User login

Daily Recap 6/17

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Comorbidities increase COVID-19 deaths by factor of 12

COVID-19 patients with an underlying condition are 6 times as likely to be hospitalized and 12 times as likely to die, compared with those who have no such condition, according to the CDC.

The most frequently reported underlying conditions were cardiovascular disease (32%), diabetes (30%), chronic lung disease (18%), and renal disease (7.6%), and there were no significant differences between males and females.

The pandemic “continues to affect all populations and result in severe outcomes including death,” noted the CDC, emphasizing “the continued need for community mitigation strategies, especially for vulnerable populations, to slow COVID-19 transmission.” Read more.

Preventive services coalition recommends routine anxiety screening for women

Women and girls aged 13 years and older with no current diagnosis of anxiety should be screened routinely for anxiety, according to a new recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative.

The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in women in the United States is 40%, approximately twice that of men, and anxiety can be a manifestation of underlying issues including posttraumatic stress, sexual harassment, and assault.

“The WPSI based its rationale for anxiety screening on several considerations,” the researchers noted. “Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health disorders in women, and the problems created by untreated anxiety can impair function in all areas of a woman’s life.” Read more.

High-fat, high-sugar diet may promote adult acne

A diet higher in fat, sugar, and milk was associated with having acne in a cross-sectional study of approximately 24,000 adults in France.

Although acne patients may believe that eating certain foods exacerbates acne, data on the effects of nutrition on acne, including associations between acne and a high-glycemic diet, are limited and have produced conflicting results, noted investigators.

“The results of our study appear to support the hypothesis that the Western diet (rich in animal products and fatty and sugary foods) is associated with the presence of acne in adulthood,” the researchers concluded.

Population study supports migraine-dementia link

Preliminary results from a population-based cohort study support previous reports that migraine is a midlife risk factor for dementia later in life, but further determined that migraine with aura and frequent hospital contacts significantly increased dementia risk after age 60 years, according to results from a Danish registry presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The preliminary findings revealed that the median age at diagnosis was 49 years and about 70% of the migraine population were women. “There was a 50% higher dementia rate in individuals who had any migraine diagnosis,” Dr. Islamoska said.

“To the best of our knowledge, no previous national register–based studies have investigated the risk of dementia among individuals who suffer from migraine with aura,” Dr. Sabrina Islamoska said.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Comorbidities increase COVID-19 deaths by factor of 12

COVID-19 patients with an underlying condition are 6 times as likely to be hospitalized and 12 times as likely to die, compared with those who have no such condition, according to the CDC.

The most frequently reported underlying conditions were cardiovascular disease (32%), diabetes (30%), chronic lung disease (18%), and renal disease (7.6%), and there were no significant differences between males and females.

The pandemic “continues to affect all populations and result in severe outcomes including death,” noted the CDC, emphasizing “the continued need for community mitigation strategies, especially for vulnerable populations, to slow COVID-19 transmission.” Read more.

Preventive services coalition recommends routine anxiety screening for women

Women and girls aged 13 years and older with no current diagnosis of anxiety should be screened routinely for anxiety, according to a new recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative.

The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in women in the United States is 40%, approximately twice that of men, and anxiety can be a manifestation of underlying issues including posttraumatic stress, sexual harassment, and assault.

“The WPSI based its rationale for anxiety screening on several considerations,” the researchers noted. “Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health disorders in women, and the problems created by untreated anxiety can impair function in all areas of a woman’s life.” Read more.

High-fat, high-sugar diet may promote adult acne

A diet higher in fat, sugar, and milk was associated with having acne in a cross-sectional study of approximately 24,000 adults in France.

Although acne patients may believe that eating certain foods exacerbates acne, data on the effects of nutrition on acne, including associations between acne and a high-glycemic diet, are limited and have produced conflicting results, noted investigators.

“The results of our study appear to support the hypothesis that the Western diet (rich in animal products and fatty and sugary foods) is associated with the presence of acne in adulthood,” the researchers concluded.

Population study supports migraine-dementia link

Preliminary results from a population-based cohort study support previous reports that migraine is a midlife risk factor for dementia later in life, but further determined that migraine with aura and frequent hospital contacts significantly increased dementia risk after age 60 years, according to results from a Danish registry presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The preliminary findings revealed that the median age at diagnosis was 49 years and about 70% of the migraine population were women. “There was a 50% higher dementia rate in individuals who had any migraine diagnosis,” Dr. Islamoska said.

“To the best of our knowledge, no previous national register–based studies have investigated the risk of dementia among individuals who suffer from migraine with aura,” Dr. Sabrina Islamoska said.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Comorbidities increase COVID-19 deaths by factor of 12

COVID-19 patients with an underlying condition are 6 times as likely to be hospitalized and 12 times as likely to die, compared with those who have no such condition, according to the CDC.

The most frequently reported underlying conditions were cardiovascular disease (32%), diabetes (30%), chronic lung disease (18%), and renal disease (7.6%), and there were no significant differences between males and females.

The pandemic “continues to affect all populations and result in severe outcomes including death,” noted the CDC, emphasizing “the continued need for community mitigation strategies, especially for vulnerable populations, to slow COVID-19 transmission.” Read more.

Preventive services coalition recommends routine anxiety screening for women

Women and girls aged 13 years and older with no current diagnosis of anxiety should be screened routinely for anxiety, according to a new recommendation from the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative.

The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in women in the United States is 40%, approximately twice that of men, and anxiety can be a manifestation of underlying issues including posttraumatic stress, sexual harassment, and assault.

“The WPSI based its rationale for anxiety screening on several considerations,” the researchers noted. “Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health disorders in women, and the problems created by untreated anxiety can impair function in all areas of a woman’s life.” Read more.

High-fat, high-sugar diet may promote adult acne

A diet higher in fat, sugar, and milk was associated with having acne in a cross-sectional study of approximately 24,000 adults in France.

Although acne patients may believe that eating certain foods exacerbates acne, data on the effects of nutrition on acne, including associations between acne and a high-glycemic diet, are limited and have produced conflicting results, noted investigators.

“The results of our study appear to support the hypothesis that the Western diet (rich in animal products and fatty and sugary foods) is associated with the presence of acne in adulthood,” the researchers concluded.

Population study supports migraine-dementia link

Preliminary results from a population-based cohort study support previous reports that migraine is a midlife risk factor for dementia later in life, but further determined that migraine with aura and frequent hospital contacts significantly increased dementia risk after age 60 years, according to results from a Danish registry presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The preliminary findings revealed that the median age at diagnosis was 49 years and about 70% of the migraine population were women. “There was a 50% higher dementia rate in individuals who had any migraine diagnosis,” Dr. Islamoska said.

“To the best of our knowledge, no previous national register–based studies have investigated the risk of dementia among individuals who suffer from migraine with aura,” Dr. Sabrina Islamoska said.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Getting unstuck: Helping patients with behavior change

Kyle is a 14-year-old cisgender male who just moved to your town. At his first well-check, his single father brings him in reluctantly, stating, “We’ve never liked doctors.” Kyle has a history of asthma and obesity that have been relatively unchanged over time. He is an average student, an avid gamer, and seems somewhat shy. Privately he admits to occasional cannabis use. His father has no concerns, lamenting, “He’s always been pretty healthy for a fat kid.” Next patient?

Of course there is a lot to work with here. You might be concerned with Kyle’s asthma; his weight, sedentary nature, and body image; the criticism from his father and concerns about self-esteem; the possibility of anxiety in relation to his shyness; and the health effects of his cannabis use. In the end, recommendations for behavior change seem likely. These might take the form of tips on exercise, nutrition, substance use, study habits, parenting, social activities, or mental health support; the literature on behavior change would suggest that any success will be predicated on trust. How can we learn from someone we do not trust?1

To build trust is no easy task, and yet is perhaps the foundation on which the entire clinical relationship rests. Guidance from decades of evidence supporting the use of motivational interviewing2 suggests that the process of building rapport can be neatly summed up in an acronym as PACE. This represents Partnership, Acceptance, Compassion, and Evocation. Almost too clichéd to repeat, the most powerful change agent is the person making the change. In the setting of pediatric health care, we sometimes lean on caregivers to initiate or promote change because they are an intimate part of the patient’s microsystem, and thus moving one gear (the parents) inevitably shifts something in connected gears (the children).

So Partnership is centered on the patient, but inclusive of any important person in the patient’s sphere. In a family-based approach, this might show up as leveraging Kyle’s father’s motivation for behavior change by having the father start an exercise routine. This role models behavior change, shifts the home environment around the behavior, and builds empathy in the parent for the inherent challenges of change processes.

