User login

Teenagers get in the queue for COVID-19 vaccines

The vaccinations can’t come soon enough for parents like Stacy Hillenburg, a developmental therapist in Aurora, Ill., whose 9-year-old son takes immunosuppressants because he had a heart transplant when he was 7 weeks old. Although school-age children aren’t yet included in clinical trials, if her 12- and 13-year-old daughters could get vaccinated, along with both parents, then the family could relax some of the protocols they currently follow to prevent infection.

Whenever they are around other people, even masked and socially distanced, they come home and immediately shower and change their clothes. So far, no one in the family has been infected with COVID, but the anxiety is ever-present. “I can’t wait for it to come out,” Ms. Hillenburg said of a pediatric COVID vaccine. “It will ease my mind so much.”

She isn’t alone in that anticipation. In the fall, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other pediatric vaccine experts urged faster action on pediatric vaccine trials and worried that children would be left behind as adults gained protection from COVID. But recent developments have eased those concerns.

“Over the next couple of months, we will be doing trials in an age-deescalation manner,” with studies moving gradually to younger children, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, chief medical adviser on COVID-19 to the president, said in a coronavirus response team briefing on Jan. 29. “So that hopefully, as we get to the late spring and summer, we will have children being able to be vaccinated.”

Pfizer completed enrollment of 2,259 teens aged 12-15 years in late January and expects to move forward with a separate pediatric trial of children aged 5-11 years by this spring, Keanna Ghazvini, senior associate for global media relations at Pfizer, said in an interview.

Enrollment in Moderna’s TeenCove study of adolescents ages 12-17 years began slowly in late December, but the pace has since picked up, said company spokesperson Colleen Hussey. “We continue to bring clinical trial sites online, and we are on track to provide updated data around mid-year 2021.” A trial extension in children 11 years and younger is expected to begin later in 2021.

Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca said they expect to begin adolescent trials in early 2021, according to data shared by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. An interim analysis of J&J’s Janssen COVID-19 vaccine trial data, released on Jan. 29, showed it was 72% effective in US participants aged 18 years or older. AstraZeneca’s U.S. trial in adults is ongoing.

Easing the burden

Vaccination could lessen children’s risk of severe disease as well as the social and emotional burdens of the pandemic, says James Campbell, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore, which was involved in the Moderna and early-phase Pfizer trials. He coauthored a September 2020 article in Clinical Infectious Diseases titled: “Warp Speed for COVID-19 vaccines: Why are children stuck in neutral?”

The adolescent trials are a vital step to ensure timely vaccine access for teens and younger children. “It is reasonable, when you have limited vaccine, that your rollout goes to the highest priority and then moves to lower and lower priorities. In adults, we’re just saying: ‘Wait your turn,’ ” he said of the current vaccination effort. “If we didn’t have the [vaccine trial] data in children, we’d be saying: ‘You don’t have a turn.’ ”

As the pandemic has worn on, the burden on children has grown. As of Tuesday, 269 children had died of COVID-19. That is well above the highest annual death toll recorded during a regular flu season – 188 flu deaths among children and adolescents under 18 in the 2019-2020 and 2017-2018 flu seasons.

Children are less likely to transmit COVID-19 in their household than adults, according to a meta-analysis of 54 studies published in JAMA Network Open. But that does not necessarily mean children are less infectious, the authors said, noting that unmeasured factors could have affected the spread of infection among adults.

Moreover, children and adolescents need protection from COVID infection – and from the potential for severe disease or lingering effects – and, given that there are 74 million children and teens in the United States, their vaccination is an important part of stopping the pandemic, said Grace Lee, MD, professor of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University, and cochair of ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup.

“In order to interrupt transmission, I don’t see how we’re going to do that without vaccinating children and adolescents,” she said.

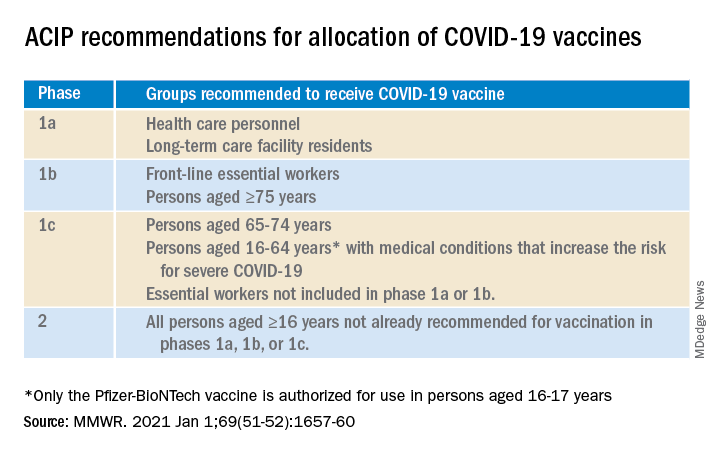

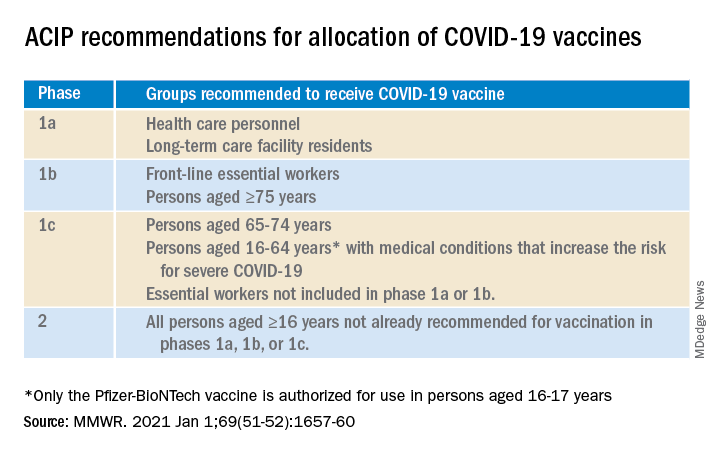

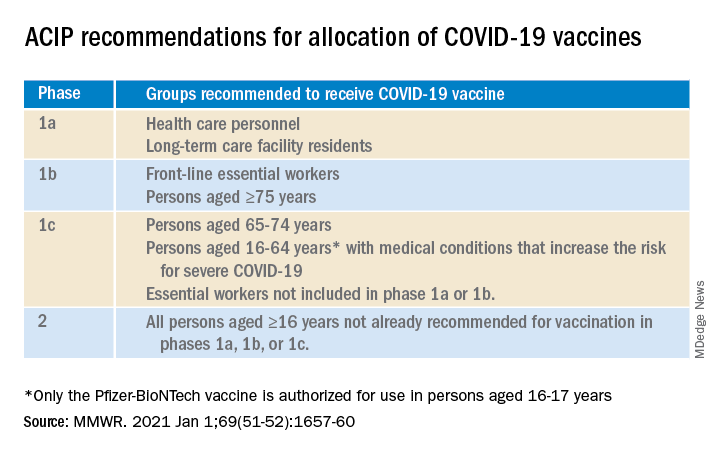

Dr. Lee said her 16-year-old daughter misses the normal teenage social life and is excited about getting the vaccine when she is eligible. (Adolescents without high-risk conditions are in the lowest vaccination tier, according to ACIP recommendations.) “There is truly individual protection to be gained,” Dr. Lee said.

She noted that researchers continue to assess the immune responses to the adult vaccines – even looking at immune characteristics of the small percentage of people who aren’t protected from infection – and that information helps in the evaluation of the pediatric immune responses. As the trials expand to younger children and infants, dosing will be a major focus. “How many doses do they need they need to receive the same immunity? Safety considerations will be critically important,” she said.

Teen trials underway

Pfizer/BioNTech extended its adult trial to 16- and 17-year-olds in October, which enabled older teens to be included in its emergency-use authorization. They and younger teens, ages 12-15, receive the same dose as adults.

