User login

Penile Paraffinoma: Dramatic Recurrence After Surgical Resection

To the Editor:

The term paraffinoma refers to a chronic granulomatous response to injection of paraffin, silicone, or other mineral oils into skin and soft tissue. Paraffinomas develop when the material is injected into the skin for cosmetic purposes to augment or enhance one’s appearance. Although they may occur in any location, the most common sites include the breasts and buttocks. The penis is a rare but emerging site for paraffinomas.1-3 We present a rare case of recurrence of a penile paraffinoma following surgical resection.

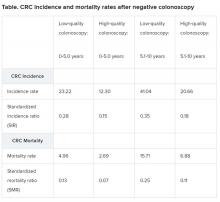

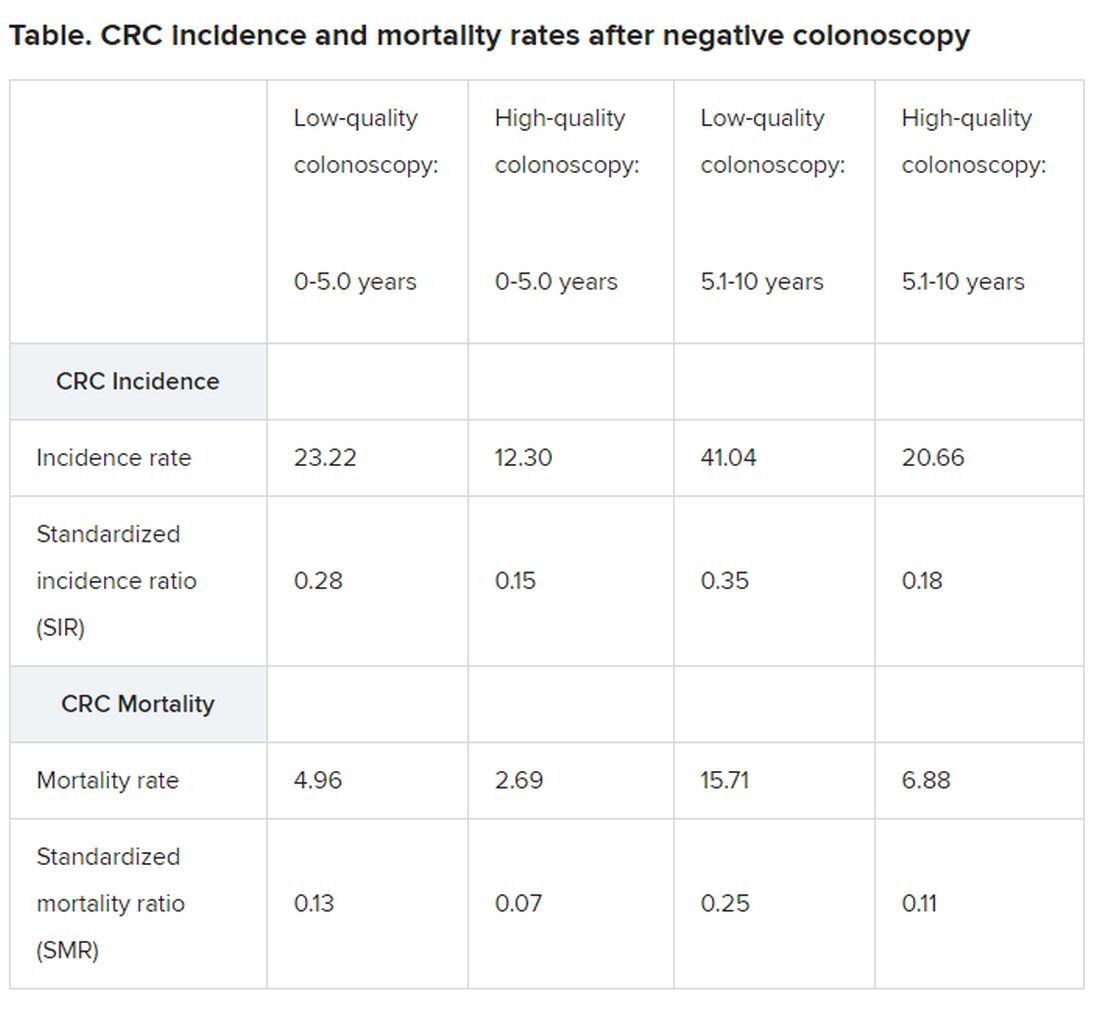

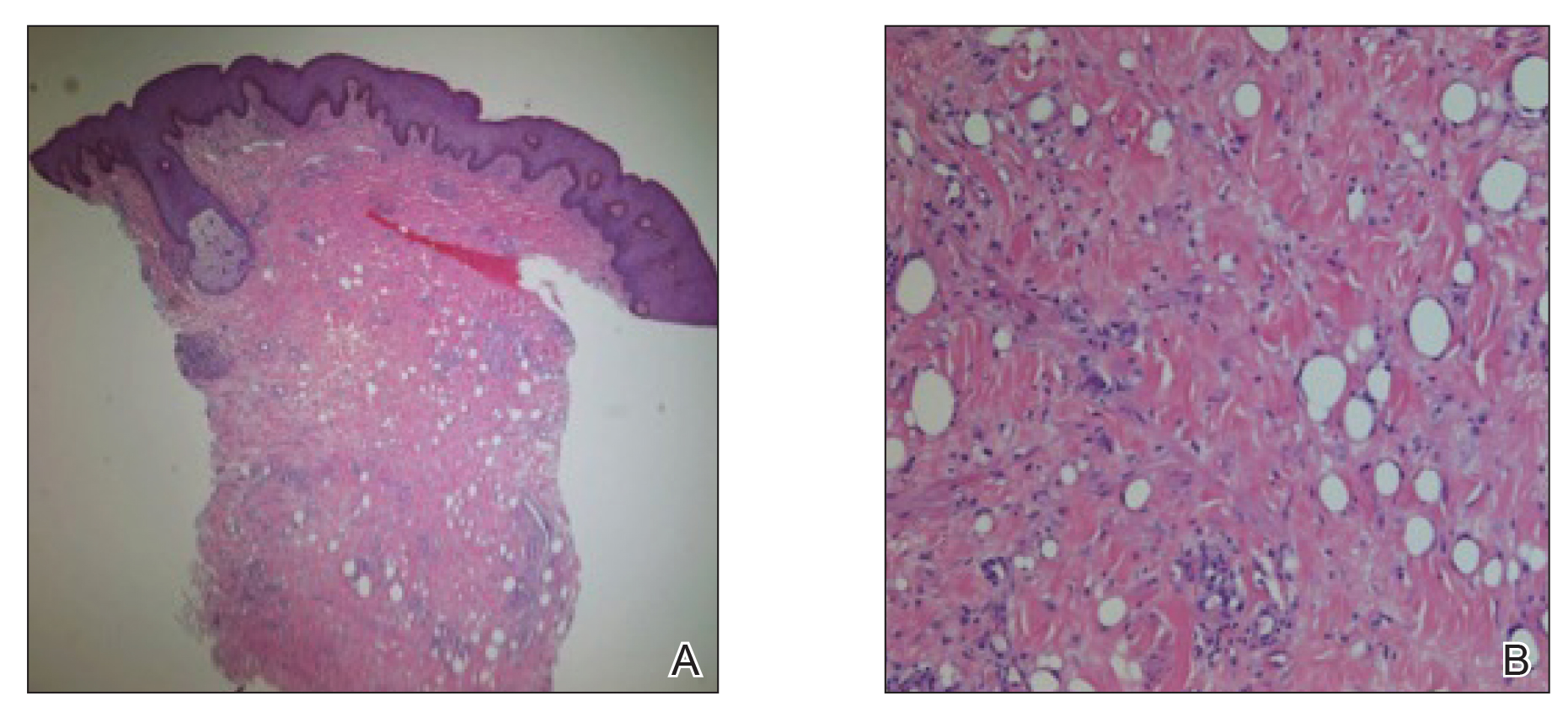

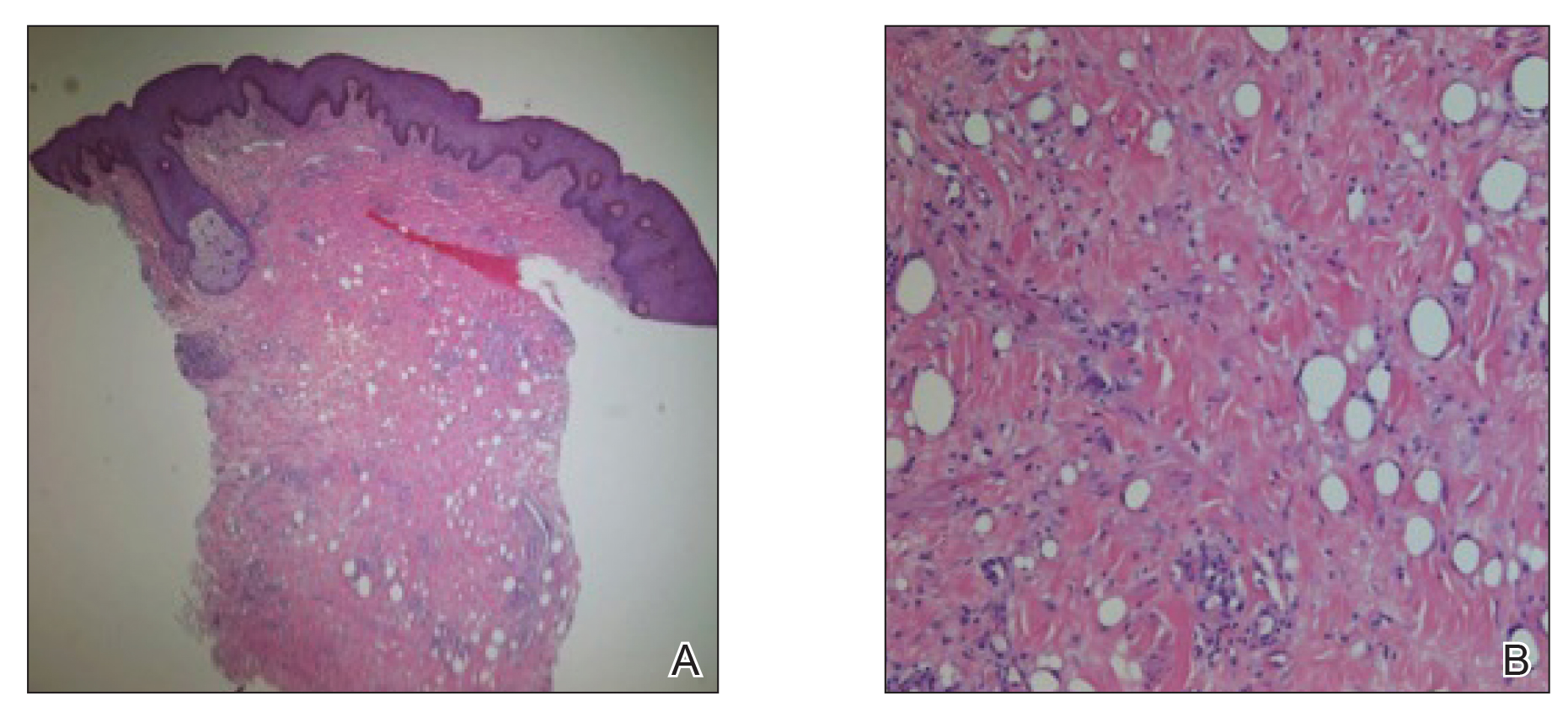

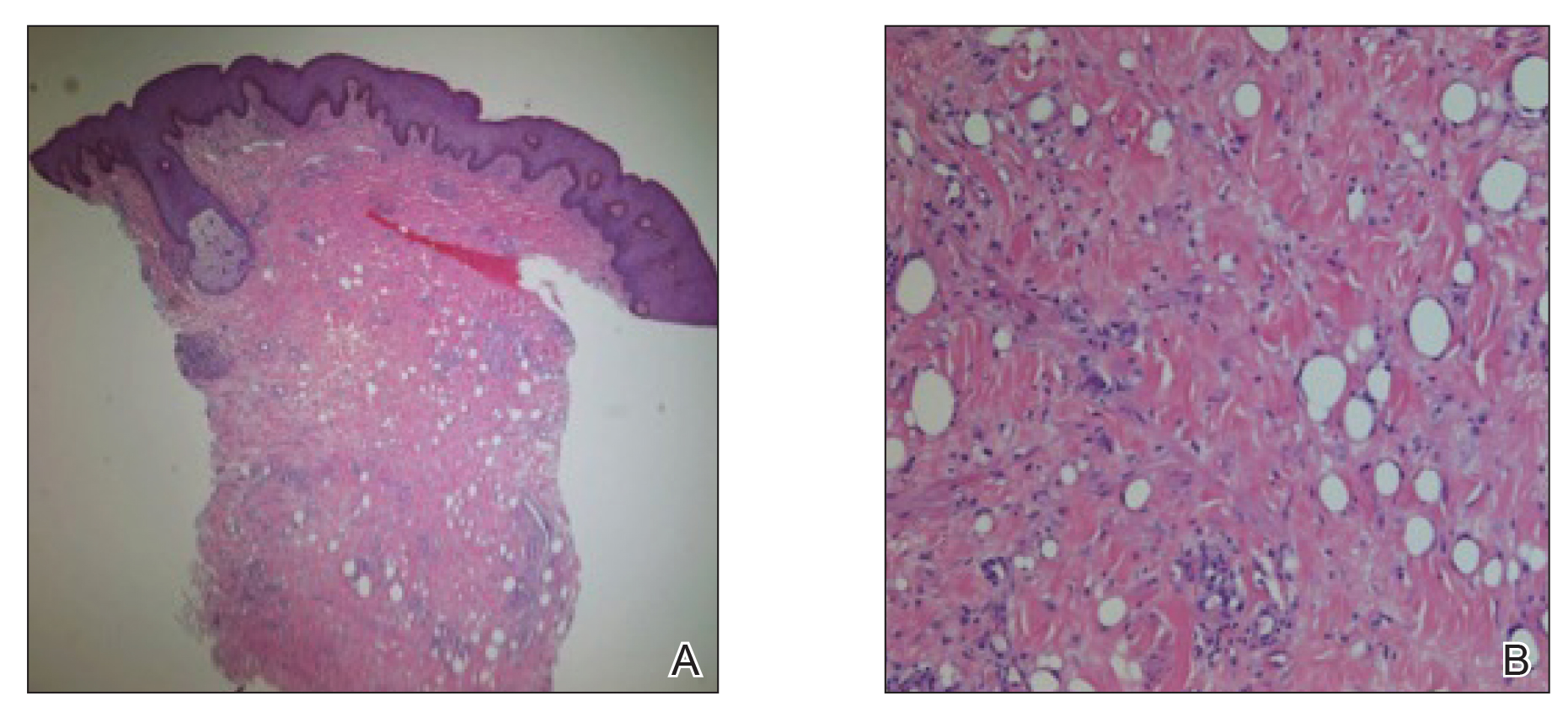

A 26-year-old uncircumcised Trinidadian man presented with a 5-cm, exquisitely tender tumor involving the penile shaft and median raphe that rapidly evolved over the course of 3 weeks (Figure 1). He presented with inability to urinate, attain an erection, or ambulate without notable tenderness. Additionally, he developed swelling of the penis and surrounding tissue. He had no other medical comorbidities; however, 1 year prior he presented to a urologist with a 1-cm nodule involving the median raphe that was surgically resected and required circumcision. Biopsy at the time of his surgical procedure revealed an exuberant foreign body giant cell reaction with surrounding empty spaces in the dermis resembling Swiss cheese, consistent with a paraffinoma (Figure 2). The recurrent tumor, which was 5 times the size of the initial nodule, was biopsied. Again, histopathologic findings were consistent with a paraffinoma with extensive dermal fibrosis and absence of polarizable material.

The patient underwent extensive reconstructive surgery requiring skin grafting to the penile shaft. Given the size and location of this recurrent tumor with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, consideration for prevention of recurrent episodes included novel therapeutic treatment options to suppress inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.

Paraffin injections are used for cosmetic enhancement and most often occur in a nonclinical setting without medical supervision, as they are not US Food and Drug Administration–approved medical injectable materials. Examples of oils injected include paraffin, camphorated oil, cottonseed or sesame oil, mineral oil, petroleum jelly, and beeswax. These oils are not hydrolyzed by tissue lipases but are instead treated as a foreign body substance