User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

Exsanguinating the truth about dragon’s blood in cosmeceuticals

The use of dragon’s blood is renowned among various medical traditions around the world.1,2 It is known to confer anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, antimicrobial, and wound healing benefits, among others. Dragon’s blood and its characteristic red sap has also been used in folk magic and as a coloring substance and varnish.1 In addition, dragon’s blood resin is one of the many botanical agents with roots in traditional medicine that are among the bioactive ingredients used in the booming contemporary Korean cosmeceutical agent market.3.

Many plants, only some have dermatologic properties

Essentially, the moniker “dragon’s blood” describes the deep red resin or sap that has been derived from multiple plant sources – primarily from the genera Daemonorops, Dracaena, Croton, and Pterocarpus – over multiple centuries.2,4 In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), various plants have been used as dragon’s blood, including Butea monosperma, Liquidambar formosana, Daemonorops draco, and, more commonly now, Dracaena cochinchinensis.5

Chemical constituents and activity

Dragon’s blood represents the red exudate culled from 27 species of plants from four families. Among the six Dracaena plants (D. cochinchinensis, D. cambodiana, D. cinnabari, D. draco, D. loureiroi, and D. schizantha) from which dragon’s blood is derived, flavonoids and their oligomers are considered the main active constituents. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, hypolipidemic, hypoglycemic, and cytotoxic activities have been associated with these botanicals.6

D. cochinchinensis is one source of the ethnomedicine “dragon’s blood” that has long been used in TCM. Contemporary studies have shown that the resin of D. cochinchinensis – key constituents of which include loureirin A, loureirin B, loureirin C, cochinchinenin, socotrin-4’-ol, 4’,7-dihydroxyflavan, 4-methylcholest-7-ene-3-ol, ethylparaben, resveratrol, and hydroxyphenol – exhibits antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antidiabetic, and antitumor activities. It has also been shown to support skin repair.4

In 2017, Wang et al. reported that flavonoids from artificially induced dragon’s blood of D. cambodiana showed antibacterial properties.7 The next year, Al Fatimi reported that the dragon’s blood derived from D. cinnabari is a key plant on Yemen’s Socotra Island, where it is used for its antifungal and antioxidant properties to treat various dermal, dental, eye, and gastrointestinal diseases in humans.8Croton lechleri (also one of the plants known as dragon’s blood), a medicinal plant found in the Amazon rainforest and characterized by its red sap, has been shown in preclinical studies to display anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, and antineoplastic activity. Pona et al. note that, while clinical studies of C. lechleri suggest wound healing and antiviral effects, the current use of this plant has limited cutaneous applications.9

Wound healing activity

In 1995, Pieters et al. performed an in vivo study on rats to assess the wound healing activity of dragon’s blood (Croton spp.) from South America. In comparing the effects with those of synthetic proanthocyanidins, the researchers verified the beneficial impact of dragon’s blood in stimulating wound contraction, crust formation, new collagen development, and epithelial layer regeneration. The dragon’s blood component 3’,4-O-dimethylcedrusin was also found to enhance healing by promoting fibroblast and collagen formation, though it was not as effective as crude dragon’s blood. The authors ascribed this effect to the proanthocyanidins in the plant.10

Late in 2003, Jones published a literature review on the evidence related to Croton lechleri (known in South America as “sangre de drago” or dragon’s blood) in support of various biological effects, particularly anti-inflammatory and wound healing capability. The results from multiple in vitro and in vivo investigations buttressed previous ethnomedical justifications for the use of dragon’s blood to treat herpes, insect bites, stomach ulcers, tumors, wounds, and diarrhea, as well as other conditions. Jones added that the sap of the plant has exhibited low toxicity and has been well tolerated in clinical studies.11

In 2012, Hu et al. investigated the impact of dragon’s blood powder with varying grain size on the transdermal absorption and adhesion of ZJHX paste, finding that, with decreasing grain size, penetration of dracorhodin increased, thus promoting transdermal permeability and adhesion.12

Lieu et al. assessed the wound healing potential of Resina Draconis, derived from D. cochinchinensis, which has long been used in traditional medicines by various cultures. In this 2013 evaluation, the investigators substantiated the traditional uses of this herb for wound healing, using excision and incision models in rats. Animals treated with D. cochinchinensis resin displayed significantly superior wound contraction and tensile strength as compared with controls, with histopathological results revealing better microvessel density and growth factor expression levels.13

In 2017, Jiang et al. showed that dracorhodin percolate, derived from dragon’s blood and used extensively to treat wound healing in TCM, accelerated wound healing in Wistar rats.14 A year later, they found that the use of dracorhodin perchlorate was effective in regulating fibroblast proliferation in vitro and in vivo to promote wound healing in rats. In addition, they noted that phosphorylated–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in the wound tissue significantly increased with treatment of dracorhodin perchlorate ointment. The researchers called for clinical trials testing this compound in humans as the next step.15

In 2015, Namjoyan et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 60 patients (between 14 and 65 years old) to assess the wound healing effect of a dragon’s blood cream on skin tag removal. Patients were visited every third day during this 3-week study, after which a significant difference in mean wound healing duration was identified. The investigators attributed the accelerated wound healing action to the phenolic constituents and alkaloid taspine in the resin. They also concluded that dragon’s blood warrants inclusion in the wound healing arsenal, while calling for studies in larger populations.16

Conclusion

The red resin extracts of multiple species of plants have and continue to be identified as “dragon’s blood.” This exudate has been used for various medical indications in traditional medicine for several centuries. Despite this lengthy history, modern research is hardly robust. Nevertheless, there are many credible reports of significant salutary activities associated with these resins and some evidence of cutaneous benefits. Much more research is necessary to determine how useful these ingredients are, despite their present use in a number of marketed cosmeceutical agents.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Gupta D et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008 Feb 12;115(3):361-80.

