User login

Tool-less but not clueless

There is apparently some debate about which of our ancestors was the first to use tools. It probably was Homo habilis, the “handy man.” But it could have been a relative of Lucy, of the Australopithecus afarensis tribe. Regardless of which pile of chipped rocks looks more tool-like to you, it is generally agreed that our ability to make and use tools is one of the key ingredients to our evolutionary success.

I have always enjoyed the feel of good quality knife when I am woodcarving, and the tool collection hanging on the wall over my work bench is one of my most prized possessions. But when I was practicing general pediatrics, I could never really warm up to the screening tools that were being touted as must-haves for detecting developmental delays.

It turns out I was not alone. A recent study published in Pediatrics found that the number of pediatricians who reported using developmental screening tools increased from 21% to 63% between 2002 and 2016. (Pediatrics. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0851). However, this means that, despite a significant increase in usage, more than a third of pediatricians still are not employing screening tools. Does this suggest that one out of every three pediatricians, including me and maybe you, is a knuckle-dragging pre–Homo sapiens practicing in blissful and clueless ignorance?

Mei Elansary MD, MPhil, and Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH, who wrote a companion commentary in the same journal, suggested that maybe those of us who have resisted the call to be tool users aren’t prehistoric ignoramuses (Pediatrics. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0164). They observed that, regardless of whether the pediatricians were using screening tools, more than 40% of the those surveyed did not refer patients for early intervention.

The commentators pointed out that the decision of when, whom, and how to screen must be viewed as part of a “complicated web of changing epidemiology, time and reimbursement constraints, and service availability.” They observe that pediatricians facing this landscape in upheaval “default to what they know best: clinical judgment.” Citing one study of the management of febrile infants, the authors point out that relying on guidelines doesn’t always result in improved clinical care.

My decision of when to refer a patient for early intervention was based on what I had observed over a series of visits and whether I thought that the early intervention resources available in my community would have a significant benefit for any particular child. Because I crafted my practice around a model that put a strong emphasis on continuity, my patients almost never saw another provider for a health maintenance visit and usually saw me for their sick visits, including ear rechecks.

I guess you could argue that there are situations in which seeing a variety of providers, each with a slightly different perspective, might benefit the patient. But when we are talking about a domain like development that is defined by change, or lack of change, over time, multiple observations by a single observer usually can be more valuable.

If I were practicing in a situation in which I didn’t have the luxury of continuity, I think I would be more likely to use a screening tool. Although I have found screening guidelines can be helpful as mnemonics in some situations, they aren’t equally applicable in all clinical settings.

While I may be asking for trouble by questioning anything even remotely related to the concept of early intervention, I must say that I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Elansary and Dr. Silverstein when they wrote “the pediatrics community may have something to learn from the significant minority of pediatricians who do not practice formalized screening.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

There is apparently some debate about which of our ancestors was the first to use tools. It probably was Homo habilis, the “handy man.” But it could have been a relative of Lucy, of the Australopithecus afarensis tribe. Regardless of which pile of chipped rocks looks more tool-like to you, it is generally agreed that our ability to make and use tools is one of the key ingredients to our evolutionary success.

I have always enjoyed the feel of good quality knife when I am woodcarving, and the tool collection hanging on the wall over my work bench is one of my most prized possessions. But when I was practicing general pediatrics, I could never really warm up to the screening tools that were being touted as must-haves for detecting developmental delays.

It turns out I was not alone. A recent study published in Pediatrics found that the number of pediatricians who reported using developmental screening tools increased from 21% to 63% between 2002 and 2016. (Pediatrics. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0851). However, this means that, despite a significant increase in usage, more than a third of pediatricians still are not employing screening tools. Does this suggest that one out of every three pediatricians, including me and maybe you, is a knuckle-dragging pre–Homo sapiens practicing in blissful and clueless ignorance?

Mei Elansary MD, MPhil, and Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH, who wrote a companion commentary in the same journal, suggested that maybe those of us who have resisted the call to be tool users aren’t prehistoric ignoramuses (Pediatrics. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0164). They observed that, regardless of whether the pediatricians were using screening tools, more than 40% of the those surveyed did not refer patients for early intervention.

The commentators pointed out that the decision of when, whom, and how to screen must be viewed as part of a “complicated web of changing epidemiology, time and reimbursement constraints, and service availability.” They observe that pediatricians facing this landscape in upheaval “default to what they know best: clinical judgment.” Citing one study of the management of febrile infants, the authors point out that relying on guidelines doesn’t always result in improved clinical care.

My decision of when to refer a patient for early intervention was based on what I had observed over a series of visits and whether I thought that the early intervention resources available in my community would have a significant benefit for any particular child. Because I crafted my practice around a model that put a strong emphasis on continuity, my patients almost never saw another provider for a health maintenance visit and usually saw me for their sick visits, including ear rechecks.

I guess you could argue that there are situations in which seeing a variety of providers, each with a slightly different perspective, might benefit the patient. But when we are talking about a domain like development that is defined by change, or lack of change, over time, multiple observations by a single observer usually can be more valuable.

If I were practicing in a situation in which I didn’t have the luxury of continuity, I think I would be more likely to use a screening tool. Although I have found screening guidelines can be helpful as mnemonics in some situations, they aren’t equally applicable in all clinical settings.

While I may be asking for trouble by questioning anything even remotely related to the concept of early intervention, I must say that I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Elansary and Dr. Silverstein when they wrote “the pediatrics community may have something to learn from the significant minority of pediatricians who do not practice formalized screening.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

There is apparently some debate about which of our ancestors was the first to use tools. It probably was Homo habilis, the “handy man.” But it could have been a relative of Lucy, of the Australopithecus afarensis tribe. Regardless of which pile of chipped rocks looks more tool-like to you, it is generally agreed that our ability to make and use tools is one of the key ingredients to our evolutionary success.

I have always enjoyed the feel of good quality knife when I am woodcarving, and the tool collection hanging on the wall over my work bench is one of my most prized possessions. But when I was practicing general pediatrics, I could never really warm up to the screening tools that were being touted as must-haves for detecting developmental delays.

It turns out I was not alone. A recent study published in Pediatrics found that the number of pediatricians who reported using developmental screening tools increased from 21% to 63% between 2002 and 2016. (Pediatrics. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0851). However, this means that, despite a significant increase in usage, more than a third of pediatricians still are not employing screening tools. Does this suggest that one out of every three pediatricians, including me and maybe you, is a knuckle-dragging pre–Homo sapiens practicing in blissful and clueless ignorance?

Mei Elansary MD, MPhil, and Michael Silverstein, MD, MPH, who wrote a companion commentary in the same journal, suggested that maybe those of us who have resisted the call to be tool users aren’t prehistoric ignoramuses (Pediatrics. 2020 Apr. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0164). They observed that, regardless of whether the pediatricians were using screening tools, more than 40% of the those surveyed did not refer patients for early intervention.

The commentators pointed out that the decision of when, whom, and how to screen must be viewed as part of a “complicated web of changing epidemiology, time and reimbursement constraints, and service availability.” They observe that pediatricians facing this landscape in upheaval “default to what they know best: clinical judgment.” Citing one study of the management of febrile infants, the authors point out that relying on guidelines doesn’t always result in improved clinical care.

My decision of when to refer a patient for early intervention was based on what I had observed over a series of visits and whether I thought that the early intervention resources available in my community would have a significant benefit for any particular child. Because I crafted my practice around a model that put a strong emphasis on continuity, my patients almost never saw another provider for a health maintenance visit and usually saw me for their sick visits, including ear rechecks.

I guess you could argue that there are situations in which seeing a variety of providers, each with a slightly different perspective, might benefit the patient. But when we are talking about a domain like development that is defined by change, or lack of change, over time, multiple observations by a single observer usually can be more valuable.

If I were practicing in a situation in which I didn’t have the luxury of continuity, I think I would be more likely to use a screening tool. Although I have found screening guidelines can be helpful as mnemonics in some situations, they aren’t equally applicable in all clinical settings.

While I may be asking for trouble by questioning anything even remotely related to the concept of early intervention, I must say that I wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Elansary and Dr. Silverstein when they wrote “the pediatrics community may have something to learn from the significant minority of pediatricians who do not practice formalized screening.”

