User login

Twelve-month overall survival benefit with ribociclib for metastatic breast cancer

“Based on these results, ribociclib and letrozole should be considered the preferred treatment option,” said lead investigator Gabriel N. Hortobagyi, MD, a breast cancer medical oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

He presented the definitive overall survival results from MONALESSA-2 which randomized 668 patients equally and in the first line to either ribociclib or placebo on a background of standard dose letrozole.

At a median follow up of 6.6 years, median overall survival with ribociclib was 63.9 months versus 51.4 months in the placebo arm, a 24% reduction in the relative risk of death (P = .004).

It was the first report of a median overall survival (OS) exceeding 5 years in a phase 3 trial for advanced breast cancer. The estimated 6-year OS rate was 44.2% for ribociclib versus 32.0% with placebo.

“These are really impressive results” and support the use of CDK 4/6 inhibitors in the front-line setting,” said study discussant Gonzalo Gomez Abuin, MD, a medical oncologist at Hospital Alemán in Bueno Aires.

Ribociclib and other CDK 4/6 inhibitors have shown consistent progression-free survival benefit for metastatic disease, but ribociclib is the first of the major phase 3 trials with definitive overall survival results. They have “been long awaited,” Dr. Abuin said.

The overall survival benefit in MONALESSA-2 began to emerge at around 20 months and continued to increase over time.

Women had no prior CDK4/6 inhibitor treatment, chemotherapy, or endocrine therapy for metastatic disease. “They represented a pure first-line population,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

Among other benefits, the time to first chemotherapy was a median of 50.6 months with ribociclib versus 38.9 months with placebo, so patients “had an extra year of delay before chemotherapy was utilized,” he said.

In general, Dr. Abuin said, we “see a consistent benefit with CDK 4/6 inhibitors in metastatic breast cancer across different settings.”

However, “it’s a little intriguing” that in a subgroup analysis of non–de novo disease, the overall survival benefit with ribociclib had a hazard ratio of 0.91, whereas the progression-free survival benefit was robust and statistically significant in an earlier report.

“This has been an important question, but I would caution all of us not to make too much out of the forest plot,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

“There are a number of hypotheses one could come up with that could explain why the de novo and non–de novo populations faired differently in overall survival as opposed to progression-free survival, but there is also the simple possibility that this is a statistical fluke,” he said.

“We are in the process of analyzing this particular observation. In the meantime, I think we should just take the overall survival results of the entire population as the lead answer, and not follow the subgroup analysis until further information is available,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

No new ribociclib safety signals were observed in the trial. The most common adverse events were neutropenia and liver function abnormalities, but they were “largely asymptomatic laboratory findings and completely reversible,” he said.

Twice as many patients treated with ribociclib developed prolonged QT intervals, but again, “no clinical consequences of this EKG finding were detected,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

Less than 1% of patients in the ribociclib arm developed interstitial lung disease. The majority of safety events occurred in the first 12 months of treatment.

The work was funded by Novartis, maker of both ribociclib and letrozole. Dr. Hortobagyi reported receiving an institutional grant from the company and personal fees related to the trial. Other investigators disclosed ties to Novartis. Dr. Abuin reported relationships with many companies, including Novartis.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

“Based on these results, ribociclib and letrozole should be considered the preferred treatment option,” said lead investigator Gabriel N. Hortobagyi, MD, a breast cancer medical oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

He presented the definitive overall survival results from MONALESSA-2 which randomized 668 patients equally and in the first line to either ribociclib or placebo on a background of standard dose letrozole.

At a median follow up of 6.6 years, median overall survival with ribociclib was 63.9 months versus 51.4 months in the placebo arm, a 24% reduction in the relative risk of death (P = .004).

It was the first report of a median overall survival (OS) exceeding 5 years in a phase 3 trial for advanced breast cancer. The estimated 6-year OS rate was 44.2% for ribociclib versus 32.0% with placebo.

“These are really impressive results” and support the use of CDK 4/6 inhibitors in the front-line setting,” said study discussant Gonzalo Gomez Abuin, MD, a medical oncologist at Hospital Alemán in Bueno Aires.

Ribociclib and other CDK 4/6 inhibitors have shown consistent progression-free survival benefit for metastatic disease, but ribociclib is the first of the major phase 3 trials with definitive overall survival results. They have “been long awaited,” Dr. Abuin said.

The overall survival benefit in MONALESSA-2 began to emerge at around 20 months and continued to increase over time.

Women had no prior CDK4/6 inhibitor treatment, chemotherapy, or endocrine therapy for metastatic disease. “They represented a pure first-line population,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

Among other benefits, the time to first chemotherapy was a median of 50.6 months with ribociclib versus 38.9 months with placebo, so patients “had an extra year of delay before chemotherapy was utilized,” he said.