2. Jura-Morawiec J & Tulik. Chemoecology. 2016;26:101-5.

3. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):155-69.

4. Fan JY et al. Molecules. 2014 Jul 22;19(7):10650-69.

5. Zhang W et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2016 Apr;41(7):1354-7.

6. Sun J et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019 Nov 15;244:112138.

7. Wang H et al. Fitoterapia. 2017 Sep;121:1-5.

8. Al-Fatimi M. Plants (Basel). 2018 Oct 26;7(4):91.

9. Pona A et al. Dermatol Ther. 2019 Mar;32(2):e12786.10. Pieters L et al. Phytomedicine. 1995 Jul;2(1):17-22.

11. Jones K. J Altern Complement Med. 2003 Dec;9(6):877-96.

12. Hu Q et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2012 Dec;37(23):3549-53.

13. Liu H et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:709865.

14. Jiang XW et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017:8950516.

15. Jiang X et al. J Pharmacol Sci. 2018 Feb;136(2):66-72.

16. Namjoyan F et al. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015 Jan 22;6(1):37-40.

The use of dragon’s blood is renowned among various medical traditions around the world.1,2 It is known to confer anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, antimicrobial, and wound healing benefits, among others. Dragon’s blood and its characteristic red sap has also been used in folk magic and as a coloring substance and varnish.1 In addition, dragon’s blood resin is one of the many botanical agents with roots in traditional medicine that are among the bioactive ingredients used in the booming contemporary Korean cosmeceutical agent market.3.

Many plants, only some have dermatologic properties

Essentially, the moniker “dragon’s blood” describes the deep red resin or sap that has been derived from multiple plant sources – primarily from the genera Daemonorops, Dracaena, Croton, and Pterocarpus – over multiple centuries.2,4 In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), various plants have been used as dragon’s blood, including Butea monosperma, Liquidambar formosana, Daemonorops draco, and, more commonly now, Dracaena cochinchinensis.5

Chemical constituents and activity

Dragon’s blood represents the red exudate culled from 27 species of plants from four families. Among the six Dracaena plants (D. cochinchinensis, D. cambodiana, D. cinnabari, D. draco, D. loureiroi, and D. schizantha) from which dragon’s blood is derived, flavonoids and their oligomers are considered the main active constituents. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, hypolipidemic, hypoglycemic, and cytotoxic activities have been associated with these botanicals.6

D. cochinchinensis is one source of the ethnomedicine “dragon’s blood” that has long been used in TCM. Contemporary studies have shown that the resin of D. cochinchinensis – key constituents of which include loureirin A, loureirin B, loureirin C, cochinchinenin, socotrin-4’-ol, 4’,7-dihydroxyflavan, 4-methylcholest-7-ene-3-ol, ethylparaben, resveratrol, and hydroxyphenol – exhibits antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antidiabetic, and antitumor activities. It has also been shown to support skin repair.4

In 2017, Wang et al. reported that flavonoids from artificially induced dragon’s blood of D. cambodiana showed antibacterial properties.7 The next year, Al Fatimi reported that the dragon’s blood derived from D. cinnabari is a key plant on Yemen’s Socotra Island, where it is used for its antifungal and antioxidant properties to treat various dermal, dental, eye, and gastrointestinal diseases in humans.8Croton lechleri (also one of the plants known as dragon’s blood), a medicinal plant found in the Amazon rainforest and characterized by its red sap, has been shown in preclinical studies to display anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, and antineoplastic activity. Pona et al. note that, while clinical studies of C. lechleri suggest wound healing and antiviral effects, the current use of this plant has limited cutaneous applications.9

Wound healing activity

In 1995, Pieters et al. performed an in vivo study on rats to assess the wound healing activity of dragon’s blood (Croton spp.) from South America. In comparing the effects with those of synthetic proanthocyanidins, the researchers verified the beneficial impact of dragon’s blood in stimulating wound contraction, crust formation, new collagen development, and epithelial layer regeneration. The dragon’s blood component 3’,4-O-dimethylcedrusin was also found to enhance healing by promoting fibroblast and collagen formation, though it was not as effective as crude dragon’s blood. The authors ascribed this effect to the proanthocyanidins in the plant.10

Late in 2003, Jones published a literature review on the evidence related to Croton lechleri (known in South America as “sangre de drago” or dragon’s blood) in support of various biological effects, particularly anti-inflammatory and wound healing capability. The results from multiple in vitro and in vivo investigations buttressed previous ethnomedical justifications for the use of dragon’s blood to treat herpes, insect bites, stomach ulcers, tumors, wounds, and diarrhea, as well as other conditions. Jones added that the sap of the plant has exhibited low toxicity and has been well tolerated in clinical studies.11