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

An unexplained exacerbation of depression, anxiety, and panic

CASE Depression, anxiety, and panic attacks

At the urging of his parents Mr. P, age 33, presents to the partial hospitalization program (PHP) for worsening depression and anxiety, daily panic attacks with accompanying diaphoresis and headache, and the possibility that he may have taken an overdose of zolpidem. Mr. P denies taking an intentional overdose of zolpidem, claiming instead that he was having a sleep-walking episode and did not realize how many pills he took.

In addition to daily panic attacks, Mr. P reports having trouble falling asleep, overwhelming sadness, and daily passive suicidal ideation without a plan or active intent.

Mr. P cannot identify a specific trigger to this most recent exacerbation of depressed/anxious mood, but instead describes it as slowly building over the past 6 to 8 months. Mr. P says the panic attacks occur without warning and states, “I feel like my heart is going to jump out of my chest; I get a terrible headache, and I sweat like crazy. Sometimes I just feel like I’m about to pass out or die.” Although these episodes had been present for approximately 2 years, they now occur almost daily.

HISTORY Inconsistent adherence

For the last year, Mr. P had been taking alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, and paroxetine, 20 mg/d, and these medications provided moderate relief of his depressive/anxious symptoms. However, he stopped taking both medications approximately 3 or 4 weeks ago when he ran out. He also takes propranolol, 20 mg/d, sporadically, for hypertension. In the past, he had been prescribed carvedilol, clonidine, and lisinopril—all with varying degrees of relief of his hypertension. He denies a family history of hypertension or any other chronic or acute health problems. He reports that he has been sober from alcohol for 19 months but smokes 1 to 2 marijuana cigarettes a day.

EVALUATION Elevated blood pressure and pulse

Mr. P’s physical examination and medical review of systems are unremarkable, except for an elevated blood pressure (190/110 mm Hg) and pulse (92 beats per minute); he also has a headache. A repeat blood pressure test later in the day is 172/94 mm Hg, with a pulse of 100 beats per minute. His urine drug screen is positive only for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

[polldaddy:10558304]

The author’s observations

A CBC with differential is helpful for ruling out infection and anemia as causes of anxiety and depression.1 In Mr. P’s case, there were no concerning symptoms that pointed to anemia or infection as likely causes of his anxiety, depression, or panic attacks. A TSH level also would be reasonable, because hyperthyroidism can present as anxiety, while hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism each can present as depression.1 However, both Mr. P’s medical history and physical examination were not concerning for thyroid disease, making it unlikely that he had either of those conditions. A review of Mr. P’s medical records indicated that within the past 6 months, his primary care physician (PCP) had ordered a CBC and TSH test; the results of both were within normal limits.

Serum porphyrin tests can exclude porphyria as a contributor to Mr. P’s anxiety and depression. Porphyrias are a group of 8 inherited disorders that involve accumulation of heme precursors (porphyrins) in the CNS and subcutaneous tissue.2 Collectively, porphyrias affect approximately 1 in 200,000 people.2 Anxiety and depression are strongly associated with porphyria, but do not occur secondary to the illness; depression and anxiety appear to be intrinsic personality features in people with porphyria.3 Skin lesions and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms,3 and there is a higher incidence of hypertension in people with porphyria than in the general population.4 Mr. P does not report any heritable disorders, nor does he appear to have any CNS disturbance or unusual cutaneous lesions, which makes it unlikely that this disorder is related to his psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: A serum metanephrines test measures...

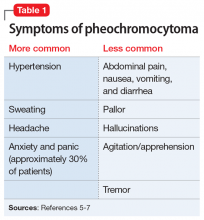

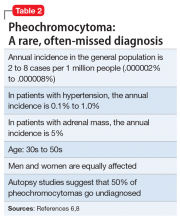

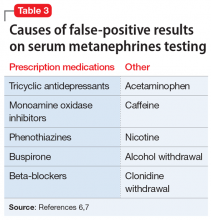

A serum metanephrines test measures the metabolites of epinephrine and norepinephrine. These catecholamines are produced in excess by an adrenal or extra-adrenal tumor seen in pheochromocytoma. The classic triad of symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic (Table 15-7). This type of tumor is rare, with an annual incidence of only 2 to 8 cases per 1 million individuals. Among people with hypertension, the annual incidence is 0.1% to 1.0%, and for those with an adrenal mass, the annual incidence is 5% (Table 26,8). Autopsy studies suggest that up to 50% of pheochromocytomas are undiagnosed.8 Left untreated, pheochromocytoma can result in hypertensive crisis, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, multisystem organ failure, and premature death.7Table 36,7 highlights some causes of false-positive serum on metanephrines testing.

EVALUATION Metanephrines testing

Mr. P has what appears to be treatment-resistant hypertension, accompanied by the classic symptoms observed in most patients with pheochromocytoma. Because Mr. P is participating in the PHP 6 days per week for 6 hours each day, visiting his PCP would be inconvenient, so the treatment team orders the serum metanephrines test. If a positive result is found, Mr. P will be referred to his PCP for further assessment and follow-up care with endocrinology.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy to target anxiety and panic

Next, the treatment team establishes a safety plan for Mr. P, and restarts paroxetine, 20 mg/d, to target his depressed and anxious mood. Alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, is started to target anxious mood and panic symptoms, and to allow time for the anxiolytic properties of the paroxetine to become fully effective. The alprazolam will be tapered and stopped after 2 weeks. Mr. P is started on hydroxyzine, 1 to 2 25-mg tablets 2 to 3 times daily as needed for anxious mood and panic symptoms.

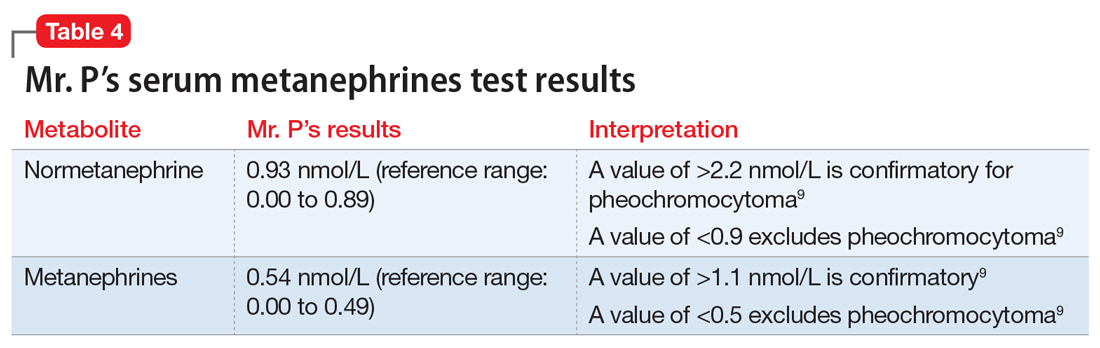

The serum metanephrines test results are equivocal, with a slight elevation of both epinephrine and norepinephrine that is too low to confirm a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma but too elevated to exclude it (Table 49). With Mr. P’s consent, the treatment team contacts his PCP and convey the results of this test. Mr. P schedules an appointment with his PCP for the following week for further assessment and confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing.

After 1 week, Mr. P remains anxious, with a slight reduction in panic attacks from multiple attacks each day to 3 or 4 attacks per week. The team considers adding an additional anxiolytic agent.

[polldaddy:10558305]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

The triad of symptoms in pheochromocytoma results directly from the intermittent release of catecholamines into systemic circulation. Surges of epinephrine and norepinephrine lead to headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis, and (less commonly) gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Persistent or episodic hypertension may be present, with 13% of patients maintaining a normal blood pressure.5-7 Patients with pheochromocytoma-related anxiety typically have substantial or complete resolution of anxiety and panic attacks after tumor resection.6,8,10

Because of their ability to raise catecholamine levels, several medications, including some psychotropics, can lead to false-positive results on serum and urine metanephrines testing. Tricyclic antidepressants and beta-blockers can cause false-positive results on plasma assays, while buspirone can cause false-positives on urinalysis assays.5 Trazodone, on the other hand, exhibits no catecholaminergic activity and its alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism may actually have some benefit in pheochromocytoma.11 Alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism with doxazosin, prazosin, or terazosin is the first-line of treatment in reducing pheochromocytoma-related hypertension.7 Treatment with a beta-blocker is safe only after alpha-adrenergic blockade occurs. While beta-blockers are useful for reducing the palpitations and anxiety observed in patients with pheochromocytoma, they must not be used alone due to the risk of hypertensive crisis resulting from unopposed alpha-adrenergic agonist activated vasoconstriction.5,7

TREATMENT CBT provides benefit

Mr. P decides against receiving an additional agent for anxiety and instead decides to wait for the outcome of the confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing. He continues to take alprazolam, and both his depressed mood and anxiety improve. His panic attacks continue to lessen, and he appears to benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy provided during group therapy. Mr. P is advised by his PCP to taper and stop the alprazolam 3 to 5 days before his 24-hour urine metanephrines test because benzodiazepines can lead to false-positive results on a urinalysis assay.7

OUTCOME Remission of anxiety and depression

Mr. P has a repeat serum metanephrines test and a 24-hour urinalysis assay. Both are negative for pheochromocytoma. His PCP refers him to cardiology for management of treatment-resistant hypertension. He is discharged from the PHP and continues psychotherapy for depression and anxiety in an intensive outpatient program (IOP). Throughout his PHP and IOP treatments, he continues to take paroxetine and hydroxyzine. He achieves a successful remission of his anxiety and depression, with partial but significant remission of his panic attacks.

