User login

Large study finds no link between gluten, IBD risk

Among women without celiac disease, dietary gluten intake was not associated with the risk of developing either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, investigators reported.

The findings spanned subgroups stratified by age, body mass index, smoking status, and whether individuals primarily consumed refined or whole grains, said Emily Walsh Lopes, MD, gastroenterology clinical and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. She and associates reported the combined analysis of the prospective Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II in an abstract released as part of the annual Digestive Disease Week.®

“Avoidance of dietary gluten is common, and many patients attribute gastrointestinal symptoms to gluten intake,” Dr. Lopes said in an interview. “Though our findings warrant further study, the results suggest to patients and providers that eating gluten does not increase a person’s chance of getting diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease.”

Prior studies have found that many individuals with inflammatory bowel disease avoid gluten and report subsequent improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms, even if they do not have celiac disease. However, it remains unclear whether dietary gluten is a risk factor for new-onset inflammatory bowel disease.

To address this question, Dr. Lopes and associates analyzed data collected from 165,327 women who took part in the Nurses’ Health Study (1986 to 2016) or the Nurses’ Health Study II (1991 through 2017). None of the women had a preexisting diagnosis of celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease. Dietary gluten intake was estimated based on food frequency questionnaires completed by the women at baseline and every 4 years. The researchers also reviewed medical records to confirm self-reported cases of new-onset ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Over 4.02 million person-years of follow-up, 277 women developed Crohn’s disease and 359 developed ulcerative colitis. Gluten intake was not associated with the risk of either type of inflammatory bowel disease, even after the researchers controlled for multiple demographic and clinical risk factors.

After submitting their abstract, Dr. Lopes and coinvestigators expanded the dataset to include a large cohort of men from the prospective Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The final pooled cohort included more than 208,000 women and men followed for more than 20 years. Through the end of follow-up, the researchers documented 337 cases of Crohn’s disease and 446 cases of ulcerative colitis. “Inclusion of the male cohort in the pooled analysis did not materially change our estimates,” Dr. Lopes told MDedge. “That is, no association was seen between gluten intake and risk of either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis in the final cohort.”

She noted that the findings cannot be extrapolated to individuals who are already diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease. “It is possible that different mechanisms exist to explain how gluten intake impacts those already diagnosed with IBD, and this topic warrants further study,” she said. Also, because the three cohort studies were observational, they are subject to bias. “While we tried to account for this in our analyses, residual bias may still exist.”

Dr. Lopes reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Walsh Lopes E et al. DDW 2020, abstract 847.

Among women without celiac disease, dietary gluten intake was not associated with the risk of developing either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, investigators reported.

The findings spanned subgroups stratified by age, body mass index, smoking status, and whether individuals primarily consumed refined or whole grains, said Emily Walsh Lopes, MD, gastroenterology clinical and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. She and associates reported the combined analysis of the prospective Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II in an abstract released as part of the annual Digestive Disease Week.®

“Avoidance of dietary gluten is common, and many patients attribute gastrointestinal symptoms to gluten intake,” Dr. Lopes said in an interview. “Though our findings warrant further study, the results suggest to patients and providers that eating gluten does not increase a person’s chance of getting diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease.”

Prior studies have found that many individuals with inflammatory bowel disease avoid gluten and report subsequent improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms, even if they do not have celiac disease. However, it remains unclear whether dietary gluten is a risk factor for new-onset inflammatory bowel disease.

To address this question, Dr. Lopes and associates analyzed data collected from 165,327 women who took part in the Nurses’ Health Study (1986 to 2016) or the Nurses’ Health Study II (1991 through 2017). None of the women had a preexisting diagnosis of celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease. Dietary gluten intake was estimated based on food frequency questionnaires completed by the women at baseline and every 4 years. The researchers also reviewed medical records to confirm self-reported cases of new-onset ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Over 4.02 million person-years of follow-up, 277 women developed Crohn’s disease and 359 developed ulcerative colitis. Gluten intake was not associated with the risk of either type of inflammatory bowel disease, even after the researchers controlled for multiple demographic and clinical risk factors.

After submitting their abstract, Dr. Lopes and coinvestigators expanded the dataset to include a large cohort of men from the prospective Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The final pooled cohort included more than 208,000 women and men followed for more than 20 years. Through the end of follow-up, the researchers documented 337 cases of Crohn’s disease and 446 cases of ulcerative colitis. “Inclusion of the male cohort in the pooled analysis did not materially change our estimates,” Dr. Lopes told MDedge. “That is, no association was seen between gluten intake and risk of either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis in the final cohort.”

She noted that the findings cannot be extrapolated to individuals who are already diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease. “It is possible that different mechanisms exist to explain how gluten intake impacts those already diagnosed with IBD, and this topic warrants further study,” she said. Also, because the three cohort studies were observational, they are subject to bias. “While we tried to account for this in our analyses, residual bias may still exist.”

Dr. Lopes reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Walsh Lopes E et al. DDW 2020, abstract 847.

Among women without celiac disease, dietary gluten intake was not associated with the risk of developing either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, investigators reported.

The findings spanned subgroups stratified by age, body mass index, smoking status, and whether individuals primarily consumed refined or whole grains, said Emily Walsh Lopes, MD, gastroenterology clinical and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. She and associates reported the combined analysis of the prospective Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II in an abstract released as part of the annual Digestive Disease Week.®

“Avoidance of dietary gluten is common, and many patients attribute gastrointestinal symptoms to gluten intake,” Dr. Lopes said in an interview. “Though our findings warrant further study, the results suggest to patients and providers that eating gluten does not increase a person’s chance of getting diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease.”

Prior studies have found that many individuals with inflammatory bowel disease avoid gluten and report subsequent improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms, even if they do not have celiac disease. However, it remains unclear whether dietary gluten is a risk factor for new-onset inflammatory bowel disease.

To address this question, Dr. Lopes and associates analyzed data collected from 165,327 women who took part in the Nurses’ Health Study (1986 to 2016) or the Nurses’ Health Study II (1991 through 2017). None of the women had a preexisting diagnosis of celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease. Dietary gluten intake was estimated based on food frequency questionnaires completed by the women at baseline and every 4 years. The researchers also reviewed medical records to confirm self-reported cases of new-onset ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Over 4.02 million person-years of follow-up, 277 women developed Crohn’s disease and 359 developed ulcerative colitis. Gluten intake was not associated with the risk of either type of inflammatory bowel disease, even after the researchers controlled for multiple demographic and clinical risk factors.

After submitting their abstract, Dr. Lopes and coinvestigators expanded the dataset to include a large cohort of men from the prospective Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The final pooled cohort included more than 208,000 women and men followed for more than 20 years. Through the end of follow-up, the researchers documented 337 cases of Crohn’s disease and 446 cases of ulcerative colitis. “Inclusion of the male cohort in the pooled analysis did not materially change our estimates,” Dr. Lopes told MDedge. “That is, no association was seen between gluten intake and risk of either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis in the final cohort.”

She noted that the findings cannot be extrapolated to individuals who are already diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease. “It is possible that different mechanisms exist to explain how gluten intake impacts those already diagnosed with IBD, and this topic warrants further study,” she said. Also, because the three cohort studies were observational, they are subject to bias. “While we tried to account for this in our analyses, residual bias may still exist.”

Dr. Lopes reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Walsh Lopes E et al. DDW 2020, abstract 847.

FROM DDW 2020

High ‘forever chemicals’ in blood linked to earlier menopause

In a national sample of U.S. women in their mid-40s to mid-50s, those with high serum levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were likely to enter menopause 2 years earlier than those with low levels of these chemicals.

That is, the median age of natural menopause was 52.8 years versus 50.8 years in women with high versus low serum levels of these chemicals in an analysis of data from more than 1,100 women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Multi-Pollutant Study, which excluded women with premature menopause (before age 40) or early menopause (before age 45).

“This study suggests that select PFAS serum concentrations are associated with earlier natural menopause, a risk factor for adverse health outcomes in later life,” Ning Ding, PhD, MPH, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues concluded in their article, published online June 3 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Even menopause a few years earlier than usual could have a significant impact on cardiovascular and bone health, quality of life, and overall health in general among women,” senior author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, from the same institution, added in a statement.

