User login

CDC releases guidelines for pediatric mTBI

and should base management and prognostication on clinical decision-making tools and symptom rating scales, according to new practice guidelines issued by a working group of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2853.

The guidelines were released simultaneously with a systematic review, conducted by the same authors, of the existing literature regarding pediatric mTBI (JAMA Pediatrics 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2847). As the evaluators sorted through the literature to find high-quality studies for this population, the funnel rapidly narrowed: From an initial pool of over 15,000 studies conducted between 1990 and 2015, findings from just 75 studies were eventually included in the systematic review.

The review’s findings formed the basis for the guidelines and allowed Angela Lumba-Brown, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Stanford (Calif.) University, and her coauthors to ascribe a level of confidence in the inference from study data for a given recommendation. Recommendations also are categorized by strength and accordingly indicate that clinicians “should” or “may” follow them. Exceptions are carved out for practices, such as the use of hypertonic 3% saline solution for acute headache in the ED, that should not be used outside research settings.

In the end, the guidelines cover 19 main topics, sorted into guidance regarding the diagnosis, prognosis, and management and treatment of mTBI in children.

Diagnosis

The recommendations regarding mTBI diagnosis center around determining which children are at risk for significant intracranial injury (ICI). The guidelines recommend, with moderate confidence, that clinicians usually should not obtain a head CT for children with mTBI. Validated clinical decision rules should be used for risk stratification to determine which children can safely avoid imaging and which children should be considered for head CT, wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors. Magnetic resonance imaging is not recommended for initial evaluation of mTBI, nor should skull radiographs be ordered in the absence of clinical suspicion for skull fracture.

From the systematic review, Dr. Lumba-Brown and her colleagues found that several risk factors taken together may mean that significant ICI is more likely. These include patient age younger than 2 years; any vomiting, loss of consciousness, or amnesia; a severe mechanism of injury, severe or worsening headache, or nonfrontal scalp hematoma; a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of less than 15; and clinical suspicion for skull fracture. Clinicians should give consideration to the risks of ionizing radiation to the head, and balance this against their assessment of risk for severe – and perhaps actionable – injury.

A validated symptom rating scale, used in an age-appropriate way, should be used as part of the evaluation of children with mTBI. For children aged 6 and older, the Graded Symptom Checklist is an appropriate tool within 2 days after injury, while the Post Concussion Symptom Scale as part of computerized neurocognitive testing can differentiate which high school athletes have mTBI when used within 4 days of injury, according to the guidelines, which also identify other validated symptom rating scales.

The guidelines authors recommend, with high confidence, that serum biomarkers should not be used outside of research settings in the diagnosis of mTBI in children at present.

Prognosis

Families should be counseled that symptoms mostly resolve within 1-3 months for up to 80% of children with mTBI, but families also should know that “each child’s recovery from mTBI is unique and will follow its own trajectory,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors, in a moderate-strength recommendation.

Some factors have been associated with slower recovery from mTBI, and either upon evaluation for mTBI or in routine sports examinations, families should be told about this potential if risk factors are present, said the guidelines, although the evidence supporting the associations is of “varying strength,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors. Children with previous mTBIs and those with a history of premorbid neurologic and psychiatric problems, learning problems, or family and social stress all may have delayed recovery. For children with ICI, lower cognitive ability also is associated with delayed recovery.

Demographic factors such as lower socioeconomic status and being of Hispanic ethnicity also may increase the risk for delayed mTBI recovery. Older children and adolescents may recover more slowly. Those with more severe initial presentation and more symptoms in the immediate post-mTBI phase also may have a slower recovery course, said Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

A validated prediction rule can be used in the ED to gather information about these discrete risk factors to guide family counseling, according to the guidelines, which note that research has found that “an empirically derived set of risk factors predicted the risk of persistent post-concussion symptoms at 28 days” for children seen in the ED with mTBI.

During the recovery phase, a combination of tools should be used to track recovery from mTBI; these can include validated symptom scales, validated cognitive testing, reaction time measures, and, in adolescent athletes, balance testing. Using a combination of tools is a valuable strategy, the researchers wrote. “No single assessment tool is strongly predictive of outcome in children with mTBI,” they noted.

When prognosis is poor, or recovery is not proceeding as expected, clinicians should have a low threshold for initiating other interventions and referrals.

Management and treatment

Although the guideline authors acknowledged significant knowledge gaps in all areas of pediatric mTBI diagnosis and management, evidence is especially scant for best practices for treatment, rest, and return to play and school after a child sustains mTBI, said Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

However, families should be given information about warning signs for serious head injury and how to monitor symptoms, as well as information about mTBI and the expected recovery course. Other forward-looking instructions should cover the importance of preventing new head injuries, managing the gradual return to normal cognitive and physical activities, and clear instructions regarding return to school and recreational activities. The guideline authors made a strong recommendation to provide this information, with high confidence in the data.

However, little strong evidence points the way to a clear set of criteria for when children are ready for school, play, and athletic participation. These decisions must be customized to the individual child, and decision making, particularly about return to school and academic activities, should be a collaborative affair, with schools, clinicians, and families all communicating to make sure the pace of return to normal life is keeping pace with the child’s recovery. “Because postconcussive symptoms resolve at different rates in different children after mTBI, individualization of return-to-school programming is necessary,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

The guideline authors cite evidence that “suggests that early rest (within the first 3 days) may be beneficial but that inactivity beyond this period for most children may worsen their self-reported symptoms.”

Psychosocial support may be beneficial for certain children, wrote the researchers, drawing on evidence showing that such support is beneficial in frank TBI, and is probably beneficial in mTBI.

Active rehabilitation as tolerated is recommended after an initial period of rest, with exertion kept to a level that does not exacerbate symptoms. Children should not participate in contact activities until symptoms are fully resolved.

A posttraumatic headache that is severe or worsens in the ED should prompt consideration of emergent neuroimaging, according to the guidelines. In the postacute phase, however, children can have nonopioid analgesia, although parents should know about such risks as rebound headache. When chronic headache follows a mTBI, the guidelines recommend that clinicians refer patients for a multidisciplinary evaluation that can assess the many factors – including analgesic overuse – that can be contributors.

Drawing on the larger body of adult TBI research, the authors recommend that insufficient or disordered sleep be addressed, because “the maintenance of appropriate sleep and the management of disrupted sleep may be a critical target of treatment for the child with mTBI.”

Children who suffer a mTBI may experience cognitive dysfunction as a direct result of injury to the brain or secondary to the effects of other symptoms such as sleep disruptions, headache pain, fatigue, or low tolerance of frustration. Clinicians may want to perform or refer their patients for a neuropsychological evaluation to determine what is causing the cognitive dysfunction, the authors said.

Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors, who formed the CDC’s Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Guideline Workgroup, also recommended that clinicians use the term “mild traumatic brain injury” to describe head injuries that cause confusion or disorientation, without loss of consciousness, or loss of consciousness of up to 30 minutes or less, or posttraumatic amnesia of less than 24 hours duration, and that are associated with a GCS of 13-15 by 30 minutes after injury or at the time of initial medical assessment. This practice, they said, may reduce the risk of misinterpretation by medical professionals and the public that can occur when the terms “mTBI,” “concussion,” and “minor head injury” all may refer to the same injury.

The CDC has developed a suite of materials to assist both health care providers and the public in guideline implementation. The agency also is using its HEADS UP campaign to publicize the guidelines and related materials, and plans ongoing evaluation of the guidelines and implementation materials.

Many study authors, including Dr. Lumba-Brown, had relationships with medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The systematic review and guideline development were funded by the CDC.

A growing realization that mTBI can have persistent and significant deleterious effects has informed medical and public attitudes toward concussion in children, which now results in almost 1 million annual ED visits.

Progress at the laboratory bench has elucidated much of the neurometabolic cascade that occurs with the insult of mTBI, and has allowed researchers to document the path of brain healing after injury. Neuroimaging now can go beyond static images to trace neural networks and detect previously unseen and subtle functional deficits engendered by mTBI.

In particular, 21st century magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown increased sensitivity over CT alone. In the TRACK-TBI study, over one in four patients whose CTs were read as normal had MRI findings consistent with trauma-induced pathology. Both multimodal MRI and serum biomarkers show promise, although more research regarding their utility is needed, particularly in the case of proteomic biomarkers.

Still, high-quality studies of pediatric mTBI are scant, and translation of burgeoning research into clinical practice is severely impeded by the numerous knowledge gaps that exist in the field.

Dr. Lumba-Brown and her colleagues have synthesized research that supports a neurobiopsychosocial model of mTBI in children that comes into play most prominently in the postacute phase, when non–injury-related factors such as demographics, socioeconomic status, and premorbid psychological conditions are strong mediators of the recovery trajectory.