with subsequent granuloma formation (also known as sclerosing lipogranuloma), which can occur many years after injection.4 The granulomatous response may be observed months to years after injection. The paraffinoma normally affects the injection site; however, regional lymphadenopathy and systemic disease has been reported.2 Histopathologic findings are characteristic and consist of a foreign body giant cell reaction, variably sized round to oval cavities within the dermis, and varying degrees of dermal fibrosis.5

In 1899, mineral oil was first injected into male genitalia to restore architecture in a patient’s testicles following bilateral orchiectomy. After the success of this endeavor, mineral oil injections were used as filler for other defects.3 However, by 1906 the complications of these injections became public knowledge when 2 patients developed subcutaneous nodules after receiving injections for facial wrinkles.2 Despite public knowledge of these complications, penile paraffin injections continued to occur both in medical and eventually nonmedical settings.

In 1947, Quérnu and Pérol6 described 6 penile paraffinoma cases outside the United States. Patients had petroleum jelly injections that eventuated in penile paraffinomas, and all of them lost the ability to attain an erection.6 Four years later, Bradley and Ehrgott7 described a case of penile paraffinoma likely caused by application of paraffin in association with occupational exposure. In 1956, May and Pickering8 cited a case of penile paraffinoma affecting the entire penile shaft in which the patient had undergone paraffin injection 7 years prior to treat premature ejaculation. Unfortunately, the injection resulted in a painful and unsatisfactory erection without resolution of premature ejaculation.8 Lee et al9 analyzed 26 cases of penile paraffinomas that occurred from 1981 to 1993. They found that all patients underwent injections of paraffin or petroleum jelly performed by nonmedical personnel with the predominant goal of enhancing penis size. Within 18.5 months of injection, 19 patients already experienced tenderness at the injection site. The remaining 7 patients experienced penile skin discoloration and abnormal contouring of the penis. Biopsy specimens revealed hyaline necrosis of subcutaneous adipose septa, cystlike spaces throughout involved tissue, and macrophages engulfing adipose tissue were found near blood vessels.9 In 2007, Eandi et al4 reported a case of penile paraffinoma with a 40-year delay of onset. Four years later, Manny et al10 reported penile paraffinomas in 3 Laotian men who injected a mineral oil.

