User login

DMARDs may hamper pneumococcal vaccine response in systemic sclerosis patients

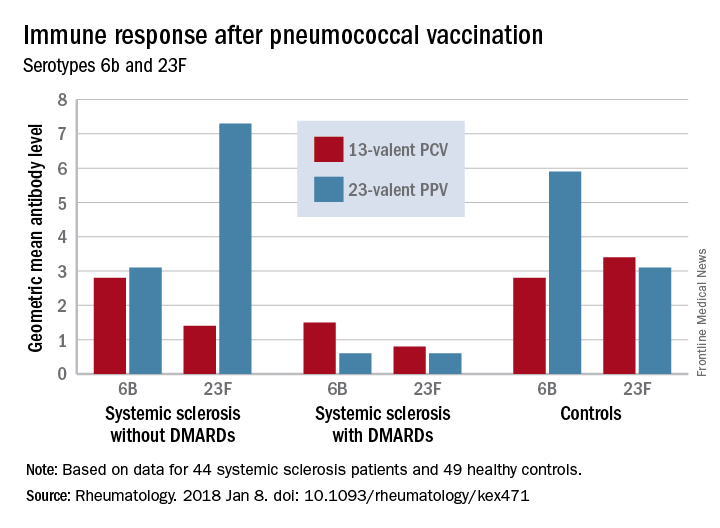

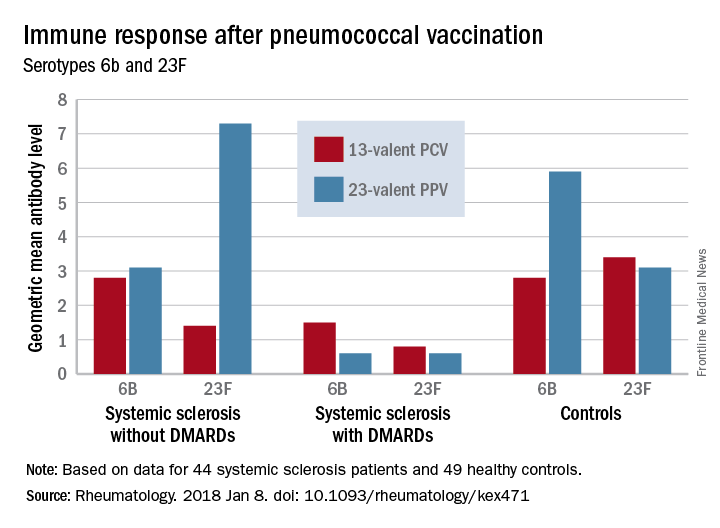

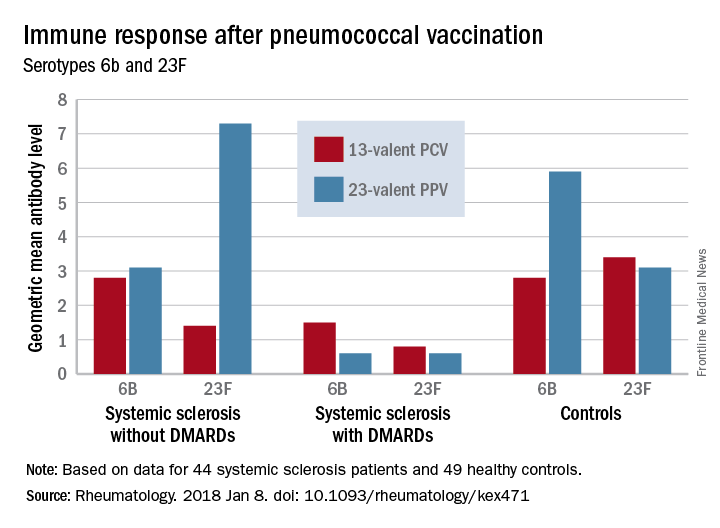

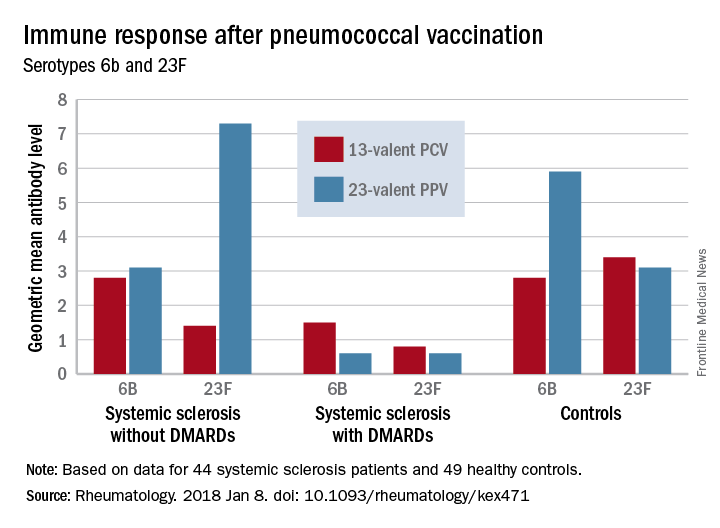

Patients taking disease-modifying antirheumatic medications for systemic sclerosis appear to have a decreased response to pneumococcal vaccines, a Swedish study has determined.

Those not taking disease-modifying antirheumatic medications (DMARDs), however, had a normal immune response, suggesting that it’s the immunomodulating medications, not the disease itself, that is affecting antibody levels, Roger Hesselstrand, MD, of Lund (Sweden) University and his colleagues reported online in Rheumatology.

“The currently recommended prime-boost vaccination strategy using a dose of PCV13 [13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine] followed by a dose of PPV23 [23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine] might be a possible way of enhancing the vaccine immunogenicity in immunosuppressed patients,” Dr. Hesselstrand and his coauthors wrote.

The study comprised 44 subjects with systemic sclerosis, 12 of whom were taking a DMARD (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, or hydroxychloroquine), and 49 healthy controls; all underwent pneumococcal vaccination. The first 13 got a single dose of PPV23 intramuscularly. PCV13 was then licensed for adults in Sweden, and the remaining 31 patients received this vaccine. The primary outcome was 6-week change from baseline in the level of pneumococcal IgG to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 23F and 6B.

Both vaccines were safe and well-tolerated by all patients, including those taking a DMARD.

Before vaccination, antibody levels to both serotypes were similar between the groups. After vaccination, antibody levels for both serotypes increased significantly in systemic sclerosis patients not taking a DMARD and in controls. However, patients taking a DMARD mounted only an adequate response to serotype 6B.

There were fewer responders among those taking DMARDs, whether they received the PCV13 or the PPV23 vaccine. An increase from prevaccination antibody levels of at least twofold occurred in fewer patients taking DMARDs than did in patients not taking DMARDs and in controls, regardless of vaccine type (PPV23, 50% vs. about 55% and 50%, respectively; PCV13, about 17% vs. 57% and 100%, respectively).

