User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Minimize blood pressure peaks, variability after stroke reperfusion

ST. LOUIS – Albuquerque. Investigators found that every 10–mm Hg increase in peak systolic pressure boosted the risk of in-hospital death 24% (P = .01) and reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a inpatient rehabilitation facility 13% (P = .03). Results were even stronger for peak mean arterial pressure, at 76% (P = .01) and 29% (P = .04), respectively; trends in the same direction for peak diastolic pressure were not statistically significant.

Also, every 10–mm Hg increase in blood pressure variability again increased the risk of dying in the hospital, whether it was systolic (33%; P = .002), diastolic (33%; P = .03), or mean arterial pressure variability (58%; P = .02). Higher variability also reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a rehab 10%-20%, but the findings, although close, were not statistically significant.

Neurologists generally do what they can to control blood pressure after stroke, and the study confirms the need to do that. What’s new is that the work was limited to reperfusion patients – intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase in 83.5%, mechanical thrombectomy in 60%, with some having both – which has not been the specific focus of much research.

“Be much more aggressive in terms of making sure the variability is limited and limiting the peaks,” especially within 24 hours of reperfusion, said lead investigator and stroke neurologist Dinesh Jillella, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “We want to be much more aggressive [with these patients]; it might limit our worse outcomes,” Dr. Jillella said. He conducted the review while in training at the University of New Mexico.

What led to the study is that Dr. Jillella and colleagues noticed that similar reperfusion patients can have very different outcomes, and he wanted to find modifiable risk factors that could account for the differences. The study did not address why high peaks and variability lead to worse outcomes, but he said hemorrhagic conversion might play a role.

It is also possible that higher pressures could be a marker of bad outcomes, as opposed to a direct cause, but the findings were adjusted for two significant confounders: age and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, which were both significantly higher in patients who did not do well. But after adjustment, “we [still] found an independent association with blood pressures and worse outcomes,” he said.

Higher peak systolic pressures and variability were also associated with about a 15% lower odds of leaving the hospital with a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or less, which means the patient has some moderate disability but is still able to walk without assistance.

Patients were 69 years old on average, and about 60% were men. The majority were white. About a third had a modified Rankin Scale score at or below 3 at discharge, and about two-thirds were discharged home or to a rehabilitation facility; 17% of patients died in the hospital.

Differences in antihypertensive regimens were not associated with outcomes on univariate analysis. Dr. Jillella said that, ideally, he would like to run a multicenter, prospective trial of blood pressure reduction targets after reperfusion.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Jillella didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

ST. LOUIS – Albuquerque. Investigators found that every 10–mm Hg increase in peak systolic pressure boosted the risk of in-hospital death 24% (P = .01) and reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a inpatient rehabilitation facility 13% (P = .03). Results were even stronger for peak mean arterial pressure, at 76% (P = .01) and 29% (P = .04), respectively; trends in the same direction for peak diastolic pressure were not statistically significant.

Also, every 10–mm Hg increase in blood pressure variability again increased the risk of dying in the hospital, whether it was systolic (33%; P = .002), diastolic (33%; P = .03), or mean arterial pressure variability (58%; P = .02). Higher variability also reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a rehab 10%-20%, but the findings, although close, were not statistically significant.

Neurologists generally do what they can to control blood pressure after stroke, and the study confirms the need to do that. What’s new is that the work was limited to reperfusion patients – intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase in 83.5%, mechanical thrombectomy in 60%, with some having both – which has not been the specific focus of much research.

“Be much more aggressive in terms of making sure the variability is limited and limiting the peaks,” especially within 24 hours of reperfusion, said lead investigator and stroke neurologist Dinesh Jillella, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “We want to be much more aggressive [with these patients]; it might limit our worse outcomes,” Dr. Jillella said. He conducted the review while in training at the University of New Mexico.

What led to the study is that Dr. Jillella and colleagues noticed that similar reperfusion patients can have very different outcomes, and he wanted to find modifiable risk factors that could account for the differences. The study did not address why high peaks and variability lead to worse outcomes, but he said hemorrhagic conversion might play a role.

It is also possible that higher pressures could be a marker of bad outcomes, as opposed to a direct cause, but the findings were adjusted for two significant confounders: age and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, which were both significantly higher in patients who did not do well. But after adjustment, “we [still] found an independent association with blood pressures and worse outcomes,” he said.

Higher peak systolic pressures and variability were also associated with about a 15% lower odds of leaving the hospital with a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or less, which means the patient has some moderate disability but is still able to walk without assistance.

Patients were 69 years old on average, and about 60% were men. The majority were white. About a third had a modified Rankin Scale score at or below 3 at discharge, and about two-thirds were discharged home or to a rehabilitation facility; 17% of patients died in the hospital.

Differences in antihypertensive regimens were not associated with outcomes on univariate analysis. Dr. Jillella said that, ideally, he would like to run a multicenter, prospective trial of blood pressure reduction targets after reperfusion.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Jillella didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

ST. LOUIS – Albuquerque. Investigators found that every 10–mm Hg increase in peak systolic pressure boosted the risk of in-hospital death 24% (P = .01) and reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a inpatient rehabilitation facility 13% (P = .03). Results were even stronger for peak mean arterial pressure, at 76% (P = .01) and 29% (P = .04), respectively; trends in the same direction for peak diastolic pressure were not statistically significant.

Also, every 10–mm Hg increase in blood pressure variability again increased the risk of dying in the hospital, whether it was systolic (33%; P = .002), diastolic (33%; P = .03), or mean arterial pressure variability (58%; P = .02). Higher variability also reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a rehab 10%-20%, but the findings, although close, were not statistically significant.

Neurologists generally do what they can to control blood pressure after stroke, and the study confirms the need to do that. What’s new is that the work was limited to reperfusion patients – intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase in 83.5%, mechanical thrombectomy in 60%, with some having both – which has not been the specific focus of much research.

“Be much more aggressive in terms of making sure the variability is limited and limiting the peaks,” especially within 24 hours of reperfusion, said lead investigator and stroke neurologist Dinesh Jillella, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “We want to be much more aggressive [with these patients]; it might limit our worse outcomes,” Dr. Jillella said. He conducted the review while in training at the University of New Mexico.

What led to the study is that Dr. Jillella and colleagues noticed that similar reperfusion patients can have very different outcomes, and he wanted to find modifiable risk factors that could account for the differences. The study did not address why high peaks and variability lead to worse outcomes, but he said hemorrhagic conversion might play a role.

It is also possible that higher pressures could be a marker of bad outcomes, as opposed to a direct cause, but the findings were adjusted for two significant confounders: age and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, which were both significantly higher in patients who did not do well. But after adjustment, “we [still] found an independent association with blood pressures and worse outcomes,” he said.

Higher peak systolic pressures and variability were also associated with about a 15% lower odds of leaving the hospital with a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or less, which means the patient has some moderate disability but is still able to walk without assistance.

Patients were 69 years old on average, and about 60% were men. The majority were white. About a third had a modified Rankin Scale score at or below 3 at discharge, and about two-thirds were discharged home or to a rehabilitation facility; 17% of patients died in the hospital.

Differences in antihypertensive regimens were not associated with outcomes on univariate analysis. Dr. Jillella said that, ideally, he would like to run a multicenter, prospective trial of blood pressure reduction targets after reperfusion.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Jillella didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ANA 2019

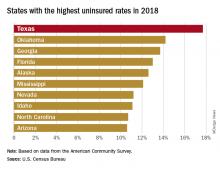

Uninsured population is big in Texas

There were just over 5 million uninsured people in the Lone Star State last year, representing an increase from 17.3% of the total population in 2017 to 17.7%, and that works out to an additional 186,000 residents with no health care coverage, the Census Bureau said in a recent report.