The ongoing trials with Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are immunobridging trials, designed to study safety and immunogenicity. Investigators will compare the teens’ immune response with the findings from the larger adult trials. When the trials expand to school-age children (6-12 years), protocols call for testing the safety and immunogenicity of a half-dose vaccine as well as the full dose.

Children ages 2-5 years and infants and toddlers will be enrolled in future trials, studying safety and immunogenicity of full, half, or even quarter dosages. The Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003 requires licensed vaccines to be tested for safety and efficacy in children, unless they are not appropriate for a pediatric population.

Demand for the teen trials has been strong. At Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 259 teenagers joined the Pfizer/BioNTech trial, but some teenagers were turned away when the trial’s national enrollment closed in late January.

“Many of the children are having no side effects, and if they are, they’re having the same [effects] as the young adults – local redness or pain, fatigue, and headaches,” said Robert Frenck, MD, director of the Cincinnati Children’s Gamble Program for Clinical Studies.

Parents may share some of the vaccine hesitancy that has affected adult vaccination. But that is balanced by the hope that vaccines will end the pandemic and usher in a new normal. “If it looks like [vaccines] will increase the likelihood of children returning to school safely, that may be a motivating factor,” Dr. Frenck said.

Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the pediatric infectious disease service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, was initially cautious about the extension of vaccination to adolescents. A member of the Vaccine and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, which evaluates data and makes recommendations to the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Meissner initially abstained in the vote on the Pfizer/BioNTech emergency-use authorization for people 16 and older.

He noted that, at the time the committee reviewed the Pfizer vaccine, the company had data available for just 134 teenagers, half of whom received a placebo. But the vaccination of 34 million adults has provided robust data about the vaccine’s safety, and the trial expansion into adolescents is important.

“I’m comfortable with the way these trials are going now,” he said. “This is the way I was hoping they would go.”

Ms. Hillenburg is on the parent advisory board of Voices for Vaccines, an organization of parents supporting vaccination that is affiliated with the Task Force for Global Health, an Atlanta-based independent public health organization. Dr. Campbell’s institution has received funds to conduct clinical trials from the National Institutes of Health and several companies, including Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Moderna. He has served pro bono on many safety and data monitoring committees. Dr. Frenck’s institution is receiving funds to conduct the Pfizer trial. In the past 5 years, he has also participated in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Meissa vaccines. Dr. Lee and Dr. Meissner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vaccinations can’t come soon enough for parents like Stacy Hillenburg, a developmental therapist in Aurora, Ill., whose 9-year-old son takes immunosuppressants because he had a heart transplant when he was 7 weeks old. Although school-age children aren’t yet included in clinical trials, if her 12- and 13-year-old daughters could get vaccinated, along with both parents, then the family could relax some of the protocols they currently follow to prevent infection.

Whenever they are around other people, even masked and socially distanced, they come home and immediately shower and change their clothes. So far, no one in the family has been infected with COVID, but the anxiety is ever-present. “I can’t wait for it to come out,” Ms. Hillenburg said of a pediatric COVID vaccine. “It will ease my mind so much.”

She isn’t alone in that anticipation. In the fall, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other pediatric vaccine experts urged faster action on pediatric vaccine trials and worried that children would be left behind as adults gained protection from COVID. But recent developments have eased those concerns.

“Over the next couple of months, we will be doing trials in an age-deescalation manner,” with studies moving gradually to younger children, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, chief medical adviser on COVID-19 to the president, said in a coronavirus response team briefing on Jan. 29. “So that hopefully, as we get to the late spring and summer, we will have children being able to be vaccinated.”

Pfizer completed enrollment of 2,259 teens aged 12-15 years in late January and expects to move forward with a separate pediatric trial of children aged 5-11 years by this spring, Keanna Ghazvini, senior associate for global media relations at Pfizer, said in an interview.

Enrollment in Moderna’s TeenCove study of adolescents ages 12-17 years began slowly in late December, but the pace has since picked up, said company spokesperson Colleen Hussey. “We continue to bring clinical trial sites online, and we are on track to provide updated data around mid-year 2021.” A trial extension in children 11 years and younger is expected to begin later in 2021.

Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca said they expect to begin adolescent trials in early 2021, according to data shared by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. An interim analysis of J&J’s Janssen COVID-19 vaccine trial data, released on Jan. 29, showed it was 72% effective in US participants aged 18 years or older. AstraZeneca’s U.S. trial in adults is ongoing.

Easing the burden

Vaccination could lessen children’s risk of severe disease as well as the social and emotional burdens of the pandemic, says James Campbell, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore, which was involved in the Moderna and early-phase Pfizer trials. He coauthored a September 2020 article in Clinical Infectious Diseases titled: “Warp Speed for COVID-19 vaccines: Why are children stuck in neutral?”

The adolescent trials are a vital step to ensure timely vaccine access for teens and younger children. “It is reasonable, when you have limited vaccine, that your rollout goes to the highest priority and then moves to lower and lower priorities. In adults, we’re just saying: ‘Wait your turn,’ ” he said of the current vaccination effort. “If we didn’t have the [vaccine trial] data in children, we’d be saying: ‘You don’t have a turn.’ ”

As the pandemic has worn on, the burden on children has grown. As of Tuesday, 269 children had died of COVID-19. That is well above the highest annual death toll recorded during a regular flu season – 188 flu deaths among children and adolescents under 18 in the 2019-2020 and 2017-2018 flu seasons.

Children are less likely to transmit COVID-19 in their household than adults, according to a meta-analysis of 54 studies published in JAMA Network Open. But that does not necessarily mean children are less infectious, the authors said, noting that unmeasured factors could have affected the spread of infection among adults.

Moreover, children and adolescents need protection from COVID infection – and from the potential for severe disease or lingering effects – and, given that there are 74 million children and teens in the United States, their vaccination is an important part of stopping the pandemic, said Grace Lee, MD, professor of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University, and cochair of ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup.

“In order to interrupt transmission, I don’t see how we’re going to do that without vaccinating children and adolescents,” she said.

Dr. Lee said her 16-year-old daughter misses the normal teenage social life and is excited about getting the vaccine when she is eligible. (Adolescents without high-risk conditions are in the lowest vaccination tier, according to ACIP recommendations.) “There is truly individual protection to be gained,” Dr. Lee said.

She noted that researchers continue to assess the immune responses to the adult vaccines – even looking at immune characteristics of the small percentage of people who aren’t protected from infection – and that information helps in the evaluation of the pediatric immune responses. As the trials expand to younger children and infants, dosing will be a major focus. “How many doses do they need they need to receive the same immunity? Safety considerations will be critically important,” she said.

Teen trials underway

Pfizer/BioNTech extended its adult trial to 16- and 17-year-olds in October, which enabled older teens to be included in its emergency-use authorization. They and younger teens, ages 12-15, receive the same dose as adults.

The ongoing trials with Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are immunobridging trials, designed to study safety and immunogenicity. Investigators will compare the teens’ immune response with the findings from the larger adult trials. When the trials expand to school-age children (6-12 years), protocols call for testing the safety and immunogenicity of a half-dose vaccine as well as the full dose.

Children ages 2-5 years and infants and toddlers will be enrolled in future trials, studying safety and immunogenicity of full, half, or even quarter dosages. The Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003 requires licensed vaccines to be tested for safety and efficacy in children, unless they are not appropriate for a pediatric population.

Demand for the teen trials has been strong. At Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 259 teenagers joined the Pfizer/BioNTech trial, but some teenagers were turned away when the trial’s national enrollment closed in late January.

“Many of the children are having no side effects, and if they are, they’re having the same [effects] as the young adults – local redness or pain, fatigue, and headaches,” said Robert Frenck, MD, director of the Cincinnati Children’s Gamble Program for Clinical Studies.