“We demonstrated that the antibody response ... as well as functionality of antibodies in [systemic sclerosis] patients not receiving DMARDs was as good as in controls regardless of vaccine type,” the investigators concluded. “Systemic sclerosis patients treated with DMARDs, however, had lower proportion of patients with positive antibody response, although the functionality of the antibodies was preserved. These results suggest that immunomodulating drugs but not systemic sclerosis itself and/or immunological disturbance as a part of this disease affect the ability to produce a sufficient amount of vaccine-specific antibodies, but not their function.”

None of the authors had conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Hesselstrand R et al. Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex471.

Patients taking disease-modifying antirheumatic medications for systemic sclerosis appear to have a decreased response to pneumococcal vaccines, a Swedish study has determined.

Those not taking disease-modifying antirheumatic medications (DMARDs), however, had a normal immune response, suggesting that it’s the immunomodulating medications, not the disease itself, that is affecting antibody levels, Roger Hesselstrand, MD, of Lund (Sweden) University and his colleagues reported online in Rheumatology.

“The currently recommended prime-boost vaccination strategy using a dose of PCV13 [13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine] followed by a dose of PPV23 [23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine] might be a possible way of enhancing the vaccine immunogenicity in immunosuppressed patients,” Dr. Hesselstrand and his coauthors wrote.

The study comprised 44 subjects with systemic sclerosis, 12 of whom were taking a DMARD (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, or hydroxychloroquine), and 49 healthy controls; all underwent pneumococcal vaccination. The first 13 got a single dose of PPV23 intramuscularly. PCV13 was then licensed for adults in Sweden, and the remaining 31 patients received this vaccine. The primary outcome was 6-week change from baseline in the level of pneumococcal IgG to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 23F and 6B.

Both vaccines were safe and well-tolerated by all patients, including those taking a DMARD.

Before vaccination, antibody levels to both serotypes were similar between the groups. After vaccination, antibody levels for both serotypes increased significantly in systemic sclerosis patients not taking a DMARD and in controls. However, patients taking a DMARD mounted only an adequate response to serotype 6B.

There were fewer responders among those taking DMARDs, whether they received the PCV13 or the PPV23 vaccine. An increase from prevaccination antibody levels of at least twofold occurred in fewer patients taking DMARDs than did in patients not taking DMARDs and in controls, regardless of vaccine type (PPV23, 50% vs. about 55% and 50%, respectively; PCV13, about 17% vs. 57% and 100%, respectively).

“We demonstrated that the antibody response ... as well as functionality of antibodies in [systemic sclerosis] patients not receiving DMARDs was as good as in controls regardless of vaccine type,” the investigators concluded. “Systemic sclerosis patients treated with DMARDs, however, had lower proportion of patients with positive antibody response, although the functionality of the antibodies was preserved. These results suggest that immunomodulating drugs but not systemic sclerosis itself and/or immunological disturbance as a part of this disease affect the ability to produce a sufficient amount of vaccine-specific antibodies, but not their function.”

None of the authors had conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Hesselstrand R et al. Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex471.

Patients taking disease-modifying antirheumatic medications for systemic sclerosis appear to have a decreased response to pneumococcal vaccines, a Swedish study has determined.

Those not taking disease-modifying antirheumatic medications (DMARDs), however, had a normal immune response, suggesting that it’s the immunomodulating medications, not the disease itself, that is affecting antibody levels, Roger Hesselstrand, MD, of Lund (Sweden) University and his colleagues reported online in Rheumatology.

“The currently recommended prime-boost vaccination strategy using a dose of PCV13 [13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine] followed by a dose of PPV23 [23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine] might be a possible way of enhancing the vaccine immunogenicity in immunosuppressed patients,” Dr. Hesselstrand and his coauthors wrote.

The study comprised 44 subjects with systemic sclerosis, 12 of whom were taking a DMARD (mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, or hydroxychloroquine), and 49 healthy controls; all underwent pneumococcal vaccination. The first 13 got a single dose of PPV23 intramuscularly. PCV13 was then licensed for adults in Sweden, and the remaining 31 patients received this vaccine. The primary outcome was 6-week change from baseline in the level of pneumococcal IgG to Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 23F and 6B.

Both vaccines were safe and well-tolerated by all patients, including those taking a DMARD.

Before vaccination, antibody levels to both serotypes were similar between the groups. After vaccination, antibody levels for both serotypes increased significantly in systemic sclerosis patients not taking a DMARD and in controls. However, patients taking a DMARD mounted only an adequate response to serotype 6B.

There were fewer responders among those taking DMARDs, whether they received the PCV13 or the PPV23 vaccine. An increase from prevaccination antibody levels of at least twofold occurred in fewer patients taking DMARDs than did in patients not taking DMARDs and in controls, regardless of vaccine type (PPV23, 50% vs. about 55% and 50%, respectively; PCV13, about 17% vs. 57% and 100%, respectively).

“We demonstrated that the antibody response ... as well as functionality of antibodies in [systemic sclerosis] patients not receiving DMARDs was as good as in controls regardless of vaccine type,” the investigators concluded. “Systemic sclerosis patients treated with DMARDs, however, had lower proportion of patients with positive antibody response, although the functionality of the antibodies was preserved. These results suggest that immunomodulating drugs but not systemic sclerosis itself and/or immunological disturbance as a part of this disease affect the ability to produce a sufficient amount of vaccine-specific antibodies, but not their function.”

None of the authors had conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Hesselstrand R et al. Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex471.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: An increase in prevaccination antibody levels of at least twofold occurred in significantly fewer patients taking DMARDs than in patients not taking DMARDs and controls, regardless of vaccine type (PPV23, 50% vs. about 55% and 50%, respectively; PCV13, about 17% vs. 57% and 100%, respectively).

Study details: The prospective study comprised 44 systemic sclerosis patients and 49 healthy controls.

Disclosures: None of the authors had conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source: Hesselstrand R et al. Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2018 Jan 8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex471

Clinical Trial Begins for Long-Acting Anti-HIV Injectable

A clinical trial to test a new, potentially more convenient HIV prophylaxis for women is starting in Africa. It is a long-acting form of the investigational drug cabotegravir and could give sexually active women a choice of biomedical HIV prevention tools for the first time, similar to the choices available for contraception, says Sinead Delany-Moretiwe, PhD, chair of the protocol.

The trial, HPTN 084, will enroll about 3,200 women aged 18 to 45 years at 20 sites in 7 countries. The women will be randomly assigned to either cabotegravir and a placebo pill or Truvada, which is a combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Truvada, currently the only drug licensed for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, must be taken every day to achieve and maintain protective drug concentrations. The women will start with 2 cabotegravir injections 4 weeks apart, then receive injections once every 8 weeks for an average of 2.6 years. After completing the injections, participants will be offered 48 weeks of PrEP with daily oral Truvada.

