User login

FibroScan: M probe underestimates hepatic fat content

When performing transient elastography (FibroScan) to evaluate patients for hepatic steatosis, using an M probe instead of an XL probe may significantly underestimate hepatic fat content, according to investigators.

The findings, which were independent of body weight, suggest that probe-specific controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) thresholds are needed to accurately interpret FibroScan results, reported lead author Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

“We have previously determined the optimal threshold of CAP using either [an] M or XL probe for the detection of ... nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, head-to-head comparison of consecutive measurements of CAP with both the M and XL probes versus MRI-PDFF [proton density fat fraction] ... has not been reported yet.”

Dr. Caussy and colleagues set out to do just that. They enrolled 105 individuals with and without NAFLD who had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 30.6 kg/m2, as this represented a typical population screened for NAFLD. After evaluation for other causes of hepatic steatosis and liver disease, participants underwent MRI-PDFF, which served as a gold standard, followed by FibroScan using both M and XL probes on the same day.

The primary outcome was hepatic steatosis (MRI-PDFF of at least 5%), while the secondary outcome was MRI-PDFF–detected hepatic fat content of at least 10%, the latter of which has been “used in several therapeutic trials as inclusion criteria,” the investigators noted.

A total of 100 participants were included in the final analysis, of whom two-thirds (66%) underwent MRI and FibroScan on the same day, with a mean interval between test types of 11 days. Most participants (68%) had an MRI-PDFF of at least 5%, while almost half (48%) exceeded an MRI-PDFF of 10%.

The mean CAP measurement with the M probe was 310 dB/m, which was significantly lower than the mean value detected by the XL probe, which was 317 dB/m (P = .007). In participants with hepatic steatosis, when the M probe was used for those with a BMI of less than 30, and the XL probe was used for those with a BMI of 30 or more, the M probe still provided a significantly lower measure of hepatic fat content (312 vs. 345 dB/m; P = .0035).

“[T]hese results have direct application in routine clinical practice,” the investigators wrote, “as [they] will help clinicians interpreting CAP measurements depending on the type of probe used.”

Dr. Caussy and colleagues went on to offer a diagnostic algorithm involving optimal probe-specific thresholds for CAP based on hepatic fat content. Individuals screened with an M probe who have a CAP of 294 dB/m or more should be considered positive for NAFLD, while patients screened with an XL probe need to have a CAP of at least 307 dB/m to be NAFLD positive.

For the XL probe, but not the M probe, diagnostic accuracy depended upon an interquartile range of less than 30 dB/m. The investigators noted that this finding should alter the interpretation of a 2019 study by Eddowes and colleagues, which concluded that interquartile range was unrelated to diagnostic accuracy.

“As Eddowes et al. did not perform head-to-head comparison of CAP measurement with both the M and XL probes, this important difference could not have been observed,” the investigators wrote, noting that “an interquartile range of CAP below 30 dB/m should be considered as a quality indicator that significantly improves the diagnostic performance of CAP using the XL probe for the detection of hepatic steatosis in NAFLD.”

The investigators concluded by suggesting that their findings will drive research forward.

“The use of these new thresholds will help to further assess the clinical utility of CAP for the detection of hepatic steatosis and its cost-effectiveness, compared with other modalities, to develop optimal strategies for the screening of NAFLD,” they wrote.

The study was funded by Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Gastroenterological Association, and others. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.060.

When performing transient elastography (FibroScan) to evaluate patients for hepatic steatosis, using an M probe instead of an XL probe may significantly underestimate hepatic fat content, according to investigators.

The findings, which were independent of body weight, suggest that probe-specific controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) thresholds are needed to accurately interpret FibroScan results, reported lead author Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

“We have previously determined the optimal threshold of CAP using either [an] M or XL probe for the detection of ... nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, head-to-head comparison of consecutive measurements of CAP with both the M and XL probes versus MRI-PDFF [proton density fat fraction] ... has not been reported yet.”

Dr. Caussy and colleagues set out to do just that. They enrolled 105 individuals with and without NAFLD who had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 30.6 kg/m2, as this represented a typical population screened for NAFLD. After evaluation for other causes of hepatic steatosis and liver disease, participants underwent MRI-PDFF, which served as a gold standard, followed by FibroScan using both M and XL probes on the same day.

The primary outcome was hepatic steatosis (MRI-PDFF of at least 5%), while the secondary outcome was MRI-PDFF–detected hepatic fat content of at least 10%, the latter of which has been “used in several therapeutic trials as inclusion criteria,” the investigators noted.

A total of 100 participants were included in the final analysis, of whom two-thirds (66%) underwent MRI and FibroScan on the same day, with a mean interval between test types of 11 days. Most participants (68%) had an MRI-PDFF of at least 5%, while almost half (48%) exceeded an MRI-PDFF of 10%.

The mean CAP measurement with the M probe was 310 dB/m, which was significantly lower than the mean value detected by the XL probe, which was 317 dB/m (P = .007). In participants with hepatic steatosis, when the M probe was used for those with a BMI of less than 30, and the XL probe was used for those with a BMI of 30 or more, the M probe still provided a significantly lower measure of hepatic fat content (312 vs. 345 dB/m; P = .0035).

“[T]hese results have direct application in routine clinical practice,” the investigators wrote, “as [they] will help clinicians interpreting CAP measurements depending on the type of probe used.”

Dr. Caussy and colleagues went on to offer a diagnostic algorithm involving optimal probe-specific thresholds for CAP based on hepatic fat content. Individuals screened with an M probe who have a CAP of 294 dB/m or more should be considered positive for NAFLD, while patients screened with an XL probe need to have a CAP of at least 307 dB/m to be NAFLD positive.

For the XL probe, but not the M probe, diagnostic accuracy depended upon an interquartile range of less than 30 dB/m. The investigators noted that this finding should alter the interpretation of a 2019 study by Eddowes and colleagues, which concluded that interquartile range was unrelated to diagnostic accuracy.

“As Eddowes et al. did not perform head-to-head comparison of CAP measurement with both the M and XL probes, this important difference could not have been observed,” the investigators wrote, noting that “an interquartile range of CAP below 30 dB/m should be considered as a quality indicator that significantly improves the diagnostic performance of CAP using the XL probe for the detection of hepatic steatosis in NAFLD.”

The investigators concluded by suggesting that their findings will drive research forward.

“The use of these new thresholds will help to further assess the clinical utility of CAP for the detection of hepatic steatosis and its cost-effectiveness, compared with other modalities, to develop optimal strategies for the screening of NAFLD,” they wrote.

The study was funded by Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Gastroenterological Association, and others. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.060.

When performing transient elastography (FibroScan) to evaluate patients for hepatic steatosis, using an M probe instead of an XL probe may significantly underestimate hepatic fat content, according to investigators.

The findings, which were independent of body weight, suggest that probe-specific controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) thresholds are needed to accurately interpret FibroScan results, reported lead author Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues.

“We have previously determined the optimal threshold of CAP using either [an] M or XL probe for the detection of ... nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, head-to-head comparison of consecutive measurements of CAP with both the M and XL probes versus MRI-PDFF [proton density fat fraction] ... has not been reported yet.”

Dr. Caussy and colleagues set out to do just that. They enrolled 105 individuals with and without NAFLD who had a mean body mass index (BMI) of 30.6 kg/m2, as this represented a typical population screened for NAFLD. After evaluation for other causes of hepatic steatosis and liver disease, participants underwent MRI-PDFF, which served as a gold standard, followed by FibroScan using both M and XL probes on the same day.

