User login

APA, others lobby to make COVID-19 telehealth waivers permanent

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is calling on Congress to permanently lift restrictions that have allowed unfettered delivery of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic, which experts say has been a boon to patients and physicians alike.

“We ask Congress to extend the telehealth waiver authority under COVID-19 beyond the emergency and to study its impact while doing so,” said APA President Jeffrey Geller, MD, in a May 27 video briefing with congressional staff and reporters.

The APA is also seeking to make permanent certain waivers granted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services on April 30, including elimination of geographic restrictions on behavioral health and allowing patients be seen at home, said Dr. Geller.

The APA also is asking for the elimination of the rule that requires clinicians to have an initial face-to-face meeting with patients before they can prescribe controlled substances, Dr. Geller said. The Drug Enforcement Administration waived that requirement, known as the Ryan Haight Act, on March 17 for the duration of the national emergency.

Telemedicine has supporters on both sides of the aisle in Congress, including Rep. Paul Tonko (D-N.Y.) who said at the APA briefing he would fight to make the waivers permanent.

“The expanded use of telehealth has enormous potential during normal times as well, especially in behavioral health,” said Mr. Tonko. “I am pushing fiercely for these current flexibilities to be extended for a reasonable time after the public health emergency so that we can have time to evaluate which should be made permanent,” he said.

Dr. Geller, other clinicians, and advocates in the briefing praised CMS for facilitating telepsychiatry for Medicare. That follows in the footsteps of most private insurers, who have also relaxed requirements into the summer, according to the Medical Group Management Association.

Game changer

The Medicare waivers “have dramatically changed the entire scene for someone like myself as a clinician to allow me to see my patients in a much easier way,” said Peter Yellowlees, MBBS, MD, chief wellness officer, University of California Davis Health. Within 2 weeks in March, the health system converted almost all of its regular outpatient visits to telemedicine, he said.

Dr. Yellowlees added government still needs to address, what he called, outdated HIPAA regulations that ban certain technologies.

“It makes no sense that I can talk to someone on an iPhone, but the moment I talk to them on FaceTime, it’s illegal,” said Dr. Yellowlees, a former president of the American Telemedicine Association.

Dr. Geller said that “psychiatric care provided by telehealth is as effective as in-person psychiatric services,” adding that “some patients prefer telepsychiatry because of its convenience and as a means of reducing stigma associated with seeking help for mental health.”

Shabana Khan, MD, a child psychiatrist and director of telepsychiatry at New York University Langone Health, said audio and video conferencing are helping address a shortage and maldistribution of child and adolescent psychiatrists.

Americans’ mental health is suffering during the pandemic. The U.S. Census Bureau recently released data showing that half of those surveyed reported depressed mood and that one-third are reporting anxiety, depression, or both, as reported by the Washington Post.

“At this very time that anxiety, depression, substance use, and other mental health problems are rising, our nation’s already strained mental health system is really being pushed to the brink,” said Jodi Kwarciany, manager for mental health policy for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, during the briefing.

Telemedicine can help “by connecting people to providers at the time and the place and using the technology that works best for them,” she said, adding that NAMI would press policymakers to address barriers to access.

The clinicians on the briefing said they’ve observed that some patients are more comfortable with video or audio interactions than with in-person visits.

Increased access to care

Telepsychiatry seems to be convincing some to reconsider therapy, since they can do it at home, said Dr. Yellowlees. he said.

For instance, he said, he has been able to consult by phone and video with several patients who receive care through the Indian Health Service who had not be able to get into the physical clinic.

Dr. Yellowlees said video sessions also may encourage patients to be more, not less, talkative. “Video is actually counterintuitively a very intimate experience,” he said, in part because of the perceived distance and people’s tendency to be less inhibited on technology platforms.“It’s less embarrassing,” he said. “If you’ve got really dramatic, difficult, traumatic things to talk about, it’s slightly easier to talk to someone who’s slightly further apart from you on video,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

“Individuals who have a significant amount of anxiety may actually feel more comfortable with the distance that this technology affords,” agreed Dr. Khan. She said telemedicine had made sessions more comfortable for some of her patients with autism spectrum disorder.

Dr. Geller said audio and video have been important to his practice during the pandemic. One of his patients never leaves the house and does not use computers. “He spends his time sequestered at home listening to records on his record player,” said Dr. Geller. But he’s been amenable to phone sessions. “What I’ve found with him, and I’ve found with several other patients, is that they actually talk more easily when they’re not face to face,” he said.

Far fewer no-shows

Another plus for his New England–based practice during the last few months: patients have not been anxious about missing sessions because of the weather. The clinicians all noted that telepsychiatry seemed to reduce missed visits.

Dr. Yellowlees said that no-show rates had decreased by half at UC Davis. “That means no significant loss of income,” during the pandemic, he said.

“The no-show rate is incredibly low, particularly because when you call the patients and they don’t remember they had an appointment, you have the appointment anyway, most of the time,” said Dr. Geller.

For Dr. Khan, being able to conduct audio and video sessions during the pandemic has meant keeping up continuity of care.

As a result of the pandemic, many college students in New York City had to go home – often to another state. The waivers granted by New York’s Medicaid program and other insurers have allowed Dr. Khan to continue care for these patients.

The NYU clinic also operates day programs in rural areas 5 hours from the city. Dr. Khan recently evaluated a 12-year-old girl with significant anxiety and low mood, both of which had worsened.

“She would not have been able to access care otherwise,” said Dr. Khan. And for rural patients who do not have access to broadband or smartphones, audio visits “have been immensely helpful,” she said.

Dr. Khan, Dr. Geller, and Dr. Yellowlees have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is calling on Congress to permanently lift restrictions that have allowed unfettered delivery of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic, which experts say has been a boon to patients and physicians alike.

“We ask Congress to extend the telehealth waiver authority under COVID-19 beyond the emergency and to study its impact while doing so,” said APA President Jeffrey Geller, MD, in a May 27 video briefing with congressional staff and reporters.

The APA is also seeking to make permanent certain waivers granted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services on April 30, including elimination of geographic restrictions on behavioral health and allowing patients be seen at home, said Dr. Geller.

The APA also is asking for the elimination of the rule that requires clinicians to have an initial face-to-face meeting with patients before they can prescribe controlled substances, Dr. Geller said. The Drug Enforcement Administration waived that requirement, known as the Ryan Haight Act, on March 17 for the duration of the national emergency.

Telemedicine has supporters on both sides of the aisle in Congress, including Rep. Paul Tonko (D-N.Y.) who said at the APA briefing he would fight to make the waivers permanent.

“The expanded use of telehealth has enormous potential during normal times as well, especially in behavioral health,” said Mr. Tonko. “I am pushing fiercely for these current flexibilities to be extended for a reasonable time after the public health emergency so that we can have time to evaluate which should be made permanent,” he said.

Dr. Geller, other clinicians, and advocates in the briefing praised CMS for facilitating telepsychiatry for Medicare. That follows in the footsteps of most private insurers, who have also relaxed requirements into the summer, according to the Medical Group Management Association.

Game changer

The Medicare waivers “have dramatically changed the entire scene for someone like myself as a clinician to allow me to see my patients in a much easier way,” said Peter Yellowlees, MBBS, MD, chief wellness officer, University of California Davis Health. Within 2 weeks in March, the health system converted almost all of its regular outpatient visits to telemedicine, he said.

Dr. Yellowlees added government still needs to address, what he called, outdated HIPAA regulations that ban certain technologies.

“It makes no sense that I can talk to someone on an iPhone, but the moment I talk to them on FaceTime, it’s illegal,” said Dr. Yellowlees, a former president of the American Telemedicine Association.

Dr. Geller said that “psychiatric care provided by telehealth is as effective as in-person psychiatric services,” adding that “some patients prefer telepsychiatry because of its convenience and as a means of reducing stigma associated with seeking help for mental health.”

