User login

Female Runner, 47, with Inguinal Lump

A 47-year-old woman was referred to the gynecology office by her primary care NP for surgical excision of an enlarging nodule on the right side of her mons pubis. Onset occurred about 6 months earlier. The patient reported that symptoms waxed and waned but had worsened progressively over the past 2 to 3 months, adding that the nodule hurt only occasionally. She noted that symptoms were exacerbated by exercise, specifically running. Further questioning prompted the observation that her symptoms were more noticeable at the time of menses.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable, with no chronic conditions; her surgical history consisted of a wisdom tooth extraction. She had no known drug allergies. Her family history included cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, and arthritis. Reproductive history revealed that she was G1 P1, with a 38-week uncomplicated vaginal delivery. She experienced menarche at age 14, and her menses was regular at every 28 days. For the past 5 days, there had been no dysmenorrhea. The patient was married, exercised regularly, and did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

On examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 123/73 mm Hg; heart rate, 77 beats/min; respiratory rate, 12 breaths/min; weight, 128 lb; height, 5 ft 7 in; O2 saturation, 99% on room air; and BMI, 20. The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was thin, appeared physically fit, and exhibited no signs of distress. Her physical exam was unremarkable, apart from a firm, minimally tender, well-circumscribed, 3.5 × 3.5–cm nodule right of midline on the mons pubis.

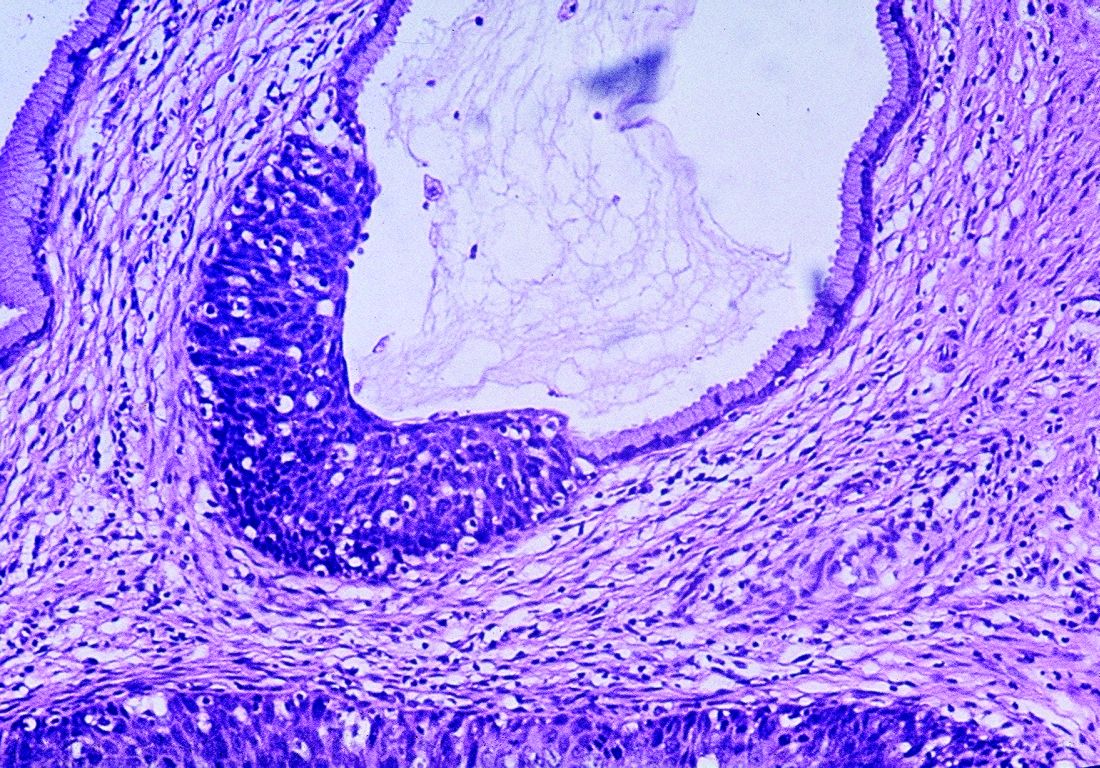

The patient was scheduled for outpatient surgical excision of a benign skin lesion (excluding skin tags) of the genitalia, 3.1 to 3.5 cm (CPT code 11424). During this procedure, it became evident that this was not a lipoma. The lesion was exceptionally hard, and it was difficult to discern if it was incorporated into the rectus abdominis near the point of attachment to the pubic symphysis. The lesion was unintentionally disrupted, revealing black powdery material within the capsule. The tissue was sent for a fast, frozen section that showed “soft tissue with extensive involvement by endometriosis.” The pathology report noted “[m]any endometrial glands in a background of stromal tissue. Necrosis was not a feature. No evidence of atypia.” The patient’s postoperative diagnosis was endometriosis.

DISCUSSION

Endometriosis occurs when endometrial or “endometrial-like” tissue is displaced to sites other than within the uterus. It is most frequently found on tissues close to the uterus, such as the ovaries or pelvic peritoneum. Estrogen is the driving force that feeds the endometrium, causing it to proliferate, whether inside or outside the uterus. Given this dependence on hormones, endometriosis occurs most often during a woman’s fertile years, although it can occur after menopause. Endometriosis is common, affecting at least 10% of premenopausal women; moreover, it is identified as the cause in 70% of all female chronic pelvic pain cases.1-4

Endometriosis has certain identifiable features, such as chronic pain, dyspareunia, infertility, and menstrual and gastrointestinal symptoms. However, it is seldom diagnosed quickly; studies indicate that diagnosis can be delayed by 5 to 10 years after a patient has first sought treatment for symptoms.2,4 Multiple factors contribute to a lag in diagnosis: Presentation is not always straightforward. There are no definitive lab values or biomarkers. Symptoms vary from patient to patient, as do clinical skills from one diagnostician to another.1

Unlike pelvic endometriosis, inguinal endometriosis is not common; disease in this location encompasses only 0.3% to 0.6% of all diagnosed cases.3,5-7 Since the discovery of the first known case of round ligament endometriosis in 1896, there have been only 70 cases reported in the medical literature.6,7

If the more common form of endometriosis is frequently missed, this rarely seen variant presents an even greater diagnostic challenge. The typical presentation of inguinal endometriosis includes a firm nodule in the groin, accompanied by tenderness and swelling. A careful history will allude to pain that occurs cyclically with menses.

Cause

Among several theories about the etiology of endometriosis, the most popular has been retrograde menstruation.1,4,5 According to this hypothesis, the flow of menstrual blood moves backward through the fallopian tubes, spilling into the pelvic cavity and carrying endometrial tissue with it. One theory purports that endometrial tissue is transplanted from the uterus to other areas of the body via the bloodstream or the lymphatics, much like a metastatic disease.1,4 Another theory states that cells outside the uterus, which line the peritoneum, transform into endometrial cells through metaplasia.4,5 Endometrial tissue can also be transplanted iatrogenically during surgery—for example, when endometrial tissue is displaced during a cesarean delivery, resulting in implants above the fascia and below the subcutaneous layers. Several other hypotheses concern stem-cell involvement, hormonal factors, immune system dysfunction, and genetics.4,5 Currently, there are no definitive answers.