Currently, paraffin injections are uncommon but still are being performed in some countries in Eastern Europe and the Far East11; they rarely are reported in the United States. Injections can occur in unusual sites such as the knee, and paraffinomas can develop many years after the procedure.12 Additionally, paraffinomas can obscure proper diagnosis of carcinomas, as described by Lee et al13 in a case in which a cervical paraffin injection confounded the diagnosis of a thyroid tumor. Furthermore, these injections usually are performed by nonmedical personnel and typically are repeated multiple times to reach cosmetic goals, rendering the patient vulnerable to early complications including allergic reactions, paraphimosis, infection, and inflammation.3

The clinical presentation of a penile paraffinoma may be a mimicker of several different entities, which are important to consider in the evaluation of a presenting patient. Infectious etiologies must be considered including lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, atypical mycobacteria, lupus vulgaris, and sexually transmitted infections. Importantly, neoplasms must be ruled out including squamous cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, melanoma, adenocarcinoma, or metastasis. Lymphedema, prior surgical procedures, trauma, and inflammatory etiologies also are in the differential diagnosis.14 Nonetheless, physicians must have a high clinical suspicion in the evaluation of a possible paraffinoma, as patients may not be forthcoming with relevant clinical history regarding a prior injection to the affected site, particularly if the injection occurred many years ago. As such, the patient may not consider this history relevant or may not even remember the event occurred, as was observed in our case. Furthermore, embarrassment, social taboo, and stigma may be associated with the behavior of undergoing injections in nonclinical settings without medical supervision.15

Patients may be motivated to undergo dangerous procedures to potentially alter their appearance due to perceived enhanced sexual ability, influence by loved ones, cultural rituals, and societal pressure.15,16 Furthermore, patients may not be aware of the material being injected or the volume. Given that these injections often are used with the goal of cosmetic enhancement, biopsies in cosmetically sensitive areas must be given careful consideration, and a thorough clinical history must support the decision to pursue a biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

The definitive diagnosis of a paraffinoma is determined by histopathology. However, the use of imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have been employed to delineate the extent of involvement. Imaging studies allow for surgical planning and may assist in narrowing a differential diagnosis.17 Currently, wide and complete surgical resection is the only definitive treatment of paraffinomas, including penile paraffinomas, as there is no evidence of spontaneous regression.3 A report of a reconstructive surgery involving penile resurfacing without T-style anastomosis has been found effective at preventing necrosis of the ventral penile skin. Not all paraffinomas behave similarly, and there is no reliable method to determine which paraffinoma may possess a more aggressive clinical course compared to those which have a more indolent course.18 As such, early detection is critical in the management of paraffinomas, especially in anatomic locations where tissue preservation is of utmost importance. In the case of a large penile paraffinoma with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, physicians must consider prevention of recurrent episodes through suppression of inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.19 Other medical treatments reported with varying success include corticosteroids, imiquimod, and isotretinoin.19-24 Employing adjunctive medical treatment may decrease the size of the mass, reducing the surgical defect size and preserving tissue vitality. Ultimately, the most crucial aspect in treatment is prevention, as injection of foreign materials elicits a foreign body response and can lead to notable morbidity.

- De Siati M, Selvaggio O, Di Fino G, et al. An unusual delayed complication of paraffin self-injection for penile girth augmentation. BMC Urol. 2013;13:66.

- Sejben I, Rácz A, Svébis M, et al. Petroleum jelly-induced penile paraffinoma with inguinal lymphadenitis mimicking incarcerated inguinal hernia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:E137-E139.

- Bayraktar N, Basar I. Penile paraffinoma [published online September 17, 2012]. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:202840.

- Eandi JA, Yao AP, Javidan J. Penile paraffinoma: the delayed presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;29:553-555.

- HirshBCJohnsonWC. Pathology of granulomatous diseases. foreign body granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:531-538.

- Quérnu J, Pérol E. Paraffinomas of the penis. J Chir Par. 1947;63:345.

- Bradley, RH, Ehrgott WA. Paraffinoma of the penis: case report. J Urol. 1951;65:453.

- May JA, Pickering PP. Paraffinoma of the penis. Calif Med. 1956;85:42-44.

Yonsei Med J. 1994;35:344-348. - Lee T, Choi HR, Lee YT, et al. Paraffinoma of the penis.

- Manny T, Pettus J, Hemal A, et al. Penile sclerosing lipogranulomas and disfigurement from use of “1Super Extenze” among Laotian immigrants. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3505-3510.

- Akkus E Paraffinoma and ulcer of the external genitalia after self-injection of vaseline. J Sex Med. 2006;3:170-172.

- Grassetti L, Lazzeri D, Torresetti M, et al. Paraffinoma of the knee 60 years after primary infection. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:789-790.

- Lee YS, Son EJ, Kim BW, et al. Difficult evaluation of thyroid cancer due to cervical paraffin injection. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81(suppl 1):S17-S20.

- Gómez-Armayones S, Penín R, Marcoval J. Penile paraffinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:957-959.

- Moon DG, Yoo JW, Bae JH, et al. Sexual function and psychological characteristics of penile paraffinoma. Asian J Androl. 2003;5:191-194.

- Pehlivanov G, Kavaklieva S, Kazandjieva J, et al. Foreign-body granuloma of the penis in sexually active individuals (penile paraffinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:845-851.

- Cormio L, Di Fino G, Scavone C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of penile paraffinoma: case report. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:39.

- Shin YS, Zhao C, Park JK. New reconstructive surgery for penile paraffinoma to prevent necrosis of ventral penile skin. Urology. 2013;81:437-441.

- Feldmann R, Harms M, Chavaz P, et al. Orbital and palpebral paraffinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:833-835.

- MastruserioDNPesqueiraMJCobbMW. Severe granulomatous reaction and facial ulceration occurring after subcutaneous silicone injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:849-852.

- HoWS Management of paraffinoma of the breast. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:232-234.

- LloretPSuccessful treatment of granulomatous reactions secondary to injection of esthetic implants. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:486-490.

- RosenbergEThree cases of penile paraffinoma. Urology. 2007;70:372.

- Baumann LS, Halem ML. Lip silicone granulomatous foreign body reaction treated with Aldara (imiquimod 5%). Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:429-432.

To the Editor:

The term paraffinoma refers to a chronic granulomatous response to injection of paraffin, silicone, or other mineral oils into skin and soft tissue. Paraffinomas develop when the material is injected into the skin for cosmetic purposes to augment or enhance one’s appearance. Although they may occur in any location, the most common sites include the breasts and buttocks. The penis is a rare but emerging site for paraffinomas.1-3 We present a rare case of recurrence of a penile paraffinoma following surgical resection.

A 26-year-old uncircumcised Trinidadian man presented with a 5-cm, exquisitely tender tumor involving the penile shaft and median raphe that rapidly evolved over the course of 3 weeks (Figure 1). He presented with inability to urinate, attain an erection, or ambulate without notable tenderness. Additionally, he developed swelling of the penis and surrounding tissue. He had no other medical comorbidities; however, 1 year prior he presented to a urologist with a 1-cm nodule involving the median raphe that was surgically resected and required circumcision. Biopsy at the time of his surgical procedure revealed an exuberant foreign body giant cell reaction with surrounding empty spaces in the dermis resembling Swiss cheese, consistent with a paraffinoma (Figure 2). The recurrent tumor, which was 5 times the size of the initial nodule, was biopsied. Again, histopathologic findings were consistent with a paraffinoma with extensive dermal fibrosis and absence of polarizable material.

The patient underwent extensive reconstructive surgery requiring skin grafting to the penile shaft. Given the size and location of this recurrent tumor with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, consideration for prevention of recurrent episodes included novel therapeutic treatment options to suppress inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.

Paraffin injections are used for cosmetic enhancement and most often occur in a nonclinical setting without medical supervision, as they are not US Food and Drug Administration–approved medical injectable materials. Examples of oils injected include paraffin, camphorated oil, cottonseed or sesame oil, mineral oil, petroleum jelly, and beeswax. These oils are not hydrolyzed by tissue lipases but are instead treated as a foreign body substance with subsequent granuloma formation (also known as sclerosing lipogranuloma), which can occur many years after injection.4 The granulomatous response may be observed months to years after injection. The paraffinoma normally affects the injection site; however, regional lymphadenopathy and systemic disease has been reported.2 Histopathologic findings are characteristic and consist of a foreign body giant cell reaction, variably sized round to oval cavities within the dermis, and varying degrees of dermal fibrosis.5

In 1899, mineral oil was first injected into male genitalia to restore architecture in a patient’s testicles following bilateral orchiectomy. After the success of this endeavor, mineral oil injections were used as filler for other defects.3 However, by 1906 the complications of these injections became public knowledge when 2 patients developed subcutaneous nodules after receiving injections for facial wrinkles.2 Despite public knowledge of these complications, penile paraffin injections continued to occur both in medical and eventually nonmedical settings.

In 1947, Quérnu and Pérol6 described 6 penile paraffinoma cases outside the United States. Patients had petroleum jelly injections that eventuated in penile paraffinomas, and all of them lost the ability to attain an erection.6 Four years later, Bradley and Ehrgott7 described a case of penile paraffinoma likely caused by application of paraffin in association with occupational exposure. In 1956, May and Pickering8 cited a case of penile paraffinoma affecting the entire penile shaft in which the patient had undergone paraffin injection 7 years prior to treat premature ejaculation. Unfortunately, the injection resulted in a painful and unsatisfactory erection without resolution of premature ejaculation.8 Lee et al9 analyzed 26 cases of penile paraffinomas that occurred from 1981 to 1993. They found that all patients underwent injections of paraffin or petroleum jelly performed by nonmedical personnel with the predominant goal of enhancing penis size. Within 18.5 months of injection, 19 patients already experienced tenderness at the injection site. The remaining 7 patients experienced penile skin discoloration and abnormal contouring of the penis. Biopsy specimens revealed hyaline necrosis of subcutaneous adipose septa, cystlike spaces throughout involved tissue, and macrophages engulfing adipose tissue were found near blood vessels.9 In 2007, Eandi et al4 reported a case of penile paraffinoma with a 40-year delay of onset. Four years later, Manny et al10 reported penile paraffinomas in 3 Laotian men who injected a mineral oil.

