User login

Use of a Core Reamer for the Resection of a Central Distal Femoral Physeal Bone Bridge: A Novel Technique with 3-Year Follow-up

ABSTRACT

A central distal femoral physeal bone bridge in a boy aged 5 years and 7 months was resected with a fluoroscopically guided core reamer placed through a lateral parapatellar approach. At 3-year follow-up, the boy’s leg-length discrepancy was 3.0 cm (3.9 cm preoperatively), and the physeal bone bridge did not recur. The patient had full function and no pain or other patellofemoral complaints. This technique provided direct access to the physeal bone bridge, and complete resection was performed without injury to the adjacent physeal cartilage in the medial and lateral columns of the distal femur, which is expected to grow normally in the absence of the bridge.

A physeal bone bridge is an osseous connection that forms across a physis. It may cause partial premature physeal arrest. Angular deformity and limb-length discrepancy are the main complications caused by physeal bone bridges.1-4 The indications for the treatment of physeal bridges are well documented.1-5 Trauma and infection are common causes of distal femoral physeal bone bridges. Arkader and colleagues6 showed that among different types of physeal bridges, the Salter-Harris type is significantly associated with complications, among which growth arrest is the most common and occurs in 27.4% of all patients.

The treatment of distal femoral physeal bone bridges is technically difficult and provides variable results. Poor results are reported in 13% to 40% of patients.7-10 Procedure failure has been attributed to incomplete resection with the persistent tethering and dislodgement of the graft.11 Methods with improved efficacy for the removal of central physeal bridges will help prevent reformation after treatment. We have used a novel technique that allows the direct resection of a central physeal bone bridge in the distal femur through the use of a fluoroscopically guided core reamer. This technique enables the complete removal of the bone bridge and the direct visual assessment of the remaining physis. The patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

A 3-year-old boy with a history of hemifacial microsomia presented for the evaluation of genu valgum and leg-length discrepancy. His intermalleolar distance at that time was 8 cm. A standing radiograph of his lower extremities demonstrated changes consistent with physiologic genu valgum. He had no history of knee trauma, infection, or pain.

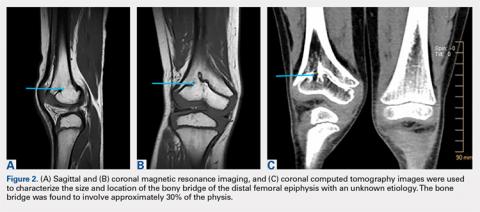

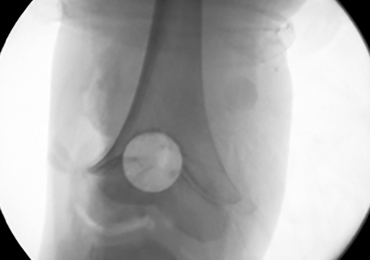

At the age of 5 years and 7 months, the patient returned for a repeat evaluation and was noted to exhibit the progressive valgus deformity of the right leg and a leg-length discrepancy of 3.9 cm (Figure 1).

Continue to: With the patient supine on the operating...

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

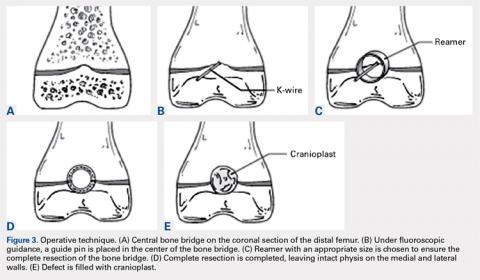

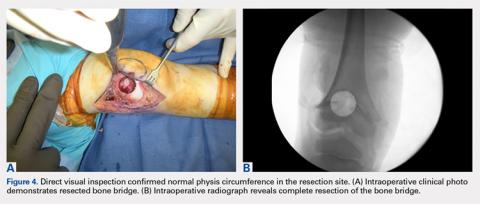

With the patient supine on the operating table and after the administration of general anesthesia, 3-dimensional (3-D) fluoroscopy was used to localize the bone bridge, which confirmed the fluoroscopic location that was previously visualized through preoperative 3-D imaging. The leg was elevated, and a tourniquet was applied and inflated. A lateral parapatellar approach was used to isolate the distal femoral physis anteriorly because the bone bridge was centered just lateral to the central portion of the distal femoral physis. A Kirschner wire was placed in the center of the bridge under anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic imaging (Figures 3A-3E).

OUTCOME

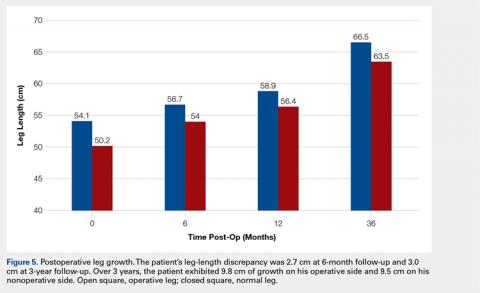

The patient healed uneventfully, and early range-of-motion exercises were started 6 weeks postoperatively. At 6-month follow-up, his leg-length discrepancy was 2.7 cm, and the bone bridge did not recur. At 3-year follow-up, his leg-length discrepancy was 3.0 cm, and the bone bridge did not recur. Over the 3 years postoperatively, the patient exhibited 9.8 cm of growth on his operative side and 9.5 cm on his nonoperative side (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Given the considerable growth potential of the distal femoral physis,1,14-16 an injury to the distal femoral physis and the formation of a physeal bone bridge can have a profound effect on a young patient in terms of leg-length discrepancy and angular deformity. Fracture from trauma or infection is a common cause of physeal bone bridges.6,17-19 The etiology of our patient’s distal femoral physeal bone bridge is idiopathic, which is considerably less common than other etiologies, and the incidence of idiopathic physeal bone bridge formation is not well established in the literature. Hresko and Kasser21 identified atraumatic physeal bone bridge formations in 7 patients. Among the 13 patients with physeal bone bridges described by Broughton and colleagues,20 the cause of bridge formation is unknown in 1.

Physeal bone bridges that form centrally are particularly challenging because they are difficult to visualize through a peripheral approach. A number of methods for resecting central physeal bone bridges have been described. These methods have varying degrees of success. In 1981, Langenskiöld7 first described the creation of a metaphyseal mirror and the use of a dental mirror for visualization. This technique, however, yielded unfavorable results in 16% of patients. Williamson and Staheli9 reported poor results in 23% of patients. Loraas and Schmale4 described the use of an endoscope, termed an osteoscope, for visualization, citing advantages of superior illumination and potential for image magnification and capture. Marsh and Polzhofer8 also showed this technique to have low morbidity but poor results in 13% of patients, whereas Moreta and colleagues10 reported poor results in 2 out of 5 patients. The rate of poor results of these methods may be related to the technical difficulty of using dental mirrors and arthroscopes and can be improved by highly efficient direct methods with improved visualization, such as the method described in this article.

Continue to: Proper imaging is necessary for...

Proper imaging is necessary for the accurate quantification of bone bridges to determine resectability and to identify the best surgical approach to resection. MRI with software for the generation of 3-D physeal maps is a reproducible method with good interobserver reliability.22,23 Intraoperative computer-assisted imaging also is beneficial for determining the extent and location of the resection to ensure complete bone bridge removal.24

To our knowledge, a direct approach through parapatellar arthrotomy for the resection of a centrally located distal femoral physeal bone bridge has not been previously described. This novel technique provided direct access to the physeal bone bridge and was performed without injuring the adjacent physeal cartilage in the medial and lateral columns of the distal femur, which may grow normally in the absence of the bridge. Instead of using a lateral or medial approach with a metaphyseal window,4 we directly approached this central bar through a parapatellar approach and were able to completely resect it under direct visualization. This obviated the need for an arthroscope or dental mirror. To remove the entire physeal bone bridge, we needed to resect completely from the anterior cortex to the posterior cortex. Although this technique potentially increased the risk of iatrogenic fracture, we believed that this risk would not differ greatly from that of disrupting the medial or lateral metaphysis and would be more stable with either axial and torsion load. At 3-year follow-up, the patient exhibited restored normal growth in his operative limb relative to that in his nonoperative limb, had not developed angular deformity, and had maintained his previously developed limb-length discrepancy that could be corrected with the epiphysiodesis of his opposite limb at a later date.