That 17.7% rate for 2018 gave Texas the highest proportion of uninsured population, putting it ahead of Oklahoma (14.2%), Georgia (13.7%), Florida (13.0%), Alaska (12.6%), and Mississippi (12.1%). Oklahoma had basically no change from 2017, while the other three each had a small but nonsignificant increase. Nationally, the rate of uninsured population went from 7.9% in 2017 to 8.5% in 2018, the Census Bureau investigators said.

On the other end of the coverage spectrum was Massachusetts, where only 2.8% of the population, or about 189,000 people, lacked health insurance in 2018. Washington, D.C., was next with an uninsured rate of 3.2%, followed by Vermont (4.0%), Hawaii (4.1%), Rhode Island (4.1%), and Minnesota (4.4%), they said, based on data from the American Community Survey.

A separate analysis of Census Bureau data by the personal finance website WalletHub showed that states that expanded Medicaid along with their Affordable Care Act implementation had an average uninsured rate of 7.0% in 2018, compared with 11.1% for states that did not expand eligibility.

All 50 states were in negative territory when changes in uninsured rates were calculated over a longer time period, 2010-2018, as the national rate fell by 6.6%. The largest drops among the states came in Nevada (–11.4%), California (–11.3%), Oregon (–10.1%), and New Mexico (–10.1%), while Massachusetts (–1.7%), Maine (–2.1%), and North Dakota (–2.5%) had the smallest declines, WalletHub reported.

There were just over 5 million uninsured people in the Lone Star State last year, representing an increase from 17.3% of the total population in 2017 to 17.7%, and that works out to an additional 186,000 residents with no health care coverage, the Census Bureau said in a recent report.

That 17.7% rate for 2018 gave Texas the highest proportion of uninsured population, putting it ahead of Oklahoma (14.2%), Georgia (13.7%), Florida (13.0%), Alaska (12.6%), and Mississippi (12.1%). Oklahoma had basically no change from 2017, while the other three each had a small but nonsignificant increase. Nationally, the rate of uninsured population went from 7.9% in 2017 to 8.5% in 2018, the Census Bureau investigators said.

On the other end of the coverage spectrum was Massachusetts, where only 2.8% of the population, or about 189,000 people, lacked health insurance in 2018. Washington, D.C., was next with an uninsured rate of 3.2%, followed by Vermont (4.0%), Hawaii (4.1%), Rhode Island (4.1%), and Minnesota (4.4%), they said, based on data from the American Community Survey.

A separate analysis of Census Bureau data by the personal finance website WalletHub showed that states that expanded Medicaid along with their Affordable Care Act implementation had an average uninsured rate of 7.0% in 2018, compared with 11.1% for states that did not expand eligibility.

All 50 states were in negative territory when changes in uninsured rates were calculated over a longer time period, 2010-2018, as the national rate fell by 6.6%. The largest drops among the states came in Nevada (–11.4%), California (–11.3%), Oregon (–10.1%), and New Mexico (–10.1%), while Massachusetts (–1.7%), Maine (–2.1%), and North Dakota (–2.5%) had the smallest declines, WalletHub reported.

There were just over 5 million uninsured people in the Lone Star State last year, representing an increase from 17.3% of the total population in 2017 to 17.7%, and that works out to an additional 186,000 residents with no health care coverage, the Census Bureau said in a recent report.

That 17.7% rate for 2018 gave Texas the highest proportion of uninsured population, putting it ahead of Oklahoma (14.2%), Georgia (13.7%), Florida (13.0%), Alaska (12.6%), and Mississippi (12.1%). Oklahoma had basically no change from 2017, while the other three each had a small but nonsignificant increase. Nationally, the rate of uninsured population went from 7.9% in 2017 to 8.5% in 2018, the Census Bureau investigators said.

On the other end of the coverage spectrum was Massachusetts, where only 2.8% of the population, or about 189,000 people, lacked health insurance in 2018. Washington, D.C., was next with an uninsured rate of 3.2%, followed by Vermont (4.0%), Hawaii (4.1%), Rhode Island (4.1%), and Minnesota (4.4%), they said, based on data from the American Community Survey.

A separate analysis of Census Bureau data by the personal finance website WalletHub showed that states that expanded Medicaid along with their Affordable Care Act implementation had an average uninsured rate of 7.0% in 2018, compared with 11.1% for states that did not expand eligibility.

All 50 states were in negative territory when changes in uninsured rates were calculated over a longer time period, 2010-2018, as the national rate fell by 6.6%. The largest drops among the states came in Nevada (–11.4%), California (–11.3%), Oregon (–10.1%), and New Mexico (–10.1%), while Massachusetts (–1.7%), Maine (–2.1%), and North Dakota (–2.5%) had the smallest declines, WalletHub reported.

Bringing focus to the issue: Dr. Elizabeth Loder on gender in medicine

The recently published “Eleven Things Not to Say to Your Female Colleagues,” has sparked debate on medical Twitter. Senior author Elizabeth Loder, MD, developed the content collaboratively with members of the Migraine Mavens, a private Facebook group of North American headache practitioners and researchers.

In an interview, Dr. Loder, chief of the headache division in the neurology department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, shared the background and context for the article.

Q: Could you explain the impetus for putting this together? How did you arrive at the chart that is the center of the article?

A: In June, I gave the Seymour Solomon lecture at the American Headache Society annual scientific meeting. Because it was an award lecture, I was able to choose the topic. I decided to talk about gender-based problems faced by women in medicine, with a focus on the headache field.

These problems include sexual harassment, hurtful sex-based comments, gender-based barriers to career advancement, as well as the difficulties women face in getting institutions or professional societies to pay attention to these problems.

I wanted to provide real, recent examples of troubling behavior or comments, so I appealed to the Migraine Mavens group to describe their own experiences. I was not expecting the response I got. Not only did people post many examples of such behavior in the group, but I also received many private messages describing things that were so hurtful or private that the woman involved did not even feel comfortable posting them in our group.

I ended up with plenty of real-life vignettes. The title of my talk was “Time’s Up: Headache Medicine in the #MeToo Era.” Shortly after the talk, a member of the group posted this:

“Oh, Dr. Elizabeth Loder, how timely was your talk yesterday, and we have so much further to progress. ...

“Just now, I had this experience: I have been recently selected for a leadership position within AHS and I was talking to one of our male colleagues about it. ... He expressed his doubt in my ability to serve this role well.

“I thought it was because I am early in my career, and as I was reassuring him that I would reach out to him and others for mentorship, he then said ‘AND you have two small children. ... You don’t have time for this.’ ”

There was lively discussion in the group about how this poster could have responded and what bystanders could have said. One of the group members, Clarimar Borrero-Mejias, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, pointed out that many men and women might benefit from knowing what kinds of things not to say to other colleagues. I suggested that we should take some of the problems we had discussed and write a paper, and that she should be the first author. We then crowdsourced the scenarios to be included.

The grid format came immediately to mind because I know that tables and charts and boxes are good ways to organize and present information. We also wanted to keep the article short and accessible, and thus the idea of “Ten Things” was born. At the end of our work, though, someone posted the vignette about the salary discussion. It was amazing to me how many women, even in this day and age, are still told that men deserve more money because of their family or other responsibilities. We thus decided that it had to be 11, not 10, things.

The article was possible only because of the supportive reaction of the editor of Headache, Thomas Ward, MD. He not only published the piece rapidly, but also agreed to make it free so that anyone who wanted to could access the entire article without hitting a paywall (Headache. 2019 Sep 26. doi: 10.1111/head.13647).