Currently, paraffin injections are uncommon but still are being performed in some countries in Eastern Europe and the Far East11; they rarely are reported in the United States. Injections can occur in unusual sites such as the knee, and paraffinomas can develop many years after the procedure.12 Additionally, paraffinomas can obscure proper diagnosis of carcinomas, as described by Lee et al13 in a case in which a cervical paraffin injection confounded the diagnosis of a thyroid tumor. Furthermore, these injections usually are performed by nonmedical personnel and typically are repeated multiple times to reach cosmetic goals, rendering the patient vulnerable to early complications including allergic reactions, paraphimosis, infection, and inflammation.3

The clinical presentation of a penile paraffinoma may be a mimicker of several different entities, which are important to consider in the evaluation of a presenting patient. Infectious etiologies must be considered including lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, atypical mycobacteria, lupus vulgaris, and sexually transmitted infections. Importantly, neoplasms must be ruled out including squamous cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, melanoma, adenocarcinoma, or metastasis. Lymphedema, prior surgical procedures, trauma, and inflammatory etiologies also are in the differential diagnosis.14 Nonetheless, physicians must have a high clinical suspicion in the evaluation of a possible paraffinoma, as patients may not be forthcoming with relevant clinical history regarding a prior injection to the affected site, particularly if the injection occurred many years ago. As such, the patient may not consider this history relevant or may not even remember the event occurred, as was observed in our case. Furthermore, embarrassment, social taboo, and stigma may be associated with the behavior of undergoing injections in nonclinical settings without medical supervision.15

Patients may be motivated to undergo dangerous procedures to potentially alter their appearance due to perceived enhanced sexual ability, influence by loved ones, cultural rituals, and societal pressure.15,16 Furthermore, patients may not be aware of the material being injected or the volume. Given that these injections often are used with the goal of cosmetic enhancement, biopsies in cosmetically sensitive areas must be given careful consideration, and a thorough clinical history must support the decision to pursue a biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

The definitive diagnosis of a paraffinoma is determined by histopathology. However, the use of imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have been employed to delineate the extent of involvement. Imaging studies allow for surgical planning and may assist in narrowing a differential diagnosis.17 Currently, wide and complete surgical resection is the only definitive treatment of paraffinomas, including penile paraffinomas, as there is no evidence of spontaneous regression.3 A report of a reconstructive surgery involving penile resurfacing without T-style anastomosis has been found effective at preventing necrosis of the ventral penile skin. Not all paraffinomas behave similarly, and there is no reliable method to determine which paraffinoma may possess a more aggressive clinical course compared to those which have a more indolent course.18 As such, early detection is critical in the management of paraffinomas, especially in anatomic locations where tissue preservation is of utmost importance. In the case of a large penile paraffinoma with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, physicians must consider prevention of recurrent episodes through suppression of inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.19 Other medical treatments reported with varying success include corticosteroids, imiquimod, and isotretinoin.19-24 Employing adjunctive medical treatment may decrease the size of the mass, reducing the surgical defect size and preserving tissue vitality. Ultimately, the most crucial aspect in treatment is prevention, as injection of foreign materials elicits a foreign body response and can lead to notable morbidity.

To the Editor:

The term paraffinoma refers to a chronic granulomatous response to injection of paraffin, silicone, or other mineral oils into skin and soft tissue. Paraffinomas develop when the material is injected into the skin for cosmetic purposes to augment or enhance one’s appearance. Although they may occur in any location, the most common sites include the breasts and buttocks. The penis is a rare but emerging site for paraffinomas.1-3 We present a rare case of recurrence of a penile paraffinoma following surgical resection.

A 26-year-old uncircumcised Trinidadian man presented with a 5-cm, exquisitely tender tumor involving the penile shaft and median raphe that rapidly evolved over the course of 3 weeks (Figure 1). He presented with inability to urinate, attain an erection, or ambulate without notable tenderness. Additionally, he developed swelling of the penis and surrounding tissue. He had no other medical comorbidities; however, 1 year prior he presented to a urologist with a 1-cm nodule involving the median raphe that was surgically resected and required circumcision. Biopsy at the time of his surgical procedure revealed an exuberant foreign body giant cell reaction with surrounding empty spaces in the dermis resembling Swiss cheese, consistent with a paraffinoma (Figure 2). The recurrent tumor, which was 5 times the size of the initial nodule, was biopsied. Again, histopathologic findings were consistent with a paraffinoma with extensive dermal fibrosis and absence of polarizable material.

The patient underwent extensive reconstructive surgery requiring skin grafting to the penile shaft. Given the size and location of this recurrent tumor with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, consideration for prevention of recurrent episodes included novel therapeutic treatment options to suppress inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.

Paraffin injections are used for cosmetic enhancement and most often occur in a nonclinical setting without medical supervision, as they are not US Food and Drug Administration–approved medical injectable materials. Examples of oils injected include paraffin, camphorated oil, cottonseed or sesame oil, mineral oil, petroleum jelly, and beeswax. These oils are not hydrolyzed by tissue lipases but are instead treated as a foreign body substance with subsequent granuloma formation (also known as sclerosing lipogranuloma), which can occur many years after injection.4 The granulomatous response may be observed months to years after injection. The paraffinoma normally affects the injection site; however, regional lymphadenopathy and systemic disease has been reported.2 Histopathologic findings are characteristic and consist of a foreign body giant cell reaction, variably sized round to oval cavities within the dermis, and varying degrees of dermal fibrosis.5

In 1899, mineral oil was first injected into male genitalia to restore architecture in a patient’s testicles following bilateral orchiectomy. After the success of this endeavor, mineral oil injections were used as filler for other defects.3 However, by 1906 the complications of these injections became public knowledge when 2 patients developed subcutaneous nodules after receiving injections for facial wrinkles.2 Despite public knowledge of these complications, penile paraffin injections continued to occur both in medical and eventually nonmedical settings.

In 1947, Quérnu and Pérol6 described 6 penile paraffinoma cases outside the United States. Patients had petroleum jelly injections that eventuated in penile paraffinomas, and all of them lost the ability to attain an erection.6 Four years later, Bradley and Ehrgott7 described a case of penile paraffinoma likely caused by application of paraffin in association with occupational exposure. In 1956, May and Pickering8 cited a case of penile paraffinoma affecting the entire penile shaft in which the patient had undergone paraffin injection 7 years prior to treat premature ejaculation. Unfortunately, the injection resulted in a painful and unsatisfactory erection without resolution of premature ejaculation.8 Lee et al9 analyzed 26 cases of penile paraffinomas that occurred from 1981 to 1993. They found that all patients underwent injections of paraffin or petroleum jelly performed by nonmedical personnel with the predominant goal of enhancing penis size. Within 18.5 months of injection, 19 patients already experienced tenderness at the injection site. The remaining 7 patients experienced penile skin discoloration and abnormal contouring of the penis. Biopsy specimens revealed hyaline necrosis of subcutaneous adipose septa, cystlike spaces throughout involved tissue, and macrophages engulfing adipose tissue were found near blood vessels.9 In 2007, Eandi et al4 reported a case of penile paraffinoma with a 40-year delay of onset. Four years later, Manny et al10 reported penile paraffinomas in 3 Laotian men who injected a mineral oil.

Currently, paraffin injections are uncommon but still are being performed in some countries in Eastern Europe and the Far East11; they rarely are reported in the United States. Injections can occur in unusual sites such as the knee, and paraffinomas can develop many years after the procedure.12 Additionally, paraffinomas can obscure proper diagnosis of carcinomas, as described by Lee et al13 in a case in which a cervical paraffin injection confounded the diagnosis of a thyroid tumor. Furthermore, these injections usually are performed by nonmedical personnel and typically are repeated multiple times to reach cosmetic goals, rendering the patient vulnerable to early complications including allergic reactions, paraphimosis, infection, and inflammation.3

The clinical presentation of a penile paraffinoma may be a mimicker of several different entities, which are important to consider in the evaluation of a presenting patient. Infectious etiologies must be considered including lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, atypical mycobacteria, lupus vulgaris, and sexually transmitted infections. Importantly, neoplasms must be ruled out including squamous cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, melanoma, adenocarcinoma, or metastasis. Lymphedema, prior surgical procedures, trauma, and inflammatory etiologies also are in the differential diagnosis.14 Nonetheless, physicians must have a high clinical suspicion in the evaluation of a possible paraffinoma, as patients may not be forthcoming with relevant clinical history regarding a prior injection to the affected site, particularly if the injection occurred many years ago. As such, the patient may not consider this history relevant or may not even remember the event occurred, as was observed in our case. Furthermore, embarrassment, social taboo, and stigma may be associated with the behavior of undergoing injections in nonclinical settings without medical supervision.15

Patients may be motivated to undergo dangerous procedures to potentially alter their appearance due to perceived enhanced sexual ability, influence by loved ones, cultural rituals, and societal pressure.15,16 Furthermore, patients may not be aware of the material being injected or the volume. Given that these injections often are used with the goal of cosmetic enhancement, biopsies in cosmetically sensitive areas must be given careful consideration, and a thorough clinical history must support the decision to pursue a biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

The definitive diagnosis of a paraffinoma is determined by histopathology. However, the use of imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have been employed to delineate the extent of involvement. Imaging studies allow for surgical planning and may assist in narrowing a differential diagnosis.17 Currently, wide and complete surgical resection is the only definitive treatment of paraffinomas, including penile paraffinomas, as there is no evidence of spontaneous regression.3 A report of a reconstructive surgery involving penile resurfacing without T-style anastomosis has been found effective at preventing necrosis of the ventral penile skin. Not all paraffinomas behave similarly, and there is no reliable method to determine which paraffinoma may possess a more aggressive clinical course compared to those which have a more indolent course.18 As such, early detection is critical in the management of paraffinomas, especially in anatomic locations where tissue preservation is of utmost importance. In the case of a large penile paraffinoma with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, physicians must consider prevention of recurrent episodes through suppression of inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.19 Other medical treatments reported with varying success include corticosteroids, imiquimod, and isotretinoin.19-24 Employing adjunctive medical treatment may decrease the size of the mass, reducing the surgical defect size and preserving tissue vitality. Ultimately, the most crucial aspect in treatment is prevention, as injection of foreign materials elicits a foreign body response and can lead to notable morbidity.