The limitations to this technique include the fact that it may be most effective with small-to moderate-sized central physeal bone bridges, although resection has shown good results with up to 70% physeal involvement.8 In this patient, the bone bridge was moderately sized (30% of the physis), centrally located, and clearly visible on fluoroscopy. These characteristics increased the technical safety and ease of the procedure. The resection of large, peripheral bridges may destabilize the distal femur. The destabilization of the distal femur, in turn, can lead to fracture. Patellofemoral mechanics may also be affected during the treatment of distal femoral physeal bone bridges. This patient has not experienced any patellofemoral dysfunction or symptoms. Given the patient’s age and significant amount of remaining growth, he will need close monitoring until he reaches skeletal maturity.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

1. Murphy GA. Disorders of tendons and fascia and adolescent and adult pes planus. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 12th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby-Elsevier; 2013:3966-3972.

2. Khoshhal KI, Kiefer GN. Physeal bridge resection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(1):47-58. doi:10.5435/00124635-200501000-00007.

3. Stans AA. Excision of physeal bar. In: Wiesel SW, ed. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:1244-1249.

4. Loraas EK, Schmale GA. Endoscopically aided physeal bar takedown and guided growth for the treatment of angular limb deformity. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21(4):348-351. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e328346d308.

5. Inoue T, Naito M, Fuhii T, Akiyoshi Y, Yoshimura I, Takamura K. Partial physeal growth arrest treated by bridge resection and artificial dura substitute interposition. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15(1):65-69. doi:10.1097/01202412-200601000-00014.

6. Arkader A, Warner WC Jr, Horn BD, Shaw RN, Wells L. Predicting the outcome of physeal fractures of the distal femur. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):703-708. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e3180dca0e5.

7. Langenskiöld A. Surgical treatment of partial closure of the growth plate. J Pediatr Orthop. 1981;1(1):3-11. doi:10.1097/01241398-198101010-00002.

8. Marsh JS, Polzhofer GK. Arthroscopically assisted central physeal bar resection. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(2):255-259. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000218533.43986.e1.

9. Williamson RV, Staheli LT. Partial physeal growth arrest: treatment by bridge resection and fat interposition. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10(6):769-776. doi:10.1097/01241398-199011000-00012.

10. Moreta J, Abril JC, Miranda C. Arthroscopy-assisted resection-interposition of post-traumatic central physeal bridges. Rev Esp Cir Orthop Traumatol. 2013;57(5):333-339. doi:10.1016/j.recot.2013.07.004.

11. Hasler CC, Foster BK. Secondary tethers after physeal bar resection: a common source of failure? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;405:242-249.

12. Paley D, Bhave A, Herzenberg JE, Bowen JR. Multiplier method for predicting limb-length discrepancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(10):1432-1446. doi:10.2106/00004623-200010000-00010.

13. Khoshhal KI, Kiefer GN. Physeal bridge resection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(1):47-58. doi:10.5435/00124635-200501000-00007.

14. Rathjen KE, Kim HKW. Physeal injuries and growth disturbances. In: Flynn JM, Skaggs DL, Waters PM, eds. Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children. 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters-Kluwer; 2015:135-137.

15. Peterson CA, Peterson HA. Analysis of the incidence of injuries to the epiphyseal growth plate. J Trauma. 1972;12(4):275-281. doi:10.1097/00005373-197204000-00002.

16. Pritchett JW. Longitudinal growth and growth-plate activity in the lower extremity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:274-279.

17. Cassebaum WH, Patterson AH. Fracture of the distal femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1965;41:79-91. doi:10.1097/00003086-196500410-00009.

18. Dahl WJ, Silva S, Vanderhave KL. Distal femoral physeal fixation: are smooth pins really safe? J Pedatir Orthop. 2014;34(2):134-138. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000083.

19. Roberts J. Fracture separation of the distal femoral epiphyseal growth line. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1324.

20. Broughton NS, Dickens DR, Cole WG, Menelaus MB. Epiphyseolysis for partial growth plate arrest. Results after four years or at maturity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(1):13-16. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.71B1.2914983.

21. Hresko MT, Kasser JR. Physeal arrest about the knee associated with non-physeal fractures in the lower extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(5):698-703. doi:10.2106/00004623-198971050-00009.

22. Lurie B, Koff MF, Shah P, et al. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of physeal injury: reliability and clinical utility. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(3):239-245. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000104.

23. Sailhan F, Chotel F, Guibal AL, et al. Three-dimensional MR imaging in the assessment of physeal growth arrest. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(9):1600-1608. doi:10.1007/s00330-004-2319-z.

24. Kang HG, Yoon SJ, Kim JR. Resection of a physeal bar under computer-assisted guidance. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(10):1452-1455. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.24587.

ABSTRACT

A central distal femoral physeal bone bridge in a boy aged 5 years and 7 months was resected with a fluoroscopically guided core reamer placed through a lateral parapatellar approach. At 3-year follow-up, the boy’s leg-length discrepancy was 3.0 cm (3.9 cm preoperatively), and the physeal bone bridge did not recur. The patient had full function and no pain or other patellofemoral complaints. This technique provided direct access to the physeal bone bridge, and complete resection was performed without injury to the adjacent physeal cartilage in the medial and lateral columns of the distal femur, which is expected to grow normally in the absence of the bridge.

A physeal bone bridge is an osseous connection that forms across a physis. It may cause partial premature physeal arrest. Angular deformity and limb-length discrepancy are the main complications caused by physeal bone bridges.1-4 The indications for the treatment of physeal bridges are well documented.1-5 Trauma and infection are common causes of distal femoral physeal bone bridges. Arkader and colleagues6 showed that among different types of physeal bridges, the Salter-Harris type is significantly associated with complications, among which growth arrest is the most common and occurs in 27.4% of all patients.

The treatment of distal femoral physeal bone bridges is technically difficult and provides variable results. Poor results are reported in 13% to 40% of patients.7-10 Procedure failure has been attributed to incomplete resection with the persistent tethering and dislodgement of the graft.11 Methods with improved efficacy for the removal of central physeal bridges will help prevent reformation after treatment. We have used a novel technique that allows the direct resection of a central physeal bone bridge in the distal femur through the use of a fluoroscopically guided core reamer. This technique enables the complete removal of the bone bridge and the direct visual assessment of the remaining physis. The patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

A 3-year-old boy with a history of hemifacial microsomia presented for the evaluation of genu valgum and leg-length discrepancy. His intermalleolar distance at that time was 8 cm. A standing radiograph of his lower extremities demonstrated changes consistent with physiologic genu valgum. He had no history of knee trauma, infection, or pain.

At the age of 5 years and 7 months, the patient returned for a repeat evaluation and was noted to exhibit the progressive valgus deformity of the right leg and a leg-length discrepancy of 3.9 cm (Figure 1).

Continue to: With the patient supine on the operating...

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

With the patient supine on the operating table and after the administration of general anesthesia, 3-dimensional (3-D) fluoroscopy was used to localize the bone bridge, which confirmed the fluoroscopic location that was previously visualized through preoperative 3-D imaging. The leg was elevated, and a tourniquet was applied and inflated. A lateral parapatellar approach was used to isolate the distal femoral physis anteriorly because the bone bridge was centered just lateral to the central portion of the distal femoral physis. A Kirschner wire was placed in the center of the bridge under anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic imaging (Figures 3A-3E).

OUTCOME

The patient healed uneventfully, and early range-of-motion exercises were started 6 weeks postoperatively. At 6-month follow-up, his leg-length discrepancy was 2.7 cm, and the bone bridge did not recur. At 3-year follow-up, his leg-length discrepancy was 3.0 cm, and the bone bridge did not recur. Over the 3 years postoperatively, the patient exhibited 9.8 cm of growth on his operative side and 9.5 cm on his nonoperative side (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Given the considerable growth potential of the distal femoral physis,1,14-16 an injury to the distal femoral physis and the formation of a physeal bone bridge can have a profound effect on a young patient in terms of leg-length discrepancy and angular deformity. Fracture from trauma or infection is a common cause of physeal bone bridges.6,17-19 The etiology of our patient’s distal femoral physeal bone bridge is idiopathic, which is considerably less common than other etiologies, and the incidence of idiopathic physeal bone bridge formation is not well established in the literature. Hresko and Kasser21 identified atraumatic physeal bone bridge formations in 7 patients. Among the 13 patients with physeal bone bridges described by Broughton and colleagues,20 the cause of bridge formation is unknown in 1.