The author’s observations

Although Mr. P did not have pheochromocytoma, it is important to rule out this rare condition in patients who present with treatment-resistant hypertension and/or treatment-resistant anxiety.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor of the adrenal gland. The classic triad of symptoms of this rare condition is hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic. Several medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers, and buspirone, can lead to false-positive results on the serum and urine metanephrines testing used to diagnose pheochromocytoma.

Related Resources

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Rare Disease Database: pheochromocytoma. www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pheochromocytoma/.

- Young WF Jr. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-pheochromocytoma. Published January 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Buspirone • Buspar

Carvedilol • Coreg

Clonidine • Catapres

Doxazosin • Cardura

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal

Terazosin • Hytrin

Trazodone • Desyrel

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Morrison J. When psychological problems mask medical disorders: a guide for psychotherapists. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. American Porphyria Foundation. About porphyria. https://porphyriafoundation.org/patients/about-porphyria. Accessed May 13, 2020.

3. Millward L, Kelly P, King A, et al. Anxiety and depression in the acute porphyrias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(6):1099-1107.

4. Bonkovsky H, Maddukuri VC, Yazici C, et al. Acute porphyrias in the USA: features of 108 subjects from porphyria consortium. Am J Med. 2014;127(12):1233-1241.

5. Tsirlin A, Oo Y, Sharma R, et al. Pheochromocytoma: a review. Maturitas. 2014;77(3):229-238.

6. Leung A, Zun L, Nordstrom K, et al. Psychiatric emergencies for physicians: clinical management and approach to distinguishing pheochromocytoma from psychiatric and thyrotoxic diseases in the emergency room. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(5):712-716.

7. Garg M, Kharb S, Brar KS, et al. Medical management of pheochromocytoma: role of the endocrinologist. Indian J Endocrinol and Metab. 2011;15(suppl 4):S329-S336. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.86976.

8. Zardawi I. Phaeochromocytoma masquerading as anxiety and depression. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:161-163.

9. ARUP Laboratories. Test directory. https://www.aruplab.com. Accessed February 11, 2020.

10. Sriram P, Raghavan V. Pheochromocytoma presenting as anxiety disorder: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;29:83-84.

11. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

CASE Depression, anxiety, and panic attacks

At the urging of his parents Mr. P, age 33, presents to the partial hospitalization program (PHP) for worsening depression and anxiety, daily panic attacks with accompanying diaphoresis and headache, and the possibility that he may have taken an overdose of zolpidem. Mr. P denies taking an intentional overdose of zolpidem, claiming instead that he was having a sleep-walking episode and did not realize how many pills he took.

In addition to daily panic attacks, Mr. P reports having trouble falling asleep, overwhelming sadness, and daily passive suicidal ideation without a plan or active intent.

Mr. P cannot identify a specific trigger to this most recent exacerbation of depressed/anxious mood, but instead describes it as slowly building over the past 6 to 8 months. Mr. P says the panic attacks occur without warning and states, “I feel like my heart is going to jump out of my chest; I get a terrible headache, and I sweat like crazy. Sometimes I just feel like I’m about to pass out or die.” Although these episodes had been present for approximately 2 years, they now occur almost daily.

HISTORY Inconsistent adherence

For the last year, Mr. P had been taking alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, and paroxetine, 20 mg/d, and these medications provided moderate relief of his depressive/anxious symptoms. However, he stopped taking both medications approximately 3 or 4 weeks ago when he ran out. He also takes propranolol, 20 mg/d, sporadically, for hypertension. In the past, he had been prescribed carvedilol, clonidine, and lisinopril—all with varying degrees of relief of his hypertension. He denies a family history of hypertension or any other chronic or acute health problems. He reports that he has been sober from alcohol for 19 months but smokes 1 to 2 marijuana cigarettes a day.

EVALUATION Elevated blood pressure and pulse

Mr. P’s physical examination and medical review of systems are unremarkable, except for an elevated blood pressure (190/110 mm Hg) and pulse (92 beats per minute); he also has a headache. A repeat blood pressure test later in the day is 172/94 mm Hg, with a pulse of 100 beats per minute. His urine drug screen is positive only for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

[polldaddy:10558304]

The author’s observations

A CBC with differential is helpful for ruling out infection and anemia as causes of anxiety and depression.1 In Mr. P’s case, there were no concerning symptoms that pointed to anemia or infection as likely causes of his anxiety, depression, or panic attacks. A TSH level also would be reasonable, because hyperthyroidism can present as anxiety, while hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism each can present as depression.1 However, both Mr. P’s medical history and physical examination were not concerning for thyroid disease, making it unlikely that he had either of those conditions. A review of Mr. P’s medical records indicated that within the past 6 months, his primary care physician (PCP) had ordered a CBC and TSH test; the results of both were within normal limits.

Serum porphyrin tests can exclude porphyria as a contributor to Mr. P’s anxiety and depression. Porphyrias are a group of 8 inherited disorders that involve accumulation of heme precursors (porphyrins) in the CNS and subcutaneous tissue.2 Collectively, porphyrias affect approximately 1 in 200,000 people.2 Anxiety and depression are strongly associated with porphyria, but do not occur secondary to the illness; depression and anxiety appear to be intrinsic personality features in people with porphyria.3 Skin lesions and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms,3 and there is a higher incidence of hypertension in people with porphyria than in the general population.4 Mr. P does not report any heritable disorders, nor does he appear to have any CNS disturbance or unusual cutaneous lesions, which makes it unlikely that this disorder is related to his psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: A serum metanephrines test measures...

A serum metanephrines test measures the metabolites of epinephrine and norepinephrine. These catecholamines are produced in excess by an adrenal or extra-adrenal tumor seen in pheochromocytoma. The classic triad of symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic (Table 15-7). This type of tumor is rare, with an annual incidence of only 2 to 8 cases per 1 million individuals. Among people with hypertension, the annual incidence is 0.1% to 1.0%, and for those with an adrenal mass, the annual incidence is 5% (Table 26,8). Autopsy studies suggest that up to 50% of pheochromocytomas are undiagnosed.8 Left untreated, pheochromocytoma can result in hypertensive crisis, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, multisystem organ failure, and premature death.7Table 36,7 highlights some causes of false-positive serum on metanephrines testing.

EVALUATION Metanephrines testing

Mr. P has what appears to be treatment-resistant hypertension, accompanied by the classic symptoms observed in most patients with pheochromocytoma. Because Mr. P is participating in the PHP 6 days per week for 6 hours each day, visiting his PCP would be inconvenient, so the treatment team orders the serum metanephrines test. If a positive result is found, Mr. P will be referred to his PCP for further assessment and follow-up care with endocrinology.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy to target anxiety and panic

Next, the treatment team establishes a safety plan for Mr. P, and restarts paroxetine, 20 mg/d, to target his depressed and anxious mood. Alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, is started to target anxious mood and panic symptoms, and to allow time for the anxiolytic properties of the paroxetine to become fully effective. The alprazolam will be tapered and stopped after 2 weeks. Mr. P is started on hydroxyzine, 1 to 2 25-mg tablets 2 to 3 times daily as needed for anxious mood and panic symptoms.

The serum metanephrines test results are equivocal, with a slight elevation of both epinephrine and norepinephrine that is too low to confirm a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma but too elevated to exclude it (Table 49). With Mr. P’s consent, the treatment team contacts his PCP and convey the results of this test. Mr. P schedules an appointment with his PCP for the following week for further assessment and confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing.