In 2012, Hu et al. investigated the impact of dragon’s blood powder with varying grain size on the transdermal absorption and adhesion of ZJHX paste, finding that, with decreasing grain size, penetration of dracorhodin increased, thus promoting transdermal permeability and adhesion.12

Lieu et al. assessed the wound healing potential of Resina Draconis, derived from D. cochinchinensis, which has long been used in traditional medicines by various cultures. In this 2013 evaluation, the investigators substantiated the traditional uses of this herb for wound healing, using excision and incision models in rats. Animals treated with D. cochinchinensis resin displayed significantly superior wound contraction and tensile strength as compared with controls, with histopathological results revealing better microvessel density and growth factor expression levels.13

In 2017, Jiang et al. showed that dracorhodin percolate, derived from dragon’s blood and used extensively to treat wound healing in TCM, accelerated wound healing in Wistar rats.14 A year later, they found that the use of dracorhodin perchlorate was effective in regulating fibroblast proliferation in vitro and in vivo to promote wound healing in rats. In addition, they noted that phosphorylated–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in the wound tissue significantly increased with treatment of dracorhodin perchlorate ointment. The researchers called for clinical trials testing this compound in humans as the next step.15

In 2015, Namjoyan et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 60 patients (between 14 and 65 years old) to assess the wound healing effect of a dragon’s blood cream on skin tag removal. Patients were visited every third day during this 3-week study, after which a significant difference in mean wound healing duration was identified. The investigators attributed the accelerated wound healing action to the phenolic constituents and alkaloid taspine in the resin. They also concluded that dragon’s blood warrants inclusion in the wound healing arsenal, while calling for studies in larger populations.16

Conclusion

The red resin extracts of multiple species of plants have and continue to be identified as “dragon’s blood.” This exudate has been used for various medical indications in traditional medicine for several centuries. Despite this lengthy history, modern research is hardly robust. Nevertheless, there are many credible reports of significant salutary activities associated with these resins and some evidence of cutaneous benefits. Much more research is necessary to determine how useful these ingredients are, despite their present use in a number of marketed cosmeceutical agents.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Gupta D et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008 Feb 12;115(3):361-80.

2. Jura-Morawiec J & Tulik. Chemoecology. 2016;26:101-5.

3. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):155-69.

4. Fan JY et al. Molecules. 2014 Jul 22;19(7):10650-69.

5. Zhang W et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2016 Apr;41(7):1354-7.

6. Sun J et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019 Nov 15;244:112138.

7. Wang H et al. Fitoterapia. 2017 Sep;121:1-5.

8. Al-Fatimi M. Plants (Basel). 2018 Oct 26;7(4):91.

9. Pona A et al. Dermatol Ther. 2019 Mar;32(2):e12786.10. Pieters L et al. Phytomedicine. 1995 Jul;2(1):17-22.

11. Jones K. J Altern Complement Med. 2003 Dec;9(6):877-96.

12. Hu Q et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2012 Dec;37(23):3549-53.

13. Liu H et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:709865.

14. Jiang XW et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017:8950516.

15. Jiang X et al. J Pharmacol Sci. 2018 Feb;136(2):66-72.

16. Namjoyan F et al. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015 Jan 22;6(1):37-40.

The use of dragon’s blood is renowned among various medical traditions around the world.1,2 It is known to confer anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, antimicrobial, and wound healing benefits, among others. Dragon’s blood and its characteristic red sap has also been used in folk magic and as a coloring substance and varnish.1 In addition, dragon’s blood resin is one of the many botanical agents with roots in traditional medicine that are among the bioactive ingredients used in the booming contemporary Korean cosmeceutical agent market.3.

Many plants, only some have dermatologic properties

Essentially, the moniker “dragon’s blood” describes the deep red resin or sap that has been derived from multiple plant sources – primarily from the genera Daemonorops, Dracaena, Croton, and Pterocarpus – over multiple centuries.2,4 In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), various plants have been used as dragon’s blood, including Butea monosperma, Liquidambar formosana, Daemonorops draco, and, more commonly now, Dracaena cochinchinensis.5

Chemical constituents and activity

Dragon’s blood represents the red exudate culled from 27 species of plants from four families. Among the six Dracaena plants (D. cochinchinensis, D. cambodiana, D. cinnabari, D. draco, D. loureiroi, and D. schizantha) from which dragon’s blood is derived, flavonoids and their oligomers are considered the main active constituents. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, hypolipidemic, hypoglycemic, and cytotoxic activities have been associated with these botanicals.6

D. cochinchinensis is one source of the ethnomedicine “dragon’s blood” that has long been used in TCM. Contemporary studies have shown that the resin of D. cochinchinensis – key constituents of which include loureirin A, loureirin B, loureirin C, cochinchinenin, socotrin-4’-ol, 4’,7-dihydroxyflavan, 4-methylcholest-7-ene-3-ol, ethylparaben, resveratrol, and hydroxyphenol – exhibits antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antidiabetic, and antitumor activities. It has also been shown to support skin repair.4