With children as with adults, scant research guides the path forward for treatment and recovery from mTBI. For children, clinicians are still grappling with issues surrounding return to full participation in the academic and recreational activities of the school environment.

Data from two currently active studies should help light the way forward, however. The TRACK-TBI study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, will include almost 200 children among its 2,700 enrollees who have sustained all levels of TBI.

The Concussion Assessment, Research, and Education (CARE) Consortium is funded jointly by the National College Athletic Association and the Department of Defense. Between student athletes and military cadets, over 40,000 individuals are now part of the study.

The two studies’ testing modalities and methodologies align, offering the opportunity for a powerful pooled analysis that includes civilians, athletes, and those in the military.

Until then, these guidelines provide a way forward to an individualized approach to the best care for a child with mTBI.

Michael McCrea, PhD, is professor of neurology and neurosurgery, and director of brain injury research at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Geoff Manley, MD, PhD, is professor of neurologic surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. Neither author reported conflicts of interest. These remarks were drawn from an editorial accompanying the guidelines and systematic review (JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2846).

A growing realization that mTBI can have persistent and significant deleterious effects has informed medical and public attitudes toward concussion in children, which now results in almost 1 million annual ED visits.

Progress at the laboratory bench has elucidated much of the neurometabolic cascade that occurs with the insult of mTBI, and has allowed researchers to document the path of brain healing after injury. Neuroimaging now can go beyond static images to trace neural networks and detect previously unseen and subtle functional deficits engendered by mTBI.

In particular, 21st century magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown increased sensitivity over CT alone. In the TRACK-TBI study, over one in four patients whose CTs were read as normal had MRI findings consistent with trauma-induced pathology. Both multimodal MRI and serum biomarkers show promise, although more research regarding their utility is needed, particularly in the case of proteomic biomarkers.

Still, high-quality studies of pediatric mTBI are scant, and translation of burgeoning research into clinical practice is severely impeded by the numerous knowledge gaps that exist in the field.

Dr. Lumba-Brown and her colleagues have synthesized research that supports a neurobiopsychosocial model of mTBI in children that comes into play most prominently in the postacute phase, when non–injury-related factors such as demographics, socioeconomic status, and premorbid psychological conditions are strong mediators of the recovery trajectory.

With children as with adults, scant research guides the path forward for treatment and recovery from mTBI. For children, clinicians are still grappling with issues surrounding return to full participation in the academic and recreational activities of the school environment.

Data from two currently active studies should help light the way forward, however. The TRACK-TBI study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, will include almost 200 children among its 2,700 enrollees who have sustained all levels of TBI.

The Concussion Assessment, Research, and Education (CARE) Consortium is funded jointly by the National College Athletic Association and the Department of Defense. Between student athletes and military cadets, over 40,000 individuals are now part of the study.

The two studies’ testing modalities and methodologies align, offering the opportunity for a powerful pooled analysis that includes civilians, athletes, and those in the military.

Until then, these guidelines provide a way forward to an individualized approach to the best care for a child with mTBI.

Michael McCrea, PhD, is professor of neurology and neurosurgery, and director of brain injury research at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Geoff Manley, MD, PhD, is professor of neurologic surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. Neither author reported conflicts of interest. These remarks were drawn from an editorial accompanying the guidelines and systematic review (JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2846).

A growing realization that mTBI can have persistent and significant deleterious effects has informed medical and public attitudes toward concussion in children, which now results in almost 1 million annual ED visits.

Progress at the laboratory bench has elucidated much of the neurometabolic cascade that occurs with the insult of mTBI, and has allowed researchers to document the path of brain healing after injury. Neuroimaging now can go beyond static images to trace neural networks and detect previously unseen and subtle functional deficits engendered by mTBI.

In particular, 21st century magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown increased sensitivity over CT alone. In the TRACK-TBI study, over one in four patients whose CTs were read as normal had MRI findings consistent with trauma-induced pathology. Both multimodal MRI and serum biomarkers show promise, although more research regarding their utility is needed, particularly in the case of proteomic biomarkers.

Still, high-quality studies of pediatric mTBI are scant, and translation of burgeoning research into clinical practice is severely impeded by the numerous knowledge gaps that exist in the field.

Dr. Lumba-Brown and her colleagues have synthesized research that supports a neurobiopsychosocial model of mTBI in children that comes into play most prominently in the postacute phase, when non–injury-related factors such as demographics, socioeconomic status, and premorbid psychological conditions are strong mediators of the recovery trajectory.

With children as with adults, scant research guides the path forward for treatment and recovery from mTBI. For children, clinicians are still grappling with issues surrounding return to full participation in the academic and recreational activities of the school environment.

Data from two currently active studies should help light the way forward, however. The TRACK-TBI study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, will include almost 200 children among its 2,700 enrollees who have sustained all levels of TBI.

The Concussion Assessment, Research, and Education (CARE) Consortium is funded jointly by the National College Athletic Association and the Department of Defense. Between student athletes and military cadets, over 40,000 individuals are now part of the study.

The two studies’ testing modalities and methodologies align, offering the opportunity for a powerful pooled analysis that includes civilians, athletes, and those in the military.

Until then, these guidelines provide a way forward to an individualized approach to the best care for a child with mTBI.

Michael McCrea, PhD, is professor of neurology and neurosurgery, and director of brain injury research at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Geoff Manley, MD, PhD, is professor of neurologic surgery at the University of California, San Francisco. Neither author reported conflicts of interest. These remarks were drawn from an editorial accompanying the guidelines and systematic review (JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2846).

and should base management and prognostication on clinical decision-making tools and symptom rating scales, according to new practice guidelines issued by a working group of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2853.

The guidelines were released simultaneously with a systematic review, conducted by the same authors, of the existing literature regarding pediatric mTBI (JAMA Pediatrics 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2847). As the evaluators sorted through the literature to find high-quality studies for this population, the funnel rapidly narrowed: From an initial pool of over 15,000 studies conducted between 1990 and 2015, findings from just 75 studies were eventually included in the systematic review.

The review’s findings formed the basis for the guidelines and allowed Angela Lumba-Brown, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Stanford (Calif.) University, and her coauthors to ascribe a level of confidence in the inference from study data for a given recommendation. Recommendations also are categorized by strength and accordingly indicate that clinicians “should” or “may” follow them. Exceptions are carved out for practices, such as the use of hypertonic 3% saline solution for acute headache in the ED, that should not be used outside research settings.

In the end, the guidelines cover 19 main topics, sorted into guidance regarding the diagnosis, prognosis, and management and treatment of mTBI in children.

Diagnosis

The recommendations regarding mTBI diagnosis center around determining which children are at risk for significant intracranial injury (ICI). The guidelines recommend, with moderate confidence, that clinicians usually should not obtain a head CT for children with mTBI. Validated clinical decision rules should be used for risk stratification to determine which children can safely avoid imaging and which children should be considered for head CT, wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors. Magnetic resonance imaging is not recommended for initial evaluation of mTBI, nor should skull radiographs be ordered in the absence of clinical suspicion for skull fracture.

From the systematic review, Dr. Lumba-Brown and her colleagues found that several risk factors taken together may mean that significant ICI is more likely. These include patient age younger than 2 years; any vomiting, loss of consciousness, or amnesia; a severe mechanism of injury, severe or worsening headache, or nonfrontal scalp hematoma; a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of less than 15; and clinical suspicion for skull fracture. Clinicians should give consideration to the risks of ionizing radiation to the head, and balance this against their assessment of risk for severe – and perhaps actionable – injury.

A validated symptom rating scale, used in an age-appropriate way, should be used as part of the evaluation of children with mTBI. For children aged 6 and older, the Graded Symptom Checklist is an appropriate tool within 2 days after injury, while the Post Concussion Symptom Scale as part of computerized neurocognitive testing can differentiate which high school athletes have mTBI when used within 4 days of injury, according to the guidelines, which also identify other validated symptom rating scales.

The guidelines authors recommend, with high confidence, that serum biomarkers should not be used outside of research settings in the diagnosis of mTBI in children at present.

Prognosis

Families should be counseled that symptoms mostly resolve within 1-3 months for up to 80% of children with mTBI, but families also should know that “each child’s recovery from mTBI is unique and will follow its own trajectory,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors, in a moderate-strength recommendation.

Some factors have been associated with slower recovery from mTBI, and either upon evaluation for mTBI or in routine sports examinations, families should be told about this potential if risk factors are present, said the guidelines, although the evidence supporting the associations is of “varying strength,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors. Children with previous mTBIs and those with a history of premorbid neurologic and psychiatric problems, learning problems, or family and social stress all may have delayed recovery. For children with ICI, lower cognitive ability also is associated with delayed recovery.