- De Siati M, Selvaggio O, Di Fino G, et al. An unusual delayed complication of paraffin self-injection for penile girth augmentation. BMC Urol. 2013;13:66.

- Sejben I, Rácz A, Svébis M, et al. Petroleum jelly-induced penile paraffinoma with inguinal lymphadenitis mimicking incarcerated inguinal hernia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:E137-E139.

- Bayraktar N, Basar I. Penile paraffinoma [published online September 17, 2012]. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:202840.

- Eandi JA, Yao AP, Javidan J. Penile paraffinoma: the delayed presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;29:553-555.

- HirshBCJohnsonWC. Pathology of granulomatous diseases. foreign body granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:531-538.

- Quérnu J, Pérol E. Paraffinomas of the penis. J Chir Par. 1947;63:345.

- Bradley, RH, Ehrgott WA. Paraffinoma of the penis: case report. J Urol. 1951;65:453.

- May JA, Pickering PP. Paraffinoma of the penis. Calif Med. 1956;85:42-44.

Yonsei Med J. 1994;35:344-348. - Lee T, Choi HR, Lee YT, et al. Paraffinoma of the penis.

- Manny T, Pettus J, Hemal A, et al. Penile sclerosing lipogranulomas and disfigurement from use of “1Super Extenze” among Laotian immigrants. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3505-3510.

- Akkus E Paraffinoma and ulcer of the external genitalia after self-injection of vaseline. J Sex Med. 2006;3:170-172.

- Grassetti L, Lazzeri D, Torresetti M, et al. Paraffinoma of the knee 60 years after primary infection. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:789-790.

- Lee YS, Son EJ, Kim BW, et al. Difficult evaluation of thyroid cancer due to cervical paraffin injection. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81(suppl 1):S17-S20.

- Gómez-Armayones S, Penín R, Marcoval J. Penile paraffinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:957-959.

- Moon DG, Yoo JW, Bae JH, et al. Sexual function and psychological characteristics of penile paraffinoma. Asian J Androl. 2003;5:191-194.

- Pehlivanov G, Kavaklieva S, Kazandjieva J, et al. Foreign-body granuloma of the penis in sexually active individuals (penile paraffinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:845-851.

- Cormio L, Di Fino G, Scavone C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of penile paraffinoma: case report. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:39.

- Shin YS, Zhao C, Park JK. New reconstructive surgery for penile paraffinoma to prevent necrosis of ventral penile skin. Urology. 2013;81:437-441.

- Feldmann R, Harms M, Chavaz P, et al. Orbital and palpebral paraffinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:833-835.

- MastruserioDNPesqueiraMJCobbMW. Severe granulomatous reaction and facial ulceration occurring after subcutaneous silicone injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:849-852.

- HoWS Management of paraffinoma of the breast. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:232-234.

- LloretPSuccessful treatment of granulomatous reactions secondary to injection of esthetic implants. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:486-490.

- RosenbergEThree cases of penile paraffinoma. Urology. 2007;70:372.

- Baumann LS, Halem ML. Lip silicone granulomatous foreign body reaction treated with Aldara (imiquimod 5%). Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:429-432.

- De Siati M, Selvaggio O, Di Fino G, et al. An unusual delayed complication of paraffin self-injection for penile girth augmentation. BMC Urol. 2013;13:66.

- Sejben I, Rácz A, Svébis M, et al. Petroleum jelly-induced penile paraffinoma with inguinal lymphadenitis mimicking incarcerated inguinal hernia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:E137-E139.

- Bayraktar N, Basar I. Penile paraffinoma [published online September 17, 2012]. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:202840.

- Eandi JA, Yao AP, Javidan J. Penile paraffinoma: the delayed presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;29:553-555.

- HirshBCJohnsonWC. Pathology of granulomatous diseases. foreign body granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:531-538.

- Quérnu J, Pérol E. Paraffinomas of the penis. J Chir Par. 1947;63:345.

- Bradley, RH, Ehrgott WA. Paraffinoma of the penis: case report. J Urol. 1951;65:453.

- May JA, Pickering PP. Paraffinoma of the penis. Calif Med. 1956;85:42-44.

Yonsei Med J. 1994;35:344-348. - Lee T, Choi HR, Lee YT, et al. Paraffinoma of the penis.

- Manny T, Pettus J, Hemal A, et al. Penile sclerosing lipogranulomas and disfigurement from use of “1Super Extenze” among Laotian immigrants. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3505-3510.

- Akkus E Paraffinoma and ulcer of the external genitalia after self-injection of vaseline. J Sex Med. 2006;3:170-172.

- Grassetti L, Lazzeri D, Torresetti M, et al. Paraffinoma of the knee 60 years after primary infection. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:789-790.

- Lee YS, Son EJ, Kim BW, et al. Difficult evaluation of thyroid cancer due to cervical paraffin injection. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81(suppl 1):S17-S20.

- Gómez-Armayones S, Penín R, Marcoval J. Penile paraffinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:957-959.

- Moon DG, Yoo JW, Bae JH, et al. Sexual function and psychological characteristics of penile paraffinoma. Asian J Androl. 2003;5:191-194.

- Pehlivanov G, Kavaklieva S, Kazandjieva J, et al. Foreign-body granuloma of the penis in sexually active individuals (penile paraffinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:845-851.

- Cormio L, Di Fino G, Scavone C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of penile paraffinoma: case report. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:39.

- Shin YS, Zhao C, Park JK. New reconstructive surgery for penile paraffinoma to prevent necrosis of ventral penile skin. Urology. 2013;81:437-441.

- Feldmann R, Harms M, Chavaz P, et al. Orbital and palpebral paraffinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:833-835.

- MastruserioDNPesqueiraMJCobbMW. Severe granulomatous reaction and facial ulceration occurring after subcutaneous silicone injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:849-852.

- HoWS Management of paraffinoma of the breast. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:232-234.

- LloretPSuccessful treatment of granulomatous reactions secondary to injection of esthetic implants. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:486-490.

- RosenbergEThree cases of penile paraffinoma. Urology. 2007;70:372.

- Baumann LS, Halem ML. Lip silicone granulomatous foreign body reaction treated with Aldara (imiquimod 5%). Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:429-432.

Practice Points

- Taking a thorough history in patients with possible paraffinomas is vital, including a history of injectables even in the genital region.

- Biopsies in cosmetically sensitive areas must be given careful consideration. Clinical history must support the decision to pursue a definitive diagnosis.

- Early detection is critical in the management of paraffinomas, especially in anatomic locations where tissue preservation is of utmost importance.

FDA approves apomorphine sublingual film for ‘off’ episodes in Parkinson’s disease

, the manufacturer has announced. This marks the first approval for a sublingual therapy for this indication, which is defined as the re-emergence or worsening of Parkinson’s disease symptoms that have otherwise been controlled with standard care of levodopa/carbidopa, Sunovion reports. Almost 60% of patients with Parkinson’s disease experience off episodes.

The approval “affords healthcare providers with a needed option that can be added to their patients’ medication regimen to adequately address off episodes as their Parkinson’s disease progresses,” Stewart Factor, DO, professor of neurology and director of the Movement Disorders Program at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, said in a press release from the manufacturer.

“We know from our research and discussion with the Parkinson’s community that off episodes can significantly disrupt a patient’s daily life,” Todd Sherer, PhD, CEO of the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, said in the same release. He added that the Fox Foundation “supported early clinical development of sublingual apomorphine.”

The treatment is expected to be available in US pharmacies in September.

Disruptive symptoms

Off episodes can include periods of tremor, slowed movement, and stiffness and occur during daytime hours.

“Several years after a person is diagnosed with [Parkinson’s disease] they may notice problems such as having trouble getting out of bed in the morning or having difficulty getting out of a chair, or that they feel frozen while trying to walk as the effect of their maintenance medication diminishes,” Dr. Factor noted.

Subcutaneous infusion of the dopamine agonist apomorphine previously has shown benefit in treating persistent motor fluctuations in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Apomorphine hydrochloride sublingual film is a novel formulation of apomorphine. It dissolves under the tongue to help improve off episode symptoms as needed up to five times per day.

A phase 3 study of 109 patients that was published in December in Lancet Neurology showed that those who received the sublingual film therapy had a mean reduction of 11.1 points on the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III 30 minutes after dosing at the 12-week assessment. This was a significant improvement in motor symptoms versus those who received placebo (mean difference, -7.6 points; P = .0002).

In addition, initial clinical improvement was found 15 minutes after dosing.

The most frequently reported treatment-emergent adverse events in the study population were oropharyngeal reactions, followed by nausea, somnolence, and dizziness.

Long-term safety?

