User login

OSA raises risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke

compared with controls, based on data from 303 individuals.

OSA has become a common chronic disease, and cardiovascular diseases including AFib also are known independent risk factors associated with OSA, Anna Hojager, MD, of Zealand University Hospital, Roskilde, Denmark, and colleagues wrote. Previous studies have shown a significant increase in AFib risk in OSA patients with severe disease, but the prevalence of undiagnosed AFib in OSA patients has not been explored.

In a study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers enrolled 238 adults with severe OSA (based on apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or higher) and 65 with mild or no OSA (based on an AHI of less than 15). The mean AHI across all participants was 34.2, and ranged from 0.2 to 115.8.

Participants underwent heart rhythm monitoring using a home system or standard ECG for 7 days; they were instructed to carry the device at all times except when showering or sweating heavily. The primary outcome was the detection of AFib, defined as at least one period of 30 seconds or longer with an irregular heart rhythm but without detectable evidence of another diagnosis. Sleep was assessed for one night using a portable sleep monitoring device. All participants were examined at baseline and measured for blood pressure, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, and ECG.

Overall, AFib occurred in 21 patients with moderate to severe OSA and 1 patient with mild/no OSA (8.8% vs. 1.5%, P = .045). The majority of patients across both groups had hypertension (66%) and dyslipidemia (77.6%), but the severe OSA group was more likely to be dysregulated and to have unknown prediabetes. Participants who were deemed candidates for anticoagulation therapy were referred for additional treatment. None of the 22 total patients with AFib had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and 68.2% had normal ejection fraction and ventricle function.

The researchers noted that no guidelines currently exist for systematic opportunistic screening for comorbidities in OSA patients, although the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends patient education as part of a multidisciplinary chronic disease management strategy. The high prevalence of AFib in OSA patients, as seen in the current study, “might warrant a recommendation of screening for paroxysmal [AFib] and could be valuable in the management of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with OSA,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the observational design and absence of polysomnography to assess OSA, the researchers noted. However, the study has the highest known prevalence of silent AFib in patients with moderate to severe OSA, and supports the value of screening and management for known comorbidities of OSA.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

compared with controls, based on data from 303 individuals.

OSA has become a common chronic disease, and cardiovascular diseases including AFib also are known independent risk factors associated with OSA, Anna Hojager, MD, of Zealand University Hospital, Roskilde, Denmark, and colleagues wrote. Previous studies have shown a significant increase in AFib risk in OSA patients with severe disease, but the prevalence of undiagnosed AFib in OSA patients has not been explored.

In a study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers enrolled 238 adults with severe OSA (based on apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or higher) and 65 with mild or no OSA (based on an AHI of less than 15). The mean AHI across all participants was 34.2, and ranged from 0.2 to 115.8.

Participants underwent heart rhythm monitoring using a home system or standard ECG for 7 days; they were instructed to carry the device at all times except when showering or sweating heavily. The primary outcome was the detection of AFib, defined as at least one period of 30 seconds or longer with an irregular heart rhythm but without detectable evidence of another diagnosis. Sleep was assessed for one night using a portable sleep monitoring device. All participants were examined at baseline and measured for blood pressure, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, and ECG.

Overall, AFib occurred in 21 patients with moderate to severe OSA and 1 patient with mild/no OSA (8.8% vs. 1.5%, P = .045). The majority of patients across both groups had hypertension (66%) and dyslipidemia (77.6%), but the severe OSA group was more likely to be dysregulated and to have unknown prediabetes. Participants who were deemed candidates for anticoagulation therapy were referred for additional treatment. None of the 22 total patients with AFib had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and 68.2% had normal ejection fraction and ventricle function.

The researchers noted that no guidelines currently exist for systematic opportunistic screening for comorbidities in OSA patients, although the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends patient education as part of a multidisciplinary chronic disease management strategy. The high prevalence of AFib in OSA patients, as seen in the current study, “might warrant a recommendation of screening for paroxysmal [AFib] and could be valuable in the management of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with OSA,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the observational design and absence of polysomnography to assess OSA, the researchers noted. However, the study has the highest known prevalence of silent AFib in patients with moderate to severe OSA, and supports the value of screening and management for known comorbidities of OSA.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

compared with controls, based on data from 303 individuals.

OSA has become a common chronic disease, and cardiovascular diseases including AFib also are known independent risk factors associated with OSA, Anna Hojager, MD, of Zealand University Hospital, Roskilde, Denmark, and colleagues wrote. Previous studies have shown a significant increase in AFib risk in OSA patients with severe disease, but the prevalence of undiagnosed AFib in OSA patients has not been explored.

In a study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers enrolled 238 adults with severe OSA (based on apnea-hypopnea index of 15 or higher) and 65 with mild or no OSA (based on an AHI of less than 15). The mean AHI across all participants was 34.2, and ranged from 0.2 to 115.8.

Participants underwent heart rhythm monitoring using a home system or standard ECG for 7 days; they were instructed to carry the device at all times except when showering or sweating heavily. The primary outcome was the detection of AFib, defined as at least one period of 30 seconds or longer with an irregular heart rhythm but without detectable evidence of another diagnosis. Sleep was assessed for one night using a portable sleep monitoring device. All participants were examined at baseline and measured for blood pressure, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, and ECG.

Overall, AFib occurred in 21 patients with moderate to severe OSA and 1 patient with mild/no OSA (8.8% vs. 1.5%, P = .045). The majority of patients across both groups had hypertension (66%) and dyslipidemia (77.6%), but the severe OSA group was more likely to be dysregulated and to have unknown prediabetes. Participants who were deemed candidates for anticoagulation therapy were referred for additional treatment. None of the 22 total patients with AFib had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and 68.2% had normal ejection fraction and ventricle function.

The researchers noted that no guidelines currently exist for systematic opportunistic screening for comorbidities in OSA patients, although the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends patient education as part of a multidisciplinary chronic disease management strategy. The high prevalence of AFib in OSA patients, as seen in the current study, “might warrant a recommendation of screening for paroxysmal [AFib] and could be valuable in the management of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with OSA,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the observational design and absence of polysomnography to assess OSA, the researchers noted. However, the study has the highest known prevalence of silent AFib in patients with moderate to severe OSA, and supports the value of screening and management for known comorbidities of OSA.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