In 2017, Wang et al. reported that flavonoids from artificially induced dragon’s blood of D. cambodiana showed antibacterial properties.7 The next year, Al Fatimi reported that the dragon’s blood derived from D. cinnabari is a key plant on Yemen’s Socotra Island, where it is used for its antifungal and antioxidant properties to treat various dermal, dental, eye, and gastrointestinal diseases in humans.8Croton lechleri (also one of the plants known as dragon’s blood), a medicinal plant found in the Amazon rainforest and characterized by its red sap, has been shown in preclinical studies to display anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, and antineoplastic activity. Pona et al. note that, while clinical studies of C. lechleri suggest wound healing and antiviral effects, the current use of this plant has limited cutaneous applications.9

Wound healing activity

In 1995, Pieters et al. performed an in vivo study on rats to assess the wound healing activity of dragon’s blood (Croton spp.) from South America. In comparing the effects with those of synthetic proanthocyanidins, the researchers verified the beneficial impact of dragon’s blood in stimulating wound contraction, crust formation, new collagen development, and epithelial layer regeneration. The dragon’s blood component 3’,4-O-dimethylcedrusin was also found to enhance healing by promoting fibroblast and collagen formation, though it was not as effective as crude dragon’s blood. The authors ascribed this effect to the proanthocyanidins in the plant.10

Late in 2003, Jones published a literature review on the evidence related to Croton lechleri (known in South America as “sangre de drago” or dragon’s blood) in support of various biological effects, particularly anti-inflammatory and wound healing capability. The results from multiple in vitro and in vivo investigations buttressed previous ethnomedical justifications for the use of dragon’s blood to treat herpes, insect bites, stomach ulcers, tumors, wounds, and diarrhea, as well as other conditions. Jones added that the sap of the plant has exhibited low toxicity and has been well tolerated in clinical studies.11

In 2012, Hu et al. investigated the impact of dragon’s blood powder with varying grain size on the transdermal absorption and adhesion of ZJHX paste, finding that, with decreasing grain size, penetration of dracorhodin increased, thus promoting transdermal permeability and adhesion.12

Lieu et al. assessed the wound healing potential of Resina Draconis, derived from D. cochinchinensis, which has long been used in traditional medicines by various cultures. In this 2013 evaluation, the investigators substantiated the traditional uses of this herb for wound healing, using excision and incision models in rats. Animals treated with D. cochinchinensis resin displayed significantly superior wound contraction and tensile strength as compared with controls, with histopathological results revealing better microvessel density and growth factor expression levels.13

In 2017, Jiang et al. showed that dracorhodin percolate, derived from dragon’s blood and used extensively to treat wound healing in TCM, accelerated wound healing in Wistar rats.14 A year later, they found that the use of dracorhodin perchlorate was effective in regulating fibroblast proliferation in vitro and in vivo to promote wound healing in rats. In addition, they noted that phosphorylated–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in the wound tissue significantly increased with treatment of dracorhodin perchlorate ointment. The researchers called for clinical trials testing this compound in humans as the next step.15

In 2015, Namjoyan et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in 60 patients (between 14 and 65 years old) to assess the wound healing effect of a dragon’s blood cream on skin tag removal. Patients were visited every third day during this 3-week study, after which a significant difference in mean wound healing duration was identified. The investigators attributed the accelerated wound healing action to the phenolic constituents and alkaloid taspine in the resin. They also concluded that dragon’s blood warrants inclusion in the wound healing arsenal, while calling for studies in larger populations.16

Conclusion

The red resin extracts of multiple species of plants have and continue to be identified as “dragon’s blood.” This exudate has been used for various medical indications in traditional medicine for several centuries. Despite this lengthy history, modern research is hardly robust. Nevertheless, there are many credible reports of significant salutary activities associated with these resins and some evidence of cutaneous benefits. Much more research is necessary to determine how useful these ingredients are, despite their present use in a number of marketed cosmeceutical agents.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Gupta D et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008 Feb 12;115(3):361-80.

2. Jura-Morawiec J & Tulik. Chemoecology. 2016;26:101-5.

3. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):155-69.

4. Fan JY et al. Molecules. 2014 Jul 22;19(7):10650-69.

5. Zhang W et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2016 Apr;41(7):1354-7.

6. Sun J et al. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019 Nov 15;244:112138.

7. Wang H et al. Fitoterapia. 2017 Sep;121:1-5.

8. Al-Fatimi M. Plants (Basel). 2018 Oct 26;7(4):91.

9. Pona A et al. Dermatol Ther. 2019 Mar;32(2):e12786.10. Pieters L et al. Phytomedicine. 1995 Jul;2(1):17-22.

11. Jones K. J Altern Complement Med. 2003 Dec;9(6):877-96.

12. Hu Q et al. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2012 Dec;37(23):3549-53.

13. Liu H et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:709865.

14. Jiang XW et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017:8950516.

15. Jiang X et al. J Pharmacol Sci. 2018 Feb;136(2):66-72.

16. Namjoyan F et al. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015 Jan 22;6(1):37-40.

What’s under my toenail?

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

A 13-year-old female was seen by her pediatrician for a lesion that had been on her right toe for about 6 months. She is unaware of any trauma to the area. The lesion has been growing slowly and recently it started lifting up the nail, became tender, and was bleeding, which is the reason why she sought care.

At the pediatrician's office, he noted a pink crusted papule under the nail. The nail was lifting up and was tender to the touch. She is a healthy girl who is not taking any medications and has no allergies. There is no family history of similar lesions.

