User login

News and Views that Matter to Physicians

Covered-stent TIPS tops large-volume paracentesis for cirrhosis survival

One-year survival without liver transplant was far more likely when transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) with covered stents were used to treat cirrhosis with recurrent ascites, instead of ongoing large-volume paracenteses with albumin, in a 62-patient randomized trial from France.

“TIPS with covered stents ... should therefore be preferred to LVP [large-volume paracenteses] with volume expansion... These findings support TIPS as the first-line intervention,” said investigators led by gastroenterologist Christophe Bureau, MD, of Toulouse (France) University in the January issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.016).

All 62 patients had at least two LVPs prior to the study; 29 were then randomized to covered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and 33 to LVP and albumin as needed. All the patients were on a low-salt diet.

Twenty-seven TIPS patients (93%) were alive without a liver transplant at 1 year, versus 17 (52%) in the LVP group (P = .003). TIPS patients had a total of 32 paracenteses in the first year, versus 320 in the LVP group. Six paracentesis patients (18%) had portal hypertension–related bleeding, and six had hernia-related complications; none of the TIPS patients had either. LVP patients spent a mean of 35 days in the hospital, versus 17 days for the TIPS group (P = .04). The probability of remaining free of encephalopathy at 1 year was the same in both groups, at 65%.

It has been shown before that TIPS has the edge on LVP for reducing recurrence of tense ascites. However, early studies used uncovered stents and, due to their almost 80% risk of dysfunction, they did not show a significant benefit for survival. As a result, repeated paracenteses have been recommended as first-line treatment, with TIPS held in reserve for patients who need very frequent LVP.

Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents appear to have changed the equation, “owing to a substantial decrease in the rate of shunt dysfunction,” the investigators said.

The French results are a bit better than previous reports of covered TIPS. “This could be related to greater experience with the TIPS procedure;” there were no technical failures. The study also mostly included patients younger than 65 years with Child-Pugh class B disease and no prior encephalopathy – favorable factors that also may have contributed to the results. However, “we believe that the use of covered stents was the main determinant of the observed improvement in outcomes... TIPS with uncovered stent[s] should not be considered effective or recommended any longer for the long-term treatment of” portal hypertension, they said.

Cirrhosis in the trial was due almost entirely to alcohol abuse. About three-quarters of both groups reported abstinence while enrolled. The mean age was 56 years, and the majority of subjects were men.

The work was funded by the French Ministry of Health and supported by Gore, maker of the covered stent used in the study. Dr. Bureau and another author are Gore consultants.

One-year survival without liver transplant was far more likely when transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) with covered stents were used to treat cirrhosis with recurrent ascites, instead of ongoing large-volume paracenteses with albumin, in a 62-patient randomized trial from France.

“TIPS with covered stents ... should therefore be preferred to LVP [large-volume paracenteses] with volume expansion... These findings support TIPS as the first-line intervention,” said investigators led by gastroenterologist Christophe Bureau, MD, of Toulouse (France) University in the January issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.016).

All 62 patients had at least two LVPs prior to the study; 29 were then randomized to covered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and 33 to LVP and albumin as needed. All the patients were on a low-salt diet.

Twenty-seven TIPS patients (93%) were alive without a liver transplant at 1 year, versus 17 (52%) in the LVP group (P = .003). TIPS patients had a total of 32 paracenteses in the first year, versus 320 in the LVP group. Six paracentesis patients (18%) had portal hypertension–related bleeding, and six had hernia-related complications; none of the TIPS patients had either. LVP patients spent a mean of 35 days in the hospital, versus 17 days for the TIPS group (P = .04). The probability of remaining free of encephalopathy at 1 year was the same in both groups, at 65%.

It has been shown before that TIPS has the edge on LVP for reducing recurrence of tense ascites. However, early studies used uncovered stents and, due to their almost 80% risk of dysfunction, they did not show a significant benefit for survival. As a result, repeated paracenteses have been recommended as first-line treatment, with TIPS held in reserve for patients who need very frequent LVP.

Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents appear to have changed the equation, “owing to a substantial decrease in the rate of shunt dysfunction,” the investigators said.

The French results are a bit better than previous reports of covered TIPS. “This could be related to greater experience with the TIPS procedure;” there were no technical failures. The study also mostly included patients younger than 65 years with Child-Pugh class B disease and no prior encephalopathy – favorable factors that also may have contributed to the results. However, “we believe that the use of covered stents was the main determinant of the observed improvement in outcomes... TIPS with uncovered stent[s] should not be considered effective or recommended any longer for the long-term treatment of” portal hypertension, they said.

Cirrhosis in the trial was due almost entirely to alcohol abuse. About three-quarters of both groups reported abstinence while enrolled. The mean age was 56 years, and the majority of subjects were men.

The work was funded by the French Ministry of Health and supported by Gore, maker of the covered stent used in the study. Dr. Bureau and another author are Gore consultants.

One-year survival without liver transplant was far more likely when transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) with covered stents were used to treat cirrhosis with recurrent ascites, instead of ongoing large-volume paracenteses with albumin, in a 62-patient randomized trial from France.

“TIPS with covered stents ... should therefore be preferred to LVP [large-volume paracenteses] with volume expansion... These findings support TIPS as the first-line intervention,” said investigators led by gastroenterologist Christophe Bureau, MD, of Toulouse (France) University in the January issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.016).

All 62 patients had at least two LVPs prior to the study; 29 were then randomized to covered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and 33 to LVP and albumin as needed. All the patients were on a low-salt diet.