Acceptance can be distilled into knowing that the patient and family are doing the best they can. This does not preclude the possibility of change, but it seats this possibility in an attitude of assumed adequacy. There is nothing wrong with the patient, nothing to be fixed, just the possibility for change.

Similarly, Compassion takes a nonjudgmental viewpoint. With the stance of “this could happen to anybody,” the patient can feel responsible without feeling blamed. Noting the patient’s suffering without blame allows the clinician to be motivated not just to empathize, but to help.

And from this basis of compassionate partnership, the work of Evocation begins. What is happening in the patient’s life and relationships? What are their own goals and values? Where are the discrepancies between what the patient wants and what the patient does? For teenagers, this often brings into conflict developmentally appropriate wishes for autonomy – wanting to drive or get a car or stay out later or have more privacy – with developmentally typical challenges regarding responsibility.3 For example:

Clinician: “You want to use the car, and your parents want you to pay for the gas, but you’re out of money from buying weed. I see how you’re stuck.”

Teen: “Yeah, they really need to give me more allowance. It’s not like we’re living in the 1990s anymore!”

Clinician: “So you could ask for more allowance to get more money for gas. Any other ideas?”

Teen: “I could give up smoking pot and just be miserable all the time.”

Clinician: “Yeah, that sounds too difficult right now; if anything it sounds like you’d like to smoke more pot if you had more money.”

Teen: “Nah, I’m not that hooked on it. ... I could probably smoke a bit less each week and save some gas money.”

The PACE acronym also serves as a reminder of the patience required to grow connection where none has previously existed – pace yourself. Here are some skills-based tips to foster the spirit of motivational interviewing to help balance patience with the time frame of a pediatric check-in. The OARS skills represent the fundamental building blocks of motivational interviewing in practice. Taking the case of Kyle as an example, an Open-Ended Question makes space for the child or parent to express their views with less interviewer bias. Reflections expand this space by underscoring and, in the case of complex Reflections, adding some nuance to what the patient has to say.

Clinician: “How do you feel about your body?”

Teen: “Well, I’m fat. Nobody really wants to be fat. It sucks. But what can I do?”

Clinician: “You feel fat and kind of hopeless.”

Teen: “Yeah, I know you’re going to tell me to go on a diet and start exercising. Doesn’t work. My dad says I was born fat; I guess I’m going to stay that way.”

Clinician: “Sounds like you and your dad can get down on you for your weight. That must feel terrible.”

Teen: “Ah, it’s not that bad. I’m kind of used to it. Fat kid at home, fat kid at school.”

Affirmations are statements focusing on positive actions or attributes of the patient. They tend to build rapport by demonstrating that the clinician sees the strengths of the patient, not just the problems.

Clinician: “I’m pretty impressed that you’re able to show up here and talk about this. It can’t be easy when it sounds like your family and friends have put you down so much that you’re even putting yourself down about your body.”

Teen: “I didn’t really want to come, but then I thought, maybe this new doctor will have some new ideas. I actually want to do something about it, I just don’t know if anything will help. Plus my dad said if I showed up, we could go to McDonald’s afterward.”

Summaries are multipurpose. They demonstrate that you have been listening closely, which builds rapport. They provide a chance to put information together so that both clinician and patient can reflect on the sum of the data and notice what may be missing. And they provide a pause to consider where to go next.

Clinician: “So if I’m getting it right, you’ve been worried about your weight for a long time now. Your dad and your friends give you a hard time about it, which makes you feel down and hopeless, but somehow you stay brave and keep trying to figure it out. You feel ready to do something, you just don’t know what, and you were hoping maybe coming here could give you a place to work on your health. Does that sound about right?”

Teen: “I think that’s pretty much it. Plus the McDonald’s.”

Clinician: “Right, that’s important too – we have to consider your motivation! I wonder if we could talk about this more at our next visit – would that be alright?”

Offices with additional resources might be able to offer some of those as well, if timing seems appropriate; for example, referral to a wellness coach or social worker or nutritionist could be helpful int his case. With the spirit of PACE and the skills of OARS, you can be well on your way to fostering behavior changes that could last a lifetime! Check out the resources from the American Academy of Pediatrics with video and narrative demonstrations of motivational interviewing in pediatrics.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center and the university’s Robert Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. He reported no relevant disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “Engagement and disengagement,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

2. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “The spirit of motivational interviewing,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

3. Naar S, Suarez M. “Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A brief review of development,” in “Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults” (New York: Guilford, 2011).

Kyle is a 14-year-old cisgender male who just moved to your town. At his first well-check, his single father brings him in reluctantly, stating, “We’ve never liked doctors.” Kyle has a history of asthma and obesity that have been relatively unchanged over time. He is an average student, an avid gamer, and seems somewhat shy. Privately he admits to occasional cannabis use. His father has no concerns, lamenting, “He’s always been pretty healthy for a fat kid.” Next patient?

Of course there is a lot to work with here. You might be concerned with Kyle’s asthma; his weight, sedentary nature, and body image; the criticism from his father and concerns about self-esteem; the possibility of anxiety in relation to his shyness; and the health effects of his cannabis use. In the end, recommendations for behavior change seem likely. These might take the form of tips on exercise, nutrition, substance use, study habits, parenting, social activities, or mental health support; the literature on behavior change would suggest that any success will be predicated on trust. How can we learn from someone we do not trust?1

To build trust is no easy task, and yet is perhaps the foundation on which the entire clinical relationship rests. Guidance from decades of evidence supporting the use of motivational interviewing2 suggests that the process of building rapport can be neatly summed up in an acronym as PACE. This represents Partnership, Acceptance, Compassion, and Evocation. Almost too clichéd to repeat, the most powerful change agent is the person making the change. In the setting of pediatric health care, we sometimes lean on caregivers to initiate or promote change because they are an intimate part of the patient’s microsystem, and thus moving one gear (the parents) inevitably shifts something in connected gears (the children).

So Partnership is centered on the patient, but inclusive of any important person in the patient’s sphere. In a family-based approach, this might show up as leveraging Kyle’s father’s motivation for behavior change by having the father start an exercise routine. This role models behavior change, shifts the home environment around the behavior, and builds empathy in the parent for the inherent challenges of change processes.

Acceptance can be distilled into knowing that the patient and family are doing the best they can. This does not preclude the possibility of change, but it seats this possibility in an attitude of assumed adequacy. There is nothing wrong with the patient, nothing to be fixed, just the possibility for change.

Similarly, Compassion takes a nonjudgmental viewpoint. With the stance of “this could happen to anybody,” the patient can feel responsible without feeling blamed. Noting the patient’s suffering without blame allows the clinician to be motivated not just to empathize, but to help.

And from this basis of compassionate partnership, the work of Evocation begins. What is happening in the patient’s life and relationships? What are their own goals and values? Where are the discrepancies between what the patient wants and what the patient does? For teenagers, this often brings into conflict developmentally appropriate wishes for autonomy – wanting to drive or get a car or stay out later or have more privacy – with developmentally typical challenges regarding responsibility.3 For example:

Clinician: “You want to use the car, and your parents want you to pay for the gas, but you’re out of money from buying weed. I see how you’re stuck.”

Teen: “Yeah, they really need to give me more allowance. It’s not like we’re living in the 1990s anymore!”

Clinician: “So you could ask for more allowance to get more money for gas. Any other ideas?”

Teen: “I could give up smoking pot and just be miserable all the time.”

Clinician: “Yeah, that sounds too difficult right now; if anything it sounds like you’d like to smoke more pot if you had more money.”

Teen: “Nah, I’m not that hooked on it. ... I could probably smoke a bit less each week and save some gas money.”

The PACE acronym also serves as a reminder of the patience required to grow connection where none has previously existed – pace yourself. Here are some skills-based tips to foster the spirit of motivational interviewing to help balance patience with the time frame of a pediatric check-in. The OARS skills represent the fundamental building blocks of motivational interviewing in practice. Taking the case of Kyle as an example, an Open-Ended Question makes space for the child or parent to express their views with less interviewer bias. Reflections expand this space by underscoring and, in the case of complex Reflections, adding some nuance to what the patient has to say.

Clinician: “How do you feel about your body?”

Teen: “Well, I’m fat. Nobody really wants to be fat. It sucks. But what can I do?”

Clinician: “You feel fat and kind of hopeless.”