“The availability of this new apomorphine sublingual formulation, along with an inhaled formulation under development, will broaden the treatment options for off periods,” Angelo Antonini, MD, PhD, from University of Padua, Italy, wrote in an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Neurology.

Although the results were encouraging, he noted some caution should be heeded.

Because of “the high rate of oropharyngeal adverse events, long-term safety needs to be monitored once the product is registered and available for chronic use in patients with Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Antonini wrote.

Other safety information issued by the manufacturer includes a warning that patients who take the 5HT3 antagonists ondansetron, dolasetron, palonosetron, granisetron, or alosetron for nausea should not also use apomorphine hydrochloride sublingual film.

“People taking ondansetron together with apomorphine, the active ingredient in Kynmobi, have had very low blood pressure and lost consciousness or ‘blacked out,’ “ the warning notes.

It also should not be taken by individuals who are allergic to the ingredients in the medication, including sodium metabisulfite.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the manufacturer has announced. This marks the first approval for a sublingual therapy for this indication, which is defined as the re-emergence or worsening of Parkinson’s disease symptoms that have otherwise been controlled with standard care of levodopa/carbidopa, Sunovion reports. Almost 60% of patients with Parkinson’s disease experience off episodes.

The approval “affords healthcare providers with a needed option that can be added to their patients’ medication regimen to adequately address off episodes as their Parkinson’s disease progresses,” Stewart Factor, DO, professor of neurology and director of the Movement Disorders Program at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, said in a press release from the manufacturer.

“We know from our research and discussion with the Parkinson’s community that off episodes can significantly disrupt a patient’s daily life,” Todd Sherer, PhD, CEO of the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, said in the same release. He added that the Fox Foundation “supported early clinical development of sublingual apomorphine.”

The treatment is expected to be available in US pharmacies in September.

Disruptive symptoms

Off episodes can include periods of tremor, slowed movement, and stiffness and occur during daytime hours.

“Several years after a person is diagnosed with [Parkinson’s disease] they may notice problems such as having trouble getting out of bed in the morning or having difficulty getting out of a chair, or that they feel frozen while trying to walk as the effect of their maintenance medication diminishes,” Dr. Factor noted.

Subcutaneous infusion of the dopamine agonist apomorphine previously has shown benefit in treating persistent motor fluctuations in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Apomorphine hydrochloride sublingual film is a novel formulation of apomorphine. It dissolves under the tongue to help improve off episode symptoms as needed up to five times per day.

A phase 3 study of 109 patients that was published in December in Lancet Neurology showed that those who received the sublingual film therapy had a mean reduction of 11.1 points on the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III 30 minutes after dosing at the 12-week assessment. This was a significant improvement in motor symptoms versus those who received placebo (mean difference, -7.6 points; P = .0002).

In addition, initial clinical improvement was found 15 minutes after dosing.

The most frequently reported treatment-emergent adverse events in the study population were oropharyngeal reactions, followed by nausea, somnolence, and dizziness.

Long-term safety?

“The availability of this new apomorphine sublingual formulation, along with an inhaled formulation under development, will broaden the treatment options for off periods,” Angelo Antonini, MD, PhD, from University of Padua, Italy, wrote in an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Neurology.

Although the results were encouraging, he noted some caution should be heeded.

Because of “the high rate of oropharyngeal adverse events, long-term safety needs to be monitored once the product is registered and available for chronic use in patients with Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Antonini wrote.

Other safety information issued by the manufacturer includes a warning that patients who take the 5HT3 antagonists ondansetron, dolasetron, palonosetron, granisetron, or alosetron for nausea should not also use apomorphine hydrochloride sublingual film.

“People taking ondansetron together with apomorphine, the active ingredient in Kynmobi, have had very low blood pressure and lost consciousness or ‘blacked out,’ “ the warning notes.

It also should not be taken by individuals who are allergic to the ingredients in the medication, including sodium metabisulfite.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the manufacturer has announced. This marks the first approval for a sublingual therapy for this indication, which is defined as the re-emergence or worsening of Parkinson’s disease symptoms that have otherwise been controlled with standard care of levodopa/carbidopa, Sunovion reports. Almost 60% of patients with Parkinson’s disease experience off episodes.

The approval “affords healthcare providers with a needed option that can be added to their patients’ medication regimen to adequately address off episodes as their Parkinson’s disease progresses,” Stewart Factor, DO, professor of neurology and director of the Movement Disorders Program at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, said in a press release from the manufacturer.

“We know from our research and discussion with the Parkinson’s community that off episodes can significantly disrupt a patient’s daily life,” Todd Sherer, PhD, CEO of the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, said in the same release. He added that the Fox Foundation “supported early clinical development of sublingual apomorphine.”

The treatment is expected to be available in US pharmacies in September.

Disruptive symptoms

Off episodes can include periods of tremor, slowed movement, and stiffness and occur during daytime hours.

“Several years after a person is diagnosed with [Parkinson’s disease] they may notice problems such as having trouble getting out of bed in the morning or having difficulty getting out of a chair, or that they feel frozen while trying to walk as the effect of their maintenance medication diminishes,” Dr. Factor noted.

Subcutaneous infusion of the dopamine agonist apomorphine previously has shown benefit in treating persistent motor fluctuations in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Apomorphine hydrochloride sublingual film is a novel formulation of apomorphine. It dissolves under the tongue to help improve off episode symptoms as needed up to five times per day.

A phase 3 study of 109 patients that was published in December in Lancet Neurology showed that those who received the sublingual film therapy had a mean reduction of 11.1 points on the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III 30 minutes after dosing at the 12-week assessment. This was a significant improvement in motor symptoms versus those who received placebo (mean difference, -7.6 points; P = .0002).

In addition, initial clinical improvement was found 15 minutes after dosing.

The most frequently reported treatment-emergent adverse events in the study population were oropharyngeal reactions, followed by nausea, somnolence, and dizziness.

Long-term safety?

“The availability of this new apomorphine sublingual formulation, along with an inhaled formulation under development, will broaden the treatment options for off periods,” Angelo Antonini, MD, PhD, from University of Padua, Italy, wrote in an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Neurology.

Although the results were encouraging, he noted some caution should be heeded.

Because of “the high rate of oropharyngeal adverse events, long-term safety needs to be monitored once the product is registered and available for chronic use in patients with Parkinson’s disease,” Dr. Antonini wrote.

Other safety information issued by the manufacturer includes a warning that patients who take the 5HT3 antagonists ondansetron, dolasetron, palonosetron, granisetron, or alosetron for nausea should not also use apomorphine hydrochloride sublingual film.

“People taking ondansetron together with apomorphine, the active ingredient in Kynmobi, have had very low blood pressure and lost consciousness or ‘blacked out,’ “ the warning notes.

It also should not be taken by individuals who are allergic to the ingredients in the medication, including sodium metabisulfite.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type II After a Brachial Plexus and C6 Nerve Root Injury

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old man presented with an atrophied painful left arm of 17 years’ duration that began when he was hit by a car as a pedestrian. He sustained severe multisystem injuries from the accident, including left brachial plexus and C6 nerve root avulsion injury. When he regained consciousness after 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, he immediately noted diffuse pain throughout the body, especially in the left arm. Since the accident, the patient continued to have diminished sensation to touch and temperature in the left arm. He also had burning, throbbing, and electrical pain in the left arm with light touch as well as spontaneously. He was thoroughly evaluated by a neurologist and was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type II. For the treatment of pain, dorsal column stimulation and hemilaminectomy with exploration of the avulsed nerve root were attempted, both of which had minimal effect. He was maintained on hydromorphone, methadone, and oxazepam. He reported that for many years he was unable move out of bed due to the unbearable pain. With pain medications, he was able to regain most of his independence in his daily life, though the pain and other clinical aspects of CRPS still completely limited his use of the left arm.

Physical examination revealed glossy, cold, hairless skin with hypohidrosis of the left arm, forearm, and hand (Figures 1 and 2A). The left arm was conspicuously atrophied, with the forearm and hand erythematous. The fingers were taut, contracted, and edematous (Figure 2B), and the skin was unable to be pinched. The fingernails on the left hand had dystrophic changes including yellow color and brittleness with longitudinal ridges (Figure 3). The patient could activate the left bicep and tricep muscles against gravity but had minimal function of the deltoid muscle. He also had minimal movement of the left index finger and was unable to move any other digits of the left hand. The patient was continued on pain management treatments and physical therapy for his condition.

Complex regional pain syndrome is a neuropathic disorder of the extremities characterized by pain and a variety of autonomic and motor disturbances such as local edema, limited active range of motion, and vasomotor and trophic skin changes. There are 2 types of CRPS: type II is marked by explicit nerve injury and type I is not. The pathophysiology of CRPS is unknown.1-3

There is no definite set of diagnostic criteria for CRPS. The lack of any gold-standard diagnostic test for CRPS has made arriving at one valid, widely accepted set of diagnostic criteria impossible.1 There are 4 widely used sets of diagnostic criteria. One is the International Association for the Study of Pain diagnostic criteria defined in 1994.4 However, the criteria rely entirely on subjective symptoms and have been under great scrutiny due to their questionable validity.2 Veldman et al5 presented other widely used CRPS diagnostic criteria in their prospective study of 829 reflex sympathetic dystrophy patients, which paid particular attention to the early clinical manifestations of CRPS. In 1999, Bruehl et al2 proposed their own modified diagnostic criteria, which required physician-assessed signs in 2 of 4 categories to avoid the practice of exclusively relying on subjective symptoms. In addition, during a consensus meeting in Budapest, Hungary, a modified version of the Bruehl criteria was proposed.6 All 4 criteria rely solely on detailed history and physical examination, and the choice of diagnostic criteria remains subjective.

