User login

Too few Michigan children with SCD receive pneumococcal, meningococcal vaccines

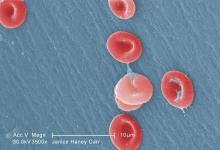

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

Key clinical point: Too few children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are receiving Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–recommended meningococcal and pneumococcal vaccines, including PCV13 and PPSV23.

Major finding:

Study details: The findings are based on a cohort study of children with and without SCD born in Michigan between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

Source: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

International travel updates

It’s that time of year again. Many of your patients will join the 80.2 million Americans with plans for international travel this summer.

In 2016, Mexico (31.2 million) and Canada (13.9 million) were the top two destinations of U.S. residents. Based on 2016 U.S. Commerce data, an additional 35.1 million Americans headed to overseas destinations, including 9% who traveled with children. Vacation and visiting friends and relatives accounted for 55% and 27% of the reasons for all travel, respectively. Education accounted for 4% of travelers.

Required versus recommended vaccines

The goal of a required vaccine is to prevent international spread of disease. The host country is protecting its citizens from visitors importing and facilitating the spread of a disease. Yellow fever and meningococcal disease are the only vaccines required for entry into any country. Entry requirements vary by country. Yellow fever may be an entry requirement for all travelers or it may be limited to those who have been in, or have had transit through, a country where yellow fever can be transmitted at least 6 days prior to the arrival at their final destination – a reminder that the sequence of the patient’s itinerary is important. In addition, just because a vaccine is not required for entry does not mean the risk for exposure and acquisition is nonexistent.

In contrast, recommended vaccines are for the protection of the individual. Travelers may be exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases that do not exist in their country (such as measles, typhoid fever, and yellow fever). They are at risk for acquisition and may return home infected, which could create the potential to spread the disease to susceptible contacts.

Most travelers comprehend required vaccines but often fail to understand the importance of receiving recommended vaccines. Lammert et al. reported that, of 24,478 persons who received pretravel advice between July 2012 and June 2014 through Global TravEpiNet, a national consortium of U.S. clinics, 97% were eligible for at least one vaccine. The majority were eligible for typhoid (n = 20,092) and hepatitis A (n = 12,990). Of patients included in the study, 25% (6,573) refused one or more vaccines. The most common reason cited for refusal was a lack of concern about the illness. Travelers visiting friends and relatives were less likely to accept all recommended vaccines, compared with those who were not visiting friends and relatives (odds ratio, 0.74) (J Trav Med. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taw075). In the United States, international travel remains the most common risk factor for acquisition of both typhoid fever and hepatitis A.

What’s new

The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends administering the hepatitis A vaccine to infants aged 6-11 months with travel to or living in developing countries and areas with high to moderate risk for hepatitis A virus transmission. Any dose received at less than 12 months of age does not count, and the administration of two age-appropriate doses should occur following this dose.

Old but still relevant

Measles: The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends all infants aged 6-11 months receive one dose of MMR prior to international travel regardless of the destination. This should be followed by two additional countable doses. All persons at least 12 months of age and born after 1956 should receive two doses of MMR at least 28 days apart prior to international travel.

Prior to administering, determine whether your patient will travel to a yellow fever–endemic area because both are live vaccines and should be received the same day. Otherwise, administer MMR doses 28 days apart; coordination between facilities or receipt of both at one facility may be necessary.

Yellow fever vaccine: The U.S. supplies of YF-Vax by Sanofi Pasteur are not expected to be available again until the end of 2018. To provide vaccines for U.S. travelers, Stamaril – a yellow fever vaccine produced by Sanofi Pasteur in France – has been made available at more than 250 sites through an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug Program.

Since Stamaril is offered at a limited number of locations, persons with anticipated travel to a country where receipt of yellow fever vaccine is either required for entry or recommended for their protection should not wait until the last minute to obtain it. Postponing a trip or changing a destination is preferred if vaccine is not received, especially when the person is traveling to countries with an ongoing outbreak.

The vaccination does not become valid until 10 days after receipt. Infants aged at least 9 months may receive the vaccine. Since the yellow fever vaccine is a live vaccine, administration may be contraindicated in certain individuals. Exemption letters are provided for those with medical contraindication.

To locate a Stamaril site in your area: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/search-for-stamaril-clinics.

Current disease outbreaks

Yellow fever: Brazil

Since Dec. 2017, more than 1,100 laboratory-confirmed cases of yellow fever have been reported, including 17 reported in unvaccinated international travelers. Fatal cases also have been reported. In addition to areas in Brazil where yellow fever vaccination had been recommended prior to the recent outbreaks, the vaccine now also is recommended for people who are traveling to or living in all of Espírito Santo State, São Paulo State, and Rio de Janeiro State, as well as several cities in Bahia State. Unvaccinated travelers should avoid travel to areas where vaccination is recommended. Those previously vaccinated at 10 years ago or longer should consider a booster.

Listeria: South Africa

An ongoing outbreak has been reported since Jan. 2017. Around 1,000 people have been infected. Avoid consumption of processed meats including “Polony” (South African bologna).

Measles: Belarus, Japan, Liberia, and Taiwan

All countries have reported an increase in cases since April 2018. Measles outbreaks have been reported in an additional 13 countries since Jan. 2018, including France, Ireland, Italy, the Philippines, and the United Kingdom.

Norovirus: Canada

More than 120 cases have been linked to consumption of raw or lightly cooked oysters from western Canada.

For more country-specific information and up to date travel alerts, visit http://www.cdc.gov/travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and the director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

It’s that time of year again. Many of your patients will join the 80.2 million Americans with plans for international travel this summer.

In 2016, Mexico (31.2 million) and Canada (13.9 million) were the top two destinations of U.S. residents. Based on 2016 U.S. Commerce data, an additional 35.1 million Americans headed to overseas destinations, including 9% who traveled with children. Vacation and visiting friends and relatives accounted for 55% and 27% of the reasons for all travel, respectively. Education accounted for 4% of travelers.

