User login

Nail Salon Safety: From Nail Dystrophy to Acrylate Contact Allergies

As residents, it is important to understand the steps of the manicuring process and be able to inform patients on how to maintain optimal nail health while continuing to go to nail salons. Most patients are not aware of the possible allergic, traumatic, and/or infectious complications of manicuring their nails. There are practical steps that can be taken to prevent nail issues, such as avoiding cutting one’s cuticles or using allergen-free nail polishes. These simple fixes can make a big difference in long-term nail health in our patients.

Nail Polish Application Process

The nails are first soaked in a warm soapy solution to soften the nail plate and cuticles.1 Then the nail tips and plates are filed and occasionally are smoothed with a drill. The cuticles are cut with a cuticle cutter. Nail polish—base coat, color enamel, and top coat—is then applied to the nail. Acrylic or sculptured nails and gel and dip manicures are composed of chemical monomers and polymers that harden either at room temperature or through UV or light-emitting diode (LED) exposure. The chemicals in these products can damage nails and cause allergic reactions.

Contact Dermatitis

Approximately 2% of individuals have been found to have allergic or irritant contact dermatitis to nail care products. The top 5 allergens implicated in nail products are (1) 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, (2) methyl methacrylate, (3) ethyl acrylate, (4) ethyl-2-cyanoacrylate, and (5) tosylamide.2 Methyl methacrylate was banned in 1974 by the US Food and Drug Administration due to reports of severe contact dermatitis, paronychia, and nail dystrophy.3 Due to their potent sensitizing effects, acrylates were named the contact allergen of the year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.3

Acrylates are plastic products formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid.4 Artificial sculptured nails are created by mixing powdered polymethyl methacrylate polymers and liquid ethyl or isobutyl methacrylate monomers and then applying this mixture to the nail plate.5 Gel and powder nails employ a mixture that is similar to acrylic powders, which require UV or LED radiation to polymerize and harden on the nail plate.

Tosylamide, or tosylamide formaldehyde resin, is another potent allergen that promotes adhesion of the enamel to the nail.6 It is important to note that sensitization may develop months to years after using artificial nails.

Clinical features of contact allergy secondary to nail polish can vary. Some patients experience severe periungual dermatitis. Others can present with facial or eyelid dermatitis due to exposure to airborne particles of acrylates or from contact with fingertips bearing acrylic nails.6,7 If inhaled, acrylates also can cause wheezing asthma or allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.

Common Onychodystrophies

Damage to the natural nail plate is inevitable with continued wear of sculptured nails. With 2 to 4 months of consecutive wear, the natural nails turn yellow, brittle, and weak.5 One study noted that the thickness of an individual’s left thumb nail plate thinned from 0.059 cm to 0.03 cm after a gel manicure was removed from the nail.8 Nail injuries due to manicuring include keratin granulations, onycholysis, pincer nail deformities, pseudopsoriatic nails, lamellar onychoschizia, transverse leukonychia, and ingrown nails.6 One interesting nail dystrophy reported secondary to gel manicures is pterygium inversum unguis or a ventral pterygium that causes an abnormal painful adherence of the hyponychium to the ventral surface of the nail plate. Patients prone to developing pterygium inversum unguis can experience sensitivity, pain, or burning sensations during LED or UVA light exposure.9

Infections

In addition to contact allergies and nail dystrophies, each step of the manicuring process, such as cutting cuticles, presents opportunities for infectious agents to enter the nail fold. Acute or chronic paronychia, or inflammation of the nail fold, most commonly is caused by bacterial infections with Staphylococcus aureus. Green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa also is common.1 Onychomycosis due to Trichophyton rubrum is one of the most frequent fungal infections contracted at nail salons. Mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium fortuitum also have been implicated in infections from salons, as they can be found in the jets of pedicure spas, which are not sanitized regularly.10

Final Thoughts

Nail cosmetics are an integral part of many patients’ lives. Being able to educate yourself and your patients on the hazards of nail salons can help them avoid painful infections, contact allergies, and acute to chronic nail deformities. It is important for residents to be aware of the different dermatoses that can arise in men and women who frequent nail salons as the popularity of the nail beauty industry continues to rise.

- Reinecke JK, Hinshaw MA. Nail health in women. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:73-79. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.006

- Warshaw EM, Voller LM, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with nail care products: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001-2016. Dermatitis. 2020;31:191-201. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000583

- Militello M, Hu S, Laughter M, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society allergens of the year 2000 to 2020 [published online April 25, 2020]. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:309-320. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.02.011

- Kucharczyk M, Słowik-Rylska M, Cyran-Stemplewska S, et al. Acrylates as a significant cause of allergic contact dermatitis: new sources of exposure. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:555-560. doi:10.5114/ada.2020.95848

- Draelos ZD. Cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:2587-2588.

- Iorizzo M, Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Nail cosmetics in nail disorders.J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:53-58. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00290.x

- Maio P, Carvalho R, Amaro C, et al. Letter: allergic contact dermatitis from sculptured acrylic nails: special presentation with a possible airborne pattern. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:13.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00595.x

- Cervantes J, Sanchez M, Eber AE, et al. Pterygium inversum unguis secondary to gel polish [published online October 16, 2017]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:160-163. doi:10.1111/jdv.14603

- Vugia DJ, Jang Y, Zizek C, et al. Mycobacteria in nail salon whirlpool footbaths, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:616-618. doi:10.3201/eid1104.040936

As residents, it is important to understand the steps of the manicuring process and be able to inform patients on how to maintain optimal nail health while continuing to go to nail salons. Most patients are not aware of the possible allergic, traumatic, and/or infectious complications of manicuring their nails. There are practical steps that can be taken to prevent nail issues, such as avoiding cutting one’s cuticles or using allergen-free nail polishes. These simple fixes can make a big difference in long-term nail health in our patients.