Demographic factors such as lower socioeconomic status and being of Hispanic ethnicity also may increase the risk for delayed mTBI recovery. Older children and adolescents may recover more slowly. Those with more severe initial presentation and more symptoms in the immediate post-mTBI phase also may have a slower recovery course, said Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

A validated prediction rule can be used in the ED to gather information about these discrete risk factors to guide family counseling, according to the guidelines, which note that research has found that “an empirically derived set of risk factors predicted the risk of persistent post-concussion symptoms at 28 days” for children seen in the ED with mTBI.

During the recovery phase, a combination of tools should be used to track recovery from mTBI; these can include validated symptom scales, validated cognitive testing, reaction time measures, and, in adolescent athletes, balance testing. Using a combination of tools is a valuable strategy, the researchers wrote. “No single assessment tool is strongly predictive of outcome in children with mTBI,” they noted.

When prognosis is poor, or recovery is not proceeding as expected, clinicians should have a low threshold for initiating other interventions and referrals.

Management and treatment

Although the guideline authors acknowledged significant knowledge gaps in all areas of pediatric mTBI diagnosis and management, evidence is especially scant for best practices for treatment, rest, and return to play and school after a child sustains mTBI, said Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

However, families should be given information about warning signs for serious head injury and how to monitor symptoms, as well as information about mTBI and the expected recovery course. Other forward-looking instructions should cover the importance of preventing new head injuries, managing the gradual return to normal cognitive and physical activities, and clear instructions regarding return to school and recreational activities. The guideline authors made a strong recommendation to provide this information, with high confidence in the data.

However, little strong evidence points the way to a clear set of criteria for when children are ready for school, play, and athletic participation. These decisions must be customized to the individual child, and decision making, particularly about return to school and academic activities, should be a collaborative affair, with schools, clinicians, and families all communicating to make sure the pace of return to normal life is keeping pace with the child’s recovery. “Because postconcussive symptoms resolve at different rates in different children after mTBI, individualization of return-to-school programming is necessary,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

The guideline authors cite evidence that “suggests that early rest (within the first 3 days) may be beneficial but that inactivity beyond this period for most children may worsen their self-reported symptoms.”

Psychosocial support may be beneficial for certain children, wrote the researchers, drawing on evidence showing that such support is beneficial in frank TBI, and is probably beneficial in mTBI.

Active rehabilitation as tolerated is recommended after an initial period of rest, with exertion kept to a level that does not exacerbate symptoms. Children should not participate in contact activities until symptoms are fully resolved.

A posttraumatic headache that is severe or worsens in the ED should prompt consideration of emergent neuroimaging, according to the guidelines. In the postacute phase, however, children can have nonopioid analgesia, although parents should know about such risks as rebound headache. When chronic headache follows a mTBI, the guidelines recommend that clinicians refer patients for a multidisciplinary evaluation that can assess the many factors – including analgesic overuse – that can be contributors.

Drawing on the larger body of adult TBI research, the authors recommend that insufficient or disordered sleep be addressed, because “the maintenance of appropriate sleep and the management of disrupted sleep may be a critical target of treatment for the child with mTBI.”

Children who suffer a mTBI may experience cognitive dysfunction as a direct result of injury to the brain or secondary to the effects of other symptoms such as sleep disruptions, headache pain, fatigue, or low tolerance of frustration. Clinicians may want to perform or refer their patients for a neuropsychological evaluation to determine what is causing the cognitive dysfunction, the authors said.

Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors, who formed the CDC’s Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Guideline Workgroup, also recommended that clinicians use the term “mild traumatic brain injury” to describe head injuries that cause confusion or disorientation, without loss of consciousness, or loss of consciousness of up to 30 minutes or less, or posttraumatic amnesia of less than 24 hours duration, and that are associated with a GCS of 13-15 by 30 minutes after injury or at the time of initial medical assessment. This practice, they said, may reduce the risk of misinterpretation by medical professionals and the public that can occur when the terms “mTBI,” “concussion,” and “minor head injury” all may refer to the same injury.

The CDC has developed a suite of materials to assist both health care providers and the public in guideline implementation. The agency also is using its HEADS UP campaign to publicize the guidelines and related materials, and plans ongoing evaluation of the guidelines and implementation materials.

Many study authors, including Dr. Lumba-Brown, had relationships with medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The systematic review and guideline development were funded by the CDC.

and should base management and prognostication on clinical decision-making tools and symptom rating scales, according to new practice guidelines issued by a working group of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (JAMA Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2853.

The guidelines were released simultaneously with a systematic review, conducted by the same authors, of the existing literature regarding pediatric mTBI (JAMA Pediatrics 2018 Sep 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2847). As the evaluators sorted through the literature to find high-quality studies for this population, the funnel rapidly narrowed: From an initial pool of over 15,000 studies conducted between 1990 and 2015, findings from just 75 studies were eventually included in the systematic review.

The review’s findings formed the basis for the guidelines and allowed Angela Lumba-Brown, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Stanford (Calif.) University, and her coauthors to ascribe a level of confidence in the inference from study data for a given recommendation. Recommendations also are categorized by strength and accordingly indicate that clinicians “should” or “may” follow them. Exceptions are carved out for practices, such as the use of hypertonic 3% saline solution for acute headache in the ED, that should not be used outside research settings.

In the end, the guidelines cover 19 main topics, sorted into guidance regarding the diagnosis, prognosis, and management and treatment of mTBI in children.

Diagnosis

The recommendations regarding mTBI diagnosis center around determining which children are at risk for significant intracranial injury (ICI). The guidelines recommend, with moderate confidence, that clinicians usually should not obtain a head CT for children with mTBI. Validated clinical decision rules should be used for risk stratification to determine which children can safely avoid imaging and which children should be considered for head CT, wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors. Magnetic resonance imaging is not recommended for initial evaluation of mTBI, nor should skull radiographs be ordered in the absence of clinical suspicion for skull fracture.

From the systematic review, Dr. Lumba-Brown and her colleagues found that several risk factors taken together may mean that significant ICI is more likely. These include patient age younger than 2 years; any vomiting, loss of consciousness, or amnesia; a severe mechanism of injury, severe or worsening headache, or nonfrontal scalp hematoma; a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of less than 15; and clinical suspicion for skull fracture. Clinicians should give consideration to the risks of ionizing radiation to the head, and balance this against their assessment of risk for severe – and perhaps actionable – injury.

A validated symptom rating scale, used in an age-appropriate way, should be used as part of the evaluation of children with mTBI. For children aged 6 and older, the Graded Symptom Checklist is an appropriate tool within 2 days after injury, while the Post Concussion Symptom Scale as part of computerized neurocognitive testing can differentiate which high school athletes have mTBI when used within 4 days of injury, according to the guidelines, which also identify other validated symptom rating scales.

The guidelines authors recommend, with high confidence, that serum biomarkers should not be used outside of research settings in the diagnosis of mTBI in children at present.

Prognosis

Families should be counseled that symptoms mostly resolve within 1-3 months for up to 80% of children with mTBI, but families also should know that “each child’s recovery from mTBI is unique and will follow its own trajectory,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors, in a moderate-strength recommendation.

Some factors have been associated with slower recovery from mTBI, and either upon evaluation for mTBI or in routine sports examinations, families should be told about this potential if risk factors are present, said the guidelines, although the evidence supporting the associations is of “varying strength,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors. Children with previous mTBIs and those with a history of premorbid neurologic and psychiatric problems, learning problems, or family and social stress all may have delayed recovery. For children with ICI, lower cognitive ability also is associated with delayed recovery.

Demographic factors such as lower socioeconomic status and being of Hispanic ethnicity also may increase the risk for delayed mTBI recovery. Older children and adolescents may recover more slowly. Those with more severe initial presentation and more symptoms in the immediate post-mTBI phase also may have a slower recovery course, said Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

A validated prediction rule can be used in the ED to gather information about these discrete risk factors to guide family counseling, according to the guidelines, which note that research has found that “an empirically derived set of risk factors predicted the risk of persistent post-concussion symptoms at 28 days” for children seen in the ED with mTBI.

During the recovery phase, a combination of tools should be used to track recovery from mTBI; these can include validated symptom scales, validated cognitive testing, reaction time measures, and, in adolescent athletes, balance testing. Using a combination of tools is a valuable strategy, the researchers wrote. “No single assessment tool is strongly predictive of outcome in children with mTBI,” they noted.

When prognosis is poor, or recovery is not proceeding as expected, clinicians should have a low threshold for initiating other interventions and referrals.

