User login

Growing spot on face

The FP suspected melanoma and recommended immediate biopsy. The patient consented, and the physician performed a broad shave biopsy that included most of the pigmented lesion. Pathology revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.3 mm.

Lentigo maligna melanoma occurs in 4% to 15% of cutaneous melanomas. It’s similar to the superficial spreading type and appears as a flat (or mildly elevated) mottled tan, brown, or dark-brown discoloration. This type of melanoma is found most often in the elderly and arises on chronically sun-exposed, damaged skin on the face, ears, arms, and upper trunk. The average age of onset is 65 years and it grows slowly over 5 to 20 years.

When melanoma is suspected, it’s best to provide a specimen with adequate depth and breadth. Unfortunately, choosing the darkest and most raised area does not guarantee the correct diagnosis in a partial biopsy.

In cases of suspected lentigo maligna melanoma on the face, a broad shave provides a better sample than a punch biopsy. The broad shave biopsy (also known as saucerization) is best performed with a razor blade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

In this case, the relatively small size of the lesion and the high risk for melanoma would make an elliptical excisional biopsy a good alternative. The saucerization has the advantage of being quick and easy to perform so that it can be done on the day that the melanoma is suspected.

This patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was not indicated, and the prognosis for this stage Ia melanoma was relatively good.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected melanoma and recommended immediate biopsy. The patient consented, and the physician performed a broad shave biopsy that included most of the pigmented lesion. Pathology revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.3 mm.

Lentigo maligna melanoma occurs in 4% to 15% of cutaneous melanomas. It’s similar to the superficial spreading type and appears as a flat (or mildly elevated) mottled tan, brown, or dark-brown discoloration. This type of melanoma is found most often in the elderly and arises on chronically sun-exposed, damaged skin on the face, ears, arms, and upper trunk. The average age of onset is 65 years and it grows slowly over 5 to 20 years.

When melanoma is suspected, it’s best to provide a specimen with adequate depth and breadth. Unfortunately, choosing the darkest and most raised area does not guarantee the correct diagnosis in a partial biopsy.

In cases of suspected lentigo maligna melanoma on the face, a broad shave provides a better sample than a punch biopsy. The broad shave biopsy (also known as saucerization) is best performed with a razor blade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

In this case, the relatively small size of the lesion and the high risk for melanoma would make an elliptical excisional biopsy a good alternative. The saucerization has the advantage of being quick and easy to perform so that it can be done on the day that the melanoma is suspected.

This patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was not indicated, and the prognosis for this stage Ia melanoma was relatively good.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP suspected melanoma and recommended immediate biopsy. The patient consented, and the physician performed a broad shave biopsy that included most of the pigmented lesion. Pathology revealed a lentigo maligna melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.3 mm.

Lentigo maligna melanoma occurs in 4% to 15% of cutaneous melanomas. It’s similar to the superficial spreading type and appears as a flat (or mildly elevated) mottled tan, brown, or dark-brown discoloration. This type of melanoma is found most often in the elderly and arises on chronically sun-exposed, damaged skin on the face, ears, arms, and upper trunk. The average age of onset is 65 years and it grows slowly over 5 to 20 years.

When melanoma is suspected, it’s best to provide a specimen with adequate depth and breadth. Unfortunately, choosing the darkest and most raised area does not guarantee the correct diagnosis in a partial biopsy.

In cases of suspected lentigo maligna melanoma on the face, a broad shave provides a better sample than a punch biopsy. The broad shave biopsy (also known as saucerization) is best performed with a razor blade. (See the Watch & Learn video on “Shave biopsy.”)

In this case, the relatively small size of the lesion and the high risk for melanoma would make an elliptical excisional biopsy a good alternative. The saucerization has the advantage of being quick and easy to perform so that it can be done on the day that the melanoma is suspected.

This patient was referred for Mohs surgery for complete excision and repair. A sentinel lymph node biopsy was not indicated, and the prognosis for this stage Ia melanoma was relatively good.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ, Usatine, R. Lentigo maligna. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:981-984.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

It takes guts to be mentally ill: Microbiota and psychopathology

What is the largest endocrine organ in the human body?

Here is a clue: It is also the largest immune organ in humans!

Still scratching your head? Here is another clue: This organ also contains a “second brain,” which is connected to big brain inside the head by the vagus nerve.

Okay, enough guessing: It’s the 30-foot long gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is generally associated only with eating and digestion. But it is far more than a digestive tract. It is home to about 100 trillion diverse bacteria, including 1,000 known species, which together are known as “microbiota.” Its combined DNA is called the “microbiome” and is 10,000% larger than the human genome. Those trillions of bacteria in our guts are a symbiotic (commensal) organ that is vital for the normal functions of the human body.1

While this vast array of microorganisms is vital to sustaining a healthy human existence, it can also be involved in multiple psychiatric disorders, including depression, psychosis, anxiety, autism, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Humans acquire their unique sets of microbiota as they pass through the mother’s vagina at birth and while breastfeeding, as well as from exposure to various environmental sources in the first few months of life.2

The microbiota in the GI tract are an intimate neighbor of the “enteric brain,” comprised of 100 million neurons plus glia-like support cell structures. This “second brain” produces over 30 neurotransmitters, several of which (dopamine, serotonin, γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA], acetylcholine) have been implicated in major psychiatric disorders.3

The brain and gut have a dynamic bidirectional communication system, mediated by neural, hormonal, and immunological crosstalk and influences. The GI tract secretes dozens of peptides and other signaling molecules that influence the brain. The microbiota also interact with and are regulated by gut hormones such as oxytocin, ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, cholecystokinin, corticotrophin-releasing factor, and pancreatic polypeptide.4 The microbiota modulate brain development, functions, and behavior, and maintain the intestinal barrier, which, if disrupted, would result in the gut becoming “leaky” and triggering low-grade inflammation such as that associated with depression.5

Continue to: But don't overlook the importance of...

But don’t overlook the importance of diet. It is a major factor in shaping the composition of the microbiota. What we eat can have a preventative or reparative effect on neuroimmune or neuroinflammatory disease. An emerging body of evidence suggests that the diet and its effects on the gut microbiota can modify a person’s genes by epigenetic mechanisms (altering DNA methylation and histone effects). Probiotics can exert epigenetic effects by influencing cytokines, by producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), by vitamin synthesis, and by producing several well-known neurotransmitters.6

The bidirectional trafficking across the microbiome-gut-brain axis includes reciprocal effects. The brain influences the microbiome composition by regulating satiety, the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, and with neuropeptides.7 In return, the microbiome conveys information to the brain about the intestinal status via infectious agents, intestinal neurotransmitters and modulators, cytokines, sensory vagal fibers, and various metabolites. Failure of these normal interactions can lead to a variety of pathological processes, including inflammatory, autoimmune, degenerative, metabolic, cognitive, mood, and behavioral adverse effects. Therapeutic interventions for these adverse consequences can be implemented through microbiome manipulations (such as fecal transplants), nutritional strategies, and reinforcement of the enteric and brain barriers.

Alterations in the microbiota, such as by the intake of antibiotics or by intestinal inflammation, can lead to psychiatric disorders.8 The following findings link gut microbiome disruptions with several psychiatric disorders:

Schizophrenia prodrome. Fecal bacteria show an increase in SCFAs, which can activate microglia (the initial step in triggering psychosis).9 These bacteria have been shown to lead to an increase in choline levels in the anterior cingulate, a known biomarker for membrane dysfunction, which is one of the biological models of schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia—first-episode. A recent study reported abnormalities in the gut microbiota of patients with first-episode psychosis, with a lower number of certain fecal bacteria (including bifidobacterium, E. coli, and lactobacillus) and high levels of Clostridium coccoides. After 6 months of risperidone treatment, the above changes were reversed.10

Continue to: Another study of fecal microbiota...

