User login

Top patient cases

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community to seek advice from fellow GIs on therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical cases shared in the forum recently:

1. Eosinophilic esophagitis and stricture

A tight stricture in the mid-esophagus of a 25-year-old patient prevented the physician from passing the scope on multiple occasions within 5 weeks.

2. Behcet’s

A 41-year-old patient with Behcet’s disease and celiac disease originally reported joint pain and diarrhea, which subsided after treatment with prednisone and sulfasalazine. Despite a limited diet and therapeutic levels of Humira, her symptoms resurfaced 6 months later with loose stools and urgency.

3. Ectopic varices with portal vein thrombosis

This case involves a 49-year-old male who developed necrotizing pancreatitis due to microlithiasis in 2008, followed by pyrexia with three pyogenic liver abscesses this past May. The attending physician solicited advice from the GI community on management of this patient’s portal hypertension.

4. Firefighters at higher CRC risk?

Join this informative discussion about a reported “1.21 times greater risk” for colorectal cancer in firefighters, and increased screening for this demographic.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community to seek advice from fellow GIs on therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical cases shared in the forum recently:

1. Eosinophilic esophagitis and stricture

A tight stricture in the mid-esophagus of a 25-year-old patient prevented the physician from passing the scope on multiple occasions within 5 weeks.

2. Behcet’s

A 41-year-old patient with Behcet’s disease and celiac disease originally reported joint pain and diarrhea, which subsided after treatment with prednisone and sulfasalazine. Despite a limited diet and therapeutic levels of Humira, her symptoms resurfaced 6 months later with loose stools and urgency.

3. Ectopic varices with portal vein thrombosis

This case involves a 49-year-old male who developed necrotizing pancreatitis due to microlithiasis in 2008, followed by pyrexia with three pyogenic liver abscesses this past May. The attending physician solicited advice from the GI community on management of this patient’s portal hypertension.

4. Firefighters at higher CRC risk?

Join this informative discussion about a reported “1.21 times greater risk” for colorectal cancer in firefighters, and increased screening for this demographic.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community to seek advice from fellow GIs on therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses.

In case you missed it, here are the most popular clinical cases shared in the forum recently:

1. Eosinophilic esophagitis and stricture

A tight stricture in the mid-esophagus of a 25-year-old patient prevented the physician from passing the scope on multiple occasions within 5 weeks.

2. Behcet’s

A 41-year-old patient with Behcet’s disease and celiac disease originally reported joint pain and diarrhea, which subsided after treatment with prednisone and sulfasalazine. Despite a limited diet and therapeutic levels of Humira, her symptoms resurfaced 6 months later with loose stools and urgency.

3. Ectopic varices with portal vein thrombosis

This case involves a 49-year-old male who developed necrotizing pancreatitis due to microlithiasis in 2008, followed by pyrexia with three pyogenic liver abscesses this past May. The attending physician solicited advice from the GI community on management of this patient’s portal hypertension.

4. Firefighters at higher CRC risk?

Join this informative discussion about a reported “1.21 times greater risk” for colorectal cancer in firefighters, and increased screening for this demographic.

More clinical cases and discussions are at https://community.gastro.org/discussions.

A Gift to the AGA Research Foundation in Your Will

A simple, flexible and versatile way to ensure the AGA Research Foundation can continue to help spark the scientific breakthroughs of today so clinicians will have the tools to improve care tomorrow is through a gift in your will or living trust, known as a charitable bequest.

To make a charitable bequest, you need a current will or living trust. Your gift can be made as a percentage of your estate. Or you can make a specific bequest by giving a certain amount of cash, securities or property. After your lifetime, the Foundation receives your gift.

Including the AGA Research Foundation in your will is a popular gift to give because it is:

• Affordable. The actual giving of your gift occurs after your lifetime, so your current income is not affected.

• Flexible. Until your will goes into effect, you are free to alter your plans or change your mind.

• Versatile. You can give a specific item, a set amount of money or a percentage of your estate. You can also make your gift contingent upon certain events.

We hope you’ll consider including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will or liv-ing trust. It’s simple – just a few sentences in your will or trust are all that is needed. The official bequest language for the AGA Research Foundation is: “I, [name], of [city, state, ZIP], give, devise and bequeath to the AGA Research Foundation [written amount or per-centage of the estate or description of property] for its unrestricted use and purpose.”

By including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will, you can help fill the funding gap and protect the next generation of investigators.

For more information, visit http://gastro.planmylegacy.org/ or contact us at foundation@gastro.org.

A simple, flexible and versatile way to ensure the AGA Research Foundation can continue to help spark the scientific breakthroughs of today so clinicians will have the tools to improve care tomorrow is through a gift in your will or living trust, known as a charitable bequest.

To make a charitable bequest, you need a current will or living trust. Your gift can be made as a percentage of your estate. Or you can make a specific bequest by giving a certain amount of cash, securities or property. After your lifetime, the Foundation receives your gift.

Including the AGA Research Foundation in your will is a popular gift to give because it is:

• Affordable. The actual giving of your gift occurs after your lifetime, so your current income is not affected.

• Flexible. Until your will goes into effect, you are free to alter your plans or change your mind.

• Versatile. You can give a specific item, a set amount of money or a percentage of your estate. You can also make your gift contingent upon certain events.

We hope you’ll consider including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will or liv-ing trust. It’s simple – just a few sentences in your will or trust are all that is needed. The official bequest language for the AGA Research Foundation is: “I, [name], of [city, state, ZIP], give, devise and bequeath to the AGA Research Foundation [written amount or per-centage of the estate or description of property] for its unrestricted use and purpose.”

By including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will, you can help fill the funding gap and protect the next generation of investigators.

For more information, visit http://gastro.planmylegacy.org/ or contact us at foundation@gastro.org.

A simple, flexible and versatile way to ensure the AGA Research Foundation can continue to help spark the scientific breakthroughs of today so clinicians will have the tools to improve care tomorrow is through a gift in your will or living trust, known as a charitable bequest.

To make a charitable bequest, you need a current will or living trust. Your gift can be made as a percentage of your estate. Or you can make a specific bequest by giving a certain amount of cash, securities or property. After your lifetime, the Foundation receives your gift.

Including the AGA Research Foundation in your will is a popular gift to give because it is:

• Affordable. The actual giving of your gift occurs after your lifetime, so your current income is not affected.

• Flexible. Until your will goes into effect, you are free to alter your plans or change your mind.

• Versatile. You can give a specific item, a set amount of money or a percentage of your estate. You can also make your gift contingent upon certain events.

We hope you’ll consider including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will or liv-ing trust. It’s simple – just a few sentences in your will or trust are all that is needed. The official bequest language for the AGA Research Foundation is: “I, [name], of [city, state, ZIP], give, devise and bequeath to the AGA Research Foundation [written amount or per-centage of the estate or description of property] for its unrestricted use and purpose.”

By including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will, you can help fill the funding gap and protect the next generation of investigators.

For more information, visit http://gastro.planmylegacy.org/ or contact us at foundation@gastro.org.

Gestational weight outside guidelines adversely affects mothers, babies

Gestational weight gain above or below the level recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines resulted in significantly worse outcomes for mothers and babies, according to data from nearly 30,000 women.

