User login

Digital algorithm better predicts risk for postpartum hemorrhage

A digital algorithm using 24 patient characteristics identifies far more women who are likely to develop a postpartum hemorrhage than currently used tools to predict the risk for bleeding after delivery, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

About 1 in 10 of the roughly 700 pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are caused by postpartum hemorrhage, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These deaths disproportionately occur among Black women, for whom studies show the risk of dying from a postpartum hemorrhage is fivefold greater than that of White women.

“Postpartum hemorrhage is a preventable medical emergency but remains the leading cause of maternal mortality globally,” the study’s senior author Li Li, MD, senior vice president of clinical informatics at Sema4, a company that uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to develop data-based clinical tools, told this news organization. “Early intervention is critical for reducing postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality.”

Porous predictors

Existing tools for risk prediction are not particularly effective, Dr. Li said. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Safe Motherhood Initiative offers checklists of clinical characteristics to classify women as low, medium, or high risk. However, 40% of the women classified as low risk based on this type of tool experience a hemorrhage.

ACOG also recommends quantifying blood loss during delivery or immediately after to identify women who are hemorrhaging, because imprecise estimates from clinicians may delay urgently needed care. Yet many hospitals have not implemented methods for measuring bleeding, said Dr. Li, who also is an assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

To develop a more precise way of identifying women at risk, Dr. Li and colleagues turned to artificial intelligence technology to create a “digital phenotype” based on approximately 72,000 births in the Mount Sinai Health System.

The digital tool retrospectively identified about 6,600 cases of postpartum hemorrhage, about 3.8 times the roughly 1,700 cases that would have been predicted based on methods that estimate blood loss. A blinded physician review of a subset of 45 patient charts – including 26 patients who experienced a hemorrhage, 11 who didn’t, and 6 with unclear outcomes – found that the digital approach was 89% percent accurate at identifying cases, whereas blood loss–based methods were accurate 67% of the time.

Several of the 24 characteristics included in the model appear in other risk predictors, including whether a woman has had a previous cesarean delivery or prior postdelivery bleeding and whether she has anemia or related blood disorders. Among the rest were risk factors that have been identified in the literature, including maternal blood pressure, time from admission to delivery, and average pulse during hospitalization. Five more features were new: red blood cell count and distribution width, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, absolute neutrophil count, and white blood cell count.

“These [new] values are easily obtainable from standard blood draws in the hospital but are not currently used in clinical practice to estimate postpartum hemorrhage risk,” Dr. Li said.

In a related retrospective study, Dr. Li and her colleagues used the new tool to classify women into high, low, or medium risk categories. They found that 28% of the women the algorithm classified as high risk experienced a postpartum hemorrhage compared with 15% to 19% of the women classified as high risk by standard predictive tools. They also identified potential “inflection points” where changes in vital signs may suggest a substantial increase in risk. For example, women whose median blood pressure during labor and delivery was above 132 mm Hg had an 11% average increase in their risk for bleeding.

By more precisely identifying women at risk, the new method “could be used to pre-emptively allocate resources that can ultimately reduce postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Li said. Sema4 is launching a prospective clinical trial to further assess the algorithm, she added.

Finding the continuum of risk

Holly Ende, MD, an obstetric anesthesiologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said approaches that leverage electronic health records to identify women at risk for hemorrhage have many advantages over currently used tools.

“Machine learning models or statistical models are able to take into account many more risk factors and weigh each of those risk factors based on how much they contribute to risk,” Dr. Ende, who was not involved in the new studies, told this news organization. “We can stratify women more on a continuum.”

But digital approaches have potential downsides.

“Machine learning algorithms can be developed in such a way that perpetuates racial bias, and it’s important to be aware of potential biases in coded algorithms,” Dr. Li said. To help reduce such bias, they used a database that included a racially and ethnically diverse patient population, but she acknowledged that additional research is needed.

Dr. Ende, the coauthor of a commentary in Obstetrics & Gynecology on risk assessment for postpartum hemorrhage, said algorithm developers must be sensitive to pre-existing disparities in health care that may affect the data they use to build the software.

She pointed to uterine atony – a known risk factor for hemorrhage – as an example. In her own research, she and her colleagues identified women with atony by searching their medical records for medications used to treat the condition. But when they ran their model, Black women were less likely to develop uterine atony, which the team knew wasn’t true in the real world. They traced the problem to an existing disparity in obstetric care: Black women with uterine atony were less likely than women of other races to receive medications for the condition.

“People need to be cognizant as they are developing these types of prediction models and be extremely careful to avoid perpetuating any disparities in care,” Dr. Ende cautioned. On the other hand, if carefully developed, these tools might also help reduce disparities in health care by standardizing risk stratification and clinical practices, she said.

In addition to independent validation of data-based risk prediction tools, Dr. Ende said ensuring that clinicians are properly trained to use these tools is crucial.

“Implementation may be the biggest limitation,” she said.

Dr. Ende and Dr. Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A digital algorithm using 24 patient characteristics identifies far more women who are likely to develop a postpartum hemorrhage than currently used tools to predict the risk for bleeding after delivery, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

About 1 in 10 of the roughly 700 pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are caused by postpartum hemorrhage, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These deaths disproportionately occur among Black women, for whom studies show the risk of dying from a postpartum hemorrhage is fivefold greater than that of White women.

“Postpartum hemorrhage is a preventable medical emergency but remains the leading cause of maternal mortality globally,” the study’s senior author Li Li, MD, senior vice president of clinical informatics at Sema4, a company that uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to develop data-based clinical tools, told this news organization. “Early intervention is critical for reducing postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality.”

Porous predictors

Existing tools for risk prediction are not particularly effective, Dr. Li said. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Safe Motherhood Initiative offers checklists of clinical characteristics to classify women as low, medium, or high risk. However, 40% of the women classified as low risk based on this type of tool experience a hemorrhage.

ACOG also recommends quantifying blood loss during delivery or immediately after to identify women who are hemorrhaging, because imprecise estimates from clinicians may delay urgently needed care. Yet many hospitals have not implemented methods for measuring bleeding, said Dr. Li, who also is an assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

To develop a more precise way of identifying women at risk, Dr. Li and colleagues turned to artificial intelligence technology to create a “digital phenotype” based on approximately 72,000 births in the Mount Sinai Health System.

The digital tool retrospectively identified about 6,600 cases of postpartum hemorrhage, about 3.8 times the roughly 1,700 cases that would have been predicted based on methods that estimate blood loss. A blinded physician review of a subset of 45 patient charts – including 26 patients who experienced a hemorrhage, 11 who didn’t, and 6 with unclear outcomes – found that the digital approach was 89% percent accurate at identifying cases, whereas blood loss–based methods were accurate 67% of the time.

Several of the 24 characteristics included in the model appear in other risk predictors, including whether a woman has had a previous cesarean delivery or prior postdelivery bleeding and whether she has anemia or related blood disorders. Among the rest were risk factors that have been identified in the literature, including maternal blood pressure, time from admission to delivery, and average pulse during hospitalization. Five more features were new: red blood cell count and distribution width, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, absolute neutrophil count, and white blood cell count.

“These [new] values are easily obtainable from standard blood draws in the hospital but are not currently used in clinical practice to estimate postpartum hemorrhage risk,” Dr. Li said.

In a related retrospective study, Dr. Li and her colleagues used the new tool to classify women into high, low, or medium risk categories. They found that 28% of the women the algorithm classified as high risk experienced a postpartum hemorrhage compared with 15% to 19% of the women classified as high risk by standard predictive tools. They also identified potential “inflection points” where changes in vital signs may suggest a substantial increase in risk. For example, women whose median blood pressure during labor and delivery was above 132 mm Hg had an 11% average increase in their risk for bleeding.