Teen: “Yeah, I know you’re going to tell me to go on a diet and start exercising. Doesn’t work. My dad says I was born fat; I guess I’m going to stay that way.”

Clinician: “Sounds like you and your dad can get down on you for your weight. That must feel terrible.”

Teen: “Ah, it’s not that bad. I’m kind of used to it. Fat kid at home, fat kid at school.”

Affirmations are statements focusing on positive actions or attributes of the patient. They tend to build rapport by demonstrating that the clinician sees the strengths of the patient, not just the problems.

Clinician: “I’m pretty impressed that you’re able to show up here and talk about this. It can’t be easy when it sounds like your family and friends have put you down so much that you’re even putting yourself down about your body.”

Teen: “I didn’t really want to come, but then I thought, maybe this new doctor will have some new ideas. I actually want to do something about it, I just don’t know if anything will help. Plus my dad said if I showed up, we could go to McDonald’s afterward.”

Summaries are multipurpose. They demonstrate that you have been listening closely, which builds rapport. They provide a chance to put information together so that both clinician and patient can reflect on the sum of the data and notice what may be missing. And they provide a pause to consider where to go next.

Clinician: “So if I’m getting it right, you’ve been worried about your weight for a long time now. Your dad and your friends give you a hard time about it, which makes you feel down and hopeless, but somehow you stay brave and keep trying to figure it out. You feel ready to do something, you just don’t know what, and you were hoping maybe coming here could give you a place to work on your health. Does that sound about right?”

Teen: “I think that’s pretty much it. Plus the McDonald’s.”

Clinician: “Right, that’s important too – we have to consider your motivation! I wonder if we could talk about this more at our next visit – would that be alright?”

Offices with additional resources might be able to offer some of those as well, if timing seems appropriate; for example, referral to a wellness coach or social worker or nutritionist could be helpful int his case. With the spirit of PACE and the skills of OARS, you can be well on your way to fostering behavior changes that could last a lifetime! Check out the resources from the American Academy of Pediatrics with video and narrative demonstrations of motivational interviewing in pediatrics.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center and the university’s Robert Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. He reported no relevant disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “Engagement and disengagement,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

2. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “The spirit of motivational interviewing,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

3. Naar S, Suarez M. “Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A brief review of development,” in “Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults” (New York: Guilford, 2011).

Kyle is a 14-year-old cisgender male who just moved to your town. At his first well-check, his single father brings him in reluctantly, stating, “We’ve never liked doctors.” Kyle has a history of asthma and obesity that have been relatively unchanged over time. He is an average student, an avid gamer, and seems somewhat shy. Privately he admits to occasional cannabis use. His father has no concerns, lamenting, “He’s always been pretty healthy for a fat kid.” Next patient?

Of course there is a lot to work with here. You might be concerned with Kyle’s asthma; his weight, sedentary nature, and body image; the criticism from his father and concerns about self-esteem; the possibility of anxiety in relation to his shyness; and the health effects of his cannabis use. In the end, recommendations for behavior change seem likely. These might take the form of tips on exercise, nutrition, substance use, study habits, parenting, social activities, or mental health support; the literature on behavior change would suggest that any success will be predicated on trust. How can we learn from someone we do not trust?1

To build trust is no easy task, and yet is perhaps the foundation on which the entire clinical relationship rests. Guidance from decades of evidence supporting the use of motivational interviewing2 suggests that the process of building rapport can be neatly summed up in an acronym as PACE. This represents Partnership, Acceptance, Compassion, and Evocation. Almost too clichéd to repeat, the most powerful change agent is the person making the change. In the setting of pediatric health care, we sometimes lean on caregivers to initiate or promote change because they are an intimate part of the patient’s microsystem, and thus moving one gear (the parents) inevitably shifts something in connected gears (the children).

So Partnership is centered on the patient, but inclusive of any important person in the patient’s sphere. In a family-based approach, this might show up as leveraging Kyle’s father’s motivation for behavior change by having the father start an exercise routine. This role models behavior change, shifts the home environment around the behavior, and builds empathy in the parent for the inherent challenges of change processes.

Acceptance can be distilled into knowing that the patient and family are doing the best they can. This does not preclude the possibility of change, but it seats this possibility in an attitude of assumed adequacy. There is nothing wrong with the patient, nothing to be fixed, just the possibility for change.

Similarly, Compassion takes a nonjudgmental viewpoint. With the stance of “this could happen to anybody,” the patient can feel responsible without feeling blamed. Noting the patient’s suffering without blame allows the clinician to be motivated not just to empathize, but to help.

And from this basis of compassionate partnership, the work of Evocation begins. What is happening in the patient’s life and relationships? What are their own goals and values? Where are the discrepancies between what the patient wants and what the patient does? For teenagers, this often brings into conflict developmentally appropriate wishes for autonomy – wanting to drive or get a car or stay out later or have more privacy – with developmentally typical challenges regarding responsibility.3 For example:

Clinician: “You want to use the car, and your parents want you to pay for the gas, but you’re out of money from buying weed. I see how you’re stuck.”

Teen: “Yeah, they really need to give me more allowance. It’s not like we’re living in the 1990s anymore!”

Clinician: “So you could ask for more allowance to get more money for gas. Any other ideas?”

Teen: “I could give up smoking pot and just be miserable all the time.”

Clinician: “Yeah, that sounds too difficult right now; if anything it sounds like you’d like to smoke more pot if you had more money.”

Teen: “Nah, I’m not that hooked on it. ... I could probably smoke a bit less each week and save some gas money.”

The PACE acronym also serves as a reminder of the patience required to grow connection where none has previously existed – pace yourself. Here are some skills-based tips to foster the spirit of motivational interviewing to help balance patience with the time frame of a pediatric check-in. The OARS skills represent the fundamental building blocks of motivational interviewing in practice. Taking the case of Kyle as an example, an Open-Ended Question makes space for the child or parent to express their views with less interviewer bias. Reflections expand this space by underscoring and, in the case of complex Reflections, adding some nuance to what the patient has to say.

Clinician: “How do you feel about your body?”

Teen: “Well, I’m fat. Nobody really wants to be fat. It sucks. But what can I do?”

Clinician: “You feel fat and kind of hopeless.”

Teen: “Yeah, I know you’re going to tell me to go on a diet and start exercising. Doesn’t work. My dad says I was born fat; I guess I’m going to stay that way.”

Clinician: “Sounds like you and your dad can get down on you for your weight. That must feel terrible.”

Teen: “Ah, it’s not that bad. I’m kind of used to it. Fat kid at home, fat kid at school.”

Affirmations are statements focusing on positive actions or attributes of the patient. They tend to build rapport by demonstrating that the clinician sees the strengths of the patient, not just the problems.

Clinician: “I’m pretty impressed that you’re able to show up here and talk about this. It can’t be easy when it sounds like your family and friends have put you down so much that you’re even putting yourself down about your body.”

Teen: “I didn’t really want to come, but then I thought, maybe this new doctor will have some new ideas. I actually want to do something about it, I just don’t know if anything will help. Plus my dad said if I showed up, we could go to McDonald’s afterward.”

Summaries are multipurpose. They demonstrate that you have been listening closely, which builds rapport. They provide a chance to put information together so that both clinician and patient can reflect on the sum of the data and notice what may be missing. And they provide a pause to consider where to go next.

Clinician: “So if I’m getting it right, you’ve been worried about your weight for a long time now. Your dad and your friends give you a hard time about it, which makes you feel down and hopeless, but somehow you stay brave and keep trying to figure it out. You feel ready to do something, you just don’t know what, and you were hoping maybe coming here could give you a place to work on your health. Does that sound about right?”

Teen: “I think that’s pretty much it. Plus the McDonald’s.”

Clinician: “Right, that’s important too – we have to consider your motivation! I wonder if we could talk about this more at our next visit – would that be alright?”

Offices with additional resources might be able to offer some of those as well, if timing seems appropriate; for example, referral to a wellness coach or social worker or nutritionist could be helpful int his case. With the spirit of PACE and the skills of OARS, you can be well on your way to fostering behavior changes that could last a lifetime! Check out the resources from the American Academy of Pediatrics with video and narrative demonstrations of motivational interviewing in pediatrics.

Dr. Rosenfeld is assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Medical Center and the university’s Robert Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. He reported no relevant disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “Engagement and disengagement,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

2. Miller WR, Rollnick S. “The spirit of motivational interviewing,” in “Motivational interviewing: Helping people change,” 3rd ed. (New York: Guilford, 2013).