The NIAID is sponsoring the phase 3 clinical trial and cofunding it in a unique partnership with ViiV Healthcare (which is providing the study medications with Gilead Sciences) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Participants will receive HIV prevention counseling, condoms and lubricant, and counseling to support adherence to the daily pill. Anyone who becomes HIV infected during the trial will stop receiving the study products and be referred to local medical providers for care and treatment.

The study also will evaluate how women experience long-acting injectable cabotegravir, the researchers say. They are hoping to get a better understanding of the types of safe and effective HIV prevention that also fit best in women’s lives.

A clinical trial to test a new, potentially more convenient HIV prophylaxis for women is starting in Africa. It is a long-acting form of the investigational drug cabotegravir and could give sexually active women a choice of biomedical HIV prevention tools for the first time, similar to the choices available for contraception, says Sinead Delany-Moretiwe, PhD, chair of the protocol.

The trial, HPTN 084, will enroll about 3,200 women aged 18 to 45 years at 20 sites in 7 countries. The women will be randomly assigned to either cabotegravir and a placebo pill or Truvada, which is a combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Truvada, currently the only drug licensed for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, must be taken every day to achieve and maintain protective drug concentrations. The women will start with 2 cabotegravir injections 4 weeks apart, then receive injections once every 8 weeks for an average of 2.6 years. After completing the injections, participants will be offered 48 weeks of PrEP with daily oral Truvada.

The NIAID is sponsoring the phase 3 clinical trial and cofunding it in a unique partnership with ViiV Healthcare (which is providing the study medications with Gilead Sciences) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Participants will receive HIV prevention counseling, condoms and lubricant, and counseling to support adherence to the daily pill. Anyone who becomes HIV infected during the trial will stop receiving the study products and be referred to local medical providers for care and treatment.

The study also will evaluate how women experience long-acting injectable cabotegravir, the researchers say. They are hoping to get a better understanding of the types of safe and effective HIV prevention that also fit best in women’s lives.

A clinical trial to test a new, potentially more convenient HIV prophylaxis for women is starting in Africa. It is a long-acting form of the investigational drug cabotegravir and could give sexually active women a choice of biomedical HIV prevention tools for the first time, similar to the choices available for contraception, says Sinead Delany-Moretiwe, PhD, chair of the protocol.

The trial, HPTN 084, will enroll about 3,200 women aged 18 to 45 years at 20 sites in 7 countries. The women will be randomly assigned to either cabotegravir and a placebo pill or Truvada, which is a combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Truvada, currently the only drug licensed for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, must be taken every day to achieve and maintain protective drug concentrations. The women will start with 2 cabotegravir injections 4 weeks apart, then receive injections once every 8 weeks for an average of 2.6 years. After completing the injections, participants will be offered 48 weeks of PrEP with daily oral Truvada.

The NIAID is sponsoring the phase 3 clinical trial and cofunding it in a unique partnership with ViiV Healthcare (which is providing the study medications with Gilead Sciences) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Participants will receive HIV prevention counseling, condoms and lubricant, and counseling to support adherence to the daily pill. Anyone who becomes HIV infected during the trial will stop receiving the study products and be referred to local medical providers for care and treatment.

The study also will evaluate how women experience long-acting injectable cabotegravir, the researchers say. They are hoping to get a better understanding of the types of safe and effective HIV prevention that also fit best in women’s lives.

Dental Health: What It Means in Kidney Disease

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

Q) I teach nephrology at a local PA program, and they want us to integrate dental care into each module. What’s the connection between the two?

Dental health is frequently overlooked in the medical realm, as many clinicians feel that dental issues are out of our purview. Hematuria worries us, but bleeding gums and other signs of periodontal disease are often ignored. Surprisingly, many patients don’t seem to mind when their gums bleed every time they brush; they believe that this is normal, when really, it’s not.

Growing evidence supports associations between dental health and multiple medical issues—chronic kidney disease (CKD) among them. Periodontal disease is one of several inflammatory diseases caused by an interaction between gram-negative periodontal bacterial species and the immune system. It manifests with sore, red, bleeding gums and can lead to tooth loss if left untreated.

Chronic inflammation in the gums is a good indicator of inflammation elsewhere in the body. In and of itself, periodontitis can set off an inflammatory cascade in the body. Poor dentition can also lead to poor nutrition, which then causes a feedback loop, leading to even more inflammation.

Patients with periodontal disease have higher levels of C-reactive protein and a higher erythrocyte sedimentation rate than those without the disease.1 And a recent study by Zhang et al showed that periodontal disease increased risk for all-cause mortality in patients with CKD.2

The high cost of CKD from both a financial and personal view makes any intervention worth exploring, as the risk factors are difficult to modify and the CKD population is growing worldwide. We, as medical providers, should reiterate what our dental colleagues have been saying for years: Encourage patients with CKD to practice good dental hygiene by brushing twice a day and flossing daily, in an attempt to improve their overall outcomes.

LCDR Julie Taylor, PA-C

United States Public Health Service, Boston

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

1. Zhang J, Jiang H, Sun M, Chen J. Association between periodontal disease and mortality in people with CKD: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):269.

2. Chen YT, Shin CJ, Ou SM, et al; Taiwan Geriatric Kidney Disease (TGKD) Research Group. Periodontal disease and risks of kidney function decline and mortality in older people: a community-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015; 66(2):223-230.

Novel herpes zoster vaccine is more cost effective than old vaccine

The novel herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) is more effective and less expensive than the currently used live attenuated virus (ZVL), according to a study from the Center for Value-Based Research.

Phuc Le, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic and her colleague Michael Rothberg, MD, conducted an economic analysis of vaccine strategies from the societal perspective. This included the direct medical costs and productivity losses associated with HZ disease and complications.

The one-, two-, and three-way sensitivity analyses examined how different variables affected the cost-effectiveness of different vaccine strategies. The one-way analysis examined the association of input variables and cost-effectiveness. This included HZ/su prices, waning rate and initial efficacy of a dose of HZ/su, and the adherence rate. This analysis revealed that, compared with no vaccination, HZ/su would provide cost savings up to a price of $160, or $80 per dose.

Regardless of circumstance, HZ/su was always more effective than ZVL according to the two-way sensitivity analysis. This analysis took into account the joint effect of price, adherence to two doses of HZ/su, efficacy, and the waning rate of one dose and two doses of HZ/su and ZVL. Compared with ZVL, HZ/su would be less costly up to a price of $350 per series.

Adherence rates to vaccination schedules were important in determining the efficacy and waning rate which ultimately effected cost-effectiveness. The three-way sensitivity analysis found that, if HZ/su adherence to the second dose was greater than 56.8%, results were insensitive to the variation of single-dose efficacy and waning rate of HZ/su. But if adherence rates fell below 40%, combinations of waning rate and lower efficacy made HZ/su cost ineffective. Most importantly, ZVL was never cost effective for 60-year-old patients.

