User login

TYK2 inhibitors could treat ALCL, team says

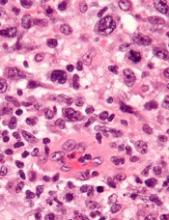

Preclinical research indicates that TYK2 inhibitors could be effective in treating anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL).

Researchers found evidence to suggest that TYK2 “is highly expressed in all cases of human ALCL.”

The team also discovered that TYK2 inhibition induces apoptosis in ALCL cells, and it delays tumor onset and prolongs survival in a mouse model of ALCL.

Olaf Merkel, PhD, of the Medical University of Vienna in Austria, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Leukemia.

The researchers said their analyses suggest TYK2 is expressed in all types of ALCL, regardless of ALK status, and TYK2 mediates the same anti-apoptotic response across ALCLs.

“Therefore, we could consider TYK2 signaling as the Achilles’ heel of ALCL, as, in all patients we have analyzed, the tumor cells relied on this activity to support the essential survival signal,” Dr. Merkel said.

He and his colleagues found that disrupting TYK2—either via gene knockdown or with small-molecule TYK2 inhibitors—induced apoptosis in human ALCL cells in vitro.

In a mouse model of NPM-ALK-induced lymphoma, Tyk2 deletion slowed the rate of tumor growth and significantly prolonged survival. The median survival was 53.3 weeks in mice with Tyk2 deletion and 16.0 weeks in control mice (P<0.0001).

Additional experiments in human ALCL cell lines showed that “TYK2 is activated by autocrine production of IL-10 and IL-22 and by interaction with specific receptors expressed by the cells,” the researchers said.

They also found that “activated TYK2 leads to STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation, activated expression of MCL1, and aberrant ALCL cell survival.”

Taking these findings together, the researchers concluded that TYK2 inhibitors could be effective for treating ALCL.

“We are looking forward to TYK2 inhibitors becoming available . . . ,” said study author Lukas Kenner, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna.

“[I]n the more rare lymphomas, we urgently need better therapies.”

Preclinical research indicates that TYK2 inhibitors could be effective in treating anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL).

Researchers found evidence to suggest that TYK2 “is highly expressed in all cases of human ALCL.”

The team also discovered that TYK2 inhibition induces apoptosis in ALCL cells, and it delays tumor onset and prolongs survival in a mouse model of ALCL.

Olaf Merkel, PhD, of the Medical University of Vienna in Austria, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Leukemia.

The researchers said their analyses suggest TYK2 is expressed in all types of ALCL, regardless of ALK status, and TYK2 mediates the same anti-apoptotic response across ALCLs.

“Therefore, we could consider TYK2 signaling as the Achilles’ heel of ALCL, as, in all patients we have analyzed, the tumor cells relied on this activity to support the essential survival signal,” Dr. Merkel said.

He and his colleagues found that disrupting TYK2—either via gene knockdown or with small-molecule TYK2 inhibitors—induced apoptosis in human ALCL cells in vitro.

In a mouse model of NPM-ALK-induced lymphoma, Tyk2 deletion slowed the rate of tumor growth and significantly prolonged survival. The median survival was 53.3 weeks in mice with Tyk2 deletion and 16.0 weeks in control mice (P<0.0001).

Additional experiments in human ALCL cell lines showed that “TYK2 is activated by autocrine production of IL-10 and IL-22 and by interaction with specific receptors expressed by the cells,” the researchers said.

They also found that “activated TYK2 leads to STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation, activated expression of MCL1, and aberrant ALCL cell survival.”

Taking these findings together, the researchers concluded that TYK2 inhibitors could be effective for treating ALCL.

“We are looking forward to TYK2 inhibitors becoming available . . . ,” said study author Lukas Kenner, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna.

“[I]n the more rare lymphomas, we urgently need better therapies.”

Preclinical research indicates that TYK2 inhibitors could be effective in treating anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL).

Researchers found evidence to suggest that TYK2 “is highly expressed in all cases of human ALCL.”

The team also discovered that TYK2 inhibition induces apoptosis in ALCL cells, and it delays tumor onset and prolongs survival in a mouse model of ALCL.

Olaf Merkel, PhD, of the Medical University of Vienna in Austria, and his colleagues detailed these findings in Leukemia.

The researchers said their analyses suggest TYK2 is expressed in all types of ALCL, regardless of ALK status, and TYK2 mediates the same anti-apoptotic response across ALCLs.

“Therefore, we could consider TYK2 signaling as the Achilles’ heel of ALCL, as, in all patients we have analyzed, the tumor cells relied on this activity to support the essential survival signal,” Dr. Merkel said.

He and his colleagues found that disrupting TYK2—either via gene knockdown or with small-molecule TYK2 inhibitors—induced apoptosis in human ALCL cells in vitro.

In a mouse model of NPM-ALK-induced lymphoma, Tyk2 deletion slowed the rate of tumor growth and significantly prolonged survival. The median survival was 53.3 weeks in mice with Tyk2 deletion and 16.0 weeks in control mice (P<0.0001).

Additional experiments in human ALCL cell lines showed that “TYK2 is activated by autocrine production of IL-10 and IL-22 and by interaction with specific receptors expressed by the cells,” the researchers said.

They also found that “activated TYK2 leads to STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation, activated expression of MCL1, and aberrant ALCL cell survival.”

Taking these findings together, the researchers concluded that TYK2 inhibitors could be effective for treating ALCL.

“We are looking forward to TYK2 inhibitors becoming available . . . ,” said study author Lukas Kenner, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna.

“[I]n the more rare lymphomas, we urgently need better therapies.”

Research may help explain how VOCs occur

Researchers say they have gained new insight that may help explain how vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) occur in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The team assessed how red blood cell (RBC) adhesion and polymerization of deoxygenated sickle hemoglobin affect the mechanisms underlying VOCs.

Experiments showed that hypoxia enhances sickle RBC adherence, and hemoglobin S polymerization enhances adherence for sickle reticulocytes and mature erythrocytes.

However, sickle reticulocytes have “unique adhesion dynamics” and therefore appear more likely to cause VOCs.

The researchers described these discoveries in an article set to be published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To investigate how RBCs interact with blood vessels to set off a VOC, the researchers built a microfluidic system that mimics post-capillary vessels. These vessels, which carry deoxygenated blood away from the capillaries, are where vaso-occlusions are most likely to occur.

The microfluidic system is designed to allow the researchers to control the oxygen level. The team used the system to test blood from eight SCD patients.

The researchers found that, under hypoxic conditions, sickle RBCs are two to four times more likely to adhere to the blood vessel walls than they are when oxygen levels are normal.

The team also found that hemoglobin S polymerization enhances the adherence of sickle reticulocytes and sickle mature erythrocytes. The hemoglobin S forms stiff fibers that grow and push the cell membrane outward, and these fibers help the cells adhere more firmly to the lining of the blood vessel.

“There has been little understanding of why, under hypoxia, there is much more adhesion,” said study author Subra Suresh, DSc, of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

“The experiments of this study provide some key insights into the processes and mechanisms responsible for increased adhesion.”

The researchers also found that, in SCD patients, reticulocytes are more likely than mature erythrocytes to adhere to blood vessels.

“We observed the growth of sickle hemoglobin fibers stretching reticulocytes within minutes,” said study author Dimitrios Papageorgiou, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

“It looks like they’re trying to grab more of the surface and adhere more strongly.”

The researchers said these and other findings suggest polymerization and adhesion stimulate each other.

The team now hopes to devise a more complete model of vaso-occlusion that combines their new findings with previous work. The previous work involved measuring how long it takes SCD patients’ blood cells to stiffen, making them more likely to block blood flow in tiny blood vessels.