Shabana Khan, MD, a child psychiatrist and director of telepsychiatry at New York University Langone Health, said audio and video conferencing are helping address a shortage and maldistribution of child and adolescent psychiatrists.

Americans’ mental health is suffering during the pandemic. The U.S. Census Bureau recently released data showing that half of those surveyed reported depressed mood and that one-third are reporting anxiety, depression, or both, as reported by the Washington Post.

“At this very time that anxiety, depression, substance use, and other mental health problems are rising, our nation’s already strained mental health system is really being pushed to the brink,” said Jodi Kwarciany, manager for mental health policy for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, during the briefing.

Telemedicine can help “by connecting people to providers at the time and the place and using the technology that works best for them,” she said, adding that NAMI would press policymakers to address barriers to access.

The clinicians on the briefing said they’ve observed that some patients are more comfortable with video or audio interactions than with in-person visits.

Increased access to care

Telepsychiatry seems to be convincing some to reconsider therapy, since they can do it at home, said Dr. Yellowlees. he said.

For instance, he said, he has been able to consult by phone and video with several patients who receive care through the Indian Health Service who had not be able to get into the physical clinic.

Dr. Yellowlees said video sessions also may encourage patients to be more, not less, talkative. “Video is actually counterintuitively a very intimate experience,” he said, in part because of the perceived distance and people’s tendency to be less inhibited on technology platforms.“It’s less embarrassing,” he said. “If you’ve got really dramatic, difficult, traumatic things to talk about, it’s slightly easier to talk to someone who’s slightly further apart from you on video,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

“Individuals who have a significant amount of anxiety may actually feel more comfortable with the distance that this technology affords,” agreed Dr. Khan. She said telemedicine had made sessions more comfortable for some of her patients with autism spectrum disorder.

Dr. Geller said audio and video have been important to his practice during the pandemic. One of his patients never leaves the house and does not use computers. “He spends his time sequestered at home listening to records on his record player,” said Dr. Geller. But he’s been amenable to phone sessions. “What I’ve found with him, and I’ve found with several other patients, is that they actually talk more easily when they’re not face to face,” he said.

Far fewer no-shows

Another plus for his New England–based practice during the last few months: patients have not been anxious about missing sessions because of the weather. The clinicians all noted that telepsychiatry seemed to reduce missed visits.

Dr. Yellowlees said that no-show rates had decreased by half at UC Davis. “That means no significant loss of income,” during the pandemic, he said.

“The no-show rate is incredibly low, particularly because when you call the patients and they don’t remember they had an appointment, you have the appointment anyway, most of the time,” said Dr. Geller.

For Dr. Khan, being able to conduct audio and video sessions during the pandemic has meant keeping up continuity of care.

As a result of the pandemic, many college students in New York City had to go home – often to another state. The waivers granted by New York’s Medicaid program and other insurers have allowed Dr. Khan to continue care for these patients.

The NYU clinic also operates day programs in rural areas 5 hours from the city. Dr. Khan recently evaluated a 12-year-old girl with significant anxiety and low mood, both of which had worsened.

“She would not have been able to access care otherwise,” said Dr. Khan. And for rural patients who do not have access to broadband or smartphones, audio visits “have been immensely helpful,” she said.

Dr. Khan, Dr. Geller, and Dr. Yellowlees have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is calling on Congress to permanently lift restrictions that have allowed unfettered delivery of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic, which experts say has been a boon to patients and physicians alike.

“We ask Congress to extend the telehealth waiver authority under COVID-19 beyond the emergency and to study its impact while doing so,” said APA President Jeffrey Geller, MD, in a May 27 video briefing with congressional staff and reporters.

The APA is also seeking to make permanent certain waivers granted by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services on April 30, including elimination of geographic restrictions on behavioral health and allowing patients be seen at home, said Dr. Geller.

The APA also is asking for the elimination of the rule that requires clinicians to have an initial face-to-face meeting with patients before they can prescribe controlled substances, Dr. Geller said. The Drug Enforcement Administration waived that requirement, known as the Ryan Haight Act, on March 17 for the duration of the national emergency.

Telemedicine has supporters on both sides of the aisle in Congress, including Rep. Paul Tonko (D-N.Y.) who said at the APA briefing he would fight to make the waivers permanent.

“The expanded use of telehealth has enormous potential during normal times as well, especially in behavioral health,” said Mr. Tonko. “I am pushing fiercely for these current flexibilities to be extended for a reasonable time after the public health emergency so that we can have time to evaluate which should be made permanent,” he said.

Dr. Geller, other clinicians, and advocates in the briefing praised CMS for facilitating telepsychiatry for Medicare. That follows in the footsteps of most private insurers, who have also relaxed requirements into the summer, according to the Medical Group Management Association.

Game changer

The Medicare waivers “have dramatically changed the entire scene for someone like myself as a clinician to allow me to see my patients in a much easier way,” said Peter Yellowlees, MBBS, MD, chief wellness officer, University of California Davis Health. Within 2 weeks in March, the health system converted almost all of its regular outpatient visits to telemedicine, he said.

Dr. Yellowlees added government still needs to address, what he called, outdated HIPAA regulations that ban certain technologies.

“It makes no sense that I can talk to someone on an iPhone, but the moment I talk to them on FaceTime, it’s illegal,” said Dr. Yellowlees, a former president of the American Telemedicine Association.

Dr. Geller said that “psychiatric care provided by telehealth is as effective as in-person psychiatric services,” adding that “some patients prefer telepsychiatry because of its convenience and as a means of reducing stigma associated with seeking help for mental health.”

Shabana Khan, MD, a child psychiatrist and director of telepsychiatry at New York University Langone Health, said audio and video conferencing are helping address a shortage and maldistribution of child and adolescent psychiatrists.

Americans’ mental health is suffering during the pandemic. The U.S. Census Bureau recently released data showing that half of those surveyed reported depressed mood and that one-third are reporting anxiety, depression, or both, as reported by the Washington Post.

“At this very time that anxiety, depression, substance use, and other mental health problems are rising, our nation’s already strained mental health system is really being pushed to the brink,” said Jodi Kwarciany, manager for mental health policy for the National Alliance on Mental Illness, during the briefing.

Telemedicine can help “by connecting people to providers at the time and the place and using the technology that works best for them,” she said, adding that NAMI would press policymakers to address barriers to access.

The clinicians on the briefing said they’ve observed that some patients are more comfortable with video or audio interactions than with in-person visits.

Increased access to care

Telepsychiatry seems to be convincing some to reconsider therapy, since they can do it at home, said Dr. Yellowlees. he said.

For instance, he said, he has been able to consult by phone and video with several patients who receive care through the Indian Health Service who had not be able to get into the physical clinic.

Dr. Yellowlees said video sessions also may encourage patients to be more, not less, talkative. “Video is actually counterintuitively a very intimate experience,” he said, in part because of the perceived distance and people’s tendency to be less inhibited on technology platforms.“It’s less embarrassing,” he said. “If you’ve got really dramatic, difficult, traumatic things to talk about, it’s slightly easier to talk to someone who’s slightly further apart from you on video,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

“Individuals who have a significant amount of anxiety may actually feel more comfortable with the distance that this technology affords,” agreed Dr. Khan. She said telemedicine had made sessions more comfortable for some of her patients with autism spectrum disorder.

Dr. Geller said audio and video have been important to his practice during the pandemic. One of his patients never leaves the house and does not use computers. “He spends his time sequestered at home listening to records on his record player,” said Dr. Geller. But he’s been amenable to phone sessions. “What I’ve found with him, and I’ve found with several other patients, is that they actually talk more easily when they’re not face to face,” he said.