Physeal bone bridges that form centrally are particularly challenging because they are difficult to visualize through a peripheral approach. A number of methods for resecting central physeal bone bridges have been described. These methods have varying degrees of success. In 1981, Langenskiöld7 first described the creation of a metaphyseal mirror and the use of a dental mirror for visualization. This technique, however, yielded unfavorable results in 16% of patients. Williamson and Staheli9 reported poor results in 23% of patients. Loraas and Schmale4 described the use of an endoscope, termed an osteoscope, for visualization, citing advantages of superior illumination and potential for image magnification and capture. Marsh and Polzhofer8 also showed this technique to have low morbidity but poor results in 13% of patients, whereas Moreta and colleagues10 reported poor results in 2 out of 5 patients. The rate of poor results of these methods may be related to the technical difficulty of using dental mirrors and arthroscopes and can be improved by highly efficient direct methods with improved visualization, such as the method described in this article.

Continue to: Proper imaging is necessary for...

Proper imaging is necessary for the accurate quantification of bone bridges to determine resectability and to identify the best surgical approach to resection. MRI with software for the generation of 3-D physeal maps is a reproducible method with good interobserver reliability.22,23 Intraoperative computer-assisted imaging also is beneficial for determining the extent and location of the resection to ensure complete bone bridge removal.24

To our knowledge, a direct approach through parapatellar arthrotomy for the resection of a centrally located distal femoral physeal bone bridge has not been previously described. This novel technique provided direct access to the physeal bone bridge and was performed without injuring the adjacent physeal cartilage in the medial and lateral columns of the distal femur, which may grow normally in the absence of the bridge. Instead of using a lateral or medial approach with a metaphyseal window,4 we directly approached this central bar through a parapatellar approach and were able to completely resect it under direct visualization. This obviated the need for an arthroscope or dental mirror. To remove the entire physeal bone bridge, we needed to resect completely from the anterior cortex to the posterior cortex. Although this technique potentially increased the risk of iatrogenic fracture, we believed that this risk would not differ greatly from that of disrupting the medial or lateral metaphysis and would be more stable with either axial and torsion load. At 3-year follow-up, the patient exhibited restored normal growth in his operative limb relative to that in his nonoperative limb, had not developed angular deformity, and had maintained his previously developed limb-length discrepancy that could be corrected with the epiphysiodesis of his opposite limb at a later date.

The limitations to this technique include the fact that it may be most effective with small-to moderate-sized central physeal bone bridges, although resection has shown good results with up to 70% physeal involvement.8 In this patient, the bone bridge was moderately sized (30% of the physis), centrally located, and clearly visible on fluoroscopy. These characteristics increased the technical safety and ease of the procedure. The resection of large, peripheral bridges may destabilize the distal femur. The destabilization of the distal femur, in turn, can lead to fracture. Patellofemoral mechanics may also be affected during the treatment of distal femoral physeal bone bridges. This patient has not experienced any patellofemoral dysfunction or symptoms. Given the patient’s age and significant amount of remaining growth, he will need close monitoring until he reaches skeletal maturity.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

ABSTRACT

A central distal femoral physeal bone bridge in a boy aged 5 years and 7 months was resected with a fluoroscopically guided core reamer placed through a lateral parapatellar approach. At 3-year follow-up, the boy’s leg-length discrepancy was 3.0 cm (3.9 cm preoperatively), and the physeal bone bridge did not recur. The patient had full function and no pain or other patellofemoral complaints. This technique provided direct access to the physeal bone bridge, and complete resection was performed without injury to the adjacent physeal cartilage in the medial and lateral columns of the distal femur, which is expected to grow normally in the absence of the bridge.

A physeal bone bridge is an osseous connection that forms across a physis. It may cause partial premature physeal arrest. Angular deformity and limb-length discrepancy are the main complications caused by physeal bone bridges.1-4 The indications for the treatment of physeal bridges are well documented.1-5 Trauma and infection are common causes of distal femoral physeal bone bridges. Arkader and colleagues6 showed that among different types of physeal bridges, the Salter-Harris type is significantly associated with complications, among which growth arrest is the most common and occurs in 27.4% of all patients.

The treatment of distal femoral physeal bone bridges is technically difficult and provides variable results. Poor results are reported in 13% to 40% of patients.7-10 Procedure failure has been attributed to incomplete resection with the persistent tethering and dislodgement of the graft.11 Methods with improved efficacy for the removal of central physeal bridges will help prevent reformation after treatment. We have used a novel technique that allows the direct resection of a central physeal bone bridge in the distal femur through the use of a fluoroscopically guided core reamer. This technique enables the complete removal of the bone bridge and the direct visual assessment of the remaining physis. The patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

A 3-year-old boy with a history of hemifacial microsomia presented for the evaluation of genu valgum and leg-length discrepancy. His intermalleolar distance at that time was 8 cm. A standing radiograph of his lower extremities demonstrated changes consistent with physiologic genu valgum. He had no history of knee trauma, infection, or pain.

At the age of 5 years and 7 months, the patient returned for a repeat evaluation and was noted to exhibit the progressive valgus deformity of the right leg and a leg-length discrepancy of 3.9 cm (Figure 1).

Continue to: With the patient supine on the operating...

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

With the patient supine on the operating table and after the administration of general anesthesia, 3-dimensional (3-D) fluoroscopy was used to localize the bone bridge, which confirmed the fluoroscopic location that was previously visualized through preoperative 3-D imaging. The leg was elevated, and a tourniquet was applied and inflated. A lateral parapatellar approach was used to isolate the distal femoral physis anteriorly because the bone bridge was centered just lateral to the central portion of the distal femoral physis. A Kirschner wire was placed in the center of the bridge under anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic imaging (Figures 3A-3E).

OUTCOME

The patient healed uneventfully, and early range-of-motion exercises were started 6 weeks postoperatively. At 6-month follow-up, his leg-length discrepancy was 2.7 cm, and the bone bridge did not recur. At 3-year follow-up, his leg-length discrepancy was 3.0 cm, and the bone bridge did not recur. Over the 3 years postoperatively, the patient exhibited 9.8 cm of growth on his operative side and 9.5 cm on his nonoperative side (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Given the considerable growth potential of the distal femoral physis,1,14-16 an injury to the distal femoral physis and the formation of a physeal bone bridge can have a profound effect on a young patient in terms of leg-length discrepancy and angular deformity. Fracture from trauma or infection is a common cause of physeal bone bridges.6,17-19 The etiology of our patient’s distal femoral physeal bone bridge is idiopathic, which is considerably less common than other etiologies, and the incidence of idiopathic physeal bone bridge formation is not well established in the literature. Hresko and Kasser21 identified atraumatic physeal bone bridge formations in 7 patients. Among the 13 patients with physeal bone bridges described by Broughton and colleagues,20 the cause of bridge formation is unknown in 1.

Physeal bone bridges that form centrally are particularly challenging because they are difficult to visualize through a peripheral approach. A number of methods for resecting central physeal bone bridges have been described. These methods have varying degrees of success. In 1981, Langenskiöld7 first described the creation of a metaphyseal mirror and the use of a dental mirror for visualization. This technique, however, yielded unfavorable results in 16% of patients. Williamson and Staheli9 reported poor results in 23% of patients. Loraas and Schmale4 described the use of an endoscope, termed an osteoscope, for visualization, citing advantages of superior illumination and potential for image magnification and capture. Marsh and Polzhofer8 also showed this technique to have low morbidity but poor results in 13% of patients, whereas Moreta and colleagues10 reported poor results in 2 out of 5 patients. The rate of poor results of these methods may be related to the technical difficulty of using dental mirrors and arthroscopes and can be improved by highly efficient direct methods with improved visualization, such as the method described in this article.

Continue to: Proper imaging is necessary for...

Proper imaging is necessary for the accurate quantification of bone bridges to determine resectability and to identify the best surgical approach to resection. MRI with software for the generation of 3-D physeal maps is a reproducible method with good interobserver reliability.22,23 Intraoperative computer-assisted imaging also is beneficial for determining the extent and location of the resection to ensure complete bone bridge removal.24

To our knowledge, a direct approach through parapatellar arthrotomy for the resection of a centrally located distal femoral physeal bone bridge has not been previously described. This novel technique provided direct access to the physeal bone bridge and was performed without injuring the adjacent physeal cartilage in the medial and lateral columns of the distal femur, which may grow normally in the absence of the bridge. Instead of using a lateral or medial approach with a metaphyseal window,4 we directly approached this central bar through a parapatellar approach and were able to completely resect it under direct visualization. This obviated the need for an arthroscope or dental mirror. To remove the entire physeal bone bridge, we needed to resect completely from the anterior cortex to the posterior cortex. Although this technique potentially increased the risk of iatrogenic fracture, we believed that this risk would not differ greatly from that of disrupting the medial or lateral metaphysis and would be more stable with either axial and torsion load. At 3-year follow-up, the patient exhibited restored normal growth in his operative limb relative to that in his nonoperative limb, had not developed angular deformity, and had maintained his previously developed limb-length discrepancy that could be corrected with the epiphysiodesis of his opposite limb at a later date.