The primary outcome was hepatic steatosis (MRI-PDFF of at least 5%), while the secondary outcome was MRI-PDFF–detected hepatic fat content of at least 10%, the latter of which has been “used in several therapeutic trials as inclusion criteria,” the investigators noted.

A total of 100 participants were included in the final analysis, of whom two-thirds (66%) underwent MRI and FibroScan on the same day, with a mean interval between test types of 11 days. Most participants (68%) had an MRI-PDFF of at least 5%, while almost half (48%) exceeded an MRI-PDFF of 10%.

The mean CAP measurement with the M probe was 310 dB/m, which was significantly lower than the mean value detected by the XL probe, which was 317 dB/m (P = .007). In participants with hepatic steatosis, when the M probe was used for those with a BMI of less than 30, and the XL probe was used for those with a BMI of 30 or more, the M probe still provided a significantly lower measure of hepatic fat content (312 vs. 345 dB/m; P = .0035).

“[T]hese results have direct application in routine clinical practice,” the investigators wrote, “as [they] will help clinicians interpreting CAP measurements depending on the type of probe used.”

Dr. Caussy and colleagues went on to offer a diagnostic algorithm involving optimal probe-specific thresholds for CAP based on hepatic fat content. Individuals screened with an M probe who have a CAP of 294 dB/m or more should be considered positive for NAFLD, while patients screened with an XL probe need to have a CAP of at least 307 dB/m to be NAFLD positive.

For the XL probe, but not the M probe, diagnostic accuracy depended upon an interquartile range of less than 30 dB/m. The investigators noted that this finding should alter the interpretation of a 2019 study by Eddowes and colleagues, which concluded that interquartile range was unrelated to diagnostic accuracy.

“As Eddowes et al. did not perform head-to-head comparison of CAP measurement with both the M and XL probes, this important difference could not have been observed,” the investigators wrote, noting that “an interquartile range of CAP below 30 dB/m should be considered as a quality indicator that significantly improves the diagnostic performance of CAP using the XL probe for the detection of hepatic steatosis in NAFLD.”

The investigators concluded by suggesting that their findings will drive research forward.

“The use of these new thresholds will help to further assess the clinical utility of CAP for the detection of hepatic steatosis and its cost-effectiveness, compared with other modalities, to develop optimal strategies for the screening of NAFLD,” they wrote.

The study was funded by Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, the American Gastroenterological Association, and others. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.060.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

‘Hospital at home’ cuts ED visits and costs for cancer patients

Visits to the emergency department (ED) and hospitalizations are often frequent occurrences for cancer patients, but what if the “hospital” could be brought into the home instead?

A new American cohort study provides evidence that this can be a workable option for cancer patients. The authors report improved patient outcomes, with 56% lower odds of unplanned hospitalizations (P = .001), 45% lower odds of ED visits (P = .037), and 50% lower cumulative charges (P = .001), as compared with patients who received usual care.

“The oncology hospital-at-home model of care that extends acute-level care to the patient at home offers promise in addressing a long-term gap in cancer care service delivery,” said lead author Kathi Mooney, PhD, RN, interim senior director of population sciences at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and distinguished professor of nursing at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “In light of the current global pandemic, we are compelled to consider new ways to provide cancer care, and the oncology hospital-at-home model is on point to address critical elements of an improved cancer care delivery system.”

Mooney presented the findings during the virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020 annual meeting (abstract 7000).

The hospital-at-home model of care provides hospital-level care in the comfort of the patient’s home and is a component of many healthcare systems worldwide. Although it was introduced in the United States more than 2 decades ago, it has not been widely adopted or studied specifically in oncology.

Most cancer treatment is provided on an outpatient basis, which means that patients experience significant adverse events, toxicities, and disease progression while they are at home. Thus, Mooney noted, patients tend to rely heavily on the ED and sometimes experience unplanned hospitalizations and 30-day readmissions.

“These care patterns are distressing to the patients and their families and tax healthcare resources,” she said. “They are even more concerning and salient as we endeavor to protect cancer patients and provide cancer care during a pandemic.”

Currently, strategies to evaluate and support cancer patients and caregivers at home are limited. In 2018, the Huntsman Cancer Institute implemented Huntsman at Home, a demonstration project to evaluate the utility of an oncology hospital-at-home model.

Significantly Fewer Unplanned Hospitalizations

Huntsman at Home is run by nurse practitioner and registered nurse teams who deliver acute-level care at home. Physicians provide backup support for both medical oncology and palliative care. Nurse practitioners also work directly with the patient’s oncology team to coordinate care needs, including services such as social work and physical therapy.

To evaluate the hospital-at-home model, Mooney and colleagues compared patients who were enrolled in the program with those who received usual care. The usual-care comparison group was drawn from patients who lived in the Salt Lake City area. These patients would have qualified for enrollment in the Huntsman at Home program, but they lived outside the 20-mile service area.

The cohort included 367 patients (169 Huntsman at Home patients and 198 usual-care patients). Of those patients, 77% had stage IV cancer. A range of cancer types was represented; the most common were colon, gynecologic, prostate, and lung cancers. As compared to the usual-care group, those in the home model were more likely to be women (61% vs 43%).

During the first 30 days after admission, Huntsman at Home patients had significantly fewer unplanned hospitalizations (19.5% vs 35.4%) and a shorter length of stay (1.4 vs 2.6 days). Their care was also less expensive. The estimated charges for the hospital-at-home patients was $10,238, compared with $21,363 for the usual-care patients. There was no real difference in stays in the intensive care unit between the two groups.

Mooney noted that since there have been few studies of the hospital-at-home model for oncology patients, the investigators’ initial focus was on patients at hospital discharge who needed continued acute-level care and those who had acute problems identified through their oncology care clinic. Therefore, patients were not admitted to the program directly from emergency services, and chemotherapy infusions were not provided, although these are “other areas to consider in an oncology hospital-at-home model.”

Other limitations of the study were that it was not a randomized trial, and the evaluation was from a single program located at one comprehensive cancer center.

“These findings provide the oncology community with an opportunity to rethink cancer care as solely hospital- and clinic-based and instead reimagine care delivery that moves with the patient with key components provided at home,” said Mooney. “We plan to continue the development and evaluation of Huntsman at Home and extend care to admission from the emergency department.”

She added that, together with Flatiron Health, they are validating a tool to prospectively predict, on the basis of the likelihood of ED use, which patients may benefit from Huntsman at Home support. They also plan to extend care to patients who live at a distance from the cancer center and in rural communities, and may include chemotherapy infusion services.

Palliative Care Patients Prefer Home-Based Treatment

In a discussion of the paper, Lynne Wagner, PhD, a professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy with the Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and a member of the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center, explained that some “aspects of healthcare are more translatable to a virtual or alternative delivery model than others. An area of cancer care greatly in need of innovation and quality improvement pertains to the management of oncologic emergencies.”

She pointed out that optimal care for oncologic emergencies requires the “intersection of oncology and emergency medicine specialists,” but there are often no well-defined processes for care coordination in place.

“Emergency department utilization could be reduced through greater precision with regard to risk stratification and early intervention and improved outpatient management, including improved symptom management,” said Wagner.

Wagner suggested that research should incorporate patient-reported outcomes so as to measure patient-centered benefits of home-based care. “Patients who are receiving palliative care services prefer home-based care, and it’s reasonable to anticipate this finding would extrapolate to the investigator’s target population,” she said. “However, there may also be unanticipated consequences, potentially including increased anxiety or increased burden on caretakers.”