Far fewer no-shows

Another plus for his New England–based practice during the last few months: patients have not been anxious about missing sessions because of the weather. The clinicians all noted that telepsychiatry seemed to reduce missed visits.

Dr. Yellowlees said that no-show rates had decreased by half at UC Davis. “That means no significant loss of income,” during the pandemic, he said.

“The no-show rate is incredibly low, particularly because when you call the patients and they don’t remember they had an appointment, you have the appointment anyway, most of the time,” said Dr. Geller.

For Dr. Khan, being able to conduct audio and video sessions during the pandemic has meant keeping up continuity of care.

As a result of the pandemic, many college students in New York City had to go home – often to another state. The waivers granted by New York’s Medicaid program and other insurers have allowed Dr. Khan to continue care for these patients.

The NYU clinic also operates day programs in rural areas 5 hours from the city. Dr. Khan recently evaluated a 12-year-old girl with significant anxiety and low mood, both of which had worsened.

“She would not have been able to access care otherwise,” said Dr. Khan. And for rural patients who do not have access to broadband or smartphones, audio visits “have been immensely helpful,” she said.

Dr. Khan, Dr. Geller, and Dr. Yellowlees have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Loss-frame’ approach makes psoriasis patients more agreeable to treatment

, held virtually.

“We typically explain to patients the benefits of treatment,” Ari A. Kassardjian, BS, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in his presentation. “However, explaining to them the harmful effects on their skin and joint diseases, such as exacerbation of psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis, could offer some patients a new perspective that may influence their treatment preferences; and ultimately, better communication may lead to better medication adherence in patients.”

In the study he presented, explaining to patients possible outcomes without treatment was more effective in getting them to agree to treatment than was messaging that focused on the positive effects of a therapy (reducing disease severity and pain, and improved health).

He noted that the impact of framing choices in terms of gain or loss on decision-making has been measured in other areas of medicine, including in patients with multiple sclerosis where medication adherence is an issue (J Health Commun. 2017 Jun;22[6]:523-31). “Gain-framed” messages focus on the benefits of taking a medication, while “loss-framed” messages highlight the potential consequences of not agreeing or adhering to treatment.

In the study, Mr. Kassardjian and coinvestigators evaluated 90 patients with psoriasis who were randomized to receive a gain-framed or loss-framed message about a hypothetical new biologic injectable medication for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). More than half were male (64.4%), white (53.3%), and non-Hispanic or Latino (55.6%); and about one-fourth of the participants (27.8%) also had psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

The gain-framed message emphasized “the chance to reduce psoriasis severity, reduce joint pain, and improve how you feel overall,” while the loss-framed message described the downsides of not taking medication – missing out “on the chance to improve your skin, your joints, and your overall health,” with the possibility that psoriasis may get worse, “with worsening pain in your joints from psoriatic arthritis,” and feeling “worse overall.” Both messages included the side effects of the theoretical injectable, a small risk of injection-site pain and skin infections. After receiving the message, participants ranked their likelihood of taking the medication on an 11-point Likert scale, with a score of 0 indicating that they would “definitely” not use the medication and a score of 10 indicating that they would “definitely” use the medication.

Scores among those who received the loss-framed message were a mean of 8.84, compared with 7.11 among patients who received the gain-framed message (between-group difference; 1.73; P less than .0001). When comparing patients with and without PsA, the between-group difference was 1.90 for patients with PsA (P less than .0001) and 1.08 for patients who did not have PsA (P = .002). Comparing the responses of those with PsA and those without PsA, the between-group difference was 1.08 (P = .03). While PsA and non-PsA patients favored the loss-framed messages, “regardless of the framing type, PsA patients always responded with a greater preference for the therapy,” Mr. Kassardjian said.

Gender also had an effect on responsiveness to gain-framed or loss-framed messaging. Both men and women ranked the loss-framed messaging as making them more likely to use the medication, but the between-group difference for women (2.00; P = .008) was higher than in men (1.49; P = .003). However, the total men compared with total women between-group differences were not significant.

“In clinical practice, physicians regularly weigh the benefits and risks of treatment. In order to communicate this information to patients, it is important to understand how framing these benefits and risks impacts patient preferences for therapy,” Mr. Kassardjian said. “While most available biologics are effective and have tolerable safety profiles, many psoriasis patients may be hesitant to initiate these therapies. Thus, it is important to convey the benefits and risks of these systemic agents in ways that resonate with patients.”

Mr. Kassardjian reports receiving the Dean’s Research Scholarship at the University of Southern California, funded by the Wright Foundation at the time of the study. Senior author April Armstrong, MD, disclosed serving as an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, BMS, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Modernizing Medicine, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB.

SOURCE: Kassardjian A. SID 2020, Abstract 489.

, held virtually.

“We typically explain to patients the benefits of treatment,” Ari A. Kassardjian, BS, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in his presentation. “However, explaining to them the harmful effects on their skin and joint diseases, such as exacerbation of psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis, could offer some patients a new perspective that may influence their treatment preferences; and ultimately, better communication may lead to better medication adherence in patients.”

In the study he presented, explaining to patients possible outcomes without treatment was more effective in getting them to agree to treatment than was messaging that focused on the positive effects of a therapy (reducing disease severity and pain, and improved health).

He noted that the impact of framing choices in terms of gain or loss on decision-making has been measured in other areas of medicine, including in patients with multiple sclerosis where medication adherence is an issue (J Health Commun. 2017 Jun;22[6]:523-31). “Gain-framed” messages focus on the benefits of taking a medication, while “loss-framed” messages highlight the potential consequences of not agreeing or adhering to treatment.

In the study, Mr. Kassardjian and coinvestigators evaluated 90 patients with psoriasis who were randomized to receive a gain-framed or loss-framed message about a hypothetical new biologic injectable medication for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). More than half were male (64.4%), white (53.3%), and non-Hispanic or Latino (55.6%); and about one-fourth of the participants (27.8%) also had psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

The gain-framed message emphasized “the chance to reduce psoriasis severity, reduce joint pain, and improve how you feel overall,” while the loss-framed message described the downsides of not taking medication – missing out “on the chance to improve your skin, your joints, and your overall health,” with the possibility that psoriasis may get worse, “with worsening pain in your joints from psoriatic arthritis,” and feeling “worse overall.” Both messages included the side effects of the theoretical injectable, a small risk of injection-site pain and skin infections. After receiving the message, participants ranked their likelihood of taking the medication on an 11-point Likert scale, with a score of 0 indicating that they would “definitely” not use the medication and a score of 10 indicating that they would “definitely” use the medication.

Scores among those who received the loss-framed message were a mean of 8.84, compared with 7.11 among patients who received the gain-framed message (between-group difference; 1.73; P less than .0001). When comparing patients with and without PsA, the between-group difference was 1.90 for patients with PsA (P less than .0001) and 1.08 for patients who did not have PsA (P = .002). Comparing the responses of those with PsA and those without PsA, the between-group difference was 1.08 (P = .03). While PsA and non-PsA patients favored the loss-framed messages, “regardless of the framing type, PsA patients always responded with a greater preference for the therapy,” Mr. Kassardjian said.

Gender also had an effect on responsiveness to gain-framed or loss-framed messaging. Both men and women ranked the loss-framed messaging as making them more likely to use the medication, but the between-group difference for women (2.00; P = .008) was higher than in men (1.49; P = .003). However, the total men compared with total women between-group differences were not significant.

“In clinical practice, physicians regularly weigh the benefits and risks of treatment. In order to communicate this information to patients, it is important to understand how framing these benefits and risks impacts patient preferences for therapy,” Mr. Kassardjian said. “While most available biologics are effective and have tolerable safety profiles, many psoriasis patients may be hesitant to initiate these therapies. Thus, it is important to convey the benefits and risks of these systemic agents in ways that resonate with patients.”