Twenty-seven TIPS patients (93%) were alive without a liver transplant at 1 year, versus 17 (52%) in the LVP group (P = .003). TIPS patients had a total of 32 paracenteses in the first year, versus 320 in the LVP group. Six paracentesis patients (18%) had portal hypertension–related bleeding, and six had hernia-related complications; none of the TIPS patients had either. LVP patients spent a mean of 35 days in the hospital, versus 17 days for the TIPS group (P = .04). The probability of remaining free of encephalopathy at 1 year was the same in both groups, at 65%.

It has been shown before that TIPS has the edge on LVP for reducing recurrence of tense ascites. However, early studies used uncovered stents and, due to their almost 80% risk of dysfunction, they did not show a significant benefit for survival. As a result, repeated paracenteses have been recommended as first-line treatment, with TIPS held in reserve for patients who need very frequent LVP.

Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents appear to have changed the equation, “owing to a substantial decrease in the rate of shunt dysfunction,” the investigators said.

The French results are a bit better than previous reports of covered TIPS. “This could be related to greater experience with the TIPS procedure;” there were no technical failures. The study also mostly included patients younger than 65 years with Child-Pugh class B disease and no prior encephalopathy – favorable factors that also may have contributed to the results. However, “we believe that the use of covered stents was the main determinant of the observed improvement in outcomes... TIPS with uncovered stent[s] should not be considered effective or recommended any longer for the long-term treatment of” portal hypertension, they said.

Cirrhosis in the trial was due almost entirely to alcohol abuse. About three-quarters of both groups reported abstinence while enrolled. The mean age was 56 years, and the majority of subjects were men.

The work was funded by the French Ministry of Health and supported by Gore, maker of the covered stent used in the study. Dr. Bureau and another author are Gore consultants.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Twenty-seven TIPS patients (93%) were alive without a liver transplant at 1 year, versus 17 (52%) in the LVP group (P = .003).

Data source: Randomized trial with 62 patients.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the French Ministry of Health and supported by Gore, maker of the covered stent used in the study. The lead and one other investigator are Gore consultants.

Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, pain lead health spending

Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and back and neck pain are the top three conditions accounting for the highest spending on personal health care in the United States, according to a report published online Dec. 27 in JAMA.

In addition, spending on pharmaceuticals – particularly diabetes therapies, antihypertensive drugs, and medications for hyperlipidemia – drove much of the massive increase in health care spending during the past 2 decades, said Joseph L. Dieleman, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

Recent increases in health care spending are well documented, but less is known about what is spent for individual conditions, in different health care settings, and in various patient age groups. To assess health care spending across these categories, the investigators collected and analyzed data for 1996 through 2013 from nationally representative surveys of households, nationally representative surveys of medical facilities, insurance claims, government budgets, and other official records.

They grouped the data into six type-of-care categories: inpatient care, ambulatory care, emergency department care, nursing facility care, dental care, and prescribed pharmaceuticals. “Spending on the six types of personal health care was then disaggregated across 155 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive conditions and 38 age and sex groups,” with each sex being divided into 5-year age groups, the researchers noted.

Based on these data, the investigators came to the following conclusions:

• Twenty conditions accounted for approximately 58% of personal health care spending, which totaled an estimated $1.2 trillion in 2013.

• More resources were spent on diabetes than any other condition in 2013, at an estimated $101.4 billion. Prescribed medications accounted for nearly 60% of diabetes costs.

• The second-highest amount of health care spending was for ischemic heart disease, which accounted for $88.1 billion in 2013. Most such spending occurred in inpatient settings.

• Low-back and neck pain, comprising the third-highest level of spending, cost an estimated $87.6 billion. Approximately 60% of this spending occurred in ambulatory settings.

• Among all 155 conditions, spending for diabetes and low-back and neck pain increased the most during the 18-year study period.

• Among all six types of care, spending on pharmaceuticals and emergency care increased the most during the study period.

It is important to note that for the purposes of this study, cancer was disaggregated into 29 separate conditions, and none of them placed in the top 20 for health care spending, Dr. Dieleman and his associates noted (JAMA. 2016;316[24]:2627-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16885).

When spending was categorized by patient age groups, working-age adults accounted for the greatest amount spent in 2013, estimated at $1,070.1 billion. But that was followed closely by patients aged 65 and older, who accounted for an estimated $796.5 billion, much of which was spent on care in nursing facilities. The smallest amount of health care spending was in children over age 1 and adolescents, who accounted for an estimated $233.5 billion.

Among the other study findings:

• Spending on pharmaceutical treatment of two conditions, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, increased at more than double the rate of total health care spending. It totaled an estimated $135.7 billion in 2013.

• Other top-20 conditions included falls, depression, skin disorders such as acne and eczema, sense disorders such as vision correction and hearing loss, dental care, urinary disorders, and lower respiratory tract infection.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Vitality Institute. Dr. Dieleman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Dieleman et al. have “followed” the health care money, and the trail could ultimately lead to the United States changing how it spends a staggering, almost unimaginable amount – roughly $3.2 trillion in 2015 – on health care.

At the very least, their data indicate that the United States should pay more attention to managing physical pain, controlling the costs of pharmaceuticals, and promoting lifestyle interventions that prevent or ameliorate obesity and other factors contributing to diabetes and heart disease.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, is provost of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine and in the department of health care management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported receiving speaking fees from numerous industry sources. Dr. Emanuel made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Dieleman’s report (JAMA 2016;316:2604-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16739).

Dieleman et al. have “followed” the health care money, and the trail could ultimately lead to the United States changing how it spends a staggering, almost unimaginable amount – roughly $3.2 trillion in 2015 – on health care.

At the very least, their data indicate that the United States should pay more attention to managing physical pain, controlling the costs of pharmaceuticals, and promoting lifestyle interventions that prevent or ameliorate obesity and other factors contributing to diabetes and heart disease.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, is provost of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine and in the department of health care management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported receiving speaking fees from numerous industry sources. Dr. Emanuel made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Dieleman’s report (JAMA 2016;316:2604-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16739).

