User login

How Is the Colorectal Cancer Control Program Doing?

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

The CDC developed the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) to provide direct colorectal cancer (CRC) screening services to low-income, uninsured, or underinsured populations known to have low CRC screening rates. However, early evaluators found the program was insufficient to detect impact at the state level. In response to those findings, the CDC redesigned CRCCP and funded a new 5-year grant period beginning in 2015. How did the program fare this time? CDC researchers say it “shows promise.”

The CRCCP funds 23 states, 6 universities, and 1 tribal organization to partner with health care systems, implementing evidence-based interventions (EBIs). In this study, the researchers analyzed data reported by 387 of 413 clinics of varying sizes, representing 3,438 providers, and serving a screening-eligible population of 722,925 patients.

The researchers say their evaluation suggests that the CRCCP is working as intended: Program reach was measurable and “substantial,” clinics enhanced EBIs in place or implemented new ones, and the overall average screening rate rose.

At baseline, the screening rate was low (43%), and lowest in rural clinics—although evidence indicates that death rates for CRC are highest among people living in rural areas. In the first year, the overall screening rate increased by 4.4 percentage points. Still, that 47.3% is “much lower” than the commonly cited 67.3% from the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the researchers note. They add, though, that the results confirm that grantees are working with clinics serving the intended populations and indicate the significant gap in CRC screening rates between those reached by the CRCCP and the US population overall.

Many clinics had ≥ 1 EBI or supporting activity (SA) already in place. Grantees used CRCCP resources to implement new or to enhance EBIs in 95% of the clinics, most often patient reminder activities and provider assessment and feedback. Most of the clinics used CRCCP resources for SAs, such as small media and provider education. Only 12% of clinics used resources for supporting community health workers. However, nearly half the clinics conducted planning activities for future implementation of community health workers and patient navigators.

Nearly 80% of the clinics reported having a CRC screening champion, 73% had a CRC screening policy, and 50% had either 3 or 4 EBIs in place at the end of the first year—all factors that the researchers suggest may support greater screening rate increases.

HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma responds to checkpoint inhibitors

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy is effective for patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS), a recent study has found.

Partial or complete remission was achieved by a majority of patients; others currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, reported Natalie Galanina, MD, of Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues. Earlier this year, investigators reported similar responses to checkpoint inhibitors in two patients with KS that wasn’t associated with HIV.

“An association has been demonstrated between chronic viral infection, malignancy, and up-regulation of programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) on CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes,” the authors wrote in Cancer Immunology Research. In particular, “HIV-specific CD8+ T cells have increased PD-1 expression, which … promotes a cellular milieu conducive to oncogenesis.” These factors, together with the results from the previous study, have suggested that checkpoint inhibitors may be effective for patients with HIV-associated KS.

The retrospective study involved 320 patients treated with immunotherapy at Moores Cancer Center from August 2013 through December 2017. From this group, nine cases of HIV-associated KS were found. Median CD4 count was 256 cells/mcL and median viral load was 20 copies/mL. Eight patients were treated with nivolumab and one was treated with pembrolizumab. Median age was 44 years. All patients were male and receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Six patients (67%) achieved remission, with five attaining partial remission and one attaining complete remission (gastrointestinal disease). Of the remaining three patients, two currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, and one has stable disease lasting longer than 3 months.

Muscle aches, pruritus, and low-grade fever were the most common adverse events. No grade 3 or higher drug-related adverse events occurred.

“Most of our patients received one to four prior lines of therapy but still responded to checkpoint blockade,” the authors wrote. “Our observations suggest that patients with HIV-associated KS have high [response rates] to PD-1 checkpoint blockade, without significant toxicity, even in the presence of low [tumor mutational burden] and/or lack of PD-L1 expression.”

Authors reported compensation from Incyte, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Galanina et al. Cancer Immunol Res. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0121.

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy is effective for patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS), a recent study has found.

Partial or complete remission was achieved by a majority of patients; others currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, reported Natalie Galanina, MD, of Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues. Earlier this year, investigators reported similar responses to checkpoint inhibitors in two patients with KS that wasn’t associated with HIV.

“An association has been demonstrated between chronic viral infection, malignancy, and up-regulation of programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) on CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes,” the authors wrote in Cancer Immunology Research. In particular, “HIV-specific CD8+ T cells have increased PD-1 expression, which … promotes a cellular milieu conducive to oncogenesis.” These factors, together with the results from the previous study, have suggested that checkpoint inhibitors may be effective for patients with HIV-associated KS.

The retrospective study involved 320 patients treated with immunotherapy at Moores Cancer Center from August 2013 through December 2017. From this group, nine cases of HIV-associated KS were found. Median CD4 count was 256 cells/mcL and median viral load was 20 copies/mL. Eight patients were treated with nivolumab and one was treated with pembrolizumab. Median age was 44 years. All patients were male and receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Six patients (67%) achieved remission, with five attaining partial remission and one attaining complete remission (gastrointestinal disease). Of the remaining three patients, two currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, and one has stable disease lasting longer than 3 months.

Muscle aches, pruritus, and low-grade fever were the most common adverse events. No grade 3 or higher drug-related adverse events occurred.

“Most of our patients received one to four prior lines of therapy but still responded to checkpoint blockade,” the authors wrote. “Our observations suggest that patients with HIV-associated KS have high [response rates] to PD-1 checkpoint blockade, without significant toxicity, even in the presence of low [tumor mutational burden] and/or lack of PD-L1 expression.”

Authors reported compensation from Incyte, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Galanina et al. Cancer Immunol Res. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0121.

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy is effective for patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS), a recent study has found.

Partial or complete remission was achieved by a majority of patients; others currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, reported Natalie Galanina, MD, of Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, and her colleagues. Earlier this year, investigators reported similar responses to checkpoint inhibitors in two patients with KS that wasn’t associated with HIV.

“An association has been demonstrated between chronic viral infection, malignancy, and up-regulation of programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) on CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes,” the authors wrote in Cancer Immunology Research. In particular, “HIV-specific CD8+ T cells have increased PD-1 expression, which … promotes a cellular milieu conducive to oncogenesis.” These factors, together with the results from the previous study, have suggested that checkpoint inhibitors may be effective for patients with HIV-associated KS.

The retrospective study involved 320 patients treated with immunotherapy at Moores Cancer Center from August 2013 through December 2017. From this group, nine cases of HIV-associated KS were found. Median CD4 count was 256 cells/mcL and median viral load was 20 copies/mL. Eight patients were treated with nivolumab and one was treated with pembrolizumab. Median age was 44 years. All patients were male and receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Six patients (67%) achieved remission, with five attaining partial remission and one attaining complete remission (gastrointestinal disease). Of the remaining three patients, two currently have stable disease lasting longer than 6 months, and one has stable disease lasting longer than 3 months.

Muscle aches, pruritus, and low-grade fever were the most common adverse events. No grade 3 or higher drug-related adverse events occurred.

“Most of our patients received one to four prior lines of therapy but still responded to checkpoint blockade,” the authors wrote. “Our observations suggest that patients with HIV-associated KS have high [response rates] to PD-1 checkpoint blockade, without significant toxicity, even in the presence of low [tumor mutational burden] and/or lack of PD-L1 expression.”