Nail Polish Application Process

The nails are first soaked in a warm soapy solution to soften the nail plate and cuticles.1 Then the nail tips and plates are filed and occasionally are smoothed with a drill. The cuticles are cut with a cuticle cutter. Nail polish—base coat, color enamel, and top coat—is then applied to the nail. Acrylic or sculptured nails and gel and dip manicures are composed of chemical monomers and polymers that harden either at room temperature or through UV or light-emitting diode (LED) exposure. The chemicals in these products can damage nails and cause allergic reactions.

Contact Dermatitis

Approximately 2% of individuals have been found to have allergic or irritant contact dermatitis to nail care products. The top 5 allergens implicated in nail products are (1) 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, (2) methyl methacrylate, (3) ethyl acrylate, (4) ethyl-2-cyanoacrylate, and (5) tosylamide.2 Methyl methacrylate was banned in 1974 by the US Food and Drug Administration due to reports of severe contact dermatitis, paronychia, and nail dystrophy.3 Due to their potent sensitizing effects, acrylates were named the contact allergen of the year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.3

Acrylates are plastic products formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid.4 Artificial sculptured nails are created by mixing powdered polymethyl methacrylate polymers and liquid ethyl or isobutyl methacrylate monomers and then applying this mixture to the nail plate.5 Gel and powder nails employ a mixture that is similar to acrylic powders, which require UV or LED radiation to polymerize and harden on the nail plate.

Tosylamide, or tosylamide formaldehyde resin, is another potent allergen that promotes adhesion of the enamel to the nail.6 It is important to note that sensitization may develop months to years after using artificial nails.

Clinical features of contact allergy secondary to nail polish can vary. Some patients experience severe periungual dermatitis. Others can present with facial or eyelid dermatitis due to exposure to airborne particles of acrylates or from contact with fingertips bearing acrylic nails.6,7 If inhaled, acrylates also can cause wheezing asthma or allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.

Common Onychodystrophies

Damage to the natural nail plate is inevitable with continued wear of sculptured nails. With 2 to 4 months of consecutive wear, the natural nails turn yellow, brittle, and weak.5 One study noted that the thickness of an individual’s left thumb nail plate thinned from 0.059 cm to 0.03 cm after a gel manicure was removed from the nail.8 Nail injuries due to manicuring include keratin granulations, onycholysis, pincer nail deformities, pseudopsoriatic nails, lamellar onychoschizia, transverse leukonychia, and ingrown nails.6 One interesting nail dystrophy reported secondary to gel manicures is pterygium inversum unguis or a ventral pterygium that causes an abnormal painful adherence of the hyponychium to the ventral surface of the nail plate. Patients prone to developing pterygium inversum unguis can experience sensitivity, pain, or burning sensations during LED or UVA light exposure.9

Infections

In addition to contact allergies and nail dystrophies, each step of the manicuring process, such as cutting cuticles, presents opportunities for infectious agents to enter the nail fold. Acute or chronic paronychia, or inflammation of the nail fold, most commonly is caused by bacterial infections with Staphylococcus aureus. Green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa also is common.1 Onychomycosis due to Trichophyton rubrum is one of the most frequent fungal infections contracted at nail salons. Mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium fortuitum also have been implicated in infections from salons, as they can be found in the jets of pedicure spas, which are not sanitized regularly.10

Final Thoughts

Nail cosmetics are an integral part of many patients’ lives. Being able to educate yourself and your patients on the hazards of nail salons can help them avoid painful infections, contact allergies, and acute to chronic nail deformities. It is important for residents to be aware of the different dermatoses that can arise in men and women who frequent nail salons as the popularity of the nail beauty industry continues to rise.

As residents, it is important to understand the steps of the manicuring process and be able to inform patients on how to maintain optimal nail health while continuing to go to nail salons. Most patients are not aware of the possible allergic, traumatic, and/or infectious complications of manicuring their nails. There are practical steps that can be taken to prevent nail issues, such as avoiding cutting one’s cuticles or using allergen-free nail polishes. These simple fixes can make a big difference in long-term nail health in our patients.

Nail Polish Application Process

The nails are first soaked in a warm soapy solution to soften the nail plate and cuticles.1 Then the nail tips and plates are filed and occasionally are smoothed with a drill. The cuticles are cut with a cuticle cutter. Nail polish—base coat, color enamel, and top coat—is then applied to the nail. Acrylic or sculptured nails and gel and dip manicures are composed of chemical monomers and polymers that harden either at room temperature or through UV or light-emitting diode (LED) exposure. The chemicals in these products can damage nails and cause allergic reactions.

Contact Dermatitis

Approximately 2% of individuals have been found to have allergic or irritant contact dermatitis to nail care products. The top 5 allergens implicated in nail products are (1) 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, (2) methyl methacrylate, (3) ethyl acrylate, (4) ethyl-2-cyanoacrylate, and (5) tosylamide.2 Methyl methacrylate was banned in 1974 by the US Food and Drug Administration due to reports of severe contact dermatitis, paronychia, and nail dystrophy.3 Due to their potent sensitizing effects, acrylates were named the contact allergen of the year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.3

Acrylates are plastic products formed by polymerization of acrylic or methacrylic acid.4 Artificial sculptured nails are created by mixing powdered polymethyl methacrylate polymers and liquid ethyl or isobutyl methacrylate monomers and then applying this mixture to the nail plate.5 Gel and powder nails employ a mixture that is similar to acrylic powders, which require UV or LED radiation to polymerize and harden on the nail plate.

Tosylamide, or tosylamide formaldehyde resin, is another potent allergen that promotes adhesion of the enamel to the nail.6 It is important to note that sensitization may develop months to years after using artificial nails.

Clinical features of contact allergy secondary to nail polish can vary. Some patients experience severe periungual dermatitis. Others can present with facial or eyelid dermatitis due to exposure to airborne particles of acrylates or from contact with fingertips bearing acrylic nails.6,7 If inhaled, acrylates also can cause wheezing asthma or allergic rhinoconjunctivitis.