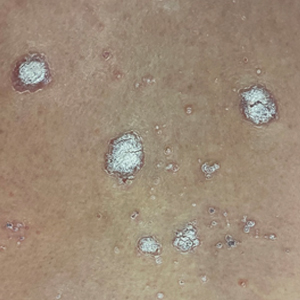

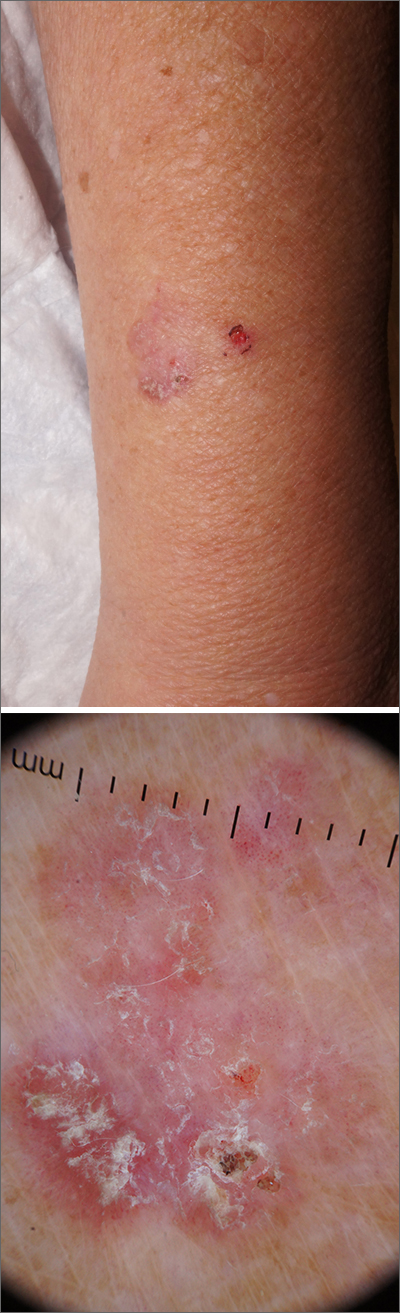

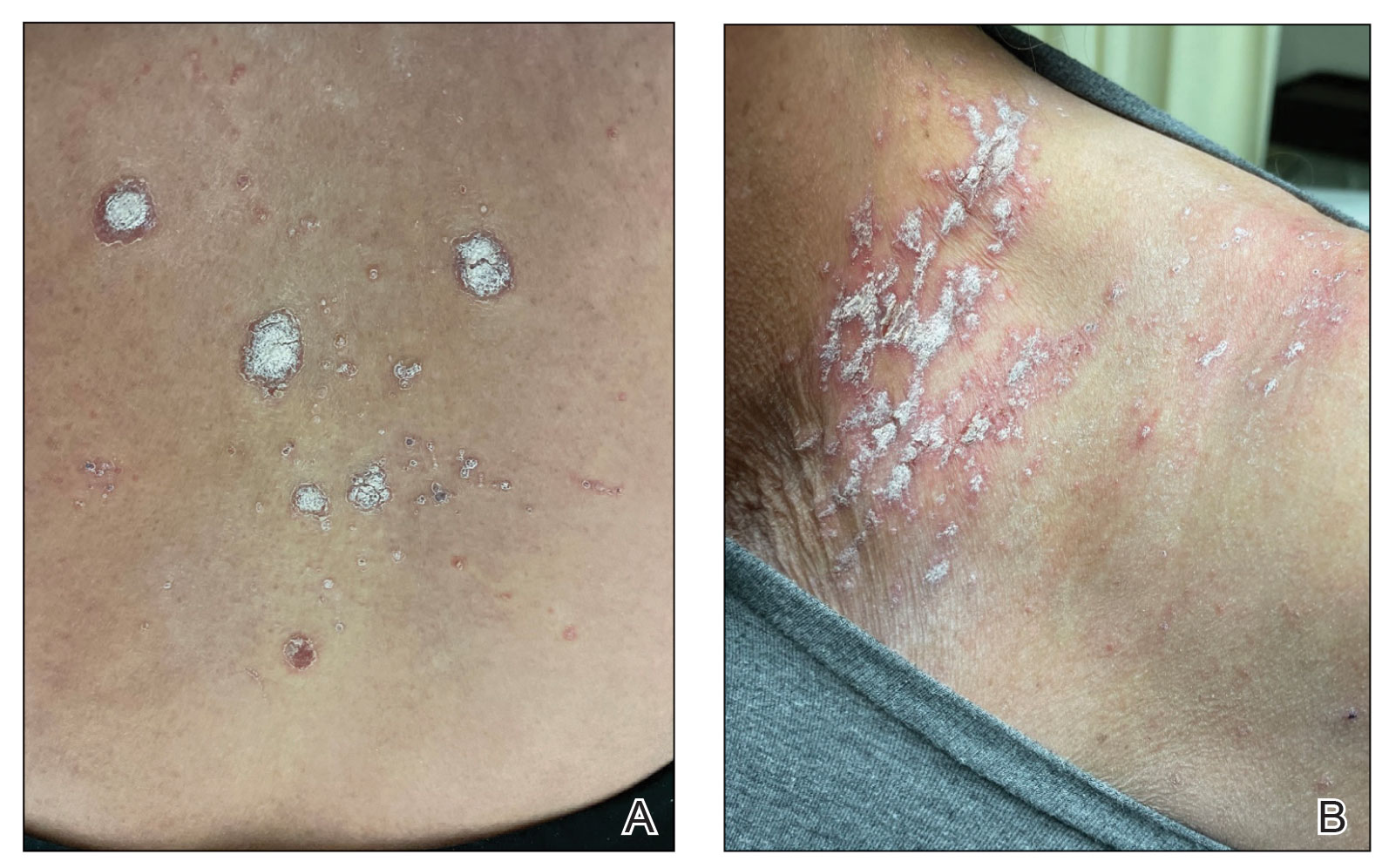

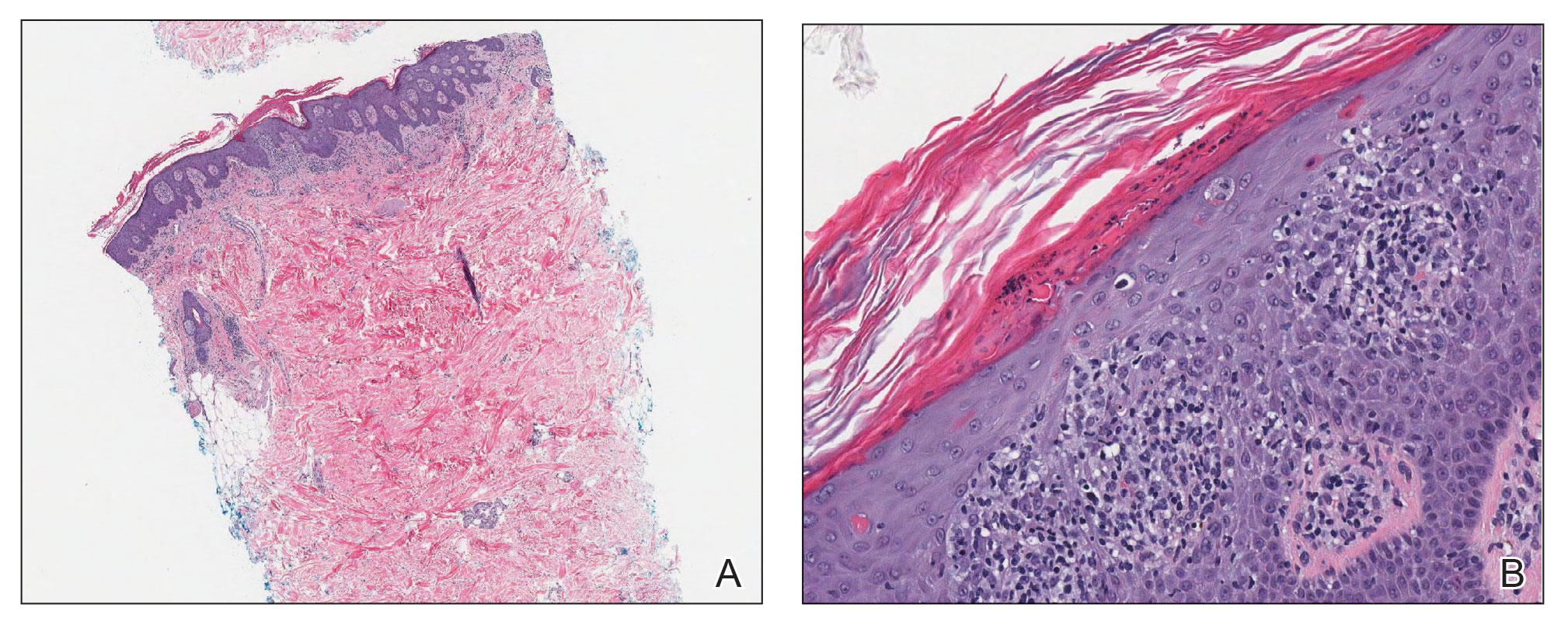

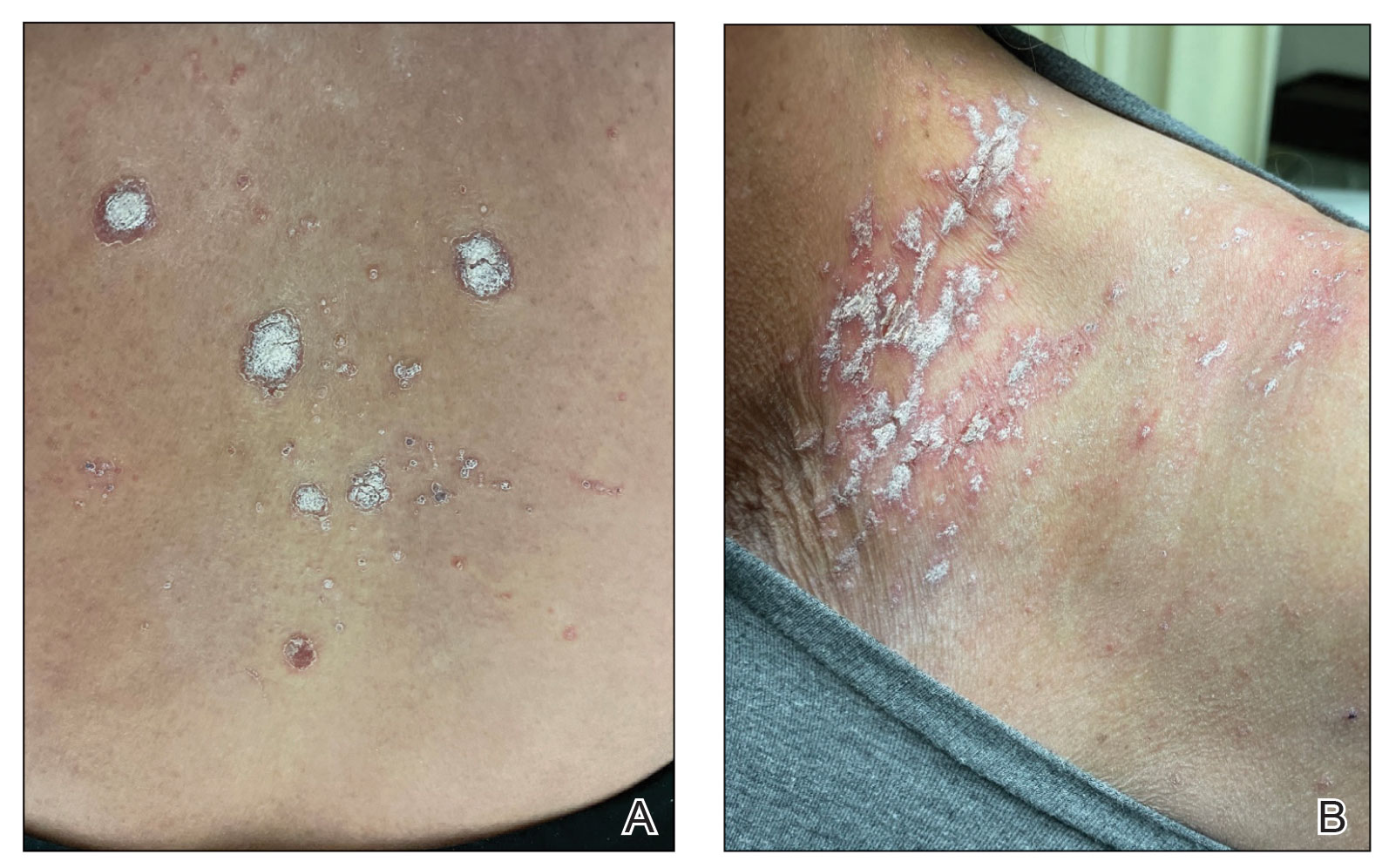

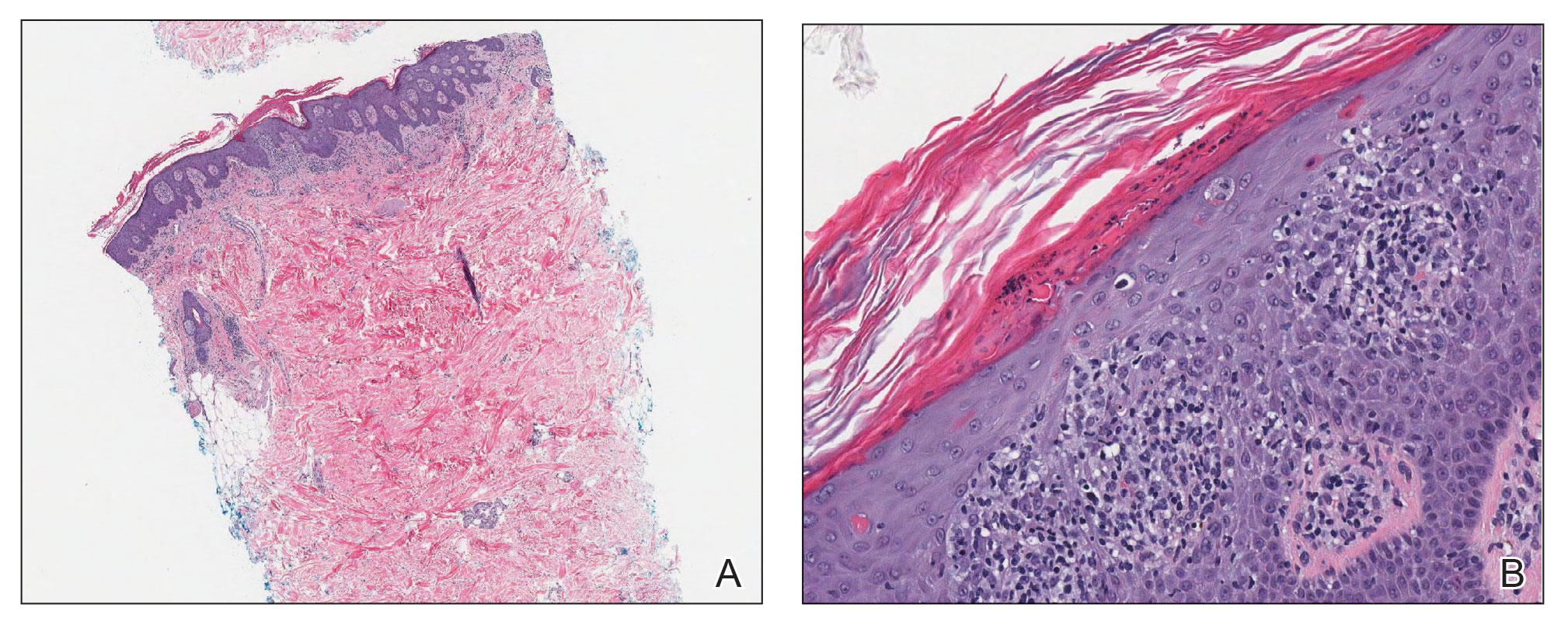

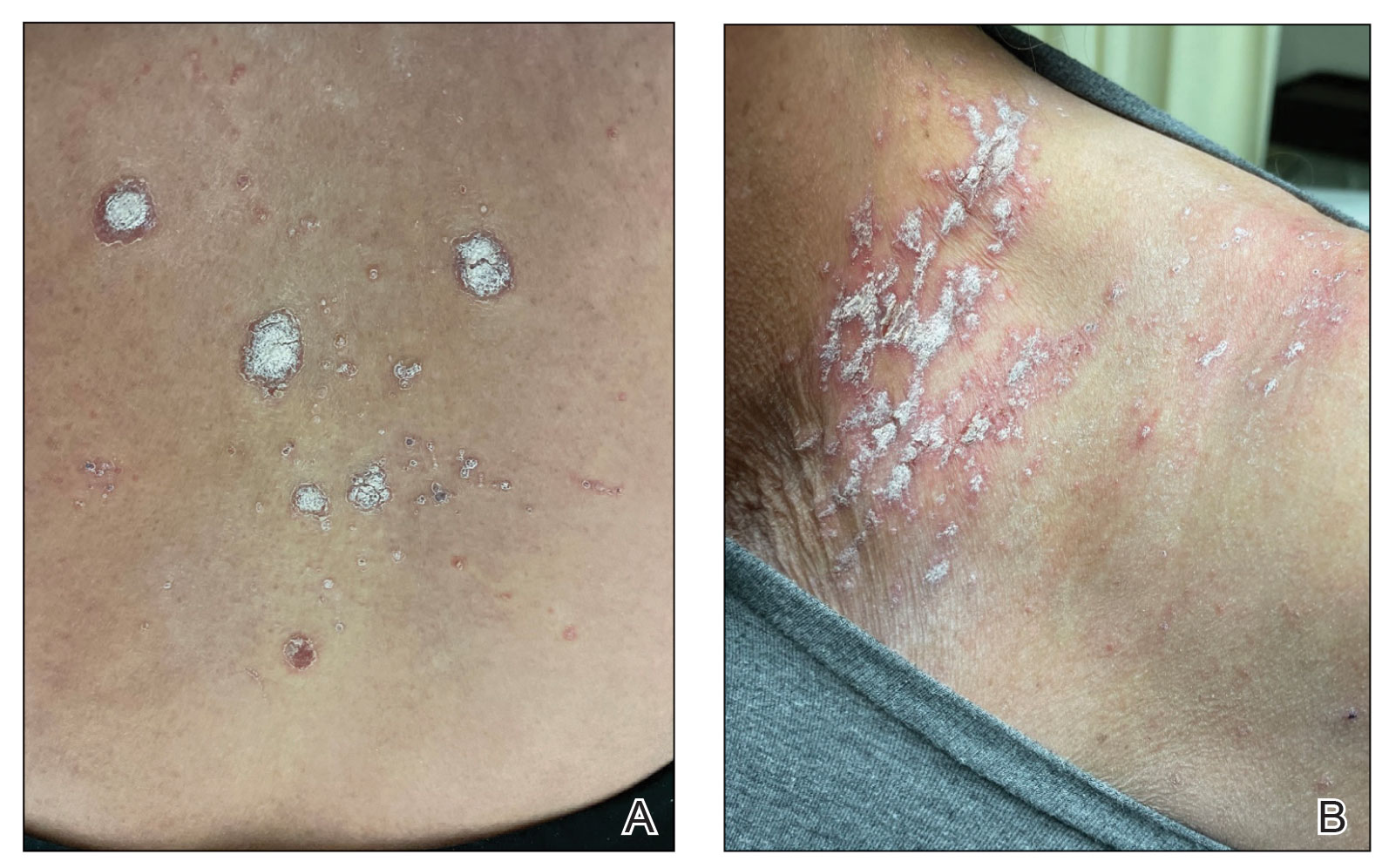