Previous studies of the relationship between gestational weight gain and maternal and neonatal outcomes have been limited by “small sample sizes, single sites, restricted reporting of outcomes, and a lack of racial-ethnic diversity,” Michelle A. Kominiarek, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago and her colleagues wrote . To determine the effects of gestational weight gain on a large and more diverse population, the researchers conducted a secondary analysis of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network’s Assessment of Perinatal Excellence study. The findings were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Gestational weight gain above the amount recommended by IOM guidelines was significantly associated with adverse outcomes in neonates, including macrosomia (adjusted odds ratio, 2.66), shoulder dystocia (aOR, 1.74), and neonatal hypoglycemia (aOR, 1.60).

In further multivariate analysis, adverse maternal outcomes associated with gestational weight gain above that recommended by the guidelines included hypertensive diseases of pregnancy for any parity (aOR, 1.84) and increased risk of cesarean delivery in nulliparous and multiparous women (aORs, 1.44 and 1.26, respectively).

Gestational weight gain below the recommended amount was associated with both spontaneous (aOR, 1.50) and indicated (aOR, 1.34) preterm birth. Weight gain above the guidelines was associated with a greater risk of indicated preterm birth only (aOR, 1.24).

The study population included 29,861 women at 25 hospitals over a 3-year period. Of these, 51% had gestational weight gains above the amount recommended by the IOM guidelines and 21% had gestational weight gains below it. The researchers calculated gestational weight gain by subtracting prepregnancy weight from delivery weight or, if prepregnancy weight was not available, by subtracting weight at the first prenatal visit at 13 weeks of gestation or earlier from delivery weight.

The study findings were limited by the use of self-reported prepregnancy weight and the possible effects of changes to the guidelines with respect to obese patients, the researchers said. However, the results support those from previous studies, and the “noted strengths include analysis of 29,861 women representative of the United States with rigorous ascertainment of outcomes and calculation of gestational weight gain to account for the wide range of gestational ages at delivery,” Dr. Kominiarek and her associates wrote.

Overall, the data support efforts to educate women on health behaviors and how gestational weight gain affects them and their infants, and additional research is needed to help women meet their goals for appropriate gestational weight, the researchers concluded.

SOURCE: Kominiarek MA et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;132(4):875-81.

“We are struggling with an obesity epidemic in this country, and pregnancy accounts for a risk time for women to gain excessive weight,” Martina L. Badell, MD, said in an interview. “This is a very well-designed large study which attempted to systematically evaluate the adverse perinatal outcomes associated with inappropriate weight gain in pregnancy across a diverse group of women.”

She emphasized that “the take home message is the importance of counseling regarding weight gain in pregnancy and monitoring it closely in real time as the associated risks are significant and potentially avoidable. The first step to solving a problem is adequately quantifying it, and this study does just that. The next step is giving this information to pregnant women along with making weight gain a part of the discussion prior to pregnancy and at every prenatal visit.”

Dr. Badell added, “Ideally, the weight gain for an individual pregnant women would be tracked and discussed with her during each prenatal visit. If she is below or above the recommendations, the risks associated with this could be discussed along with strategies to get/stay on track. In an ideal world, women struggling with weight gain goals in pregnancy would have access to a dietitian. However, in reality, ob.gyn. offices will likely need to come up with patient education handouts or staff education.”

Another useful avenue for research would be assessing the effects of patient education, Dr. Badell said. “The next best step would be implementing a study to assess if education of women during pregnancy about their individual weight gain at each visit and discussion regarding perinatal risks affects ultimate weight gain and reduces risks. Additionally, education could begin in the preconception phase as this knowledge is likely important even prior to pregnancy. Finally, studies are needed on interventions such as working with dietitians or patient education classes once a woman has been identified as not being within weight gain goals to evaluate if these can alter weight gain and improve outcomes.”

Dr. Badell is a maternal-fetal medicine specialist in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, Atlanta. She was asked to comment on the findings of Kominiarek MA et al. Dr. Badell had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

“We are struggling with an obesity epidemic in this country, and pregnancy accounts for a risk time for women to gain excessive weight,” Martina L. Badell, MD, said in an interview. “This is a very well-designed large study which attempted to systematically evaluate the adverse perinatal outcomes associated with inappropriate weight gain in pregnancy across a diverse group of women.”

She emphasized that “the take home message is the importance of counseling regarding weight gain in pregnancy and monitoring it closely in real time as the associated risks are significant and potentially avoidable. The first step to solving a problem is adequately quantifying it, and this study does just that. The next step is giving this information to pregnant women along with making weight gain a part of the discussion prior to pregnancy and at every prenatal visit.”

Dr. Badell added, “Ideally, the weight gain for an individual pregnant women would be tracked and discussed with her during each prenatal visit. If she is below or above the recommendations, the risks associated with this could be discussed along with strategies to get/stay on track. In an ideal world, women struggling with weight gain goals in pregnancy would have access to a dietitian. However, in reality, ob.gyn. offices will likely need to come up with patient education handouts or staff education.”

Another useful avenue for research would be assessing the effects of patient education, Dr. Badell said. “The next best step would be implementing a study to assess if education of women during pregnancy about their individual weight gain at each visit and discussion regarding perinatal risks affects ultimate weight gain and reduces risks. Additionally, education could begin in the preconception phase as this knowledge is likely important even prior to pregnancy. Finally, studies are needed on interventions such as working with dietitians or patient education classes once a woman has been identified as not being within weight gain goals to evaluate if these can alter weight gain and improve outcomes.”

Dr. Badell is a maternal-fetal medicine specialist in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, Atlanta. She was asked to comment on the findings of Kominiarek MA et al. Dr. Badell had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

“We are struggling with an obesity epidemic in this country, and pregnancy accounts for a risk time for women to gain excessive weight,” Martina L. Badell, MD, said in an interview. “This is a very well-designed large study which attempted to systematically evaluate the adverse perinatal outcomes associated with inappropriate weight gain in pregnancy across a diverse group of women.”

She emphasized that “the take home message is the importance of counseling regarding weight gain in pregnancy and monitoring it closely in real time as the associated risks are significant and potentially avoidable. The first step to solving a problem is adequately quantifying it, and this study does just that. The next step is giving this information to pregnant women along with making weight gain a part of the discussion prior to pregnancy and at every prenatal visit.”

Dr. Badell added, “Ideally, the weight gain for an individual pregnant women would be tracked and discussed with her during each prenatal visit. If she is below or above the recommendations, the risks associated with this could be discussed along with strategies to get/stay on track. In an ideal world, women struggling with weight gain goals in pregnancy would have access to a dietitian. However, in reality, ob.gyn. offices will likely need to come up with patient education handouts or staff education.”

Another useful avenue for research would be assessing the effects of patient education, Dr. Badell said. “The next best step would be implementing a study to assess if education of women during pregnancy about their individual weight gain at each visit and discussion regarding perinatal risks affects ultimate weight gain and reduces risks. Additionally, education could begin in the preconception phase as this knowledge is likely important even prior to pregnancy. Finally, studies are needed on interventions such as working with dietitians or patient education classes once a woman has been identified as not being within weight gain goals to evaluate if these can alter weight gain and improve outcomes.”