In addition, the tangible and intangible costs associated with traveling to receive healthcare services and time away from work can be reduced with home-based care, and this should also be quantified. “The costs associated with COVID infection should be estimated to realize the full economic value of this care model, given significant reductions in cohort exposure afforded by home-based visits,” Wagner added.

The Huntsman at Home program is funded by the Huntsman Cancer Institute. The evaluation was funded by the Cambia Health Foundation. Mooney has a consulting or advisory role with Cognitive Medical System, Inc, and has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property for the development of Symptom Care at Home, a remote symptom-monitoring platform developed through research grants funded by the National Cancer Institute. No royalties have been received to date. Wagner has relationships with Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, and Johnson & Johnson.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Visits to the emergency department (ED) and hospitalizations are often frequent occurrences for cancer patients, but what if the “hospital” could be brought into the home instead?

A new American cohort study provides evidence that this can be a workable option for cancer patients. The authors report improved patient outcomes, with 56% lower odds of unplanned hospitalizations (P = .001), 45% lower odds of ED visits (P = .037), and 50% lower cumulative charges (P = .001), as compared with patients who received usual care.

“The oncology hospital-at-home model of care that extends acute-level care to the patient at home offers promise in addressing a long-term gap in cancer care service delivery,” said lead author Kathi Mooney, PhD, RN, interim senior director of population sciences at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and distinguished professor of nursing at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “In light of the current global pandemic, we are compelled to consider new ways to provide cancer care, and the oncology hospital-at-home model is on point to address critical elements of an improved cancer care delivery system.”

Mooney presented the findings during the virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020 annual meeting (abstract 7000).

The hospital-at-home model of care provides hospital-level care in the comfort of the patient’s home and is a component of many healthcare systems worldwide. Although it was introduced in the United States more than 2 decades ago, it has not been widely adopted or studied specifically in oncology.

Most cancer treatment is provided on an outpatient basis, which means that patients experience significant adverse events, toxicities, and disease progression while they are at home. Thus, Mooney noted, patients tend to rely heavily on the ED and sometimes experience unplanned hospitalizations and 30-day readmissions.

“These care patterns are distressing to the patients and their families and tax healthcare resources,” she said. “They are even more concerning and salient as we endeavor to protect cancer patients and provide cancer care during a pandemic.”

Currently, strategies to evaluate and support cancer patients and caregivers at home are limited. In 2018, the Huntsman Cancer Institute implemented Huntsman at Home, a demonstration project to evaluate the utility of an oncology hospital-at-home model.

Significantly Fewer Unplanned Hospitalizations

Huntsman at Home is run by nurse practitioner and registered nurse teams who deliver acute-level care at home. Physicians provide backup support for both medical oncology and palliative care. Nurse practitioners also work directly with the patient’s oncology team to coordinate care needs, including services such as social work and physical therapy.

To evaluate the hospital-at-home model, Mooney and colleagues compared patients who were enrolled in the program with those who received usual care. The usual-care comparison group was drawn from patients who lived in the Salt Lake City area. These patients would have qualified for enrollment in the Huntsman at Home program, but they lived outside the 20-mile service area.

The cohort included 367 patients (169 Huntsman at Home patients and 198 usual-care patients). Of those patients, 77% had stage IV cancer. A range of cancer types was represented; the most common were colon, gynecologic, prostate, and lung cancers. As compared to the usual-care group, those in the home model were more likely to be women (61% vs 43%).

During the first 30 days after admission, Huntsman at Home patients had significantly fewer unplanned hospitalizations (19.5% vs 35.4%) and a shorter length of stay (1.4 vs 2.6 days). Their care was also less expensive. The estimated charges for the hospital-at-home patients was $10,238, compared with $21,363 for the usual-care patients. There was no real difference in stays in the intensive care unit between the two groups.

Mooney noted that since there have been few studies of the hospital-at-home model for oncology patients, the investigators’ initial focus was on patients at hospital discharge who needed continued acute-level care and those who had acute problems identified through their oncology care clinic. Therefore, patients were not admitted to the program directly from emergency services, and chemotherapy infusions were not provided, although these are “other areas to consider in an oncology hospital-at-home model.”

Other limitations of the study were that it was not a randomized trial, and the evaluation was from a single program located at one comprehensive cancer center.

“These findings provide the oncology community with an opportunity to rethink cancer care as solely hospital- and clinic-based and instead reimagine care delivery that moves with the patient with key components provided at home,” said Mooney. “We plan to continue the development and evaluation of Huntsman at Home and extend care to admission from the emergency department.”

She added that, together with Flatiron Health, they are validating a tool to prospectively predict, on the basis of the likelihood of ED use, which patients may benefit from Huntsman at Home support. They also plan to extend care to patients who live at a distance from the cancer center and in rural communities, and may include chemotherapy infusion services.

Palliative Care Patients Prefer Home-Based Treatment

In a discussion of the paper, Lynne Wagner, PhD, a professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy with the Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and a member of the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center, explained that some “aspects of healthcare are more translatable to a virtual or alternative delivery model than others. An area of cancer care greatly in need of innovation and quality improvement pertains to the management of oncologic emergencies.”

She pointed out that optimal care for oncologic emergencies requires the “intersection of oncology and emergency medicine specialists,” but there are often no well-defined processes for care coordination in place.

“Emergency department utilization could be reduced through greater precision with regard to risk stratification and early intervention and improved outpatient management, including improved symptom management,” said Wagner.

Wagner suggested that research should incorporate patient-reported outcomes so as to measure patient-centered benefits of home-based care. “Patients who are receiving palliative care services prefer home-based care, and it’s reasonable to anticipate this finding would extrapolate to the investigator’s target population,” she said. “However, there may also be unanticipated consequences, potentially including increased anxiety or increased burden on caretakers.”

In addition, the tangible and intangible costs associated with traveling to receive healthcare services and time away from work can be reduced with home-based care, and this should also be quantified. “The costs associated with COVID infection should be estimated to realize the full economic value of this care model, given significant reductions in cohort exposure afforded by home-based visits,” Wagner added.

The Huntsman at Home program is funded by the Huntsman Cancer Institute. The evaluation was funded by the Cambia Health Foundation. Mooney has a consulting or advisory role with Cognitive Medical System, Inc, and has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property for the development of Symptom Care at Home, a remote symptom-monitoring platform developed through research grants funded by the National Cancer Institute. No royalties have been received to date. Wagner has relationships with Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, and Johnson & Johnson.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Visits to the emergency department (ED) and hospitalizations are often frequent occurrences for cancer patients, but what if the “hospital” could be brought into the home instead?

A new American cohort study provides evidence that this can be a workable option for cancer patients. The authors report improved patient outcomes, with 56% lower odds of unplanned hospitalizations (P = .001), 45% lower odds of ED visits (P = .037), and 50% lower cumulative charges (P = .001), as compared with patients who received usual care.

“The oncology hospital-at-home model of care that extends acute-level care to the patient at home offers promise in addressing a long-term gap in cancer care service delivery,” said lead author Kathi Mooney, PhD, RN, interim senior director of population sciences at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and distinguished professor of nursing at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “In light of the current global pandemic, we are compelled to consider new ways to provide cancer care, and the oncology hospital-at-home model is on point to address critical elements of an improved cancer care delivery system.”