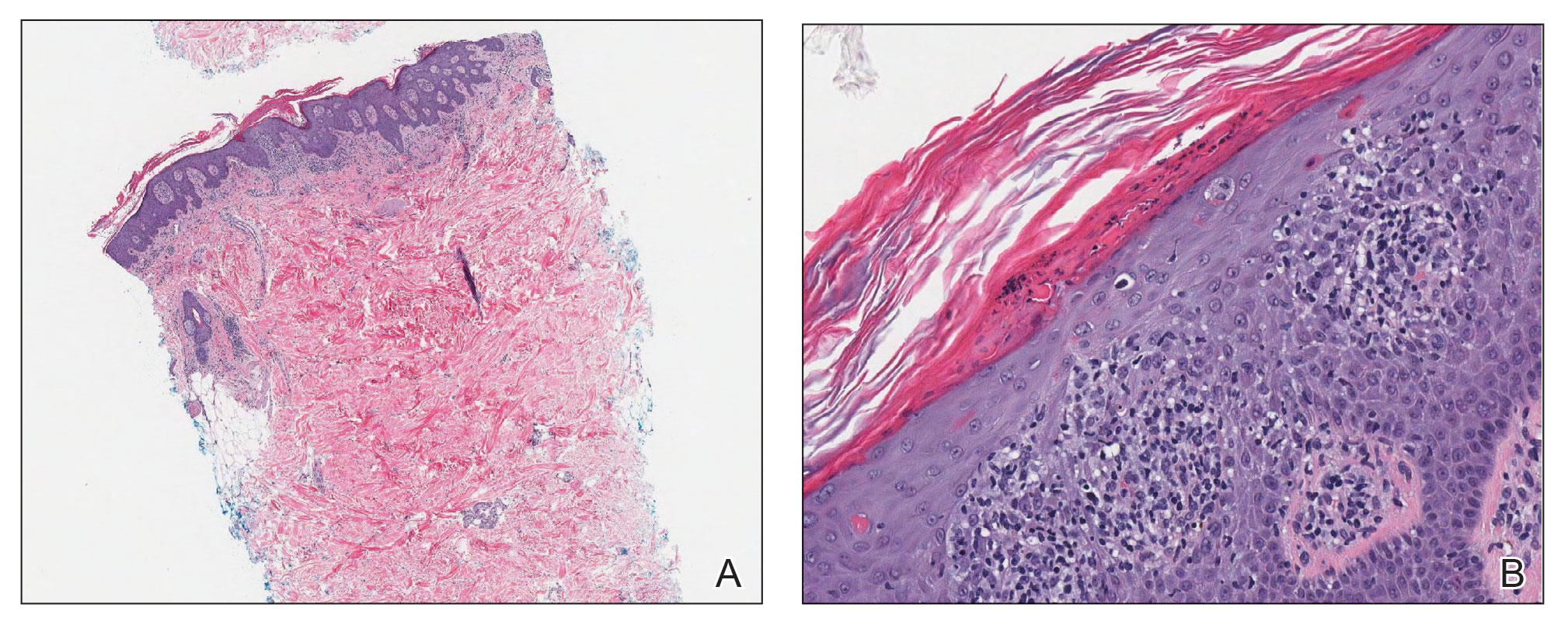

Scaly forearm plaque

Dermoscopy revealed a keratotic, 2.5-cm scaly plaque with linearly arranged dotted vessels, ulceration, and shiny white lines. A shave biopsy was consistent with a squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC in situ)—a pre-invasive keratinocyte carcinoma.

SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, is a very common skin cancer that can be easily treated. Lesions may manifest anywhere on the skin but are most often found on sun-damaged areas. Actinic keratoses are a pre-malignant precursor of SCC in situ; both are characterized by a sandpapery rough surface on a pink or brown background. Histologically, SCC in situ has atypia of keratinocytes over the full thickness of the epidermis, while actinic keratoses have limited atypia of the upper epidermis only. With this in mind, suspect SCC in situ (over actinic keratosis) when a lesion is thicker than 1 mm, larger in diameter than 5 mm, or painful.1

Treatment options include surgical and nonsurgical modalities. Excision and electrodessication and curettage (EDC) are both effective surgical procedures, with cure rates greater than 90%.2 Nonsurgical options include cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy. Treatment with 5FU or imiquimod involves the application of cream to the lesion for 4 to 6 weeks. Marked inflammation during treatment is to be expected.

In the case described here, the patient underwent EDC in the office and was counseled to continue with complete skin exams twice a year for the next 2 years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Mills KC, Kwatra SG, Feneran AN, et al. Itch and pain in nonmelanoma skin cancer: pain as an important feature of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1422-1423. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3104

2. Reschly MJ, Shenefelt PD. Controversies in skin surgery: electrodessication and curettage versus excision for low-risk, small, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:773-776.

Dermoscopy revealed a keratotic, 2.5-cm scaly plaque with linearly arranged dotted vessels, ulceration, and shiny white lines. A shave biopsy was consistent with a squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC in situ)—a pre-invasive keratinocyte carcinoma.

SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, is a very common skin cancer that can be easily treated. Lesions may manifest anywhere on the skin but are most often found on sun-damaged areas. Actinic keratoses are a pre-malignant precursor of SCC in situ; both are characterized by a sandpapery rough surface on a pink or brown background. Histologically, SCC in situ has atypia of keratinocytes over the full thickness of the epidermis, while actinic keratoses have limited atypia of the upper epidermis only. With this in mind, suspect SCC in situ (over actinic keratosis) when a lesion is thicker than 1 mm, larger in diameter than 5 mm, or painful.1

Treatment options include surgical and nonsurgical modalities. Excision and electrodessication and curettage (EDC) are both effective surgical procedures, with cure rates greater than 90%.2 Nonsurgical options include cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy. Treatment with 5FU or imiquimod involves the application of cream to the lesion for 4 to 6 weeks. Marked inflammation during treatment is to be expected.

In the case described here, the patient underwent EDC in the office and was counseled to continue with complete skin exams twice a year for the next 2 years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Dermoscopy revealed a keratotic, 2.5-cm scaly plaque with linearly arranged dotted vessels, ulceration, and shiny white lines. A shave biopsy was consistent with a squamous cell carcinoma in situ (SCC in situ)—a pre-invasive keratinocyte carcinoma.

SCC in situ, also known as Bowen’s disease, is a very common skin cancer that can be easily treated. Lesions may manifest anywhere on the skin but are most often found on sun-damaged areas. Actinic keratoses are a pre-malignant precursor of SCC in situ; both are characterized by a sandpapery rough surface on a pink or brown background. Histologically, SCC in situ has atypia of keratinocytes over the full thickness of the epidermis, while actinic keratoses have limited atypia of the upper epidermis only. With this in mind, suspect SCC in situ (over actinic keratosis) when a lesion is thicker than 1 mm, larger in diameter than 5 mm, or painful.1

Treatment options include surgical and nonsurgical modalities. Excision and electrodessication and curettage (EDC) are both effective surgical procedures, with cure rates greater than 90%.2 Nonsurgical options include cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy. Treatment with 5FU or imiquimod involves the application of cream to the lesion for 4 to 6 weeks. Marked inflammation during treatment is to be expected.

In the case described here, the patient underwent EDC in the office and was counseled to continue with complete skin exams twice a year for the next 2 years.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Mills KC, Kwatra SG, Feneran AN, et al. Itch and pain in nonmelanoma skin cancer: pain as an important feature of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1422-1423. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3104

2. Reschly MJ, Shenefelt PD. Controversies in skin surgery: electrodessication and curettage versus excision for low-risk, small, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:773-776.

1. Mills KC, Kwatra SG, Feneran AN, et al. Itch and pain in nonmelanoma skin cancer: pain as an important feature of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1422-1423. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3104

2. Reschly MJ, Shenefelt PD. Controversies in skin surgery: electrodessication and curettage versus excision for low-risk, small, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:773-776.