Dr. Badell is a maternal-fetal medicine specialist in the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, Atlanta. She was asked to comment on the findings of Kominiarek MA et al. Dr. Badell had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Gestational weight gain above or below the level recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines resulted in significantly worse outcomes for mothers and babies, according to data from nearly 30,000 women.

Previous studies of the relationship between gestational weight gain and maternal and neonatal outcomes have been limited by “small sample sizes, single sites, restricted reporting of outcomes, and a lack of racial-ethnic diversity,” Michelle A. Kominiarek, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago and her colleagues wrote . To determine the effects of gestational weight gain on a large and more diverse population, the researchers conducted a secondary analysis of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network’s Assessment of Perinatal Excellence study. The findings were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Gestational weight gain above the amount recommended by IOM guidelines was significantly associated with adverse outcomes in neonates, including macrosomia (adjusted odds ratio, 2.66), shoulder dystocia (aOR, 1.74), and neonatal hypoglycemia (aOR, 1.60).

In further multivariate analysis, adverse maternal outcomes associated with gestational weight gain above that recommended by the guidelines included hypertensive diseases of pregnancy for any parity (aOR, 1.84) and increased risk of cesarean delivery in nulliparous and multiparous women (aORs, 1.44 and 1.26, respectively).

Gestational weight gain below the recommended amount was associated with both spontaneous (aOR, 1.50) and indicated (aOR, 1.34) preterm birth. Weight gain above the guidelines was associated with a greater risk of indicated preterm birth only (aOR, 1.24).

The study population included 29,861 women at 25 hospitals over a 3-year period. Of these, 51% had gestational weight gains above the amount recommended by the IOM guidelines and 21% had gestational weight gains below it. The researchers calculated gestational weight gain by subtracting prepregnancy weight from delivery weight or, if prepregnancy weight was not available, by subtracting weight at the first prenatal visit at 13 weeks of gestation or earlier from delivery weight.

The study findings were limited by the use of self-reported prepregnancy weight and the possible effects of changes to the guidelines with respect to obese patients, the researchers said. However, the results support those from previous studies, and the “noted strengths include analysis of 29,861 women representative of the United States with rigorous ascertainment of outcomes and calculation of gestational weight gain to account for the wide range of gestational ages at delivery,” Dr. Kominiarek and her associates wrote.

Overall, the data support efforts to educate women on health behaviors and how gestational weight gain affects them and their infants, and additional research is needed to help women meet their goals for appropriate gestational weight, the researchers concluded.

SOURCE: Kominiarek MA et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;132(4):875-81.

Gestational weight gain above or below the level recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines resulted in significantly worse outcomes for mothers and babies, according to data from nearly 30,000 women.

Previous studies of the relationship between gestational weight gain and maternal and neonatal outcomes have been limited by “small sample sizes, single sites, restricted reporting of outcomes, and a lack of racial-ethnic diversity,” Michelle A. Kominiarek, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago and her colleagues wrote . To determine the effects of gestational weight gain on a large and more diverse population, the researchers conducted a secondary analysis of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network’s Assessment of Perinatal Excellence study. The findings were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Gestational weight gain above the amount recommended by IOM guidelines was significantly associated with adverse outcomes in neonates, including macrosomia (adjusted odds ratio, 2.66), shoulder dystocia (aOR, 1.74), and neonatal hypoglycemia (aOR, 1.60).

In further multivariate analysis, adverse maternal outcomes associated with gestational weight gain above that recommended by the guidelines included hypertensive diseases of pregnancy for any parity (aOR, 1.84) and increased risk of cesarean delivery in nulliparous and multiparous women (aORs, 1.44 and 1.26, respectively).

Gestational weight gain below the recommended amount was associated with both spontaneous (aOR, 1.50) and indicated (aOR, 1.34) preterm birth. Weight gain above the guidelines was associated with a greater risk of indicated preterm birth only (aOR, 1.24).

The study population included 29,861 women at 25 hospitals over a 3-year period. Of these, 51% had gestational weight gains above the amount recommended by the IOM guidelines and 21% had gestational weight gains below it. The researchers calculated gestational weight gain by subtracting prepregnancy weight from delivery weight or, if prepregnancy weight was not available, by subtracting weight at the first prenatal visit at 13 weeks of gestation or earlier from delivery weight.

The study findings were limited by the use of self-reported prepregnancy weight and the possible effects of changes to the guidelines with respect to obese patients, the researchers said. However, the results support those from previous studies, and the “noted strengths include analysis of 29,861 women representative of the United States with rigorous ascertainment of outcomes and calculation of gestational weight gain to account for the wide range of gestational ages at delivery,” Dr. Kominiarek and her associates wrote.

Overall, the data support efforts to educate women on health behaviors and how gestational weight gain affects them and their infants, and additional research is needed to help women meet their goals for appropriate gestational weight, the researchers concluded.

SOURCE: Kominiarek MA et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;132(4):875-81.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Gestational weight gain or loss is a significant risk factor for adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Major finding: Gestational weight gain above the recommended amount was significantly associated with adverse outcomes in neonates, including macrosomia (adjusted odds ratio, 2.66), shoulder dystocia (aOR, 1.74), and neonatal hypoglycemia (aOR, 1.60).

Study details: The data came from 29,861 women who delivered at 25 hospitals across the United States on randomly selected days during a 3-year period.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The study was supported in part by various grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Center for Research Resources.

Source: Kominiarek MA et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;132(4):875-81.

Fish oil phoenix

A 4 g/day dose of the triglyceride-reducing drug Vascepa (Amarin), compared to placebo, was associated with a 25% lower risk of a heart attack, a stroke, an intervention for arterial thrombosis, or chest pain requiring a hospitalization in a study of 8,179 people who had high triglycerides and previous cardiovascular disorders or diabetes and another risk factor for heart disease.

In the ASCEND study, presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, 1 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids showed no net cardiovascular benefits in people with diabetes and no known cardiovascular disease.

The results of the Amarin study, announced in a press release, are slated for presentation at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in November.

A 4 g/day dose of the triglyceride-reducing drug Vascepa (Amarin), compared to placebo, was associated with a 25% lower risk of a heart attack, a stroke, an intervention for arterial thrombosis, or chest pain requiring a hospitalization in a study of 8,179 people who had high triglycerides and previous cardiovascular disorders or diabetes and another risk factor for heart disease.

In the ASCEND study, presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, 1 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids showed no net cardiovascular benefits in people with diabetes and no known cardiovascular disease.

The results of the Amarin study, announced in a press release, are slated for presentation at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in November.

A 4 g/day dose of the triglyceride-reducing drug Vascepa (Amarin), compared to placebo, was associated with a 25% lower risk of a heart attack, a stroke, an intervention for arterial thrombosis, or chest pain requiring a hospitalization in a study of 8,179 people who had high triglycerides and previous cardiovascular disorders or diabetes and another risk factor for heart disease.

In the ASCEND study, presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, 1 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids showed no net cardiovascular benefits in people with diabetes and no known cardiovascular disease.

The results of the Amarin study, announced in a press release, are slated for presentation at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in November.

House, Senate agree on broad opioid legislation

Leaders in the House and the Senate have agreed to a final legislative package to address the opioid crisis.