By more precisely identifying women at risk, the new method “could be used to pre-emptively allocate resources that can ultimately reduce postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Li said. Sema4 is launching a prospective clinical trial to further assess the algorithm, she added.

Finding the continuum of risk

Holly Ende, MD, an obstetric anesthesiologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said approaches that leverage electronic health records to identify women at risk for hemorrhage have many advantages over currently used tools.

“Machine learning models or statistical models are able to take into account many more risk factors and weigh each of those risk factors based on how much they contribute to risk,” Dr. Ende, who was not involved in the new studies, told this news organization. “We can stratify women more on a continuum.”

But digital approaches have potential downsides.

“Machine learning algorithms can be developed in such a way that perpetuates racial bias, and it’s important to be aware of potential biases in coded algorithms,” Dr. Li said. To help reduce such bias, they used a database that included a racially and ethnically diverse patient population, but she acknowledged that additional research is needed.

Dr. Ende, the coauthor of a commentary in Obstetrics & Gynecology on risk assessment for postpartum hemorrhage, said algorithm developers must be sensitive to pre-existing disparities in health care that may affect the data they use to build the software.

She pointed to uterine atony – a known risk factor for hemorrhage – as an example. In her own research, she and her colleagues identified women with atony by searching their medical records for medications used to treat the condition. But when they ran their model, Black women were less likely to develop uterine atony, which the team knew wasn’t true in the real world. They traced the problem to an existing disparity in obstetric care: Black women with uterine atony were less likely than women of other races to receive medications for the condition.

“People need to be cognizant as they are developing these types of prediction models and be extremely careful to avoid perpetuating any disparities in care,” Dr. Ende cautioned. On the other hand, if carefully developed, these tools might also help reduce disparities in health care by standardizing risk stratification and clinical practices, she said.

In addition to independent validation of data-based risk prediction tools, Dr. Ende said ensuring that clinicians are properly trained to use these tools is crucial.

“Implementation may be the biggest limitation,” she said.

Dr. Ende and Dr. Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A digital algorithm using 24 patient characteristics identifies far more women who are likely to develop a postpartum hemorrhage than currently used tools to predict the risk for bleeding after delivery, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

About 1 in 10 of the roughly 700 pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are caused by postpartum hemorrhage, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These deaths disproportionately occur among Black women, for whom studies show the risk of dying from a postpartum hemorrhage is fivefold greater than that of White women.

“Postpartum hemorrhage is a preventable medical emergency but remains the leading cause of maternal mortality globally,” the study’s senior author Li Li, MD, senior vice president of clinical informatics at Sema4, a company that uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to develop data-based clinical tools, told this news organization. “Early intervention is critical for reducing postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality.”

Porous predictors

Existing tools for risk prediction are not particularly effective, Dr. Li said. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Safe Motherhood Initiative offers checklists of clinical characteristics to classify women as low, medium, or high risk. However, 40% of the women classified as low risk based on this type of tool experience a hemorrhage.

ACOG also recommends quantifying blood loss during delivery or immediately after to identify women who are hemorrhaging, because imprecise estimates from clinicians may delay urgently needed care. Yet many hospitals have not implemented methods for measuring bleeding, said Dr. Li, who also is an assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

To develop a more precise way of identifying women at risk, Dr. Li and colleagues turned to artificial intelligence technology to create a “digital phenotype” based on approximately 72,000 births in the Mount Sinai Health System.

The digital tool retrospectively identified about 6,600 cases of postpartum hemorrhage, about 3.8 times the roughly 1,700 cases that would have been predicted based on methods that estimate blood loss. A blinded physician review of a subset of 45 patient charts – including 26 patients who experienced a hemorrhage, 11 who didn’t, and 6 with unclear outcomes – found that the digital approach was 89% percent accurate at identifying cases, whereas blood loss–based methods were accurate 67% of the time.

Several of the 24 characteristics included in the model appear in other risk predictors, including whether a woman has had a previous cesarean delivery or prior postdelivery bleeding and whether she has anemia or related blood disorders. Among the rest were risk factors that have been identified in the literature, including maternal blood pressure, time from admission to delivery, and average pulse during hospitalization. Five more features were new: red blood cell count and distribution width, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, absolute neutrophil count, and white blood cell count.

“These [new] values are easily obtainable from standard blood draws in the hospital but are not currently used in clinical practice to estimate postpartum hemorrhage risk,” Dr. Li said.

In a related retrospective study, Dr. Li and her colleagues used the new tool to classify women into high, low, or medium risk categories. They found that 28% of the women the algorithm classified as high risk experienced a postpartum hemorrhage compared with 15% to 19% of the women classified as high risk by standard predictive tools. They also identified potential “inflection points” where changes in vital signs may suggest a substantial increase in risk. For example, women whose median blood pressure during labor and delivery was above 132 mm Hg had an 11% average increase in their risk for bleeding.

By more precisely identifying women at risk, the new method “could be used to pre-emptively allocate resources that can ultimately reduce postpartum hemorrhage morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Li said. Sema4 is launching a prospective clinical trial to further assess the algorithm, she added.

Finding the continuum of risk

Holly Ende, MD, an obstetric anesthesiologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said approaches that leverage electronic health records to identify women at risk for hemorrhage have many advantages over currently used tools.

“Machine learning models or statistical models are able to take into account many more risk factors and weigh each of those risk factors based on how much they contribute to risk,” Dr. Ende, who was not involved in the new studies, told this news organization. “We can stratify women more on a continuum.”

But digital approaches have potential downsides.

“Machine learning algorithms can be developed in such a way that perpetuates racial bias, and it’s important to be aware of potential biases in coded algorithms,” Dr. Li said. To help reduce such bias, they used a database that included a racially and ethnically diverse patient population, but she acknowledged that additional research is needed.

Dr. Ende, the coauthor of a commentary in Obstetrics & Gynecology on risk assessment for postpartum hemorrhage, said algorithm developers must be sensitive to pre-existing disparities in health care that may affect the data they use to build the software.

She pointed to uterine atony – a known risk factor for hemorrhage – as an example. In her own research, she and her colleagues identified women with atony by searching their medical records for medications used to treat the condition. But when they ran their model, Black women were less likely to develop uterine atony, which the team knew wasn’t true in the real world. They traced the problem to an existing disparity in obstetric care: Black women with uterine atony were less likely than women of other races to receive medications for the condition.

“People need to be cognizant as they are developing these types of prediction models and be extremely careful to avoid perpetuating any disparities in care,” Dr. Ende cautioned. On the other hand, if carefully developed, these tools might also help reduce disparities in health care by standardizing risk stratification and clinical practices, she said.

In addition to independent validation of data-based risk prediction tools, Dr. Ende said ensuring that clinicians are properly trained to use these tools is crucial.

“Implementation may be the biggest limitation,” she said.

Dr. Ende and Dr. Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This doc still supports NP/PA-led care ... with caveats

Two years ago, I argued that independent care from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) would not have ill effects on health outcomes. To the surprise of no one, NPs and PAs embraced the argument; physicians clobbered it.

My case had three pegs: One was that medicine isn’t rocket science and clinicians control a lot less than we think we do. The second peg was that technology levels the playing field of clinical care. High-sensitivity troponin assays, for instance, make missing MI a lot less likely. The third peg was empirical: Studies have found little difference in MD versus non–MD-led care. Looking back, I now see empiricism as the weakest part of the argument because the studies had so many limitations.