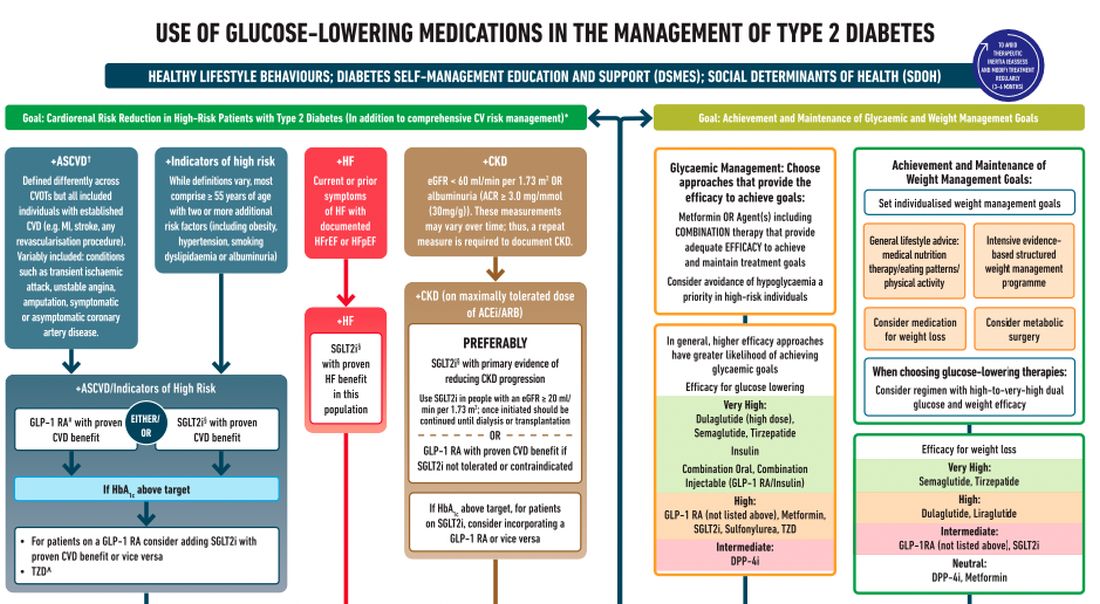

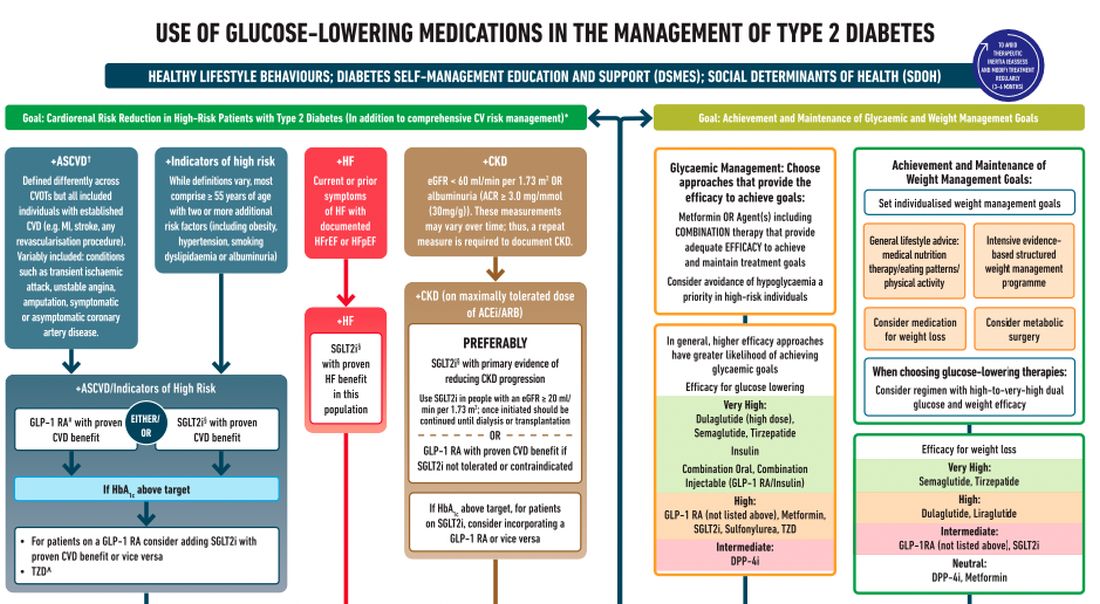

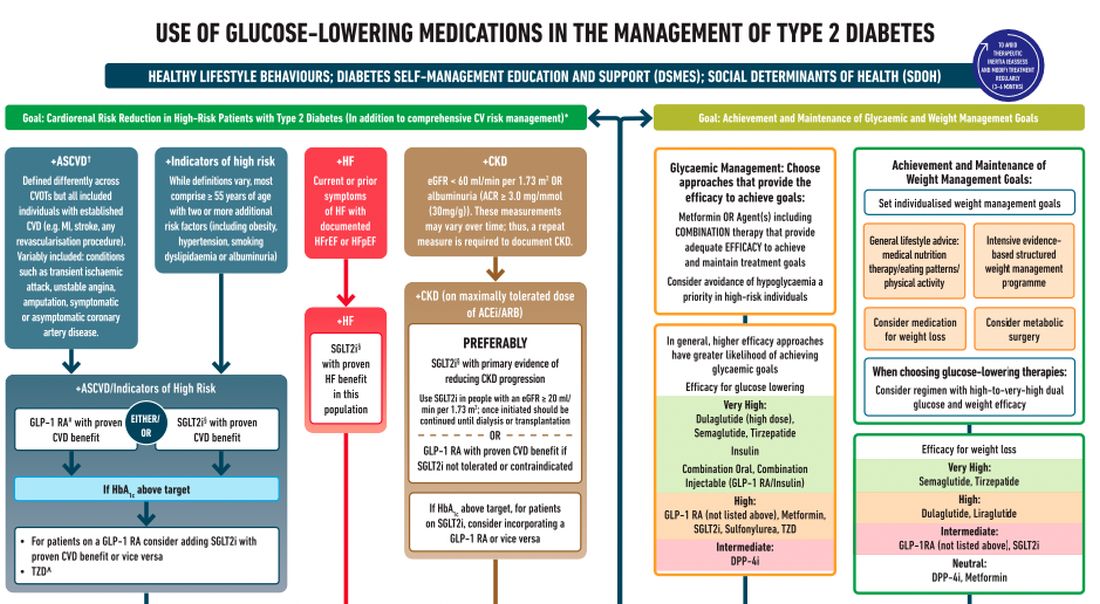

New recommendations for hyperglycemia management

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

RSV causes 1 in 50 deaths in children under age 5: European study

But RSV – formally known as respiratory syncytial virus – is also a problem in high-income nations. In those countries, 1 in 56 otherwise healthy babies are hospitalized with RSV during their first year of life, said the study, which was published in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Researchers looked at the health records of 9,154 infants born between July 1, 2017, and July 31, 2020, who were treated at health centers across Europe. Previous studies have concentrated on babies with preexisting conditions, but this one looked at otherwise healthy children, researchers said.

“This is the lowest-risk baby who is being hospitalized for this, so really, numbers are really much higher than I think some people would have guessed,” said study coauthor Louis Bont, MD, a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, according to CNN. He is also chairman of the ReSViNET foundation, which aims to reduce RSV infection globally.

The study said more than 97% of deaths from RSV occur in low-income and middle-income countries. The study concluded that “maternal vaccination and passive [immunization] could have a profound impact on the RSV burden.”

In developed nations, children who get RSV usually survive because they have access to ventilators and other health care equipment. Still, just being treated for RSV can have long-range negative effects on a child’s health, Kristina Deeter, MD, chair of pediatrics at the University of Nevada, Reno, told CNN.

“Whether that is just traumatic psychosocial, emotional issues after hospitalization or even having more vulnerable lungs – you can develop asthma later on, for instance, if you’ve had a really severe infection at a young age – it can damage your lungs permanently,” she said of the study. “It’s still an important virus in our world and something that we really focus on.”

The Lancet study was published days after the CDC warned public health officials that respiratory viruses, including RSV, are surging among children across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

But RSV – formally known as respiratory syncytial virus – is also a problem in high-income nations. In those countries, 1 in 56 otherwise healthy babies are hospitalized with RSV during their first year of life, said the study, which was published in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Researchers looked at the health records of 9,154 infants born between July 1, 2017, and July 31, 2020, who were treated at health centers across Europe. Previous studies have concentrated on babies with preexisting conditions, but this one looked at otherwise healthy children, researchers said.

“This is the lowest-risk baby who is being hospitalized for this, so really, numbers are really much higher than I think some people would have guessed,” said study coauthor Louis Bont, MD, a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, according to CNN. He is also chairman of the ReSViNET foundation, which aims to reduce RSV infection globally.

The study said more than 97% of deaths from RSV occur in low-income and middle-income countries. The study concluded that “maternal vaccination and passive [immunization] could have a profound impact on the RSV burden.”

In developed nations, children who get RSV usually survive because they have access to ventilators and other health care equipment. Still, just being treated for RSV can have long-range negative effects on a child’s health, Kristina Deeter, MD, chair of pediatrics at the University of Nevada, Reno, told CNN.

“Whether that is just traumatic psychosocial, emotional issues after hospitalization or even having more vulnerable lungs – you can develop asthma later on, for instance, if you’ve had a really severe infection at a young age – it can damage your lungs permanently,” she said of the study. “It’s still an important virus in our world and something that we really focus on.”

The Lancet study was published days after the CDC warned public health officials that respiratory viruses, including RSV, are surging among children across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

But RSV – formally known as respiratory syncytial virus – is also a problem in high-income nations. In those countries, 1 in 56 otherwise healthy babies are hospitalized with RSV during their first year of life, said the study, which was published in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Researchers looked at the health records of 9,154 infants born between July 1, 2017, and July 31, 2020, who were treated at health centers across Europe. Previous studies have concentrated on babies with preexisting conditions, but this one looked at otherwise healthy children, researchers said.

“This is the lowest-risk baby who is being hospitalized for this, so really, numbers are really much higher than I think some people would have guessed,” said study coauthor Louis Bont, MD, a professor of pediatric infectious diseases at Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, according to CNN. He is also chairman of the ReSViNET foundation, which aims to reduce RSV infection globally.

The study said more than 97% of deaths from RSV occur in low-income and middle-income countries. The study concluded that “maternal vaccination and passive [immunization] could have a profound impact on the RSV burden.”

In developed nations, children who get RSV usually survive because they have access to ventilators and other health care equipment. Still, just being treated for RSV can have long-range negative effects on a child’s health, Kristina Deeter, MD, chair of pediatrics at the University of Nevada, Reno, told CNN.

“Whether that is just traumatic psychosocial, emotional issues after hospitalization or even having more vulnerable lungs – you can develop asthma later on, for instance, if you’ve had a really severe infection at a young age – it can damage your lungs permanently,” she said of the study. “It’s still an important virus in our world and something that we really focus on.”

The Lancet study was published days after the CDC warned public health officials that respiratory viruses, including RSV, are surging among children across the country.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Meditation equal to first-line medication for anxiety

“I would encourage clinicians to list meditation training as one possible treatment option for patients who are diagnosed with anxiety disorders. Doctors should feel comfortable recommending in-person, group-based meditation classes,” study investigator Elizabeth A. Hoge, MD, director, Anxiety Disorders Research Program, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Screening recommended

Anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety, social anxiety, panic disorder, and agoraphobia, are the most common type of mental disorder, affecting an estimated 301 million people worldwide. Owing to their high prevalence, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for anxiety disorders.

Effective treatments for anxiety disorders include medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy. However, not all patients have access to these interventions, respond to them, or are comfortable seeking care in a psychiatric setting.

Mindfulness meditation, which has risen in popularity in recent years, may help people experiencing intrusive, anxious thoughts. “By practicing mindfulness meditation, people learn not to be overwhelmed by those thoughts,” said Dr. Hoge.

The study included 276 adult patients with an anxiety disorder, mostly generalized anxiety or social anxiety. The mean age of the study population was 33 years; 75% were women, 59% were White, 15% were Black, and 20% were Asian.

Researchers randomly assigned 136 patients to receive MBSR and 140 to receive the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor escitalopram, a first-line medication for treating anxiety disorders.

The MBSR intervention included a weekly 2.5-hour class and a day-long weekend class. Participants also completed daily 45-minute guided meditation sessions at home. They learned mindfulness meditation exercises, including breath awareness, body scanning, and mindful movement.

Those in the escitalopram group initially received 10 mg of the oral drug daily. The dose was increased to 20 mg daily at week 2 if well tolerated.

The primary outcome was the score on the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) scale for anxiety, assessed by clinicians blinded to treatment allocation. This instrument measures overall symptom severity on a scale from 1 (not at all ill) to 7 (most extremely ill) and can be used to assess different types of anxiety disorders, said Dr. Hoge.

Among the 208 participants who completed the study, the baseline mean CGI-S score was 4.44 for MBSR and 4.51 for escitalopram. At week 8, on the CGI-S scale, the MBSR group’s score improved by a mean of 1.35 points, and the escitalopram group’s score improved by 1.43 points (difference of –0.07; 95% CI, –0.38 to 0.23; P = .65).

The lower end of the confidence interval (–0.38) was smaller than the prespecified noninferiority margin of –0.495, indicating noninferiority of MBSR, compared with escitalopram.

Remarkable results

“What was remarkable was that the medication worked great, like it always does, but the meditation also worked great; we saw about a 30% drop in symptoms for both groups,” said Dr. Hoge. “That helps us know that meditation, and in particular mindfulness meditation, could be useful as a first-line treatment for patients with anxiety disorders.”

The patient-reported outcome of the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale also showed no significant group differences. “It’s important to have the self-reports, because that gives us two ways to look at the information,” said Dr. Hoge.

Anecdotally, participants noted that the meditation helped with their personal relationships and with being “kinder to themselves,” said Dr. Hoge. “In meditation, there’s an implicit teaching to be accepting and nonjudgmental towards your own thoughts, and that teaches people to be more self-compassionate.”