The pediatrician took a picture of the lesion and he send it to our pediatric teledermatology service for consultation.

Shedding the super-doctor myth requires an honest look at systemic racism

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

An overwhelmingly loud and high-pitched screech rattles against your hip. You startle and groan into the pillow as your thoughts settle into conscious awareness. It is 3 a.m. You are a 2nd-year resident trudging through the night shift, alerted to the presence of a new patient awaiting an emergency assessment. You are the only in-house physician. Walking steadfastly toward the emergency unit, you enter and greet the patient. Immediately, you observe a look of surprise followed immediately by a scowl.

You extend a hand, but your greeting is abruptly cut short with: “I want to see a doctor!” You pace your breaths to quell annoyance and resume your introduction, asserting that you are a doctor and indeed the only doctor on duty. After moments of deep sighs and questions regarding your credentials, you persuade the patient to start the interview.

It is now 8 a.m. The frustration of the night starts to ease as you prepare to leave. While gathering your things, a visitor is overheard inquiring the whereabouts of a hospital unit. Volunteering as a guide, you walk the person toward the opposite end of the hospital. Bleary eyed, muscle laxed, and bone weary, you point out the entrance, then turn to leave. The steady rhythm of your steps suddenly halts as you hear from behind: “Thank you! You speak English really well!” Blankly, you stare. Your voice remains mute while your brain screams: “What is that supposed to mean?” But you do not utter a sound, because intuitively, you know the answer.

While reading this scenario, what did you feel? Pride in knowing that the physician was able to successfully navigate a busy night? Relief in the physician’s ability to maintain a professional demeanor despite belittling microaggressions? Are you angry? Would you replay those moments like reruns of a bad TV show? Can you imagine entering your home and collapsing onto the bed as your tears of fury pool over your rumpled sheets?

The emotional release of that morning is seared into my memory. Over the years, I questioned my reactions. Was I too passive? Should I have schooled them on their ignorance? Had I done so, would I have incurred reprimands? Would standing up for myself cause years of hard work to fall away? Moreover, had I defended myself, would I forever have been viewed as “The Angry Black Woman?”

This story is more than a vignette. For me, it is another reminder that, despite how far we have come, we have much further to go. As a Black woman in a professional sphere, I stand upon the shoulders of those who sacrificed for a dream, a greater purpose. My foremothers and forefathers fought bravely and tirelessly so that we could attain levels of success that were only once but a dream. Despite this progress, a grimace, carelessly spoken words, or a mindless gesture remind me that, no matter how much I toil and what levels of success I achieve, when I meet someone for the first time or encounter someone from my past, I find myself wondering whether I am remembered for me or because I am “The Black One.”

Honest look at medicine is imperative

It is important to consider multiple facets of the super-doctor myth. We are dedicated, fearless, authoritative, ambitious individuals. We do not yield to sickness, family obligations, or fatigue. Medicine is a calling, and the patient deserves the utmost respect and professional behavior. Impervious to ethnicity, race, nationality, or creed, we are unbiased and always in service of the greater good. Often, however, I wonder how the expectations of patient-focused, patient-centered care can prevail without an honest look at the vicissitudes facing medicine.

We find ourselves amid a tumultuous year overshadowed by a devastating pandemic that skews heavily toward Black and Brown communities, in addition to political turmoil and racial reckoning that sprang forth from fear, anger, and determination ignited by the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – communities united in outrage lamenting the cries of Black Lives Matter.

I remember the tears briskly falling upon my blouse as I watched Mr. Floyd’s life violently ripped from this Earth. Shortly thereafter, I remember the phone calls, emails, and texts from close friends, acquaintances, and colleagues offering support, listening ears, pledging to learn and endeavoring to understand the struggle for recognition and the fight for human rights. Even so, the deafening support was clouded by the preternatural silence of some medical organizations. Within the Black physician community, outrage was palpable. We reflected upon years of sacrifice and perseverance despite the challenge of bigotry, ignorance, and racism – not only from patients and their families – but also colleagues and administrators. Yet, in our time of horror and need, in those moments of vulnerability ... silence. Eventually, lengthy proclamations of support were expressed through various media. However, it felt too safe, too corporate, and too generic and inauthentic. As a result, an exodus of Black physicians from leadership positions and academic medicine took hold as the blatant continuation of rhetoric – coupled with ineffective outreach and support – finally took its toll.

Frequently, I question how the obstacles of medical school, residency, and beyond are expected to be traversed while living in a world that consistently affords additional challenges to those who look, act, or speak in a manner that varies from the perceived standard. In a culture where the myth of the super doctor reigns, how do we reconcile attainment of a false and detrimental narrative while the overarching pressure acutely felt by Black physicians magnifies in the setting of stereotypes, sociopolitical turbulence, bigotry, and racism? How can one sacrifice for an entity that is unwilling to acknowledge the psychological implications of that sacrifice?

For instance, while in medical school, I transitioned my hair to its natural state but was counseled against doing so because of the risk of losing residency opportunities as a direct result of my “unprofessional” appearance. Throughout residency, multiple incidents come to mind, including frequent demands to see my hospital badge despite the same not being of asked of my White cohorts; denial of entry into physician entrance within the residency building because, despite my professional attire, I was presumed to be a member of the custodial staff; and patients being confused and asking for a doctor despite my long white coat and clear introductions.