I update this viewpoint now because health care is increasingly delivered by NPs and PAs. And there are two concerning trends regarding NP education and experience. First is that nurses are turning to advanced practitioner training earlier in their careers – without gathering much bedside experience. And these training programs are increasingly likely to be online, with minimal hands-on clinical tutoring.

Education and experience pop in my head often. Not every day, but many days I think back to my lucky 7 years in Indiana learning under the supervision of master clinicians – at a time when trainees were allowed the leeway to make decisions ... and mistakes. Then, when I joined private practice, I continued to learn from experienced practitioners.

It would be foolish to argue that training and experience aren’t important.

But here’s the thing:

I will make three points: First, I will bolster two of my old arguments as to why we shouldn’t be worried about non-MD clinicians, then I will propose some ideas to increase confidence in NP and PA care.

Health care does not equal health

On the matter of how much clinicians affect outcomes, a recently published randomized controlled trial performed in India found that subsidizing insurance care led to increased utilization of hospital services but had no significant effect on health outcomes. This follows the RAND and Oregon Health Insurance studies in the United States, which largely reported similar results.

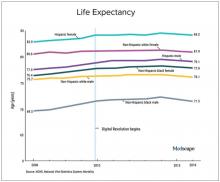

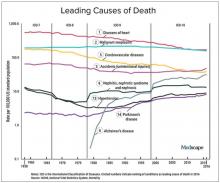

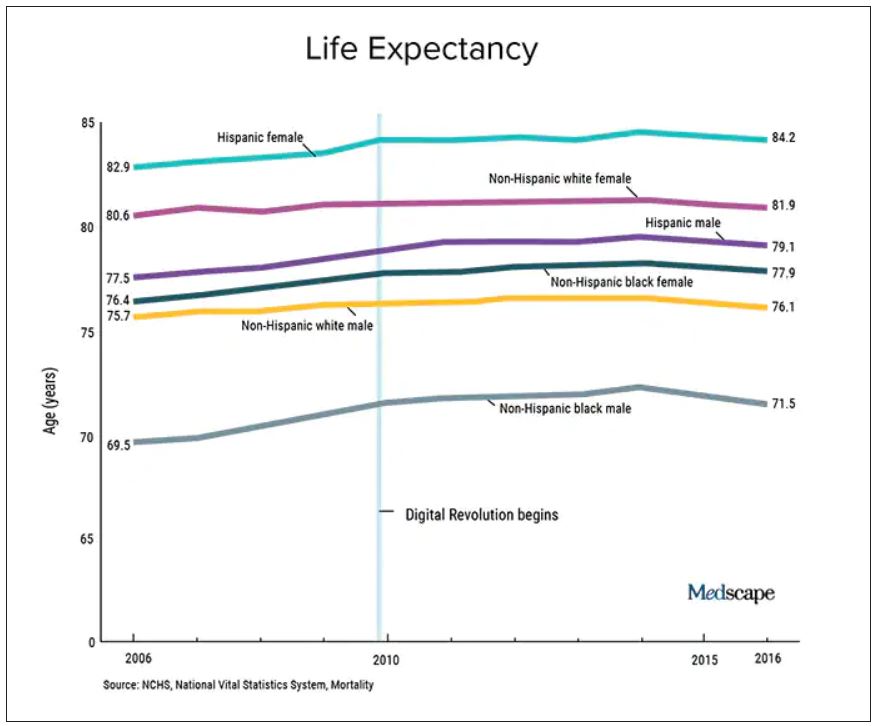

We should also not dismiss the fact that – despite the massive technology gains over the past half-century in digital health and artificial intelligence and increased use of quality measures, new drugs and procedures, and mega-medical centers – the average lifespan of Americans is flat to declining (in most ethnic and racial groups). Worse than no gains in longevity, perhaps, is that death from diseases like dementia and Parkinson’s disease are on the rise.

A neutral Martian would look down and wonder why all this health care hasn’t translated to longer and better lives. The causes of this paradox remain speculative, and are for another column, but the point remains that – on average – more health care is clearly not delivering more health. And if that is true, one may deduce that much of U.S. health care is marginal when it comes to affecting major outcomes.

It’s about the delta

Logos trumps pathos. Sure, my physician colleagues can tell scary anecdotes of bad outcomes caused by an inexperienced NP or PA. I would counter that by saying I have sat on our hospital’s peer review committee for 2 decades, including the era before NPs or PAs were practicing, and I have plenty of stories of physician errors. These include, of course, my own errors.

Logos: We must consider the difference between non–MD-led care and MD-led care.

My arguments from 2020 remain relevant today. Most medical problems are not engineering puzzles. Many, perhaps most, patients fall into an easy protocol – say, chest pain, dyspnea, or atrial fibrillation. With basic training, a motivated serious person quickly gains skill in recognizing and treating everyday problems.

And just 2 years on, technology further levels the playing field. Consider radiology in 2022 – it’s easy to take for granted the speed of the CT scan, the fidelity of the MRI, and the easy access to both in the U.S. hospital system. Less experienced clinicians have never had more tools to assist with diagnostics and therapeutics.

The expansion of team-based care has also mitigated the effects of inexperience. It took Americans longer than Canadians to figure out how helpful pharmacists could be. Pharmacists in my hospital now help us dose complicated medicines and protect us against prescribing errors.

Then there is the immediate access to online information. Gone are the days when you had to memorize long-QT syndromes. Book knowledge – that I spent years acquiring – now comes in seconds. The other day an NP corrected me. I asked, Are you sure? Boom, she took out her phone and showed me the evidence.

In sum, if it were even possible to measure the clinical competence of care from NP and PA versus physicians, there would be two bell-shaped curves with a tremendous amount of overlap. And that overlap would steadily increase as a given NP or PA gathered experience. (The NP in our electrophysiology division has more than 25 years’ experience in heart rhythm care, and it is common for colleagues to call her before one of us docs. Rightly so.)

Three basic proposals regarding NP and PA care

To ensure quality of care, I have three proposals.

It has always seemed strange to me that an NP or PA can flip from one field to another without a period of training. I can’t just change practice from electrophysiology to dermatology without doing a residency. But NPs and PAs can.

My first proposal would be that NPs and PAs spend a substantial period of training in a field before practice – a legit apprenticeship. The duration of this period is a matter of debate, but it ought to be standardized.

My second proposal is that, if physicians are required to pass certification exams, so should NPs. (PAs have an exam every 10 years.) The exam should be the same as (or very similar to) the physician exam, and it should be specific to their field of practice.

While I have argued (and still feel) that the American Board of Internal Medicine brand of certification is dubious, the fact remains that physicians must maintain proficiency in their field. Requiring NPs and PAs to do the same would help foster specialization. And while I can’t cite empirical evidence, specialization seems super-important. We have NPs at my hospital who have been in the same area for years, and they exude clinical competence.

Finally, I have come to believe that the best way for nearly any clinician to practice medicine is as part of a team. (The exception being primary care in rural areas where there are clinician shortages.)

On the matter of team care, I’ve practiced for a long time, but nearly every day I run situations by a colleague; often this person is an NP. The economist Friedrich Hayek proposed that dispersed knowledge always outpaces the wisdom of any individual. That notion pertains well to the increasing complexities and specialization of modern medical practice.

A person who commits to learning one area of medicine, enjoys helping people, asks often for help, and has the support of colleagues is set up to be a successful clinician – whether the letters after their name are APRN, PA, DO, or MD.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky. He did not report any relevant financial disclosures. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two years ago, I argued that independent care from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) would not have ill effects on health outcomes. To the surprise of no one, NPs and PAs embraced the argument; physicians clobbered it.