Location

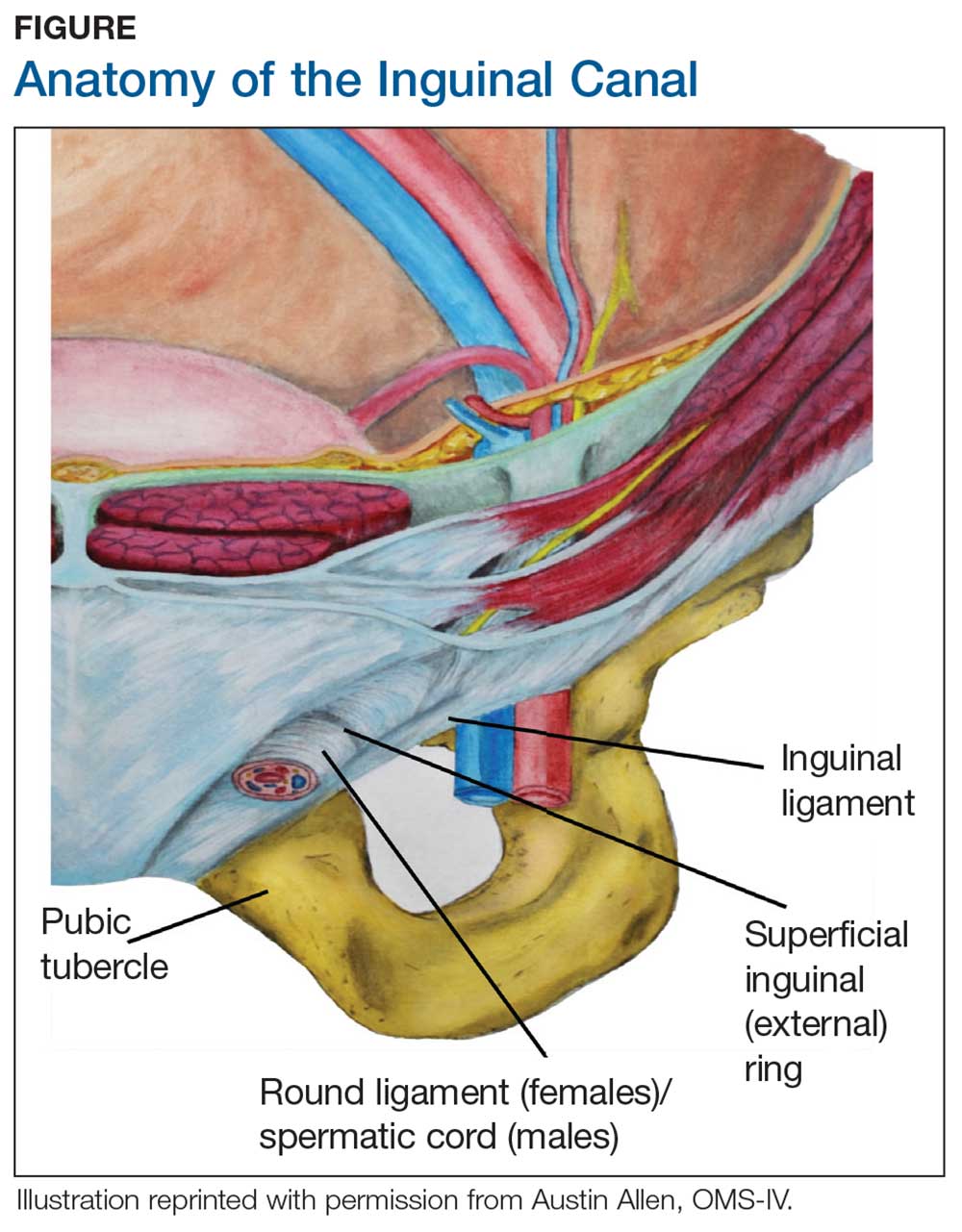

During maturation, the parietal peritoneum develops a pouch called the processus vaginalis, which serves as a passageway for the gubernaculum to transport the round ligament running from the uterus, through the inguinal canal, and ending at the labia. After these structures reach their destination, in normal development, the processus vaginalis degenerates, closing the inguinal canal. Occasionally the processus vaginalis fails to close, allowing for a communication pathway between the peritoneal cavity and the inguinal canal. This leaves the canal vulnerable to the contents of the pelvic cavity, such as a hernia or hydrocele, and provides a clear path for endometriosis.5-7 The implant found in the case patient was at the point where the external ring lies, just above the right pubic tubercle (see Figure 1).

Endometriosis implants can occur anywhere along the round ligament in either the intrapelvic or extrapelvic segments. Implants have also been found in the wall of a hernia sac, the wall of a Nuck canal hydrocele, or even in the subcutaneous tissue surrounding the inguinal canal.3 Interestingly, inguinal endometriosis occurs more often in the right side (up to 94% of cases) than in the left side, as was the case with our patient.5-7 The reason for this predominance has not been established, although there are several theories, including one that suggests the left side is afforded protection by the sigmoid colon.5-7

Laboratory diagnosis

Imaging, such as ultrasound and MRI, offers some diagnostic benefit, although its usefulness is most often realized in the pelvis. Pelvic ultrasound can be used to identify ovarian endometriomas.1 MRI can help rule out, locate, or sometimes determine the degree of deep infiltrating endometriosis, which is an indispensable tool for surgical planning.5,7 Unfortunately, the diagnostic accuracy for extra-pelvic lesions is variable; neither modality is particularly useful in identifying superficial lesions, which comprises most cases.

Ultrasound of the groin can be employed to evaluate for hernia; if a hernia has been excluded, histologic confirmation can be obtained via fine-needle aspiration of nodule contents.5,7 One caveat is that these tests are helpful only if the clinician suspects the diagnosis and orders them. The definitive diagnostic test remains direct visualization, which requires laparoscopy.1,5

Differential diagnosis

Lipoma was a favored diagnosis in this case because of the palpable, well-circumscribed borders, nontender on exam; intermittent, minimal tenderness; and no evidence of erythema or color change. A second possibility was an enlarged lymph node, which was less likely due to the location, large size, and sudden onset without any accompanying symptoms of infection or chronic illness. Finally, an inguinal hernia was least likely, again because of well-defined borders, no history of a lump in the area, a nodule that was not reducible, only minimal tenderness, and no color changes on the skin.

Management

Definitive treatment for inguinal endometriosis entails complete surgical excision.5-7 The provider should be prepared to repair a defect after the excision; there is potential for a substantial defect that might require mesh. Additionally, a herniorrhaphy may be indicated if there is a coexisting hernia.5 The risk for recurrent disease in the inguinal canal after treatment is uncommon, unless the excision was not complete.3

There is an association between inguinal and pelvic endometriosis but not a direct correlation. Data on concomitant pelvic and inguinal endometriosis have been variable. In one case series of 9 patients diagnosed with inguinal endometriosis, none had a history of pelvic endometriosis, and only 1 was subsequently diagnosed with pelvic endometriosis.7 An increased association was noted for patients with implants found on the proximal segment of the round ligament.7 However, implants on the extrapelvic segment were not likely to represent pelvic disease but rather isolated lesions in the canal.7 For those with pelvic endometriosis, complications and recurrence are likely, resulting in the need for long-term treatment.

There is some debate in the literature whether to proceed with laparoscopy once inguinal endometriosis has been identified. Diagnostic laparoscopy to evaluate the pelvis is indicated for symptomatic patients or for cases in which an indirect inguinal hernia is suspected.5 Laparoscopy can offer the benefit of both a diagnostic tool and a mechanism for treatment. However, this is an invasive procedure that also incurs risks. The medical provider, in discussion with the patient, must weigh the risks against the benefits of an invasive procedure before determining how to proceed.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

The lesion was excised completely. Since the patient had been entirely asymptomatic until age 47, and the risks of a potentially unnecessary surgery outweighed the theoretical benefits, the decision was made not to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy to investigate for pelvic endometriosis. The patient made a complete and uneventful recovery. No further treatment was initiated. She continues to be asymptomatic, denying any menstrual complaints, dyspareunia, or further problems with the groin.

CONCLUSION

This case describes a satellite lesion of endometrial tissue found in an unusual location, in a patient with no history, no risk factors, and no symptoms. The final diagnosis had been omitted from the differential—perhaps because the patient initially associated her symptoms with exercise and mentioned the correlation to her menstrual cycle as an afterthought. Fortunately, the correct diagnosis was made and the appropriate treatment provided.

There are numerous presentations of endometriosis; extrapelvic lesions can have very different, often vague, presentations when compared to the familiar symptoms of pelvic disease. Unfortunately, diagnosis is often delayed. Obscure presentations, in unusual sites, can further impede both speed and accuracy of diagnosis. To date, there are no lab tests or biomarkers to aid diagnosis; imaging studies are inconsistent. Until more accurate diagnostic tools become available, the diagnosis remains dependent on history taking, physical exam, and the clinical judgment of the provider. The astute clinician will recognize the catamenial pattern and consider endometriosis as part of the differential.

1. Parasar P, Ozcan P, Terry KL. Endometriosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2017;6(1):34-41.

2. Soliman AM, Fuldeore M, Snabes MC. Factors associated with time to endometriosis diagnosis in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(7):788-797.

3. Niitsu H, Tsumura H, Kanehiro T, et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical treatment for inguinal endometriosis in young women of reproductive age. Dig Surg. 2019;36(2):166-172.

4. Mehedintu C, Plotogea MN, Ionescu S, Antonovici M. Endometriosis still a challenge. J Med Life. 2014;7(3):349-357.

5. Wolfhagen N, Simons NE, de Jong KH, et al. Inguinal endometriosis, a rare entity of which surgeons should be aware: clinical aspects and long-term follow-up of nine cases. Hernia. 2018;22(5):881-886.

6. Prabhu R, Krishna S, Shenoy R, Thangavelu S. Endometriosis of extra-pelvic round ligament, a diagnostic dilemma for physicians. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.

7. Pandey D, Coondoo A, Shetty J, Mathew S. Jack in the box: inguinal endometriosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015.