PFAS don’t break down in the body, build up with time

PFAS have been widely used in many consumer and industrial products such as nonstick cookware, stain-repellent carpets, waterproof rain gear, microwave popcorn bags, and firefighting foam, the authors explained.

These have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they do not degrade. Household water for an estimated 110 million Americans (one in three) may be contaminated with these chemicals, according to an Endocrine Society press release.

“PFAS are everywhere. Once they enter the body, they don’t break down and [they] build up over time,” said Dr. Ding. “Because of their persistence in humans and potentially detrimental effects on ovarian function, it is important to raise awareness of this issue and reduce exposure to these chemicals.”

Environmental exposure and accelerated ovarian aging

Earlier menopause has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and earlier cardiovascular and overall mortality, and environmental exposure may accelerate ovarian aging, the authors wrote.

PFAS, especially the most studied types – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) – are plausible endocrine-disrupting chemicals, but findings so far have been inconsistent.

A study of people in Ohio exposed to contaminated water found that women with earlier natural menopause had higher serum PFOA and PFOS levels (J Clin Endocriniol Metab. 2011;96:1747-53).

But in research based on National Health and Nutrition Survey Examination data, higher PFOA, PFOS, or perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) levels were not linked to earlier menopause, although higher levels of perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) were (Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:145-50).

There may have been reverse causation, where postmenopausal women had higher PFAS levels because they were not excreting these chemicals in menstrual blood.

In a third study, PFOA exposure was not linked with age at menopause onset, but this was based on recall from 10 years earlier (Environ Res. 2016;146:323-30).

The current analysis examined data from 1,120 premenopausal women who were aged 45-56 years from 1999 to 2000.

The women were seen at five sites (Boston; Detroit; Los Angeles; Oakland, Calif.; and Pittsburgh) and were ethnically diverse (577 white, 235 black, 142 Chinese, and 166 Japanese).

Baseline serum PFAS levels were measured using high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The women were followed up to 2017 and incident menopause (12 consecutive months with no menstruation) was determined from annual interviews.

Of the 1,120 women and 5,466 person-years of follow-up, 578 women had a known date of natural incident menopause and were included in the analysis. The remaining 542 women were excluded mainly because their date of final menstruation was unknown because of hormone therapy (451) or they had a hysterectomy, or did not enter menopause during the study.

Compared with women in the lowest tertile of PFOS levels, women in the highest tertile had a significant 26%-27% greater risk of incident menopause – after adjusting for age, body mass index, and prior hormone use, race/ethnicity, study site, education, physical activity, smoking status, and parity.

Higher PFOA and PFNA levels but not higher PFHxS levels were also associated with increased risk.

Compared with women with a low overall PFAS level, those with a high level had a 63% increased risk of incident menopause (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.45), equivalent to having menopause a median of 2 years earlier.

Although production and use of some types of PFAS in the United States are declining, Dr. Ding and colleagues wrote, exposure continues, along with associated potential hazards to human reproductive health.

“Due to PFAS widespread use and environmental persistence, their potential adverse effects remain a public health concern,” they concluded.

SWAN was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health & Human Services through the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the SWAN repository. The current article was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a national sample of U.S. women in their mid-40s to mid-50s, those with high serum levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were likely to enter menopause 2 years earlier than those with low levels of these chemicals.

That is, the median age of natural menopause was 52.8 years versus 50.8 years in women with high versus low serum levels of these chemicals in an analysis of data from more than 1,100 women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Multi-Pollutant Study, which excluded women with premature menopause (before age 40) or early menopause (before age 45).

“This study suggests that select PFAS serum concentrations are associated with earlier natural menopause, a risk factor for adverse health outcomes in later life,” Ning Ding, PhD, MPH, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues concluded in their article, published online June 3 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Even menopause a few years earlier than usual could have a significant impact on cardiovascular and bone health, quality of life, and overall health in general among women,” senior author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, from the same institution, added in a statement.

PFAS don’t break down in the body, build up with time

PFAS have been widely used in many consumer and industrial products such as nonstick cookware, stain-repellent carpets, waterproof rain gear, microwave popcorn bags, and firefighting foam, the authors explained.

These have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they do not degrade. Household water for an estimated 110 million Americans (one in three) may be contaminated with these chemicals, according to an Endocrine Society press release.

“PFAS are everywhere. Once they enter the body, they don’t break down and [they] build up over time,” said Dr. Ding. “Because of their persistence in humans and potentially detrimental effects on ovarian function, it is important to raise awareness of this issue and reduce exposure to these chemicals.”

Environmental exposure and accelerated ovarian aging

Earlier menopause has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and earlier cardiovascular and overall mortality, and environmental exposure may accelerate ovarian aging, the authors wrote.

PFAS, especially the most studied types – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) – are plausible endocrine-disrupting chemicals, but findings so far have been inconsistent.

A study of people in Ohio exposed to contaminated water found that women with earlier natural menopause had higher serum PFOA and PFOS levels (J Clin Endocriniol Metab. 2011;96:1747-53).

But in research based on National Health and Nutrition Survey Examination data, higher PFOA, PFOS, or perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) levels were not linked to earlier menopause, although higher levels of perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) were (Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:145-50).

There may have been reverse causation, where postmenopausal women had higher PFAS levels because they were not excreting these chemicals in menstrual blood.

In a third study, PFOA exposure was not linked with age at menopause onset, but this was based on recall from 10 years earlier (Environ Res. 2016;146:323-30).

The current analysis examined data from 1,120 premenopausal women who were aged 45-56 years from 1999 to 2000.

The women were seen at five sites (Boston; Detroit; Los Angeles; Oakland, Calif.; and Pittsburgh) and were ethnically diverse (577 white, 235 black, 142 Chinese, and 166 Japanese).

Baseline serum PFAS levels were measured using high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The women were followed up to 2017 and incident menopause (12 consecutive months with no menstruation) was determined from annual interviews.

Of the 1,120 women and 5,466 person-years of follow-up, 578 women had a known date of natural incident menopause and were included in the analysis. The remaining 542 women were excluded mainly because their date of final menstruation was unknown because of hormone therapy (451) or they had a hysterectomy, or did not enter menopause during the study.

Compared with women in the lowest tertile of PFOS levels, women in the highest tertile had a significant 26%-27% greater risk of incident menopause – after adjusting for age, body mass index, and prior hormone use, race/ethnicity, study site, education, physical activity, smoking status, and parity.

Higher PFOA and PFNA levels but not higher PFHxS levels were also associated with increased risk.

Compared with women with a low overall PFAS level, those with a high level had a 63% increased risk of incident menopause (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.45), equivalent to having menopause a median of 2 years earlier.

Although production and use of some types of PFAS in the United States are declining, Dr. Ding and colleagues wrote, exposure continues, along with associated potential hazards to human reproductive health.

“Due to PFAS widespread use and environmental persistence, their potential adverse effects remain a public health concern,” they concluded.

SWAN was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health & Human Services through the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the SWAN repository. The current article was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a national sample of U.S. women in their mid-40s to mid-50s, those with high serum levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) were likely to enter menopause 2 years earlier than those with low levels of these chemicals.

That is, the median age of natural menopause was 52.8 years versus 50.8 years in women with high versus low serum levels of these chemicals in an analysis of data from more than 1,100 women in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Multi-Pollutant Study, which excluded women with premature menopause (before age 40) or early menopause (before age 45).

“This study suggests that select PFAS serum concentrations are associated with earlier natural menopause, a risk factor for adverse health outcomes in later life,” Ning Ding, PhD, MPH, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues concluded in their article, published online June 3 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Even menopause a few years earlier than usual could have a significant impact on cardiovascular and bone health, quality of life, and overall health in general among women,” senior author Sung Kyun Park, ScD, MPH, from the same institution, added in a statement.

PFAS don’t break down in the body, build up with time

PFAS have been widely used in many consumer and industrial products such as nonstick cookware, stain-repellent carpets, waterproof rain gear, microwave popcorn bags, and firefighting foam, the authors explained.