Management and treatment

Although the guideline authors acknowledged significant knowledge gaps in all areas of pediatric mTBI diagnosis and management, evidence is especially scant for best practices for treatment, rest, and return to play and school after a child sustains mTBI, said Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

However, families should be given information about warning signs for serious head injury and how to monitor symptoms, as well as information about mTBI and the expected recovery course. Other forward-looking instructions should cover the importance of preventing new head injuries, managing the gradual return to normal cognitive and physical activities, and clear instructions regarding return to school and recreational activities. The guideline authors made a strong recommendation to provide this information, with high confidence in the data.

However, little strong evidence points the way to a clear set of criteria for when children are ready for school, play, and athletic participation. These decisions must be customized to the individual child, and decision making, particularly about return to school and academic activities, should be a collaborative affair, with schools, clinicians, and families all communicating to make sure the pace of return to normal life is keeping pace with the child’s recovery. “Because postconcussive symptoms resolve at different rates in different children after mTBI, individualization of return-to-school programming is necessary,” wrote Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors.

The guideline authors cite evidence that “suggests that early rest (within the first 3 days) may be beneficial but that inactivity beyond this period for most children may worsen their self-reported symptoms.”

Psychosocial support may be beneficial for certain children, wrote the researchers, drawing on evidence showing that such support is beneficial in frank TBI, and is probably beneficial in mTBI.

Active rehabilitation as tolerated is recommended after an initial period of rest, with exertion kept to a level that does not exacerbate symptoms. Children should not participate in contact activities until symptoms are fully resolved.

A posttraumatic headache that is severe or worsens in the ED should prompt consideration of emergent neuroimaging, according to the guidelines. In the postacute phase, however, children can have nonopioid analgesia, although parents should know about such risks as rebound headache. When chronic headache follows a mTBI, the guidelines recommend that clinicians refer patients for a multidisciplinary evaluation that can assess the many factors – including analgesic overuse – that can be contributors.

Drawing on the larger body of adult TBI research, the authors recommend that insufficient or disordered sleep be addressed, because “the maintenance of appropriate sleep and the management of disrupted sleep may be a critical target of treatment for the child with mTBI.”

Children who suffer a mTBI may experience cognitive dysfunction as a direct result of injury to the brain or secondary to the effects of other symptoms such as sleep disruptions, headache pain, fatigue, or low tolerance of frustration. Clinicians may want to perform or refer their patients for a neuropsychological evaluation to determine what is causing the cognitive dysfunction, the authors said.

Dr. Lumba-Brown and her coauthors, who formed the CDC’s Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Guideline Workgroup, also recommended that clinicians use the term “mild traumatic brain injury” to describe head injuries that cause confusion or disorientation, without loss of consciousness, or loss of consciousness of up to 30 minutes or less, or posttraumatic amnesia of less than 24 hours duration, and that are associated with a GCS of 13-15 by 30 minutes after injury or at the time of initial medical assessment. This practice, they said, may reduce the risk of misinterpretation by medical professionals and the public that can occur when the terms “mTBI,” “concussion,” and “minor head injury” all may refer to the same injury.

The CDC has developed a suite of materials to assist both health care providers and the public in guideline implementation. The agency also is using its HEADS UP campaign to publicize the guidelines and related materials, and plans ongoing evaluation of the guidelines and implementation materials.

Many study authors, including Dr. Lumba-Brown, had relationships with medical device or pharmaceutical companies. The systematic review and guideline development were funded by the CDC.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

ARRIVE: What are the perinatal and maternal consequences of labor induction at 39 weeks compared with expectant management?

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PRACTICE?

- Induction of labor at 39 weeks in low-risk nulliparas, irrespective of Bishop score, seems to be a reasonable option to be included in route of delivery discussions with patients as part of the principle of shared decision-making.

- The data in this trial would suggest that such an approach not only reduces adverse perinatal outcomes but also may reduce the need for subsequent cesarean delivery.

Updates to EULAR hand OA management recommendations reflect current evidence

Updated EULAR recommendations on the management of hand osteoarthritis include five overarching principles as well as two new recommendations that reflect new research in the field.

The task force, led by Margreet Kloppenburg, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, noted that a decade had passed since the first recommendations were published in 2007.

“It was timely to update the recommendations, as many new studies had emerged during this period. In light of this new evidence, many of the 2007 recommendations were modified and new recommendations were added,” wrote Dr. Kloppenburg and her colleagues. The recommendations were published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They noted that the recommendations were targeted to all health professionals across primary and secondary care but also aimed to inform patients about their disease to “support shared decision making.”

In line with other EULAR sets of management recommendations, the update included five overarching principles that cover treatment goals, information and education for patients, individualization of treatment, shared decision making between clinicians and patients, and the need to take into consideration a multidisciplinary and multimodal (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) treatment approach.

The authors noted that for a long time hand OA was a “forgotten disease” and this was reflected by the paucity of clinical trials in the area. As a direct consequence, previous recommendations were based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

However, new data allowed the task force to recommend not to treat patients with hand OA with conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The recommendation achieved the strongest level of evidence and a high level of agreement from the 19-member expert panel, which included 2 patient research partners. The authors said the recommendation was based on newer studies that demonstrated a lack of efficacy of csDMARDs and bDMARDs.

The authors also advised adapting the long-term follow-up of patients with hand OA to individual needs, although they noted this was based on expert opinion alone and that in the absence of a disease-modifying treatment, the goal of follow-up differs from that of many other rheumatic diseases. Individual needs will dictate the degree of follow-up required, based on the severity of symptoms, presence of erosive disease, reevaluation of the use of pharmacologic therapy, and a patient’s wishes and expectations. They also noted that “for most patients, standard radiographic follow-up is not useful at this moment” and that “follow-up does not necessarily have to be performed by a rheumatologist.

“Follow-up will likely increase adherence to nonpharmacological therapies like exercise or orthoses, and provides an opportunity for reevaluation of treatment,” they wrote.

The recommendations advise offering education and training in ergonomic principles and exercises to patients to improve function and muscle strength, as well as considering the use of orthoses in some patients.

Treatment recommendations suggested preferring topical treatments over systemic treatments and that oral analgesics, particularly NSAIDs, should be considered for a limited duration. The authors advised that chondroitin sulfate may be used in patients for pain relief and improvement in functioning and that intra-articular glucocorticoids should not generally be used but may be considered in patients with painful interphalangeal joints. Surgery should be considered for patients with structural abnormalities when other treatment modalities have not been sufficiently effective in relieving pain.

The recommendations were funded by EULAR. Several of the authors reported receiving consultancy fees and/or honoraria as well as research funding from industry.

SOURCE: Kloppenburg M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826.

EULAR has updated its 2007 guidelines for the management of hand osteoarthritis. I find the recommendations helpful, and I have no disagreements.

The authors performed a systematic literature review that was more complete than the original guidelines. In addition, the methodology in developing the guidelines was updated utilizing the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) system to guide the expert opinion. The manuscript presents recommendations that are carefully supported in the text. To understand guidelines, one really needs to read the text.

The update lists a set of research questions, similar to the 2007 recommendations.

The authors group their therapeutic recommendations according to nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches, as well as about the need for follow-up. The three nonpharmacologic recommendations include education and training, exercise and muscle strengthening, and the use of orthoses. The pharmacologic approach includes topical therapy as a first-line, oral NSAIDs and analgesics, chondroitin sulfate, and intra-articular injections. There is a negative recommendation for the use of biologics. The surgical recommendation is directed at the relief of pain. The last recommendation emphasizes the need for follow-up and individual care.

The differences between the recommendations include the removal of acetaminophen as a first-line therapy. Indeed, it seems to be barely recommended at all. In addition, there is an emphasis on topical therapy, particularly NSAIDs. The authors are equivocal on the recommendations for intra-articular therapy. Paraffin and local heat are no longer included. The recommendation against biologic therapy is new. They included agents used for rheumatoid arthritis, such as methotrexate, in this negative recommendation.

These new recommendations are an update of guidelines that are over 10 years old. They are practical and helpful. Unfortunately, more research is needed as the present day therapy is often inadequate.

Roy D. Altman, MD, is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is a consultant to Ferring, Flexion, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Olatec, Pfizer, and Sorrento Therapeutics.

EULAR has updated its 2007 guidelines for the management of hand osteoarthritis. I find the recommendations helpful, and I have no disagreements.

The authors performed a systematic literature review that was more complete than the original guidelines. In addition, the methodology in developing the guidelines was updated utilizing the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) system to guide the expert opinion. The manuscript presents recommendations that are carefully supported in the text. To understand guidelines, one really needs to read the text.

The update lists a set of research questions, similar to the 2007 recommendations.