Required versus recommended vaccines

The goal of a required vaccine is to prevent international spread of disease. The host country is protecting its citizens from visitors importing and facilitating the spread of a disease. Yellow fever and meningococcal disease are the only vaccines required for entry into any country. Entry requirements vary by country. Yellow fever may be an entry requirement for all travelers or it may be limited to those who have been in, or have had transit through, a country where yellow fever can be transmitted at least 6 days prior to the arrival at their final destination – a reminder that the sequence of the patient’s itinerary is important. In addition, just because a vaccine is not required for entry does not mean the risk for exposure and acquisition is nonexistent.

In contrast, recommended vaccines are for the protection of the individual. Travelers may be exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases that do not exist in their country (such as measles, typhoid fever, and yellow fever). They are at risk for acquisition and may return home infected, which could create the potential to spread the disease to susceptible contacts.

Most travelers comprehend required vaccines but often fail to understand the importance of receiving recommended vaccines. Lammert et al. reported that, of 24,478 persons who received pretravel advice between July 2012 and June 2014 through Global TravEpiNet, a national consortium of U.S. clinics, 97% were eligible for at least one vaccine. The majority were eligible for typhoid (n = 20,092) and hepatitis A (n = 12,990). Of patients included in the study, 25% (6,573) refused one or more vaccines. The most common reason cited for refusal was a lack of concern about the illness. Travelers visiting friends and relatives were less likely to accept all recommended vaccines, compared with those who were not visiting friends and relatives (odds ratio, 0.74) (J Trav Med. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taw075). In the United States, international travel remains the most common risk factor for acquisition of both typhoid fever and hepatitis A.

What’s new

The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends administering the hepatitis A vaccine to infants aged 6-11 months with travel to or living in developing countries and areas with high to moderate risk for hepatitis A virus transmission. Any dose received at less than 12 months of age does not count, and the administration of two age-appropriate doses should occur following this dose.

Old but still relevant

Measles: The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends all infants aged 6-11 months receive one dose of MMR prior to international travel regardless of the destination. This should be followed by two additional countable doses. All persons at least 12 months of age and born after 1956 should receive two doses of MMR at least 28 days apart prior to international travel.

Prior to administering, determine whether your patient will travel to a yellow fever–endemic area because both are live vaccines and should be received the same day. Otherwise, administer MMR doses 28 days apart; coordination between facilities or receipt of both at one facility may be necessary.

Yellow fever vaccine: The U.S. supplies of YF-Vax by Sanofi Pasteur are not expected to be available again until the end of 2018. To provide vaccines for U.S. travelers, Stamaril – a yellow fever vaccine produced by Sanofi Pasteur in France – has been made available at more than 250 sites through an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug Program.

Since Stamaril is offered at a limited number of locations, persons with anticipated travel to a country where receipt of yellow fever vaccine is either required for entry or recommended for their protection should not wait until the last minute to obtain it. Postponing a trip or changing a destination is preferred if vaccine is not received, especially when the person is traveling to countries with an ongoing outbreak.

The vaccination does not become valid until 10 days after receipt. Infants aged at least 9 months may receive the vaccine. Since the yellow fever vaccine is a live vaccine, administration may be contraindicated in certain individuals. Exemption letters are provided for those with medical contraindication.

To locate a Stamaril site in your area: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/search-for-stamaril-clinics.

Current disease outbreaks

Yellow fever: Brazil

Since Dec. 2017, more than 1,100 laboratory-confirmed cases of yellow fever have been reported, including 17 reported in unvaccinated international travelers. Fatal cases also have been reported. In addition to areas in Brazil where yellow fever vaccination had been recommended prior to the recent outbreaks, the vaccine now also is recommended for people who are traveling to or living in all of Espírito Santo State, São Paulo State, and Rio de Janeiro State, as well as several cities in Bahia State. Unvaccinated travelers should avoid travel to areas where vaccination is recommended. Those previously vaccinated at 10 years ago or longer should consider a booster.

Listeria: South Africa

An ongoing outbreak has been reported since Jan. 2017. Around 1,000 people have been infected. Avoid consumption of processed meats including “Polony” (South African bologna).

Measles: Belarus, Japan, Liberia, and Taiwan

All countries have reported an increase in cases since April 2018. Measles outbreaks have been reported in an additional 13 countries since Jan. 2018, including France, Ireland, Italy, the Philippines, and the United Kingdom.

Norovirus: Canada

More than 120 cases have been linked to consumption of raw or lightly cooked oysters from western Canada.

For more country-specific information and up to date travel alerts, visit http://www.cdc.gov/travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and the director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

It’s that time of year again. Many of your patients will join the 80.2 million Americans with plans for international travel this summer.

In 2016, Mexico (31.2 million) and Canada (13.9 million) were the top two destinations of U.S. residents. Based on 2016 U.S. Commerce data, an additional 35.1 million Americans headed to overseas destinations, including 9% who traveled with children. Vacation and visiting friends and relatives accounted for 55% and 27% of the reasons for all travel, respectively. Education accounted for 4% of travelers.

Required versus recommended vaccines

The goal of a required vaccine is to prevent international spread of disease. The host country is protecting its citizens from visitors importing and facilitating the spread of a disease. Yellow fever and meningococcal disease are the only vaccines required for entry into any country. Entry requirements vary by country. Yellow fever may be an entry requirement for all travelers or it may be limited to those who have been in, or have had transit through, a country where yellow fever can be transmitted at least 6 days prior to the arrival at their final destination – a reminder that the sequence of the patient’s itinerary is important. In addition, just because a vaccine is not required for entry does not mean the risk for exposure and acquisition is nonexistent.

In contrast, recommended vaccines are for the protection of the individual. Travelers may be exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases that do not exist in their country (such as measles, typhoid fever, and yellow fever). They are at risk for acquisition and may return home infected, which could create the potential to spread the disease to susceptible contacts.

Most travelers comprehend required vaccines but often fail to understand the importance of receiving recommended vaccines. Lammert et al. reported that, of 24,478 persons who received pretravel advice between July 2012 and June 2014 through Global TravEpiNet, a national consortium of U.S. clinics, 97% were eligible for at least one vaccine. The majority were eligible for typhoid (n = 20,092) and hepatitis A (n = 12,990). Of patients included in the study, 25% (6,573) refused one or more vaccines. The most common reason cited for refusal was a lack of concern about the illness. Travelers visiting friends and relatives were less likely to accept all recommended vaccines, compared with those who were not visiting friends and relatives (odds ratio, 0.74) (J Trav Med. 2017 Jan. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taw075). In the United States, international travel remains the most common risk factor for acquisition of both typhoid fever and hepatitis A.