Authors reported compensation from Incyte, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Galanina et al. Cancer Immunol Res. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0121.

FROM CANCER IMMUNOLOGY RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Checkpoint inhibitor therapy is effective for patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma.

Major finding: Two-thirds of patients (67%) with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma achieved partial or complete remission when treated with immune checkpoint blockade.

Study details: A retrospective study involving nine patients with Kaposi sarcoma treated with either nivolumab or pembrolizumab at the Rebecca and John Moores Cancer Center at the University of California, San Diego, (UCSD) from August 2013 through December 2017.

Disclosures: Authors reported compensation from Incyte, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Source: Galanina et al. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018 Sept 7. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0121.

First CAR T-cell therapy approved in Canada

Health Canada has authorized use of tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah™), making it the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy to receive regulatory approval in Canada.

Tisagenlecleucel (formerly CTL019) is approved to treat patients ages 3 to 25 with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who have relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) or are otherwise ineligible for SCT, have experienced second or later relapse, or have refractory disease.

Tisagenlecleucel is also approved in Canada to treat adults who have received two or more lines of systemic therapy and have relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, or DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, said it is working with qualified treatment centers in Canada to prepare for the delivery of tisagenlecleucel. Certification and training are underway at these centers, and Novartis is enhancing manufacturing capacity to meet patient needs.

Tisagenlecleucel has been studied in a pair of phase 2 trials—ELIANA and JULIET.

JULIET trial

JULIET enrolled 165 adults with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, and 111 of them received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Ninety-two percent of patients received bridging therapy, and 93% received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to tisagenlecleucel.

The overall response rate was 52%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 40%. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 13.9 months. At last follow-up, none of the responders had gone on to SCT.

The 12-month overall survival (OS) rate was 49%, and the median OS was 11.7 months. The median OS was not reached for patients in CR.

Within 8 weeks of tisagenlecleucel infusion, 22% of patients had developed grade 3/4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Other adverse events (AEs) of interest included grade 3/4 neurologic events (12%), grade 3/4 cytopenias lasting more than 28 days (32%), grade 3/4 infections (20%), and grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia (15%).

These results were presented at the 23rd Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association in June (abstract S799).

ELIANA trial

ELIANA included 75 children and young adults with relapsed/refractory ALL. The patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel, and 72 received lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months. The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) within 3 months.

The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi. All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

Eight patients proceeded to SCT while in remission. At last follow-up, four were still in remission, and four had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the OS rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

Ninety-five percent of patients had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. The incidence of treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs was 73%.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in February.

Health Canada has authorized use of tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah™), making it the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy to receive regulatory approval in Canada.

Tisagenlecleucel (formerly CTL019) is approved to treat patients ages 3 to 25 with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who have relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) or are otherwise ineligible for SCT, have experienced second or later relapse, or have refractory disease.

Tisagenlecleucel is also approved in Canada to treat adults who have received two or more lines of systemic therapy and have relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, or DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, said it is working with qualified treatment centers in Canada to prepare for the delivery of tisagenlecleucel. Certification and training are underway at these centers, and Novartis is enhancing manufacturing capacity to meet patient needs.

Tisagenlecleucel has been studied in a pair of phase 2 trials—ELIANA and JULIET.

JULIET trial

JULIET enrolled 165 adults with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, and 111 of them received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Ninety-two percent of patients received bridging therapy, and 93% received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to tisagenlecleucel.

The overall response rate was 52%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 40%. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 13.9 months. At last follow-up, none of the responders had gone on to SCT.

The 12-month overall survival (OS) rate was 49%, and the median OS was 11.7 months. The median OS was not reached for patients in CR.

Within 8 weeks of tisagenlecleucel infusion, 22% of patients had developed grade 3/4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Other adverse events (AEs) of interest included grade 3/4 neurologic events (12%), grade 3/4 cytopenias lasting more than 28 days (32%), grade 3/4 infections (20%), and grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia (15%).

These results were presented at the 23rd Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association in June (abstract S799).

ELIANA trial

ELIANA included 75 children and young adults with relapsed/refractory ALL. The patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel, and 72 received lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months. The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) within 3 months.

The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi. All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

Eight patients proceeded to SCT while in remission. At last follow-up, four were still in remission, and four had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the OS rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

Ninety-five percent of patients had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. The incidence of treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs was 73%.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in February.

Health Canada has authorized use of tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah™), making it the first chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy to receive regulatory approval in Canada.

Tisagenlecleucel (formerly CTL019) is approved to treat patients ages 3 to 25 with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who have relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) or are otherwise ineligible for SCT, have experienced second or later relapse, or have refractory disease.

Tisagenlecleucel is also approved in Canada to treat adults who have received two or more lines of systemic therapy and have relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) not otherwise specified, high grade B-cell lymphoma, or DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma.

Novartis, the company marketing tisagenlecleucel, said it is working with qualified treatment centers in Canada to prepare for the delivery of tisagenlecleucel. Certification and training are underway at these centers, and Novartis is enhancing manufacturing capacity to meet patient needs.

Tisagenlecleucel has been studied in a pair of phase 2 trials—ELIANA and JULIET.

JULIET trial

JULIET enrolled 165 adults with relapsed/refractory DLBCL, and 111 of them received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel. Ninety-two percent of patients received bridging therapy, and 93% received lymphodepleting chemotherapy prior to tisagenlecleucel.

The overall response rate was 52%, and the complete response (CR) rate was 40%. The median duration of response was not reached with a median follow-up of 13.9 months. At last follow-up, none of the responders had gone on to SCT.

The 12-month overall survival (OS) rate was 49%, and the median OS was 11.7 months. The median OS was not reached for patients in CR.

Within 8 weeks of tisagenlecleucel infusion, 22% of patients had developed grade 3/4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Other adverse events (AEs) of interest included grade 3/4 neurologic events (12%), grade 3/4 cytopenias lasting more than 28 days (32%), grade 3/4 infections (20%), and grade 3/4 febrile neutropenia (15%).

These results were presented at the 23rd Annual Congress of the European Hematology Association in June (abstract S799).

ELIANA trial

ELIANA included 75 children and young adults with relapsed/refractory ALL. The patients’ median age was 11 (range, 3 to 23).

All patients received a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel, and 72 received lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

The median duration of follow-up was 13.1 months. The study’s primary endpoint was overall remission rate, which was defined as the rate of a best overall response of either CR or CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) within 3 months.

The overall remission rate was 81% (61/75), with 60% of patients (n=45) achieving a CR and 21% (n=16) achieving a CRi. All patients whose best response was CR/CRi were negative for minimal residual disease. The median duration of response was not met.

Eight patients proceeded to SCT while in remission. At last follow-up, four were still in remission, and four had unknown disease status.

At 6 months, the event-free survival rate was 73%, and the OS rate was 90%. At 12 months, the rates were 50% and 76%, respectively.

Ninety-five percent of patients had AEs thought to be related to tisagenlecleucel. The incidence of treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs was 73%.