Mr. Kassardjian reports receiving the Dean’s Research Scholarship at the University of Southern California, funded by the Wright Foundation at the time of the study. Senior author April Armstrong, MD, disclosed serving as an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, BMS, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Modernizing Medicine, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB.

SOURCE: Kassardjian A. SID 2020, Abstract 489.

, held virtually.

“We typically explain to patients the benefits of treatment,” Ari A. Kassardjian, BS, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in his presentation. “However, explaining to them the harmful effects on their skin and joint diseases, such as exacerbation of psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis, could offer some patients a new perspective that may influence their treatment preferences; and ultimately, better communication may lead to better medication adherence in patients.”

In the study he presented, explaining to patients possible outcomes without treatment was more effective in getting them to agree to treatment than was messaging that focused on the positive effects of a therapy (reducing disease severity and pain, and improved health).

He noted that the impact of framing choices in terms of gain or loss on decision-making has been measured in other areas of medicine, including in patients with multiple sclerosis where medication adherence is an issue (J Health Commun. 2017 Jun;22[6]:523-31). “Gain-framed” messages focus on the benefits of taking a medication, while “loss-framed” messages highlight the potential consequences of not agreeing or adhering to treatment.

In the study, Mr. Kassardjian and coinvestigators evaluated 90 patients with psoriasis who were randomized to receive a gain-framed or loss-framed message about a hypothetical new biologic injectable medication for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). More than half were male (64.4%), white (53.3%), and non-Hispanic or Latino (55.6%); and about one-fourth of the participants (27.8%) also had psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

The gain-framed message emphasized “the chance to reduce psoriasis severity, reduce joint pain, and improve how you feel overall,” while the loss-framed message described the downsides of not taking medication – missing out “on the chance to improve your skin, your joints, and your overall health,” with the possibility that psoriasis may get worse, “with worsening pain in your joints from psoriatic arthritis,” and feeling “worse overall.” Both messages included the side effects of the theoretical injectable, a small risk of injection-site pain and skin infections. After receiving the message, participants ranked their likelihood of taking the medication on an 11-point Likert scale, with a score of 0 indicating that they would “definitely” not use the medication and a score of 10 indicating that they would “definitely” use the medication.

Scores among those who received the loss-framed message were a mean of 8.84, compared with 7.11 among patients who received the gain-framed message (between-group difference; 1.73; P less than .0001). When comparing patients with and without PsA, the between-group difference was 1.90 for patients with PsA (P less than .0001) and 1.08 for patients who did not have PsA (P = .002). Comparing the responses of those with PsA and those without PsA, the between-group difference was 1.08 (P = .03). While PsA and non-PsA patients favored the loss-framed messages, “regardless of the framing type, PsA patients always responded with a greater preference for the therapy,” Mr. Kassardjian said.

Gender also had an effect on responsiveness to gain-framed or loss-framed messaging. Both men and women ranked the loss-framed messaging as making them more likely to use the medication, but the between-group difference for women (2.00; P = .008) was higher than in men (1.49; P = .003). However, the total men compared with total women between-group differences were not significant.

“In clinical practice, physicians regularly weigh the benefits and risks of treatment. In order to communicate this information to patients, it is important to understand how framing these benefits and risks impacts patient preferences for therapy,” Mr. Kassardjian said. “While most available biologics are effective and have tolerable safety profiles, many psoriasis patients may be hesitant to initiate these therapies. Thus, it is important to convey the benefits and risks of these systemic agents in ways that resonate with patients.”

Mr. Kassardjian reports receiving the Dean’s Research Scholarship at the University of Southern California, funded by the Wright Foundation at the time of the study. Senior author April Armstrong, MD, disclosed serving as an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, BMS, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Modernizing Medicine, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB.

SOURCE: Kassardjian A. SID 2020, Abstract 489.

FROM SID 2020

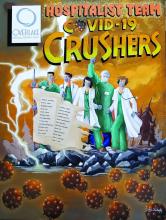

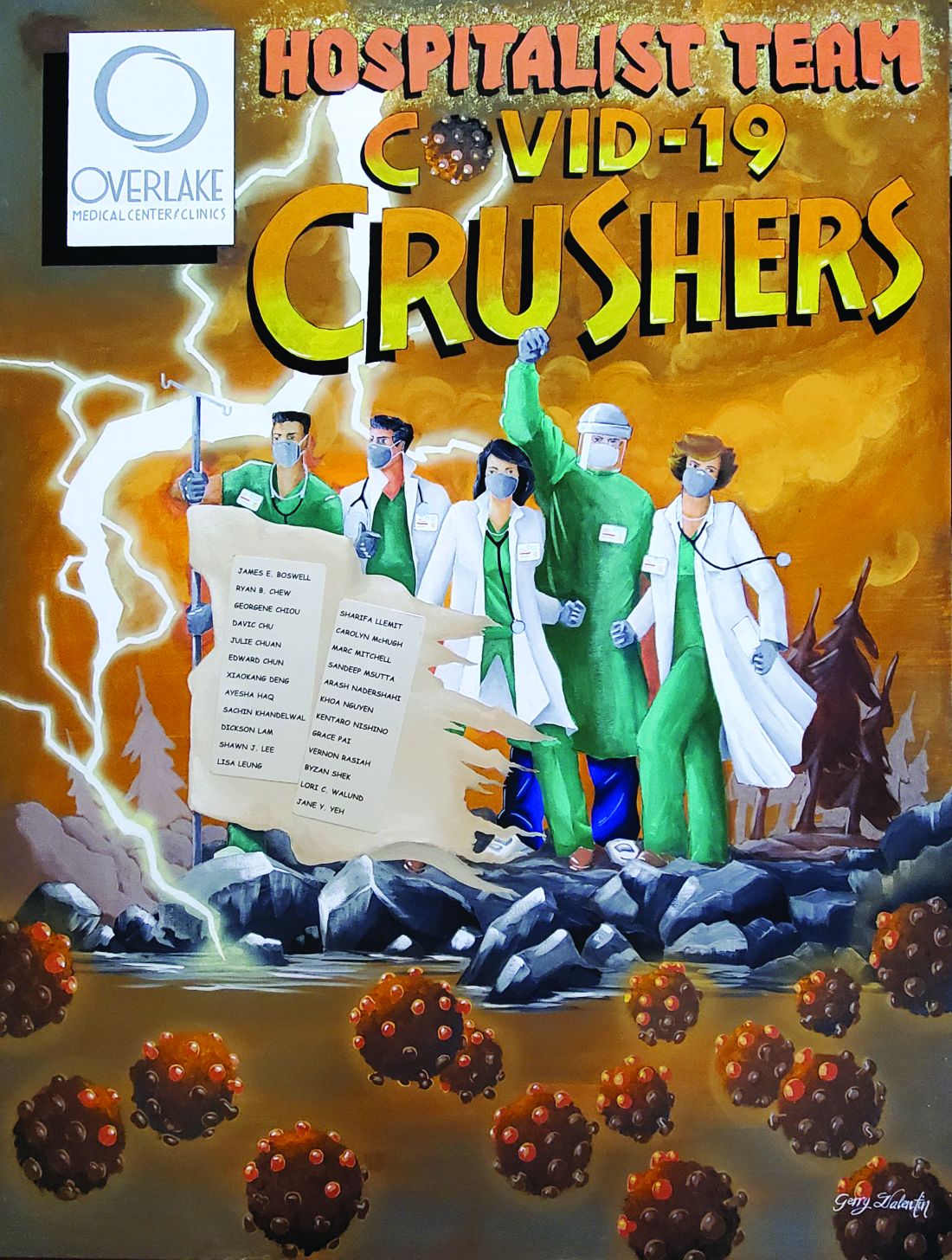

COVID-19 crushers: An appreciation of hospitalists

The hospitalist team at Overlake Medical Center and Clinics in Bellevue, Wash., has been a major partner of our Clinical Documentation Integrity Department in achieving its goal of accurately capturing the quality care patients receive on their records.