What’s new

The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends administering the hepatitis A vaccine to infants aged 6-11 months with travel to or living in developing countries and areas with high to moderate risk for hepatitis A virus transmission. Any dose received at less than 12 months of age does not count, and the administration of two age-appropriate doses should occur following this dose.

Old but still relevant

Measles: The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends all infants aged 6-11 months receive one dose of MMR prior to international travel regardless of the destination. This should be followed by two additional countable doses. All persons at least 12 months of age and born after 1956 should receive two doses of MMR at least 28 days apart prior to international travel.

Prior to administering, determine whether your patient will travel to a yellow fever–endemic area because both are live vaccines and should be received the same day. Otherwise, administer MMR doses 28 days apart; coordination between facilities or receipt of both at one facility may be necessary.

Yellow fever vaccine: The U.S. supplies of YF-Vax by Sanofi Pasteur are not expected to be available again until the end of 2018. To provide vaccines for U.S. travelers, Stamaril – a yellow fever vaccine produced by Sanofi Pasteur in France – has been made available at more than 250 sites through an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug Program.

Since Stamaril is offered at a limited number of locations, persons with anticipated travel to a country where receipt of yellow fever vaccine is either required for entry or recommended for their protection should not wait until the last minute to obtain it. Postponing a trip or changing a destination is preferred if vaccine is not received, especially when the person is traveling to countries with an ongoing outbreak.

The vaccination does not become valid until 10 days after receipt. Infants aged at least 9 months may receive the vaccine. Since the yellow fever vaccine is a live vaccine, administration may be contraindicated in certain individuals. Exemption letters are provided for those with medical contraindication.

To locate a Stamaril site in your area: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/search-for-stamaril-clinics.

Current disease outbreaks

Yellow fever: Brazil

Since Dec. 2017, more than 1,100 laboratory-confirmed cases of yellow fever have been reported, including 17 reported in unvaccinated international travelers. Fatal cases also have been reported. In addition to areas in Brazil where yellow fever vaccination had been recommended prior to the recent outbreaks, the vaccine now also is recommended for people who are traveling to or living in all of Espírito Santo State, São Paulo State, and Rio de Janeiro State, as well as several cities in Bahia State. Unvaccinated travelers should avoid travel to areas where vaccination is recommended. Those previously vaccinated at 10 years ago or longer should consider a booster.

Listeria: South Africa

An ongoing outbreak has been reported since Jan. 2017. Around 1,000 people have been infected. Avoid consumption of processed meats including “Polony” (South African bologna).

Measles: Belarus, Japan, Liberia, and Taiwan

All countries have reported an increase in cases since April 2018. Measles outbreaks have been reported in an additional 13 countries since Jan. 2018, including France, Ireland, Italy, the Philippines, and the United Kingdom.

Norovirus: Canada

More than 120 cases have been linked to consumption of raw or lightly cooked oysters from western Canada.

For more country-specific information and up to date travel alerts, visit http://www.cdc.gov/travel.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and the director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

MenB vaccine receives breakthrough therapy designation for children aged 1-9 years

according to an April 23, 2018, press statement from the vaccine’s manufacturer.

Trumenba is the first Neisseria meningitidis group B (MenB) vaccine to receive this designation for children as young as 1 year in the United States. In 2014, it became the first MenB vaccine to receive approval in the United States for older patients – aged 10-25 years. “As of 2016, the burden of MenB is highest in adolescents/young adults (32%) and infants (20%), followed by children ages 1 to 4 years (12%) and children ages 5 to 10 years (4%),” according to the statement.

The 2014 approval letter required the vaccine’s manufacturer, Pfizer, to assess the efficacy and safety of Trumenba among children aged 1-9 years. Data from the resulting phase 2 studies supported Pfizer’s request for a breakthrough therapy designation for use of the MenB vaccine in that age group.

For more information, read Pfizer’s full press statement.

according to an April 23, 2018, press statement from the vaccine’s manufacturer.

Trumenba is the first Neisseria meningitidis group B (MenB) vaccine to receive this designation for children as young as 1 year in the United States. In 2014, it became the first MenB vaccine to receive approval in the United States for older patients – aged 10-25 years. “As of 2016, the burden of MenB is highest in adolescents/young adults (32%) and infants (20%), followed by children ages 1 to 4 years (12%) and children ages 5 to 10 years (4%),” according to the statement.

The 2014 approval letter required the vaccine’s manufacturer, Pfizer, to assess the efficacy and safety of Trumenba among children aged 1-9 years. Data from the resulting phase 2 studies supported Pfizer’s request for a breakthrough therapy designation for use of the MenB vaccine in that age group.

For more information, read Pfizer’s full press statement.

according to an April 23, 2018, press statement from the vaccine’s manufacturer.

Trumenba is the first Neisseria meningitidis group B (MenB) vaccine to receive this designation for children as young as 1 year in the United States. In 2014, it became the first MenB vaccine to receive approval in the United States for older patients – aged 10-25 years. “As of 2016, the burden of MenB is highest in adolescents/young adults (32%) and infants (20%), followed by children ages 1 to 4 years (12%) and children ages 5 to 10 years (4%),” according to the statement.

The 2014 approval letter required the vaccine’s manufacturer, Pfizer, to assess the efficacy and safety of Trumenba among children aged 1-9 years. Data from the resulting phase 2 studies supported Pfizer’s request for a breakthrough therapy designation for use of the MenB vaccine in that age group.

For more information, read Pfizer’s full press statement.

Measles exacts high toll among Europe’s youngest citizens

MADRID – Children younger than 2 years who contracted measles were significantly more likely to die of the disease than were older children, according to new data from the European Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Infants younger than 12 months faced the worst mortality outcomes, with a sevenfold increased risk of death, compared with children aged 2 years or older, Emmanuel Robesyn, MD said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. Infants and children younger than 2 years also were much more likely to develop severe complications of the disease, including pneumonia and encephalitis.