The pathophysiology of CRPS also remains unclear. There are several proposed mechanisms such as sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, abnormal inflammatory response, and central nervous system involvement.1 Psychologic factors, sequelae of nerve injury, and genetic predisposition also have been implicated in the pathophysiology of CRPS.1 It is likely that several mechanisms variably contribute to each presentation of CRPS.

Many dermatologic findings, in addition to neuromuscular symptoms, accompany CRPS and serve as important clues to making the clinical diagnosis. Complex regional pain syndrome has been thought to have 3 distinct sequential stages of CRPS.1,3,7 Stage 1—the acute stage—is marked by hyperalgesia, allodynia, sudomotor disturbances, and prominent edema. Stage 2—the dystrophic stage—is characterized by more marked pain and sensory dysfunction, vasomotor dysfunction, development of motor dysfunction, soft tissue edema, skin and articular soft tissue thickening, and development of dystrophic nail changes. Stage 3—the atrophic stage—is marked by decreased pain and sensory disturbances, markedly increased motor dysfunction, waxy atrophic skin changes, progression of dystrophic nail changes, and skeletal cystic and subchondral erosions with diffuse osteoporosis.1,3,7

The staging model, however, has been called into question.3 In a cluster analysis, Bruehl et al3 arrived at 3 relatively consistent CRPS patient subgroups that did not have notably different pain duration, suggesting the existence of 3 CRPS subtypes, not stages. Their study found that one of the subgroups best represented the clinical presentation of CRPS type II. This subgroup had the greatest pain and sensory abnormalities and the least vasomotor dysfunction of all 3 subgroups. Nonetheless, this study has not settled the discussion, as it only included 113 patients.3 Thus, with future studies, our understanding of CRPS in stages may change, which likely will impact how the clinical diagnosis is made.

There is a lack of high-quality evidence for most treatment interventions for CRPS8; however, the current practice is to use an interdisciplinary approach.1,9,10 The main therapeutic arm of this approach is rehabilitation; physical and occupational therapy can help improve range of motion, contracture, and atrophy. The other 2 arms of the approach are psychologic therapy to improve quality of life and pain management with pharmacologic therapy and/or invasive interventions. The choice of therapy remains empirical; trial and error should be expected in developing an adequate treatment plan for each individual patient.

Many aspects of CRPS remain unclear, and even our current understanding of the disease will inevitably change over time. The syndrome can cause life-changing morbidities in patients, and late diagnosis and treatment are associated with poor prognosis. Because there are many dermatologic findings associated with the disorder, it is crucial for dermatologists to clinically recognize the disorder and to refer patients to appropriate channels so that treatment can be started as soon as possible.

- Borchers A, Gershwin M. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive and critical review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:242-265.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, et al. External validation of IASP diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome and proposed research diagnostic criteria. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;81:147-154.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Gaker BS, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain. 2002;95:119-124.

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

- Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet. 1993;342:1012-1016.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RS, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2010;150:268-274.

- Sebastin SJ. Complex regional pain syndrome. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44:298-307.

- O’Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, et al. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009416.

- Hsu ES. Practical management of complex regional pain syndrome. Am J Ther. 2009;16:147-154.

- Stanton-Hicks MD, Burton AW, Bruehl SP, et al. An updated interdisciplinary clinical pathway for CRPS: report of an expert panel. Pain Pract. 2002;2:1-16.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old man presented with an atrophied painful left arm of 17 years’ duration that began when he was hit by a car as a pedestrian. He sustained severe multisystem injuries from the accident, including left brachial plexus and C6 nerve root avulsion injury. When he regained consciousness after 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, he immediately noted diffuse pain throughout the body, especially in the left arm. Since the accident, the patient continued to have diminished sensation to touch and temperature in the left arm. He also had burning, throbbing, and electrical pain in the left arm with light touch as well as spontaneously. He was thoroughly evaluated by a neurologist and was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type II. For the treatment of pain, dorsal column stimulation and hemilaminectomy with exploration of the avulsed nerve root were attempted, both of which had minimal effect. He was maintained on hydromorphone, methadone, and oxazepam. He reported that for many years he was unable move out of bed due to the unbearable pain. With pain medications, he was able to regain most of his independence in his daily life, though the pain and other clinical aspects of CRPS still completely limited his use of the left arm.

Physical examination revealed glossy, cold, hairless skin with hypohidrosis of the left arm, forearm, and hand (Figures 1 and 2A). The left arm was conspicuously atrophied, with the forearm and hand erythematous. The fingers were taut, contracted, and edematous (Figure 2B), and the skin was unable to be pinched. The fingernails on the left hand had dystrophic changes including yellow color and brittleness with longitudinal ridges (Figure 3). The patient could activate the left bicep and tricep muscles against gravity but had minimal function of the deltoid muscle. He also had minimal movement of the left index finger and was unable to move any other digits of the left hand. The patient was continued on pain management treatments and physical therapy for his condition.

Complex regional pain syndrome is a neuropathic disorder of the extremities characterized by pain and a variety of autonomic and motor disturbances such as local edema, limited active range of motion, and vasomotor and trophic skin changes. There are 2 types of CRPS: type II is marked by explicit nerve injury and type I is not. The pathophysiology of CRPS is unknown.1-3

There is no definite set of diagnostic criteria for CRPS. The lack of any gold-standard diagnostic test for CRPS has made arriving at one valid, widely accepted set of diagnostic criteria impossible.1 There are 4 widely used sets of diagnostic criteria. One is the International Association for the Study of Pain diagnostic criteria defined in 1994.4 However, the criteria rely entirely on subjective symptoms and have been under great scrutiny due to their questionable validity.2 Veldman et al5 presented other widely used CRPS diagnostic criteria in their prospective study of 829 reflex sympathetic dystrophy patients, which paid particular attention to the early clinical manifestations of CRPS. In 1999, Bruehl et al2 proposed their own modified diagnostic criteria, which required physician-assessed signs in 2 of 4 categories to avoid the practice of exclusively relying on subjective symptoms. In addition, during a consensus meeting in Budapest, Hungary, a modified version of the Bruehl criteria was proposed.6 All 4 criteria rely solely on detailed history and physical examination, and the choice of diagnostic criteria remains subjective.

The pathophysiology of CRPS also remains unclear. There are several proposed mechanisms such as sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, abnormal inflammatory response, and central nervous system involvement.1 Psychologic factors, sequelae of nerve injury, and genetic predisposition also have been implicated in the pathophysiology of CRPS.1 It is likely that several mechanisms variably contribute to each presentation of CRPS.

Many dermatologic findings, in addition to neuromuscular symptoms, accompany CRPS and serve as important clues to making the clinical diagnosis. Complex regional pain syndrome has been thought to have 3 distinct sequential stages of CRPS.1,3,7 Stage 1—the acute stage—is marked by hyperalgesia, allodynia, sudomotor disturbances, and prominent edema. Stage 2—the dystrophic stage—is characterized by more marked pain and sensory dysfunction, vasomotor dysfunction, development of motor dysfunction, soft tissue edema, skin and articular soft tissue thickening, and development of dystrophic nail changes. Stage 3—the atrophic stage—is marked by decreased pain and sensory disturbances, markedly increased motor dysfunction, waxy atrophic skin changes, progression of dystrophic nail changes, and skeletal cystic and subchondral erosions with diffuse osteoporosis.1,3,7

The staging model, however, has been called into question.3 In a cluster analysis, Bruehl et al3 arrived at 3 relatively consistent CRPS patient subgroups that did not have notably different pain duration, suggesting the existence of 3 CRPS subtypes, not stages. Their study found that one of the subgroups best represented the clinical presentation of CRPS type II. This subgroup had the greatest pain and sensory abnormalities and the least vasomotor dysfunction of all 3 subgroups. Nonetheless, this study has not settled the discussion, as it only included 113 patients.3 Thus, with future studies, our understanding of CRPS in stages may change, which likely will impact how the clinical diagnosis is made.

There is a lack of high-quality evidence for most treatment interventions for CRPS8; however, the current practice is to use an interdisciplinary approach.1,9,10 The main therapeutic arm of this approach is rehabilitation; physical and occupational therapy can help improve range of motion, contracture, and atrophy. The other 2 arms of the approach are psychologic therapy to improve quality of life and pain management with pharmacologic therapy and/or invasive interventions. The choice of therapy remains empirical; trial and error should be expected in developing an adequate treatment plan for each individual patient.

Many aspects of CRPS remain unclear, and even our current understanding of the disease will inevitably change over time. The syndrome can cause life-changing morbidities in patients, and late diagnosis and treatment are associated with poor prognosis. Because there are many dermatologic findings associated with the disorder, it is crucial for dermatologists to clinically recognize the disorder and to refer patients to appropriate channels so that treatment can be started as soon as possible.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old man presented with an atrophied painful left arm of 17 years’ duration that began when he was hit by a car as a pedestrian. He sustained severe multisystem injuries from the accident, including left brachial plexus and C6 nerve root avulsion injury. When he regained consciousness after 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, he immediately noted diffuse pain throughout the body, especially in the left arm. Since the accident, the patient continued to have diminished sensation to touch and temperature in the left arm. He also had burning, throbbing, and electrical pain in the left arm with light touch as well as spontaneously. He was thoroughly evaluated by a neurologist and was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type II. For the treatment of pain, dorsal column stimulation and hemilaminectomy with exploration of the avulsed nerve root were attempted, both of which had minimal effect. He was maintained on hydromorphone, methadone, and oxazepam. He reported that for many years he was unable move out of bed due to the unbearable pain. With pain medications, he was able to regain most of his independence in his daily life, though the pain and other clinical aspects of CRPS still completely limited his use of the left arm.