For many years, we have been witnesses of our hospitalists’ hard work, and the unique challenges of this pandemic further showed their tenacity and resilience. I thought that the best way to tell this story is through the poster accompanying this article.

To the viewer, this demonstrates the fierce battle raging between our hospitalists and the invisible foe, COVID-19. To my hospitalist colleagues, this is a constant reminder, albeit visually, that you are appreciated, admired and valued – not only by the CDI Department but by the whole organization as well.

Beyond my local colleagues, I would like to also thank the hospitalists working around the globe for their dedication and resolve in fighting this pandemic.

Mr. Valentin is a nurse and Certified Clinical Documentation Integrity Specialist at Overlake Medical Center and Clinics, Bellevue, Wash. His clinical specialties within nursing practice are in the OR, acute inpatient psychiatry, and the AIDS Unit.

The hospitalist team at Overlake Medical Center and Clinics in Bellevue, Wash., has been a major partner of our Clinical Documentation Integrity Department in achieving its goal of accurately capturing the quality care patients receive on their records.

For many years, we have been witnesses of our hospitalists’ hard work, and the unique challenges of this pandemic further showed their tenacity and resilience. I thought that the best way to tell this story is through the poster accompanying this article.

To the viewer, this demonstrates the fierce battle raging between our hospitalists and the invisible foe, COVID-19. To my hospitalist colleagues, this is a constant reminder, albeit visually, that you are appreciated, admired and valued – not only by the CDI Department but by the whole organization as well.

Beyond my local colleagues, I would like to also thank the hospitalists working around the globe for their dedication and resolve in fighting this pandemic.

Mr. Valentin is a nurse and Certified Clinical Documentation Integrity Specialist at Overlake Medical Center and Clinics, Bellevue, Wash. His clinical specialties within nursing practice are in the OR, acute inpatient psychiatry, and the AIDS Unit.

The hospitalist team at Overlake Medical Center and Clinics in Bellevue, Wash., has been a major partner of our Clinical Documentation Integrity Department in achieving its goal of accurately capturing the quality care patients receive on their records.

For many years, we have been witnesses of our hospitalists’ hard work, and the unique challenges of this pandemic further showed their tenacity and resilience. I thought that the best way to tell this story is through the poster accompanying this article.

To the viewer, this demonstrates the fierce battle raging between our hospitalists and the invisible foe, COVID-19. To my hospitalist colleagues, this is a constant reminder, albeit visually, that you are appreciated, admired and valued – not only by the CDI Department but by the whole organization as well.

Beyond my local colleagues, I would like to also thank the hospitalists working around the globe for their dedication and resolve in fighting this pandemic.

Mr. Valentin is a nurse and Certified Clinical Documentation Integrity Specialist at Overlake Medical Center and Clinics, Bellevue, Wash. His clinical specialties within nursing practice are in the OR, acute inpatient psychiatry, and the AIDS Unit.

COVID-19 may increase risk of preterm birth and cesarean delivery

Among 57 hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection who underwent vaginal or cesarean delivery, 7 had spontaneous preterm or respiratory-indicated preterm delivery, a rate of 12%, according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. For comparison, 7% of patients had preterm delivery in 2019, researchers reported “We also noted a high cesarean delivery rate in the study population (39% vs. 27% in the same area in 2019), mainly as a result of maternal respiratory-indicated urgent delivery,” wrote Valeria M. Savasi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan and Luigi Sacco Hospital, also in Milan, and colleagues.

Data do not indicate that pregnant women are more susceptible to severe COVID-19 infection, nor have studies suggested an increased risk of miscarriage, congenital anomalies, or early pregnancy loss in pregnant patients with COVID-19, the authors wrote. Studies have described an increased risk of preterm birth, however.

To study clinical features of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential factors associated with severe disease and iatrogenic delivery, Dr. Savasi and colleagues conducted a prospective study of 77 women with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were admitted during pregnancy or the immediate postpartum period in 12 maternity hospitals in northern Italy between Feb. 23 and March 28, 2020.

The investigators classified patients as having severe disease if they underwent urgent delivery based on maternal respiratory function or if they were admitted to an ICU or subintensive care department. In all, 14 patients (18%) were classified as having severe disease.

“Three patients were intubated after emergency cesarean delivery performed for maternal deterioration, and one patient underwent extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,” Dr. Savasi and colleagues reported. The results are consistent with epidemiologic data in the nonpregnant population with COVID-19 disease.

Of 11 patients with severe disease who underwent urgent delivery for respiratory compromise, 6 had significant postpartum improvement in clinical conditions. No maternal deaths occurred.

“Increased BMI [body mass index] was a significant risk factor for severe disease,” Dr. Savasi and colleagues wrote. “Fever and dyspnea on admission were symptoms significantly associated with subsequent severe maternal respiratory deterioration.”

Most patients (65%) were admitted during the third trimester, and 20 patients were still pregnant at discharge.

“Nine newborns were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit,” the authors wrote. “Interestingly, besides prematurity, fetal oxygenation and well-being at delivery were not apparently affected by the maternal acute conditions.” Three newborns with vaginal delivery and one with cesarean delivery tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The newborns may have been infected after delivery, Dr. Savasi and colleagues added. For all newborns, rooming-in and breastfeeding were performed, and none developed respiratory symptoms.

Criteria for hospital admission and therapeutic protocols may have varied between hospitals, the authors noted. In addition, the study included 12 patients who were asymptomatic and admitted for obstetric indications. These patients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 because of contact with an infected individual. Most patients were symptomatic, however, which explains the high rate of maternal severe outcomes. Hospitals have since adopted a universal SARS-CoV-2 screening policy for hospitalized pregnant patients.

Kristina Adams Waldorf, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle, commented in an interview that Savasi et al. describe one of the larger COVID-19 in pregnancy cohorts to date with rates of severe disease and delivery for respiratory compromise, which is remarkably similar to Washington state (severe disease, 18% vs. nearly 15%; delivery for respiratory compromise, 16% vs. 20%). As in Washington state, Italian women with a higher prepregnancy BMI were overrepresented in the severe disease group.

“Data are beginning to emerge that identify women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy as a high risk group for developing severe COVID-19. These data are similar to known associations between obesity and critical illness in pregnancy during the 2009 ‘swine flu’ (influenza A virus, H1N1) pandemic,” she said.

“This study and others indicate that the late second and third trimesters may be a time when women are more likely to be symptomatic from COVID-19. It remains unclear if women in the first trimester are protected from severe COVID-19 outcomes or have outcomes similar to nonpregnant women,” concluded Dr. Waldorf.

One study author disclosed receiving funds from Lo Li Pharma and Zambongroup. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Waldorf said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Savasi VM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 May 19. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003979.

Among 57 hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection who underwent vaginal or cesarean delivery, 7 had spontaneous preterm or respiratory-indicated preterm delivery, a rate of 12%, according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. For comparison, 7% of patients had preterm delivery in 2019, researchers reported “We also noted a high cesarean delivery rate in the study population (39% vs. 27% in the same area in 2019), mainly as a result of maternal respiratory-indicated urgent delivery,” wrote Valeria M. Savasi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan and Luigi Sacco Hospital, also in Milan, and colleagues.

Data do not indicate that pregnant women are more susceptible to severe COVID-19 infection, nor have studies suggested an increased risk of miscarriage, congenital anomalies, or early pregnancy loss in pregnant patients with COVID-19, the authors wrote. Studies have described an increased risk of preterm birth, however.

To study clinical features of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential factors associated with severe disease and iatrogenic delivery, Dr. Savasi and colleagues conducted a prospective study of 77 women with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were admitted during pregnancy or the immediate postpartum period in 12 maternity hospitals in northern Italy between Feb. 23 and March 28, 2020.

