User login

Reimbursement for telemedicine services: A billing code disaster

In December 1917, a large part of Halifax was destroyed when an ammunition ship exploded.

In the wake of the explosion large parts of the city were burning. Surrounding communities’ fire departments raced to the scene, only to find their efforts thwarted by a lack of uniform standards for hydrant-hose-nozzle connectors. With no way to tap into Halifax’s water supply, their hoses were worthless.

In the aftermath of WWI, this led to a standardization of fire hose connectors across multiple countries, to ensure it wouldn’t happen again. Sometimes it takes a disaster to bring such problems to the forefront so they can be fixed.

One issue that has come up repeatedly in talking to other physicians is the complete lack of uniformity in telemedicine billing codes. While not a new issue, the coronavirus pandemic has brought it into focus here, and it’s time to fix it.

Here’s an example of information I’ve found about telemedicine billing codes (Note: I have no idea if any of this is correct, so don’t rely on it in your own billing).

- Aetna: Point of service 02

- Cigna: Point of service 02 with modifier 95.

- BCBS Anthem Point of Service 02 with modifier GT.

- Medicare: Point of service 02 OR Point of service 11 with modifier 95 (I’ve seen conflicting reports).

And that’s just a sample. BCBS, for example, seems to vary by state and sub-network.

This is ridiculous. Even with different plans, the CPT and ICD10 codes are standardized, so why not things such as POS codes and modifiers? The only ones benefiting from this are insurance companies, who get to deny claims on grounds that they weren’t billed correctly.

This is, allegedly, the Internet age. Medical bills are submitted electronically, and often paid the same way. If such a complicated system can be made to work in so many other ways, it should be standardized to benefit all involved. Including those doing our best to care for patients in this challenging time – and at all times.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In December 1917, a large part of Halifax was destroyed when an ammunition ship exploded.

In the wake of the explosion large parts of the city were burning. Surrounding communities’ fire departments raced to the scene, only to find their efforts thwarted by a lack of uniform standards for hydrant-hose-nozzle connectors. With no way to tap into Halifax’s water supply, their hoses were worthless.

In the aftermath of WWI, this led to a standardization of fire hose connectors across multiple countries, to ensure it wouldn’t happen again. Sometimes it takes a disaster to bring such problems to the forefront so they can be fixed.

One issue that has come up repeatedly in talking to other physicians is the complete lack of uniformity in telemedicine billing codes. While not a new issue, the coronavirus pandemic has brought it into focus here, and it’s time to fix it.

Here’s an example of information I’ve found about telemedicine billing codes (Note: I have no idea if any of this is correct, so don’t rely on it in your own billing).

- Aetna: Point of service 02

- Cigna: Point of service 02 with modifier 95.

- BCBS Anthem Point of Service 02 with modifier GT.

- Medicare: Point of service 02 OR Point of service 11 with modifier 95 (I’ve seen conflicting reports).

And that’s just a sample. BCBS, for example, seems to vary by state and sub-network.

This is ridiculous. Even with different plans, the CPT and ICD10 codes are standardized, so why not things such as POS codes and modifiers? The only ones benefiting from this are insurance companies, who get to deny claims on grounds that they weren’t billed correctly.

This is, allegedly, the Internet age. Medical bills are submitted electronically, and often paid the same way. If such a complicated system can be made to work in so many other ways, it should be standardized to benefit all involved. Including those doing our best to care for patients in this challenging time – and at all times.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In December 1917, a large part of Halifax was destroyed when an ammunition ship exploded.

In the wake of the explosion large parts of the city were burning. Surrounding communities’ fire departments raced to the scene, only to find their efforts thwarted by a lack of uniform standards for hydrant-hose-nozzle connectors. With no way to tap into Halifax’s water supply, their hoses were worthless.

In the aftermath of WWI, this led to a standardization of fire hose connectors across multiple countries, to ensure it wouldn’t happen again. Sometimes it takes a disaster to bring such problems to the forefront so they can be fixed.

One issue that has come up repeatedly in talking to other physicians is the complete lack of uniformity in telemedicine billing codes. While not a new issue, the coronavirus pandemic has brought it into focus here, and it’s time to fix it.

Here’s an example of information I’ve found about telemedicine billing codes (Note: I have no idea if any of this is correct, so don’t rely on it in your own billing).

- Aetna: Point of service 02

- Cigna: Point of service 02 with modifier 95.

- BCBS Anthem Point of Service 02 with modifier GT.

- Medicare: Point of service 02 OR Point of service 11 with modifier 95 (I’ve seen conflicting reports).

And that’s just a sample. BCBS, for example, seems to vary by state and sub-network.

This is ridiculous. Even with different plans, the CPT and ICD10 codes are standardized, so why not things such as POS codes and modifiers? The only ones benefiting from this are insurance companies, who get to deny claims on grounds that they weren’t billed correctly.

This is, allegedly, the Internet age. Medical bills are submitted electronically, and often paid the same way. If such a complicated system can be made to work in so many other ways, it should be standardized to benefit all involved. Including those doing our best to care for patients in this challenging time – and at all times.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

IBD: Steroids, but not TNF blockers, raise risk of severe COVID-19

For patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who develop coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), corticosteroid use may significantly increase risk of severe disease, according to data from more than 500 patients.

Use of sulfasalazine or 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) also increased risk of severe COVID-19, albeit to a lesser degree, reported co-lead authors Erica J. Brenner, MD, of University of North Carolina Children’s Hospital, Chapel Hill, and Ryan C. Ungaro, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and colleagues.

In contrast, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers were not an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19.

“As TNF antagonists are the most commonly prescribed biologic therapy for patients with IBD, these initial findings should be reassuring to the large number of patients receiving TNF antagonist therapy and support their continued use during this current pandemic,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

These conclusions were drawn from the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SECURE-IBD) database, a large registry actively collecting data from clinicians around the world.

In the present analysis, which involved 525 patients from 33 countries, the investigators searched for independent risk factors for severe COVID-19. Various factors were tested through multivariable regression, including age, comorbidities, usage of specific medications, and more.

The primary outcome was defined by a composite of hospitalization, ventilator use, or death, while secondary outcomes included a composite of hospitalization or death, as well as death alone.

The analysis revealed that patients receiving corticosteroids had an adjusted odds ratio of 6.87 (95% confidence interval, 2.30-20.51) for severe COVID-19, with increased risks also detected for both secondary outcomes. In contrast, TNF antagonist use was not significantly associated with the primary outcome; in fact, a possible protective effect was detected for hospitalization or death (aOR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38-0.96).

The investigators noted that the above findings aligned with extensive literature concerning infectious complications with corticosteroid use and “more recent commentary” surrounding TNF antagonists. Similarly, increased age and the presence of at least two comorbidities were each independently associated with increased risk of severe COVID-19, both of which are correlations that have been previously described.

But the threefold increased risk of severe COVID-19 associated with use of sulfasalazine or 5-ASAs (aOR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.28-7.71) was a “surprising” finding, the investigators noted.

“In a direct comparison, we observed that 5-ASA/sulfasalazine–treated patients fared worse than those treated with TNF inhibitors,” the investigators wrote. “Although we cannot exclude unmeasured confounding, further exploration of biological mechanisms is warranted.”