A 47-year-old woman was referred to the gynecology office by her primary care NP for surgical excision of an enlarging nodule on the right side of her mons pubis. Onset occurred about 6 months earlier. The patient reported that symptoms waxed and waned but had worsened progressively over the past 2 to 3 months, adding that the nodule hurt only occasionally. She noted that symptoms were exacerbated by exercise, specifically running. Further questioning prompted the observation that her symptoms were more noticeable at the time of menses.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable, with no chronic conditions; her surgical history consisted of a wisdom tooth extraction. She had no known drug allergies. Her family history included cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, and arthritis. Reproductive history revealed that she was G1 P1, with a 38-week uncomplicated vaginal delivery. She experienced menarche at age 14, and her menses was regular at every 28 days. For the past 5 days, there had been no dysmenorrhea. The patient was married, exercised regularly, and did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

On examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 123/73 mm Hg; heart rate, 77 beats/min; respiratory rate, 12 breaths/min; weight, 128 lb; height, 5 ft 7 in; O2 saturation, 99% on room air; and BMI, 20. The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was thin, appeared physically fit, and exhibited no signs of distress. Her physical exam was unremarkable, apart from a firm, minimally tender, well-circumscribed, 3.5 × 3.5–cm nodule right of midline on the mons pubis.

The patient was scheduled for outpatient surgical excision of a benign skin lesion (excluding skin tags) of the genitalia, 3.1 to 3.5 cm (CPT code 11424). During this procedure, it became evident that this was not a lipoma. The lesion was exceptionally hard, and it was difficult to discern if it was incorporated into the rectus abdominis near the point of attachment to the pubic symphysis. The lesion was unintentionally disrupted, revealing black powdery material within the capsule. The tissue was sent for a fast, frozen section that showed “soft tissue with extensive involvement by endometriosis.” The pathology report noted “[m]any endometrial glands in a background of stromal tissue. Necrosis was not a feature. No evidence of atypia.” The patient’s postoperative diagnosis was endometriosis.

DISCUSSION

Endometriosis occurs when endometrial or “endometrial-like” tissue is displaced to sites other than within the uterus. It is most frequently found on tissues close to the uterus, such as the ovaries or pelvic peritoneum. Estrogen is the driving force that feeds the endometrium, causing it to proliferate, whether inside or outside the uterus. Given this dependence on hormones, endometriosis occurs most often during a woman’s fertile years, although it can occur after menopause. Endometriosis is common, affecting at least 10% of premenopausal women; moreover, it is identified as the cause in 70% of all female chronic pelvic pain cases.1-4

Endometriosis has certain identifiable features, such as chronic pain, dyspareunia, infertility, and menstrual and gastrointestinal symptoms. However, it is seldom diagnosed quickly; studies indicate that diagnosis can be delayed by 5 to 10 years after a patient has first sought treatment for symptoms.2,4 Multiple factors contribute to a lag in diagnosis: Presentation is not always straightforward. There are no definitive lab values or biomarkers. Symptoms vary from patient to patient, as do clinical skills from one diagnostician to another.1

Unlike pelvic endometriosis, inguinal endometriosis is not common; disease in this location encompasses only 0.3% to 0.6% of all diagnosed cases.3,5-7 Since the discovery of the first known case of round ligament endometriosis in 1896, there have been only 70 cases reported in the medical literature.6,7

If the more common form of endometriosis is frequently missed, this rarely seen variant presents an even greater diagnostic challenge. The typical presentation of inguinal endometriosis includes a firm nodule in the groin, accompanied by tenderness and swelling. A careful history will allude to pain that occurs cyclically with menses.

Cause

Among several theories about the etiology of endometriosis, the most popular has been retrograde menstruation.1,4,5 According to this hypothesis, the flow of menstrual blood moves backward through the fallopian tubes, spilling into the pelvic cavity and carrying endometrial tissue with it. One theory purports that endometrial tissue is transplanted from the uterus to other areas of the body via the bloodstream or the lymphatics, much like a metastatic disease.1,4 Another theory states that cells outside the uterus, which line the peritoneum, transform into endometrial cells through metaplasia.4,5 Endometrial tissue can also be transplanted iatrogenically during surgery—for example, when endometrial tissue is displaced during a cesarean delivery, resulting in implants above the fascia and below the subcutaneous layers. Several other hypotheses concern stem-cell involvement, hormonal factors, immune system dysfunction, and genetics.4,5 Currently, there are no definitive answers.

Location

During maturation, the parietal peritoneum develops a pouch called the processus vaginalis, which serves as a passageway for the gubernaculum to transport the round ligament running from the uterus, through the inguinal canal, and ending at the labia. After these structures reach their destination, in normal development, the processus vaginalis degenerates, closing the inguinal canal. Occasionally the processus vaginalis fails to close, allowing for a communication pathway between the peritoneal cavity and the inguinal canal. This leaves the canal vulnerable to the contents of the pelvic cavity, such as a hernia or hydrocele, and provides a clear path for endometriosis.5-7 The implant found in the case patient was at the point where the external ring lies, just above the right pubic tubercle (see Figure 1).

Endometriosis implants can occur anywhere along the round ligament in either the intrapelvic or extrapelvic segments. Implants have also been found in the wall of a hernia sac, the wall of a Nuck canal hydrocele, or even in the subcutaneous tissue surrounding the inguinal canal.3 Interestingly, inguinal endometriosis occurs more often in the right side (up to 94% of cases) than in the left side, as was the case with our patient.5-7 The reason for this predominance has not been established, although there are several theories, including one that suggests the left side is afforded protection by the sigmoid colon.5-7

Laboratory diagnosis

Imaging, such as ultrasound and MRI, offers some diagnostic benefit, although its usefulness is most often realized in the pelvis. Pelvic ultrasound can be used to identify ovarian endometriomas.1 MRI can help rule out, locate, or sometimes determine the degree of deep infiltrating endometriosis, which is an indispensable tool for surgical planning.5,7 Unfortunately, the diagnostic accuracy for extra-pelvic lesions is variable; neither modality is particularly useful in identifying superficial lesions, which comprises most cases.

Ultrasound of the groin can be employed to evaluate for hernia; if a hernia has been excluded, histologic confirmation can be obtained via fine-needle aspiration of nodule contents.5,7 One caveat is that these tests are helpful only if the clinician suspects the diagnosis and orders them. The definitive diagnostic test remains direct visualization, which requires laparoscopy.1,5

Differential diagnosis

Lipoma was a favored diagnosis in this case because of the palpable, well-circumscribed borders, nontender on exam; intermittent, minimal tenderness; and no evidence of erythema or color change. A second possibility was an enlarged lymph node, which was less likely due to the location, large size, and sudden onset without any accompanying symptoms of infection or chronic illness. Finally, an inguinal hernia was least likely, again because of well-defined borders, no history of a lump in the area, a nodule that was not reducible, only minimal tenderness, and no color changes on the skin.

Management

Definitive treatment for inguinal endometriosis entails complete surgical excision.5-7 The provider should be prepared to repair a defect after the excision; there is potential for a substantial defect that might require mesh. Additionally, a herniorrhaphy may be indicated if there is a coexisting hernia.5 The risk for recurrent disease in the inguinal canal after treatment is uncommon, unless the excision was not complete.3

There is an association between inguinal and pelvic endometriosis but not a direct correlation. Data on concomitant pelvic and inguinal endometriosis have been variable. In one case series of 9 patients diagnosed with inguinal endometriosis, none had a history of pelvic endometriosis, and only 1 was subsequently diagnosed with pelvic endometriosis.7 An increased association was noted for patients with implants found on the proximal segment of the round ligament.7 However, implants on the extrapelvic segment were not likely to represent pelvic disease but rather isolated lesions in the canal.7 For those with pelvic endometriosis, complications and recurrence are likely, resulting in the need for long-term treatment.

There is some debate in the literature whether to proceed with laparoscopy once inguinal endometriosis has been identified. Diagnostic laparoscopy to evaluate the pelvis is indicated for symptomatic patients or for cases in which an indirect inguinal hernia is suspected.5 Laparoscopy can offer the benefit of both a diagnostic tool and a mechanism for treatment. However, this is an invasive procedure that also incurs risks. The medical provider, in discussion with the patient, must weigh the risks against the benefits of an invasive procedure before determining how to proceed.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

The lesion was excised completely. Since the patient had been entirely asymptomatic until age 47, and the risks of a potentially unnecessary surgery outweighed the theoretical benefits, the decision was made not to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy to investigate for pelvic endometriosis. The patient made a complete and uneventful recovery. No further treatment was initiated. She continues to be asymptomatic, denying any menstrual complaints, dyspareunia, or further problems with the groin.

CONCLUSION

This case describes a satellite lesion of endometrial tissue found in an unusual location, in a patient with no history, no risk factors, and no symptoms. The final diagnosis had been omitted from the differential—perhaps because the patient initially associated her symptoms with exercise and mentioned the correlation to her menstrual cycle as an afterthought. Fortunately, the correct diagnosis was made and the appropriate treatment provided.

There are numerous presentations of endometriosis; extrapelvic lesions can have very different, often vague, presentations when compared to the familiar symptoms of pelvic disease. Unfortunately, diagnosis is often delayed. Obscure presentations, in unusual sites, can further impede both speed and accuracy of diagnosis. To date, there are no lab tests or biomarkers to aid diagnosis; imaging studies are inconsistent. Until more accurate diagnostic tools become available, the diagnosis remains dependent on history taking, physical exam, and the clinical judgment of the provider. The astute clinician will recognize the catamenial pattern and consider endometriosis as part of the differential.