In general, Dr. Abuin said, we “see a consistent benefit with CDK 4/6 inhibitors in metastatic breast cancer across different settings.”

However, “it’s a little intriguing” that in a subgroup analysis of non–de novo disease, the overall survival benefit with ribociclib had a hazard ratio of 0.91, whereas the progression-free survival benefit was robust and statistically significant in an earlier report.

“This has been an important question, but I would caution all of us not to make too much out of the forest plot,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

“There are a number of hypotheses one could come up with that could explain why the de novo and non–de novo populations faired differently in overall survival as opposed to progression-free survival, but there is also the simple possibility that this is a statistical fluke,” he said.

“We are in the process of analyzing this particular observation. In the meantime, I think we should just take the overall survival results of the entire population as the lead answer, and not follow the subgroup analysis until further information is available,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

No new ribociclib safety signals were observed in the trial. The most common adverse events were neutropenia and liver function abnormalities, but they were “largely asymptomatic laboratory findings and completely reversible,” he said.

Twice as many patients treated with ribociclib developed prolonged QT intervals, but again, “no clinical consequences of this EKG finding were detected,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

Less than 1% of patients in the ribociclib arm developed interstitial lung disease. The majority of safety events occurred in the first 12 months of treatment.

The work was funded by Novartis, maker of both ribociclib and letrozole. Dr. Hortobagyi reported receiving an institutional grant from the company and personal fees related to the trial. Other investigators disclosed ties to Novartis. Dr. Abuin reported relationships with many companies, including Novartis.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

“Based on these results, ribociclib and letrozole should be considered the preferred treatment option,” said lead investigator Gabriel N. Hortobagyi, MD, a breast cancer medical oncologist at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

He presented the definitive overall survival results from MONALESSA-2 which randomized 668 patients equally and in the first line to either ribociclib or placebo on a background of standard dose letrozole.

At a median follow up of 6.6 years, median overall survival with ribociclib was 63.9 months versus 51.4 months in the placebo arm, a 24% reduction in the relative risk of death (P = .004).

It was the first report of a median overall survival (OS) exceeding 5 years in a phase 3 trial for advanced breast cancer. The estimated 6-year OS rate was 44.2% for ribociclib versus 32.0% with placebo.

“These are really impressive results” and support the use of CDK 4/6 inhibitors in the front-line setting,” said study discussant Gonzalo Gomez Abuin, MD, a medical oncologist at Hospital Alemán in Bueno Aires.

Ribociclib and other CDK 4/6 inhibitors have shown consistent progression-free survival benefit for metastatic disease, but ribociclib is the first of the major phase 3 trials with definitive overall survival results. They have “been long awaited,” Dr. Abuin said.

The overall survival benefit in MONALESSA-2 began to emerge at around 20 months and continued to increase over time.

Women had no prior CDK4/6 inhibitor treatment, chemotherapy, or endocrine therapy for metastatic disease. “They represented a pure first-line population,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

Among other benefits, the time to first chemotherapy was a median of 50.6 months with ribociclib versus 38.9 months with placebo, so patients “had an extra year of delay before chemotherapy was utilized,” he said.

In general, Dr. Abuin said, we “see a consistent benefit with CDK 4/6 inhibitors in metastatic breast cancer across different settings.”

However, “it’s a little intriguing” that in a subgroup analysis of non–de novo disease, the overall survival benefit with ribociclib had a hazard ratio of 0.91, whereas the progression-free survival benefit was robust and statistically significant in an earlier report.

“This has been an important question, but I would caution all of us not to make too much out of the forest plot,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

“There are a number of hypotheses one could come up with that could explain why the de novo and non–de novo populations faired differently in overall survival as opposed to progression-free survival, but there is also the simple possibility that this is a statistical fluke,” he said.

“We are in the process of analyzing this particular observation. In the meantime, I think we should just take the overall survival results of the entire population as the lead answer, and not follow the subgroup analysis until further information is available,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

No new ribociclib safety signals were observed in the trial. The most common adverse events were neutropenia and liver function abnormalities, but they were “largely asymptomatic laboratory findings and completely reversible,” he said.

Twice as many patients treated with ribociclib developed prolonged QT intervals, but again, “no clinical consequences of this EKG finding were detected,” Dr. Hortobagyi said.

Less than 1% of patients in the ribociclib arm developed interstitial lung disease. The majority of safety events occurred in the first 12 months of treatment.

The work was funded by Novartis, maker of both ribociclib and letrozole. Dr. Hortobagyi reported receiving an institutional grant from the company and personal fees related to the trial. Other investigators disclosed ties to Novartis. Dr. Abuin reported relationships with many companies, including Novartis.