Just over 78% of patients in the escitalopram group had at least one treatment-related adverse event (AE), which included sleep disturbances, nausea, fatigue, and headache, compared with 15.4% in the MBSR group.

The most common AE in the meditation group was anxiety, which is “counterintuitive” but represents “a momentary anxiety,” said Dr. Hoge. “People who are meditating have feelings come up that maybe they didn’t pay attention to before. This gives them an opportunity to process through those emotions.”

Fatigue was the next most common AE for meditators, which “makes sense,” since they’re putting away their phones and not being stimulated, said Dr. Hoge.

MBSR was delivered in person, which limits extrapolation to mindfulness apps or programs delivered over the internet. Dr. Hoge believes apps would likely be less effective because they don’t have the face-to-face component, instructors available for consultation, or fellow participants contributing group support.

But online classes might work if “the exact same class,” including all its components, is moved online, she said.

MBSR is available in all major U.S. cities, doesn’t require finding a therapist, and is available outside a mental health environment – for example, at yoga centers and some places of employment. Anyone can learn MBSR, although it takes time and commitment, said Dr. Hoge.

A time-tested intervention

Commenting on the study, psychiatrist Gregory Scott Brown, MD, affiliate faculty, University of Texas Dell Medical School, and author of “The Self-Healing Mind: An Essential Five-Step Practice for Overcoming Anxiety and Depression and Revitalizing Your Life,” said the results aren’t surprising inasmuch as mindfulness, including spirituality, breath work, and meditation, is a “time-tested and evidence-based” intervention.

“I’m encouraged by the fact studies like this are now being conducted and there’s more evidence that supports these mindfulness-based interventions, so they can start to make their way into standard-of-care treatments.” he said.

He noted that mindfulness can produce “long-term, sustainable improvements” and that the 45-minute daily home exercise included in the study “is not a huge time commitment when you talk about benefits you can potentially glean from incorporating that time.”

Because most study participants were women and “men are anxious too,” Dr. Brown said he would like to see the study replicated “with a more diverse pool of participants.”

The study was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Hoge and Dr. Brown have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I would encourage clinicians to list meditation training as one possible treatment option for patients who are diagnosed with anxiety disorders. Doctors should feel comfortable recommending in-person, group-based meditation classes,” study investigator Elizabeth A. Hoge, MD, director, Anxiety Disorders Research Program, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Screening recommended

Anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety, social anxiety, panic disorder, and agoraphobia, are the most common type of mental disorder, affecting an estimated 301 million people worldwide. Owing to their high prevalence, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for anxiety disorders.

Effective treatments for anxiety disorders include medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy. However, not all patients have access to these interventions, respond to them, or are comfortable seeking care in a psychiatric setting.

Mindfulness meditation, which has risen in popularity in recent years, may help people experiencing intrusive, anxious thoughts. “By practicing mindfulness meditation, people learn not to be overwhelmed by those thoughts,” said Dr. Hoge.

The study included 276 adult patients with an anxiety disorder, mostly generalized anxiety or social anxiety. The mean age of the study population was 33 years; 75% were women, 59% were White, 15% were Black, and 20% were Asian.

Researchers randomly assigned 136 patients to receive MBSR and 140 to receive the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor escitalopram, a first-line medication for treating anxiety disorders.

The MBSR intervention included a weekly 2.5-hour class and a day-long weekend class. Participants also completed daily 45-minute guided meditation sessions at home. They learned mindfulness meditation exercises, including breath awareness, body scanning, and mindful movement.

Those in the escitalopram group initially received 10 mg of the oral drug daily. The dose was increased to 20 mg daily at week 2 if well tolerated.

The primary outcome was the score on the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) scale for anxiety, assessed by clinicians blinded to treatment allocation. This instrument measures overall symptom severity on a scale from 1 (not at all ill) to 7 (most extremely ill) and can be used to assess different types of anxiety disorders, said Dr. Hoge.

Among the 208 participants who completed the study, the baseline mean CGI-S score was 4.44 for MBSR and 4.51 for escitalopram. At week 8, on the CGI-S scale, the MBSR group’s score improved by a mean of 1.35 points, and the escitalopram group’s score improved by 1.43 points (difference of –0.07; 95% CI, –0.38 to 0.23; P = .65).

The lower end of the confidence interval (–0.38) was smaller than the prespecified noninferiority margin of –0.495, indicating noninferiority of MBSR, compared with escitalopram.

Remarkable results

“What was remarkable was that the medication worked great, like it always does, but the meditation also worked great; we saw about a 30% drop in symptoms for both groups,” said Dr. Hoge. “That helps us know that meditation, and in particular mindfulness meditation, could be useful as a first-line treatment for patients with anxiety disorders.”

The patient-reported outcome of the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale also showed no significant group differences. “It’s important to have the self-reports, because that gives us two ways to look at the information,” said Dr. Hoge.

Anecdotally, participants noted that the meditation helped with their personal relationships and with being “kinder to themselves,” said Dr. Hoge. “In meditation, there’s an implicit teaching to be accepting and nonjudgmental towards your own thoughts, and that teaches people to be more self-compassionate.”

Just over 78% of patients in the escitalopram group had at least one treatment-related adverse event (AE), which included sleep disturbances, nausea, fatigue, and headache, compared with 15.4% in the MBSR group.

The most common AE in the meditation group was anxiety, which is “counterintuitive” but represents “a momentary anxiety,” said Dr. Hoge. “People who are meditating have feelings come up that maybe they didn’t pay attention to before. This gives them an opportunity to process through those emotions.”

Fatigue was the next most common AE for meditators, which “makes sense,” since they’re putting away their phones and not being stimulated, said Dr. Hoge.

MBSR was delivered in person, which limits extrapolation to mindfulness apps or programs delivered over the internet. Dr. Hoge believes apps would likely be less effective because they don’t have the face-to-face component, instructors available for consultation, or fellow participants contributing group support.

But online classes might work if “the exact same class,” including all its components, is moved online, she said.

MBSR is available in all major U.S. cities, doesn’t require finding a therapist, and is available outside a mental health environment – for example, at yoga centers and some places of employment. Anyone can learn MBSR, although it takes time and commitment, said Dr. Hoge.

A time-tested intervention

Commenting on the study, psychiatrist Gregory Scott Brown, MD, affiliate faculty, University of Texas Dell Medical School, and author of “The Self-Healing Mind: An Essential Five-Step Practice for Overcoming Anxiety and Depression and Revitalizing Your Life,” said the results aren’t surprising inasmuch as mindfulness, including spirituality, breath work, and meditation, is a “time-tested and evidence-based” intervention.

“I’m encouraged by the fact studies like this are now being conducted and there’s more evidence that supports these mindfulness-based interventions, so they can start to make their way into standard-of-care treatments.” he said.

He noted that mindfulness can produce “long-term, sustainable improvements” and that the 45-minute daily home exercise included in the study “is not a huge time commitment when you talk about benefits you can potentially glean from incorporating that time.”

Because most study participants were women and “men are anxious too,” Dr. Brown said he would like to see the study replicated “with a more diverse pool of participants.”

The study was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Hoge and Dr. Brown have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I would encourage clinicians to list meditation training as one possible treatment option for patients who are diagnosed with anxiety disorders. Doctors should feel comfortable recommending in-person, group-based meditation classes,” study investigator Elizabeth A. Hoge, MD, director, Anxiety Disorders Research Program, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Screening recommended

Anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety, social anxiety, panic disorder, and agoraphobia, are the most common type of mental disorder, affecting an estimated 301 million people worldwide. Owing to their high prevalence, the United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for anxiety disorders.

Effective treatments for anxiety disorders include medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy. However, not all patients have access to these interventions, respond to them, or are comfortable seeking care in a psychiatric setting.

Mindfulness meditation, which has risen in popularity in recent years, may help people experiencing intrusive, anxious thoughts. “By practicing mindfulness meditation, people learn not to be overwhelmed by those thoughts,” said Dr. Hoge.

The study included 276 adult patients with an anxiety disorder, mostly generalized anxiety or social anxiety. The mean age of the study population was 33 years; 75% were women, 59% were White, 15% were Black, and 20% were Asian.

Researchers randomly assigned 136 patients to receive MBSR and 140 to receive the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor escitalopram, a first-line medication for treating anxiety disorders.

The MBSR intervention included a weekly 2.5-hour class and a day-long weekend class. Participants also completed daily 45-minute guided meditation sessions at home. They learned mindfulness meditation exercises, including breath awareness, body scanning, and mindful movement.

Those in the escitalopram group initially received 10 mg of the oral drug daily. The dose was increased to 20 mg daily at week 2 if well tolerated.

The primary outcome was the score on the Clinical Global Impression of Severity (CGI-S) scale for anxiety, assessed by clinicians blinded to treatment allocation. This instrument measures overall symptom severity on a scale from 1 (not at all ill) to 7 (most extremely ill) and can be used to assess different types of anxiety disorders, said Dr. Hoge.

Among the 208 participants who completed the study, the baseline mean CGI-S score was 4.44 for MBSR and 4.51 for escitalopram. At week 8, on the CGI-S scale, the MBSR group’s score improved by a mean of 1.35 points, and the escitalopram group’s score improved by 1.43 points (difference of –0.07; 95% CI, –0.38 to 0.23; P = .65).

The lower end of the confidence interval (–0.38) was smaller than the prespecified noninferiority margin of –0.495, indicating noninferiority of MBSR, compared with escitalopram.