Another study of fecal microbiota in a first-episode psychosis cohort found significant differences in several bacterial strains compared with a healthy control group, and those with the strongest difference had more severe psychotic symptoms and poorer response after 12 months of antipsychotic treatment.11

Autism has been linked to increased microbiota diversity, and an excess of bacteroides has been associated with a higher diversity of autism. Fecal samples from autistic children were reported to have an increase in SCFAs. Interestingly, a certain strain of lactobacillus can modulate oxytocin or reverse some autistic symptoms.

Depression has been associated with increased diversity of microbiota alpha. Patients with depression have been reported to have low numbers of bifidobacterium

ADHD. Some studies suggest that ADHD may be linked to factors that can alter gut microbiota, including birthing mode, type of infant feeding, maternal health, and early stressors. In addition, dietary influences on gut microbiota can modify ADHD symptoms.14

Alzheimer’s disease. Metabolic dysregulation, such as obesity and diabetes, can inflame the gut microbiota, and are known risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease.15

Continue to: Irritable bowel sydrome...

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Fecal microbiota transplantation has been shown to improve IBS by increasing the diversity of gut microbiota.16 It also improves patients’ mood, not just their IBS symptoms.

Alcohol use. Both alcohol consumption and alcohol withdrawal have been shown to cause immune dysregulation in the brain leading to neuroinflammation. This is attributed to the alteration in the composition of the microbiome (dysbiosis), which has a negative effect on the microbe-host homeostasis.17

The discovery of microbiome-gut-brain interactions and their bidirectional immune, endocrine, and neurotransmitter effects has been a momentous paradigm shift in health, neuroscience, and psychiatry.18 It has opened wide vistas of research for potential innovations in the prevention and treatment of various psychiatric disorders. Radical medical interventions that were previously inconceivable, such as fecal transplantation,19 are an example of the bold insights this new field of microbiome-gut-brain interaction is bringing to the landscape of medicine, including psychiatry. It has also highlighted the previously underappreciated importance of nutrition in health and disease.20

1. Nasrallah HA. Psychoneurogastroenterology: the abdominal brain, the microbiome, and psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):10-11.

2. Dinan TG, Borre YE, Cryan JF. Genomics of schizophrenia: time to consider the gut microbiome? Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(12):1252-1257.

3. Alam R, Abdolmaleky HM, Zhou JR. Microbiome, inflammation, epigenetic alterations, and mental diseases. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(6):651-660.

4. Lach G, Schellekens H, Dinan TG, et al. Anxiety, depression, and the microbiome: a role for gut peptides. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(1):36-59.

5. Kelly JR, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, et al. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:392.

6. Rodrigues-Amorim D, Rivera-Baltanás T, Regueiro B, et al. The role of the gut microbiota in schizophrenia: current and future perspectives. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;21:1-15.

7. Petra AI, Panagiotidou S, Hatziagelaki E, et al. Gut-microbiota-brain axis and its effect on neuropsychiatric disorders with suspected immune dysregulation. Clin Ther. 2015;37(5):984-995.

8. Lurie I, Yang YX, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and the risk for depression, anxiety, or psychosis: a nested case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):1522-1528.

9. He Y, Kosciolek T, Tang J, et al. Gut microbiome and magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of subjects at ultra-high risk for psychosis may support the membrane hypothesis. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:37-45.

10. Yuan X, Zhang P, Wang Y, et al. Changes in metabolism and microbiota after 24-week risperidone treatment in drug naïve, normal weight patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;pii: S0920-9964(18)30274-3. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.017.

11. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

12. Huang R, Wang K, Hu J. Effect of probiotics on depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2016;8(8):pii: E483. doi: 10.3390/nu8080483.

13. Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, et al. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26191. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26191.

14. Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, et al. Practitioner review: what have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(1):3-16.

15. Jiang C, Li G, Huang P, et al. The gut microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(1):1-15.

16. Kurokawa S, Kishimoto T, Mizuno S, et al. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea and functional constipation: an open-label observational study. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:506-512.

17. Hillemacher T, Bachmann O, Kahl KG, et al. Alcohol, microbiome, and their effect on psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;85:105-115.

18. Doré J, Multon MC, Béhier JM; participants of Giens XXXII, Round Table No. 2. The human gut microbiome as source of innovation for health: which physiological and therapeutic outcomes could we expect? Therapie. 2017;72(1):21-38.

19. Vemuri RC, Gundamaraju R, Shinde T, et al. Therapeutic interventions for gut dysbiosis and related disorders in the elderly: antibiotics, probiotics or faecal microbiota transplantation? Benef Microbes. 2017;8(2):179-192.

20. Lombardi VC, De Meirleir KL, Subramanian K, et al. Nutritional modulation of the intestinal microbiota; future opportunities for the prevention and treatment of neuroimmune and neuroinflammatory disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;61:1-16.

What is the largest endocrine organ in the human body?

Here is a clue: It is also the largest immune organ in humans!

Still scratching your head? Here is another clue: This organ also contains a “second brain,” which is connected to big brain inside the head by the vagus nerve.

Okay, enough guessing: It’s the 30-foot long gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is generally associated only with eating and digestion. But it is far more than a digestive tract. It is home to about 100 trillion diverse bacteria, including 1,000 known species, which together are known as “microbiota.” Its combined DNA is called the “microbiome” and is 10,000% larger than the human genome. Those trillions of bacteria in our guts are a symbiotic (commensal) organ that is vital for the normal functions of the human body.1

While this vast array of microorganisms is vital to sustaining a healthy human existence, it can also be involved in multiple psychiatric disorders, including depression, psychosis, anxiety, autism, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Humans acquire their unique sets of microbiota as they pass through the mother’s vagina at birth and while breastfeeding, as well as from exposure to various environmental sources in the first few months of life.2

The microbiota in the GI tract are an intimate neighbor of the “enteric brain,” comprised of 100 million neurons plus glia-like support cell structures. This “second brain” produces over 30 neurotransmitters, several of which (dopamine, serotonin, γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA], acetylcholine) have been implicated in major psychiatric disorders.3

The brain and gut have a dynamic bidirectional communication system, mediated by neural, hormonal, and immunological crosstalk and influences. The GI tract secretes dozens of peptides and other signaling molecules that influence the brain. The microbiota also interact with and are regulated by gut hormones such as oxytocin, ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, cholecystokinin, corticotrophin-releasing factor, and pancreatic polypeptide.4 The microbiota modulate brain development, functions, and behavior, and maintain the intestinal barrier, which, if disrupted, would result in the gut becoming “leaky” and triggering low-grade inflammation such as that associated with depression.5

Continue to: But don't overlook the importance of...

But don’t overlook the importance of diet. It is a major factor in shaping the composition of the microbiota. What we eat can have a preventative or reparative effect on neuroimmune or neuroinflammatory disease. An emerging body of evidence suggests that the diet and its effects on the gut microbiota can modify a person’s genes by epigenetic mechanisms (altering DNA methylation and histone effects). Probiotics can exert epigenetic effects by influencing cytokines, by producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), by vitamin synthesis, and by producing several well-known neurotransmitters.6

The bidirectional trafficking across the microbiome-gut-brain axis includes reciprocal effects. The brain influences the microbiome composition by regulating satiety, the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, and with neuropeptides.7 In return, the microbiome conveys information to the brain about the intestinal status via infectious agents, intestinal neurotransmitters and modulators, cytokines, sensory vagal fibers, and various metabolites. Failure of these normal interactions can lead to a variety of pathological processes, including inflammatory, autoimmune, degenerative, metabolic, cognitive, mood, and behavioral adverse effects. Therapeutic interventions for these adverse consequences can be implemented through microbiome manipulations (such as fecal transplants), nutritional strategies, and reinforcement of the enteric and brain barriers.