Despite a projected price of $280 per series, HZ/su is still more effective and less expensive than ZVL for adults 60 years or older. According to Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg, the assumptions about the vaccine’s efficacy duration and price were reasonable. But, if the vaccine price were to rise in the future, or a single dose becomes much less effective than reported by GlaxoSmithKline, or if adherence to the second dose was remarkably low, the results of the study would be changed.

“An ACIP recommendation stating a preference for HZ/su over ZVL could lead to future price increases, which would render the vaccine no longer cost effective” wrote Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg. “Therefore, a recommendation linked to periodic reassessment of cost-effectiveness based on the vaccine price might help to mitigate the effect of the recommendation on vaccine affordability.”

Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg reported having no conflicts of interest.

The HZ/su vaccine is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but in 2017, the FDA Advisory Committee unanimously voted in favor of its use in adults age 50 years and older.

SOURCE: Phuc L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7431. Najafzadeh M. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7442.

The herpes zoster (HZ) virus disproportionately affects elderly populations. As the U.S. population ages, tools and mechanisms to reduce the clinical and economic burden of HZ will be needed in the coming years.

The work of Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg presents the results of an economic evaluation on randomized clinical trials of a yet-to-be-approved novel HZ subunit vaccine (HZ/su) to determine the economic and clinical benefit of the new vaccine, compared with the currently used vaccine. Although HZ/su is intended to be a two-dose vaccine, the study focused on a one-time vaccine strategy because booster vaccines are unpopular and not recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“If priced at $280 per two required doses, HZ/su appears to be a cost-saving option, compared with ZVL and a cost-effective option, compared with no-vaccine strategies,” wrote Dr. Najafzadeh. “However, the value of HZ/su vaccine would be even higher if it could be marketed at a price comparable to that of ZVL.” An added benefit of the HZ/su vaccine is that it can be used in immunocompromised patients.

Mehdi Najafzadeh, PhD , is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He also serves as an associate statistician/epidemiologist in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The herpes zoster (HZ) virus disproportionately affects elderly populations. As the U.S. population ages, tools and mechanisms to reduce the clinical and economic burden of HZ will be needed in the coming years.

The work of Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg presents the results of an economic evaluation on randomized clinical trials of a yet-to-be-approved novel HZ subunit vaccine (HZ/su) to determine the economic and clinical benefit of the new vaccine, compared with the currently used vaccine. Although HZ/su is intended to be a two-dose vaccine, the study focused on a one-time vaccine strategy because booster vaccines are unpopular and not recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“If priced at $280 per two required doses, HZ/su appears to be a cost-saving option, compared with ZVL and a cost-effective option, compared with no-vaccine strategies,” wrote Dr. Najafzadeh. “However, the value of HZ/su vaccine would be even higher if it could be marketed at a price comparable to that of ZVL.” An added benefit of the HZ/su vaccine is that it can be used in immunocompromised patients.

Mehdi Najafzadeh, PhD , is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He also serves as an associate statistician/epidemiologist in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The herpes zoster (HZ) virus disproportionately affects elderly populations. As the U.S. population ages, tools and mechanisms to reduce the clinical and economic burden of HZ will be needed in the coming years.

The work of Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg presents the results of an economic evaluation on randomized clinical trials of a yet-to-be-approved novel HZ subunit vaccine (HZ/su) to determine the economic and clinical benefit of the new vaccine, compared with the currently used vaccine. Although HZ/su is intended to be a two-dose vaccine, the study focused on a one-time vaccine strategy because booster vaccines are unpopular and not recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“If priced at $280 per two required doses, HZ/su appears to be a cost-saving option, compared with ZVL and a cost-effective option, compared with no-vaccine strategies,” wrote Dr. Najafzadeh. “However, the value of HZ/su vaccine would be even higher if it could be marketed at a price comparable to that of ZVL.” An added benefit of the HZ/su vaccine is that it can be used in immunocompromised patients.

Mehdi Najafzadeh, PhD , is an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. He also serves as an associate statistician/epidemiologist in the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The novel herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) is more effective and less expensive than the currently used live attenuated virus (ZVL), according to a study from the Center for Value-Based Research.

Phuc Le, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic and her colleague Michael Rothberg, MD, conducted an economic analysis of vaccine strategies from the societal perspective. This included the direct medical costs and productivity losses associated with HZ disease and complications.

The one-, two-, and three-way sensitivity analyses examined how different variables affected the cost-effectiveness of different vaccine strategies. The one-way analysis examined the association of input variables and cost-effectiveness. This included HZ/su prices, waning rate and initial efficacy of a dose of HZ/su, and the adherence rate. This analysis revealed that, compared with no vaccination, HZ/su would provide cost savings up to a price of $160, or $80 per dose.

Regardless of circumstance, HZ/su was always more effective than ZVL according to the two-way sensitivity analysis. This analysis took into account the joint effect of price, adherence to two doses of HZ/su, efficacy, and the waning rate of one dose and two doses of HZ/su and ZVL. Compared with ZVL, HZ/su would be less costly up to a price of $350 per series.

Adherence rates to vaccination schedules were important in determining the efficacy and waning rate which ultimately effected cost-effectiveness. The three-way sensitivity analysis found that, if HZ/su adherence to the second dose was greater than 56.8%, results were insensitive to the variation of single-dose efficacy and waning rate of HZ/su. But if adherence rates fell below 40%, combinations of waning rate and lower efficacy made HZ/su cost ineffective. Most importantly, ZVL was never cost effective for 60-year-old patients.

Despite a projected price of $280 per series, HZ/su is still more effective and less expensive than ZVL for adults 60 years or older. According to Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg, the assumptions about the vaccine’s efficacy duration and price were reasonable. But, if the vaccine price were to rise in the future, or a single dose becomes much less effective than reported by GlaxoSmithKline, or if adherence to the second dose was remarkably low, the results of the study would be changed.

“An ACIP recommendation stating a preference for HZ/su over ZVL could lead to future price increases, which would render the vaccine no longer cost effective” wrote Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg. “Therefore, a recommendation linked to periodic reassessment of cost-effectiveness based on the vaccine price might help to mitigate the effect of the recommendation on vaccine affordability.”

Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg reported having no conflicts of interest.

The HZ/su vaccine is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but in 2017, the FDA Advisory Committee unanimously voted in favor of its use in adults age 50 years and older.

SOURCE: Phuc L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7431. Najafzadeh M. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7442.

The novel herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) is more effective and less expensive than the currently used live attenuated virus (ZVL), according to a study from the Center for Value-Based Research.

Phuc Le, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic and her colleague Michael Rothberg, MD, conducted an economic analysis of vaccine strategies from the societal perspective. This included the direct medical costs and productivity losses associated with HZ disease and complications.