These have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they do not degrade. Household water for an estimated 110 million Americans (one in three) may be contaminated with these chemicals, according to an Endocrine Society press release.

“PFAS are everywhere. Once they enter the body, they don’t break down and [they] build up over time,” said Dr. Ding. “Because of their persistence in humans and potentially detrimental effects on ovarian function, it is important to raise awareness of this issue and reduce exposure to these chemicals.”

Environmental exposure and accelerated ovarian aging

Earlier menopause has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and earlier cardiovascular and overall mortality, and environmental exposure may accelerate ovarian aging, the authors wrote.

PFAS, especially the most studied types – perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) – are plausible endocrine-disrupting chemicals, but findings so far have been inconsistent.

A study of people in Ohio exposed to contaminated water found that women with earlier natural menopause had higher serum PFOA and PFOS levels (J Clin Endocriniol Metab. 2011;96:1747-53).

But in research based on National Health and Nutrition Survey Examination data, higher PFOA, PFOS, or perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) levels were not linked to earlier menopause, although higher levels of perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) were (Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:145-50).

There may have been reverse causation, where postmenopausal women had higher PFAS levels because they were not excreting these chemicals in menstrual blood.

In a third study, PFOA exposure was not linked with age at menopause onset, but this was based on recall from 10 years earlier (Environ Res. 2016;146:323-30).

The current analysis examined data from 1,120 premenopausal women who were aged 45-56 years from 1999 to 2000.

The women were seen at five sites (Boston; Detroit; Los Angeles; Oakland, Calif.; and Pittsburgh) and were ethnically diverse (577 white, 235 black, 142 Chinese, and 166 Japanese).

Baseline serum PFAS levels were measured using high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The women were followed up to 2017 and incident menopause (12 consecutive months with no menstruation) was determined from annual interviews.

Of the 1,120 women and 5,466 person-years of follow-up, 578 women had a known date of natural incident menopause and were included in the analysis. The remaining 542 women were excluded mainly because their date of final menstruation was unknown because of hormone therapy (451) or they had a hysterectomy, or did not enter menopause during the study.

Compared with women in the lowest tertile of PFOS levels, women in the highest tertile had a significant 26%-27% greater risk of incident menopause – after adjusting for age, body mass index, and prior hormone use, race/ethnicity, study site, education, physical activity, smoking status, and parity.

Higher PFOA and PFNA levels but not higher PFHxS levels were also associated with increased risk.

Compared with women with a low overall PFAS level, those with a high level had a 63% increased risk of incident menopause (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.45), equivalent to having menopause a median of 2 years earlier.

Although production and use of some types of PFAS in the United States are declining, Dr. Ding and colleagues wrote, exposure continues, along with associated potential hazards to human reproductive health.

“Due to PFAS widespread use and environmental persistence, their potential adverse effects remain a public health concern,” they concluded.

SWAN was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health & Human Services through the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the SWAN repository. The current article was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing a woman with BRCA mutations? Shared decision-making is key

CASE

Sara T* recently moved back to the area to be closer to her family. The 34-year-old patient visited our office to discuss the benefits and potential risks of genetic counseling. She explained that her aunt had just died at age 64 of ovarian cancer. Also, her maternal cousin had been diagnosed at age 42 with breast cancer, and her maternal grandmother had died at age 45 of an unknown “female cancer.” She was scared to find out if she had high-risk genes because she felt it would change her life forever. However, if she ignored the issue, she thought she might worry too much.

We discussed the implications of a positive result, such as having to live with the knowledge and to make decisions about potential screening and risk-reducing surgery. On the other hand, not knowing could allow for the undetected growth of cancer that might otherwise be mitigated to some degree if she knew her risk status and pursued an aggressive screening program.

We worked with Ms. T to map out her next steps.

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women worldwide, representing nearly one-quarter of all female cancer diagnoses in 2018.1 It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in women in developed nations and the leading cause of cancer death in women in developing nations.1 In the United States, 1 in 8 women will develop breast cancer in her lifetime.2 By comparison, the rate of ovarian cancer is much lower, with a lifetime prevalence of 1 in 70 to 80 women.3,4 Although ovarian cancer is less common than breast cancer, its associated mortality is high, and most cases are discovered at advanced stages.

The outsized threat of BRCA mutations. It is estimated that 5% to 10% of all breast cancers are hereditary, with 80% of these attributable to BRCA1 (45%) and BRCA2 (35%).5 These autosomal dominant mutations occur at the germline level, within the egg or sperm, and are therefore incorporated into the DNA of every cell and passed from one generation to the next. Families with BRCA mutations have much higher lifetime rates of cancer. The lifetime risk of breast cancer due to BRCA mutations is estimated at > 80% (BRCA1) and 45% (BRCA2).5BRCA mutations account for between

Male BRCA carriers have a lifetime breast cancer risk of 1% to 5% with BRCA1 and 5% to 10% with BRCA2,7,8 compared with about 1:1000 lifetime incidence in the unselected male population. Male carriers are also at risk for more aggressive prostate cancers.7,8

Continue to: Certain populatiosn carry undue burden of BRCA-related disease

Certain populations carry undue burden of BRCA-related disease due to specific founder mutations. While the estimated global prevalence of BRCA mutations is 0.2% to 1%, for those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent the range is 2% to 3%, representing a relative risk up to 15 times that of the general population.9 Hispanic Americans also appear to have higher rates of BRCA-related cancers.10 Ongoing genetics research continues to identify founder mutations worldwide,10 which may inform future screening guidelines.

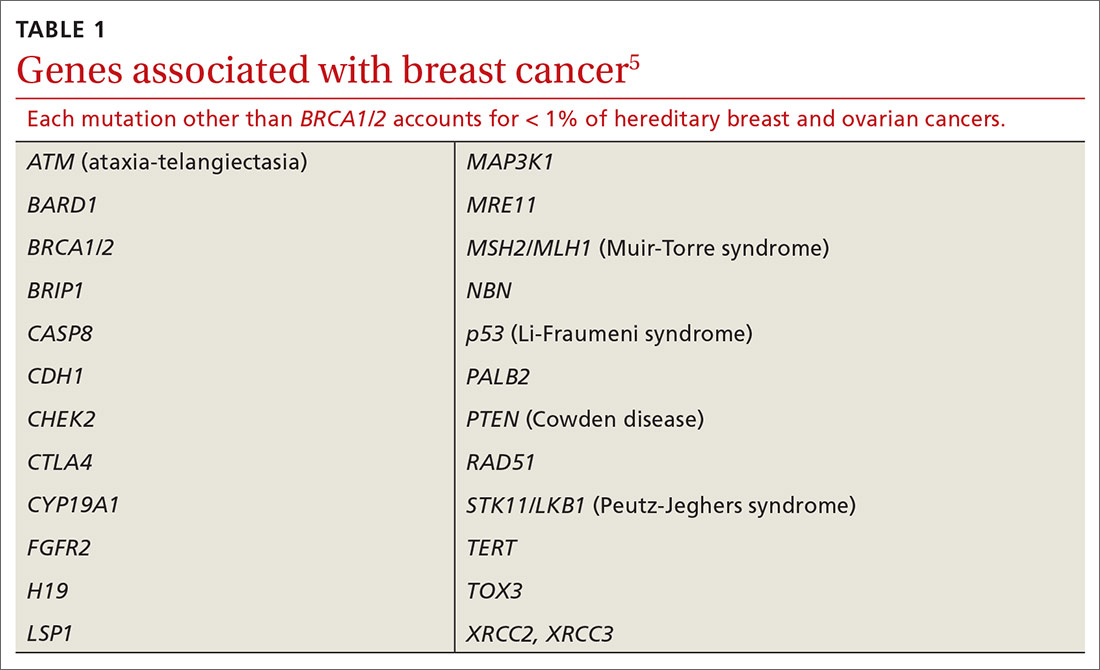

In addition to BRCA mutations, there are other, less common mutations (TABLE 15) known to cause hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

Identifying BRCA genes enables treatment planning. Compared with sporadic cancers, BRCA-related breast cancers

Similarly, BRCA-related ovarian cancer is more likely to be high-grade and endometrioid or serous subtype.14

Shared decision-making helps give clarity to the way forward

Shared decision-making is a process of communication whereby the clinician and the patient identify a decision to be made, review data relevant to clinical options, discuss patient perspectives and preferences regarding each option, and arrive at the decision together.17 Shared decision-making is important when treating women with BRCA mutations because there is no single correct plan. Individual values and competing medical issues may strongly guide each woman’s decisions about screening and cancer prevention treatment decisions.