The limitations to this technique include the fact that it may be most effective with small-to moderate-sized central physeal bone bridges, although resection has shown good results with up to 70% physeal involvement.8 In this patient, the bone bridge was moderately sized (30% of the physis), centrally located, and clearly visible on fluoroscopy. These characteristics increased the technical safety and ease of the procedure. The resection of large, peripheral bridges may destabilize the distal femur. The destabilization of the distal femur, in turn, can lead to fracture. Patellofemoral mechanics may also be affected during the treatment of distal femoral physeal bone bridges. This patient has not experienced any patellofemoral dysfunction or symptoms. Given the patient’s age and significant amount of remaining growth, he will need close monitoring until he reaches skeletal maturity.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

1. Murphy GA. Disorders of tendons and fascia and adolescent and adult pes planus. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 12th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby-Elsevier; 2013:3966-3972.

2. Khoshhal KI, Kiefer GN. Physeal bridge resection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(1):47-58. doi:10.5435/00124635-200501000-00007.

3. Stans AA. Excision of physeal bar. In: Wiesel SW, ed. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:1244-1249.

4. Loraas EK, Schmale GA. Endoscopically aided physeal bar takedown and guided growth for the treatment of angular limb deformity. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21(4):348-351. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e328346d308.

5. Inoue T, Naito M, Fuhii T, Akiyoshi Y, Yoshimura I, Takamura K. Partial physeal growth arrest treated by bridge resection and artificial dura substitute interposition. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15(1):65-69. doi:10.1097/01202412-200601000-00014.

6. Arkader A, Warner WC Jr, Horn BD, Shaw RN, Wells L. Predicting the outcome of physeal fractures of the distal femur. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):703-708. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e3180dca0e5.

7. Langenskiöld A. Surgical treatment of partial closure of the growth plate. J Pediatr Orthop. 1981;1(1):3-11. doi:10.1097/01241398-198101010-00002.

8. Marsh JS, Polzhofer GK. Arthroscopically assisted central physeal bar resection. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(2):255-259. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000218533.43986.e1.

9. Williamson RV, Staheli LT. Partial physeal growth arrest: treatment by bridge resection and fat interposition. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10(6):769-776. doi:10.1097/01241398-199011000-00012.

10. Moreta J, Abril JC, Miranda C. Arthroscopy-assisted resection-interposition of post-traumatic central physeal bridges. Rev Esp Cir Orthop Traumatol. 2013;57(5):333-339. doi:10.1016/j.recot.2013.07.004.

11. Hasler CC, Foster BK. Secondary tethers after physeal bar resection: a common source of failure? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;405:242-249.

12. Paley D, Bhave A, Herzenberg JE, Bowen JR. Multiplier method for predicting limb-length discrepancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(10):1432-1446. doi:10.2106/00004623-200010000-00010.

13. Khoshhal KI, Kiefer GN. Physeal bridge resection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(1):47-58. doi:10.5435/00124635-200501000-00007.

14. Rathjen KE, Kim HKW. Physeal injuries and growth disturbances. In: Flynn JM, Skaggs DL, Waters PM, eds. Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children. 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters-Kluwer; 2015:135-137.

15. Peterson CA, Peterson HA. Analysis of the incidence of injuries to the epiphyseal growth plate. J Trauma. 1972;12(4):275-281. doi:10.1097/00005373-197204000-00002.

16. Pritchett JW. Longitudinal growth and growth-plate activity in the lower extremity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:274-279.

17. Cassebaum WH, Patterson AH. Fracture of the distal femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1965;41:79-91. doi:10.1097/00003086-196500410-00009.

18. Dahl WJ, Silva S, Vanderhave KL. Distal femoral physeal fixation: are smooth pins really safe? J Pedatir Orthop. 2014;34(2):134-138. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000083.

19. Roberts J. Fracture separation of the distal femoral epiphyseal growth line. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1324.

20. Broughton NS, Dickens DR, Cole WG, Menelaus MB. Epiphyseolysis for partial growth plate arrest. Results after four years or at maturity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(1):13-16. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.71B1.2914983.

21. Hresko MT, Kasser JR. Physeal arrest about the knee associated with non-physeal fractures in the lower extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(5):698-703. doi:10.2106/00004623-198971050-00009.

22. Lurie B, Koff MF, Shah P, et al. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of physeal injury: reliability and clinical utility. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(3):239-245. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000104.

23. Sailhan F, Chotel F, Guibal AL, et al. Three-dimensional MR imaging in the assessment of physeal growth arrest. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(9):1600-1608. doi:10.1007/s00330-004-2319-z.

24. Kang HG, Yoon SJ, Kim JR. Resection of a physeal bar under computer-assisted guidance. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(10):1452-1455. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.24587.

1. Murphy GA. Disorders of tendons and fascia and adolescent and adult pes planus. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 12th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby-Elsevier; 2013:3966-3972.

2. Khoshhal KI, Kiefer GN. Physeal bridge resection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(1):47-58. doi:10.5435/00124635-200501000-00007.

3. Stans AA. Excision of physeal bar. In: Wiesel SW, ed. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:1244-1249.

4. Loraas EK, Schmale GA. Endoscopically aided physeal bar takedown and guided growth for the treatment of angular limb deformity. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2012;21(4):348-351. doi:10.1097/BPB.0b013e328346d308.

5. Inoue T, Naito M, Fuhii T, Akiyoshi Y, Yoshimura I, Takamura K. Partial physeal growth arrest treated by bridge resection and artificial dura substitute interposition. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15(1):65-69. doi:10.1097/01202412-200601000-00014.

6. Arkader A, Warner WC Jr, Horn BD, Shaw RN, Wells L. Predicting the outcome of physeal fractures of the distal femur. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):703-708. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e3180dca0e5.

7. Langenskiöld A. Surgical treatment of partial closure of the growth plate. J Pediatr Orthop. 1981;1(1):3-11. doi:10.1097/01241398-198101010-00002.

8. Marsh JS, Polzhofer GK. Arthroscopically assisted central physeal bar resection. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(2):255-259. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000218533.43986.e1.

9. Williamson RV, Staheli LT. Partial physeal growth arrest: treatment by bridge resection and fat interposition. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10(6):769-776. doi:10.1097/01241398-199011000-00012.

10. Moreta J, Abril JC, Miranda C. Arthroscopy-assisted resection-interposition of post-traumatic central physeal bridges. Rev Esp Cir Orthop Traumatol. 2013;57(5):333-339. doi:10.1016/j.recot.2013.07.004.

11. Hasler CC, Foster BK. Secondary tethers after physeal bar resection: a common source of failure? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;405:242-249.

12. Paley D, Bhave A, Herzenberg JE, Bowen JR. Multiplier method for predicting limb-length discrepancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(10):1432-1446. doi:10.2106/00004623-200010000-00010.

13. Khoshhal KI, Kiefer GN. Physeal bridge resection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(1):47-58. doi:10.5435/00124635-200501000-00007.

14. Rathjen KE, Kim HKW. Physeal injuries and growth disturbances. In: Flynn JM, Skaggs DL, Waters PM, eds. Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children. 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters-Kluwer; 2015:135-137.

15. Peterson CA, Peterson HA. Analysis of the incidence of injuries to the epiphyseal growth plate. J Trauma. 1972;12(4):275-281. doi:10.1097/00005373-197204000-00002.

16. Pritchett JW. Longitudinal growth and growth-plate activity in the lower extremity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:274-279.

17. Cassebaum WH, Patterson AH. Fracture of the distal femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1965;41:79-91. doi:10.1097/00003086-196500410-00009.

18. Dahl WJ, Silva S, Vanderhave KL. Distal femoral physeal fixation: are smooth pins really safe? J Pedatir Orthop. 2014;34(2):134-138. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000083.

19. Roberts J. Fracture separation of the distal femoral epiphyseal growth line. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1324.

20. Broughton NS, Dickens DR, Cole WG, Menelaus MB. Epiphyseolysis for partial growth plate arrest. Results after four years or at maturity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(1):13-16. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.71B1.2914983.