AEs of special interest included CRS (77%), neurologic events (40%), infections (43%), febrile neutropenia (35%), cytopenias not resolved by day 28 (37%), and tumor lysis syndrome (4%).

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in February.

Regimens produce similar results in FL

Rituximab plus lenalidomide had efficacy similar to that of rituximab plus chemotherapy in the treatment of follicular lymphoma (FL) in a phase 3 trial.

Patients with previously untreated FL had similar complete response (CR) rates and progression-free survival (PFS) rates whether they received rituximab-based chemotherapy or rituximab plus lenalidomide.

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial, RELEVANCE, included 1,030 patients with previously untreated FL. They were randomized to receive rituximab plus chemotherapy (n=517) or rituximab plus lenalidomide (n=513) for 18 cycles.

Patients in the chemotherapy arm received one of three regimens—R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), rituximab and bendamustine, or R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone).

Patients in both treatment arms went on to receive rituximab maintenance every 8 weeks for 12 cycles. The total duration of treatment was 120 weeks. The median age of the combined groups was 59 years.

The coprimary endpoints were CR (confirmed or unconfirmed) and PFS. After a median follow-up of 37.9 months, the rates of coprimary endpoints were similar between the treatment arms.

CR was observed in 48% of the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 53% of the rituximab-chemotherapy arm (P=0.13).

The interim 3-year PFS rate was 77% in the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 78% in the rituximab-chemotherapy arm. The hazard ratio for progression or death from any cause was 1.10 (P=0.48).

The efficacy of rituximab plus chemotherapy was greater in low-risk patients (based on Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index scores) and in patients whose disease was Ann Arbor stage I or II, whereas the efficacy of rituximab-lenalidomide was independent of prognostic factors.

Safety was the biggest area of difference, with some adverse events (AEs) being more common in one arm than the other.

AEs that were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide include cutaneous reactions (43% vs 24%), diarrhea (37% vs 19%), rash (29% vs 8%), abdominal pain (15% vs 9%), peripheral edema (14% vs 9%), muscle spasms (13% vs 4%), myalgia (14% vs 6%), and tumor flare reaction (6% vs <1%).

AEs that were more common with rituximab-chemotherapy were anemia (89% vs 66%), fatigue (29% vs 23%), nausea (42% vs 20%), vomiting (19% vs 7%), febrile neutropenia (7% vs 2%), leukopenia (10% vs 4%), and peripheral neuropathy (16% vs 7%).

Grade 3/4 cutaneous reactions were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide (7% vs 1%), and grade 3/4 neutropenia was more common with rituximab-chemotherapy (50% vs 32%).

The RELEVANCE trial was sponsored by Celgene and the Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation. The study authors reported various disclosures, including financial ties to Celgene.

Rituximab plus lenalidomide had efficacy similar to that of rituximab plus chemotherapy in the treatment of follicular lymphoma (FL) in a phase 3 trial.

Patients with previously untreated FL had similar complete response (CR) rates and progression-free survival (PFS) rates whether they received rituximab-based chemotherapy or rituximab plus lenalidomide.

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial, RELEVANCE, included 1,030 patients with previously untreated FL. They were randomized to receive rituximab plus chemotherapy (n=517) or rituximab plus lenalidomide (n=513) for 18 cycles.

Patients in the chemotherapy arm received one of three regimens—R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), rituximab and bendamustine, or R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone).

Patients in both treatment arms went on to receive rituximab maintenance every 8 weeks for 12 cycles. The total duration of treatment was 120 weeks. The median age of the combined groups was 59 years.

The coprimary endpoints were CR (confirmed or unconfirmed) and PFS. After a median follow-up of 37.9 months, the rates of coprimary endpoints were similar between the treatment arms.

CR was observed in 48% of the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 53% of the rituximab-chemotherapy arm (P=0.13).

The interim 3-year PFS rate was 77% in the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 78% in the rituximab-chemotherapy arm. The hazard ratio for progression or death from any cause was 1.10 (P=0.48).

The efficacy of rituximab plus chemotherapy was greater in low-risk patients (based on Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index scores) and in patients whose disease was Ann Arbor stage I or II, whereas the efficacy of rituximab-lenalidomide was independent of prognostic factors.

Safety was the biggest area of difference, with some adverse events (AEs) being more common in one arm than the other.

AEs that were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide include cutaneous reactions (43% vs 24%), diarrhea (37% vs 19%), rash (29% vs 8%), abdominal pain (15% vs 9%), peripheral edema (14% vs 9%), muscle spasms (13% vs 4%), myalgia (14% vs 6%), and tumor flare reaction (6% vs <1%).

AEs that were more common with rituximab-chemotherapy were anemia (89% vs 66%), fatigue (29% vs 23%), nausea (42% vs 20%), vomiting (19% vs 7%), febrile neutropenia (7% vs 2%), leukopenia (10% vs 4%), and peripheral neuropathy (16% vs 7%).

Grade 3/4 cutaneous reactions were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide (7% vs 1%), and grade 3/4 neutropenia was more common with rituximab-chemotherapy (50% vs 32%).

The RELEVANCE trial was sponsored by Celgene and the Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation. The study authors reported various disclosures, including financial ties to Celgene.

Rituximab plus lenalidomide had efficacy similar to that of rituximab plus chemotherapy in the treatment of follicular lymphoma (FL) in a phase 3 trial.

Patients with previously untreated FL had similar complete response (CR) rates and progression-free survival (PFS) rates whether they received rituximab-based chemotherapy or rituximab plus lenalidomide.

These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The trial, RELEVANCE, included 1,030 patients with previously untreated FL. They were randomized to receive rituximab plus chemotherapy (n=517) or rituximab plus lenalidomide (n=513) for 18 cycles.

Patients in the chemotherapy arm received one of three regimens—R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), rituximab and bendamustine, or R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone).

Patients in both treatment arms went on to receive rituximab maintenance every 8 weeks for 12 cycles. The total duration of treatment was 120 weeks. The median age of the combined groups was 59 years.

The coprimary endpoints were CR (confirmed or unconfirmed) and PFS. After a median follow-up of 37.9 months, the rates of coprimary endpoints were similar between the treatment arms.

CR was observed in 48% of the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 53% of the rituximab-chemotherapy arm (P=0.13).

The interim 3-year PFS rate was 77% in the rituximab-lenalidomide arm and 78% in the rituximab-chemotherapy arm. The hazard ratio for progression or death from any cause was 1.10 (P=0.48).

The efficacy of rituximab plus chemotherapy was greater in low-risk patients (based on Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index scores) and in patients whose disease was Ann Arbor stage I or II, whereas the efficacy of rituximab-lenalidomide was independent of prognostic factors.

Safety was the biggest area of difference, with some adverse events (AEs) being more common in one arm than the other.

AEs that were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide include cutaneous reactions (43% vs 24%), diarrhea (37% vs 19%), rash (29% vs 8%), abdominal pain (15% vs 9%), peripheral edema (14% vs 9%), muscle spasms (13% vs 4%), myalgia (14% vs 6%), and tumor flare reaction (6% vs <1%).