Continue to: Shared decision-making in this situation...

Shared decision-making in this situation is a strategy to use the evidence of risk along with patient preferences around fertility issues to help come to a decision that is the right one for the patient. Primary care clinicians aware of the general risks and benefits of each available option can refer women at high risk for breast or ovarian cancer to a specialist multidisciplinary clinic that can provide tailored risk assessment and risk reduction counseling as needed.18-20

Genetic screening recommendations

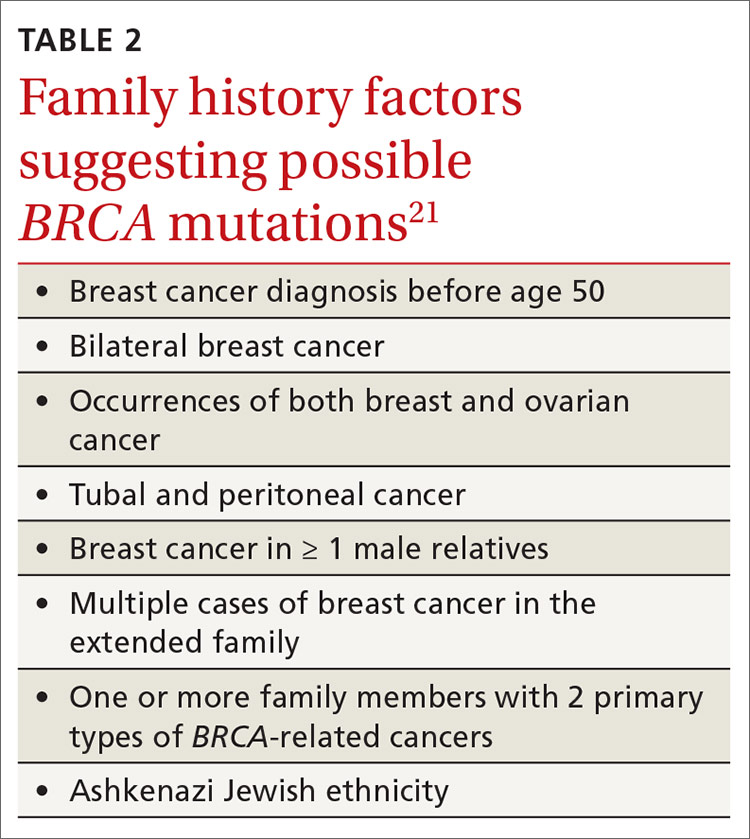

Screening is recommended for women who have any 1 of several family risk factors (TABLE 221). A number of risk assessment tools are available for primary care clinicians to determine which patients are at high enough risk for a hereditary breast or ovarian cancer to warrant referral to a genetic counselor.22-25 If screening suggests high risk, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends (Grade B) referral for genetic counseling.21

Explain to patients who are candidates for further investigation that a genetic counselor will review their family history and recommend testing for the specific mutations that increase cancer risk. Discuss potential benefits and harms of genetic testing. A benefit of genetic testing is that aggressive screening may suggest preventive procedures to reduce the risk of future cancer. Most tests come back definitively positive or negative, but an indeterminate result may cause harm. A small minority of results may indicate a genetic variant of unknown significance. The ramifications of this variant may not be known. Some women will experience anxiety about nonspecific test results and will be afraid to share them with family members. There is also some concern about privacy issues, potential insurance bias, and coverage of any preventive strategies.26

CASE

Based on Ms. T’s family history and her desire to know more, we referred her to a genetic counselor and she decided to undergo genetic testing. She screened positive for BRCA1. Ms. T was in a serious relationship and thought she would like to have children at some point. She returned to our office after receiving the positive genetic test results, wondering about screening for breast and ovarian cancer.

Breast cancer screening and risk-reduction strategies

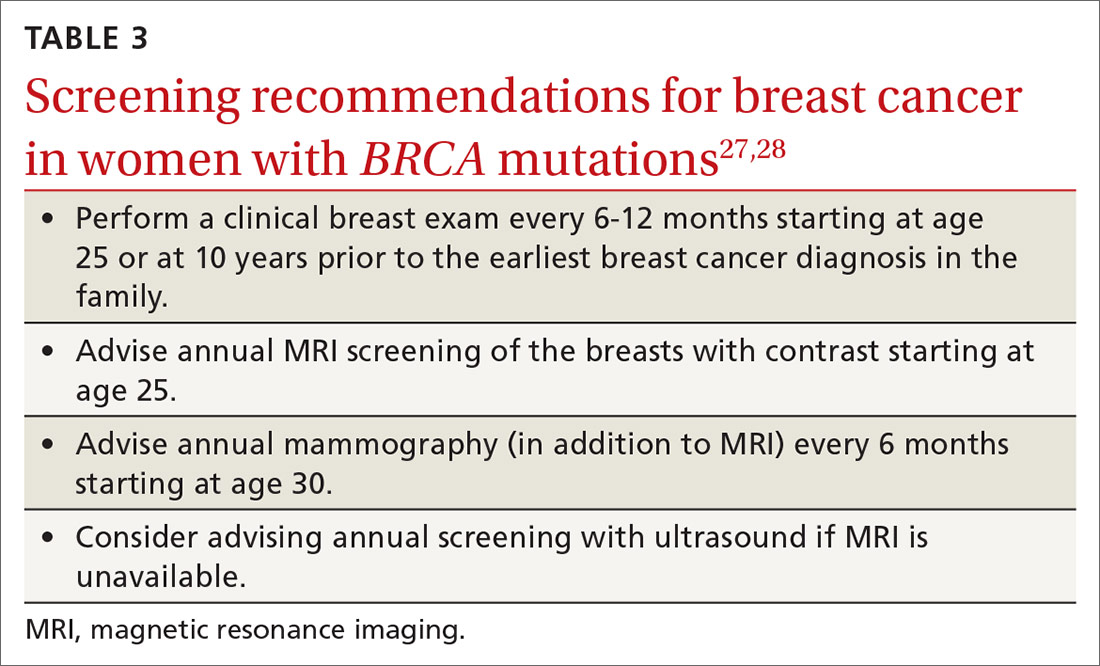

Screening. Because the risk of breast cancer is high in women with BRCA mutations, and because cancer in these women is more likely to be advanced at diagnosis, starting a screening program at an early age is prudent. Observational studies suggest that breastfeeding reduces the risk of breast and ovarian cancer in women with BRCA mutations, as it does for women in the general population.27 Women should return for a clinical breast exam every 6 to 12 months starting at age 25; they should start radiologic screening with magnetic resonance imaging at age 25 and mammography at age 30 (TABLE 327,28).

Continue to: Risk-reduction strategies

Risk-reduction strategies. There is weak evidence to support the use of tamoxifen or other synthetic estrogen reuptake modulators (SERMs) to reduce breast cancer risk in women with BRCA mutations. Many of these cancers do not express estrogen receptors, which may explain the lack of efficacy in certain cases. Several observational studies have shown that tamoxifen can reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations who have already been diagnosed with cancer in the other breast.29-31 However, tamoxifen does not reduce a patient’s risk of ovarian cancer, and it may increase her risk of uterine cancer.

Prophylactic bilateral mastectomy is the mainstay of breast cancer prevention in this population. Data from a systematic review suggest that this surgery may prevent the incidence of breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations by 90% to 95%.32 However, this review did not demonstrate a reduction in mortality from breast cancer, likely due to poor data quality.32 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends discussing prophylactic mastectomy with all women who have BRCA mutations.28 Further conversations are important to review the risk of tissue left behind and quality-of-life issues, including the inability to breastfeed if the woman wants more children and the cosmetic changes with reconstruction.