3. Naar S, Suarez M. “Adolescence and emerging adulthood: A brief review of development,” in “Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults” (New York: Guilford, 2011).

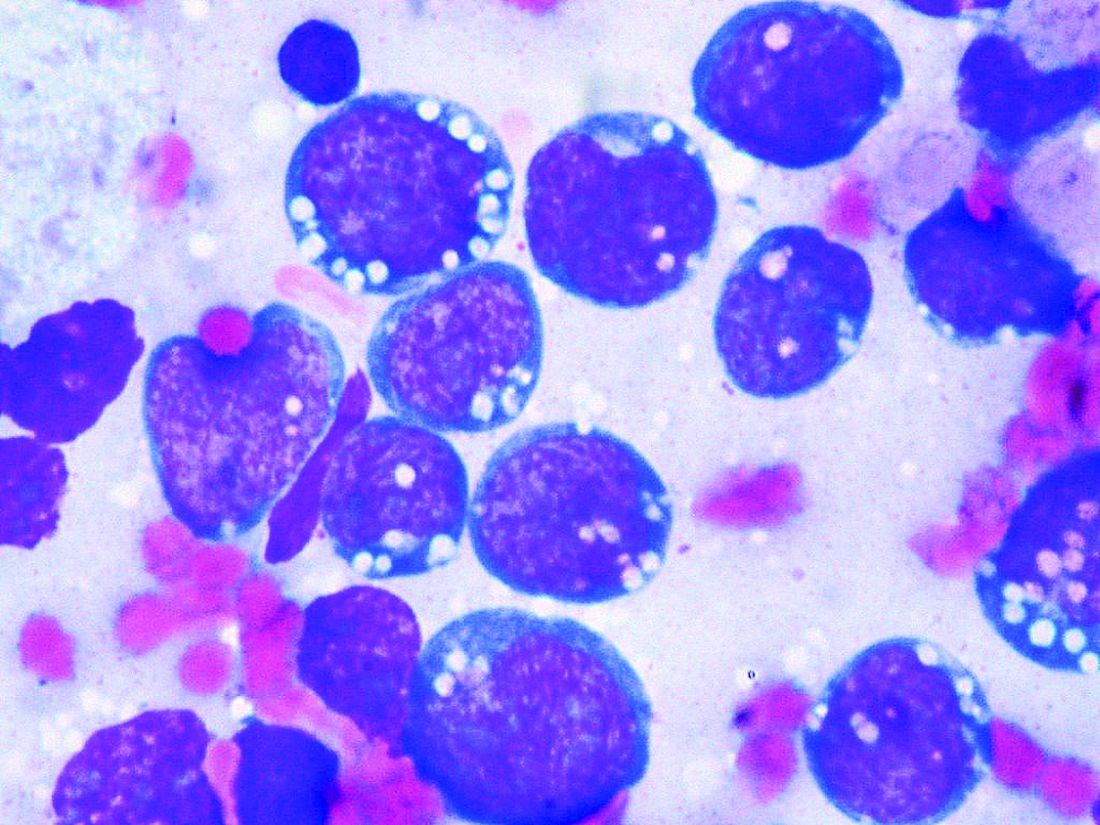

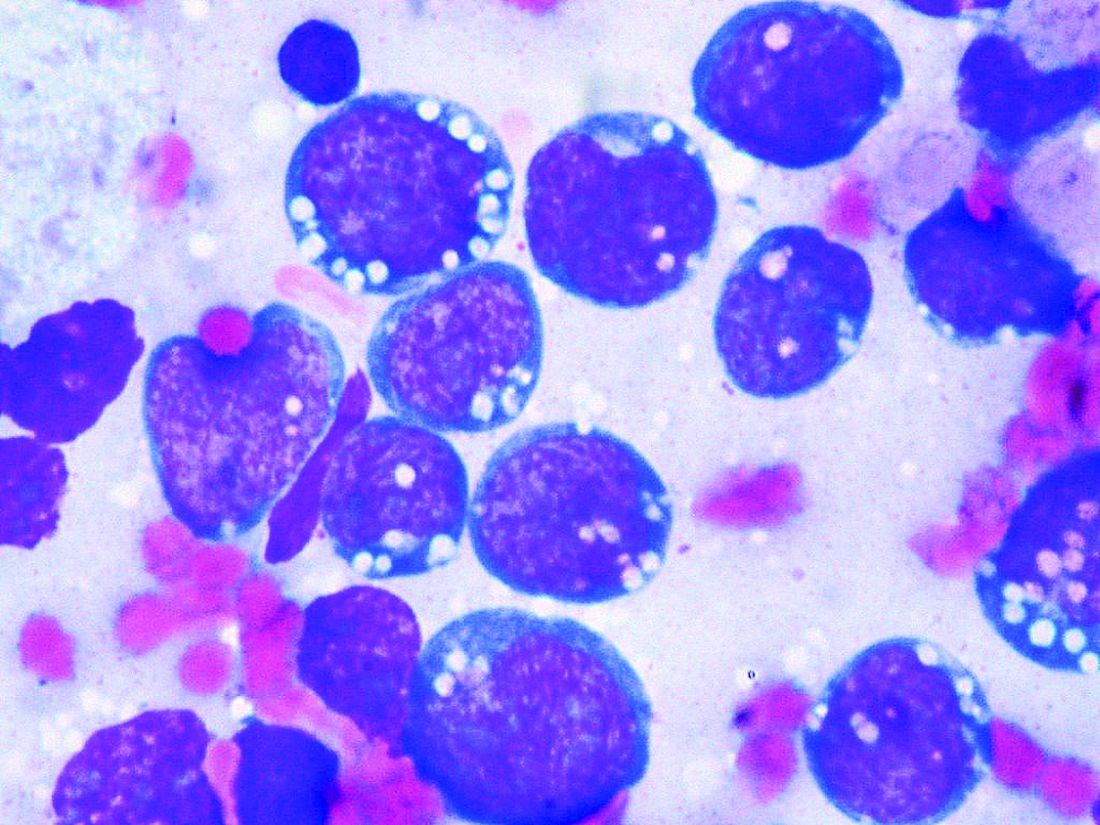

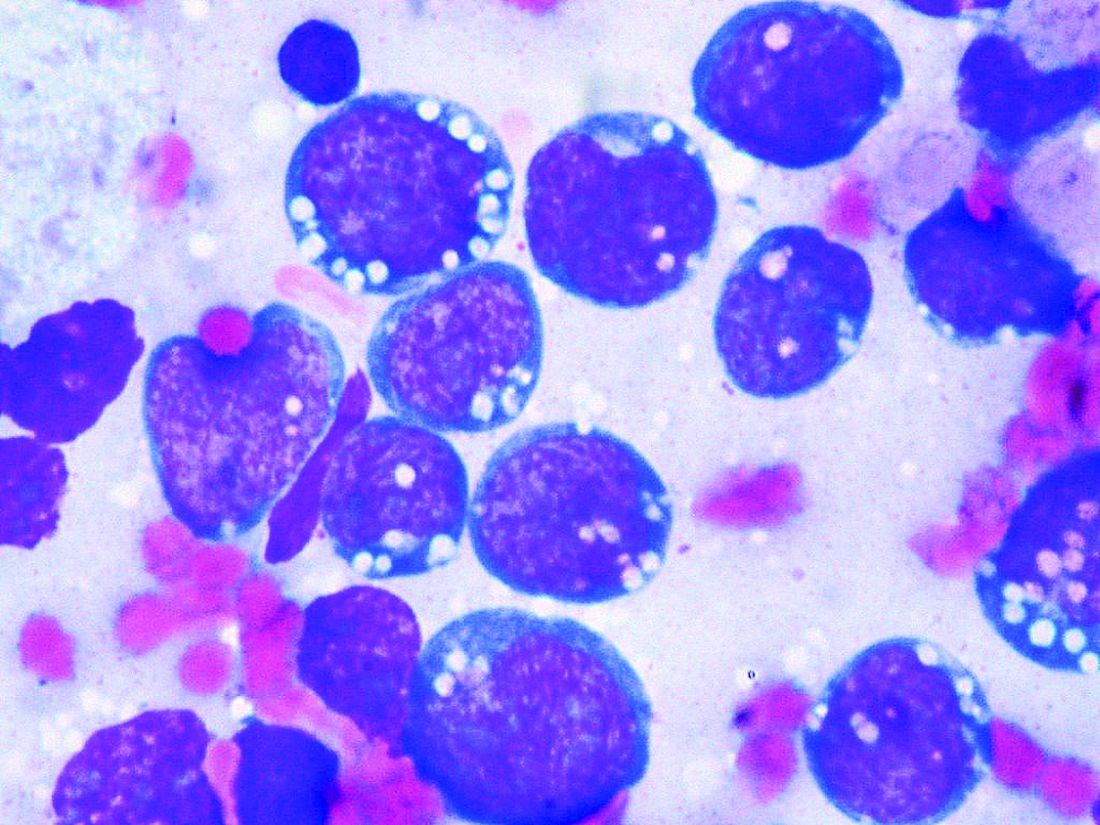

New EPOCH for adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma

Adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma can achieve equally sound survival outcomes with dose-adjusted chemotherapy versus high-intensity regimens, but can do so while avoiding the severe toxicities, U.S. study data shows.