Mooney presented the findings during the virtual scientific program of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020 annual meeting (abstract 7000).

The hospital-at-home model of care provides hospital-level care in the comfort of the patient’s home and is a component of many healthcare systems worldwide. Although it was introduced in the United States more than 2 decades ago, it has not been widely adopted or studied specifically in oncology.

Most cancer treatment is provided on an outpatient basis, which means that patients experience significant adverse events, toxicities, and disease progression while they are at home. Thus, Mooney noted, patients tend to rely heavily on the ED and sometimes experience unplanned hospitalizations and 30-day readmissions.

“These care patterns are distressing to the patients and their families and tax healthcare resources,” she said. “They are even more concerning and salient as we endeavor to protect cancer patients and provide cancer care during a pandemic.”

Currently, strategies to evaluate and support cancer patients and caregivers at home are limited. In 2018, the Huntsman Cancer Institute implemented Huntsman at Home, a demonstration project to evaluate the utility of an oncology hospital-at-home model.

Significantly Fewer Unplanned Hospitalizations

Huntsman at Home is run by nurse practitioner and registered nurse teams who deliver acute-level care at home. Physicians provide backup support for both medical oncology and palliative care. Nurse practitioners also work directly with the patient’s oncology team to coordinate care needs, including services such as social work and physical therapy.

To evaluate the hospital-at-home model, Mooney and colleagues compared patients who were enrolled in the program with those who received usual care. The usual-care comparison group was drawn from patients who lived in the Salt Lake City area. These patients would have qualified for enrollment in the Huntsman at Home program, but they lived outside the 20-mile service area.

The cohort included 367 patients (169 Huntsman at Home patients and 198 usual-care patients). Of those patients, 77% had stage IV cancer. A range of cancer types was represented; the most common were colon, gynecologic, prostate, and lung cancers. As compared to the usual-care group, those in the home model were more likely to be women (61% vs 43%).

During the first 30 days after admission, Huntsman at Home patients had significantly fewer unplanned hospitalizations (19.5% vs 35.4%) and a shorter length of stay (1.4 vs 2.6 days). Their care was also less expensive. The estimated charges for the hospital-at-home patients was $10,238, compared with $21,363 for the usual-care patients. There was no real difference in stays in the intensive care unit between the two groups.

Mooney noted that since there have been few studies of the hospital-at-home model for oncology patients, the investigators’ initial focus was on patients at hospital discharge who needed continued acute-level care and those who had acute problems identified through their oncology care clinic. Therefore, patients were not admitted to the program directly from emergency services, and chemotherapy infusions were not provided, although these are “other areas to consider in an oncology hospital-at-home model.”

Other limitations of the study were that it was not a randomized trial, and the evaluation was from a single program located at one comprehensive cancer center.

“These findings provide the oncology community with an opportunity to rethink cancer care as solely hospital- and clinic-based and instead reimagine care delivery that moves with the patient with key components provided at home,” said Mooney. “We plan to continue the development and evaluation of Huntsman at Home and extend care to admission from the emergency department.”

She added that, together with Flatiron Health, they are validating a tool to prospectively predict, on the basis of the likelihood of ED use, which patients may benefit from Huntsman at Home support. They also plan to extend care to patients who live at a distance from the cancer center and in rural communities, and may include chemotherapy infusion services.

Palliative Care Patients Prefer Home-Based Treatment

In a discussion of the paper, Lynne Wagner, PhD, a professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy with the Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and a member of the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center, explained that some “aspects of healthcare are more translatable to a virtual or alternative delivery model than others. An area of cancer care greatly in need of innovation and quality improvement pertains to the management of oncologic emergencies.”

She pointed out that optimal care for oncologic emergencies requires the “intersection of oncology and emergency medicine specialists,” but there are often no well-defined processes for care coordination in place.

“Emergency department utilization could be reduced through greater precision with regard to risk stratification and early intervention and improved outpatient management, including improved symptom management,” said Wagner.

Wagner suggested that research should incorporate patient-reported outcomes so as to measure patient-centered benefits of home-based care. “Patients who are receiving palliative care services prefer home-based care, and it’s reasonable to anticipate this finding would extrapolate to the investigator’s target population,” she said. “However, there may also be unanticipated consequences, potentially including increased anxiety or increased burden on caretakers.”

In addition, the tangible and intangible costs associated with traveling to receive healthcare services and time away from work can be reduced with home-based care, and this should also be quantified. “The costs associated with COVID infection should be estimated to realize the full economic value of this care model, given significant reductions in cohort exposure afforded by home-based visits,” Wagner added.

The Huntsman at Home program is funded by the Huntsman Cancer Institute. The evaluation was funded by the Cambia Health Foundation. Mooney has a consulting or advisory role with Cognitive Medical System, Inc, and has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property for the development of Symptom Care at Home, a remote symptom-monitoring platform developed through research grants funded by the National Cancer Institute. No royalties have been received to date. Wagner has relationships with Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, and Johnson & Johnson.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCO 2020

Addressing suicide prevention among South Asian Americans

Multifaceted strategies are needed to address unique cultural factors

On first glance, the age-adjusted rate of suicide for Asian and Pacific Islander populations living in the United States looks comparatively low.

Over the past 2 decades in the United States, for example, the overall rate increased by 35%, from, 10.5 to 14.2 per 100,000 individuals. That compares with a rate of 7.0 per 100,000 among Asian and Pacific Islander communities.1

However, because of the aggregate nature (national suicide mortality data combine people of Asian, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islander descent into a single group) in which these data are reported, a significant amount of salient information on subgroups of Asian Americans is lost.2 There is a growing body of research on the mental health of Asian Americans, but the dearth of information and research on suicide in South Asians is striking.3 In fact, a review of literature finds fewer than 10 articles on the topic that have been published in peer-reviewed journals in the last decade. to provide effective, culturally sensitive care.

Diverse group

There are 3.4 million individuals of South Asian descent in the United States. Geographically, South Asians may have familial and cultural/historical roots in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, and Pakistan.4 They enjoy a rich diversity in terms of cultural and religious beliefs, language, socioeconomic status, modes of acculturation, and immigration patterns. Asian Indians are the largest group of South Asians in the United States. They are highly educated, with a larger proportion of them pursuing an undergraduate and/or graduate level education than the general population. The median household income of Asian Indians is also higher than the national average.5

In general, suicide, like all mental health issues, is a stigmatized and taboo topic in the South Asian community.6 Also, South Asian Americans are hesitant to seek mental health care because of a perceived inability of Western health care professionals to understand their cultural views. Extrapolation from data on South Asians in the United Kingdom, aggregate statistics for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and studies on South Asians in the United States highlight two South Asian subgroups that are particularly vulnerable to suicide. These are young adults (aged 18-24 years) and women.7

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for young Asian American men in the United States. Rates of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts are higher among younger Asian Americans (aged 18-24 years) than among older Asian American adults. Young Asian American adults have been found to have higher levels of suicidal ideation than their white counterparts.8,9 Acculturation or assimilating into a different culture, familial violence as a child, hopelessness or a thought pattern with a pessimistic outlook, depression, and childhood sexual abuse have all been found to be positively correlated with suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in South Asian Americans. One study that conducted0 in-group analysis on undergraduate university students of South Asian descent living in New York found higher levels of hopelessness and depression in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans.10

In addition, higher levels of suicidal ideation are reported in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans. These results resemble findings from similar studies in the United Kingdom. A posited reason for these findings is a difference in religious beliefs. Pakistani and Bangladeshi Americans are predominantly Muslim, have stronger moral beliefs against suicide, and consider it a sin as defined by Islamic beliefs. Asian Indians, in contrast, are majority Hindu and believe in reincarnation – a context that might make suicide seem more permissible.11

South Asian women are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and/or familial violence. Cultural gender norms, traditional norms, and patriarchal ideology in the South Asian community make quantifying the level of childhood sexual abuse and familial violence a challenge. Furthermore, culturally, South Asian women are often considered subordinate relative to men, and discussion around family violence and childhood sexual abuse is avoided. Studies from the United Kingdom find a lack of knowledge around, disclosure of, and fear of reporting childhood sexual abuse in South Asian women. A study of a sample of representative South Asian American women found that 25.2% had experienced some form of childhood sexual abuse.12

Research also suggests that South Asians in the United States have some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence. Another study in the United States found that two out of five South Asian women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence. This is much higher than the rate found in representative general U.S. population samples.

