User login

Is cancer immunotherapy more effective in men than women?

Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint inhibitors may achieve greater mortality reductions in men than they do in women, new research has suggested.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review published in Lancet Oncology, researchers analyzed 20 randomized, controlled trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors that included detail on overall survival and patients’ sex; altogether, these studies involved 11,351 patients with advanced or metastatic cancers.

They found that while men treated with checkpoint inhibitors had a significant 28% reduced risk of death, compared with male controls, the survival benefit in women was smaller (14% reduced risk of death, compared with female controls).

Fabio Conforti, MD, from the European Institute of Oncology, Milan, and coauthors commented that the magnitude of the difference between the effect seen men and that in women was clinically significant.

“The pooled reduction of risk of death was double the size for male patients than for female patients – a difference that is similar to the size of the difference in survival benefit observed between patients with non–small cell lung cancer with PD-L1 positive (greater than 1%) tumors versus negative tumors, who were treated with anti-PD-1,” they wrote.

This difference between the benefit seen men and that in women was evident across all the subgroups in the study, which included subgroups based on cancer histotype, line of treatment, drugs used, and type of control.

However there was greater heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect of checkpoint inhibitors on mortality in men than there was in women. The authors suggested this could be explained by the fact that the drugs have lower efficacy in women and this may therefore reduce the variability of results when compared with those in men.

The authors also looked at whether the studies that compared immunotherapies with nonimmunological therapies might show a different effect, but they still found a significantly higher benefit in men, compared with women.

The overall study population was two-thirds male and one-third female. The checkpoint inhibitors used were ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab, and the trials were conducted in patients with melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial tumors, gastric tumors, and mesothelioma.

Men have almost double the risk of mortality from cancer than do women, the authors said, with the greatest differences seen in melanoma, lung cancer, larynx cancer, esophagus cancer, and bladder cancer.

“This male-biased mortality is hypothesized to reflect differences not only in behavioral and biological factors, including causes of cancer and hormonal regulation, but also in the immune system.”

Despite this, sex is rarely taken into account when new therapeutic approaches are tested, the authors said.

They also commented on the fact that there was a relatively low number of women included in each trial, an issue that was recognized as far back as the 1990s as a major problem in medical trials.

“Our results further highlight this problem, showing clinically relevant differences in the efficacy of two important classes of immunological drugs, namely anti–CTLA-4 and anti–PD-1 antibodies, when compared with controls in male and female patients with advanced solid tumors,” they wrote.

They noted that they couldn’t exclude the possibility that the effect may be the result of other variables that were distributed differently between the sexes. However, they also qualified this by saying that variables known to affect the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as PD-L1 expression and mutation status, were not likely to explain the results.

Given their findings, the authors said a patient’s sex should be taken into account when weighing the risks and benefits of checkpoint inhibitors given the magnitude of benefit was sex-dependent. They also called for future immunotherapy studies to include more women.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Conforti F et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 May 16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4.

While cancer immunotherapy represents one of the most significant clinical advances in cancer treatment in the past decade, the basic but important clinical question about different effects between men and woman has not been addressed until now. The authors of this study are to be congratulated on such a comprehensive and well-conducted analysis, but the data does not completely support their final conclusion that checkpoint inhibitors benefit men more than women.

There are a large number of baseline characteristics of solid tumors that might differ between men and women and that have also been reported to impact the outcomes of patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors. Some of these may be lifestyle or behavioral characteristics – such as different smoking habits between men and women with non–small cell lung cancer – or differences in the distribution of oncogenic driver mutations between men and women.

We should therefore be cautious in jumping to conclusions and changing the current standard of care with respect to checkpoint inhibitors. In particular, we should not be denying treatment to women who are otherwise indicated for checkpoint inhibitors, based on these findings.

Omar Abdel-Rahman, MD, is from the clinical oncology department of the faculty of medicine at Ain Shams University in Cairo and from the Tom Baker Cancer Centre in Calgary. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018 May 16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[18]30270-5.) No conflicts of interest were declared.

While cancer immunotherapy represents one of the most significant clinical advances in cancer treatment in the past decade, the basic but important clinical question about different effects between men and woman has not been addressed until now. The authors of this study are to be congratulated on such a comprehensive and well-conducted analysis, but the data does not completely support their final conclusion that checkpoint inhibitors benefit men more than women.

There are a large number of baseline characteristics of solid tumors that might differ between men and women and that have also been reported to impact the outcomes of patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors. Some of these may be lifestyle or behavioral characteristics – such as different smoking habits between men and women with non–small cell lung cancer – or differences in the distribution of oncogenic driver mutations between men and women.

We should therefore be cautious in jumping to conclusions and changing the current standard of care with respect to checkpoint inhibitors. In particular, we should not be denying treatment to women who are otherwise indicated for checkpoint inhibitors, based on these findings.

Omar Abdel-Rahman, MD, is from the clinical oncology department of the faculty of medicine at Ain Shams University in Cairo and from the Tom Baker Cancer Centre in Calgary. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018 May 16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[18]30270-5.) No conflicts of interest were declared.

While cancer immunotherapy represents one of the most significant clinical advances in cancer treatment in the past decade, the basic but important clinical question about different effects between men and woman has not been addressed until now. The authors of this study are to be congratulated on such a comprehensive and well-conducted analysis, but the data does not completely support their final conclusion that checkpoint inhibitors benefit men more than women.

There are a large number of baseline characteristics of solid tumors that might differ between men and women and that have also been reported to impact the outcomes of patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors. Some of these may be lifestyle or behavioral characteristics – such as different smoking habits between men and women with non–small cell lung cancer – or differences in the distribution of oncogenic driver mutations between men and women.

We should therefore be cautious in jumping to conclusions and changing the current standard of care with respect to checkpoint inhibitors. In particular, we should not be denying treatment to women who are otherwise indicated for checkpoint inhibitors, based on these findings.

Omar Abdel-Rahman, MD, is from the clinical oncology department of the faculty of medicine at Ain Shams University in Cairo and from the Tom Baker Cancer Centre in Calgary. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Oncol. 2018 May 16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[18]30270-5.) No conflicts of interest were declared.

Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint inhibitors may achieve greater mortality reductions in men than they do in women, new research has suggested.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review published in Lancet Oncology, researchers analyzed 20 randomized, controlled trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors that included detail on overall survival and patients’ sex; altogether, these studies involved 11,351 patients with advanced or metastatic cancers.

They found that while men treated with checkpoint inhibitors had a significant 28% reduced risk of death, compared with male controls, the survival benefit in women was smaller (14% reduced risk of death, compared with female controls).

Fabio Conforti, MD, from the European Institute of Oncology, Milan, and coauthors commented that the magnitude of the difference between the effect seen men and that in women was clinically significant.

“The pooled reduction of risk of death was double the size for male patients than for female patients – a difference that is similar to the size of the difference in survival benefit observed between patients with non–small cell lung cancer with PD-L1 positive (greater than 1%) tumors versus negative tumors, who were treated with anti-PD-1,” they wrote.

This difference between the benefit seen men and that in women was evident across all the subgroups in the study, which included subgroups based on cancer histotype, line of treatment, drugs used, and type of control.

However there was greater heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect of checkpoint inhibitors on mortality in men than there was in women. The authors suggested this could be explained by the fact that the drugs have lower efficacy in women and this may therefore reduce the variability of results when compared with those in men.

The authors also looked at whether the studies that compared immunotherapies with nonimmunological therapies might show a different effect, but they still found a significantly higher benefit in men, compared with women.

The overall study population was two-thirds male and one-third female. The checkpoint inhibitors used were ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab, and the trials were conducted in patients with melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial tumors, gastric tumors, and mesothelioma.

