User login

A new antiemetic

Clinical question: Can aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol confer an adjunctive and lasting benefit as an antiemetic in ED patients who do not otherwise need IV access?

Background: Prior studies have shown a benefit of aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol for postoperative nausea and vomiting, and it is both widely available and safe. Only one randomized, controlled study exists documenting use of aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol in the ED, but this monitored for effects for only 10 minutes and did not compare it with other antiemetic therapies used in the emergency department.

Study design: Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Single urban tertiary care center emergency department.

Synopsis: The study separated 120 patients with nausea who did not otherwise need intravenous access into three treatment groups. They were assessed for improvement in nausea using a visual analog scale 30 minutes after administration of either oral ondansetron 4 mg and inhaled isopropyl alcohol, oral placebo and inhaled isopropyl alcohol, or oral ondansetron and inhaled saline. The mean decrease in nausea visual analog scale score was 30 mm (95% confidence interval, 22-37 mm), 32 mm (95% CI, 25-39 mm), and 9 mm (95% CI, 5-14 mm), respectively. The need for rescue antiemetics was 27.5%, 25%, and 45%, respectively. This study is limited by its small size, its relatively healthy population with a predominant diagnosis of gastroenteritis, and that patients who required IV catheters were excluded; therefore, it may not be generalizable to sicker patients with alternative etiologies for nausea. Furthermore, many patients were able to distinguish isopropyl alcohol from placebo inhalant by smell so the blinding was possibly ineffective. However, since isopropyl alcohol is low risk, inexpensive, and readily available, it may be reasonable to consider this as a therapeutic option for some patients.

Bottom line: In ED patients who did not otherwise need intravenous access, aromatherapy with inhaled isopropyl alcohol alone or with ondansetron was superior for nausea relief when compared with ondansetron alone.

Citation: April MD et al. Aromatherapy versus oral ondansetron for antiemetic therapy among adult emergency department patients: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.01.016.

Dr. Sayers is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Clinical question: Can aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol confer an adjunctive and lasting benefit as an antiemetic in ED patients who do not otherwise need IV access?

Background: Prior studies have shown a benefit of aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol for postoperative nausea and vomiting, and it is both widely available and safe. Only one randomized, controlled study exists documenting use of aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol in the ED, but this monitored for effects for only 10 minutes and did not compare it with other antiemetic therapies used in the emergency department.

Study design: Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Single urban tertiary care center emergency department.

Synopsis: The study separated 120 patients with nausea who did not otherwise need intravenous access into three treatment groups. They were assessed for improvement in nausea using a visual analog scale 30 minutes after administration of either oral ondansetron 4 mg and inhaled isopropyl alcohol, oral placebo and inhaled isopropyl alcohol, or oral ondansetron and inhaled saline. The mean decrease in nausea visual analog scale score was 30 mm (95% confidence interval, 22-37 mm), 32 mm (95% CI, 25-39 mm), and 9 mm (95% CI, 5-14 mm), respectively. The need for rescue antiemetics was 27.5%, 25%, and 45%, respectively. This study is limited by its small size, its relatively healthy population with a predominant diagnosis of gastroenteritis, and that patients who required IV catheters were excluded; therefore, it may not be generalizable to sicker patients with alternative etiologies for nausea. Furthermore, many patients were able to distinguish isopropyl alcohol from placebo inhalant by smell so the blinding was possibly ineffective. However, since isopropyl alcohol is low risk, inexpensive, and readily available, it may be reasonable to consider this as a therapeutic option for some patients.

Bottom line: In ED patients who did not otherwise need intravenous access, aromatherapy with inhaled isopropyl alcohol alone or with ondansetron was superior for nausea relief when compared with ondansetron alone.

Citation: April MD et al. Aromatherapy versus oral ondansetron for antiemetic therapy among adult emergency department patients: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.01.016.

Dr. Sayers is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Clinical question: Can aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol confer an adjunctive and lasting benefit as an antiemetic in ED patients who do not otherwise need IV access?

Background: Prior studies have shown a benefit of aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol for postoperative nausea and vomiting, and it is both widely available and safe. Only one randomized, controlled study exists documenting use of aromatherapy with isopropyl alcohol in the ED, but this monitored for effects for only 10 minutes and did not compare it with other antiemetic therapies used in the emergency department.

Study design: Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Single urban tertiary care center emergency department.

Synopsis: The study separated 120 patients with nausea who did not otherwise need intravenous access into three treatment groups. They were assessed for improvement in nausea using a visual analog scale 30 minutes after administration of either oral ondansetron 4 mg and inhaled isopropyl alcohol, oral placebo and inhaled isopropyl alcohol, or oral ondansetron and inhaled saline. The mean decrease in nausea visual analog scale score was 30 mm (95% confidence interval, 22-37 mm), 32 mm (95% CI, 25-39 mm), and 9 mm (95% CI, 5-14 mm), respectively. The need for rescue antiemetics was 27.5%, 25%, and 45%, respectively. This study is limited by its small size, its relatively healthy population with a predominant diagnosis of gastroenteritis, and that patients who required IV catheters were excluded; therefore, it may not be generalizable to sicker patients with alternative etiologies for nausea. Furthermore, many patients were able to distinguish isopropyl alcohol from placebo inhalant by smell so the blinding was possibly ineffective. However, since isopropyl alcohol is low risk, inexpensive, and readily available, it may be reasonable to consider this as a therapeutic option for some patients.

Bottom line: In ED patients who did not otherwise need intravenous access, aromatherapy with inhaled isopropyl alcohol alone or with ondansetron was superior for nausea relief when compared with ondansetron alone.

Citation: April MD et al. Aromatherapy versus oral ondansetron for antiemetic therapy among adult emergency department patients: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.01.016.

Dr. Sayers is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Childhood-onset SLE has major impact in adult life

The majority of adults with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a longitudinal Dutch study developed significant damage at a young age, remain on corticosteroids in adulthood, and have an impaired health-related quality of life.

The findings in the study, dubbed Childhood-Onset SLE in the Netherlands (CHILL-NL), highlighted the need for preventive screening measures to be put in place before the age of 30 to facilitate a better outcome for patients, who still face high morbidity from childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) despite improved survival. Such information is helpful to “answer questions from children and parents regarding the future course of the disease,” wrote Noortje Groot, PhD, of the department of pediatric rheumatology at Erasmus Medical Center–Sophia Children’s Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues. The report is in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The current study included all adult SLE patients treated in any Dutch public hospital during the period of November 2013 to April 2016 who were diagnosed with the autoimmune disease prior to their 18th birthday.

All 111 patients involved in the study were seen for a 1.5-hour visit at Erasmus University Medical Center or a local hospital of their choice. During the appointment, a medical history was taken, a physical examination was performed, and the patients completed questionnaires on health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

The average age of patients at the study visit was 33 years, 91% were female, and 72% were white. Median disease duration was 20 years and disease activity was low (median SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 [SLEDAI-2k] = 4). Low complement (32%), skin rashes (14%), and proteinuria (13%) were the most common SLEDAI items reported.

Overall, 68% of the cohort (n = 76) were taking hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), 29% of whom (n = 22) were taking it as monotherapy.

Furthermore, 68% of patients at the study visit were taking corticosteroids and/or non-HCQ disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and just over half (51%) of patients (n = 56) were taking corticosteroids either alone or with a non-HCQ DMARD.

“This [finding] is worrying as corticosteroids are associated with the development of damage. Patients are certainly eager to limit corticosteroid use, as almost all patients in the CHILL-NL cohort reported to have negative experiences with prednisone regarding their physical appearance and or mental well-being,” the study authors wrote.