Ovarian cancer screening and risk-reduction strategies

Screening. No effective screening strategy has been endorsed for ovarian cancer, as most previous studies have shown screening to be ineffective.26,33 Recently, studies both in the United Kingdom and the United States have investigated a screening strategy using the risk-of-ovarian-cancer algorithm (ROCA), which calculates an individual’s risk based on serum levels of cancer antigen 125 (CA-125).34,35 These studies measured CA-125 levels every 3 to 4 months followed by transvaginal ultrasound if CA-125 increased substantially (as determined by ROCA). Absent an abnormal increase in CA-125, transvaginal ultrasound was performed annually. These screening strategies showed improved specificity over annual screening programs, and the cancers detected were more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage (stage II vs stage III) and had higher rates of zero residual disease after surgery compared with those detected 1 year after screening ended.34,35 However, survival data are not yet available. More research is needed to determine if more frequent screening approaches could improve survival in high-risk women.

NCCN and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) do not endorse routine screening with transvaginal ultrasound and serum CA-125 for high-risk women, as the benefits are uncertain. However, they do advise that these screens may be considered as a short-term strategy for women ages 30 to 35 who defer risk-reducing surgery.26,36 The USPSTF does not make a recommendation regarding ovarian cancer screening in high-risk women.37

Risk-reduction strategies. Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) is the only recommended technique for reducing the risk of ovarian cancer in women at high risk.26,33,36 Meta-analyses have shown an 80% reduction in ovarian cancer risk16 and 68% reduction in all-cause mortality with this approach.38 The NCCN recommends RRSO for women with a known BRCA1 mutation between the ages of 35 and 40 who have completed childbearing.36 Since the onset of ovarian cancer tends to be later in women with BRCA2 mutations, it is reasonable to delay RRSO until age 40 to 45 in this population if they have taken other steps to maximize breast cancer prevention (ie, bilateral mastectomy).36

Continue to: Adverse effects of RRSO...

Adverse effects of RRSO include surgery complications (wound infection, small bowel obstruction, bladder perforation) and effects of early menopause (vasomotor symptoms, decreased sexual functioning, and increased risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality).39-41 In the absence of contraindications, ACOG recommends using hormone therapy in women undergoing RRSO until the natural age of menopause,42 particularly if their breast tissue has been removed.

Salpingectomy as an alternative. In an attempt to reduce these adverse effects of early menopause, and because a large proportion of high-grade serous tumors originate in the fallopian tube,43 interest has increased in the use of risk-reducing salpingectomy (removal of fallopian tubes) and delayed oophorectomy in women at high risk of ovarian cancer.42 Studies have shown this may be a cost-effective approach and an acceptable alternative in BRCA mutation carriers who are unwilling to undergo RRSO.44,45 A clinical trial investigating this approach in women with BRCA mutations is currently underway in the United States.46 Many centers offer salpingectomy to high-risk patients < 40 years old, understanding that ovary removal is an eventuality for these patients.

When oral contraceptive pills might be beneficial. In younger women with BRCA mutations, there may also be a role for oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) as a risk-reducing strategy. Meta-analyses have shown an approximately 50% reduction in the risk of ovarian cancer among women with BRCA mutations who use OCPs.47-49

ACOG advises that it is appropriate for women with BRCA mutations to use oral contraceptives if indicated (for pregnancy prevention or menstrual cycle regulation), and that it is reasonable to use them for cancer prevention.26 NCCN does not make a formal recommendation, although it does state OCPs may reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in women with a BRCA mutation.36 Case-control studies have produced conflicting data on the association between OCP use and breast cancer risk in BRCA mutation carriers,50-53 although 2 meta-analyses found no significant association in this population.47,48

Decision aids for women with BRCA mutations

Decision aids are visual displays of risk that help patients work through complex decisions. Most decision aids are in print or digital format and include information about the decision to be made as well as pictorial examples of possible outcomes. Pictographs are especially helpful in communicating information. Some decision aids for women with BRCA mutations can be complicated with multiple outcomes (ie, breast cancer and ovarian cancer) and multiple potential interventions (risk-reducing surgery, enhanced screening options).54

Continue to: A Cochrane review...

A Cochrane review found that decision aids increased patients’ knowledge, helped patients clarify their values, and may improve value-concordant decisions.55 Two papers describing the use of decision aids for women with BRCA mutations56,57 documented decreased decisional conflict and increased satisfaction.

CASE

Ms. T underwent the recommended mammogram and MRI screening for breast cancer, as well as testing with serum CA-125 and ultrasound examinations for ovarian cancer. Her initial mammogram and MRI revealed early stage, triple-negative right breast cancer. She chose to undergo bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction. She has now completed treatment and continues to work closely with her oncology team for appropriate breast follow-up.

One year after her initial diagnosis, at the age of 35, she returned to discuss fertility. She was recently married, and she and her husband wanted to start having children. She was concerned about a safe timeline for her to pursue pregnancy, saying she felt “like a ticking time-bomb” given her prior cancer and carrier status. She wanted to discuss the risks and benefits of pregnancy and when she should consider prophylactic oophorectomy. She had a few options. She could have a baby and then undergo an RRSO, or she could talk to her gynecologist about having a salpingectomy to reduce her risk now and use assisted reproductive technology to get pregnant. She could also freeze eggs or embryos, have an RRSO, and then use a surrogate to get pregnant. We informed her that pregnancy would not affect her risk of ovarian cancer and discussed the options for pre-implantation genetic testing to assure that her children would not carry the genetic mutation.58

We provided Ms. T and her husband with a decision aid to help them navigate the decision. They are currently evaluating the options and said they would let us know when they made a decision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, Northeast Family Medicine Center, 3209 Dryden Drive, Madison, WI, 53704; sbschrag@wisc.edu.

1. Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941-1953.

2. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016. Cancer of the female breast. [Table 4.1] National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2016/results_merged/sect_04_breast.pdf. Accessed May 27, 2020.

3. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016. Cancer of the ovary. [Table 21.10] National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2016/results_merged/sect_21_ovary.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2020.

4. Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis C, et al. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:284-296.

5. Narod SA, Foulkes WD. BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:665-676.

6. Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Betts JA, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer. 2005;104:2807-2816.

7. Tai YC, Domchek S, Parmigiani G, et al. Breast cancer risk among male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1811-1814.

8. Evans DG, Susnerwala I, Dawson J, et al. Risk of breast cancer in male BRCA2 carriers. J Med Genet. 2010;47:710-711.

9. CDC. Jewish women and BRCA gene mutations. www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/young_women/bringyourbrave/hereditary_breast_cancer/jewish_women_brca.htm. Accessed May 22, 2020.

10. Rebbeck TR, Friebel TM, Friedman E, et al. Mutational spectrum in a worldwide study of 29,700 families with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2018;39:593-620.

11. Anders CK, Hsu DS, Broadwater G, et al. Young age at diagnosis correlates with worse prognosis and defines a subset of breast cancers with shared patterns of gene expression. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3324–3330.

12. Wang YA, Jian JW, Hung CF, et al. Germline breast cancer susceptibility gene mutations and breast cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:315.

13. Baretta Z, Mocellin S, Goldin E, et al. Effect of BRCA germline mutations on breast cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2016;95:e4975.

14. Lakhani SR, Manek S, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Pathology of ovarian cancers in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2473-2481.

15. Kurian AW. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations across race and ethnicity: distribution and clinical implications. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:72-78.

16. Rebbeck TR, Kauff ND, Domchek SM. Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:80-87.

17. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Int Med. 2012;27:1361-1367.

18. Ardern-Jones A, Eeles R. Developments in clinical practice: follow up clinic for BRCA mutation carriers: a case study highlighting the “virtual clinic.” Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2004;2:77-79.

19. Yerushalmi R, Rizel S, Zoref D, et al. A dedicated follow-up clinic for BRCA mutation carriers. Isr Med Assoc J. 2016;18:549-552.

20. Pichert G, Jacobs C, Jacobs I, et al. Novel one-stop multidisciplinary follow-up clinic significantly improves cancer risk management in BRCA1/2 carriers. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:313-319.

21. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:652-665.