Common Onychodystrophies

Damage to the natural nail plate is inevitable with continued wear of sculptured nails. With 2 to 4 months of consecutive wear, the natural nails turn yellow, brittle, and weak.5 One study noted that the thickness of an individual’s left thumb nail plate thinned from 0.059 cm to 0.03 cm after a gel manicure was removed from the nail.8 Nail injuries due to manicuring include keratin granulations, onycholysis, pincer nail deformities, pseudopsoriatic nails, lamellar onychoschizia, transverse leukonychia, and ingrown nails.6 One interesting nail dystrophy reported secondary to gel manicures is pterygium inversum unguis or a ventral pterygium that causes an abnormal painful adherence of the hyponychium to the ventral surface of the nail plate. Patients prone to developing pterygium inversum unguis can experience sensitivity, pain, or burning sensations during LED or UVA light exposure.9

Infections

In addition to contact allergies and nail dystrophies, each step of the manicuring process, such as cutting cuticles, presents opportunities for infectious agents to enter the nail fold. Acute or chronic paronychia, or inflammation of the nail fold, most commonly is caused by bacterial infections with Staphylococcus aureus. Green nail syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa also is common.1 Onychomycosis due to Trichophyton rubrum is one of the most frequent fungal infections contracted at nail salons. Mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium fortuitum also have been implicated in infections from salons, as they can be found in the jets of pedicure spas, which are not sanitized regularly.10

Final Thoughts

Nail cosmetics are an integral part of many patients’ lives. Being able to educate yourself and your patients on the hazards of nail salons can help them avoid painful infections, contact allergies, and acute to chronic nail deformities. It is important for residents to be aware of the different dermatoses that can arise in men and women who frequent nail salons as the popularity of the nail beauty industry continues to rise.

- Reinecke JK, Hinshaw MA. Nail health in women. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:73-79. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.006

- Warshaw EM, Voller LM, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with nail care products: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001-2016. Dermatitis. 2020;31:191-201. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000583

- Militello M, Hu S, Laughter M, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society allergens of the year 2000 to 2020 [published online April 25, 2020]. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:309-320. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.02.011

- Kucharczyk M, Słowik-Rylska M, Cyran-Stemplewska S, et al. Acrylates as a significant cause of allergic contact dermatitis: new sources of exposure. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:555-560. doi:10.5114/ada.2020.95848

- Draelos ZD. Cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:2587-2588.

- Iorizzo M, Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Nail cosmetics in nail disorders.J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:53-58. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00290.x

- Maio P, Carvalho R, Amaro C, et al. Letter: allergic contact dermatitis from sculptured acrylic nails: special presentation with a possible airborne pattern. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:13.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00595.x

- Cervantes J, Sanchez M, Eber AE, et al. Pterygium inversum unguis secondary to gel polish [published online October 16, 2017]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:160-163. doi:10.1111/jdv.14603

- Vugia DJ, Jang Y, Zizek C, et al. Mycobacteria in nail salon whirlpool footbaths, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:616-618. doi:10.3201/eid1104.040936

- Reinecke JK, Hinshaw MA. Nail health in women. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:73-79. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.006

- Warshaw EM, Voller LM, Silverberg JI, et al. Contact dermatitis associated with nail care products: retrospective analysis of North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 2001-2016. Dermatitis. 2020;31:191-201. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000583

- Militello M, Hu S, Laughter M, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society allergens of the year 2000 to 2020 [published online April 25, 2020]. Dermatol Clin. 2020;38:309-320. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.02.011

- Kucharczyk M, Słowik-Rylska M, Cyran-Stemplewska S, et al. Acrylates as a significant cause of allergic contact dermatitis: new sources of exposure. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:555-560. doi:10.5114/ada.2020.95848

- Draelos ZD. Cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:2587-2588.

- Iorizzo M, Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Nail cosmetics in nail disorders.J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:53-58. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00290.x

- Maio P, Carvalho R, Amaro C, et al. Letter: allergic contact dermatitis from sculptured acrylic nails: special presentation with a possible airborne pattern. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:13.

- Chen AF, Chimento SM, Hu S, et al. Nail damage from gel polish manicure. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2012;11:27-29. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00595.x

- Cervantes J, Sanchez M, Eber AE, et al. Pterygium inversum unguis secondary to gel polish [published online October 16, 2017]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:160-163. doi:10.1111/jdv.14603

- Vugia DJ, Jang Y, Zizek C, et al. Mycobacteria in nail salon whirlpool footbaths, California. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:616-618. doi:10.3201/eid1104.040936

Resident Pearls

- Every step of the nail manicuring process presents opportunities for nail trauma, infections, and contact dermatitis.

- As residents, it is important to be aware of the hazards associated with nail salons and educate our patients accordingly.

- Nail health is essential to optimizing everyday work for our patients—whether it entails taking care of children, typing, or other hands-on activities.

COVID-19 and IPF: Fundamental similarities found

An AI-guided analysis of more than 1,000 human lung transcriptomic datasets found that COVID-19 resembles idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) at a fundamental level, according to a study published in eBiomedicine, part of The Lancet Discovery Science.

In the aftermath of COVID-19, a significant number of patients develop a fibrotic lung disease, for which insights into pathogenesis, disease models, or treatment options are lacking, according to researchers Dr. Sinha and colleagues. This long-haul form of the disease culminates in a fibrotic type of interstitial lung disease (ILD). While the actual prevalence of post–COVID-19 ILD (PCLD) is still emerging, early analysis indicates that more than a third of COVID-19 survivors develop fibrotic abnormalities, according to the authors.