My case had three pegs: One was that medicine isn’t rocket science and clinicians control a lot less than we think we do. The second peg was that technology levels the playing field of clinical care. High-sensitivity troponin assays, for instance, make missing MI a lot less likely. The third peg was empirical: Studies have found little difference in MD versus non–MD-led care. Looking back, I now see empiricism as the weakest part of the argument because the studies had so many limitations.

I update this viewpoint now because health care is increasingly delivered by NPs and PAs. And there are two concerning trends regarding NP education and experience. First is that nurses are turning to advanced practitioner training earlier in their careers – without gathering much bedside experience. And these training programs are increasingly likely to be online, with minimal hands-on clinical tutoring.

Education and experience pop in my head often. Not every day, but many days I think back to my lucky 7 years in Indiana learning under the supervision of master clinicians – at a time when trainees were allowed the leeway to make decisions ... and mistakes. Then, when I joined private practice, I continued to learn from experienced practitioners.

It would be foolish to argue that training and experience aren’t important.

But here’s the thing:

I will make three points: First, I will bolster two of my old arguments as to why we shouldn’t be worried about non-MD clinicians, then I will propose some ideas to increase confidence in NP and PA care.

Health care does not equal health

On the matter of how much clinicians affect outcomes, a recently published randomized controlled trial performed in India found that subsidizing insurance care led to increased utilization of hospital services but had no significant effect on health outcomes. This follows the RAND and Oregon Health Insurance studies in the United States, which largely reported similar results.

We should also not dismiss the fact that – despite the massive technology gains over the past half-century in digital health and artificial intelligence and increased use of quality measures, new drugs and procedures, and mega-medical centers – the average lifespan of Americans is flat to declining (in most ethnic and racial groups). Worse than no gains in longevity, perhaps, is that death from diseases like dementia and Parkinson’s disease are on the rise.

A neutral Martian would look down and wonder why all this health care hasn’t translated to longer and better lives. The causes of this paradox remain speculative, and are for another column, but the point remains that – on average – more health care is clearly not delivering more health. And if that is true, one may deduce that much of U.S. health care is marginal when it comes to affecting major outcomes.

It’s about the delta

Logos trumps pathos. Sure, my physician colleagues can tell scary anecdotes of bad outcomes caused by an inexperienced NP or PA. I would counter that by saying I have sat on our hospital’s peer review committee for 2 decades, including the era before NPs or PAs were practicing, and I have plenty of stories of physician errors. These include, of course, my own errors.

Logos: We must consider the difference between non–MD-led care and MD-led care.

My arguments from 2020 remain relevant today. Most medical problems are not engineering puzzles. Many, perhaps most, patients fall into an easy protocol – say, chest pain, dyspnea, or atrial fibrillation. With basic training, a motivated serious person quickly gains skill in recognizing and treating everyday problems.

And just 2 years on, technology further levels the playing field. Consider radiology in 2022 – it’s easy to take for granted the speed of the CT scan, the fidelity of the MRI, and the easy access to both in the U.S. hospital system. Less experienced clinicians have never had more tools to assist with diagnostics and therapeutics.

The expansion of team-based care has also mitigated the effects of inexperience. It took Americans longer than Canadians to figure out how helpful pharmacists could be. Pharmacists in my hospital now help us dose complicated medicines and protect us against prescribing errors.

Then there is the immediate access to online information. Gone are the days when you had to memorize long-QT syndromes. Book knowledge – that I spent years acquiring – now comes in seconds. The other day an NP corrected me. I asked, Are you sure? Boom, she took out her phone and showed me the evidence.

In sum, if it were even possible to measure the clinical competence of care from NP and PA versus physicians, there would be two bell-shaped curves with a tremendous amount of overlap. And that overlap would steadily increase as a given NP or PA gathered experience. (The NP in our electrophysiology division has more than 25 years’ experience in heart rhythm care, and it is common for colleagues to call her before one of us docs. Rightly so.)

Three basic proposals regarding NP and PA care

To ensure quality of care, I have three proposals.

It has always seemed strange to me that an NP or PA can flip from one field to another without a period of training. I can’t just change practice from electrophysiology to dermatology without doing a residency. But NPs and PAs can.

My first proposal would be that NPs and PAs spend a substantial period of training in a field before practice – a legit apprenticeship. The duration of this period is a matter of debate, but it ought to be standardized.

My second proposal is that, if physicians are required to pass certification exams, so should NPs. (PAs have an exam every 10 years.) The exam should be the same as (or very similar to) the physician exam, and it should be specific to their field of practice.

While I have argued (and still feel) that the American Board of Internal Medicine brand of certification is dubious, the fact remains that physicians must maintain proficiency in their field. Requiring NPs and PAs to do the same would help foster specialization. And while I can’t cite empirical evidence, specialization seems super-important. We have NPs at my hospital who have been in the same area for years, and they exude clinical competence.

Finally, I have come to believe that the best way for nearly any clinician to practice medicine is as part of a team. (The exception being primary care in rural areas where there are clinician shortages.)

On the matter of team care, I’ve practiced for a long time, but nearly every day I run situations by a colleague; often this person is an NP. The economist Friedrich Hayek proposed that dispersed knowledge always outpaces the wisdom of any individual. That notion pertains well to the increasing complexities and specialization of modern medical practice.

A person who commits to learning one area of medicine, enjoys helping people, asks often for help, and has the support of colleagues is set up to be a successful clinician – whether the letters after their name are APRN, PA, DO, or MD.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky. He did not report any relevant financial disclosures. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two years ago, I argued that independent care from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) would not have ill effects on health outcomes. To the surprise of no one, NPs and PAs embraced the argument; physicians clobbered it.

My case had three pegs: One was that medicine isn’t rocket science and clinicians control a lot less than we think we do. The second peg was that technology levels the playing field of clinical care. High-sensitivity troponin assays, for instance, make missing MI a lot less likely. The third peg was empirical: Studies have found little difference in MD versus non–MD-led care. Looking back, I now see empiricism as the weakest part of the argument because the studies had so many limitations.

I update this viewpoint now because health care is increasingly delivered by NPs and PAs. And there are two concerning trends regarding NP education and experience. First is that nurses are turning to advanced practitioner training earlier in their careers – without gathering much bedside experience. And these training programs are increasingly likely to be online, with minimal hands-on clinical tutoring.

Education and experience pop in my head often. Not every day, but many days I think back to my lucky 7 years in Indiana learning under the supervision of master clinicians – at a time when trainees were allowed the leeway to make decisions ... and mistakes. Then, when I joined private practice, I continued to learn from experienced practitioners.

It would be foolish to argue that training and experience aren’t important.

But here’s the thing:

I will make three points: First, I will bolster two of my old arguments as to why we shouldn’t be worried about non-MD clinicians, then I will propose some ideas to increase confidence in NP and PA care.

Health care does not equal health

On the matter of how much clinicians affect outcomes, a recently published randomized controlled trial performed in India found that subsidizing insurance care led to increased utilization of hospital services but had no significant effect on health outcomes. This follows the RAND and Oregon Health Insurance studies in the United States, which largely reported similar results.

We should also not dismiss the fact that – despite the massive technology gains over the past half-century in digital health and artificial intelligence and increased use of quality measures, new drugs and procedures, and mega-medical centers – the average lifespan of Americans is flat to declining (in most ethnic and racial groups). Worse than no gains in longevity, perhaps, is that death from diseases like dementia and Parkinson’s disease are on the rise.

A neutral Martian would look down and wonder why all this health care hasn’t translated to longer and better lives. The causes of this paradox remain speculative, and are for another column, but the point remains that – on average – more health care is clearly not delivering more health. And if that is true, one may deduce that much of U.S. health care is marginal when it comes to affecting major outcomes.