Remarkable results

“What was remarkable was that the medication worked great, like it always does, but the meditation also worked great; we saw about a 30% drop in symptoms for both groups,” said Dr. Hoge. “That helps us know that meditation, and in particular mindfulness meditation, could be useful as a first-line treatment for patients with anxiety disorders.”

The patient-reported outcome of the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale also showed no significant group differences. “It’s important to have the self-reports, because that gives us two ways to look at the information,” said Dr. Hoge.

Anecdotally, participants noted that the meditation helped with their personal relationships and with being “kinder to themselves,” said Dr. Hoge. “In meditation, there’s an implicit teaching to be accepting and nonjudgmental towards your own thoughts, and that teaches people to be more self-compassionate.”

Just over 78% of patients in the escitalopram group had at least one treatment-related adverse event (AE), which included sleep disturbances, nausea, fatigue, and headache, compared with 15.4% in the MBSR group.

The most common AE in the meditation group was anxiety, which is “counterintuitive” but represents “a momentary anxiety,” said Dr. Hoge. “People who are meditating have feelings come up that maybe they didn’t pay attention to before. This gives them an opportunity to process through those emotions.”

Fatigue was the next most common AE for meditators, which “makes sense,” since they’re putting away their phones and not being stimulated, said Dr. Hoge.

MBSR was delivered in person, which limits extrapolation to mindfulness apps or programs delivered over the internet. Dr. Hoge believes apps would likely be less effective because they don’t have the face-to-face component, instructors available for consultation, or fellow participants contributing group support.

But online classes might work if “the exact same class,” including all its components, is moved online, she said.

MBSR is available in all major U.S. cities, doesn’t require finding a therapist, and is available outside a mental health environment – for example, at yoga centers and some places of employment. Anyone can learn MBSR, although it takes time and commitment, said Dr. Hoge.

A time-tested intervention

Commenting on the study, psychiatrist Gregory Scott Brown, MD, affiliate faculty, University of Texas Dell Medical School, and author of “The Self-Healing Mind: An Essential Five-Step Practice for Overcoming Anxiety and Depression and Revitalizing Your Life,” said the results aren’t surprising inasmuch as mindfulness, including spirituality, breath work, and meditation, is a “time-tested and evidence-based” intervention.

“I’m encouraged by the fact studies like this are now being conducted and there’s more evidence that supports these mindfulness-based interventions, so they can start to make their way into standard-of-care treatments.” he said.

He noted that mindfulness can produce “long-term, sustainable improvements” and that the 45-minute daily home exercise included in the study “is not a huge time commitment when you talk about benefits you can potentially glean from incorporating that time.”

Because most study participants were women and “men are anxious too,” Dr. Brown said he would like to see the study replicated “with a more diverse pool of participants.”

The study was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr. Hoge and Dr. Brown have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Imaging IDs brain activity related to dissociative symptoms

Results from a neuroimaging study showed that different dissociative symptoms were linked to hyperconnectivity within several key regions of the brain, including the central executive, default, and salience networks as well as decreased connectivity of the central executive and salience networks with other brain areas.

Depersonalization/derealization showed a different brain signature than partially dissociated intrusions, and participants with posttraumatic stress disorder showed a different brain signature, compared with those who had dissociative identity disorder (DID).

“Dissociation is a complex, subjective set of symptoms that are largely experienced internally and, contrary to media portrayal, are not usually overtly observable,” lead author Lauren Lebois, PhD, director of the Dissociative Disorders and Trauma Research Program, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“However, we have shown that you can objectively measure dissociation and link it to robust brain signatures. We hope these results will encourage clinicians to screen for dissociation and approach reports of these experiences seriously, empathetically, and with awareness that they can be treated effectively,” Dr. Lebois said.

The findings were published online in Neuropsychopharmacology.

Detachment, discontinuity

Pathological dissociation is “the experience of detachment from or discontinuity in one’s internal experience, sense of self, or surroundings” and is common in the aftermath of trauma, the investigators write.

Previous research into trauma-related pathological dissociation suggests it encompasses a range of experiences or “subtypes,” some of which frequently occur in PTSD and DID.

“Depersonalization and derealization involve feelings of detachment or disconnection from one’s sense of self, body, and environment,” the current researchers write. “Individuals report feeling like their body or surroundings are unreal or like they are in a movie.”

Dissociation also includes “experiences of self-alteration common in DID, in which people lose a sense of agency and ownership over their thoughts, emotions, actions, and body [and] experience some thoughts, emotions, etc. as partially dissociated intrusions,” Dr. Lebois said.

She added that dissociative symptoms are “common and disabling.” And dissociation and severe dissociative disorders such as DID “remain at best underappreciated and, at worst, frequently go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed,” with a high cost of stigmatization and misunderstanding preventing individuals from accessing effective treatment.

In addition, “given that DID disproportionately affects women, gender disparity is an important issue in this context,” Dr. Lebois noted.

Her team was motivated to conduct the study “to learn more about how different types of dissociation manifest in brain activity and to help combat the stigma around dissociation and DID.”

Filling the gap

The investigators drew on the “Triple Network” model of psychopathology, which “offers an integrative framework based in systems neuroscience for understanding cognitive and affective dysfunction across psychiatric conditions,” they write.

This model “implicates altered intrinsic organization and interactions between three large-scale brain networks across disorders,” they add.

The brain networks included in the study were the right-lateralized central executive network (rCEN), with the lateral frontoparietal brain region; the medial temporal subnetwork of the default network (tDN), with the medial frontoparietal brain region; and the cingulo-opercular subnetwork (cSN), with the midcingulo-insular brain region.

Previous neuroimaging research into dissociative disorders has implicated altered connectivity in these regions. However, although previous studies covered dissociation subtypes, they did not directly compare these subtypes. This study was designed to fill that gap, the investigators note.

They assessed 91 women with and without a history of childhood trauma, current PTSD, and with varying degrees of dissociation.

This included 19 with conventional PTSD (mean age, 33.4 years), 18 with PTSD dissociative subtype (mean age, 29.5 years), 26 with DID (mean age, 37.4 years), and 28 who acted as the healthy control group (mean age, 32 years).

Participants completed several scales regarding symptoms of PTSD, dissociation, and childhood trauma. They also underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging. Covariates included age, childhood maltreatment, and PTSD severity.

Connectivity alterations

Results showed the rCEN was “most impacted” by pathological dissociation, with 39 clusters linked to connectivity alterations.

Ten clusters within tDN exhibited within-network hyperconnectivity related to dissociation but only of the depersonalization/derealization subtype.

Eight clusters within cSN were linked to dissociation – specifically, within-network hyperconnectivity and decreased connectivity between regions in rCEN with cSN, with “no significant unique contributions of dissociation subtypes,” the researchers report.

“Depersonalization and derealization symptoms were associated with increased communication between a brain network involved in reasoning, attention, inhibition, and working memory and a brain region implicated in out-of-body experiences. This may, in part, contribute to depersonalization/derealization feelings of detachment, strangeness or unreality experienced with your body and surroundings,” Dr. Lebois said.

“In contrast, partially dissociated intrusion symptoms central to DID were linked to increased communication between a brain network involved in autobiographical memory and your sense of self and a brain network involved in reasoning, attention, inhibition, and working memory,” she added.

She noted that this matches how patients with DID describe their mental experiences: as sometimes feeling as if they lost a sense of ownership over their own thoughts and feelings, which can “intrude into their mental landscape.”

In the future, Dr. Lebois hopes that “we may be able to monitor dissociative brain signatures during psychotherapy to help assess recovery or relapse, or we could target brain activity directly with neurofeedback or neuromodulatory techniques as a dissociation treatment in and of itself.”

A first step?

Commenting on the study, Richard Loewenstein, MD, adjunct professor, department of psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, called the paper a “first step in more sophisticated studies of pathological dissociation using cutting-edge concepts of brain connectivity, methodology based on naturalistic, dimensional symptoms categories, and innovative statistical methods.”

Dr. Loewenstein, who was not involved with the current study, added that there is an “oversimplified conflation of hallucinations and other symptoms of dissociation with psychosis.” So studies may “incorrectly relate phenomena such as racism-based trauma to psychosis, rather than pathological dissociation and racism-based PTSD,” he said.

He noted that the implications are “profound, as pathological dissociation is not treatable with antipsychotic medications and requires treatment with psychotherapy specifically targeting symptoms of pathological dissociation.”

The study was funded by the Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research and the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Lebois reported unpaid membership on the Scientific Committee for the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation, grant support from the NIMH and the Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research, and spousal IP payments from Vanderbilt University for technology licensed to Acadia Pharmaceuticals unrelated to the present work. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original paper. Dr. Loewenstein has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from a neuroimaging study showed that different dissociative symptoms were linked to hyperconnectivity within several key regions of the brain, including the central executive, default, and salience networks as well as decreased connectivity of the central executive and salience networks with other brain areas.

Depersonalization/derealization showed a different brain signature than partially dissociated intrusions, and participants with posttraumatic stress disorder showed a different brain signature, compared with those who had dissociative identity disorder (DID).

“Dissociation is a complex, subjective set of symptoms that are largely experienced internally and, contrary to media portrayal, are not usually overtly observable,” lead author Lauren Lebois, PhD, director of the Dissociative Disorders and Trauma Research Program, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“However, we have shown that you can objectively measure dissociation and link it to robust brain signatures. We hope these results will encourage clinicians to screen for dissociation and approach reports of these experiences seriously, empathetically, and with awareness that they can be treated effectively,” Dr. Lebois said.

The findings were published online in Neuropsychopharmacology.

Detachment, discontinuity

Pathological dissociation is “the experience of detachment from or discontinuity in one’s internal experience, sense of self, or surroundings” and is common in the aftermath of trauma, the investigators write.