21. Hresko MT, Kasser JR. Physeal arrest about the knee associated with non-physeal fractures in the lower extremity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(5):698-703. doi:10.2106/00004623-198971050-00009.

22. Lurie B, Koff MF, Shah P, et al. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of physeal injury: reliability and clinical utility. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34(3):239-245. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000104.

23. Sailhan F, Chotel F, Guibal AL, et al. Three-dimensional MR imaging in the assessment of physeal growth arrest. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(9):1600-1608. doi:10.1007/s00330-004-2319-z.

24. Kang HG, Yoon SJ, Kim JR. Resection of a physeal bar under computer-assisted guidance. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(10):1452-1455. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.92B10.24587.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Central physeal arrest of the distal femur is challenging, but this surgical technique provides an option for treatment.

- Partial bone bridges can be resected, but advanced imaging with MRI or CT, or both, is helpful in preoperative planning.

- Regardless of the type of physeal bar resection that is chosen, it is unlikely that complete, normal bone growth will be restored and closed follow up will be needed.

Thirty-second atrial fib threshold may drive overdiagnosis

BOSTON – The standard definition of an episode of atrial fibrillation is a fibrillation event that lasts at least 30 seconds, but a new analysis of monitoring data collected from 615 patients showed that this threshold can label many patients as having atrial fibrillation despite an extremely low disease burden.

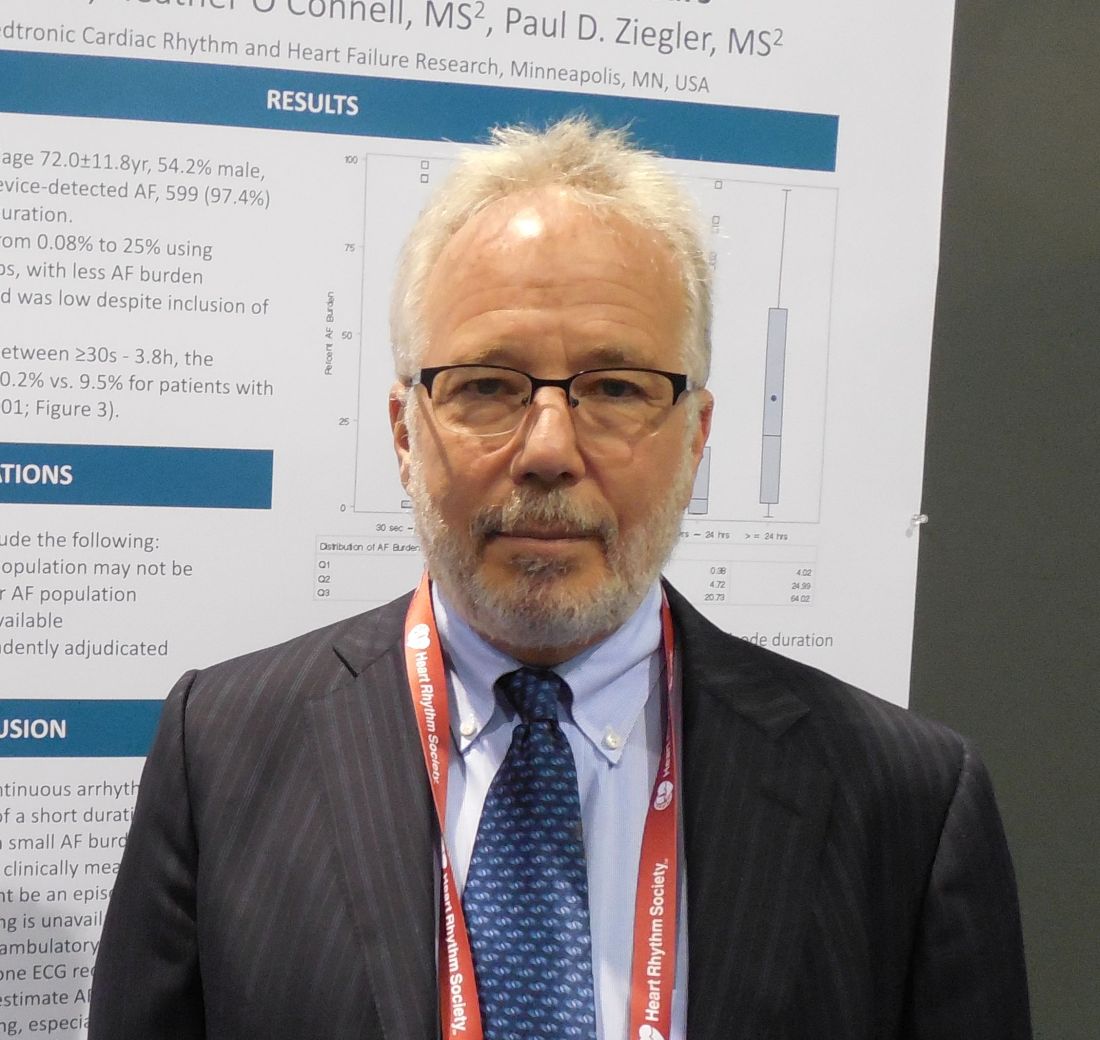

A more clinically relevant definition of atrial fibrillation (AF) might be a patient with at least one episode that persists for at least 3.8 hours, because this threshold identified people with a median AF burden of just under 10%, Jonathan S. Steinberg, MD, said while presenting a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

The 30-second threshold for defining an AF episode dates from the early days of atrial ablation treatment, when researchers tracked ablated patients for signs of AF recurrence. But this definition that clinicians devised for a very select subgroup of AF patients subsequently “metastasized” to define AF in all settings, he noted. As one recent example, the 2017 consensus document on screening for AF in asymptomatic people defined asymptomatic patients as having AF if they had at least one 30-second event picked up on an ECG recording (EP Europace. 2017 Oct 1;19[10]:1589-623).

“How we define AF is very important as we look for it in asymptomatic people,” Dr. Steinberg said in an interview.

A better definition of AF might depend on total AF burden, which is the percentage of time the patient’s atrium spends fibrillating. But it’s impossible to directly measure AF burden over a reasonably representative period of time without having an implanted device. If AF is monitored with an external device, the sampling time will be relatively brief, and so the AF assessment needs to rely on a surrogate for AF burden: the longest duration of any measured AF episode.

“No prior AF database has been analyzed like we have,” to correlate AF burden with the duration of the longest AF episode, Dr. Steinberg said.

He and his associates used data collected by Medtronic from 1,040 patients enrolled in a company registry during 2005-2016 with an implanted dual-chamber pacemaker able to detect atrial arrhythmias. The researchers focused on the 615 patients who had AF detected during at least 30 days of monitoring. These 615 patients averaged 72 years of age, 54% were men, and 599 had at least one AF episode of at least 30 seconds duration. Each patient had an average 3.7-year accumulated archive of atrial rhythm data.

The analysis showed a close association between the longest AF episode detected and overall AF burden. Among patients with a longest episode of 30-119 seconds, the median burden was 0.1%. Among patients with a maximum duration of anywhere from 30 seconds to 3.7 hours, the median burden was 0.2%. But among people with a longest episode of 3.8 hours to 5.4 hours, the median burden was 1.2%. In those with a longest episode of at least 24 hours, the median burden was 25%. Finally, in those who had a longest AF episode that lasted at least 3.8 hours, the median AF burden was 9.5%.

Dr. Steinberg acknowledged that a very important additional step needed in this analysis is examining the correlations among AF burden, longest AF episode, and stroke incidence, something he and his associates are now doing. He expressed hope that these data will spur the cardiac electrophysiology community to rethink its AF definition.

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Steinberg has been a consultant and/or has received research funding from Medtronic, AliveCor, Allergen, Atricure, Biosense Webster, G Medical, and National Cardiac. Several of his coauthors were Medtronic employees.

SOURCE: Steinberg J et al. Heart Rhythm Society scientific sessions, B-P001-062.

BOSTON – The standard definition of an episode of atrial fibrillation is a fibrillation event that lasts at least 30 seconds, but a new analysis of monitoring data collected from 615 patients showed that this threshold can label many patients as having atrial fibrillation despite an extremely low disease burden.