Dieleman et al. have “followed” the health care money, and the trail could ultimately lead to the United States changing how it spends a staggering, almost unimaginable amount – roughly $3.2 trillion in 2015 – on health care.

At the very least, their data indicate that the United States should pay more attention to managing physical pain, controlling the costs of pharmaceuticals, and promoting lifestyle interventions that prevent or ameliorate obesity and other factors contributing to diabetes and heart disease.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, is provost of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine and in the department of health care management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported receiving speaking fees from numerous industry sources. Dr. Emanuel made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Dieleman’s report (JAMA 2016;316:2604-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16739).

Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and back and neck pain are the top three conditions accounting for the highest spending on personal health care in the United States, according to a report published online Dec. 27 in JAMA.

In addition, spending on pharmaceuticals – particularly diabetes therapies, antihypertensive drugs, and medications for hyperlipidemia – drove much of the massive increase in health care spending during the past 2 decades, said Joseph L. Dieleman, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

Recent increases in health care spending are well documented, but less is known about what is spent for individual conditions, in different health care settings, and in various patient age groups. To assess health care spending across these categories, the investigators collected and analyzed data for 1996 through 2013 from nationally representative surveys of households, nationally representative surveys of medical facilities, insurance claims, government budgets, and other official records.

They grouped the data into six type-of-care categories: inpatient care, ambulatory care, emergency department care, nursing facility care, dental care, and prescribed pharmaceuticals. “Spending on the six types of personal health care was then disaggregated across 155 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive conditions and 38 age and sex groups,” with each sex being divided into 5-year age groups, the researchers noted.

Based on these data, the investigators came to the following conclusions:

• Twenty conditions accounted for approximately 58% of personal health care spending, which totaled an estimated $1.2 trillion in 2013.

• More resources were spent on diabetes than any other condition in 2013, at an estimated $101.4 billion. Prescribed medications accounted for nearly 60% of diabetes costs.

• The second-highest amount of health care spending was for ischemic heart disease, which accounted for $88.1 billion in 2013. Most such spending occurred in inpatient settings.

• Low-back and neck pain, comprising the third-highest level of spending, cost an estimated $87.6 billion. Approximately 60% of this spending occurred in ambulatory settings.

• Among all 155 conditions, spending for diabetes and low-back and neck pain increased the most during the 18-year study period.

• Among all six types of care, spending on pharmaceuticals and emergency care increased the most during the study period.

It is important to note that for the purposes of this study, cancer was disaggregated into 29 separate conditions, and none of them placed in the top 20 for health care spending, Dr. Dieleman and his associates noted (JAMA. 2016;316[24]:2627-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16885).

When spending was categorized by patient age groups, working-age adults accounted for the greatest amount spent in 2013, estimated at $1,070.1 billion. But that was followed closely by patients aged 65 and older, who accounted for an estimated $796.5 billion, much of which was spent on care in nursing facilities. The smallest amount of health care spending was in children over age 1 and adolescents, who accounted for an estimated $233.5 billion.

Among the other study findings:

• Spending on pharmaceutical treatment of two conditions, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, increased at more than double the rate of total health care spending. It totaled an estimated $135.7 billion in 2013.

• Other top-20 conditions included falls, depression, skin disorders such as acne and eczema, sense disorders such as vision correction and hearing loss, dental care, urinary disorders, and lower respiratory tract infection.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Vitality Institute. Dr. Dieleman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and back and neck pain are the top three conditions accounting for the highest spending on personal health care in the United States, according to a report published online Dec. 27 in JAMA.

In addition, spending on pharmaceuticals – particularly diabetes therapies, antihypertensive drugs, and medications for hyperlipidemia – drove much of the massive increase in health care spending during the past 2 decades, said Joseph L. Dieleman, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

Recent increases in health care spending are well documented, but less is known about what is spent for individual conditions, in different health care settings, and in various patient age groups. To assess health care spending across these categories, the investigators collected and analyzed data for 1996 through 2013 from nationally representative surveys of households, nationally representative surveys of medical facilities, insurance claims, government budgets, and other official records.

They grouped the data into six type-of-care categories: inpatient care, ambulatory care, emergency department care, nursing facility care, dental care, and prescribed pharmaceuticals. “Spending on the six types of personal health care was then disaggregated across 155 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive conditions and 38 age and sex groups,” with each sex being divided into 5-year age groups, the researchers noted.

Based on these data, the investigators came to the following conclusions:

• Twenty conditions accounted for approximately 58% of personal health care spending, which totaled an estimated $1.2 trillion in 2013.

• More resources were spent on diabetes than any other condition in 2013, at an estimated $101.4 billion. Prescribed medications accounted for nearly 60% of diabetes costs.

• The second-highest amount of health care spending was for ischemic heart disease, which accounted for $88.1 billion in 2013. Most such spending occurred in inpatient settings.

• Low-back and neck pain, comprising the third-highest level of spending, cost an estimated $87.6 billion. Approximately 60% of this spending occurred in ambulatory settings.

• Among all 155 conditions, spending for diabetes and low-back and neck pain increased the most during the 18-year study period.

• Among all six types of care, spending on pharmaceuticals and emergency care increased the most during the study period.

It is important to note that for the purposes of this study, cancer was disaggregated into 29 separate conditions, and none of them placed in the top 20 for health care spending, Dr. Dieleman and his associates noted (JAMA. 2016;316[24]:2627-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16885).