After 1 week, Mr. P remains anxious, with a slight reduction in panic attacks from multiple attacks each day to 3 or 4 attacks per week. The team considers adding an additional anxiolytic agent.

[polldaddy:10558305]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

The triad of symptoms in pheochromocytoma results directly from the intermittent release of catecholamines into systemic circulation. Surges of epinephrine and norepinephrine lead to headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis, and (less commonly) gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Persistent or episodic hypertension may be present, with 13% of patients maintaining a normal blood pressure.5-7 Patients with pheochromocytoma-related anxiety typically have substantial or complete resolution of anxiety and panic attacks after tumor resection.6,8,10

Because of their ability to raise catecholamine levels, several medications, including some psychotropics, can lead to false-positive results on serum and urine metanephrines testing. Tricyclic antidepressants and beta-blockers can cause false-positive results on plasma assays, while buspirone can cause false-positives on urinalysis assays.5 Trazodone, on the other hand, exhibits no catecholaminergic activity and its alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism may actually have some benefit in pheochromocytoma.11 Alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism with doxazosin, prazosin, or terazosin is the first-line of treatment in reducing pheochromocytoma-related hypertension.7 Treatment with a beta-blocker is safe only after alpha-adrenergic blockade occurs. While beta-blockers are useful for reducing the palpitations and anxiety observed in patients with pheochromocytoma, they must not be used alone due to the risk of hypertensive crisis resulting from unopposed alpha-adrenergic agonist activated vasoconstriction.5,7

TREATMENT CBT provides benefit

Mr. P decides against receiving an additional agent for anxiety and instead decides to wait for the outcome of the confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing. He continues to take alprazolam, and both his depressed mood and anxiety improve. His panic attacks continue to lessen, and he appears to benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy provided during group therapy. Mr. P is advised by his PCP to taper and stop the alprazolam 3 to 5 days before his 24-hour urine metanephrines test because benzodiazepines can lead to false-positive results on a urinalysis assay.7

OUTCOME Remission of anxiety and depression

Mr. P has a repeat serum metanephrines test and a 24-hour urinalysis assay. Both are negative for pheochromocytoma. His PCP refers him to cardiology for management of treatment-resistant hypertension. He is discharged from the PHP and continues psychotherapy for depression and anxiety in an intensive outpatient program (IOP). Throughout his PHP and IOP treatments, he continues to take paroxetine and hydroxyzine. He achieves a successful remission of his anxiety and depression, with partial but significant remission of his panic attacks.

The author’s observations

Although Mr. P did not have pheochromocytoma, it is important to rule out this rare condition in patients who present with treatment-resistant hypertension and/or treatment-resistant anxiety.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor of the adrenal gland. The classic triad of symptoms of this rare condition is hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic. Several medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers, and buspirone, can lead to false-positive results on the serum and urine metanephrines testing used to diagnose pheochromocytoma.

Related Resources

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Rare Disease Database: pheochromocytoma. www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pheochromocytoma/.

- Young WF Jr. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-pheochromocytoma. Published January 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Buspirone • Buspar

Carvedilol • Coreg

Clonidine • Catapres

Doxazosin • Cardura

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal

Terazosin • Hytrin

Trazodone • Desyrel

Zolpidem • Ambien

CASE Depression, anxiety, and panic attacks

At the urging of his parents Mr. P, age 33, presents to the partial hospitalization program (PHP) for worsening depression and anxiety, daily panic attacks with accompanying diaphoresis and headache, and the possibility that he may have taken an overdose of zolpidem. Mr. P denies taking an intentional overdose of zolpidem, claiming instead that he was having a sleep-walking episode and did not realize how many pills he took.

In addition to daily panic attacks, Mr. P reports having trouble falling asleep, overwhelming sadness, and daily passive suicidal ideation without a plan or active intent.

Mr. P cannot identify a specific trigger to this most recent exacerbation of depressed/anxious mood, but instead describes it as slowly building over the past 6 to 8 months. Mr. P says the panic attacks occur without warning and states, “I feel like my heart is going to jump out of my chest; I get a terrible headache, and I sweat like crazy. Sometimes I just feel like I’m about to pass out or die.” Although these episodes had been present for approximately 2 years, they now occur almost daily.

HISTORY Inconsistent adherence

For the last year, Mr. P had been taking alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, and paroxetine, 20 mg/d, and these medications provided moderate relief of his depressive/anxious symptoms. However, he stopped taking both medications approximately 3 or 4 weeks ago when he ran out. He also takes propranolol, 20 mg/d, sporadically, for hypertension. In the past, he had been prescribed carvedilol, clonidine, and lisinopril—all with varying degrees of relief of his hypertension. He denies a family history of hypertension or any other chronic or acute health problems. He reports that he has been sober from alcohol for 19 months but smokes 1 to 2 marijuana cigarettes a day.

EVALUATION Elevated blood pressure and pulse

Mr. P’s physical examination and medical review of systems are unremarkable, except for an elevated blood pressure (190/110 mm Hg) and pulse (92 beats per minute); he also has a headache. A repeat blood pressure test later in the day is 172/94 mm Hg, with a pulse of 100 beats per minute. His urine drug screen is positive only for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

[polldaddy:10558304]

The author’s observations

A CBC with differential is helpful for ruling out infection and anemia as causes of anxiety and depression.1 In Mr. P’s case, there were no concerning symptoms that pointed to anemia or infection as likely causes of his anxiety, depression, or panic attacks. A TSH level also would be reasonable, because hyperthyroidism can present as anxiety, while hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism each can present as depression.1 However, both Mr. P’s medical history and physical examination were not concerning for thyroid disease, making it unlikely that he had either of those conditions. A review of Mr. P’s medical records indicated that within the past 6 months, his primary care physician (PCP) had ordered a CBC and TSH test; the results of both were within normal limits.

Serum porphyrin tests can exclude porphyria as a contributor to Mr. P’s anxiety and depression. Porphyrias are a group of 8 inherited disorders that involve accumulation of heme precursors (porphyrins) in the CNS and subcutaneous tissue.2 Collectively, porphyrias affect approximately 1 in 200,000 people.2 Anxiety and depression are strongly associated with porphyria, but do not occur secondary to the illness; depression and anxiety appear to be intrinsic personality features in people with porphyria.3 Skin lesions and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms,3 and there is a higher incidence of hypertension in people with porphyria than in the general population.4 Mr. P does not report any heritable disorders, nor does he appear to have any CNS disturbance or unusual cutaneous lesions, which makes it unlikely that this disorder is related to his psychiatric symptoms.

Continue to: A serum metanephrines test measures...

A serum metanephrines test measures the metabolites of epinephrine and norepinephrine. These catecholamines are produced in excess by an adrenal or extra-adrenal tumor seen in pheochromocytoma. The classic triad of symptoms of pheochromocytoma are hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic (Table 15-7). This type of tumor is rare, with an annual incidence of only 2 to 8 cases per 1 million individuals. Among people with hypertension, the annual incidence is 0.1% to 1.0%, and for those with an adrenal mass, the annual incidence is 5% (Table 26,8). Autopsy studies suggest that up to 50% of pheochromocytomas are undiagnosed.8 Left untreated, pheochromocytoma can result in hypertensive crisis, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, multisystem organ failure, and premature death.7Table 36,7 highlights some causes of false-positive serum on metanephrines testing.

EVALUATION Metanephrines testing

Mr. P has what appears to be treatment-resistant hypertension, accompanied by the classic symptoms observed in most patients with pheochromocytoma. Because Mr. P is participating in the PHP 6 days per week for 6 hours each day, visiting his PCP would be inconvenient, so the treatment team orders the serum metanephrines test. If a positive result is found, Mr. P will be referred to his PCP for further assessment and follow-up care with endocrinology.

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy to target anxiety and panic

Next, the treatment team establishes a safety plan for Mr. P, and restarts paroxetine, 20 mg/d, to target his depressed and anxious mood. Alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily, is started to target anxious mood and panic symptoms, and to allow time for the anxiolytic properties of the paroxetine to become fully effective. The alprazolam will be tapered and stopped after 2 weeks. Mr. P is started on hydroxyzine, 1 to 2 25-mg tablets 2 to 3 times daily as needed for anxious mood and panic symptoms.