Although Burkitt lymphoma is the most common B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children, it accounts for only 1% to 2% of adult lymphoma cases.

Highly dose-intensive chemotherapy regimens, developed for children and young adults, have rendered the disease curable. But older patients in particular, and patients with comorbidities such as HIV, can suffer severe adverse effects, as well as late sequelae like second malignancies.

Mark Roschewski, MD, from the lymphoid malignancies branch at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues therefore examined whether a dose-adjusted regimen would maintain outcomes while reducing toxicities.

Tailoring treatment with etoposide, doxorubicin, and vincristine with prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (EPOCH-R) to whether patients had high- or low-risk disease, they achieved 4-year survival rates of higher than 85%.

The research, published by the Journal of Clinical Oncology, also showed that patients taking the regimen, which was well tolerated, had low rates of relapse in the central nervous system.

The team reports that their results with the dose-adjusted regimen “significantly improve on the complexity, cost, and toxicity profile of other regimens,” also highlighting that it is administered on an outpatient basis.

As the outcomes also “compare favorably” with those with high intensity regimens, they say the findings “support our treatment strategies to ameliorate toxicity while maintaining efficacy.”

Importantly, they suggest highly dose-intensive chemotherapy is unnecessary for cure, and carefully defined low-risk patients may be treated with limited chemotherapy.

Dr. Roschewski said in an interview that, in patients aged 40 years and older, dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is “probably the preferred choice,” despite its “weakness” in controlling the disease in patients with active CNS involvement.

However, the “real question” is what to use in younger patients, Dr. Roschewski said, as the “unknown” is whether the additional magnitude of a high-intensity regimen that “gets into the CNS” outweighs the risk of toxicities.

“What was important about our study,” he said, was that patients with CNS involvement “did the worst but it was equally split among patients that died of toxicity and patients that progressed.”

In other words, each choice increases one risk while decreasing another. “So I would have to have that discussion with the patient, and individual patient decisions are typically based on the details,” said Dr. Roschewski.

One issue, however, that could limit the adoption of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is that, without a randomized study comparing it directly with a high-intensity regimen, clinicians may to stick to what they know.

Dr. Roschewski said that “this is particularly true of more experienced clinicians.”

“They’re less likely, I think, to adopt something else outside of a randomized study because our natural inclination with this disease has always been dose intensity is critical. ... This is a dogma, and to shift from that probably does require a higher level of evidence, at least for some practitioners,” he explained.

Further study details

Following a pilot study of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R in 30 adult patients in which the authors say the regimen showed “high efficacy,” they enrolled 113 patients with untreated Burkitt lymphoma at 22 centers between June 2010 and May 2017.

The patients were divided into low-risk and high-risk categories, with low-risk defined as stage 1 or 2 disease, normal lactate dehydrogenase levels, ECOG performance status ≤ 1, and no tumor mass ≥ 7 cm.

High-risk patients were given six cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (with rituximab on day 1 only) along with CNS prophylaxis or active therapy with intrathecal methotrexate.

In contrast, low-risk patients were given two cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, with rituximab on days 1 and 5, followed by positron emission tomography.

If that was negative, the patients had one additional treatment cycle and no CNS prophylaxis, but if it was positive, they were given four additional cycles, plus intrathecal methotrexate.

Of the 113 patients enrolled, 79% were male, median age was 49 years, and 62% were aged at least 40 years, including 26% aged at least 60 years.

The team determined that 13% of the patients were of low risk, 87% were high risk, and 11% had cerebrospinal fluid involvement. One-quarter (24.7%) were HIV positive, with a median CD4+ T-cell count of 268 cells/mm3.

The majority (87%) of low-risk patients received three treatment cycles, and 82% of high-risk patents were administered six treatment cycles.

Over a median follow-up of 58.7 months (4.9 years), the 4-year event-free survival (EFS) rate across the whole cohort was 84.5% and overall survival was 87%.

At the time of analysis, all low-risk patients were in remission; among high-risk patients, the 4-year EFS was 82.1% and overall survival was 84.9%.

The team reports that treatment was equally effective across age groups, and irrespective of HIV status and International Prognostic Index risk group.

Only 2% of high-risk patients with no pretreatment evidence of CNS involvement had relapses in the brain parenchyma. Just over half (55%) of patients with cerebrospinal fluid involvement at presentation experienced disease progression or died.

Five patients died of treatment-related toxicity. Grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia occurred during 17% of cycles, and febrile neutropenia was seen during 16%. Tumor lysis syndrome was rare, occurring in 5% of patients.

Next, the researchers are planning on focusing on CNS disease, looking at EPOCH-R as the backbone and adding intrathecal methotrexate and an additional targeted agent with known CNS penetration.

Dr. Roschewski said that is “a very attractive strategy and ... we will initiate enrollment in that study probably in the next couple of months here at the NCI,” he added, noting that it will be an early phase 1 study.

Another issue he identified that “doesn’t get spoken about quite as much but I do think is important is potentially working on supportive care guidelines for how we manage these patients.” Dr. Roschewski explained, “One of the things you see over and over in these Burkitt lymphoma studies is that some patients don’t make it through therapy because they’re so sick at the beginning, and they have certain risks.

“I think simply improving that type of care, independent of what regimen is used, can potentially improve the outcomes across patient groups.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, AIDS Malignancy Consortium, and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Lymphoid Malignancies Branch. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma can achieve equally sound survival outcomes with dose-adjusted chemotherapy versus high-intensity regimens, but can do so while avoiding the severe toxicities, U.S. study data shows.

Although Burkitt lymphoma is the most common B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children, it accounts for only 1% to 2% of adult lymphoma cases.

Highly dose-intensive chemotherapy regimens, developed for children and young adults, have rendered the disease curable. But older patients in particular, and patients with comorbidities such as HIV, can suffer severe adverse effects, as well as late sequelae like second malignancies.

Mark Roschewski, MD, from the lymphoid malignancies branch at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues therefore examined whether a dose-adjusted regimen would maintain outcomes while reducing toxicities.

Tailoring treatment with etoposide, doxorubicin, and vincristine with prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (EPOCH-R) to whether patients had high- or low-risk disease, they achieved 4-year survival rates of higher than 85%.

The research, published by the Journal of Clinical Oncology, also showed that patients taking the regimen, which was well tolerated, had low rates of relapse in the central nervous system.

The team reports that their results with the dose-adjusted regimen “significantly improve on the complexity, cost, and toxicity profile of other regimens,” also highlighting that it is administered on an outpatient basis.

As the outcomes also “compare favorably” with those with high intensity regimens, they say the findings “support our treatment strategies to ameliorate toxicity while maintaining efficacy.”

Importantly, they suggest highly dose-intensive chemotherapy is unnecessary for cure, and carefully defined low-risk patients may be treated with limited chemotherapy.

Dr. Roschewski said in an interview that, in patients aged 40 years and older, dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is “probably the preferred choice,” despite its “weakness” in controlling the disease in patients with active CNS involvement.

However, the “real question” is what to use in younger patients, Dr. Roschewski said, as the “unknown” is whether the additional magnitude of a high-intensity regimen that “gets into the CNS” outweighs the risk of toxicities.

“What was important about our study,” he said, was that patients with CNS involvement “did the worst but it was equally split among patients that died of toxicity and patients that progressed.”

In other words, each choice increases one risk while decreasing another. “So I would have to have that discussion with the patient, and individual patient decisions are typically based on the details,” said Dr. Roschewski.

One issue, however, that could limit the adoption of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is that, without a randomized study comparing it directly with a high-intensity regimen, clinicians may to stick to what they know.

Dr. Roschewski said that “this is particularly true of more experienced clinicians.”