The statistics should drive home the point that measles can be a life-threatening disease, especially for small children, said Dr. Robesyn, an expert in outbreak response at the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm.

“We want the population to understand that measles is much more than a nuisance illness of childhood,” he said. “Already this year we have recorded 13 deaths from measles,” which were not included in the data he presented.

“As you know, measles has been set for elimination” as a communicable disease, he said. “We need high immune coverage to achieve that, meaning 95% of the population covered with two doses. That is a challenge.”

Infants are especially vulnerable, and they fully reliant on the immunity of others to avoid measles.

“Vaccination recommendations begin at age 1, so before that, infants are dependent on their mothers’ antibodies, and on herd immunity. It’s very important that we have high vaccine coverage to protect them.”

Dr. Robesyn described measles outcomes in children 24 months and younger in 30 member states of the European Union and the European Economic Area from 2013 to 2017. Data were extracted from the European Surveillance System, which collects and analyzes infectious disease data across Europe.

During that period, there were 37,365 measles cases in people of all ages. Most were in Italy, Romania, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, with each reporting more than 5% of the cases. These countries also had the most cases that had not been connected with importation of the disease.

Overall, the patients were a mean of 12 years old. Less than 2% had been fully vaccinated against the disease. Complications (diarrhea, otitis media, pneumonia, or encephalitis) occurred in 13.6%, and about 33% of patients had to be hospitalized. Most cases (81%) occurred in people aged 2 years and older, 9% occurred in children who were 12-24 months old, and 10% occurred in children younger than 12 months. These younger children, however, accounted for 61% of the deaths in the cohort, Dr. Robesyn said.

Most of the cases occurred in unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated patients. Forty-six died from measles, a mortality rate of about 1 per 1,000 who contracted the disease. Of these deaths, 16 were among children younger than 12 months, 12 among children aged 12-24 months, and the remainder among those older than 2 years.

These younger patients were also more susceptible to complications of measles, both mild (diarrhea and otitis media) and severe (pneumonia and encephalitis). Most of the uncomplicated cases (75%) occurred in children older than 24 months, with just 25% of uncomplicated cases occurring in the younger groups.

“When we looked at age as a continuous variable, we saw that the chance of having no complications or just mild complications increased with age, and the chance of having severe complications decreased with age,” Dr. Robesyn said.

“We definitely saw that these two groups are at increased risk. The consequences however, are different. For the children who are 1 year of age or older, the message is that it’s really important to strictly follow national recommendations and get timely and complete vaccination. For those younger than 1 year, we have to rely on the population to be vaccinated. It is very important that we reach this 95% coverage rate to protect these youngest children. We need adolescents and young adults who have missed vaccinations to get them completed,” he said.

Dr. Robesyn had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Robesyn E et al. ECCMID 2018, abstract O0060

MADRID – Children younger than 2 years who contracted measles were significantly more likely to die of the disease than were older children, according to new data from the European Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Infants younger than 12 months faced the worst mortality outcomes, with a sevenfold increased risk of death, compared with children aged 2 years or older, Emmanuel Robesyn, MD said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. Infants and children younger than 2 years also were much more likely to develop severe complications of the disease, including pneumonia and encephalitis.

The statistics should drive home the point that measles can be a life-threatening disease, especially for small children, said Dr. Robesyn, an expert in outbreak response at the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm.

“We want the population to understand that measles is much more than a nuisance illness of childhood,” he said. “Already this year we have recorded 13 deaths from measles,” which were not included in the data he presented.

“As you know, measles has been set for elimination” as a communicable disease, he said. “We need high immune coverage to achieve that, meaning 95% of the population covered with two doses. That is a challenge.”

Infants are especially vulnerable, and they fully reliant on the immunity of others to avoid measles.

“Vaccination recommendations begin at age 1, so before that, infants are dependent on their mothers’ antibodies, and on herd immunity. It’s very important that we have high vaccine coverage to protect them.”

Dr. Robesyn described measles outcomes in children 24 months and younger in 30 member states of the European Union and the European Economic Area from 2013 to 2017. Data were extracted from the European Surveillance System, which collects and analyzes infectious disease data across Europe.

During that period, there were 37,365 measles cases in people of all ages. Most were in Italy, Romania, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, with each reporting more than 5% of the cases. These countries also had the most cases that had not been connected with importation of the disease.

Overall, the patients were a mean of 12 years old. Less than 2% had been fully vaccinated against the disease. Complications (diarrhea, otitis media, pneumonia, or encephalitis) occurred in 13.6%, and about 33% of patients had to be hospitalized. Most cases (81%) occurred in people aged 2 years and older, 9% occurred in children who were 12-24 months old, and 10% occurred in children younger than 12 months. These younger children, however, accounted for 61% of the deaths in the cohort, Dr. Robesyn said.

Most of the cases occurred in unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated patients. Forty-six died from measles, a mortality rate of about 1 per 1,000 who contracted the disease. Of these deaths, 16 were among children younger than 12 months, 12 among children aged 12-24 months, and the remainder among those older than 2 years.

These younger patients were also more susceptible to complications of measles, both mild (diarrhea and otitis media) and severe (pneumonia and encephalitis). Most of the uncomplicated cases (75%) occurred in children older than 24 months, with just 25% of uncomplicated cases occurring in the younger groups.

“When we looked at age as a continuous variable, we saw that the chance of having no complications or just mild complications increased with age, and the chance of having severe complications decreased with age,” Dr. Robesyn said.

“We definitely saw that these two groups are at increased risk. The consequences however, are different. For the children who are 1 year of age or older, the message is that it’s really important to strictly follow national recommendations and get timely and complete vaccination. For those younger than 1 year, we have to rely on the population to be vaccinated. It is very important that we reach this 95% coverage rate to protect these youngest children. We need adolescents and young adults who have missed vaccinations to get them completed,” he said.