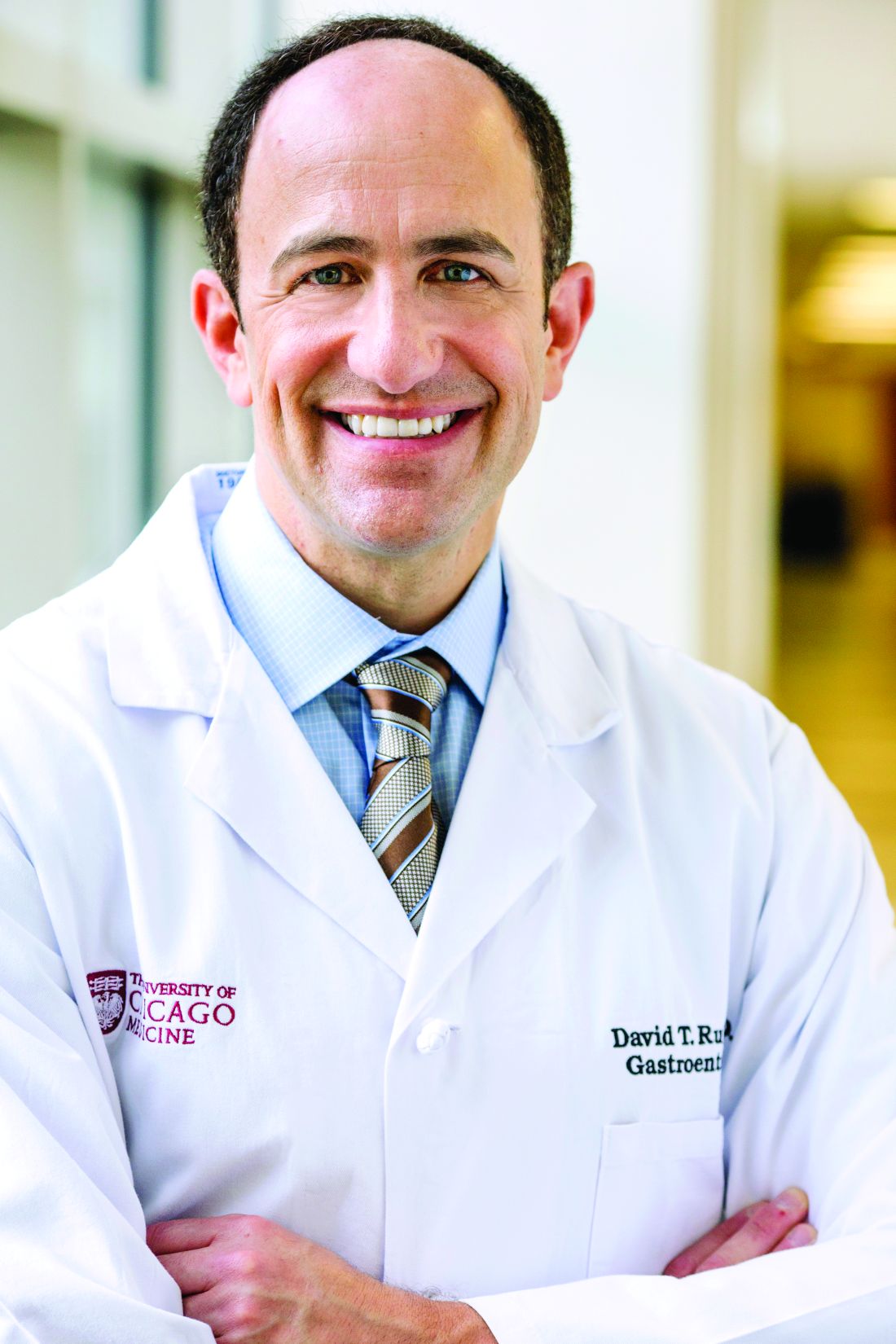

David T. Rubin, MD, of the University of Chicago agreed that the finding deserves further investigation, particularly since sulfasalazine and 5-ASAs represent the second most commonly prescribed medication class for IBD.

“The risk with 5-ASAs is of interest but not well explained by what we know about the safety or the mechanism of these therapies,” Dr. Rubin said. “Clearly, more work is needed.”

The risks associated with corticosteroids were particularly concerning, Dr. Rubin said, because 10%-20% of patients with IBD may be taking corticosteroids at any given time.

“Steroids are still the number one prescribed therapy for Crohn’s and colitis,” he said.

Still, Dr. Rubin advised against abrupt changes to drug regimens, especially if they are effectively controlling IBD.

“Patients should stay on their existing therapies and stay in remission,” Dr. Rubin said. “If you stop your therapies … you are more likely to relapse. When you relapse, you’re more likely to need steroids as a rescue therapy … or end up in the hospital, and those are not places we want you to be.”

Despite the risks associated with steroids and sulfasalazine/5-ASAs, Dr. Rubin had an optimistic take on the study, calling the findings “very reassuring” because they support continued usage of TNF inhibitors and other biologic agents during the pandemic. He also noted that the SECURE-IBD registry, which he has contributed to, represents “an extraordinary effort” from around the world.

“[This is] an unprecedented collaboration across a scale and timeframe that has really never been seen before in our field, and I would hazard a guess that it’s probably never been seen in most other fields right now,” he said.

Clinicians seeking more information about managing patients with IBD during the COVID-19 pandemic can find guidance in the recent AGA practice update, of which Dr. Rubin was the lead author. Clinicians who would like to contribute to the SECURE-IBD registry may do so at covidibd.org. The registry now includes more than 1,000 patients.

The study was funded by Clinical and Translational Science Award grants through Dr. Ungaro. The investigators disclosed relationships with Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, and others. Dr. Rubin disclosed relationships with Gilead, Eli Lilly, Shire, and others.

SOURCE: Brenner EJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.032.

For patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who develop coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), corticosteroid use may significantly increase risk of severe disease, according to data from more than 500 patients.

Use of sulfasalazine or 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) also increased risk of severe COVID-19, albeit to a lesser degree, reported co-lead authors Erica J. Brenner, MD, of University of North Carolina Children’s Hospital, Chapel Hill, and Ryan C. Ungaro, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and colleagues.

In contrast, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers were not an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19.

“As TNF antagonists are the most commonly prescribed biologic therapy for patients with IBD, these initial findings should be reassuring to the large number of patients receiving TNF antagonist therapy and support their continued use during this current pandemic,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

These conclusions were drawn from the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SECURE-IBD) database, a large registry actively collecting data from clinicians around the world.

In the present analysis, which involved 525 patients from 33 countries, the investigators searched for independent risk factors for severe COVID-19. Various factors were tested through multivariable regression, including age, comorbidities, usage of specific medications, and more.

The primary outcome was defined by a composite of hospitalization, ventilator use, or death, while secondary outcomes included a composite of hospitalization or death, as well as death alone.

The analysis revealed that patients receiving corticosteroids had an adjusted odds ratio of 6.87 (95% confidence interval, 2.30-20.51) for severe COVID-19, with increased risks also detected for both secondary outcomes. In contrast, TNF antagonist use was not significantly associated with the primary outcome; in fact, a possible protective effect was detected for hospitalization or death (aOR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38-0.96).

The investigators noted that the above findings aligned with extensive literature concerning infectious complications with corticosteroid use and “more recent commentary” surrounding TNF antagonists. Similarly, increased age and the presence of at least two comorbidities were each independently associated with increased risk of severe COVID-19, both of which are correlations that have been previously described.

But the threefold increased risk of severe COVID-19 associated with use of sulfasalazine or 5-ASAs (aOR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.28-7.71) was a “surprising” finding, the investigators noted.

“In a direct comparison, we observed that 5-ASA/sulfasalazine–treated patients fared worse than those treated with TNF inhibitors,” the investigators wrote. “Although we cannot exclude unmeasured confounding, further exploration of biological mechanisms is warranted.”

David T. Rubin, MD, of the University of Chicago agreed that the finding deserves further investigation, particularly since sulfasalazine and 5-ASAs represent the second most commonly prescribed medication class for IBD.

“The risk with 5-ASAs is of interest but not well explained by what we know about the safety or the mechanism of these therapies,” Dr. Rubin said. “Clearly, more work is needed.”

The risks associated with corticosteroids were particularly concerning, Dr. Rubin said, because 10%-20% of patients with IBD may be taking corticosteroids at any given time.

“Steroids are still the number one prescribed therapy for Crohn’s and colitis,” he said.