Parents may share some of the vaccine hesitancy that has affected adult vaccination. But that is balanced by the hope that vaccines will end the pandemic and usher in a new normal. “If it looks like [vaccines] will increase the likelihood of children returning to school safely, that may be a motivating factor,” Dr. Frenck said.

Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the pediatric infectious disease service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, was initially cautious about the extension of vaccination to adolescents. A member of the Vaccine and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, which evaluates data and makes recommendations to the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Meissner initially abstained in the vote on the Pfizer/BioNTech emergency-use authorization for people 16 and older.

He noted that, at the time the committee reviewed the Pfizer vaccine, the company had data available for just 134 teenagers, half of whom received a placebo. But the vaccination of 34 million adults has provided robust data about the vaccine’s safety, and the trial expansion into adolescents is important.

“I’m comfortable with the way these trials are going now,” he said. “This is the way I was hoping they would go.”

Ms. Hillenburg is on the parent advisory board of Voices for Vaccines, an organization of parents supporting vaccination that is affiliated with the Task Force for Global Health, an Atlanta-based independent public health organization. Dr. Campbell’s institution has received funds to conduct clinical trials from the National Institutes of Health and several companies, including Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Moderna. He has served pro bono on many safety and data monitoring committees. Dr. Frenck’s institution is receiving funds to conduct the Pfizer trial. In the past 5 years, he has also participated in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Meissa vaccines. Dr. Lee and Dr. Meissner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The vaccinations can’t come soon enough for parents like Stacy Hillenburg, a developmental therapist in Aurora, Ill., whose 9-year-old son takes immunosuppressants because he had a heart transplant when he was 7 weeks old. Although school-age children aren’t yet included in clinical trials, if her 12- and 13-year-old daughters could get vaccinated, along with both parents, then the family could relax some of the protocols they currently follow to prevent infection.

Whenever they are around other people, even masked and socially distanced, they come home and immediately shower and change their clothes. So far, no one in the family has been infected with COVID, but the anxiety is ever-present. “I can’t wait for it to come out,” Ms. Hillenburg said of a pediatric COVID vaccine. “It will ease my mind so much.”

She isn’t alone in that anticipation. In the fall, the American Academy of Pediatrics and other pediatric vaccine experts urged faster action on pediatric vaccine trials and worried that children would be left behind as adults gained protection from COVID. But recent developments have eased those concerns.

“Over the next couple of months, we will be doing trials in an age-deescalation manner,” with studies moving gradually to younger children, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, chief medical adviser on COVID-19 to the president, said in a coronavirus response team briefing on Jan. 29. “So that hopefully, as we get to the late spring and summer, we will have children being able to be vaccinated.”

Pfizer completed enrollment of 2,259 teens aged 12-15 years in late January and expects to move forward with a separate pediatric trial of children aged 5-11 years by this spring, Keanna Ghazvini, senior associate for global media relations at Pfizer, said in an interview.

Enrollment in Moderna’s TeenCove study of adolescents ages 12-17 years began slowly in late December, but the pace has since picked up, said company spokesperson Colleen Hussey. “We continue to bring clinical trial sites online, and we are on track to provide updated data around mid-year 2021.” A trial extension in children 11 years and younger is expected to begin later in 2021.

Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca said they expect to begin adolescent trials in early 2021, according to data shared by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. An interim analysis of J&J’s Janssen COVID-19 vaccine trial data, released on Jan. 29, showed it was 72% effective in US participants aged 18 years or older. AstraZeneca’s U.S. trial in adults is ongoing.

Easing the burden

Vaccination could lessen children’s risk of severe disease as well as the social and emotional burdens of the pandemic, says James Campbell, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Maryland’s Center for Vaccine Development in Baltimore, which was involved in the Moderna and early-phase Pfizer trials. He coauthored a September 2020 article in Clinical Infectious Diseases titled: “Warp Speed for COVID-19 vaccines: Why are children stuck in neutral?”

The adolescent trials are a vital step to ensure timely vaccine access for teens and younger children. “It is reasonable, when you have limited vaccine, that your rollout goes to the highest priority and then moves to lower and lower priorities. In adults, we’re just saying: ‘Wait your turn,’ ” he said of the current vaccination effort. “If we didn’t have the [vaccine trial] data in children, we’d be saying: ‘You don’t have a turn.’ ”

As the pandemic has worn on, the burden on children has grown. As of Tuesday, 269 children had died of COVID-19. That is well above the highest annual death toll recorded during a regular flu season – 188 flu deaths among children and adolescents under 18 in the 2019-2020 and 2017-2018 flu seasons.

Children are less likely to transmit COVID-19 in their household than adults, according to a meta-analysis of 54 studies published in JAMA Network Open. But that does not necessarily mean children are less infectious, the authors said, noting that unmeasured factors could have affected the spread of infection among adults.

Moreover, children and adolescents need protection from COVID infection – and from the potential for severe disease or lingering effects – and, given that there are 74 million children and teens in the United States, their vaccination is an important part of stopping the pandemic, said Grace Lee, MD, professor of pediatrics at Stanford (Calif.) University, and cochair of ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Subgroup.

“In order to interrupt transmission, I don’t see how we’re going to do that without vaccinating children and adolescents,” she said.

Dr. Lee said her 16-year-old daughter misses the normal teenage social life and is excited about getting the vaccine when she is eligible. (Adolescents without high-risk conditions are in the lowest vaccination tier, according to ACIP recommendations.) “There is truly individual protection to be gained,” Dr. Lee said.

She noted that researchers continue to assess the immune responses to the adult vaccines – even looking at immune characteristics of the small percentage of people who aren’t protected from infection – and that information helps in the evaluation of the pediatric immune responses. As the trials expand to younger children and infants, dosing will be a major focus. “How many doses do they need they need to receive the same immunity? Safety considerations will be critically important,” she said.

Teen trials underway

Pfizer/BioNTech extended its adult trial to 16- and 17-year-olds in October, which enabled older teens to be included in its emergency-use authorization. They and younger teens, ages 12-15, receive the same dose as adults.

The ongoing trials with Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are immunobridging trials, designed to study safety and immunogenicity. Investigators will compare the teens’ immune response with the findings from the larger adult trials. When the trials expand to school-age children (6-12 years), protocols call for testing the safety and immunogenicity of a half-dose vaccine as well as the full dose.

Children ages 2-5 years and infants and toddlers will be enrolled in future trials, studying safety and immunogenicity of full, half, or even quarter dosages. The Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003 requires licensed vaccines to be tested for safety and efficacy in children, unless they are not appropriate for a pediatric population.

Demand for the teen trials has been strong. At Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, 259 teenagers joined the Pfizer/BioNTech trial, but some teenagers were turned away when the trial’s national enrollment closed in late January.

“Many of the children are having no side effects, and if they are, they’re having the same [effects] as the young adults – local redness or pain, fatigue, and headaches,” said Robert Frenck, MD, director of the Cincinnati Children’s Gamble Program for Clinical Studies.

Parents may share some of the vaccine hesitancy that has affected adult vaccination. But that is balanced by the hope that vaccines will end the pandemic and usher in a new normal. “If it looks like [vaccines] will increase the likelihood of children returning to school safely, that may be a motivating factor,” Dr. Frenck said.

Cody Meissner, MD, chief of the pediatric infectious disease service at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, was initially cautious about the extension of vaccination to adolescents. A member of the Vaccine and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, which evaluates data and makes recommendations to the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Meissner initially abstained in the vote on the Pfizer/BioNTech emergency-use authorization for people 16 and older.

He noted that, at the time the committee reviewed the Pfizer vaccine, the company had data available for just 134 teenagers, half of whom received a placebo. But the vaccination of 34 million adults has provided robust data about the vaccine’s safety, and the trial expansion into adolescents is important.

“I’m comfortable with the way these trials are going now,” he said. “This is the way I was hoping they would go.”