The consensus legislation, called the Substance Use–Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (H.R. 6), combines a House bill of the same name passed in June with the Opioid Crisis Response Act (S. 2680), passed by the Senate by a 99-1 vote on Sept. 17.

A number of provisions would affect medical practice directly, by:

- Allowing Medicare to pay clinicians to provide substance-use disorder treatment via telemedicine.

- Adding to the Welcome to Medicare exam as well as the annual physical a review of beneficiary’s opioid prescriptions, screening for potential abuse, and referral to appropriate treatment services, if necessary.

- Requiring controlled substance prescriptions covered by Part D to be transmitted electronically beginning Jan. 1, 2021.

- Allowing physicians who recently graduated in good standing from an accredited school and who have appropriate training to prescribe medication-assisted therapy.

- Requiring CMS to notify prescribers if they are identified as statistical outliers when it comes to prescribing opioids, as compared with their peers.

“The bill will make a real difference in Medicare, a program in which one in three beneficiaries is prescribed an opioid,” Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) said Sept .17 during Senate floor debate.

“It will empower patients through information on pain treatment alternatives. It will expand treatment options for patients suffering from addiction, including through increased access to care via telehealth,” he said. “The bill also increases the ability to track opioid prescriptions to prevent misuse and diversion, while also ensuring that beneficiaries promptly get the medications they need.”

The bill also requires the Food and Drug Administration to issue guidance on expedited pathways for approval of new nonaddictive pain treatments and on the appropriate use of pain endpoints across agency divisions as well as clarification on requirements on how opioid-sparing data is to be used on labels.

The combined legislation also clarifies the FDA’s authority to require drug manufacturers to package opioids in three- and seven-supply blister packs, as well as requiring manufacturers to provide patients with simple and safe options to dispose of unused opioids.

The combined bill addresses one of the criticisms of the Senate-passed version.

Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) noted the absence of a provision that would have given nurse practitioners and physician assistants permanent prescribing authority for medication-assisted therapies.

“This is a missed opportunity to build upon our commitment to treatment,” he said on the Senate floor.

The final version of H.R. 6 that will be voted on by both chambers includes the House-passed provision.

At press time, votes on the combined bill had not been scheduled.

Sen. Margaret Wood Hassan (D-N.H.) warned the Congress not to get complacent.

“This legislation is a vital next step in our efforts to combat this crisis,” she said. “The biggest mistake anyone could make is thinking that our efforts are anywhere close to being done.”

A section-by-section summary of the bill can be found here.

Leaders in the House and the Senate have agreed to a final legislative package to address the opioid crisis.

The consensus legislation, called the Substance Use–Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (H.R. 6), combines a House bill of the same name passed in June with the Opioid Crisis Response Act (S. 2680), passed by the Senate by a 99-1 vote on Sept. 17.

A number of provisions would affect medical practice directly, by:

- Allowing Medicare to pay clinicians to provide substance-use disorder treatment via telemedicine.

- Adding to the Welcome to Medicare exam as well as the annual physical a review of beneficiary’s opioid prescriptions, screening for potential abuse, and referral to appropriate treatment services, if necessary.

- Requiring controlled substance prescriptions covered by Part D to be transmitted electronically beginning Jan. 1, 2021.

- Allowing physicians who recently graduated in good standing from an accredited school and who have appropriate training to prescribe medication-assisted therapy.

- Requiring CMS to notify prescribers if they are identified as statistical outliers when it comes to prescribing opioids, as compared with their peers.

“The bill will make a real difference in Medicare, a program in which one in three beneficiaries is prescribed an opioid,” Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) said Sept .17 during Senate floor debate.

“It will empower patients through information on pain treatment alternatives. It will expand treatment options for patients suffering from addiction, including through increased access to care via telehealth,” he said. “The bill also increases the ability to track opioid prescriptions to prevent misuse and diversion, while also ensuring that beneficiaries promptly get the medications they need.”

The bill also requires the Food and Drug Administration to issue guidance on expedited pathways for approval of new nonaddictive pain treatments and on the appropriate use of pain endpoints across agency divisions as well as clarification on requirements on how opioid-sparing data is to be used on labels.

The combined legislation also clarifies the FDA’s authority to require drug manufacturers to package opioids in three- and seven-supply blister packs, as well as requiring manufacturers to provide patients with simple and safe options to dispose of unused opioids.

The combined bill addresses one of the criticisms of the Senate-passed version.

Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) noted the absence of a provision that would have given nurse practitioners and physician assistants permanent prescribing authority for medication-assisted therapies.

“This is a missed opportunity to build upon our commitment to treatment,” he said on the Senate floor.

The final version of H.R. 6 that will be voted on by both chambers includes the House-passed provision.

At press time, votes on the combined bill had not been scheduled.

Sen. Margaret Wood Hassan (D-N.H.) warned the Congress not to get complacent.

“This legislation is a vital next step in our efforts to combat this crisis,” she said. “The biggest mistake anyone could make is thinking that our efforts are anywhere close to being done.”

A section-by-section summary of the bill can be found here.

Leaders in the House and the Senate have agreed to a final legislative package to address the opioid crisis.

The consensus legislation, called the Substance Use–Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (H.R. 6), combines a House bill of the same name passed in June with the Opioid Crisis Response Act (S. 2680), passed by the Senate by a 99-1 vote on Sept. 17.

A number of provisions would affect medical practice directly, by:

- Allowing Medicare to pay clinicians to provide substance-use disorder treatment via telemedicine.

- Adding to the Welcome to Medicare exam as well as the annual physical a review of beneficiary’s opioid prescriptions, screening for potential abuse, and referral to appropriate treatment services, if necessary.

- Requiring controlled substance prescriptions covered by Part D to be transmitted electronically beginning Jan. 1, 2021.

- Allowing physicians who recently graduated in good standing from an accredited school and who have appropriate training to prescribe medication-assisted therapy.

- Requiring CMS to notify prescribers if they are identified as statistical outliers when it comes to prescribing opioids, as compared with their peers.

“The bill will make a real difference in Medicare, a program in which one in three beneficiaries is prescribed an opioid,” Senate Finance Committee Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) said Sept .17 during Senate floor debate.

“It will empower patients through information on pain treatment alternatives. It will expand treatment options for patients suffering from addiction, including through increased access to care via telehealth,” he said. “The bill also increases the ability to track opioid prescriptions to prevent misuse and diversion, while also ensuring that beneficiaries promptly get the medications they need.”

The bill also requires the Food and Drug Administration to issue guidance on expedited pathways for approval of new nonaddictive pain treatments and on the appropriate use of pain endpoints across agency divisions as well as clarification on requirements on how opioid-sparing data is to be used on labels.

The combined legislation also clarifies the FDA’s authority to require drug manufacturers to package opioids in three- and seven-supply blister packs, as well as requiring manufacturers to provide patients with simple and safe options to dispose of unused opioids.

The combined bill addresses one of the criticisms of the Senate-passed version.

Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) noted the absence of a provision that would have given nurse practitioners and physician assistants permanent prescribing authority for medication-assisted therapies.

“This is a missed opportunity to build upon our commitment to treatment,” he said on the Senate floor.

The final version of H.R. 6 that will be voted on by both chambers includes the House-passed provision.

At press time, votes on the combined bill had not been scheduled.