AEs that were more common with rituximab-chemotherapy were anemia (89% vs 66%), fatigue (29% vs 23%), nausea (42% vs 20%), vomiting (19% vs 7%), febrile neutropenia (7% vs 2%), leukopenia (10% vs 4%), and peripheral neuropathy (16% vs 7%).

Grade 3/4 cutaneous reactions were more common with rituximab-lenalidomide (7% vs 1%), and grade 3/4 neutropenia was more common with rituximab-chemotherapy (50% vs 32%).

The RELEVANCE trial was sponsored by Celgene and the Lymphoma Academic Research Organisation. The study authors reported various disclosures, including financial ties to Celgene.

Ibrutinib maintains efficacy over time

Extended follow-up of the RESONATE-2 trial showed that first-line ibrutinib sustained efficacy in elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Patients who received ibrutinib had a long-term progression-free survival benefit over those who received chlorambucil.

The depth of response to ibrutinib improved over time, which meant there was a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response.

Additionally, rates of some serious adverse events associated with ibrutinib decreased over time.

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in Haematologica.

Previously reported results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in the risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized to receive ibrutinib (n=136) or chlorambucil (n=133).

At a median follow-up of 29 months, 79% (107/136) of patients remained on ibrutinib.

There was an 88% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients randomized to ibrutinib (P<0.0001).

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months to 15% at 24 months and 18% at 36 months (maximum follow-up).

The overall response rate (ORR) with ibrutinib was 92%, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups. The ORR was 100% in patients with del(11q) and 95% in those with unmutated IGHV.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42%, compared to 7% of patients who received chlorambucil.

Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 52% in chlorambucil recipients, with complete resolution in 56% and 22%, respectively.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time.

The rate of grade 3 or higher neutropenia decreased from 8.1% in the first 12 months of treatment to 0% in the third year. The rate of grade 3 or higher anemia decreased from 5.9% to 1%. And the rate of grade 3 or higher thrombocytopenia decreased from 2.2% to 0%.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up. However, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse event were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.

Extended follow-up of the RESONATE-2 trial showed that first-line ibrutinib sustained efficacy in elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Patients who received ibrutinib had a long-term progression-free survival benefit over those who received chlorambucil.

The depth of response to ibrutinib improved over time, which meant there was a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response.

Additionally, rates of some serious adverse events associated with ibrutinib decreased over time.

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in Haematologica.

Previously reported results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in the risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized to receive ibrutinib (n=136) or chlorambucil (n=133).

At a median follow-up of 29 months, 79% (107/136) of patients remained on ibrutinib.

There was an 88% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients randomized to ibrutinib (P<0.0001).

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months to 15% at 24 months and 18% at 36 months (maximum follow-up).

The overall response rate (ORR) with ibrutinib was 92%, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups. The ORR was 100% in patients with del(11q) and 95% in those with unmutated IGHV.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42%, compared to 7% of patients who received chlorambucil.

Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 52% in chlorambucil recipients, with complete resolution in 56% and 22%, respectively.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time.

The rate of grade 3 or higher neutropenia decreased from 8.1% in the first 12 months of treatment to 0% in the third year. The rate of grade 3 or higher anemia decreased from 5.9% to 1%. And the rate of grade 3 or higher thrombocytopenia decreased from 2.2% to 0%.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up. However, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse event were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.

Extended follow-up of the RESONATE-2 trial showed that first-line ibrutinib sustained efficacy in elderly patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Patients who received ibrutinib had a long-term progression-free survival benefit over those who received chlorambucil.

The depth of response to ibrutinib improved over time, which meant there was a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response.

Additionally, rates of some serious adverse events associated with ibrutinib decreased over time.

Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, and his colleagues reported these findings in Haematologica.

Previously reported results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in the risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized to receive ibrutinib (n=136) or chlorambucil (n=133).

At a median follow-up of 29 months, 79% (107/136) of patients remained on ibrutinib.

There was an 88% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients randomized to ibrutinib (P<0.0001).

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months to 15% at 24 months and 18% at 36 months (maximum follow-up).

The overall response rate (ORR) with ibrutinib was 92%, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups. The ORR was 100% in patients with del(11q) and 95% in those with unmutated IGHV.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42%, compared to 7% of patients who received chlorambucil.

Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 52% in chlorambucil recipients, with complete resolution in 56% and 22%, respectively.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time.

The rate of grade 3 or higher neutropenia decreased from 8.1% in the first 12 months of treatment to 0% in the third year. The rate of grade 3 or higher anemia decreased from 5.9% to 1%. And the rate of grade 3 or higher thrombocytopenia decreased from 2.2% to 0%.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up. However, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse event were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

This study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.

RESONATE-2 update: First-line ibrutinib has sustained efficacy in older CLL patients

In older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), first-line treatment with ibrutinib resulted in a long-term progression-free survival benefit versus chemotherapy, according to extended follow-up results of a phase 3 trial.

The quality of response to ibrutinib continued to improve over time in the study, including a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response, the updated results of the RESONATE-2 trial show.

Rates of serious adverse events decreased over time in the study, while common reasons for initiating treatment, such as marrow failure and disease symptoms, all improved to a greater extent than with chlorambucil, reported Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and colleagues.

“These data support the use of ibrutinib in the first-line treatment of CLL as a chemotherapy-free option that can be taken continuously, achieving long-term disease control for the majority of patients, including those with high-risk features,” Dr. Barr and coauthors said in the journal Haematologica.

Previously reported primary results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil with a median follow-up of 18 months, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized 1:1 to ibrutinib or chlorambucil.

Out of 136 ibrutinib-treated patients, 107 (79%) remained on therapy at this extended analysis, which had a median follow-up of 29 months.

The extended analysis also showed an 88% reduction in risk of progression or death for those patients randomized to ibrutinib (P less than .0001), with significant improvements in subgroups evaluated, which include groups typically considered high risk, according to Dr. Barr and colleagues.

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months, to 15% at 24 months, and to 18% with a maximum of 36 months’ follow-up, they said.

The overall response rate for ibrutinib was 92% in this extended analysis, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups, including those with del(11q) at 100% and unmutated IGHV at 95%, according to the report.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42% versus 7% with chlorambucil. Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients versus 52% for chlorambucil, with complete resolution in 56% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 22% of chlorambucil-treated patients.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time. Rates of grade 3 or greater neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia were 8.1%, 5.9%, and 2.2%, respectively, in the first 12 months of treatment; those decreased to 0%, 1%, and 0% in the third year.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up; however, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse effect were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.

SOURCE: Barr PM, et al. Haematologica. 2018;103(9):1502-10.

In older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), first-line treatment with ibrutinib resulted in a long-term progression-free survival benefit versus chemotherapy, according to extended follow-up results of a phase 3 trial.

The quality of response to ibrutinib continued to improve over time in the study, including a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response, the updated results of the RESONATE-2 trial show.

Rates of serious adverse events decreased over time in the study, while common reasons for initiating treatment, such as marrow failure and disease symptoms, all improved to a greater extent than with chlorambucil, reported Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and colleagues.