It’s about the delta

Logos trumps pathos. Sure, my physician colleagues can tell scary anecdotes of bad outcomes caused by an inexperienced NP or PA. I would counter that by saying I have sat on our hospital’s peer review committee for 2 decades, including the era before NPs or PAs were practicing, and I have plenty of stories of physician errors. These include, of course, my own errors.

Logos: We must consider the difference between non–MD-led care and MD-led care.

My arguments from 2020 remain relevant today. Most medical problems are not engineering puzzles. Many, perhaps most, patients fall into an easy protocol – say, chest pain, dyspnea, or atrial fibrillation. With basic training, a motivated serious person quickly gains skill in recognizing and treating everyday problems.

And just 2 years on, technology further levels the playing field. Consider radiology in 2022 – it’s easy to take for granted the speed of the CT scan, the fidelity of the MRI, and the easy access to both in the U.S. hospital system. Less experienced clinicians have never had more tools to assist with diagnostics and therapeutics.

The expansion of team-based care has also mitigated the effects of inexperience. It took Americans longer than Canadians to figure out how helpful pharmacists could be. Pharmacists in my hospital now help us dose complicated medicines and protect us against prescribing errors.

Then there is the immediate access to online information. Gone are the days when you had to memorize long-QT syndromes. Book knowledge – that I spent years acquiring – now comes in seconds. The other day an NP corrected me. I asked, Are you sure? Boom, she took out her phone and showed me the evidence.

In sum, if it were even possible to measure the clinical competence of care from NP and PA versus physicians, there would be two bell-shaped curves with a tremendous amount of overlap. And that overlap would steadily increase as a given NP or PA gathered experience. (The NP in our electrophysiology division has more than 25 years’ experience in heart rhythm care, and it is common for colleagues to call her before one of us docs. Rightly so.)

Three basic proposals regarding NP and PA care

To ensure quality of care, I have three proposals.

It has always seemed strange to me that an NP or PA can flip from one field to another without a period of training. I can’t just change practice from electrophysiology to dermatology without doing a residency. But NPs and PAs can.

My first proposal would be that NPs and PAs spend a substantial period of training in a field before practice – a legit apprenticeship. The duration of this period is a matter of debate, but it ought to be standardized.

My second proposal is that, if physicians are required to pass certification exams, so should NPs. (PAs have an exam every 10 years.) The exam should be the same as (or very similar to) the physician exam, and it should be specific to their field of practice.

While I have argued (and still feel) that the American Board of Internal Medicine brand of certification is dubious, the fact remains that physicians must maintain proficiency in their field. Requiring NPs and PAs to do the same would help foster specialization. And while I can’t cite empirical evidence, specialization seems super-important. We have NPs at my hospital who have been in the same area for years, and they exude clinical competence.

Finally, I have come to believe that the best way for nearly any clinician to practice medicine is as part of a team. (The exception being primary care in rural areas where there are clinician shortages.)

On the matter of team care, I’ve practiced for a long time, but nearly every day I run situations by a colleague; often this person is an NP. The economist Friedrich Hayek proposed that dispersed knowledge always outpaces the wisdom of any individual. That notion pertains well to the increasing complexities and specialization of modern medical practice.

A person who commits to learning one area of medicine, enjoys helping people, asks often for help, and has the support of colleagues is set up to be a successful clinician – whether the letters after their name are APRN, PA, DO, or MD.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky. He did not report any relevant financial disclosures. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Seven ways doctors could get better payment from insurers

, say experts in physician-payer contracts.

Many doctors sign long-term agreements and then forget about them, says Marcia Brauchler, president and founder of Physicians’ Ally, Littleton, Colorado, a health care consulting company. “The average doctor is trying to run a practice on 2010 rates because they haven’t touched their insurance contracts for 10 years,” she says.

Payers also make a lot of money by adopting dozens of unilateral policy and procedure changes every year that they know physicians are too busy to read. They are counting on the fact that few doctors will understand what the policy changes are and that even fewer will contest them, says Greg Brodek, JD, chair of the health law practice group and head of the managed care litigation practice at Duane Morris, who represents doctors in disputes with payers.

These experts say doctors can push back on one-sided payer contracts and negotiate changes. Mr. Brodek says some practices have more leverage than others to influence payers – if they are larger, in a specialty that the payer needs in its network, or located in a remote area where the payer has limited options.

Here are seven key areas to pay attention to:

1. Long-term contracts. Most doctors sign multiyear “evergreen” contracts that renew automatically every year. This allows insurers to continue to pay doctors the same rate for years.

To avoid this, doctors should negotiate new rates when their agreements renew or, if they prefer, ask that a cost-of-living adjustment be included in the multiyear contract that applies to subsequent years, says Ms. Brauchler.

2. Fee schedules. Payers will “whitewash” what they’re paying you by saying it’s 100% of the payer fee schedule. When it comes to Medicare, they may be paying you a lot less, says Ms. Brauchler.

“My biggest takeaway is to compare the CPT codes of the payer’s fee schedule against what Medicare allows. For example, for CPT code 99213, a 15-minute established office visit, if Medicare pays you $100 and Aetna pays you $75.00, you’re getting 75% of Medicare,” says Ms. Brauchler. To avoid this, doctors should ask that the contract state that reimbursement be made according to Medicare’s medical policies rather than the payer’s.

3. Audits. Commercial payers will claim they have a contractual right to conduct pre- and post-payment audits of physicians’ claims that can result in reduced payments. The contract only states that if doctors correctly submit claims, they will get paid, not that they will have to go through extra steps, which is a breach of their agreement, says Mr. Brodek.

In his experience, 90% of payers back down when asked to provide the contractual basis to conduct these audits. “Or, they take the position that it’s not in the contract but that they have a policy.”

4. Contract amendments versus policies and procedures. This is a huge area that needs to be clarified in contracts and monitored by providers throughout their relationships with payers. Contracts have three elements: the parties, the services provided, and the payment. Changing any one of those terms requires an amendment and advance written notice that has to be delivered to the other party in a certain way, such as by overnight delivery, says Mr. Brodek.

In addition, both parties have to sign that they agree to an amendment. “But, that’s too cumbersome and complicated for payers who have decided to adopt policies instead. These are unilateral changes made with no advance notice given, since the payer typically posts the change on its website,” says Mr. Brodek.

5. Recoupment efforts. Payers will review claims after they’re paid and contact the doctor saying they found a mistake, such as inappropriate coding. They will claim that the doctor now owes them a large sum of money based on a percentage of claims reviewed. “They typically send the doctor a letter that ends with, ‘If you do not pay this amount within 30 days, we will offset the amount due against future payments that we would otherwise make to you,’” says Mr. Brodek.

He recommends that contracts include the doctors’ right to contest an audit so the “payer doesn’t have the unilateral right to disregard the initial coding that the doctor appropriately assigned to the claim and recoup the money anyway,” says Mr. Brodek.

6. Medical network rentals and products. Most contracts say that payers can rent out their medical networks to other health plans, such as HMOs, and that the clinicians agree to comply with all of their policies and procedures. The agreement may also cover the products of other plans.

“The problem is that physicians are not given information about the other plans, including their terms and conditions for getting paid,” says Mr. Brodek. If a problem with payment arises, they have no written agreement with that plan, which makes it harder to enforce.

“That’s why we recommend that doctors negotiate agreements that only cover the main payer. Most of the time, the payer is amenable to putting that language in the contract,” he says.

7. Payer products. In the past several years, a typical contract has included appendices that list the payer’s products, such as Medicare, workers compensation, auto insurance liability, or health care exchange products. Many clinicians don’t realize they can pick the plans they want to participate in by accepting or opting out, says Mr. Brodek.