Results also showed that 62% of the patients had damage, predominantly in the musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, and renal systems.

Most organ systems became involved within the first 2 years of diagnosis, but after 5 years of disease the nature of disease manifestations tended to shift to damage such as myocardial infarctions.

Notably, after 10-20 years, when cSLE patients were in their early 20s and 30s, significant damage had occurred in more than half of the patients, the authors noted.

“This shift to damage has also been observed in adult-onset SLE patients and urges for preventative screening measures of such (cardiovascular) damage and healthy lifestyle advice (healthy diet, regular exercise, abstinence from smoking),” they wrote.

Multivariate logistic regression showed that damage accrual was associated with disease duration (odds ratio, 1.15; P less than .001), antiphospholipid‐antibody positivity (OR, 3.56; P = .026), and hypertension (OR, 3.21; P = .043). On the other hand, current HCQ monotherapy was associated with an SLICC-Damage Index score of 0 (OR, 0.16; P = .009).

The HRQOL of the cohort, assessed via the Short Form–36, was also impaired compared with the general population, the researchers discovered. For example, the presence of damage reduced HRQOL in one domain, and high disease activity, defined as SLEDAI-2k of 8 or more, strongly reduced HRQOL in four of eight domains. Changes in physical appearance lowered HRQOL in seven of eight domains.

“HRQOL of adults with cSLE is impaired and affected by other factors than disease activity or damage alone. By identifying and addressing these factors, like physical appearance and potentially coping styles, HRQOL may be improved,” they advised.

The study was supported financially by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Dutch national patient association for lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome, scleroderma, and mixed connective tissue diseases.

SOURCE: Groot N et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Aug 27. doi: 10.1002/art.40697

The majority of adults with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a longitudinal Dutch study developed significant damage at a young age, remain on corticosteroids in adulthood, and have an impaired health-related quality of life.

The findings in the study, dubbed Childhood-Onset SLE in the Netherlands (CHILL-NL), highlighted the need for preventive screening measures to be put in place before the age of 30 to facilitate a better outcome for patients, who still face high morbidity from childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) despite improved survival. Such information is helpful to “answer questions from children and parents regarding the future course of the disease,” wrote Noortje Groot, PhD, of the department of pediatric rheumatology at Erasmus Medical Center–Sophia Children’s Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues. The report is in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The current study included all adult SLE patients treated in any Dutch public hospital during the period of November 2013 to April 2016 who were diagnosed with the autoimmune disease prior to their 18th birthday.

All 111 patients involved in the study were seen for a 1.5-hour visit at Erasmus University Medical Center or a local hospital of their choice. During the appointment, a medical history was taken, a physical examination was performed, and the patients completed questionnaires on health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

The average age of patients at the study visit was 33 years, 91% were female, and 72% were white. Median disease duration was 20 years and disease activity was low (median SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 [SLEDAI-2k] = 4). Low complement (32%), skin rashes (14%), and proteinuria (13%) were the most common SLEDAI items reported.

Overall, 68% of the cohort (n = 76) were taking hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), 29% of whom (n = 22) were taking it as monotherapy.

Furthermore, 68% of patients at the study visit were taking corticosteroids and/or non-HCQ disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and just over half (51%) of patients (n = 56) were taking corticosteroids either alone or with a non-HCQ DMARD.

“This [finding] is worrying as corticosteroids are associated with the development of damage. Patients are certainly eager to limit corticosteroid use, as almost all patients in the CHILL-NL cohort reported to have negative experiences with prednisone regarding their physical appearance and or mental well-being,” the study authors wrote.

Results also showed that 62% of the patients had damage, predominantly in the musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, and renal systems.

Most organ systems became involved within the first 2 years of diagnosis, but after 5 years of disease the nature of disease manifestations tended to shift to damage such as myocardial infarctions.

Notably, after 10-20 years, when cSLE patients were in their early 20s and 30s, significant damage had occurred in more than half of the patients, the authors noted.

“This shift to damage has also been observed in adult-onset SLE patients and urges for preventative screening measures of such (cardiovascular) damage and healthy lifestyle advice (healthy diet, regular exercise, abstinence from smoking),” they wrote.

Multivariate logistic regression showed that damage accrual was associated with disease duration (odds ratio, 1.15; P less than .001), antiphospholipid‐antibody positivity (OR, 3.56; P = .026), and hypertension (OR, 3.21; P = .043). On the other hand, current HCQ monotherapy was associated with an SLICC-Damage Index score of 0 (OR, 0.16; P = .009).

The HRQOL of the cohort, assessed via the Short Form–36, was also impaired compared with the general population, the researchers discovered. For example, the presence of damage reduced HRQOL in one domain, and high disease activity, defined as SLEDAI-2k of 8 or more, strongly reduced HRQOL in four of eight domains. Changes in physical appearance lowered HRQOL in seven of eight domains.

“HRQOL of adults with cSLE is impaired and affected by other factors than disease activity or damage alone. By identifying and addressing these factors, like physical appearance and potentially coping styles, HRQOL may be improved,” they advised.

The study was supported financially by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Dutch national patient association for lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome, scleroderma, and mixed connective tissue diseases.

SOURCE: Groot N et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Aug 27. doi: 10.1002/art.40697

The majority of adults with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a longitudinal Dutch study developed significant damage at a young age, remain on corticosteroids in adulthood, and have an impaired health-related quality of life.

The findings in the study, dubbed Childhood-Onset SLE in the Netherlands (CHILL-NL), highlighted the need for preventive screening measures to be put in place before the age of 30 to facilitate a better outcome for patients, who still face high morbidity from childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) despite improved survival. Such information is helpful to “answer questions from children and parents regarding the future course of the disease,” wrote Noortje Groot, PhD, of the department of pediatric rheumatology at Erasmus Medical Center–Sophia Children’s Hospital in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues. The report is in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The current study included all adult SLE patients treated in any Dutch public hospital during the period of November 2013 to April 2016 who were diagnosed with the autoimmune disease prior to their 18th birthday.

All 111 patients involved in the study were seen for a 1.5-hour visit at Erasmus University Medical Center or a local hospital of their choice. During the appointment, a medical history was taken, a physical examination was performed, and the patients completed questionnaires on health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

The average age of patients at the study visit was 33 years, 91% were female, and 72% were white. Median disease duration was 20 years and disease activity was low (median SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 [SLEDAI-2k] = 4). Low complement (32%), skin rashes (14%), and proteinuria (13%) were the most common SLEDAI items reported.

Overall, 68% of the cohort (n = 76) were taking hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), 29% of whom (n = 22) were taking it as monotherapy.

Furthermore, 68% of patients at the study visit were taking corticosteroids and/or non-HCQ disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and just over half (51%) of patients (n = 56) were taking corticosteroids either alone or with a non-HCQ DMARD.

“This [finding] is worrying as corticosteroids are associated with the development of damage. Patients are certainly eager to limit corticosteroid use, as almost all patients in the CHILL-NL cohort reported to have negative experiences with prednisone regarding their physical appearance and or mental well-being,” the study authors wrote.

Results also showed that 62% of the patients had damage, predominantly in the musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, and renal systems.

Most organ systems became involved within the first 2 years of diagnosis, but after 5 years of disease the nature of disease manifestations tended to shift to damage such as myocardial infarctions.

Notably, after 10-20 years, when cSLE patients were in their early 20s and 30s, significant damage had occurred in more than half of the patients, the authors noted.