Men have almost double the risk of mortality from cancer than do women, the authors said, with the greatest differences seen in melanoma, lung cancer, larynx cancer, esophagus cancer, and bladder cancer.

“This male-biased mortality is hypothesized to reflect differences not only in behavioral and biological factors, including causes of cancer and hormonal regulation, but also in the immune system.”

Despite this, sex is rarely taken into account when new therapeutic approaches are tested, the authors said.

They also commented on the fact that there was a relatively low number of women included in each trial, an issue that was recognized as far back as the 1990s as a major problem in medical trials.

“Our results further highlight this problem, showing clinically relevant differences in the efficacy of two important classes of immunological drugs, namely anti–CTLA-4 and anti–PD-1 antibodies, when compared with controls in male and female patients with advanced solid tumors,” they wrote.

They noted that they couldn’t exclude the possibility that the effect may be the result of other variables that were distributed differently between the sexes. However, they also qualified this by saying that variables known to affect the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as PD-L1 expression and mutation status, were not likely to explain the results.

Given their findings, the authors said a patient’s sex should be taken into account when weighing the risks and benefits of checkpoint inhibitors given the magnitude of benefit was sex-dependent. They also called for future immunotherapy studies to include more women.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Conforti F et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 May 16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4.

Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint inhibitors may achieve greater mortality reductions in men than they do in women, new research has suggested.

In a meta-analysis and systematic review published in Lancet Oncology, researchers analyzed 20 randomized, controlled trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors that included detail on overall survival and patients’ sex; altogether, these studies involved 11,351 patients with advanced or metastatic cancers.

They found that while men treated with checkpoint inhibitors had a significant 28% reduced risk of death, compared with male controls, the survival benefit in women was smaller (14% reduced risk of death, compared with female controls).

Fabio Conforti, MD, from the European Institute of Oncology, Milan, and coauthors commented that the magnitude of the difference between the effect seen men and that in women was clinically significant.

“The pooled reduction of risk of death was double the size for male patients than for female patients – a difference that is similar to the size of the difference in survival benefit observed between patients with non–small cell lung cancer with PD-L1 positive (greater than 1%) tumors versus negative tumors, who were treated with anti-PD-1,” they wrote.

This difference between the benefit seen men and that in women was evident across all the subgroups in the study, which included subgroups based on cancer histotype, line of treatment, drugs used, and type of control.

However there was greater heterogeneity in the magnitude of the effect of checkpoint inhibitors on mortality in men than there was in women. The authors suggested this could be explained by the fact that the drugs have lower efficacy in women and this may therefore reduce the variability of results when compared with those in men.

The authors also looked at whether the studies that compared immunotherapies with nonimmunological therapies might show a different effect, but they still found a significantly higher benefit in men, compared with women.

The overall study population was two-thirds male and one-third female. The checkpoint inhibitors used were ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab, and the trials were conducted in patients with melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial tumors, gastric tumors, and mesothelioma.

Men have almost double the risk of mortality from cancer than do women, the authors said, with the greatest differences seen in melanoma, lung cancer, larynx cancer, esophagus cancer, and bladder cancer.

“This male-biased mortality is hypothesized to reflect differences not only in behavioral and biological factors, including causes of cancer and hormonal regulation, but also in the immune system.”

Despite this, sex is rarely taken into account when new therapeutic approaches are tested, the authors said.

They also commented on the fact that there was a relatively low number of women included in each trial, an issue that was recognized as far back as the 1990s as a major problem in medical trials.

“Our results further highlight this problem, showing clinically relevant differences in the efficacy of two important classes of immunological drugs, namely anti–CTLA-4 and anti–PD-1 antibodies, when compared with controls in male and female patients with advanced solid tumors,” they wrote.

They noted that they couldn’t exclude the possibility that the effect may be the result of other variables that were distributed differently between the sexes. However, they also qualified this by saying that variables known to affect the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as PD-L1 expression and mutation status, were not likely to explain the results.

Given their findings, the authors said a patient’s sex should be taken into account when weighing the risks and benefits of checkpoint inhibitors given the magnitude of benefit was sex-dependent. They also called for future immunotherapy studies to include more women.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Conforti F et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 May 16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4.

FROM LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Checkpoint inhibitors are linked with greater mortality reductions in men than in women.

Major finding: Checkpoint inhibitors are associated with a 28% reduction in cancer mortality in men and 14% in women.

Study details: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 randomized, controlled trials involving 11,351 patients.

Disclosures: No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Conforti F et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 May 16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4.

As-needed budesonide-formoterol prevented exacerbations in mild asthma

according to the results of two large, double-blind, 52-week, randomized phase 3 trials.

In the SYGMA1 (Symbicort Given as Needed in Mild Asthma) trial, the regimen outperformed as-needed terbutaline in terms of asthma control (34.4% vs. 31.1% of weeks; P = .046) and exacerbations (rate ratio, 0.36; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.49). In the SYGMA2 study, it was noninferior to twice-daily budesonide for preventing severe exacerbations (RR, 0.97; upper one-sided 95% CI, 1.16). The findings were published in two reports in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Accordingly, they randomly assigned 3,849 patients aged 12 years and up who had mild persistent asthma (mean forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] before bronchodilator use, 84% of predicted value) to receive one of three regimens: twice-daily placebo plus terbutaline (0.5 mg) used as needed, twice-daily placebo plus budesonide-formoterol (200 mcg of budesonide and 6 mcg of formoterol) used as needed, or maintenance twice-daily budesonide (200 mcg) plus as-needed terbutaline (0.5 mg), all for 52 weeks.

In the final analysis of 3,836 patients, annual rates of severe exacerbations were 0.20 with terbutaline, significantly worse than with budesonide-formoterol (0.07) or maintenance budesonide (0.09). Using budesonide-formoterol (Symbicort) as needed improved the odds of having well-controlled asthma by about 14%, when compared with using terbutaline as needed (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.00-1.30; P = .046).

Although maintenance budesonide controlled asthma best (44.4% of weeks; OR vs. budesonide-formoterol, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73), 21% of patients did not adhere to it, the researchers reported. “Patients are often more concerned [than their health care providers] about adverse effects of inhaled glucocorticoids, even when low inhaled doses are used,” they wrote. Notably, the budesonide-formoterol as-needed group received a median daily dose of only 57 mcg inhaled glucocorticoid, 17% of that received by the budesonide maintenance group.

In SYGMA2 (NCT02224157), 4,215 patients with mild persistent asthma aged 12 years and up were randomly assigned to receive either twice-daily placebo plus as-needed budesonide-formoterol or twice-daily maintenance budesonide plus as-needed terbutaline. Doses were the same as in the SYGMA1 trial. The regimens resembled each other in terms of severe exacerbations (annualized rates, 0.11 and 0.12, respectively) and time to first exacerbation, even though budesonide-formoterol patients received a 75% lower median daily dose of inhaled glucocorticoid, reported Eric D. Bateman, MD, of the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and his associates.

Results from both trials suggested that as-needed budesonide-formoterol provided better symptom control than did terbutaline but worse symptom control than did twice-daily budesonide. In SYGMA1, the change from baseline on the Asthma Control Questionnaire-5 (ACQ-5) favored budesonide-formoterol over terbutaline by an average of 0.15 units and similarly favored twice-daily budesonide over budesonide-formoterol. In SYGMA2, the budesonide maintenance group averaged 0.11 units greater improvement on the ACQ-5 and 0.10 better improvement on the standardized Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, compared with as-needed budesonide-formoterol recipients.