This article was updated 9/24/21.

FROM ESMO 2021

Nurses ‘at the breaking point,’ consider quitting due to COVID issues: Survey

As hospitals have been flooded with critically ill patients, nurses have been overwhelmed.

“What we’re hearing from our nurses is really shocking,” Amanda Bettencourt, PhD, APRN, CCRN-K, president-elect of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), said in an interview. “They’re saying they’re at the breaking point.”

Between Aug. 26 and Aug. 30, the AACN surveyed more than 6,000 critical care nurses, zeroing in on four key questions regarding the pandemic and its impact on nursing. The results were alarming – not only with regard to individual nurses but also for the nursing profession and the future of health care. A full 66% of those surveyed said their experiences during the pandemic have caused them to consider leaving nursing. The respondents’ take on their colleagues was even more concerning. Ninety-two percent agreed with the following two statements: “I believe the pandemic has depleted nurses at my hospital. Their careers will be shorter than they intended.”

“This puts the entire health care system at risk,” says Dr. Bettencourt, assistant professor in the department of family and community health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia. Intensive care unit (ICU) nurses are highly trained and are skilled in caring for critically ill patients with complex medical needs. “It’s not easy to replace a critical care nurse when one leaves,” she said.

And when nurses leave, patients suffer, said Beth Wathen, MSN, RN, CCRN-K, president of the ACCN and frontline nurse at Children’s Hospital Colorado, in Aurora. “Hospitals can have all the beds and all the rooms and all the equipment they want, but without nurses and others at the front lines to provide that essential care, none of it really matters, whether we’re talking about caring for COVID patients or caring for patients with other health ailments.”

Heartbreak of the unvaccinated

The problem is not just overwork because of the flood of COVID-19 patients. The emotional strain is enormous as well. “What’s demoralizing for us is not that patients are sick and that it’s physically exhausting to take care of sick patients. We’re used to that,” said Dr. Bettencourt.

But few nurses have experienced the sheer magnitude of patients caused by this pandemic. “The past 18 months have been grueling,” says Ms. Wathen. “The burden on frontline caregivers and our nurses at the front line has been immense.”

The situation is made worse by how unnecessary much of the suffering is at this point. Seventy-six percent of the survey’s respondents agreed with the following statement: “People who hold out on getting vaccinated undermine nurses’ physical and mental well-being.” That comment doesn’t convey the nature or extent of the effect on caregivers’ well-being. “That 9 out of 10 of the people we’re seeing in ICU right now are unvaccinated just adds to the sense of heartbreak and frustration,” says Ms. Wathen. “These deaths don’t have to be happening right now. And that’s hard to bear witness to.”

The politicization of public health has also taken a toll. “That’s been the hard part of this entire pandemic,” says Ms. Wathen. “This really isn’t at all about politics. This is about your health; this is about my health. This is about our collective health as a community and as a country.”

Like the rest of the world, nurses are also concerned about their own loved ones. The survey statement, “I fear taking care of patients with COVID puts my family’s health at risk,” garnered 67% agreement. Ms. Wathen points out that nurses take the appropriate precautions but still worry about taking infection home to their families. “This disease is a tricky one,” she says. She points out that until this pandemic is over, in addition to being vaccinated, nurses and the public still need to be vigilant about wearing masks, social distancing, and taking other precautions to ensure the safety of us all. “Our individual decisions don’t just affect ourselves. They affect our family, the people in our circle, and the people in our community,” she said.

Avoiding a professional exodus

It’s too early yet to have reliable national data on how many nurses have already left their jobs because of COVID-19, but it is clear that there are too few nurses of all kinds. The American Nurses Association sent a letter to the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services urging the agency to declare the nursing shortage a crisis and to take immediate steps to find solutions.

The nursing shortage predates the pandemic, and COVID-19 has brought a simmering problem to the boil. Nurses are calling on the public and the health care system for help. From inside the industry, the needs are pretty much what they were before the pandemic. Dr. Bettencourt and Ms. Wathen point to the need for supportive leadership, healthy work environments, sufficient staffing to meet patients’ needs, and a voice in decisions, such as decisions about staffing, that affect nurses and their patients. Nurses want to be heard and appreciated. “It’s not that these are new things,” said Dr. Bettencourt. “We just need them even more now because we’re stressed even more than we were before.”

Critical care nurses have a different request of the public. They’re asking – pleading, actually – with the public to get vaccinated, wear masks in public, practice social distancing, and bring this pandemic to an end.