Physical examination revealed glossy, cold, hairless skin with hypohidrosis of the left arm, forearm, and hand (Figures 1 and 2A). The left arm was conspicuously atrophied, with the forearm and hand erythematous. The fingers were taut, contracted, and edematous (Figure 2B), and the skin was unable to be pinched. The fingernails on the left hand had dystrophic changes including yellow color and brittleness with longitudinal ridges (Figure 3). The patient could activate the left bicep and tricep muscles against gravity but had minimal function of the deltoid muscle. He also had minimal movement of the left index finger and was unable to move any other digits of the left hand. The patient was continued on pain management treatments and physical therapy for his condition.

Complex regional pain syndrome is a neuropathic disorder of the extremities characterized by pain and a variety of autonomic and motor disturbances such as local edema, limited active range of motion, and vasomotor and trophic skin changes. There are 2 types of CRPS: type II is marked by explicit nerve injury and type I is not. The pathophysiology of CRPS is unknown.1-3

There is no definite set of diagnostic criteria for CRPS. The lack of any gold-standard diagnostic test for CRPS has made arriving at one valid, widely accepted set of diagnostic criteria impossible.1 There are 4 widely used sets of diagnostic criteria. One is the International Association for the Study of Pain diagnostic criteria defined in 1994.4 However, the criteria rely entirely on subjective symptoms and have been under great scrutiny due to their questionable validity.2 Veldman et al5 presented other widely used CRPS diagnostic criteria in their prospective study of 829 reflex sympathetic dystrophy patients, which paid particular attention to the early clinical manifestations of CRPS. In 1999, Bruehl et al2 proposed their own modified diagnostic criteria, which required physician-assessed signs in 2 of 4 categories to avoid the practice of exclusively relying on subjective symptoms. In addition, during a consensus meeting in Budapest, Hungary, a modified version of the Bruehl criteria was proposed.6 All 4 criteria rely solely on detailed history and physical examination, and the choice of diagnostic criteria remains subjective.

The pathophysiology of CRPS also remains unclear. There are several proposed mechanisms such as sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, abnormal inflammatory response, and central nervous system involvement.1 Psychologic factors, sequelae of nerve injury, and genetic predisposition also have been implicated in the pathophysiology of CRPS.1 It is likely that several mechanisms variably contribute to each presentation of CRPS.

Many dermatologic findings, in addition to neuromuscular symptoms, accompany CRPS and serve as important clues to making the clinical diagnosis. Complex regional pain syndrome has been thought to have 3 distinct sequential stages of CRPS.1,3,7 Stage 1—the acute stage—is marked by hyperalgesia, allodynia, sudomotor disturbances, and prominent edema. Stage 2—the dystrophic stage—is characterized by more marked pain and sensory dysfunction, vasomotor dysfunction, development of motor dysfunction, soft tissue edema, skin and articular soft tissue thickening, and development of dystrophic nail changes. Stage 3—the atrophic stage—is marked by decreased pain and sensory disturbances, markedly increased motor dysfunction, waxy atrophic skin changes, progression of dystrophic nail changes, and skeletal cystic and subchondral erosions with diffuse osteoporosis.1,3,7

The staging model, however, has been called into question.3 In a cluster analysis, Bruehl et al3 arrived at 3 relatively consistent CRPS patient subgroups that did not have notably different pain duration, suggesting the existence of 3 CRPS subtypes, not stages. Their study found that one of the subgroups best represented the clinical presentation of CRPS type II. This subgroup had the greatest pain and sensory abnormalities and the least vasomotor dysfunction of all 3 subgroups. Nonetheless, this study has not settled the discussion, as it only included 113 patients.3 Thus, with future studies, our understanding of CRPS in stages may change, which likely will impact how the clinical diagnosis is made.

There is a lack of high-quality evidence for most treatment interventions for CRPS8; however, the current practice is to use an interdisciplinary approach.1,9,10 The main therapeutic arm of this approach is rehabilitation; physical and occupational therapy can help improve range of motion, contracture, and atrophy. The other 2 arms of the approach are psychologic therapy to improve quality of life and pain management with pharmacologic therapy and/or invasive interventions. The choice of therapy remains empirical; trial and error should be expected in developing an adequate treatment plan for each individual patient.

Many aspects of CRPS remain unclear, and even our current understanding of the disease will inevitably change over time. The syndrome can cause life-changing morbidities in patients, and late diagnosis and treatment are associated with poor prognosis. Because there are many dermatologic findings associated with the disorder, it is crucial for dermatologists to clinically recognize the disorder and to refer patients to appropriate channels so that treatment can be started as soon as possible.

- Borchers A, Gershwin M. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive and critical review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:242-265.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, et al. External validation of IASP diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome and proposed research diagnostic criteria. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;81:147-154.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Gaker BS, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain. 2002;95:119-124.

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

- Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet. 1993;342:1012-1016.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RS, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2010;150:268-274.

- Sebastin SJ. Complex regional pain syndrome. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44:298-307.

- O’Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, et al. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009416.

- Hsu ES. Practical management of complex regional pain syndrome. Am J Ther. 2009;16:147-154.

- Stanton-Hicks MD, Burton AW, Bruehl SP, et al. An updated interdisciplinary clinical pathway for CRPS: report of an expert panel. Pain Pract. 2002;2:1-16.

- Borchers A, Gershwin M. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive and critical review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:242-265.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, et al. External validation of IASP diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome and proposed research diagnostic criteria. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;81:147-154.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Gaker BS, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain. 2002;95:119-124.

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

- Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet. 1993;342:1012-1016.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RS, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2010;150:268-274.

- Sebastin SJ. Complex regional pain syndrome. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44:298-307.

- O’Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, et al. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009416.

- Hsu ES. Practical management of complex regional pain syndrome. Am J Ther. 2009;16:147-154.

- Stanton-Hicks MD, Burton AW, Bruehl SP, et al. An updated interdisciplinary clinical pathway for CRPS: report of an expert panel. Pain Pract. 2002;2:1-16.

Practice Points

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a neuropathic disorder of the extremities characterized by pain, a variety of autonomic and motor disturbances, and dermatologic findings.

- Early recognition of CRPS is critical, as it presents life-changing morbidities to patients.

- A multidisciplinary treatment approach with physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychological support, and pain control is needed for the management of CRPS.

Chronic migraine is associated with changes in the amygdala

, according to researchers. This increased connectivity is associated with clinical and affective measures. The data suggest that changes in the amygdala’s structure and function may play a role in the transformation to chronic migraine, according to the researchers. The study was presented online as part of the American Academy of Neurology’s 2020 Science Highlights.

Approximately 3% of patients with episodic migraine progress to chronic migraine each year. Chronic migraine is associated with increased headache frequency, greater disability, and increased psychiatric comorbidities. The pathophysiological mechanisms of the transformation from episodic to chronic migraine are not completely understood.

Danielle D. DeSouza, PhD, instructor in neurology at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues sought to investigate the role of the amygdala in the transformation of migraine. The amygdala is involved in nociceptive processing, emotional responses, and affective states such as depression and anxiety. Researchers have suggested that alterations in the structure or function of the amygdala might contribute to the worsening of pain and mood that coincides with the transformation of migraine.

Dr. DeSouza and colleagues enrolled 88 patients with migraine, diagnosed according to International Classification of Headache Disorders–3 criteria, in their study. Forty-four patients (36 women; mean age, 37.8 years) had chronic migraine, and 44 patients (36 women; mean age, 37.5 years) had episodic migraine. Participants underwent 3T MRI scanning during which investigators acquired T1-weighted structural and resting-state images of the brain. Participants also completed self-report questionnaires to evaluate depression and somatization (Patient Health Questionnaire), anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale), pain catastrophizing (Pain Catastrophizing Scale), headache frequency, and headache intensity.

The investigators examined resting-state functional connectivity between the amygdala and the following three brain networks: DMN, salience network (SN), and central executive network (CEN). They assessed amygdala volume with voxel-based morphometry.

Analyses indicated that connectivity between the left amygdala and the DMN (i.e., the medial prefrontal cortex and the precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex) was increased in patients with chronic migraine, compared with those with episodic migraine. In all patients, resting-state functional connectivity between the amygdala and the DMN was positively associated with headache frequency. Connectivity between the left amygdala and the SN was positively associated with headache intensity, and connectivity between the right amygdala and the CEN was positively associated with pain catastrophizing. Both of these findings held in all patients.

In addition, Dr. DeSouza and colleagues found that bilateral amygdala volumes, including the basolateral and superficial/corticoid nuclei, were increased in patients with chronic migraine, compared with those with episodic migraine. Headache intensity and depression predicted differences in right amygdala volume, and depression alone predicted differences in left amygdala volume.

Dr. DeSouza reported no disclosures. One of the investigators acts as an adviser to Alder, Allergan, Amgen, Biohaven, Curex, Teva, and Xoc about matters unrelated to this study.

SOURCE: DeSouza DD et al. AAN 2020, Abstract 46914.

, according to researchers. This increased connectivity is associated with clinical and affective measures. The data suggest that changes in the amygdala’s structure and function may play a role in the transformation to chronic migraine, according to the researchers. The study was presented online as part of the American Academy of Neurology’s 2020 Science Highlights.

Approximately 3% of patients with episodic migraine progress to chronic migraine each year. Chronic migraine is associated with increased headache frequency, greater disability, and increased psychiatric comorbidities. The pathophysiological mechanisms of the transformation from episodic to chronic migraine are not completely understood.