Furthermore, the fluency of my speech and the absence of regional dialect or vernacular are quite often lauded by patients. Inquiries to touch my hair as well as hypotheses regarding my nationality or degree of “blackness” with respect to the shape of my nose, eyes, and lips are openly questioned. Unfortunately, those uncomfortable incidents have not been limited to patient encounters.

In one instance, while presenting a patient in the presence of my attending and a 3rd-year medical student, I was sternly admonished for disclosing the race of the patient. I sat still and resolute as this doctor spoke on increased risk of bias in diagnosis and treatment when race is identified. Outwardly, I projected patience but inside, I seethed. In that moment, I realized that I would never have the luxury of ignorance or denial. Although I desire to be valued for my prowess in medicine, the mythical status was not created with my skin color in mind. For is avoidance not but a reflection of denial?

In these chaotic and uncertain times, how can we continue to promote a pathological ideal when the roads traveled are so fundamentally skewed? If a White physician faces a belligerent and argumentative patient, there is opportunity for debriefing both individually and among a larger cohort via classes, conferences, and supervisions. Conversely, when a Black physician is derided with racist sentiment, will they have the same opportunity for reflection and support? Despite identical expectations of professionalism and growth, how can one be successful in a system that either directly or indirectly encourages the opposite?

As we try to shed the super-doctor myth, we must recognize that this unattainable and detrimental persona hinders progress. This myth undermines our ability to understand our fragility, the limitations of our capabilities, and the strength of our vulnerability. We must take an honest look at the manner in which our individual biases and the deeply ingrained (and potentially unconscious) systemic biases are counterintuitive to the success and support of physicians of color.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

Outstanding medical bills: Dealing with deadbeats

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I have received a growing number of inquiries about collection issues. For a variety of reasons, many patients seem increasingly reluctant to pay their medical bills. I’ve written many columns on keeping credit card numbers on file, and other techniques for keeping your accounts receivable in check; but despite your best efforts, there will always be a few deadbeats that you will need to pursue.

For the record, I am not speaking about patients who lost income due to the pandemic and are now struggling with debts, or otherwise have fallen on hard times and are unable to pay.

The worst kinds of deadbeats are the ones who rob you twice; they accept payments from insurance companies and keep them. Such crooks must be pursued aggressively, with all the means at your disposal; but to reiterate the point I’ve tried to drive home repeatedly, the best cure is prevention.

You already know that you should collect as many fees as possible at the time of service. For cosmetic procedures you should require a substantial deposit in advance, with the balance due at the time of service. When that is impossible, maximize the chances you will be paid by making sure all available payment mechanisms are in place.

With my credit-card-on-file system that I’ve described many times, patients who fail to pay their credit card bill are the credit card company’s problem, not yours. In cases where you suspect fees might exceed credit card limits, you can arrange a realistic payment schedule in advance and have the patient fill out a credit application. You can find forms for this online at formswift.com, templates.office.com, and many other websites.

In some cases, it may be worth the trouble to run a background check. There are easy and affordable ways to do this. Dunn & Bradstreet, for example, will furnish a report containing payment records and details of any lawsuits, liens, and other legal actions for a nominal fee. The more financial information you have on file, the more leverage you have if a patient later balks at paying his or her balance.

For cosmetic work, always take before and after photos, and have all patients sign a written consent giving permission for the procedure, assuming full financial responsibility, and acknowledging that no guarantees have been given or implied. This defuses the common deadbeat tactics of claiming ignorance of personal financial obligations and professing dissatisfaction with the results.

Despite all your precautions, a deadbeat will inevitably slip through on occasion; but even then, you have options for extracting payment. Collection agencies are the traditional first line of attack for most medical practices. Ideally, your agency should specialize in handling medical accounts, so it will know exactly how much pressure to exert to avoid charges of harassment. Delinquent accounts should be submitted earlier rather than later to maximize the chances of success; my manager never allows an account to age more than 90 days, and if circumstances dictate, she refers them sooner than that.

When collection agencies fail, think about small claims court. You will need to learn the rules in your state, but in most states there is a small filing fee and a limit of $5,000 or so on claims. No attorneys are involved. If your paperwork is in order, the court will nearly always rule in your favor, but it will not provide the means for actual collection. In other words, you will still have to persuade the deadbeat to pay up. However, in many states a court order will give you the authority to attach a lien to property, or garnish wages, which often provides enough leverage to force payment.

What about those double-deadbeats who keep the insurance checks for themselves? First, check your third-party contract; sometimes the insurance company or HMO will be compelled to pay you directly and then go after the patient to get back its money. (They won’t volunteer this service, however – you’ll have to ask for it.)

If that’s not an option, consider reporting the misdirected payment to the Internal Revenue Service as income to the patient, by submitting a 1099 Miscellaneous Income form. Be sure to notify the deadbeat that you will be doing this. Sometimes the threat of such action will convince the individual to pay up; if not, at least you’ll have the satisfaction of knowing he or she will have to pay taxes on the money.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I have received a growing number of inquiries about collection issues. For a variety of reasons, many patients seem increasingly reluctant to pay their medical bills. I’ve written many columns on keeping credit card numbers on file, and other techniques for keeping your accounts receivable in check; but despite your best efforts, there will always be a few deadbeats that you will need to pursue.