The serum metanephrines test results are equivocal, with a slight elevation of both epinephrine and norepinephrine that is too low to confirm a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma but too elevated to exclude it (Table 49). With Mr. P’s consent, the treatment team contacts his PCP and convey the results of this test. Mr. P schedules an appointment with his PCP for the following week for further assessment and confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing.

After 1 week, Mr. P remains anxious, with a slight reduction in panic attacks from multiple attacks each day to 3 or 4 attacks per week. The team considers adding an additional anxiolytic agent.

[polldaddy:10558305]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

The triad of symptoms in pheochromocytoma results directly from the intermittent release of catecholamines into systemic circulation. Surges of epinephrine and norepinephrine lead to headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis, and (less commonly) gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Persistent or episodic hypertension may be present, with 13% of patients maintaining a normal blood pressure.5-7 Patients with pheochromocytoma-related anxiety typically have substantial or complete resolution of anxiety and panic attacks after tumor resection.6,8,10

Because of their ability to raise catecholamine levels, several medications, including some psychotropics, can lead to false-positive results on serum and urine metanephrines testing. Tricyclic antidepressants and beta-blockers can cause false-positive results on plasma assays, while buspirone can cause false-positives on urinalysis assays.5 Trazodone, on the other hand, exhibits no catecholaminergic activity and its alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism may actually have some benefit in pheochromocytoma.11 Alpha-1 adrenergic antagonism with doxazosin, prazosin, or terazosin is the first-line of treatment in reducing pheochromocytoma-related hypertension.7 Treatment with a beta-blocker is safe only after alpha-adrenergic blockade occurs. While beta-blockers are useful for reducing the palpitations and anxiety observed in patients with pheochromocytoma, they must not be used alone due to the risk of hypertensive crisis resulting from unopposed alpha-adrenergic agonist activated vasoconstriction.5,7

TREATMENT CBT provides benefit

Mr. P decides against receiving an additional agent for anxiety and instead decides to wait for the outcome of the confirmatory pheochromocytoma testing. He continues to take alprazolam, and both his depressed mood and anxiety improve. His panic attacks continue to lessen, and he appears to benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy provided during group therapy. Mr. P is advised by his PCP to taper and stop the alprazolam 3 to 5 days before his 24-hour urine metanephrines test because benzodiazepines can lead to false-positive results on a urinalysis assay.7

OUTCOME Remission of anxiety and depression

Mr. P has a repeat serum metanephrines test and a 24-hour urinalysis assay. Both are negative for pheochromocytoma. His PCP refers him to cardiology for management of treatment-resistant hypertension. He is discharged from the PHP and continues psychotherapy for depression and anxiety in an intensive outpatient program (IOP). Throughout his PHP and IOP treatments, he continues to take paroxetine and hydroxyzine. He achieves a successful remission of his anxiety and depression, with partial but significant remission of his panic attacks.

The author’s observations

Although Mr. P did not have pheochromocytoma, it is important to rule out this rare condition in patients who present with treatment-resistant hypertension and/or treatment-resistant anxiety.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor of the adrenal gland. The classic triad of symptoms of this rare condition is hypertension, sweating, and headache; approximately 30% of patients report significant anxiety and panic. Several medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, beta-blockers, and buspirone, can lead to false-positive results on the serum and urine metanephrines testing used to diagnose pheochromocytoma.

Related Resources

- National Organization for Rare Disorders. Rare Disease Database: pheochromocytoma. www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/pheochromocytoma/.

- Young WF Jr. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-and-diagnosis-of-pheochromocytoma. Published January 2020.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Buspirone • Buspar

Carvedilol • Coreg

Clonidine • Catapres

Doxazosin • Cardura

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Paroxetine • Paxil

Prazosin • Minipress

Propranolol • Inderal

Terazosin • Hytrin

Trazodone • Desyrel

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Morrison J. When psychological problems mask medical disorders: a guide for psychotherapists. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. American Porphyria Foundation. About porphyria. https://porphyriafoundation.org/patients/about-porphyria. Accessed May 13, 2020.

3. Millward L, Kelly P, King A, et al. Anxiety and depression in the acute porphyrias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(6):1099-1107.

4. Bonkovsky H, Maddukuri VC, Yazici C, et al. Acute porphyrias in the USA: features of 108 subjects from porphyria consortium. Am J Med. 2014;127(12):1233-1241.

5. Tsirlin A, Oo Y, Sharma R, et al. Pheochromocytoma: a review. Maturitas. 2014;77(3):229-238.

6. Leung A, Zun L, Nordstrom K, et al. Psychiatric emergencies for physicians: clinical management and approach to distinguishing pheochromocytoma from psychiatric and thyrotoxic diseases in the emergency room. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(5):712-716.

7. Garg M, Kharb S, Brar KS, et al. Medical management of pheochromocytoma: role of the endocrinologist. Indian J Endocrinol and Metab. 2011;15(suppl 4):S329-S336. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.86976.

8. Zardawi I. Phaeochromocytoma masquerading as anxiety and depression. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:161-163.

9. ARUP Laboratories. Test directory. https://www.aruplab.com. Accessed February 11, 2020.

10. Sriram P, Raghavan V. Pheochromocytoma presenting as anxiety disorder: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;29:83-84.

11. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

1. Morrison J. When psychological problems mask medical disorders: a guide for psychotherapists. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015.

2. American Porphyria Foundation. About porphyria. https://porphyriafoundation.org/patients/about-porphyria. Accessed May 13, 2020.

3. Millward L, Kelly P, King A, et al. Anxiety and depression in the acute porphyrias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2005;28(6):1099-1107.

4. Bonkovsky H, Maddukuri VC, Yazici C, et al. Acute porphyrias in the USA: features of 108 subjects from porphyria consortium. Am J Med. 2014;127(12):1233-1241.

5. Tsirlin A, Oo Y, Sharma R, et al. Pheochromocytoma: a review. Maturitas. 2014;77(3):229-238.

6. Leung A, Zun L, Nordstrom K, et al. Psychiatric emergencies for physicians: clinical management and approach to distinguishing pheochromocytoma from psychiatric and thyrotoxic diseases in the emergency room. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(5):712-716.

7. Garg M, Kharb S, Brar KS, et al. Medical management of pheochromocytoma: role of the endocrinologist. Indian J Endocrinol and Metab. 2011;15(suppl 4):S329-S336. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.86976.

8. Zardawi I. Phaeochromocytoma masquerading as anxiety and depression. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:161-163.

9. ARUP Laboratories. Test directory. https://www.aruplab.com. Accessed February 11, 2020.

10. Sriram P, Raghavan V. Pheochromocytoma presenting as anxiety disorder: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;29:83-84.

11. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Cannabidiol for psychosis: A review of 4 studies

There has been increasing interest in the medicinal use of cannabidiol (CBD) for a wide variety of health conditions. CBD is one of more than 80 chemicals identified in the Cannabis sativa plant, otherwise known as marijuana or hemp. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the psychoactive ingredient found in marijuana that produces a “high.” CBD, which is one of the most abundant cannabinoids in Cannabis sativa, does not produce any psychotomimetic effects.

The strongest scientific evidence supporting CBD for medicinal purposes is for its effectiveness in treating certain childhood epilepsy syndromes that typically do not respond to antiseizure medications. Currently, the only FDA-approved CBD product is a prescription oil cannabidiol (brand name: Epidiolex) for treating 2 types of epilepsy. Aside from Epidiolex, state laws governing the use of CBD vary. CBD is being studied as a treatment for a wide range of psychiatric conditions, including bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, dystonia, insomnia, and anxiety. Research supporting CBD’s benefits is limited, and the US National Library of Medicine’s MedlinePlus indicates there is “insufficient evidence to rate effectiveness” for these indications.1

Despite having been legalized for medicinal use in many states, CBD is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance by the US Drug Enforcement Agency. Because of this classification, little has been done to regulate and oversee the sale of products containing CBD. In a 2017 study of 84 CBD products sold by 31 companies online, Bonn-Miller et al2 found that nearly 70% percent of products were inaccurately labeled. In this study, blind testing found that only approximately 31% of products contained within 10% of the amount of CBD that was listed on the label. These researchers also found that some products contained components not listed on the label, including THC.2

The relationship between cannabis and psychosis or psychotic symptoms has been investigated for decades. Some recent studies that examined the effects of CBD on psychosis found that individuals who use CBD may experience fewer positive psychotic symptoms compared with placebo. This raises the question of whether CBD may have a role in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. One of the first studies on this issue was conducted by Leweke et al,3 who compared oral CBD, up to 800 mg/d, with the antipsychotic amisulpride, up to 800 mg/d, in 39 patients with an acute exacerbation of psychotic symptoms. Amisulpride is used outside the United States to treat psychosis, but is FDA-approved only as an antiemetic. Patients were treated for 4 weeks. By Day 28, there was a significant reduction in positive symptoms as measured using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), with no significant difference in efficacy between the treatments. Similar findings emerged for negative, total, and general symptoms, with significant reductions by Day 28 in both treatment arms, and no significant between-treatment differences.