Dr. Robesyn had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Robesyn E et al. ECCMID 2018, abstract O0060

MADRID – Children younger than 2 years who contracted measles were significantly more likely to die of the disease than were older children, according to new data from the European Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Infants younger than 12 months faced the worst mortality outcomes, with a sevenfold increased risk of death, compared with children aged 2 years or older, Emmanuel Robesyn, MD said at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress. Infants and children younger than 2 years also were much more likely to develop severe complications of the disease, including pneumonia and encephalitis.

The statistics should drive home the point that measles can be a life-threatening disease, especially for small children, said Dr. Robesyn, an expert in outbreak response at the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm.

“We want the population to understand that measles is much more than a nuisance illness of childhood,” he said. “Already this year we have recorded 13 deaths from measles,” which were not included in the data he presented.

“As you know, measles has been set for elimination” as a communicable disease, he said. “We need high immune coverage to achieve that, meaning 95% of the population covered with two doses. That is a challenge.”

Infants are especially vulnerable, and they fully reliant on the immunity of others to avoid measles.

“Vaccination recommendations begin at age 1, so before that, infants are dependent on their mothers’ antibodies, and on herd immunity. It’s very important that we have high vaccine coverage to protect them.”

Dr. Robesyn described measles outcomes in children 24 months and younger in 30 member states of the European Union and the European Economic Area from 2013 to 2017. Data were extracted from the European Surveillance System, which collects and analyzes infectious disease data across Europe.

During that period, there were 37,365 measles cases in people of all ages. Most were in Italy, Romania, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, with each reporting more than 5% of the cases. These countries also had the most cases that had not been connected with importation of the disease.

Overall, the patients were a mean of 12 years old. Less than 2% had been fully vaccinated against the disease. Complications (diarrhea, otitis media, pneumonia, or encephalitis) occurred in 13.6%, and about 33% of patients had to be hospitalized. Most cases (81%) occurred in people aged 2 years and older, 9% occurred in children who were 12-24 months old, and 10% occurred in children younger than 12 months. These younger children, however, accounted for 61% of the deaths in the cohort, Dr. Robesyn said.

Most of the cases occurred in unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated patients. Forty-six died from measles, a mortality rate of about 1 per 1,000 who contracted the disease. Of these deaths, 16 were among children younger than 12 months, 12 among children aged 12-24 months, and the remainder among those older than 2 years.

These younger patients were also more susceptible to complications of measles, both mild (diarrhea and otitis media) and severe (pneumonia and encephalitis). Most of the uncomplicated cases (75%) occurred in children older than 24 months, with just 25% of uncomplicated cases occurring in the younger groups.

“When we looked at age as a continuous variable, we saw that the chance of having no complications or just mild complications increased with age, and the chance of having severe complications decreased with age,” Dr. Robesyn said.

“We definitely saw that these two groups are at increased risk. The consequences however, are different. For the children who are 1 year of age or older, the message is that it’s really important to strictly follow national recommendations and get timely and complete vaccination. For those younger than 1 year, we have to rely on the population to be vaccinated. It is very important that we reach this 95% coverage rate to protect these youngest children. We need adolescents and young adults who have missed vaccinations to get them completed,” he said.

Dr. Robesyn had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Robesyn E et al. ECCMID 2018, abstract O0060

REPORTING FROM ECCMID 2018

Key clinical point: Measles is most dangerous to children younger than 2 years.

Major finding: Children younger than 12 months who contracted measles were seven times more likely to die of the disease than were children 2 years and older.

Study details: The analysis involved 37,365 measles cases that occurred in the European Union from 2013 to 2017.

Disclosures: The analysis was conducted by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control.

Source: Robesyn E et al. ECCMID 2018, abstract O0060.

No increased intussusception risk from rotavirus vaccine in Africa

Neither the first nor second dose of the monovalent rotavirus vaccine increased the risk of intussusception in the 3 weeks after immunization, a recent study found.

“This finding contrasts with previous studies in high- and upper-middle-income countries, in which an association with intussusception was found,” Jacqueline E. Tate, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Given these large health benefits, the absence of increased risk of intussusception after RV1 [monovalent Rotarix vaccine] administration in our study is reassuring,” the authors wrote.

An African Intussusception Surveillance Network at 29 hospitals in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe enrolled 1,060 infants younger than age 12 months who experienced intussusception during Feb. 2012-Dec. 2016.

The researchers excluded infants without confirmed record of rotavirus vaccination status or who developed intussusception symptoms when younger than 28 days or older than 245 days. A little more than a third of the remaining 717 infants (36%) were from Ghana, more than half (61%) were male, and their median age was 25 weeks. Only 2% of the children had never received breast milk before developing intussusception symptoms.

The researchers used vaccine cards and clinic records to determine the rotavirus vaccination status for those 717 children with intussusception. The majority of the children (84%) had received both doses of the monovalent rotavirus vaccine. A total of 6% had received only one dose, and 10% received none. Five children received at least one rotavirus vaccine dose after having had intussusception already.

One intussusception case occurred within the first 7 days after the first vaccine dose, and five cases occurred within a week of the second dose. These incidences were no higher than was the background rate of intussusception, so no increased risk of intussusception in the week after either dose was identified, the researchers said.

The relative incidence of intussusception for dose one during days 1-7 was 0.25 (95% confidence interval, less than .001-1.16), and the relative incidence of intussusception for dose two during days 1-7 was 0.76 (95% CI, 0.16-1.87), Dr. Tate and her associates said.

Incidence of intussusception during the period 8-21 days after vaccination included 6 cases after the first dose and 16 cases after the second dose. Intussusception risk in this extended postvaccination period also was no higher than background risk.

“No clustering of cases occurred in any of the risk windows (1-7 days, 8-21 days, or 1-21 days) after receipt of either dose of RV1,” the authors reported.

They offered several possible reasons why no increased intussusception risk with rotavirus vaccination occurred in these countries despite studies in middle- and high-income countries showing an increased risk.

“First, although the exact mechanism is not known, intussusception may be related to intestinal replication of the orally administered, live-vaccine rotavirus strain,” Dr. Tate and her colleagues wrote. “Because oral rotavirus vaccines are less efficacious and shedding of vaccine virus – a potential marker of vaccine replication – is less frequently detected in low-income countries than in high- and middle-income countries, rotavirus vaccination might also be associated with a lower intussusception risk in low-income countries.”