Sen. Margaret Wood Hassan (D-N.H.) warned the Congress not to get complacent.

“This legislation is a vital next step in our efforts to combat this crisis,” she said. “The biggest mistake anyone could make is thinking that our efforts are anywhere close to being done.”

A section-by-section summary of the bill can be found here.

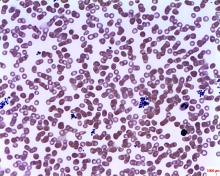

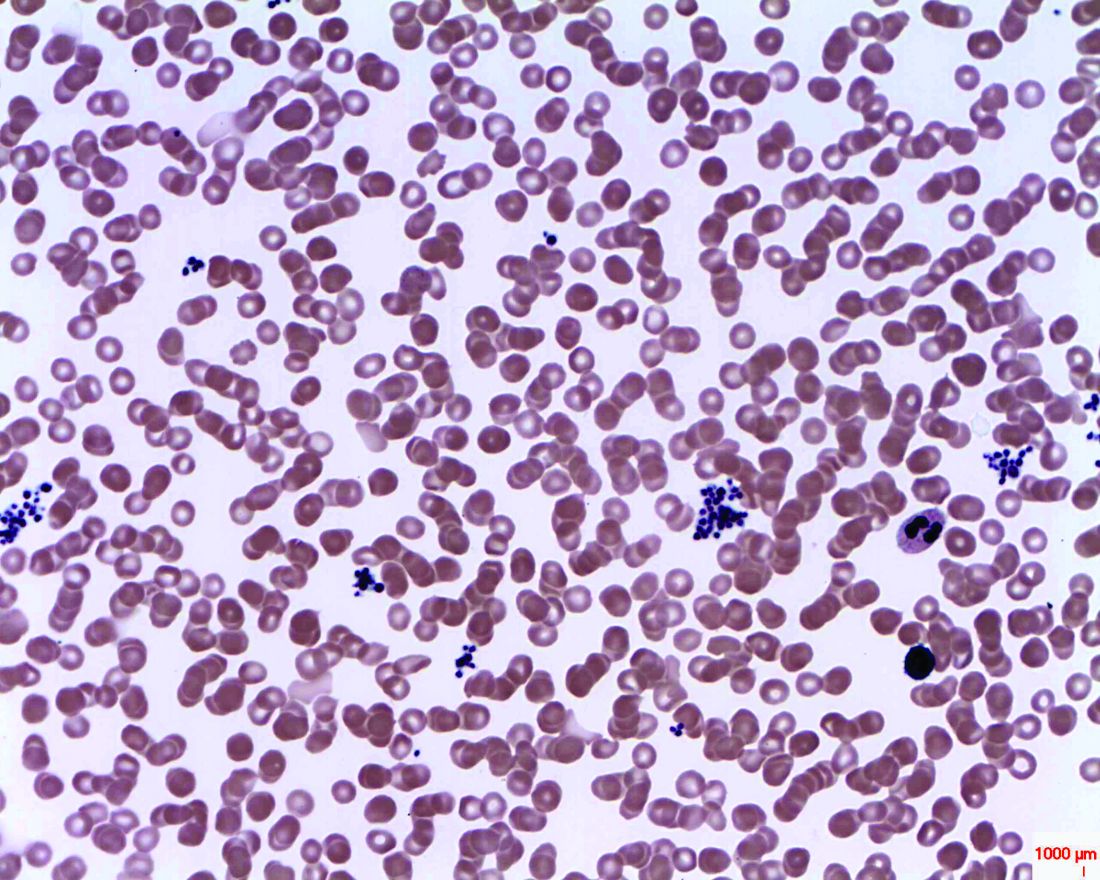

Arginine deficiency implicated in novel hemorrhagic fever fatality

Deficiency of the amino acid arginine is implicated in the low platelet counts of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), and a measure of global arginine bioavailability had prognostic value for mortality from the causal bunyavirus, according to a metabolomics analysis of serum from SFTS patients.

The new study also reported results from a randomized, controlled trial of intravenous arginine supplementation in SFTS; the 53 patients who received 20 g of arginine once daily had faster viral clearance than the 60 patients who received supportive care only and a placebo infusion (P = .047). Also, SFTS patients who received arginine had quicker resolution of liver transaminase elevations (P = .001).

There was no survival benefit in arginine administration, though the study’s first author, Xiao-Kun Li, MD, and colleagues noted low overall fatality rates in arginine-treated and placebo groups, at 5.7% and 8.3%, respectively.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome is caused by a bunyavirus first identified in 2009; SFTS is being seen with increasing frequency in mainland China, Korea, Japan, and the United States. Infection with the virus “is associated with a wide clinical spectrum, with most of the patients having mild disease but more than 10% developing a fatal outcome,” wrote Dr. Li and the other researchers in Science Translational Medicine.

In the case of individuals with SFTS who fare poorly, previous work had implicated a disordered host immune response leading to severe thrombocytopenia with subsequent bleeding and disseminated intravascular coagulation, said Dr. Li and colleagues. The exact pathogenesis of this mechanism had been unknown, however, so the investigators used a metabolomics analysis on serum samples from prospectively observed SFTS patients. “[W]e determined arginine metabolism to be a key pathway that was involved in the interaction between SFTS [virus] and host response,” they wrote.

In a prospective cohort study that used liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, Dr. Li of the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology and colleagues examined 166 metabolites from 242 clinical samples to perform the metabolomics analysis. Of the SFTS patients in the study, 46 had both acute and convalescent samples that were matched with 46 healthy controls and 46 patients with fever not caused by SFTS. In a separate analysis, a series of samples were drawn from 10 patients who died of SFTS and matched to 10 who survived the infection and 10 healthy controls.

Statistical analyses allowed the investigators to identify metabolomics signatures that were unique for each sample group. Alteration of the arginine metabolism pathway stood out as the most pronounced differentiator in acute SFTS infection and fatality, wrote Dr. Li and coauthors. “By extracting the relative concentrations of arginine-related metabolites along the pathway, we found that arginine RC was significantly reduced in the acute phase of SFTS compared to healthy controls,” they wrote (P less than .001).

Patients who succumbed to SFTS had even lower arginine concentrations than did those who survived; arginine levels climbed during recovery for survivors, but stayed low in serum samples from SFTS fatalities.

There’s a logical mechanism by which arginine could contribute to platelet dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, noted Dr. Li and collaborators: Arginine is a nitric oxide precursor, and this pathway is known to be a potent inhibitor of platelet activation.

Low arginine levels would have the effect of taking the brakes off platelet activation, and the investigators did find increases in platelet-monocyte complexes and platelet apoptosis in SFTS virus infection (P = .007 and P less than .001, respectively), which further suggests “that platelet hyperactivation might contribute to reduced platelet counts in circulation,” they wrote.

Low arginine levels also have the effect of suppressing T-cell activity, and mediators along this pathway were also altered in patients with SFTS, and even more profoundly altered in patients who died of SFTS.

Dr. Li and colleagues probed the metabolomics data to see whether a global arginine bioavailability ratio (GABR), expressed as arginine/(ornithine + citrulline), could be used to prognosticate clinical outcome in SFTS virus infection. After multivariable analysis, they found that decreased GABR was associated with fatality (P = .039). Further, a low GABR early in infection was prognostic of later fatality, with an area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) of 0.713.