“This shift to damage has also been observed in adult-onset SLE patients and urges for preventative screening measures of such (cardiovascular) damage and healthy lifestyle advice (healthy diet, regular exercise, abstinence from smoking),” they wrote.

Multivariate logistic regression showed that damage accrual was associated with disease duration (odds ratio, 1.15; P less than .001), antiphospholipid‐antibody positivity (OR, 3.56; P = .026), and hypertension (OR, 3.21; P = .043). On the other hand, current HCQ monotherapy was associated with an SLICC-Damage Index score of 0 (OR, 0.16; P = .009).

The HRQOL of the cohort, assessed via the Short Form–36, was also impaired compared with the general population, the researchers discovered. For example, the presence of damage reduced HRQOL in one domain, and high disease activity, defined as SLEDAI-2k of 8 or more, strongly reduced HRQOL in four of eight domains. Changes in physical appearance lowered HRQOL in seven of eight domains.

“HRQOL of adults with cSLE is impaired and affected by other factors than disease activity or damage alone. By identifying and addressing these factors, like physical appearance and potentially coping styles, HRQOL may be improved,” they advised.

The study was supported financially by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Dutch national patient association for lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome, scleroderma, and mixed connective tissue diseases.

SOURCE: Groot N et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Aug 27. doi: 10.1002/art.40697

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among 111 patients, 62% had damage, predominantly in the musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, and renal systems.

Study details: Adult SLE patients diagnosed prior to their 18th birthday who were treated during November 2013 to April 2016 in any Dutch public hospital.

Disclosures: The study was supported financially by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Dutch national patient association for lupus, antiphospholipid syndrome, scleroderma, and mixed connective tissue diseases.

Source: Groot N et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Aug 27. doi: 10.1002/art.40697.

Targeting depression, not eating disorders, may yield better results

Decreased quality of life attributed to eating disorder symptoms among college students may in fact be related to comorbid depression, results of a recent analysis suggest.

Depression scores and shape concerns both accounted for significant variance in quality of life scores in the analysis. However, depression scores accounted for nearly 10% of the variance, while shape concerns accounted for less than 1%, according to graduate student Paige J. Trojanowski and associate professor Sarah Fischer, PhD, both of the department of psychology at George Mason University, Fairfax, Va.

“Considering the low base rate of eating disorders, interventions to improve student quality of life that target depression may yield more widespread results than those focused on targeting weight or eating concerns,” Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer reported in Eating Behaviors. Targeting depression might unintentionally improve quality of life in students with disordered eating or body image concerns, they added, noting that depression and eating disorders often are comorbid.

Previous studies looking at relationships between exercise, disordered eating, and quality of life have not included depressive symptoms. Thus, the investigators analyzed the relative impact of depression, eating disorder symptoms, and exercise on Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) scores in a sample of 851 college students (mean age, about 19 years), three-quarters of whom identified as white. Most of the participants were women (n = 676).

Nearly 90% of the students reported some level of physical activity in the past month, with a mean of 885 minutes. Scores on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) ranged from 0 to 57, with 13.5%, 7.4% and 3.4% falling in the mild, moderate, and severe depression ranges, respectively.

A regression model developed as part of the analysis explained 28.9% of the variance in QOLI scores, Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer wrote.

Shape concern was the only symptom on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire that had a significant effect on quality of life (P = .005). In addition, BDI-II scores accounted for significant variance (P less than .001).

However, only 0.77% of the total variance in QOLI scores was accounted for by unique variance in shape concern, while 9.55% was accounted for by unique variance in depressive symptoms, their analysis showed.

“While clinical level eating disorders are present on college campuses and deserve specific attention to reduce their significant negative effect on QOL in those students, these results show that depressive symptoms may have a more significant impact on the quality of life of college students at large,” they wrote.

Exercise frequency was not related to quality of life, after accounting for the contribution of eating disorder symptoms. However, exercising for mood improvement or enjoyment was significantly associated with quality of life, Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer reported. In the final model, identifying as a woman was tied to a lower quality of life.

“Future studies should examine exercising for reasons of enjoyment as a protective factor against decreased QOL in college students,” they wrote.

Limitations cited include the study’s cross-sectional design and the investigators’ reliance on self-report questionnaires.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest or research funding.

SOURCE: Trojanowski PJ et al. Eat Behav. 2018 Aug 18. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.08.005.

Decreased quality of life attributed to eating disorder symptoms among college students may in fact be related to comorbid depression, results of a recent analysis suggest.

Depression scores and shape concerns both accounted for significant variance in quality of life scores in the analysis. However, depression scores accounted for nearly 10% of the variance, while shape concerns accounted for less than 1%, according to graduate student Paige J. Trojanowski and associate professor Sarah Fischer, PhD, both of the department of psychology at George Mason University, Fairfax, Va.

“Considering the low base rate of eating disorders, interventions to improve student quality of life that target depression may yield more widespread results than those focused on targeting weight or eating concerns,” Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer reported in Eating Behaviors. Targeting depression might unintentionally improve quality of life in students with disordered eating or body image concerns, they added, noting that depression and eating disorders often are comorbid.

Previous studies looking at relationships between exercise, disordered eating, and quality of life have not included depressive symptoms. Thus, the investigators analyzed the relative impact of depression, eating disorder symptoms, and exercise on Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) scores in a sample of 851 college students (mean age, about 19 years), three-quarters of whom identified as white. Most of the participants were women (n = 676).

Nearly 90% of the students reported some level of physical activity in the past month, with a mean of 885 minutes. Scores on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) ranged from 0 to 57, with 13.5%, 7.4% and 3.4% falling in the mild, moderate, and severe depression ranges, respectively.

A regression model developed as part of the analysis explained 28.9% of the variance in QOLI scores, Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer wrote.

Shape concern was the only symptom on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire that had a significant effect on quality of life (P = .005). In addition, BDI-II scores accounted for significant variance (P less than .001).

However, only 0.77% of the total variance in QOLI scores was accounted for by unique variance in shape concern, while 9.55% was accounted for by unique variance in depressive symptoms, their analysis showed.

“While clinical level eating disorders are present on college campuses and deserve specific attention to reduce their significant negative effect on QOL in those students, these results show that depressive symptoms may have a more significant impact on the quality of life of college students at large,” they wrote.

Exercise frequency was not related to quality of life, after accounting for the contribution of eating disorder symptoms. However, exercising for mood improvement or enjoyment was significantly associated with quality of life, Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer reported. In the final model, identifying as a woman was tied to a lower quality of life.

“Future studies should examine exercising for reasons of enjoyment as a protective factor against decreased QOL in college students,” they wrote.

Limitations cited include the study’s cross-sectional design and the investigators’ reliance on self-report questionnaires.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest or research funding.

SOURCE: Trojanowski PJ et al. Eat Behav. 2018 Aug 18. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.08.005.

Decreased quality of life attributed to eating disorder symptoms among college students may in fact be related to comorbid depression, results of a recent analysis suggest.

Depression scores and shape concerns both accounted for significant variance in quality of life scores in the analysis. However, depression scores accounted for nearly 10% of the variance, while shape concerns accounted for less than 1%, according to graduate student Paige J. Trojanowski and associate professor Sarah Fischer, PhD, both of the department of psychology at George Mason University, Fairfax, Va.

“Considering the low base rate of eating disorders, interventions to improve student quality of life that target depression may yield more widespread results than those focused on targeting weight or eating concerns,” Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer reported in Eating Behaviors. Targeting depression might unintentionally improve quality of life in students with disordered eating or body image concerns, they added, noting that depression and eating disorders often are comorbid.