Coadministration of rotavirus vaccination with the first dose of oral polio vaccine, which can reduce the rotavirus vaccine’s immunogenicity, also may play a role. Further, the children in this study were vaccinated against rotavirus at age 6- and 10-weeks-old – earlier than the 8 and 16 weeks in middle- and high-income countries – and intussusception is less common under 2 months old, potentially reducing likelihood of an association. Diet, breastfeeding practices, microbiome, maternal antibody levels, or other factors also may be at play.

The research was funded by the Gavi Alliance through the CDC Foundation. Dr. Cunliffe and Dr. Lopman have received personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Takeda Pharmaceutical, respectively. The other authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Tate JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1521-8.

Neither the first nor second dose of the monovalent rotavirus vaccine increased the risk of intussusception in the 3 weeks after immunization, a recent study found.

“This finding contrasts with previous studies in high- and upper-middle-income countries, in which an association with intussusception was found,” Jacqueline E. Tate, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Given these large health benefits, the absence of increased risk of intussusception after RV1 [monovalent Rotarix vaccine] administration in our study is reassuring,” the authors wrote.

An African Intussusception Surveillance Network at 29 hospitals in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe enrolled 1,060 infants younger than age 12 months who experienced intussusception during Feb. 2012-Dec. 2016.

The researchers excluded infants without confirmed record of rotavirus vaccination status or who developed intussusception symptoms when younger than 28 days or older than 245 days. A little more than a third of the remaining 717 infants (36%) were from Ghana, more than half (61%) were male, and their median age was 25 weeks. Only 2% of the children had never received breast milk before developing intussusception symptoms.

The researchers used vaccine cards and clinic records to determine the rotavirus vaccination status for those 717 children with intussusception. The majority of the children (84%) had received both doses of the monovalent rotavirus vaccine. A total of 6% had received only one dose, and 10% received none. Five children received at least one rotavirus vaccine dose after having had intussusception already.

One intussusception case occurred within the first 7 days after the first vaccine dose, and five cases occurred within a week of the second dose. These incidences were no higher than was the background rate of intussusception, so no increased risk of intussusception in the week after either dose was identified, the researchers said.

The relative incidence of intussusception for dose one during days 1-7 was 0.25 (95% confidence interval, less than .001-1.16), and the relative incidence of intussusception for dose two during days 1-7 was 0.76 (95% CI, 0.16-1.87), Dr. Tate and her associates said.

Incidence of intussusception during the period 8-21 days after vaccination included 6 cases after the first dose and 16 cases after the second dose. Intussusception risk in this extended postvaccination period also was no higher than background risk.

“No clustering of cases occurred in any of the risk windows (1-7 days, 8-21 days, or 1-21 days) after receipt of either dose of RV1,” the authors reported.

They offered several possible reasons why no increased intussusception risk with rotavirus vaccination occurred in these countries despite studies in middle- and high-income countries showing an increased risk.

“First, although the exact mechanism is not known, intussusception may be related to intestinal replication of the orally administered, live-vaccine rotavirus strain,” Dr. Tate and her colleagues wrote. “Because oral rotavirus vaccines are less efficacious and shedding of vaccine virus – a potential marker of vaccine replication – is less frequently detected in low-income countries than in high- and middle-income countries, rotavirus vaccination might also be associated with a lower intussusception risk in low-income countries.”

Coadministration of rotavirus vaccination with the first dose of oral polio vaccine, which can reduce the rotavirus vaccine’s immunogenicity, also may play a role. Further, the children in this study were vaccinated against rotavirus at age 6- and 10-weeks-old – earlier than the 8 and 16 weeks in middle- and high-income countries – and intussusception is less common under 2 months old, potentially reducing likelihood of an association. Diet, breastfeeding practices, microbiome, maternal antibody levels, or other factors also may be at play.

The research was funded by the Gavi Alliance through the CDC Foundation. Dr. Cunliffe and Dr. Lopman have received personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Takeda Pharmaceutical, respectively. The other authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Tate JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1521-8.

Neither the first nor second dose of the monovalent rotavirus vaccine increased the risk of intussusception in the 3 weeks after immunization, a recent study found.

“This finding contrasts with previous studies in high- and upper-middle-income countries, in which an association with intussusception was found,” Jacqueline E. Tate, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Given these large health benefits, the absence of increased risk of intussusception after RV1 [monovalent Rotarix vaccine] administration in our study is reassuring,” the authors wrote.

An African Intussusception Surveillance Network at 29 hospitals in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe enrolled 1,060 infants younger than age 12 months who experienced intussusception during Feb. 2012-Dec. 2016.

The researchers excluded infants without confirmed record of rotavirus vaccination status or who developed intussusception symptoms when younger than 28 days or older than 245 days. A little more than a third of the remaining 717 infants (36%) were from Ghana, more than half (61%) were male, and their median age was 25 weeks. Only 2% of the children had never received breast milk before developing intussusception symptoms.

The researchers used vaccine cards and clinic records to determine the rotavirus vaccination status for those 717 children with intussusception. The majority of the children (84%) had received both doses of the monovalent rotavirus vaccine. A total of 6% had received only one dose, and 10% received none. Five children received at least one rotavirus vaccine dose after having had intussusception already.

One intussusception case occurred within the first 7 days after the first vaccine dose, and five cases occurred within a week of the second dose. These incidences were no higher than was the background rate of intussusception, so no increased risk of intussusception in the week after either dose was identified, the researchers said.

The relative incidence of intussusception for dose one during days 1-7 was 0.25 (95% confidence interval, less than .001-1.16), and the relative incidence of intussusception for dose two during days 1-7 was 0.76 (95% CI, 0.16-1.87), Dr. Tate and her associates said.

Incidence of intussusception during the period 8-21 days after vaccination included 6 cases after the first dose and 16 cases after the second dose. Intussusception risk in this extended postvaccination period also was no higher than background risk.

“No clustering of cases occurred in any of the risk windows (1-7 days, 8-21 days, or 1-21 days) after receipt of either dose of RV1,” the authors reported.

They offered several possible reasons why no increased intussusception risk with rotavirus vaccination occurred in these countries despite studies in middle- and high-income countries showing an increased risk.