Alterations in the microbiota, such as by the intake of antibiotics or by intestinal inflammation, can lead to psychiatric disorders.8 The following findings link gut microbiome disruptions with several psychiatric disorders:

Schizophrenia prodrome. Fecal bacteria show an increase in SCFAs, which can activate microglia (the initial step in triggering psychosis).9 These bacteria have been shown to lead to an increase in choline levels in the anterior cingulate, a known biomarker for membrane dysfunction, which is one of the biological models of schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia—first-episode. A recent study reported abnormalities in the gut microbiota of patients with first-episode psychosis, with a lower number of certain fecal bacteria (including bifidobacterium, E. coli, and lactobacillus) and high levels of Clostridium coccoides. After 6 months of risperidone treatment, the above changes were reversed.10

Continue to: Another study of fecal microbiota...

Another study of fecal microbiota in a first-episode psychosis cohort found significant differences in several bacterial strains compared with a healthy control group, and those with the strongest difference had more severe psychotic symptoms and poorer response after 12 months of antipsychotic treatment.11

Autism has been linked to increased microbiota diversity, and an excess of bacteroides has been associated with a higher diversity of autism. Fecal samples from autistic children were reported to have an increase in SCFAs. Interestingly, a certain strain of lactobacillus can modulate oxytocin or reverse some autistic symptoms.

Depression has been associated with increased diversity of microbiota alpha. Patients with depression have been reported to have low numbers of bifidobacterium

ADHD. Some studies suggest that ADHD may be linked to factors that can alter gut microbiota, including birthing mode, type of infant feeding, maternal health, and early stressors. In addition, dietary influences on gut microbiota can modify ADHD symptoms.14

Alzheimer’s disease. Metabolic dysregulation, such as obesity and diabetes, can inflame the gut microbiota, and are known risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease.15

Continue to: Irritable bowel sydrome...

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Fecal microbiota transplantation has been shown to improve IBS by increasing the diversity of gut microbiota.16 It also improves patients’ mood, not just their IBS symptoms.

Alcohol use. Both alcohol consumption and alcohol withdrawal have been shown to cause immune dysregulation in the brain leading to neuroinflammation. This is attributed to the alteration in the composition of the microbiome (dysbiosis), which has a negative effect on the microbe-host homeostasis.17

The discovery of microbiome-gut-brain interactions and their bidirectional immune, endocrine, and neurotransmitter effects has been a momentous paradigm shift in health, neuroscience, and psychiatry.18 It has opened wide vistas of research for potential innovations in the prevention and treatment of various psychiatric disorders. Radical medical interventions that were previously inconceivable, such as fecal transplantation,19 are an example of the bold insights this new field of microbiome-gut-brain interaction is bringing to the landscape of medicine, including psychiatry. It has also highlighted the previously underappreciated importance of nutrition in health and disease.20

What is the largest endocrine organ in the human body?

Here is a clue: It is also the largest immune organ in humans!

Still scratching your head? Here is another clue: This organ also contains a “second brain,” which is connected to big brain inside the head by the vagus nerve.

Okay, enough guessing: It’s the 30-foot long gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is generally associated only with eating and digestion. But it is far more than a digestive tract. It is home to about 100 trillion diverse bacteria, including 1,000 known species, which together are known as “microbiota.” Its combined DNA is called the “microbiome” and is 10,000% larger than the human genome. Those trillions of bacteria in our guts are a symbiotic (commensal) organ that is vital for the normal functions of the human body.1

While this vast array of microorganisms is vital to sustaining a healthy human existence, it can also be involved in multiple psychiatric disorders, including depression, psychosis, anxiety, autism, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Humans acquire their unique sets of microbiota as they pass through the mother’s vagina at birth and while breastfeeding, as well as from exposure to various environmental sources in the first few months of life.2

The microbiota in the GI tract are an intimate neighbor of the “enteric brain,” comprised of 100 million neurons plus glia-like support cell structures. This “second brain” produces over 30 neurotransmitters, several of which (dopamine, serotonin, γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA], acetylcholine) have been implicated in major psychiatric disorders.3

The brain and gut have a dynamic bidirectional communication system, mediated by neural, hormonal, and immunological crosstalk and influences. The GI tract secretes dozens of peptides and other signaling molecules that influence the brain. The microbiota also interact with and are regulated by gut hormones such as oxytocin, ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, cholecystokinin, corticotrophin-releasing factor, and pancreatic polypeptide.4 The microbiota modulate brain development, functions, and behavior, and maintain the intestinal barrier, which, if disrupted, would result in the gut becoming “leaky” and triggering low-grade inflammation such as that associated with depression.5

Continue to: But don't overlook the importance of...

But don’t overlook the importance of diet. It is a major factor in shaping the composition of the microbiota. What we eat can have a preventative or reparative effect on neuroimmune or neuroinflammatory disease. An emerging body of evidence suggests that the diet and its effects on the gut microbiota can modify a person’s genes by epigenetic mechanisms (altering DNA methylation and histone effects). Probiotics can exert epigenetic effects by influencing cytokines, by producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), by vitamin synthesis, and by producing several well-known neurotransmitters.6

The bidirectional trafficking across the microbiome-gut-brain axis includes reciprocal effects. The brain influences the microbiome composition by regulating satiety, the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, and with neuropeptides.7 In return, the microbiome conveys information to the brain about the intestinal status via infectious agents, intestinal neurotransmitters and modulators, cytokines, sensory vagal fibers, and various metabolites. Failure of these normal interactions can lead to a variety of pathological processes, including inflammatory, autoimmune, degenerative, metabolic, cognitive, mood, and behavioral adverse effects. Therapeutic interventions for these adverse consequences can be implemented through microbiome manipulations (such as fecal transplants), nutritional strategies, and reinforcement of the enteric and brain barriers.

Alterations in the microbiota, such as by the intake of antibiotics or by intestinal inflammation, can lead to psychiatric disorders.8 The following findings link gut microbiome disruptions with several psychiatric disorders:

Schizophrenia prodrome. Fecal bacteria show an increase in SCFAs, which can activate microglia (the initial step in triggering psychosis).9 These bacteria have been shown to lead to an increase in choline levels in the anterior cingulate, a known biomarker for membrane dysfunction, which is one of the biological models of schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia—first-episode. A recent study reported abnormalities in the gut microbiota of patients with first-episode psychosis, with a lower number of certain fecal bacteria (including bifidobacterium, E. coli, and lactobacillus) and high levels of Clostridium coccoides. After 6 months of risperidone treatment, the above changes were reversed.10

Continue to: Another study of fecal microbiota...

Another study of fecal microbiota in a first-episode psychosis cohort found significant differences in several bacterial strains compared with a healthy control group, and those with the strongest difference had more severe psychotic symptoms and poorer response after 12 months of antipsychotic treatment.11

Autism has been linked to increased microbiota diversity, and an excess of bacteroides has been associated with a higher diversity of autism. Fecal samples from autistic children were reported to have an increase in SCFAs. Interestingly, a certain strain of lactobacillus can modulate oxytocin or reverse some autistic symptoms.

Depression has been associated with increased diversity of microbiota alpha. Patients with depression have been reported to have low numbers of bifidobacterium

ADHD. Some studies suggest that ADHD may be linked to factors that can alter gut microbiota, including birthing mode, type of infant feeding, maternal health, and early stressors. In addition, dietary influences on gut microbiota can modify ADHD symptoms.14

Alzheimer’s disease. Metabolic dysregulation, such as obesity and diabetes, can inflame the gut microbiota, and are known risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease.15

Continue to: Irritable bowel sydrome...