“They’re less likely, I think, to adopt something else outside of a randomized study because our natural inclination with this disease has always been dose intensity is critical. ... This is a dogma, and to shift from that probably does require a higher level of evidence, at least for some practitioners,” he explained.

Further study details

Following a pilot study of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R in 30 adult patients in which the authors say the regimen showed “high efficacy,” they enrolled 113 patients with untreated Burkitt lymphoma at 22 centers between June 2010 and May 2017.

The patients were divided into low-risk and high-risk categories, with low-risk defined as stage 1 or 2 disease, normal lactate dehydrogenase levels, ECOG performance status ≤ 1, and no tumor mass ≥ 7 cm.

High-risk patients were given six cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (with rituximab on day 1 only) along with CNS prophylaxis or active therapy with intrathecal methotrexate.

In contrast, low-risk patients were given two cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, with rituximab on days 1 and 5, followed by positron emission tomography.

If that was negative, the patients had one additional treatment cycle and no CNS prophylaxis, but if it was positive, they were given four additional cycles, plus intrathecal methotrexate.

Of the 113 patients enrolled, 79% were male, median age was 49 years, and 62% were aged at least 40 years, including 26% aged at least 60 years.

The team determined that 13% of the patients were of low risk, 87% were high risk, and 11% had cerebrospinal fluid involvement. One-quarter (24.7%) were HIV positive, with a median CD4+ T-cell count of 268 cells/mm3.

The majority (87%) of low-risk patients received three treatment cycles, and 82% of high-risk patents were administered six treatment cycles.

Over a median follow-up of 58.7 months (4.9 years), the 4-year event-free survival (EFS) rate across the whole cohort was 84.5% and overall survival was 87%.

At the time of analysis, all low-risk patients were in remission; among high-risk patients, the 4-year EFS was 82.1% and overall survival was 84.9%.

The team reports that treatment was equally effective across age groups, and irrespective of HIV status and International Prognostic Index risk group.

Only 2% of high-risk patients with no pretreatment evidence of CNS involvement had relapses in the brain parenchyma. Just over half (55%) of patients with cerebrospinal fluid involvement at presentation experienced disease progression or died.

Five patients died of treatment-related toxicity. Grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia occurred during 17% of cycles, and febrile neutropenia was seen during 16%. Tumor lysis syndrome was rare, occurring in 5% of patients.

Next, the researchers are planning on focusing on CNS disease, looking at EPOCH-R as the backbone and adding intrathecal methotrexate and an additional targeted agent with known CNS penetration.

Dr. Roschewski said that is “a very attractive strategy and ... we will initiate enrollment in that study probably in the next couple of months here at the NCI,” he added, noting that it will be an early phase 1 study.

Another issue he identified that “doesn’t get spoken about quite as much but I do think is important is potentially working on supportive care guidelines for how we manage these patients.” Dr. Roschewski explained, “One of the things you see over and over in these Burkitt lymphoma studies is that some patients don’t make it through therapy because they’re so sick at the beginning, and they have certain risks.

“I think simply improving that type of care, independent of what regimen is used, can potentially improve the outcomes across patient groups.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, AIDS Malignancy Consortium, and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Lymphoid Malignancies Branch. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Adult patients with Burkitt lymphoma can achieve equally sound survival outcomes with dose-adjusted chemotherapy versus high-intensity regimens, but can do so while avoiding the severe toxicities, U.S. study data shows.

Although Burkitt lymphoma is the most common B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children, it accounts for only 1% to 2% of adult lymphoma cases.

Highly dose-intensive chemotherapy regimens, developed for children and young adults, have rendered the disease curable. But older patients in particular, and patients with comorbidities such as HIV, can suffer severe adverse effects, as well as late sequelae like second malignancies.

Mark Roschewski, MD, from the lymphoid malignancies branch at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues therefore examined whether a dose-adjusted regimen would maintain outcomes while reducing toxicities.

Tailoring treatment with etoposide, doxorubicin, and vincristine with prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (EPOCH-R) to whether patients had high- or low-risk disease, they achieved 4-year survival rates of higher than 85%.

The research, published by the Journal of Clinical Oncology, also showed that patients taking the regimen, which was well tolerated, had low rates of relapse in the central nervous system.

The team reports that their results with the dose-adjusted regimen “significantly improve on the complexity, cost, and toxicity profile of other regimens,” also highlighting that it is administered on an outpatient basis.

As the outcomes also “compare favorably” with those with high intensity regimens, they say the findings “support our treatment strategies to ameliorate toxicity while maintaining efficacy.”

Importantly, they suggest highly dose-intensive chemotherapy is unnecessary for cure, and carefully defined low-risk patients may be treated with limited chemotherapy.

Dr. Roschewski said in an interview that, in patients aged 40 years and older, dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is “probably the preferred choice,” despite its “weakness” in controlling the disease in patients with active CNS involvement.

However, the “real question” is what to use in younger patients, Dr. Roschewski said, as the “unknown” is whether the additional magnitude of a high-intensity regimen that “gets into the CNS” outweighs the risk of toxicities.

“What was important about our study,” he said, was that patients with CNS involvement “did the worst but it was equally split among patients that died of toxicity and patients that progressed.”

In other words, each choice increases one risk while decreasing another. “So I would have to have that discussion with the patient, and individual patient decisions are typically based on the details,” said Dr. Roschewski.

One issue, however, that could limit the adoption of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R is that, without a randomized study comparing it directly with a high-intensity regimen, clinicians may to stick to what they know.

Dr. Roschewski said that “this is particularly true of more experienced clinicians.”

“They’re less likely, I think, to adopt something else outside of a randomized study because our natural inclination with this disease has always been dose intensity is critical. ... This is a dogma, and to shift from that probably does require a higher level of evidence, at least for some practitioners,” he explained.

Further study details

Following a pilot study of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R in 30 adult patients in which the authors say the regimen showed “high efficacy,” they enrolled 113 patients with untreated Burkitt lymphoma at 22 centers between June 2010 and May 2017.

The patients were divided into low-risk and high-risk categories, with low-risk defined as stage 1 or 2 disease, normal lactate dehydrogenase levels, ECOG performance status ≤ 1, and no tumor mass ≥ 7 cm.

High-risk patients were given six cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (with rituximab on day 1 only) along with CNS prophylaxis or active therapy with intrathecal methotrexate.

In contrast, low-risk patients were given two cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, with rituximab on days 1 and 5, followed by positron emission tomography.

If that was negative, the patients had one additional treatment cycle and no CNS prophylaxis, but if it was positive, they were given four additional cycles, plus intrathecal methotrexate.

Of the 113 patients enrolled, 79% were male, median age was 49 years, and 62% were aged at least 40 years, including 26% aged at least 60 years.

The team determined that 13% of the patients were of low risk, 87% were high risk, and 11% had cerebrospinal fluid involvement. One-quarter (24.7%) were HIV positive, with a median CD4+ T-cell count of 268 cells/mm3.

The majority (87%) of low-risk patients received three treatment cycles, and 82% of high-risk patents were administered six treatment cycles.

Over a median follow-up of 58.7 months (4.9 years), the 4-year event-free survival (EFS) rate across the whole cohort was 84.5% and overall survival was 87%.

At the time of analysis, all low-risk patients were in remission; among high-risk patients, the 4-year EFS was 82.1% and overall survival was 84.9%.

The team reports that treatment was equally effective across age groups, and irrespective of HIV status and International Prognostic Index risk group.

Only 2% of high-risk patients with no pretreatment evidence of CNS involvement had relapses in the brain parenchyma. Just over half (55%) of patients with cerebrospinal fluid involvement at presentation experienced disease progression or died.

Five patients died of treatment-related toxicity. Grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia occurred during 17% of cycles, and febrile neutropenia was seen during 16%. Tumor lysis syndrome was rare, occurring in 5% of patients.

Next, the researchers are planning on focusing on CNS disease, looking at EPOCH-R as the backbone and adding intrathecal methotrexate and an additional targeted agent with known CNS penetration.

Dr. Roschewski said that is “a very attractive strategy and ... we will initiate enrollment in that study probably in the next couple of months here at the NCI,” he added, noting that it will be an early phase 1 study.

Another issue he identified that “doesn’t get spoken about quite as much but I do think is important is potentially working on supportive care guidelines for how we manage these patients.” Dr. Roschewski explained, “One of the things you see over and over in these Burkitt lymphoma studies is that some patients don’t make it through therapy because they’re so sick at the beginning, and they have certain risks.