Still, Dr. Rubin advised against abrupt changes to drug regimens, especially if they are effectively controlling IBD.

“Patients should stay on their existing therapies and stay in remission,” Dr. Rubin said. “If you stop your therapies … you are more likely to relapse. When you relapse, you’re more likely to need steroids as a rescue therapy … or end up in the hospital, and those are not places we want you to be.”

Despite the risks associated with steroids and sulfasalazine/5-ASAs, Dr. Rubin had an optimistic take on the study, calling the findings “very reassuring” because they support continued usage of TNF inhibitors and other biologic agents during the pandemic. He also noted that the SECURE-IBD registry, which he has contributed to, represents “an extraordinary effort” from around the world.

“[This is] an unprecedented collaboration across a scale and timeframe that has really never been seen before in our field, and I would hazard a guess that it’s probably never been seen in most other fields right now,” he said.

Clinicians seeking more information about managing patients with IBD during the COVID-19 pandemic can find guidance in the recent AGA practice update, of which Dr. Rubin was the lead author. Clinicians who would like to contribute to the SECURE-IBD registry may do so at covidibd.org. The registry now includes more than 1,000 patients.

The study was funded by Clinical and Translational Science Award grants through Dr. Ungaro. The investigators disclosed relationships with Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, and others. Dr. Rubin disclosed relationships with Gilead, Eli Lilly, Shire, and others.

SOURCE: Brenner EJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.032.

For patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who develop coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), corticosteroid use may significantly increase risk of severe disease, according to data from more than 500 patients.

Use of sulfasalazine or 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) also increased risk of severe COVID-19, albeit to a lesser degree, reported co-lead authors Erica J. Brenner, MD, of University of North Carolina Children’s Hospital, Chapel Hill, and Ryan C. Ungaro, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and colleagues.

In contrast, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers were not an independent risk factor for severe COVID-19.

“As TNF antagonists are the most commonly prescribed biologic therapy for patients with IBD, these initial findings should be reassuring to the large number of patients receiving TNF antagonist therapy and support their continued use during this current pandemic,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

These conclusions were drawn from the Surveillance Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SECURE-IBD) database, a large registry actively collecting data from clinicians around the world.

In the present analysis, which involved 525 patients from 33 countries, the investigators searched for independent risk factors for severe COVID-19. Various factors were tested through multivariable regression, including age, comorbidities, usage of specific medications, and more.

The primary outcome was defined by a composite of hospitalization, ventilator use, or death, while secondary outcomes included a composite of hospitalization or death, as well as death alone.

The analysis revealed that patients receiving corticosteroids had an adjusted odds ratio of 6.87 (95% confidence interval, 2.30-20.51) for severe COVID-19, with increased risks also detected for both secondary outcomes. In contrast, TNF antagonist use was not significantly associated with the primary outcome; in fact, a possible protective effect was detected for hospitalization or death (aOR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38-0.96).

The investigators noted that the above findings aligned with extensive literature concerning infectious complications with corticosteroid use and “more recent commentary” surrounding TNF antagonists. Similarly, increased age and the presence of at least two comorbidities were each independently associated with increased risk of severe COVID-19, both of which are correlations that have been previously described.

But the threefold increased risk of severe COVID-19 associated with use of sulfasalazine or 5-ASAs (aOR, 3.14; 95% CI, 1.28-7.71) was a “surprising” finding, the investigators noted.

“In a direct comparison, we observed that 5-ASA/sulfasalazine–treated patients fared worse than those treated with TNF inhibitors,” the investigators wrote. “Although we cannot exclude unmeasured confounding, further exploration of biological mechanisms is warranted.”

David T. Rubin, MD, of the University of Chicago agreed that the finding deserves further investigation, particularly since sulfasalazine and 5-ASAs represent the second most commonly prescribed medication class for IBD.

“The risk with 5-ASAs is of interest but not well explained by what we know about the safety or the mechanism of these therapies,” Dr. Rubin said. “Clearly, more work is needed.”

The risks associated with corticosteroids were particularly concerning, Dr. Rubin said, because 10%-20% of patients with IBD may be taking corticosteroids at any given time.

“Steroids are still the number one prescribed therapy for Crohn’s and colitis,” he said.

Still, Dr. Rubin advised against abrupt changes to drug regimens, especially if they are effectively controlling IBD.

“Patients should stay on their existing therapies and stay in remission,” Dr. Rubin said. “If you stop your therapies … you are more likely to relapse. When you relapse, you’re more likely to need steroids as a rescue therapy … or end up in the hospital, and those are not places we want you to be.”

Despite the risks associated with steroids and sulfasalazine/5-ASAs, Dr. Rubin had an optimistic take on the study, calling the findings “very reassuring” because they support continued usage of TNF inhibitors and other biologic agents during the pandemic. He also noted that the SECURE-IBD registry, which he has contributed to, represents “an extraordinary effort” from around the world.

“[This is] an unprecedented collaboration across a scale and timeframe that has really never been seen before in our field, and I would hazard a guess that it’s probably never been seen in most other fields right now,” he said.

Clinicians seeking more information about managing patients with IBD during the COVID-19 pandemic can find guidance in the recent AGA practice update, of which Dr. Rubin was the lead author. Clinicians who would like to contribute to the SECURE-IBD registry may do so at covidibd.org. The registry now includes more than 1,000 patients.

The study was funded by Clinical and Translational Science Award grants through Dr. Ungaro. The investigators disclosed relationships with Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, and others. Dr. Rubin disclosed relationships with Gilead, Eli Lilly, Shire, and others.

SOURCE: Brenner EJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.032.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Is HIPAA critical?

Ignorance may be bliss for some. But as I sit here in my scenic social isolation on the Maine coast I find that, like most people, what I don’t know unsettles me. How is the COVID-19 virus spread? Does my wife’s wipe down of the doorknobs after I return from the grocery store really make us any less likely to contract the virus? Is wearing my homemade bandana face mask doing anything to protect me? I suspect not, but I wear it as a statement of courtesy and solidarity to my fellow community members.

Does the 6-foot rule make any sense? I’ve read that it is based on a study dating back to the 1930s. I’ve seen images of the 25-foot droplet plume blasting out from a sneeze and understand that, as a bicyclist, I may be generating a shower of droplets in my wake. But, are those droplets a threat to anyone I pedal by if I am symptom free? What does being a carrier mean when we are talking about COVID-19?

What makes me more vulnerable to this particular virus as an apparently healthy septuagenarian? What collection of misfortunes have fallen on those younger victims of the pandemic? How often was it genetic?

Of course, none of us has the information yet that can provide us answers. This vacuum has attracted scores of “experts” bold enough or careless enough to venture an opinion. They may have also issued a caveat, but how often have the media failed to include it in the report or buried it in the fine print at the end of the story?

My discomfort with this information void has left me and you and everyone else to our imaginations to craft our own explanations. So, I try to piece together a construct based on what I can glean from what I read and see in the news because like most people I fortunately have no first-hand information about even a single case. The number of deaths is horrifying, but may not have hit close to home and given most of us a real personal sense of the illness and its character.

Maine is a small state with just over a million inhabitants, and most of us have some connection to one another. It may be that a person is the second cousin of someone who used to live 2 miles down the road. But, there is some feeling of familiarity. We have had deaths related to COVID-19, but very scanty information other than the county about where they occurred and whether the victim was a resident of an extended care facility. We are told very little if any details about exposure as officials invoke HIPAA regulations that leave us in the dark. Other than one vague reference to a “traveling salesman” who may have introduced the virus to several nursing homes, there has been very little information about how the virus may have been spread here in Maine. Even national reports of the deaths of high-profile entertainers and retired athletes are usually draped in the same haze of privacy.

Most of us don’t need to know the names and street addresses of the victims but a few anonymous narratives that include some general information on how epidemiologists believe clusters began and propagated would help us understand our risks with just a glimmer of clarity.