A 47-year-old woman was referred to the gynecology office by her primary care NP for surgical excision of an enlarging nodule on the right side of her mons pubis. Onset occurred about 6 months earlier. The patient reported that symptoms waxed and waned but had worsened progressively over the past 2 to 3 months, adding that the nodule hurt only occasionally. She noted that symptoms were exacerbated by exercise, specifically running. Further questioning prompted the observation that her symptoms were more noticeable at the time of menses.

The patient’s medical history was unremarkable, with no chronic conditions; her surgical history consisted of a wisdom tooth extraction. She had no known drug allergies. Her family history included cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, and arthritis. Reproductive history revealed that she was G1 P1, with a 38-week uncomplicated vaginal delivery. She experienced menarche at age 14, and her menses was regular at every 28 days. For the past 5 days, there had been no dysmenorrhea. The patient was married, exercised regularly, and did not use tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.

On examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 123/73 mm Hg; heart rate, 77 beats/min; respiratory rate, 12 breaths/min; weight, 128 lb; height, 5 ft 7 in; O2 saturation, 99% on room air; and BMI, 20. The patient was alert and oriented to person, place, and time. She was thin, appeared physically fit, and exhibited no signs of distress. Her physical exam was unremarkable, apart from a firm, minimally tender, well-circumscribed, 3.5 × 3.5–cm nodule right of midline on the mons pubis.

The patient was scheduled for outpatient surgical excision of a benign skin lesion (excluding skin tags) of the genitalia, 3.1 to 3.5 cm (CPT code 11424). During this procedure, it became evident that this was not a lipoma. The lesion was exceptionally hard, and it was difficult to discern if it was incorporated into the rectus abdominis near the point of attachment to the pubic symphysis. The lesion was unintentionally disrupted, revealing black powdery material within the capsule. The tissue was sent for a fast, frozen section that showed “soft tissue with extensive involvement by endometriosis.” The pathology report noted “[m]any endometrial glands in a background of stromal tissue. Necrosis was not a feature. No evidence of atypia.” The patient’s postoperative diagnosis was endometriosis.

DISCUSSION

Endometriosis occurs when endometrial or “endometrial-like” tissue is displaced to sites other than within the uterus. It is most frequently found on tissues close to the uterus, such as the ovaries or pelvic peritoneum. Estrogen is the driving force that feeds the endometrium, causing it to proliferate, whether inside or outside the uterus. Given this dependence on hormones, endometriosis occurs most often during a woman’s fertile years, although it can occur after menopause. Endometriosis is common, affecting at least 10% of premenopausal women; moreover, it is identified as the cause in 70% of all female chronic pelvic pain cases.1-4

Endometriosis has certain identifiable features, such as chronic pain, dyspareunia, infertility, and menstrual and gastrointestinal symptoms. However, it is seldom diagnosed quickly; studies indicate that diagnosis can be delayed by 5 to 10 years after a patient has first sought treatment for symptoms.2,4 Multiple factors contribute to a lag in diagnosis: Presentation is not always straightforward. There are no definitive lab values or biomarkers. Symptoms vary from patient to patient, as do clinical skills from one diagnostician to another.1

Unlike pelvic endometriosis, inguinal endometriosis is not common; disease in this location encompasses only 0.3% to 0.6% of all diagnosed cases.3,5-7 Since the discovery of the first known case of round ligament endometriosis in 1896, there have been only 70 cases reported in the medical literature.6,7

If the more common form of endometriosis is frequently missed, this rarely seen variant presents an even greater diagnostic challenge. The typical presentation of inguinal endometriosis includes a firm nodule in the groin, accompanied by tenderness and swelling. A careful history will allude to pain that occurs cyclically with menses.

Cause

Among several theories about the etiology of endometriosis, the most popular has been retrograde menstruation.1,4,5 According to this hypothesis, the flow of menstrual blood moves backward through the fallopian tubes, spilling into the pelvic cavity and carrying endometrial tissue with it. One theory purports that endometrial tissue is transplanted from the uterus to other areas of the body via the bloodstream or the lymphatics, much like a metastatic disease.1,4 Another theory states that cells outside the uterus, which line the peritoneum, transform into endometrial cells through metaplasia.4,5 Endometrial tissue can also be transplanted iatrogenically during surgery—for example, when endometrial tissue is displaced during a cesarean delivery, resulting in implants above the fascia and below the subcutaneous layers. Several other hypotheses concern stem-cell involvement, hormonal factors, immune system dysfunction, and genetics.4,5 Currently, there are no definitive answers.

Location

During maturation, the parietal peritoneum develops a pouch called the processus vaginalis, which serves as a passageway for the gubernaculum to transport the round ligament running from the uterus, through the inguinal canal, and ending at the labia. After these structures reach their destination, in normal development, the processus vaginalis degenerates, closing the inguinal canal. Occasionally the processus vaginalis fails to close, allowing for a communication pathway between the peritoneal cavity and the inguinal canal. This leaves the canal vulnerable to the contents of the pelvic cavity, such as a hernia or hydrocele, and provides a clear path for endometriosis.5-7 The implant found in the case patient was at the point where the external ring lies, just above the right pubic tubercle (see Figure 1).

Endometriosis implants can occur anywhere along the round ligament in either the intrapelvic or extrapelvic segments. Implants have also been found in the wall of a hernia sac, the wall of a Nuck canal hydrocele, or even in the subcutaneous tissue surrounding the inguinal canal.3 Interestingly, inguinal endometriosis occurs more often in the right side (up to 94% of cases) than in the left side, as was the case with our patient.5-7 The reason for this predominance has not been established, although there are several theories, including one that suggests the left side is afforded protection by the sigmoid colon.5-7

Laboratory diagnosis

Imaging, such as ultrasound and MRI, offers some diagnostic benefit, although its usefulness is most often realized in the pelvis. Pelvic ultrasound can be used to identify ovarian endometriomas.1 MRI can help rule out, locate, or sometimes determine the degree of deep infiltrating endometriosis, which is an indispensable tool for surgical planning.5,7 Unfortunately, the diagnostic accuracy for extra-pelvic lesions is variable; neither modality is particularly useful in identifying superficial lesions, which comprises most cases.

Ultrasound of the groin can be employed to evaluate for hernia; if a hernia has been excluded, histologic confirmation can be obtained via fine-needle aspiration of nodule contents.5,7 One caveat is that these tests are helpful only if the clinician suspects the diagnosis and orders them. The definitive diagnostic test remains direct visualization, which requires laparoscopy.1,5

Differential diagnosis

Lipoma was a favored diagnosis in this case because of the palpable, well-circumscribed borders, nontender on exam; intermittent, minimal tenderness; and no evidence of erythema or color change. A second possibility was an enlarged lymph node, which was less likely due to the location, large size, and sudden onset without any accompanying symptoms of infection or chronic illness. Finally, an inguinal hernia was least likely, again because of well-defined borders, no history of a lump in the area, a nodule that was not reducible, only minimal tenderness, and no color changes on the skin.

Management

Definitive treatment for inguinal endometriosis entails complete surgical excision.5-7 The provider should be prepared to repair a defect after the excision; there is potential for a substantial defect that might require mesh. Additionally, a herniorrhaphy may be indicated if there is a coexisting hernia.5 The risk for recurrent disease in the inguinal canal after treatment is uncommon, unless the excision was not complete.3

There is an association between inguinal and pelvic endometriosis but not a direct correlation. Data on concomitant pelvic and inguinal endometriosis have been variable. In one case series of 9 patients diagnosed with inguinal endometriosis, none had a history of pelvic endometriosis, and only 1 was subsequently diagnosed with pelvic endometriosis.7 An increased association was noted for patients with implants found on the proximal segment of the round ligament.7 However, implants on the extrapelvic segment were not likely to represent pelvic disease but rather isolated lesions in the canal.7 For those with pelvic endometriosis, complications and recurrence are likely, resulting in the need for long-term treatment.

There is some debate in the literature whether to proceed with laparoscopy once inguinal endometriosis has been identified. Diagnostic laparoscopy to evaluate the pelvis is indicated for symptomatic patients or for cases in which an indirect inguinal hernia is suspected.5 Laparoscopy can offer the benefit of both a diagnostic tool and a mechanism for treatment. However, this is an invasive procedure that also incurs risks. The medical provider, in discussion with the patient, must weigh the risks against the benefits of an invasive procedure before determining how to proceed.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

The lesion was excised completely. Since the patient had been entirely asymptomatic until age 47, and the risks of a potentially unnecessary surgery outweighed the theoretical benefits, the decision was made not to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy to investigate for pelvic endometriosis. The patient made a complete and uneventful recovery. No further treatment was initiated. She continues to be asymptomatic, denying any menstrual complaints, dyspareunia, or further problems with the groin.