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Fecal microbiota transplantation has been shown to improve IBS by increasing the diversity of gut microbiota.16 It also improves patients’ mood, not just their IBS symptoms.

Alcohol use. Both alcohol consumption and alcohol withdrawal have been shown to cause immune dysregulation in the brain leading to neuroinflammation. This is attributed to the alteration in the composition of the microbiome (dysbiosis), which has a negative effect on the microbe-host homeostasis.17

The discovery of microbiome-gut-brain interactions and their bidirectional immune, endocrine, and neurotransmitter effects has been a momentous paradigm shift in health, neuroscience, and psychiatry.18 It has opened wide vistas of research for potential innovations in the prevention and treatment of various psychiatric disorders. Radical medical interventions that were previously inconceivable, such as fecal transplantation,19 are an example of the bold insights this new field of microbiome-gut-brain interaction is bringing to the landscape of medicine, including psychiatry. It has also highlighted the previously underappreciated importance of nutrition in health and disease.20

1. Nasrallah HA. Psychoneurogastroenterology: the abdominal brain, the microbiome, and psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):10-11.

2. Dinan TG, Borre YE, Cryan JF. Genomics of schizophrenia: time to consider the gut microbiome? Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(12):1252-1257.

3. Alam R, Abdolmaleky HM, Zhou JR. Microbiome, inflammation, epigenetic alterations, and mental diseases. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(6):651-660.

4. Lach G, Schellekens H, Dinan TG, et al. Anxiety, depression, and the microbiome: a role for gut peptides. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(1):36-59.

5. Kelly JR, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, et al. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:392.

6. Rodrigues-Amorim D, Rivera-Baltanás T, Regueiro B, et al. The role of the gut microbiota in schizophrenia: current and future perspectives. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;21:1-15.

7. Petra AI, Panagiotidou S, Hatziagelaki E, et al. Gut-microbiota-brain axis and its effect on neuropsychiatric disorders with suspected immune dysregulation. Clin Ther. 2015;37(5):984-995.

8. Lurie I, Yang YX, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and the risk for depression, anxiety, or psychosis: a nested case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):1522-1528.

9. He Y, Kosciolek T, Tang J, et al. Gut microbiome and magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of subjects at ultra-high risk for psychosis may support the membrane hypothesis. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:37-45.

10. Yuan X, Zhang P, Wang Y, et al. Changes in metabolism and microbiota after 24-week risperidone treatment in drug naïve, normal weight patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;pii: S0920-9964(18)30274-3. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.017.

11. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

12. Huang R, Wang K, Hu J. Effect of probiotics on depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2016;8(8):pii: E483. doi: 10.3390/nu8080483.

13. Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, et al. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26191. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26191.

14. Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, et al. Practitioner review: what have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(1):3-16.

15. Jiang C, Li G, Huang P, et al. The gut microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(1):1-15.

16. Kurokawa S, Kishimoto T, Mizuno S, et al. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea and functional constipation: an open-label observational study. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:506-512.

17. Hillemacher T, Bachmann O, Kahl KG, et al. Alcohol, microbiome, and their effect on psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;85:105-115.

18. Doré J, Multon MC, Béhier JM; participants of Giens XXXII, Round Table No. 2. The human gut microbiome as source of innovation for health: which physiological and therapeutic outcomes could we expect? Therapie. 2017;72(1):21-38.

19. Vemuri RC, Gundamaraju R, Shinde T, et al. Therapeutic interventions for gut dysbiosis and related disorders in the elderly: antibiotics, probiotics or faecal microbiota transplantation? Benef Microbes. 2017;8(2):179-192.

20. Lombardi VC, De Meirleir KL, Subramanian K, et al. Nutritional modulation of the intestinal microbiota; future opportunities for the prevention and treatment of neuroimmune and neuroinflammatory disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;61:1-16.

1. Nasrallah HA. Psychoneurogastroenterology: the abdominal brain, the microbiome, and psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):10-11.

2. Dinan TG, Borre YE, Cryan JF. Genomics of schizophrenia: time to consider the gut microbiome? Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(12):1252-1257.

3. Alam R, Abdolmaleky HM, Zhou JR. Microbiome, inflammation, epigenetic alterations, and mental diseases. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174(6):651-660.

4. Lach G, Schellekens H, Dinan TG, et al. Anxiety, depression, and the microbiome: a role for gut peptides. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(1):36-59.

5. Kelly JR, Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, et al. Breaking down the barriers: the gut microbiome, intestinal permeability and stress-related psychiatric disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:392.

6. Rodrigues-Amorim D, Rivera-Baltanás T, Regueiro B, et al. The role of the gut microbiota in schizophrenia: current and future perspectives. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;21:1-15.

7. Petra AI, Panagiotidou S, Hatziagelaki E, et al. Gut-microbiota-brain axis and its effect on neuropsychiatric disorders with suspected immune dysregulation. Clin Ther. 2015;37(5):984-995.

8. Lurie I, Yang YX, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and the risk for depression, anxiety, or psychosis: a nested case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):1522-1528.

9. He Y, Kosciolek T, Tang J, et al. Gut microbiome and magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of subjects at ultra-high risk for psychosis may support the membrane hypothesis. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;53:37-45.

10. Yuan X, Zhang P, Wang Y, et al. Changes in metabolism and microbiota after 24-week risperidone treatment in drug naïve, normal weight patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;pii: S0920-9964(18)30274-3. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.017.

11. Dickerson F, Severance E, Yolken R. The microbiome, immunity, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:46-52.

12. Huang R, Wang K, Hu J. Effect of probiotics on depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2016;8(8):pii: E483. doi: 10.3390/nu8080483.

13. Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, et al. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26191. doi: 10.3402/mehd.v26.26191.

14. Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, et al. Practitioner review: what have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(1):3-16.

15. Jiang C, Li G, Huang P, et al. The gut microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(1):1-15.

16. Kurokawa S, Kishimoto T, Mizuno S, et al. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea and functional constipation: an open-label observational study. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:506-512.

17. Hillemacher T, Bachmann O, Kahl KG, et al. Alcohol, microbiome, and their effect on psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;85:105-115.

18. Doré J, Multon MC, Béhier JM; participants of Giens XXXII, Round Table No. 2. The human gut microbiome as source of innovation for health: which physiological and therapeutic outcomes could we expect? Therapie. 2017;72(1):21-38.

19. Vemuri RC, Gundamaraju R, Shinde T, et al. Therapeutic interventions for gut dysbiosis and related disorders in the elderly: antibiotics, probiotics or faecal microbiota transplantation? Benef Microbes. 2017;8(2):179-192.

20. Lombardi VC, De Meirleir KL, Subramanian K, et al. Nutritional modulation of the intestinal microbiota; future opportunities for the prevention and treatment of neuroimmune and neuroinflammatory disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;61:1-16.

Statins aren’t preventive in elderly unless they have diabetes

Any benefit of statins for primary prevention in older adult populations may depend on whether or not type 2 diabetes is present, results of a retrospective cohort study suggest.

Statins had no protective effect overall in the study, which included adults older than 74 years who had no clinically recognized atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

In older patients with diabetes, statins were associated with reductions in CVD incidence and all-cause mortality. However, this benefit was substantially reduced in patients 85 years and older, and completely absent in those over 90, study authors said in the BMJ.

“These results do not support the widespread use of statins in old and very old populations, but they do support treatment in those with type 2 diabetes younger than 85 years,” said Rafael Ramos, MD, of the University of Girona, Spain, and his coauthors.