Ms. Hillenburg is on the parent advisory board of Voices for Vaccines, an organization of parents supporting vaccination that is affiliated with the Task Force for Global Health, an Atlanta-based independent public health organization. Dr. Campbell’s institution has received funds to conduct clinical trials from the National Institutes of Health and several companies, including Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Moderna. He has served pro bono on many safety and data monitoring committees. Dr. Frenck’s institution is receiving funds to conduct the Pfizer trial. In the past 5 years, he has also participated in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Meissa vaccines. Dr. Lee and Dr. Meissner disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CLL, MBL had lower response rates to flu vaccination, compared with healthy adults

Immunogenicity of the high-dose influenza vaccine (HD IIV3) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL, the precursor state to CLL) was found lower than reported in healthy adults according to a report in Vaccine.

In addition, immunogenicity to influenza B was found to be greater in those patients with MBL, compared with those with CLL.

“Acute and chronic leukemia patients hospitalized with influenza infection document a case fatality rate of 25%-37%,” according to Jennifer A. Whitaker, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues in pointing out the importance of their study.

The prospective pilot study assessed the humoral immune responses of patients to the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 HD IIV3 (Fluzone High-Dose; Sanofi Pasteur), which was administered as part of routine clinical care in 30 patients (17 with previously untreated CLL and 13 with MBL). The median patient age was 69.5 years.

The primary outcomes were seroconversion and seroprotection, as measured by hemagglutination inhibition assay (HAI).

Lower response rate

At day 28 post vaccination, the seroprotection rates for the overall cohort were 19/30 (63.3%) for A/H1N1, 21/23 (91.3%) for A/H3N2, and 13/30 (43.3%) for influenza B. Patients with MBL achieved significantly higher day 28 HAI geometric mean titers (GMT), compared with CLL patients (54.1 vs. 12.1]; P = .01), In addition, MBL patients achieved higher day 28 seroprotection rates against the influenza B vaccine strain virus than did those with CLL (76.9% vs. 17.6%; P = .002). Seroconversion rates for the overall cohort were 3/30 (10%) for A/H1N1; 5/23 (21.7%) for A/H3N2; and 3/30 (10%) for influenza B. No individual with CLL demonstrated seroconversion for influenza B, according to the researchers.

“Our studies reinforce rigorous adherence to vaccination strategies in patients with hematologic malignancy, including those with CLL, given the increased risk of serious complications among those experiencing influenza infection,” the authors stated.

“Even suboptimal responses to influenza vaccination can provide partial protection, reduce hospitalization rates, and/or prevent serious disease complications. Given the recent major issue with novel and aggressive viruses such COVID-19, we absolutely must continue with larger prospective studies to confirm these findings and evaluate vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza or other novel viruses in these populations,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Whitaker reported having no disclosures. Several of the coauthors reported financial relationships with a variety of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

Immunogenicity of the high-dose influenza vaccine (HD IIV3) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL, the precursor state to CLL) was found lower than reported in healthy adults according to a report in Vaccine.

In addition, immunogenicity to influenza B was found to be greater in those patients with MBL, compared with those with CLL.

“Acute and chronic leukemia patients hospitalized with influenza infection document a case fatality rate of 25%-37%,” according to Jennifer A. Whitaker, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues in pointing out the importance of their study.

The prospective pilot study assessed the humoral immune responses of patients to the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 HD IIV3 (Fluzone High-Dose; Sanofi Pasteur), which was administered as part of routine clinical care in 30 patients (17 with previously untreated CLL and 13 with MBL). The median patient age was 69.5 years.

The primary outcomes were seroconversion and seroprotection, as measured by hemagglutination inhibition assay (HAI).

Lower response rate

At day 28 post vaccination, the seroprotection rates for the overall cohort were 19/30 (63.3%) for A/H1N1, 21/23 (91.3%) for A/H3N2, and 13/30 (43.3%) for influenza B. Patients with MBL achieved significantly higher day 28 HAI geometric mean titers (GMT), compared with CLL patients (54.1 vs. 12.1]; P = .01), In addition, MBL patients achieved higher day 28 seroprotection rates against the influenza B vaccine strain virus than did those with CLL (76.9% vs. 17.6%; P = .002). Seroconversion rates for the overall cohort were 3/30 (10%) for A/H1N1; 5/23 (21.7%) for A/H3N2; and 3/30 (10%) for influenza B. No individual with CLL demonstrated seroconversion for influenza B, according to the researchers.

“Our studies reinforce rigorous adherence to vaccination strategies in patients with hematologic malignancy, including those with CLL, given the increased risk of serious complications among those experiencing influenza infection,” the authors stated.

“Even suboptimal responses to influenza vaccination can provide partial protection, reduce hospitalization rates, and/or prevent serious disease complications. Given the recent major issue with novel and aggressive viruses such COVID-19, we absolutely must continue with larger prospective studies to confirm these findings and evaluate vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza or other novel viruses in these populations,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Whitaker reported having no disclosures. Several of the coauthors reported financial relationships with a variety of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

Immunogenicity of the high-dose influenza vaccine (HD IIV3) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL, the precursor state to CLL) was found lower than reported in healthy adults according to a report in Vaccine.

In addition, immunogenicity to influenza B was found to be greater in those patients with MBL, compared with those with CLL.

“Acute and chronic leukemia patients hospitalized with influenza infection document a case fatality rate of 25%-37%,” according to Jennifer A. Whitaker, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues in pointing out the importance of their study.

The prospective pilot study assessed the humoral immune responses of patients to the 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 HD IIV3 (Fluzone High-Dose; Sanofi Pasteur), which was administered as part of routine clinical care in 30 patients (17 with previously untreated CLL and 13 with MBL). The median patient age was 69.5 years.

The primary outcomes were seroconversion and seroprotection, as measured by hemagglutination inhibition assay (HAI).

Lower response rate

At day 28 post vaccination, the seroprotection rates for the overall cohort were 19/30 (63.3%) for A/H1N1, 21/23 (91.3%) for A/H3N2, and 13/30 (43.3%) for influenza B. Patients with MBL achieved significantly higher day 28 HAI geometric mean titers (GMT), compared with CLL patients (54.1 vs. 12.1]; P = .01), In addition, MBL patients achieved higher day 28 seroprotection rates against the influenza B vaccine strain virus than did those with CLL (76.9% vs. 17.6%; P = .002). Seroconversion rates for the overall cohort were 3/30 (10%) for A/H1N1; 5/23 (21.7%) for A/H3N2; and 3/30 (10%) for influenza B. No individual with CLL demonstrated seroconversion for influenza B, according to the researchers.

“Our studies reinforce rigorous adherence to vaccination strategies in patients with hematologic malignancy, including those with CLL, given the increased risk of serious complications among those experiencing influenza infection,” the authors stated.