Previous research into trauma-related pathological dissociation suggests it encompasses a range of experiences or “subtypes,” some of which frequently occur in PTSD and DID.

“Depersonalization and derealization involve feelings of detachment or disconnection from one’s sense of self, body, and environment,” the current researchers write. “Individuals report feeling like their body or surroundings are unreal or like they are in a movie.”

Dissociation also includes “experiences of self-alteration common in DID, in which people lose a sense of agency and ownership over their thoughts, emotions, actions, and body [and] experience some thoughts, emotions, etc. as partially dissociated intrusions,” Dr. Lebois said.

She added that dissociative symptoms are “common and disabling.” And dissociation and severe dissociative disorders such as DID “remain at best underappreciated and, at worst, frequently go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed,” with a high cost of stigmatization and misunderstanding preventing individuals from accessing effective treatment.

In addition, “given that DID disproportionately affects women, gender disparity is an important issue in this context,” Dr. Lebois noted.

Her team was motivated to conduct the study “to learn more about how different types of dissociation manifest in brain activity and to help combat the stigma around dissociation and DID.”

Filling the gap

The investigators drew on the “Triple Network” model of psychopathology, which “offers an integrative framework based in systems neuroscience for understanding cognitive and affective dysfunction across psychiatric conditions,” they write.

This model “implicates altered intrinsic organization and interactions between three large-scale brain networks across disorders,” they add.

The brain networks included in the study were the right-lateralized central executive network (rCEN), with the lateral frontoparietal brain region; the medial temporal subnetwork of the default network (tDN), with the medial frontoparietal brain region; and the cingulo-opercular subnetwork (cSN), with the midcingulo-insular brain region.

Previous neuroimaging research into dissociative disorders has implicated altered connectivity in these regions. However, although previous studies covered dissociation subtypes, they did not directly compare these subtypes. This study was designed to fill that gap, the investigators note.

They assessed 91 women with and without a history of childhood trauma, current PTSD, and with varying degrees of dissociation.

This included 19 with conventional PTSD (mean age, 33.4 years), 18 with PTSD dissociative subtype (mean age, 29.5 years), 26 with DID (mean age, 37.4 years), and 28 who acted as the healthy control group (mean age, 32 years).

Participants completed several scales regarding symptoms of PTSD, dissociation, and childhood trauma. They also underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging. Covariates included age, childhood maltreatment, and PTSD severity.

Connectivity alterations

Results showed the rCEN was “most impacted” by pathological dissociation, with 39 clusters linked to connectivity alterations.

Ten clusters within tDN exhibited within-network hyperconnectivity related to dissociation but only of the depersonalization/derealization subtype.

Eight clusters within cSN were linked to dissociation – specifically, within-network hyperconnectivity and decreased connectivity between regions in rCEN with cSN, with “no significant unique contributions of dissociation subtypes,” the researchers report.

“Depersonalization and derealization symptoms were associated with increased communication between a brain network involved in reasoning, attention, inhibition, and working memory and a brain region implicated in out-of-body experiences. This may, in part, contribute to depersonalization/derealization feelings of detachment, strangeness or unreality experienced with your body and surroundings,” Dr. Lebois said.

“In contrast, partially dissociated intrusion symptoms central to DID were linked to increased communication between a brain network involved in autobiographical memory and your sense of self and a brain network involved in reasoning, attention, inhibition, and working memory,” she added.

She noted that this matches how patients with DID describe their mental experiences: as sometimes feeling as if they lost a sense of ownership over their own thoughts and feelings, which can “intrude into their mental landscape.”

In the future, Dr. Lebois hopes that “we may be able to monitor dissociative brain signatures during psychotherapy to help assess recovery or relapse, or we could target brain activity directly with neurofeedback or neuromodulatory techniques as a dissociation treatment in and of itself.”

A first step?

Commenting on the study, Richard Loewenstein, MD, adjunct professor, department of psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, called the paper a “first step in more sophisticated studies of pathological dissociation using cutting-edge concepts of brain connectivity, methodology based on naturalistic, dimensional symptoms categories, and innovative statistical methods.”

Dr. Loewenstein, who was not involved with the current study, added that there is an “oversimplified conflation of hallucinations and other symptoms of dissociation with psychosis.” So studies may “incorrectly relate phenomena such as racism-based trauma to psychosis, rather than pathological dissociation and racism-based PTSD,” he said.

He noted that the implications are “profound, as pathological dissociation is not treatable with antipsychotic medications and requires treatment with psychotherapy specifically targeting symptoms of pathological dissociation.”

The study was funded by the Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research and the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Lebois reported unpaid membership on the Scientific Committee for the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation, grant support from the NIMH and the Julia Kasparian Fund for Neuroscience Research, and spousal IP payments from Vanderbilt University for technology licensed to Acadia Pharmaceuticals unrelated to the present work. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original paper. Dr. Loewenstein has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from a neuroimaging study showed that different dissociative symptoms were linked to hyperconnectivity within several key regions of the brain, including the central executive, default, and salience networks as well as decreased connectivity of the central executive and salience networks with other brain areas.

Depersonalization/derealization showed a different brain signature than partially dissociated intrusions, and participants with posttraumatic stress disorder showed a different brain signature, compared with those who had dissociative identity disorder (DID).

“Dissociation is a complex, subjective set of symptoms that are largely experienced internally and, contrary to media portrayal, are not usually overtly observable,” lead author Lauren Lebois, PhD, director of the Dissociative Disorders and Trauma Research Program, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

“However, we have shown that you can objectively measure dissociation and link it to robust brain signatures. We hope these results will encourage clinicians to screen for dissociation and approach reports of these experiences seriously, empathetically, and with awareness that they can be treated effectively,” Dr. Lebois said.

The findings were published online in Neuropsychopharmacology.

Detachment, discontinuity

Pathological dissociation is “the experience of detachment from or discontinuity in one’s internal experience, sense of self, or surroundings” and is common in the aftermath of trauma, the investigators write.

Previous research into trauma-related pathological dissociation suggests it encompasses a range of experiences or “subtypes,” some of which frequently occur in PTSD and DID.

“Depersonalization and derealization involve feelings of detachment or disconnection from one’s sense of self, body, and environment,” the current researchers write. “Individuals report feeling like their body or surroundings are unreal or like they are in a movie.”

Dissociation also includes “experiences of self-alteration common in DID, in which people lose a sense of agency and ownership over their thoughts, emotions, actions, and body [and] experience some thoughts, emotions, etc. as partially dissociated intrusions,” Dr. Lebois said.

She added that dissociative symptoms are “common and disabling.” And dissociation and severe dissociative disorders such as DID “remain at best underappreciated and, at worst, frequently go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed,” with a high cost of stigmatization and misunderstanding preventing individuals from accessing effective treatment.

In addition, “given that DID disproportionately affects women, gender disparity is an important issue in this context,” Dr. Lebois noted.

Her team was motivated to conduct the study “to learn more about how different types of dissociation manifest in brain activity and to help combat the stigma around dissociation and DID.”

Filling the gap

The investigators drew on the “Triple Network” model of psychopathology, which “offers an integrative framework based in systems neuroscience for understanding cognitive and affective dysfunction across psychiatric conditions,” they write.

This model “implicates altered intrinsic organization and interactions between three large-scale brain networks across disorders,” they add.

The brain networks included in the study were the right-lateralized central executive network (rCEN), with the lateral frontoparietal brain region; the medial temporal subnetwork of the default network (tDN), with the medial frontoparietal brain region; and the cingulo-opercular subnetwork (cSN), with the midcingulo-insular brain region.

Previous neuroimaging research into dissociative disorders has implicated altered connectivity in these regions. However, although previous studies covered dissociation subtypes, they did not directly compare these subtypes. This study was designed to fill that gap, the investigators note.

They assessed 91 women with and without a history of childhood trauma, current PTSD, and with varying degrees of dissociation.

This included 19 with conventional PTSD (mean age, 33.4 years), 18 with PTSD dissociative subtype (mean age, 29.5 years), 26 with DID (mean age, 37.4 years), and 28 who acted as the healthy control group (mean age, 32 years).

Participants completed several scales regarding symptoms of PTSD, dissociation, and childhood trauma. They also underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging. Covariates included age, childhood maltreatment, and PTSD severity.

Connectivity alterations

Results showed the rCEN was “most impacted” by pathological dissociation, with 39 clusters linked to connectivity alterations.

Ten clusters within tDN exhibited within-network hyperconnectivity related to dissociation but only of the depersonalization/derealization subtype.

Eight clusters within cSN were linked to dissociation – specifically, within-network hyperconnectivity and decreased connectivity between regions in rCEN with cSN, with “no significant unique contributions of dissociation subtypes,” the researchers report.

“Depersonalization and derealization symptoms were associated with increased communication between a brain network involved in reasoning, attention, inhibition, and working memory and a brain region implicated in out-of-body experiences. This may, in part, contribute to depersonalization/derealization feelings of detachment, strangeness or unreality experienced with your body and surroundings,” Dr. Lebois said.

“In contrast, partially dissociated intrusion symptoms central to DID were linked to increased communication between a brain network involved in autobiographical memory and your sense of self and a brain network involved in reasoning, attention, inhibition, and working memory,” she added.

She noted that this matches how patients with DID describe their mental experiences: as sometimes feeling as if they lost a sense of ownership over their own thoughts and feelings, which can “intrude into their mental landscape.”

In the future, Dr. Lebois hopes that “we may be able to monitor dissociative brain signatures during psychotherapy to help assess recovery or relapse, or we could target brain activity directly with neurofeedback or neuromodulatory techniques as a dissociation treatment in and of itself.”

A first step?