Q: Could you share some of the reactions you’ve gotten? I did see that Esther Choo, MD – an emergency medicine physician and prominent proponent for gender equity in medicine – highlighted the article on Twitter; are there other highlights, or surprising reactions, or pushback, that you’d like to share?

A: We were thrilled to be the subject of a “tweetorial” by Dr. Choo. It’s impossible to overestimate the boost this gave to the paper. She has over 75,000 Twitter followers, and it was quite impressive to watch the exponential increase in the article’s Altmetrics score after her tweetorial. This brought the article to the attention of people outside our own subspecialty. The experiences we described seem to be familiar to women doctors in every specialty and subspecialty, and also relevant outside medicine. I saw tweets from women lawyers, engineers, and others, many of whom said this sort of behavior is a problem in their own fields.

It’s probably not surprising that the vast majority of reactions came from women. A number of men tweeted the article, though, and recommended it to other men. This sort of #HeForShe support is gratifying. We did get some negative reactions, but there are Migraine Mavens on Twitter and we’ve taken them on.

Q: You offer suggestions for reframing many behaviors that reflect implicit bias. You also offer suggestions for bystanders to challenge these biases and support women who are on the receiving end of the behaviors you call out. Do you think exhibiting more of this kind of solidarity can help change the culture of medicine?

A: I believe many people who witness the behaviors are uncomfortable and would like to help but just don’t know what to say. Often, they are caught off guard. Some of our suggested responses are all-purpose lines that can be effective simply by calling attention to the behavior, for example, “What did you just say?” or “Why would you say something like that?” As Dr. Choo said, “Learn them, say them often.”

It’s critical to remember that problems like this are not in the past. This article gave real examples of things that have happened to real women recently. The sheer number of women who retweeted the article with statements such as, “How many of these have been said to you? Straw poll. I got 9,” demonstrates that behavior like this is common.

I recently received an email that forwarded a message written by a medical assistant. I’ve changed the names, but it otherwise read “Dr. Smith wants this patient to have a nerve block. ... You can schedule them with Abigail or Nancy.” Guess what? Abigail and Nancy are doctors. Not only that, they are Dr. Smith’s true peers in every way imaginable, having been hired at exactly the same time and having exactly the same titles and duties. There seems to be only one reason they are not addressed as doctor while their male colleague is, and that is their gender. So the struggle highlighted by #MyFirstNameIsDoctor is real. Women doctors live it every day.

koakes@mdedge.com

The recently published “Eleven Things Not to Say to Your Female Colleagues,” has sparked debate on medical Twitter. Senior author Elizabeth Loder, MD, developed the content collaboratively with members of the Migraine Mavens, a private Facebook group of North American headache practitioners and researchers.

In an interview, Dr. Loder, chief of the headache division in the neurology department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, shared the background and context for the article.

Q: Could you explain the impetus for putting this together? How did you arrive at the chart that is the center of the article?

A: In June, I gave the Seymour Solomon lecture at the American Headache Society annual scientific meeting. Because it was an award lecture, I was able to choose the topic. I decided to talk about gender-based problems faced by women in medicine, with a focus on the headache field.

These problems include sexual harassment, hurtful sex-based comments, gender-based barriers to career advancement, as well as the difficulties women face in getting institutions or professional societies to pay attention to these problems.

I wanted to provide real, recent examples of troubling behavior or comments, so I appealed to the Migraine Mavens group to describe their own experiences. I was not expecting the response I got. Not only did people post many examples of such behavior in the group, but I also received many private messages describing things that were so hurtful or private that the woman involved did not even feel comfortable posting them in our group.

I ended up with plenty of real-life vignettes. The title of my talk was “Time’s Up: Headache Medicine in the #MeToo Era.” Shortly after the talk, a member of the group posted this:

“Oh, Dr. Elizabeth Loder, how timely was your talk yesterday, and we have so much further to progress. ...

“Just now, I had this experience: I have been recently selected for a leadership position within AHS and I was talking to one of our male colleagues about it. ... He expressed his doubt in my ability to serve this role well.

“I thought it was because I am early in my career, and as I was reassuring him that I would reach out to him and others for mentorship, he then said ‘AND you have two small children. ... You don’t have time for this.’ ”

There was lively discussion in the group about how this poster could have responded and what bystanders could have said. One of the group members, Clarimar Borrero-Mejias, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, pointed out that many men and women might benefit from knowing what kinds of things not to say to other colleagues. I suggested that we should take some of the problems we had discussed and write a paper, and that she should be the first author. We then crowdsourced the scenarios to be included.

The grid format came immediately to mind because I know that tables and charts and boxes are good ways to organize and present information. We also wanted to keep the article short and accessible, and thus the idea of “Ten Things” was born. At the end of our work, though, someone posted the vignette about the salary discussion. It was amazing to me how many women, even in this day and age, are still told that men deserve more money because of their family or other responsibilities. We thus decided that it had to be 11, not 10, things.

The article was possible only because of the supportive reaction of the editor of Headache, Thomas Ward, MD. He not only published the piece rapidly, but also agreed to make it free so that anyone who wanted to could access the entire article without hitting a paywall (Headache. 2019 Sep 26. doi: 10.1111/head.13647).

Q: Could you share some of the reactions you’ve gotten? I did see that Esther Choo, MD – an emergency medicine physician and prominent proponent for gender equity in medicine – highlighted the article on Twitter; are there other highlights, or surprising reactions, or pushback, that you’d like to share?

A: We were thrilled to be the subject of a “tweetorial” by Dr. Choo. It’s impossible to overestimate the boost this gave to the paper. She has over 75,000 Twitter followers, and it was quite impressive to watch the exponential increase in the article’s Altmetrics score after her tweetorial. This brought the article to the attention of people outside our own subspecialty. The experiences we described seem to be familiar to women doctors in every specialty and subspecialty, and also relevant outside medicine. I saw tweets from women lawyers, engineers, and others, many of whom said this sort of behavior is a problem in their own fields.

It’s probably not surprising that the vast majority of reactions came from women. A number of men tweeted the article, though, and recommended it to other men. This sort of #HeForShe support is gratifying. We did get some negative reactions, but there are Migraine Mavens on Twitter and we’ve taken them on.

Q: You offer suggestions for reframing many behaviors that reflect implicit bias. You also offer suggestions for bystanders to challenge these biases and support women who are on the receiving end of the behaviors you call out. Do you think exhibiting more of this kind of solidarity can help change the culture of medicine?

A: I believe many people who witness the behaviors are uncomfortable and would like to help but just don’t know what to say. Often, they are caught off guard. Some of our suggested responses are all-purpose lines that can be effective simply by calling attention to the behavior, for example, “What did you just say?” or “Why would you say something like that?” As Dr. Choo said, “Learn them, say them often.”

It’s critical to remember that problems like this are not in the past. This article gave real examples of things that have happened to real women recently. The sheer number of women who retweeted the article with statements such as, “How many of these have been said to you? Straw poll. I got 9,” demonstrates that behavior like this is common.

I recently received an email that forwarded a message written by a medical assistant. I’ve changed the names, but it otherwise read “Dr. Smith wants this patient to have a nerve block. ... You can schedule them with Abigail or Nancy.” Guess what? Abigail and Nancy are doctors. Not only that, they are Dr. Smith’s true peers in every way imaginable, having been hired at exactly the same time and having exactly the same titles and duties. There seems to be only one reason they are not addressed as doctor while their male colleague is, and that is their gender. So the struggle highlighted by #MyFirstNameIsDoctor is real. Women doctors live it every day.

koakes@mdedge.com

The recently published “Eleven Things Not to Say to Your Female Colleagues,” has sparked debate on medical Twitter. Senior author Elizabeth Loder, MD, developed the content collaboratively with members of the Migraine Mavens, a private Facebook group of North American headache practitioners and researchers.