Of course the epidemiologists may not have the answers we are seeking because they too are struggling to untangle connections hampered by concerns of privacy. There is no question that privacy must remain an important part of the physician-patient relationship. But a pandemic has thrown us into a situation where common sense demands that HIPAA be interpreted with an emphasis on the greater good. Finding that balance between privacy and public knowledge will continue to be one of our greatest challenges.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Ignorance may be bliss for some. But as I sit here in my scenic social isolation on the Maine coast I find that, like most people, what I don’t know unsettles me. How is the COVID-19 virus spread? Does my wife’s wipe down of the doorknobs after I return from the grocery store really make us any less likely to contract the virus? Is wearing my homemade bandana face mask doing anything to protect me? I suspect not, but I wear it as a statement of courtesy and solidarity to my fellow community members.

Does the 6-foot rule make any sense? I’ve read that it is based on a study dating back to the 1930s. I’ve seen images of the 25-foot droplet plume blasting out from a sneeze and understand that, as a bicyclist, I may be generating a shower of droplets in my wake. But, are those droplets a threat to anyone I pedal by if I am symptom free? What does being a carrier mean when we are talking about COVID-19?

What makes me more vulnerable to this particular virus as an apparently healthy septuagenarian? What collection of misfortunes have fallen on those younger victims of the pandemic? How often was it genetic?

Of course, none of us has the information yet that can provide us answers. This vacuum has attracted scores of “experts” bold enough or careless enough to venture an opinion. They may have also issued a caveat, but how often have the media failed to include it in the report or buried it in the fine print at the end of the story?

My discomfort with this information void has left me and you and everyone else to our imaginations to craft our own explanations. So, I try to piece together a construct based on what I can glean from what I read and see in the news because like most people I fortunately have no first-hand information about even a single case. The number of deaths is horrifying, but may not have hit close to home and given most of us a real personal sense of the illness and its character.

Maine is a small state with just over a million inhabitants, and most of us have some connection to one another. It may be that a person is the second cousin of someone who used to live 2 miles down the road. But, there is some feeling of familiarity. We have had deaths related to COVID-19, but very scanty information other than the county about where they occurred and whether the victim was a resident of an extended care facility. We are told very little if any details about exposure as officials invoke HIPAA regulations that leave us in the dark. Other than one vague reference to a “traveling salesman” who may have introduced the virus to several nursing homes, there has been very little information about how the virus may have been spread here in Maine. Even national reports of the deaths of high-profile entertainers and retired athletes are usually draped in the same haze of privacy.

Most of us don’t need to know the names and street addresses of the victims but a few anonymous narratives that include some general information on how epidemiologists believe clusters began and propagated would help us understand our risks with just a glimmer of clarity.

Of course the epidemiologists may not have the answers we are seeking because they too are struggling to untangle connections hampered by concerns of privacy. There is no question that privacy must remain an important part of the physician-patient relationship. But a pandemic has thrown us into a situation where common sense demands that HIPAA be interpreted with an emphasis on the greater good. Finding that balance between privacy and public knowledge will continue to be one of our greatest challenges.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Ignorance may be bliss for some. But as I sit here in my scenic social isolation on the Maine coast I find that, like most people, what I don’t know unsettles me. How is the COVID-19 virus spread? Does my wife’s wipe down of the doorknobs after I return from the grocery store really make us any less likely to contract the virus? Is wearing my homemade bandana face mask doing anything to protect me? I suspect not, but I wear it as a statement of courtesy and solidarity to my fellow community members.

Does the 6-foot rule make any sense? I’ve read that it is based on a study dating back to the 1930s. I’ve seen images of the 25-foot droplet plume blasting out from a sneeze and understand that, as a bicyclist, I may be generating a shower of droplets in my wake. But, are those droplets a threat to anyone I pedal by if I am symptom free? What does being a carrier mean when we are talking about COVID-19?

What makes me more vulnerable to this particular virus as an apparently healthy septuagenarian? What collection of misfortunes have fallen on those younger victims of the pandemic? How often was it genetic?

Of course, none of us has the information yet that can provide us answers. This vacuum has attracted scores of “experts” bold enough or careless enough to venture an opinion. They may have also issued a caveat, but how often have the media failed to include it in the report or buried it in the fine print at the end of the story?

My discomfort with this information void has left me and you and everyone else to our imaginations to craft our own explanations. So, I try to piece together a construct based on what I can glean from what I read and see in the news because like most people I fortunately have no first-hand information about even a single case. The number of deaths is horrifying, but may not have hit close to home and given most of us a real personal sense of the illness and its character.

Maine is a small state with just over a million inhabitants, and most of us have some connection to one another. It may be that a person is the second cousin of someone who used to live 2 miles down the road. But, there is some feeling of familiarity. We have had deaths related to COVID-19, but very scanty information other than the county about where they occurred and whether the victim was a resident of an extended care facility. We are told very little if any details about exposure as officials invoke HIPAA regulations that leave us in the dark. Other than one vague reference to a “traveling salesman” who may have introduced the virus to several nursing homes, there has been very little information about how the virus may have been spread here in Maine. Even national reports of the deaths of high-profile entertainers and retired athletes are usually draped in the same haze of privacy.

Most of us don’t need to know the names and street addresses of the victims but a few anonymous narratives that include some general information on how epidemiologists believe clusters began and propagated would help us understand our risks with just a glimmer of clarity.

Of course the epidemiologists may not have the answers we are seeking because they too are struggling to untangle connections hampered by concerns of privacy. There is no question that privacy must remain an important part of the physician-patient relationship. But a pandemic has thrown us into a situation where common sense demands that HIPAA be interpreted with an emphasis on the greater good. Finding that balance between privacy and public knowledge will continue to be one of our greatest challenges.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

ARBs didn't raise suicide risk in large VA study

Angiotensin receptor blocker therapy was not associated with any hint of increased risk of suicide, compared with treatment with an ACE inhibitor, in a large national Veterans Affairs study, Kallisse R. Dent, MPH, reported at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association of Suicidology.

The VA study thus fails to confirm the results of an earlier Canadian, population-based, nested case-control study, which concluded that exposure to an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) was independently associated with an adjusted 63% increase risk of death by suicide, compared with ACE inhibitor users. The Canadian study drew considerable attention, noted Ms. Dent, of the VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention.

The Canadian study included 964 Ontario residents who died by suicide within 100 days of receiving an ACE inhibitor or ARB. They were matched by age, sex, and the presence of hypertension and diabetes to 3,856 controls, all of whom were on an ACE inhibitor or ARB for the 100 days prior to the patient’s suicide. All subjects were aged at least 66 years.

The Canadian investigators recommended that ACE inhibitors should be used instead of ARBs whenever possible, particularly in patients with major mental illness (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 2;2[10]:e1913304). This was a study that demanded replication because of the enormous potential impact that recommendation could have upon clinical care. ACE inhibitors and ARBs are among the most widely prescribed of all medications, with approved indications for treatment of hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and heart failure, Ms. Dent observed.

The Canadian investigators noted that a differential effect on suicide risk for the two drug classes was mechanistically plausible. Those drugs can cross the blood-brain barrier to varying extents, where they could conceivably interfere with central angiotensin II activity, which in turn could result in increased activity of substance P, as well as anxiety and stress secondary to increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Ms. Dent and coinvestigators harnessed VA suicide surveillance resources to conduct a nested case-control study that included all 1,311 deaths by suicide during 2015-2017 among patients in the VA system who had an active prescription for an ACE inhibitor or ARB during the 100 days immediately prior to death. As in the Canadian study, these individuals were matched 4:1 to 5,243 controls who did not die by suicide and had an active prescription for an ARB or ACE inhibitor during the 100 days prior to the date of suicide.