These findings were the first robust indication that CBD may have antipsychotic efficacy. However, of greater interest may be CBD’s markedly superior adverse effect profile. Predictably, amisulpride significantly increased extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight gain, and prolactin levels from baseline to Day 28. However, no significant change was found in any of these adverse effects in the CBD group, and the between-treatment difference was significant (all P < .01).

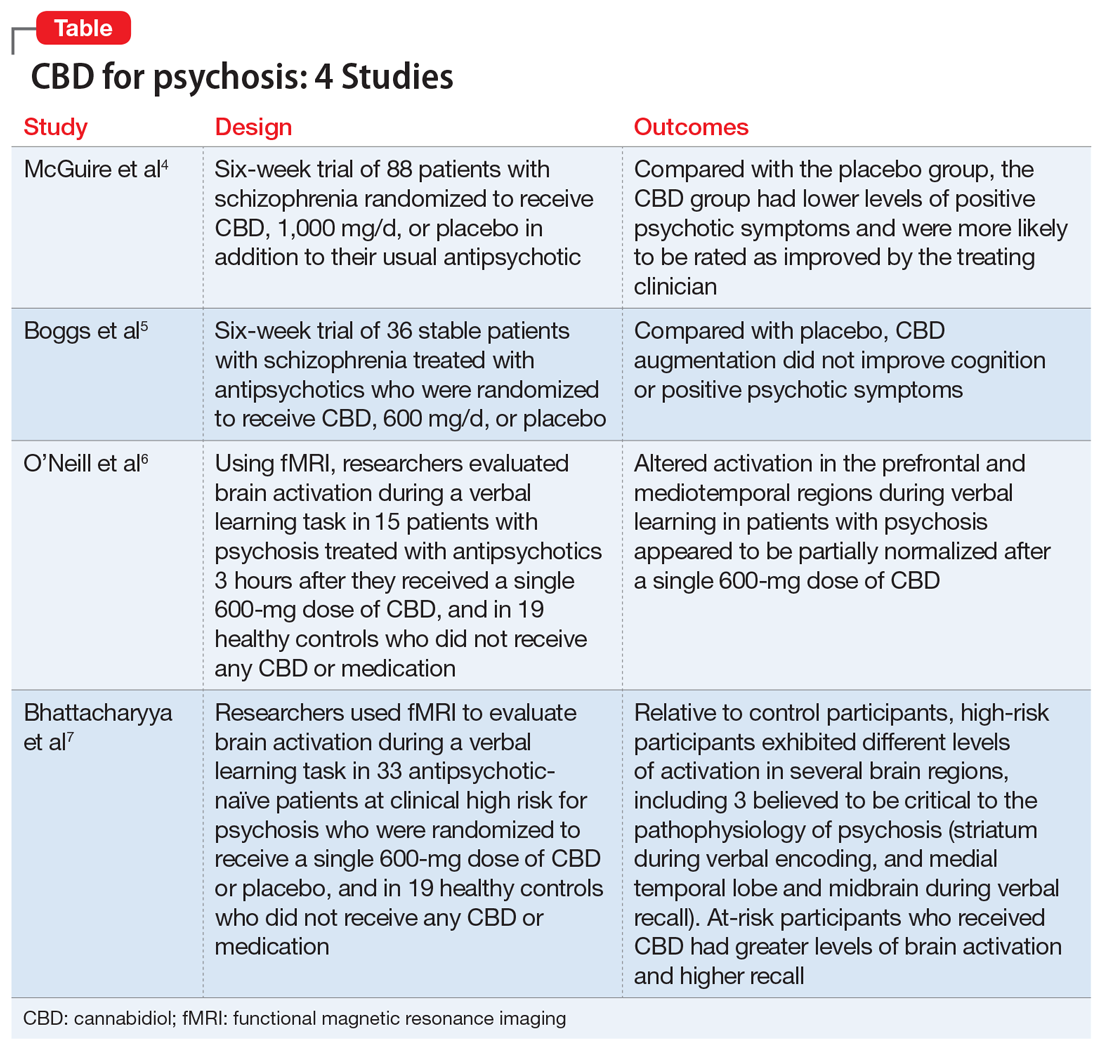

Here we review 4 recent studies that evaluated CBD as a treatment for schizophrenia. These studies are summarized in the Table.4-7

Continue to: McGuire P, et al...

1. McGuire P, Robson P, Cubala WJ, et al. Cannabidiol (CBD) as an adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(3):225-231.

Antipsychotic medications act through blockade of central dopamine D2 receptors. For most patients, antipsychotics effectively treat positive psychotic symptoms, which are driven by elevated dopamine function. However, these medications have minimal effects on negative symptoms and cognitive impairment, features of schizophrenia that are not driven by elevated dopamine. Compounds exhibiting a mechanism of action unlike that of current antipsychotics may improve the treatment and outcomes of patients with schizophrenia. The mechanism of action of CBD is unclear, but it does not appear to involve the direct antagonism of dopamine receptors. Human and animal research study findings indicate that CBD has antipsychotic properties. McGuire et al4 assessed the safety and effectiveness of CBD as an adjunctive treatment of schizophrenia.

Study design

- In this double-blind parallel-group trial conducted at 15 hospitals in the United Kingdom, Romania, and Poland, 88 patients with schizophrenia received CBD (1,000 mg/d; N = 43) or placebo (N = 45) as adjunct to the antipsychotic medication they had been prescribed. Patients had previously demonstrated at least a partial response to antipsychotic treatment, and were taking stable doses of an antipsychotic for ≥4 weeks.

- Evaluations of symptoms, general functioning, cognitive performance, and EPS were completed at baseline and on Days 8, 22, and 43 (± 3 days). Current substance use was assessed using a semi-structured interview, and reassessed at the end of treatment.

- The key endpoints were the patients’ level of functioning, severity of symptoms, and cognitive performance. Participants were assessed before and after treatment using the PANSS, the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS), the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF), and the improvement and severity scales of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI-I and CGI-S, respectively).

- The clinicians’ impression of illness severity and symptom improvement and patient- or caregiver-reported impressions of general functioning and sleep also were noted.

Outcomes

- After 6 weeks, compared with the placebo group, the CBD group had lower levels of positive psychotic symptoms and were more likely to be rated as improved and as not severely unwell by the treating clinician. Patients in the CBD group also showed greater improvements in cognitive performance and in overall functioning, although these were not statistically significant.

- Similar levels of negative psychotic symptoms, overall psychopathology, and general psychopathology were observed in the CBD and placebo groups. The CBD group had a higher proportion of treatment responders (≥20% improvement in PANSS total score) than did the placebo group; however, the total number of responders per group was small (12 and 6 patients, respectively). At baseline, most patients in both groups were classified as moderately, markedly, or severely ill (83.4% in the CBD group vs 79.6% in placebo group). By the end of treatment, this decreased to 54.8% in the CBD group and 63.6% in the placebo group. Clinicians rated 78.6% of patients in the CBD group as “improved” on the CGI-I, compared with 54.6% of patients in the placebo group.

Conclusion

- CBD treatment adjunctive to antipsychotics was associated with significant effects on positive psychotic symptoms and on CGI-I and illness severity. Improvements in cognitive performance and level of overall functioning were also seen, but were not statistically significant.

- Although the effect on positive symptoms was modest, improvement occurred in patients being treated with appropriate dosages of antipsychotics, which suggests CBD provided benefits over and above the effect of antipsychotic treatment. Moreover, the changes in CGI-I and CGI-S scores indicated that the improvement was evident to the treating psychiatrists, and may therefore be clinically meaningful.

Continue to: Boggs DL, et al...

2. Boggs DL, Surti T, Gupta A, et al. The effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on cognition and symptoms in outpatients with chronic schizophrenia a randomized placebo controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(7):1923-1932.