The researchers also hope their findings might help them devise a way to predict VOCs in individual SCD patients.

Researchers say they have gained new insight that may help explain how vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) occur in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The team assessed how red blood cell (RBC) adhesion and polymerization of deoxygenated sickle hemoglobin affect the mechanisms underlying VOCs.

Experiments showed that hypoxia enhances sickle RBC adherence, and hemoglobin S polymerization enhances adherence for sickle reticulocytes and mature erythrocytes.

However, sickle reticulocytes have “unique adhesion dynamics” and therefore appear more likely to cause VOCs.

The researchers described these discoveries in an article set to be published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To investigate how RBCs interact with blood vessels to set off a VOC, the researchers built a microfluidic system that mimics post-capillary vessels. These vessels, which carry deoxygenated blood away from the capillaries, are where vaso-occlusions are most likely to occur.

The microfluidic system is designed to allow the researchers to control the oxygen level. The team used the system to test blood from eight SCD patients.

The researchers found that, under hypoxic conditions, sickle RBCs are two to four times more likely to adhere to the blood vessel walls than they are when oxygen levels are normal.

The team also found that hemoglobin S polymerization enhances the adherence of sickle reticulocytes and sickle mature erythrocytes. The hemoglobin S forms stiff fibers that grow and push the cell membrane outward, and these fibers help the cells adhere more firmly to the lining of the blood vessel.

“There has been little understanding of why, under hypoxia, there is much more adhesion,” said study author Subra Suresh, DSc, of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

“The experiments of this study provide some key insights into the processes and mechanisms responsible for increased adhesion.”

The researchers also found that, in SCD patients, reticulocytes are more likely than mature erythrocytes to adhere to blood vessels.

“We observed the growth of sickle hemoglobin fibers stretching reticulocytes within minutes,” said study author Dimitrios Papageorgiou, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

“It looks like they’re trying to grab more of the surface and adhere more strongly.”

The researchers said these and other findings suggest polymerization and adhesion stimulate each other.

The team now hopes to devise a more complete model of vaso-occlusion that combines their new findings with previous work. The previous work involved measuring how long it takes SCD patients’ blood cells to stiffen, making them more likely to block blood flow in tiny blood vessels.

The researchers also hope their findings might help them devise a way to predict VOCs in individual SCD patients.

Researchers say they have gained new insight that may help explain how vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs) occur in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

The team assessed how red blood cell (RBC) adhesion and polymerization of deoxygenated sickle hemoglobin affect the mechanisms underlying VOCs.

Experiments showed that hypoxia enhances sickle RBC adherence, and hemoglobin S polymerization enhances adherence for sickle reticulocytes and mature erythrocytes.

However, sickle reticulocytes have “unique adhesion dynamics” and therefore appear more likely to cause VOCs.

The researchers described these discoveries in an article set to be published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To investigate how RBCs interact with blood vessels to set off a VOC, the researchers built a microfluidic system that mimics post-capillary vessels. These vessels, which carry deoxygenated blood away from the capillaries, are where vaso-occlusions are most likely to occur.

The microfluidic system is designed to allow the researchers to control the oxygen level. The team used the system to test blood from eight SCD patients.

The researchers found that, under hypoxic conditions, sickle RBCs are two to four times more likely to adhere to the blood vessel walls than they are when oxygen levels are normal.

The team also found that hemoglobin S polymerization enhances the adherence of sickle reticulocytes and sickle mature erythrocytes. The hemoglobin S forms stiff fibers that grow and push the cell membrane outward, and these fibers help the cells adhere more firmly to the lining of the blood vessel.

“There has been little understanding of why, under hypoxia, there is much more adhesion,” said study author Subra Suresh, DSc, of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

“The experiments of this study provide some key insights into the processes and mechanisms responsible for increased adhesion.”

The researchers also found that, in SCD patients, reticulocytes are more likely than mature erythrocytes to adhere to blood vessels.

“We observed the growth of sickle hemoglobin fibers stretching reticulocytes within minutes,” said study author Dimitrios Papageorgiou, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

“It looks like they’re trying to grab more of the surface and adhere more strongly.”

The researchers said these and other findings suggest polymerization and adhesion stimulate each other.

The team now hopes to devise a more complete model of vaso-occlusion that combines their new findings with previous work. The previous work involved measuring how long it takes SCD patients’ blood cells to stiffen, making them more likely to block blood flow in tiny blood vessels.

The researchers also hope their findings might help them devise a way to predict VOCs in individual SCD patients.

Study authors fail to disclose industry payments

New research suggests investigators involved in oncology trials sometimes fail to disclose payments from the pharmaceutical industry.

Researchers looked at clinical trials associated with cancer drugs recently approved in the United States and assessed whether funding was properly disclosed when the trial results were published in scientific journals.

The data showed that roughly a third of investigators failed to completely disclose payments from trial sponsors.

“We know that pharmaceutical companies sponsor trials of their own drugs. That’s not a surprise,” said Cole Wayant, a DO/PhD student at Oklahoma State University in Tulsa.

“But what is a surprise, and what warrants concern, is that this funding is often not disclosed in the publication of clinical trials that form the basis of FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] approvals and clinical practice guidelines.”

Wayant and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the findings in a letter to JAMA Oncology.

The researchers began by searching the FDA Hematology/Oncology (Cancer) Approvals & Safety Notifications website for oncology drugs approved from Jan. 1, 2016, to Aug. 31, 2017.

The team then identified the published trials supporting these drug approvals and searched the Open Payments website for industry payment data for each U.S.-based oncologist involved in the trials.

Finally, the researchers compared the Open Payments data to the disclosure statements from the publications.

There were 344 authors of clinical trials associated with oncology drugs approved during the period studied. Most authors (76.5%) received at least one industry payment, and the total amount they received exceeded $216 million.

Nearly a third of the authors (32%, n=110) did not fully disclose payments from a trial sponsor.

In all, the authors received about $6.3 million in general payments (e.g., speaking fees), and $1.7 million of that was undisclosed.

They received more than $500,000 in research payments (e.g., fees for study coordination), and more than $200,000 of that was undisclosed.

The authors received close to $210 million in associated research payments (e.g., grants), and about $78 million of that was undisclosed.

Wayant and his colleagues said these results suggest financial relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and oncology trial investigators “may be common, expensive, and frequently undisclosed.” However, the research also suggests Open Payments data could be used to ensure complete disclosure of industry payments.

New research suggests investigators involved in oncology trials sometimes fail to disclose payments from the pharmaceutical industry.

Researchers looked at clinical trials associated with cancer drugs recently approved in the United States and assessed whether funding was properly disclosed when the trial results were published in scientific journals.

The data showed that roughly a third of investigators failed to completely disclose payments from trial sponsors.

“We know that pharmaceutical companies sponsor trials of their own drugs. That’s not a surprise,” said Cole Wayant, a DO/PhD student at Oklahoma State University in Tulsa.

“But what is a surprise, and what warrants concern, is that this funding is often not disclosed in the publication of clinical trials that form the basis of FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] approvals and clinical practice guidelines.”

Wayant and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the findings in a letter to JAMA Oncology.

The researchers began by searching the FDA Hematology/Oncology (Cancer) Approvals & Safety Notifications website for oncology drugs approved from Jan. 1, 2016, to Aug. 31, 2017.

The team then identified the published trials supporting these drug approvals and searched the Open Payments website for industry payment data for each U.S.-based oncologist involved in the trials.

Finally, the researchers compared the Open Payments data to the disclosure statements from the publications.

There were 344 authors of clinical trials associated with oncology drugs approved during the period studied. Most authors (76.5%) received at least one industry payment, and the total amount they received exceeded $216 million.