The one-, two-, and three-way sensitivity analyses examined how different variables affected the cost-effectiveness of different vaccine strategies. The one-way analysis examined the association of input variables and cost-effectiveness. This included HZ/su prices, waning rate and initial efficacy of a dose of HZ/su, and the adherence rate. This analysis revealed that, compared with no vaccination, HZ/su would provide cost savings up to a price of $160, or $80 per dose.

Regardless of circumstance, HZ/su was always more effective than ZVL according to the two-way sensitivity analysis. This analysis took into account the joint effect of price, adherence to two doses of HZ/su, efficacy, and the waning rate of one dose and two doses of HZ/su and ZVL. Compared with ZVL, HZ/su would be less costly up to a price of $350 per series.

Adherence rates to vaccination schedules were important in determining the efficacy and waning rate which ultimately effected cost-effectiveness. The three-way sensitivity analysis found that, if HZ/su adherence to the second dose was greater than 56.8%, results were insensitive to the variation of single-dose efficacy and waning rate of HZ/su. But if adherence rates fell below 40%, combinations of waning rate and lower efficacy made HZ/su cost ineffective. Most importantly, ZVL was never cost effective for 60-year-old patients.

Despite a projected price of $280 per series, HZ/su is still more effective and less expensive than ZVL for adults 60 years or older. According to Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg, the assumptions about the vaccine’s efficacy duration and price were reasonable. But, if the vaccine price were to rise in the future, or a single dose becomes much less effective than reported by GlaxoSmithKline, or if adherence to the second dose was remarkably low, the results of the study would be changed.

“An ACIP recommendation stating a preference for HZ/su over ZVL could lead to future price increases, which would render the vaccine no longer cost effective” wrote Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg. “Therefore, a recommendation linked to periodic reassessment of cost-effectiveness based on the vaccine price might help to mitigate the effect of the recommendation on vaccine affordability.”

Dr. Le and Dr. Rothberg reported having no conflicts of interest.

The HZ/su vaccine is not yet approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but in 2017, the FDA Advisory Committee unanimously voted in favor of its use in adults age 50 years and older.

SOURCE: Phuc L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7431. Najafzadeh M. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7442.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Cost-effectiveness can be an important factor in considering patient treatment for herpes zoster.

Major finding:

Study details: The study was based on U.S. medical literature. Data were derived from adults 60 years or older in patient groups of 100-30,000 from July 1 to July 31, 2017.

Disclosures: None of the researchers had conflicts of interest to report.

Source: L. Phuc et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7431; Najafzadeh M. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7442.

For Patients With CKD, Don’t Wait—Vaccinate!

Q) What can I tell my kidney patients to increase acceptance of the influenza and pneumonia vaccines during cold and flu season?

The CDC recommends that everyone ages 6 months and older receive an annual flu vaccination, unless contraindicated.1 Additionally, administration of either the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) or the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for all adults ages 65 and older and for younger adults (ages 19 to 64) with diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic heart disease, and/or solid organ transplant.1 Despite these recommendations, patients often decline vaccination. What they may not realize is that CKD increases their risk for infection.

In a cohort of more than 1 million Swedish patients, researchers found that any stage of CKD increased risk for community-acquired infection and that the risk for lower respiratory tract infection increased as glomerular filtration rate declined.2 Patients on hemodialysis have an increased risk for pneumonia and an incidence of pneumonia-related mortality that is up to 16 times higher than that of the general population.3 Pneumonia also increases the risk for cardiovascular events among all patients with CKD, regardless of stage.4

So, can vaccines reduce these risks in our kidney patients? McGrath and colleagues found that patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who were vaccinated against the flu had lower mortality rates than those who were not vaccinated—even when the vaccine was poorly matched to the circulating virus strain.5 Additional research has demonstrated that for patients with any stage of CKD, including those on dialysis, the flu vaccine is safe and effective, and its protection may be durable over time.6

For pneumonia vaccines, antibody response in patients with CKD may be suboptimal; however, Medicare data have demonstrated that patients with ESRD who are vaccinated against pneumonia have lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than unvaccinated patients do.5 Given their increased vulnerability to vaccine-preventable respiratory illnesses, it is imperative that our kidney patients receive both the flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Nicole DeFeo McCormick, DNP, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

Assistant Professor

School of Medicine at the University of Colorado

1. CDC. Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Xu H, Gasparini A, Ishigami J, et al. eGFR and the risk of community-acquired infections. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(9):1399-1408.

3. Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL. Pulmonary infectious mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. Chest. 2001;120(6): 1883-1887.

4. Mathew R, Mason D, Kennedy JS. Vaccination issues in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):285-298.

5. McGrath LJ, Kshirsagar AV, Cole SR, et al. Evaluating influenza vaccine effectiveness among hemodialysis patients using a natural experiment. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7): 548-554.

6. Janus N, Vacher L, Karie S, et al. Vaccination and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):800-807.

Q) What can I tell my kidney patients to increase acceptance of the influenza and pneumonia vaccines during cold and flu season?

The CDC recommends that everyone ages 6 months and older receive an annual flu vaccination, unless contraindicated.1 Additionally, administration of either the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) or the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for all adults ages 65 and older and for younger adults (ages 19 to 64) with diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic heart disease, and/or solid organ transplant.1 Despite these recommendations, patients often decline vaccination. What they may not realize is that CKD increases their risk for infection.

In a cohort of more than 1 million Swedish patients, researchers found that any stage of CKD increased risk for community-acquired infection and that the risk for lower respiratory tract infection increased as glomerular filtration rate declined.2 Patients on hemodialysis have an increased risk for pneumonia and an incidence of pneumonia-related mortality that is up to 16 times higher than that of the general population.3 Pneumonia also increases the risk for cardiovascular events among all patients with CKD, regardless of stage.4

So, can vaccines reduce these risks in our kidney patients? McGrath and colleagues found that patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who were vaccinated against the flu had lower mortality rates than those who were not vaccinated—even when the vaccine was poorly matched to the circulating virus strain.5 Additional research has demonstrated that for patients with any stage of CKD, including those on dialysis, the flu vaccine is safe and effective, and its protection may be durable over time.6

For pneumonia vaccines, antibody response in patients with CKD may be suboptimal; however, Medicare data have demonstrated that patients with ESRD who are vaccinated against pneumonia have lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than unvaccinated patients do.5 Given their increased vulnerability to vaccine-preventable respiratory illnesses, it is imperative that our kidney patients receive both the flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Nicole DeFeo McCormick, DNP, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

Assistant Professor

School of Medicine at the University of Colorado

Q) What can I tell my kidney patients to increase acceptance of the influenza and pneumonia vaccines during cold and flu season?

The CDC recommends that everyone ages 6 months and older receive an annual flu vaccination, unless contraindicated.1 Additionally, administration of either the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) or the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for all adults ages 65 and older and for younger adults (ages 19 to 64) with diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic heart disease, and/or solid organ transplant.1 Despite these recommendations, patients often decline vaccination. What they may not realize is that CKD increases their risk for infection.