Previous studies looking at relationships between exercise, disordered eating, and quality of life have not included depressive symptoms. Thus, the investigators analyzed the relative impact of depression, eating disorder symptoms, and exercise on Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) scores in a sample of 851 college students (mean age, about 19 years), three-quarters of whom identified as white. Most of the participants were women (n = 676).

Nearly 90% of the students reported some level of physical activity in the past month, with a mean of 885 minutes. Scores on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) ranged from 0 to 57, with 13.5%, 7.4% and 3.4% falling in the mild, moderate, and severe depression ranges, respectively.

A regression model developed as part of the analysis explained 28.9% of the variance in QOLI scores, Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer wrote.

Shape concern was the only symptom on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire that had a significant effect on quality of life (P = .005). In addition, BDI-II scores accounted for significant variance (P less than .001).

However, only 0.77% of the total variance in QOLI scores was accounted for by unique variance in shape concern, while 9.55% was accounted for by unique variance in depressive symptoms, their analysis showed.

“While clinical level eating disorders are present on college campuses and deserve specific attention to reduce their significant negative effect on QOL in those students, these results show that depressive symptoms may have a more significant impact on the quality of life of college students at large,” they wrote.

Exercise frequency was not related to quality of life, after accounting for the contribution of eating disorder symptoms. However, exercising for mood improvement or enjoyment was significantly associated with quality of life, Ms. Trojanowski and Dr. Fischer reported. In the final model, identifying as a woman was tied to a lower quality of life.

“Future studies should examine exercising for reasons of enjoyment as a protective factor against decreased QOL in college students,” they wrote.

Limitations cited include the study’s cross-sectional design and the investigators’ reliance on self-report questionnaires.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest or research funding.

SOURCE: Trojanowski PJ et al. Eat Behav. 2018 Aug 18. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.08.005.

FROM EATING BEHAVIORS

Key clinical point: Exercising for mood enjoyment was tied to a greater quality of life.

Major finding: Only 0.77% of total variance in quality of life scores was accounted for by unique variance in shape concern, while 9.55% was accounted for by unique variance in depressive symptoms.

Study details: An analysis of the impact of depression, eating disorders, and exercise on quality of life in a sample of 851 college students.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest or research funding.

Source: Trojanowski PJ et al. Eat Behav. 2018 Aug 18. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.08.005.

Dermatologists continue to prefer urban areas

, according to data from a longitudinal study published online Sept. 5 in JAMA Dermatology.

Data from previous studies suggest that the demand for dermatologists continues to outpace the supply, thus dermatologists have their choice of locations and prefer urban areas because of greater professional opportunities, desire to live near family, and lack of financial incentives to relocate to underserved areas, wrote Hao Feng, MD, of the department of dermatology, New York University, and his colleagues.

To evaluate the latest longitudinal trends in dermatology and factors affecting geographic distribution, the researchers used the Area Health Resources File from 1995 to 2013 to examine the geographic densities of dermatologists and other physicians, as well as the age distribution of dermatologists. The counties were classified as rural, nonmetropolitan, and metropolitan.

Although the percentage changes in dermatologist density at the county level showed a greater increase during the study period in rural counties (30%) and nonmetropolitan counties (25%), compared with metropolitan counties (18%), the differences in actual density of dermatologists per 100,000 people were highest in urban areas.

Overall, dermatologist density in metropolitan areas increased from 3.47 to 4.11 per 100,000 people between 1995 and 2013. Dermatologist density in nonmetropolitan areas during this time increased from 0.84 in 1995 to 1.05 per 100,000 people in 2013, and from 0.065 to 0.085 per 100,000 people in rural areas during that time.

The researchers also evaluated dermatologist trends by age, and found that the number of dermatologists younger than 55 years increased by 21% in metropolitan areas and by 7% in nonmetropolitan and rural areas combined between 1995 and 2013.

The study findings were strengthened by the long time period, but limited by factors including inability to differentiate among full-time and part-time dermatologists, and among medical or cosmetic dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, the researchers said. However, the results suggest that geographic disparities for dermatologists in the United States continue to increase, and strategies to correct it are important to maintain patient care, they wrote. “Careful workforce planning will be needed to consider alternative health care delivery models, dermatologist recruitment strategies, and the role of nonphysician practitioners and telemedicine, especially in nonmetropolitan or rural areas,” they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Feng H et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3022.

A stagnation of dermatology training programs in the 1980s and 1990s led to a limited supply of dermatologists, most of whom chose to work in urban areas, and this geographic distribution gap has persisted and worsened, Martina L. Porter, MD, and Alexa B. Kimball, MD, wrote in an editorial. The trend of more dermatologists opting for academic, group, or multispecialty practices instead of solo practices has continued, which adds to the maldistribution of dermatologists by geography, they said. “This demographic pattern poses an additional threat because almost half of rural dermatology practices were solo practices as of 2014,” they noted.

In addition, women make up approximately half of the current and future dermatology workforce, and they have historically been less likely to move to rural areas, even when offered forgiveness on student loans. Even so, the authors encouraged the use of exposure to rural medicine to establish a connection to an area, along with financial incentives and loan repayment.

“In parallel, because there appears to be increasing willingness to fund telemedicine, doubling down on training rural physicians and APPs in some areas of dermatology and engaging technology to support them seems prudent and responsible,” they wrote. “We may not be able to modify the overall dermatology workforce imbalance, but ensuring timely access to our expertise for those patients who need us most can still be achieved if prioritized correctly” (JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2925).

Dr. Porter and Dr. Kimball are affiliated with Harvard Medical School in Boston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A stagnation of dermatology training programs in the 1980s and 1990s led to a limited supply of dermatologists, most of whom chose to work in urban areas, and this geographic distribution gap has persisted and worsened, Martina L. Porter, MD, and Alexa B. Kimball, MD, wrote in an editorial. The trend of more dermatologists opting for academic, group, or multispecialty practices instead of solo practices has continued, which adds to the maldistribution of dermatologists by geography, they said. “This demographic pattern poses an additional threat because almost half of rural dermatology practices were solo practices as of 2014,” they noted.

In addition, women make up approximately half of the current and future dermatology workforce, and they have historically been less likely to move to rural areas, even when offered forgiveness on student loans. Even so, the authors encouraged the use of exposure to rural medicine to establish a connection to an area, along with financial incentives and loan repayment.

“In parallel, because there appears to be increasing willingness to fund telemedicine, doubling down on training rural physicians and APPs in some areas of dermatology and engaging technology to support them seems prudent and responsible,” they wrote. “We may not be able to modify the overall dermatology workforce imbalance, but ensuring timely access to our expertise for those patients who need us most can still be achieved if prioritized correctly” (JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2925).

Dr. Porter and Dr. Kimball are affiliated with Harvard Medical School in Boston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A stagnation of dermatology training programs in the 1980s and 1990s led to a limited supply of dermatologists, most of whom chose to work in urban areas, and this geographic distribution gap has persisted and worsened, Martina L. Porter, MD, and Alexa B. Kimball, MD, wrote in an editorial. The trend of more dermatologists opting for academic, group, or multispecialty practices instead of solo practices has continued, which adds to the maldistribution of dermatologists by geography, they said. “This demographic pattern poses an additional threat because almost half of rural dermatology practices were solo practices as of 2014,” they noted.