Finally, lung function assessments favored as-needed budesonide-formoterol over terbutaline but not over maintenance budesonide. SYGMA1, mean changes (from baseline) in FEV1 before bronchodilator use were 11.2 mL with terbutaline, 65.0 mL with budesonide-formoterol, and 119.3 mL with maintenance budesonide. In SYGMA2, these values were 104 mL with budesonide-formoterol and 136.6 mL with maintenance budesonide.

AstraZeneca provided funding. For SYGMA1, Dr. Byrne disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, and Genentech. For SYGMA2, Dr. Bateman disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Novartis, Cipla, Vectura, Boehringer Ingelheim, and a number of other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCES: O’Byrne PM et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1865-76.Bateman ED et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1877-87.

In the SYGMA1 and SYGMA2 trials, as-needed budesonide-formoterol (Symbicort) prevented exacerbations and loss of lung function, the two worst outcomes of poorly controlled asthma, concluded Stephen C. Lazarus, MD, in an editorial accompanying the studies in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“As-needed treatment was similar, or at least noninferior, to regular maintenance therapy with inhaled glucocorticoids with regard to the prevention of exacerbations, and exacerbations are the main contributor to loss of lung function, death, and cost,” wrote Dr. Lazarus.

Patients typically received only 17%-25% as much inhaled glucocorticoid as did those on maintenance budesonide, which would help prevent side effects and would make the regimen more acceptable to “glucocorticoid-averse patients,” he added. Another benefit to patients with mild persistent asthma using as-needed budesonide-formoterol instead of inhaled glucocorticoid maintenance therapy is that it would result in nearly $1 billion in cost savings in the United States yearly.

Budesonide-formoterol did not control symptoms as well as did maintenance budesonide, but patients might accept “occasional mild symptoms and inhaler use if it [freed] them from daily use of inhaled glucocorticoids while preventing loss of lung function and exacerbations,” he concluded. “For these patients, ‘Two out of three ain’t bad!’ ”

Dr. Lazarus is in the department of medicine and at the Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California, San Francisco. He reported having no conflicts of interest. This comments are from his editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1802680).

In the SYGMA1 and SYGMA2 trials, as-needed budesonide-formoterol (Symbicort) prevented exacerbations and loss of lung function, the two worst outcomes of poorly controlled asthma, concluded Stephen C. Lazarus, MD, in an editorial accompanying the studies in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“As-needed treatment was similar, or at least noninferior, to regular maintenance therapy with inhaled glucocorticoids with regard to the prevention of exacerbations, and exacerbations are the main contributor to loss of lung function, death, and cost,” wrote Dr. Lazarus.

Patients typically received only 17%-25% as much inhaled glucocorticoid as did those on maintenance budesonide, which would help prevent side effects and would make the regimen more acceptable to “glucocorticoid-averse patients,” he added. Another benefit to patients with mild persistent asthma using as-needed budesonide-formoterol instead of inhaled glucocorticoid maintenance therapy is that it would result in nearly $1 billion in cost savings in the United States yearly.

Budesonide-formoterol did not control symptoms as well as did maintenance budesonide, but patients might accept “occasional mild symptoms and inhaler use if it [freed] them from daily use of inhaled glucocorticoids while preventing loss of lung function and exacerbations,” he concluded. “For these patients, ‘Two out of three ain’t bad!’ ”

Dr. Lazarus is in the department of medicine and at the Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California, San Francisco. He reported having no conflicts of interest. This comments are from his editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1802680).

In the SYGMA1 and SYGMA2 trials, as-needed budesonide-formoterol (Symbicort) prevented exacerbations and loss of lung function, the two worst outcomes of poorly controlled asthma, concluded Stephen C. Lazarus, MD, in an editorial accompanying the studies in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“As-needed treatment was similar, or at least noninferior, to regular maintenance therapy with inhaled glucocorticoids with regard to the prevention of exacerbations, and exacerbations are the main contributor to loss of lung function, death, and cost,” wrote Dr. Lazarus.

Patients typically received only 17%-25% as much inhaled glucocorticoid as did those on maintenance budesonide, which would help prevent side effects and would make the regimen more acceptable to “glucocorticoid-averse patients,” he added. Another benefit to patients with mild persistent asthma using as-needed budesonide-formoterol instead of inhaled glucocorticoid maintenance therapy is that it would result in nearly $1 billion in cost savings in the United States yearly.

Budesonide-formoterol did not control symptoms as well as did maintenance budesonide, but patients might accept “occasional mild symptoms and inhaler use if it [freed] them from daily use of inhaled glucocorticoids while preventing loss of lung function and exacerbations,” he concluded. “For these patients, ‘Two out of three ain’t bad!’ ”

Dr. Lazarus is in the department of medicine and at the Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California, San Francisco. He reported having no conflicts of interest. This comments are from his editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1802680).

according to the results of two large, double-blind, 52-week, randomized phase 3 trials.

In the SYGMA1 (Symbicort Given as Needed in Mild Asthma) trial, the regimen outperformed as-needed terbutaline in terms of asthma control (34.4% vs. 31.1% of weeks; P = .046) and exacerbations (rate ratio, 0.36; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.49). In the SYGMA2 study, it was noninferior to twice-daily budesonide for preventing severe exacerbations (RR, 0.97; upper one-sided 95% CI, 1.16). The findings were published in two reports in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Accordingly, they randomly assigned 3,849 patients aged 12 years and up who had mild persistent asthma (mean forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] before bronchodilator use, 84% of predicted value) to receive one of three regimens: twice-daily placebo plus terbutaline (0.5 mg) used as needed, twice-daily placebo plus budesonide-formoterol (200 mcg of budesonide and 6 mcg of formoterol) used as needed, or maintenance twice-daily budesonide (200 mcg) plus as-needed terbutaline (0.5 mg), all for 52 weeks.

In the final analysis of 3,836 patients, annual rates of severe exacerbations were 0.20 with terbutaline, significantly worse than with budesonide-formoterol (0.07) or maintenance budesonide (0.09). Using budesonide-formoterol (Symbicort) as needed improved the odds of having well-controlled asthma by about 14%, when compared with using terbutaline as needed (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.00-1.30; P = .046).

Although maintenance budesonide controlled asthma best (44.4% of weeks; OR vs. budesonide-formoterol, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73), 21% of patients did not adhere to it, the researchers reported. “Patients are often more concerned [than their health care providers] about adverse effects of inhaled glucocorticoids, even when low inhaled doses are used,” they wrote. Notably, the budesonide-formoterol as-needed group received a median daily dose of only 57 mcg inhaled glucocorticoid, 17% of that received by the budesonide maintenance group.

In SYGMA2 (NCT02224157), 4,215 patients with mild persistent asthma aged 12 years and up were randomly assigned to receive either twice-daily placebo plus as-needed budesonide-formoterol or twice-daily maintenance budesonide plus as-needed terbutaline. Doses were the same as in the SYGMA1 trial. The regimens resembled each other in terms of severe exacerbations (annualized rates, 0.11 and 0.12, respectively) and time to first exacerbation, even though budesonide-formoterol patients received a 75% lower median daily dose of inhaled glucocorticoid, reported Eric D. Bateman, MD, of the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and his associates.

Results from both trials suggested that as-needed budesonide-formoterol provided better symptom control than did terbutaline but worse symptom control than did twice-daily budesonide. In SYGMA1, the change from baseline on the Asthma Control Questionnaire-5 (ACQ-5) favored budesonide-formoterol over terbutaline by an average of 0.15 units and similarly favored twice-daily budesonide over budesonide-formoterol. In SYGMA2, the budesonide maintenance group averaged 0.11 units greater improvement on the ACQ-5 and 0.10 better improvement on the standardized Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, compared with as-needed budesonide-formoterol recipients.