Nearly a third of the authors (32%, n=110) did not fully disclose payments from a trial sponsor.

In all, the authors received about $6.3 million in general payments (e.g., speaking fees), and $1.7 million of that was undisclosed.

They received more than $500,000 in research payments (e.g., fees for study coordination), and more than $200,000 of that was undisclosed.

The authors received close to $210 million in associated research payments (e.g., grants), and about $78 million of that was undisclosed.

Wayant and his colleagues said these results suggest financial relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and oncology trial investigators “may be common, expensive, and frequently undisclosed.” However, the research also suggests Open Payments data could be used to ensure complete disclosure of industry payments.

New research suggests investigators involved in oncology trials sometimes fail to disclose payments from the pharmaceutical industry.

Researchers looked at clinical trials associated with cancer drugs recently approved in the United States and assessed whether funding was properly disclosed when the trial results were published in scientific journals.

The data showed that roughly a third of investigators failed to completely disclose payments from trial sponsors.

“We know that pharmaceutical companies sponsor trials of their own drugs. That’s not a surprise,” said Cole Wayant, a DO/PhD student at Oklahoma State University in Tulsa.

“But what is a surprise, and what warrants concern, is that this funding is often not disclosed in the publication of clinical trials that form the basis of FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] approvals and clinical practice guidelines.”

Wayant and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the findings in a letter to JAMA Oncology.

The researchers began by searching the FDA Hematology/Oncology (Cancer) Approvals & Safety Notifications website for oncology drugs approved from Jan. 1, 2016, to Aug. 31, 2017.

The team then identified the published trials supporting these drug approvals and searched the Open Payments website for industry payment data for each U.S.-based oncologist involved in the trials.

Finally, the researchers compared the Open Payments data to the disclosure statements from the publications.

There were 344 authors of clinical trials associated with oncology drugs approved during the period studied. Most authors (76.5%) received at least one industry payment, and the total amount they received exceeded $216 million.

Nearly a third of the authors (32%, n=110) did not fully disclose payments from a trial sponsor.

In all, the authors received about $6.3 million in general payments (e.g., speaking fees), and $1.7 million of that was undisclosed.

They received more than $500,000 in research payments (e.g., fees for study coordination), and more than $200,000 of that was undisclosed.

The authors received close to $210 million in associated research payments (e.g., grants), and about $78 million of that was undisclosed.

Wayant and his colleagues said these results suggest financial relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and oncology trial investigators “may be common, expensive, and frequently undisclosed.” However, the research also suggests Open Payments data could be used to ensure complete disclosure of industry payments.

Community-based therapy improved asthma outcomes in African American teens

, according to results published in Pediatrics.

In a study of 167 African American patients aged 12-16 years, the 84 randomly assigned to Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care (MST-HC) had greater improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) over time, compared with the 83 patients randomly assigned to family support (FS) therapy (beta = 0.097, t[164.27] = 2.52; P = .01). Improvements in secondary outcomes also were observed in this group, reported Sylvie Naar, PhD, of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and her coauthors.

They studied African American adolescents with moderate to severe persistent asthma who resided in a home setting with a caregiver and were at high risk for poorly controlled asthma. Families were randomized to either MST-HC (84 patients) or FS (83 patients) based on severity of urgent care use, and follow-up was completed 7 and 12 months after baseline assessment. Families were paid $50 for each assessment.

FEV1 was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were medication adherence, symptom severity and frequency, inpatient hospitalizations, and ED visits. Medication adherence was evaluated via the Family Asthma Management System Scale (FAMSS) and the Daily Phone Diary (DPD). Other outcomes were confirmed via medical records.

Patients in the FS control group received weekly home-based counseling for up to 6 months. Patients in the MST-HC treatment group were first engaged in a motivational session with a therapist and evaluated for asthma management with interviews and observations within the home and community. Once possible contributing factors to poor asthma management (such as medication underuse or low parental monitoring) were identified, targeted interventions such as skills training, behavioral and family therapy, or communication training with school and medical staff were chosen, and treatment goals continually monitored and modified, the authors said.

The mean length of treatment until termination in the MST-HC group was 5 months, and the mean number of sessions was 27. In the FS group, mean length of treatment was 4 months, and the mean number of sessions was 11.

FEV1 for the MST-HC group improved from 2.05 at baseline to 2.25 at 7 months (a 10% improvement), and to 2.37 (a 16% improvement) at 12 months, compared with an improvement from 2.21 to 2.31 at 7 months (a 4% improvement) and 2.33 (a 5% improvement) at 12 months in the control group, the authors reported.

At 12 months, FAMSS adherence scores improved from 4.19 to 5.24 in the MST-HC group and from 4.61 to 4.72 in the control group.

DPD adherence scores improved from a mean of 0.33 at baseline to 0.69 for the MST-HC group, and from 0.43 to 0.46 in the FS group.

At 12 months, the mean frequency of asthma symptoms in the MST-HC group improved from 2.75 at baseline to 1.43, compared with a decline of 2.67 to 2.58 in the control group. The mean number of hospitalizations in the MST-HC group improved from 0.87 to 0.24, compared with a change from 0.66 to 0.34 in the control group.

The study results are “especially noteworthy because African American adolescents experience greater morbidity and mortality from asthma than white adolescents even when controlling for socioeconomic variables,” Dr. Naar and her associates wrote. Future research should focus on the “transportability” of MST-HC treatment to community settings, which is “ready to be studied in effectiveness and implementation trials.”

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Coauthor Phillippe Cunningham, PhD, is a co-owner of Evidence-Based Services, a network partner organization that is licensed to disseminate Multisystemic Therapy for drug court and juvenile delinquency settings. The other authors said they have no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Naar S et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3737.

, according to results published in Pediatrics.

In a study of 167 African American patients aged 12-16 years, the 84 randomly assigned to Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care (MST-HC) had greater improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) over time, compared with the 83 patients randomly assigned to family support (FS) therapy (beta = 0.097, t[164.27] = 2.52; P = .01). Improvements in secondary outcomes also were observed in this group, reported Sylvie Naar, PhD, of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and her coauthors.

They studied African American adolescents with moderate to severe persistent asthma who resided in a home setting with a caregiver and were at high risk for poorly controlled asthma. Families were randomized to either MST-HC (84 patients) or FS (83 patients) based on severity of urgent care use, and follow-up was completed 7 and 12 months after baseline assessment. Families were paid $50 for each assessment.

FEV1 was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were medication adherence, symptom severity and frequency, inpatient hospitalizations, and ED visits. Medication adherence was evaluated via the Family Asthma Management System Scale (FAMSS) and the Daily Phone Diary (DPD). Other outcomes were confirmed via medical records.

Patients in the FS control group received weekly home-based counseling for up to 6 months. Patients in the MST-HC treatment group were first engaged in a motivational session with a therapist and evaluated for asthma management with interviews and observations within the home and community. Once possible contributing factors to poor asthma management (such as medication underuse or low parental monitoring) were identified, targeted interventions such as skills training, behavioral and family therapy, or communication training with school and medical staff were chosen, and treatment goals continually monitored and modified, the authors said.

The mean length of treatment until termination in the MST-HC group was 5 months, and the mean number of sessions was 27. In the FS group, mean length of treatment was 4 months, and the mean number of sessions was 11.

FEV1 for the MST-HC group improved from 2.05 at baseline to 2.25 at 7 months (a 10% improvement), and to 2.37 (a 16% improvement) at 12 months, compared with an improvement from 2.21 to 2.31 at 7 months (a 4% improvement) and 2.33 (a 5% improvement) at 12 months in the control group, the authors reported.

At 12 months, FAMSS adherence scores improved from 4.19 to 5.24 in the MST-HC group and from 4.61 to 4.72 in the control group.