While meta-analyses support statins as primary prevention of CVD in individuals 65 years or older, evidence is lacking on those older than 74 years, according to the investigators.

Accordingly, they conducted the present retrospective cohort study based on data from a Spanish primary care database that included patient records for more than 6 million people. They looked specifically for individuals aged 75 years or older with no history of ASCVD who had at least one visit between July 2006 and December 2007.

They found 46,864 people meeting those criteria, of whom 7,502 (16.0%) had started statin treatment and 7,880 (16.8%) had type 2 diabetes.

With a median follow-up of 7.7 years, statin use had no benefit in reducing ASCVD incidence or all-cause mortality for the entire study population, statistical analyses showed.

In participants with diabetes, however, statins did appear protective, at least in the patients aged 75-84 years, with hazard ratios of 0.76 (95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.89) for CVD and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.75-0.94) for all-cause mortality, Dr. Ramos and his colleagues reported.

The 1-year number needed to treat in this 75-84 age group was 164 for atherosclerotic CVD, and 306 for all-cause mortality, they added.

By contrast, the hazard ratios for patients 85 years and older were 0.82 (95% CI, 0.53-1.26) for atherosclerotic CVD, and 1.05 (95% CI, 0.86-1.28) for all-cause mortality, the investigators reported.

The observed reductions in CVD in individuals with diabetes lost statistical significance at age 85 years when investigators looked at hazard ratios for each year of age. Similarly, reductions in all-cause mortality began to lose statistical significance at age 82 years and “definitively disappeared” in those aged 88 years or older, they said.

The project was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Salud, Spain’s Ministry of Science and Innovation through the Carlos III Health Institute and other entities.

Dr. Ramos and his coauthors declared no support in the previous 3 years from any organization related to, or that might have an interest in, the submitted work. They also declared no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the work.

SOURCE: Ramos R et al. BMJ 2018 Sep 5;362:k3359.

Until better evidence is available, patient preference remains the guiding principle in deciding whether to prescribe statins in older adults, according to authors of an accompanying editorial.

“These observational findings are exploratory, however, and should be tested further in randomized trials to rule out any confounding and to study the effect of statins on CVD death, which were not recorded in the database used for this study,” editorial authors Aidan Ryan, MD, Simon Heath, MD, and Paul Cook, MD, wrote in the BMJ.

The ongoing Australian randomized STAREE trial (Statins for Reducing Events in the Elderly) is evaluating primary prevention with atorvastatin 40 mg versus placebo in adults older than 70 years, the authors noted.

While results are awaited, the decision of whether or not to prescribe statins in older adults may depend on their treatment goals, the authors added.

For example, in patients who cite longevity as a treatment goal, the current evidence remains limited that statins as primary prevention could help.

“A patient preference for reduction in myocardial infarction or stroke, however, might help to tilt the balance in favor of statin prescription but the absolute risk reduction, number needed to treat to prevent a CVD event in older patients remains uncertain,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Ryan is an academic clinical fellow and Dr. Cook is a consultant in chemical pathology and metabolic medicine, both at University Hospital Southampton, England. Dr. Heath is in group practice in Warwickshire, England. The authors declared no competing interests.

Until better evidence is available, patient preference remains the guiding principle in deciding whether to prescribe statins in older adults, according to authors of an accompanying editorial.

“These observational findings are exploratory, however, and should be tested further in randomized trials to rule out any confounding and to study the effect of statins on CVD death, which were not recorded in the database used for this study,” editorial authors Aidan Ryan, MD, Simon Heath, MD, and Paul Cook, MD, wrote in the BMJ.

The ongoing Australian randomized STAREE trial (Statins for Reducing Events in the Elderly) is evaluating primary prevention with atorvastatin 40 mg versus placebo in adults older than 70 years, the authors noted.

While results are awaited, the decision of whether or not to prescribe statins in older adults may depend on their treatment goals, the authors added.

For example, in patients who cite longevity as a treatment goal, the current evidence remains limited that statins as primary prevention could help.

“A patient preference for reduction in myocardial infarction or stroke, however, might help to tilt the balance in favor of statin prescription but the absolute risk reduction, number needed to treat to prevent a CVD event in older patients remains uncertain,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Ryan is an academic clinical fellow and Dr. Cook is a consultant in chemical pathology and metabolic medicine, both at University Hospital Southampton, England. Dr. Heath is in group practice in Warwickshire, England. The authors declared no competing interests.

Until better evidence is available, patient preference remains the guiding principle in deciding whether to prescribe statins in older adults, according to authors of an accompanying editorial.

“These observational findings are exploratory, however, and should be tested further in randomized trials to rule out any confounding and to study the effect of statins on CVD death, which were not recorded in the database used for this study,” editorial authors Aidan Ryan, MD, Simon Heath, MD, and Paul Cook, MD, wrote in the BMJ.

The ongoing Australian randomized STAREE trial (Statins for Reducing Events in the Elderly) is evaluating primary prevention with atorvastatin 40 mg versus placebo in adults older than 70 years, the authors noted.

While results are awaited, the decision of whether or not to prescribe statins in older adults may depend on their treatment goals, the authors added.

For example, in patients who cite longevity as a treatment goal, the current evidence remains limited that statins as primary prevention could help.

“A patient preference for reduction in myocardial infarction or stroke, however, might help to tilt the balance in favor of statin prescription but the absolute risk reduction, number needed to treat to prevent a CVD event in older patients remains uncertain,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Ryan is an academic clinical fellow and Dr. Cook is a consultant in chemical pathology and metabolic medicine, both at University Hospital Southampton, England. Dr. Heath is in group practice in Warwickshire, England. The authors declared no competing interests.

Any benefit of statins for primary prevention in older adult populations may depend on whether or not type 2 diabetes is present, results of a retrospective cohort study suggest.

Statins had no protective effect overall in the study, which included adults older than 74 years who had no clinically recognized atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

In older patients with diabetes, statins were associated with reductions in CVD incidence and all-cause mortality. However, this benefit was substantially reduced in patients 85 years and older, and completely absent in those over 90, study authors said in the BMJ.

“These results do not support the widespread use of statins in old and very old populations, but they do support treatment in those with type 2 diabetes younger than 85 years,” said Rafael Ramos, MD, of the University of Girona, Spain, and his coauthors.

While meta-analyses support statins as primary prevention of CVD in individuals 65 years or older, evidence is lacking on those older than 74 years, according to the investigators.

Accordingly, they conducted the present retrospective cohort study based on data from a Spanish primary care database that included patient records for more than 6 million people. They looked specifically for individuals aged 75 years or older with no history of ASCVD who had at least one visit between July 2006 and December 2007.

They found 46,864 people meeting those criteria, of whom 7,502 (16.0%) had started statin treatment and 7,880 (16.8%) had type 2 diabetes.

With a median follow-up of 7.7 years, statin use had no benefit in reducing ASCVD incidence or all-cause mortality for the entire study population, statistical analyses showed.

In participants with diabetes, however, statins did appear protective, at least in the patients aged 75-84 years, with hazard ratios of 0.76 (95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.89) for CVD and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.75-0.94) for all-cause mortality, Dr. Ramos and his colleagues reported.

The 1-year number needed to treat in this 75-84 age group was 164 for atherosclerotic CVD, and 306 for all-cause mortality, they added.

By contrast, the hazard ratios for patients 85 years and older were 0.82 (95% CI, 0.53-1.26) for atherosclerotic CVD, and 1.05 (95% CI, 0.86-1.28) for all-cause mortality, the investigators reported.