Finally, lung function assessments favored as-needed budesonide-formoterol over terbutaline but not over maintenance budesonide. SYGMA1, mean changes (from baseline) in FEV1 before bronchodilator use were 11.2 mL with terbutaline, 65.0 mL with budesonide-formoterol, and 119.3 mL with maintenance budesonide. In SYGMA2, these values were 104 mL with budesonide-formoterol and 136.6 mL with maintenance budesonide.

AstraZeneca provided funding. For SYGMA1, Dr. Byrne disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, and Genentech. For SYGMA2, Dr. Bateman disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Novartis, Cipla, Vectura, Boehringer Ingelheim, and a number of other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCES: O’Byrne PM et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1865-76.Bateman ED et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1877-87.

according to the results of two large, double-blind, 52-week, randomized phase 3 trials.

In the SYGMA1 (Symbicort Given as Needed in Mild Asthma) trial, the regimen outperformed as-needed terbutaline in terms of asthma control (34.4% vs. 31.1% of weeks; P = .046) and exacerbations (rate ratio, 0.36; 95% confidence interval, 0.27-0.49). In the SYGMA2 study, it was noninferior to twice-daily budesonide for preventing severe exacerbations (RR, 0.97; upper one-sided 95% CI, 1.16). The findings were published in two reports in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Accordingly, they randomly assigned 3,849 patients aged 12 years and up who had mild persistent asthma (mean forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] before bronchodilator use, 84% of predicted value) to receive one of three regimens: twice-daily placebo plus terbutaline (0.5 mg) used as needed, twice-daily placebo plus budesonide-formoterol (200 mcg of budesonide and 6 mcg of formoterol) used as needed, or maintenance twice-daily budesonide (200 mcg) plus as-needed terbutaline (0.5 mg), all for 52 weeks.

In the final analysis of 3,836 patients, annual rates of severe exacerbations were 0.20 with terbutaline, significantly worse than with budesonide-formoterol (0.07) or maintenance budesonide (0.09). Using budesonide-formoterol (Symbicort) as needed improved the odds of having well-controlled asthma by about 14%, when compared with using terbutaline as needed (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.00-1.30; P = .046).

Although maintenance budesonide controlled asthma best (44.4% of weeks; OR vs. budesonide-formoterol, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.57-0.73), 21% of patients did not adhere to it, the researchers reported. “Patients are often more concerned [than their health care providers] about adverse effects of inhaled glucocorticoids, even when low inhaled doses are used,” they wrote. Notably, the budesonide-formoterol as-needed group received a median daily dose of only 57 mcg inhaled glucocorticoid, 17% of that received by the budesonide maintenance group.

In SYGMA2 (NCT02224157), 4,215 patients with mild persistent asthma aged 12 years and up were randomly assigned to receive either twice-daily placebo plus as-needed budesonide-formoterol or twice-daily maintenance budesonide plus as-needed terbutaline. Doses were the same as in the SYGMA1 trial. The regimens resembled each other in terms of severe exacerbations (annualized rates, 0.11 and 0.12, respectively) and time to first exacerbation, even though budesonide-formoterol patients received a 75% lower median daily dose of inhaled glucocorticoid, reported Eric D. Bateman, MD, of the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and his associates.

Results from both trials suggested that as-needed budesonide-formoterol provided better symptom control than did terbutaline but worse symptom control than did twice-daily budesonide. In SYGMA1, the change from baseline on the Asthma Control Questionnaire-5 (ACQ-5) favored budesonide-formoterol over terbutaline by an average of 0.15 units and similarly favored twice-daily budesonide over budesonide-formoterol. In SYGMA2, the budesonide maintenance group averaged 0.11 units greater improvement on the ACQ-5 and 0.10 better improvement on the standardized Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, compared with as-needed budesonide-formoterol recipients.

Finally, lung function assessments favored as-needed budesonide-formoterol over terbutaline but not over maintenance budesonide. SYGMA1, mean changes (from baseline) in FEV1 before bronchodilator use were 11.2 mL with terbutaline, 65.0 mL with budesonide-formoterol, and 119.3 mL with maintenance budesonide. In SYGMA2, these values were 104 mL with budesonide-formoterol and 136.6 mL with maintenance budesonide.

AstraZeneca provided funding. For SYGMA1, Dr. Byrne disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, and Genentech. For SYGMA2, Dr. Bateman disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Novartis, Cipla, Vectura, Boehringer Ingelheim, and a number of other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCES: O’Byrne PM et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1865-76.Bateman ED et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1877-87.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: As-needed budesonide-formoterol (Symbicort) prevented exacerbations in patients with mild persistent asthma.

Major finding: In the SYGMA1 trial, the regimen outperformed as-needed terbutaline for asthma control (34.4% vs. 31.1% of weeks; P = .046) and exacerbations (RR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.27-0.49). In SYGMA2, the regimen was noninferior to twice-daily budesonide for preventing severe exacerbations (RR, 0.97; upper one-sided 95% confidence limit, 1.16).

Study details: SYGMA1 and SYGMA2, randomized phase 3 trials of 8,012 patients aged 12 years and older with mild persistent asthma.

Disclosures: AstraZeneca provided funding. For SYGMA1, Dr. Byrne disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, and Genentech. For SYGMA2, Dr. Bateman disclosed ties to AstraZeneca, Novartis, Cipla, Vectura, Boehringer Ingelheim, and a number of other pharmaceutical companies.

Sources: O’Byrne PM et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17;378(20);1865-76. Bateman ED et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 17;378(20):1877-87.

Adding bortezomib does not improve MCL outcomes

Bortezomib added to an alternating chemoimmunotherapy regimen did not improve time to treatment failure in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), results of a phase 2 study have suggested.

Response rates and time to treatment failure were similar to what has been seen historically without the addition of bortezomib, according to study investigator Jorge E. Romaguera, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues.

The phase 2 study included 95 patients with newly diagnosed MCL treated with alternating cycles of bortezomib added to rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (BzR-hyperCVAD) and bortezomib added to rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine (BzR-MA).

Of 87 patients evaluable for response, alternating BzR-hyperCVAD/BzR-MA resulted in an overall response rate of 100% and a complete response rate of 82%, Dr. Romaguera and his colleagues reported in the journal Cancer. At a median follow-up of 44 months, median time to treatment failure was 55 months, and median overall survival had not yet been reached, according to the report.

Dr. Romaguera and his coauthors compared these results with those from a previous study of alternating R-hyperCVAD/R-MA, in which the median time to treatment failure was 56.4 months. “This suggests that the addition of bortezomib does not improve the outcome,” they wrote in the current report.

Although more follow-up is needed, the landscape of MCL treatment is changing quickly, they added. In particular, lenalidomide and ibrutinib, already approved for relapsed/refractory MCL, are now being evaluated as part of first-line MCL regimens. “These drugs will offer strategies of either consolidation or maintenance after induction and will hopefully help continue to improve the duration of the initial response and the overall outcome,” the researchers wrote.

In the current phase 2 study, the fact that 100% of patients achieved complete response suggested that relapses come from minimal residual disease, which “has clearly become a clinical factor for the outcomes of patients with MCL and will likely become the next endpoint,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures related to the study, which was supported by Takeda Oncology.

SOURCE: Romaguera JE et al. Cancer. 2018 May 3. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31361.

Bortezomib added to an alternating chemoimmunotherapy regimen did not improve time to treatment failure in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), results of a phase 2 study have suggested.

Response rates and time to treatment failure were similar to what has been seen historically without the addition of bortezomib, according to study investigator Jorge E. Romaguera, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues.

The phase 2 study included 95 patients with newly diagnosed MCL treated with alternating cycles of bortezomib added to rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (BzR-hyperCVAD) and bortezomib added to rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine (BzR-MA).