Those rates were not significantly different from the rates found in controls, 21.6% of whom were on an ARB and 78.4% were on an ACE inhibitor. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the same potential confounders included in the Canadian study – including Charlson Comorbidity Index score; drug use; and diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, coronary artery disease, stroke, and chronic liver or kidney disease – being on an ARB was associated with a 9% lower risk of suicide than being on an ACE inhibitor, a nonsignificant difference.

A point of pride for the investigators was that, because of the VA’s sophisticated patient care database and comprehensive suicide analytics, the VA researchers were able to very quickly determine the lack of generalizability of the Canadian findings to a different patient population. Indeed, the entire VA case-control study was completed in less than 2 months.

Ms. Dent reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was sponsored by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Angiotensin receptor blocker therapy was not associated with any hint of increased risk of suicide, compared with treatment with an ACE inhibitor, in a large national Veterans Affairs study, Kallisse R. Dent, MPH, reported at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association of Suicidology.

The VA study thus fails to confirm the results of an earlier Canadian, population-based, nested case-control study, which concluded that exposure to an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) was independently associated with an adjusted 63% increase risk of death by suicide, compared with ACE inhibitor users. The Canadian study drew considerable attention, noted Ms. Dent, of the VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention.

The Canadian study included 964 Ontario residents who died by suicide within 100 days of receiving an ACE inhibitor or ARB. They were matched by age, sex, and the presence of hypertension and diabetes to 3,856 controls, all of whom were on an ACE inhibitor or ARB for the 100 days prior to the patient’s suicide. All subjects were aged at least 66 years.

The Canadian investigators recommended that ACE inhibitors should be used instead of ARBs whenever possible, particularly in patients with major mental illness (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 2;2[10]:e1913304). This was a study that demanded replication because of the enormous potential impact that recommendation could have upon clinical care. ACE inhibitors and ARBs are among the most widely prescribed of all medications, with approved indications for treatment of hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and heart failure, Ms. Dent observed.

The Canadian investigators noted that a differential effect on suicide risk for the two drug classes was mechanistically plausible. Those drugs can cross the blood-brain barrier to varying extents, where they could conceivably interfere with central angiotensin II activity, which in turn could result in increased activity of substance P, as well as anxiety and stress secondary to increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Ms. Dent and coinvestigators harnessed VA suicide surveillance resources to conduct a nested case-control study that included all 1,311 deaths by suicide during 2015-2017 among patients in the VA system who had an active prescription for an ACE inhibitor or ARB during the 100 days immediately prior to death. As in the Canadian study, these individuals were matched 4:1 to 5,243 controls who did not die by suicide and had an active prescription for an ARB or ACE inhibitor during the 100 days prior to the date of suicide.

Those rates were not significantly different from the rates found in controls, 21.6% of whom were on an ARB and 78.4% were on an ACE inhibitor. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the same potential confounders included in the Canadian study – including Charlson Comorbidity Index score; drug use; and diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, coronary artery disease, stroke, and chronic liver or kidney disease – being on an ARB was associated with a 9% lower risk of suicide than being on an ACE inhibitor, a nonsignificant difference.

A point of pride for the investigators was that, because of the VA’s sophisticated patient care database and comprehensive suicide analytics, the VA researchers were able to very quickly determine the lack of generalizability of the Canadian findings to a different patient population. Indeed, the entire VA case-control study was completed in less than 2 months.

Ms. Dent reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was sponsored by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Angiotensin receptor blocker therapy was not associated with any hint of increased risk of suicide, compared with treatment with an ACE inhibitor, in a large national Veterans Affairs study, Kallisse R. Dent, MPH, reported at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association of Suicidology.

The VA study thus fails to confirm the results of an earlier Canadian, population-based, nested case-control study, which concluded that exposure to an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) was independently associated with an adjusted 63% increase risk of death by suicide, compared with ACE inhibitor users. The Canadian study drew considerable attention, noted Ms. Dent, of the VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention.

The Canadian study included 964 Ontario residents who died by suicide within 100 days of receiving an ACE inhibitor or ARB. They were matched by age, sex, and the presence of hypertension and diabetes to 3,856 controls, all of whom were on an ACE inhibitor or ARB for the 100 days prior to the patient’s suicide. All subjects were aged at least 66 years.

The Canadian investigators recommended that ACE inhibitors should be used instead of ARBs whenever possible, particularly in patients with major mental illness (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 2;2[10]:e1913304). This was a study that demanded replication because of the enormous potential impact that recommendation could have upon clinical care. ACE inhibitors and ARBs are among the most widely prescribed of all medications, with approved indications for treatment of hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and heart failure, Ms. Dent observed.

The Canadian investigators noted that a differential effect on suicide risk for the two drug classes was mechanistically plausible. Those drugs can cross the blood-brain barrier to varying extents, where they could conceivably interfere with central angiotensin II activity, which in turn could result in increased activity of substance P, as well as anxiety and stress secondary to increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Ms. Dent and coinvestigators harnessed VA suicide surveillance resources to conduct a nested case-control study that included all 1,311 deaths by suicide during 2015-2017 among patients in the VA system who had an active prescription for an ACE inhibitor or ARB during the 100 days immediately prior to death. As in the Canadian study, these individuals were matched 4:1 to 5,243 controls who did not die by suicide and had an active prescription for an ARB or ACE inhibitor during the 100 days prior to the date of suicide.

Those rates were not significantly different from the rates found in controls, 21.6% of whom were on an ARB and 78.4% were on an ACE inhibitor. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the same potential confounders included in the Canadian study – including Charlson Comorbidity Index score; drug use; and diagnosis of alcohol use disorder, coronary artery disease, stroke, and chronic liver or kidney disease – being on an ARB was associated with a 9% lower risk of suicide than being on an ACE inhibitor, a nonsignificant difference.

A point of pride for the investigators was that, because of the VA’s sophisticated patient care database and comprehensive suicide analytics, the VA researchers were able to very quickly determine the lack of generalizability of the Canadian findings to a different patient population. Indeed, the entire VA case-control study was completed in less than 2 months.

Ms. Dent reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was sponsored by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

FROM AAS20

New rosacea clinical management guidelines focus on symptomatology

, as was previously practiced, according to an update on options for managing rosacea published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The update, by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee, is based on a review of the evidence, and is a follow-up to the classification system for rosacea that was updated in 2017, which recommended classification of rosacea based on phenotype (Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155).

The key take-away is “that patients shouldn’t be classified as having a certain subtype of rosacea” since “many patients have features that overlap more than one subtype,” lead author of the management update, Diane Thiboutot, MD, professor of dermatology and associate dean of clinical and translational research education at Penn State University, Hershey, said in an interview.

“There is an opportunity for physicians to recognize that the symptom complex of rosacea differs widely and treatments should be selected to address the symptoms experienced by the patient, particularly with regard to ocular rosacea,” she said.

Until there were updated guidelines on rosacea classification, published in 2018, relying primarily on diagnostic subtypes “tended to limit consideration of the full range of potential signs and symptoms as well as the frequent simultaneous occurrence of more than one subtype or the potential progression from one subtype to another,” Dr. Thiboutot and coauthors wrote in the management update (J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82:1501-10).

“The more we learn, the more complex rosacea becomes,” she said in the interview. “The clinical manifestations of rosacea are so varied, ranging from skin erythema, eye findings, papules and pustules to rhinophyma, [that] it calls into question, if all of these are actually one disease (rosacea) or if they represent localized reaction patterns to a multitude of stimuli that vary among individuals.”

Etiology and impact

Dr. Thiboutot and colleagues summarized the management options and recommendations from a committee of 27 experts who assessed the data on rosacea therapies using the updated standard classification system. They also highlighted the suspected systemic nature of rosacea etiology and its psychosocial impact on those with the condition.

“Recent studies have found an association between rosacea and increased risk of a growing number of systemic disorders, including cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, neurologic, and autoimmune diseases as well as certain types of cancer,” the authors wrote. “These findings further elevate the clinical significance of rosacea as growing evidence of its potential link with systemic inflammation is increasingly understood.”