22. Evans D, Eccles D, Rahman N, et al. A new scoring system for the chances of identifying a BRCA1/2 mutation outperforms existing models including BRCAPRO. J Med Genet. 2004;41:474-480.

23. Bellcross CA, Lemke AA, Pape LS, et al. Evaluation of a breast/ovarian cancer genetics referral screening tool in a mammography population. Genet Med. 2009;11:783-789.

24. Hoskins KF, Zwaagstra A, Ranz M. Validation of a tool for identifying women at high risk for hereditary breast cancer in population based screening. Cancer. 2006;107:1769-1776.

25. Gilpin CA, Carson N, Hunter AG. A preliminary validation of a family history assessment form to select women at risk for breast or ovarian cancer for referral to a genetics center. Clin Genet. 2000;58:299-308.

26. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 182: Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e110-e126.

27. Paluch-Shimon S, Cardoso F, Sessa C, et al. Prevention and screening in BRCA mutation carriers and other breast/ovarian hereditary cancer syndromes: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for cancer prevention and screening. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v103-v110.

28. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian. 2019. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. www2.tri-kobe.org/nccn/guideline/gynecological/english/genetic_familial.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2020.

29. Phillips KA, Milne RL, Rookus MA, et al. Tamoxifen and risk of contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3091-3099.

30. Foulkes WD, Goffin J, Brunet JS, et al. Tamoxifen may be an effective adjuvant treatment for BRCA1-related breast cancer irrespective of estrogen receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1504-1506.

31. Gronwald J, Tung N, Foulkes WD, et al. Tamoxifen and contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers: an update. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2281-2284.

32. Ludwig KK, Neuner J, Butler A, et al. Risk reduction and survival benefit of prophylactic surgery in BRCA mutation carriers, a systematic review. Am J Surgery. 2016;212:660-669.

33. Bougie O, Weberpals JI. Clinical considerations of BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutation carriers: a review. Int J Surg Oncol. 2011;2011:374012.

34. Rosenthal AN, Fraser LSM, Philpott S, et al. Evidence of stage shift in women diagnosed with ovarian cancer during phase II of the United Kingdom Familial Ovarian Cancer Screening Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1411-1420.

35. Skates SJ, Greene MH, Buys SS, et al. Early detection of ovarian cancer using the Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm with frequent CA125 testing in women at increased familial risk—combined results from two screening trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3628-3637.

36. Daly MB, Pilarski R, Berry M, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian, version 2.2017. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:9-20.

37. Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Screening for ovarian cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:588-594.

38. Marchetti C, De Felice F, Palaia I, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy: a meta-analysis on impact on ovarian cancer risk and all cause mortality in BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutation carriers. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:150.

39. Nelson HD, Pappas M, Zakher B, et al. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: a systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:255-266.

40. Parker WH, Feskanich D, Broder MS, et al. Long-term mortality associated with oophorectomy compared with ovarian conservation in the nurses’ health study. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:709-716.

41. Faubion SS, Kuhle CL, Shuster LT, et al. Long-term health consequences of premature or early menopause and considerations for management. Climacteric. 2015;18:483-491.

42. Menon U, Karpinskyj C, Gentry-Maharaj A. Ovarian cancer prevention and screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:909-927.

43. Crum CP, Drapkin R, Miron A, et al. The distal fallopian tube: a new model for pelvic serous carcinogenesis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:3-9.

44. Kwon JS, Tinker A, Pansegrau G, et al. Prophylactic salpingectomy and delayed oophorectomy as an alternative for BRCA mutation carriers. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:14-24.

45. Holman LL, Friedman S, Daniels MS, et al. Acceptability of prophylactic salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy as risk-reducing surgery among BRCA mutation carriers. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:283-286.

46. MD Anderson Cancer Center. Prophylactic salpingectomy with delayed oophorectomy, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, and ovarian cancer screening among BRCA mutation carriers: a proof-of-concept study. www.mdanderson.org/patients-family/diagnosis-treatment/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-index/clinical-trials-detail.ID2013-0340.html. Accessed May 22, 2020.

47. Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2275-2284.

48. Moorman PG, Havrilesky LJ, Gierisch JM, et al. Oral contraceptives and risk of ovarian cancer and breast cancer among high-risk women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4188-4198.

49. Friebel TM, Domchek SM, Rebbeck TR. Modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju091.

50. Haile RW, Thomas DC, McGuire V, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, oral contraceptive use, and breast cancer before age 50. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1863-1870.

51. Lee E, Ma H, McKean-Cowdin R, et al. Effect of reproductive factors and oral contraceptives on breast cancer risk in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers and noncarriers: results from a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3170-3178.

52. Narod SA, Dubé MP, Klijn J, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1773-1779.

53. Milne RL, Knight JA, John EM, et al. Oral contraceptive use and risk of early-onset breast cancer in carriers and noncarriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:350-356.

54. Culver JO, MacDonald DJ, Thornton AA, et al. Development and evaluation of a decision aid for BRCA carriers with breast cancer. J Genet Couns. 2011;20:294-307.

55. Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431.

56. Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, DeMarco TA, et al. Randomized trial of a decision aid for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: impact on measures of decision making and satisfaction. Health Psychol. 2009;28:11-19.

57. Metcalfe KA, Dennis CL, Poll A, et al. Effect of decision aid for breast cancer prevention on decisional conflict in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: a multisite, randomized, controlled trial. Gen Med. 2017;19:330-336.

58. Friedman LC, Kramer RM. Reproductive issues for women with BRCA mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;34:83-86.

CASE

Sara T* recently moved back to the area to be closer to her family. The 34-year-old patient visited our office to discuss the benefits and potential risks of genetic counseling. She explained that her aunt had just died at age 64 of ovarian cancer. Also, her maternal cousin had been diagnosed at age 42 with breast cancer, and her maternal grandmother had died at age 45 of an unknown “female cancer.” She was scared to find out if she had high-risk genes because she felt it would change her life forever. However, if she ignored the issue, she thought she might worry too much.

We discussed the implications of a positive result, such as having to live with the knowledge and to make decisions about potential screening and risk-reducing surgery. On the other hand, not knowing could allow for the undetected growth of cancer that might otherwise be mitigated to some degree if she knew her risk status and pursued an aggressive screening program.

We worked with Ms. T to map out her next steps.

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women worldwide, representing nearly one-quarter of all female cancer diagnoses in 2018.1 It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in women in developed nations and the leading cause of cancer death in women in developing nations.1 In the United States, 1 in 8 women will develop breast cancer in her lifetime.2 By comparison, the rate of ovarian cancer is much lower, with a lifetime prevalence of 1 in 70 to 80 women.3,4 Although ovarian cancer is less common than breast cancer, its associated mortality is high, and most cases are discovered at advanced stages.

The outsized threat of BRCA mutations. It is estimated that 5% to 10% of all breast cancers are hereditary, with 80% of these attributable to BRCA1 (45%) and BRCA2 (35%).5 These autosomal dominant mutations occur at the germline level, within the egg or sperm, and are therefore incorporated into the DNA of every cell and passed from one generation to the next. Families with BRCA mutations have much higher lifetime rates of cancer. The lifetime risk of breast cancer due to BRCA mutations is estimated at > 80% (BRCA1) and 45% (BRCA2).5BRCA mutations account for between

Male BRCA carriers have a lifetime breast cancer risk of 1% to 5% with BRCA1 and 5% to 10% with BRCA2,7,8 compared with about 1:1000 lifetime incidence in the unselected male population. Male carriers are also at risk for more aggressive prostate cancers.7,8

Continue to: Certain populatiosn carry undue burden of BRCA-related disease

Certain populations carry undue burden of BRCA-related disease due to specific founder mutations. While the estimated global prevalence of BRCA mutations is 0.2% to 1%, for those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent the range is 2% to 3%, representing a relative risk up to 15 times that of the general population.9 Hispanic Americans also appear to have higher rates of BRCA-related cancers.10 Ongoing genetics research continues to identify founder mutations worldwide,10 which may inform future screening guidelines.