When spending was categorized by patient age groups, working-age adults accounted for the greatest amount spent in 2013, estimated at $1,070.1 billion. But that was followed closely by patients aged 65 and older, who accounted for an estimated $796.5 billion, much of which was spent on care in nursing facilities. The smallest amount of health care spending was in children over age 1 and adolescents, who accounted for an estimated $233.5 billion.

Among the other study findings:

• Spending on pharmaceutical treatment of two conditions, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, increased at more than double the rate of total health care spending. It totaled an estimated $135.7 billion in 2013.

• Other top-20 conditions included falls, depression, skin disorders such as acne and eczema, sense disorders such as vision correction and hearing loss, dental care, urinary disorders, and lower respiratory tract infection.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Vitality Institute. Dr. Dieleman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: More resources were spent on diabetes than any other condition in 2013, at an estimated $101.4 billion.

Data source: A comprehensive estimate of U.S. spending on personal health care, based on information collected from nationally representative surveys of households and medical facilities, government budgets, insurance claims, and official records from 1996 through 2013.

Disclosures: The National Institute on Aging and the Vitality Institute supported the work. Dr. Dieleman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Confirmation CT prevents unnecessary pulmonary nodule bronchoscopy

It’s probably a good idea to do a repeat CT the morning of a scheduled bronchoscopy to make sure the pulmonary nodule is still there, according to investigators from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

From Jan. 2015 to June 2016, 116 patients there were scheduled for navigational bronchoscopy to diagnose pulmonary lesions found on screening CTs. Eight (6.9%) – four men, four women, with an average age of 50 years – had a decrease in size or resolution of their lesion on confirmatory CT, leading to cancellations of their procedure. The number needed to screen to prevent one unnecessary procedure was 15. For canceled cases, the average time from screening CT to scheduled bronchoscopy was 53 days; for patients who underwent a bronchoscopy, it was 50 days (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016 Dec;13[12]:2223-8).

It can take months to schedule a bronchoscopy after a pulmonary nodule is found on CT screening. Once in a while, the investigators and others have found, even suspicious nodules resolve on their own, and patients end up having a bronchoscopy they don’t need.

“If there is a significant delay from the initial imaging, practitioners should consider repeat studies before proceeding with the scheduled procedure ... Same-day imaging may decrease unnecessary procedural risk ... The optimal time that should be allowed to pass is difficult to ascertain,” said investigators led by Roy Semaan, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Hopkins.

The team used a newer version of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (Veran Medical Technologies, St. Louis), which requires expiratory and inspiratory CTs the morning of the procedure so software can build a virtual airway model to localize the nodule.

In addition to nodule resolution, same-day CTs might identify disease progression that alters the diagnostic plan of care.

“The most obvious risk associated with repeat CT imaging is the increased radiation exposure to the patient. Patients in our study who received inspiratory and expiratory CT scans ... had a mean exposure of 9.485 mSv, which is not “negligible, but one-time doses at this range are generally considered to be low risk for contributing to the future development of a malignancy,” the team said.

The extra cost of a same-day noncontrast chest CT – about $300, the authors said – is more than offset if it cancels “an unnecessary procedure with its associated risks,” they said.

Dr. Semaan had no disclosures. Three investigators reported grants and personal fees from Veran.

It’s probably a good idea to do a repeat CT the morning of a scheduled bronchoscopy to make sure the pulmonary nodule is still there, according to investigators from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

From Jan. 2015 to June 2016, 116 patients there were scheduled for navigational bronchoscopy to diagnose pulmonary lesions found on screening CTs. Eight (6.9%) – four men, four women, with an average age of 50 years – had a decrease in size or resolution of their lesion on confirmatory CT, leading to cancellations of their procedure. The number needed to screen to prevent one unnecessary procedure was 15. For canceled cases, the average time from screening CT to scheduled bronchoscopy was 53 days; for patients who underwent a bronchoscopy, it was 50 days (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016 Dec;13[12]:2223-8).

It can take months to schedule a bronchoscopy after a pulmonary nodule is found on CT screening. Once in a while, the investigators and others have found, even suspicious nodules resolve on their own, and patients end up having a bronchoscopy they don’t need.

“If there is a significant delay from the initial imaging, practitioners should consider repeat studies before proceeding with the scheduled procedure ... Same-day imaging may decrease unnecessary procedural risk ... The optimal time that should be allowed to pass is difficult to ascertain,” said investigators led by Roy Semaan, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Hopkins.

The team used a newer version of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (Veran Medical Technologies, St. Louis), which requires expiratory and inspiratory CTs the morning of the procedure so software can build a virtual airway model to localize the nodule.

In addition to nodule resolution, same-day CTs might identify disease progression that alters the diagnostic plan of care.

“The most obvious risk associated with repeat CT imaging is the increased radiation exposure to the patient. Patients in our study who received inspiratory and expiratory CT scans ... had a mean exposure of 9.485 mSv, which is not “negligible, but one-time doses at this range are generally considered to be low risk for contributing to the future development of a malignancy,” the team said.

The extra cost of a same-day noncontrast chest CT – about $300, the authors said – is more than offset if it cancels “an unnecessary procedure with its associated risks,” they said.

Dr. Semaan had no disclosures. Three investigators reported grants and personal fees from Veran.

It’s probably a good idea to do a repeat CT the morning of a scheduled bronchoscopy to make sure the pulmonary nodule is still there, according to investigators from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

From Jan. 2015 to June 2016, 116 patients there were scheduled for navigational bronchoscopy to diagnose pulmonary lesions found on screening CTs. Eight (6.9%) – four men, four women, with an average age of 50 years – had a decrease in size or resolution of their lesion on confirmatory CT, leading to cancellations of their procedure. The number needed to screen to prevent one unnecessary procedure was 15. For canceled cases, the average time from screening CT to scheduled bronchoscopy was 53 days; for patients who underwent a bronchoscopy, it was 50 days (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016 Dec;13[12]:2223-8).