“Even suboptimal responses to influenza vaccination can provide partial protection, reduce hospitalization rates, and/or prevent serious disease complications. Given the recent major issue with novel and aggressive viruses such COVID-19, we absolutely must continue with larger prospective studies to confirm these findings and evaluate vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza or other novel viruses in these populations,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Whitaker reported having no disclosures. Several of the coauthors reported financial relationships with a variety of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

FROM VACCINE

The Veterans Health Administration Approach to COVID-19 Vaccine Allocation—Balancing Utility and Equity

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) COVID-19 vaccine allocation plan showcases several lessons for government and health care leaders in planning for future pandemics.1 Many state governments—underresourced and overwhelmed with other COVID-19 demands—have struggled to get COVID-19 vaccines into the arms of their residents.2 In contrast, the VHA was able to mobilize early to identify vaccine allocation guidelines and proactively prepare facilities to vaccinate VHA staff and veterans as soon as vaccines were approved under Emergency Use Authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In August 2020, VHA formed a COVID-19 Vaccine Integrated Project Team, composed of 6 subgroups: communications, distribution, education, measurement, policy, prioritization, and vaccine safety. The National Center for Ethics in Health Care weighed in on the ethical justification for the developed vaccination risk stratification framework, which was informed by, but not identical to, that recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.5

Prioritizing who gets early access to a potentially life-saving vaccine weighs heavily on those leaders charged with making such decisions. The ethics of scarce resource allocation and triage protocols that may be necessary in a pandemic are often in tension with the patient-centered clinical ethics that health care practitioners (HCPs) encounter. HCPs require assistance in appreciating the ethical rationale for this shift in focus from the preference of the individual to the common good. The same is true for the risk stratification criteria required when there is not sufficient vaccine for all those who could benefit from immunization. Decisions must be transparent to ensure widespread acceptance and trust in the vaccination process. The ethical reasoning and values that are the basis for allocation criteria must be clearly, compassionately, and consistently communicated to the public, as outlined below. Ethical questions or concerns involve a conflict between core values: one of the central tasks of ethical analysis is to identify the available ethical options to resolve value conflicts. Several ethical frameworks for vaccine allocation are available—each balances and weighs the primary values of equity, dignity, beneficence, and utility slightly differently.6

For example, utilitarian ethics looks to produce the most good and avoid the most harm for the greatest number of people. Within this framework, there can be different notions of “good,” for example, saving the most lives, the most life years, the most quality life years, or the lives of those who have more life “innings” ahead. The approach of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) focuses on saving the most lives in combination with avoiding suffering from serious illness, minimizing contagion, and preserving the essential workforce. Frameworks that give primacy to 1 notion of the good (ie, saving the most lives) may deprioritize other beneficial outcomes, such as allowing earlier return to work, school, and leisure activities that many find integral to human flourishing. Other ethical theories and principles may be used to support various allocation frameworks. For example, a pragmatic ethics approach might emphasize the importance of adapting the approach based on the evolving science and innovation surrounding COVID-19. Having more than 1 ethically defensible approach is common; the goal in ethics work is to be open to diversity of thought and reflect on the strength of one’s reasoning in resolving a core values conflict. We identify 2 central tenets of pandemic ethics that inform vaccine allocation.

1. Pandemic Ethics Requires Proactive Planning and Reevaluation of Continually Evolving Facts

There is an oft quoted saying among bioethicists: “Good ethics begins with good facts.” One obvious challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the difficulty accessing up-to-date facts to inform decision making. If a main goal of a vaccination plan is to minimize the incidence of serious or fatal COVID-19 disease and contagion, myriad data points are needed to identify the best way to do this. For example, if 2 doses of the same vaccine are needed, this impacts the logistics of identifying, inviting, and scheduling eligible individuals and staffing vaccine clinics as well as ensuring that sufficient personal protective equipment and rescue equipment/medication are available to treat allergic reactions. If the adverse effects of vaccines lead to staff absenteeism or vaccine hesitancy, this needs to be factored into logistics.7 Tailored messaging is important to reduce appointment no-shows and vaccine nonadopters.8 Transportation to vaccination sites is a relevant factor: how a vaccine is stored, thawed, and reconstituted and its shelf life impacts whether it can be transported after thawing and what must be provided on site.

Consideration of the multifaceted factors influencing a successful vaccination campaign requires proactive planning and the readiness to pivot when new information is revealed. For example, vaccine appointment no-shows should be anticipated along with a fair process for allocating unused vaccine that would otherwise be wasted. This is an example of responsible stewardship of a scarce and life-saving resource. A higher than anticipated no-show rate would require revisiting a facility’s approach to ensuring that waste is avoided while the process is perceived to be fair and transparent. Ethical theories and principles cannot do all the work here; mindful attention to detail and proactive, informed planning are critical. Fortunately, the VA is well resourced in this domain, whereas many state health departments floundered in their response, causing unnecessary vaccination delays.9

2. Utility: Necessary But Insufficient

Most ethical approaches recognize to some extent that seeking good and minimizing harm is of value. However, a strictly utilitarian approach is insufficient to address the core values in conflict surrounding how best to allocate limited doses of COVID-19 vaccine. For example, some may argue that prioritizing the elderly or those in long-term care facilities like VA’s community living centers because they have the highest COVID-19 mortality rate produces less net benefit than prioritizing younger veterans with comorbidities or certain higher risk essential workers. There are 2 important points to make here.

First, the VHA vaccination plan balances utility with other ethical principles, namely, treating people with equal concern, and addressing health inequities, including a focus on justice and valuing the worth and dignity of each person. Rather than giving everyone an equal chance via lottery, the prioritization plan recognizes that some people have greater need or would stand to better mitigate viral contagion and preserve the essential workforce if they were vaccinated earlier. However, the principle of justice requires that efforts are made to treat like cases the same to avoid perceptions of bias, and to demonstrate respect for the dignity of each individual by way of promoting a fair vaccination process.

This requires transparency, consistency, and delivery of respectful and accurate communication. For example, the VA recognizes that lifetime exposure to social injustice produces health inequities that make Black, Hispanic, and Native American persons more susceptible to contracting COVID-19 and suffering serious or fatal illness. The approach to addressing this inequity is by giving priority to those with higher risk factors. Again, this is an example of blending and balancing ethical principles of utility and justice—that is, recognizing and remedying social injustice is of value both because it will help achieve better outcomes for persons of color and because it is inherently worthwhile to oppose injustice.

However, contrary to some news reports, the VHA approach does not allocate by race/ethnicity alone, as it does by age.10,11 Doing so would present logistical challenges—for example, race/ethnicity is not an objective classification as is age, and reconciling individuals’ self-reports could create confusion or chaos that is antithetical to a fair, streamlined vaccination program. Putting veterans of color at the front of the vaccination line could backfire by amplifying worries that they are being exposed to vaccine that is not fully tested (a common contributor to vaccine hesitancy, particularly among communities of color familiar with prior exploitation and abuse in the name of science).

Discriminating based on race/ethnicity alone in the spirit of achieving equity would be precedent setting for the VA and would require a strong ethical justification. The decision to prioritize for vaccine based on risk factors strives to achieve this balance of equity and utility, as it encompasses VA staff and veterans of color by way of their status as essential workers or those with comorbidities. However, it is important to address race-based access barriers and vaccine hesitancy to satisfy the equity demands. This effort is underway (eg, engaging community champions and developing tailored educational resources to reach diverse communities).

In addition, pragmatic ethics recognizes that an overly granular, complicated allocation plan would be inefficient to implement. While it might be true that some veterans who are aged < 65 years may be at higher risk from COVID-19 than some elderly veterans, achieving the goals of fairness and transparency requires establishing a vaccine prioritization plan that is both ethically defensible and feasibly implementable (ie, achieves its goal of getting “needles into arms”). For example, veterans aged ≥ 65 years may be invited to schedule their vaccination before younger veterans, but any veteran may be accepted “on-call” for vaccine appointment no-shows via first-come, first-served or by lottery. Flexibility of response is crucial. This played out in adding flexibility around the decision to vaccinate veterans aged ≥ 75 years before those aged 65 to 74 years, after revisiting how this prioritization might affect feasibility and throughput and opting to allow the opportunity to include those aged ≥ 65 years.