In an interview, Dr. Loder, chief of the headache division in the neurology department at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, shared the background and context for the article.

Q: Could you explain the impetus for putting this together? How did you arrive at the chart that is the center of the article?

A: In June, I gave the Seymour Solomon lecture at the American Headache Society annual scientific meeting. Because it was an award lecture, I was able to choose the topic. I decided to talk about gender-based problems faced by women in medicine, with a focus on the headache field.

These problems include sexual harassment, hurtful sex-based comments, gender-based barriers to career advancement, as well as the difficulties women face in getting institutions or professional societies to pay attention to these problems.

I wanted to provide real, recent examples of troubling behavior or comments, so I appealed to the Migraine Mavens group to describe their own experiences. I was not expecting the response I got. Not only did people post many examples of such behavior in the group, but I also received many private messages describing things that were so hurtful or private that the woman involved did not even feel comfortable posting them in our group.

I ended up with plenty of real-life vignettes. The title of my talk was “Time’s Up: Headache Medicine in the #MeToo Era.” Shortly after the talk, a member of the group posted this:

“Oh, Dr. Elizabeth Loder, how timely was your talk yesterday, and we have so much further to progress. ...

“Just now, I had this experience: I have been recently selected for a leadership position within AHS and I was talking to one of our male colleagues about it. ... He expressed his doubt in my ability to serve this role well.

“I thought it was because I am early in my career, and as I was reassuring him that I would reach out to him and others for mentorship, he then said ‘AND you have two small children. ... You don’t have time for this.’ ”

There was lively discussion in the group about how this poster could have responded and what bystanders could have said. One of the group members, Clarimar Borrero-Mejias, MD, a pediatric neurologist at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, pointed out that many men and women might benefit from knowing what kinds of things not to say to other colleagues. I suggested that we should take some of the problems we had discussed and write a paper, and that she should be the first author. We then crowdsourced the scenarios to be included.

The grid format came immediately to mind because I know that tables and charts and boxes are good ways to organize and present information. We also wanted to keep the article short and accessible, and thus the idea of “Ten Things” was born. At the end of our work, though, someone posted the vignette about the salary discussion. It was amazing to me how many women, even in this day and age, are still told that men deserve more money because of their family or other responsibilities. We thus decided that it had to be 11, not 10, things.

The article was possible only because of the supportive reaction of the editor of Headache, Thomas Ward, MD. He not only published the piece rapidly, but also agreed to make it free so that anyone who wanted to could access the entire article without hitting a paywall (Headache. 2019 Sep 26. doi: 10.1111/head.13647).

Q: Could you share some of the reactions you’ve gotten? I did see that Esther Choo, MD – an emergency medicine physician and prominent proponent for gender equity in medicine – highlighted the article on Twitter; are there other highlights, or surprising reactions, or pushback, that you’d like to share?

A: We were thrilled to be the subject of a “tweetorial” by Dr. Choo. It’s impossible to overestimate the boost this gave to the paper. She has over 75,000 Twitter followers, and it was quite impressive to watch the exponential increase in the article’s Altmetrics score after her tweetorial. This brought the article to the attention of people outside our own subspecialty. The experiences we described seem to be familiar to women doctors in every specialty and subspecialty, and also relevant outside medicine. I saw tweets from women lawyers, engineers, and others, many of whom said this sort of behavior is a problem in their own fields.

It’s probably not surprising that the vast majority of reactions came from women. A number of men tweeted the article, though, and recommended it to other men. This sort of #HeForShe support is gratifying. We did get some negative reactions, but there are Migraine Mavens on Twitter and we’ve taken them on.

Q: You offer suggestions for reframing many behaviors that reflect implicit bias. You also offer suggestions for bystanders to challenge these biases and support women who are on the receiving end of the behaviors you call out. Do you think exhibiting more of this kind of solidarity can help change the culture of medicine?

A: I believe many people who witness the behaviors are uncomfortable and would like to help but just don’t know what to say. Often, they are caught off guard. Some of our suggested responses are all-purpose lines that can be effective simply by calling attention to the behavior, for example, “What did you just say?” or “Why would you say something like that?” As Dr. Choo said, “Learn them, say them often.”

It’s critical to remember that problems like this are not in the past. This article gave real examples of things that have happened to real women recently. The sheer number of women who retweeted the article with statements such as, “How many of these have been said to you? Straw poll. I got 9,” demonstrates that behavior like this is common.

I recently received an email that forwarded a message written by a medical assistant. I’ve changed the names, but it otherwise read “Dr. Smith wants this patient to have a nerve block. ... You can schedule them with Abigail or Nancy.” Guess what? Abigail and Nancy are doctors. Not only that, they are Dr. Smith’s true peers in every way imaginable, having been hired at exactly the same time and having exactly the same titles and duties. There seems to be only one reason they are not addressed as doctor while their male colleague is, and that is their gender. So the struggle highlighted by #MyFirstNameIsDoctor is real. Women doctors live it every day.

koakes@mdedge.com

Court of Appeals to decide fate of Medicaid work requirements

The debate over whether states can impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients is now in the hands of a federal appeals court.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia heard oral arguments Oct. 11, 2019, in two cases that challenge state waivers that require work as part of Medicaid eligibility.

In Stewart v. Azar, 16 patients from Kentucky are suing the Department of Health & Human Services over its approval of changes to Kentucky’s Medicaid program that include work requirements, premiums, and lockouts. In Gresham v. Azar, several Arkansas residents are challenging HHS over the approval of modifications to Arkansas’ Medicaid program that require work requirements and eliminate retroactive coverage.

The restrictive conditions in the Medicaid waivers would cause thousands of Medicaid enrollees to lose coverage, according to Jane Perkins, legal director for the National Health Law Program, an advocacy firm representing the plaintiffs.

“Section 1115 of the Social Security Act only allows the [HHS] Secretary to approve experimental projects that further Medicaid’s purpose of furnishing medical assistance to low-income people,” Ms. Perkins said in a statement. “These waiver projects do not further this objective. By the government’s own framing, they are intended to transform Medicaid and explode Medicaid expansion. Only Congress can rewrite a statute – not this administration. We hope the appellate court will uphold the well-reasoned opinions of the district court.”

HHS argues that it has the authority to allow any experimental, pilot, or demonstration project likely to promote the objectives of Medicaid, which in addition to medical assistance include rehabilitation services that help patients attain or retain independence or self-care. The waivers from Kentucky and Arkansas are consistent with these objectives, attorneys for HHS argued in court documents.

Kentucky’s waiver project promotes beneficiary health and financial independence, while Arkansas’ demonstration is likely to assist in improving health outcomes through strategies that promote community engagement and address health determinants, according to letters from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service approving the projects.

Arkansas’ demonstration project, approved in March 2018, includes a requirement that adults aged 19-49 years complete 80 hours per month of community engagement activities, such as employment, education, job-skills training, or community service, as a condition of continued Medicaid eligibility. Kentucky’s proposal, approved in November 2018, requires Medicaid patients to spend at least 80 hours per month on qualified activities, including employment, job skills training, education, community services and/or participation in substance use disorder treatment.

Medicaid patients in both states sued HHS shortly after the waivers were approved, arguing that the work requirements were arbitrary and capricious and that the agency exceeded its statutory authority in approving the projects. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in favor of the patients in March 2019, finding that HHS failed to fully consider the impact of the Kentucky and Arkansas changes on current and future Medicaid beneficiaries. In a decision for Kentucky and a separate ruling for Arkansas, the court vacated HHS’ approval of the projects and remanded both waivers back to HHS for reconsideration. In the interim, officials in both Kentucky and Arkansas halted implementation of the work requirements. The Department of Justice appealed in both cases.