In addition, women make up approximately half of the current and future dermatology workforce, and they have historically been less likely to move to rural areas, even when offered forgiveness on student loans. Even so, the authors encouraged the use of exposure to rural medicine to establish a connection to an area, along with financial incentives and loan repayment.

“In parallel, because there appears to be increasing willingness to fund telemedicine, doubling down on training rural physicians and APPs in some areas of dermatology and engaging technology to support them seems prudent and responsible,” they wrote. “We may not be able to modify the overall dermatology workforce imbalance, but ensuring timely access to our expertise for those patients who need us most can still be achieved if prioritized correctly” (JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2925).

Dr. Porter and Dr. Kimball are affiliated with Harvard Medical School in Boston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

, according to data from a longitudinal study published online Sept. 5 in JAMA Dermatology.

Data from previous studies suggest that the demand for dermatologists continues to outpace the supply, thus dermatologists have their choice of locations and prefer urban areas because of greater professional opportunities, desire to live near family, and lack of financial incentives to relocate to underserved areas, wrote Hao Feng, MD, of the department of dermatology, New York University, and his colleagues.

To evaluate the latest longitudinal trends in dermatology and factors affecting geographic distribution, the researchers used the Area Health Resources File from 1995 to 2013 to examine the geographic densities of dermatologists and other physicians, as well as the age distribution of dermatologists. The counties were classified as rural, nonmetropolitan, and metropolitan.

Although the percentage changes in dermatologist density at the county level showed a greater increase during the study period in rural counties (30%) and nonmetropolitan counties (25%), compared with metropolitan counties (18%), the differences in actual density of dermatologists per 100,000 people were highest in urban areas.

Overall, dermatologist density in metropolitan areas increased from 3.47 to 4.11 per 100,000 people between 1995 and 2013. Dermatologist density in nonmetropolitan areas during this time increased from 0.84 in 1995 to 1.05 per 100,000 people in 2013, and from 0.065 to 0.085 per 100,000 people in rural areas during that time.

The researchers also evaluated dermatologist trends by age, and found that the number of dermatologists younger than 55 years increased by 21% in metropolitan areas and by 7% in nonmetropolitan and rural areas combined between 1995 and 2013.

The study findings were strengthened by the long time period, but limited by factors including inability to differentiate among full-time and part-time dermatologists, and among medical or cosmetic dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, the researchers said. However, the results suggest that geographic disparities for dermatologists in the United States continue to increase, and strategies to correct it are important to maintain patient care, they wrote. “Careful workforce planning will be needed to consider alternative health care delivery models, dermatologist recruitment strategies, and the role of nonphysician practitioners and telemedicine, especially in nonmetropolitan or rural areas,” they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Feng H et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3022.

, according to data from a longitudinal study published online Sept. 5 in JAMA Dermatology.

Data from previous studies suggest that the demand for dermatologists continues to outpace the supply, thus dermatologists have their choice of locations and prefer urban areas because of greater professional opportunities, desire to live near family, and lack of financial incentives to relocate to underserved areas, wrote Hao Feng, MD, of the department of dermatology, New York University, and his colleagues.

To evaluate the latest longitudinal trends in dermatology and factors affecting geographic distribution, the researchers used the Area Health Resources File from 1995 to 2013 to examine the geographic densities of dermatologists and other physicians, as well as the age distribution of dermatologists. The counties were classified as rural, nonmetropolitan, and metropolitan.

Although the percentage changes in dermatologist density at the county level showed a greater increase during the study period in rural counties (30%) and nonmetropolitan counties (25%), compared with metropolitan counties (18%), the differences in actual density of dermatologists per 100,000 people were highest in urban areas.

Overall, dermatologist density in metropolitan areas increased from 3.47 to 4.11 per 100,000 people between 1995 and 2013. Dermatologist density in nonmetropolitan areas during this time increased from 0.84 in 1995 to 1.05 per 100,000 people in 2013, and from 0.065 to 0.085 per 100,000 people in rural areas during that time.

The researchers also evaluated dermatologist trends by age, and found that the number of dermatologists younger than 55 years increased by 21% in metropolitan areas and by 7% in nonmetropolitan and rural areas combined between 1995 and 2013.

The study findings were strengthened by the long time period, but limited by factors including inability to differentiate among full-time and part-time dermatologists, and among medical or cosmetic dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, the researchers said. However, the results suggest that geographic disparities for dermatologists in the United States continue to increase, and strategies to correct it are important to maintain patient care, they wrote. “Careful workforce planning will be needed to consider alternative health care delivery models, dermatologist recruitment strategies, and the role of nonphysician practitioners and telemedicine, especially in nonmetropolitan or rural areas,” they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Feng H et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3022.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Geographic disparity for dermatologists in the United States has increased over time.

Major finding: The density of dermatologists increased by 21% from 1995 to 2013, but gaps persist between urban and rural areas.

Study details: A review of county-level data for 1995-2013 from the Area Health Resources File.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Feng H et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3022.

Infliximab biosimilar only moderately less expensive in Medicare Part D

The infliximab-dyyb biosimilar was only moderately less expensive than the originator infliximab product Remicade in the United States in 2017 under Medicare Part D, an analysis shows.

Infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra) cost 18% less than infliximab, with an annual cost exceeding $14,000 in an analysis published online Sept. 4 in JAMA by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

However, “without biosimilar gap discounts in 2017, beneficiaries would have paid more than $5,100 for infliximab-dyyb, or nearly $1,700 more in projected out-of-pocket costs than infliximab,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors wrote.

Biologics represent only 2% of U.S. prescriptions but made up 38% of drug spending in 2015 and accounted for 70% of growth in drug spending from 2010 to 2015, according to Dr. Yazdany and her colleagues.

Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cost more than $14,000 per year, and in 2015, 3 were among the top 15 drugs in terms of Medicare expenditures, they added.

While biosimilars are supposed to increase competition and lower prices, it’s an open question whether they actually reduce out-of-pocket expenditures for the 43 million individuals with drug benefits under Medicare Part D.

That uncertainty is due in part to the complex cost-sharing design of Part D, which includes an initial deductible, a coverage phase, a coverage gap, and catastrophic coverage.

In 2017, the plan included an initial $400 deductible, followed by the coverage phase, in which the patient paid 25% of drug costs. In the coverage gap, which started at $3,700 in total drug costs, the patient’s share of drug costs increased to 40% for biologics, and 51% for biosimilars. In the catastrophic coverage phase, triggered when out-of-pocket costs exceeded $4,950, the patient was responsible for 5% of drug costs.

“Currently, beneficiaries receive a 50% manufacturer discount during the gap for brand-name drugs and biologics, but not for biosimilars,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors said in the report.

To evaluate cost-sharing for infliximab-dyyb, which in 2016 became the first available RA biosimilar, the authors analyzed data for all Part D plans in the June 2017 Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.

Out of 2,547 plans, only 10% covered the biosimilar, while 96% covered infliximab, the authors found.

The mean total cost of infliximab-dyyb was “modestly lower,” they reported. Eight-week prescription costs were $2,185 for infliximab-dyyb versus $2,667 for infliximab, while annual costs were $14,202 for the biosimilar and $17,335 for infliximab.

However, all plans required coinsurance cost-sharing for the biosimilar, they said. The mean coinsurance rate was 26.6% of the total drug cost for the biosimilar and 28.4% for infliximab.

For beneficiaries, projected annual out-of-pocket costs without the gap discount were $5,118 for infliximab-dyyb and $3,432 for infliximab, the researchers said.