There will no doubt be additional modifications to the vaccine allocation plan as more data become available. Since the danger of fueling suspicion and distrust is high (ie, that certain privileged people are jumping the line, as we heard reports of in some non-VA facilities).12 There is an obvious ethical duty to explain why the chosen approach is ethically defensible. VA facility leaders should be able to answer how their approach achieves the goals of avoiding serious or fatal illness, reducing contagion, and preserving the essential workforce while ensuring a fair, respectful, evidence-based, and transparent process.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. COVID-19 vaccination plan for the Veterans Health Administration. Version 2.0, Published December 14, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/n-coronavirus/VHA-COVID-Vaccine-Plan-14Dec2020.pdf

2. Hennigann WJ, Park A, Ducharme J. The U.S. fumbled its early vaccine rollout. Will the Biden Administration put America back on track? TIME. January 21, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://time.com/5932028/vaccine-rollout-joe-biden/

3. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA take key action in fight against COVID-19 by issuing emergency use authorization for first COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published December 11, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19

4. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes additional action in fight against COVID-19 by Issuing emergency use authorization for second COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-additional-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-second-covid

5. McClung N, Chamberland M, Kinlaw K, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Ethical Principles for Allocating Initial Supplies of COVID-19 Vaccine-United States, 2020. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(1):420-425. doi:10.1111/ajt.16437

6. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Framework for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccine. The National Academies Press; 2020. doi:10.17226/25917

7 . Wood S, Schulman K. Beyond Politics - Promoting Covid-19 vaccination in the United States [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jan 6]. N Engl J Med. 2021;10.1056/NEJMms2033790. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2033790

8 . Matrajt L, Eaton J, Leung T, Brown ER. Vaccine optimization for COVID-19, who to vaccinate first? medRxiv . 2020 Aug 16. doi:10.1101/2020.08.14.20175257

9 . Makary M. Hospitals: stop playing vaccine games and show leadership. Published January 12, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com/blogs/marty-makary/90649

10 . Wentling N. Minority veterans to receive priority for coronavirus vaccines. Stars and Stripes. December 10, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.stripes.com/news/us/minority-veterans-to-receive-priority-for-coronavirus-vaccines-1.654624

11 . Kime, P. Minority veterans on VA’s priority list for COVID-19 vaccine distribution. Published December 8, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2020/12/08/minority-veterans-vas-priority-list-covid-19-vaccine-distribution.html

12 . Rosenthal, E. Yes, it matters that people are jumping the vaccine line. The New York Times . Published January 28, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/28/opinion/covid-vaccine-line.html

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) COVID-19 vaccine allocation plan showcases several lessons for government and health care leaders in planning for future pandemics.1 Many state governments—underresourced and overwhelmed with other COVID-19 demands—have struggled to get COVID-19 vaccines into the arms of their residents.2 In contrast, the VHA was able to mobilize early to identify vaccine allocation guidelines and proactively prepare facilities to vaccinate VHA staff and veterans as soon as vaccines were approved under Emergency Use Authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In August 2020, VHA formed a COVID-19 Vaccine Integrated Project Team, composed of 6 subgroups: communications, distribution, education, measurement, policy, prioritization, and vaccine safety. The National Center for Ethics in Health Care weighed in on the ethical justification for the developed vaccination risk stratification framework, which was informed by, but not identical to, that recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.5

Prioritizing who gets early access to a potentially life-saving vaccine weighs heavily on those leaders charged with making such decisions. The ethics of scarce resource allocation and triage protocols that may be necessary in a pandemic are often in tension with the patient-centered clinical ethics that health care practitioners (HCPs) encounter. HCPs require assistance in appreciating the ethical rationale for this shift in focus from the preference of the individual to the common good. The same is true for the risk stratification criteria required when there is not sufficient vaccine for all those who could benefit from immunization. Decisions must be transparent to ensure widespread acceptance and trust in the vaccination process. The ethical reasoning and values that are the basis for allocation criteria must be clearly, compassionately, and consistently communicated to the public, as outlined below. Ethical questions or concerns involve a conflict between core values: one of the central tasks of ethical analysis is to identify the available ethical options to resolve value conflicts. Several ethical frameworks for vaccine allocation are available—each balances and weighs the primary values of equity, dignity, beneficence, and utility slightly differently.6

For example, utilitarian ethics looks to produce the most good and avoid the most harm for the greatest number of people. Within this framework, there can be different notions of “good,” for example, saving the most lives, the most life years, the most quality life years, or the lives of those who have more life “innings” ahead. The approach of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) focuses on saving the most lives in combination with avoiding suffering from serious illness, minimizing contagion, and preserving the essential workforce. Frameworks that give primacy to 1 notion of the good (ie, saving the most lives) may deprioritize other beneficial outcomes, such as allowing earlier return to work, school, and leisure activities that many find integral to human flourishing. Other ethical theories and principles may be used to support various allocation frameworks. For example, a pragmatic ethics approach might emphasize the importance of adapting the approach based on the evolving science and innovation surrounding COVID-19. Having more than 1 ethically defensible approach is common; the goal in ethics work is to be open to diversity of thought and reflect on the strength of one’s reasoning in resolving a core values conflict. We identify 2 central tenets of pandemic ethics that inform vaccine allocation.

1. Pandemic Ethics Requires Proactive Planning and Reevaluation of Continually Evolving Facts

There is an oft quoted saying among bioethicists: “Good ethics begins with good facts.” One obvious challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the difficulty accessing up-to-date facts to inform decision making. If a main goal of a vaccination plan is to minimize the incidence of serious or fatal COVID-19 disease and contagion, myriad data points are needed to identify the best way to do this. For example, if 2 doses of the same vaccine are needed, this impacts the logistics of identifying, inviting, and scheduling eligible individuals and staffing vaccine clinics as well as ensuring that sufficient personal protective equipment and rescue equipment/medication are available to treat allergic reactions. If the adverse effects of vaccines lead to staff absenteeism or vaccine hesitancy, this needs to be factored into logistics.7 Tailored messaging is important to reduce appointment no-shows and vaccine nonadopters.8 Transportation to vaccination sites is a relevant factor: how a vaccine is stored, thawed, and reconstituted and its shelf life impacts whether it can be transported after thawing and what must be provided on site.

Consideration of the multifaceted factors influencing a successful vaccination campaign requires proactive planning and the readiness to pivot when new information is revealed. For example, vaccine appointment no-shows should be anticipated along with a fair process for allocating unused vaccine that would otherwise be wasted. This is an example of responsible stewardship of a scarce and life-saving resource. A higher than anticipated no-show rate would require revisiting a facility’s approach to ensuring that waste is avoided while the process is perceived to be fair and transparent. Ethical theories and principles cannot do all the work here; mindful attention to detail and proactive, informed planning are critical. Fortunately, the VA is well resourced in this domain, whereas many state health departments floundered in their response, causing unnecessary vaccination delays.9

2. Utility: Necessary But Insufficient

Most ethical approaches recognize to some extent that seeking good and minimizing harm is of value. However, a strictly utilitarian approach is insufficient to address the core values in conflict surrounding how best to allocate limited doses of COVID-19 vaccine. For example, some may argue that prioritizing the elderly or those in long-term care facilities like VA’s community living centers because they have the highest COVID-19 mortality rate produces less net benefit than prioritizing younger veterans with comorbidities or certain higher risk essential workers. There are 2 important points to make here.

First, the VHA vaccination plan balances utility with other ethical principles, namely, treating people with equal concern, and addressing health inequities, including a focus on justice and valuing the worth and dignity of each person. Rather than giving everyone an equal chance via lottery, the prioritization plan recognizes that some people have greater need or would stand to better mitigate viral contagion and preserve the essential workforce if they were vaccinated earlier. However, the principle of justice requires that efforts are made to treat like cases the same to avoid perceptions of bias, and to demonstrate respect for the dignity of each individual by way of promoting a fair vaccination process.

This requires transparency, consistency, and delivery of respectful and accurate communication. For example, the VA recognizes that lifetime exposure to social injustice produces health inequities that make Black, Hispanic, and Native American persons more susceptible to contracting COVID-19 and suffering serious or fatal illness. The approach to addressing this inequity is by giving priority to those with higher risk factors. Again, this is an example of blending and balancing ethical principles of utility and justice—that is, recognizing and remedying social injustice is of value both because it will help achieve better outcomes for persons of color and because it is inherently worthwhile to oppose injustice.