According to court documents, 18,000 Arkansans lost coverage for failure to comply with the work requirements before the regulations were halted. In Kentucky, the state estimates that 95,000 Kentuckians could lose coverage if the project goes into effect.

A decision by the appeals court is expected by December 2019.

The debate over whether states can impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients is now in the hands of a federal appeals court.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia heard oral arguments Oct. 11, 2019, in two cases that challenge state waivers that require work as part of Medicaid eligibility.

In Stewart v. Azar, 16 patients from Kentucky are suing the Department of Health & Human Services over its approval of changes to Kentucky’s Medicaid program that include work requirements, premiums, and lockouts. In Gresham v. Azar, several Arkansas residents are challenging HHS over the approval of modifications to Arkansas’ Medicaid program that require work requirements and eliminate retroactive coverage.

The restrictive conditions in the Medicaid waivers would cause thousands of Medicaid enrollees to lose coverage, according to Jane Perkins, legal director for the National Health Law Program, an advocacy firm representing the plaintiffs.

“Section 1115 of the Social Security Act only allows the [HHS] Secretary to approve experimental projects that further Medicaid’s purpose of furnishing medical assistance to low-income people,” Ms. Perkins said in a statement. “These waiver projects do not further this objective. By the government’s own framing, they are intended to transform Medicaid and explode Medicaid expansion. Only Congress can rewrite a statute – not this administration. We hope the appellate court will uphold the well-reasoned opinions of the district court.”

HHS argues that it has the authority to allow any experimental, pilot, or demonstration project likely to promote the objectives of Medicaid, which in addition to medical assistance include rehabilitation services that help patients attain or retain independence or self-care. The waivers from Kentucky and Arkansas are consistent with these objectives, attorneys for HHS argued in court documents.

Kentucky’s waiver project promotes beneficiary health and financial independence, while Arkansas’ demonstration is likely to assist in improving health outcomes through strategies that promote community engagement and address health determinants, according to letters from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service approving the projects.

Arkansas’ demonstration project, approved in March 2018, includes a requirement that adults aged 19-49 years complete 80 hours per month of community engagement activities, such as employment, education, job-skills training, or community service, as a condition of continued Medicaid eligibility. Kentucky’s proposal, approved in November 2018, requires Medicaid patients to spend at least 80 hours per month on qualified activities, including employment, job skills training, education, community services and/or participation in substance use disorder treatment.

Medicaid patients in both states sued HHS shortly after the waivers were approved, arguing that the work requirements were arbitrary and capricious and that the agency exceeded its statutory authority in approving the projects. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in favor of the patients in March 2019, finding that HHS failed to fully consider the impact of the Kentucky and Arkansas changes on current and future Medicaid beneficiaries. In a decision for Kentucky and a separate ruling for Arkansas, the court vacated HHS’ approval of the projects and remanded both waivers back to HHS for reconsideration. In the interim, officials in both Kentucky and Arkansas halted implementation of the work requirements. The Department of Justice appealed in both cases.

According to court documents, 18,000 Arkansans lost coverage for failure to comply with the work requirements before the regulations were halted. In Kentucky, the state estimates that 95,000 Kentuckians could lose coverage if the project goes into effect.

A decision by the appeals court is expected by December 2019.

The debate over whether states can impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients is now in the hands of a federal appeals court.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia heard oral arguments Oct. 11, 2019, in two cases that challenge state waivers that require work as part of Medicaid eligibility.

In Stewart v. Azar, 16 patients from Kentucky are suing the Department of Health & Human Services over its approval of changes to Kentucky’s Medicaid program that include work requirements, premiums, and lockouts. In Gresham v. Azar, several Arkansas residents are challenging HHS over the approval of modifications to Arkansas’ Medicaid program that require work requirements and eliminate retroactive coverage.

The restrictive conditions in the Medicaid waivers would cause thousands of Medicaid enrollees to lose coverage, according to Jane Perkins, legal director for the National Health Law Program, an advocacy firm representing the plaintiffs.

“Section 1115 of the Social Security Act only allows the [HHS] Secretary to approve experimental projects that further Medicaid’s purpose of furnishing medical assistance to low-income people,” Ms. Perkins said in a statement. “These waiver projects do not further this objective. By the government’s own framing, they are intended to transform Medicaid and explode Medicaid expansion. Only Congress can rewrite a statute – not this administration. We hope the appellate court will uphold the well-reasoned opinions of the district court.”

HHS argues that it has the authority to allow any experimental, pilot, or demonstration project likely to promote the objectives of Medicaid, which in addition to medical assistance include rehabilitation services that help patients attain or retain independence or self-care. The waivers from Kentucky and Arkansas are consistent with these objectives, attorneys for HHS argued in court documents.

Kentucky’s waiver project promotes beneficiary health and financial independence, while Arkansas’ demonstration is likely to assist in improving health outcomes through strategies that promote community engagement and address health determinants, according to letters from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service approving the projects.

Arkansas’ demonstration project, approved in March 2018, includes a requirement that adults aged 19-49 years complete 80 hours per month of community engagement activities, such as employment, education, job-skills training, or community service, as a condition of continued Medicaid eligibility. Kentucky’s proposal, approved in November 2018, requires Medicaid patients to spend at least 80 hours per month on qualified activities, including employment, job skills training, education, community services and/or participation in substance use disorder treatment.

Medicaid patients in both states sued HHS shortly after the waivers were approved, arguing that the work requirements were arbitrary and capricious and that the agency exceeded its statutory authority in approving the projects. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in favor of the patients in March 2019, finding that HHS failed to fully consider the impact of the Kentucky and Arkansas changes on current and future Medicaid beneficiaries. In a decision for Kentucky and a separate ruling for Arkansas, the court vacated HHS’ approval of the projects and remanded both waivers back to HHS for reconsideration. In the interim, officials in both Kentucky and Arkansas halted implementation of the work requirements. The Department of Justice appealed in both cases.

According to court documents, 18,000 Arkansans lost coverage for failure to comply with the work requirements before the regulations were halted. In Kentucky, the state estimates that 95,000 Kentuckians could lose coverage if the project goes into effect.

A decision by the appeals court is expected by December 2019.

#MyFirstNameIsDoctor: Why it matters, and what you can do

When Shawnté James, MD, picked up the phone at work recently, a male physician on the other end was calling for a peer-to-peer review of a patient’s insurance issue.

“Hi, this is Dr. Y, calling to speak with Shawnté about patient X. Is she available?” asked the physician. “No,” replied Dr. James, an assistant professor of pediatrics at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington.

She related the rest of the interaction in a recent tweet:

“I’m Dr. XY calling a peer-to-peer review of a denial. Is Shawnté available?”

— Shawnté James (@ShawnteJamesMD) October 10, 2019

Me: “No.”

Him: “Is she in today?”

Me: “There’s no Shawnté here.”

Him: “Oh this is the number I have for Dr. Shawnté James”

Me: “Oh, DR. JAMES. Yes, that’s me. How can I help?”#MyFirstNameIsDoctor

The tweet, along with many others that used the hashtag #MyFirstNameIsDoctor, struck a chord among female physicians on Twitter. In tweets of their own, they related instance after instance of peers, coworkers, and patients assuming first-name familiarity with them – but not their male colleagues.

“This time it’s a peer-to-peer review. Last time it was being introduced to new hospital leadership as, ‘Shawnté, one of our pediatricians,’ ” Dr. James said in an interview. “The truth is, for physician women – particularly women of color – this is a regular occurrence.”

Data show an ongoing problem

Objective evidence that female physicians and scientists are significantly less likely than their male peers to be addressed by their titles came in a just-published study of presentations at the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology in 2017 and 2018.