“These data support the use of ibrutinib in the first-line treatment of CLL as a chemotherapy-free option that can be taken continuously, achieving long-term disease control for the majority of patients, including those with high-risk features,” Dr. Barr and coauthors said in the journal Haematologica.

Previously reported primary results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil with a median follow-up of 18 months, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized 1:1 to ibrutinib or chlorambucil.

Out of 136 ibrutinib-treated patients, 107 (79%) remained on therapy at this extended analysis, which had a median follow-up of 29 months.

The extended analysis also showed an 88% reduction in risk of progression or death for those patients randomized to ibrutinib (P less than .0001), with significant improvements in subgroups evaluated, which include groups typically considered high risk, according to Dr. Barr and colleagues.

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months, to 15% at 24 months, and to 18% with a maximum of 36 months’ follow-up, they said.

The overall response rate for ibrutinib was 92% in this extended analysis, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups, including those with del(11q) at 100% and unmutated IGHV at 95%, according to the report.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42% versus 7% with chlorambucil. Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients versus 52% for chlorambucil, with complete resolution in 56% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 22% of chlorambucil-treated patients.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time. Rates of grade 3 or greater neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia were 8.1%, 5.9%, and 2.2%, respectively, in the first 12 months of treatment; those decreased to 0%, 1%, and 0% in the third year.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up; however, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse effect were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.

SOURCE: Barr PM, et al. Haematologica. 2018;103(9):1502-10.

In older patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), first-line treatment with ibrutinib resulted in a long-term progression-free survival benefit versus chemotherapy, according to extended follow-up results of a phase 3 trial.

The quality of response to ibrutinib continued to improve over time in the study, including a substantial increase in the proportion of patients achieving complete response, the updated results of the RESONATE-2 trial show.

Rates of serious adverse events decreased over time in the study, while common reasons for initiating treatment, such as marrow failure and disease symptoms, all improved to a greater extent than with chlorambucil, reported Paul M. Barr, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and colleagues.

“These data support the use of ibrutinib in the first-line treatment of CLL as a chemotherapy-free option that can be taken continuously, achieving long-term disease control for the majority of patients, including those with high-risk features,” Dr. Barr and coauthors said in the journal Haematologica.

Previously reported primary results of the RESONATE-2 trial, which showed an 84% reduction in risk of death for ibrutinib versus chlorambucil with a median follow-up of 18 months, led to the approval of ibrutinib for first-line CLL treatment, the authors said.

The study included 269 patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma who had active disease and were at least 65 years of age. They were randomized 1:1 to ibrutinib or chlorambucil.

Out of 136 ibrutinib-treated patients, 107 (79%) remained on therapy at this extended analysis, which had a median follow-up of 29 months.

The extended analysis also showed an 88% reduction in risk of progression or death for those patients randomized to ibrutinib (P less than .0001), with significant improvements in subgroups evaluated, which include groups typically considered high risk, according to Dr. Barr and colleagues.

The rate of complete response improved over time in ibrutinib-treated patients, from 7% at 12 months, to 15% at 24 months, and to 18% with a maximum of 36 months’ follow-up, they said.

The overall response rate for ibrutinib was 92% in this extended analysis, with comparable findings in high-risk subgroups, including those with del(11q) at 100% and unmutated IGHV at 95%, according to the report.

Lymphadenopathy improved in most ibrutinib-treated patients, with complete resolution in 42% versus 7% with chlorambucil. Splenomegaly improved by at least 50% in 95% of ibrutinib-treated patients versus 52% for chlorambucil, with complete resolution in 56% of ibrutinib-treated patients and 22% of chlorambucil-treated patients.

Adverse events of grade 3 or greater were generally seen more often in the first year of ibrutinib therapy and decreased over time. Rates of grade 3 or greater neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia were 8.1%, 5.9%, and 2.2%, respectively, in the first 12 months of treatment; those decreased to 0%, 1%, and 0% in the third year.

The rate of atrial fibrillation increased from 6% in the primary analysis to 10% in extended follow-up; however, investigators said ibrutinib dose reductions and discontinuations because of this adverse effect were uncommon and less frequent with extended treatment.

“Atrial fibrillation therefore appears manageable and does not frequently necessitate ibrutinib discontinuation,” they concluded.

The study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data. Several study authors reported funding from various companies, including Pharmacyclics.

SOURCE: Barr PM, et al. Haematologica. 2018;103(9):1502-10.

FROM HAEMATOLOGICA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There was an 88% reduction in risk of progression-free survival events for those patients randomized to ibrutinib (P less than .0001).

Study details: Extended phase 3 results from the RESONATE-2 trial, including 269 older patients with untreated CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Pharmacyclics, an AbbVie company, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the MD Anderson Moon Shot Program in CLL. Pharmacyclics designed the study and performed analysis of the data.

Source: Barr PM et al. Haematologica. 2018;103(9):1502-10.

FILM: Rave review for indocyanine green in lymphatic mapping

Green is just as good – make that better – than blue at identifying sentinel lymph nodes in women with cervical and uterine cancers, results of the multicenter FILM (Fluorescence Imaging for Lymphatic Mapping) study indicate.

Among 176 patients randomly assigned to first have lymphatic mapping with indocyanine green fluorescent dye visualized with near infrared imaging followed by isosulfan blue dye visualized with white light, or the two modalities in the reverse order, indocyanine green identified 50% more lymph nodes in both modified intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, reported Michael Frumovitz, MD, from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and colleagues.

“Indocyanine green dye with near-infrared imaging identified significantly more sentinel nodes and more bilateral sentinel nodes than did isosulfan blue dye. It also identified all sentinel nodes with metastatic disease, whereas isosulfan blue dye missed a large proportion of them,” they wrote in the Lancet Oncology.

The FILM study was designed to determine whether fluorescent indocyanine green dye would be noninferior to isosulfan blue dye for accurately identifying sentinel lymph nodes in patients with cancer.

Although several single-center retrospective studies have reported on the use of interstitial injection of indocyanine green for lymphatic mapping in various solid tumors, including uterine and cervical cancers, there were no published studies comparing indocyanine green mapping to isosulfan blue mapping, the standard of care, the authors noted.

They enrolled 180 women aged 18 or older with clinical stage I endometrial or cervical cancers who were undergoing curative surgery and randomly assigned them as described above to have lymphatic mapping with each of the imaging modalities assigned in random order.

The patients but not the operators were masked as to the order of randomization.

Of the 180 patients enrolled, 176 received the intervention, and 13 of these patients were excluded because of major protocol violations, leaving 163 for a per-protocol analysis.

In the per-protocol analysis, 517 sentinel nodes were identified in the 163 patients, and of these, 478 (92%) were confirmed to be lymph nodes on pathological examination. This sample included 219 of 238 nodes identified with both blue and green dyes, all seven nodes revealed by blue dye alone, and 252 of 265 nodes identified by only green dye. Seven sentinel lymph nodes that were not identified by either dye were removed because they were enlarged or appeared suspicious on visual inspection.

In total, green dye identified 97% of lymph nodes in the per-protocol population, and blue dye identified 47%, an absolute difference of 50% (P less than .0001).