“COVID kills, and it’s a really difficult, tragic, and lonely death,” said Ms. Wathen. “We’ve witnessed hundreds of thousands of those deaths. But now we have a way to stop it. If many more people get vaccinated, we can stop this pandemic. And hopefully that will stop this current trend of nurses leaving.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As hospitals have been flooded with critically ill patients, nurses have been overwhelmed.

“What we’re hearing from our nurses is really shocking,” Amanda Bettencourt, PhD, APRN, CCRN-K, president-elect of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), said in an interview. “They’re saying they’re at the breaking point.”

Between Aug. 26 and Aug. 30, the AACN surveyed more than 6,000 critical care nurses, zeroing in on four key questions regarding the pandemic and its impact on nursing. The results were alarming – not only with regard to individual nurses but also for the nursing profession and the future of health care. A full 66% of those surveyed said their experiences during the pandemic have caused them to consider leaving nursing. The respondents’ take on their colleagues was even more concerning. Ninety-two percent agreed with the following two statements: “I believe the pandemic has depleted nurses at my hospital. Their careers will be shorter than they intended.”

“This puts the entire health care system at risk,” says Dr. Bettencourt, assistant professor in the department of family and community health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia. Intensive care unit (ICU) nurses are highly trained and are skilled in caring for critically ill patients with complex medical needs. “It’s not easy to replace a critical care nurse when one leaves,” she said.

And when nurses leave, patients suffer, said Beth Wathen, MSN, RN, CCRN-K, president of the ACCN and frontline nurse at Children’s Hospital Colorado, in Aurora. “Hospitals can have all the beds and all the rooms and all the equipment they want, but without nurses and others at the front lines to provide that essential care, none of it really matters, whether we’re talking about caring for COVID patients or caring for patients with other health ailments.”

Heartbreak of the unvaccinated

The problem is not just overwork because of the flood of COVID-19 patients. The emotional strain is enormous as well. “What’s demoralizing for us is not that patients are sick and that it’s physically exhausting to take care of sick patients. We’re used to that,” said Dr. Bettencourt.

But few nurses have experienced the sheer magnitude of patients caused by this pandemic. “The past 18 months have been grueling,” says Ms. Wathen. “The burden on frontline caregivers and our nurses at the front line has been immense.”

The situation is made worse by how unnecessary much of the suffering is at this point. Seventy-six percent of the survey’s respondents agreed with the following statement: “People who hold out on getting vaccinated undermine nurses’ physical and mental well-being.” That comment doesn’t convey the nature or extent of the effect on caregivers’ well-being. “That 9 out of 10 of the people we’re seeing in ICU right now are unvaccinated just adds to the sense of heartbreak and frustration,” says Ms. Wathen. “These deaths don’t have to be happening right now. And that’s hard to bear witness to.”

The politicization of public health has also taken a toll. “That’s been the hard part of this entire pandemic,” says Ms. Wathen. “This really isn’t at all about politics. This is about your health; this is about my health. This is about our collective health as a community and as a country.”

Like the rest of the world, nurses are also concerned about their own loved ones. The survey statement, “I fear taking care of patients with COVID puts my family’s health at risk,” garnered 67% agreement. Ms. Wathen points out that nurses take the appropriate precautions but still worry about taking infection home to their families. “This disease is a tricky one,” she says. She points out that until this pandemic is over, in addition to being vaccinated, nurses and the public still need to be vigilant about wearing masks, social distancing, and taking other precautions to ensure the safety of us all. “Our individual decisions don’t just affect ourselves. They affect our family, the people in our circle, and the people in our community,” she said.

Avoiding a professional exodus

It’s too early yet to have reliable national data on how many nurses have already left their jobs because of COVID-19, but it is clear that there are too few nurses of all kinds. The American Nurses Association sent a letter to the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services urging the agency to declare the nursing shortage a crisis and to take immediate steps to find solutions.

The nursing shortage predates the pandemic, and COVID-19 has brought a simmering problem to the boil. Nurses are calling on the public and the health care system for help. From inside the industry, the needs are pretty much what they were before the pandemic. Dr. Bettencourt and Ms. Wathen point to the need for supportive leadership, healthy work environments, sufficient staffing to meet patients’ needs, and a voice in decisions, such as decisions about staffing, that affect nurses and their patients. Nurses want to be heard and appreciated. “It’s not that these are new things,” said Dr. Bettencourt. “We just need them even more now because we’re stressed even more than we were before.”

Critical care nurses have a different request of the public. They’re asking – pleading, actually – with the public to get vaccinated, wear masks in public, practice social distancing, and bring this pandemic to an end.

“COVID kills, and it’s a really difficult, tragic, and lonely death,” said Ms. Wathen. “We’ve witnessed hundreds of thousands of those deaths. But now we have a way to stop it. If many more people get vaccinated, we can stop this pandemic. And hopefully that will stop this current trend of nurses leaving.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As hospitals have been flooded with critically ill patients, nurses have been overwhelmed.