Previous research has shown that one of the important determinants for PCLD is the duration of disease. Among patients who developed fibrosis, approximately 4% of patients had a disease duration of less than 1 week; approximately 24% had a disease duration between 1 and 3 weeks; and around 61% had a disease duration longer than 3 weeks, the authors stated.

The lung transcriptomic datasets compared in their study were associated with various lung conditions. The researchers used two viral pandemic signatures (ViP and sViP) and one COVID lung-derived signature. They found that the resemblances included that COVID-19 recapitulates the gene expression patterns (ViP and IPF signatures), cytokine storm (IL15-centric), and the AT2 cytopathic changes, for example, injury, DNA damage, arrest in a transient, damage-induced progenitor state, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

In laboratory experiments, Dr. Sinha and colleagues were able to induce these same immunocytopathic features in preclinical COVID-19 models (human adult lung organoid and hamster) and to reverse them in the hamster model with effective anti–CoV-2 therapeutics.

PPI-network analyses pinpointed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as one of the shared early triggers of both IPF and COVID-19, and immunohistochemistry studies validated the same in the lungs of deceased subjects with COVID-19 and the SARS-CoV-2–challenged hamster lungs. Additionally, lungs from transgenic mice, in which ER stress was induced specifically in the AT2 cells, faithfully recapitulated the host immune response and alveolar cytopathic changes that are induced by SARS-CoV-2.

stated corresponding author Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor in the departments of medicine and cellular and molecular medicine, University of California, San Diego. “If proven in prospective studies, this biomarker could indicate who is at greatest risk for progressive fibrosis and may require lung transplantation,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Ghosh stated further, “When it comes to therapeutics in COVID lung or IPF, we also found that shared fundamental pathogenic mechanisms present excellent opportunities for developing therapeutics that can arrest the fibrogenic drivers in both diseases. One clue that emerged is a specific cytokine that is at the heart of the smoldering inflammation which is invariably associated with fibrosis. That is interleukin 15 [IL-15] and its receptor.” Dr. Ghosh observed that there are two Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs for IPF. “None are very effective in arresting this invariably fatal disease. Hence, finding better options to treat IPF is an urgent and an unmet need.”

Preclinical testing of hypotheses, Dr. Ghosh said, is next on the path to clinical trials. “We have the advantage of using human lung organoids (mini-lungs grown using stem cells) in a dish, adding additional cells to the system (like fibroblasts and immune cells), infecting them with the virus, or subjecting them to the IL-15 cytokine and monitoring lung fibrosis progression in a dish. Anti–IL-15 therapy can then be initiated to observe reversal of the fibrogenic cascade.” Hamsters have also been shown to provide appropriate models for mimicking lung fibrosis, Dr. Ghosh said.

“The report by Sinha and colleagues describes the fascinating similarities between drivers of post-COVID lung disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” stated David Bowton, MD, professor emeritus, section on critical care, department of anesthesiology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., in an interview. He added that, “Central to the mechanisms of induction of fibrosis in both disorders appears to be endoplasmic reticulum stress in alveolar type II cells (AT2). ER stress induces the unfolded protein response (UPR) that halts protein translation and promotes the degradation of misfolded proteins. Prolonged UPR can reprogram the cell or trigger apoptosis pathways. ER stress in the lung has been reported in a variety of cell lines including AT2 in IPF, bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells in asthma and [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], and endothelial cells in pulmonary hypertension.”

Dr. Bowton commented further, including a caution, “Sinha and colleagues suggest that the identification of these gene signatures and mechanisms will be a fruitful avenue for developing effective therapeutics for IPF and other fibrotic lung diseases. I am hopeful that these data may offer clues that expedite this process. However, the redundancy of triggers for effector pathways in biologic systems argues that, even if successful, this will be [a] long and fraught process.”

The research study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants and funding from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program.

Dr. Sinha, Dr. Ghosh, and Dr. Bowton reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An AI-guided analysis of more than 1,000 human lung transcriptomic datasets found that COVID-19 resembles idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) at a fundamental level, according to a study published in eBiomedicine, part of The Lancet Discovery Science.

In the aftermath of COVID-19, a significant number of patients develop a fibrotic lung disease, for which insights into pathogenesis, disease models, or treatment options are lacking, according to researchers Dr. Sinha and colleagues. This long-haul form of the disease culminates in a fibrotic type of interstitial lung disease (ILD). While the actual prevalence of post–COVID-19 ILD (PCLD) is still emerging, early analysis indicates that more than a third of COVID-19 survivors develop fibrotic abnormalities, according to the authors.

Previous research has shown that one of the important determinants for PCLD is the duration of disease. Among patients who developed fibrosis, approximately 4% of patients had a disease duration of less than 1 week; approximately 24% had a disease duration between 1 and 3 weeks; and around 61% had a disease duration longer than 3 weeks, the authors stated.

The lung transcriptomic datasets compared in their study were associated with various lung conditions. The researchers used two viral pandemic signatures (ViP and sViP) and one COVID lung-derived signature. They found that the resemblances included that COVID-19 recapitulates the gene expression patterns (ViP and IPF signatures), cytokine storm (IL15-centric), and the AT2 cytopathic changes, for example, injury, DNA damage, arrest in a transient, damage-induced progenitor state, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

In laboratory experiments, Dr. Sinha and colleagues were able to induce these same immunocytopathic features in preclinical COVID-19 models (human adult lung organoid and hamster) and to reverse them in the hamster model with effective anti–CoV-2 therapeutics.