“I think simply improving that type of care, independent of what regimen is used, can potentially improve the outcomes across patient groups.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, AIDS Malignancy Consortium, and the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Lymphoid Malignancies Branch. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Your diet may be aging you

Recent studies have shown a correlation between many dietary elements and skin diseases including acne, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis. and there is now evidence that the aging process can also be slowed with a healthy diet. Previous studies have shown that intake of vegetables, fish, and foods high in vitamin C, carotenoids, olive oil, and linoleic acid are associated with decreased wrinkles.

In a Dutch population-based cohort study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2019, Mekić et al. investigated the association between diet and facial wrinkles in an elderly population. Facial photographs were used to evaluate wrinkle severity and diet of the participants was assessed with the Food Frequency Questionnaire and adherence to the Dutch Healthy Diet Index (DHDI).

The DHDI is a measure of the ability to adhere to the Dutch Guidelines for a Healthy Diet. The guidelines recommend a daily intake in the diet of at least 200 g of vegetables daily; at least 200 g of fruit; 90 g of brown bread, wholemeal bread, or other whole-grain products; and at least 15 g of unsalted nuts. One serving of fish (preferably oily fish) per week and little to no dairy, alcohol, red meat, cooking fats, and sugar is also recommended.

The study revealed that better adherence to the DHDI was significantly associated with fewer wrinkles among women but not men. Women who ate more animal meat and fats and carbohydrates had more wrinkles than did those with a fruit-dominant diet.

Although other healthy behaviors such as exercise and alcohol are likely to play a role in confounding these data, UV exposure as a cause of wrinkling was accounted for, and in the study, increased outdoor exercise was associated with more wrinkles. Unhealthy food can induce oxidative stress, increased skin and gut inflammation, and glycation, which are some of the physiologic mechanisms suggested to increase wrinkle formation. In contrast, nutrients in fruits and vegetables stimulate collagen production and DNA repair and reduce oxidative stress on the skin.

Nutritional advice is largely rare in internal medicine, cardiology, and even endocrinology. We are developing better ways to assess and understand the way foods interact and cause inflammation of the gut and the body and skin. I highly recommend nutritional education be a part of our residency training programs and to make better guidelines on the prevention of skin disease and aging available for both practitioners and patients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Mekić S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 May;80(5):1358-1363.e2.

Purba MB et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(1):71‐80.

van Lee L et al. Nutr J. 2012 Jul 20;11:49.

Kromhout D et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Aug;70(8):869‐78.

Recent studies have shown a correlation between many dietary elements and skin diseases including acne, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis. and there is now evidence that the aging process can also be slowed with a healthy diet. Previous studies have shown that intake of vegetables, fish, and foods high in vitamin C, carotenoids, olive oil, and linoleic acid are associated with decreased wrinkles.

In a Dutch population-based cohort study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2019, Mekić et al. investigated the association between diet and facial wrinkles in an elderly population. Facial photographs were used to evaluate wrinkle severity and diet of the participants was assessed with the Food Frequency Questionnaire and adherence to the Dutch Healthy Diet Index (DHDI).

The DHDI is a measure of the ability to adhere to the Dutch Guidelines for a Healthy Diet. The guidelines recommend a daily intake in the diet of at least 200 g of vegetables daily; at least 200 g of fruit; 90 g of brown bread, wholemeal bread, or other whole-grain products; and at least 15 g of unsalted nuts. One serving of fish (preferably oily fish) per week and little to no dairy, alcohol, red meat, cooking fats, and sugar is also recommended.

The study revealed that better adherence to the DHDI was significantly associated with fewer wrinkles among women but not men. Women who ate more animal meat and fats and carbohydrates had more wrinkles than did those with a fruit-dominant diet.

Although other healthy behaviors such as exercise and alcohol are likely to play a role in confounding these data, UV exposure as a cause of wrinkling was accounted for, and in the study, increased outdoor exercise was associated with more wrinkles. Unhealthy food can induce oxidative stress, increased skin and gut inflammation, and glycation, which are some of the physiologic mechanisms suggested to increase wrinkle formation. In contrast, nutrients in fruits and vegetables stimulate collagen production and DNA repair and reduce oxidative stress on the skin.

Nutritional advice is largely rare in internal medicine, cardiology, and even endocrinology. We are developing better ways to assess and understand the way foods interact and cause inflammation of the gut and the body and skin. I highly recommend nutritional education be a part of our residency training programs and to make better guidelines on the prevention of skin disease and aging available for both practitioners and patients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Mekić S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 May;80(5):1358-1363.e2.

Purba MB et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(1):71‐80.

van Lee L et al. Nutr J. 2012 Jul 20;11:49.

Kromhout D et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Aug;70(8):869‐78.

Recent studies have shown a correlation between many dietary elements and skin diseases including acne, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis. and there is now evidence that the aging process can also be slowed with a healthy diet. Previous studies have shown that intake of vegetables, fish, and foods high in vitamin C, carotenoids, olive oil, and linoleic acid are associated with decreased wrinkles.

In a Dutch population-based cohort study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2019, Mekić et al. investigated the association between diet and facial wrinkles in an elderly population. Facial photographs were used to evaluate wrinkle severity and diet of the participants was assessed with the Food Frequency Questionnaire and adherence to the Dutch Healthy Diet Index (DHDI).

The DHDI is a measure of the ability to adhere to the Dutch Guidelines for a Healthy Diet. The guidelines recommend a daily intake in the diet of at least 200 g of vegetables daily; at least 200 g of fruit; 90 g of brown bread, wholemeal bread, or other whole-grain products; and at least 15 g of unsalted nuts. One serving of fish (preferably oily fish) per week and little to no dairy, alcohol, red meat, cooking fats, and sugar is also recommended.

The study revealed that better adherence to the DHDI was significantly associated with fewer wrinkles among women but not men. Women who ate more animal meat and fats and carbohydrates had more wrinkles than did those with a fruit-dominant diet.

Although other healthy behaviors such as exercise and alcohol are likely to play a role in confounding these data, UV exposure as a cause of wrinkling was accounted for, and in the study, increased outdoor exercise was associated with more wrinkles. Unhealthy food can induce oxidative stress, increased skin and gut inflammation, and glycation, which are some of the physiologic mechanisms suggested to increase wrinkle formation. In contrast, nutrients in fruits and vegetables stimulate collagen production and DNA repair and reduce oxidative stress on the skin.

Nutritional advice is largely rare in internal medicine, cardiology, and even endocrinology. We are developing better ways to assess and understand the way foods interact and cause inflammation of the gut and the body and skin. I highly recommend nutritional education be a part of our residency training programs and to make better guidelines on the prevention of skin disease and aging available for both practitioners and patients.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Mekić S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 May;80(5):1358-1363.e2.

Purba MB et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(1):71‐80.

van Lee L et al. Nutr J. 2012 Jul 20;11:49.

Kromhout D et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Aug;70(8):869‐78.

Dermatology News welcomes new advisory board member

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

at University Hospital Saint-Louis in Paris, in the inflammatory diseases outpatient clinic, where he treats patients with severe psoriasis and other inflammatory chronic skin diseases.

He is a member of several dermatology specialty organizations, including the Société Française de Dermatologie, the European Academy of Dermatology, as well as the American Academy of Dermatology. His research interests are in immunology and inflammatory diseases; he also has a passion for art and history.

Frequent hypoglycemic episodes raise cardiac event risk

Frequent hypoglycemic episodes were linked to a raised incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes in a recent retrospective study, suggesting certain hypoglycemia-associated diabetes drugs should be avoided, an investigator said.

Patients who had more than five hypoglycemic episodes per year had a 61% greater risk of cardiovascular (CV) events, compared with patients with less frequent episodes, according to results of the study.

Although there were fewer strokes among younger patients, the overall increase in cardiovascular event risk held up regardless of age group, according to investigator Aman Rajpal, MD, of Louis Stokes Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland.

On the basis of these and earlier studies tying hypoglycemia to CV risk, health care providers need to “pay close attention” to low blood sugar and personalize glycemic control targets for each patient based on risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Rajpal said in a presentation of the study at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Also, this suggests that avoidance of drugs associated with increased risk of hypoglycemia – namely insulin, sulfonylureas, or others – is essential to avoid and minimize the risk of cardiovascular events in this patient population with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Rajpal. “Let us remember part of our Hippocratic oath: ‘Above all, do no harm.’ ”

Tailoring treatment to mitigate risk

Mark Schutta, MD, medical director of Penn Rodebaugh Diabetes Center in Philadelphia, said that results of this study suggest a need to carefully select medical therapy for each individual patient with diabetes in order to mitigate CV risk.