In a cohort of more than 1 million Swedish patients, researchers found that any stage of CKD increased risk for community-acquired infection and that the risk for lower respiratory tract infection increased as glomerular filtration rate declined.2 Patients on hemodialysis have an increased risk for pneumonia and an incidence of pneumonia-related mortality that is up to 16 times higher than that of the general population.3 Pneumonia also increases the risk for cardiovascular events among all patients with CKD, regardless of stage.4

So, can vaccines reduce these risks in our kidney patients? McGrath and colleagues found that patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who were vaccinated against the flu had lower mortality rates than those who were not vaccinated—even when the vaccine was poorly matched to the circulating virus strain.5 Additional research has demonstrated that for patients with any stage of CKD, including those on dialysis, the flu vaccine is safe and effective, and its protection may be durable over time.6

For pneumonia vaccines, antibody response in patients with CKD may be suboptimal; however, Medicare data have demonstrated that patients with ESRD who are vaccinated against pneumonia have lower rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than unvaccinated patients do.5 Given their increased vulnerability to vaccine-preventable respiratory illnesses, it is imperative that our kidney patients receive both the flu and pneumonia vaccines.

Nicole DeFeo McCormick, DNP, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

Assistant Professor

School of Medicine at the University of Colorado

1. CDC. Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Xu H, Gasparini A, Ishigami J, et al. eGFR and the risk of community-acquired infections. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(9):1399-1408.

3. Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL. Pulmonary infectious mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. Chest. 2001;120(6): 1883-1887.

4. Mathew R, Mason D, Kennedy JS. Vaccination issues in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):285-298.

5. McGrath LJ, Kshirsagar AV, Cole SR, et al. Evaluating influenza vaccine effectiveness among hemodialysis patients using a natural experiment. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7): 548-554.

6. Janus N, Vacher L, Karie S, et al. Vaccination and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):800-807.

1. CDC. Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html. Accessed November 22, 2017.

2. Xu H, Gasparini A, Ishigami J, et al. eGFR and the risk of community-acquired infections. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(9):1399-1408.

3. Sarnak MJ, Jaber BL. Pulmonary infectious mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. Chest. 2001;120(6): 1883-1887.

4. Mathew R, Mason D, Kennedy JS. Vaccination issues in patients with chronic kidney disease. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13(2):285-298.

5. McGrath LJ, Kshirsagar AV, Cole SR, et al. Evaluating influenza vaccine effectiveness among hemodialysis patients using a natural experiment. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7): 548-554.

6. Janus N, Vacher L, Karie S, et al. Vaccination and chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):800-807.

Don’t give up on influenza vaccine

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

I suspect most health care providers have heard the complaint, “The vaccine doesn’t work. One year I got the vaccine, and I still came down with the flu.”

Over the years, I’ve polished my responses to vaccine naysayers.

Influenza vaccine doesn’t protect you against every virus that can cause cold and flu symptoms. It only prevents influenza. It’s possible you had a different virus, such as adenovirus, coronavirus, parainfluenza virus, or respiratory syncytial virus.

Some years, the vaccine works better than others because there is a mismatch between the viruses chosen for the vaccine, and the viruses that end up circulating. Even when it doesn’t prevent flu, the vaccine can potentially reduce the severity of illness.

The discussion became a little more complicated in 2016 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices withdrew its support for the live attenuated influenza virus vaccine (LAIV4) because of concerns about effectiveness. During the 2015-2016 influenza season, LAIV4 demonstrated no statistically significant effectiveness in children 2-17 years of age against H1N1pdm09, the predominant influenza strain. Fortunately, inactivated injectable vaccine did offer protection. An estimated 41.8 million children aged 6 months to 17 years ultimately received this vaccine during the 2016-2017 influenza season.

Now with the 2017-2018 influenza season in full swing, some media reports are proclaiming the influenza vaccine is only 10% effective this year. This claim is based on an interim analysis of data from the most recent flu season in Australia and the effectiveness of the vaccine against the circulating H3N2 virus strain. News from the U.S. CDC is more encouraging. The H3N2 virus contained in this year’s vaccine is the same as that used last year, and so far, circulating H3N2 viruses in the United States are similar to the vaccine virus. Public health officials suggest that we can hope that the vaccine works as well as it did last year, when overall vaccine effectiveness against all circulating flu viruses was 39%, and effectiveness against the H3N2 virus specifically was 32%.

I’m upping my game when talking to parents about flu vaccine. I mention one study conducted between 2010 and 2012 in which influenza immunization reduced a child’s risk of being admitted to an intensive care unit with flu by 74% (J Infect Dis. 2014 Sep 1;210[5]:674-83). I emphasize that flu vaccine reduces the chance that a child will die from flu. According to a study published in 2017, influenza vaccine reduced the risk of death from flu by 65% in healthy children and 51% in children with high-risk medical conditions (Pediatrics. 2017 May. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4244).

When I’m talking to trainees, I no longer just focus on the match between circulating strains of flu and vaccine strains. I mention that viruses used to produce most seasonal flu vaccines are grown in eggs, a process that can result in minor antigenic changes in the hemagglutinin protein, especially in H3N2 viruses. These “egg-adapted changes” may result in a vaccine that stimulates a less effective immune response, even with a good match between circulating strains and vaccine strains. For example, Zost et al. found that the H3N2 virus that emerged during the 2014-2015 season possessed a new hemagglutinin-associated glycosylation site (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 21;114[47]:12578-83). Although this virus was represented in the 2016-2017 influenza vaccine, the egg-adapted version lost the glycosylation site, resulting in decreased vaccine immunogenicity and less protection against H3N2 viruses circulating in the community.

The real take-home message here is that we need better flu vaccines. In the short term, cell-based flu vaccines that use virus grown in animal cells are a potential alternative to egg-based vaccines. In the long term, we need a universal flu vaccine. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is prioritizing work on a vaccine that could provide long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. According to a report on the National Institutes of Health website, such a vaccine could “eliminate the need to update and administer the seasonal flu vaccine each year and could provide protection against newly emerging flu strains,” including those with the potential to cause a pandemic. The NIH researchers acknowledge, however, that achieving this goal will require “a broad range of expertise and substantial resources.”

Until new vaccines are available, we need to do a better job of using available, albeit imperfect, flu vaccines. During the 2016-2017 season, only 59% of children 6 months to 17 years were immunized, and there were 110 influenza-associated deaths in children, according to the CDC. It’s likely that some of these were preventable.

The total magnitude of suffering associated with flu is more difficult to quantify, but anecdotes can be illuminating. A friend recently diagnosed with influenza shared her experience via Facebook. “Rough night. I’m seconds away from a meltdown. My body aches so bad that I can’t get comfortable on the couch or my bed. Can’t breathe, and I cough until I vomit. My head is about to burst along with my ears. Just took a hot bath hoping that would help. I don’t know what else to do. The flu really sucks.”