In the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of arginine supplementation during SFTS, Dr. Li and coinvestigators found that arginine supplementation did not significantly alter most other laboratory values besides liver transaminases. However, blood urea nitrogen concentration was elevated in those who received arginine, and arginine supplementation was also associated with slightly more vomiting. Serum sampling also revealed that platelet activation and T-cell activity were both corrected in patients given arginine, which gives clues to the means by which arginine supplementation might boost host immune response and promote viral clearing and return to homeostasis of clotting pathways.

Limitations of the clinical trial included relatively small sample sizes and the fact that individuals with severe bleeding were excluded from participation in the trial. Also, the study didn’t account for dietary arginine intake, acknowledged Dr. Li and coauthors.

However, the metabolomics and clinical work taken together used state-of-the-art analytic methods and rigorous experimental design to show “the causal relationship between arginine deficiency and platelet deprivation or immunosuppression by SFTSV infection,” wrote Dr. Li and colleagues.

Disturbance in the arginine–nitric oxide pathway is likely “to be a key biochemical pathway that also plays [a] part in other viral hemorrhagic fever,” said the investigators. “The potential of arginine in treating such infectious diseases [with] similar clinical features as SFTS warrants exploration.”

The study was partially funded by a Bayer Investigator Award; Dr. Li and coauthors reported no other conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Li X-K et al. Sci Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4162.

Deficiency of the amino acid arginine is implicated in the low platelet counts of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), and a measure of global arginine bioavailability had prognostic value for mortality from the causal bunyavirus, according to a metabolomics analysis of serum from SFTS patients.

The new study also reported results from a randomized, controlled trial of intravenous arginine supplementation in SFTS; the 53 patients who received 20 g of arginine once daily had faster viral clearance than the 60 patients who received supportive care only and a placebo infusion (P = .047). Also, SFTS patients who received arginine had quicker resolution of liver transaminase elevations (P = .001).

There was no survival benefit in arginine administration, though the study’s first author, Xiao-Kun Li, MD, and colleagues noted low overall fatality rates in arginine-treated and placebo groups, at 5.7% and 8.3%, respectively.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome is caused by a bunyavirus first identified in 2009; SFTS is being seen with increasing frequency in mainland China, Korea, Japan, and the United States. Infection with the virus “is associated with a wide clinical spectrum, with most of the patients having mild disease but more than 10% developing a fatal outcome,” wrote Dr. Li and the other researchers in Science Translational Medicine.

In the case of individuals with SFTS who fare poorly, previous work had implicated a disordered host immune response leading to severe thrombocytopenia with subsequent bleeding and disseminated intravascular coagulation, said Dr. Li and colleagues. The exact pathogenesis of this mechanism had been unknown, however, so the investigators used a metabolomics analysis on serum samples from prospectively observed SFTS patients. “[W]e determined arginine metabolism to be a key pathway that was involved in the interaction between SFTS [virus] and host response,” they wrote.

In a prospective cohort study that used liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, Dr. Li of the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology and colleagues examined 166 metabolites from 242 clinical samples to perform the metabolomics analysis. Of the SFTS patients in the study, 46 had both acute and convalescent samples that were matched with 46 healthy controls and 46 patients with fever not caused by SFTS. In a separate analysis, a series of samples were drawn from 10 patients who died of SFTS and matched to 10 who survived the infection and 10 healthy controls.

Statistical analyses allowed the investigators to identify metabolomics signatures that were unique for each sample group. Alteration of the arginine metabolism pathway stood out as the most pronounced differentiator in acute SFTS infection and fatality, wrote Dr. Li and coauthors. “By extracting the relative concentrations of arginine-related metabolites along the pathway, we found that arginine RC was significantly reduced in the acute phase of SFTS compared to healthy controls,” they wrote (P less than .001).

Patients who succumbed to SFTS had even lower arginine concentrations than did those who survived; arginine levels climbed during recovery for survivors, but stayed low in serum samples from SFTS fatalities.

There’s a logical mechanism by which arginine could contribute to platelet dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, noted Dr. Li and collaborators: Arginine is a nitric oxide precursor, and this pathway is known to be a potent inhibitor of platelet activation.

Low arginine levels would have the effect of taking the brakes off platelet activation, and the investigators did find increases in platelet-monocyte complexes and platelet apoptosis in SFTS virus infection (P = .007 and P less than .001, respectively), which further suggests “that platelet hyperactivation might contribute to reduced platelet counts in circulation,” they wrote.

Low arginine levels also have the effect of suppressing T-cell activity, and mediators along this pathway were also altered in patients with SFTS, and even more profoundly altered in patients who died of SFTS.

Dr. Li and colleagues probed the metabolomics data to see whether a global arginine bioavailability ratio (GABR), expressed as arginine/(ornithine + citrulline), could be used to prognosticate clinical outcome in SFTS virus infection. After multivariable analysis, they found that decreased GABR was associated with fatality (P = .039). Further, a low GABR early in infection was prognostic of later fatality, with an area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) of 0.713.

In the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of arginine supplementation during SFTS, Dr. Li and coinvestigators found that arginine supplementation did not significantly alter most other laboratory values besides liver transaminases. However, blood urea nitrogen concentration was elevated in those who received arginine, and arginine supplementation was also associated with slightly more vomiting. Serum sampling also revealed that platelet activation and T-cell activity were both corrected in patients given arginine, which gives clues to the means by which arginine supplementation might boost host immune response and promote viral clearing and return to homeostasis of clotting pathways.

Limitations of the clinical trial included relatively small sample sizes and the fact that individuals with severe bleeding were excluded from participation in the trial. Also, the study didn’t account for dietary arginine intake, acknowledged Dr. Li and coauthors.

However, the metabolomics and clinical work taken together used state-of-the-art analytic methods and rigorous experimental design to show “the causal relationship between arginine deficiency and platelet deprivation or immunosuppression by SFTSV infection,” wrote Dr. Li and colleagues.

Disturbance in the arginine–nitric oxide pathway is likely “to be a key biochemical pathway that also plays [a] part in other viral hemorrhagic fever,” said the investigators. “The potential of arginine in treating such infectious diseases [with] similar clinical features as SFTS warrants exploration.”

The study was partially funded by a Bayer Investigator Award; Dr. Li and coauthors reported no other conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Li X-K et al. Sci Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4162.

Deficiency of the amino acid arginine is implicated in the low platelet counts of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), and a measure of global arginine bioavailability had prognostic value for mortality from the causal bunyavirus, according to a metabolomics analysis of serum from SFTS patients.

The new study also reported results from a randomized, controlled trial of intravenous arginine supplementation in SFTS; the 53 patients who received 20 g of arginine once daily had faster viral clearance than the 60 patients who received supportive care only and a placebo infusion (P = .047). Also, SFTS patients who received arginine had quicker resolution of liver transaminase elevations (P = .001).

There was no survival benefit in arginine administration, though the study’s first author, Xiao-Kun Li, MD, and colleagues noted low overall fatality rates in arginine-treated and placebo groups, at 5.7% and 8.3%, respectively.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome is caused by a bunyavirus first identified in 2009; SFTS is being seen with increasing frequency in mainland China, Korea, Japan, and the United States. Infection with the virus “is associated with a wide clinical spectrum, with most of the patients having mild disease but more than 10% developing a fatal outcome,” wrote Dr. Li and the other researchers in Science Translational Medicine.