“We advise clients to limit the contract to what you want covered and to make informed decisions, because some products have low fees set by the states, such as workers compensation and health care exchanges,” says Mr. Brodek.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, say experts in physician-payer contracts.

Many doctors sign long-term agreements and then forget about them, says Marcia Brauchler, president and founder of Physicians’ Ally, Littleton, Colorado, a health care consulting company. “The average doctor is trying to run a practice on 2010 rates because they haven’t touched their insurance contracts for 10 years,” she says.

Payers also make a lot of money by adopting dozens of unilateral policy and procedure changes every year that they know physicians are too busy to read. They are counting on the fact that few doctors will understand what the policy changes are and that even fewer will contest them, says Greg Brodek, JD, chair of the health law practice group and head of the managed care litigation practice at Duane Morris, who represents doctors in disputes with payers.

These experts say doctors can push back on one-sided payer contracts and negotiate changes. Mr. Brodek says some practices have more leverage than others to influence payers – if they are larger, in a specialty that the payer needs in its network, or located in a remote area where the payer has limited options.

Here are seven key areas to pay attention to:

1. Long-term contracts. Most doctors sign multiyear “evergreen” contracts that renew automatically every year. This allows insurers to continue to pay doctors the same rate for years.

To avoid this, doctors should negotiate new rates when their agreements renew or, if they prefer, ask that a cost-of-living adjustment be included in the multiyear contract that applies to subsequent years, says Ms. Brauchler.

2. Fee schedules. Payers will “whitewash” what they’re paying you by saying it’s 100% of the payer fee schedule. When it comes to Medicare, they may be paying you a lot less, says Ms. Brauchler.

“My biggest takeaway is to compare the CPT codes of the payer’s fee schedule against what Medicare allows. For example, for CPT code 99213, a 15-minute established office visit, if Medicare pays you $100 and Aetna pays you $75.00, you’re getting 75% of Medicare,” says Ms. Brauchler. To avoid this, doctors should ask that the contract state that reimbursement be made according to Medicare’s medical policies rather than the payer’s.

3. Audits. Commercial payers will claim they have a contractual right to conduct pre- and post-payment audits of physicians’ claims that can result in reduced payments. The contract only states that if doctors correctly submit claims, they will get paid, not that they will have to go through extra steps, which is a breach of their agreement, says Mr. Brodek.

In his experience, 90% of payers back down when asked to provide the contractual basis to conduct these audits. “Or, they take the position that it’s not in the contract but that they have a policy.”

4. Contract amendments versus policies and procedures. This is a huge area that needs to be clarified in contracts and monitored by providers throughout their relationships with payers. Contracts have three elements: the parties, the services provided, and the payment. Changing any one of those terms requires an amendment and advance written notice that has to be delivered to the other party in a certain way, such as by overnight delivery, says Mr. Brodek.

In addition, both parties have to sign that they agree to an amendment. “But, that’s too cumbersome and complicated for payers who have decided to adopt policies instead. These are unilateral changes made with no advance notice given, since the payer typically posts the change on its website,” says Mr. Brodek.

5. Recoupment efforts. Payers will review claims after they’re paid and contact the doctor saying they found a mistake, such as inappropriate coding. They will claim that the doctor now owes them a large sum of money based on a percentage of claims reviewed. “They typically send the doctor a letter that ends with, ‘If you do not pay this amount within 30 days, we will offset the amount due against future payments that we would otherwise make to you,’” says Mr. Brodek.

He recommends that contracts include the doctors’ right to contest an audit so the “payer doesn’t have the unilateral right to disregard the initial coding that the doctor appropriately assigned to the claim and recoup the money anyway,” says Mr. Brodek.

6. Medical network rentals and products. Most contracts say that payers can rent out their medical networks to other health plans, such as HMOs, and that the clinicians agree to comply with all of their policies and procedures. The agreement may also cover the products of other plans.

“The problem is that physicians are not given information about the other plans, including their terms and conditions for getting paid,” says Mr. Brodek. If a problem with payment arises, they have no written agreement with that plan, which makes it harder to enforce.

“That’s why we recommend that doctors negotiate agreements that only cover the main payer. Most of the time, the payer is amenable to putting that language in the contract,” he says.

7. Payer products. In the past several years, a typical contract has included appendices that list the payer’s products, such as Medicare, workers compensation, auto insurance liability, or health care exchange products. Many clinicians don’t realize they can pick the plans they want to participate in by accepting or opting out, says Mr. Brodek.

“We advise clients to limit the contract to what you want covered and to make informed decisions, because some products have low fees set by the states, such as workers compensation and health care exchanges,” says Mr. Brodek.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, say experts in physician-payer contracts.

Many doctors sign long-term agreements and then forget about them, says Marcia Brauchler, president and founder of Physicians’ Ally, Littleton, Colorado, a health care consulting company. “The average doctor is trying to run a practice on 2010 rates because they haven’t touched their insurance contracts for 10 years,” she says.

Payers also make a lot of money by adopting dozens of unilateral policy and procedure changes every year that they know physicians are too busy to read. They are counting on the fact that few doctors will understand what the policy changes are and that even fewer will contest them, says Greg Brodek, JD, chair of the health law practice group and head of the managed care litigation practice at Duane Morris, who represents doctors in disputes with payers.

These experts say doctors can push back on one-sided payer contracts and negotiate changes. Mr. Brodek says some practices have more leverage than others to influence payers – if they are larger, in a specialty that the payer needs in its network, or located in a remote area where the payer has limited options.

Here are seven key areas to pay attention to:

1. Long-term contracts. Most doctors sign multiyear “evergreen” contracts that renew automatically every year. This allows insurers to continue to pay doctors the same rate for years.

To avoid this, doctors should negotiate new rates when their agreements renew or, if they prefer, ask that a cost-of-living adjustment be included in the multiyear contract that applies to subsequent years, says Ms. Brauchler.

2. Fee schedules. Payers will “whitewash” what they’re paying you by saying it’s 100% of the payer fee schedule. When it comes to Medicare, they may be paying you a lot less, says Ms. Brauchler.

“My biggest takeaway is to compare the CPT codes of the payer’s fee schedule against what Medicare allows. For example, for CPT code 99213, a 15-minute established office visit, if Medicare pays you $100 and Aetna pays you $75.00, you’re getting 75% of Medicare,” says Ms. Brauchler. To avoid this, doctors should ask that the contract state that reimbursement be made according to Medicare’s medical policies rather than the payer’s.

3. Audits. Commercial payers will claim they have a contractual right to conduct pre- and post-payment audits of physicians’ claims that can result in reduced payments. The contract only states that if doctors correctly submit claims, they will get paid, not that they will have to go through extra steps, which is a breach of their agreement, says Mr. Brodek.

In his experience, 90% of payers back down when asked to provide the contractual basis to conduct these audits. “Or, they take the position that it’s not in the contract but that they have a policy.”

4. Contract amendments versus policies and procedures. This is a huge area that needs to be clarified in contracts and monitored by providers throughout their relationships with payers. Contracts have three elements: the parties, the services provided, and the payment. Changing any one of those terms requires an amendment and advance written notice that has to be delivered to the other party in a certain way, such as by overnight delivery, says Mr. Brodek.

In addition, both parties have to sign that they agree to an amendment. “But, that’s too cumbersome and complicated for payers who have decided to adopt policies instead. These are unilateral changes made with no advance notice given, since the payer typically posts the change on its website,” says Mr. Brodek.

5. Recoupment efforts. Payers will review claims after they’re paid and contact the doctor saying they found a mistake, such as inappropriate coding. They will claim that the doctor now owes them a large sum of money based on a percentage of claims reviewed. “They typically send the doctor a letter that ends with, ‘If you do not pay this amount within 30 days, we will offset the amount due against future payments that we would otherwise make to you,’” says Mr. Brodek.