Biosimilar gap discounts are set to start in 2019, according to the authors. However, they said those discounts may not substantially reduce out-of-pocket costs for Part D beneficiaries because of the high price of infliximab-dyyb and a coinsurance cost-sharing rate similar to that of infliximab.

“Further policies are needed to address affordability and access to specialty drugs,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors concluded.

The study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert L. Kroc Endowed Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases, and other sources. Dr. Yazdany reported receiving an independent investigator award from Pfizer. Her coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

The infliximab-dyyb biosimilar was only moderately less expensive than the originator infliximab product Remicade in the United States in 2017 under Medicare Part D, an analysis shows.

Infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra) cost 18% less than infliximab, with an annual cost exceeding $14,000 in an analysis published online Sept. 4 in JAMA by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

However, “without biosimilar gap discounts in 2017, beneficiaries would have paid more than $5,100 for infliximab-dyyb, or nearly $1,700 more in projected out-of-pocket costs than infliximab,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors wrote.

Biologics represent only 2% of U.S. prescriptions but made up 38% of drug spending in 2015 and accounted for 70% of growth in drug spending from 2010 to 2015, according to Dr. Yazdany and her colleagues.

Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cost more than $14,000 per year, and in 2015, 3 were among the top 15 drugs in terms of Medicare expenditures, they added.

While biosimilars are supposed to increase competition and lower prices, it’s an open question whether they actually reduce out-of-pocket expenditures for the 43 million individuals with drug benefits under Medicare Part D.

That uncertainty is due in part to the complex cost-sharing design of Part D, which includes an initial deductible, a coverage phase, a coverage gap, and catastrophic coverage.

In 2017, the plan included an initial $400 deductible, followed by the coverage phase, in which the patient paid 25% of drug costs. In the coverage gap, which started at $3,700 in total drug costs, the patient’s share of drug costs increased to 40% for biologics, and 51% for biosimilars. In the catastrophic coverage phase, triggered when out-of-pocket costs exceeded $4,950, the patient was responsible for 5% of drug costs.

“Currently, beneficiaries receive a 50% manufacturer discount during the gap for brand-name drugs and biologics, but not for biosimilars,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors said in the report.

To evaluate cost-sharing for infliximab-dyyb, which in 2016 became the first available RA biosimilar, the authors analyzed data for all Part D plans in the June 2017 Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.

Out of 2,547 plans, only 10% covered the biosimilar, while 96% covered infliximab, the authors found.

The mean total cost of infliximab-dyyb was “modestly lower,” they reported. Eight-week prescription costs were $2,185 for infliximab-dyyb versus $2,667 for infliximab, while annual costs were $14,202 for the biosimilar and $17,335 for infliximab.

However, all plans required coinsurance cost-sharing for the biosimilar, they said. The mean coinsurance rate was 26.6% of the total drug cost for the biosimilar and 28.4% for infliximab.

For beneficiaries, projected annual out-of-pocket costs without the gap discount were $5,118 for infliximab-dyyb and $3,432 for infliximab, the researchers said.

Biosimilar gap discounts are set to start in 2019, according to the authors. However, they said those discounts may not substantially reduce out-of-pocket costs for Part D beneficiaries because of the high price of infliximab-dyyb and a coinsurance cost-sharing rate similar to that of infliximab.

“Further policies are needed to address affordability and access to specialty drugs,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors concluded.

The study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert L. Kroc Endowed Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases, and other sources. Dr. Yazdany reported receiving an independent investigator award from Pfizer. Her coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

The infliximab-dyyb biosimilar was only moderately less expensive than the originator infliximab product Remicade in the United States in 2017 under Medicare Part D, an analysis shows.

Infliximab-dyyb (Inflectra) cost 18% less than infliximab, with an annual cost exceeding $14,000 in an analysis published online Sept. 4 in JAMA by Jinoos Yazdany, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her coauthors.

However, “without biosimilar gap discounts in 2017, beneficiaries would have paid more than $5,100 for infliximab-dyyb, or nearly $1,700 more in projected out-of-pocket costs than infliximab,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors wrote.

Biologics represent only 2% of U.S. prescriptions but made up 38% of drug spending in 2015 and accounted for 70% of growth in drug spending from 2010 to 2015, according to Dr. Yazdany and her colleagues.

Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cost more than $14,000 per year, and in 2015, 3 were among the top 15 drugs in terms of Medicare expenditures, they added.

While biosimilars are supposed to increase competition and lower prices, it’s an open question whether they actually reduce out-of-pocket expenditures for the 43 million individuals with drug benefits under Medicare Part D.

That uncertainty is due in part to the complex cost-sharing design of Part D, which includes an initial deductible, a coverage phase, a coverage gap, and catastrophic coverage.

In 2017, the plan included an initial $400 deductible, followed by the coverage phase, in which the patient paid 25% of drug costs. In the coverage gap, which started at $3,700 in total drug costs, the patient’s share of drug costs increased to 40% for biologics, and 51% for biosimilars. In the catastrophic coverage phase, triggered when out-of-pocket costs exceeded $4,950, the patient was responsible for 5% of drug costs.

“Currently, beneficiaries receive a 50% manufacturer discount during the gap for brand-name drugs and biologics, but not for biosimilars,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors said in the report.

To evaluate cost-sharing for infliximab-dyyb, which in 2016 became the first available RA biosimilar, the authors analyzed data for all Part D plans in the June 2017 Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.

Out of 2,547 plans, only 10% covered the biosimilar, while 96% covered infliximab, the authors found.

The mean total cost of infliximab-dyyb was “modestly lower,” they reported. Eight-week prescription costs were $2,185 for infliximab-dyyb versus $2,667 for infliximab, while annual costs were $14,202 for the biosimilar and $17,335 for infliximab.

However, all plans required coinsurance cost-sharing for the biosimilar, they said. The mean coinsurance rate was 26.6% of the total drug cost for the biosimilar and 28.4% for infliximab.

For beneficiaries, projected annual out-of-pocket costs without the gap discount were $5,118 for infliximab-dyyb and $3,432 for infliximab, the researchers said.

Biosimilar gap discounts are set to start in 2019, according to the authors. However, they said those discounts may not substantially reduce out-of-pocket costs for Part D beneficiaries because of the high price of infliximab-dyyb and a coinsurance cost-sharing rate similar to that of infliximab.

“Further policies are needed to address affordability and access to specialty drugs,” Dr. Yazdany and her coauthors concluded.

The study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert L. Kroc Endowed Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases, and other sources. Dr. Yazdany reported receiving an independent investigator award from Pfizer. Her coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infliximab-dyyb was 18% less costly than infliximab, with an annual cost exceeding $14,000.

Study details: Analysis of data for 2,547 Part D plans in the June 2017 Medicare Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Robert L. Kroc Endowed Chair in Rheumatic and Connective Tissue Diseases, and other sources. One author reported receiving an independent investigator award from Pfizer.

Source: Yazdany J et al. JAMA. 2018;320(9):931-3.

Acute biliary pancreatitis linked to poor outcomes in elderly

Mortality was almost three times as high in elderly patients after stringent matching for confounding variables, wrote researcher Kishan Patel, MD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus, and coauthors.

These findings represent a “current health care concern,” since the elderly population in the United States is expected to double within the next several decades and the prevalence of acute pancreatitis is on the rise, Dr. Patel and colleagues wrote in a report on the analysis in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

The analysis is the first, to the investigators’ knowledge, that addresses national-level outcomes associated with acute biliary pancreatitis in elderly patients.