“It’s really about tailoring their drugs to their personal situation,” Dr. Schutta said in an interview.

Although newer diabetes drug classes are associated with low to no risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Schutta said that there is still a place for drugs such as sulfonylureas in certain situations.

Among sulfonylureas, glyburide comes with a much higher incidence of hypoglycemia, compared with glipizide and glimepiride, according to Dr. Schutta. “I think there’s a role for both drugs, but you have to be very careful, and you have to get the data from your patients.”

Hypoglycemia frequency and outcomes

Speculation that hypoglycemia could be linked to adverse CV outcomes was sparked years ago by trials such as ADVANCE. Severe hypoglycemia in that study was associated with a 168% increased risk of death from a CV cause (N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 7;363:1410-8).

At the time, ADVANCE investigators said they were unable to find evidence that multiple severe hypoglycemia episodes conferred a greater risk of CV events versus a single hypoglycemia episode, though they added that few patients had recurrent events.

“In other words, the association between the number of hypoglycemia events, and adverse CV outcomes is still unclear,” said Dr. Rajpal in his virtual ADA presentation.

Potential elevated risks with more than five episodes

To evaluate the association between frequent hypoglycemic episodes (i.e., more than five per year, compared with one to five episodes) and CV events, Dr. Rajpal and colleagues evaluated outcomes data for 4.9 million adults with type 2 diabetes found in a large commercial database including information on patients in 27 U.S. health care networks.

Database records indicated that about 182,000 patients, or nearly 4%, had episodes of hyperglycemia, which Dr. Rajpal said was presumed to mean a plasma glucose level of less than 70 mg/dL.

Characteristics of the patients with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were similar to those with one to five episodes, although they were more likely to be 65 years or older, and were “slightly more likely” to be on insulin, which could possibly precipitate more hypoglycemic episodes in that group, Dr. Rajpal said.

Key findings

In the main analysis, Dr. Rajpal said, risk of CV events was significantly increased in those with more than five hypoglycemic episodes, compared with those with one to five episodes, with an odds ratio of 1.61 (95% confidence interval, 1.56-1.66). The incidence of cardiovascular events was 33.1% in those with more than five episodes and 23.5% in those with one to five episodes, according to the data presented.

Risks were also significantly increased specifically for cardiac arrhythmias, cerebrovascular accidents, and MI, Dr. Rajpal said, with ORs of 1.65 (95% CI, 1.9-1.71), 1.38 (95% CI, 1.22-1.56), and 1.43 (95% CI, 1.36-1.50), respectively.

Because individuals in the group with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were more likely to be elderly, Dr. Rajpal said that he and coinvestigators decided to perform an age-specific stratified analysis.

Although cerebral vascular incidence was low in younger patients, risk of CV events overall was nevertheless significantly elevated for those aged 65 years or older, 45-64 years, and 18-44 years, with ORs of 1.69 (95% CI, 1.61-1.7), 1.58 (95% CI, 1.48-1.69), and 1.62 (95% CI, 1.33-1.97).

“The results were still valid in stratified analysis based on different age groups,” Dr. Rajpal said.

Dr. Rajpal and coauthors reported that he had no conflicts of interest related to the research.

SOURCE: Rajpal A et al. ADA 2020, Abstract 161-OR.

Frequent hypoglycemic episodes were linked to a raised incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes in a recent retrospective study, suggesting certain hypoglycemia-associated diabetes drugs should be avoided, an investigator said.

Patients who had more than five hypoglycemic episodes per year had a 61% greater risk of cardiovascular (CV) events, compared with patients with less frequent episodes, according to results of the study.

Although there were fewer strokes among younger patients, the overall increase in cardiovascular event risk held up regardless of age group, according to investigator Aman Rajpal, MD, of Louis Stokes Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland.

On the basis of these and earlier studies tying hypoglycemia to CV risk, health care providers need to “pay close attention” to low blood sugar and personalize glycemic control targets for each patient based on risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Rajpal said in a presentation of the study at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Also, this suggests that avoidance of drugs associated with increased risk of hypoglycemia – namely insulin, sulfonylureas, or others – is essential to avoid and minimize the risk of cardiovascular events in this patient population with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Rajpal. “Let us remember part of our Hippocratic oath: ‘Above all, do no harm.’ ”

Tailoring treatment to mitigate risk

Mark Schutta, MD, medical director of Penn Rodebaugh Diabetes Center in Philadelphia, said that results of this study suggest a need to carefully select medical therapy for each individual patient with diabetes in order to mitigate CV risk.

“It’s really about tailoring their drugs to their personal situation,” Dr. Schutta said in an interview.

Although newer diabetes drug classes are associated with low to no risk of hypoglycemia, Dr. Schutta said that there is still a place for drugs such as sulfonylureas in certain situations.

Among sulfonylureas, glyburide comes with a much higher incidence of hypoglycemia, compared with glipizide and glimepiride, according to Dr. Schutta. “I think there’s a role for both drugs, but you have to be very careful, and you have to get the data from your patients.”

Hypoglycemia frequency and outcomes

Speculation that hypoglycemia could be linked to adverse CV outcomes was sparked years ago by trials such as ADVANCE. Severe hypoglycemia in that study was associated with a 168% increased risk of death from a CV cause (N Engl J Med. 2010 Oct 7;363:1410-8).

At the time, ADVANCE investigators said they were unable to find evidence that multiple severe hypoglycemia episodes conferred a greater risk of CV events versus a single hypoglycemia episode, though they added that few patients had recurrent events.

“In other words, the association between the number of hypoglycemia events, and adverse CV outcomes is still unclear,” said Dr. Rajpal in his virtual ADA presentation.

Potential elevated risks with more than five episodes

To evaluate the association between frequent hypoglycemic episodes (i.e., more than five per year, compared with one to five episodes) and CV events, Dr. Rajpal and colleagues evaluated outcomes data for 4.9 million adults with type 2 diabetes found in a large commercial database including information on patients in 27 U.S. health care networks.

Database records indicated that about 182,000 patients, or nearly 4%, had episodes of hyperglycemia, which Dr. Rajpal said was presumed to mean a plasma glucose level of less than 70 mg/dL.

Characteristics of the patients with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were similar to those with one to five episodes, although they were more likely to be 65 years or older, and were “slightly more likely” to be on insulin, which could possibly precipitate more hypoglycemic episodes in that group, Dr. Rajpal said.

Key findings

In the main analysis, Dr. Rajpal said, risk of CV events was significantly increased in those with more than five hypoglycemic episodes, compared with those with one to five episodes, with an odds ratio of 1.61 (95% confidence interval, 1.56-1.66). The incidence of cardiovascular events was 33.1% in those with more than five episodes and 23.5% in those with one to five episodes, according to the data presented.

Risks were also significantly increased specifically for cardiac arrhythmias, cerebrovascular accidents, and MI, Dr. Rajpal said, with ORs of 1.65 (95% CI, 1.9-1.71), 1.38 (95% CI, 1.22-1.56), and 1.43 (95% CI, 1.36-1.50), respectively.

Because individuals in the group with more than five hypoglycemic episodes were more likely to be elderly, Dr. Rajpal said that he and coinvestigators decided to perform an age-specific stratified analysis.

Although cerebral vascular incidence was low in younger patients, risk of CV events overall was nevertheless significantly elevated for those aged 65 years or older, 45-64 years, and 18-44 years, with ORs of 1.69 (95% CI, 1.61-1.7), 1.58 (95% CI, 1.48-1.69), and 1.62 (95% CI, 1.33-1.97).

“The results were still valid in stratified analysis based on different age groups,” Dr. Rajpal said.

Dr. Rajpal and coauthors reported that he had no conflicts of interest related to the research.

SOURCE: Rajpal A et al. ADA 2020, Abstract 161-OR.

Frequent hypoglycemic episodes were linked to a raised incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes in a recent retrospective study, suggesting certain hypoglycemia-associated diabetes drugs should be avoided, an investigator said.

Patients who had more than five hypoglycemic episodes per year had a 61% greater risk of cardiovascular (CV) events, compared with patients with less frequent episodes, according to results of the study.

Although there were fewer strokes among younger patients, the overall increase in cardiovascular event risk held up regardless of age group, according to investigator Aman Rajpal, MD, of Louis Stokes Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Case Western Reserve University, both in Cleveland.