The investigators classified patients as having severe disease if they underwent urgent delivery based on maternal respiratory function or if they were admitted to an ICU or subintensive care department. In all, 14 patients (18%) were classified as having severe disease.

“Three patients were intubated after emergency cesarean delivery performed for maternal deterioration, and one patient underwent extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,” Dr. Savasi and colleagues reported. The results are consistent with epidemiologic data in the nonpregnant population with COVID-19 disease.

Of 11 patients with severe disease who underwent urgent delivery for respiratory compromise, 6 had significant postpartum improvement in clinical conditions. No maternal deaths occurred.

“Increased BMI [body mass index] was a significant risk factor for severe disease,” Dr. Savasi and colleagues wrote. “Fever and dyspnea on admission were symptoms significantly associated with subsequent severe maternal respiratory deterioration.”

Most patients (65%) were admitted during the third trimester, and 20 patients were still pregnant at discharge.

“Nine newborns were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit,” the authors wrote. “Interestingly, besides prematurity, fetal oxygenation and well-being at delivery were not apparently affected by the maternal acute conditions.” Three newborns with vaginal delivery and one with cesarean delivery tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The newborns may have been infected after delivery, Dr. Savasi and colleagues added. For all newborns, rooming-in and breastfeeding were performed, and none developed respiratory symptoms.

Criteria for hospital admission and therapeutic protocols may have varied between hospitals, the authors noted. In addition, the study included 12 patients who were asymptomatic and admitted for obstetric indications. These patients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 because of contact with an infected individual. Most patients were symptomatic, however, which explains the high rate of maternal severe outcomes. Hospitals have since adopted a universal SARS-CoV-2 screening policy for hospitalized pregnant patients.

Kristina Adams Waldorf, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle, commented in an interview that Savasi et al. describe one of the larger COVID-19 in pregnancy cohorts to date with rates of severe disease and delivery for respiratory compromise, which is remarkably similar to Washington state (severe disease, 18% vs. nearly 15%; delivery for respiratory compromise, 16% vs. 20%). As in Washington state, Italian women with a higher prepregnancy BMI were overrepresented in the severe disease group.

“Data are beginning to emerge that identify women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy as a high risk group for developing severe COVID-19. These data are similar to known associations between obesity and critical illness in pregnancy during the 2009 ‘swine flu’ (influenza A virus, H1N1) pandemic,” she said.

“This study and others indicate that the late second and third trimesters may be a time when women are more likely to be symptomatic from COVID-19. It remains unclear if women in the first trimester are protected from severe COVID-19 outcomes or have outcomes similar to nonpregnant women,” concluded Dr. Waldorf.

One study author disclosed receiving funds from Lo Li Pharma and Zambongroup. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Waldorf said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Savasi VM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 May 19. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003979.

Among 57 hospitalized patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection who underwent vaginal or cesarean delivery, 7 had spontaneous preterm or respiratory-indicated preterm delivery, a rate of 12%, according to a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. For comparison, 7% of patients had preterm delivery in 2019, researchers reported “We also noted a high cesarean delivery rate in the study population (39% vs. 27% in the same area in 2019), mainly as a result of maternal respiratory-indicated urgent delivery,” wrote Valeria M. Savasi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan and Luigi Sacco Hospital, also in Milan, and colleagues.

Data do not indicate that pregnant women are more susceptible to severe COVID-19 infection, nor have studies suggested an increased risk of miscarriage, congenital anomalies, or early pregnancy loss in pregnant patients with COVID-19, the authors wrote. Studies have described an increased risk of preterm birth, however.

To study clinical features of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential factors associated with severe disease and iatrogenic delivery, Dr. Savasi and colleagues conducted a prospective study of 77 women with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection who were admitted during pregnancy or the immediate postpartum period in 12 maternity hospitals in northern Italy between Feb. 23 and March 28, 2020.

The investigators classified patients as having severe disease if they underwent urgent delivery based on maternal respiratory function or if they were admitted to an ICU or subintensive care department. In all, 14 patients (18%) were classified as having severe disease.

“Three patients were intubated after emergency cesarean delivery performed for maternal deterioration, and one patient underwent extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,” Dr. Savasi and colleagues reported. The results are consistent with epidemiologic data in the nonpregnant population with COVID-19 disease.

Of 11 patients with severe disease who underwent urgent delivery for respiratory compromise, 6 had significant postpartum improvement in clinical conditions. No maternal deaths occurred.

“Increased BMI [body mass index] was a significant risk factor for severe disease,” Dr. Savasi and colleagues wrote. “Fever and dyspnea on admission were symptoms significantly associated with subsequent severe maternal respiratory deterioration.”

Most patients (65%) were admitted during the third trimester, and 20 patients were still pregnant at discharge.

“Nine newborns were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit,” the authors wrote. “Interestingly, besides prematurity, fetal oxygenation and well-being at delivery were not apparently affected by the maternal acute conditions.” Three newborns with vaginal delivery and one with cesarean delivery tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The newborns may have been infected after delivery, Dr. Savasi and colleagues added. For all newborns, rooming-in and breastfeeding were performed, and none developed respiratory symptoms.

Criteria for hospital admission and therapeutic protocols may have varied between hospitals, the authors noted. In addition, the study included 12 patients who were asymptomatic and admitted for obstetric indications. These patients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 because of contact with an infected individual. Most patients were symptomatic, however, which explains the high rate of maternal severe outcomes. Hospitals have since adopted a universal SARS-CoV-2 screening policy for hospitalized pregnant patients.

Kristina Adams Waldorf, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle, commented in an interview that Savasi et al. describe one of the larger COVID-19 in pregnancy cohorts to date with rates of severe disease and delivery for respiratory compromise, which is remarkably similar to Washington state (severe disease, 18% vs. nearly 15%; delivery for respiratory compromise, 16% vs. 20%). As in Washington state, Italian women with a higher prepregnancy BMI were overrepresented in the severe disease group.

“Data are beginning to emerge that identify women who were overweight or obese prior to pregnancy as a high risk group for developing severe COVID-19. These data are similar to known associations between obesity and critical illness in pregnancy during the 2009 ‘swine flu’ (influenza A virus, H1N1) pandemic,” she said.

“This study and others indicate that the late second and third trimesters may be a time when women are more likely to be symptomatic from COVID-19. It remains unclear if women in the first trimester are protected from severe COVID-19 outcomes or have outcomes similar to nonpregnant women,” concluded Dr. Waldorf.

One study author disclosed receiving funds from Lo Li Pharma and Zambongroup. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Waldorf said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Savasi VM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 May 19. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003979.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Testing the limits of medical technology

On March 9 my team was given a directive by the chief medical officer of our health system. It seemed like an impossible task, involving the mobilization of people, processes, and technology at a scale and speed we had never before achieved. It turned out getting this done was impossible. In spite of our best efforts, we failed to meet the deadline – it actually took us 3 days. Still, by March 12, we had opened the doors on the first community testing site in our area and gained the attention of local and national news outlets for our accomplishment.

Now more than 2 months later, I’m quite proud of what our team was able to achieve for the health system, but I’m still quite frustrated at the state of COVID-19 testing nationwide – there’s simply not enough available, and there is tremendous variability in the reliability of the tests. In this column, we’d like to highlight some of the challenges we’ve faced and reflect on how the shortcomings of modern technology have once again proven that medicine is both a science and an art.

Our dangerous lack of preparation

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, I had never considered surgical masks, face shields, and nasal swabs to be critical components of medical technology. My opinion quickly changed after opening our drive-through COVID-19 site. I now have a much greater appreciation for the importance of personal protective equipment and basic testing supplies.