DPD adherence scores improved from a mean of 0.33 at baseline to 0.69 for the MST-HC group, and from 0.43 to 0.46 in the FS group.

At 12 months, the mean frequency of asthma symptoms in the MST-HC group improved from 2.75 at baseline to 1.43, compared with a decline of 2.67 to 2.58 in the control group. The mean number of hospitalizations in the MST-HC group improved from 0.87 to 0.24, compared with a change from 0.66 to 0.34 in the control group.

The study results are “especially noteworthy because African American adolescents experience greater morbidity and mortality from asthma than white adolescents even when controlling for socioeconomic variables,” Dr. Naar and her associates wrote. Future research should focus on the “transportability” of MST-HC treatment to community settings, which is “ready to be studied in effectiveness and implementation trials.”

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Coauthor Phillippe Cunningham, PhD, is a co-owner of Evidence-Based Services, a network partner organization that is licensed to disseminate Multisystemic Therapy for drug court and juvenile delinquency settings. The other authors said they have no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Naar S et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3737.

, according to results published in Pediatrics.

In a study of 167 African American patients aged 12-16 years, the 84 randomly assigned to Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care (MST-HC) had greater improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) over time, compared with the 83 patients randomly assigned to family support (FS) therapy (beta = 0.097, t[164.27] = 2.52; P = .01). Improvements in secondary outcomes also were observed in this group, reported Sylvie Naar, PhD, of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and her coauthors.

They studied African American adolescents with moderate to severe persistent asthma who resided in a home setting with a caregiver and were at high risk for poorly controlled asthma. Families were randomized to either MST-HC (84 patients) or FS (83 patients) based on severity of urgent care use, and follow-up was completed 7 and 12 months after baseline assessment. Families were paid $50 for each assessment.

FEV1 was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were medication adherence, symptom severity and frequency, inpatient hospitalizations, and ED visits. Medication adherence was evaluated via the Family Asthma Management System Scale (FAMSS) and the Daily Phone Diary (DPD). Other outcomes were confirmed via medical records.

Patients in the FS control group received weekly home-based counseling for up to 6 months. Patients in the MST-HC treatment group were first engaged in a motivational session with a therapist and evaluated for asthma management with interviews and observations within the home and community. Once possible contributing factors to poor asthma management (such as medication underuse or low parental monitoring) were identified, targeted interventions such as skills training, behavioral and family therapy, or communication training with school and medical staff were chosen, and treatment goals continually monitored and modified, the authors said.

The mean length of treatment until termination in the MST-HC group was 5 months, and the mean number of sessions was 27. In the FS group, mean length of treatment was 4 months, and the mean number of sessions was 11.

FEV1 for the MST-HC group improved from 2.05 at baseline to 2.25 at 7 months (a 10% improvement), and to 2.37 (a 16% improvement) at 12 months, compared with an improvement from 2.21 to 2.31 at 7 months (a 4% improvement) and 2.33 (a 5% improvement) at 12 months in the control group, the authors reported.

At 12 months, FAMSS adherence scores improved from 4.19 to 5.24 in the MST-HC group and from 4.61 to 4.72 in the control group.

DPD adherence scores improved from a mean of 0.33 at baseline to 0.69 for the MST-HC group, and from 0.43 to 0.46 in the FS group.

At 12 months, the mean frequency of asthma symptoms in the MST-HC group improved from 2.75 at baseline to 1.43, compared with a decline of 2.67 to 2.58 in the control group. The mean number of hospitalizations in the MST-HC group improved from 0.87 to 0.24, compared with a change from 0.66 to 0.34 in the control group.

The study results are “especially noteworthy because African American adolescents experience greater morbidity and mortality from asthma than white adolescents even when controlling for socioeconomic variables,” Dr. Naar and her associates wrote. Future research should focus on the “transportability” of MST-HC treatment to community settings, which is “ready to be studied in effectiveness and implementation trials.”

The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Coauthor Phillippe Cunningham, PhD, is a co-owner of Evidence-Based Services, a network partner organization that is licensed to disseminate Multisystemic Therapy for drug court and juvenile delinquency settings. The other authors said they have no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Naar S et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3737.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Multisystemic Therapy–Health Care (MST-HC) significantly improved outcomes in African American adolescents with moderate to severe asthma.

Major finding: Patients randomly assigned to MST-HC treatment had greater improvement in FEV1 over time, compared with controls (beta = 0.097; t(164.27) = 2.52; P = .01).

Study details: A study of 167 African American patients aged 12-16 years, randomly assigned to either MST-HC or FS.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant. Coauthor Phillippe Cunningham, PhD, is a co-owner of Evidence-Based Services, a network partner organization that is licensed to disseminate multisystemic therapy for drug court and juvenile delinquency settings. The other authors said they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Naar S et al. Pediatrics. 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3737.

No Walk in the Park

ANSWER

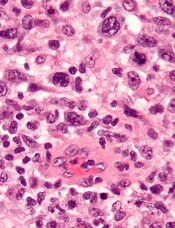

This ECG demonstrates sinus rhythm with second-degree type II block, right-axis deviation, and ST-T wave changes in the inferior leads, suggestive of ischemia. A P-P interval of 100 beats/min meets the criteria for sinus rhythm.

Second-degree type II block is evidenced by two P waves for each QRS complex with a consistent PR interval. In this example, the PR interval is significantly prolonged at 415 ms. Normally, this would be a rather impressive first-degree AV block. However, a second P wave (integrated in the ST interval, best seen in the rhythm strip at the bottom) makes this second-degree type II block.

Right-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of 90° to 180°; thus this patient qualifies at 131°. Finally, ST-T wave depressions are evident in leads II, III, and aVF, suggestive but not indicative of inferior ischemia. The patient was found to have a recurrent perivalvular abscess of his artificial aortic valve, as well as right lower lobe pneumonia.

ANSWER

This ECG demonstrates sinus rhythm with second-degree type II block, right-axis deviation, and ST-T wave changes in the inferior leads, suggestive of ischemia. A P-P interval of 100 beats/min meets the criteria for sinus rhythm.

Second-degree type II block is evidenced by two P waves for each QRS complex with a consistent PR interval. In this example, the PR interval is significantly prolonged at 415 ms. Normally, this would be a rather impressive first-degree AV block. However, a second P wave (integrated in the ST interval, best seen in the rhythm strip at the bottom) makes this second-degree type II block.

Right-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of 90° to 180°; thus this patient qualifies at 131°. Finally, ST-T wave depressions are evident in leads II, III, and aVF, suggestive but not indicative of inferior ischemia. The patient was found to have a recurrent perivalvular abscess of his artificial aortic valve, as well as right lower lobe pneumonia.

ANSWER

This ECG demonstrates sinus rhythm with second-degree type II block, right-axis deviation, and ST-T wave changes in the inferior leads, suggestive of ischemia. A P-P interval of 100 beats/min meets the criteria for sinus rhythm.

Second-degree type II block is evidenced by two P waves for each QRS complex with a consistent PR interval. In this example, the PR interval is significantly prolonged at 415 ms. Normally, this would be a rather impressive first-degree AV block. However, a second P wave (integrated in the ST interval, best seen in the rhythm strip at the bottom) makes this second-degree type II block.

Right-axis deviation is defined by an R-wave axis of 90° to 180°; thus this patient qualifies at 131°. Finally, ST-T wave depressions are evident in leads II, III, and aVF, suggestive but not indicative of inferior ischemia. The patient was found to have a recurrent perivalvular abscess of his artificial aortic valve, as well as right lower lobe pneumonia.