“What we’re hearing from our nurses is really shocking,” Amanda Bettencourt, PhD, APRN, CCRN-K, president-elect of the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN), said in an interview. “They’re saying they’re at the breaking point.”

Between Aug. 26 and Aug. 30, the AACN surveyed more than 6,000 critical care nurses, zeroing in on four key questions regarding the pandemic and its impact on nursing. The results were alarming – not only with regard to individual nurses but also for the nursing profession and the future of health care. A full 66% of those surveyed said their experiences during the pandemic have caused them to consider leaving nursing. The respondents’ take on their colleagues was even more concerning. Ninety-two percent agreed with the following two statements: “I believe the pandemic has depleted nurses at my hospital. Their careers will be shorter than they intended.”

“This puts the entire health care system at risk,” says Dr. Bettencourt, assistant professor in the department of family and community health at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia. Intensive care unit (ICU) nurses are highly trained and are skilled in caring for critically ill patients with complex medical needs. “It’s not easy to replace a critical care nurse when one leaves,” she said.

And when nurses leave, patients suffer, said Beth Wathen, MSN, RN, CCRN-K, president of the ACCN and frontline nurse at Children’s Hospital Colorado, in Aurora. “Hospitals can have all the beds and all the rooms and all the equipment they want, but without nurses and others at the front lines to provide that essential care, none of it really matters, whether we’re talking about caring for COVID patients or caring for patients with other health ailments.”

Heartbreak of the unvaccinated

The problem is not just overwork because of the flood of COVID-19 patients. The emotional strain is enormous as well. “What’s demoralizing for us is not that patients are sick and that it’s physically exhausting to take care of sick patients. We’re used to that,” said Dr. Bettencourt.

But few nurses have experienced the sheer magnitude of patients caused by this pandemic. “The past 18 months have been grueling,” says Ms. Wathen. “The burden on frontline caregivers and our nurses at the front line has been immense.”

The situation is made worse by how unnecessary much of the suffering is at this point. Seventy-six percent of the survey’s respondents agreed with the following statement: “People who hold out on getting vaccinated undermine nurses’ physical and mental well-being.” That comment doesn’t convey the nature or extent of the effect on caregivers’ well-being. “That 9 out of 10 of the people we’re seeing in ICU right now are unvaccinated just adds to the sense of heartbreak and frustration,” says Ms. Wathen. “These deaths don’t have to be happening right now. And that’s hard to bear witness to.”

The politicization of public health has also taken a toll. “That’s been the hard part of this entire pandemic,” says Ms. Wathen. “This really isn’t at all about politics. This is about your health; this is about my health. This is about our collective health as a community and as a country.”

Like the rest of the world, nurses are also concerned about their own loved ones. The survey statement, “I fear taking care of patients with COVID puts my family’s health at risk,” garnered 67% agreement. Ms. Wathen points out that nurses take the appropriate precautions but still worry about taking infection home to their families. “This disease is a tricky one,” she says. She points out that until this pandemic is over, in addition to being vaccinated, nurses and the public still need to be vigilant about wearing masks, social distancing, and taking other precautions to ensure the safety of us all. “Our individual decisions don’t just affect ourselves. They affect our family, the people in our circle, and the people in our community,” she said.

Avoiding a professional exodus

It’s too early yet to have reliable national data on how many nurses have already left their jobs because of COVID-19, but it is clear that there are too few nurses of all kinds. The American Nurses Association sent a letter to the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services urging the agency to declare the nursing shortage a crisis and to take immediate steps to find solutions.

The nursing shortage predates the pandemic, and COVID-19 has brought a simmering problem to the boil. Nurses are calling on the public and the health care system for help. From inside the industry, the needs are pretty much what they were before the pandemic. Dr. Bettencourt and Ms. Wathen point to the need for supportive leadership, healthy work environments, sufficient staffing to meet patients’ needs, and a voice in decisions, such as decisions about staffing, that affect nurses and their patients. Nurses want to be heard and appreciated. “It’s not that these are new things,” said Dr. Bettencourt. “We just need them even more now because we’re stressed even more than we were before.”

Critical care nurses have a different request of the public. They’re asking – pleading, actually – with the public to get vaccinated, wear masks in public, practice social distancing, and bring this pandemic to an end.

“COVID kills, and it’s a really difficult, tragic, and lonely death,” said Ms. Wathen. “We’ve witnessed hundreds of thousands of those deaths. But now we have a way to stop it. If many more people get vaccinated, we can stop this pandemic. And hopefully that will stop this current trend of nurses leaving.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Texas doctor admits to violating abortion ban

A Texas doctor revealed in a Washington Post op-ed Sept. 18 that he violated the state ban on abortions performed beyond 6 weeks -- a move he knows could come with legal consequences.