The observed reductions in CVD in individuals with diabetes lost statistical significance at age 85 years when investigators looked at hazard ratios for each year of age. Similarly, reductions in all-cause mortality began to lose statistical significance at age 82 years and “definitively disappeared” in those aged 88 years or older, they said.

The project was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Salud, Spain’s Ministry of Science and Innovation through the Carlos III Health Institute and other entities.

Dr. Ramos and his coauthors declared no support in the previous 3 years from any organization related to, or that might have an interest in, the submitted work. They also declared no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the work.

SOURCE: Ramos R et al. BMJ 2018 Sep 5;362:k3359.

Any benefit of statins for primary prevention in older adult populations may depend on whether or not type 2 diabetes is present, results of a retrospective cohort study suggest.

Statins had no protective effect overall in the study, which included adults older than 74 years who had no clinically recognized atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

In older patients with diabetes, statins were associated with reductions in CVD incidence and all-cause mortality. However, this benefit was substantially reduced in patients 85 years and older, and completely absent in those over 90, study authors said in the BMJ.

“These results do not support the widespread use of statins in old and very old populations, but they do support treatment in those with type 2 diabetes younger than 85 years,” said Rafael Ramos, MD, of the University of Girona, Spain, and his coauthors.

While meta-analyses support statins as primary prevention of CVD in individuals 65 years or older, evidence is lacking on those older than 74 years, according to the investigators.

Accordingly, they conducted the present retrospective cohort study based on data from a Spanish primary care database that included patient records for more than 6 million people. They looked specifically for individuals aged 75 years or older with no history of ASCVD who had at least one visit between July 2006 and December 2007.

They found 46,864 people meeting those criteria, of whom 7,502 (16.0%) had started statin treatment and 7,880 (16.8%) had type 2 diabetes.

With a median follow-up of 7.7 years, statin use had no benefit in reducing ASCVD incidence or all-cause mortality for the entire study population, statistical analyses showed.

In participants with diabetes, however, statins did appear protective, at least in the patients aged 75-84 years, with hazard ratios of 0.76 (95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.89) for CVD and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.75-0.94) for all-cause mortality, Dr. Ramos and his colleagues reported.

The 1-year number needed to treat in this 75-84 age group was 164 for atherosclerotic CVD, and 306 for all-cause mortality, they added.

By contrast, the hazard ratios for patients 85 years and older were 0.82 (95% CI, 0.53-1.26) for atherosclerotic CVD, and 1.05 (95% CI, 0.86-1.28) for all-cause mortality, the investigators reported.

The observed reductions in CVD in individuals with diabetes lost statistical significance at age 85 years when investigators looked at hazard ratios for each year of age. Similarly, reductions in all-cause mortality began to lose statistical significance at age 82 years and “definitively disappeared” in those aged 88 years or older, they said.

The project was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Salud, Spain’s Ministry of Science and Innovation through the Carlos III Health Institute and other entities.

Dr. Ramos and his coauthors declared no support in the previous 3 years from any organization related to, or that might have an interest in, the submitted work. They also declared no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the work.

SOURCE: Ramos R et al. BMJ 2018 Sep 5;362:k3359.

FROM THE BMJ

Key clinical point: Any benefit of statins for primary prevention in older adult populations may depend on whether or not type 2 diabetes is present.

Major finding: In participants with diabetes who were aged 75-84 years, hazard ratios were 0.76 (95% confidence interval, 0.65-0.89) for CVD and 0.84 (95% CI, 0.75-0.94) for all-cause mortality; participants with diabetes aged 85 years and older had markedly less benefit.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study including 46,864 individuals aged 75 years or older with no history of atherosclerotic CVD.

Disclosures: The project was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Salud and Spain’s Ministry of Science and Innovation through the Carlos III Health Institute, among other entities. Authors declared no support, relationships, or activities related to the submitted work.

Source: Ramos R et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3359.

Penalties not necessary to save money in some Medicare ACOs

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services may be able to reduce spending through the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) without asking for health care professionals and organizations to take on penalties or so-called downside risk, according to a study published in Sept. 5 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers, using fee-for-service claims from 2009 through 2015 and performing difference-in-difference analyses to compare changes in Medicare spending, found that Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) formed from physician practices were able to save money while hospital-based ACOs were not.

“Our results also suggest that shared-savings contracts that do not impose a downside risk of financial losses for spending above benchmarks – which may appeal to smaller organizations without sufficient reserves to withstand potential losses – may be effective in lowering Medicare spending,” J. Michael McWilliams, MD, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues wrote.

Researchers found that by 2015, groups participating in MSSP, as compared with those who did not participate, were “associated with a mean differential reduction of $302 in total Medicare spending per beneficiary in the 2012 entry of cohorts of ACOs,” without accounting for bonus payments.

“Accounting for shared-savings bonus payments, we determined that the differential spending reductions in the entry cohorts of physician-group ACOs from 2012 through 2014 constituted a net savings to Medicare of $256.4 million in 2015,” Dr. McWilliams and his colleagues wrote. “For hospital-integrated ACOs, bonus payments more than offset annual spending reductions.”

Dr. McWilliams and his colleagues noted that their findings were limited by a narrow focus on organizational structure (financial independence from hospitals), so other factors could have held to differences in savings; changes in coding practices for ACOs coming in as of 2013; lack of data on costs to ACOs or efforts to lower spending or improve quality; and the inability to assess the effects of the MSSP on many aspects of quality of care because of the nature of using claims-based measures.

“Our results probably underestimate savings to Medicare because they do not account for spillover effects of ACO efforts on nonattributed patients or effects of lower fee-for-service Medicare spending on payments to Medicare Advantage plans,” the researchers added.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. McWilliams and Michael Chernew, PhD, also of Harvard Medical School, both have received consulting fees related to ACO research.

SOURCE: McWilliams JM et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803388.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services may be able to reduce spending through the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) without asking for health care professionals and organizations to take on penalties or so-called downside risk, according to a study published in Sept. 5 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers, using fee-for-service claims from 2009 through 2015 and performing difference-in-difference analyses to compare changes in Medicare spending, found that Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) formed from physician practices were able to save money while hospital-based ACOs were not.

“Our results also suggest that shared-savings contracts that do not impose a downside risk of financial losses for spending above benchmarks – which may appeal to smaller organizations without sufficient reserves to withstand potential losses – may be effective in lowering Medicare spending,” J. Michael McWilliams, MD, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues wrote.

Researchers found that by 2015, groups participating in MSSP, as compared with those who did not participate, were “associated with a mean differential reduction of $302 in total Medicare spending per beneficiary in the 2012 entry of cohorts of ACOs,” without accounting for bonus payments.

“Accounting for shared-savings bonus payments, we determined that the differential spending reductions in the entry cohorts of physician-group ACOs from 2012 through 2014 constituted a net savings to Medicare of $256.4 million in 2015,” Dr. McWilliams and his colleagues wrote. “For hospital-integrated ACOs, bonus payments more than offset annual spending reductions.”

Dr. McWilliams and his colleagues noted that their findings were limited by a narrow focus on organizational structure (financial independence from hospitals), so other factors could have held to differences in savings; changes in coding practices for ACOs coming in as of 2013; lack of data on costs to ACOs or efforts to lower spending or improve quality; and the inability to assess the effects of the MSSP on many aspects of quality of care because of the nature of using claims-based measures.

“Our results probably underestimate savings to Medicare because they do not account for spillover effects of ACO efforts on nonattributed patients or effects of lower fee-for-service Medicare spending on payments to Medicare Advantage plans,” the researchers added.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. McWilliams and Michael Chernew, PhD, also of Harvard Medical School, both have received consulting fees related to ACO research.