Of 87 patients evaluable for response, alternating BzR-hyperCVAD/BzR-MA resulted in an overall response rate of 100% and a complete response rate of 82%, Dr. Romaguera and his colleagues reported in the journal Cancer. At a median follow-up of 44 months, median time to treatment failure was 55 months, and median overall survival had not yet been reached, according to the report.

Dr. Romaguera and his coauthors compared these results with those from a previous study of alternating R-hyperCVAD/R-MA, in which the median time to treatment failure was 56.4 months. “This suggests that the addition of bortezomib does not improve the outcome,” they wrote in the current report.

Although more follow-up is needed, the landscape of MCL treatment is changing quickly, they added. In particular, lenalidomide and ibrutinib, already approved for relapsed/refractory MCL, are now being evaluated as part of first-line MCL regimens. “These drugs will offer strategies of either consolidation or maintenance after induction and will hopefully help continue to improve the duration of the initial response and the overall outcome,” the researchers wrote.

In the current phase 2 study, the fact that 100% of patients achieved complete response suggested that relapses come from minimal residual disease, which “has clearly become a clinical factor for the outcomes of patients with MCL and will likely become the next endpoint,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures related to the study, which was supported by Takeda Oncology.

SOURCE: Romaguera JE et al. Cancer. 2018 May 3. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31361.

Bortezomib added to an alternating chemoimmunotherapy regimen did not improve time to treatment failure in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), results of a phase 2 study have suggested.

Response rates and time to treatment failure were similar to what has been seen historically without the addition of bortezomib, according to study investigator Jorge E. Romaguera, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues.

The phase 2 study included 95 patients with newly diagnosed MCL treated with alternating cycles of bortezomib added to rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (BzR-hyperCVAD) and bortezomib added to rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine (BzR-MA).

Of 87 patients evaluable for response, alternating BzR-hyperCVAD/BzR-MA resulted in an overall response rate of 100% and a complete response rate of 82%, Dr. Romaguera and his colleagues reported in the journal Cancer. At a median follow-up of 44 months, median time to treatment failure was 55 months, and median overall survival had not yet been reached, according to the report.

Dr. Romaguera and his coauthors compared these results with those from a previous study of alternating R-hyperCVAD/R-MA, in which the median time to treatment failure was 56.4 months. “This suggests that the addition of bortezomib does not improve the outcome,” they wrote in the current report.

Although more follow-up is needed, the landscape of MCL treatment is changing quickly, they added. In particular, lenalidomide and ibrutinib, already approved for relapsed/refractory MCL, are now being evaluated as part of first-line MCL regimens. “These drugs will offer strategies of either consolidation or maintenance after induction and will hopefully help continue to improve the duration of the initial response and the overall outcome,” the researchers wrote.

In the current phase 2 study, the fact that 100% of patients achieved complete response suggested that relapses come from minimal residual disease, which “has clearly become a clinical factor for the outcomes of patients with MCL and will likely become the next endpoint,” they wrote.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures related to the study, which was supported by Takeda Oncology.

SOURCE: Romaguera JE et al. Cancer. 2018 May 3. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31361.

FROM CANCER

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Rates of overall and complete response were 100% and 82%, respectively, while time to treatment failure was 55 months.

Study details: A phase 2 trial that included 95 patients treated with alternating cycles of bortezomib added to rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (BzR-hyperCVAD) and bortezomib added to rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and high-dose cytarabine (BzR-MA).

Disclosures: The study was supported by Takeda Oncology. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures related to the study.

Source: Romaguera JE et al. Cancer. 2018 May 3. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31361

Understanding Pediatric Abdominal Migraine

Abdominal migraine is a common cause of chronic and recurrent abdominal pain in children, according to a recent review. It is characterized by paroxysms of moderate to severe abdominal pain that is midline, periumbilical, or diffuse in location and accompanied by other symptoms including headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, or pallor. Despite the presence of comprehensive diagnostic criteria, it continues to be an underdiagnosed entity. Key points include:

- The average age of diagnosis is 3 to 10 years with peak incidence at 7 years.

- Most of the patients have a personal or family history of migraine.

- Pathophysiology of the condition is believed to be similar to that of other functional gastrointestinal disorders and cephalic migraine; it is also well recognized as a type of pediatric migraine variant.

- A careful history, thorough physical examination, and use of well-defined, symptom-based guidelines are needed to make a diagnosis.

- Although it resolves completely in most of the patients, these patients have a strong propensity to develop migraine later in life.

- Nonpharmacologic treatment options, including avoidance of triggers, behavior therapy, and dietary modifications should be the initial line of management.

Pediatric abdominal migraine: current perspectives on a lesser known entity. [Published online ahead of print April 24, 2018]. Pediatric Health Med Ther. doi:10.2147%2FPHMT.S127210.

Abdominal migraine is a common cause of chronic and recurrent abdominal pain in children, according to a recent review. It is characterized by paroxysms of moderate to severe abdominal pain that is midline, periumbilical, or diffuse in location and accompanied by other symptoms including headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, or pallor. Despite the presence of comprehensive diagnostic criteria, it continues to be an underdiagnosed entity. Key points include:

- The average age of diagnosis is 3 to 10 years with peak incidence at 7 years.

- Most of the patients have a personal or family history of migraine.

- Pathophysiology of the condition is believed to be similar to that of other functional gastrointestinal disorders and cephalic migraine; it is also well recognized as a type of pediatric migraine variant.

- A careful history, thorough physical examination, and use of well-defined, symptom-based guidelines are needed to make a diagnosis.

- Although it resolves completely in most of the patients, these patients have a strong propensity to develop migraine later in life.

- Nonpharmacologic treatment options, including avoidance of triggers, behavior therapy, and dietary modifications should be the initial line of management.

Pediatric abdominal migraine: current perspectives on a lesser known entity. [Published online ahead of print April 24, 2018]. Pediatric Health Med Ther. doi:10.2147%2FPHMT.S127210.

Abdominal migraine is a common cause of chronic and recurrent abdominal pain in children, according to a recent review. It is characterized by paroxysms of moderate to severe abdominal pain that is midline, periumbilical, or diffuse in location and accompanied by other symptoms including headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, or pallor. Despite the presence of comprehensive diagnostic criteria, it continues to be an underdiagnosed entity. Key points include:

- The average age of diagnosis is 3 to 10 years with peak incidence at 7 years.

- Most of the patients have a personal or family history of migraine.

- Pathophysiology of the condition is believed to be similar to that of other functional gastrointestinal disorders and cephalic migraine; it is also well recognized as a type of pediatric migraine variant.

- A careful history, thorough physical examination, and use of well-defined, symptom-based guidelines are needed to make a diagnosis.

- Although it resolves completely in most of the patients, these patients have a strong propensity to develop migraine later in life.

- Nonpharmacologic treatment options, including avoidance of triggers, behavior therapy, and dietary modifications should be the initial line of management.

Pediatric abdominal migraine: current perspectives on a lesser known entity. [Published online ahead of print April 24, 2018]. Pediatric Health Med Ther. doi:10.2147%2FPHMT.S127210.

VIDEO: CASTLE-AF suggests atrial fibrillation burden better predicts outcomes

BOSTON – From the earliest days of using catheter ablation to treat atrial fibrillation (AF), in the 1990s, clinicians have defined ablation success based on whether patients had recurrence of their arrhythmia following treatment. New findings suggest that this standard was off, and that

The new study used data collected in the CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation vs. Standard Conventional Treatment in Patients With LV Dysfunction and AF) multicenter trial, which compared the efficacy of AF ablation with antiarrhythmic drug treatment in patients with heart failure for improving survival and freedom from hospitalization for heart failure. The trial’s primary finding showed that, in 363 randomized patients, AF ablation cut the primary adverse event rate by 38% relative to antiarrhythmic drug therapy (New Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27)

“There have been concerns about the high recurrence rate of AF following ablation,” with reported cumulative recurrence rates running as high as 80% by 5 years after ablation, noted Dr. Brachmann. “The news now is that recurrence alone doesn’t make a difference; we can still help patients” by reducing their AF burden, although he cautioned that this relationship has so far only been seen in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, the type of patients enrolled in CASTLE-AF.