A 47-year-old man is transported to your facility by ACLS ambulance after being found unresponsive in a public park. When aggressive attempts to wake him were unsuccessful, the paramedics intubated the patient. His heart rhythm was regular at 50 beats/min, and tissues were pink with good capillary refill, suggesting he was perfusing well.

On his arrival, you realize you have encountered the patient before. He has a history of chronic intravenous (IV) drug use and group B Streptococcus endocarditis; the latter was complicated by a perivalvular abscess that required replacement with a bioprosthetic aortic valve about eight months ago. His postoperative course was complicated by intermittent atrial fibrillation with conversion pauses of 4 sec. An electrophysiology consult, for possible permanent pacemaker placement, was obtained—but the patient left against medical advice before being seen. He has been lost to follow-up since.

Today’s review of the electronic medical record identifies an allergy to sulfa and IV contrast. He has been enrolled in a methadone clinic but has not been seen there for the past month. Further history, pharmacologic regimen, and review of systems are unobtainable, as the patient is sedated and intubated.

Physical examination reveals an unconscious, unresponsive, malnourished male. His blood pressure is 96/54 mm Hg; pulse, 50 beats/min; temperature, 38.6°C; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min-1 (ventilated); and O2 saturation, 100%. He has multiple tattoos over his upper and lower extremities and torso. Examination of the extremities reveals old and new needle tracks, with dense scarring in both antecubital fossae.

The HEENT exam is remarkable for poor dentition with multiple missing teeth and a perforated nasal septum. The neck veins are distended to the angle of the jaw. Auscultation of the lungs reveals coarse, rhonchorous mechanical breath sounds with absent breath sounds in the right base.

The cardiac exam is positive for a grade IV/VI holosystolic murmur, best heard in the left upper sternal border. The abdomen is scaphoid, and a firm liver edge is palpable 2 cm below the right costal margin. The right knee is inflamed and erythematous, with palpable fluid. The neurologic exam documents that both pupils are reactive to light.

Laboratory data reveal a positive toxicology screen for cocaine, methadone, and opioids. He also has a leukocytosis level of 24,500/µL. A supine single-view chest x-ray shows consolidation of the right lower lobe and multiple perihilar nodules that were present on a previous chest x-ray.

An ECG shows a ventricular rate of 50 beats/min; PR interval, 415 ms; QRS duration, 102 ms; QT/QTc interval, 456/415 ms; P axis, 67°; R axis, 131°; and T axis, –29°. What is your interpretation?

Diclofenac’s cardiovascular risk confirmed in novel Nordic study

Those beginning diclofenac had a 50% increased 30-day risk for a composite outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared with individuals who didn’t initiate an NSAID or acetaminophen (95% confidence interval for incidence rate ratio, 1.4-1.7).

The risk was still significantly elevated when the study’s first author, Morten Schmidt, MD, and his colleagues compared diclofenac initiation with beginning other NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Compared with those starting ibuprofen or acetaminophen, the MACE risk was elevated 20% in diclofenac initiators (95% CI, 1.1-1.3 for both). Initiating diclofenac was associated with 30% greater risk for MACE compared with initiating naproxen (95% CI, 1.1-1.5).

“Diclofenac is the most frequently used NSAID in low-, middle-, and high-income countries and is available over the counter in most countries; therefore, its cardiovascular risk profile is of major clinical and public health importance,” wrote Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

In all, the study included 1,370,832 individuals who initiated diclofenac, 3,878,454 ibuprofen initiators, 291,490 naproxen initiators, and 764,781 acetaminophen initiators. Those starting diclofenac were compared with those starting other medications, and with 1,303,209 individuals who sought health care but did not start one of the medications.

The researchers used the longstanding and complete Danish health registry system to their advantage in designing a cohort trial that was modeled to resemble a clinical trial. For each month, beginning in 1996 and continuing through 2016, Dr. Schmidt and his collaborators assembled propensity-matched cohorts of individuals to compare each study group. The study design achieved many of the aims of a clinical trial while working within the ethical constraints of studying medications now known to elevate cardiovascular risk.

For each 30-day period, the investigators were then able to track and compare cardiovascular outcomes for each group. Each month, data for a new cohort were collected, beginning a new “clinical trial.” Individuals could be included in more than one month’s worth of “trial” data as long as they continued to meet inclusion criteria.

The completeness of Danish health data meant that the researchers were confident in data about comorbidities, other prescription medications, and outcomes.

Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses to look at the extent to which preexisting risks for cardiovascular disease mediated MACE risk on diclofenac initiation. They found that diclofenac initiators in the highest risk group had up to 40 excess cardiovascular events per year – about half of them fatal – that were attributable to starting the medication. Although that group had the highest absolute risk, however, “the relative risks were highest in those with the lowest baseline risk,” wrote the investigators.

In addition to looking at rates of MACE, secondary outcomes for the study included evaluating the association between medication use or non-use and each individual component of the composite primary outcome. These included first-time occurrences of the nonfatal endpoints of atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic (but not hemorrhagic) stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction. Cardiac death was death from any cardiac cause.

“Supporting use of a combined endpoint, event rates consistently increased for all individual outcomes” for diclofenac initiators compared with those who did not start an NSAID, wrote Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues.

Individuals were excluded if they had known cardiovascular, kidney, liver, or ulcer disease, and if they had malignancy or serious mental health diagnoses such as dementia or schizophrenia. Participants, aged a mean 48-56 years, had to be at least 18 years of age and could not have filled a prescription for an NSAID within the previous 12 months. Men made up 36.6%-46.3% of the cohorts.

Dr. Schmidt, of Aarhus (Denmark) University, and his collaborators said that in comparison with other NSAIDs, the short half-life of diclofenac means that a supratherapeutic plasma concentration of diclofenac soon after initiation achieves not just cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), but also COX-1 inhibition. However, after those high levels fall, patients taking diclofenac spend a substantial period of time with unopposed COX-2 inhibition, a state that is known to be prothrombotic, and also associated with blood pressure elevation, atherogenesis, and worsening of heart failure.

Diclofenac and ibuprofen had similar gastrointestinal bleeding risks, and both medications were associated with a higher risk of bleeding than were ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or no medication.

“Comparing diclofenac initiation with no NSAID initiation, the consistency between our results and those of previous meta-analyses of both trial and observational data provides strong evidence to guide clinical decision making,” said Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

“Considering its cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks, however, there is little justification to initiate diclofenac treatment before other traditional NSAIDs,” noted the investigators. “It is time to acknowledge the potential health risk of diclofenac and to reduce its use.”

The study was funded by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology Research Foundation, University of Aarhus, and by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Danish Research Council. The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schmidt M et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3426

Those beginning diclofenac had a 50% increased 30-day risk for a composite outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared with individuals who didn’t initiate an NSAID or acetaminophen (95% confidence interval for incidence rate ratio, 1.4-1.7).

The risk was still significantly elevated when the study’s first author, Morten Schmidt, MD, and his colleagues compared diclofenac initiation with beginning other NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Compared with those starting ibuprofen or acetaminophen, the MACE risk was elevated 20% in diclofenac initiators (95% CI, 1.1-1.3 for both). Initiating diclofenac was associated with 30% greater risk for MACE compared with initiating naproxen (95% CI, 1.1-1.5).

“Diclofenac is the most frequently used NSAID in low-, middle-, and high-income countries and is available over the counter in most countries; therefore, its cardiovascular risk profile is of major clinical and public health importance,” wrote Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

In all, the study included 1,370,832 individuals who initiated diclofenac, 3,878,454 ibuprofen initiators, 291,490 naproxen initiators, and 764,781 acetaminophen initiators. Those starting diclofenac were compared with those starting other medications, and with 1,303,209 individuals who sought health care but did not start one of the medications.