In the case of individuals with SFTS who fare poorly, previous work had implicated a disordered host immune response leading to severe thrombocytopenia with subsequent bleeding and disseminated intravascular coagulation, said Dr. Li and colleagues. The exact pathogenesis of this mechanism had been unknown, however, so the investigators used a metabolomics analysis on serum samples from prospectively observed SFTS patients. “[W]e determined arginine metabolism to be a key pathway that was involved in the interaction between SFTS [virus] and host response,” they wrote.

In a prospective cohort study that used liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, Dr. Li of the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology and colleagues examined 166 metabolites from 242 clinical samples to perform the metabolomics analysis. Of the SFTS patients in the study, 46 had both acute and convalescent samples that were matched with 46 healthy controls and 46 patients with fever not caused by SFTS. In a separate analysis, a series of samples were drawn from 10 patients who died of SFTS and matched to 10 who survived the infection and 10 healthy controls.

Statistical analyses allowed the investigators to identify metabolomics signatures that were unique for each sample group. Alteration of the arginine metabolism pathway stood out as the most pronounced differentiator in acute SFTS infection and fatality, wrote Dr. Li and coauthors. “By extracting the relative concentrations of arginine-related metabolites along the pathway, we found that arginine RC was significantly reduced in the acute phase of SFTS compared to healthy controls,” they wrote (P less than .001).

Patients who succumbed to SFTS had even lower arginine concentrations than did those who survived; arginine levels climbed during recovery for survivors, but stayed low in serum samples from SFTS fatalities.

There’s a logical mechanism by which arginine could contribute to platelet dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, noted Dr. Li and collaborators: Arginine is a nitric oxide precursor, and this pathway is known to be a potent inhibitor of platelet activation.

Low arginine levels would have the effect of taking the brakes off platelet activation, and the investigators did find increases in platelet-monocyte complexes and platelet apoptosis in SFTS virus infection (P = .007 and P less than .001, respectively), which further suggests “that platelet hyperactivation might contribute to reduced platelet counts in circulation,” they wrote.

Low arginine levels also have the effect of suppressing T-cell activity, and mediators along this pathway were also altered in patients with SFTS, and even more profoundly altered in patients who died of SFTS.

Dr. Li and colleagues probed the metabolomics data to see whether a global arginine bioavailability ratio (GABR), expressed as arginine/(ornithine + citrulline), could be used to prognosticate clinical outcome in SFTS virus infection. After multivariable analysis, they found that decreased GABR was associated with fatality (P = .039). Further, a low GABR early in infection was prognostic of later fatality, with an area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) of 0.713.

In the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of arginine supplementation during SFTS, Dr. Li and coinvestigators found that arginine supplementation did not significantly alter most other laboratory values besides liver transaminases. However, blood urea nitrogen concentration was elevated in those who received arginine, and arginine supplementation was also associated with slightly more vomiting. Serum sampling also revealed that platelet activation and T-cell activity were both corrected in patients given arginine, which gives clues to the means by which arginine supplementation might boost host immune response and promote viral clearing and return to homeostasis of clotting pathways.

Limitations of the clinical trial included relatively small sample sizes and the fact that individuals with severe bleeding were excluded from participation in the trial. Also, the study didn’t account for dietary arginine intake, acknowledged Dr. Li and coauthors.

However, the metabolomics and clinical work taken together used state-of-the-art analytic methods and rigorous experimental design to show “the causal relationship between arginine deficiency and platelet deprivation or immunosuppression by SFTSV infection,” wrote Dr. Li and colleagues.

Disturbance in the arginine–nitric oxide pathway is likely “to be a key biochemical pathway that also plays [a] part in other viral hemorrhagic fever,” said the investigators. “The potential of arginine in treating such infectious diseases [with] similar clinical features as SFTS warrants exploration.”

The study was partially funded by a Bayer Investigator Award; Dr. Li and coauthors reported no other conflicts of interest.

koakes@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Li X-K et al. Sci Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4162.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Low arginine bioavailability was associated with increased risk for severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) fatality.

Major finding: Arginine bioavailability had an area under the receiver operating curve of 0.713 for predicting fatality.

Study details: A prospective cohort metabolomics study of 242 serum samples from patients with and without SFTS and a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of 113 patients given intravenous arginine supplementation or vehicle alone, in conjunction with supportive care.

Disclosures: The study was partially funded by a Bayer Investigator Award; Dr. Li and coauthors reported no other conflicts of interest.

Source: Li X-K et al. Sci Transl Med. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat4162.

How Many Patients Have Benign MS?

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

Patients and physicians interpret the term differently, thus making its use in the clinical setting problematic.

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

An estimated 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) have a benign course of disease, according to findings from a population-based UK study published online ahead of print September 3 in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. The term “benign MS” remains problematic, however.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” said Emma Clare Tallantyre, BMBS, PhD, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Neurosciences at Cardiff University in the UK, and her colleagues.

The investigators found that of 1,049 patients with a disease duration of longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those patients, 60 were clinically assessed, and nine (15%) had benign MS, which was defined as an EDSS score less than 3.0 and lack of significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, and disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at at least 15 years after symptom onset.

Extrapolating these data, the investigators estimated that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had benign MS, yielding a prevalence of 2.9%. Of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS, based on the following definition: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications, and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” said the investigators.

—Jeff Evans

Suggested Reading

Tallantyre EC, Major PC, Atherton MJ, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Methadone may shorten NICU stays for neonatal abstinence syndrome

Lengths of stay in the hospital and in the neonatal ICU (NICU) for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) were significantly shorter with methadone treatment, compared with morphine treatment, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Veeral N. Tolia, MD, of Baylor University in Dallas, and his associates, gathered data from NICUs participating in the Clinical Data Warehouse and identified 7,667 singleton infants with no congenital abnormalities treated for NAS with either methadone (15%) or morphine (85%) in the first 7 days of life during 2011-2015.

The median hospital length of stay (LOS) was 18 days (interquartile range, 11-30 days) for infants treated with methadone and 23 days (IQR, 16-33 days) for those treated with morphine (P less than .001). The methadone-treated infants also had a shorter median LOS in the NICU than did the morphine-treated infants: 17 days (IQR, 10-29 days) versus 21 days (IQR, 14-36 days; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis, methadone treatment still was associated with a significantly shorter LOS in both cases. The methadone-treated infants also were significantly less likely to require two medications or three or more medications, compared with the morphine treated infants.

Although there was only a modest difference in LOS, Dr. Tolia and associates consider their findings relevant to clinical practice and are important given that “NAS incidence continues to rise and accounts for a substantial portion of health care utilization, including a fourfold increase in the proportion of neonatal hospital costs of all births covered by Medicaid.”

One of the strengths of this study is the size of its cohort; among its weaknesses is that the Clinical Data Warehouse does not include information on symptom severity, indication for starting therapy, or weaning practices.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tolia VN et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.061.