It can take months to schedule a bronchoscopy after a pulmonary nodule is found on CT screening. Once in a while, the investigators and others have found, even suspicious nodules resolve on their own, and patients end up having a bronchoscopy they don’t need.

“If there is a significant delay from the initial imaging, practitioners should consider repeat studies before proceeding with the scheduled procedure ... Same-day imaging may decrease unnecessary procedural risk ... The optimal time that should be allowed to pass is difficult to ascertain,” said investigators led by Roy Semaan, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Hopkins.

The team used a newer version of electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (Veran Medical Technologies, St. Louis), which requires expiratory and inspiratory CTs the morning of the procedure so software can build a virtual airway model to localize the nodule.

In addition to nodule resolution, same-day CTs might identify disease progression that alters the diagnostic plan of care.

“The most obvious risk associated with repeat CT imaging is the increased radiation exposure to the patient. Patients in our study who received inspiratory and expiratory CT scans ... had a mean exposure of 9.485 mSv, which is not “negligible, but one-time doses at this range are generally considered to be low risk for contributing to the future development of a malignancy,” the team said.

The extra cost of a same-day noncontrast chest CT – about $300, the authors said – is more than offset if it cancels “an unnecessary procedure with its associated risks,” they said.

Dr. Semaan had no disclosures. Three investigators reported grants and personal fees from Veran.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of 116 patients, eight (6.9%) – four men, four women, average age 50 years – had a decrease in size or resolution of their lesion on confirmatory CT, leading to cancellation of their procedure.

Data source: Prospective series from Johns Hopkins University.

Disclosures: Three investigators reported grants and personal fees from Veran.

Options narrow for acute decompensated heart failure

Acute decompensated heart failure is a condition that clinicians want to prevent rather than treat.

The idea that patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure can have a substantial change in their prognosis from an acute intervention given in the hospital seemed to finally hit a brick wall in November at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Treatment of acute heart failure patients with the vasodilating natriuretic peptide ularitide failed to cut long-term cardiovascular mortality or improve several other acute and mid-term outcomes in the TRUE-AHF trial. In a second report, ATHENA-HF, acute treatment with high-dose spironolactone during acute heart failure hospitalizations failed to improve a marker of heart failure severity, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

What alternative interventions are left? Dr. Yancy, as well as Milton Packer, MD, the cardiologist who led TRUE-HF, had somewhat similar answers.

In his discussion of TRUE-AHF, Dr. Yancy cited two possibilities: greater use of the relatively new drug formulation sacubitril plus valsartan (Entresto), which showed strong benefit treating patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); and expanded use of pulmonary-artery pressure (PAP) monitoring using an implanted device that gives clinicians early warning when a heart failure patient’s fluid volume moves into the danger zone that precedes by days or weeks the acute decompensation that produces dyspnea and drives a patient to the hospital.

Increasing experience with PAP monitoring “continues to endorse the notion that having early warning [of fluid overload] is important,” Dr. Yancy said in an interview. “The point of acuity in acute decompensated heart failure predates hospital admission, and this monitoring system allows us to catch this before it causes an emergency department visit. The data are very persuasive.”

“PAP usually rises 2-4 weeks before a heart failure hospitalization. Perhaps we need to focus more on long-term treatment rather than treatment in the hospital.” That’s especially true for patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) because right now no treatment is clearly proven to improve HFpEF outcomes (although several experts make a persuasive case for spironolactone).

“Tight regulation of volume status is our best chance to improve outcomes in HFpEF,” said Dr. Stevenson, who helped pioneer the idea of PAP monitoring for heart failure patients. “Maintaining good volume is very important for HFpEF patients.”

But success with PAP monitoring requires more than gathering the pressure data. Producing benefit for patients “is predicated on having an infrastructure to accommodate the influx of PAP data, being nimble enough to respond to the data and being very precise about which patients you use this in,” cautioned Dr. Yancy. “The tool is not beneficial if the infrastructure is not there,”

The idea is still so new (the first implanted PAP monitor received U.S. approval in 2014) that at his institution, Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, about a dozen patients now have a monitor, he said.

“We’re looking to use it in patients with HFpEF, whom we can’t offer anything else. I’m intrigued by what I see,” in this first wave of Northwestern patients. Dr. Yancy’s anecdotal experience with PAP monitoring so far “helps endorse what the trial results suggested” about providing incremental benefit to heart failure patients.

“The solution is to prevent hospitalization in the first place with the medications we already have, but they’re not used. The medications we already have are enough, but they need to be used,” Dr. Packer told me in an interview during the meeting. He speculated that perhaps 10%-15% of HFrEF patients currently receive the full guideline-directed regimen of heart failure drugs. “That’s unbelievable,” he exclaimed. If clinicians diligently treated advanced HFrEF patients with these four agents, “you’d see a 60%, 70% drop in hospitalizations,” he suggested.

Dr. Packer put some of the blame for underuse of guideline-directed medications on the low financial incentive physicians have to vigorously apply this strategy.

He backed PAP monitoring as a good additional step for selected patients with unstable heart failure. “But as a general approach to managing patients with class III HFrEF, first put them on optimal medical therapy; then we can talk about an invasive procedure to place a PAP monitoring device.”

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Acute decompensated heart failure is a condition that clinicians want to prevent rather than treat.