For the record, I am not speaking about patients who lost income due to the pandemic and are now struggling with debts, or otherwise have fallen on hard times and are unable to pay.

The worst kinds of deadbeats are the ones who rob you twice; they accept payments from insurance companies and keep them. Such crooks must be pursued aggressively, with all the means at your disposal; but to reiterate the point I’ve tried to drive home repeatedly, the best cure is prevention.

You already know that you should collect as many fees as possible at the time of service. For cosmetic procedures you should require a substantial deposit in advance, with the balance due at the time of service. When that is impossible, maximize the chances you will be paid by making sure all available payment mechanisms are in place.

With my credit-card-on-file system that I’ve described many times, patients who fail to pay their credit card bill are the credit card company’s problem, not yours. In cases where you suspect fees might exceed credit card limits, you can arrange a realistic payment schedule in advance and have the patient fill out a credit application. You can find forms for this online at formswift.com, templates.office.com, and many other websites.

In some cases, it may be worth the trouble to run a background check. There are easy and affordable ways to do this. Dunn & Bradstreet, for example, will furnish a report containing payment records and details of any lawsuits, liens, and other legal actions for a nominal fee. The more financial information you have on file, the more leverage you have if a patient later balks at paying his or her balance.

For cosmetic work, always take before and after photos, and have all patients sign a written consent giving permission for the procedure, assuming full financial responsibility, and acknowledging that no guarantees have been given or implied. This defuses the common deadbeat tactics of claiming ignorance of personal financial obligations and professing dissatisfaction with the results.

Despite all your precautions, a deadbeat will inevitably slip through on occasion; but even then, you have options for extracting payment. Collection agencies are the traditional first line of attack for most medical practices. Ideally, your agency should specialize in handling medical accounts, so it will know exactly how much pressure to exert to avoid charges of harassment. Delinquent accounts should be submitted earlier rather than later to maximize the chances of success; my manager never allows an account to age more than 90 days, and if circumstances dictate, she refers them sooner than that.

When collection agencies fail, think about small claims court. You will need to learn the rules in your state, but in most states there is a small filing fee and a limit of $5,000 or so on claims. No attorneys are involved. If your paperwork is in order, the court will nearly always rule in your favor, but it will not provide the means for actual collection. In other words, you will still have to persuade the deadbeat to pay up. However, in many states a court order will give you the authority to attach a lien to property, or garnish wages, which often provides enough leverage to force payment.

What about those double-deadbeats who keep the insurance checks for themselves? First, check your third-party contract; sometimes the insurance company or HMO will be compelled to pay you directly and then go after the patient to get back its money. (They won’t volunteer this service, however – you’ll have to ask for it.)

If that’s not an option, consider reporting the misdirected payment to the Internal Revenue Service as income to the patient, by submitting a 1099 Miscellaneous Income form. Be sure to notify the deadbeat that you will be doing this. Sometimes the threat of such action will convince the individual to pay up; if not, at least you’ll have the satisfaction of knowing he or she will have to pay taxes on the money.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, I have received a growing number of inquiries about collection issues. For a variety of reasons, many patients seem increasingly reluctant to pay their medical bills. I’ve written many columns on keeping credit card numbers on file, and other techniques for keeping your accounts receivable in check; but despite your best efforts, there will always be a few deadbeats that you will need to pursue.

For the record, I am not speaking about patients who lost income due to the pandemic and are now struggling with debts, or otherwise have fallen on hard times and are unable to pay.

The worst kinds of deadbeats are the ones who rob you twice; they accept payments from insurance companies and keep them. Such crooks must be pursued aggressively, with all the means at your disposal; but to reiterate the point I’ve tried to drive home repeatedly, the best cure is prevention.

You already know that you should collect as many fees as possible at the time of service. For cosmetic procedures you should require a substantial deposit in advance, with the balance due at the time of service. When that is impossible, maximize the chances you will be paid by making sure all available payment mechanisms are in place.

With my credit-card-on-file system that I’ve described many times, patients who fail to pay their credit card bill are the credit card company’s problem, not yours. In cases where you suspect fees might exceed credit card limits, you can arrange a realistic payment schedule in advance and have the patient fill out a credit application. You can find forms for this online at formswift.com, templates.office.com, and many other websites.

In some cases, it may be worth the trouble to run a background check. There are easy and affordable ways to do this. Dunn & Bradstreet, for example, will furnish a report containing payment records and details of any lawsuits, liens, and other legal actions for a nominal fee. The more financial information you have on file, the more leverage you have if a patient later balks at paying his or her balance.

For cosmetic work, always take before and after photos, and have all patients sign a written consent giving permission for the procedure, assuming full financial responsibility, and acknowledging that no guarantees have been given or implied. This defuses the common deadbeat tactics of claiming ignorance of personal financial obligations and professing dissatisfaction with the results.