The researchers used the longstanding and complete Danish health registry system to their advantage in designing a cohort trial that was modeled to resemble a clinical trial. For each month, beginning in 1996 and continuing through 2016, Dr. Schmidt and his collaborators assembled propensity-matched cohorts of individuals to compare each study group. The study design achieved many of the aims of a clinical trial while working within the ethical constraints of studying medications now known to elevate cardiovascular risk.

For each 30-day period, the investigators were then able to track and compare cardiovascular outcomes for each group. Each month, data for a new cohort were collected, beginning a new “clinical trial.” Individuals could be included in more than one month’s worth of “trial” data as long as they continued to meet inclusion criteria.

The completeness of Danish health data meant that the researchers were confident in data about comorbidities, other prescription medications, and outcomes.

Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses to look at the extent to which preexisting risks for cardiovascular disease mediated MACE risk on diclofenac initiation. They found that diclofenac initiators in the highest risk group had up to 40 excess cardiovascular events per year – about half of them fatal – that were attributable to starting the medication. Although that group had the highest absolute risk, however, “the relative risks were highest in those with the lowest baseline risk,” wrote the investigators.

In addition to looking at rates of MACE, secondary outcomes for the study included evaluating the association between medication use or non-use and each individual component of the composite primary outcome. These included first-time occurrences of the nonfatal endpoints of atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic (but not hemorrhagic) stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction. Cardiac death was death from any cardiac cause.

“Supporting use of a combined endpoint, event rates consistently increased for all individual outcomes” for diclofenac initiators compared with those who did not start an NSAID, wrote Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues.

Individuals were excluded if they had known cardiovascular, kidney, liver, or ulcer disease, and if they had malignancy or serious mental health diagnoses such as dementia or schizophrenia. Participants, aged a mean 48-56 years, had to be at least 18 years of age and could not have filled a prescription for an NSAID within the previous 12 months. Men made up 36.6%-46.3% of the cohorts.

Dr. Schmidt, of Aarhus (Denmark) University, and his collaborators said that in comparison with other NSAIDs, the short half-life of diclofenac means that a supratherapeutic plasma concentration of diclofenac soon after initiation achieves not just cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), but also COX-1 inhibition. However, after those high levels fall, patients taking diclofenac spend a substantial period of time with unopposed COX-2 inhibition, a state that is known to be prothrombotic, and also associated with blood pressure elevation, atherogenesis, and worsening of heart failure.

Diclofenac and ibuprofen had similar gastrointestinal bleeding risks, and both medications were associated with a higher risk of bleeding than were ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or no medication.

“Comparing diclofenac initiation with no NSAID initiation, the consistency between our results and those of previous meta-analyses of both trial and observational data provides strong evidence to guide clinical decision making,” said Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

“Considering its cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks, however, there is little justification to initiate diclofenac treatment before other traditional NSAIDs,” noted the investigators. “It is time to acknowledge the potential health risk of diclofenac and to reduce its use.”

The study was funded by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology Research Foundation, University of Aarhus, and by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Danish Research Council. The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schmidt M et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3426

Those beginning diclofenac had a 50% increased 30-day risk for a composite outcome of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared with individuals who didn’t initiate an NSAID or acetaminophen (95% confidence interval for incidence rate ratio, 1.4-1.7).

The risk was still significantly elevated when the study’s first author, Morten Schmidt, MD, and his colleagues compared diclofenac initiation with beginning other NSAIDs or acetaminophen. Compared with those starting ibuprofen or acetaminophen, the MACE risk was elevated 20% in diclofenac initiators (95% CI, 1.1-1.3 for both). Initiating diclofenac was associated with 30% greater risk for MACE compared with initiating naproxen (95% CI, 1.1-1.5).

“Diclofenac is the most frequently used NSAID in low-, middle-, and high-income countries and is available over the counter in most countries; therefore, its cardiovascular risk profile is of major clinical and public health importance,” wrote Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

In all, the study included 1,370,832 individuals who initiated diclofenac, 3,878,454 ibuprofen initiators, 291,490 naproxen initiators, and 764,781 acetaminophen initiators. Those starting diclofenac were compared with those starting other medications, and with 1,303,209 individuals who sought health care but did not start one of the medications.

The researchers used the longstanding and complete Danish health registry system to their advantage in designing a cohort trial that was modeled to resemble a clinical trial. For each month, beginning in 1996 and continuing through 2016, Dr. Schmidt and his collaborators assembled propensity-matched cohorts of individuals to compare each study group. The study design achieved many of the aims of a clinical trial while working within the ethical constraints of studying medications now known to elevate cardiovascular risk.

For each 30-day period, the investigators were then able to track and compare cardiovascular outcomes for each group. Each month, data for a new cohort were collected, beginning a new “clinical trial.” Individuals could be included in more than one month’s worth of “trial” data as long as they continued to meet inclusion criteria.

The completeness of Danish health data meant that the researchers were confident in data about comorbidities, other prescription medications, and outcomes.

Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses to look at the extent to which preexisting risks for cardiovascular disease mediated MACE risk on diclofenac initiation. They found that diclofenac initiators in the highest risk group had up to 40 excess cardiovascular events per year – about half of them fatal – that were attributable to starting the medication. Although that group had the highest absolute risk, however, “the relative risks were highest in those with the lowest baseline risk,” wrote the investigators.

In addition to looking at rates of MACE, secondary outcomes for the study included evaluating the association between medication use or non-use and each individual component of the composite primary outcome. These included first-time occurrences of the nonfatal endpoints of atrial fibrillation or flutter, ischemic (but not hemorrhagic) stroke, heart failure, and myocardial infarction. Cardiac death was death from any cardiac cause.

“Supporting use of a combined endpoint, event rates consistently increased for all individual outcomes” for diclofenac initiators compared with those who did not start an NSAID, wrote Dr. Schmidt and his colleagues.

Individuals were excluded if they had known cardiovascular, kidney, liver, or ulcer disease, and if they had malignancy or serious mental health diagnoses such as dementia or schizophrenia. Participants, aged a mean 48-56 years, had to be at least 18 years of age and could not have filled a prescription for an NSAID within the previous 12 months. Men made up 36.6%-46.3% of the cohorts.

Dr. Schmidt, of Aarhus (Denmark) University, and his collaborators said that in comparison with other NSAIDs, the short half-life of diclofenac means that a supratherapeutic plasma concentration of diclofenac soon after initiation achieves not just cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), but also COX-1 inhibition. However, after those high levels fall, patients taking diclofenac spend a substantial period of time with unopposed COX-2 inhibition, a state that is known to be prothrombotic, and also associated with blood pressure elevation, atherogenesis, and worsening of heart failure.

Diclofenac and ibuprofen had similar gastrointestinal bleeding risks, and both medications were associated with a higher risk of bleeding than were ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or no medication.

“Comparing diclofenac initiation with no NSAID initiation, the consistency between our results and those of previous meta-analyses of both trial and observational data provides strong evidence to guide clinical decision making,” said Dr. Schmidt and his coauthors.

“Considering its cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risks, however, there is little justification to initiate diclofenac treatment before other traditional NSAIDs,” noted the investigators. “It is time to acknowledge the potential health risk of diclofenac and to reduce its use.”

The study was funded by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology Research Foundation, University of Aarhus, and by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Danish Research Council. The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schmidt M et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3426

FROM BMJ

Key clinical point: Those starting diclofenac had increased risk for cardiovascular events or cardiac death.

Major finding: Risk for major adverse cardiovascular events was increased by 50% compared with noninitiators.