SOURCE: McWilliams JM et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803388.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services may be able to reduce spending through the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) without asking for health care professionals and organizations to take on penalties or so-called downside risk, according to a study published in Sept. 5 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers, using fee-for-service claims from 2009 through 2015 and performing difference-in-difference analyses to compare changes in Medicare spending, found that Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) formed from physician practices were able to save money while hospital-based ACOs were not.

“Our results also suggest that shared-savings contracts that do not impose a downside risk of financial losses for spending above benchmarks – which may appeal to smaller organizations without sufficient reserves to withstand potential losses – may be effective in lowering Medicare spending,” J. Michael McWilliams, MD, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues wrote.

Researchers found that by 2015, groups participating in MSSP, as compared with those who did not participate, were “associated with a mean differential reduction of $302 in total Medicare spending per beneficiary in the 2012 entry of cohorts of ACOs,” without accounting for bonus payments.

“Accounting for shared-savings bonus payments, we determined that the differential spending reductions in the entry cohorts of physician-group ACOs from 2012 through 2014 constituted a net savings to Medicare of $256.4 million in 2015,” Dr. McWilliams and his colleagues wrote. “For hospital-integrated ACOs, bonus payments more than offset annual spending reductions.”

Dr. McWilliams and his colleagues noted that their findings were limited by a narrow focus on organizational structure (financial independence from hospitals), so other factors could have held to differences in savings; changes in coding practices for ACOs coming in as of 2013; lack of data on costs to ACOs or efforts to lower spending or improve quality; and the inability to assess the effects of the MSSP on many aspects of quality of care because of the nature of using claims-based measures.

“Our results probably underestimate savings to Medicare because they do not account for spillover effects of ACO efforts on nonattributed patients or effects of lower fee-for-service Medicare spending on payments to Medicare Advantage plans,” the researchers added.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. McWilliams and Michael Chernew, PhD, also of Harvard Medical School, both have received consulting fees related to ACO research.

SOURCE: McWilliams JM et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Sep 5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803388.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Physician group ACOs in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) generated more savings than did hospital-led ACO groups.

Major finding: Physician group ACOs joining the MSSP in 2012-2014 generated $256.4 million in Medicare savings in 2015.

Study details: Analysis of fee-for-service Medicare claims during 2009-2015.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. McWilliams and Dr. Chernew disclosed consulting fees related to ACO research.

Source: McWilliams JM et al. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803388.

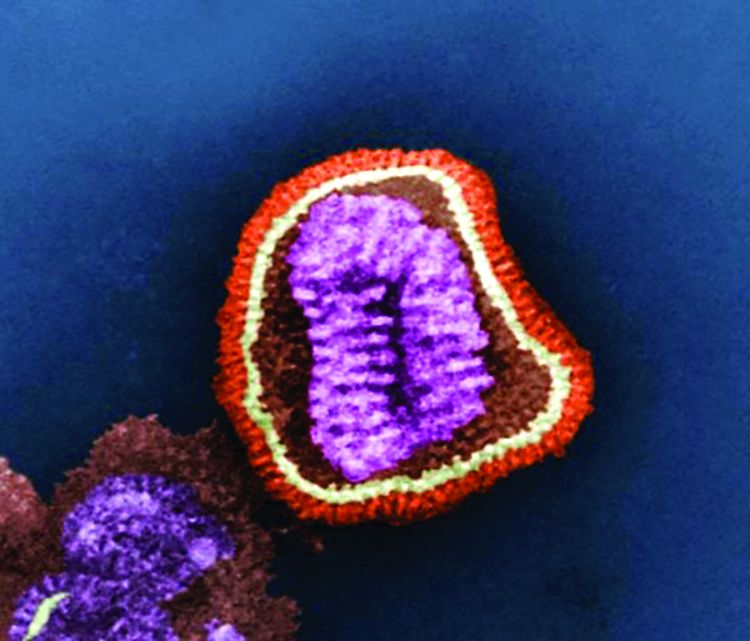

Single-dose influenza drug baloxavir similar to oseltamivir in efficacy

A new single-dose influenza antiviral drug appears significantly better than placebo at relieving the symptoms of infection, and reduces viral load faster than does oseltamivir, new research suggests.

Baloxavir marboxil – a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease – was tested in two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials. The first was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 randomized trial of 389 Japanese adults aged 20-64 years with acute uncomplicated influenza from December 2015 through March 2016. The second was a phase 3 randomized controlled trial of 1,366 patients comparing baloxavir with placebo and oseltamivir.

The phase 2 study showed patients treated with 10 mg, 20 mg or 40 mg oral dose of baloxavir experienced a significantly shorter median time to symptom alleviation compared with placebo (54.2, 51, 49.5, and 77.7 hours, respectively), according to a paper published in the Sept. 6 edition of the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition, all three doses showed significantly greater reductions in influenza virus titers on days 2 and 3, compared with placebo.

The phase 3 trial CAPSTONE-1 (NCT02954354) was a double-blind, placebo- and oseltamivir-controlled, randomized trial that enrolled outpatients aged 12-64 years with influenza-like illness in the United States and Japan from December 2016 through March 2017. Patients aged 20-64 years received a single, weight-based oral dose of baloxavir (40 mg for patients weighing more than 80 kg, 80 mg for those weighing 80 kg or less) on day 1 only or oseltamivir at a dose of 75 mg twice daily or matching placebos on a 5-day regimen.

Patients aged 12-19 years were randomly assigned to receive either baloxavir or placebo on day 1 only, according to the researchers.

The median time to alleviation of symptoms was similar in the baloxavir (53.5 hours) and oseltamivir group (53.8 hours). However, patients taking baloxavir had significantly faster declines in infectious viral load compared with those taking oseltamivir, which was taken as a 75-mg dose twice daily for 5 days. In addition, patients who were treated with baloxavir within 24 hours of symptom onset showed significantly shorter time to alleviation of symptoms compared with placebo than did those who started treatment more than 24 hours after symptoms began.

Adverse events related to the study drug were more common among patients taking oseltamivir (8.4%) compared with those taking baloxavir (4.4%) or placebo (3.9%). In the phase 2 study, the adverse event rate was lower in the three baloxavir dosage groups compared with the placebo group. The study also showed a similar low frequency of complications requiring antibiotic treatment in both the baloxavir, oseltamivir, and placebo arms.

Some patients did show evidence of decreased susceptibility to baloxavir; for example, PA I38T/M amino acid substitutions were seen in 9.7% of the patients taking baloxavir but none of randomly selected patients in the placebo group of the phase 3 trial.

“These trials showed that single doses of the cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir were superior to placebo in alleviating influenza symptoms in patients with uncomplicated influenza, without clinically significant side effects,” wrote Dr. Frederick G. Hayden of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and his coauthors.

“The antiviral effects that were observed with baloxavir in patients with uncomplicated influenza provide encouragement with respect to its potential value in treating complicated or severe influenza infections,” they noted.

Because the treatment was inhibitory for influenza virus strains that were resistant to neuraminidase inhibitors or M2 ion-channel inhibitors, it could be a treatment option for patients infected with those viruses, the researchers added.

CAPSTONE-2, a randomized, controlled trial involving patients at high risk for influenza complications (NCT02949011) is in progress.

The study was supported by Shionogi, which developed baloxavir. Seven authors declared fees from the pharmaceutical industry, including Shionogi. Six authors were employees of Shionogi, one also holding stock. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Hayden F et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:913-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716197.

These two studies of baloxavir show that the drug has a clinical benefit similar to that of oseltamivir in individuals with uncomplicated influenza infection. As a single-dose treatment, baloxavir has the advantage in reducing concerns about adherence compared to the treatment regimen for oseltamivir, which requires 5 days of twice-daily dosing.