Lengths of stay in the hospital and in the neonatal ICU (NICU) for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) were significantly shorter with methadone treatment, compared with morphine treatment, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Veeral N. Tolia, MD, of Baylor University in Dallas, and his associates, gathered data from NICUs participating in the Clinical Data Warehouse and identified 7,667 singleton infants with no congenital abnormalities treated for NAS with either methadone (15%) or morphine (85%) in the first 7 days of life during 2011-2015.

The median hospital length of stay (LOS) was 18 days (interquartile range, 11-30 days) for infants treated with methadone and 23 days (IQR, 16-33 days) for those treated with morphine (P less than .001). The methadone-treated infants also had a shorter median LOS in the NICU than did the morphine-treated infants: 17 days (IQR, 10-29 days) versus 21 days (IQR, 14-36 days; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis, methadone treatment still was associated with a significantly shorter LOS in both cases. The methadone-treated infants also were significantly less likely to require two medications or three or more medications, compared with the morphine treated infants.

Although there was only a modest difference in LOS, Dr. Tolia and associates consider their findings relevant to clinical practice and are important given that “NAS incidence continues to rise and accounts for a substantial portion of health care utilization, including a fourfold increase in the proportion of neonatal hospital costs of all births covered by Medicaid.”

One of the strengths of this study is the size of its cohort; among its weaknesses is that the Clinical Data Warehouse does not include information on symptom severity, indication for starting therapy, or weaning practices.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tolia VN et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.061.

Lengths of stay in the hospital and in the neonatal ICU (NICU) for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) were significantly shorter with methadone treatment, compared with morphine treatment, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Veeral N. Tolia, MD, of Baylor University in Dallas, and his associates, gathered data from NICUs participating in the Clinical Data Warehouse and identified 7,667 singleton infants with no congenital abnormalities treated for NAS with either methadone (15%) or morphine (85%) in the first 7 days of life during 2011-2015.

The median hospital length of stay (LOS) was 18 days (interquartile range, 11-30 days) for infants treated with methadone and 23 days (IQR, 16-33 days) for those treated with morphine (P less than .001). The methadone-treated infants also had a shorter median LOS in the NICU than did the morphine-treated infants: 17 days (IQR, 10-29 days) versus 21 days (IQR, 14-36 days; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis, methadone treatment still was associated with a significantly shorter LOS in both cases. The methadone-treated infants also were significantly less likely to require two medications or three or more medications, compared with the morphine treated infants.

Although there was only a modest difference in LOS, Dr. Tolia and associates consider their findings relevant to clinical practice and are important given that “NAS incidence continues to rise and accounts for a substantial portion of health care utilization, including a fourfold increase in the proportion of neonatal hospital costs of all births covered by Medicaid.”

One of the strengths of this study is the size of its cohort; among its weaknesses is that the Clinical Data Warehouse does not include information on symptom severity, indication for starting therapy, or weaning practices.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tolia VN et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.061.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

A new era arrives in alopecia areata therapy

PARIS – Each of two oral Janus kinase inhibitors individually showed impressive efficacy and acceptable safety and tolerability for treatment of chronic moderate to severe alopecia areata in a phase 2 study that promises to alter the therapeutic landscape in this challenging disease, Rodney Sinclair, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“My personal view is that these results represent a paradigm shift in the treatment of alopecia areata. Perhaps a line in the sand. On the one side, clinical observation, case reports, and small case series, but no reliably effective treatment. And on the other side of the line, investigational new drugs specifically targeting the pathogenesis, tested in prospective, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies – and perhaps the first instance of evidence-based medicine arriving for alopecia areata. And I think that our patients with alopecia areata now have reason to be optimistic,” the dermatologist said.

“No reliably effective therapies now exist for alopecia areata, especially for patients with chronic extensive disease. There is an unmet need for a reliably effective therapy with a benefit-to-risk ratio that is appropriate for long-term use,” he added.

The phase 2 multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind study randomized 142 patients with chronic alopecia of at least 6 months duration and 50% or greater hair loss at baseline to an , or placebo for 24 weeks. The first 4 weeks of the double-blind trial involved induction dosing of the JAK3 inhibitor at 200 mg per day and the TYK2/JAK 1 inhibitor at 60 mg per day. Thereafter, participants switched to maintenance dosing at 50 mg and 30 mg per day, respectively.

Participants had a median 2.3 years of disease duration; 62 patients had alopecia totalis, and 42 had alopecia universalis.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the mean change from baseline to week 24 in the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score, a well-validated metric widely utilized in hair loss studies. The mean baseline score was 88.1. At week 24, the score had dropped by a mean of 33.6% in the JAK 3 inhibitor group, 49.5% in the TYK2/JAK1 inhibitor group, and zero in placebo-treated controls.

A key secondary endpoint known as the SALT 30, reflecting at least 30% improvement in SALT score, was achieved in 47.9% of patients on the oral JAK 3 inhibitor, 59.6% of those on the TYK2/JAK1 inhibitor, and by no one in the control group. The utter unresponsiveness of placebo-treated controls confirms the investigators’ success in recruiting a study population with truly chronic alopecia areata, Dr. Sinclair noted.

Of note, 25% of patients on the JAK 3 inhibitor and 31.9% on the TYK2/JAK1 inhibitor achieved a SALT 90 response, and 12.5% and 12.8% reached SALT 100.

Significant improvement on the Eyelash Assessment and Eyebrow Assessment Scales occurred in 45.2% and 36.2% of the JAK 3 inhibitor group and in 60.7% and 51.7% of the TYK2/JAK 1 inhibitor group.

The study is ongoing. It’s Dr. Sinclair’s anecdotal impression that further improvement is occurring in the active treatment arms with continued therapy after 24 weeks, but that remains to be seen.

Adverse events were similar in nature and frequency in all three study arms with one notable exception: two cases of rhabdomyolysis in the TYK2/JAK 1 inhibitor group.Session chair DeDee Murrell, MD, homed in on that piece of information, pressing for further details.

“Are you concerned? Were there predictors?” asked Dr. Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

The two affected patients had muscle pain and elevated creatinine kinase levels. “They didn’t feel particularly unwell but were withdrawn as a precaution, after which the condition quickly resolved,” Dr. Sinclair said.

The investigators were unable to identify any risk factors for rhabdomyolysis in the study population, he added.

Dr. Sinclair reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to Pfizer, which sponsored the phase 2 study, as well as more than a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

PARIS – Each of two oral Janus kinase inhibitors individually showed impressive efficacy and acceptable safety and tolerability for treatment of chronic moderate to severe alopecia areata in a phase 2 study that promises to alter the therapeutic landscape in this challenging disease, Rodney Sinclair, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“My personal view is that these results represent a paradigm shift in the treatment of alopecia areata. Perhaps a line in the sand. On the one side, clinical observation, case reports, and small case series, but no reliably effective treatment. And on the other side of the line, investigational new drugs specifically targeting the pathogenesis, tested in prospective, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies – and perhaps the first instance of evidence-based medicine arriving for alopecia areata. And I think that our patients with alopecia areata now have reason to be optimistic,” the dermatologist said.

“No reliably effective therapies now exist for alopecia areata, especially for patients with chronic extensive disease. There is an unmet need for a reliably effective therapy with a benefit-to-risk ratio that is appropriate for long-term use,” he added.