The idea that patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure can have a substantial change in their prognosis from an acute intervention given in the hospital seemed to finally hit a brick wall in November at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Treatment of acute heart failure patients with the vasodilating natriuretic peptide ularitide failed to cut long-term cardiovascular mortality or improve several other acute and mid-term outcomes in the TRUE-AHF trial. In a second report, ATHENA-HF, acute treatment with high-dose spironolactone during acute heart failure hospitalizations failed to improve a marker of heart failure severity, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

What alternative interventions are left? Dr. Yancy, as well as Milton Packer, MD, the cardiologist who led TRUE-HF, had somewhat similar answers.

In his discussion of TRUE-AHF, Dr. Yancy cited two possibilities: greater use of the relatively new drug formulation sacubitril plus valsartan (Entresto), which showed strong benefit treating patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); and expanded use of pulmonary-artery pressure (PAP) monitoring using an implanted device that gives clinicians early warning when a heart failure patient’s fluid volume moves into the danger zone that precedes by days or weeks the acute decompensation that produces dyspnea and drives a patient to the hospital.

Increasing experience with PAP monitoring “continues to endorse the notion that having early warning [of fluid overload] is important,” Dr. Yancy said in an interview. “The point of acuity in acute decompensated heart failure predates hospital admission, and this monitoring system allows us to catch this before it causes an emergency department visit. The data are very persuasive.”

“PAP usually rises 2-4 weeks before a heart failure hospitalization. Perhaps we need to focus more on long-term treatment rather than treatment in the hospital.” That’s especially true for patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) because right now no treatment is clearly proven to improve HFpEF outcomes (although several experts make a persuasive case for spironolactone).

“Tight regulation of volume status is our best chance to improve outcomes in HFpEF,” said Dr. Stevenson, who helped pioneer the idea of PAP monitoring for heart failure patients. “Maintaining good volume is very important for HFpEF patients.”

But success with PAP monitoring requires more than gathering the pressure data. Producing benefit for patients “is predicated on having an infrastructure to accommodate the influx of PAP data, being nimble enough to respond to the data and being very precise about which patients you use this in,” cautioned Dr. Yancy. “The tool is not beneficial if the infrastructure is not there,”

The idea is still so new (the first implanted PAP monitor received U.S. approval in 2014) that at his institution, Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, about a dozen patients now have a monitor, he said.

“We’re looking to use it in patients with HFpEF, whom we can’t offer anything else. I’m intrigued by what I see,” in this first wave of Northwestern patients. Dr. Yancy’s anecdotal experience with PAP monitoring so far “helps endorse what the trial results suggested” about providing incremental benefit to heart failure patients.

“The solution is to prevent hospitalization in the first place with the medications we already have, but they’re not used. The medications we already have are enough, but they need to be used,” Dr. Packer told me in an interview during the meeting. He speculated that perhaps 10%-15% of HFrEF patients currently receive the full guideline-directed regimen of heart failure drugs. “That’s unbelievable,” he exclaimed. If clinicians diligently treated advanced HFrEF patients with these four agents, “you’d see a 60%, 70% drop in hospitalizations,” he suggested.

Dr. Packer put some of the blame for underuse of guideline-directed medications on the low financial incentive physicians have to vigorously apply this strategy.

He backed PAP monitoring as a good additional step for selected patients with unstable heart failure. “But as a general approach to managing patients with class III HFrEF, first put them on optimal medical therapy; then we can talk about an invasive procedure to place a PAP monitoring device.”

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Acute decompensated heart failure is a condition that clinicians want to prevent rather than treat.

The idea that patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure can have a substantial change in their prognosis from an acute intervention given in the hospital seemed to finally hit a brick wall in November at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Treatment of acute heart failure patients with the vasodilating natriuretic peptide ularitide failed to cut long-term cardiovascular mortality or improve several other acute and mid-term outcomes in the TRUE-AHF trial. In a second report, ATHENA-HF, acute treatment with high-dose spironolactone during acute heart failure hospitalizations failed to improve a marker of heart failure severity, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

What alternative interventions are left? Dr. Yancy, as well as Milton Packer, MD, the cardiologist who led TRUE-HF, had somewhat similar answers.

In his discussion of TRUE-AHF, Dr. Yancy cited two possibilities: greater use of the relatively new drug formulation sacubitril plus valsartan (Entresto), which showed strong benefit treating patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF); and expanded use of pulmonary-artery pressure (PAP) monitoring using an implanted device that gives clinicians early warning when a heart failure patient’s fluid volume moves into the danger zone that precedes by days or weeks the acute decompensation that produces dyspnea and drives a patient to the hospital.

Increasing experience with PAP monitoring “continues to endorse the notion that having early warning [of fluid overload] is important,” Dr. Yancy said in an interview. “The point of acuity in acute decompensated heart failure predates hospital admission, and this monitoring system allows us to catch this before it causes an emergency department visit. The data are very persuasive.”

“PAP usually rises 2-4 weeks before a heart failure hospitalization. Perhaps we need to focus more on long-term treatment rather than treatment in the hospital.” That’s especially true for patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) because right now no treatment is clearly proven to improve HFpEF outcomes (although several experts make a persuasive case for spironolactone).

“Tight regulation of volume status is our best chance to improve outcomes in HFpEF,” said Dr. Stevenson, who helped pioneer the idea of PAP monitoring for heart failure patients. “Maintaining good volume is very important for HFpEF patients.”

But success with PAP monitoring requires more than gathering the pressure data. Producing benefit for patients “is predicated on having an infrastructure to accommodate the influx of PAP data, being nimble enough to respond to the data and being very precise about which patients you use this in,” cautioned Dr. Yancy. “The tool is not beneficial if the infrastructure is not there,”

The idea is still so new (the first implanted PAP monitor received U.S. approval in 2014) that at his institution, Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, about a dozen patients now have a monitor, he said.