To evaluate clinical outcomes of elderly patients with acute biliary pancreatitis, Dr. Patel and colleagues queried the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which is the largest inpatient readmission database in the United States.

The investigators looked at outcomes associated with index hospitalizations, defined as a patient’s first hospitalization in a calendar year, and found 184,763 adult patients who received a diagnosis of acute biliary pancreatitis between 2011 and 2014. Of those, 41% were elderly.

The mortality rate associated with the index admission was 1.96% (n = 356) for the elderly patients, compared with just 0.32% (n = 1,473) for nonelderly patients (P less than .001), according to the report.

Mortality was increased in the elderly versus nonelderly patients, with an odds ratio of 2.8 (95% CI, 2.2-3.5), according to results of a propensity score matched analysis. Likewise, severe acute pancreatitis was increased in the elderly, with an OR of 1.2 (95% CI: 1.1-1.3) in that analysis.

By contrast, patient age did not impact 30-day readmission rates, according to results of a multivariate analysis that adjusted for confounding factors.

Mortality and severe acute pancreatitis both increased with age within the elderly cohort, further multivariate analysis showed. For example, the ORs for mortality were 1.39 for patients aged 75-84 years and 2.21 for patients aged 85 years and older, the results show.

The elderly population in the United States is expected to almost double by 2050, rising from 48 to 88 million, Dr. Patel and colleagues said. The number of those aged 85 years or older is expected to increase from 5.9 to 18 million by 2050, at which time they will make up nearly 5% of the total U.S. population.

“This specific demographic is more susceptible to common medical ailments, more troubling is acute pancreatitis is one of the most frequent causes of hospitalization in gastroenterology,” Dr. Patel and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Patel and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest related to the analysis.

SOURCE: Patel K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001108.

Mortality was almost three times as high in elderly patients after stringent matching for confounding variables, wrote researcher Kishan Patel, MD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus, and coauthors.

These findings represent a “current health care concern,” since the elderly population in the United States is expected to double within the next several decades and the prevalence of acute pancreatitis is on the rise, Dr. Patel and colleagues wrote in a report on the analysis in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

The analysis is the first, to the investigators’ knowledge, that addresses national-level outcomes associated with acute biliary pancreatitis in elderly patients.

To evaluate clinical outcomes of elderly patients with acute biliary pancreatitis, Dr. Patel and colleagues queried the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which is the largest inpatient readmission database in the United States.

The investigators looked at outcomes associated with index hospitalizations, defined as a patient’s first hospitalization in a calendar year, and found 184,763 adult patients who received a diagnosis of acute biliary pancreatitis between 2011 and 2014. Of those, 41% were elderly.

The mortality rate associated with the index admission was 1.96% (n = 356) for the elderly patients, compared with just 0.32% (n = 1,473) for nonelderly patients (P less than .001), according to the report.

Mortality was increased in the elderly versus nonelderly patients, with an odds ratio of 2.8 (95% CI, 2.2-3.5), according to results of a propensity score matched analysis. Likewise, severe acute pancreatitis was increased in the elderly, with an OR of 1.2 (95% CI: 1.1-1.3) in that analysis.

By contrast, patient age did not impact 30-day readmission rates, according to results of a multivariate analysis that adjusted for confounding factors.

Mortality and severe acute pancreatitis both increased with age within the elderly cohort, further multivariate analysis showed. For example, the ORs for mortality were 1.39 for patients aged 75-84 years and 2.21 for patients aged 85 years and older, the results show.

The elderly population in the United States is expected to almost double by 2050, rising from 48 to 88 million, Dr. Patel and colleagues said. The number of those aged 85 years or older is expected to increase from 5.9 to 18 million by 2050, at which time they will make up nearly 5% of the total U.S. population.

“This specific demographic is more susceptible to common medical ailments, more troubling is acute pancreatitis is one of the most frequent causes of hospitalization in gastroenterology,” Dr. Patel and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Patel and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest related to the analysis.

SOURCE: Patel K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001108.

Mortality was almost three times as high in elderly patients after stringent matching for confounding variables, wrote researcher Kishan Patel, MD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus, and coauthors.

These findings represent a “current health care concern,” since the elderly population in the United States is expected to double within the next several decades and the prevalence of acute pancreatitis is on the rise, Dr. Patel and colleagues wrote in a report on the analysis in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

The analysis is the first, to the investigators’ knowledge, that addresses national-level outcomes associated with acute biliary pancreatitis in elderly patients.

To evaluate clinical outcomes of elderly patients with acute biliary pancreatitis, Dr. Patel and colleagues queried the Nationwide Readmissions Database, which is the largest inpatient readmission database in the United States.

The investigators looked at outcomes associated with index hospitalizations, defined as a patient’s first hospitalization in a calendar year, and found 184,763 adult patients who received a diagnosis of acute biliary pancreatitis between 2011 and 2014. Of those, 41% were elderly.

The mortality rate associated with the index admission was 1.96% (n = 356) for the elderly patients, compared with just 0.32% (n = 1,473) for nonelderly patients (P less than .001), according to the report.

Mortality was increased in the elderly versus nonelderly patients, with an odds ratio of 2.8 (95% CI, 2.2-3.5), according to results of a propensity score matched analysis. Likewise, severe acute pancreatitis was increased in the elderly, with an OR of 1.2 (95% CI: 1.1-1.3) in that analysis.

By contrast, patient age did not impact 30-day readmission rates, according to results of a multivariate analysis that adjusted for confounding factors.

Mortality and severe acute pancreatitis both increased with age within the elderly cohort, further multivariate analysis showed. For example, the ORs for mortality were 1.39 for patients aged 75-84 years and 2.21 for patients aged 85 years and older, the results show.

The elderly population in the United States is expected to almost double by 2050, rising from 48 to 88 million, Dr. Patel and colleagues said. The number of those aged 85 years or older is expected to increase from 5.9 to 18 million by 2050, at which time they will make up nearly 5% of the total U.S. population.

“This specific demographic is more susceptible to common medical ailments, more troubling is acute pancreatitis is one of the most frequent causes of hospitalization in gastroenterology,” Dr. Patel and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Patel and coauthors reported no conflicts of interest related to the analysis.

SOURCE: Patel K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001108.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Compared with younger patients, elderly patients admitted for acute biliary pancreatitis have increased rates of adverse outcomes.

Major finding: Elderly patients had increased mortality (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-3.5) and severe acute pancreatitis (OR, 1.2; 95% CI: 1.1-1.3).

Study details: A propensity score matched analysis of a large, nationally representative database including nearly 185,000 adults with acute biliary pancreatitis.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no conflicts of interest related to the study.

Source: Patel K et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001108.

Huddling for High-Performing Teams

In short team huddles, trainees and PACT teamlets meet to coordinate care and identify ways to improve team processes under the guidance of faculty members who reinforce collaborative practice and continuous improvement.

In 2011, 5 US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) medical centers were selected by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) to establish Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education (CoEPCE). Part of the VA New Models of Care initiative, the 5 CoEPCEs (Boise, Cleveland, San Francisco, Seattle and West Haven) are utilizing VA primary care settings to develop and test innovative approaches to prepare physician residents, nurse practitioner (NP) students and residents (postgraduate), and other health professions trainees, such as pharmacy, social work, psychology, physician assistants (PAs), dieticians, etc for primary care practice.

The CoEPCEs are interprofessional academic patient aligned care teams (PACTs) defined by VA as a PACT that has at least 2 professions of trainees on the team engaged in learning.