I was shocked by how difficult obtaining it has been during the past few months. It seems that no one anticipated the possibility of a pandemic on this grand a scale, so stockpiles of equipment were depleted quickly and couldn’t be replenished. Also, most manufacturing occurs outside the United States, which creates additional barriers to controlling the supply chain. One need not look far to find stories of widespread price-gouging, black market racketeering, and even hijackings that have stood in the way of accessing the necessary supplies. Sadly, the lack of equipment is far from the only challenge we’ve faced. In some cases, it has been a mistrust of results that has prevented widespread testing and mitigation.

The risks of flying blind

When President Trump touted the introduction of a rapid COVID-19 test at the end of March, many people were excited. Promising positive results in as few as 5 minutes, the assay was granted an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by the Food and Drug Administration in order to expedite its availability in the market. According to the FDA’s website, an EUA allows “unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products to be used in an emergency to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions.” This rapid (though untested) approval was all that many health care providers needed to hear – immediately hospitals and physicians scrambled to get their hands on the testing devices. Unfortunately, on May 14th, the FDA issued a press release that raised concerns about that same test because it seemed to be reporting a high number of false-negative results. Just as quickly as the devices had been adopted, health care providers began backing away from them in favor of other assays, and a serious truth about COVID-19 testing was revealed: In many ways, we’re flying blind.

Laboratory manufacturers have been working overtime to create assays for SARS-CoV-2 (the coronavirus that causes COVID-19) and have used different technologies for detection. The most commonly used are polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. In these assays, viral RNA is converted to DNA by reverse transcriptase, then amplified through the addition of primers that enable detection. PCR technology has been available for years and is a reliable method for identifying DNA and RNA, but the required heating and cooling process takes time and results can take several hours to return. To address this and expedite testing, other methods of detection have been tried, such as the loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) technique employed by the rapid assay mentioned above. Regardless of methodology, all laboratory tests have one thing in common: None of them is perfect.

Every assay has a different level of reliability. When screening for a disease such as COVID-19, we are particularly interested in a test’s sensitivity (that is, it’s ability to detect disease); we’d love such a screening test to be 100% sensitive and thereby not miss a single case. In truth, no test’s sensitivity is 100%, and in this particular case even the best assays only score around 98%. This means that out of every 100 patients with COVID-19 who are evaluated, two might test negative for the virus. In a pandemic this can have dire consequences, so health care providers – unable to fully trust their instruments – must employ clinical acumen and years of experience to navigate these cloudy skies. We are hopeful that additional tools will complement our current methods, but with new assays also come new questions.

Is anyone safe?

We receive regular questions from physicians about the value of antibody testing, but it’s not yet clear how best to respond. While the assays seem to be reliable, the utility of the results are still ill defined. Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (both IgG and IgM) appear to peak about 2-3 weeks after symptom onset, but we don’t yet know if the presence of those antibodies confers long-term immunity. Therefore, patients should not use the information to change their masking or social-distancing practices, nor should they presume that they are safe from becoming reinfected with COVID-19. While new research looks promising, there are still too many unknowns to be able to confidently reassure providers or patients of the true value of antibody testing. This underscores our final point: Medicine remains an art.

As we are regularly reminded, we’ll never fully anticipate the challenges or barriers to success, and technology will never replace the value of clinical judgment and human experience. While the situation is unsettling in many ways, we are reassured and encouraged by the role we still get to play in keeping our patients healthy in this health care crisis, and we’ll continue to do so through whatever the future holds.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington Lansdale (Pa.) Hospital - Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

On March 9 my team was given a directive by the chief medical officer of our health system. It seemed like an impossible task, involving the mobilization of people, processes, and technology at a scale and speed we had never before achieved. It turned out getting this done was impossible. In spite of our best efforts, we failed to meet the deadline – it actually took us 3 days. Still, by March 12, we had opened the doors on the first community testing site in our area and gained the attention of local and national news outlets for our accomplishment.

Now more than 2 months later, I’m quite proud of what our team was able to achieve for the health system, but I’m still quite frustrated at the state of COVID-19 testing nationwide – there’s simply not enough available, and there is tremendous variability in the reliability of the tests. In this column, we’d like to highlight some of the challenges we’ve faced and reflect on how the shortcomings of modern technology have once again proven that medicine is both a science and an art.

Our dangerous lack of preparation

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, I had never considered surgical masks, face shields, and nasal swabs to be critical components of medical technology. My opinion quickly changed after opening our drive-through COVID-19 site. I now have a much greater appreciation for the importance of personal protective equipment and basic testing supplies.

I was shocked by how difficult obtaining it has been during the past few months. It seems that no one anticipated the possibility of a pandemic on this grand a scale, so stockpiles of equipment were depleted quickly and couldn’t be replenished. Also, most manufacturing occurs outside the United States, which creates additional barriers to controlling the supply chain. One need not look far to find stories of widespread price-gouging, black market racketeering, and even hijackings that have stood in the way of accessing the necessary supplies. Sadly, the lack of equipment is far from the only challenge we’ve faced. In some cases, it has been a mistrust of results that has prevented widespread testing and mitigation.

The risks of flying blind

When President Trump touted the introduction of a rapid COVID-19 test at the end of March, many people were excited. Promising positive results in as few as 5 minutes, the assay was granted an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by the Food and Drug Administration in order to expedite its availability in the market. According to the FDA’s website, an EUA allows “unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products to be used in an emergency to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions.” This rapid (though untested) approval was all that many health care providers needed to hear – immediately hospitals and physicians scrambled to get their hands on the testing devices. Unfortunately, on May 14th, the FDA issued a press release that raised concerns about that same test because it seemed to be reporting a high number of false-negative results. Just as quickly as the devices had been adopted, health care providers began backing away from them in favor of other assays, and a serious truth about COVID-19 testing was revealed: In many ways, we’re flying blind.

Laboratory manufacturers have been working overtime to create assays for SARS-CoV-2 (the coronavirus that causes COVID-19) and have used different technologies for detection. The most commonly used are polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. In these assays, viral RNA is converted to DNA by reverse transcriptase, then amplified through the addition of primers that enable detection. PCR technology has been available for years and is a reliable method for identifying DNA and RNA, but the required heating and cooling process takes time and results can take several hours to return. To address this and expedite testing, other methods of detection have been tried, such as the loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) technique employed by the rapid assay mentioned above. Regardless of methodology, all laboratory tests have one thing in common: None of them is perfect.

Every assay has a different level of reliability. When screening for a disease such as COVID-19, we are particularly interested in a test’s sensitivity (that is, it’s ability to detect disease); we’d love such a screening test to be 100% sensitive and thereby not miss a single case. In truth, no test’s sensitivity is 100%, and in this particular case even the best assays only score around 98%. This means that out of every 100 patients with COVID-19 who are evaluated, two might test negative for the virus. In a pandemic this can have dire consequences, so health care providers – unable to fully trust their instruments – must employ clinical acumen and years of experience to navigate these cloudy skies. We are hopeful that additional tools will complement our current methods, but with new assays also come new questions.

Is anyone safe?

We receive regular questions from physicians about the value of antibody testing, but it’s not yet clear how best to respond. While the assays seem to be reliable, the utility of the results are still ill defined. Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (both IgG and IgM) appear to peak about 2-3 weeks after symptom onset, but we don’t yet know if the presence of those antibodies confers long-term immunity. Therefore, patients should not use the information to change their masking or social-distancing practices, nor should they presume that they are safe from becoming reinfected with COVID-19. While new research looks promising, there are still too many unknowns to be able to confidently reassure providers or patients of the true value of antibody testing. This underscores our final point: Medicine remains an art.