In addition to BRCA mutations, there are other, less common mutations (TABLE 15) known to cause hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

Identifying BRCA genes enables treatment planning. Compared with sporadic cancers, BRCA-related breast cancers

Similarly, BRCA-related ovarian cancer is more likely to be high-grade and endometrioid or serous subtype.14

Shared decision-making helps give clarity to the way forward

Shared decision-making is a process of communication whereby the clinician and the patient identify a decision to be made, review data relevant to clinical options, discuss patient perspectives and preferences regarding each option, and arrive at the decision together.17 Shared decision-making is important when treating women with BRCA mutations because there is no single correct plan. Individual values and competing medical issues may strongly guide each woman’s decisions about screening and cancer prevention treatment decisions.

Continue to: Shared decision-making in this situation...

Shared decision-making in this situation is a strategy to use the evidence of risk along with patient preferences around fertility issues to help come to a decision that is the right one for the patient. Primary care clinicians aware of the general risks and benefits of each available option can refer women at high risk for breast or ovarian cancer to a specialist multidisciplinary clinic that can provide tailored risk assessment and risk reduction counseling as needed.18-20

Genetic screening recommendations

Screening is recommended for women who have any 1 of several family risk factors (TABLE 221). A number of risk assessment tools are available for primary care clinicians to determine which patients are at high enough risk for a hereditary breast or ovarian cancer to warrant referral to a genetic counselor.22-25 If screening suggests high risk, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends (Grade B) referral for genetic counseling.21

Explain to patients who are candidates for further investigation that a genetic counselor will review their family history and recommend testing for the specific mutations that increase cancer risk. Discuss potential benefits and harms of genetic testing. A benefit of genetic testing is that aggressive screening may suggest preventive procedures to reduce the risk of future cancer. Most tests come back definitively positive or negative, but an indeterminate result may cause harm. A small minority of results may indicate a genetic variant of unknown significance. The ramifications of this variant may not be known. Some women will experience anxiety about nonspecific test results and will be afraid to share them with family members. There is also some concern about privacy issues, potential insurance bias, and coverage of any preventive strategies.26

CASE

Based on Ms. T’s family history and her desire to know more, we referred her to a genetic counselor and she decided to undergo genetic testing. She screened positive for BRCA1. Ms. T was in a serious relationship and thought she would like to have children at some point. She returned to our office after receiving the positive genetic test results, wondering about screening for breast and ovarian cancer.

Breast cancer screening and risk-reduction strategies

Screening. Because the risk of breast cancer is high in women with BRCA mutations, and because cancer in these women is more likely to be advanced at diagnosis, starting a screening program at an early age is prudent. Observational studies suggest that breastfeeding reduces the risk of breast and ovarian cancer in women with BRCA mutations, as it does for women in the general population.27 Women should return for a clinical breast exam every 6 to 12 months starting at age 25; they should start radiologic screening with magnetic resonance imaging at age 25 and mammography at age 30 (TABLE 327,28).

Continue to: Risk-reduction strategies

Risk-reduction strategies. There is weak evidence to support the use of tamoxifen or other synthetic estrogen reuptake modulators (SERMs) to reduce breast cancer risk in women with BRCA mutations. Many of these cancers do not express estrogen receptors, which may explain the lack of efficacy in certain cases. Several observational studies have shown that tamoxifen can reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations who have already been diagnosed with cancer in the other breast.29-31 However, tamoxifen does not reduce a patient’s risk of ovarian cancer, and it may increase her risk of uterine cancer.

Prophylactic bilateral mastectomy is the mainstay of breast cancer prevention in this population. Data from a systematic review suggest that this surgery may prevent the incidence of breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations by 90% to 95%.32 However, this review did not demonstrate a reduction in mortality from breast cancer, likely due to poor data quality.32 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends discussing prophylactic mastectomy with all women who have BRCA mutations.28 Further conversations are important to review the risk of tissue left behind and quality-of-life issues, including the inability to breastfeed if the woman wants more children and the cosmetic changes with reconstruction.

Ovarian cancer screening and risk-reduction strategies

Screening. No effective screening strategy has been endorsed for ovarian cancer, as most previous studies have shown screening to be ineffective.26,33 Recently, studies both in the United Kingdom and the United States have investigated a screening strategy using the risk-of-ovarian-cancer algorithm (ROCA), which calculates an individual’s risk based on serum levels of cancer antigen 125 (CA-125).34,35 These studies measured CA-125 levels every 3 to 4 months followed by transvaginal ultrasound if CA-125 increased substantially (as determined by ROCA). Absent an abnormal increase in CA-125, transvaginal ultrasound was performed annually. These screening strategies showed improved specificity over annual screening programs, and the cancers detected were more likely to be diagnosed at an early stage (stage II vs stage III) and had higher rates of zero residual disease after surgery compared with those detected 1 year after screening ended.34,35 However, survival data are not yet available. More research is needed to determine if more frequent screening approaches could improve survival in high-risk women.

NCCN and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) do not endorse routine screening with transvaginal ultrasound and serum CA-125 for high-risk women, as the benefits are uncertain. However, they do advise that these screens may be considered as a short-term strategy for women ages 30 to 35 who defer risk-reducing surgery.26,36 The USPSTF does not make a recommendation regarding ovarian cancer screening in high-risk women.37

Risk-reduction strategies. Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) is the only recommended technique for reducing the risk of ovarian cancer in women at high risk.26,33,36 Meta-analyses have shown an 80% reduction in ovarian cancer risk16 and 68% reduction in all-cause mortality with this approach.38 The NCCN recommends RRSO for women with a known BRCA1 mutation between the ages of 35 and 40 who have completed childbearing.36 Since the onset of ovarian cancer tends to be later in women with BRCA2 mutations, it is reasonable to delay RRSO until age 40 to 45 in this population if they have taken other steps to maximize breast cancer prevention (ie, bilateral mastectomy).36

Continue to: Adverse effects of RRSO...

Adverse effects of RRSO include surgery complications (wound infection, small bowel obstruction, bladder perforation) and effects of early menopause (vasomotor symptoms, decreased sexual functioning, and increased risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality).39-41 In the absence of contraindications, ACOG recommends using hormone therapy in women undergoing RRSO until the natural age of menopause,42 particularly if their breast tissue has been removed.

Salpingectomy as an alternative. In an attempt to reduce these adverse effects of early menopause, and because a large proportion of high-grade serous tumors originate in the fallopian tube,43 interest has increased in the use of risk-reducing salpingectomy (removal of fallopian tubes) and delayed oophorectomy in women at high risk of ovarian cancer.42 Studies have shown this may be a cost-effective approach and an acceptable alternative in BRCA mutation carriers who are unwilling to undergo RRSO.44,45 A clinical trial investigating this approach in women with BRCA mutations is currently underway in the United States.46 Many centers offer salpingectomy to high-risk patients < 40 years old, understanding that ovary removal is an eventuality for these patients.

When oral contraceptive pills might be beneficial. In younger women with BRCA mutations, there may also be a role for oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) as a risk-reducing strategy. Meta-analyses have shown an approximately 50% reduction in the risk of ovarian cancer among women with BRCA mutations who use OCPs.47-49

ACOG advises that it is appropriate for women with BRCA mutations to use oral contraceptives if indicated (for pregnancy prevention or menstrual cycle regulation), and that it is reasonable to use them for cancer prevention.26 NCCN does not make a formal recommendation, although it does state OCPs may reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in women with a BRCA mutation.36 Case-control studies have produced conflicting data on the association between OCP use and breast cancer risk in BRCA mutation carriers,50-53 although 2 meta-analyses found no significant association in this population.47,48

Decision aids for women with BRCA mutations

Decision aids are visual displays of risk that help patients work through complex decisions. Most decision aids are in print or digital format and include information about the decision to be made as well as pictorial examples of possible outcomes. Pictographs are especially helpful in communicating information. Some decision aids for women with BRCA mutations can be complicated with multiple outcomes (ie, breast cancer and ovarian cancer) and multiple potential interventions (risk-reducing surgery, enhanced screening options).54

Continue to: A Cochrane review...

A Cochrane review found that decision aids increased patients’ knowledge, helped patients clarify their values, and may improve value-concordant decisions.55 Two papers describing the use of decision aids for women with BRCA mutations56,57 documented decreased decisional conflict and increased satisfaction.