The authors group their therapeutic recommendations according to nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches, as well as about the need for follow-up. The three nonpharmacologic recommendations include education and training, exercise and muscle strengthening, and the use of orthoses. The pharmacologic approach includes topical therapy as a first-line, oral NSAIDs and analgesics, chondroitin sulfate, and intra-articular injections. There is a negative recommendation for the use of biologics. The surgical recommendation is directed at the relief of pain. The last recommendation emphasizes the need for follow-up and individual care.

The differences between the recommendations include the removal of acetaminophen as a first-line therapy. Indeed, it seems to be barely recommended at all. In addition, there is an emphasis on topical therapy, particularly NSAIDs. The authors are equivocal on the recommendations for intra-articular therapy. Paraffin and local heat are no longer included. The recommendation against biologic therapy is new. They included agents used for rheumatoid arthritis, such as methotrexate, in this negative recommendation.

These new recommendations are an update of guidelines that are over 10 years old. They are practical and helpful. Unfortunately, more research is needed as the present day therapy is often inadequate.

Roy D. Altman, MD, is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is a consultant to Ferring, Flexion, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Olatec, Pfizer, and Sorrento Therapeutics.

EULAR has updated its 2007 guidelines for the management of hand osteoarthritis. I find the recommendations helpful, and I have no disagreements.

The authors performed a systematic literature review that was more complete than the original guidelines. In addition, the methodology in developing the guidelines was updated utilizing the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) system to guide the expert opinion. The manuscript presents recommendations that are carefully supported in the text. To understand guidelines, one really needs to read the text.

The update lists a set of research questions, similar to the 2007 recommendations.

The authors group their therapeutic recommendations according to nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, and surgical approaches, as well as about the need for follow-up. The three nonpharmacologic recommendations include education and training, exercise and muscle strengthening, and the use of orthoses. The pharmacologic approach includes topical therapy as a first-line, oral NSAIDs and analgesics, chondroitin sulfate, and intra-articular injections. There is a negative recommendation for the use of biologics. The surgical recommendation is directed at the relief of pain. The last recommendation emphasizes the need for follow-up and individual care.

The differences between the recommendations include the removal of acetaminophen as a first-line therapy. Indeed, it seems to be barely recommended at all. In addition, there is an emphasis on topical therapy, particularly NSAIDs. The authors are equivocal on the recommendations for intra-articular therapy. Paraffin and local heat are no longer included. The recommendation against biologic therapy is new. They included agents used for rheumatoid arthritis, such as methotrexate, in this negative recommendation.

These new recommendations are an update of guidelines that are over 10 years old. They are practical and helpful. Unfortunately, more research is needed as the present day therapy is often inadequate.

Roy D. Altman, MD, is professor emeritus of medicine in the division of rheumatology and immunology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is a consultant to Ferring, Flexion, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Olatec, Pfizer, and Sorrento Therapeutics.

Updated EULAR recommendations on the management of hand osteoarthritis include five overarching principles as well as two new recommendations that reflect new research in the field.

The task force, led by Margreet Kloppenburg, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, noted that a decade had passed since the first recommendations were published in 2007.

“It was timely to update the recommendations, as many new studies had emerged during this period. In light of this new evidence, many of the 2007 recommendations were modified and new recommendations were added,” wrote Dr. Kloppenburg and her colleagues. The recommendations were published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They noted that the recommendations were targeted to all health professionals across primary and secondary care but also aimed to inform patients about their disease to “support shared decision making.”

In line with other EULAR sets of management recommendations, the update included five overarching principles that cover treatment goals, information and education for patients, individualization of treatment, shared decision making between clinicians and patients, and the need to take into consideration a multidisciplinary and multimodal (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) treatment approach.

The authors noted that for a long time hand OA was a “forgotten disease” and this was reflected by the paucity of clinical trials in the area. As a direct consequence, previous recommendations were based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

However, new data allowed the task force to recommend not to treat patients with hand OA with conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The recommendation achieved the strongest level of evidence and a high level of agreement from the 19-member expert panel, which included 2 patient research partners. The authors said the recommendation was based on newer studies that demonstrated a lack of efficacy of csDMARDs and bDMARDs.

The authors also advised adapting the long-term follow-up of patients with hand OA to individual needs, although they noted this was based on expert opinion alone and that in the absence of a disease-modifying treatment, the goal of follow-up differs from that of many other rheumatic diseases. Individual needs will dictate the degree of follow-up required, based on the severity of symptoms, presence of erosive disease, reevaluation of the use of pharmacologic therapy, and a patient’s wishes and expectations. They also noted that “for most patients, standard radiographic follow-up is not useful at this moment” and that “follow-up does not necessarily have to be performed by a rheumatologist.

“Follow-up will likely increase adherence to nonpharmacological therapies like exercise or orthoses, and provides an opportunity for reevaluation of treatment,” they wrote.

The recommendations advise offering education and training in ergonomic principles and exercises to patients to improve function and muscle strength, as well as considering the use of orthoses in some patients.

Treatment recommendations suggested preferring topical treatments over systemic treatments and that oral analgesics, particularly NSAIDs, should be considered for a limited duration. The authors advised that chondroitin sulfate may be used in patients for pain relief and improvement in functioning and that intra-articular glucocorticoids should not generally be used but may be considered in patients with painful interphalangeal joints. Surgery should be considered for patients with structural abnormalities when other treatment modalities have not been sufficiently effective in relieving pain.

The recommendations were funded by EULAR. Several of the authors reported receiving consultancy fees and/or honoraria as well as research funding from industry.

SOURCE: Kloppenburg M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826.

Updated EULAR recommendations on the management of hand osteoarthritis include five overarching principles as well as two new recommendations that reflect new research in the field.

The task force, led by Margreet Kloppenburg, MD, PhD, of the department of rheumatology at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, noted that a decade had passed since the first recommendations were published in 2007.

“It was timely to update the recommendations, as many new studies had emerged during this period. In light of this new evidence, many of the 2007 recommendations were modified and new recommendations were added,” wrote Dr. Kloppenburg and her colleagues. The recommendations were published online in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

They noted that the recommendations were targeted to all health professionals across primary and secondary care but also aimed to inform patients about their disease to “support shared decision making.”

In line with other EULAR sets of management recommendations, the update included five overarching principles that cover treatment goals, information and education for patients, individualization of treatment, shared decision making between clinicians and patients, and the need to take into consideration a multidisciplinary and multimodal (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) treatment approach.

The authors noted that for a long time hand OA was a “forgotten disease” and this was reflected by the paucity of clinical trials in the area. As a direct consequence, previous recommendations were based on expert opinion rather than evidence.

However, new data allowed the task force to recommend not to treat patients with hand OA with conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). The recommendation achieved the strongest level of evidence and a high level of agreement from the 19-member expert panel, which included 2 patient research partners. The authors said the recommendation was based on newer studies that demonstrated a lack of efficacy of csDMARDs and bDMARDs.

The authors also advised adapting the long-term follow-up of patients with hand OA to individual needs, although they noted this was based on expert opinion alone and that in the absence of a disease-modifying treatment, the goal of follow-up differs from that of many other rheumatic diseases. Individual needs will dictate the degree of follow-up required, based on the severity of symptoms, presence of erosive disease, reevaluation of the use of pharmacologic therapy, and a patient’s wishes and expectations. They also noted that “for most patients, standard radiographic follow-up is not useful at this moment” and that “follow-up does not necessarily have to be performed by a rheumatologist.

“Follow-up will likely increase adherence to nonpharmacological therapies like exercise or orthoses, and provides an opportunity for reevaluation of treatment,” they wrote.

The recommendations advise offering education and training in ergonomic principles and exercises to patients to improve function and muscle strength, as well as considering the use of orthoses in some patients.

Treatment recommendations suggested preferring topical treatments over systemic treatments and that oral analgesics, particularly NSAIDs, should be considered for a limited duration. The authors advised that chondroitin sulfate may be used in patients for pain relief and improvement in functioning and that intra-articular glucocorticoids should not generally be used but may be considered in patients with painful interphalangeal joints. Surgery should be considered for patients with structural abnormalities when other treatment modalities have not been sufficiently effective in relieving pain.

The recommendations were funded by EULAR. Several of the authors reported receiving consultancy fees and/or honoraria as well as research funding from industry.

SOURCE: Kloppenburg M et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Benign MS is real in small minority of patients

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

Nearly 3% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are estimated to have a truly benign course of disease over at least 15 years without the use of disease-modifying therapy, based on findings from a U.K. population-based study that also showed how poorly benign disease tracks with disability measures and lacks agreement between patients and physicians.