Indeed. Even a 1 in 10 chance of preventing the flu is better than no chance at all.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

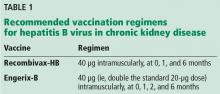

What is the hepatitis B vaccination regimen in chronic kidney disease?

For patients age 16 and older with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD), including those undergoing hemodialysis, we recommend a higher dose of hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine, more doses, or both. Vaccination with a higher dose may improve the immune response. The hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) titer should be monitored 1 to 2 months after completion of the vaccination schedule and annually thereafter, with a target titer of 10 IU/mL or greater. For patients who do not develop a protective antibody titer after completing the initial vaccination schedule, the vaccination schedule should be repeated.

RECOMMENDED DOSES AND SCHEDULES

Recommendation 1

Give higher vaccine doses, increase the number of doses, or both.

Recommendation 2

A 4-dose regimen may provide a better antibody response than a 3-dose regimen. (Note: This recommendation applies only to Engerix-B; 4 doses of Recombivax-HB would be an off-label use.)

Rationale. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that after completion of a 3-dose vaccination schedule, the median proportion of patients developing a protective antibody response was 64% (range 34%–88%) vs a median of 86% (range 40%–98%) after a 4-dose schedule.3

Lacson et al5 compared antibody response rates after 3 doses of Recombivax-HB and after 4 doses of Engerix-B and found a better response rate with the 4-dose schedule. The rate of persistent protective anti-HBs titer after 1 year was 77% for Engerix-B vs 53% for Recombivax-HB.

Agarwal et al6 evaluated response rates in patients who had mild CKD (serum creatinine levels 1.5–3.0 mg/dL), moderate CKD (creatinine 3.0–6.0 mg/dL), and severe CKD (creatinine > 6.0 mg/dL). The seroconversion rates after 3 doses of 40-μg HBV vaccine were 87.5% in those with mild CKD, 66.6% in those with moderate CKD, and 35.7% in those with severe disease. After a fourth dose, rates improved significantly to 100%, 77%, and 36.4%, respectively.

Recommendation 3

In patients with CKD, vaccination should be done early, before they become dependent on hemodialysis.

Rationale. Patients with advanced CKD may have a lower seroconversion rate. Fraser et al7 found that after a 4-dose series, the seroprotection rate in adult prehemodialysis patients with serum creatinine levels of 4 mg/dL or less was 86%, compared with 37% in patients with serum creatinine levels above 4 mg/dL, of whom 88% were on hemodialysis.7

In a 2003 prospective cohort study by DaRoza et al,8 patients with higher levels of kidney function were more likely to respond to HBV vaccination, and the level of kidney function was found to be an independent predictor of seroconversion.8

A 2012 prospective study by Ghadiani et al9 compared seroconversion rates in patients with stage 3 or 4 CKD vs patients on hemodialysis, with medical staff as controls. The authors reported seroprotection rates of 26.1% in patients on hemodialysis, 55.2% in patients with stage 3 or 4 CKD, and 96.2% in controls. They concluded that vaccination is more likely to induce seroconversion in earlier stages of kidney disease.9

MONITORING THE RESPONSE TO VACCINATION AND REVACCINATION

Testing after vaccination is recommended to determine response. Testing should be done 1 to 2 months after the last dose of the vaccination schedule.1–3 Anti-HBs levels 10 IU/mL and greater are considered protective.10

Revaccination with a full vaccination series is recommended for patients who do not develop adequate levels of protective antibodies after completion of the vaccination schedule.2 Reported response rates to revaccination have varied from 40% to 50% after 2 or 3 additional intramuscular doses of 40 µg, to 64% after 4 additional intramuscular doses of 10 µg.3 Serologic testing should be repeated after the last dose of the vaccination series, as serologic testing after only 1 or 2 additional doses appears to be no more cost-effective.2,3

To the best of our knowledge, no data exist to indicate that in nonresponders, further doses given after completion of 2 full vaccination schedules would induce an antibody response.

ANTIBODY PERSISTENCE AND BOOSTER DOSES

Antibody levels fall with time in patients on hemodialysis. Limited data suggest that in patients who respond to the primary vaccination series, antibodies remain detectable for 6 months in 80% to 100% (median 100%) of patients and for 12 months in 58% to 100% (median 70%) of patients.3 The need for booster doses should be assessed by annual monitoring.2,11 Booster doses should be given when the anti-HBs titer declines to below 10 IU/mL. Limited data indicate that nearly all such patients would respond to a booster dose.3

OTHER WAYS TO IMPROVE VACCINE RESPONSE

Other strategies to improve vaccine response, such as the addition of adjuvants or immunostimulants, have shown variable success.12 Intradermal HBV vaccination in patients on chronic hemodialysis has also been proposed. The efficacy of intradermal vaccination may be related to the dense network of immunologic dendritic cells within the dermis. After intradermal administration, the antigen is taken up by dendritic cells residing in the dermis, which mature and travel to the regional lymph node where further immunostimulation takes place.13

In a systematic review of four prospective trials with a total of 204 hemodialysis patients,13 a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved seroconversion with intradermal HBV vaccine administration than with intramuscular administration. The authors concluded that the intradermal route in primary nonresponders undergoing hemodialysis provides an effective alternative to the intramuscular route to protect against HBV infection in this highly susceptible population.

Additional well-designed, double-blinded, randomized trials are needed to establish clear guidelines on intradermal HBV vaccine dosing and vaccination schedules.

- Grzegorzewska AE. Hepatitis B vaccination in chronic kidney disease: review of evidence in non-dialyzed patients. Hepat Mon 2012; 12:e7359.

- Chi C, Patel P, Pilishvili T, Moore M, Murphy T, Strikas R. Guidelines for vaccinating kidney dialysis patients and patients with chronic kidney disease. www.cdc.gov/dialysis/PDFs/Vaccinating_Dialysis_Patients_and_Patients_dec2012.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- Recommendations for preventing transmission of infections among chronic hemodialysis patients. MMWR Recomm Rep 2001; 50:1–43.

- Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, Hunter P, Bridges CB; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166:209–219.

- Lacson E, Teng M, Ong J, Vienneau L, Ofsthun N, Lazarus JM. Antibody response to Engerix-B and Recombivax-HB hepatitis B vaccination in end-stage renal disease. Hemodialysis international. Hemodial Int 2005; 9:367–375.

- Agarwal SK, Irshad M, Dash SC. Comparison of two schedules of hepatitis B vaccination in patients with mild, moderate and severe renal failure. J Assoc Physicians India 1999; 47:183–185.

- Fraser GM, Ochana N, Fenyves D, et al. Increasing serum creatinine and age reduce the response to hepatitis B vaccine in renal failure patients. J Hepatol 1994; 21:450–454.

- DaRoza G, Loewen A, Djurdjev O, et al. Stage of chronic kidney disease predicts seroconversion after hepatitis B immunization: earlier is better. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42:1184–1192.