CASE

Ms. T underwent the recommended mammogram and MRI screening for breast cancer, as well as testing with serum CA-125 and ultrasound examinations for ovarian cancer. Her initial mammogram and MRI revealed early stage, triple-negative right breast cancer. She chose to undergo bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction. She has now completed treatment and continues to work closely with her oncology team for appropriate breast follow-up.

One year after her initial diagnosis, at the age of 35, she returned to discuss fertility. She was recently married, and she and her husband wanted to start having children. She was concerned about a safe timeline for her to pursue pregnancy, saying she felt “like a ticking time-bomb” given her prior cancer and carrier status. She wanted to discuss the risks and benefits of pregnancy and when she should consider prophylactic oophorectomy. She had a few options. She could have a baby and then undergo an RRSO, or she could talk to her gynecologist about having a salpingectomy to reduce her risk now and use assisted reproductive technology to get pregnant. She could also freeze eggs or embryos, have an RRSO, and then use a surrogate to get pregnant. We informed her that pregnancy would not affect her risk of ovarian cancer and discussed the options for pre-implantation genetic testing to assure that her children would not carry the genetic mutation.58

We provided Ms. T and her husband with a decision aid to help them navigate the decision. They are currently evaluating the options and said they would let us know when they made a decision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarina Schrager, MD, MS, Northeast Family Medicine Center, 3209 Dryden Drive, Madison, WI, 53704; sbschrag@wisc.edu.

CASE

Sara T* recently moved back to the area to be closer to her family. The 34-year-old patient visited our office to discuss the benefits and potential risks of genetic counseling. She explained that her aunt had just died at age 64 of ovarian cancer. Also, her maternal cousin had been diagnosed at age 42 with breast cancer, and her maternal grandmother had died at age 45 of an unknown “female cancer.” She was scared to find out if she had high-risk genes because she felt it would change her life forever. However, if she ignored the issue, she thought she might worry too much.

We discussed the implications of a positive result, such as having to live with the knowledge and to make decisions about potential screening and risk-reducing surgery. On the other hand, not knowing could allow for the undetected growth of cancer that might otherwise be mitigated to some degree if she knew her risk status and pursued an aggressive screening program.

We worked with Ms. T to map out her next steps.

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women worldwide, representing nearly one-quarter of all female cancer diagnoses in 2018.1 It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in women in developed nations and the leading cause of cancer death in women in developing nations.1 In the United States, 1 in 8 women will develop breast cancer in her lifetime.2 By comparison, the rate of ovarian cancer is much lower, with a lifetime prevalence of 1 in 70 to 80 women.3,4 Although ovarian cancer is less common than breast cancer, its associated mortality is high, and most cases are discovered at advanced stages.

The outsized threat of BRCA mutations. It is estimated that 5% to 10% of all breast cancers are hereditary, with 80% of these attributable to BRCA1 (45%) and BRCA2 (35%).5 These autosomal dominant mutations occur at the germline level, within the egg or sperm, and are therefore incorporated into the DNA of every cell and passed from one generation to the next. Families with BRCA mutations have much higher lifetime rates of cancer. The lifetime risk of breast cancer due to BRCA mutations is estimated at > 80% (BRCA1) and 45% (BRCA2).5BRCA mutations account for between

Male BRCA carriers have a lifetime breast cancer risk of 1% to 5% with BRCA1 and 5% to 10% with BRCA2,7,8 compared with about 1:1000 lifetime incidence in the unselected male population. Male carriers are also at risk for more aggressive prostate cancers.7,8

Continue to: Certain populatiosn carry undue burden of BRCA-related disease

Certain populations carry undue burden of BRCA-related disease due to specific founder mutations. While the estimated global prevalence of BRCA mutations is 0.2% to 1%, for those of Ashkenazi Jewish descent the range is 2% to 3%, representing a relative risk up to 15 times that of the general population.9 Hispanic Americans also appear to have higher rates of BRCA-related cancers.10 Ongoing genetics research continues to identify founder mutations worldwide,10 which may inform future screening guidelines.

In addition to BRCA mutations, there are other, less common mutations (TABLE 15) known to cause hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

Identifying BRCA genes enables treatment planning. Compared with sporadic cancers, BRCA-related breast cancers

Similarly, BRCA-related ovarian cancer is more likely to be high-grade and endometrioid or serous subtype.14

Shared decision-making helps give clarity to the way forward

Shared decision-making is a process of communication whereby the clinician and the patient identify a decision to be made, review data relevant to clinical options, discuss patient perspectives and preferences regarding each option, and arrive at the decision together.17 Shared decision-making is important when treating women with BRCA mutations because there is no single correct plan. Individual values and competing medical issues may strongly guide each woman’s decisions about screening and cancer prevention treatment decisions.

Continue to: Shared decision-making in this situation...

Shared decision-making in this situation is a strategy to use the evidence of risk along with patient preferences around fertility issues to help come to a decision that is the right one for the patient. Primary care clinicians aware of the general risks and benefits of each available option can refer women at high risk for breast or ovarian cancer to a specialist multidisciplinary clinic that can provide tailored risk assessment and risk reduction counseling as needed.18-20

Genetic screening recommendations

Screening is recommended for women who have any 1 of several family risk factors (TABLE 221). A number of risk assessment tools are available for primary care clinicians to determine which patients are at high enough risk for a hereditary breast or ovarian cancer to warrant referral to a genetic counselor.22-25 If screening suggests high risk, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends (Grade B) referral for genetic counseling.21

Explain to patients who are candidates for further investigation that a genetic counselor will review their family history and recommend testing for the specific mutations that increase cancer risk. Discuss potential benefits and harms of genetic testing. A benefit of genetic testing is that aggressive screening may suggest preventive procedures to reduce the risk of future cancer. Most tests come back definitively positive or negative, but an indeterminate result may cause harm. A small minority of results may indicate a genetic variant of unknown significance. The ramifications of this variant may not be known. Some women will experience anxiety about nonspecific test results and will be afraid to share them with family members. There is also some concern about privacy issues, potential insurance bias, and coverage of any preventive strategies.26

CASE

Based on Ms. T’s family history and her desire to know more, we referred her to a genetic counselor and she decided to undergo genetic testing. She screened positive for BRCA1. Ms. T was in a serious relationship and thought she would like to have children at some point. She returned to our office after receiving the positive genetic test results, wondering about screening for breast and ovarian cancer.

Breast cancer screening and risk-reduction strategies

Screening. Because the risk of breast cancer is high in women with BRCA mutations, and because cancer in these women is more likely to be advanced at diagnosis, starting a screening program at an early age is prudent. Observational studies suggest that breastfeeding reduces the risk of breast and ovarian cancer in women with BRCA mutations, as it does for women in the general population.27 Women should return for a clinical breast exam every 6 to 12 months starting at age 25; they should start radiologic screening with magnetic resonance imaging at age 25 and mammography at age 30 (TABLE 327,28).

Continue to: Risk-reduction strategies

Risk-reduction strategies. There is weak evidence to support the use of tamoxifen or other synthetic estrogen reuptake modulators (SERMs) to reduce breast cancer risk in women with BRCA mutations. Many of these cancers do not express estrogen receptors, which may explain the lack of efficacy in certain cases. Several observational studies have shown that tamoxifen can reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations who have already been diagnosed with cancer in the other breast.29-31 However, tamoxifen does not reduce a patient’s risk of ovarian cancer, and it may increase her risk of uterine cancer.

Prophylactic bilateral mastectomy is the mainstay of breast cancer prevention in this population. Data from a systematic review suggest that this surgery may prevent the incidence of breast cancer in women with BRCA mutations by 90% to 95%.32 However, this review did not demonstrate a reduction in mortality from breast cancer, likely due to poor data quality.32 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends discussing prophylactic mastectomy with all women who have BRCA mutations.28 Further conversations are important to review the risk of tissue left behind and quality-of-life issues, including the inability to breastfeed if the woman wants more children and the cosmetic changes with reconstruction.

Ovarian cancer screening and risk-reduction strategies