Narjust Duma, MD, the study’s first author, described her growing awareness of the problem.

Dr. Duma recalled a session on the last day of the ASCO 2018 meeting. Five presenters were speaking – four men and a woman. “The woman is the one who knows the most about this subject. She’s the only one at the table who’s a full professor,” Dr. Duma, assistant professor of hematology/oncology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview. “And then everybody is introduced as ‘Dr. So-and-so,’ and when they come to her, they introduce her as ‘Julie.’ ”

“Is it just me?” Dr. Duma asked herself. The same day, she began a Twitter poll to ask whether her female peers were experiencing this phenomenon, and got an “overwhelming” response.

“We need data to learn the extent of the problem,” she said she realized.

The ASCO annual meeting afforded an ideal opportunity for data gathering, said Dr. Duma, because presentations are recorded and written transcripts generated. Dr. Duma assembled a research team that had a 50-50 gender balance and racial and ethnic diversity. The team combed ASCO transcripts to code introductions according to whether title and surname were used or whether speakers were addressed by first name only.

After excluding videos that did not capture speaker introductions, Dr. Duma and collaborators were left with 781 videos to watch and code.

Female speakers overall were less likely to be addressed by their professional title (62% vs. 81% for males, P less than .001). Male introducers used professional titles 53% of the time when introducing female speakers, and 80% of the time when introducing male speakers (P less than .01). No gender differences were seen when females were the introducers (J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01608).

Looking further, male introducers addressed female speakers by first name only in 24% of the cases. Female introducers used first names only with female speakers 7% of the time, a statistically significant difference. “This is the part that is really sad,” said Dr. Duma.

She and her coauthors also performed multivariable analysis to adjust for factors such as seniority and geographic location; after adjustment, males were still over 2.5 times as likely as females to be introduced with their professional title, and females were nearly six times as likely as males to be introduced by their first names only. When the introducer was male, a female speaker was over three times more likely to be introduced by her first name only.

Dr. Duma and colleagues are working with the ASCO 2020 planning team to develop a template that standardizes presenter introductions. They’re also planning for prospective data collection at that meeting, and will include self-reported race and ethnicity data for presenters and introducers who choose to provide it.

“We do not plan to create a ‘her versus him’ battle,” said Dr. Duma. “The goal is to use this hardcore data to bring attention to the problem.” She pointed out that, though fewer females introduced other females by first name only, the problem wasn’t limited only to male introducers at ASCO.

“The problem is unconscious bias. Nobody’s exempt,” said Dr. Duma. She related that she herself had just sent a work-related email to a female colleague that addressed her by her first name, and had copied many of their mutual colleagues. Realizing her gaffe, she held herself to her own standard by apologizing to her colleague and copying everyone who saw the first email. “The goal is to bring attention to the difference, so we can improve gender bias in medicine together.”

Patient interactions: Sometimes, a delicate balance

What’s the right approach when a patient, uninvited, addresses you by your first name? Natalie Strand, MD, had been thinking about the best way to handle this sticky situation for some time. Recently, she tried it out on a patient and shared her approach in a tweet:

So proud of myself!

— Natalie Strand (@DrNatStrand) October 11, 2019

After introducing myself as Dr. Strand to a patient, he looked at my name badge and said- oh, so Natalie.

Usually I’m stuck feeling afraid to rock the boat...

Not today!

“Yes, but I go by Dr. Strand at work! “

I finally said it!!!

There was an awkward moment with the patient, Dr. Strand acknowledged, “but we moved past it.”

Asserting one’s hard-earned status despite a societally ingrained desire to please or to avoid confrontation can be difficult, she acknowledged, but it’s worth it. Put simply, she said, “I want to be called Dr. Strand.”

The importance of this issue can sometimes be hard for male colleagues to understand, said Dr. Strand, who practices outpatient interventional pain medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz. “The people that have privilege – they don’t see it as privilege. And that’s not anybody’s fault. That’s just the reality of it, because that’s the norm. … That’s why putting a name to microaggression and microinsults is so powerful, because once you name it, then you can respond to it.”

Beginning from a point of mutual professionalism is a good place to start, Dr. Strand said in an interview. She always begins by addressing her patients by their surname and waits for patients to invite her to call them by their first names. “The most professional approach is the best first step,” she said. When she has a longstanding relationship with patients and she knows that trust and mutual respect have been established, she may also invite first-name familiarity.

“Patients don’t do this to be mean,” emphasized Dr. Strand, adding that, particularly with older patients, “they are trying to be sweet.” That’s part of the difficulty in finding a gentle but firm way to bring the relationship back to a professional footing.

Judging by the responses she’s gotten from other female physicians, this delicate situation, and the best way to ask for professionalism with patients, is a common struggle. Many of her female peers have said they’ll consider adopting her approach, she said.

“Male physicians are our allies,” said Dr. Strand. “The needs of the patients come first. This isn’t about power; it’s not about holding a power differential against the patient. It’s about having a culture of mutual respect, and being seen as a physician. Not as a female physician, not as a male physician. Just being seen as a physician, so you can act as a physician.”

Whether they come from patients or peers, said Dr. James, who adroitly called out the physician reviewer who asked for her by first name, “These microaggressions are uncomfortable to address at the time they occur – but they are teachable moments that we should all take advantage of. Usually, a gentle correction, such as, ‘I prefer to be addressed as Dr. James while at work,’ is sufficient.” However, she added, “sometimes, a firmer ‘I feel disrespected when you address me by my first name to colleagues and patients’ is needed.”

This article was updated 10/15/19.

When Shawnté James, MD, picked up the phone at work recently, a male physician on the other end was calling for a peer-to-peer review of a patient’s insurance issue.

“Hi, this is Dr. Y, calling to speak with Shawnté about patient X. Is she available?” asked the physician. “No,” replied Dr. James, an assistant professor of pediatrics at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington.

She related the rest of the interaction in a recent tweet:

“I’m Dr. XY calling a peer-to-peer review of a denial. Is Shawnté available?”

— Shawnté James (@ShawnteJamesMD) October 10, 2019

Me: “No.”

Him: “Is she in today?”

Me: “There’s no Shawnté here.”

Him: “Oh this is the number I have for Dr. Shawnté James”

Me: “Oh, DR. JAMES. Yes, that’s me. How can I help?”#MyFirstNameIsDoctor

The tweet, along with many others that used the hashtag #MyFirstNameIsDoctor, struck a chord among female physicians on Twitter. In tweets of their own, they related instance after instance of peers, coworkers, and patients assuming first-name familiarity with them – but not their male colleagues.

“This time it’s a peer-to-peer review. Last time it was being introduced to new hospital leadership as, ‘Shawnté, one of our pediatricians,’ ” Dr. James said in an interview. “The truth is, for physician women – particularly women of color – this is a regular occurrence.”

Data show an ongoing problem

Objective evidence that female physicians and scientists are significantly less likely than their male peers to be addressed by their titles came in a just-published study of presentations at the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology in 2017 and 2018.

Narjust Duma, MD, the study’s first author, described her growing awareness of the problem.

Dr. Duma recalled a session on the last day of the ASCO 2018 meeting. Five presenters were speaking – four men and a woman. “The woman is the one who knows the most about this subject. She’s the only one at the table who’s a full professor,” Dr. Duma, assistant professor of hematology/oncology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview. “And then everybody is introduced as ‘Dr. So-and-so,’ and when they come to her, they introduce her as ‘Julie.’ ”

“Is it just me?” Dr. Duma asked herself. The same day, she began a Twitter poll to ask whether her female peers were experiencing this phenomenon, and got an “overwhelming” response.

“We need data to learn the extent of the problem,” she said she realized.