Schizophrenia is associated with cognitive deficits in learning, recall, attention, working memory, and executive function. The cognitive impairments associated with schizophrenia (CIAS) are independent of phase of illness and often persist after other symptoms have been effectively treated. These impairments are the strongest predictor of functional outcome, even more so than psychotic symptoms.

Antipsychotics have limited efficacy for CIAS, which highlights the need for CIAS treatments that target other nondopaminergic neurotransmitter systems. The endocannabinoid system, which has been implicated in schizophrenia and in cognition, is a potential target. Several cannabinoids impair memory and attention. The main psychoactive component of marijuana, THC, is a cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R) partial agonist. Administration of THC produces significant deficits in verbal learning, attention, and working memory.

Researchers have hypothesized that CB1R blockade or modulation of cannabinoid levels may offer a novel target for treating CIAS. Boggs et al5 compared the cognitive, symptomatic, and adverse effects of CBD vs placebo.

Study design

- In this 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted in Connecticut from September 2009 to May 2012, 36 stable patients with schizophrenia who were treated with antipsychotics were randomized to also receive oral CBD, 600 mg/d, or placebo.

- Cognition was assessed using the t score of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) composite and subscales at baseline and the end of study. An increase in MCCB t score indicates an improvement in cognitive ability. Psychotic symptoms were assessed using the PANSS at baseline, Week 2, Week 4, and Week 6.

Outcomes

- CBD augmentation did not improve MCCB performance or psychotic symptoms. There was no main effect of time or medication on MCCB composite score, but a significant drug × time effect was observed.

- Post-hoc analyses revealed that only patients who received placebo improved over time. The lack of a similar improvement with CBD might be related to the greater incidence of sedation among the CBD group (20%) vs the placebo group (5%). Both the MCCB composite score and reasoning and problem-solving domain scores were higher at baseline and endpoint for patients who received CBD, which suggests that the observed improvement in the placebo group could represent a regression to the mean.

- There was a significant decrease in PANSS scores over time, but there was no significant drug × time interaction.

Conclusion

- CBD augmentation was not associated with an improvement in MCCB score. This is consistent with data from other clinical trials4,8 that suggested that CBD (at a wide range of doses) does not have significant beneficial effects on cognition in patients with schizophrenia.

- Additionally, CBD did not improve psychotic symptoms. These results are in contrast to published case reports9,10 and 2 published clinical trials3,4 that found CBD (800 mg/d) was as efficacious as amisulpride in reducing positive psychotic symptoms, and a small but statistically significant improvement in PANSS positive scores with CBD (1,000 mg/d) compared with placebo. However, these results are similar to those of a separate study11 that evaluated the same 600-mg/d dose of CBD used by Boggs et al.5 At 600 mg/d, CBD produced very small improvements in PANSS total scores (~2.4) that were not statistically significant. A higher CBD dose may be needed to reduce psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Continue to: O’Neill A, et al...

3. O’Neill A, Wilson R, Blest-Hopley G, et al. Normalization of mediotemporal and prefrontal activity, and mediotemporal-striatal connectivity, may underlie antipsychotic effects of cannabidiol in psychosis. Psychol Med. 2020;1-11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003519.

In addition to their key roles in the psychopathology of psychosis, the mediotemporal and prefrontal cortices are involved in learning and memory, and the striatum plays a role in encoding contextual information associated with memories. Because deficits in verbal learning and memory are one of the most commonly reported impairments in patients with psychosis, O’Neill et al6 used functional MRI (fMRI) to examine brain activity during a verbal learning task in patients with psychosis after taking CBD or placebo.

Study design

- In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study, researchers investigated the effects of a single dose of CBD in 15 patients with psychosis who were treated with antipsychotics. Three hours after taking a 600-mg dose of CBD or placebo, these participants were scanned using fMRI while performing a verbal paired associate (VPA) learning task. Nineteen healthy controls underwent fMRI in identical conditions, but without any medication administration.

- The fMRI measured brain activation using the blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) hemodynamic responses of the brain. The fMRI signals were studied in the mediotemporal, prefrontal, and striatal regions.

- The VPA task presented word pairs visually, and the accuracy of responses were recorded online. The VPA task was comprised of 3 conditions: encoding, recall, and baseline.

- Results during each phase of the VPA task were compared.

Outcomes

- While completing the VPA task after taking placebo, compared with healthy controls, patients with psychosis demonstrated a different pattern of activity in the prefrontal and mediotemporal brain areas. Specifically, during verbal encoding, the placebo group showed altered activation in prefrontal regions. During verbal recall, the placebo group showed altered activation in prefrontal and mediotemporal regions, as well as increased mediotemporal-striatal functional connectivity.

- After participants received CBD, activation in these brain areas became more like the activation seen in controls. CBD attenuated dysfunction in these regions such that activation was intermediate between the placebo condition and the control group. CBD also attenuated functional connectivity between the hippocampus and striatum, and lead to reduced symptoms in patients with psychosis (as measured by PANSS total score).

Conclusion

- Altered activation in prefrontal and mediotemporal regions during verbal learning in patients with psychosis appeared to be partially normalized after a single 600-mg dose of CBD. Results also showed improvement in PANSS total score with CBD.

- These findings suggest that a single dose of CBD may partially attenuate the dysfunctional prefrontal and mediotemporal activation that is believed to underlie the dopamine dysfunction that leads to psychotic symptoms. These effects, along with a reduction in psychotic symptoms, suggest that normalization of altered prefrontal and mediotemporal function and mediotemporal-striatal connectivity may underlie the antipsychotic effects of CBD in established psychosis.

Continue to: Bhattacharyya S, et al...

4. Bhattacharyya S, Wilson R, Appiah-Kusi E, et al. Effect of cannabidiol on medial temporal, midbrain, and striatal dysfunction in people at clinical high risk of psychosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(11):1107-1117.

Current preclinical models suggest that psychosis involves a disturbance of activity in the medial temporal lobe (MTL) that drives dopamine dysfunction in the striatum and midbrain. THC, which produces psychotomimetic effects, impacts the function of the striatum (verbal memoryand salience processing) andamygdala (emotional processing), and alters the functional connectivity of these regions. Compared with THC, CBD has broadly opposite neural and behavioral effects, including opposing effects on the activation of these regions. Bhattacharyya et al7 examined the neurocognitive mechanisms that underlie the therapeutic effects of CBD in psychosis and sought to understand whether CBD would attenuate functional abnormalities in the MTL, midbrain, and striatum.

Study design

- A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial examined 33 antipsychotic-naïve participants at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis and 19 healthy controls. The CHR group was randomized to CBD, 600 mg, or placebo.

- Three hours after taking CBD or placebo, CHR participants were studied using fMRI while performing a VPA learning task, which engages verbal learning and recall in the MTL, midbrain and striatum. Control participants did not receive any medication but underwent fMRI while performing the VPA task.

- The VPA task presented word pairs visually, and the accuracy of responses was recorded online. It was comprised of 3 conditions: encoding, recall, and baseline.

Outcomes

- Brain activation was analyzed in 15 participants in the CBD group, 16 in the placebo group, and 19 in the control group. Activation during encoding was observed in the striatum (specifically, the right caudate). Activation during recall was observed in the midbrain and the MTL (specifically, the parahippocampus).

- Brain activation levels in all 3 regions were lowest in the placebo group, intermediate in the CBD group, and greatest in the healthy control group. For all participants, the total recall score was directly correlated with the activation level in the left MTL (parahippocampus) during recall.

Conclusion

- Relative to controls, CHR participants exhibited different levels of activation in several regions, including the 3 areas thought to be critical to the pathophysiology of psychosis: the striatum during verbal encoding, and the MTL and midbrain during verbal recall.

- Compared with those who received placebo, CHR participants who received CBD before completing the VPA task demonstrated greater levels of brain activation and higher recall score.

- These findings suggest that CBD may partially normalize alterations in MTL, striatal, and midbrain function associated with CHR of psychosis. Because these regions are implicated in the pathophysiology of psychosis, the impact of CBD at these sites may contribute to the therapeutic effects of CBD that have been reported by some patients with psychosis.

Continue to: Conflicting data highlights...

Conflicting data highlights the need for longer, larger studies

Research findings on the use of CBD for psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia have been conflicting. Some early research suggests that taking CBD 4 times daily for 4 weeks improves psychotic symptoms and might be as effective as the antipsychotic amisulpride. However, other early research suggests that taking CBD for 14 days is not beneficial. The conflicting results might be related to the CBD dose used and duration of treatment.