The San Francisco VA Health Care System (SFVAHCS) Education in PACT (EdPACT)/CoEPCE developed and implemented a workplace learning model that embeds trainees into PACT teamlets and clinic workflow.1 Trainees are organized in practice partner triads with 2 second- or third-year internal medicine residents (R2s and R3s) and 1 NP student or resident. Physician residents rotate every 2 months between inpatient and outpatient settings and NP trainees are present continuously for 12 months. In this model, each trainee in the triad has his/her own patient panel and serves as a partner who delivers care to his/her partners’ patients when they are unavailable. Didactic sessions on clinical content and on topics related to the core domains occur 3-times weekly during pre- and postclinic conferences.2

Methods

In 2015, evaluators from the OAA reviewed background documents and conducted open-ended interviews with 9 CoEPCE staff, participating trainees, VA faculty, VA facility leadership, and affiliate faculty. Informants described their involvement, challenges encountered, and benefits of the huddle to participants, veterans, and the VA.

The Huddle

With the emphasis on patient-centered medical homes and team-based care in the Affordable Care Act, there is an urgent need to develop new training models that provide future health professionals with skills that support interprofessional communication and collaborative practice.2,3 A key aim of the CoEPCE is to expand workplace learning strategies and clinical opportunities for interprofessional trainees to work together as a team to anticipate and address the health care needs of veterans. Research suggests that patient care improves when team members develop a shared understanding of each other’s skill sets, care procedures, and values.4 In 2010, the SFVAHCS began phasing in VA-mandated PACTs. Each patient-aligned care teamlet serves about 1,200 patients and is composed of physician or NP primary care provider(s) (PCPs) and a registered nurse (RN) care manager, a licensed vocational nurse (LVN), and a medical support assistant (MSA). About every 3 teamlets also work with a profession-specific team member from the Social Work and Pharmacy departments. The implementation of PACT created an opportunity for the CoEPCE to add trainees of various professions to 13 preexisting PACTs in 3 SFVAHCS primary care clinics. This arrangement benefits both trainees and teamlets: trainees learn how to collaborate with clinic staff while the clinic PACT teamlets benefit from coaching by faculty skilled in team-based care.

As part of routine clinical activities, huddles provide opportunities for workplace learning related to coordination of care, building relationships, and developing a sense of camaraderie that is essential for team-based, patient-centered care. In their ideal state, huddles are “…the hub of interprofessional, team-based care”; they provide a venue where trainees can learn communication skills, team member roles, systems issues and resources, and clinical knowledge expected of full-time providers and staff.5 Embedding faculty in huddles as huddle coaches help ensure trainees are learning and applying these skills.

Planning and Implementation

After OAA funded the CoEPCE in 2011, faculty had 6 months to develop the EdPACT curriculum, which included a team building retreat, interactive didactic sessions, and workplace learning activities (ie, huddles). In July 2011, 10 trainee triads (each consisting of 2 physician residents and either a student NP or resident NP) were added to preexisting PACTs at the San Francisco VA Medical Center primary care clinic and 2 community-based outpatient clinics.

These trainee triads partnered with their PACT teamlets and huddled for 15 minutes at the beginning of each clinic day to plan for the day’s patients and future scheduled patients and to coordinate care needs for their panel of patients. CoEPCE staff built on this basic huddle model and made the following lasting modifications:

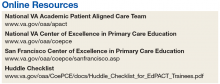

- Developed and implemented a huddle coach model and a huddle checklist to provide structure and feedback to the huddle (Online Resources);

- Scheduled huddles in NP student/resident’s exam room to reduce the hierarchy in the trainee triad;

- Incorporated trainees from other professions and levels into the huddle (psychology fellows, pharmacy residents, social work); and

- Linked the PACT teamlet (staff) to quality improvement projects that are discussed periodically in huddles and didactics.

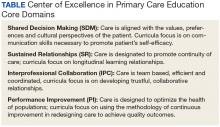

Curriculum. The huddle allows for practical application of the 4 core domains: interprofessional collaboration (IPC), performance improvement (PI), sustained relationships (SR), and shared decision making (SDM) that shape the CoE curriculum.

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is the primary domain reinforced in the huddle. Trainees learn key content in half-day team retreats held at the beginning of the academic year and in interactive didactic sessions. These sessions, which draw on concepts from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s TeamSTEPPS, an evidence-based teamwork training program for health care workers, teach skills like closed-loop communication, check-backs, negotiation, and conflict resolution.

The CoE trainee triads also lead quality improvement (QI) projects, and the huddle is a venue for getting input, which reinforces the CoE’s performance improvement (PI) curriculum. For example, PACT teamlet staff members provide trainees with feedback on proposed QI interventions, such as increasing the use of telephone visits. The huddle supports SR among team members that enhance patient care while improving the quality of the clinic experience for team members. Strengthened communications and increased understanding of team member roles and system resources supports a patient-centered approach to care and lays the foundation for SDM between patients and team members.

Faculty Roles and Development. The CoEPCE physician and NP faculty members who precept and function as huddle coaches participate in monthly 2-hour faculty development sessions to address topics related to IPE. At least 1 session each year covers review of the items on the huddle checklist, tips on how to coach a huddle, discussions of the role of huddle coaches, and feedback and mentoring skills. Many huddle coach activities are inherent to clinical precepting, such as identifying appropriate clinical resources and answering clinical questions, but the core function of the huddle coach is to facilitate effective communication among team members.

Initially, a coach may guide the huddle by rounding up team members or directing the agenda of the huddle (ie, prompting the LVN to present the day’s patients and suggesting the group identify and discuss high-risk patients). As the year progresses, coaches often take a backseat, and the huddle may be facilitated by the trainees, the RN, LVN, or a combination of all members. During the huddle, coaches also may reinforce specific communication skills, such as a “check back” or ISBAR ( Identify who you are, describe the Situation, provide Background information, offer an Assessment of the situation/needs, make a Recommendation or Request)—skills that are taught during CoE didactic sessions.

The coach may call attention to particular feedback points, such as clarification of the order as an excellent example of a check-back. Each preceptor coaches 1 huddle per precepting session. After the teams huddle, preceptors do a smaller, shorter huddle in the precepting room to share successes, such as interprofessional trainees demonstrating backup behavior (eg, “in today’s huddle, I saw a great example of backup behavior when the medicine resident offered to show the NP student how to consent someone”) and discuss challenges (eg, getting all team members to the huddle).

Resources. The CoE staff schedule at least 20 huddles per week and coordinate preceptor and room schedules. The other required resources are clinic staff (RNs, LVNs, and MSAs) and exam rooms large enough to accommodate 8 or more people. Sufficient staffing coverage and staggered huddles also are important to allow cross-coverage for other clinical duties while team members and faculty are huddling.

Monitoring and Assessment. The CoE staff administer the Team Development Measure (TDM) twice yearly and a modified version of the TEAM 360 feedback survey once per year.6-9 The TDM member gages perceptions of team functioning (cohesiveness, communication, role clarity, and clarity of goals and means). Teams meet with a facilitator to debrief their TDM results and discuss ways to improve their team processes. Three-quarters of the way through the academic year, team members also complete the modified TEAM 360 survey on trainees. Each trainee receives a report describing his/her self-ratings and aggregate team member ratings on leadership, communication, interpersonal skills, and feedback.

Partnerships

In addition to CoEPCE staff and faculty support and engagement, huddles at SFVAHCS have benefited from partnerships with VA primary care leadership and with academic affiliates. In particular, support from the VA clinic directors and nurse managers was key to instituting changes to the clinics’ structure to include interprofessional trainees in huddles.