“We’re looking to use it in patients with HFpEF, whom we can’t offer anything else. I’m intrigued by what I see,” in this first wave of Northwestern patients. Dr. Yancy’s anecdotal experience with PAP monitoring so far “helps endorse what the trial results suggested” about providing incremental benefit to heart failure patients.

“The solution is to prevent hospitalization in the first place with the medications we already have, but they’re not used. The medications we already have are enough, but they need to be used,” Dr. Packer told me in an interview during the meeting. He speculated that perhaps 10%-15% of HFrEF patients currently receive the full guideline-directed regimen of heart failure drugs. “That’s unbelievable,” he exclaimed. If clinicians diligently treated advanced HFrEF patients with these four agents, “you’d see a 60%, 70% drop in hospitalizations,” he suggested.

Dr. Packer put some of the blame for underuse of guideline-directed medications on the low financial incentive physicians have to vigorously apply this strategy.

He backed PAP monitoring as a good additional step for selected patients with unstable heart failure. “But as a general approach to managing patients with class III HFrEF, first put them on optimal medical therapy; then we can talk about an invasive procedure to place a PAP monitoring device.”

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

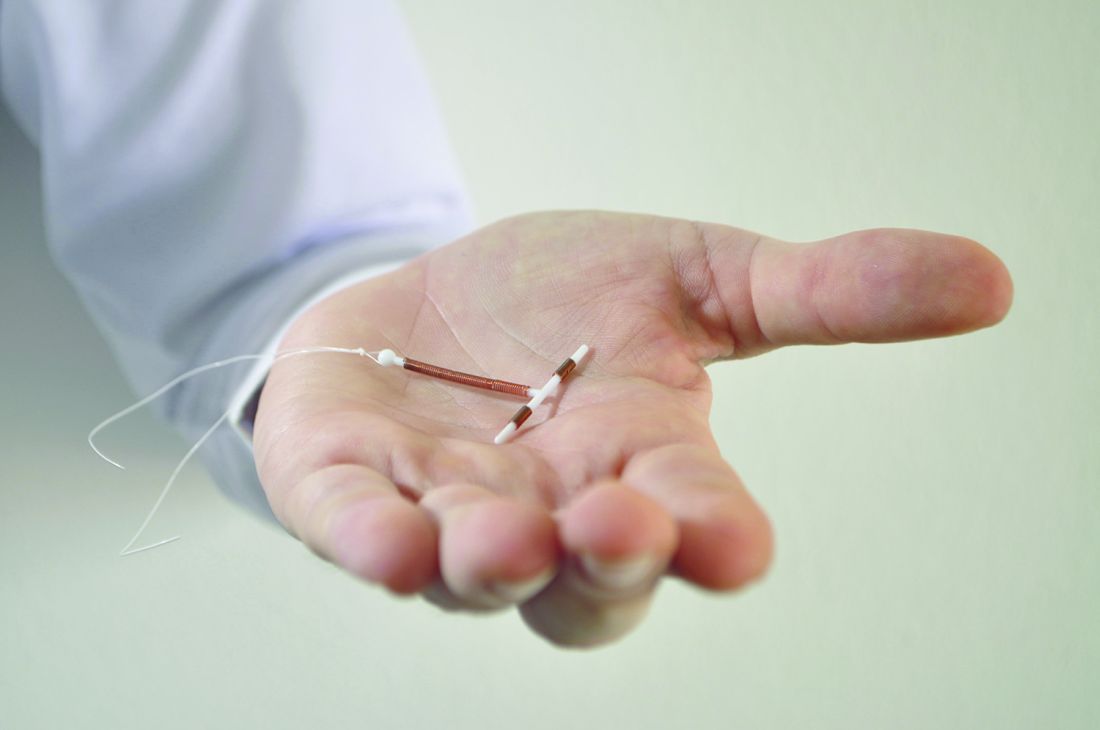

Immediate postpartum LARC requires cross-disciplinary cooperation in the hospital

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Success in establishing an immediate postpartum LARC program involves team-building across hospital disciplines.

Major finding: Factors associated with success included early coordination among financial, administrative, pharmacy, and clinical personnel.

Data source: A qualitative analysis of interviews with 32 employees (clinical and nonclinical) from 10 hospitals in Georgia.

Disclosures: Two authors disclosed relationships with LARC manufacturers.

First visit for tuberous sclerosis complex comes months before diagnosis

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients were seen an average of 6.9 months before they received their TSC diagnosis.

Data source: Retrospective review of claims and enrollment data from 2,163 patients with tuberous sclerosis.

Disclosures: Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum; one is employed by Novartis.

PCI or CABG in the high-risk patient

The recent report from the SYNTAX trials should give pause to our interventionalist colleagues embarking on multiple angioplasty and stenting procedures in patients with complex coronary anatomy.

SYNTAX randomized 1,800 patients with left main or triple-vessel coronary artery disease to either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with the TAXUS drug-eluting stent or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) after being judged by a heart team as being in equipoise in regard to the appropriateness of either procedure (Eur Heart J. 2011;32;2125-34). The findings of several previous analyses have trended toward benefit for CABG, but none as clearly as SYNTAX. The original study was reported 6 years ago (Lancet 2013 Feb;381:629-38) and indicated that CABG was superior to PCI in patients with complex lesions. The most recent 5-year data of that study (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Jan:67;42-55) indicates that cardiac mortality in the CABG patients is superior to that in the PCI group (5.3% vs. 9.6%, respectively), and the follow-up data provide more in-depth analysis in addition to the mechanism of death. Most importantly, the recent 5-year data clarify the reasons PCI fails to measure up to the results of CABG in patients with complex coronary artery disease.