Davies and Bhattacharya12 recently reviewed evidence regarding the efficacy of CBD as a potential novel treatment for psychotic disorders.They concluded that CBD represents a promising potential novel treatment for patients with psychosis. It also appears that CBD may improve the disease trajectory of individuals with early psychosis and comorbid cannabis misuse.13 CBD use has also been associated with a decrease in symptoms of psychosis and changes in brain activity during verbal memory tasks in patients at high risk of psychosis.6 However, before CBD can become a viable treatment option for psychosis, the promising findings in these initial clinical studies must be replicated in large-scale trials with appropriate treatment duration.

1. US National Library of Medicine. MedlinePlus. Cannabidiol (CBD). https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/natural/1439.html. Accessed May 14, 2020.

2. Bonn-Miller MO, Loflin MJE, Thomas BF, et al. Labeling accuracy of cannabidiol extracts sold online. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1708-1709.

3. Leweke FM, Piomelli D, Pahlisch F, et al. Cannabidiol enhances anandamide signaling and alleviates psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2(3):e94.

4. McGuire P, Robson P, Cubala WJ, et al. Cannabidiol (CBD) as an adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(3):225-231.

5. Boggs DL, Surti T, Gupta A, et al. The effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on cognition and symptoms in outpatients with chronic schizophrenia a randomized placebo controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(7):1923-1932.

6. O’Neill A, Wilson R, Blest-Hopley G, et al. Normalization of mediotemporal and prefrontal activity, and mediotemporal-striatal connectivity, may underlie antipsychotic effects of cannabidiol in psychosis. Psychol Med. 2020;1-11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003519.

7. Bhattacharyya S, Wilson R, Appiah-Kusi E, et al. Effect of cannabidiol on medial temporal, midbrain, and striatal dysfunction in people at clinical high risk of psychosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(11):1107-1117.

8. Hallak JE, Machado-de-Sousa JP, Crippa JAS, et al. Performance of schizophrenic patients in the Stroop color word test and electrodermal responsiveness after acute administration of cannabidiol (CBD). Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32(1):56-61.

9. Zuardi AW, Morais SL, Guimaraes FS, et al. Antipsychotic effect of cannabidiol. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(10):485-486.

10. Zuardi AW, Hallak JE, Dursun SM, et al. Cannabidiol monotherapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(5):683-686.

11. Leweke FM, Hellmich M, Pahlisch F, et al. Modulation of the endocannabinoid system as a potential new target in the treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014; 153(1):S47.

12. Davies C, Bhattacharyya S. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for psychosis. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2019;9. doi:10.1177/2045125319881916.

13. Hahn B. The potential of cannabidiol treatment for cannabis users with recent-onset psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(1):46-53.

There has been increasing interest in the medicinal use of cannabidiol (CBD) for a wide variety of health conditions. CBD is one of more than 80 chemicals identified in the Cannabis sativa plant, otherwise known as marijuana or hemp. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the psychoactive ingredient found in marijuana that produces a “high.” CBD, which is one of the most abundant cannabinoids in Cannabis sativa, does not produce any psychotomimetic effects.

The strongest scientific evidence supporting CBD for medicinal purposes is for its effectiveness in treating certain childhood epilepsy syndromes that typically do not respond to antiseizure medications. Currently, the only FDA-approved CBD product is a prescription oil cannabidiol (brand name: Epidiolex) for treating 2 types of epilepsy. Aside from Epidiolex, state laws governing the use of CBD vary. CBD is being studied as a treatment for a wide range of psychiatric conditions, including bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, dystonia, insomnia, and anxiety. Research supporting CBD’s benefits is limited, and the US National Library of Medicine’s MedlinePlus indicates there is “insufficient evidence to rate effectiveness” for these indications.1

Despite having been legalized for medicinal use in many states, CBD is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance by the US Drug Enforcement Agency. Because of this classification, little has been done to regulate and oversee the sale of products containing CBD. In a 2017 study of 84 CBD products sold by 31 companies online, Bonn-Miller et al2 found that nearly 70% percent of products were inaccurately labeled. In this study, blind testing found that only approximately 31% of products contained within 10% of the amount of CBD that was listed on the label. These researchers also found that some products contained components not listed on the label, including THC.2

The relationship between cannabis and psychosis or psychotic symptoms has been investigated for decades. Some recent studies that examined the effects of CBD on psychosis found that individuals who use CBD may experience fewer positive psychotic symptoms compared with placebo. This raises the question of whether CBD may have a role in the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. One of the first studies on this issue was conducted by Leweke et al,3 who compared oral CBD, up to 800 mg/d, with the antipsychotic amisulpride, up to 800 mg/d, in 39 patients with an acute exacerbation of psychotic symptoms. Amisulpride is used outside the United States to treat psychosis, but is FDA-approved only as an antiemetic. Patients were treated for 4 weeks. By Day 28, there was a significant reduction in positive symptoms as measured using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), with no significant difference in efficacy between the treatments. Similar findings emerged for negative, total, and general symptoms, with significant reductions by Day 28 in both treatment arms, and no significant between-treatment differences.

These findings were the first robust indication that CBD may have antipsychotic efficacy. However, of greater interest may be CBD’s markedly superior adverse effect profile. Predictably, amisulpride significantly increased extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight gain, and prolactin levels from baseline to Day 28. However, no significant change was found in any of these adverse effects in the CBD group, and the between-treatment difference was significant (all P < .01).

Here we review 4 recent studies that evaluated CBD as a treatment for schizophrenia. These studies are summarized in the Table.4-7

Continue to: McGuire P, et al...

1. McGuire P, Robson P, Cubala WJ, et al. Cannabidiol (CBD) as an adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(3):225-231.

Antipsychotic medications act through blockade of central dopamine D2 receptors. For most patients, antipsychotics effectively treat positive psychotic symptoms, which are driven by elevated dopamine function. However, these medications have minimal effects on negative symptoms and cognitive impairment, features of schizophrenia that are not driven by elevated dopamine. Compounds exhibiting a mechanism of action unlike that of current antipsychotics may improve the treatment and outcomes of patients with schizophrenia. The mechanism of action of CBD is unclear, but it does not appear to involve the direct antagonism of dopamine receptors. Human and animal research study findings indicate that CBD has antipsychotic properties. McGuire et al4 assessed the safety and effectiveness of CBD as an adjunctive treatment of schizophrenia.

Study design

- In this double-blind parallel-group trial conducted at 15 hospitals in the United Kingdom, Romania, and Poland, 88 patients with schizophrenia received CBD (1,000 mg/d; N = 43) or placebo (N = 45) as adjunct to the antipsychotic medication they had been prescribed. Patients had previously demonstrated at least a partial response to antipsychotic treatment, and were taking stable doses of an antipsychotic for ≥4 weeks.

- Evaluations of symptoms, general functioning, cognitive performance, and EPS were completed at baseline and on Days 8, 22, and 43 (± 3 days). Current substance use was assessed using a semi-structured interview, and reassessed at the end of treatment.

- The key endpoints were the patients’ level of functioning, severity of symptoms, and cognitive performance. Participants were assessed before and after treatment using the PANSS, the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS), the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF), and the improvement and severity scales of the Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI-I and CGI-S, respectively).

- The clinicians’ impression of illness severity and symptom improvement and patient- or caregiver-reported impressions of general functioning and sleep also were noted.

Outcomes

- After 6 weeks, compared with the placebo group, the CBD group had lower levels of positive psychotic symptoms and were more likely to be rated as improved and as not severely unwell by the treating clinician. Patients in the CBD group also showed greater improvements in cognitive performance and in overall functioning, although these were not statistically significant.

- Similar levels of negative psychotic symptoms, overall psychopathology, and general psychopathology were observed in the CBD and placebo groups. The CBD group had a higher proportion of treatment responders (≥20% improvement in PANSS total score) than did the placebo group; however, the total number of responders per group was small (12 and 6 patients, respectively). At baseline, most patients in both groups were classified as moderately, markedly, or severely ill (83.4% in the CBD group vs 79.6% in placebo group). By the end of treatment, this decreased to 54.8% in the CBD group and 63.6% in the placebo group. Clinicians rated 78.6% of patients in the CBD group as “improved” on the CGI-I, compared with 54.6% of patients in the placebo group.

Conclusion