“First, although the exact mechanism is not known, intussusception may be related to intestinal replication of the orally administered, live-vaccine rotavirus strain,” Dr. Tate and her colleagues wrote. “Because oral rotavirus vaccines are less efficacious and shedding of vaccine virus – a potential marker of vaccine replication – is less frequently detected in low-income countries than in high- and middle-income countries, rotavirus vaccination might also be associated with a lower intussusception risk in low-income countries.”

Coadministration of rotavirus vaccination with the first dose of oral polio vaccine, which can reduce the rotavirus vaccine’s immunogenicity, also may play a role. Further, the children in this study were vaccinated against rotavirus at age 6- and 10-weeks-old – earlier than the 8 and 16 weeks in middle- and high-income countries – and intussusception is less common under 2 months old, potentially reducing likelihood of an association. Diet, breastfeeding practices, microbiome, maternal antibody levels, or other factors also may be at play.

The research was funded by the Gavi Alliance through the CDC Foundation. Dr. Cunliffe and Dr. Lopman have received personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Takeda Pharmaceutical, respectively. The other authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Tate JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1521-8.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The relative incidence of intussusception for dose one during days 1-7 was 0.25 (95% confidence interval, less than .001-1.16), and the relative incidence of intussusception for dose two during days 1-7 was 0.76 (95% CI, 0.16-1.87).

Data source: The findings are based on a self-controlled case-series study involving 717 infants with intussusception and confirmed status of rotavirus vaccination, from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Gavi Alliance through the CDC Foundation. Dr. Cunliffe and Dr. Lopman have received personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Takeda Pharmaceutical, respectively. The other authors had no disclosures.

Source: Tate JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1521-8.

Herpes zoster boosts short-term stroke, TIA risk

ORLANDO – The risk of stroke and TIA – but not of acute MI – is significantly increased during the period surrounding diagnosis of herpes zoster, compared with the rate in matched zoster-free controls, according to a retrospective study of nearly 70,000 U.S. adults. A particularly striking study finding was the marked age disparity in the magnitude of vascular event risk associated with herpes zoster (HZ), with younger adults being at higher risk.

This increased vascular event risk associated with HZ was transitory. During the entire study follow-up period, which stretched from 1 month prior to HZ diagnosis to 12 months afterward, there was no overall increased vascular event risk associated with HZ, noted Dr. Rausch, an infectious diseases specialist who serves as director of clinical and medical affairs for the U.S. zoster program at GlaxoSmithKline in Philadelphia.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of U.S. Medicare and commercial health insurance claims data linked with EHRs for 2007-2014. The study included 23,339 adults diagnosed with HZ and 46,378 controls matched for sociodemographic and cardiovascular risk factors.

During the period from 1 month before to 1 month after HZ diagnosis, the rate of the composite vascular endpoint was 31.4 events per 1,000 person-years in the HZ group versus 24.5 per 1,000 person-years in controls. This difference was driven by a significantly higher rate of stroke/TIA in the HZ group. In contrast, the acute MI rates in the two groups were quite similar, at 6.9 per 1,000 person-years in the HZ group and 7.1 per 1,000 person-years in controls.

Further research is needed in order to shed light on the higher rate of vascular events observed in the younger patients with HZ. One possible explanation for the age-related difference is that HZ’s vascular effects is diluted in older patients, who have a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Rausch noted.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of the two-dose recombinant Shingrix zoster vaccine in adults aged 50 years and older instead of the older, live-virus Zostavax vaccine, which is for adults aged 60 years and older.

Dr. Rausch’s study was sponsored by her employer, GlaxoSmithKline. The findings are supportive of an earlier study by other investigators, who found that the risk of hospitalization for stroke was up to twofold greater within the first 90 days after diagnosis of HZ in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases than the stroke rate 366-730 days after HZ (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017.69[2]:439-46).

SOURCE: Rausch DA. ACC 18

ORLANDO – The risk of stroke and TIA – but not of acute MI – is significantly increased during the period surrounding diagnosis of herpes zoster, compared with the rate in matched zoster-free controls, according to a retrospective study of nearly 70,000 U.S. adults. A particularly striking study finding was the marked age disparity in the magnitude of vascular event risk associated with herpes zoster (HZ), with younger adults being at higher risk.

This increased vascular event risk associated with HZ was transitory. During the entire study follow-up period, which stretched from 1 month prior to HZ diagnosis to 12 months afterward, there was no overall increased vascular event risk associated with HZ, noted Dr. Rausch, an infectious diseases specialist who serves as director of clinical and medical affairs for the U.S. zoster program at GlaxoSmithKline in Philadelphia.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of U.S. Medicare and commercial health insurance claims data linked with EHRs for 2007-2014. The study included 23,339 adults diagnosed with HZ and 46,378 controls matched for sociodemographic and cardiovascular risk factors.

During the period from 1 month before to 1 month after HZ diagnosis, the rate of the composite vascular endpoint was 31.4 events per 1,000 person-years in the HZ group versus 24.5 per 1,000 person-years in controls. This difference was driven by a significantly higher rate of stroke/TIA in the HZ group. In contrast, the acute MI rates in the two groups were quite similar, at 6.9 per 1,000 person-years in the HZ group and 7.1 per 1,000 person-years in controls.

Further research is needed in order to shed light on the higher rate of vascular events observed in the younger patients with HZ. One possible explanation for the age-related difference is that HZ’s vascular effects is diluted in older patients, who have a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Rausch noted.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of the two-dose recombinant Shingrix zoster vaccine in adults aged 50 years and older instead of the older, live-virus Zostavax vaccine, which is for adults aged 60 years and older.

Dr. Rausch’s study was sponsored by her employer, GlaxoSmithKline. The findings are supportive of an earlier study by other investigators, who found that the risk of hospitalization for stroke was up to twofold greater within the first 90 days after diagnosis of HZ in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases than the stroke rate 366-730 days after HZ (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017.69[2]:439-46).