San Antonio doctor Alan Braid, MD, said the new statewide restrictions reminded him of darker days during his 1972 obstetrics and gynecology residency, when he saw three teenagers die from illegal abortions.

“For me, it is 1972 all over again,” he wrote. “And that is why, on the morning of Sept. 6, I provided an abortion to a woman who, though still in her first trimester, was beyond the state’s new limit. I acted because I had a duty of care to this patient, as I do for all patients, and because she has a fundamental right to receive this care.”

“I fully understood that there could be legal consequences -- but I wanted to make sure that Texas didn’t get away with its bid to prevent this blatantly unconstitutional law from being tested,” he continued.

According to The Washington Post, Dr. Braid’s wish may come true. Two lawsuits against were filed Sept. 20. In one, a prisoner in Arkansas said he filed the suit in part because he could receive $10,000 if successful, according to the Post. The second was filed by a man in Chicago who wants the law struck down.

Dr. Braid’s op-ed is the first public admission to violating a Texas state law that took effect Sept. 1 banning abortion once a fetal heartbeat is detected. The controversial policy gives private citizens the right to bring civil litigation -- resulting in at least $10,000 in damages -- against providers and anyone else involved in the process.

Since the law went into effect, most patients seeking abortions are too far along to qualify, Dr. Braid wrote.

“I tell them that we can offer services only if we cannot see the presence of cardiac activity on an ultrasound, which usually occurs at about six weeks, before most people know they are pregnant. The tension is unbearable as they lie there, waiting to hear their fate,” he wrote.

“I understand that by providing an abortion beyond the new legal limit, I am taking a personal risk, but it’s something I believe in strongly,” he continued. “Represented by the Center for Reproductive Rights, my clinics are among the plaintiffs in an ongoing federal lawsuit to stop S.B. 8.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

A Texas doctor revealed in a Washington Post op-ed Sept. 18 that he violated the state ban on abortions performed beyond 6 weeks -- a move he knows could come with legal consequences.

San Antonio doctor Alan Braid, MD, said the new statewide restrictions reminded him of darker days during his 1972 obstetrics and gynecology residency, when he saw three teenagers die from illegal abortions.

“For me, it is 1972 all over again,” he wrote. “And that is why, on the morning of Sept. 6, I provided an abortion to a woman who, though still in her first trimester, was beyond the state’s new limit. I acted because I had a duty of care to this patient, as I do for all patients, and because she has a fundamental right to receive this care.”

“I fully understood that there could be legal consequences -- but I wanted to make sure that Texas didn’t get away with its bid to prevent this blatantly unconstitutional law from being tested,” he continued.

According to The Washington Post, Dr. Braid’s wish may come true. Two lawsuits against were filed Sept. 20. In one, a prisoner in Arkansas said he filed the suit in part because he could receive $10,000 if successful, according to the Post. The second was filed by a man in Chicago who wants the law struck down.

Dr. Braid’s op-ed is the first public admission to violating a Texas state law that took effect Sept. 1 banning abortion once a fetal heartbeat is detected. The controversial policy gives private citizens the right to bring civil litigation -- resulting in at least $10,000 in damages -- against providers and anyone else involved in the process.

Since the law went into effect, most patients seeking abortions are too far along to qualify, Dr. Braid wrote.

“I tell them that we can offer services only if we cannot see the presence of cardiac activity on an ultrasound, which usually occurs at about six weeks, before most people know they are pregnant. The tension is unbearable as they lie there, waiting to hear their fate,” he wrote.

“I understand that by providing an abortion beyond the new legal limit, I am taking a personal risk, but it’s something I believe in strongly,” he continued. “Represented by the Center for Reproductive Rights, my clinics are among the plaintiffs in an ongoing federal lawsuit to stop S.B. 8.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

A Texas doctor revealed in a Washington Post op-ed Sept. 18 that he violated the state ban on abortions performed beyond 6 weeks -- a move he knows could come with legal consequences.

San Antonio doctor Alan Braid, MD, said the new statewide restrictions reminded him of darker days during his 1972 obstetrics and gynecology residency, when he saw three teenagers die from illegal abortions.

“For me, it is 1972 all over again,” he wrote. “And that is why, on the morning of Sept. 6, I provided an abortion to a woman who, though still in her first trimester, was beyond the state’s new limit. I acted because I had a duty of care to this patient, as I do for all patients, and because she has a fundamental right to receive this care.”