A more clinically relevant definition of atrial fibrillation (AF) might be a patient with at least one episode that persists for at least 3.8 hours, because this threshold identified people with a median AF burden of just under 10%, Jonathan S. Steinberg, MD, said while presenting a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

The 30-second threshold for defining an AF episode dates from the early days of atrial ablation treatment, when researchers tracked ablated patients for signs of AF recurrence. But this definition that clinicians devised for a very select subgroup of AF patients subsequently “metastasized” to define AF in all settings, he noted. As one recent example, the 2017 consensus document on screening for AF in asymptomatic people defined asymptomatic patients as having AF if they had at least one 30-second event picked up on an ECG recording (EP Europace. 2017 Oct 1;19[10]:1589-623).

“How we define AF is very important as we look for it in asymptomatic people,” Dr. Steinberg said in an interview.

A better definition of AF might depend on total AF burden, which is the percentage of time the patient’s atrium spends fibrillating. But it’s impossible to directly measure AF burden over a reasonably representative period of time without having an implanted device. If AF is monitored with an external device, the sampling time will be relatively brief, and so the AF assessment needs to rely on a surrogate for AF burden: the longest duration of any measured AF episode.

“No prior AF database has been analyzed like we have,” to correlate AF burden with the duration of the longest AF episode, Dr. Steinberg said.

He and his associates used data collected by Medtronic from 1,040 patients enrolled in a company registry during 2005-2016 with an implanted dual-chamber pacemaker able to detect atrial arrhythmias. The researchers focused on the 615 patients who had AF detected during at least 30 days of monitoring. These 615 patients averaged 72 years of age, 54% were men, and 599 had at least one AF episode of at least 30 seconds duration. Each patient had an average 3.7-year accumulated archive of atrial rhythm data.

The analysis showed a close association between the longest AF episode detected and overall AF burden. Among patients with a longest episode of 30-119 seconds, the median burden was 0.1%. Among patients with a maximum duration of anywhere from 30 seconds to 3.7 hours, the median burden was 0.2%. But among people with a longest episode of 3.8 hours to 5.4 hours, the median burden was 1.2%. In those with a longest episode of at least 24 hours, the median burden was 25%. Finally, in those who had a longest AF episode that lasted at least 3.8 hours, the median AF burden was 9.5%.

Dr. Steinberg acknowledged that a very important additional step needed in this analysis is examining the correlations among AF burden, longest AF episode, and stroke incidence, something he and his associates are now doing. He expressed hope that these data will spur the cardiac electrophysiology community to rethink its AF definition.

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Steinberg has been a consultant and/or has received research funding from Medtronic, AliveCor, Allergen, Atricure, Biosense Webster, G Medical, and National Cardiac. Several of his coauthors were Medtronic employees.

SOURCE: Steinberg J et al. Heart Rhythm Society scientific sessions, B-P001-062.

BOSTON – The standard definition of an episode of atrial fibrillation is a fibrillation event that lasts at least 30 seconds, but a new analysis of monitoring data collected from 615 patients showed that this threshold can label many patients as having atrial fibrillation despite an extremely low disease burden.

A more clinically relevant definition of atrial fibrillation (AF) might be a patient with at least one episode that persists for at least 3.8 hours, because this threshold identified people with a median AF burden of just under 10%, Jonathan S. Steinberg, MD, said while presenting a poster at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

The 30-second threshold for defining an AF episode dates from the early days of atrial ablation treatment, when researchers tracked ablated patients for signs of AF recurrence. But this definition that clinicians devised for a very select subgroup of AF patients subsequently “metastasized” to define AF in all settings, he noted. As one recent example, the 2017 consensus document on screening for AF in asymptomatic people defined asymptomatic patients as having AF if they had at least one 30-second event picked up on an ECG recording (EP Europace. 2017 Oct 1;19[10]:1589-623).

“How we define AF is very important as we look for it in asymptomatic people,” Dr. Steinberg said in an interview.

A better definition of AF might depend on total AF burden, which is the percentage of time the patient’s atrium spends fibrillating. But it’s impossible to directly measure AF burden over a reasonably representative period of time without having an implanted device. If AF is monitored with an external device, the sampling time will be relatively brief, and so the AF assessment needs to rely on a surrogate for AF burden: the longest duration of any measured AF episode.

“No prior AF database has been analyzed like we have,” to correlate AF burden with the duration of the longest AF episode, Dr. Steinberg said.

He and his associates used data collected by Medtronic from 1,040 patients enrolled in a company registry during 2005-2016 with an implanted dual-chamber pacemaker able to detect atrial arrhythmias. The researchers focused on the 615 patients who had AF detected during at least 30 days of monitoring. These 615 patients averaged 72 years of age, 54% were men, and 599 had at least one AF episode of at least 30 seconds duration. Each patient had an average 3.7-year accumulated archive of atrial rhythm data.

The analysis showed a close association between the longest AF episode detected and overall AF burden. Among patients with a longest episode of 30-119 seconds, the median burden was 0.1%. Among patients with a maximum duration of anywhere from 30 seconds to 3.7 hours, the median burden was 0.2%. But among people with a longest episode of 3.8 hours to 5.4 hours, the median burden was 1.2%. In those with a longest episode of at least 24 hours, the median burden was 25%. Finally, in those who had a longest AF episode that lasted at least 3.8 hours, the median AF burden was 9.5%.

Dr. Steinberg acknowledged that a very important additional step needed in this analysis is examining the correlations among AF burden, longest AF episode, and stroke incidence, something he and his associates are now doing. He expressed hope that these data will spur the cardiac electrophysiology community to rethink its AF definition.

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Steinberg has been a consultant and/or has received research funding from Medtronic, AliveCor, Allergen, Atricure, Biosense Webster, G Medical, and National Cardiac. Several of his coauthors were Medtronic employees.

SOURCE: Steinberg J et al. Heart Rhythm Society scientific sessions, B-P001-062.

REPORTING FROM HEART RHYTHM 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The median atrial fibrillation burden was 0.1% when the longest AF episode was 30-119 seconds.

Study details: Review of data from 615 patients with AF events in a Medtronic registry.

Disclosures: Medtronic funded the study. Dr. Steinberg has been a consultant and/or has received research funding from Medtronic, AliveCor, Allergen, Atricure, Biosense Webster, G Medical, and National Cardiac. Several of his coauthors were Medtronic employees.

Source: Steinberg J et al. Heart Rhythm Society scientific sessions B-P001-062.