The ASCO annual meeting afforded an ideal opportunity for data gathering, said Dr. Duma, because presentations are recorded and written transcripts generated. Dr. Duma assembled a research team that had a 50-50 gender balance and racial and ethnic diversity. The team combed ASCO transcripts to code introductions according to whether title and surname were used or whether speakers were addressed by first name only.

After excluding videos that did not capture speaker introductions, Dr. Duma and collaborators were left with 781 videos to watch and code.

Female speakers overall were less likely to be addressed by their professional title (62% vs. 81% for males, P less than .001). Male introducers used professional titles 53% of the time when introducing female speakers, and 80% of the time when introducing male speakers (P less than .01). No gender differences were seen when females were the introducers (J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01608).

Looking further, male introducers addressed female speakers by first name only in 24% of the cases. Female introducers used first names only with female speakers 7% of the time, a statistically significant difference. “This is the part that is really sad,” said Dr. Duma.

She and her coauthors also performed multivariable analysis to adjust for factors such as seniority and geographic location; after adjustment, males were still over 2.5 times as likely as females to be introduced with their professional title, and females were nearly six times as likely as males to be introduced by their first names only. When the introducer was male, a female speaker was over three times more likely to be introduced by her first name only.

Dr. Duma and colleagues are working with the ASCO 2020 planning team to develop a template that standardizes presenter introductions. They’re also planning for prospective data collection at that meeting, and will include self-reported race and ethnicity data for presenters and introducers who choose to provide it.

“We do not plan to create a ‘her versus him’ battle,” said Dr. Duma. “The goal is to use this hardcore data to bring attention to the problem.” She pointed out that, though fewer females introduced other females by first name only, the problem wasn’t limited only to male introducers at ASCO.

“The problem is unconscious bias. Nobody’s exempt,” said Dr. Duma. She related that she herself had just sent a work-related email to a female colleague that addressed her by her first name, and had copied many of their mutual colleagues. Realizing her gaffe, she held herself to her own standard by apologizing to her colleague and copying everyone who saw the first email. “The goal is to bring attention to the difference, so we can improve gender bias in medicine together.”

Patient interactions: Sometimes, a delicate balance

What’s the right approach when a patient, uninvited, addresses you by your first name? Natalie Strand, MD, had been thinking about the best way to handle this sticky situation for some time. Recently, she tried it out on a patient and shared her approach in a tweet:

So proud of myself!

— Natalie Strand (@DrNatStrand) October 11, 2019

After introducing myself as Dr. Strand to a patient, he looked at my name badge and said- oh, so Natalie.

Usually I’m stuck feeling afraid to rock the boat...

Not today!

“Yes, but I go by Dr. Strand at work! “

I finally said it!!!

There was an awkward moment with the patient, Dr. Strand acknowledged, “but we moved past it.”

Asserting one’s hard-earned status despite a societally ingrained desire to please or to avoid confrontation can be difficult, she acknowledged, but it’s worth it. Put simply, she said, “I want to be called Dr. Strand.”

The importance of this issue can sometimes be hard for male colleagues to understand, said Dr. Strand, who practices outpatient interventional pain medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz. “The people that have privilege – they don’t see it as privilege. And that’s not anybody’s fault. That’s just the reality of it, because that’s the norm. … That’s why putting a name to microaggression and microinsults is so powerful, because once you name it, then you can respond to it.”

Beginning from a point of mutual professionalism is a good place to start, Dr. Strand said in an interview. She always begins by addressing her patients by their surname and waits for patients to invite her to call them by their first names. “The most professional approach is the best first step,” she said. When she has a longstanding relationship with patients and she knows that trust and mutual respect have been established, she may also invite first-name familiarity.

“Patients don’t do this to be mean,” emphasized Dr. Strand, adding that, particularly with older patients, “they are trying to be sweet.” That’s part of the difficulty in finding a gentle but firm way to bring the relationship back to a professional footing.

Judging by the responses she’s gotten from other female physicians, this delicate situation, and the best way to ask for professionalism with patients, is a common struggle. Many of her female peers have said they’ll consider adopting her approach, she said.

“Male physicians are our allies,” said Dr. Strand. “The needs of the patients come first. This isn’t about power; it’s not about holding a power differential against the patient. It’s about having a culture of mutual respect, and being seen as a physician. Not as a female physician, not as a male physician. Just being seen as a physician, so you can act as a physician.”

Whether they come from patients or peers, said Dr. James, who adroitly called out the physician reviewer who asked for her by first name, “These microaggressions are uncomfortable to address at the time they occur – but they are teachable moments that we should all take advantage of. Usually, a gentle correction, such as, ‘I prefer to be addressed as Dr. James while at work,’ is sufficient.” However, she added, “sometimes, a firmer ‘I feel disrespected when you address me by my first name to colleagues and patients’ is needed.”

This article was updated 10/15/19.

When Shawnté James, MD, picked up the phone at work recently, a male physician on the other end was calling for a peer-to-peer review of a patient’s insurance issue.

“Hi, this is Dr. Y, calling to speak with Shawnté about patient X. Is she available?” asked the physician. “No,” replied Dr. James, an assistant professor of pediatrics at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington.

She related the rest of the interaction in a recent tweet:

“I’m Dr. XY calling a peer-to-peer review of a denial. Is Shawnté available?”

— Shawnté James (@ShawnteJamesMD) October 10, 2019

Me: “No.”

Him: “Is she in today?”

Me: “There’s no Shawnté here.”

Him: “Oh this is the number I have for Dr. Shawnté James”

Me: “Oh, DR. JAMES. Yes, that’s me. How can I help?”#MyFirstNameIsDoctor

The tweet, along with many others that used the hashtag #MyFirstNameIsDoctor, struck a chord among female physicians on Twitter. In tweets of their own, they related instance after instance of peers, coworkers, and patients assuming first-name familiarity with them – but not their male colleagues.

“This time it’s a peer-to-peer review. Last time it was being introduced to new hospital leadership as, ‘Shawnté, one of our pediatricians,’ ” Dr. James said in an interview. “The truth is, for physician women – particularly women of color – this is a regular occurrence.”

Data show an ongoing problem

Objective evidence that female physicians and scientists are significantly less likely than their male peers to be addressed by their titles came in a just-published study of presentations at the annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology in 2017 and 2018.

Narjust Duma, MD, the study’s first author, described her growing awareness of the problem.

Dr. Duma recalled a session on the last day of the ASCO 2018 meeting. Five presenters were speaking – four men and a woman. “The woman is the one who knows the most about this subject. She’s the only one at the table who’s a full professor,” Dr. Duma, assistant professor of hematology/oncology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in an interview. “And then everybody is introduced as ‘Dr. So-and-so,’ and when they come to her, they introduce her as ‘Julie.’ ”

“Is it just me?” Dr. Duma asked herself. The same day, she began a Twitter poll to ask whether her female peers were experiencing this phenomenon, and got an “overwhelming” response.

“We need data to learn the extent of the problem,” she said she realized.

The ASCO annual meeting afforded an ideal opportunity for data gathering, said Dr. Duma, because presentations are recorded and written transcripts generated. Dr. Duma assembled a research team that had a 50-50 gender balance and racial and ethnic diversity. The team combed ASCO transcripts to code introductions according to whether title and surname were used or whether speakers were addressed by first name only.

After excluding videos that did not capture speaker introductions, Dr. Duma and collaborators were left with 781 videos to watch and code.

Female speakers overall were less likely to be addressed by their professional title (62% vs. 81% for males, P less than .001). Male introducers used professional titles 53% of the time when introducing female speakers, and 80% of the time when introducing male speakers (P less than .01). No gender differences were seen when females were the introducers (J Clin Oncol. 2019 Oct 11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01608).