Dr. Thiboutot said that research has implicated both the innate and adaptive immune systems and the neuromuscular system in rosacea’s underpinnings.

“Many of the triggers associated with clinical exacerbation of rosacea are known to activate the immune system and/or the neurovasculature, such as demodex, sunlight, alcohol, and changes in temperature,” she said, adding that therapies targeting the neurovascular effects of rosacea are particularly needed.

More than 50% of patients with rosacea have ocular manifestations, with symptoms such as “dryness, burning and stinging, light sensitivity, blurred vision, and foreign body sensation,” the authors reported.

Diagnosis and management

Without definitive laboratory tests, it’s essential that the clinical diagnosis takes into account not only the physical examination findings, but also patient history, the authors stressed, since “some features may not be visually evident or present at the time of the patient’s visit.”

The authors also recommend taking into account patients’ perception and response to their appearance and its effects on their emotional, social, and professional lives when selecting interventions.

“Rosacea’s unsightly and conspicuous appearance often has significant emotional ramifications, potentially resulting in depression or anxiety, and frequently interferes with social and occupational interactions,” the authors wrote. “It may also be advisable to remind patients that normalization of skin tone and color is the goal rather than complete eradication of facial coloration, which can leave the face with a sallow appearance.”

Therapy will often require multiple agents, such as topical and oral agents for inflammatory papules/pustules of rosacea. If insufficient, adjunctive therapy with oral antibiotics or retinoids may be options, though the latter requires prevention of pregnancy during treatment. The authors also discussed pharmacological treatments for facial erythema and flushing, with all these drugs organized in tables according to symptoms and their levels of evidence and effectiveness.

Despite limited clinical evidence, the authors noted success with two types of laser therapy – pulsed-dye and potassium titanyl phosphate – for telangiectasia and erythema. They also noted the option of intense pulsed light for flushing, ocular symptoms, and meibomian gland dysfunction, and of ablative lasers for rhinophymatous nose. But they highlighted the importance of being cautious when using these therapies on darker skin.

In their discussion of ocular rosacea, the authors described the various manifestations and the two “mainstays” of treatment: “eyelash hygiene and oral [omega-3] supplementation, followed by topical azithromycin or calcineurin inhibitors.” In addition to pharmacological and light therapy options, attention to environmental contributors and conscientious skin care regimens can benefit patients with rosacea as well.

“Clinicians may advise patients to keep a daily diary of lifestyle and environmental factors that appear to affect their rosacea to help identify and avoid their personal triggers,” the authors wrote. “The most common factors are sun exposure, emotional stress, hot weather, wind, heavy exercise, alcohol consumption, hot baths, cold weather, spicy foods, humidity, indoor heat, certain skin-care products, heated beverages, certain medications, medical conditions, certain fruits, marinated meats, certain vegetables, and dairy products.”

The paper also emphasizes the importance of gentle skin care given the highly sensitive and easily irritated skin of patients with rosacea. Sunscreen use, particularly with mineral sunscreens that provide physical barriers and reflect ultraviolet light, should be a key aspect of patients’ skin care, and clinicians should advise patients to seek out gentle, nonirritating cleansers.

Funding was provided by the National Rosacea Society, which receives funding from patients and corporations that include Aclaris Therapeutics, Allergan, Bayer, Cutanea Life Sciences, and Galderma Laboratories. Dr. Thiboutot consults for Galderma. Six of the other nine coauthors have financial links to industry through advisory boards, consulting, or research funding.

SOURCE: Thiboutot D et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-10.

, as was previously practiced, according to an update on options for managing rosacea published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The update, by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee, is based on a review of the evidence, and is a follow-up to the classification system for rosacea that was updated in 2017, which recommended classification of rosacea based on phenotype (Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155).

The key take-away is “that patients shouldn’t be classified as having a certain subtype of rosacea” since “many patients have features that overlap more than one subtype,” lead author of the management update, Diane Thiboutot, MD, professor of dermatology and associate dean of clinical and translational research education at Penn State University, Hershey, said in an interview.

“There is an opportunity for physicians to recognize that the symptom complex of rosacea differs widely and treatments should be selected to address the symptoms experienced by the patient, particularly with regard to ocular rosacea,” she said.

Until there were updated guidelines on rosacea classification, published in 2018, relying primarily on diagnostic subtypes “tended to limit consideration of the full range of potential signs and symptoms as well as the frequent simultaneous occurrence of more than one subtype or the potential progression from one subtype to another,” Dr. Thiboutot and coauthors wrote in the management update (J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82:1501-10).

“The more we learn, the more complex rosacea becomes,” she said in the interview. “The clinical manifestations of rosacea are so varied, ranging from skin erythema, eye findings, papules and pustules to rhinophyma, [that] it calls into question, if all of these are actually one disease (rosacea) or if they represent localized reaction patterns to a multitude of stimuli that vary among individuals.”

Etiology and impact

Dr. Thiboutot and colleagues summarized the management options and recommendations from a committee of 27 experts who assessed the data on rosacea therapies using the updated standard classification system. They also highlighted the suspected systemic nature of rosacea etiology and its psychosocial impact on those with the condition.

“Recent studies have found an association between rosacea and increased risk of a growing number of systemic disorders, including cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, neurologic, and autoimmune diseases as well as certain types of cancer,” the authors wrote. “These findings further elevate the clinical significance of rosacea as growing evidence of its potential link with systemic inflammation is increasingly understood.”

Dr. Thiboutot said that research has implicated both the innate and adaptive immune systems and the neuromuscular system in rosacea’s underpinnings.

“Many of the triggers associated with clinical exacerbation of rosacea are known to activate the immune system and/or the neurovasculature, such as demodex, sunlight, alcohol, and changes in temperature,” she said, adding that therapies targeting the neurovascular effects of rosacea are particularly needed.

More than 50% of patients with rosacea have ocular manifestations, with symptoms such as “dryness, burning and stinging, light sensitivity, blurred vision, and foreign body sensation,” the authors reported.

Diagnosis and management

Without definitive laboratory tests, it’s essential that the clinical diagnosis takes into account not only the physical examination findings, but also patient history, the authors stressed, since “some features may not be visually evident or present at the time of the patient’s visit.”

The authors also recommend taking into account patients’ perception and response to their appearance and its effects on their emotional, social, and professional lives when selecting interventions.

“Rosacea’s unsightly and conspicuous appearance often has significant emotional ramifications, potentially resulting in depression or anxiety, and frequently interferes with social and occupational interactions,” the authors wrote. “It may also be advisable to remind patients that normalization of skin tone and color is the goal rather than complete eradication of facial coloration, which can leave the face with a sallow appearance.”

Therapy will often require multiple agents, such as topical and oral agents for inflammatory papules/pustules of rosacea. If insufficient, adjunctive therapy with oral antibiotics or retinoids may be options, though the latter requires prevention of pregnancy during treatment. The authors also discussed pharmacological treatments for facial erythema and flushing, with all these drugs organized in tables according to symptoms and their levels of evidence and effectiveness.

Despite limited clinical evidence, the authors noted success with two types of laser therapy – pulsed-dye and potassium titanyl phosphate – for telangiectasia and erythema. They also noted the option of intense pulsed light for flushing, ocular symptoms, and meibomian gland dysfunction, and of ablative lasers for rhinophymatous nose. But they highlighted the importance of being cautious when using these therapies on darker skin.

In their discussion of ocular rosacea, the authors described the various manifestations and the two “mainstays” of treatment: “eyelash hygiene and oral [omega-3] supplementation, followed by topical azithromycin or calcineurin inhibitors.” In addition to pharmacological and light therapy options, attention to environmental contributors and conscientious skin care regimens can benefit patients with rosacea as well.