In the modified intention-to-treat population, which included all 176 patients randomized and treated, 545 nodes were identified, and 513 (94%) were confirmed to be lymph nodes on pathology. In this sample, 229 (92%) of 248 nodes showed both blue and green, nine nodes were blue only, and 266 (95%) of 279 were green only. Nine sentinel lymph nodes that were not revealed by either blue or green were removed for appearing suspicious or enlarged visually.

In total, in the modified-ITT analysis, 495 of 513 (96%) nodes were identified with the green dye and 238 (46%) were identified with the blue dye, again for an absolute difference of 50% (P less than .0001).

Based on the results of the study, the green dye’s maker, Novadaq Technologies, is submitting an application to the Food and Drug Administration for on-label use of interstitial injection of indocyanine green combined with near-infrared imaging for lymphatic mapping.

The study was funded by Novadaq. Dr. Frumovitz reported grants from Novadaq/Stryker during the conduct of the study, as well as personal fees; grants from Navidea; personal fees from Johnson & Johnson; and personal fees from Genentech outside the submitted work. The other authors declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Frumovitz M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30448-0.

In endometrial cancer, the site of injection is still debated; intracervical injection is simple and effective, but hysteroscopic peritumoral injection of the tracer might lead to increased detection of para-aortic sentinel lymph nodes. A combination of pericervical and hysteroscopic peritumoral injection could be useful in selected cases with a higher incidence, such as poorly differentiated carcinomas, or metastasis to isolated para-aortic lymph nodes. The oncologic significance of low-volume metastasis to sentinel lymph nodes and the role of systematic lymphadenectomy in patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes still remain unclear.

In cervical cancer, preliminary data from the LACC trial (NCT00614211) of long-term outcomes of different surgical methods need to be integrated with sentinel lymph node mapping. These data show a detrimental oncologic effect of a minimally invasive approach. If the LACC data are confirmed, two options might be considered: minimally invasive sentinel lymph node mapping as triage to an open radical hysterectomy or the adoption of dedicated near-infrared technology hardware for open surgery.

Through its user-friendliness and effectiveness, indocyanine green is enabling surgeons to transition from systematic lymphadenectomy to sentinel lymph node biopsy. After all, innovation is not only about new technologies, it is also about changing how people think about alternative treatment approaches.

Maria Luisa Gasparri, MD, Michael D. Mueller, MD, and Andrea Papadia, MD, are with the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University Hospital of Bern and University of Bern, Switzerland. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an editorial accompanying the study (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30514-X.) The authors declared no competing financial interests.

In endometrial cancer, the site of injection is still debated; intracervical injection is simple and effective, but hysteroscopic peritumoral injection of the tracer might lead to increased detection of para-aortic sentinel lymph nodes. A combination of pericervical and hysteroscopic peritumoral injection could be useful in selected cases with a higher incidence, such as poorly differentiated carcinomas, or metastasis to isolated para-aortic lymph nodes. The oncologic significance of low-volume metastasis to sentinel lymph nodes and the role of systematic lymphadenectomy in patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes still remain unclear.

In cervical cancer, preliminary data from the LACC trial (NCT00614211) of long-term outcomes of different surgical methods need to be integrated with sentinel lymph node mapping. These data show a detrimental oncologic effect of a minimally invasive approach. If the LACC data are confirmed, two options might be considered: minimally invasive sentinel lymph node mapping as triage to an open radical hysterectomy or the adoption of dedicated near-infrared technology hardware for open surgery.

Through its user-friendliness and effectiveness, indocyanine green is enabling surgeons to transition from systematic lymphadenectomy to sentinel lymph node biopsy. After all, innovation is not only about new technologies, it is also about changing how people think about alternative treatment approaches.

Maria Luisa Gasparri, MD, Michael D. Mueller, MD, and Andrea Papadia, MD, are with the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University Hospital of Bern and University of Bern, Switzerland. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an editorial accompanying the study (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30514-X.) The authors declared no competing financial interests.

In endometrial cancer, the site of injection is still debated; intracervical injection is simple and effective, but hysteroscopic peritumoral injection of the tracer might lead to increased detection of para-aortic sentinel lymph nodes. A combination of pericervical and hysteroscopic peritumoral injection could be useful in selected cases with a higher incidence, such as poorly differentiated carcinomas, or metastasis to isolated para-aortic lymph nodes. The oncologic significance of low-volume metastasis to sentinel lymph nodes and the role of systematic lymphadenectomy in patients with positive sentinel lymph nodes still remain unclear.

In cervical cancer, preliminary data from the LACC trial (NCT00614211) of long-term outcomes of different surgical methods need to be integrated with sentinel lymph node mapping. These data show a detrimental oncologic effect of a minimally invasive approach. If the LACC data are confirmed, two options might be considered: minimally invasive sentinel lymph node mapping as triage to an open radical hysterectomy or the adoption of dedicated near-infrared technology hardware for open surgery.

Through its user-friendliness and effectiveness, indocyanine green is enabling surgeons to transition from systematic lymphadenectomy to sentinel lymph node biopsy. After all, innovation is not only about new technologies, it is also about changing how people think about alternative treatment approaches.

Maria Luisa Gasparri, MD, Michael D. Mueller, MD, and Andrea Papadia, MD, are with the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University Hospital of Bern and University of Bern, Switzerland. Their remarks are adapted and condensed from an editorial accompanying the study (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30514-X.) The authors declared no competing financial interests.

Green is just as good – make that better – than blue at identifying sentinel lymph nodes in women with cervical and uterine cancers, results of the multicenter FILM (Fluorescence Imaging for Lymphatic Mapping) study indicate.

Among 176 patients randomly assigned to first have lymphatic mapping with indocyanine green fluorescent dye visualized with near infrared imaging followed by isosulfan blue dye visualized with white light, or the two modalities in the reverse order, indocyanine green identified 50% more lymph nodes in both modified intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, reported Michael Frumovitz, MD, from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and colleagues.

“Indocyanine green dye with near-infrared imaging identified significantly more sentinel nodes and more bilateral sentinel nodes than did isosulfan blue dye. It also identified all sentinel nodes with metastatic disease, whereas isosulfan blue dye missed a large proportion of them,” they wrote in the Lancet Oncology.

The FILM study was designed to determine whether fluorescent indocyanine green dye would be noninferior to isosulfan blue dye for accurately identifying sentinel lymph nodes in patients with cancer.

Although several single-center retrospective studies have reported on the use of interstitial injection of indocyanine green for lymphatic mapping in various solid tumors, including uterine and cervical cancers, there were no published studies comparing indocyanine green mapping to isosulfan blue mapping, the standard of care, the authors noted.

They enrolled 180 women aged 18 or older with clinical stage I endometrial or cervical cancers who were undergoing curative surgery and randomly assigned them as described above to have lymphatic mapping with each of the imaging modalities assigned in random order.

The patients but not the operators were masked as to the order of randomization.

Of the 180 patients enrolled, 176 received the intervention, and 13 of these patients were excluded because of major protocol violations, leaving 163 for a per-protocol analysis.