Despite all your precautions, a deadbeat will inevitably slip through on occasion; but even then, you have options for extracting payment. Collection agencies are the traditional first line of attack for most medical practices. Ideally, your agency should specialize in handling medical accounts, so it will know exactly how much pressure to exert to avoid charges of harassment. Delinquent accounts should be submitted earlier rather than later to maximize the chances of success; my manager never allows an account to age more than 90 days, and if circumstances dictate, she refers them sooner than that.

When collection agencies fail, think about small claims court. You will need to learn the rules in your state, but in most states there is a small filing fee and a limit of $5,000 or so on claims. No attorneys are involved. If your paperwork is in order, the court will nearly always rule in your favor, but it will not provide the means for actual collection. In other words, you will still have to persuade the deadbeat to pay up. However, in many states a court order will give you the authority to attach a lien to property, or garnish wages, which often provides enough leverage to force payment.

What about those double-deadbeats who keep the insurance checks for themselves? First, check your third-party contract; sometimes the insurance company or HMO will be compelled to pay you directly and then go after the patient to get back its money. (They won’t volunteer this service, however – you’ll have to ask for it.)

If that’s not an option, consider reporting the misdirected payment to the Internal Revenue Service as income to the patient, by submitting a 1099 Miscellaneous Income form. Be sure to notify the deadbeat that you will be doing this. Sometimes the threat of such action will convince the individual to pay up; if not, at least you’ll have the satisfaction of knowing he or she will have to pay taxes on the money.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

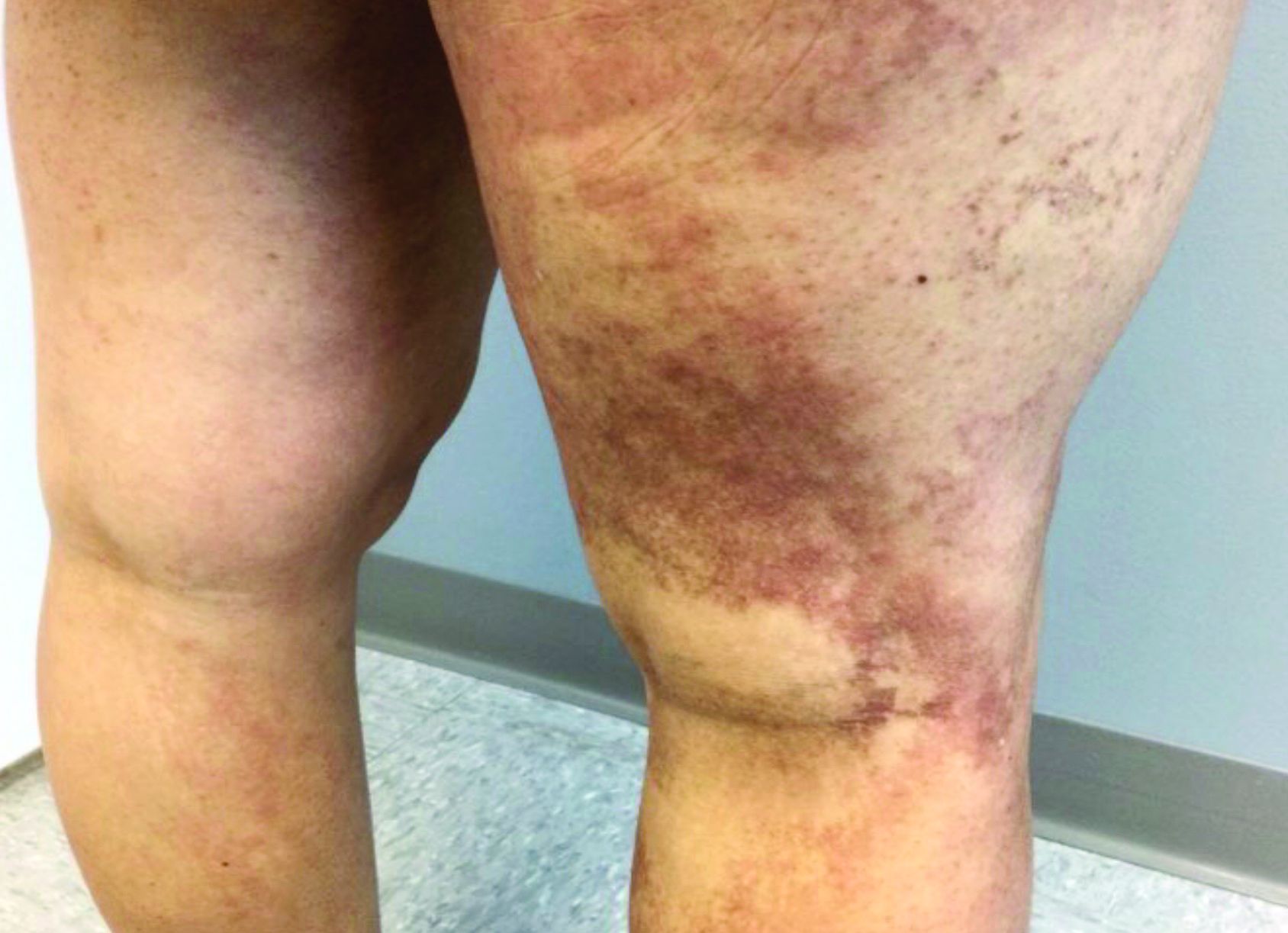

A 35-year-old with erythematous, dusky patches on both lower extremities