However, these studies should be viewed as the first step. While baloxavir showed significantly greater reductions in viral load at 24 hours and a shorter duration of infectious virus detection than did oseltamivir or placebo, it also induced the emergence of viral escape mutants with reduced susceptibility.

It’s not yet known whether these influenza viruses with reduced susceptibility are transmissible, and whether surveillance for I38T and other markers will be needed. We also need trials to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from baloxavir, and the timing for treatment.

Timothy M. Uyeki, MD, is with the Influenza Division at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;397:975-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1810815. No conflicts of interest were declared.

These two studies of baloxavir show that the drug has a clinical benefit similar to that of oseltamivir in individuals with uncomplicated influenza infection. As a single-dose treatment, baloxavir has the advantage in reducing concerns about adherence compared to the treatment regimen for oseltamivir, which requires 5 days of twice-daily dosing.

However, these studies should be viewed as the first step. While baloxavir showed significantly greater reductions in viral load at 24 hours and a shorter duration of infectious virus detection than did oseltamivir or placebo, it also induced the emergence of viral escape mutants with reduced susceptibility.

It’s not yet known whether these influenza viruses with reduced susceptibility are transmissible, and whether surveillance for I38T and other markers will be needed. We also need trials to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from baloxavir, and the timing for treatment.

Timothy M. Uyeki, MD, is with the Influenza Division at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;397:975-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1810815. No conflicts of interest were declared.

These two studies of baloxavir show that the drug has a clinical benefit similar to that of oseltamivir in individuals with uncomplicated influenza infection. As a single-dose treatment, baloxavir has the advantage in reducing concerns about adherence compared to the treatment regimen for oseltamivir, which requires 5 days of twice-daily dosing.

However, these studies should be viewed as the first step. While baloxavir showed significantly greater reductions in viral load at 24 hours and a shorter duration of infectious virus detection than did oseltamivir or placebo, it also induced the emergence of viral escape mutants with reduced susceptibility.

It’s not yet known whether these influenza viruses with reduced susceptibility are transmissible, and whether surveillance for I38T and other markers will be needed. We also need trials to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from baloxavir, and the timing for treatment.

Timothy M. Uyeki, MD, is with the Influenza Division at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These comments are taken from an editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018;397:975-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1810815. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A new single-dose influenza antiviral drug appears significantly better than placebo at relieving the symptoms of infection, and reduces viral load faster than does oseltamivir, new research suggests.

Baloxavir marboxil – a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease – was tested in two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials. The first was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 randomized trial of 389 Japanese adults aged 20-64 years with acute uncomplicated influenza from December 2015 through March 2016. The second was a phase 3 randomized controlled trial of 1,366 patients comparing baloxavir with placebo and oseltamivir.

The phase 2 study showed patients treated with 10 mg, 20 mg or 40 mg oral dose of baloxavir experienced a significantly shorter median time to symptom alleviation compared with placebo (54.2, 51, 49.5, and 77.7 hours, respectively), according to a paper published in the Sept. 6 edition of the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition, all three doses showed significantly greater reductions in influenza virus titers on days 2 and 3, compared with placebo.

The phase 3 trial CAPSTONE-1 (NCT02954354) was a double-blind, placebo- and oseltamivir-controlled, randomized trial that enrolled outpatients aged 12-64 years with influenza-like illness in the United States and Japan from December 2016 through March 2017. Patients aged 20-64 years received a single, weight-based oral dose of baloxavir (40 mg for patients weighing more than 80 kg, 80 mg for those weighing 80 kg or less) on day 1 only or oseltamivir at a dose of 75 mg twice daily or matching placebos on a 5-day regimen.

Patients aged 12-19 years were randomly assigned to receive either baloxavir or placebo on day 1 only, according to the researchers.

The median time to alleviation of symptoms was similar in the baloxavir (53.5 hours) and oseltamivir group (53.8 hours). However, patients taking baloxavir had significantly faster declines in infectious viral load compared with those taking oseltamivir, which was taken as a 75-mg dose twice daily for 5 days. In addition, patients who were treated with baloxavir within 24 hours of symptom onset showed significantly shorter time to alleviation of symptoms compared with placebo than did those who started treatment more than 24 hours after symptoms began.

Adverse events related to the study drug were more common among patients taking oseltamivir (8.4%) compared with those taking baloxavir (4.4%) or placebo (3.9%). In the phase 2 study, the adverse event rate was lower in the three baloxavir dosage groups compared with the placebo group. The study also showed a similar low frequency of complications requiring antibiotic treatment in both the baloxavir, oseltamivir, and placebo arms.

Some patients did show evidence of decreased susceptibility to baloxavir; for example, PA I38T/M amino acid substitutions were seen in 9.7% of the patients taking baloxavir but none of randomly selected patients in the placebo group of the phase 3 trial.

“These trials showed that single doses of the cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir were superior to placebo in alleviating influenza symptoms in patients with uncomplicated influenza, without clinically significant side effects,” wrote Dr. Frederick G. Hayden of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and his coauthors.

“The antiviral effects that were observed with baloxavir in patients with uncomplicated influenza provide encouragement with respect to its potential value in treating complicated or severe influenza infections,” they noted.

Because the treatment was inhibitory for influenza virus strains that were resistant to neuraminidase inhibitors or M2 ion-channel inhibitors, it could be a treatment option for patients infected with those viruses, the researchers added.

CAPSTONE-2, a randomized, controlled trial involving patients at high risk for influenza complications (NCT02949011) is in progress.

The study was supported by Shionogi, which developed baloxavir. Seven authors declared fees from the pharmaceutical industry, including Shionogi. Six authors were employees of Shionogi, one also holding stock. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Hayden F et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:913-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716197.

A new single-dose influenza antiviral drug appears significantly better than placebo at relieving the symptoms of infection, and reduces viral load faster than does oseltamivir, new research suggests.

Baloxavir marboxil – a selective inhibitor of influenza cap-dependent endonuclease – was tested in two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials. The first was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 randomized trial of 389 Japanese adults aged 20-64 years with acute uncomplicated influenza from December 2015 through March 2016. The second was a phase 3 randomized controlled trial of 1,366 patients comparing baloxavir with placebo and oseltamivir.

The phase 2 study showed patients treated with 10 mg, 20 mg or 40 mg oral dose of baloxavir experienced a significantly shorter median time to symptom alleviation compared with placebo (54.2, 51, 49.5, and 77.7 hours, respectively), according to a paper published in the Sept. 6 edition of the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition, all three doses showed significantly greater reductions in influenza virus titers on days 2 and 3, compared with placebo.

The phase 3 trial CAPSTONE-1 (NCT02954354) was a double-blind, placebo- and oseltamivir-controlled, randomized trial that enrolled outpatients aged 12-64 years with influenza-like illness in the United States and Japan from December 2016 through March 2017. Patients aged 20-64 years received a single, weight-based oral dose of baloxavir (40 mg for patients weighing more than 80 kg, 80 mg for those weighing 80 kg or less) on day 1 only or oseltamivir at a dose of 75 mg twice daily or matching placebos on a 5-day regimen.

Patients aged 12-19 years were randomly assigned to receive either baloxavir or placebo on day 1 only, according to the researchers.

The median time to alleviation of symptoms was similar in the baloxavir (53.5 hours) and oseltamivir group (53.8 hours). However, patients taking baloxavir had significantly faster declines in infectious viral load compared with those taking oseltamivir, which was taken as a 75-mg dose twice daily for 5 days. In addition, patients who were treated with baloxavir within 24 hours of symptom onset showed significantly shorter time to alleviation of symptoms compared with placebo than did those who started treatment more than 24 hours after symptoms began.