CONCLUSION

This case describes a satellite lesion of endometrial tissue found in an unusual location, in a patient with no history, no risk factors, and no symptoms. The final diagnosis had been omitted from the differential—perhaps because the patient initially associated her symptoms with exercise and mentioned the correlation to her menstrual cycle as an afterthought. Fortunately, the correct diagnosis was made and the appropriate treatment provided.

There are numerous presentations of endometriosis; extrapelvic lesions can have very different, often vague, presentations when compared to the familiar symptoms of pelvic disease. Unfortunately, diagnosis is often delayed. Obscure presentations, in unusual sites, can further impede both speed and accuracy of diagnosis. To date, there are no lab tests or biomarkers to aid diagnosis; imaging studies are inconsistent. Until more accurate diagnostic tools become available, the diagnosis remains dependent on history taking, physical exam, and the clinical judgment of the provider. The astute clinician will recognize the catamenial pattern and consider endometriosis as part of the differential.

1. Parasar P, Ozcan P, Terry KL. Endometriosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2017;6(1):34-41.

2. Soliman AM, Fuldeore M, Snabes MC. Factors associated with time to endometriosis diagnosis in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(7):788-797.

3. Niitsu H, Tsumura H, Kanehiro T, et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical treatment for inguinal endometriosis in young women of reproductive age. Dig Surg. 2019;36(2):166-172.

4. Mehedintu C, Plotogea MN, Ionescu S, Antonovici M. Endometriosis still a challenge. J Med Life. 2014;7(3):349-357.

5. Wolfhagen N, Simons NE, de Jong KH, et al. Inguinal endometriosis, a rare entity of which surgeons should be aware: clinical aspects and long-term follow-up of nine cases. Hernia. 2018;22(5):881-886.

6. Prabhu R, Krishna S, Shenoy R, Thangavelu S. Endometriosis of extra-pelvic round ligament, a diagnostic dilemma for physicians. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.

7. Pandey D, Coondoo A, Shetty J, Mathew S. Jack in the box: inguinal endometriosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015.

1. Parasar P, Ozcan P, Terry KL. Endometriosis: epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2017;6(1):34-41.

2. Soliman AM, Fuldeore M, Snabes MC. Factors associated with time to endometriosis diagnosis in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(7):788-797.

3. Niitsu H, Tsumura H, Kanehiro T, et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical treatment for inguinal endometriosis in young women of reproductive age. Dig Surg. 2019;36(2):166-172.

4. Mehedintu C, Plotogea MN, Ionescu S, Antonovici M. Endometriosis still a challenge. J Med Life. 2014;7(3):349-357.

5. Wolfhagen N, Simons NE, de Jong KH, et al. Inguinal endometriosis, a rare entity of which surgeons should be aware: clinical aspects and long-term follow-up of nine cases. Hernia. 2018;22(5):881-886.

6. Prabhu R, Krishna S, Shenoy R, Thangavelu S. Endometriosis of extra-pelvic round ligament, a diagnostic dilemma for physicians. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.

7. Pandey D, Coondoo A, Shetty J, Mathew S. Jack in the box: inguinal endometriosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015.

FDA approves cefiderocol for multidrug-resistant, complicated urinary tract infections

The Food and Drug Administration announced that it has approved cefiderocol (Fetroja), an IV antibacterial drug to treat complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs), including kidney infections, caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative microorganisms in patients 18 years of age or older.

The safety and effectiveness of cefiderocol was demonstrated in a pivotal study of 448 patients with cUTIs. Published results indicated that 73% of patients had resolution of symptoms and eradication of the bacteria approximately 7 days after completing treatment, compared with 55% in patients who received an alternative antibiotic.

observed in comparison to patients treated with other antibiotics in a trial of critically ill patients having multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections (clinical trials. gov NCT02714595).

The cause of the increase in mortality has not been determined, according to the FDA. Some of the deaths in the study were attributable to worsening or complications of infection, or underlying comorbidities, in patients treated for hospital-acquired/ventilator-associated pneumonia (i.e., nosocomial pneumonia), bloodstream infections, or sepsis. Thus, safety and efficacy of cefiderocol has not been established for the treating these types of infections, according to the announcement.

Adverse reactions observed in patients treated with cefiderocol included diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, elevations in liver tests, rash, infusion-site reactions, and candidiasis. The FDA added that cefiderocol should not be used in persons known to have a severe hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibacterial drugs.

“A key global challenge the FDA faces as a public health agency is addressing the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections, like cUTIs. This approval represents another step forward in the FDA’s overall efforts to ensure safe and effective antimicrobial drugs are available to patients for treating infections,” John Farley, MD, acting director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the FDA press statement.

Fetroja is a product of Shionogi.

The Food and Drug Administration announced that it has approved cefiderocol (Fetroja), an IV antibacterial drug to treat complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs), including kidney infections, caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative microorganisms in patients 18 years of age or older.

The safety and effectiveness of cefiderocol was demonstrated in a pivotal study of 448 patients with cUTIs. Published results indicated that 73% of patients had resolution of symptoms and eradication of the bacteria approximately 7 days after completing treatment, compared with 55% in patients who received an alternative antibiotic.

observed in comparison to patients treated with other antibiotics in a trial of critically ill patients having multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections (clinical trials. gov NCT02714595).

The cause of the increase in mortality has not been determined, according to the FDA. Some of the deaths in the study were attributable to worsening or complications of infection, or underlying comorbidities, in patients treated for hospital-acquired/ventilator-associated pneumonia (i.e., nosocomial pneumonia), bloodstream infections, or sepsis. Thus, safety and efficacy of cefiderocol has not been established for the treating these types of infections, according to the announcement.

Adverse reactions observed in patients treated with cefiderocol included diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, elevations in liver tests, rash, infusion-site reactions, and candidiasis. The FDA added that cefiderocol should not be used in persons known to have a severe hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibacterial drugs.

“A key global challenge the FDA faces as a public health agency is addressing the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections, like cUTIs. This approval represents another step forward in the FDA’s overall efforts to ensure safe and effective antimicrobial drugs are available to patients for treating infections,” John Farley, MD, acting director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the FDA press statement.

Fetroja is a product of Shionogi.

The Food and Drug Administration announced that it has approved cefiderocol (Fetroja), an IV antibacterial drug to treat complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs), including kidney infections, caused by multidrug-resistant gram-negative microorganisms in patients 18 years of age or older.

The safety and effectiveness of cefiderocol was demonstrated in a pivotal study of 448 patients with cUTIs. Published results indicated that 73% of patients had resolution of symptoms and eradication of the bacteria approximately 7 days after completing treatment, compared with 55% in patients who received an alternative antibiotic.

observed in comparison to patients treated with other antibiotics in a trial of critically ill patients having multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections (clinical trials. gov NCT02714595).

The cause of the increase in mortality has not been determined, according to the FDA. Some of the deaths in the study were attributable to worsening or complications of infection, or underlying comorbidities, in patients treated for hospital-acquired/ventilator-associated pneumonia (i.e., nosocomial pneumonia), bloodstream infections, or sepsis. Thus, safety and efficacy of cefiderocol has not been established for the treating these types of infections, according to the announcement.

Adverse reactions observed in patients treated with cefiderocol included diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, elevations in liver tests, rash, infusion-site reactions, and candidiasis. The FDA added that cefiderocol should not be used in persons known to have a severe hypersensitivity to beta-lactam antibacterial drugs.

“A key global challenge the FDA faces as a public health agency is addressing the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections, like cUTIs. This approval represents another step forward in the FDA’s overall efforts to ensure safe and effective antimicrobial drugs are available to patients for treating infections,” John Farley, MD, acting director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in the FDA press statement.

Fetroja is a product of Shionogi.

FROM THE FDA

Opioid reduction works after minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

VANCOUVER – Two new randomized trials demonstrate that pain following minimally invasive gynecologic surgery can be successfully managed using reduced opioid prescriptions.

In each case, patients were randomized to receive higher or lower numbers of oxycodone tablets. In both trials, the lower amount was five 5-mg oxycodone tablets. The work should reassure surgeons who wish to change their prescribing patterns, but may worry about patient dissatisfaction, at least in the context of prolapse repair and benign minor gynecologic laparoscopy, which were the focus of the two studies.

The ob.gyn. literature cites rates of 4%-6% of persistent opioid use after surgery on opioid-naive patients, and that’s a risk that needs to be addressed. “If we look at this as a risk factor of our surgical process, this is much higher than any other risk in patients undergoing surgery, and it’s not something we routinely talk to patients about,” Kari Plewniak, MD, an ob.gyn. at Montefiore Medical Center, New York, said during her presentation on pain control during benign gynecologic laparoscopy at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

The trials provide some welcome guidance. “They provide pretty concrete guidelines with strong evidence of safety, so this is really helpful,” said Sean Dowdy, MD, chair of gynecologic oncology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., while speaking as a discussant for the presentations.