One of the overriding predictors of increased mortality with PCI is the increased complexity of anatomy. The higher SYNTAX score was related to incomplete revascularization using PCI, compared with CABG. The presence of concomitant peripheral and carotid vascular disease, in addition to a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30%, favored the CABG group. Multiple stents and stent thrombosis were also issues leading to the increased mortality in the PCI group. The main cause of death was recurrent myocardial infarction, which occurred more frequently in the PCI patients and was associated with incomplete revascularization.

The data in the SYNTAX follow-up is not new, but do reinforce what has been reported in previous meta-analyses. This study does, however, emphasize the importance of recurrent infarction as a cause of death in these patients with complex anatomy. It is possible that new stent technology and coronary flow assessment at the time of intervention could have improved the outcome of this comparison and improved the long-term patency of the stented vessels. PCI is an evolving technology heavily affected by the experience of the operator. CABG surgery has also changed, and its associated mortality and morbidity have also changed and improved. It is clear that this population raises important questions in which the operators need to individualize their decision based on trials like SYNTAX.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

The recent report from the SYNTAX trials should give pause to our interventionalist colleagues embarking on multiple angioplasty and stenting procedures in patients with complex coronary anatomy.

SYNTAX randomized 1,800 patients with left main or triple-vessel coronary artery disease to either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with the TAXUS drug-eluting stent or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) after being judged by a heart team as being in equipoise in regard to the appropriateness of either procedure (Eur Heart J. 2011;32;2125-34). The findings of several previous analyses have trended toward benefit for CABG, but none as clearly as SYNTAX. The original study was reported 6 years ago (Lancet 2013 Feb;381:629-38) and indicated that CABG was superior to PCI in patients with complex lesions. The most recent 5-year data of that study (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Jan:67;42-55) indicates that cardiac mortality in the CABG patients is superior to that in the PCI group (5.3% vs. 9.6%, respectively), and the follow-up data provide more in-depth analysis in addition to the mechanism of death. Most importantly, the recent 5-year data clarify the reasons PCI fails to measure up to the results of CABG in patients with complex coronary artery disease.

One of the overriding predictors of increased mortality with PCI is the increased complexity of anatomy. The higher SYNTAX score was related to incomplete revascularization using PCI, compared with CABG. The presence of concomitant peripheral and carotid vascular disease, in addition to a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30%, favored the CABG group. Multiple stents and stent thrombosis were also issues leading to the increased mortality in the PCI group. The main cause of death was recurrent myocardial infarction, which occurred more frequently in the PCI patients and was associated with incomplete revascularization.

The data in the SYNTAX follow-up is not new, but do reinforce what has been reported in previous meta-analyses. This study does, however, emphasize the importance of recurrent infarction as a cause of death in these patients with complex anatomy. It is possible that new stent technology and coronary flow assessment at the time of intervention could have improved the outcome of this comparison and improved the long-term patency of the stented vessels. PCI is an evolving technology heavily affected by the experience of the operator. CABG surgery has also changed, and its associated mortality and morbidity have also changed and improved. It is clear that this population raises important questions in which the operators need to individualize their decision based on trials like SYNTAX.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

The recent report from the SYNTAX trials should give pause to our interventionalist colleagues embarking on multiple angioplasty and stenting procedures in patients with complex coronary anatomy.

SYNTAX randomized 1,800 patients with left main or triple-vessel coronary artery disease to either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with the TAXUS drug-eluting stent or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) after being judged by a heart team as being in equipoise in regard to the appropriateness of either procedure (Eur Heart J. 2011;32;2125-34). The findings of several previous analyses have trended toward benefit for CABG, but none as clearly as SYNTAX. The original study was reported 6 years ago (Lancet 2013 Feb;381:629-38) and indicated that CABG was superior to PCI in patients with complex lesions. The most recent 5-year data of that study (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Jan:67;42-55) indicates that cardiac mortality in the CABG patients is superior to that in the PCI group (5.3% vs. 9.6%, respectively), and the follow-up data provide more in-depth analysis in addition to the mechanism of death. Most importantly, the recent 5-year data clarify the reasons PCI fails to measure up to the results of CABG in patients with complex coronary artery disease.

One of the overriding predictors of increased mortality with PCI is the increased complexity of anatomy. The higher SYNTAX score was related to incomplete revascularization using PCI, compared with CABG. The presence of concomitant peripheral and carotid vascular disease, in addition to a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30%, favored the CABG group. Multiple stents and stent thrombosis were also issues leading to the increased mortality in the PCI group. The main cause of death was recurrent myocardial infarction, which occurred more frequently in the PCI patients and was associated with incomplete revascularization.

The data in the SYNTAX follow-up is not new, but do reinforce what has been reported in previous meta-analyses. This study does, however, emphasize the importance of recurrent infarction as a cause of death in these patients with complex anatomy. It is possible that new stent technology and coronary flow assessment at the time of intervention could have improved the outcome of this comparison and improved the long-term patency of the stented vessels. PCI is an evolving technology heavily affected by the experience of the operator. CABG surgery has also changed, and its associated mortality and morbidity have also changed and improved. It is clear that this population raises important questions in which the operators need to individualize their decision based on trials like SYNTAX.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

FDA bans powdered gloves

The Food and Drug Administration has banned powdered gloves for use in health care settings, citing “numerous risks to patients and health care workers.” The ban extends to gloves currently in commercial distribution and in the hands of the ultimate user, meaning powdered gloves will have to be pulled from examination rooms and operating theaters.

“A thorough review of all currently available information supports FDA’s conclusion that powdered surgeon’s gloves, powdered patient examination gloves, and absorbable powder for lubricating a surgeon’s glove should be banned,” according to a FDA final rule available now online and scheduled for publication in the Federal Register on Dec. 19, 2016. The ban will become effective 30 days after the document’s publication in the Federal Register.