Literature suggests that exposure to these factors increases womens’ risk for suicidal ideation and attempted suicide. In the United Kingdom, research on South Asian women (aged 18-24 years) has found rates of attempted suicide to be three times higher than those of their white counterparts. Research from the United Kingdom and the United States suggests that younger married South Asian women are exposed to emotional and/or physical abuse from their spouse or in-laws, which is often a mediating factor in their increased risk for suicide.

Attempts to address suicide in the South Asian American community have to be multifaceted. An ideal approach would consist of educating, and connecting with, the community through ethnic media and trusted community sources, such as primary care doctors, caregivers, and social workers. In line with established American Psychological Association guidelines on caring for individuals of immigrant origin, health care professionals should document the patient’s number of generations in the country, number of years in the country, language fluency, family and community support, educational level, social status changes related to immigration, intimate relationships with people of different backgrounds, and stress related to acculturation. Special attention should be paid to South Asian women. Health care professionals should screen South Asian women for past and current intimate partner violence, provide culturally appropriate intimate partner violence resources, and be prepared to refer them to legal counseling services. Also, South Asian women should be screened for a history of exposure to familial violence and childhood sexual abuse.1

To adequately serve this population, there is a need to build capacity in the provision of culturally appropriate mental health services. Access to mental health care professionals through settings such as shelters for abused women, South Asian community–based organizations, youth centers, college counseling, and senior centers would encourage individuals to seek care without the threat of being stigmatized.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 330. 2018 Nov.

2. Ahmad-Stout DJ and Nath SR. J College Stud Psychother. 2013 Jan 10;27(1):43-61.

3. Li H and Keshavan M. Asian J Psychiatry. 2011;4(1):1.

4. Nagaraj NC et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019 Oct;21(5):978-1003.

5. Nagaraj NC et al. J Comm Health. 2018;43(3):543-51.

6. Cao KO. Generations. 2014;30(4):82-5.

7. Hurwitz EJ et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(3):251-61.

8. Polanco-Roman L et al. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019 Dec 23. doi: 10.1037/cpd0000313.

9. Erausquin JT et al. J Youth Adolesc. 2019 Sep;48(9):1796-1805.

10. Lane R et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2016;7(2):120-8.

11. Nath SR et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2018;9(4):334-343.

12. Robertson HA et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016 Jul 31;18(4):921-7.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University (CMU) College of Medicine, Mt. Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in immigrant populations.

Multifaceted strategies are needed to address unique cultural factors

Multifaceted strategies are needed to address unique cultural factors

On first glance, the age-adjusted rate of suicide for Asian and Pacific Islander populations living in the United States looks comparatively low.

Over the past 2 decades in the United States, for example, the overall rate increased by 35%, from, 10.5 to 14.2 per 100,000 individuals. That compares with a rate of 7.0 per 100,000 among Asian and Pacific Islander communities.1

However, because of the aggregate nature (national suicide mortality data combine people of Asian, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islander descent into a single group) in which these data are reported, a significant amount of salient information on subgroups of Asian Americans is lost.2 There is a growing body of research on the mental health of Asian Americans, but the dearth of information and research on suicide in South Asians is striking.3 In fact, a review of literature finds fewer than 10 articles on the topic that have been published in peer-reviewed journals in the last decade. to provide effective, culturally sensitive care.

Diverse group

There are 3.4 million individuals of South Asian descent in the United States. Geographically, South Asians may have familial and cultural/historical roots in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, and Pakistan.4 They enjoy a rich diversity in terms of cultural and religious beliefs, language, socioeconomic status, modes of acculturation, and immigration patterns. Asian Indians are the largest group of South Asians in the United States. They are highly educated, with a larger proportion of them pursuing an undergraduate and/or graduate level education than the general population. The median household income of Asian Indians is also higher than the national average.5

In general, suicide, like all mental health issues, is a stigmatized and taboo topic in the South Asian community.6 Also, South Asian Americans are hesitant to seek mental health care because of a perceived inability of Western health care professionals to understand their cultural views. Extrapolation from data on South Asians in the United Kingdom, aggregate statistics for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and studies on South Asians in the United States highlight two South Asian subgroups that are particularly vulnerable to suicide. These are young adults (aged 18-24 years) and women.7

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for young Asian American men in the United States. Rates of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts are higher among younger Asian Americans (aged 18-24 years) than among older Asian American adults. Young Asian American adults have been found to have higher levels of suicidal ideation than their white counterparts.8,9 Acculturation or assimilating into a different culture, familial violence as a child, hopelessness or a thought pattern with a pessimistic outlook, depression, and childhood sexual abuse have all been found to be positively correlated with suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in South Asian Americans. One study that conducted0 in-group analysis on undergraduate university students of South Asian descent living in New York found higher levels of hopelessness and depression in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans.10

In addition, higher levels of suicidal ideation are reported in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans. These results resemble findings from similar studies in the United Kingdom. A posited reason for these findings is a difference in religious beliefs. Pakistani and Bangladeshi Americans are predominantly Muslim, have stronger moral beliefs against suicide, and consider it a sin as defined by Islamic beliefs. Asian Indians, in contrast, are majority Hindu and believe in reincarnation – a context that might make suicide seem more permissible.11

South Asian women are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and/or familial violence. Cultural gender norms, traditional norms, and patriarchal ideology in the South Asian community make quantifying the level of childhood sexual abuse and familial violence a challenge. Furthermore, culturally, South Asian women are often considered subordinate relative to men, and discussion around family violence and childhood sexual abuse is avoided. Studies from the United Kingdom find a lack of knowledge around, disclosure of, and fear of reporting childhood sexual abuse in South Asian women. A study of a sample of representative South Asian American women found that 25.2% had experienced some form of childhood sexual abuse.12

Research also suggests that South Asians in the United States have some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence. Another study in the United States found that two out of five South Asian women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence. This is much higher than the rate found in representative general U.S. population samples.

Literature suggests that exposure to these factors increases womens’ risk for suicidal ideation and attempted suicide. In the United Kingdom, research on South Asian women (aged 18-24 years) has found rates of attempted suicide to be three times higher than those of their white counterparts. Research from the United Kingdom and the United States suggests that younger married South Asian women are exposed to emotional and/or physical abuse from their spouse or in-laws, which is often a mediating factor in their increased risk for suicide.