He recommends that contracts include the doctors’ right to contest an audit so the “payer doesn’t have the unilateral right to disregard the initial coding that the doctor appropriately assigned to the claim and recoup the money anyway,” says Mr. Brodek.

6. Medical network rentals and products. Most contracts say that payers can rent out their medical networks to other health plans, such as HMOs, and that the clinicians agree to comply with all of their policies and procedures. The agreement may also cover the products of other plans.

“The problem is that physicians are not given information about the other plans, including their terms and conditions for getting paid,” says Mr. Brodek. If a problem with payment arises, they have no written agreement with that plan, which makes it harder to enforce.

“That’s why we recommend that doctors negotiate agreements that only cover the main payer. Most of the time, the payer is amenable to putting that language in the contract,” he says.

7. Payer products. In the past several years, a typical contract has included appendices that list the payer’s products, such as Medicare, workers compensation, auto insurance liability, or health care exchange products. Many clinicians don’t realize they can pick the plans they want to participate in by accepting or opting out, says Mr. Brodek.

“We advise clients to limit the contract to what you want covered and to make informed decisions, because some products have low fees set by the states, such as workers compensation and health care exchanges,” says Mr. Brodek.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ways to make sure 2022 doesn’t stink for docs

Depending on the data you’re looking at, 40%-60% of physicians are burned out.

Research studies and the eye test reveal the painfully obvious: Colleagues are tired, winded, spent, and at times way past burned out. People aren’t asking me if they’re burned out. They know they’re burned out; heck, they can even recite the Maslach burnout inventory, forward and backward, in a mask, or while completing a COVID quarantine. A fair share of people know the key steps to prevent burnout and promote recovery.

What I’m starting to see more of is, “Why should I even bother to recover from this? Why pick myself up again just to get another occupational stress injury (burnout, demoralization, moral injury, etc.)?” In other words, it’s not just simply about negating burnout; it’s about supporting and facilitating the motivation to work.

We’ve been through so much with COVID that it might be challenging to remember when you saw a truly engaged work environment. No doubt, we have outstanding professionals across medicine who answer the bell every day. However, if you’ve been looking closely, many teams/units have lost a bit of the zip and pep. The synergy and trust aren’t as smooth, and at noon, everyone counts the hours to the end of the shift.

You may be thinking, Well, of course, they are; we’re still amid a pandemic, and people have been through hell. Your observation would be correct, except I’ve personally seen some teams weather the pandemic storm and still remain engaged (some even more involved).

The No. 1 consult result for the GW Resiliency and Well-Being Center, where I work, has been on lectures for burnout. The R&WC has given so many of these lectures that my dreams take the form of a PowerPoint presentation. Overall the talks have gone very well. We’ve added skills sections on practices of whole-person care. We’ve blitzed the daylights out of restorative sleep, yet I know we are still searching for the correct narrative.

Motivated staff, faculty, and students will genuinely take in the information and follow the recommendations; however, they still struggle to find that drive and zest for work. Yes, moving from burnout to neutral is reasonable but likely won’t move the needle of your professional or personal life. We need to have the emotional energy and the clear desire to utilize that energy for a meaningful purpose.

Talking about burnout in specific ways is straightforward and, in my opinion, much easier than talking about engagement. Part of the challenge when trying to discuss engagement is that people can feel invalidated or that you’re telling them to be stoic. Or worse yet, that the problem of burnout primarily lies with them. It’s essential to recognize the role of an organizational factor in burnout (approximately 80%, depending on the study); still, even if you address burnout, people may not be miserable, but it doesn’t mean they will stay at their current job (please cue intro music for the Great Resignation).

Engagement models have existed for some time and certainly have gained much more attention in health care settings over the past 2 decades. Engagement can be described as having three components: dedication, vigor, and absorption. When a person is filling all three of these components over time, presto – you get the much-sought-after state of the supremely engaged professional.

These models definitely give us excellent starting points to approach engagement from a pre-COVID era. In COVID and beyond, I’m not sure how these models will stand up in a hybrid work environment, where autonomy and flexibility could be more valued than ever. Personally, COVID revealed some things I was missing in my work pre-COVID:

- Time to think and process. This was one of the great things about being a consultation-liaison psychiatrist; it was literally feast or famine.

- Doing what I’m talented at and really enjoy.

- Time is short, and I want to be more present in the life of my family.

The list above isn’t exhaustive, but I’ve found them to be my own personal recipe for being engaged. Over the next series of articles, I’m going to focus on engagement and factors related to key resilience. These articles will be informed by a front-line view from my colleagues, and hopefully start to separate the myth from reality on the subject of health professional engagement and resilience.

Everyone be safe and well!

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Depending on the data you’re looking at, 40%-60% of physicians are burned out.

Research studies and the eye test reveal the painfully obvious: Colleagues are tired, winded, spent, and at times way past burned out. People aren’t asking me if they’re burned out. They know they’re burned out; heck, they can even recite the Maslach burnout inventory, forward and backward, in a mask, or while completing a COVID quarantine. A fair share of people know the key steps to prevent burnout and promote recovery.

What I’m starting to see more of is, “Why should I even bother to recover from this? Why pick myself up again just to get another occupational stress injury (burnout, demoralization, moral injury, etc.)?” In other words, it’s not just simply about negating burnout; it’s about supporting and facilitating the motivation to work.

We’ve been through so much with COVID that it might be challenging to remember when you saw a truly engaged work environment. No doubt, we have outstanding professionals across medicine who answer the bell every day. However, if you’ve been looking closely, many teams/units have lost a bit of the zip and pep. The synergy and trust aren’t as smooth, and at noon, everyone counts the hours to the end of the shift.

You may be thinking, Well, of course, they are; we’re still amid a pandemic, and people have been through hell. Your observation would be correct, except I’ve personally seen some teams weather the pandemic storm and still remain engaged (some even more involved).

The No. 1 consult result for the GW Resiliency and Well-Being Center, where I work, has been on lectures for burnout. The R&WC has given so many of these lectures that my dreams take the form of a PowerPoint presentation. Overall the talks have gone very well. We’ve added skills sections on practices of whole-person care. We’ve blitzed the daylights out of restorative sleep, yet I know we are still searching for the correct narrative.

Motivated staff, faculty, and students will genuinely take in the information and follow the recommendations; however, they still struggle to find that drive and zest for work. Yes, moving from burnout to neutral is reasonable but likely won’t move the needle of your professional or personal life. We need to have the emotional energy and the clear desire to utilize that energy for a meaningful purpose.

Talking about burnout in specific ways is straightforward and, in my opinion, much easier than talking about engagement. Part of the challenge when trying to discuss engagement is that people can feel invalidated or that you’re telling them to be stoic. Or worse yet, that the problem of burnout primarily lies with them. It’s essential to recognize the role of an organizational factor in burnout (approximately 80%, depending on the study); still, even if you address burnout, people may not be miserable, but it doesn’t mean they will stay at their current job (please cue intro music for the Great Resignation).

Engagement models have existed for some time and certainly have gained much more attention in health care settings over the past 2 decades. Engagement can be described as having three components: dedication, vigor, and absorption. When a person is filling all three of these components over time, presto – you get the much-sought-after state of the supremely engaged professional.

These models definitely give us excellent starting points to approach engagement from a pre-COVID era. In COVID and beyond, I’m not sure how these models will stand up in a hybrid work environment, where autonomy and flexibility could be more valued than ever. Personally, COVID revealed some things I was missing in my work pre-COVID:

- Time to think and process. This was one of the great things about being a consultation-liaison psychiatrist; it was literally feast or famine.