“This information is very informative for clinicians counseling patients who undergo ablation. Ablation may not eliminate all of a patient’s AF, but it will substantially reduce it, and that’s associated with better outcomes,” commented Andrew D. Krahn, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “Early on using ablation, we had a curative approach and used ablation to ‘clip the wire.’ Now we have growing, objective evidence for ‘debulking’ the problem” working without the need to completely eliminate all AF episodes.

To run the post hoc analysis Dr. Brachmann and his associates categorized the 363 patients randomized in CASTLE-AF by the treatment they received during the study’s first 12 weeks: 150 patients underwent catheter ablation, and 210 received drug treatment, with three patients dropping out. Although this division of the patients diverged from the randomized subgroups, the ablated and drug-treated patients showed no significant differences when compared for several clinical parameters.

Ablation was significantly more effective than drug therapy for cutting atrial fibrillation burden, which started at an average of about 50% in all patients at baseline. AF burden fell to an average of about 10%-15% among the ablated patients when measured at several time points during follow-up, whereas AF burden remained at an average of about 50% or higher among the drug-treated patients.

A receiver operating characteristic analysis showed that change in AF burden after ablation produced a statistically significant 0.66 area-under-the-curve for the primary endpoint, which suggested that reduction in AF burden post ablation could account for about two-thirds of the drop in deaths and hospitalizations for heart failure. Among the nonablated patients the area-under-the-curve was an insignificant 0.49 showing that with drug treatment AF burden had no discernible relationship with outcomes.

One further observation in the new analysis was that a drop in AF burden was linked with improved outcomes regardless of whether or not a “blanking period” was imposed on the data. Researchers applied a 90-day blanking period after ablation when assessing the treatment’s efficacy to censor from the analysis recurrences that occurred soon after ablation. The need for a blanking period during the first 90 days “was put to rest” by this new analysis, Dr. Brachmann said.

CASTLE-AF was sponsored by Biotronik. Dr. Brachmann has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Biotronik and several other companies. Dr. Krahn has been a consultant to Medtronic and has received research support from Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Dr. Link had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Brachmann J et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-04.

This new analysis of data from the CASTLE-AF trial is exciting. It shows that, if we reduce the atrial fibrillation burden when we perform catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure, patients do better.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Until now, cardiac electrophysiologists who perform atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation have been too hard on themselves by counting as a failure every patient who develops an AF recurrence that lasts for 30 seconds or more. We know that patients who have a substantial drop in their AF burden after catheter ablation report feeling better even if they continue to have some AF events. When their AF burden drops substantially, patients are better able to work and perform activities of daily life. Many options, including noninvasive devices, are now available to monitor patients’ postablation change in AF burden.

We currently tell patients the success rates of catheter ablation on AF based on recurrence rates. Maybe we need to change our definition of success to a cut in AF burden. Based on these new findings, patients don’t need to be perfect after ablation, with absolutely no recurrences. I have patients who are very happy with their outcome after ablation who still have episodes. The success rate of catheter ablation for treating AF may be much better than we have thought.

Andrea M. Russo, MD , is professor and director of the electrophysiology and arrhythmia service at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, N.J. She made these comments during a press conference and in a video interview. She had no relevant disclosures.

This new analysis of data from the CASTLE-AF trial is exciting. It shows that, if we reduce the atrial fibrillation burden when we perform catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure, patients do better.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Until now, cardiac electrophysiologists who perform atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation have been too hard on themselves by counting as a failure every patient who develops an AF recurrence that lasts for 30 seconds or more. We know that patients who have a substantial drop in their AF burden after catheter ablation report feeling better even if they continue to have some AF events. When their AF burden drops substantially, patients are better able to work and perform activities of daily life. Many options, including noninvasive devices, are now available to monitor patients’ postablation change in AF burden.

We currently tell patients the success rates of catheter ablation on AF based on recurrence rates. Maybe we need to change our definition of success to a cut in AF burden. Based on these new findings, patients don’t need to be perfect after ablation, with absolutely no recurrences. I have patients who are very happy with their outcome after ablation who still have episodes. The success rate of catheter ablation for treating AF may be much better than we have thought.

Andrea M. Russo, MD , is professor and director of the electrophysiology and arrhythmia service at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, N.J. She made these comments during a press conference and in a video interview. She had no relevant disclosures.

This new analysis of data from the CASTLE-AF trial is exciting. It shows that, if we reduce the atrial fibrillation burden when we perform catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure, patients do better.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Until now, cardiac electrophysiologists who perform atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation have been too hard on themselves by counting as a failure every patient who develops an AF recurrence that lasts for 30 seconds or more. We know that patients who have a substantial drop in their AF burden after catheter ablation report feeling better even if they continue to have some AF events. When their AF burden drops substantially, patients are better able to work and perform activities of daily life. Many options, including noninvasive devices, are now available to monitor patients’ postablation change in AF burden.

We currently tell patients the success rates of catheter ablation on AF based on recurrence rates. Maybe we need to change our definition of success to a cut in AF burden. Based on these new findings, patients don’t need to be perfect after ablation, with absolutely no recurrences. I have patients who are very happy with their outcome after ablation who still have episodes. The success rate of catheter ablation for treating AF may be much better than we have thought.

Andrea M. Russo, MD , is professor and director of the electrophysiology and arrhythmia service at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, N.J. She made these comments during a press conference and in a video interview. She had no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – From the earliest days of using catheter ablation to treat atrial fibrillation (AF), in the 1990s, clinicians have defined ablation success based on whether patients had recurrence of their arrhythmia following treatment. New findings suggest that this standard was off, and that

The new study used data collected in the CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation vs. Standard Conventional Treatment in Patients With LV Dysfunction and AF) multicenter trial, which compared the efficacy of AF ablation with antiarrhythmic drug treatment in patients with heart failure for improving survival and freedom from hospitalization for heart failure. The trial’s primary finding showed that, in 363 randomized patients, AF ablation cut the primary adverse event rate by 38% relative to antiarrhythmic drug therapy (New Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27)

“There have been concerns about the high recurrence rate of AF following ablation,” with reported cumulative recurrence rates running as high as 80% by 5 years after ablation, noted Dr. Brachmann. “The news now is that recurrence alone doesn’t make a difference; we can still help patients” by reducing their AF burden, although he cautioned that this relationship has so far only been seen in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, the type of patients enrolled in CASTLE-AF.

“This information is very informative for clinicians counseling patients who undergo ablation. Ablation may not eliminate all of a patient’s AF, but it will substantially reduce it, and that’s associated with better outcomes,” commented Andrew D. Krahn, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “Early on using ablation, we had a curative approach and used ablation to ‘clip the wire.’ Now we have growing, objective evidence for ‘debulking’ the problem” working without the need to completely eliminate all AF episodes.

To run the post hoc analysis Dr. Brachmann and his associates categorized the 363 patients randomized in CASTLE-AF by the treatment they received during the study’s first 12 weeks: 150 patients underwent catheter ablation, and 210 received drug treatment, with three patients dropping out. Although this division of the patients diverged from the randomized subgroups, the ablated and drug-treated patients showed no significant differences when compared for several clinical parameters.