Attempts to address suicide in the South Asian American community have to be multifaceted. An ideal approach would consist of educating, and connecting with, the community through ethnic media and trusted community sources, such as primary care doctors, caregivers, and social workers. In line with established American Psychological Association guidelines on caring for individuals of immigrant origin, health care professionals should document the patient’s number of generations in the country, number of years in the country, language fluency, family and community support, educational level, social status changes related to immigration, intimate relationships with people of different backgrounds, and stress related to acculturation. Special attention should be paid to South Asian women. Health care professionals should screen South Asian women for past and current intimate partner violence, provide culturally appropriate intimate partner violence resources, and be prepared to refer them to legal counseling services. Also, South Asian women should be screened for a history of exposure to familial violence and childhood sexual abuse.1

To adequately serve this population, there is a need to build capacity in the provision of culturally appropriate mental health services. Access to mental health care professionals through settings such as shelters for abused women, South Asian community–based organizations, youth centers, college counseling, and senior centers would encourage individuals to seek care without the threat of being stigmatized.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 330. 2018 Nov.

2. Ahmad-Stout DJ and Nath SR. J College Stud Psychother. 2013 Jan 10;27(1):43-61.

3. Li H and Keshavan M. Asian J Psychiatry. 2011;4(1):1.

4. Nagaraj NC et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019 Oct;21(5):978-1003.

5. Nagaraj NC et al. J Comm Health. 2018;43(3):543-51.

6. Cao KO. Generations. 2014;30(4):82-5.

7. Hurwitz EJ et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(3):251-61.

8. Polanco-Roman L et al. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019 Dec 23. doi: 10.1037/cpd0000313.

9. Erausquin JT et al. J Youth Adolesc. 2019 Sep;48(9):1796-1805.

10. Lane R et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2016;7(2):120-8.

11. Nath SR et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2018;9(4):334-343.

12. Robertson HA et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016 Jul 31;18(4):921-7.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University (CMU) College of Medicine, Mt. Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in immigrant populations.

On first glance, the age-adjusted rate of suicide for Asian and Pacific Islander populations living in the United States looks comparatively low.

Over the past 2 decades in the United States, for example, the overall rate increased by 35%, from, 10.5 to 14.2 per 100,000 individuals. That compares with a rate of 7.0 per 100,000 among Asian and Pacific Islander communities.1

However, because of the aggregate nature (national suicide mortality data combine people of Asian, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islander descent into a single group) in which these data are reported, a significant amount of salient information on subgroups of Asian Americans is lost.2 There is a growing body of research on the mental health of Asian Americans, but the dearth of information and research on suicide in South Asians is striking.3 In fact, a review of literature finds fewer than 10 articles on the topic that have been published in peer-reviewed journals in the last decade. to provide effective, culturally sensitive care.

Diverse group

There are 3.4 million individuals of South Asian descent in the United States. Geographically, South Asians may have familial and cultural/historical roots in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, and Pakistan.4 They enjoy a rich diversity in terms of cultural and religious beliefs, language, socioeconomic status, modes of acculturation, and immigration patterns. Asian Indians are the largest group of South Asians in the United States. They are highly educated, with a larger proportion of them pursuing an undergraduate and/or graduate level education than the general population. The median household income of Asian Indians is also higher than the national average.5

In general, suicide, like all mental health issues, is a stigmatized and taboo topic in the South Asian community.6 Also, South Asian Americans are hesitant to seek mental health care because of a perceived inability of Western health care professionals to understand their cultural views. Extrapolation from data on South Asians in the United Kingdom, aggregate statistics for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and studies on South Asians in the United States highlight two South Asian subgroups that are particularly vulnerable to suicide. These are young adults (aged 18-24 years) and women.7

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for young Asian American men in the United States. Rates of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts are higher among younger Asian Americans (aged 18-24 years) than among older Asian American adults. Young Asian American adults have been found to have higher levels of suicidal ideation than their white counterparts.8,9 Acculturation or assimilating into a different culture, familial violence as a child, hopelessness or a thought pattern with a pessimistic outlook, depression, and childhood sexual abuse have all been found to be positively correlated with suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in South Asian Americans. One study that conducted0 in-group analysis on undergraduate university students of South Asian descent living in New York found higher levels of hopelessness and depression in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans.10

In addition, higher levels of suicidal ideation are reported in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans. These results resemble findings from similar studies in the United Kingdom. A posited reason for these findings is a difference in religious beliefs. Pakistani and Bangladeshi Americans are predominantly Muslim, have stronger moral beliefs against suicide, and consider it a sin as defined by Islamic beliefs. Asian Indians, in contrast, are majority Hindu and believe in reincarnation – a context that might make suicide seem more permissible.11

South Asian women are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and/or familial violence. Cultural gender norms, traditional norms, and patriarchal ideology in the South Asian community make quantifying the level of childhood sexual abuse and familial violence a challenge. Furthermore, culturally, South Asian women are often considered subordinate relative to men, and discussion around family violence and childhood sexual abuse is avoided. Studies from the United Kingdom find a lack of knowledge around, disclosure of, and fear of reporting childhood sexual abuse in South Asian women. A study of a sample of representative South Asian American women found that 25.2% had experienced some form of childhood sexual abuse.12

Research also suggests that South Asians in the United States have some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence. Another study in the United States found that two out of five South Asian women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence. This is much higher than the rate found in representative general U.S. population samples.

Literature suggests that exposure to these factors increases womens’ risk for suicidal ideation and attempted suicide. In the United Kingdom, research on South Asian women (aged 18-24 years) has found rates of attempted suicide to be three times higher than those of their white counterparts. Research from the United Kingdom and the United States suggests that younger married South Asian women are exposed to emotional and/or physical abuse from their spouse or in-laws, which is often a mediating factor in their increased risk for suicide.

Attempts to address suicide in the South Asian American community have to be multifaceted. An ideal approach would consist of educating, and connecting with, the community through ethnic media and trusted community sources, such as primary care doctors, caregivers, and social workers. In line with established American Psychological Association guidelines on caring for individuals of immigrant origin, health care professionals should document the patient’s number of generations in the country, number of years in the country, language fluency, family and community support, educational level, social status changes related to immigration, intimate relationships with people of different backgrounds, and stress related to acculturation. Special attention should be paid to South Asian women. Health care professionals should screen South Asian women for past and current intimate partner violence, provide culturally appropriate intimate partner violence resources, and be prepared to refer them to legal counseling services. Also, South Asian women should be screened for a history of exposure to familial violence and childhood sexual abuse.1

To adequately serve this population, there is a need to build capacity in the provision of culturally appropriate mental health services. Access to mental health care professionals through settings such as shelters for abused women, South Asian community–based organizations, youth centers, college counseling, and senior centers would encourage individuals to seek care without the threat of being stigmatized.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 330. 2018 Nov.

2. Ahmad-Stout DJ and Nath SR. J College Stud Psychother. 2013 Jan 10;27(1):43-61.

3. Li H and Keshavan M. Asian J Psychiatry. 2011;4(1):1.

4. Nagaraj NC et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019 Oct;21(5):978-1003.

5. Nagaraj NC et al. J Comm Health. 2018;43(3):543-51.

6. Cao KO. Generations. 2014;30(4):82-5.

7. Hurwitz EJ et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(3):251-61.

8. Polanco-Roman L et al. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019 Dec 23. doi: 10.1037/cpd0000313.

9. Erausquin JT et al. J Youth Adolesc. 2019 Sep;48(9):1796-1805.

10. Lane R et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2016;7(2):120-8.

11. Nath SR et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2018;9(4):334-343.

12. Robertson HA et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016 Jul 31;18(4):921-7.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University (CMU) College of Medicine, Mt. Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in immigrant populations.