In the per-protocol analysis, 517 sentinel nodes were identified in the 163 patients, and of these, 478 (92%) were confirmed to be lymph nodes on pathological examination. This sample included 219 of 238 nodes identified with both blue and green dyes, all seven nodes revealed by blue dye alone, and 252 of 265 nodes identified by only green dye. Seven sentinel lymph nodes that were not identified by either dye were removed because they were enlarged or appeared suspicious on visual inspection.

In total, green dye identified 97% of lymph nodes in the per-protocol population, and blue dye identified 47%, an absolute difference of 50% (P less than .0001).

In the modified intention-to-treat population, which included all 176 patients randomized and treated, 545 nodes were identified, and 513 (94%) were confirmed to be lymph nodes on pathology. In this sample, 229 (92%) of 248 nodes showed both blue and green, nine nodes were blue only, and 266 (95%) of 279 were green only. Nine sentinel lymph nodes that were not revealed by either blue or green were removed for appearing suspicious or enlarged visually.

In total, in the modified-ITT analysis, 495 of 513 (96%) nodes were identified with the green dye and 238 (46%) were identified with the blue dye, again for an absolute difference of 50% (P less than .0001).

Based on the results of the study, the green dye’s maker, Novadaq Technologies, is submitting an application to the Food and Drug Administration for on-label use of interstitial injection of indocyanine green combined with near-infrared imaging for lymphatic mapping.

The study was funded by Novadaq. Dr. Frumovitz reported grants from Novadaq/Stryker during the conduct of the study, as well as personal fees; grants from Navidea; personal fees from Johnson & Johnson; and personal fees from Genentech outside the submitted work. The other authors declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Frumovitz M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30448-0.

Green is just as good – make that better – than blue at identifying sentinel lymph nodes in women with cervical and uterine cancers, results of the multicenter FILM (Fluorescence Imaging for Lymphatic Mapping) study indicate.

Among 176 patients randomly assigned to first have lymphatic mapping with indocyanine green fluorescent dye visualized with near infrared imaging followed by isosulfan blue dye visualized with white light, or the two modalities in the reverse order, indocyanine green identified 50% more lymph nodes in both modified intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses, reported Michael Frumovitz, MD, from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and colleagues.

“Indocyanine green dye with near-infrared imaging identified significantly more sentinel nodes and more bilateral sentinel nodes than did isosulfan blue dye. It also identified all sentinel nodes with metastatic disease, whereas isosulfan blue dye missed a large proportion of them,” they wrote in the Lancet Oncology.

The FILM study was designed to determine whether fluorescent indocyanine green dye would be noninferior to isosulfan blue dye for accurately identifying sentinel lymph nodes in patients with cancer.

Although several single-center retrospective studies have reported on the use of interstitial injection of indocyanine green for lymphatic mapping in various solid tumors, including uterine and cervical cancers, there were no published studies comparing indocyanine green mapping to isosulfan blue mapping, the standard of care, the authors noted.

They enrolled 180 women aged 18 or older with clinical stage I endometrial or cervical cancers who were undergoing curative surgery and randomly assigned them as described above to have lymphatic mapping with each of the imaging modalities assigned in random order.

The patients but not the operators were masked as to the order of randomization.

Of the 180 patients enrolled, 176 received the intervention, and 13 of these patients were excluded because of major protocol violations, leaving 163 for a per-protocol analysis.

In the per-protocol analysis, 517 sentinel nodes were identified in the 163 patients, and of these, 478 (92%) were confirmed to be lymph nodes on pathological examination. This sample included 219 of 238 nodes identified with both blue and green dyes, all seven nodes revealed by blue dye alone, and 252 of 265 nodes identified by only green dye. Seven sentinel lymph nodes that were not identified by either dye were removed because they were enlarged or appeared suspicious on visual inspection.

In total, green dye identified 97% of lymph nodes in the per-protocol population, and blue dye identified 47%, an absolute difference of 50% (P less than .0001).

In the modified intention-to-treat population, which included all 176 patients randomized and treated, 545 nodes were identified, and 513 (94%) were confirmed to be lymph nodes on pathology. In this sample, 229 (92%) of 248 nodes showed both blue and green, nine nodes were blue only, and 266 (95%) of 279 were green only. Nine sentinel lymph nodes that were not revealed by either blue or green were removed for appearing suspicious or enlarged visually.

In total, in the modified-ITT analysis, 495 of 513 (96%) nodes were identified with the green dye and 238 (46%) were identified with the blue dye, again for an absolute difference of 50% (P less than .0001).

Based on the results of the study, the green dye’s maker, Novadaq Technologies, is submitting an application to the Food and Drug Administration for on-label use of interstitial injection of indocyanine green combined with near-infrared imaging for lymphatic mapping.

The study was funded by Novadaq. Dr. Frumovitz reported grants from Novadaq/Stryker during the conduct of the study, as well as personal fees; grants from Navidea; personal fees from Johnson & Johnson; and personal fees from Genentech outside the submitted work. The other authors declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Frumovitz M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30448-0.

FROM LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Fluorescent indocyanine green dye with near-infrared visualization was superior to isosulfan blue dye at identifying lymph nodes in patients with early-stage cervical and endometrial cancers.

Major finding: Indocyanine green identified 50% more lymph nodes than isosulfan blue, the standard of care.

Study details: Randomized, phase 3, within-patient, noninferiority trial in 176 women with clinical stage I endometrial or cervical cancers.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Novadaq. Dr. Frumovitz reported grants from Novadaq/Stryker during the conduct of the study, as well as personal fees; grants from Navidea, personal fees from Johnson & Johnson; and personal fees from Genentech outside the submitted work. The other authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Frumovitz M et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30448-0.

A Rare Case of Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma, Leg Type

CASE REPORT

A 74-year-old woman presented with a painful lesion on the left lower leg that was getting larger and more edematous and erythematous over the last 5 months. She experienced numbness and burning of the left lower leg 1 year prior to the development of the lesion. A review of her medical history revealed an otherwise healthy woman with no constitutional symptoms of fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or chest pain. The patient did not exhibit mucosal, genital, or nail involvement. Physical examination revealed a group of four 1-cm, ill-defined, irregularly bordered, violaceous plaques on the left anterior tibial leg with faint surrounding erythematous to violaceous patches (Figure 1). The plaques were tender to palpation with no bleeding or drainage.