Emily Davidson, MD, and associates at the Cleveland Clinic conducted a single-institution, noninferiority trial of standard- versus reduced-prescription opioids in 116 women undergoing prolapse repair. Half were randomized to receive 28 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone (routine arm) and half were prescribed just 5 tablets (reduced arm). All patients also received multimodal pain therapy featuring acetaminophen and ibuprofen. The mean age of patients was 62 years, 91% were white, and 84% were post menopausal. The most common surgery was hysterectomy combined with native tissue repair (60.2%), followed by vaginal colpopexy (15.3%), hysteropexy (15.3%), and sacrocolpopexy (9.3%).

At their postsurgical visit, patients were asked about their satisfaction with their postoperative pain management; 93% in the reduced arm reported that they were very satisfied or somewhat satisfied, as did 93% in the routine arm, which met the standard for noninferiority with a 15% margin. About 15% of patients in the reduced arm used more opioids than originally prescribed, compared with 2% of patients in the routine arm (P less than .01). The reduced arm had an average of 4 unused opioid tablets, compared with 26 in the routine arm. On average, the reduced arm used one tablet, compared with three in the routine arm (P = .03).

The researchers suggested that clinicians should consider prescribing 5-10 tablets for most patients, and all patients should receive multimodal pain management.

The noninferiority nature of the design was welcome, according to Dr. Dowdy. “I think we need to do more noninferiority trial designs because it allows us to make more observations about other parts of the value equation, so if we have two interventions that are equivalent, we can pick the one that has the best patient experience and the lowest cost, so it simplifies a lot of our management.”

The other study, conducted at Montefiore Medical Center, set out to see if a similar regimen of 5 5-mg oxycodone tablets, combined with acetaminophen and ibuprofen, could adequately manage postoperative pain after minor benign gynecologic laparoscopy (excluding hysterectomy), compared with a 10-tablet regimen. All patients received 25 tablets of 600 mg ibuprofen (1 tablet every 6 hours or as needed), plus 50 tablets of 250 mg acetaminophen (1-2 tablets every 6 hours or as needed).

The median number of opioid tablets taken was 2.0 in the 5-tablet group and 2.5 in the 10-tablet group; 32% and 28% took no tablets, and 68% and 65% took three or fewer tablets in the respective groups. The median number of leftover opioid tablets was 3 in the 5-tablet group and 8 in the 10-tablet group, reported Dr. Plewniak.

The studies are a good first step, but more is needed, according to Dr. Dowdy. It’s important to begin looking at more-challenging patient groups, such as those who are not opioid naive, as well as patients taking buprenorphine. “That creates some unique challenges with postoperative pain management,” he said.

Dr. Dowdy, Dr. Davidson, and Dr. Plewniak have no relevant financial disclosures.*

* This article was updated 11/27/2019.

VANCOUVER – Two new randomized trials demonstrate that pain following minimally invasive gynecologic surgery can be successfully managed using reduced opioid prescriptions.

In each case, patients were randomized to receive higher or lower numbers of oxycodone tablets. In both trials, the lower amount was five 5-mg oxycodone tablets. The work should reassure surgeons who wish to change their prescribing patterns, but may worry about patient dissatisfaction, at least in the context of prolapse repair and benign minor gynecologic laparoscopy, which were the focus of the two studies.

The ob.gyn. literature cites rates of 4%-6% of persistent opioid use after surgery on opioid-naive patients, and that’s a risk that needs to be addressed. “If we look at this as a risk factor of our surgical process, this is much higher than any other risk in patients undergoing surgery, and it’s not something we routinely talk to patients about,” Kari Plewniak, MD, an ob.gyn. at Montefiore Medical Center, New York, said during her presentation on pain control during benign gynecologic laparoscopy at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

The trials provide some welcome guidance. “They provide pretty concrete guidelines with strong evidence of safety, so this is really helpful,” said Sean Dowdy, MD, chair of gynecologic oncology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., while speaking as a discussant for the presentations.

Emily Davidson, MD, and associates at the Cleveland Clinic conducted a single-institution, noninferiority trial of standard- versus reduced-prescription opioids in 116 women undergoing prolapse repair. Half were randomized to receive 28 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone (routine arm) and half were prescribed just 5 tablets (reduced arm). All patients also received multimodal pain therapy featuring acetaminophen and ibuprofen. The mean age of patients was 62 years, 91% were white, and 84% were post menopausal. The most common surgery was hysterectomy combined with native tissue repair (60.2%), followed by vaginal colpopexy (15.3%), hysteropexy (15.3%), and sacrocolpopexy (9.3%).

At their postsurgical visit, patients were asked about their satisfaction with their postoperative pain management; 93% in the reduced arm reported that they were very satisfied or somewhat satisfied, as did 93% in the routine arm, which met the standard for noninferiority with a 15% margin. About 15% of patients in the reduced arm used more opioids than originally prescribed, compared with 2% of patients in the routine arm (P less than .01). The reduced arm had an average of 4 unused opioid tablets, compared with 26 in the routine arm. On average, the reduced arm used one tablet, compared with three in the routine arm (P = .03).

The researchers suggested that clinicians should consider prescribing 5-10 tablets for most patients, and all patients should receive multimodal pain management.

The noninferiority nature of the design was welcome, according to Dr. Dowdy. “I think we need to do more noninferiority trial designs because it allows us to make more observations about other parts of the value equation, so if we have two interventions that are equivalent, we can pick the one that has the best patient experience and the lowest cost, so it simplifies a lot of our management.”

The other study, conducted at Montefiore Medical Center, set out to see if a similar regimen of 5 5-mg oxycodone tablets, combined with acetaminophen and ibuprofen, could adequately manage postoperative pain after minor benign gynecologic laparoscopy (excluding hysterectomy), compared with a 10-tablet regimen. All patients received 25 tablets of 600 mg ibuprofen (1 tablet every 6 hours or as needed), plus 50 tablets of 250 mg acetaminophen (1-2 tablets every 6 hours or as needed).

The median number of opioid tablets taken was 2.0 in the 5-tablet group and 2.5 in the 10-tablet group; 32% and 28% took no tablets, and 68% and 65% took three or fewer tablets in the respective groups. The median number of leftover opioid tablets was 3 in the 5-tablet group and 8 in the 10-tablet group, reported Dr. Plewniak.

The studies are a good first step, but more is needed, according to Dr. Dowdy. It’s important to begin looking at more-challenging patient groups, such as those who are not opioid naive, as well as patients taking buprenorphine. “That creates some unique challenges with postoperative pain management,” he said.

Dr. Dowdy, Dr. Davidson, and Dr. Plewniak have no relevant financial disclosures.*

* This article was updated 11/27/2019.

VANCOUVER – Two new randomized trials demonstrate that pain following minimally invasive gynecologic surgery can be successfully managed using reduced opioid prescriptions.

In each case, patients were randomized to receive higher or lower numbers of oxycodone tablets. In both trials, the lower amount was five 5-mg oxycodone tablets. The work should reassure surgeons who wish to change their prescribing patterns, but may worry about patient dissatisfaction, at least in the context of prolapse repair and benign minor gynecologic laparoscopy, which were the focus of the two studies.

The ob.gyn. literature cites rates of 4%-6% of persistent opioid use after surgery on opioid-naive patients, and that’s a risk that needs to be addressed. “If we look at this as a risk factor of our surgical process, this is much higher than any other risk in patients undergoing surgery, and it’s not something we routinely talk to patients about,” Kari Plewniak, MD, an ob.gyn. at Montefiore Medical Center, New York, said during her presentation on pain control during benign gynecologic laparoscopy at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

The trials provide some welcome guidance. “They provide pretty concrete guidelines with strong evidence of safety, so this is really helpful,” said Sean Dowdy, MD, chair of gynecologic oncology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., while speaking as a discussant for the presentations.

Emily Davidson, MD, and associates at the Cleveland Clinic conducted a single-institution, noninferiority trial of standard- versus reduced-prescription opioids in 116 women undergoing prolapse repair. Half were randomized to receive 28 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone (routine arm) and half were prescribed just 5 tablets (reduced arm). All patients also received multimodal pain therapy featuring acetaminophen and ibuprofen. The mean age of patients was 62 years, 91% were white, and 84% were post menopausal. The most common surgery was hysterectomy combined with native tissue repair (60.2%), followed by vaginal colpopexy (15.3%), hysteropexy (15.3%), and sacrocolpopexy (9.3%).

At their postsurgical visit, patients were asked about their satisfaction with their postoperative pain management; 93% in the reduced arm reported that they were very satisfied or somewhat satisfied, as did 93% in the routine arm, which met the standard for noninferiority with a 15% margin. About 15% of patients in the reduced arm used more opioids than originally prescribed, compared with 2% of patients in the routine arm (P less than .01). The reduced arm had an average of 4 unused opioid tablets, compared with 26 in the routine arm. On average, the reduced arm used one tablet, compared with three in the routine arm (P = .03).