“Clinicians may advise patients to keep a daily diary of lifestyle and environmental factors that appear to affect their rosacea to help identify and avoid their personal triggers,” the authors wrote. “The most common factors are sun exposure, emotional stress, hot weather, wind, heavy exercise, alcohol consumption, hot baths, cold weather, spicy foods, humidity, indoor heat, certain skin-care products, heated beverages, certain medications, medical conditions, certain fruits, marinated meats, certain vegetables, and dairy products.”

The paper also emphasizes the importance of gentle skin care given the highly sensitive and easily irritated skin of patients with rosacea. Sunscreen use, particularly with mineral sunscreens that provide physical barriers and reflect ultraviolet light, should be a key aspect of patients’ skin care, and clinicians should advise patients to seek out gentle, nonirritating cleansers.

Funding was provided by the National Rosacea Society, which receives funding from patients and corporations that include Aclaris Therapeutics, Allergan, Bayer, Cutanea Life Sciences, and Galderma Laboratories. Dr. Thiboutot consults for Galderma. Six of the other nine coauthors have financial links to industry through advisory boards, consulting, or research funding.

SOURCE: Thiboutot D et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-10.

, as was previously practiced, according to an update on options for managing rosacea published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The update, by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee, is based on a review of the evidence, and is a follow-up to the classification system for rosacea that was updated in 2017, which recommended classification of rosacea based on phenotype (Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155).

The key take-away is “that patients shouldn’t be classified as having a certain subtype of rosacea” since “many patients have features that overlap more than one subtype,” lead author of the management update, Diane Thiboutot, MD, professor of dermatology and associate dean of clinical and translational research education at Penn State University, Hershey, said in an interview.

“There is an opportunity for physicians to recognize that the symptom complex of rosacea differs widely and treatments should be selected to address the symptoms experienced by the patient, particularly with regard to ocular rosacea,” she said.

Until there were updated guidelines on rosacea classification, published in 2018, relying primarily on diagnostic subtypes “tended to limit consideration of the full range of potential signs and symptoms as well as the frequent simultaneous occurrence of more than one subtype or the potential progression from one subtype to another,” Dr. Thiboutot and coauthors wrote in the management update (J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82:1501-10).

“The more we learn, the more complex rosacea becomes,” she said in the interview. “The clinical manifestations of rosacea are so varied, ranging from skin erythema, eye findings, papules and pustules to rhinophyma, [that] it calls into question, if all of these are actually one disease (rosacea) or if they represent localized reaction patterns to a multitude of stimuli that vary among individuals.”

Etiology and impact

Dr. Thiboutot and colleagues summarized the management options and recommendations from a committee of 27 experts who assessed the data on rosacea therapies using the updated standard classification system. They also highlighted the suspected systemic nature of rosacea etiology and its psychosocial impact on those with the condition.

“Recent studies have found an association between rosacea and increased risk of a growing number of systemic disorders, including cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, neurologic, and autoimmune diseases as well as certain types of cancer,” the authors wrote. “These findings further elevate the clinical significance of rosacea as growing evidence of its potential link with systemic inflammation is increasingly understood.”

Dr. Thiboutot said that research has implicated both the innate and adaptive immune systems and the neuromuscular system in rosacea’s underpinnings.

“Many of the triggers associated with clinical exacerbation of rosacea are known to activate the immune system and/or the neurovasculature, such as demodex, sunlight, alcohol, and changes in temperature,” she said, adding that therapies targeting the neurovascular effects of rosacea are particularly needed.

More than 50% of patients with rosacea have ocular manifestations, with symptoms such as “dryness, burning and stinging, light sensitivity, blurred vision, and foreign body sensation,” the authors reported.

Diagnosis and management

Without definitive laboratory tests, it’s essential that the clinical diagnosis takes into account not only the physical examination findings, but also patient history, the authors stressed, since “some features may not be visually evident or present at the time of the patient’s visit.”

The authors also recommend taking into account patients’ perception and response to their appearance and its effects on their emotional, social, and professional lives when selecting interventions.

“Rosacea’s unsightly and conspicuous appearance often has significant emotional ramifications, potentially resulting in depression or anxiety, and frequently interferes with social and occupational interactions,” the authors wrote. “It may also be advisable to remind patients that normalization of skin tone and color is the goal rather than complete eradication of facial coloration, which can leave the face with a sallow appearance.”

Therapy will often require multiple agents, such as topical and oral agents for inflammatory papules/pustules of rosacea. If insufficient, adjunctive therapy with oral antibiotics or retinoids may be options, though the latter requires prevention of pregnancy during treatment. The authors also discussed pharmacological treatments for facial erythema and flushing, with all these drugs organized in tables according to symptoms and their levels of evidence and effectiveness.

Despite limited clinical evidence, the authors noted success with two types of laser therapy – pulsed-dye and potassium titanyl phosphate – for telangiectasia and erythema. They also noted the option of intense pulsed light for flushing, ocular symptoms, and meibomian gland dysfunction, and of ablative lasers for rhinophymatous nose. But they highlighted the importance of being cautious when using these therapies on darker skin.

In their discussion of ocular rosacea, the authors described the various manifestations and the two “mainstays” of treatment: “eyelash hygiene and oral [omega-3] supplementation, followed by topical azithromycin or calcineurin inhibitors.” In addition to pharmacological and light therapy options, attention to environmental contributors and conscientious skin care regimens can benefit patients with rosacea as well.

“Clinicians may advise patients to keep a daily diary of lifestyle and environmental factors that appear to affect their rosacea to help identify and avoid their personal triggers,” the authors wrote. “The most common factors are sun exposure, emotional stress, hot weather, wind, heavy exercise, alcohol consumption, hot baths, cold weather, spicy foods, humidity, indoor heat, certain skin-care products, heated beverages, certain medications, medical conditions, certain fruits, marinated meats, certain vegetables, and dairy products.”

The paper also emphasizes the importance of gentle skin care given the highly sensitive and easily irritated skin of patients with rosacea. Sunscreen use, particularly with mineral sunscreens that provide physical barriers and reflect ultraviolet light, should be a key aspect of patients’ skin care, and clinicians should advise patients to seek out gentle, nonirritating cleansers.

Funding was provided by the National Rosacea Society, which receives funding from patients and corporations that include Aclaris Therapeutics, Allergan, Bayer, Cutanea Life Sciences, and Galderma Laboratories. Dr. Thiboutot consults for Galderma. Six of the other nine coauthors have financial links to industry through advisory boards, consulting, or research funding.

SOURCE: Thiboutot D et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-10.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Telepsychiatry: What you need to know

The need for mental health services has never been greater. Unfortunately, many patients have limited access to psychiatric treatment, especially those who live in rural areas. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of psychiatric services through telecommunications technology, usually video conferencing—may help address this problem. Even before the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, telepsychiatry was becoming increasingly common. A survey of US mental health facilities found that the proportion of facilities offering telepsychiatry nearly doubled from 2010 to 2017, from 15.2% to 29.2%.1

In this article, we describe examples of where and how telepsychiatry is being used successfully, and its potential advantages. We discuss concerns about its use, its impact on the therapeutic alliance, and patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of it. We also discuss the legal, technological, and financial aspects of using telepsychiatry. With an increased understanding of these issues, psychiatric clinicians will be better able to integrate telepsychiatry into their practices.

How and where is telepsychiatry being used

In addition to being used to provide psychotherapy, telepsychiatry is being employed for diagnosis and evaluation; clinical consultations; research; supervision, mentoring, and education of trainees; development of treatment programs; and public health. Telepsychiatry is an excellent mechanism to provide high-level second opinions to primary care physicians and psychiatrists on complex cases for both diagnostic purposes and treatment.

Evidence suggests that telepsychiatry can play a beneficial role in a variety of settings, and for a range of patient populations.