Looking further, male introducers addressed female speakers by first name only in 24% of the cases. Female introducers used first names only with female speakers 7% of the time, a statistically significant difference. “This is the part that is really sad,” said Dr. Duma.

She and her coauthors also performed multivariable analysis to adjust for factors such as seniority and geographic location; after adjustment, males were still over 2.5 times as likely as females to be introduced with their professional title, and females were nearly six times as likely as males to be introduced by their first names only. When the introducer was male, a female speaker was over three times more likely to be introduced by her first name only.

Dr. Duma and colleagues are working with the ASCO 2020 planning team to develop a template that standardizes presenter introductions. They’re also planning for prospective data collection at that meeting, and will include self-reported race and ethnicity data for presenters and introducers who choose to provide it.

“We do not plan to create a ‘her versus him’ battle,” said Dr. Duma. “The goal is to use this hardcore data to bring attention to the problem.” She pointed out that, though fewer females introduced other females by first name only, the problem wasn’t limited only to male introducers at ASCO.

“The problem is unconscious bias. Nobody’s exempt,” said Dr. Duma. She related that she herself had just sent a work-related email to a female colleague that addressed her by her first name, and had copied many of their mutual colleagues. Realizing her gaffe, she held herself to her own standard by apologizing to her colleague and copying everyone who saw the first email. “The goal is to bring attention to the difference, so we can improve gender bias in medicine together.”

Patient interactions: Sometimes, a delicate balance

What’s the right approach when a patient, uninvited, addresses you by your first name? Natalie Strand, MD, had been thinking about the best way to handle this sticky situation for some time. Recently, she tried it out on a patient and shared her approach in a tweet:

So proud of myself!

— Natalie Strand (@DrNatStrand) October 11, 2019

After introducing myself as Dr. Strand to a patient, he looked at my name badge and said- oh, so Natalie.

Usually I’m stuck feeling afraid to rock the boat...

Not today!

“Yes, but I go by Dr. Strand at work! “

I finally said it!!!

There was an awkward moment with the patient, Dr. Strand acknowledged, “but we moved past it.”

Asserting one’s hard-earned status despite a societally ingrained desire to please or to avoid confrontation can be difficult, she acknowledged, but it’s worth it. Put simply, she said, “I want to be called Dr. Strand.”

The importance of this issue can sometimes be hard for male colleagues to understand, said Dr. Strand, who practices outpatient interventional pain medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz. “The people that have privilege – they don’t see it as privilege. And that’s not anybody’s fault. That’s just the reality of it, because that’s the norm. … That’s why putting a name to microaggression and microinsults is so powerful, because once you name it, then you can respond to it.”

Beginning from a point of mutual professionalism is a good place to start, Dr. Strand said in an interview. She always begins by addressing her patients by their surname and waits for patients to invite her to call them by their first names. “The most professional approach is the best first step,” she said. When she has a longstanding relationship with patients and she knows that trust and mutual respect have been established, she may also invite first-name familiarity.

“Patients don’t do this to be mean,” emphasized Dr. Strand, adding that, particularly with older patients, “they are trying to be sweet.” That’s part of the difficulty in finding a gentle but firm way to bring the relationship back to a professional footing.

Judging by the responses she’s gotten from other female physicians, this delicate situation, and the best way to ask for professionalism with patients, is a common struggle. Many of her female peers have said they’ll consider adopting her approach, she said.

“Male physicians are our allies,” said Dr. Strand. “The needs of the patients come first. This isn’t about power; it’s not about holding a power differential against the patient. It’s about having a culture of mutual respect, and being seen as a physician. Not as a female physician, not as a male physician. Just being seen as a physician, so you can act as a physician.”

Whether they come from patients or peers, said Dr. James, who adroitly called out the physician reviewer who asked for her by first name, “These microaggressions are uncomfortable to address at the time they occur – but they are teachable moments that we should all take advantage of. Usually, a gentle correction, such as, ‘I prefer to be addressed as Dr. James while at work,’ is sufficient.” However, she added, “sometimes, a firmer ‘I feel disrespected when you address me by my first name to colleagues and patients’ is needed.”

This article was updated 10/15/19.

In patients with CIS, combined omics predicts conversion to clinically definite MS

STOCKHOLM –

Further, “combined omics improves diagnostic accuracy” over oligoclonal band (OCB) status alone in differentiating patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) from a group of normal control patients, said Fay Probert, PhD, speaking at a poster session at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Not everyone with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) converts to clinically definite MS, and there is large variability in the time to progression, explained Dr. Probert, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of pharmacology at Oxford (England) University, and colleagues. Though the revised McDonald criteria now allow earlier diagnosis of MS, individuals who will be early converters cannot be identified by these criteria, they noted, citing earlier work showing that just over half (52%) of CIS patients who are OCB positive will have clinically definite MS at the 3-year mark.

To see whether combining analysis of multiple proteins and metabolites improved diagnostic accuracy, Dr. Probert and colleagues examined cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples from 41 patients with clinically definite MS, 71 patients with CIS, and 64 control participants without MS. In their analysis, the investigators used nuclear MR metabolomics and a commercially available proteomics assay that identifies and quantifies more than 5,000 proteins.

The multivariate analysis strategy achieved 10-fold external cross-validation of the samples, repeating training and testing of the analysis model while shuffling data. This, explained Dr. Probert and colleagues, “ensures that any discrimination observed cannot have occurred by chance.” Further analysis “identifies the optimal combination of proteomics and metabolomics features which results in the highest diagnostic accuracy.”

Both the nuclear MR metabolomics and the proteomic analyses were able to discriminate between those with clinically definite MS and the control participants, with accuracy of 71% and 75%, respectively.

The levels of seven metabolites present in CSF were predictive of clinically definite MS, compared with non-MS status, independent of OCB status. In fact, noted Dr. Probert and colleagues, “the CSF myoinositol concentration alone diagnosed [clinically definite] MS in this cohort with a specificity of 74% but did not outperform OCB status overall.”

Using the combined omics approach, though, “significantly improved the discrimination” between the non-MS control CSF samples and those of patients with clinically definite MS, wrote Dr. Probert and colleagues. Using a combination of up to five CSF proteins and metabolites yielded accuracy of 85 plus or minus 2%, sensitivity of 85 plus or minus 3%, and specificity of 85 plus or minus 3%. For comparison, using just OCB status provides accuracy of 74%, sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 63%.

Then, Dr. Probert and colleagues turned to the CSF samples from patients with CIS to look for predictors of “fast” (4 years or less) or “slow” (greater than 4 years) conversion to clinically definite MS. “While important for diagnosis, OCB status was not predictive of early conversion,” the investigators noted. However, baseline CSF proteomics analysis alone did differentiate the fast from the slow converters among the CIS subgroup, with an accuracy of 77%.

For patients with CIS who were OCB positive, their baseline metabolite and proteomic profiles were “indistinguishable” from those with clinically definite MS, wrote Dr. Probert and colleagues. The omics analysis was also able to distinguish between OCB-positive CIS patients and the non-MS control patients.

“These results indicate that combined metabolomics and proteomics analysis could not only be used as an adjunct in diagnosis of [clinically definite] MS but could be used as a prognostic test to identify CIS patients at high risk of a second clinical attack within 4 years of onset,” wrote Dr. Probert and coauthors. They noted that the method reported in the poster is the first to offer this prognostic accuracy, but that more work is needed before routine clinical use.

Dr. Probert reported that she had no financial conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported being a consultant to Novartis. Two coauthors reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, including Merck, which partially funded the study. Numares Health, the U.K. Medical Research Council, and the Multiple Sclerosis Society also provided funding support.

SOURCE: Probert F et al. ECTRIMS 2019, Abstract P586.

STOCKHOLM –