“The study of the individuals with extremely favorable outcomes may uncover insights about disease pathogenesis or repair. However, the insensitivity of EDSS [Expanded Disability Status Scale]–based definitions of benign MS and the discrepancy between patient and clinician perception of benign MS undermine use of the term ‘benign’ in the clinical setting,” Emma Clare Tallantyre, MD, of Cardiff (Wales) University, and her colleagues wrote in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Dr. Tallantyre and her colleagues found that, of 1,049 patients with disease duration longer than 15 years, 200 had a recent EDSS score of less than 4.0. Of those 200, 60 were clinically assessed and 9 (15%) were found to have truly benign MS, defined as having an EDSS less than 3.0 and having no significant fatigue, mood disturbance, cognitive impairment, or disruption to employment in the absence of disease-modifying therapy at least 15 years after symptom onset.

The investigators extrapolated these data to estimate that 30 patients in the study population of 1,049 had truly benign MS, for a prevalence of 2.9%. However, of the 60 patients who were clinically assessed, 39 thought they had benign MS based on the lay definition provided: “When referring to illness, ‘benign’ usually means a condition which has little or no harmful effects on a person. There are no complications and there is a good outcome or prognosis.”

Patients who self-reported benign MS had significantly lower EDSS scores, fewer depressive symptoms, lower fatigue severity, and lower reported MS impact than did patients who did not report benign MS. “Self-reported benign MS status showed poor agreement with our composite definition of benign MS status and only fair agreement with EDSS-based definitions of benign MS status,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Tallantyre EC et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318802.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY, NEUROSURGERY & PSYCHIATRY

Time-to-Surgery for Definitive Fixation of Hip Fractures: A Look at Outcomes Based Upon Delay

ABSTRACT

The morbidity and mortality after hip fracture in the elderly are influenced by non-modifiable comorbidities. Time-to-surgery is a modifiable factor that may play a role in postoperative morbidity. This study investigates the outcomes and complications in the elderly hip fracture surgery as a function of time-to-surgery.

Using the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data from 2011 to 2012, a study population was generated using the Current Procedural Terminology codes for percutaneous or open treatment of femoral neck fractures (27235, 27236) and fixation with a screw and side plate or intramedullary fixation (27244, 27245) for peritrochanteric fractures. Three time-to-surgery groups (<24 hours to surgical intervention, 24-48 hours, and >48 hours) were created and matched for surgery type, sex, age, and American Society of Anesthesiologists class. Time-to-surgery was then studied for its effect on the post-surgical outcomes using the adjusted regression modeling.

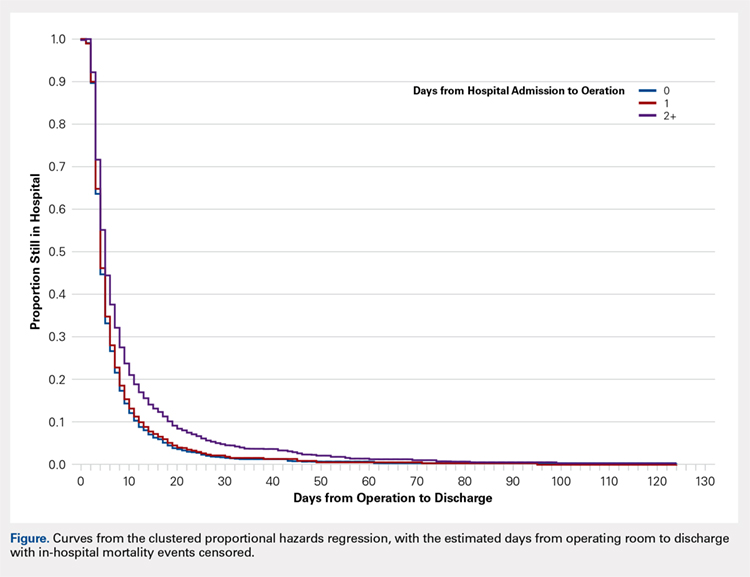

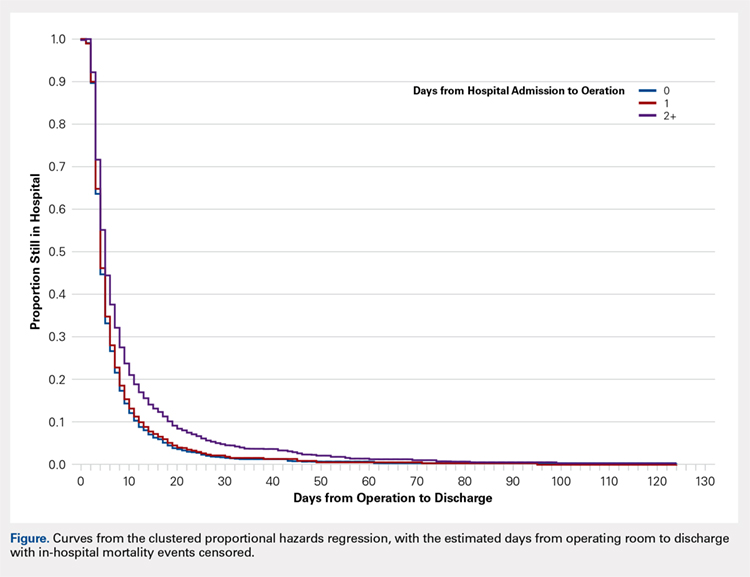

A study population of 6036 hip fractures was created, and 2012 patients were assigned to each matched time-to-surgery group. The unadjusted models showed that the earlier surgical intervention groups (<24 hours and 24-48 hours) exhibited a lower overall complication rate (P = .034) compared with the group waiting for surgery >48 hours. The unadjusted mortality rates increased with delay to surgical intervention (P = .039). Time-to-surgery caused no effect on the return to the operating room rate (P = .554) nor readmission rate (P = .285). Compared with other time-to-surgeries, the time-to-surgery of >48 hours was associated with prolonged total hospital length of stay (10.9 days) (P < .001) and a longer surgery-to-discharge time (hazard ratio, 95% confidence interval: 0.74, 0.69-0.79) (P < .001). Adjusted analyses showed no time-to-surgery related difference in complications (P = .143) but presented an increase in the total length of stay (P < .001) and surgery-to-discharge time (P < .001).

Timeliness of surgical intervention in a comorbidity-adjusted population of elderly hip fracture patients causes no effect on the overall complications, readmissions, nor 30-day mortality. However, time-to-surgery of >48 hours is associated with costly increase in the total length of stay, including an increased post-surgery-to-discharge time.

Continue to: Despite the best efforts to optimize surgical care...

Despite the best efforts to optimize surgical care and postoperative rehabilitation following hip fracture, elderly patients feature alarmingly high in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates of 4.35% to 9.2%1-4 and 36%,5 respectively. Those who survive are unlikely to return to independent living, with only 17% of the patients following hip fracture being able to walk independently 6 months postoperatively, and 12% being able to climb stairs6. Possibly, these poor outcomes reflect a preoperative medical comorbidity burden rather than a measure of medical or surgical quality. Given the absence of consensus regarding optimal time-to-surgery, treating physicians often opt to delay surgical intervention for the purposes of medically optimizing highly comorbid patients without significant data to suggest clinical benefit of such practice.

Numerous investigators have attempted to identify the modifiable risk factors for complication after surgical care of elderly hip fracture patients. However, consensus guidelines of care are missing. This condition is largely due to the difficulties in effectively modifying preoperative demographic and medical comorbidities on a semi-urgent basis. However, timeliness to surgery is one area for study that the care team can affect. Although time-to-surgery is dependent on multiple factors, including time of presentation, day of week of admission, difficulties with scheduling, and administrative delays, the care team plays a role in hastening or retarding time-to-surgery. Several studies have considered various time cut-offs (24, 48, 72, and 120 hours) to define early intervention, but none have defined a specific role for early or delayed surgery. Several investigators have discovered a positive association between delayed time-to-surgery and mortality;4,8-14 however, the most rigorously conducted studies that stringently control for preoperative comorbidities and demographics conclude that variance in time-to-surgery causes no effect on the in-hospital or 1-year mortality risk.1-3,15-18

Other investigators have shown that with early surgical intervention for hip fracture, patients experience shorter hospital stays,1,3,16,17,19-22 less days in pain,19 decreased risk of decubitus ulcers,15,17,19,22 and an increased likelihood of independence following fracture,22-25 regardless of preoperative medical status. Despite this evidence of improved outcomes with early surgery, 40% to 54% of hip fracture patients in the United States experience surgical delays of more than 24 to 48 hours. Additionally, with the recent (2013) national estimates of cost per day spent in the hospital falling between $1791 to $2289,26 minimizing the days spent in the hospital would likely lead to significant cost-savings, presuming no adverse effect on health-related outcomes. To this end, we hypothesize that the value (outcomes per associated cost)7 of hip fracture surgical care can be positively influenced by minimizing surgical wait-times. We assessed the effect of early surgical intervention, within 24 or 48 hours of presentation, on 30-day mortality, postoperative morbidity, hospital length of stay, and readmission rates in a comorbidity-adjusted population from a nationally representative cohort.