MDedge Daily News: Prostate screening should be by request

Zika topped Lyme in 2016

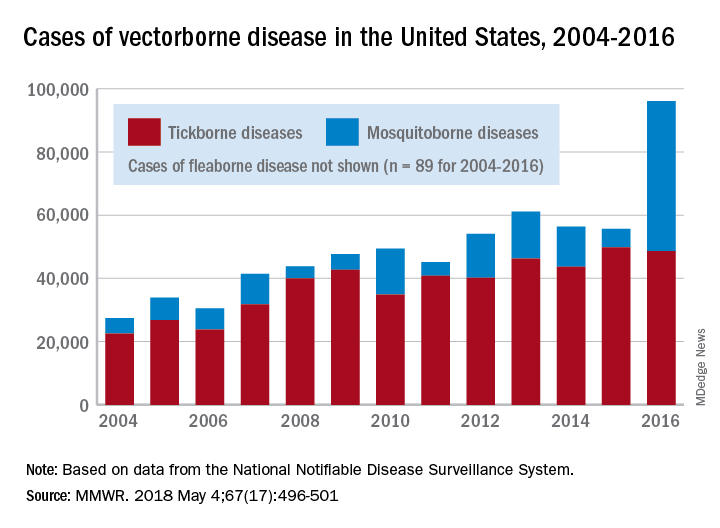

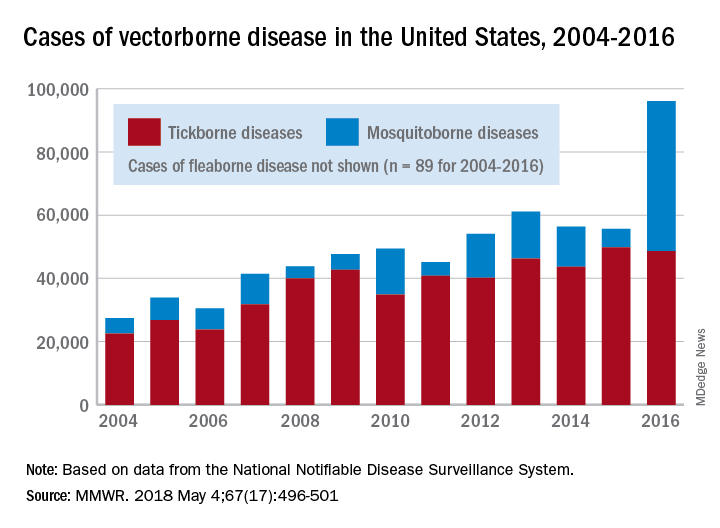

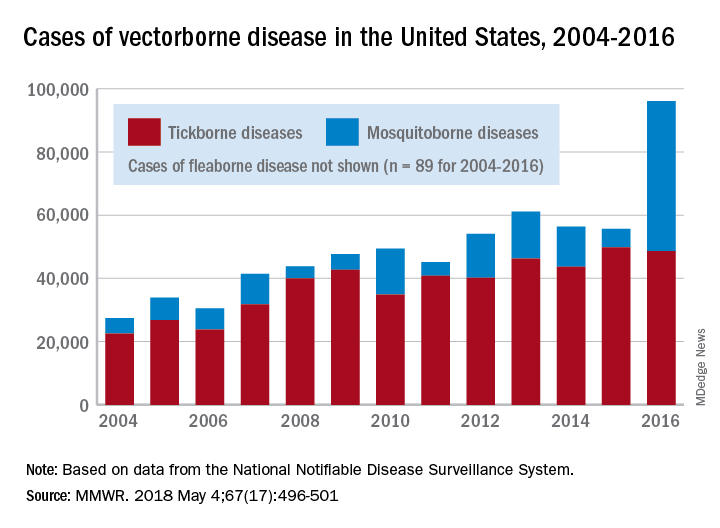

Ticks are the arthropod ride of choice for vector-borne diseases in the United States, but the Zika virus and its mosquito minions gave the ticks and their bacterial passengers a run for their money in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 41,680 cases of Zika virus that year, more than any other vector-borne disease, including Lyme disease, which had been the most common transmissible pathogen going back to at least 2004, when arthropod-borne viral diseases became nationally notifiable, said Ronald Rosenberg, ScD, and his associates at the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases in Fort Collins, Colo.

Since 2004, there have been 643,000 reported cases of vector-borne disease in the United States: 492,000 cases of tick-borne disease, of which over 402,000 were Lyme disease; 151,000 cases of mosquito-borne disease; and 89 cases of plague carried by the third type of vector, fleas, Dr. Rosenberg and his associates said based on data from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

In 2004, there were 22,527 cases of tick-borne disease and 4,858 cases of mosquito-borne disease, and the increases since then reflect the dynamics of the pathogens and vectors involved. Growth of tick-borne disease has been gradual: “Tick-borne pathogens rarely cause sudden epidemics because humans are typically incidental hosts who do not transmit further, and tick mobility is mostly limited to that of its animal hosts,” the researchers explained.

The number of mosquito-borne disease cases, on the other hand, varies considerably from year to year: There were 5,800 cases in 2015, almost 15,000 in 2013, and only 4,400 in 2011. Unlike ticks, which may feed on blood only once in a year, the more mobile mosquitoes feed every 48-72 hours and transmit their pathogens “directly between humans … resulting in explosive epidemics,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Rosenberg R et al. MMWR 2018 May 4;67(17):496-501.

Ticks are the arthropod ride of choice for vector-borne diseases in the United States, but the Zika virus and its mosquito minions gave the ticks and their bacterial passengers a run for their money in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 41,680 cases of Zika virus that year, more than any other vector-borne disease, including Lyme disease, which had been the most common transmissible pathogen going back to at least 2004, when arthropod-borne viral diseases became nationally notifiable, said Ronald Rosenberg, ScD, and his associates at the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases in Fort Collins, Colo.

Since 2004, there have been 643,000 reported cases of vector-borne disease in the United States: 492,000 cases of tick-borne disease, of which over 402,000 were Lyme disease; 151,000 cases of mosquito-borne disease; and 89 cases of plague carried by the third type of vector, fleas, Dr. Rosenberg and his associates said based on data from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

In 2004, there were 22,527 cases of tick-borne disease and 4,858 cases of mosquito-borne disease, and the increases since then reflect the dynamics of the pathogens and vectors involved. Growth of tick-borne disease has been gradual: “Tick-borne pathogens rarely cause sudden epidemics because humans are typically incidental hosts who do not transmit further, and tick mobility is mostly limited to that of its animal hosts,” the researchers explained.

The number of mosquito-borne disease cases, on the other hand, varies considerably from year to year: There were 5,800 cases in 2015, almost 15,000 in 2013, and only 4,400 in 2011. Unlike ticks, which may feed on blood only once in a year, the more mobile mosquitoes feed every 48-72 hours and transmit their pathogens “directly between humans … resulting in explosive epidemics,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Rosenberg R et al. MMWR 2018 May 4;67(17):496-501.

Ticks are the arthropod ride of choice for vector-borne diseases in the United States, but the Zika virus and its mosquito minions gave the ticks and their bacterial passengers a run for their money in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were 41,680 cases of Zika virus that year, more than any other vector-borne disease, including Lyme disease, which had been the most common transmissible pathogen going back to at least 2004, when arthropod-borne viral diseases became nationally notifiable, said Ronald Rosenberg, ScD, and his associates at the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases in Fort Collins, Colo.

Since 2004, there have been 643,000 reported cases of vector-borne disease in the United States: 492,000 cases of tick-borne disease, of which over 402,000 were Lyme disease; 151,000 cases of mosquito-borne disease; and 89 cases of plague carried by the third type of vector, fleas, Dr. Rosenberg and his associates said based on data from the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

In 2004, there were 22,527 cases of tick-borne disease and 4,858 cases of mosquito-borne disease, and the increases since then reflect the dynamics of the pathogens and vectors involved. Growth of tick-borne disease has been gradual: “Tick-borne pathogens rarely cause sudden epidemics because humans are typically incidental hosts who do not transmit further, and tick mobility is mostly limited to that of its animal hosts,” the researchers explained.

The number of mosquito-borne disease cases, on the other hand, varies considerably from year to year: There were 5,800 cases in 2015, almost 15,000 in 2013, and only 4,400 in 2011. Unlike ticks, which may feed on blood only once in a year, the more mobile mosquitoes feed every 48-72 hours and transmit their pathogens “directly between humans … resulting in explosive epidemics,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Rosenberg R et al. MMWR 2018 May 4;67(17):496-501.

FROM MMWR

Sorafenib Improves Survival for Patients With Rare Sarcomas

Promising results from a phase 3 trial could represent a paradigm shift in treatment of patients with desmoid tumors, say National Cancer Institute (NCI) researchers. Sorafenib tosylate extended progression-free survival (PFS) compared with that of placebo in 87 patients with desmoid tumors or aggressive fibromatosis (DT/DF).

Desmoid tumors or aggressive fibromatosis are rare sarcomas, usually found in the extremities or the abdomen and occasionally associated with familial adenomatous polyposis or Gardner syndrome. Effectiveness of current treatments—surgery, radiation, chemotherapy—is generally limited, says Jeff Abrams, MD, clinical director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis.

Sorafenib is a targeted treatment that interferes with the growth of cancer cells and new blood vessels that feed the tumors. It is approved for some patients with advanced kidney, liver, and thyroid cancers. It was chosen for the NCI trial because in earlier studies DT shrank in patients on sorafenib, and patients had fewer symptoms, including less pain.

Patients were assigned to receive sorafenib 400 mg/d or placebo. The trial was designed to assess improvement in PFS from 6 months for placebo to 15 months for sorafenib. Based on an interim analysis of the first 75 patients enrolled, the observed improvement in PFS exceeded the target. Patients on sorafenib were more likely to experience drug-related adverse effects, but those were generally not severe.

Treatment assignments have been disclosed to patients still receiving treatment and their physicians. Those who were receiving sorafenib can continue therapy, and those on placebo can switch to sorafenib.

Promising results from a phase 3 trial could represent a paradigm shift in treatment of patients with desmoid tumors, say National Cancer Institute (NCI) researchers. Sorafenib tosylate extended progression-free survival (PFS) compared with that of placebo in 87 patients with desmoid tumors or aggressive fibromatosis (DT/DF).

Desmoid tumors or aggressive fibromatosis are rare sarcomas, usually found in the extremities or the abdomen and occasionally associated with familial adenomatous polyposis or Gardner syndrome. Effectiveness of current treatments—surgery, radiation, chemotherapy—is generally limited, says Jeff Abrams, MD, clinical director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis.