However, contrary to some news reports, the VHA approach does not allocate by race/ethnicity alone, as it does by age.10,11 Doing so would present logistical challenges—for example, race/ethnicity is not an objective classification as is age, and reconciling individuals’ self-reports could create confusion or chaos that is antithetical to a fair, streamlined vaccination program. Putting veterans of color at the front of the vaccination line could backfire by amplifying worries that they are being exposed to vaccine that is not fully tested (a common contributor to vaccine hesitancy, particularly among communities of color familiar with prior exploitation and abuse in the name of science).

Discriminating based on race/ethnicity alone in the spirit of achieving equity would be precedent setting for the VA and would require a strong ethical justification. The decision to prioritize for vaccine based on risk factors strives to achieve this balance of equity and utility, as it encompasses VA staff and veterans of color by way of their status as essential workers or those with comorbidities. However, it is important to address race-based access barriers and vaccine hesitancy to satisfy the equity demands. This effort is underway (eg, engaging community champions and developing tailored educational resources to reach diverse communities).

In addition, pragmatic ethics recognizes that an overly granular, complicated allocation plan would be inefficient to implement. While it might be true that some veterans who are aged < 65 years may be at higher risk from COVID-19 than some elderly veterans, achieving the goals of fairness and transparency requires establishing a vaccine prioritization plan that is both ethically defensible and feasibly implementable (ie, achieves its goal of getting “needles into arms”). For example, veterans aged ≥ 65 years may be invited to schedule their vaccination before younger veterans, but any veteran may be accepted “on-call” for vaccine appointment no-shows via first-come, first-served or by lottery. Flexibility of response is crucial. This played out in adding flexibility around the decision to vaccinate veterans aged ≥ 75 years before those aged 65 to 74 years, after revisiting how this prioritization might affect feasibility and throughput and opting to allow the opportunity to include those aged ≥ 65 years.

There will no doubt be additional modifications to the vaccine allocation plan as more data become available. Since the danger of fueling suspicion and distrust is high (ie, that certain privileged people are jumping the line, as we heard reports of in some non-VA facilities).12 There is an obvious ethical duty to explain why the chosen approach is ethically defensible. VA facility leaders should be able to answer how their approach achieves the goals of avoiding serious or fatal illness, reducing contagion, and preserving the essential workforce while ensuring a fair, respectful, evidence-based, and transparent process.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) COVID-19 vaccine allocation plan showcases several lessons for government and health care leaders in planning for future pandemics.1 Many state governments—underresourced and overwhelmed with other COVID-19 demands—have struggled to get COVID-19 vaccines into the arms of their residents.2 In contrast, the VHA was able to mobilize early to identify vaccine allocation guidelines and proactively prepare facilities to vaccinate VHA staff and veterans as soon as vaccines were approved under Emergency Use Authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In August 2020, VHA formed a COVID-19 Vaccine Integrated Project Team, composed of 6 subgroups: communications, distribution, education, measurement, policy, prioritization, and vaccine safety. The National Center for Ethics in Health Care weighed in on the ethical justification for the developed vaccination risk stratification framework, which was informed by, but not identical to, that recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.5

Prioritizing who gets early access to a potentially life-saving vaccine weighs heavily on those leaders charged with making such decisions. The ethics of scarce resource allocation and triage protocols that may be necessary in a pandemic are often in tension with the patient-centered clinical ethics that health care practitioners (HCPs) encounter. HCPs require assistance in appreciating the ethical rationale for this shift in focus from the preference of the individual to the common good. The same is true for the risk stratification criteria required when there is not sufficient vaccine for all those who could benefit from immunization. Decisions must be transparent to ensure widespread acceptance and trust in the vaccination process. The ethical reasoning and values that are the basis for allocation criteria must be clearly, compassionately, and consistently communicated to the public, as outlined below. Ethical questions or concerns involve a conflict between core values: one of the central tasks of ethical analysis is to identify the available ethical options to resolve value conflicts. Several ethical frameworks for vaccine allocation are available—each balances and weighs the primary values of equity, dignity, beneficence, and utility slightly differently.6

For example, utilitarian ethics looks to produce the most good and avoid the most harm for the greatest number of people. Within this framework, there can be different notions of “good,” for example, saving the most lives, the most life years, the most quality life years, or the lives of those who have more life “innings” ahead. The approach of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) focuses on saving the most lives in combination with avoiding suffering from serious illness, minimizing contagion, and preserving the essential workforce. Frameworks that give primacy to 1 notion of the good (ie, saving the most lives) may deprioritize other beneficial outcomes, such as allowing earlier return to work, school, and leisure activities that many find integral to human flourishing. Other ethical theories and principles may be used to support various allocation frameworks. For example, a pragmatic ethics approach might emphasize the importance of adapting the approach based on the evolving science and innovation surrounding COVID-19. Having more than 1 ethically defensible approach is common; the goal in ethics work is to be open to diversity of thought and reflect on the strength of one’s reasoning in resolving a core values conflict. We identify 2 central tenets of pandemic ethics that inform vaccine allocation.

1. Pandemic Ethics Requires Proactive Planning and Reevaluation of Continually Evolving Facts

There is an oft quoted saying among bioethicists: “Good ethics begins with good facts.” One obvious challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the difficulty accessing up-to-date facts to inform decision making. If a main goal of a vaccination plan is to minimize the incidence of serious or fatal COVID-19 disease and contagion, myriad data points are needed to identify the best way to do this. For example, if 2 doses of the same vaccine are needed, this impacts the logistics of identifying, inviting, and scheduling eligible individuals and staffing vaccine clinics as well as ensuring that sufficient personal protective equipment and rescue equipment/medication are available to treat allergic reactions. If the adverse effects of vaccines lead to staff absenteeism or vaccine hesitancy, this needs to be factored into logistics.7 Tailored messaging is important to reduce appointment no-shows and vaccine nonadopters.8 Transportation to vaccination sites is a relevant factor: how a vaccine is stored, thawed, and reconstituted and its shelf life impacts whether it can be transported after thawing and what must be provided on site.

Consideration of the multifaceted factors influencing a successful vaccination campaign requires proactive planning and the readiness to pivot when new information is revealed. For example, vaccine appointment no-shows should be anticipated along with a fair process for allocating unused vaccine that would otherwise be wasted. This is an example of responsible stewardship of a scarce and life-saving resource. A higher than anticipated no-show rate would require revisiting a facility’s approach to ensuring that waste is avoided while the process is perceived to be fair and transparent. Ethical theories and principles cannot do all the work here; mindful attention to detail and proactive, informed planning are critical. Fortunately, the VA is well resourced in this domain, whereas many state health departments floundered in their response, causing unnecessary vaccination delays.9

2. Utility: Necessary But Insufficient

Most ethical approaches recognize to some extent that seeking good and minimizing harm is of value. However, a strictly utilitarian approach is insufficient to address the core values in conflict surrounding how best to allocate limited doses of COVID-19 vaccine. For example, some may argue that prioritizing the elderly or those in long-term care facilities like VA’s community living centers because they have the highest COVID-19 mortality rate produces less net benefit than prioritizing younger veterans with comorbidities or certain higher risk essential workers. There are 2 important points to make here.

First, the VHA vaccination plan balances utility with other ethical principles, namely, treating people with equal concern, and addressing health inequities, including a focus on justice and valuing the worth and dignity of each person. Rather than giving everyone an equal chance via lottery, the prioritization plan recognizes that some people have greater need or would stand to better mitigate viral contagion and preserve the essential workforce if they were vaccinated earlier. However, the principle of justice requires that efforts are made to treat like cases the same to avoid perceptions of bias, and to demonstrate respect for the dignity of each individual by way of promoting a fair vaccination process.

This requires transparency, consistency, and delivery of respectful and accurate communication. For example, the VA recognizes that lifetime exposure to social injustice produces health inequities that make Black, Hispanic, and Native American persons more susceptible to contracting COVID-19 and suffering serious or fatal illness. The approach to addressing this inequity is by giving priority to those with higher risk factors. Again, this is an example of blending and balancing ethical principles of utility and justice—that is, recognizing and remedying social injustice is of value both because it will help achieve better outcomes for persons of color and because it is inherently worthwhile to oppose injustice.