Ablation was significantly more effective than drug therapy for cutting atrial fibrillation burden, which started at an average of about 50% in all patients at baseline. AF burden fell to an average of about 10%-15% among the ablated patients when measured at several time points during follow-up, whereas AF burden remained at an average of about 50% or higher among the drug-treated patients.

A receiver operating characteristic analysis showed that change in AF burden after ablation produced a statistically significant 0.66 area-under-the-curve for the primary endpoint, which suggested that reduction in AF burden post ablation could account for about two-thirds of the drop in deaths and hospitalizations for heart failure. Among the nonablated patients the area-under-the-curve was an insignificant 0.49 showing that with drug treatment AF burden had no discernible relationship with outcomes.

One further observation in the new analysis was that a drop in AF burden was linked with improved outcomes regardless of whether or not a “blanking period” was imposed on the data. Researchers applied a 90-day blanking period after ablation when assessing the treatment’s efficacy to censor from the analysis recurrences that occurred soon after ablation. The need for a blanking period during the first 90 days “was put to rest” by this new analysis, Dr. Brachmann said.

CASTLE-AF was sponsored by Biotronik. Dr. Brachmann has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Biotronik and several other companies. Dr. Krahn has been a consultant to Medtronic and has received research support from Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Dr. Link had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Brachmann J et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-04.

BOSTON – From the earliest days of using catheter ablation to treat atrial fibrillation (AF), in the 1990s, clinicians have defined ablation success based on whether patients had recurrence of their arrhythmia following treatment. New findings suggest that this standard was off, and that

The new study used data collected in the CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation vs. Standard Conventional Treatment in Patients With LV Dysfunction and AF) multicenter trial, which compared the efficacy of AF ablation with antiarrhythmic drug treatment in patients with heart failure for improving survival and freedom from hospitalization for heart failure. The trial’s primary finding showed that, in 363 randomized patients, AF ablation cut the primary adverse event rate by 38% relative to antiarrhythmic drug therapy (New Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27)

“There have been concerns about the high recurrence rate of AF following ablation,” with reported cumulative recurrence rates running as high as 80% by 5 years after ablation, noted Dr. Brachmann. “The news now is that recurrence alone doesn’t make a difference; we can still help patients” by reducing their AF burden, although he cautioned that this relationship has so far only been seen in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, the type of patients enrolled in CASTLE-AF.

“This information is very informative for clinicians counseling patients who undergo ablation. Ablation may not eliminate all of a patient’s AF, but it will substantially reduce it, and that’s associated with better outcomes,” commented Andrew D. Krahn, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “Early on using ablation, we had a curative approach and used ablation to ‘clip the wire.’ Now we have growing, objective evidence for ‘debulking’ the problem” working without the need to completely eliminate all AF episodes.

To run the post hoc analysis Dr. Brachmann and his associates categorized the 363 patients randomized in CASTLE-AF by the treatment they received during the study’s first 12 weeks: 150 patients underwent catheter ablation, and 210 received drug treatment, with three patients dropping out. Although this division of the patients diverged from the randomized subgroups, the ablated and drug-treated patients showed no significant differences when compared for several clinical parameters.

Ablation was significantly more effective than drug therapy for cutting atrial fibrillation burden, which started at an average of about 50% in all patients at baseline. AF burden fell to an average of about 10%-15% among the ablated patients when measured at several time points during follow-up, whereas AF burden remained at an average of about 50% or higher among the drug-treated patients.

A receiver operating characteristic analysis showed that change in AF burden after ablation produced a statistically significant 0.66 area-under-the-curve for the primary endpoint, which suggested that reduction in AF burden post ablation could account for about two-thirds of the drop in deaths and hospitalizations for heart failure. Among the nonablated patients the area-under-the-curve was an insignificant 0.49 showing that with drug treatment AF burden had no discernible relationship with outcomes.

One further observation in the new analysis was that a drop in AF burden was linked with improved outcomes regardless of whether or not a “blanking period” was imposed on the data. Researchers applied a 90-day blanking period after ablation when assessing the treatment’s efficacy to censor from the analysis recurrences that occurred soon after ablation. The need for a blanking period during the first 90 days “was put to rest” by this new analysis, Dr. Brachmann said.

CASTLE-AF was sponsored by Biotronik. Dr. Brachmann has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Biotronik and several other companies. Dr. Krahn has been a consultant to Medtronic and has received research support from Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Dr. Link had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Brachmann J et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-04.

REPORTING FROM HEART RHYTHM 2018

Key clinical point: Higher atrial fibrillation (AF) burden was more important than AF recurrence for predicting bad outcomes post ablation.

Major finding: Patients whose AF burden fell to 5% or less had about a threefold higher rate of good outcomes, compared with other patients.

Study details: Post hoc analysis of 360 patients with heart failure and AF enrolled in CASTLE-AF, a multicenter, randomized trial.

Disclosures: CASTLE-AF was sponsored by Biotronik. Dr. Brachmann has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Biotronik and several other companies. Dr. Krahn has been a consultant to Medtronic and has received research support from Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Dr. Link had no disclosures.

Source: Brachmann J et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-04.

Migraine History and Recovery from Concussion

Athletes with a pre-injury migraine history may be at an elevated risk for a protracted return to school after concussion, especially girls and women, according to a recent study. High school and collegiate athletes (n=1265; 42% female) who sustained a sport-related concussion were monitored by athletic trainers using a web-based surveillance system that collects information about concussion recovery. Researchers found:

- There were 117 athletes (9.2%) who reported a pre-injury migraine history.

- Athletes with a history of migraine took a median of 6 days to return to academics and 15.5 days to return to athletics, while those with no migraine history took a median of 5 days to return to academics and 14 days to return to athletics.

- There were no statistically significant differences in days to return to school or athletics between the groups.

- However, a lower percentage of athletes with a history of migraine had returned to school after 7 days, 14 days, and 21 days post-injury.

- Stratifying the analyses by sex showed that this effect was significant in girls and women with pre-existing migraines, but not boys and men with pre-existing migraines.

Pre-injury migraine history as a risk factor for prolonged return to school and sports following concussion. [Published online ahead of print May 5, 2018]. J Neurotrauma. doi:10.1089/neu.2017.5443.

Athletes with a pre-injury migraine history may be at an elevated risk for a protracted return to school after concussion, especially girls and women, according to a recent study. High school and collegiate athletes (n=1265; 42% female) who sustained a sport-related concussion were monitored by athletic trainers using a web-based surveillance system that collects information about concussion recovery. Researchers found:

- There were 117 athletes (9.2%) who reported a pre-injury migraine history.

- Athletes with a history of migraine took a median of 6 days to return to academics and 15.5 days to return to athletics, while those with no migraine history took a median of 5 days to return to academics and 14 days to return to athletics.

- There were no statistically significant differences in days to return to school or athletics between the groups.

- However, a lower percentage of athletes with a history of migraine had returned to school after 7 days, 14 days, and 21 days post-injury.

- Stratifying the analyses by sex showed that this effect was significant in girls and women with pre-existing migraines, but not boys and men with pre-existing migraines.

Pre-injury migraine history as a risk factor for prolonged return to school and sports following concussion. [Published online ahead of print May 5, 2018]. J Neurotrauma. doi:10.1089/neu.2017.5443.

Athletes with a pre-injury migraine history may be at an elevated risk for a protracted return to school after concussion, especially girls and women, according to a recent study. High school and collegiate athletes (n=1265; 42% female) who sustained a sport-related concussion were monitored by athletic trainers using a web-based surveillance system that collects information about concussion recovery. Researchers found:

- There were 117 athletes (9.2%) who reported a pre-injury migraine history.