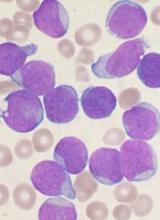

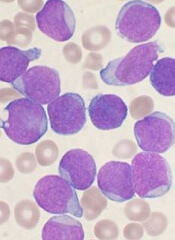

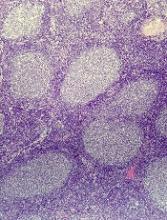

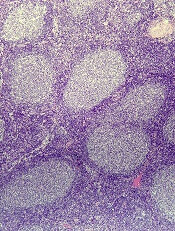

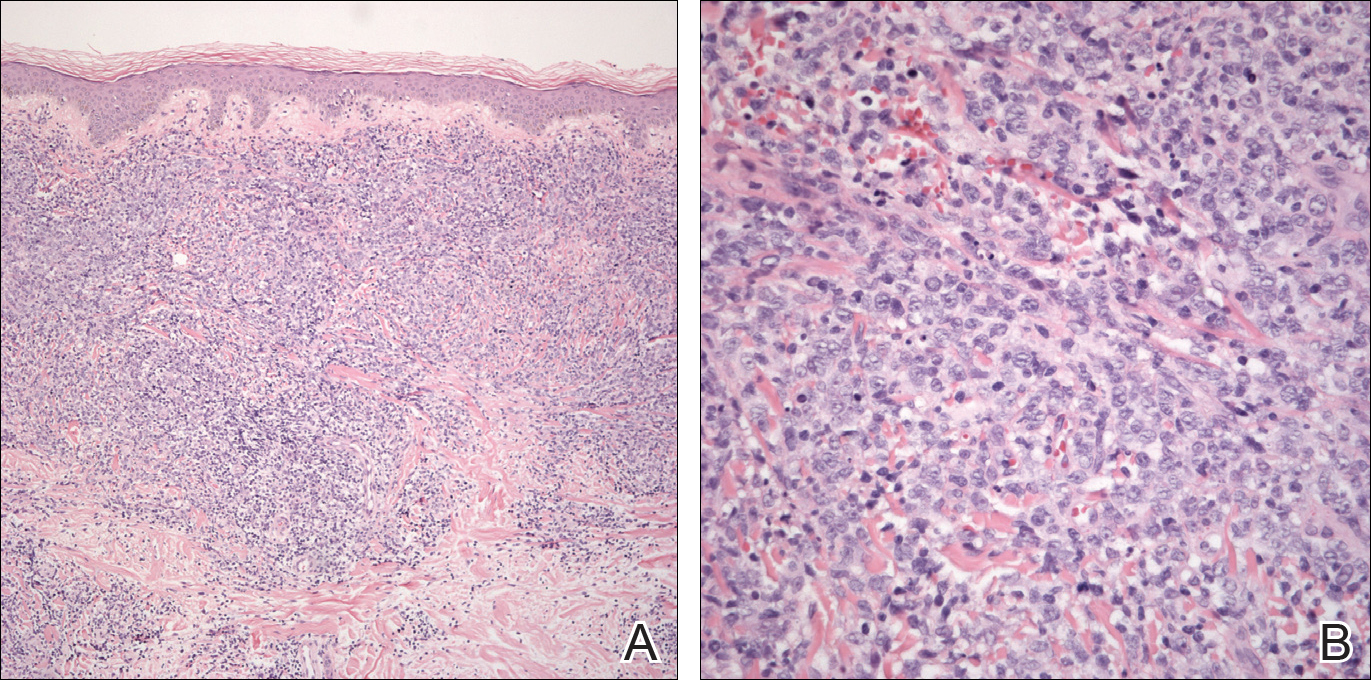

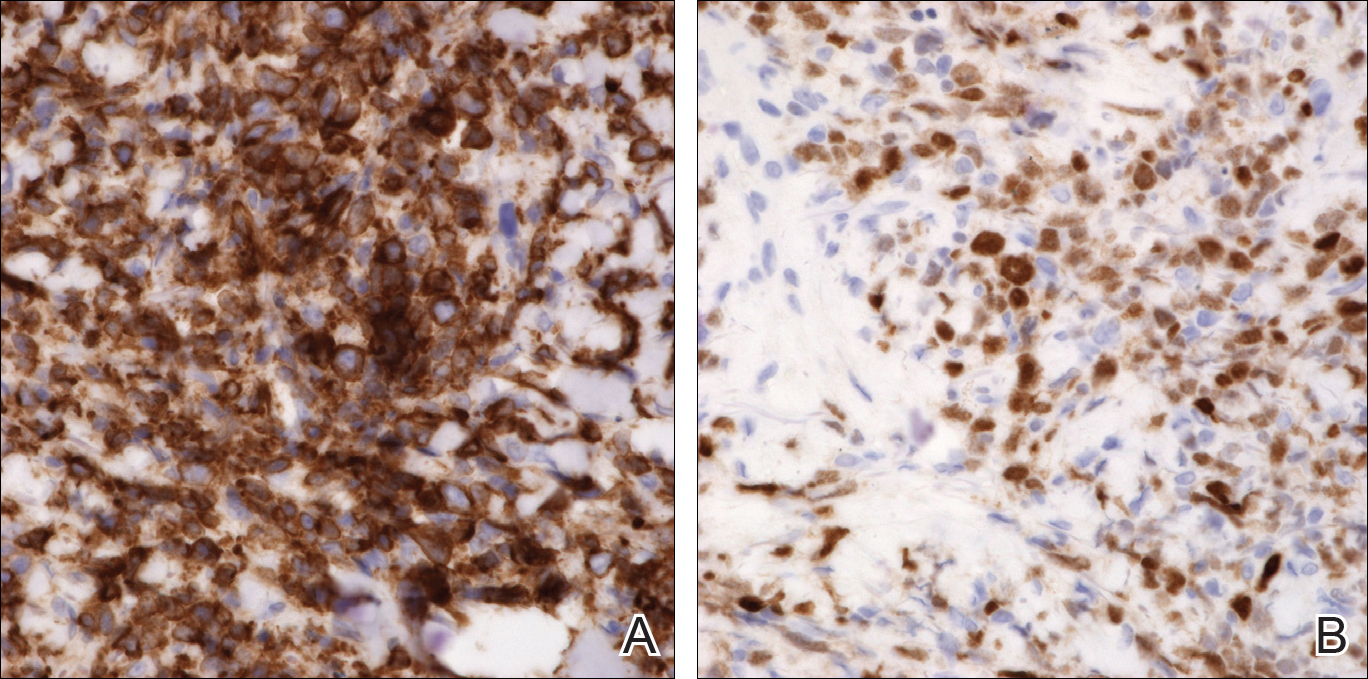

An 8.0-mm punch biopsy of the lesion was obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining on low-power magnification demonstrated a diffuse lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis and subcutis. Notable sparing of the subepidermal area (free grenz zone) was present (Figure 2A). On higher power, centroblasts and immunoblasts were visualized alongside extravasated red blood cells (Figure 2B). A diagnosis of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type (DLBCLLT) was made. Various immunohistochemical stains confirmed the diagnosis, including B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2)(Figure 3A) and multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1)(Figure 3B), which were highly positive in our patient. The patient had a negative bone marrow biopsy and positron emission tomography scan. She was started on rituximab infusions and multiple radiation treatments. At 2-year follow-up the lymphoma continued to recur despite radiation therapy.

COMMENT

Incidence and Clinical Characteristics

Primary cutaneous DLBCLLT is an intermediately aggressive form of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) that accounts for approximately 10% to 20% of all primary CBCLs and 1% to 3% of all cutaneous lymphomas.1 Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type primarily affects elderly patients (median age, 70 years). Women are more commonly affected. Clinically, primary cutaneous DLBCLLT presents as red-brown to bluish nodules or tumors on one or both distal legs.

Histopathology