As we are regularly reminded, we’ll never fully anticipate the challenges or barriers to success, and technology will never replace the value of clinical judgment and human experience. While the situation is unsettling in many ways, we are reassured and encouraged by the role we still get to play in keeping our patients healthy in this health care crisis, and we’ll continue to do so through whatever the future holds.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington Lansdale (Pa.) Hospital - Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

On March 9 my team was given a directive by the chief medical officer of our health system. It seemed like an impossible task, involving the mobilization of people, processes, and technology at a scale and speed we had never before achieved. It turned out getting this done was impossible. In spite of our best efforts, we failed to meet the deadline – it actually took us 3 days. Still, by March 12, we had opened the doors on the first community testing site in our area and gained the attention of local and national news outlets for our accomplishment.

Now more than 2 months later, I’m quite proud of what our team was able to achieve for the health system, but I’m still quite frustrated at the state of COVID-19 testing nationwide – there’s simply not enough available, and there is tremendous variability in the reliability of the tests. In this column, we’d like to highlight some of the challenges we’ve faced and reflect on how the shortcomings of modern technology have once again proven that medicine is both a science and an art.

Our dangerous lack of preparation

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, I had never considered surgical masks, face shields, and nasal swabs to be critical components of medical technology. My opinion quickly changed after opening our drive-through COVID-19 site. I now have a much greater appreciation for the importance of personal protective equipment and basic testing supplies.

I was shocked by how difficult obtaining it has been during the past few months. It seems that no one anticipated the possibility of a pandemic on this grand a scale, so stockpiles of equipment were depleted quickly and couldn’t be replenished. Also, most manufacturing occurs outside the United States, which creates additional barriers to controlling the supply chain. One need not look far to find stories of widespread price-gouging, black market racketeering, and even hijackings that have stood in the way of accessing the necessary supplies. Sadly, the lack of equipment is far from the only challenge we’ve faced. In some cases, it has been a mistrust of results that has prevented widespread testing and mitigation.

The risks of flying blind

When President Trump touted the introduction of a rapid COVID-19 test at the end of March, many people were excited. Promising positive results in as few as 5 minutes, the assay was granted an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by the Food and Drug Administration in order to expedite its availability in the market. According to the FDA’s website, an EUA allows “unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products to be used in an emergency to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions.” This rapid (though untested) approval was all that many health care providers needed to hear – immediately hospitals and physicians scrambled to get their hands on the testing devices. Unfortunately, on May 14th, the FDA issued a press release that raised concerns about that same test because it seemed to be reporting a high number of false-negative results. Just as quickly as the devices had been adopted, health care providers began backing away from them in favor of other assays, and a serious truth about COVID-19 testing was revealed: In many ways, we’re flying blind.

Laboratory manufacturers have been working overtime to create assays for SARS-CoV-2 (the coronavirus that causes COVID-19) and have used different technologies for detection. The most commonly used are polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. In these assays, viral RNA is converted to DNA by reverse transcriptase, then amplified through the addition of primers that enable detection. PCR technology has been available for years and is a reliable method for identifying DNA and RNA, but the required heating and cooling process takes time and results can take several hours to return. To address this and expedite testing, other methods of detection have been tried, such as the loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) technique employed by the rapid assay mentioned above. Regardless of methodology, all laboratory tests have one thing in common: None of them is perfect.

Every assay has a different level of reliability. When screening for a disease such as COVID-19, we are particularly interested in a test’s sensitivity (that is, it’s ability to detect disease); we’d love such a screening test to be 100% sensitive and thereby not miss a single case. In truth, no test’s sensitivity is 100%, and in this particular case even the best assays only score around 98%. This means that out of every 100 patients with COVID-19 who are evaluated, two might test negative for the virus. In a pandemic this can have dire consequences, so health care providers – unable to fully trust their instruments – must employ clinical acumen and years of experience to navigate these cloudy skies. We are hopeful that additional tools will complement our current methods, but with new assays also come new questions.

Is anyone safe?

We receive regular questions from physicians about the value of antibody testing, but it’s not yet clear how best to respond. While the assays seem to be reliable, the utility of the results are still ill defined. Antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (both IgG and IgM) appear to peak about 2-3 weeks after symptom onset, but we don’t yet know if the presence of those antibodies confers long-term immunity. Therefore, patients should not use the information to change their masking or social-distancing practices, nor should they presume that they are safe from becoming reinfected with COVID-19. While new research looks promising, there are still too many unknowns to be able to confidently reassure providers or patients of the true value of antibody testing. This underscores our final point: Medicine remains an art.

As we are regularly reminded, we’ll never fully anticipate the challenges or barriers to success, and technology will never replace the value of clinical judgment and human experience. While the situation is unsettling in many ways, we are reassured and encouraged by the role we still get to play in keeping our patients healthy in this health care crisis, and we’ll continue to do so through whatever the future holds.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and chief medical officer of Abington Lansdale (Pa.) Hospital - Jefferson Health. Follow him on Twitter (@doctornotte). Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Hospital–Jefferson Health. They have no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Scientific doubt tempers COVID-19 vaccine optimism

US government and industry projections that a COVID-19 vaccine will be ready by this fall or even January would take compressing what usually takes at least a decade into months, with little room for error or safety surprises.

“If all the cards fall into the right place and all the stars are aligned, you definitely could get a vaccine by December or January,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said last week.

But Fauci said a more realistic timeline is still 12 to 18 months, and experts interviewed by Medscape Medical News agree. They say that although recent developments are encouraging, history and scientific reason say the day when a COVID-19 vaccine is widely available will not come this year and may not come by the end of 2021.

The encouraging signals come primarily from two recent announcements: the $1.2 billion United States backing last week of one vaccine platform and the announcement on May 18 that the first human trials of another have produced some positive phase 1 results.

Recent developments

On May 21, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under “Operation Warp Speed” announced that the US will give AstraZeneca $1.2 billion “to make available at least 300 million doses of a coronavirus vaccine called AZD1222, with the first doses delivered as early as October 2020.”

On May 18, the Massachusetts-based biotechnology company Moderna announced that phase 1 clinical results showed that its vaccine candidate, which uses a new messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, appeared safe. Eight participants in the human trials were able to produce neutralizing antibodies that researchers believe are important in developing protection from the virus.

Moderna Chief Medical Officer Tal Zaks, MD, PhD told CNN that if the vaccine candidate does well in phase 2, “it could be ready by January 2021.”

The two candidates are among 10 in clinical trials for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The AstraZeneca/ AZD1222 candidate (also called ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, in collaboration with the University of Oxford) has entered phase 2/3.

Moderna’s candidate and another being developed in Beijing, China, are in phase 2, WHO reports. As of yesterday, 115 other candidates are in preclinical evaluation.

Maria Elena Bottazzi, PhD, associate dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, told Medscape Medical News it’s important to realize that, in the case of the $1.2 billion US investment, “what they’re talking about is manufacturing.”

The idea, she said, is to pay AstraZeneca up front so that manufacturing can start before it is known whether the vaccine candidate is safe or effective, the reverse of how the clinical trial process usually works.

That way, if the candidate is deemed safe and effective, time is not lost by then deciding how to make it and distribute it.

By the end of this year, she said, “Maybe we will have many vaccines made and stored in a refrigerator somewhere. But between now and December, there’s absolutely no way you can show efficacy of the vaccine at the same time you confirm that it’s safe.”

“Take these things with a grain of salt”

Animal testing for the AstraZeneca candidate, made in partnership with the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, has yielded lackluster results, according to results on the preprint server BioRxiv, which have not been peer-reviewed.

“The results were not bad, but they were not gangbusters,” Bottazzi said. The results show the vaccine offered only partial protection.

“Partial protection is better than no protection,” she noted. “You have to take these things with a grain of salt. We don’t know what’s going to happen in humans.”

As for the Moderna candidate, Bottazzi said, “the good news is they found an appropriate safety profile. But from an eight-person group to make the extrapolation that they have efficacy — it’s unrealistic.”