Continue to: METHODS AND MATERIALS...

METHODS AND MATERIALS

This study used the data from the American College of Surgeon-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database. With over 258 participating hospitals, this database has been widely used to identify national trends in various surgical specialties.27-34 The database includes information from participants in 43 states with hospitals ranging from rural community hospitals to large academic centers. Each site employs surgical clinical reviewers who are rigorously trained to collect data through chart review and discussion with the treating surgeon and/or patient,35 allowing for the use of robust and quality data with proven inter-rater reliability.36,37

Using the 2011 to 2012 NSQIP database, we used primary Current Procedural Terminology codes to identify all patients who underwent percutaneous (27235) or open (27236) fixation of femoral neck fractures; and fixation with a screw and side plate (27244) or intramedullary fixation (27245) for peritrochanteric fractures. The sample was divided into 3 time-to-surgery groups (<24 hours from presentation to surgery, 24-48 hours, and >48 hours) which were matched for fracture type (femoral neck or peritrochanteric), sex, age (under 75 years or ≥75 years), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class used as a surrogate for severity of medical infirmary. The subjects were randomly matched 1:1:1 to create 3 statistically equivalent time-to-surgery groups using Proc SurveySelect (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute).

Generalized linear models using logit link function for binary variables and identity link function for normally distributed characteristics were used to compare the 3 time-to-surgery groups. Descriptive statistics are presented as counts and percentages or least-square means with standard deviations. Preoperative lab values that were not normally distributed were log transformed and presented in their original scales with median values and 25th to 75th percentiles. Outcomes were similarly modeled.

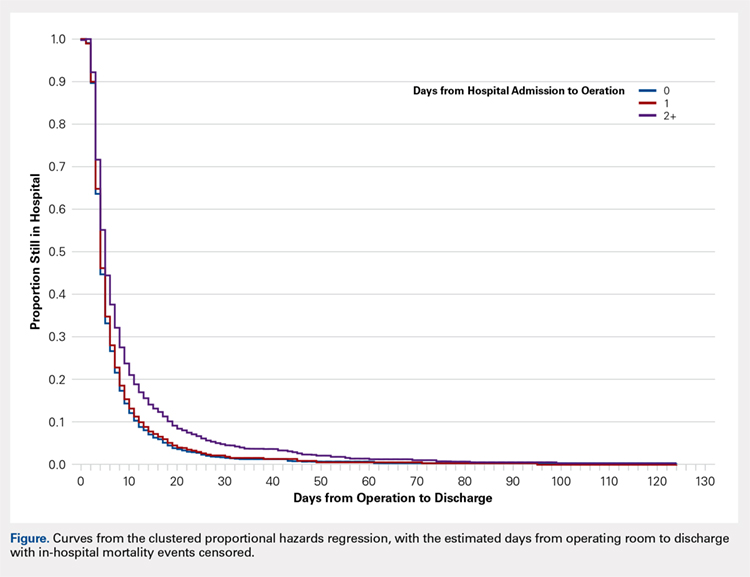

Total hospital stay was modeled with a negative binomial distribution. Proportional hazards models were used to model the time from operating room (OR) to discharge, censoring patients who died before discharge, with results presented as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) (Figure). The assumption of the proportional hazards was tested using a Wald test. Using this model, a HR of <1 denotes a longer postoperative hospital stay, as a longer hospital stay decreases the “risk” for discharge.

All models were adjusted for confounders, including race, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, bleeding disorders, transfusion within 72 hours before surgery, preoperative levels of creatinine, platelet count, white blood cells (WBCs), hematocrit anesthesia type, and wound infection. These covariates were selected based upon their observed relationship to the studied outcomes and time-to-surgery groups, and were evaluated across the models for all outcomes for consistency and clarity. All statistical analyses were run at a type I error rate of 5% and performed in SAS version 9.2 software.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