Emergency departments (EDs). Using telepsychiatry for psychiatric consultations in EDs could result in a quicker disposition of patients and reduced crowding and wait times. A survey of on-call clinicians in a pediatric ED found that using telepsychiatry for on-site psychiatric consultations decreased patients’ length of stay, improved resident on-call burden, and reduced factors related to physician burnout.2 In this study, telepsychiatry use reduced travel for face-to-face evaluations by 75% and saved more than 2 hours per call day.2

Medical clinics. Using telepsychiatry to deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduced symptoms of depression or anxiety among 203 primary care patients.3 Incorporating telepsychiatry into existing integrated primary care settings is becoming more common. For example, an integrated-care model that includes telepsychiatry is serving the needs of complex patients in a high-volume, urban primary care clinic in Colorado.4

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams. Telepsychiatry is being used by ACT teams for crisis intervention and to reduce inpatient hospitalizations.5

Continue to: Correctional facilities

Correctional facilities. With the downsizing and closure of many state psychiatric hospitals across the United States over the last several decades, jails and prisons have become de facto mental health hospitals. This situation presents many challenges, including access to mental health care and the need to avoid medications with the potential for abuse. Using telepsychiatry for psychiatric consultations in correctional facilities can improve access to mental health care.

Geriatric patients.

Children and adolescents. The Michigan Child Collaborative Care (MC3) program is a telepsychiatry consultation service that has been able to provide cost-effective, timely, remote consultation to primary care clinicians who care for youth and perinatal women.8 New York has a pediatric collaborative care program, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care (CAP PC), that incorporates telepsychiatry consultations for families who live >1 hour away from one of the program’s treatment sites.9

Patients with cancer. A literature review that included 9 studies found no statistically significant differences between standard face-to-face interventions and telepsychiatry for improving quality-of-life scores among patients receiving treatment for cancer.10

Patients with insomnia. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is often recommended as a first-line treatment, but is not available for many patients. A recent study showed that CBT-I provided via telepsychiatry for patients with shift work sleep disorder was as effective as face-to-face therapy.11 Increasing the availability of this treatment could decrease reliance on pharmacotherapy for sleep.

Patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). Treatment for patients with OUD is limited by access to, and availability of, psychiatric clinicians. Telepsychiatry can help bridge this gap. One example of such use is in Ontario, Canada, where more than 10,000 patients with concurrent opiate abuse and other mental health disorders have received care via telepsychiatry since 2008.12

Continue to: Increasing access to cost-effective care where it is needed most

Increasing access to cost-effective care where it is needed most

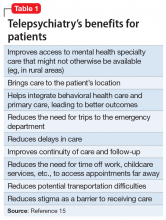

There is a crisis in mental health care in rural areas of the United States. A study assessing delivery of care to US residents who live in rural areas found these patients’ mental health–related quality of life was 2.5 standard deviations below the national mean.13 Additionally, the need for treatment is expected to rise as the number of psychiatrists falls. According to a 2017 National Council for Behavioral Health report,14 by 2025, demand may outstrip supply by 6,090 to 15,600 psychiatrists. While telepsychiatry cannot improve this shortage per se, it can help increase access to psychiatric services. The potential benefits of telepsychiatry for patients are summarized in Table 1.15

Telepsychiatry may be more cost-effective than traditional face-to-face treatment. A cost analysis of an expanding, multistate behavioral telehealth intervention program for rural American Indian/Alaska Native populations found substantial cost savings associated with telepsychiatry.16 In this analysis, the estimated cost efficiencies of telepsychiatry were more evident in rural communities, and having a multistate center was less expensive than each state operating independently.16

Most importantly, evidence suggests that treatment delivered via telepsychiatry is at least as effective as traditional face-to-face care. In a review that included >150 studies, Bashshur et al17 concluded, “Effective approaches to the long-term management of mental illness include monitoring, surveillance, mental health promotion, mental illness prevention, and biopsychosocial treatment programs. The empirical evidence … demonstrates the capability of [telepsychiatry] to perform these functions more efficiently and as well as or more effectively than in-person care

Clinician and patient attitudes toward telepsychiatry

Clinicians have legitimate concerns about the quality of care being delivered when using telepsychiatry. Are patients satisfied with treatment delivered via telepsychiatry? Can a therapeutic alliance be established and maintained? It appears that clinicians may have more concerns than patients do.18

A study of telepsychiatry consultations for patients in rural primary care clinics performed by clinicians at an urban health center found that patients and clinicians were highly satisfied with telepsychiatry.19 Both patients and clinicians believed that telepsychiatry provided patients with better access to care. There was a high degree of agreement between patients and clinician responses.19

Continue to: In a review of...

In a review of 452 telepsychiatry studies, Hubley et al20 focused on satisfaction, reliability, treatment outcomes, implementation outcomes, cost effectiveness, and legal issues. They concluded that patients and clinicians are generally satisfied with telepsychiatry services. Interestingly, clinicians expressed more concerns about the potential adverse effects of telepsychiatry on therapeutic rapport. Hubley et al20 found no published reports of adverse events associated with telepsychiatry use.

In a study of school-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting, Mayworm et al21 found that patients were highly satisfied with both in-person and telepsychiatry services, and there were no significant differences in preference. This study also found that telepsychiatry services were more time-efficient than in-person services.

A study of using telepsychiatry to treat unipolar depression found that patient satisfaction scores improved with increasing number of video-based sessions, and were similar among all age groups.22 An analysis of this study found that total satisfaction scores were higher for patients than for clinicians.23

In a study of satisfaction with telepsychiatry among community-dwelling older veterans, 90% of participants reported liking or even preferring telepsychiatry, even though the experience was novel for most of them.24

As always, patients’ preferences need to be kept in mind when considering what services can and should be provided via telepsychiatry, because not all patients will find it acceptable. For example, in a study of veterans’ attitudes toward treatment via telepsychiatry, Goetter et al25 found that interest was mixed. Twenty-six percent of patients were “not at all comfortable,” while 13% were “extremely comfortable” using telepsychiatry from home. Notably, 33% indicated a clear preference for telepsychiatry compared to in-person mental health visits.

Continue to: Legal aspects of telepsychiatry

Legal aspects of telepsychiatry

Box 1

As part of the efforts to contain the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the use of telemedicine, including telepsychiatry, has increased substantially. Here are a few key facts to keep in mind while practicing telepsychiatry during this pandemic:

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services relaxed requirements for telehealth starting March 6, 2020 and for the duration of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency. Under this new waiver, Medicare can pay for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telehealth across the country and including in patient’s places of residence. For details, see www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. This fact sheet reviews relevant information, including billing codes.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act requirements, specifically those for secure communications, will not be enforced when telehealth is used under the new waiver. Because of this, popular but unsecure software applications, such as Apple’s FaceTime, Microsoft’s Teams, or Facebook’s Messenger, WhatsApp, and Messenger Rooms, can be used.

- Informed consent for the use of telepsychiatry in this situation should be obtained from the patient or his/her guardian, and documented in the patient’s medical record. For example: “Informed consent received for providing services via video teleconferencing to the home in order to protect the patient from COVID-19 exposure. Confidentiality issues were discussed.”

Licensure. State licensing and medical regulatory organizations consider the care provided via telepsychiatry to be rendered where the patient is physically located when services are rendered. Because of this, psychiatrists who use telepsychiatry generally need to hold a license in the state where their patients are located, regardless of where the psychiatrist is located.

Some states offer special telemedicine licenses. Typically, these licenses allow clinicians to practice across state lines without having to obtain a full professional license from the state. Be sure to check with the relevant state medical board where you intend to practice.

Because state laws related to telepsychiatry are continuously evolving, we suggest that clinicians continually check these laws and obtain a regulatory response in writing so there is ongoing documentation. For more information on this topic, see “Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: Understanding the rules” at MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Malpractice insurance. Some insurance companies offer coverage that includes the practice of telepsychiatry, whereas other carriers require the purchase of additional coverage for telepsychiatry. There may be additional requirements for practicing across state lines. Be sure to check with your insurer.

Continue to: Technical requirements and costs

Technical requirements and costs