PPI-network analyses pinpointed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as one of the shared early triggers of both IPF and COVID-19, and immunohistochemistry studies validated the same in the lungs of deceased subjects with COVID-19 and the SARS-CoV-2–challenged hamster lungs. Additionally, lungs from transgenic mice, in which ER stress was induced specifically in the AT2 cells, faithfully recapitulated the host immune response and alveolar cytopathic changes that are induced by SARS-CoV-2.

stated corresponding author Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor in the departments of medicine and cellular and molecular medicine, University of California, San Diego. “If proven in prospective studies, this biomarker could indicate who is at greatest risk for progressive fibrosis and may require lung transplantation,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Ghosh stated further, “When it comes to therapeutics in COVID lung or IPF, we also found that shared fundamental pathogenic mechanisms present excellent opportunities for developing therapeutics that can arrest the fibrogenic drivers in both diseases. One clue that emerged is a specific cytokine that is at the heart of the smoldering inflammation which is invariably associated with fibrosis. That is interleukin 15 [IL-15] and its receptor.” Dr. Ghosh observed that there are two Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs for IPF. “None are very effective in arresting this invariably fatal disease. Hence, finding better options to treat IPF is an urgent and an unmet need.”

Preclinical testing of hypotheses, Dr. Ghosh said, is next on the path to clinical trials. “We have the advantage of using human lung organoids (mini-lungs grown using stem cells) in a dish, adding additional cells to the system (like fibroblasts and immune cells), infecting them with the virus, or subjecting them to the IL-15 cytokine and monitoring lung fibrosis progression in a dish. Anti–IL-15 therapy can then be initiated to observe reversal of the fibrogenic cascade.” Hamsters have also been shown to provide appropriate models for mimicking lung fibrosis, Dr. Ghosh said.

“The report by Sinha and colleagues describes the fascinating similarities between drivers of post-COVID lung disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” stated David Bowton, MD, professor emeritus, section on critical care, department of anesthesiology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., in an interview. He added that, “Central to the mechanisms of induction of fibrosis in both disorders appears to be endoplasmic reticulum stress in alveolar type II cells (AT2). ER stress induces the unfolded protein response (UPR) that halts protein translation and promotes the degradation of misfolded proteins. Prolonged UPR can reprogram the cell or trigger apoptosis pathways. ER stress in the lung has been reported in a variety of cell lines including AT2 in IPF, bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells in asthma and [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], and endothelial cells in pulmonary hypertension.”

Dr. Bowton commented further, including a caution, “Sinha and colleagues suggest that the identification of these gene signatures and mechanisms will be a fruitful avenue for developing effective therapeutics for IPF and other fibrotic lung diseases. I am hopeful that these data may offer clues that expedite this process. However, the redundancy of triggers for effector pathways in biologic systems argues that, even if successful, this will be [a] long and fraught process.”

The research study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants and funding from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program.

Dr. Sinha, Dr. Ghosh, and Dr. Bowton reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An AI-guided analysis of more than 1,000 human lung transcriptomic datasets found that COVID-19 resembles idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) at a fundamental level, according to a study published in eBiomedicine, part of The Lancet Discovery Science.

In the aftermath of COVID-19, a significant number of patients develop a fibrotic lung disease, for which insights into pathogenesis, disease models, or treatment options are lacking, according to researchers Dr. Sinha and colleagues. This long-haul form of the disease culminates in a fibrotic type of interstitial lung disease (ILD). While the actual prevalence of post–COVID-19 ILD (PCLD) is still emerging, early analysis indicates that more than a third of COVID-19 survivors develop fibrotic abnormalities, according to the authors.

Previous research has shown that one of the important determinants for PCLD is the duration of disease. Among patients who developed fibrosis, approximately 4% of patients had a disease duration of less than 1 week; approximately 24% had a disease duration between 1 and 3 weeks; and around 61% had a disease duration longer than 3 weeks, the authors stated.

The lung transcriptomic datasets compared in their study were associated with various lung conditions. The researchers used two viral pandemic signatures (ViP and sViP) and one COVID lung-derived signature. They found that the resemblances included that COVID-19 recapitulates the gene expression patterns (ViP and IPF signatures), cytokine storm (IL15-centric), and the AT2 cytopathic changes, for example, injury, DNA damage, arrest in a transient, damage-induced progenitor state, and senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

In laboratory experiments, Dr. Sinha and colleagues were able to induce these same immunocytopathic features in preclinical COVID-19 models (human adult lung organoid and hamster) and to reverse them in the hamster model with effective anti–CoV-2 therapeutics.

PPI-network analyses pinpointed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress as one of the shared early triggers of both IPF and COVID-19, and immunohistochemistry studies validated the same in the lungs of deceased subjects with COVID-19 and the SARS-CoV-2–challenged hamster lungs. Additionally, lungs from transgenic mice, in which ER stress was induced specifically in the AT2 cells, faithfully recapitulated the host immune response and alveolar cytopathic changes that are induced by SARS-CoV-2.

stated corresponding author Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor in the departments of medicine and cellular and molecular medicine, University of California, San Diego. “If proven in prospective studies, this biomarker could indicate who is at greatest risk for progressive fibrosis and may require lung transplantation,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Ghosh stated further, “When it comes to therapeutics in COVID lung or IPF, we also found that shared fundamental pathogenic mechanisms present excellent opportunities for developing therapeutics that can arrest the fibrogenic drivers in both diseases. One clue that emerged is a specific cytokine that is at the heart of the smoldering inflammation which is invariably associated with fibrosis. That is interleukin 15 [IL-15] and its receptor.” Dr. Ghosh observed that there are two Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs for IPF. “None are very effective in arresting this invariably fatal disease. Hence, finding better options to treat IPF is an urgent and an unmet need.”

Preclinical testing of hypotheses, Dr. Ghosh said, is next on the path to clinical trials. “We have the advantage of using human lung organoids (mini-lungs grown using stem cells) in a dish, adding additional cells to the system (like fibroblasts and immune cells), infecting them with the virus, or subjecting them to the IL-15 cytokine and monitoring lung fibrosis progression in a dish. Anti–IL-15 therapy can then be initiated to observe reversal of the fibrogenic cascade.” Hamsters have also been shown to provide appropriate models for mimicking lung fibrosis, Dr. Ghosh said.