Study details: Retrospective propensity-matched cohort study using national databases and registries.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Department of Clinical Epidemiology Research Foundation of the University of Aarhus, Denmark, and by the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, funded by the Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the Danish Research Council. The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Schmidt M et al. BMJ 2018;362:k3426.

Pot use and addiction; Steve Jobs's daughter on her father

As cannabis continues to be legalized across many states, the reality that some users are addicts is receiving greater notice. The prospect of easier and legal availability has sparked (pun intended) public health concerns. “Cannabis is potentially a real public health problem,” says Mark A.R. Kleiman, PhD, a professor of public policy at New York University.

“It wasn’t obvious to me 25 years ago, when 9% of self-reported cannabis users over the last month reported daily or near-daily use. I always was prepared to say, ‘No, it’s not a very abusable drug. Nine percent of anybody will do something stupid.’ But that number is now [something like] 40%” (The Atlantic).

It’s no secret that Steve Jobs was a driven person who could be aloof and cruel to business associates. Now, with the publication of a memoir by his daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs, his cold path through life is revealed to have extended to the four walls of the family home. In the memoir “Small Fry,” Ms. Brennan-Jobs paints a picture of a father who, after accepting court-ordered child support, was emotionally hurtful.

Ms. Brennan-Jobs claims that he told her that she “smelled like a toilet,” when she visited Mr. Jobs on his deathbed. The remark was based on fact, as she later acknowledged (The New York Times).

A romantic relationship that stands the test of time is not a static union. There is give and take, communication, good and not-so good times, and adjustment to the changes that life brings.

But when one partner is physically present but mentally absent, the load can be crushing. Spouses of someone with Alzheimer’s disease or another progressive disorder that robs a person of their mental acuity and personality know this hell.

Less well-known, but just as devastating, is the state of “minimal consciousness” – where someone with a brain injury is left immobile and incapable of independent self-care, but who still may perceive the world and, in their own way, respond to the world and those in it.

A recent article explores the relationship of car crash victim Ian Jordon and his wife, Hilary. This past April marked the couple’s 45th wedding anniversary. For more than 30 of those years, Ian has been bedridden and unresponsive after a September 1987 car accident at the end of a shift as a police officer. He was 35 years old (Globe and Mail).

The U.S. Department of Education has announced that it is exploring the possibility that legislation governing academic enrichment grants might permit the use of the funds to purchase guns for schools.

The move has been greeted with hostility from Democrats and many educators, who decry the diversion of funds that are typically used for after school programs mental health support to a program that, they say, is fueled by the desire to appease the National Rifle Association (PBS News Hour).

As cannabis continues to be legalized across many states, the reality that some users are addicts is receiving greater notice. The prospect of easier and legal availability has sparked (pun intended) public health concerns. “Cannabis is potentially a real public health problem,” says Mark A.R. Kleiman, PhD, a professor of public policy at New York University.

“It wasn’t obvious to me 25 years ago, when 9% of self-reported cannabis users over the last month reported daily or near-daily use. I always was prepared to say, ‘No, it’s not a very abusable drug. Nine percent of anybody will do something stupid.’ But that number is now [something like] 40%” (The Atlantic).

It’s no secret that Steve Jobs was a driven person who could be aloof and cruel to business associates. Now, with the publication of a memoir by his daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs, his cold path through life is revealed to have extended to the four walls of the family home. In the memoir “Small Fry,” Ms. Brennan-Jobs paints a picture of a father who, after accepting court-ordered child support, was emotionally hurtful.

Ms. Brennan-Jobs claims that he told her that she “smelled like a toilet,” when she visited Mr. Jobs on his deathbed. The remark was based on fact, as she later acknowledged (The New York Times).

A romantic relationship that stands the test of time is not a static union. There is give and take, communication, good and not-so good times, and adjustment to the changes that life brings.

But when one partner is physically present but mentally absent, the load can be crushing. Spouses of someone with Alzheimer’s disease or another progressive disorder that robs a person of their mental acuity and personality know this hell.

Less well-known, but just as devastating, is the state of “minimal consciousness” – where someone with a brain injury is left immobile and incapable of independent self-care, but who still may perceive the world and, in their own way, respond to the world and those in it.

A recent article explores the relationship of car crash victim Ian Jordon and his wife, Hilary. This past April marked the couple’s 45th wedding anniversary. For more than 30 of those years, Ian has been bedridden and unresponsive after a September 1987 car accident at the end of a shift as a police officer. He was 35 years old (Globe and Mail).

The U.S. Department of Education has announced that it is exploring the possibility that legislation governing academic enrichment grants might permit the use of the funds to purchase guns for schools.

The move has been greeted with hostility from Democrats and many educators, who decry the diversion of funds that are typically used for after school programs mental health support to a program that, they say, is fueled by the desire to appease the National Rifle Association (PBS News Hour).

As cannabis continues to be legalized across many states, the reality that some users are addicts is receiving greater notice. The prospect of easier and legal availability has sparked (pun intended) public health concerns. “Cannabis is potentially a real public health problem,” says Mark A.R. Kleiman, PhD, a professor of public policy at New York University.

“It wasn’t obvious to me 25 years ago, when 9% of self-reported cannabis users over the last month reported daily or near-daily use. I always was prepared to say, ‘No, it’s not a very abusable drug. Nine percent of anybody will do something stupid.’ But that number is now [something like] 40%” (The Atlantic).

It’s no secret that Steve Jobs was a driven person who could be aloof and cruel to business associates. Now, with the publication of a memoir by his daughter, Lisa Brennan-Jobs, his cold path through life is revealed to have extended to the four walls of the family home. In the memoir “Small Fry,” Ms. Brennan-Jobs paints a picture of a father who, after accepting court-ordered child support, was emotionally hurtful.

Ms. Brennan-Jobs claims that he told her that she “smelled like a toilet,” when she visited Mr. Jobs on his deathbed. The remark was based on fact, as she later acknowledged (The New York Times).

A romantic relationship that stands the test of time is not a static union. There is give and take, communication, good and not-so good times, and adjustment to the changes that life brings.

But when one partner is physically present but mentally absent, the load can be crushing. Spouses of someone with Alzheimer’s disease or another progressive disorder that robs a person of their mental acuity and personality know this hell.

Less well-known, but just as devastating, is the state of “minimal consciousness” – where someone with a brain injury is left immobile and incapable of independent self-care, but who still may perceive the world and, in their own way, respond to the world and those in it.

A recent article explores the relationship of car crash victim Ian Jordon and his wife, Hilary. This past April marked the couple’s 45th wedding anniversary. For more than 30 of those years, Ian has been bedridden and unresponsive after a September 1987 car accident at the end of a shift as a police officer. He was 35 years old (Globe and Mail).

The U.S. Department of Education has announced that it is exploring the possibility that legislation governing academic enrichment grants might permit the use of the funds to purchase guns for schools.

The move has been greeted with hostility from Democrats and many educators, who decry the diversion of funds that are typically used for after school programs mental health support to a program that, they say, is fueled by the desire to appease the National Rifle Association (PBS News Hour).

United Kingdom experience provides important lessons for controlling C. auris outbreaks

ATLANTA – The persistence and transmission of Candida auris in health care settings appears to be dependent on environmental survival, underscoring the need for careful investigation of the environment – and, in particular, multiuse patient equipment.

That’s the key lesson from one of the largest outbreaks of the emerging, multidrug-resistant pathogen to date, David Eyre, DPhil, said at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Our experience at Oxford began with a Public Health England alert, which closely followed a similar alert from the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] in the summer of 2016,” Dr. Eyre of the University of Oxford (England) said during an update on the epidemiology of the outbreak and the successful, multipronged effort to control it.