However, contrary to some news reports, the VHA approach does not allocate by race/ethnicity alone, as it does by age.10,11 Doing so would present logistical challenges—for example, race/ethnicity is not an objective classification as is age, and reconciling individuals’ self-reports could create confusion or chaos that is antithetical to a fair, streamlined vaccination program. Putting veterans of color at the front of the vaccination line could backfire by amplifying worries that they are being exposed to vaccine that is not fully tested (a common contributor to vaccine hesitancy, particularly among communities of color familiar with prior exploitation and abuse in the name of science).

Discriminating based on race/ethnicity alone in the spirit of achieving equity would be precedent setting for the VA and would require a strong ethical justification. The decision to prioritize for vaccine based on risk factors strives to achieve this balance of equity and utility, as it encompasses VA staff and veterans of color by way of their status as essential workers or those with comorbidities. However, it is important to address race-based access barriers and vaccine hesitancy to satisfy the equity demands. This effort is underway (eg, engaging community champions and developing tailored educational resources to reach diverse communities).

In addition, pragmatic ethics recognizes that an overly granular, complicated allocation plan would be inefficient to implement. While it might be true that some veterans who are aged < 65 years may be at higher risk from COVID-19 than some elderly veterans, achieving the goals of fairness and transparency requires establishing a vaccine prioritization plan that is both ethically defensible and feasibly implementable (ie, achieves its goal of getting “needles into arms”). For example, veterans aged ≥ 65 years may be invited to schedule their vaccination before younger veterans, but any veteran may be accepted “on-call” for vaccine appointment no-shows via first-come, first-served or by lottery. Flexibility of response is crucial. This played out in adding flexibility around the decision to vaccinate veterans aged ≥ 75 years before those aged 65 to 74 years, after revisiting how this prioritization might affect feasibility and throughput and opting to allow the opportunity to include those aged ≥ 65 years.

There will no doubt be additional modifications to the vaccine allocation plan as more data become available. Since the danger of fueling suspicion and distrust is high (ie, that certain privileged people are jumping the line, as we heard reports of in some non-VA facilities).12 There is an obvious ethical duty to explain why the chosen approach is ethically defensible. VA facility leaders should be able to answer how their approach achieves the goals of avoiding serious or fatal illness, reducing contagion, and preserving the essential workforce while ensuring a fair, respectful, evidence-based, and transparent process.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. COVID-19 vaccination plan for the Veterans Health Administration. Version 2.0, Published December 14, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/n-coronavirus/VHA-COVID-Vaccine-Plan-14Dec2020.pdf

2. Hennigann WJ, Park A, Ducharme J. The U.S. fumbled its early vaccine rollout. Will the Biden Administration put America back on track? TIME. January 21, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://time.com/5932028/vaccine-rollout-joe-biden/

3. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA take key action in fight against COVID-19 by issuing emergency use authorization for first COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published December 11, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19

4. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes additional action in fight against COVID-19 by Issuing emergency use authorization for second COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-additional-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-second-covid

5. McClung N, Chamberland M, Kinlaw K, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Ethical Principles for Allocating Initial Supplies of COVID-19 Vaccine-United States, 2020. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(1):420-425. doi:10.1111/ajt.16437

6. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Framework for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccine. The National Academies Press; 2020. doi:10.17226/25917

7 . Wood S, Schulman K. Beyond Politics - Promoting Covid-19 vaccination in the United States [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jan 6]. N Engl J Med. 2021;10.1056/NEJMms2033790. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2033790

8 . Matrajt L, Eaton J, Leung T, Brown ER. Vaccine optimization for COVID-19, who to vaccinate first? medRxiv . 2020 Aug 16. doi:10.1101/2020.08.14.20175257

9 . Makary M. Hospitals: stop playing vaccine games and show leadership. Published January 12, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com/blogs/marty-makary/90649

10 . Wentling N. Minority veterans to receive priority for coronavirus vaccines. Stars and Stripes. December 10, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.stripes.com/news/us/minority-veterans-to-receive-priority-for-coronavirus-vaccines-1.654624

11 . Kime, P. Minority veterans on VA’s priority list for COVID-19 vaccine distribution. Published December 8, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2020/12/08/minority-veterans-vas-priority-list-covid-19-vaccine-distribution.html

12 . Rosenthal, E. Yes, it matters that people are jumping the vaccine line. The New York Times . Published January 28, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/28/opinion/covid-vaccine-line.html

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. COVID-19 vaccination plan for the Veterans Health Administration. Version 2.0, Published December 14, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/n-coronavirus/VHA-COVID-Vaccine-Plan-14Dec2020.pdf

2. Hennigann WJ, Park A, Ducharme J. The U.S. fumbled its early vaccine rollout. Will the Biden Administration put America back on track? TIME. January 21, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://time.com/5932028/vaccine-rollout-joe-biden/

3. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA take key action in fight against COVID-19 by issuing emergency use authorization for first COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published December 11, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19

4. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes additional action in fight against COVID-19 by Issuing emergency use authorization for second COVID-19 vaccine [press release]. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-additional-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-second-covid

5. McClung N, Chamberland M, Kinlaw K, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Ethical Principles for Allocating Initial Supplies of COVID-19 Vaccine-United States, 2020. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(1):420-425. doi:10.1111/ajt.16437

6. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Framework for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccine. The National Academies Press; 2020. doi:10.17226/25917

7 . Wood S, Schulman K. Beyond Politics - Promoting Covid-19 vaccination in the United States [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jan 6]. N Engl J Med. 2021;10.1056/NEJMms2033790. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2033790

8 . Matrajt L, Eaton J, Leung T, Brown ER. Vaccine optimization for COVID-19, who to vaccinate first? medRxiv . 2020 Aug 16. doi:10.1101/2020.08.14.20175257

9 . Makary M. Hospitals: stop playing vaccine games and show leadership. Published January 12, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.medpagetoday.com/blogs/marty-makary/90649

10 . Wentling N. Minority veterans to receive priority for coronavirus vaccines. Stars and Stripes. December 10, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.stripes.com/news/us/minority-veterans-to-receive-priority-for-coronavirus-vaccines-1.654624

11 . Kime, P. Minority veterans on VA’s priority list for COVID-19 vaccine distribution. Published December 8, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2020/12/08/minority-veterans-vas-priority-list-covid-19-vaccine-distribution.html

12 . Rosenthal, E. Yes, it matters that people are jumping the vaccine line. The New York Times . Published January 28, 2021. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/28/opinion/covid-vaccine-line.html

Is it an Allergic Reaction to the COVID-19 Vaccine—or COVID-19?

As of January 10, 2021, a reported 4,041,396 first doses of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine had been administered in the US. Reports of 1,266 (0.03%) adverse effects (AEs) after receipt of the vaccine were submitted to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), according to researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 Response Team and Food and Drug Administration in a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report early release.

The researchers screened VAERS reports that described suspected severe allergic reactions and anaphylaxis and collected information from medical records and outreach to healthcare facilities, providers, and recipients. They identified 108 reports for further review as possible severe allergic reaction, including anaphylaxis, a rare vaccination reaction. Ten cases were determined to be anaphylaxis—or a rate of 2.5 cases per million vaccine doses administered. Nine of the cases were people with a documented history of allergies or allergic reactions; 5 had a history of anaphylaxis.

The median interval from vaccine receipt to symptom onset was 7.5 minutes. Eight people had follow-up information available; all had recovered or were discharged. Of the case reports that were determined not to be anaphylaxis, 47 were assessed as nonanaphylactic allergic reactions and 47 were considered nonallergic adverse events. Four cases lacked enough information to be determined.