- Doing what I’m talented at and really enjoy.

- Time is short, and I want to be more present in the life of my family.

The list above isn’t exhaustive, but I’ve found them to be my own personal recipe for being engaged. Over the next series of articles, I’m going to focus on engagement and factors related to key resilience. These articles will be informed by a front-line view from my colleagues, and hopefully start to separate the myth from reality on the subject of health professional engagement and resilience.

Everyone be safe and well!

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Depending on the data you’re looking at, 40%-60% of physicians are burned out.

Research studies and the eye test reveal the painfully obvious: Colleagues are tired, winded, spent, and at times way past burned out. People aren’t asking me if they’re burned out. They know they’re burned out; heck, they can even recite the Maslach burnout inventory, forward and backward, in a mask, or while completing a COVID quarantine. A fair share of people know the key steps to prevent burnout and promote recovery.

What I’m starting to see more of is, “Why should I even bother to recover from this? Why pick myself up again just to get another occupational stress injury (burnout, demoralization, moral injury, etc.)?” In other words, it’s not just simply about negating burnout; it’s about supporting and facilitating the motivation to work.

We’ve been through so much with COVID that it might be challenging to remember when you saw a truly engaged work environment. No doubt, we have outstanding professionals across medicine who answer the bell every day. However, if you’ve been looking closely, many teams/units have lost a bit of the zip and pep. The synergy and trust aren’t as smooth, and at noon, everyone counts the hours to the end of the shift.

You may be thinking, Well, of course, they are; we’re still amid a pandemic, and people have been through hell. Your observation would be correct, except I’ve personally seen some teams weather the pandemic storm and still remain engaged (some even more involved).

The No. 1 consult result for the GW Resiliency and Well-Being Center, where I work, has been on lectures for burnout. The R&WC has given so many of these lectures that my dreams take the form of a PowerPoint presentation. Overall the talks have gone very well. We’ve added skills sections on practices of whole-person care. We’ve blitzed the daylights out of restorative sleep, yet I know we are still searching for the correct narrative.

Motivated staff, faculty, and students will genuinely take in the information and follow the recommendations; however, they still struggle to find that drive and zest for work. Yes, moving from burnout to neutral is reasonable but likely won’t move the needle of your professional or personal life. We need to have the emotional energy and the clear desire to utilize that energy for a meaningful purpose.

Talking about burnout in specific ways is straightforward and, in my opinion, much easier than talking about engagement. Part of the challenge when trying to discuss engagement is that people can feel invalidated or that you’re telling them to be stoic. Or worse yet, that the problem of burnout primarily lies with them. It’s essential to recognize the role of an organizational factor in burnout (approximately 80%, depending on the study); still, even if you address burnout, people may not be miserable, but it doesn’t mean they will stay at their current job (please cue intro music for the Great Resignation).

Engagement models have existed for some time and certainly have gained much more attention in health care settings over the past 2 decades. Engagement can be described as having three components: dedication, vigor, and absorption. When a person is filling all three of these components over time, presto – you get the much-sought-after state of the supremely engaged professional.

These models definitely give us excellent starting points to approach engagement from a pre-COVID era. In COVID and beyond, I’m not sure how these models will stand up in a hybrid work environment, where autonomy and flexibility could be more valued than ever. Personally, COVID revealed some things I was missing in my work pre-COVID:

- Time to think and process. This was one of the great things about being a consultation-liaison psychiatrist; it was literally feast or famine.

- Doing what I’m talented at and really enjoy.

- Time is short, and I want to be more present in the life of my family.

The list above isn’t exhaustive, but I’ve found them to be my own personal recipe for being engaged. Over the next series of articles, I’m going to focus on engagement and factors related to key resilience. These articles will be informed by a front-line view from my colleagues, and hopefully start to separate the myth from reality on the subject of health professional engagement and resilience.

Everyone be safe and well!

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Does COVID-19 induce type 1 diabetes in kids? Jury still out

Two new studies from different parts of the world have identified an increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but the reasons still aren’t clear.

The findings from the two studies, in Germany and the United States, align closely, endocrinologist Jane J. Kim, MD, professor of pediatrics and principal investigator of the U.S. study, told this news organization. “I think that the general conclusion based on their data and our data is that there appears to be an increased rate of new type 1 diabetes diagnoses in children since the onset of the pandemic.”

Dr. Kim noted that because her group’s data pertain to just a single center, she is “heartened to see that the [German team’s] general conclusions are the same as ours.” Moreover, she pointed out that other studies examining this question came from Europe early in the pandemic, whereas “now both they [the German group] and we have had the opportunity to look at what’s happening over a longer period of time.”

But the reason for the association remains unclear. Some answers may be forthcoming from a database designed in mid-2020 specifically to examine the relationship between COVID-19 and new-onset diabetes. Called CoviDiab, the registry aims “to establish the extent and characteristics of new-onset, COVID-19–related diabetes and to investigate its pathogenesis, management, and outcomes,” according to the website.

The first new study, a multicenter German diabetes registry study, was published online Jan. 17 in Diabetes Care by Clemens Kamrath, MD, of Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany, and colleagues.

The other, from Rady Children’s Hospital of San Diego, was published online Jan. 24 in JAMA Pediatrics by Bethany L. Gottesman, MD, and colleagues, all with the University of California, San Diego.

Mechanisms likely to differ for type 1 versus type 2 diabetes

Neither the German nor the U.S. investigators were able to directly correlate current or prior SARS-CoV-2 infection in children with the subsequent development of type 1 diabetes.

Earlier this month, a study from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did examine that issue, but it also included youth with type 2 diabetes and did not separate out the two groups.

Dr. Kim said her institution has also seen an increase in type 2 diabetes among youth since the COVID-19 pandemic began but did not include that in their current article.

“When we started looking at our data, diabetes and COVID-19 in adults had been relatively well established. To see an increase in type 2 [diabetes] was not so surprising to our group. But we had the sense we were seeing more patients with type 1, and when we looked at our hospital that was very much the case. I think that was a surprise to people,” said Dr. Kim.

Although a direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 on pancreatic beta cells has been proposed, in both the German and San Diego datasets the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was confirmed with autoantibodies that are typically present years prior to the onset of clinical symptoms.

The German group suggests possible other explanations for the link, including the lack of immune system exposure to other common pediatric infections during pandemic-necessitated social distancing – the so-called hygiene hypothesis – as well as the possible role of psychological stress, which several studies have linked to type 1 diabetes.

But as of now, Dr. Kim said, “Nobody really knows.”

Is the effect direct or indirect?

Using data from the multicenter German Diabetes Prospective Follow-up Registry, Dr. Kamrath and colleagues compared the incidence of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents from Jan. 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021 with the incidence in 2011-2019.

During the pandemic period, a total of 5,162 youth were newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at 236 German centers. That incidence, 24.4 per 100,000 patient-years, was significantly higher than the 21.2 per 100,000 patient-years expected based on the prior decade, with an incidence rate ratio of 1.15 (P < .001). The increase was similar in both males and females.

There was a difference by age, however, as the phenomenon appeared to be limited to the preadolescent age groups. The incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for ages below 6 years and 6-11 years were 1.23 and 1.18 (both P < .001), respectively, compared to a nonsignificant IRR of 1.06 (P = .13) in those aged 12-17 years.

Compared with the expected monthly incidence, the observed incidence was significantly higher in June 2020 (IRR, 1.43; P = .003), July 2020 (IRR, 1.48; P < 0.001), March 2021 (IRR, 1.29; P = .028), and June 2021 (IRR, 1.39; P = .01).