The outbreak, which occurred in the neurosciences intensive care unit of Oxford University Hospitals beginning in early 2015, was detected in 2016 when a cluster of C. auris infections was identified and traced to the unit. An intensive patient and environmental screening program was established, isolation protocols were used for patients who tested positive, enhanced cleaning processes were initiated, and equipment was removed and replaced with single-use equipment when possible.

“We also worked quite closely with our staff to raise awareness,” he said, adding that colonized patients who were undergoing a surgical procedure received single-dose antifungal prophylaxis prior to the procedure.

A case-control study was conducted, and after the researchers used multivariate logistic regression to control for length of stay, patient physiology, and biomarkers, exposure to multiuse skin surface axillary temperature monitoring was shown to be one of the strongest independent predictors of C. auris colonization and infection (odds ratio 6.80), he said, adding that antifungal exposure was also a significant risk factor, but only 5% of patients had received antifungals.

The axillary probes were then removed from the environment. As of April 2017 (when the probes were removed), 66 patients had been colonized or infected, and an additional 10 cases occurred after the probes were removed, with the last case occurring in November 2017.

Seven of the 76 cases involved invasive infection, and 1 patient died several months after hospital discharge, Dr. Eyre said.

The patient screening processes allowed for estimation of colonization time (approximately 2 months), and also allowed for whole-genome sequencing of 79 samples from 43 patients, 6 environmental isolates, and 2 isolates from regional surveillance, Dr. Eyre said.

All outbreak sequences formed a single genetic cluster within the C. auris South African clade, and were found to have been introduced to Oxford around 2012 or 2013, with about six mutations per year, or “roughly 12 million base pairs in total,” he said, adding that both patients and temperature probes were colonized with multiple strains, and there was “close mixing” between the two.

This pattern changed following removal of the temperature probes, but it took some time.

“However, from November [2017] onward – so that’s now 291 days ... we’ve not had another new patient isolate, and that’s not only no invasive infection, but also no colonization despite continuing the screening program,” he said.

According to the CDC, C. auris is “an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat” because of its often multidrug-resistant nature, difficulty identifying the pathogen using standard laboratory methods, and the risk for misidentification in labs without specific technology, which could lead to inappropriate management.

“It has caused outbreaks in health care settings. For this reason, it is important to quickly identify C. auris in a hospitalized patient so that health care facilities can take special precautions to stop its spread,” a CDC page on C. auris states. “CDC encourages all U.S. laboratory staff who identify C. auris to notify their state or local public health authorities and CDC at candidaauris@cdc.gov.”

Dr. Eyre reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Eyre D et al. ICEID 2018 Oral Abstract Presentation.

ATLANTA – The persistence and transmission of Candida auris in health care settings appears to be dependent on environmental survival, underscoring the need for careful investigation of the environment – and, in particular, multiuse patient equipment.

That’s the key lesson from one of the largest outbreaks of the emerging, multidrug-resistant pathogen to date, David Eyre, DPhil, said at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Our experience at Oxford began with a Public Health England alert, which closely followed a similar alert from the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] in the summer of 2016,” Dr. Eyre of the University of Oxford (England) said during an update on the epidemiology of the outbreak and the successful, multipronged effort to control it.

The outbreak, which occurred in the neurosciences intensive care unit of Oxford University Hospitals beginning in early 2015, was detected in 2016 when a cluster of C. auris infections was identified and traced to the unit. An intensive patient and environmental screening program was established, isolation protocols were used for patients who tested positive, enhanced cleaning processes were initiated, and equipment was removed and replaced with single-use equipment when possible.

“We also worked quite closely with our staff to raise awareness,” he said, adding that colonized patients who were undergoing a surgical procedure received single-dose antifungal prophylaxis prior to the procedure.

A case-control study was conducted, and after the researchers used multivariate logistic regression to control for length of stay, patient physiology, and biomarkers, exposure to multiuse skin surface axillary temperature monitoring was shown to be one of the strongest independent predictors of C. auris colonization and infection (odds ratio 6.80), he said, adding that antifungal exposure was also a significant risk factor, but only 5% of patients had received antifungals.

The axillary probes were then removed from the environment. As of April 2017 (when the probes were removed), 66 patients had been colonized or infected, and an additional 10 cases occurred after the probes were removed, with the last case occurring in November 2017.

Seven of the 76 cases involved invasive infection, and 1 patient died several months after hospital discharge, Dr. Eyre said.

The patient screening processes allowed for estimation of colonization time (approximately 2 months), and also allowed for whole-genome sequencing of 79 samples from 43 patients, 6 environmental isolates, and 2 isolates from regional surveillance, Dr. Eyre said.

All outbreak sequences formed a single genetic cluster within the C. auris South African clade, and were found to have been introduced to Oxford around 2012 or 2013, with about six mutations per year, or “roughly 12 million base pairs in total,” he said, adding that both patients and temperature probes were colonized with multiple strains, and there was “close mixing” between the two.

This pattern changed following removal of the temperature probes, but it took some time.

“However, from November [2017] onward – so that’s now 291 days ... we’ve not had another new patient isolate, and that’s not only no invasive infection, but also no colonization despite continuing the screening program,” he said.

According to the CDC, C. auris is “an emerging fungus that presents a serious global health threat” because of its often multidrug-resistant nature, difficulty identifying the pathogen using standard laboratory methods, and the risk for misidentification in labs without specific technology, which could lead to inappropriate management.

“It has caused outbreaks in health care settings. For this reason, it is important to quickly identify C. auris in a hospitalized patient so that health care facilities can take special precautions to stop its spread,” a CDC page on C. auris states. “CDC encourages all U.S. laboratory staff who identify C. auris to notify their state or local public health authorities and CDC at candidaauris@cdc.gov.”

Dr. Eyre reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Eyre D et al. ICEID 2018 Oral Abstract Presentation.

ATLANTA – The persistence and transmission of Candida auris in health care settings appears to be dependent on environmental survival, underscoring the need for careful investigation of the environment – and, in particular, multiuse patient equipment.

That’s the key lesson from one of the largest outbreaks of the emerging, multidrug-resistant pathogen to date, David Eyre, DPhil, said at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Our experience at Oxford began with a Public Health England alert, which closely followed a similar alert from the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] in the summer of 2016,” Dr. Eyre of the University of Oxford (England) said during an update on the epidemiology of the outbreak and the successful, multipronged effort to control it.

The outbreak, which occurred in the neurosciences intensive care unit of Oxford University Hospitals beginning in early 2015, was detected in 2016 when a cluster of C. auris infections was identified and traced to the unit. An intensive patient and environmental screening program was established, isolation protocols were used for patients who tested positive, enhanced cleaning processes were initiated, and equipment was removed and replaced with single-use equipment when possible.

“We also worked quite closely with our staff to raise awareness,” he said, adding that colonized patients who were undergoing a surgical procedure received single-dose antifungal prophylaxis prior to the procedure.

A case-control study was conducted, and after the researchers used multivariate logistic regression to control for length of stay, patient physiology, and biomarkers, exposure to multiuse skin surface axillary temperature monitoring was shown to be one of the strongest independent predictors of C. auris colonization and infection (odds ratio 6.80), he said, adding that antifungal exposure was also a significant risk factor, but only 5% of patients had received antifungals.

The axillary probes were then removed from the environment. As of April 2017 (when the probes were removed), 66 patients had been colonized or infected, and an additional 10 cases occurred after the probes were removed, with the last case occurring in November 2017.

Seven of the 76 cases involved invasive infection, and 1 patient died several months after hospital discharge, Dr. Eyre said.

The patient screening processes allowed for estimation of colonization time (approximately 2 months), and also allowed for whole-genome sequencing of 79 samples from 43 patients, 6 environmental isolates, and 2 isolates from regional surveillance, Dr. Eyre said.