“I fully understood that there could be legal consequences -- but I wanted to make sure that Texas didn’t get away with its bid to prevent this blatantly unconstitutional law from being tested,” he continued.

According to The Washington Post, Dr. Braid’s wish may come true. Two lawsuits against were filed Sept. 20. In one, a prisoner in Arkansas said he filed the suit in part because he could receive $10,000 if successful, according to the Post. The second was filed by a man in Chicago who wants the law struck down.

Dr. Braid’s op-ed is the first public admission to violating a Texas state law that took effect Sept. 1 banning abortion once a fetal heartbeat is detected. The controversial policy gives private citizens the right to bring civil litigation -- resulting in at least $10,000 in damages -- against providers and anyone else involved in the process.

Since the law went into effect, most patients seeking abortions are too far along to qualify, Dr. Braid wrote.

“I tell them that we can offer services only if we cannot see the presence of cardiac activity on an ultrasound, which usually occurs at about six weeks, before most people know they are pregnant. The tension is unbearable as they lie there, waiting to hear their fate,” he wrote.

“I understand that by providing an abortion beyond the new legal limit, I am taking a personal risk, but it’s something I believe in strongly,” he continued. “Represented by the Center for Reproductive Rights, my clinics are among the plaintiffs in an ongoing federal lawsuit to stop S.B. 8.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

Embedding diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice in hospital medicine

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

A road map for success

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

6-year-old with loud wheezing, difficulty breathing

The patient is probably presenting with a moderate asthma exacerbation. To confirm the diagnosis, spirometry assessments should be performed to establish the presence of baseline airway obstruction and determine its severity. Measurements should be obtained before and after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator. In addition, chest radiography can help to exclude other diagnoses, and pulse oximetry can exclude hypoxemia.