Sorafenib is a targeted treatment that interferes with the growth of cancer cells and new blood vessels that feed the tumors. It is approved for some patients with advanced kidney, liver, and thyroid cancers. It was chosen for the NCI trial because in earlier studies DT shrank in patients on sorafenib, and patients had fewer symptoms, including less pain.

Patients were assigned to receive sorafenib 400 mg/d or placebo. The trial was designed to assess improvement in PFS from 6 months for placebo to 15 months for sorafenib. Based on an interim analysis of the first 75 patients enrolled, the observed improvement in PFS exceeded the target. Patients on sorafenib were more likely to experience drug-related adverse effects, but those were generally not severe.

Treatment assignments have been disclosed to patients still receiving treatment and their physicians. Those who were receiving sorafenib can continue therapy, and those on placebo can switch to sorafenib.

Promising results from a phase 3 trial could represent a paradigm shift in treatment of patients with desmoid tumors, say National Cancer Institute (NCI) researchers. Sorafenib tosylate extended progression-free survival (PFS) compared with that of placebo in 87 patients with desmoid tumors or aggressive fibromatosis (DT/DF).

Desmoid tumors or aggressive fibromatosis are rare sarcomas, usually found in the extremities or the abdomen and occasionally associated with familial adenomatous polyposis or Gardner syndrome. Effectiveness of current treatments—surgery, radiation, chemotherapy—is generally limited, says Jeff Abrams, MD, clinical director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis.

Sorafenib is a targeted treatment that interferes with the growth of cancer cells and new blood vessels that feed the tumors. It is approved for some patients with advanced kidney, liver, and thyroid cancers. It was chosen for the NCI trial because in earlier studies DT shrank in patients on sorafenib, and patients had fewer symptoms, including less pain.

Patients were assigned to receive sorafenib 400 mg/d or placebo. The trial was designed to assess improvement in PFS from 6 months for placebo to 15 months for sorafenib. Based on an interim analysis of the first 75 patients enrolled, the observed improvement in PFS exceeded the target. Patients on sorafenib were more likely to experience drug-related adverse effects, but those were generally not severe.

Treatment assignments have been disclosed to patients still receiving treatment and their physicians. Those who were receiving sorafenib can continue therapy, and those on placebo can switch to sorafenib.

Restrictive fluids tied to kidney injury after major abdominal surgery

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

Effective blinding was impossible in this randomized study, wrote Birgitte Brandstrup, PhD, in an accompanying editorial. Differences in fluid volume cause symptoms that clinicians can easily identify, she noted.

She recalled the 1990s, when “surgical patients received so much intravenous saline on the day of surgery that they often gained 4 to 6 kg, and by postoperative day 2 or 3, [and] pulmonary congestion and cardiac arrhythmias were commonplace.” Subsequent trials changed this practice, and patients in the current study received much less fluid than they would have in the old days, she noted.

Nonetheless, the findings indicate “that physiologic principles remain valid: Both hypovolemia and oliguria must be recognized and treated with fluid.” While that does not justify excessive perioperative fluid therapy, “a modestly liberal fluid regimen is safer than a truly restrictive regimen.”

Dr. Brandstrup is with the department of surgery at Holbaek (Denmark) Hospital. She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. These comments recap her editorial (New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1805615).

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and led to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury, researchers reported.

In an international, randomized trial with 366 median days of follow-up, estimated 1-year rates of disability-free survival were 81.9% with the restrictive intravenous fluid regimen and 82.3% with the liberal regimen (hazard ratio for death or disability, 1.05; P = .61), according to Paul S. Myles, MPH, DSc, and his associates.

Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% in the restrictive IV fluid group and 5.0% with the liberal fluid therapy (P less than .001), the researchers reported online May 10 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Guidelines recommend a restrictive intravenous fluid strategy to promote early recovery after major abdominal surgery, noted Dr. Myles of Alfred Hospital in Melbourne and his colleagues. “However, the supporting evidence is limited, and there is concern about impaired organ perfusion.”

Therefore, they randomly assigned, 3,000 patients to receive either the restrictive fluid regimen or a liberal regimen during major abdominal surgery and up to 24 hours after. Median intravenous volume was 3.7 L (interquartile range, 2.9-4.9 L) in the restrictive group and 6.1 L (IQR, 5.0-7.4 L) in the liberal fluid group. All patients were deemed high risk based on their age (at least 70 years) or because they had heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, or morbid obesity.

Patients who received the restrictive regimen had higher rates of surgical site infection (16.5% vs. 13.6% with liberal fluids; P = .02) and were more likely to receive renal replacement therapy (0.9% vs. 0.3%; P = .048). However, these trends were no longer significant after the researchers controlled for the effects of testing for multiple variables.

“Our findings should not be used to support excessive administration of intravenous fluid,” the researchers cautioned. “Rather, they show that a regimen that includes a modestly liberal administration of fluid is safer than a restrictive regimen.”

Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Compared with a liberal fluid regimen, restricting fluids did not improve disability-free survival and was tied to a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury among high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Major finding: Rates of acute renal injury were 8.6% with restrictive fluids and 5.0% with liberal fluids.

Study details: International randomized trial of 3,000 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Disclosures: Funders included the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, and Monash University, Melbourne. Dr. Myles reported receiving grant support from NHMRC. He had no other disclosures.

Source: Myles PS et al. New Engl J Med. 2018 May 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801601

Team identifies new prognostic factor for MF

New research suggests DNA sequencing can reveal which patients with early stage mycosis fungoides (MF) will develop aggressive disease.

By sequencing the T-cell receptor beta gene (TCRB) in skin biopsies from MF patients, investigators were able to measure the tumor clone frequency (TCF), or the percentage of all T cells that represent the MF clone.

The researchers found the TCF could predict progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

In fact, for patients with early stage MF, TCF was a stronger predictor of PFS than other established prognostic factors.

“While more work needs to be done, we think this approach has the potential to prospectively identify a subgroup of patients who are destined to develop aggressive, life-threatening disease and treat them in a more aggressive fashion with the intent to better manage and, ideally, cure their cancer,” said Thomas Kupper, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“At the same time, we believe we can provide reassurance to patients with a low-risk (low TCF) profile that they are likely to survive indefinitely with conventional conservative therapies. As a physician who has treated this disease for decades, I am excited to be involved with work that so directly and profoundly affects the care and management of these patients.”

Dr Kupper and his colleagues described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers had previously published a study showing that high-throughput sequencing of the TCRB gene was an accurate way to diagnose cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), including MF.

With the current study, the investigators set out to determine if the method could be used to predict progression and survival in patients with CTCL.

The team sequenced TCRB in lesional skin biopsies from 309 CTCL patients, most of whom had MF. The discovery cohort had 208 patients (177 with MF), and the validation cohort had 101 patients (87 with MF).

The sequencing produced a snapshot of the TCRB genes from a large number of cells at the site of the lesion. And the researchers could use this to measure TCF.

The team tested the association of TCF with prognosis in all CTCL patients in the discovery cohort and found a TCF greater than 25% in the skin was significantly associated with reduced PFS (P<0.001) and OS (P<0.001). Results were similar in the validation cohort (P<0.001 for PFS and OS).

The investigators also found that TCF was significantly associated with PFS (P<0.001) and OS (P<0.001) in MF patients but not in patients with Sézary syndrome. The team noted that they did not assess the predictive value of TCF in the blood of Sézary patients.

In a multivariable analysis, TCF was still significantly associated with PFS (P<0.001) and OS (P<0.001) in the MF patients.

The researchers also assessed potential prognostic variables in the early stage MF patients and found a TCF greater than 25% was a stronger predictor of PFS than any other established prognostic factor. This includes disease stage, presence of plaques, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, age, large-cell transformation, and CLIPI score.

“In reviewing the results, 2 different patients could have identical-looking skin lesions, but one might have a TCF of 8%, and one would have a TCF of 40%,” Dr Kupper noted. “The latter patient was highly likely to progress—something we would never have been able to predict before this discovery.”

“The TCF was independent of how thick or thin the skin lesions were. Most importantly, compared to all other currently used means of trying to predict which patients would progress, TCF was by far the most sensitive and specific.”

The high-throughput sequencing in this study was performed using ImmunoSEQ, an assay developed by Adaptive Biotechnologies. The company did not sponsor the study, but company employees were involved in the research.

New research suggests DNA sequencing can reveal which patients with early stage mycosis fungoides (MF) will develop aggressive disease.

By sequencing the T-cell receptor beta gene (TCRB) in skin biopsies from MF patients, investigators were able to measure the tumor clone frequency (TCF), or the percentage of all T cells that represent the MF clone.