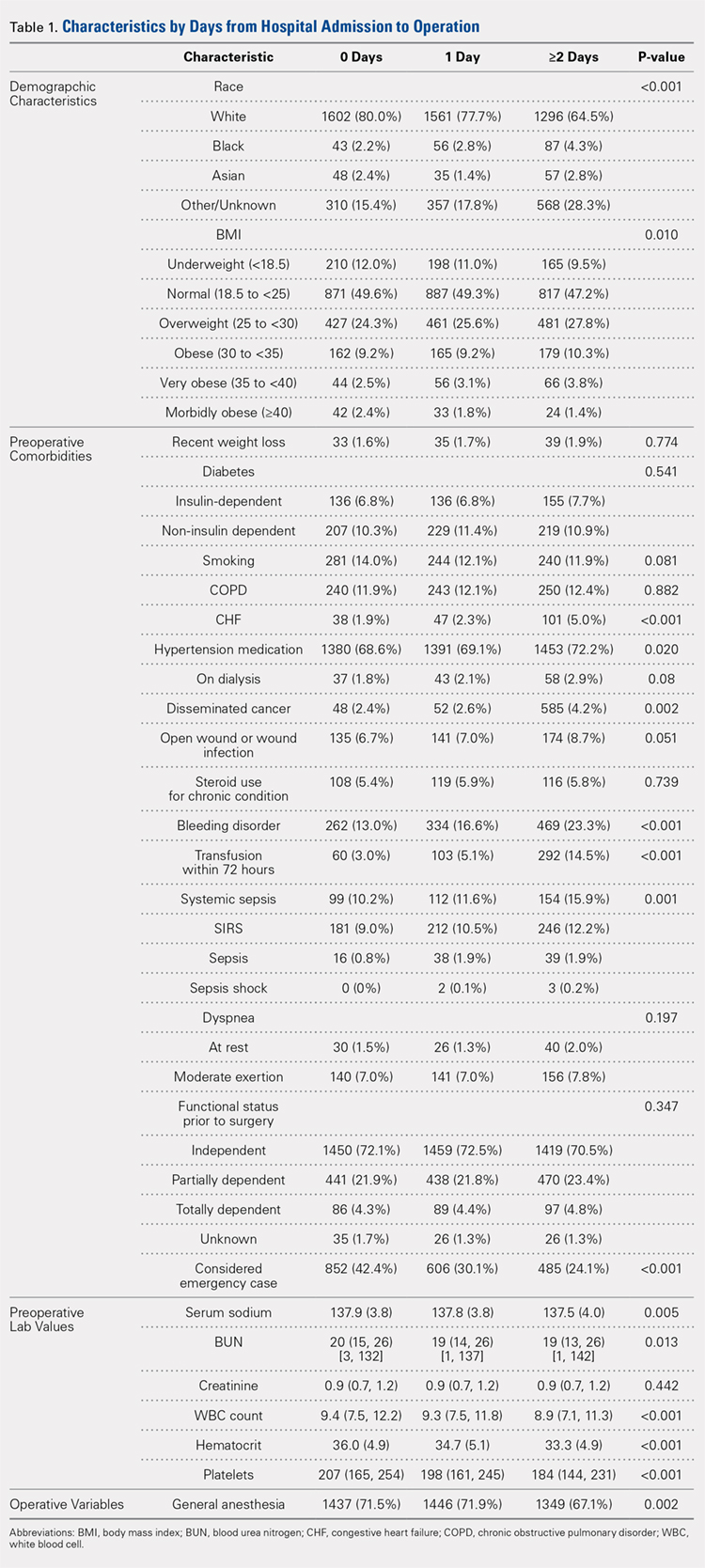

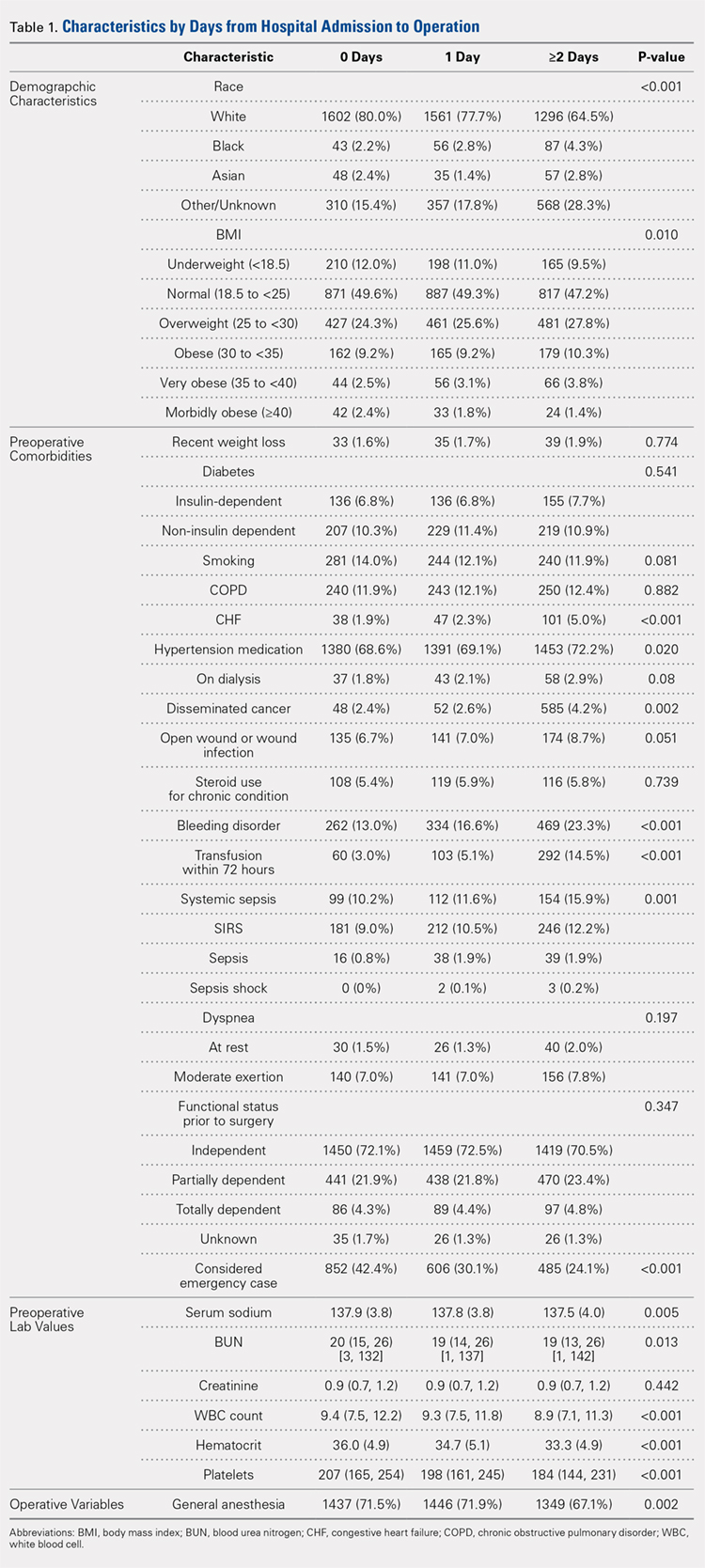

A study population of 6036 hip fractures was identified and divided into 3 groups of 2012 subjects each based upon time-to-surgery. The groups were successfully matched for surgery type, age (≥75 years old), gender, and ASA class. In each group, 594 of the 2012 (29.5%) patients were male, 1525 (75.8%) were ≥75 years of age, 9 (.5%) were ASA Class I, 269 (13.4%) were ASA Class II, 1424 (70.8%) were ASA class III, and 309 (15.4%) were ASA class IV.

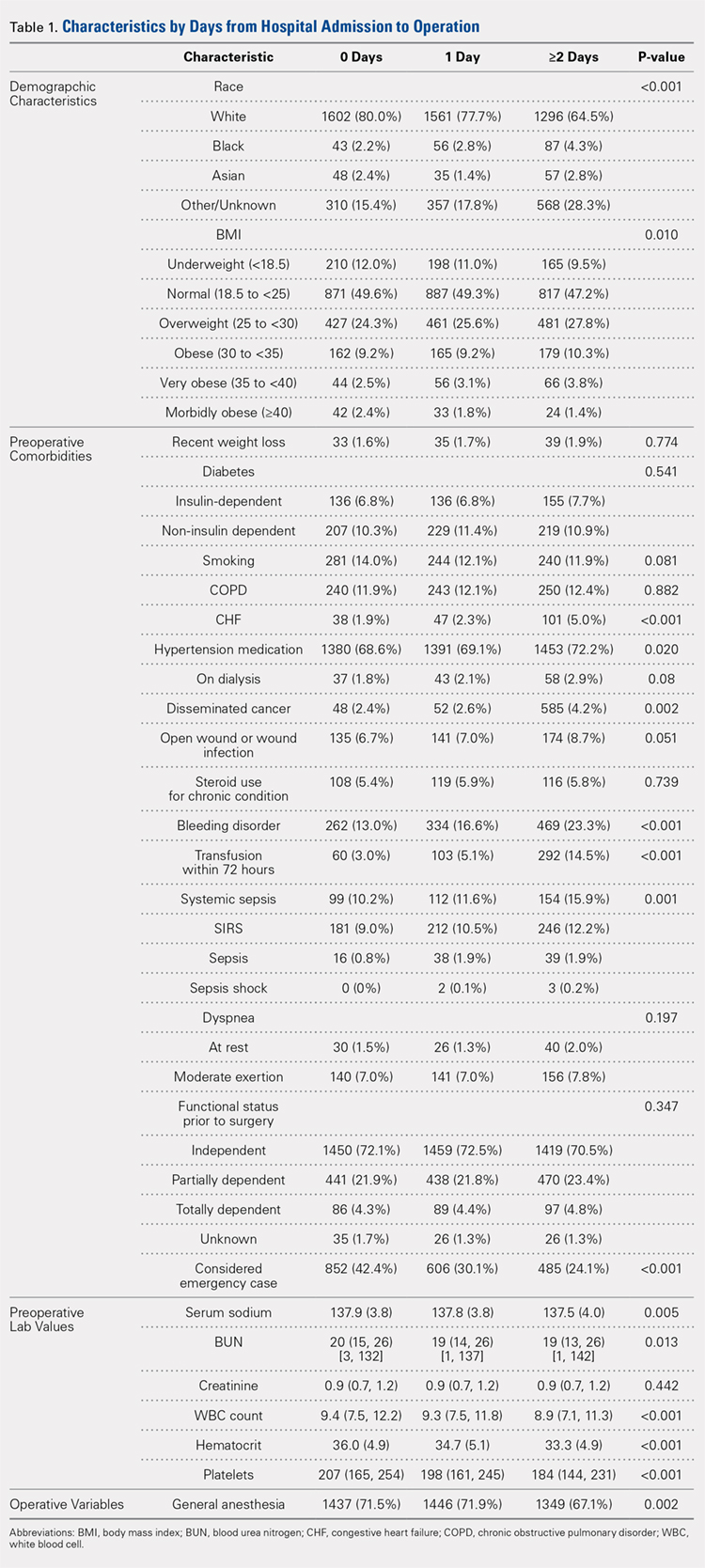

Significant differences in preoperative comorbidity burden and preoperative lab values were identified between the 3 cohorts. Increased time-to-surgery was associated with differences in race (P < .001), elevated BMI (P = .010), higher rates of congestive heart failure (P < .001), hypertension medication (P = .020), bleeding disorders (P < .001), blood transfusion within 72 hours of surgery (P < .001), and systemic sepsis (P = .001). Delay to surgery was also associated with lower preoperative sodium (P = .005), blood urea nitrogen (P = .013), serum WBC (P < .001), hematocrit (P < .001), and platelets (P < .001) (Table 1).

The unadjusted analyses revealed no association between time-to-surgery and return to OR (P = .554) nor readmission (P = .285). However, increasing time-to-surgery was associated with an increase in overall complications (P = .034), total length of hospital stay (P < .001), and 30-day mortality (P = .039) (Table 2).

Table 2. Estimated Event Rates from Matched Cohorts (Unadjusted)

| Time From Presentation to Definitive Fixation | |||

Outcomes | <24 hours | 24-48 hours | >48 hours | P-value |

Overall complication rate | 15.30% | 15.30% | 17.90% | 0.034 |

Total length of stay | 5.4 | 6.7 | 10.9 | <0.001 |

(mean days, 95% confidence interval) | (5.2, 5.7) | (6.5, 7.0) | (10.3, 11.5) | |

Time from OR to discharge | -ref- | 0.96 | 0.74 | <0.001 |

(Hazard ratio) | (0.90,1.02) | (0.69, 0.79) | ||

Return to OR | 2.40% | 2.40% | 2.00% | 0.554 |

Readmission | 9.60% | 8.40% | 8.30% | 0.285 |

30-day mortality rate | 5.80% | 5.30% | 7.20% | 0.039 |

Abbreviation: OR, operating room.