“The report by Sinha and colleagues describes the fascinating similarities between drivers of post-COVID lung disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” stated David Bowton, MD, professor emeritus, section on critical care, department of anesthesiology, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., in an interview. He added that, “Central to the mechanisms of induction of fibrosis in both disorders appears to be endoplasmic reticulum stress in alveolar type II cells (AT2). ER stress induces the unfolded protein response (UPR) that halts protein translation and promotes the degradation of misfolded proteins. Prolonged UPR can reprogram the cell or trigger apoptosis pathways. ER stress in the lung has been reported in a variety of cell lines including AT2 in IPF, bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells in asthma and [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], and endothelial cells in pulmonary hypertension.”

Dr. Bowton commented further, including a caution, “Sinha and colleagues suggest that the identification of these gene signatures and mechanisms will be a fruitful avenue for developing effective therapeutics for IPF and other fibrotic lung diseases. I am hopeful that these data may offer clues that expedite this process. However, the redundancy of triggers for effector pathways in biologic systems argues that, even if successful, this will be [a] long and fraught process.”

The research study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants and funding from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program.

Dr. Sinha, Dr. Ghosh, and Dr. Bowton reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM eBIOMEDICINE

Medical assistants identify strategies and barriers to clinic efficiency

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Efficiency and competing priorities