SOURCE: Rausch DA. ACC 18

ORLANDO – The risk of stroke and TIA – but not of acute MI – is significantly increased during the period surrounding diagnosis of herpes zoster, compared with the rate in matched zoster-free controls, according to a retrospective study of nearly 70,000 U.S. adults. A particularly striking study finding was the marked age disparity in the magnitude of vascular event risk associated with herpes zoster (HZ), with younger adults being at higher risk.

This increased vascular event risk associated with HZ was transitory. During the entire study follow-up period, which stretched from 1 month prior to HZ diagnosis to 12 months afterward, there was no overall increased vascular event risk associated with HZ, noted Dr. Rausch, an infectious diseases specialist who serves as director of clinical and medical affairs for the U.S. zoster program at GlaxoSmithKline in Philadelphia.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of U.S. Medicare and commercial health insurance claims data linked with EHRs for 2007-2014. The study included 23,339 adults diagnosed with HZ and 46,378 controls matched for sociodemographic and cardiovascular risk factors.

During the period from 1 month before to 1 month after HZ diagnosis, the rate of the composite vascular endpoint was 31.4 events per 1,000 person-years in the HZ group versus 24.5 per 1,000 person-years in controls. This difference was driven by a significantly higher rate of stroke/TIA in the HZ group. In contrast, the acute MI rates in the two groups were quite similar, at 6.9 per 1,000 person-years in the HZ group and 7.1 per 1,000 person-years in controls.

Further research is needed in order to shed light on the higher rate of vascular events observed in the younger patients with HZ. One possible explanation for the age-related difference is that HZ’s vascular effects is diluted in older patients, who have a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors, Dr. Rausch noted.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of the two-dose recombinant Shingrix zoster vaccine in adults aged 50 years and older instead of the older, live-virus Zostavax vaccine, which is for adults aged 60 years and older.

Dr. Rausch’s study was sponsored by her employer, GlaxoSmithKline. The findings are supportive of an earlier study by other investigators, who found that the risk of hospitalization for stroke was up to twofold greater within the first 90 days after diagnosis of HZ in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases than the stroke rate 366-730 days after HZ (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017.69[2]:439-46).

SOURCE: Rausch DA. ACC 18

REPORTING FROM ACC 2018

Key clinical point: Herpes zoster is associated with significantly increased short-term risk of stroke/TIA.

Major finding: Adults aged 18-49 years were threefold more likely than controls to experience stroke or TIA within a month of herpes zoster diagnosis.

Study details: This retrospective study included 23,339 U.S. adults with herpes zoster and twice as many matched controls.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline and presented by a GSK employee.

Source: Rausch DA. ACC 18

Waning vaccine immunity linked to pertussis resurgence

researchers said.

In the March 28, 2018, edition of Science Translational Medicine, researchers reported on a study that used different models of transmission to explore what might be the cause of the steady increase in pertussis infections since the mid-1970s.

Using 16 years’ worth of detailed, age-stratified incidence data from Massachusetts, researchers found that the model which assumed a gradual waning in protection was the best fit for the observed patterns of pertussis incidence across the population.

This model suggested significant variability in how the level of protection changes over time, with a 10% risk of vaccine protection waning to zero within 10 years of completing routine vaccination and a 55% chance that the vaccine would confer lifelong protection.

“Crucially, we find that the vaccine is effective at reducing pathogen circulation but not so effective that eradication of this highly contagious bacterium should be possible without targeted booster campaigns,” wrote Dr. Matthieu Domenech de Cellès, PhD, of the Institut Pasteur at the University of Versailles (France) and his coauthors.

The model also considered the possibility that the whole-cell and acellular pertussis vaccines might show differences in immunity, which had been suggested as one explanation for the resurgence of the disease. However, the authors found little evidence of a marked epidemiological switch from the whole-cell to acellular vaccines, although their results did suggest the acellular vaccine has a moderately reduced efficacy.

“Our results suggest that the train of events leading to the resurgence of pertussis was set in motion well before the shift to the DTaP vaccine,” Dr. Domenech de Cellès and his associates said.

The model also pointed to big shifts in the age-specific immunological profile caused by introduction of vaccination, which led to a reduction in transmission and also a reduction in natural infections both in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

This meant individuals who either did not get vaccinated as children or who did not gain immunity from vaccination were growing to adulthood without ever being exposed to natural infection.

“Concurrently, older cohorts, with their long-lived immunity derived from natural infections experienced during the prevaccine period, were gradually dying out,” the authors said. “The resulting rise in the number of susceptible adults sets the stage for the pertussis resurgence, especially among adults.”

Two authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health and by Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study–National Institute of General Medical Sciences. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Domenech de Cellès M et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Mar 28;10:eaaj1748.

researchers said.

In the March 28, 2018, edition of Science Translational Medicine, researchers reported on a study that used different models of transmission to explore what might be the cause of the steady increase in pertussis infections since the mid-1970s.

Using 16 years’ worth of detailed, age-stratified incidence data from Massachusetts, researchers found that the model which assumed a gradual waning in protection was the best fit for the observed patterns of pertussis incidence across the population.

This model suggested significant variability in how the level of protection changes over time, with a 10% risk of vaccine protection waning to zero within 10 years of completing routine vaccination and a 55% chance that the vaccine would confer lifelong protection.

“Crucially, we find that the vaccine is effective at reducing pathogen circulation but not so effective that eradication of this highly contagious bacterium should be possible without targeted booster campaigns,” wrote Dr. Matthieu Domenech de Cellès, PhD, of the Institut Pasteur at the University of Versailles (France) and his coauthors.

The model also considered the possibility that the whole-cell and acellular pertussis vaccines might show differences in immunity, which had been suggested as one explanation for the resurgence of the disease. However, the authors found little evidence of a marked epidemiological switch from the whole-cell to acellular vaccines, although their results did suggest the acellular vaccine has a moderately reduced efficacy.

“Our results suggest that the train of events leading to the resurgence of pertussis was set in motion well before the shift to the DTaP vaccine,” Dr. Domenech de Cellès and his associates said.

The model also pointed to big shifts in the age-specific immunological profile caused by introduction of vaccination, which led to a reduction in transmission and also a reduction in natural infections both in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

This meant individuals who either did not get vaccinated as children or who did not gain immunity from vaccination were growing to adulthood without ever being exposed to natural infection.