- Athletes with a history of migraine took a median of 6 days to return to academics and 15.5 days to return to athletics, while those with no migraine history took a median of 5 days to return to academics and 14 days to return to athletics.

- There were no statistically significant differences in days to return to school or athletics between the groups.

- However, a lower percentage of athletes with a history of migraine had returned to school after 7 days, 14 days, and 21 days post-injury.

- Stratifying the analyses by sex showed that this effect was significant in girls and women with pre-existing migraines, but not boys and men with pre-existing migraines.

Pre-injury migraine history as a risk factor for prolonged return to school and sports following concussion. [Published online ahead of print May 5, 2018]. J Neurotrauma. doi:10.1089/neu.2017.5443.

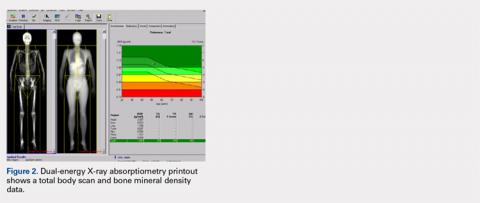

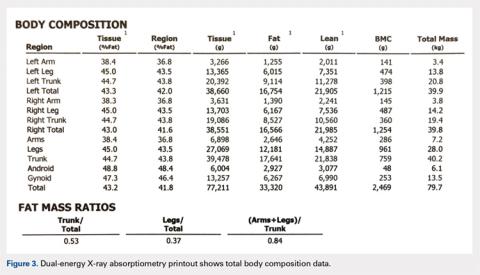

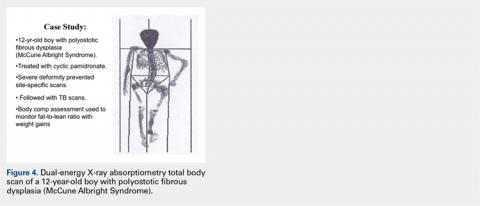

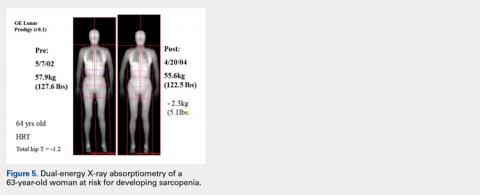

The Potential Value of Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry in Orthopedics

ABSTRACT

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is a well-established technology with an important and well-known role in measuring bone mineral density (BMD) for the purpose of determining fracture risk, diagnosing osteoporosis, and monitoring treatment efficacy. However, aside from the assessment of bone status, DXA is likely underutilized in the field of orthopedics, and most orthopedists may not be aware of the full capabilities of DXA, particularly with regard to total body scans and body composition assessment. For example, DXA would be a valuable tool for monitoring body composition after surgery where compensatory changes in the affected limb may lead to right-left asymmetry (eg, tracking lean mass change after knee surgery), rehabilitation regimens for athletes, congenital and metabolic disorders that affect the musculoskeletal system, or monitoring sarcopenia and frailty in the elderly. Furthermore, preoperative and postoperative regional scans can track BMD changes during healing or alert surgeons to impending problems such as loss of periprosthetic bone, which could lead to implant failure. This article discusses the capabilities of DXA and how this technology could be better used to the advantage of the attending orthopedist.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, abbreviated as “DXA,” (although usually abbreviated in older literature as “DEXA”) was first introduced in 1987 (Hologic QDR-1000 system, Hologic, Inc) and immediately made all previous forms of radiation-based bone mineral density (BMD) measurement systems obsolete.1 Since then, there have been many generations of the technology, with the main US manufacturers in 2017 being Hologic, Inc. and GE Lunar. There are 2 forms of DXA, peripheral systems (which usually measure BMD only in the radius, finger bones, or calcaneus) and central systems (which measure the radius, proximal femur [“hip”], lumbar spine, total body, and custom sites). The general principle of how DXA works is based on the differential attenuation of photons by bone, fat, and lean mass.2 The DXA technique uses a low- and high-energy X-ray beam produced by an X-ray tube. With the low-energy beam, attenuation by bone is greater than attenuation by soft tissue. With the high-energy beam, attenuation by bone and soft tissues are similar. The dual X-ray beams are passed through the body regions being scanned (usually posterioanteriorly), and the differential attenuation by bone and soft tissue is analyzed to produce BMD estimates. In addition, a high-quality image is produced to enable the operator of the DXA system to verify that the appropriate body region was scanned. It is important to realize that DXA is 2-dimensional (which is sometimes cited as a weakness of DXA), and the units of BMD are grams of mineral per centimeter squared (g/cm2).

Continue to: When assessing bone status...

When assessing bone status for the purpose of determining if a patient is normal, osteopenic, or osteoporotic, the skeletal sites (called regions of interest [ROI]) typically scanned are the proximal femur, lumbar spine, and radius. The BMD of the patient is then compared to a manufacturer-provided normative database of young adults (the logic being that the BMD in the young adult normative population represents maximal peak bone mass). Total body BMD and body composition can also be quantified (grams of lean and fat mass), and custom scans can be designed for other skeletal sites. Specifically, a patient’s BMD is compared to a database of sex- and age-adjusted normal values, and the deviation from normal is expressed as a T-score (the number of standard deviations the patient's BMD is above or below the average BMD of the young adult reference population) and Z-scores (the number of standard deviations a patient's BMD is above or below the average BMD of a sex- and age-matched reference population).3 The International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) has developed and published well-accepted guidelines used to assist in acquiring high-quality DXA scans and for the diagnosis of osteoporosis using BMD. The accuracy and, especially, the precision of DXA scans can be remarkable when they are performed by trained technologists, and thus, serial scans can be performed to monitor BMD and body composition changes with aging or in response to treatment.

Because of the nature of the scan mechanics and speed, the effective radiation dose with DXA is very low, expressed in microSieverts.4,5 Generally, the radiation exposure from a series of the lumbar spine, proximal femur, and distal radius is about the same as daily background radiation. Even total body scans present very low exposure due to the scan speed at which any 1 body part is exposed for only a fraction of a second.

BENEFITS OF USING DXA FOR THE ORTHEOPEDIST

At the time of this writing in 2018, the presumption could be made that most physicians in the specialties of internal medicine, rheumatology, endocrinology, radiology, and orthopedics were familiar with the capabilities of DXA to assess BMD for the purpose of diagnosing osteoporosis. However, DXA is likely underused for other purposes, as orthopedists may be unaware of the full capabilities of DXA. Printouts after a scan contain more information than simply BMD, and there are more features and applications of DXA that can potentially be useful to orthopedists.

BONE SIZE

Data from a DXA scan are expressed not only as g/cm2 (BMD) but also as total grams in the ROI (known as bone mineral content, abbreviated as BMC), and cm2 (area of the ROI). These data may appear on a separate page, being considered ancillary results. The latter 2 variables are rarely included on a report sent to a referring physician; therefore, awareness of their value is probably limited. However, there are instances where such information could be valuable when interpreting results, especially bone size.6,7 For example, on occasion, patients present with osteopenic lumbar vertebrate but larger than normal vertebral size (area). Many studies have shown that bone size is directly related to bone strength and thus fracture risk.8,9 Although an understudied phenomenon, large vertebral body size could be protective, counteracting a lower than optimal BMD. Further, because the area of the ROI is measured, it is possible to calculate the bone width (or measure directly with a ruler tool in the software if available) for the area measured. This is especially feasible for tubular bones such as the midshaft of the radius, or more specifically, the classic DXA ROI being the area approximately one third the length of the radius from the distal end, the radius 33% region (actually based on ulna length). Consequently, it is possible to use the width of the radius 33% ROI in addition to BMD and T-score when assessing fracture risk.

CASE STUDY