in 92% versus 26% of patients in the groups, respectively, first author Zachary D. Crees, MD, and colleagues found.

Motixafortide plus G-CSF was also associated with a tenfold increase in the number of primitive stem cells that could be collected. These stem cells are particularly effective for reconstituting red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets, which all are important for patients’ recovery, they noted.

Stem cells mobilized by motixafortide were also associated with increased expression of genes and genetic pathways involved in self-renewal and regeneration, which are also of benefit for increasing the effectiveness of stem cell transplantation.

The findings were published in Nature Medicine.

“Stem cell transplantation is central to the treatment of multiple myeloma, but some patients don’t see as much benefit because standard therapies can’t harvest enough stem cells for the transplant to be effective, senior author John F. DiPersio, MD, PhD, stated in a news release . “This study suggests motixafortide works extremely well in combination with [G-CSF] in mobilizing stem cells in patients with multiple myeloma.

“The study also found that the combination worked rapidly and was generally well tolerated by patients,” added Dr. DiPersio, the Virginia E. & Sam J. Goldman Professor of Medicine at Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University.

Dr. DiPersio is the lead author of another study investigating therapies beyond stem cell transplants. He and his colleagues recently reported the first comprehensive genomic and protein-based analysis of bone marrow samples from patients with multiple myeloma in an effort to identify targets for immunotherapies.

That study, published online in Cancer Research, identified 53 genes that could be targets, including 38 that are responsible for creating abnormal proteins on the surface of multiple myeloma cells; 11 of the 38 had not been previously identified as potential targets.

Dr. DiPersio and Dr. Crees, an assistant professor of medicine and the assistant clinical director of the Washington University Center for Gene and Cellular Immunotherapy, are also evaluating motixafortide’s potential for mobilizing stem cells to support “the genetic correction of the inherited disease sickle cell anemia.”