The researchers suggested that clinicians should consider prescribing 5-10 tablets for most patients, and all patients should receive multimodal pain management.

The noninferiority nature of the design was welcome, according to Dr. Dowdy. “I think we need to do more noninferiority trial designs because it allows us to make more observations about other parts of the value equation, so if we have two interventions that are equivalent, we can pick the one that has the best patient experience and the lowest cost, so it simplifies a lot of our management.”

The other study, conducted at Montefiore Medical Center, set out to see if a similar regimen of 5 5-mg oxycodone tablets, combined with acetaminophen and ibuprofen, could adequately manage postoperative pain after minor benign gynecologic laparoscopy (excluding hysterectomy), compared with a 10-tablet regimen. All patients received 25 tablets of 600 mg ibuprofen (1 tablet every 6 hours or as needed), plus 50 tablets of 250 mg acetaminophen (1-2 tablets every 6 hours or as needed).

The median number of opioid tablets taken was 2.0 in the 5-tablet group and 2.5 in the 10-tablet group; 32% and 28% took no tablets, and 68% and 65% took three or fewer tablets in the respective groups. The median number of leftover opioid tablets was 3 in the 5-tablet group and 8 in the 10-tablet group, reported Dr. Plewniak.

The studies are a good first step, but more is needed, according to Dr. Dowdy. It’s important to begin looking at more-challenging patient groups, such as those who are not opioid naive, as well as patients taking buprenorphine. “That creates some unique challenges with postoperative pain management,” he said.

Dr. Dowdy, Dr. Davidson, and Dr. Plewniak have no relevant financial disclosures.*

* This article was updated 11/27/2019.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Surgical staging improves cervical cancer outcomes

VANCOUVER – Follow-up oncologic data from the UTERUS-11 trial shows advantages to surgical staging over clinical staging in stage IIB-IVA cervical cancer, with little apparent risk.

Compared with clinical staging using CT, laparoscopic staging led to an improvement in cancer-specific survival, with no delays in treatment or increases in toxicity. It also prompted surgical up-staging and led to treatment changes in 33% of cases. There was no difference in overall survival, but progression-free survival trended towards better outcomes in the surgical-staging group.

The new study presents 5-year follow-up data from patients randomly assigned to surgical (n = 121) or clinical staging (n = 114). The original study, published in 2017 (Oncology. 2017;92[4]:213-20), reported that 33% of surgical-staging patients in the surgical staging were up-staged as a result, compared with 6% who were revealed to have positive paraaortic lymph nodes through a CT-guided core biopsy after suspicious CT results. After a median follow-up of 90 months in both arms, overall survival was similar between the two groups, and progression-free survival trended towards an improvement in the surgical-staging group (P = .088). Cancer-specific survival was better in the surgical-staging arm, compared with clinical staging (P=.028), Audrey Tsunoda, MD, PhD, reported.

Surgical staging didn’t impact the toxicity profile, said Dr. Tsunoda, a surgical oncologist focused in gynecologic cancer surgery who practices at Hospital Erasto Gaertner in Curitiba, Brazil.

The mean time to initiation of chemoradiotherapy following surgery was 14 days (range, 7-21 days) after surgery: 64% had intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 36% had three-dimensional radiotherapy. There were no grade 5 toxicities during chemoradiotherapy and both groups had similar gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity profiles. About 97% of the surgical staging procedures were conducted laparoscopically. Two patients had a blood loss of more than 500 cc, and two had a delay to primary chemoradiotherapy (4 days and 5 days). One patient had to be converted to an open approach because of obesity and severe adhesions, and there was no intraoperative mortality.

Previous retrospective studies examining surgical staging in these patients led to confusion and disagreements among guidelines. Surgical staging is clearly associated with increased up-staging, but the oncologic benefit is uncertain. The LiLACS study attempted to address the question with prospective data, but failed to accrue enough patients and was later abandoned. That leaves the UTERUS-11 study, the initial results of which were published in 2017, as the first prospective study to examine the benefit of surgical staging.

The new follow-up results suggest a benefit to surgical staging, but they leave an important question unanswered, according to Lois Ramondetta, MD, professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, who served as a discussant at the meeting sponsored by AAGL. “Paraaortic lymph node status does connect to clinical benefit, but the question is really [whether] the removal of the lymph nodes accounts for the benefit, or is the identification of them and the change in treatment plan responsible? [If the latter is the case], a PET scan would have done a better job,” said Dr. Ramondetta. “The question remains unanswered, but I think this was huge progress in trying to answer it. Future studies need to incorporate a PET scan.”

Dr. Tsunoda has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Roche. Dr. Ramondetta has no relevant financial disclosures.

VANCOUVER – Follow-up oncologic data from the UTERUS-11 trial shows advantages to surgical staging over clinical staging in stage IIB-IVA cervical cancer, with little apparent risk.

Compared with clinical staging using CT, laparoscopic staging led to an improvement in cancer-specific survival, with no delays in treatment or increases in toxicity. It also prompted surgical up-staging and led to treatment changes in 33% of cases. There was no difference in overall survival, but progression-free survival trended towards better outcomes in the surgical-staging group.

The new study presents 5-year follow-up data from patients randomly assigned to surgical (n = 121) or clinical staging (n = 114). The original study, published in 2017 (Oncology. 2017;92[4]:213-20), reported that 33% of surgical-staging patients in the surgical staging were up-staged as a result, compared with 6% who were revealed to have positive paraaortic lymph nodes through a CT-guided core biopsy after suspicious CT results. After a median follow-up of 90 months in both arms, overall survival was similar between the two groups, and progression-free survival trended towards an improvement in the surgical-staging group (P = .088). Cancer-specific survival was better in the surgical-staging arm, compared with clinical staging (P=.028), Audrey Tsunoda, MD, PhD, reported.

Surgical staging didn’t impact the toxicity profile, said Dr. Tsunoda, a surgical oncologist focused in gynecologic cancer surgery who practices at Hospital Erasto Gaertner in Curitiba, Brazil.

The mean time to initiation of chemoradiotherapy following surgery was 14 days (range, 7-21 days) after surgery: 64% had intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 36% had three-dimensional radiotherapy. There were no grade 5 toxicities during chemoradiotherapy and both groups had similar gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity profiles. About 97% of the surgical staging procedures were conducted laparoscopically. Two patients had a blood loss of more than 500 cc, and two had a delay to primary chemoradiotherapy (4 days and 5 days). One patient had to be converted to an open approach because of obesity and severe adhesions, and there was no intraoperative mortality.

Previous retrospective studies examining surgical staging in these patients led to confusion and disagreements among guidelines. Surgical staging is clearly associated with increased up-staging, but the oncologic benefit is uncertain. The LiLACS study attempted to address the question with prospective data, but failed to accrue enough patients and was later abandoned. That leaves the UTERUS-11 study, the initial results of which were published in 2017, as the first prospective study to examine the benefit of surgical staging.

The new follow-up results suggest a benefit to surgical staging, but they leave an important question unanswered, according to Lois Ramondetta, MD, professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, who served as a discussant at the meeting sponsored by AAGL. “Paraaortic lymph node status does connect to clinical benefit, but the question is really [whether] the removal of the lymph nodes accounts for the benefit, or is the identification of them and the change in treatment plan responsible? [If the latter is the case], a PET scan would have done a better job,” said Dr. Ramondetta. “The question remains unanswered, but I think this was huge progress in trying to answer it. Future studies need to incorporate a PET scan.”

Dr. Tsunoda has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Roche. Dr. Ramondetta has no relevant financial disclosures.

VANCOUVER – Follow-up oncologic data from the UTERUS-11 trial shows advantages to surgical staging over clinical staging in stage IIB-IVA cervical cancer, with little apparent risk.

Compared with clinical staging using CT, laparoscopic staging led to an improvement in cancer-specific survival, with no delays in treatment or increases in toxicity. It also prompted surgical up-staging and led to treatment changes in 33% of cases. There was no difference in overall survival, but progression-free survival trended towards better outcomes in the surgical-staging group.

The new study presents 5-year follow-up data from patients randomly assigned to surgical (n = 121) or clinical staging (n = 114). The original study, published in 2017 (Oncology. 2017;92[4]:213-20), reported that 33% of surgical-staging patients in the surgical staging were up-staged as a result, compared with 6% who were revealed to have positive paraaortic lymph nodes through a CT-guided core biopsy after suspicious CT results. After a median follow-up of 90 months in both arms, overall survival was similar between the two groups, and progression-free survival trended towards an improvement in the surgical-staging group (P = .088). Cancer-specific survival was better in the surgical-staging arm, compared with clinical staging (P=.028), Audrey Tsunoda, MD, PhD, reported.

Surgical staging didn’t impact the toxicity profile, said Dr. Tsunoda, a surgical oncologist focused in gynecologic cancer surgery who practices at Hospital Erasto Gaertner in Curitiba, Brazil.