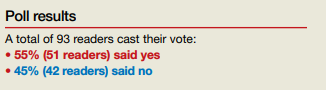

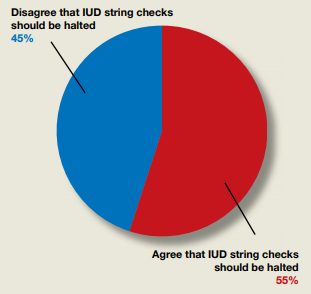

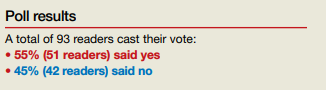

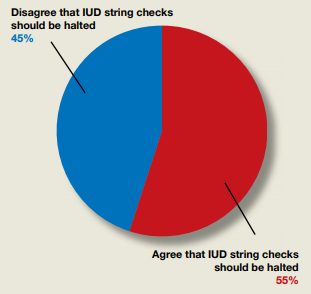

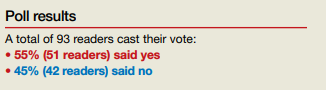

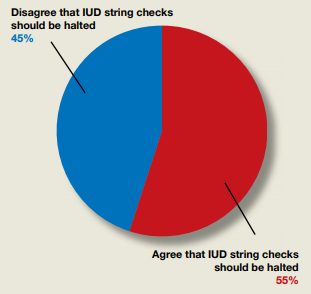

Do ObGyns agree that the practice of in-office IUD string checks should be halted?

In their Break This Practice Habit column, “The IUD string check: Benefit or burden?” (March 2020), Kathryn Fay, MD, and Lori Gawron, MD, MPH, argued that it is time to discontinue routine office visits and self-checks for IUD strings postinsertion as the practice is unsupported by data and costly. OBG Management polled readers: “Should the practice of counseling patients to present to the office for a string check after IUD insertion be halted?”

In their Break This Practice Habit column, “The IUD string check: Benefit or burden?” (March 2020), Kathryn Fay, MD, and Lori Gawron, MD, MPH, argued that it is time to discontinue routine office visits and self-checks for IUD strings postinsertion as the practice is unsupported by data and costly. OBG Management polled readers: “Should the practice of counseling patients to present to the office for a string check after IUD insertion be halted?”

In their Break This Practice Habit column, “The IUD string check: Benefit or burden?” (March 2020), Kathryn Fay, MD, and Lori Gawron, MD, MPH, argued that it is time to discontinue routine office visits and self-checks for IUD strings postinsertion as the practice is unsupported by data and costly. OBG Management polled readers: “Should the practice of counseling patients to present to the office for a string check after IUD insertion be halted?”

Fighting COVID and police brutality, medical teams take to streets to treat protesters

Amid clouds of choking tear gas, booming flash-bang grenades and other “riot control agents,” volunteer medics plunged into street protests over the past weeks to help the injured – sometimes rushing to the front lines as soon as their hospital shifts ended.

Known as “street medics,” these unorthodox teams of nursing students, veterinarians, doctors, trauma surgeons, security guards, ski patrollers, nurses, wilderness EMTs, and off-the-clock ambulance workers poured water – not milk – into the eyes of tear-gassed protesters. They stanched bleeding wounds and plucked disoriented teenagers from clouds of gas, entering dangerous corners where on-duty emergency health responders may fear to go.

So donning cloth masks to protect against the virus – plus helmets, makeshift shields and other gear to guard against rubber bullets, projectiles and tear gas – the volunteer medics organized themselves into a web of first responders to care for people on the streets. They showed up early, set up first-aid stations, established transportation networks and covered their arms, helmets and backpacks with crosses made of red duct tape, to signify that they were medics. Some stayed late into the night past curfews until every protester had left.

Iris Butler, a 21-year-old certified nursing assistant who works in a nursing home, decided to offer her skills after seeing a man injured by a rubber bullet on her first night at the Denver protests. She showed up as a medic every night thereafter. She didn’t see it as a choice.

“I am working full time and basically being at the protest after getting straight off of work,” said Butler, who is black. That’s tiring, she added, but so is being a black woman in America.

After going out as a medic on her own, she soon met other volunteers. Together they used text-message chains to organize their efforts. One night, she responded to a man who had been shot with a rubber bullet in the chest; she said his torso had turned blue and purple from the impact. She also provided aid after a shooting near the protest left someone in critical condition.

“It’s hard, but bills need to be paid and justice needs to be served,” she said.

The street medic movement traces its roots, in part, to the 1960s protests, as well as the American Indian Movement and the Black Panther Party. Denver Action Medic Network offers a 20-hour training course that prepares them to treat patients in conflicts with police and large crowds; a four-hour session is offered to medical professionals as “bridge” training.

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, the Denver Action Medic Network has added new training guidelines: Don’t go to protests if sick or in contact with those who are infected; wear a mask; give people lots of space and use hand sanitizer. Jordan Garcia, a 39-year-old medic for over 20 years who works with the network of veteran street medics, said they also warn medics about the increased risk of transmission because of protesters coughing from tear gas, and urge them to get tested for the virus after the protests.

The number of volunteer medics swelled after George Floyd’s May 25 killing in Minneapolis. In Denver alone, at least 40 people reached out to the Denver Action Medic Network for training.

On June 3, Dr. Rupa Marya, an associate professor of medicine at the University of California,San Francisco, and the co-founder of the Do No Harm Coalition, which runs street medic training in the Bay Area, hosted a national webinar attended by over 3,000 medical professionals to provide the bridge training to be a street medic. In her online bio, Marya describes the coalition as “an organization of over 450 health workers committed to structural change” in addressing health problems.

“When we see suffering, that’s where we go,” Marya said. “And right now that suffering is happening on the streets.”

In the recent Denver protests, street medics responded to major head, face and eye injuries among protesters from what are sometimes described as “kinetic impact projectiles” or “less-than-lethal” bullets shot at protesters, along with tear-gas and flash-bang stun grenade canisters that either hit them or exploded in their faces.

Garcia, who by day works for an immigrant rights nonprofit, said that these weapons are not designed to be shot directly at people.

“We’re seeing police use these less-lethal weapons in lethal ways, and that is pretty upsetting,” Garcia said about the recent protests.

Denver police Chief Paul Pazen promised to make changes, including banning chokeholds and requiring SWAT teams to turn on their body cameras. Last week, a federal judge also issued a temporary injunction to stop Denver police from using tear gas and other less-than-lethal weapons in response to a class action lawsuit, in which a medic stated he was shot multiple times by police with pepper balls while treating patients. (Last week in North Carolina police were recorded destroying medic stations.)

Denver street medic Kevin Connell, a 30-year-old emergency room nurse, said he was hit with pepper balls in the back of his medic vest – which was clearly marked by red crosses – while treating a patient. He showed up to the Denver protests every night he did not have to work, he said, wearing a Kevlar medic vest, protective goggles and a homemade gas mask fashioned from a water bottle. As a member of the Denver Action Medic Network, Connell also served at the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota in a dispute over the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“I mean, as bad as it sounds, it was only tear gas, pepper balls and rubber bullets that were being fired on us,” Connell said of his recent experience in Denver. “When I was at Standing Rock, they were using high-powered water hoses even when it was, like, freezing cold. … So I think the police here had a little bit more restraint.”