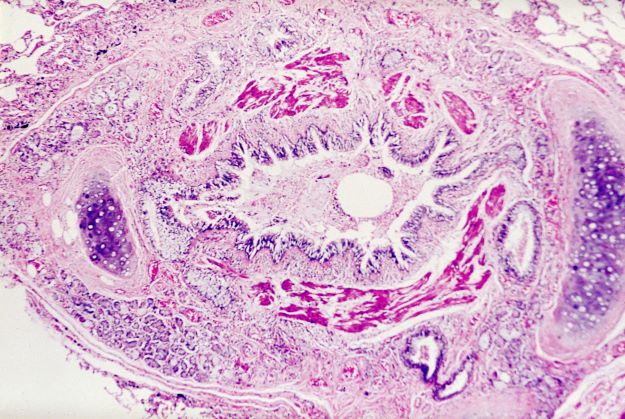

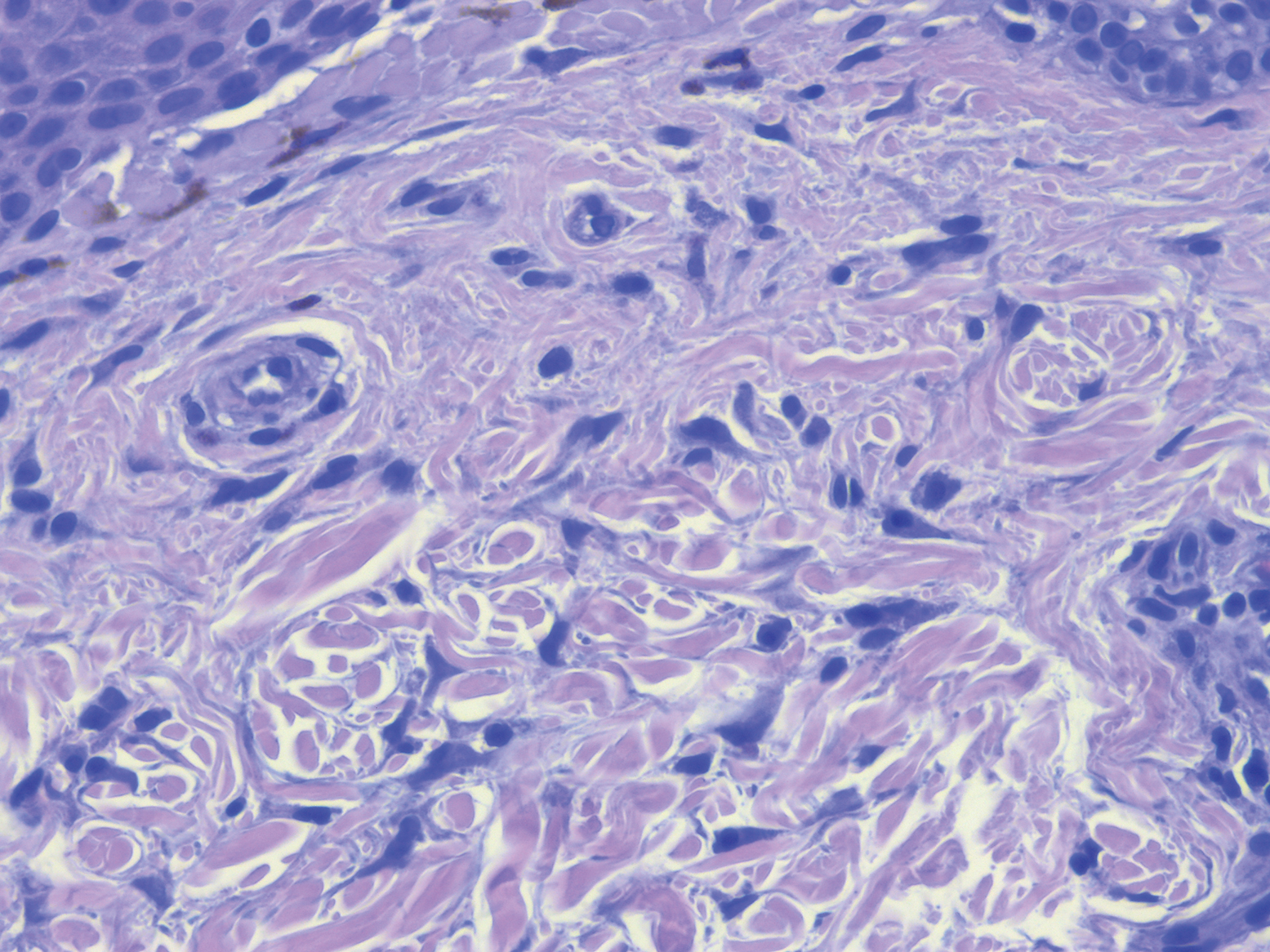

Asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease and the most common chronic condition among children. Histologically, it is marked by vascular congestion, increased vascular permeability, increased tissue volume, and the presence of an exudate. Because the asthmatic lung undergoes a cycle of injury, repair, and regeneration, inflammation creates histologic changes and functional abnormalities in the airway mucosal epithelium. It is hypothesized that these changes play a major role in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Eosinophilic infiltration is a hallmark of this inflammatory activity. Histologic evaluations of the large airways may also reveal narrowing of lumina, bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial denudation, and mucus plugs. Other relevant findings can include epithelial desquamation and hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, subbasement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy or hyperplasia, and submucosal gland hypertrophy. In patients with severe asthma, the basement membrane may be significantly thickened. In terms of the small airways, pathologic study from the lungs of living patients is rarely undertaken, and therefore the histopathologic findings of asthma at the level of the distal airways and alveolated lung parenchyma remains largely unknown.

Asthma is treated using a stepwise approach. As directed for pediatric patients younger than 5 years, the patient in this case may be provided with an as-needed inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) and should be followed up every 2-6 weeks while gaining control of her symptoms.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland; Chief of Critical Care, Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Landstuhl, Germany.

Nathan L. Boyer, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is probably presenting with a moderate asthma exacerbation. To confirm the diagnosis, spirometry assessments should be performed to establish the presence of baseline airway obstruction and determine its severity. Measurements should be obtained before and after inhalation of a short-acting bronchodilator. In addition, chest radiography can help to exclude other diagnoses, and pulse oximetry can exclude hypoxemia.

Asthma is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease and the most common chronic condition among children. Histologically, it is marked by vascular congestion, increased vascular permeability, increased tissue volume, and the presence of an exudate. Because the asthmatic lung undergoes a cycle of injury, repair, and regeneration, inflammation creates histologic changes and functional abnormalities in the airway mucosal epithelium. It is hypothesized that these changes play a major role in the pathophysiology of asthma.

Eosinophilic infiltration is a hallmark of this inflammatory activity. Histologic evaluations of the large airways may also reveal narrowing of lumina, bronchial and bronchiolar epithelial denudation, and mucus plugs. Other relevant findings can include epithelial desquamation and hyperplasia, goblet cell metaplasia, subbasement membrane thickening, smooth muscle hypertrophy or hyperplasia, and submucosal gland hypertrophy. In patients with severe asthma, the basement membrane may be significantly thickened. In terms of the small airways, pathologic study from the lungs of living patients is rarely undertaken, and therefore the histopathologic findings of asthma at the level of the distal airways and alveolated lung parenchyma remains largely unknown.

Asthma is treated using a stepwise approach. As directed for pediatric patients younger than 5 years, the patient in this case may be provided with an as-needed inhaled short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) and should be followed up every 2-6 weeks while gaining control of her symptoms.