- Ghadiani MH, Besharati S, Mousavinasab N, Jalalzadeh M. Response rates to HB vaccine in CKD stages 3-4 and hemodialysis patients. J Res Med Sci 2012; 17:527–533.

- Jack AD, Hall AJ, Maine N, Mendy M, Whittle HC. What level of hepatitis B antibody is protective? J Infect Dis 1999; 179:489–492.

- Guidelines for vaccination in patients with chronic kidney disease. Indian J Nephrol 2016; 26(suppl 1):S15–S18.

- Somi MH, Hajipour B. Improving hepatitis B vaccine efficacy in end-stage renal diseases patients and role of adjuvants. ISRN Gastroenterol 2012; 2012:960413.

- Yousaf F, Gandham S, Galler M, Spinowitz B, Charytan C. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of intradermal versus intramuscular hepatitis B vaccination in end-stage renal disease population unresponsive to primary vaccination series. Ren Fail 2015; 37:1080–1088.

For patients age 16 and older with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD), including those undergoing hemodialysis, we recommend a higher dose of hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine, more doses, or both. Vaccination with a higher dose may improve the immune response. The hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) titer should be monitored 1 to 2 months after completion of the vaccination schedule and annually thereafter, with a target titer of 10 IU/mL or greater. For patients who do not develop a protective antibody titer after completing the initial vaccination schedule, the vaccination schedule should be repeated.

RECOMMENDED DOSES AND SCHEDULES

Recommendation 1

Give higher vaccine doses, increase the number of doses, or both.

Recommendation 2

A 4-dose regimen may provide a better antibody response than a 3-dose regimen. (Note: This recommendation applies only to Engerix-B; 4 doses of Recombivax-HB would be an off-label use.)

Rationale. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that after completion of a 3-dose vaccination schedule, the median proportion of patients developing a protective antibody response was 64% (range 34%–88%) vs a median of 86% (range 40%–98%) after a 4-dose schedule.3

Lacson et al5 compared antibody response rates after 3 doses of Recombivax-HB and after 4 doses of Engerix-B and found a better response rate with the 4-dose schedule. The rate of persistent protective anti-HBs titer after 1 year was 77% for Engerix-B vs 53% for Recombivax-HB.

Agarwal et al6 evaluated response rates in patients who had mild CKD (serum creatinine levels 1.5–3.0 mg/dL), moderate CKD (creatinine 3.0–6.0 mg/dL), and severe CKD (creatinine > 6.0 mg/dL). The seroconversion rates after 3 doses of 40-μg HBV vaccine were 87.5% in those with mild CKD, 66.6% in those with moderate CKD, and 35.7% in those with severe disease. After a fourth dose, rates improved significantly to 100%, 77%, and 36.4%, respectively.

Recommendation 3

In patients with CKD, vaccination should be done early, before they become dependent on hemodialysis.

Rationale. Patients with advanced CKD may have a lower seroconversion rate. Fraser et al7 found that after a 4-dose series, the seroprotection rate in adult prehemodialysis patients with serum creatinine levels of 4 mg/dL or less was 86%, compared with 37% in patients with serum creatinine levels above 4 mg/dL, of whom 88% were on hemodialysis.7

In a 2003 prospective cohort study by DaRoza et al,8 patients with higher levels of kidney function were more likely to respond to HBV vaccination, and the level of kidney function was found to be an independent predictor of seroconversion.8

A 2012 prospective study by Ghadiani et al9 compared seroconversion rates in patients with stage 3 or 4 CKD vs patients on hemodialysis, with medical staff as controls. The authors reported seroprotection rates of 26.1% in patients on hemodialysis, 55.2% in patients with stage 3 or 4 CKD, and 96.2% in controls. They concluded that vaccination is more likely to induce seroconversion in earlier stages of kidney disease.9

MONITORING THE RESPONSE TO VACCINATION AND REVACCINATION

Testing after vaccination is recommended to determine response. Testing should be done 1 to 2 months after the last dose of the vaccination schedule.1–3 Anti-HBs levels 10 IU/mL and greater are considered protective.10

Revaccination with a full vaccination series is recommended for patients who do not develop adequate levels of protective antibodies after completion of the vaccination schedule.2 Reported response rates to revaccination have varied from 40% to 50% after 2 or 3 additional intramuscular doses of 40 µg, to 64% after 4 additional intramuscular doses of 10 µg.3 Serologic testing should be repeated after the last dose of the vaccination series, as serologic testing after only 1 or 2 additional doses appears to be no more cost-effective.2,3

To the best of our knowledge, no data exist to indicate that in nonresponders, further doses given after completion of 2 full vaccination schedules would induce an antibody response.

ANTIBODY PERSISTENCE AND BOOSTER DOSES

Antibody levels fall with time in patients on hemodialysis. Limited data suggest that in patients who respond to the primary vaccination series, antibodies remain detectable for 6 months in 80% to 100% (median 100%) of patients and for 12 months in 58% to 100% (median 70%) of patients.3 The need for booster doses should be assessed by annual monitoring.2,11 Booster doses should be given when the anti-HBs titer declines to below 10 IU/mL. Limited data indicate that nearly all such patients would respond to a booster dose.3

OTHER WAYS TO IMPROVE VACCINE RESPONSE

Other strategies to improve vaccine response, such as the addition of adjuvants or immunostimulants, have shown variable success.12 Intradermal HBV vaccination in patients on chronic hemodialysis has also been proposed. The efficacy of intradermal vaccination may be related to the dense network of immunologic dendritic cells within the dermis. After intradermal administration, the antigen is taken up by dendritic cells residing in the dermis, which mature and travel to the regional lymph node where further immunostimulation takes place.13

In a systematic review of four prospective trials with a total of 204 hemodialysis patients,13 a significantly higher proportion of patients achieved seroconversion with intradermal HBV vaccine administration than with intramuscular administration. The authors concluded that the intradermal route in primary nonresponders undergoing hemodialysis provides an effective alternative to the intramuscular route to protect against HBV infection in this highly susceptible population.

Additional well-designed, double-blinded, randomized trials are needed to establish clear guidelines on intradermal HBV vaccine dosing and vaccination schedules.

For patients age 16 and older with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD), including those undergoing hemodialysis, we recommend a higher dose of hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine, more doses, or both. Vaccination with a higher dose may improve the immune response. The hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) titer should be monitored 1 to 2 months after completion of the vaccination schedule and annually thereafter, with a target titer of 10 IU/mL or greater. For patients who do not develop a protective antibody titer after completing the initial vaccination schedule, the vaccination schedule should be repeated.

RECOMMENDED DOSES AND SCHEDULES

Recommendation 1

Give higher vaccine doses, increase the number of doses, or both.

Recommendation 2

A 4-dose regimen may provide a better antibody response than a 3-dose regimen. (Note: This recommendation applies only to Engerix-B; 4 doses of Recombivax-HB would be an off-label use.)