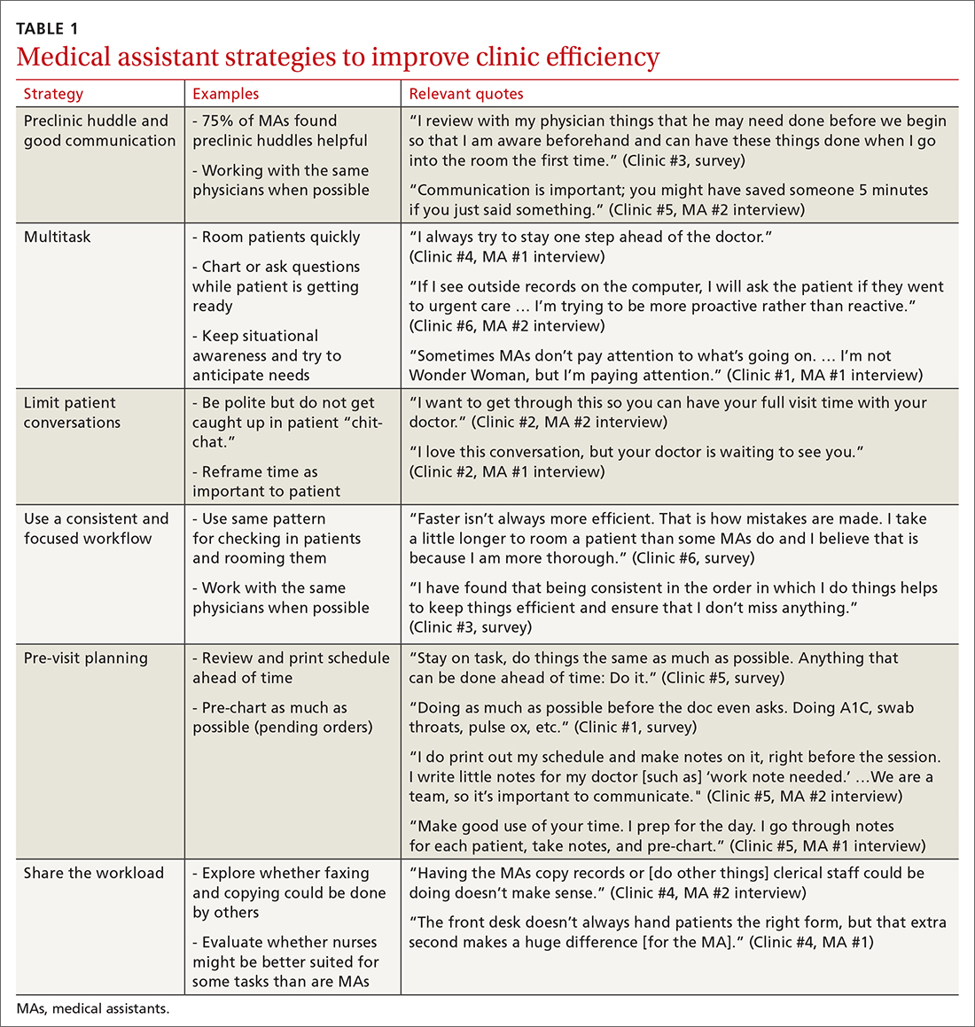

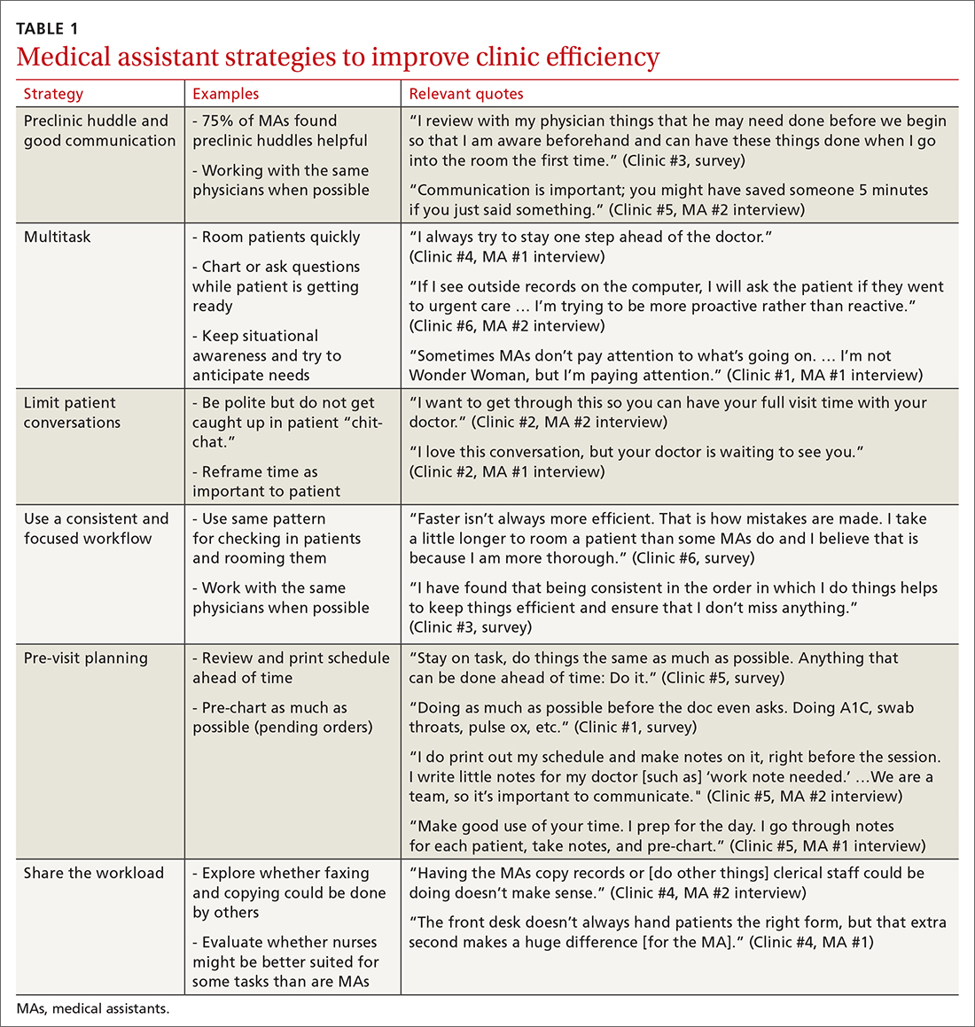

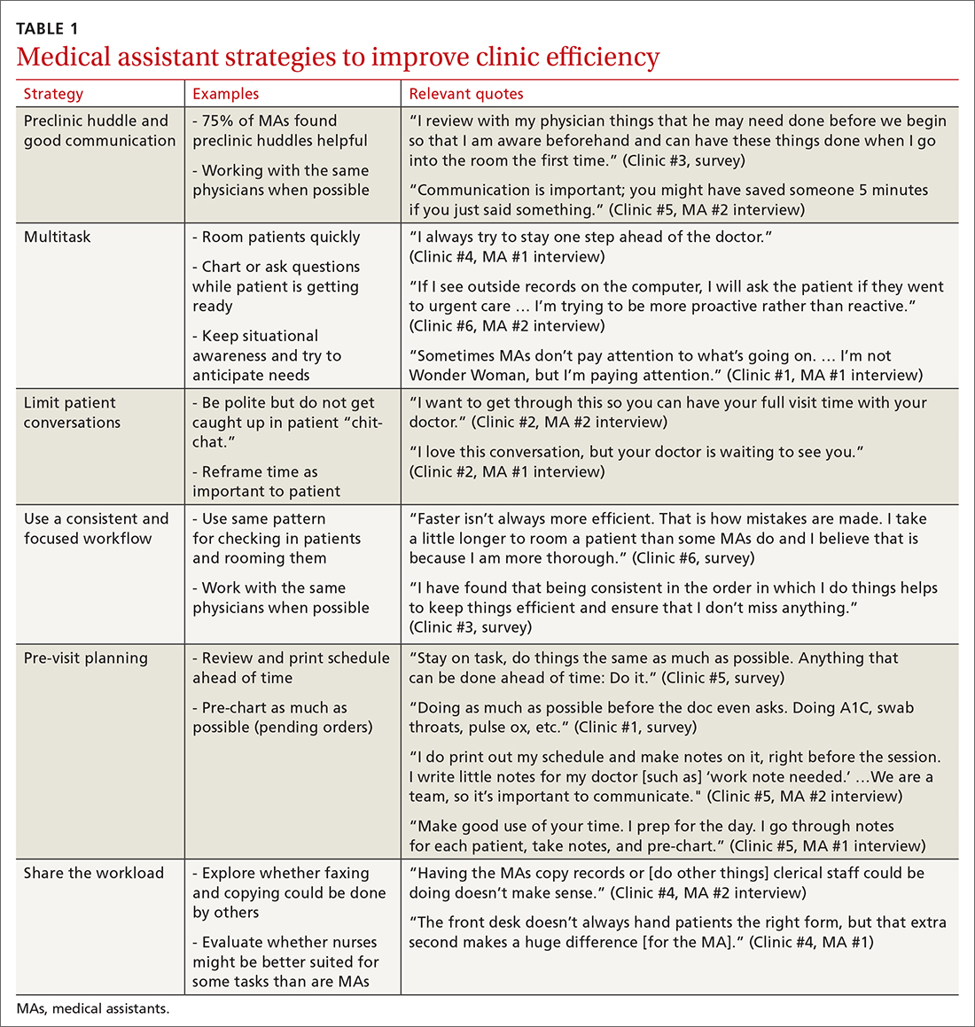

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

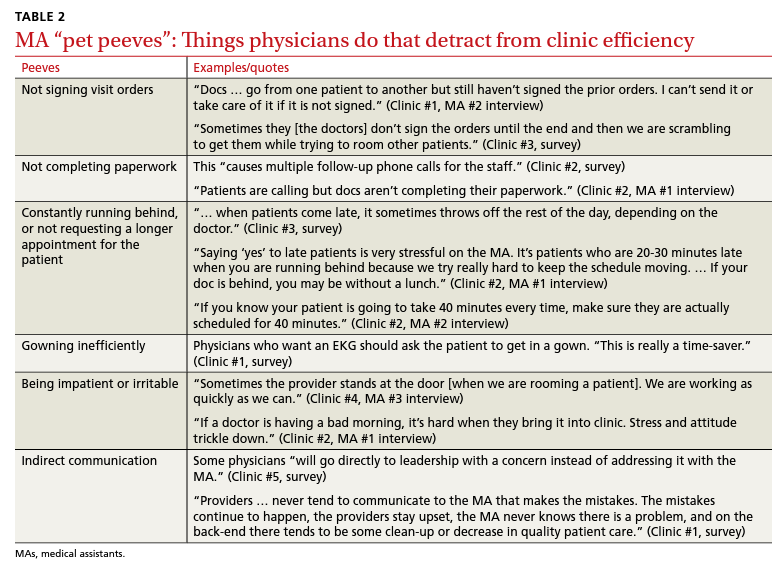

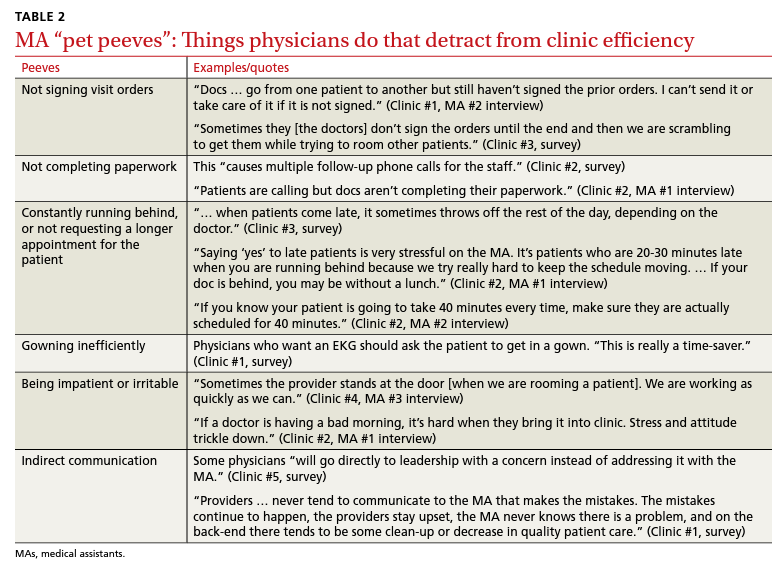

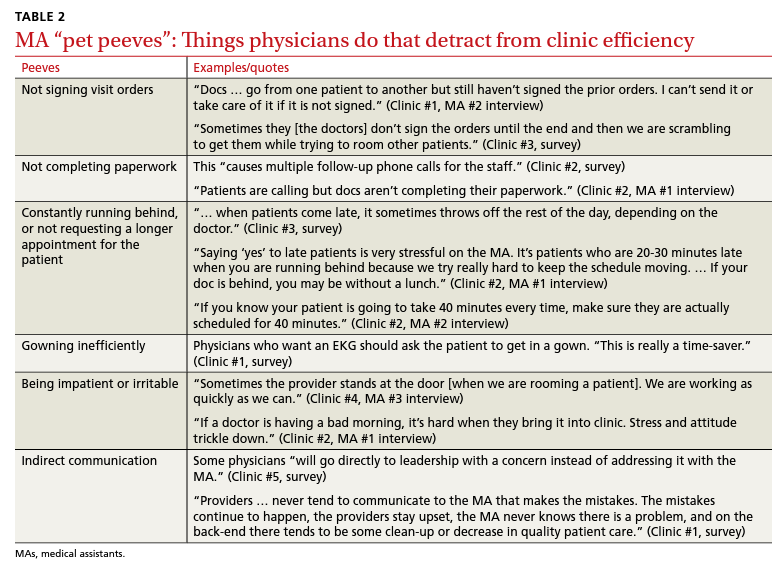

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Continue to: Clinic environment...

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“[Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male- dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries. 19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs. 8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; ktgold@umich.edu

- Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):383-406.

- Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:226-235.

- Atkins B. The outlook for medical assisting in 2016 and beyond. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.medicalassistantdegrees.net/ articles/medical-assisting-trends/

- Unqualified medical “assistants.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1897;23:163-164.

- Ameritech College of Healthcare. The origins of the AAMA. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.ameritech.edu/blog/medicalassisting-history/

- Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:368-377.

- Harper PG, Van Riper K, Ramer T, et al. Team-based care: an expanded medical assistant role—enhanced rooming and visit assistance. J Interprof Care. 2018:1-7.

- Sheridan B, Chien AT, Peters AS, et al. Team-based primary care: the medical assistant perspective. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43:115-125.

- Tache S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manag. 2010;24:288-305.

- STROBE checklist for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.strobe-statement.org/ fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_ combined.pdf

- Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:181-191.

- Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Bolon SK, et al. Patterns of relating between physicians and medical assistants in small family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:150-157.

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92:415-422.

- Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:167-173.

- Mohr DC, Young GJ, Meterko M, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care team members and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:18-25.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ oes/current/oes319092.htm

- Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning medical assistants for a greater role in the era of health reform. Acad Med. 2015;90:1347-1352.

- Mandel H. The role of occupational attributes in gender earnings inequality, 1970-2010. Soc Sci Res. 2016;55:122-138.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: medical assistants. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.bls.gov/ooh/ healthcare/medical-assistants.htm

- Skillman SM, Dahal A, Frogner BK, et al. Frontline workers’ career pathways: a detailed look at Washington state’s medical assistant workforce. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718812950.

- Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39:341-352.

- Dubois CA, Bentein K, Ben Mansour JB, et al. Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2014;11: 187-201.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264.

- O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, et al. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:183-192.

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Efficiency and competing priorities

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Continue to: Clinic environment...

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“[Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male- dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries. 19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs. 8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; ktgold@umich.edu

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.