Still, first-time street medic Aj Mossman, a 31-year-old Denver emergency medical technician studying for nursing school, was shocked to be tear-gassed and struck in the back of the leg with a flash grenade while treating a protester on May 30. Mossman still has a large leg bruise.

The following night, Mossman, who uses the pronoun they, brought more protective gear, but said they are still having difficulty processing what felt like a war zone.

“I thought I understood what my black friends went through. I thought I understood what the black community went through,” said Mossman, who is white. “But I had absolutely no idea how violent the police were and how little they cared about who they hurt.”

For Butler, serving as a medic with others from various walks of life was inspiring. “They’re also out there to protect black and brown bodies. And that’s amazing,” she said. “That’s just a beautiful sight.”

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News, which is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Amid clouds of choking tear gas, booming flash-bang grenades and other “riot control agents,” volunteer medics plunged into street protests over the past weeks to help the injured – sometimes rushing to the front lines as soon as their hospital shifts ended.

Known as “street medics,” these unorthodox teams of nursing students, veterinarians, doctors, trauma surgeons, security guards, ski patrollers, nurses, wilderness EMTs, and off-the-clock ambulance workers poured water – not milk – into the eyes of tear-gassed protesters. They stanched bleeding wounds and plucked disoriented teenagers from clouds of gas, entering dangerous corners where on-duty emergency health responders may fear to go.

So donning cloth masks to protect against the virus – plus helmets, makeshift shields and other gear to guard against rubber bullets, projectiles and tear gas – the volunteer medics organized themselves into a web of first responders to care for people on the streets. They showed up early, set up first-aid stations, established transportation networks and covered their arms, helmets and backpacks with crosses made of red duct tape, to signify that they were medics. Some stayed late into the night past curfews until every protester had left.

Iris Butler, a 21-year-old certified nursing assistant who works in a nursing home, decided to offer her skills after seeing a man injured by a rubber bullet on her first night at the Denver protests. She showed up as a medic every night thereafter. She didn’t see it as a choice.

“I am working full time and basically being at the protest after getting straight off of work,” said Butler, who is black. That’s tiring, she added, but so is being a black woman in America.

After going out as a medic on her own, she soon met other volunteers. Together they used text-message chains to organize their efforts. One night, she responded to a man who had been shot with a rubber bullet in the chest; she said his torso had turned blue and purple from the impact. She also provided aid after a shooting near the protest left someone in critical condition.

“It’s hard, but bills need to be paid and justice needs to be served,” she said.

The street medic movement traces its roots, in part, to the 1960s protests, as well as the American Indian Movement and the Black Panther Party. Denver Action Medic Network offers a 20-hour training course that prepares them to treat patients in conflicts with police and large crowds; a four-hour session is offered to medical professionals as “bridge” training.

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, the Denver Action Medic Network has added new training guidelines: Don’t go to protests if sick or in contact with those who are infected; wear a mask; give people lots of space and use hand sanitizer. Jordan Garcia, a 39-year-old medic for over 20 years who works with the network of veteran street medics, said they also warn medics about the increased risk of transmission because of protesters coughing from tear gas, and urge them to get tested for the virus after the protests.

The number of volunteer medics swelled after George Floyd’s May 25 killing in Minneapolis. In Denver alone, at least 40 people reached out to the Denver Action Medic Network for training.

On June 3, Dr. Rupa Marya, an associate professor of medicine at the University of California,San Francisco, and the co-founder of the Do No Harm Coalition, which runs street medic training in the Bay Area, hosted a national webinar attended by over 3,000 medical professionals to provide the bridge training to be a street medic. In her online bio, Marya describes the coalition as “an organization of over 450 health workers committed to structural change” in addressing health problems.

“When we see suffering, that’s where we go,” Marya said. “And right now that suffering is happening on the streets.”

In the recent Denver protests, street medics responded to major head, face and eye injuries among protesters from what are sometimes described as “kinetic impact projectiles” or “less-than-lethal” bullets shot at protesters, along with tear-gas and flash-bang stun grenade canisters that either hit them or exploded in their faces.

Garcia, who by day works for an immigrant rights nonprofit, said that these weapons are not designed to be shot directly at people.

“We’re seeing police use these less-lethal weapons in lethal ways, and that is pretty upsetting,” Garcia said about the recent protests.

Denver police Chief Paul Pazen promised to make changes, including banning chokeholds and requiring SWAT teams to turn on their body cameras. Last week, a federal judge also issued a temporary injunction to stop Denver police from using tear gas and other less-than-lethal weapons in response to a class action lawsuit, in which a medic stated he was shot multiple times by police with pepper balls while treating patients. (Last week in North Carolina police were recorded destroying medic stations.)

Denver street medic Kevin Connell, a 30-year-old emergency room nurse, said he was hit with pepper balls in the back of his medic vest – which was clearly marked by red crosses – while treating a patient. He showed up to the Denver protests every night he did not have to work, he said, wearing a Kevlar medic vest, protective goggles and a homemade gas mask fashioned from a water bottle. As a member of the Denver Action Medic Network, Connell also served at the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota in a dispute over the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

“I mean, as bad as it sounds, it was only tear gas, pepper balls and rubber bullets that were being fired on us,” Connell said of his recent experience in Denver. “When I was at Standing Rock, they were using high-powered water hoses even when it was, like, freezing cold. … So I think the police here had a little bit more restraint.”

Still, first-time street medic Aj Mossman, a 31-year-old Denver emergency medical technician studying for nursing school, was shocked to be tear-gassed and struck in the back of the leg with a flash grenade while treating a protester on May 30. Mossman still has a large leg bruise.

The following night, Mossman, who uses the pronoun they, brought more protective gear, but said they are still having difficulty processing what felt like a war zone.

“I thought I understood what my black friends went through. I thought I understood what the black community went through,” said Mossman, who is white. “But I had absolutely no idea how violent the police were and how little they cared about who they hurt.”

For Butler, serving as a medic with others from various walks of life was inspiring. “They’re also out there to protect black and brown bodies. And that’s amazing,” she said. “That’s just a beautiful sight.”

This article originally appeared on Kaiser Health News, which is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Amid clouds of choking tear gas, booming flash-bang grenades and other “riot control agents,” volunteer medics plunged into street protests over the past weeks to help the injured – sometimes rushing to the front lines as soon as their hospital shifts ended.

Known as “street medics,” these unorthodox teams of nursing students, veterinarians, doctors, trauma surgeons, security guards, ski patrollers, nurses, wilderness EMTs, and off-the-clock ambulance workers poured water – not milk – into the eyes of tear-gassed protesters. They stanched bleeding wounds and plucked disoriented teenagers from clouds of gas, entering dangerous corners where on-duty emergency health responders may fear to go.

So donning cloth masks to protect against the virus – plus helmets, makeshift shields and other gear to guard against rubber bullets, projectiles and tear gas – the volunteer medics organized themselves into a web of first responders to care for people on the streets. They showed up early, set up first-aid stations, established transportation networks and covered their arms, helmets and backpacks with crosses made of red duct tape, to signify that they were medics. Some stayed late into the night past curfews until every protester had left.

Iris Butler, a 21-year-old certified nursing assistant who works in a nursing home, decided to offer her skills after seeing a man injured by a rubber bullet on her first night at the Denver protests. She showed up as a medic every night thereafter. She didn’t see it as a choice.