The mean time to initiation of chemoradiotherapy following surgery was 14 days (range, 7-21 days) after surgery: 64% had intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 36% had three-dimensional radiotherapy. There were no grade 5 toxicities during chemoradiotherapy and both groups had similar gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity profiles. About 97% of the surgical staging procedures were conducted laparoscopically. Two patients had a blood loss of more than 500 cc, and two had a delay to primary chemoradiotherapy (4 days and 5 days). One patient had to be converted to an open approach because of obesity and severe adhesions, and there was no intraoperative mortality.

Previous retrospective studies examining surgical staging in these patients led to confusion and disagreements among guidelines. Surgical staging is clearly associated with increased up-staging, but the oncologic benefit is uncertain. The LiLACS study attempted to address the question with prospective data, but failed to accrue enough patients and was later abandoned. That leaves the UTERUS-11 study, the initial results of which were published in 2017, as the first prospective study to examine the benefit of surgical staging.

The new follow-up results suggest a benefit to surgical staging, but they leave an important question unanswered, according to Lois Ramondetta, MD, professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, who served as a discussant at the meeting sponsored by AAGL. “Paraaortic lymph node status does connect to clinical benefit, but the question is really [whether] the removal of the lymph nodes accounts for the benefit, or is the identification of them and the change in treatment plan responsible? [If the latter is the case], a PET scan would have done a better job,” said Dr. Ramondetta. “The question remains unanswered, but I think this was huge progress in trying to answer it. Future studies need to incorporate a PET scan.”

Dr. Tsunoda has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Roche. Dr. Ramondetta has no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Does tranexamic acid reduce mortality in women with postpartum hemorrhage?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 double-blind RCT that included 20,060 women with PPH from 21 countries (the WOMAN trial) found that the risk of maternal mortality was significantly lower among women who received tranexamic acid as part of their PPH treatment compared with placebo (1.5% [N = 155] vs 1.9% [N = 191]; P = .045; relative risk [RR] = 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-1; number needed to treat [NNT] = 250).1

Inclusion criteria were age 16 years or older, postpartum course complicated by hemorrhage of known or unknown etiology, and a case in which the clinician considered using tranexamic acid in addition to the standard of care. PPH was defined as > 500 mL blood loss after vaginal delivery, > 1000 mL blood loss after cesarean section, or blood loss sufficient to produce hemodynamic compromise.

Researchers randomized 10,051 women to the tranexamic acid group and 10,009 to the placebo group. Women in the experimental group received a 1-g IV injection of tranexamic acid over 10 to 20 minutes. A second dose was given if bleeding restarted after 30 minutes and within 24 hours of the first dose.

To reduce mortality give tranexamic acid promptly

Tranexamic acid reduced mortality most effectively compared with placebo when given within 3 hours of delivery (1.2% [N = 89] vs 1.7% [N = 127]; P = .008; RR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.52-0.91; NNT = 200). After 3 hours, no significant decrease in mortality occurred. No significant difference in effect was noted between vaginal and cesarean deliveries nor between uterine atony as the primary cause of hemorrhage and other causes.

Administering tranexamic acid didn’t reduce the composite primary endpoint of hysterectomy or death from all causes. Nor did it reduce the secondary endpoints of intrauterine tamponade, embolization, manual placental extraction, arterial ligation, blood transfusions, or number of units of packed red blood cells. The tranexamic acid group showed a significant decrease in cases of laparotomy for PPH (0.8% vs 1.3%; P = .002; RR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85; NNT = 200).

Women who received tranexamic acid vs placebo showed no significant difference in mortality from pulmonary embolism (0.1% [N = 10] vs 0.1% [N = 11]; P = .82; RR = .9; 95% CI, 0.38-2.13), organ failure ure (0.3% [N = 25] vs 0.2% [N = 18]; P = .29; RR = 1.38; 95% CI, 0.75-2.53), sepsis (0.2% [N = 15] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .15; RR = 1.87; 95% CI, 0.79-4.4), eclampsia (0.02% [N = 2] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .057; RR = .25; 95% CI, 0.05-1.17), or other causes (0.2% [N = 20] vs 0.2% [N = 20]; P = .99; RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.54-1.85).

Tranexamic acid doesn’t increase the risk of thromboembolism

A 2018 Cochrane review sought more broadly to determine the general effectiveness and safety of antifibrinolytic drugs in treating primary PPH.2 Of 15 RCTs identified, only 3 met the inclusion criteria for the review, 1 of which was the WOMAN trial (which contributed most of the data in the review). The other trials were a study conducted in France that recruited 152 women and a study of 200 women in Iran that contributed only 1 primary outcome—estimated blood loss—to the review. The former study didn’t report any maternal deaths, and the latter study didn’t look at maternal deaths. The Cochrane review concluded, based on data from the WOMAN trial, that IV tranexamic acid, if given as early as possible, reduced mortality from bleeding in women with primary PPH after both vaginal and cesarean delivery and didn’t increase the risk of thromboembolic events.2

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The newest practice guidelines on the management of postpartum hemorrhage published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends considering tranexamic acid as an additional agent in managing PPH when initial standard-of-care treatments fail.3

Editor’s takeaway

The large international double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial provides convincing evidence that tranexamic acid should be administered readily in cases of PPH.

1. WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2105–2116.

2. Shakur H, Beaumont D, Pavord S, et al. Antifibrinolytic drugs for treating primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD012964.

3. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e168-e186.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2017 double-blind RCT that included 20,060 women with PPH from 21 countries (the WOMAN trial) found that the risk of maternal mortality was significantly lower among women who received tranexamic acid as part of their PPH treatment compared with placebo (1.5% [N = 155] vs 1.9% [N = 191]; P = .045; relative risk [RR] = 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65-1; number needed to treat [NNT] = 250).1

Inclusion criteria were age 16 years or older, postpartum course complicated by hemorrhage of known or unknown etiology, and a case in which the clinician considered using tranexamic acid in addition to the standard of care. PPH was defined as > 500 mL blood loss after vaginal delivery, > 1000 mL blood loss after cesarean section, or blood loss sufficient to produce hemodynamic compromise.

Researchers randomized 10,051 women to the tranexamic acid group and 10,009 to the placebo group. Women in the experimental group received a 1-g IV injection of tranexamic acid over 10 to 20 minutes. A second dose was given if bleeding restarted after 30 minutes and within 24 hours of the first dose.

To reduce mortality give tranexamic acid promptly

Tranexamic acid reduced mortality most effectively compared with placebo when given within 3 hours of delivery (1.2% [N = 89] vs 1.7% [N = 127]; P = .008; RR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.52-0.91; NNT = 200). After 3 hours, no significant decrease in mortality occurred. No significant difference in effect was noted between vaginal and cesarean deliveries nor between uterine atony as the primary cause of hemorrhage and other causes.

Administering tranexamic acid didn’t reduce the composite primary endpoint of hysterectomy or death from all causes. Nor did it reduce the secondary endpoints of intrauterine tamponade, embolization, manual placental extraction, arterial ligation, blood transfusions, or number of units of packed red blood cells. The tranexamic acid group showed a significant decrease in cases of laparotomy for PPH (0.8% vs 1.3%; P = .002; RR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.49-0.85; NNT = 200).

Women who received tranexamic acid vs placebo showed no significant difference in mortality from pulmonary embolism (0.1% [N = 10] vs 0.1% [N = 11]; P = .82; RR = .9; 95% CI, 0.38-2.13), organ failure ure (0.3% [N = 25] vs 0.2% [N = 18]; P = .29; RR = 1.38; 95% CI, 0.75-2.53), sepsis (0.2% [N = 15] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .15; RR = 1.87; 95% CI, 0.79-4.4), eclampsia (0.02% [N = 2] vs 0.1% [N = 8]; P = .057; RR = .25; 95% CI, 0.05-1.17), or other causes (0.2% [N = 20] vs 0.2% [N = 20]; P = .99; RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.54-1.85).

Tranexamic acid doesn’t increase the risk of thromboembolism

A 2018 Cochrane review sought more broadly to determine the general effectiveness and safety of antifibrinolytic drugs in treating primary PPH.2 Of 15 RCTs identified, only 3 met the inclusion criteria for the review, 1 of which was the WOMAN trial (which contributed most of the data in the review). The other trials were a study conducted in France that recruited 152 women and a study of 200 women in Iran that contributed only 1 primary outcome—estimated blood loss—to the review. The former study didn’t report any maternal deaths, and the latter study didn’t look at maternal deaths. The Cochrane review concluded, based on data from the WOMAN trial, that IV tranexamic acid, if given as early as possible, reduced mortality from bleeding in women with primary PPH after both vaginal and cesarean delivery and didn’t increase the risk of thromboembolic events.2

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The newest practice guidelines on the management of postpartum hemorrhage published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends considering tranexamic acid as an additional agent in managing PPH when initial standard-of-care treatments fail.3

Editor’s takeaway

The large international double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial provides convincing evidence that tranexamic acid should be administered readily in cases of PPH.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY