User login

Patient resources from SFA

The Sarcoma Foundation of America offers patient resources that explain what sarcoma is, the various subtypes, how sarcomas are diagnosed, and treatment options. Information is available online at https://www.curesarcoma.org/patient-resources/

The Sarcoma Foundation of America offers patient resources that explain what sarcoma is, the various subtypes, how sarcomas are diagnosed, and treatment options. Information is available online at https://www.curesarcoma.org/patient-resources/

The Sarcoma Foundation of America offers patient resources that explain what sarcoma is, the various subtypes, how sarcomas are diagnosed, and treatment options. Information is available online at https://www.curesarcoma.org/patient-resources/

Apply for a Grant

The Sarcoma Foundation of America has developed a program to provide grants to investigators interested in translational science sarcoma research. Funding of up to $50,000, allowing up to 10 percent indirect costs, is available to cover equipment and supplies in support of research on the etiology, molecular biology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of human sarcomas.

In accordance with the mission of the Foundation, research involving the development of novel agents against sarcoma, or research that could potentially lead to the development of novel agents against sarcoma, is eligible for this funding.

Please refer to SFA's Grants FAQ for additional information.

Researchers must submit proposals electronically at proposalCENTRAL. First-time users will be required to register and complete a professional profile in order to apply for an SFA research grant. The SFA does not accept applications via e-mail.

For more information, visit the SFA website at https://www.curesarcoma.org/research/apply-for-a-grant/

The Sarcoma Foundation of America has developed a program to provide grants to investigators interested in translational science sarcoma research. Funding of up to $50,000, allowing up to 10 percent indirect costs, is available to cover equipment and supplies in support of research on the etiology, molecular biology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of human sarcomas.

In accordance with the mission of the Foundation, research involving the development of novel agents against sarcoma, or research that could potentially lead to the development of novel agents against sarcoma, is eligible for this funding.

Please refer to SFA's Grants FAQ for additional information.

Researchers must submit proposals electronically at proposalCENTRAL. First-time users will be required to register and complete a professional profile in order to apply for an SFA research grant. The SFA does not accept applications via e-mail.

For more information, visit the SFA website at https://www.curesarcoma.org/research/apply-for-a-grant/

The Sarcoma Foundation of America has developed a program to provide grants to investigators interested in translational science sarcoma research. Funding of up to $50,000, allowing up to 10 percent indirect costs, is available to cover equipment and supplies in support of research on the etiology, molecular biology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of human sarcomas.

In accordance with the mission of the Foundation, research involving the development of novel agents against sarcoma, or research that could potentially lead to the development of novel agents against sarcoma, is eligible for this funding.

Please refer to SFA's Grants FAQ for additional information.

Researchers must submit proposals electronically at proposalCENTRAL. First-time users will be required to register and complete a professional profile in order to apply for an SFA research grant. The SFA does not accept applications via e-mail.

For more information, visit the SFA website at https://www.curesarcoma.org/research/apply-for-a-grant/

The Sarcoma Foundation of America: Funding research, advocating for patients

The Sarcoma Foundation of America is a national organization dedicated to increasing sarcoma awareness and research. Through its advocacy and fundraising efforts, the foundation has supported 115 sarcoma research grants since 2003, along with two large American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Foundation Clinical Research grants worth $450,000. The SFA has also funded six ASCO Young Investigator Awards and has started a large research based initiative called the Sarcoma Patient Registry, designed to increase research performed on sarcoma and to facilitate clinical trials.

To learn more about the Sarcoma Foundation of America, visit their website.

The Sarcoma Foundation of America is a national organization dedicated to increasing sarcoma awareness and research. Through its advocacy and fundraising efforts, the foundation has supported 115 sarcoma research grants since 2003, along with two large American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Foundation Clinical Research grants worth $450,000. The SFA has also funded six ASCO Young Investigator Awards and has started a large research based initiative called the Sarcoma Patient Registry, designed to increase research performed on sarcoma and to facilitate clinical trials.

To learn more about the Sarcoma Foundation of America, visit their website.

The Sarcoma Foundation of America is a national organization dedicated to increasing sarcoma awareness and research. Through its advocacy and fundraising efforts, the foundation has supported 115 sarcoma research grants since 2003, along with two large American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Foundation Clinical Research grants worth $450,000. The SFA has also funded six ASCO Young Investigator Awards and has started a large research based initiative called the Sarcoma Patient Registry, designed to increase research performed on sarcoma and to facilitate clinical trials.

To learn more about the Sarcoma Foundation of America, visit their website.

Absurdity

Absurdity is everywhere you look. Or don’t look.

As the old comedian Henny Youngman might have said:

Take my prior authorizations. Please!

Prior authorizations

1. Marissa had been taking isotretinoin for 2 months. She learned that three 20-mg capsules would cost her less than the two 30-mg capsules she’d been on.

My secretary called them. The insurance representative (Pharmacist? Clerk? Gal who stopped by to read the gas meter?) couldn’t help. “When I input your information, it issues a denial.” (Who is “it”? Watson’s evil twin Jensen?)

I got on the phone.

“Forgive me,” I said, gently, “but Marissa has been taking isotretinoin for 2 months, 60-mg per day. She was taking two 30’s. I want her to have three 20’s. They both add up to 60 mg. It’s the same dose. Why do you need to authorize it again?”

“Let me input that,” she replied. “Oh, now it’s accepting it. Your patient can have up to four pills a day.”

I was going to say she only needs three, but kept my mouth shut. Maybe Jensen only authorizes even numbers. 2. Danny has the worst atopic dermatitis I’ve ever seen. It’s all over him and never lets up. Topical steroids don’t touch it. Even prednisone – he’s had plenty over the years – barely makes a dent. I put in a Prior Authorization request for dupilumab.

“Your request for dupilumab has been denied,” read the insurer’s reply. “You have not shown failure with tacrolimus ointment or crisaborole.”

Say what? Prednisone didn’t help, and they expect tacrolimus or crisaborole to do the job?

I prescribed tacrolimus (which doesn’t come in a big enough tube to cover Daniel’s affected area anyway). It failed. Amazing.

“Your request for dupilumab has been denied,” said the insurer. “You have not also shown failure with crisaborole.”

Really? OK, I prescribed crisaborole. They denied coverage for it.

Now I was really getting into this. I wrote them. “I prescribed crisaborole.” I observed, “because you asked me to.”

They approved crisaborole. It failed. I reapplied for dupilumab. No response.

I called the insurer’s medical director, on a mobile with a Missouri exchange. After some telephone tag, he called back. “I cannot discuss this case with you,” he said, “because I have already made my determination.” Then he hung up without telling me what his determination was.

Further phone calls went unanswered. I thought Missouri was the Show-Me state.

The patient remained miserable. I decided to try one last time and wrote a long, sarcastic letter, detailing the whole episode. My secretary sent it off.

They approved dupilumab within the hour.

Malice? Nah, that’s giving them too much credit.

Now all Daniel has to do is improve.

Patient privacy!

Some news from abroad: what we know as HIPAA is called the “Data Protection Act” in the United Kingdom.

“We are obliged to conform to the demands of the Data Protection Act, and this specifically applies to the rabbi publicly mentioning the names of individuals who are unwell. The rabbi can only mention specific individuals with their permission or that of a relative designated by the sick person to do so. Anyone wishing for the rabbi to say a public prayer on their behalf must contact him directly by phone, text, or e-mail. To do anything else is breaking the law.”

If someone breaks this law, perhaps the rabbi can assist with atonement.

In any event, henceforth all entreaties to the Almighty must be encrypted. At least in the U.K.

What???!!!

Marina showed me her sunscreen. The label read, “Protects against UVA and UVB rays.”

“What’s the problem?” I asked.

She showed me our American Academy of Dermatology-produced sunscreen handout, which recommends “a broad-spectrum sunscreen that protects against both UVA and UVB rays, both of which cause cancer.”

“Does this mean my sunscreen causes cancer?” asked Marina.

“Not to worry,” I assured her.

I sighed and wafted a small prayer heavenward. Encrypted, of course.

Lo, the answer from above may tarry, but He will never forget His password.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Absurdity is everywhere you look. Or don’t look.

As the old comedian Henny Youngman might have said:

Take my prior authorizations. Please!

Prior authorizations

1. Marissa had been taking isotretinoin for 2 months. She learned that three 20-mg capsules would cost her less than the two 30-mg capsules she’d been on.

My secretary called them. The insurance representative (Pharmacist? Clerk? Gal who stopped by to read the gas meter?) couldn’t help. “When I input your information, it issues a denial.” (Who is “it”? Watson’s evil twin Jensen?)

I got on the phone.

“Forgive me,” I said, gently, “but Marissa has been taking isotretinoin for 2 months, 60-mg per day. She was taking two 30’s. I want her to have three 20’s. They both add up to 60 mg. It’s the same dose. Why do you need to authorize it again?”

“Let me input that,” she replied. “Oh, now it’s accepting it. Your patient can have up to four pills a day.”

I was going to say she only needs three, but kept my mouth shut. Maybe Jensen only authorizes even numbers. 2. Danny has the worst atopic dermatitis I’ve ever seen. It’s all over him and never lets up. Topical steroids don’t touch it. Even prednisone – he’s had plenty over the years – barely makes a dent. I put in a Prior Authorization request for dupilumab.

“Your request for dupilumab has been denied,” read the insurer’s reply. “You have not shown failure with tacrolimus ointment or crisaborole.”

Say what? Prednisone didn’t help, and they expect tacrolimus or crisaborole to do the job?

I prescribed tacrolimus (which doesn’t come in a big enough tube to cover Daniel’s affected area anyway). It failed. Amazing.

“Your request for dupilumab has been denied,” said the insurer. “You have not also shown failure with crisaborole.”

Really? OK, I prescribed crisaborole. They denied coverage for it.

Now I was really getting into this. I wrote them. “I prescribed crisaborole.” I observed, “because you asked me to.”

They approved crisaborole. It failed. I reapplied for dupilumab. No response.

I called the insurer’s medical director, on a mobile with a Missouri exchange. After some telephone tag, he called back. “I cannot discuss this case with you,” he said, “because I have already made my determination.” Then he hung up without telling me what his determination was.

Further phone calls went unanswered. I thought Missouri was the Show-Me state.

The patient remained miserable. I decided to try one last time and wrote a long, sarcastic letter, detailing the whole episode. My secretary sent it off.

They approved dupilumab within the hour.

Malice? Nah, that’s giving them too much credit.

Now all Daniel has to do is improve.

Patient privacy!

Some news from abroad: what we know as HIPAA is called the “Data Protection Act” in the United Kingdom.

“We are obliged to conform to the demands of the Data Protection Act, and this specifically applies to the rabbi publicly mentioning the names of individuals who are unwell. The rabbi can only mention specific individuals with their permission or that of a relative designated by the sick person to do so. Anyone wishing for the rabbi to say a public prayer on their behalf must contact him directly by phone, text, or e-mail. To do anything else is breaking the law.”

If someone breaks this law, perhaps the rabbi can assist with atonement.

In any event, henceforth all entreaties to the Almighty must be encrypted. At least in the U.K.

What???!!!

Marina showed me her sunscreen. The label read, “Protects against UVA and UVB rays.”

“What’s the problem?” I asked.

She showed me our American Academy of Dermatology-produced sunscreen handout, which recommends “a broad-spectrum sunscreen that protects against both UVA and UVB rays, both of which cause cancer.”

“Does this mean my sunscreen causes cancer?” asked Marina.

“Not to worry,” I assured her.

I sighed and wafted a small prayer heavenward. Encrypted, of course.

Lo, the answer from above may tarry, but He will never forget His password.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Absurdity is everywhere you look. Or don’t look.

As the old comedian Henny Youngman might have said:

Take my prior authorizations. Please!

Prior authorizations

1. Marissa had been taking isotretinoin for 2 months. She learned that three 20-mg capsules would cost her less than the two 30-mg capsules she’d been on.

My secretary called them. The insurance representative (Pharmacist? Clerk? Gal who stopped by to read the gas meter?) couldn’t help. “When I input your information, it issues a denial.” (Who is “it”? Watson’s evil twin Jensen?)

I got on the phone.

“Forgive me,” I said, gently, “but Marissa has been taking isotretinoin for 2 months, 60-mg per day. She was taking two 30’s. I want her to have three 20’s. They both add up to 60 mg. It’s the same dose. Why do you need to authorize it again?”

“Let me input that,” she replied. “Oh, now it’s accepting it. Your patient can have up to four pills a day.”

I was going to say she only needs three, but kept my mouth shut. Maybe Jensen only authorizes even numbers. 2. Danny has the worst atopic dermatitis I’ve ever seen. It’s all over him and never lets up. Topical steroids don’t touch it. Even prednisone – he’s had plenty over the years – barely makes a dent. I put in a Prior Authorization request for dupilumab.

“Your request for dupilumab has been denied,” read the insurer’s reply. “You have not shown failure with tacrolimus ointment or crisaborole.”

Say what? Prednisone didn’t help, and they expect tacrolimus or crisaborole to do the job?

I prescribed tacrolimus (which doesn’t come in a big enough tube to cover Daniel’s affected area anyway). It failed. Amazing.

“Your request for dupilumab has been denied,” said the insurer. “You have not also shown failure with crisaborole.”

Really? OK, I prescribed crisaborole. They denied coverage for it.

Now I was really getting into this. I wrote them. “I prescribed crisaborole.” I observed, “because you asked me to.”

They approved crisaborole. It failed. I reapplied for dupilumab. No response.

I called the insurer’s medical director, on a mobile with a Missouri exchange. After some telephone tag, he called back. “I cannot discuss this case with you,” he said, “because I have already made my determination.” Then he hung up without telling me what his determination was.

Further phone calls went unanswered. I thought Missouri was the Show-Me state.

The patient remained miserable. I decided to try one last time and wrote a long, sarcastic letter, detailing the whole episode. My secretary sent it off.

They approved dupilumab within the hour.

Malice? Nah, that’s giving them too much credit.

Now all Daniel has to do is improve.

Patient privacy!

Some news from abroad: what we know as HIPAA is called the “Data Protection Act” in the United Kingdom.

“We are obliged to conform to the demands of the Data Protection Act, and this specifically applies to the rabbi publicly mentioning the names of individuals who are unwell. The rabbi can only mention specific individuals with their permission or that of a relative designated by the sick person to do so. Anyone wishing for the rabbi to say a public prayer on their behalf must contact him directly by phone, text, or e-mail. To do anything else is breaking the law.”

If someone breaks this law, perhaps the rabbi can assist with atonement.

In any event, henceforth all entreaties to the Almighty must be encrypted. At least in the U.K.

What???!!!

Marina showed me her sunscreen. The label read, “Protects against UVA and UVB rays.”

“What’s the problem?” I asked.

She showed me our American Academy of Dermatology-produced sunscreen handout, which recommends “a broad-spectrum sunscreen that protects against both UVA and UVB rays, both of which cause cancer.”

“Does this mean my sunscreen causes cancer?” asked Marina.

“Not to worry,” I assured her.

I sighed and wafted a small prayer heavenward. Encrypted, of course.

Lo, the answer from above may tarry, but He will never forget His password.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His second book, “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient,” is available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

ALUR: Alectinib topped chemo in pretreated ALK-positive NSCLC

The second-generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor alectinib (Alcensa) topped chemotherapy in crizotinib-pretreated ALK+ non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), according to results from the phase 3 ALUR trial.

Median investigator-assessed progression-free survival was 9.6 months with alectinib and 1.4 months with chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.15; P less than .001), reported Silvia Novello, MD, PhD, of University of Turin (Italy) and her associates. Among patients with measurable central nervous system disease, the rate of CNS objective response was significantly higher for alectinib (54%) versus chemotherapy (0%; P less than .001), Dr. Novello and her associates reported in Annals of Oncology.

The multicenter, open-label ALUR trial was the first to directly compare alectinib with standard chemotherapy in patients with ALK-rearranged NSCLC that previously had been treated with both platinum-based chemotherapy and crizotinib. In all, 107 patients were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive either alectinib (600 mg twice daily) or chemotherapy (clinician’s choice of pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks).

A blinded independent review committee calculated median progression-free survival (PFS) times that were 2.5 months shorter for alectinib and 0.2 months longer for chemotherapy. Consequently, the hazard ratio for PFS was somewhat attenuated at 0.32 but remained highly significant (95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.59). “[Median] PFS with alectinib in ALUR has exceeded that observed with [second-line] ceritinib” during the ASCEND-5 study, the researchers wrote. In ASCEND-5, median independent review committee–assessed PFS time was 5.4 months, which is 1.7 months shorter than that for alectinib in ALUR. In each study, chemotherapy yielded a median PFS time of 1.6 months, which facilitated intertrial comparisons, they wrote.

Rates of all-grade and serious adverse events were similar between arms in ALUR. Alectinib therapy caused no fatal adverse events, while chemotherapy was associated with one fatality deemed unrelated to treatment. Alectinib was more likely to produce constipation, dyspnea, and hyperbilirubinemia, while chemotherapy was more likely to cause nausea, alopecia, neutropenia, diarrhea, pruritus, stomatitis, and bacterial pneumonia. Although patients stayed on alectinib a median of 14 weeks longer than on chemotherapy, they were less likely to stop alectinib (6%) than chemotherapy (9%) for adverse events.

Dr. Novello disclosed personal fees from Roche, which markets alectinib. Eleven coinvestigators also disclosed employment, stock ownership, or other financial ties to Roche.

SOURCE: Novello S et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy121.

Questions about which next-generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) tyrosine kinase inhibitor is best for treatment-naive ALK+ NSCLC will incite “vigorous debate and the inevitable cross-trial comparison that everyone frowns upon but does anyway,” wrote Misako Nagasaka, MD; Viola W. Zhu, MD, PhD; and Sai-Hong Ignatius Ou, MD, PhD, in an editorial accompanying the study in Annals of Oncology.

Median progression-free survival time in ALUR was 7.1 months, versus 5.4 months in the similarly designed ASCEND-5 trial of second-line ceritinib in ALK+ NSCLC, they noted. “ALUR seems to confirm the superiority of alectinib [over ceritinib] in the post-crizotinib setting.”

Similarly, first-line alectinib produced a longer median progression-free survival time (25.7 months) in the ALEX trial than did first-line ceritinib (16.6 months) in the ASCEND-4 trial, the editorialists noted.

They called brigatinib “the one ALK TKI [anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitor] that can challenge alectinib.” The global phase 3 Brigatinib 3001 trial will directly compare brigatinib with alectinib in the post-chemotherapy and post-crizotinib setting.

Dr. Nagasaka is with Wayne State University, Detroit; she reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Zhu and Dr. Ou are with the University of California, Irvine; they disclosed ties to Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, and Takeda/Ariad. These comments summarize their editorial (Ann Oncol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy144 )

Questions about which next-generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) tyrosine kinase inhibitor is best for treatment-naive ALK+ NSCLC will incite “vigorous debate and the inevitable cross-trial comparison that everyone frowns upon but does anyway,” wrote Misako Nagasaka, MD; Viola W. Zhu, MD, PhD; and Sai-Hong Ignatius Ou, MD, PhD, in an editorial accompanying the study in Annals of Oncology.

Median progression-free survival time in ALUR was 7.1 months, versus 5.4 months in the similarly designed ASCEND-5 trial of second-line ceritinib in ALK+ NSCLC, they noted. “ALUR seems to confirm the superiority of alectinib [over ceritinib] in the post-crizotinib setting.”

Similarly, first-line alectinib produced a longer median progression-free survival time (25.7 months) in the ALEX trial than did first-line ceritinib (16.6 months) in the ASCEND-4 trial, the editorialists noted.

They called brigatinib “the one ALK TKI [anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitor] that can challenge alectinib.” The global phase 3 Brigatinib 3001 trial will directly compare brigatinib with alectinib in the post-chemotherapy and post-crizotinib setting.

Dr. Nagasaka is with Wayne State University, Detroit; she reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Zhu and Dr. Ou are with the University of California, Irvine; they disclosed ties to Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, and Takeda/Ariad. These comments summarize their editorial (Ann Oncol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy144 )

Questions about which next-generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) tyrosine kinase inhibitor is best for treatment-naive ALK+ NSCLC will incite “vigorous debate and the inevitable cross-trial comparison that everyone frowns upon but does anyway,” wrote Misako Nagasaka, MD; Viola W. Zhu, MD, PhD; and Sai-Hong Ignatius Ou, MD, PhD, in an editorial accompanying the study in Annals of Oncology.

Median progression-free survival time in ALUR was 7.1 months, versus 5.4 months in the similarly designed ASCEND-5 trial of second-line ceritinib in ALK+ NSCLC, they noted. “ALUR seems to confirm the superiority of alectinib [over ceritinib] in the post-crizotinib setting.”

Similarly, first-line alectinib produced a longer median progression-free survival time (25.7 months) in the ALEX trial than did first-line ceritinib (16.6 months) in the ASCEND-4 trial, the editorialists noted.

They called brigatinib “the one ALK TKI [anaplastic lymphoma kinase tyrosine kinase inhibitor] that can challenge alectinib.” The global phase 3 Brigatinib 3001 trial will directly compare brigatinib with alectinib in the post-chemotherapy and post-crizotinib setting.

Dr. Nagasaka is with Wayne State University, Detroit; she reported having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Zhu and Dr. Ou are with the University of California, Irvine; they disclosed ties to Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, and Takeda/Ariad. These comments summarize their editorial (Ann Oncol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy144 )

The second-generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor alectinib (Alcensa) topped chemotherapy in crizotinib-pretreated ALK+ non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), according to results from the phase 3 ALUR trial.

Median investigator-assessed progression-free survival was 9.6 months with alectinib and 1.4 months with chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.15; P less than .001), reported Silvia Novello, MD, PhD, of University of Turin (Italy) and her associates. Among patients with measurable central nervous system disease, the rate of CNS objective response was significantly higher for alectinib (54%) versus chemotherapy (0%; P less than .001), Dr. Novello and her associates reported in Annals of Oncology.

The multicenter, open-label ALUR trial was the first to directly compare alectinib with standard chemotherapy in patients with ALK-rearranged NSCLC that previously had been treated with both platinum-based chemotherapy and crizotinib. In all, 107 patients were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive either alectinib (600 mg twice daily) or chemotherapy (clinician’s choice of pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks).

A blinded independent review committee calculated median progression-free survival (PFS) times that were 2.5 months shorter for alectinib and 0.2 months longer for chemotherapy. Consequently, the hazard ratio for PFS was somewhat attenuated at 0.32 but remained highly significant (95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.59). “[Median] PFS with alectinib in ALUR has exceeded that observed with [second-line] ceritinib” during the ASCEND-5 study, the researchers wrote. In ASCEND-5, median independent review committee–assessed PFS time was 5.4 months, which is 1.7 months shorter than that for alectinib in ALUR. In each study, chemotherapy yielded a median PFS time of 1.6 months, which facilitated intertrial comparisons, they wrote.

Rates of all-grade and serious adverse events were similar between arms in ALUR. Alectinib therapy caused no fatal adverse events, while chemotherapy was associated with one fatality deemed unrelated to treatment. Alectinib was more likely to produce constipation, dyspnea, and hyperbilirubinemia, while chemotherapy was more likely to cause nausea, alopecia, neutropenia, diarrhea, pruritus, stomatitis, and bacterial pneumonia. Although patients stayed on alectinib a median of 14 weeks longer than on chemotherapy, they were less likely to stop alectinib (6%) than chemotherapy (9%) for adverse events.

Dr. Novello disclosed personal fees from Roche, which markets alectinib. Eleven coinvestigators also disclosed employment, stock ownership, or other financial ties to Roche.

SOURCE: Novello S et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy121.

The second-generation anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor alectinib (Alcensa) topped chemotherapy in crizotinib-pretreated ALK+ non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), according to results from the phase 3 ALUR trial.

Median investigator-assessed progression-free survival was 9.6 months with alectinib and 1.4 months with chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.15; P less than .001), reported Silvia Novello, MD, PhD, of University of Turin (Italy) and her associates. Among patients with measurable central nervous system disease, the rate of CNS objective response was significantly higher for alectinib (54%) versus chemotherapy (0%; P less than .001), Dr. Novello and her associates reported in Annals of Oncology.

The multicenter, open-label ALUR trial was the first to directly compare alectinib with standard chemotherapy in patients with ALK-rearranged NSCLC that previously had been treated with both platinum-based chemotherapy and crizotinib. In all, 107 patients were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive either alectinib (600 mg twice daily) or chemotherapy (clinician’s choice of pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks).

A blinded independent review committee calculated median progression-free survival (PFS) times that were 2.5 months shorter for alectinib and 0.2 months longer for chemotherapy. Consequently, the hazard ratio for PFS was somewhat attenuated at 0.32 but remained highly significant (95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.59). “[Median] PFS with alectinib in ALUR has exceeded that observed with [second-line] ceritinib” during the ASCEND-5 study, the researchers wrote. In ASCEND-5, median independent review committee–assessed PFS time was 5.4 months, which is 1.7 months shorter than that for alectinib in ALUR. In each study, chemotherapy yielded a median PFS time of 1.6 months, which facilitated intertrial comparisons, they wrote.

Rates of all-grade and serious adverse events were similar between arms in ALUR. Alectinib therapy caused no fatal adverse events, while chemotherapy was associated with one fatality deemed unrelated to treatment. Alectinib was more likely to produce constipation, dyspnea, and hyperbilirubinemia, while chemotherapy was more likely to cause nausea, alopecia, neutropenia, diarrhea, pruritus, stomatitis, and bacterial pneumonia. Although patients stayed on alectinib a median of 14 weeks longer than on chemotherapy, they were less likely to stop alectinib (6%) than chemotherapy (9%) for adverse events.

Dr. Novello disclosed personal fees from Roche, which markets alectinib. Eleven coinvestigators also disclosed employment, stock ownership, or other financial ties to Roche.

SOURCE: Novello S et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy121.

FROM ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Alectinib topped chemotherapy in patients with advanced/metastatic crizotinib-pretreated, ALK-positive NSCLC.

Major finding: Median investigator-assessed progression-free survival was 9.6 months with alectinib and 1.4 months with chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.15; P less than .001).

Study details: ALUR, which is a randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase 3 trial of 107 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Novello disclosed personal fees from Roche, which markets alectinib. Eleven coinvestigators also disclosed employment, stock ownership, or other financial ties to Roche.

Source: Novello S et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy121

Suicidality assessment of people with autism needs better tools

WASHINGTON – People with autism spectrum disorder face a double whammy on suicide risk: They have cognitive, social, and emotional behaviors that increase their vulnerability to suicide, but they also often find it difficult to communicate their depression and suicidality and so may often go unrecognized as suicidal. Or if they are identified, conventional prevention interventions might be less effective.

To try to address this, clinicians are trying to develop a suicide screening questionnaire that is better geared for use on people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Jacqueline Wynn, PhD said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Many people with ASD “have impaired language capabilities” that make their expressions of depression and suicide ideation more complex, she observed.

“The point is that we need better measures in the ASQ,” said John P. Ackerman, PhD, a clinical psychologist and suicide prevention coordinator at the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research at Nationwide Children’s. “There is a misperception that because people with autism don’t express their emotions and can’t always access the words they don’t have suicide ideation. They do,” he declared in an interview.

People with ASD have high rates of depression and anxiety, decreased inhibitory control and emotional regulation, rigidity or thought, and difficulty asking for help or accepting help. Youth with ASD undergo psychiatric hospitalization more than 10-fold more often than similarly aged youth without a psychiatric diagnosis, Dr. Ackerman noted. In one recent study of 374 adults with Asperger’s syndrome, two-thirds reported having suicidal ideation and one-third self-reported a planned or attempted suicide (Lancet Psychiatry. 2014 Jul;1[2]:142-7).

The risks that people with ASD have for depression and suicide contrasts with the way clinicians currently address this issue. “There are many gaps” in suicide-risk assessment and prevention interventions aimed at people with ASD, he said. For example, a depression symptom checklist that asks whether someone is withdrawn or feeling disconnected focuses on commonplace characteristics among people with ASD.

The recognition that people with ASD need tailored methods for both identifying and intervening with suicidality appears to be part of an emerging appreciation by clinicians who work on suicide prevention of the “need to meet people where they are,” Dr. Ackerman said. Similar approaches might be needed for various ethnic and racial groups, gays, transgender people, those who are hearing impaired, and others who might respond better to novel approaches.

Dr. Wynn and Dr. Ackerman had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – People with autism spectrum disorder face a double whammy on suicide risk: They have cognitive, social, and emotional behaviors that increase their vulnerability to suicide, but they also often find it difficult to communicate their depression and suicidality and so may often go unrecognized as suicidal. Or if they are identified, conventional prevention interventions might be less effective.

To try to address this, clinicians are trying to develop a suicide screening questionnaire that is better geared for use on people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Jacqueline Wynn, PhD said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Many people with ASD “have impaired language capabilities” that make their expressions of depression and suicide ideation more complex, she observed.

“The point is that we need better measures in the ASQ,” said John P. Ackerman, PhD, a clinical psychologist and suicide prevention coordinator at the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research at Nationwide Children’s. “There is a misperception that because people with autism don’t express their emotions and can’t always access the words they don’t have suicide ideation. They do,” he declared in an interview.

People with ASD have high rates of depression and anxiety, decreased inhibitory control and emotional regulation, rigidity or thought, and difficulty asking for help or accepting help. Youth with ASD undergo psychiatric hospitalization more than 10-fold more often than similarly aged youth without a psychiatric diagnosis, Dr. Ackerman noted. In one recent study of 374 adults with Asperger’s syndrome, two-thirds reported having suicidal ideation and one-third self-reported a planned or attempted suicide (Lancet Psychiatry. 2014 Jul;1[2]:142-7).

The risks that people with ASD have for depression and suicide contrasts with the way clinicians currently address this issue. “There are many gaps” in suicide-risk assessment and prevention interventions aimed at people with ASD, he said. For example, a depression symptom checklist that asks whether someone is withdrawn or feeling disconnected focuses on commonplace characteristics among people with ASD.

The recognition that people with ASD need tailored methods for both identifying and intervening with suicidality appears to be part of an emerging appreciation by clinicians who work on suicide prevention of the “need to meet people where they are,” Dr. Ackerman said. Similar approaches might be needed for various ethnic and racial groups, gays, transgender people, those who are hearing impaired, and others who might respond better to novel approaches.

Dr. Wynn and Dr. Ackerman had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – People with autism spectrum disorder face a double whammy on suicide risk: They have cognitive, social, and emotional behaviors that increase their vulnerability to suicide, but they also often find it difficult to communicate their depression and suicidality and so may often go unrecognized as suicidal. Or if they are identified, conventional prevention interventions might be less effective.

To try to address this, clinicians are trying to develop a suicide screening questionnaire that is better geared for use on people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Jacqueline Wynn, PhD said at the annual conference of the American Association of Suicidology.

Many people with ASD “have impaired language capabilities” that make their expressions of depression and suicide ideation more complex, she observed.

“The point is that we need better measures in the ASQ,” said John P. Ackerman, PhD, a clinical psychologist and suicide prevention coordinator at the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research at Nationwide Children’s. “There is a misperception that because people with autism don’t express their emotions and can’t always access the words they don’t have suicide ideation. They do,” he declared in an interview.

People with ASD have high rates of depression and anxiety, decreased inhibitory control and emotional regulation, rigidity or thought, and difficulty asking for help or accepting help. Youth with ASD undergo psychiatric hospitalization more than 10-fold more often than similarly aged youth without a psychiatric diagnosis, Dr. Ackerman noted. In one recent study of 374 adults with Asperger’s syndrome, two-thirds reported having suicidal ideation and one-third self-reported a planned or attempted suicide (Lancet Psychiatry. 2014 Jul;1[2]:142-7).

The risks that people with ASD have for depression and suicide contrasts with the way clinicians currently address this issue. “There are many gaps” in suicide-risk assessment and prevention interventions aimed at people with ASD, he said. For example, a depression symptom checklist that asks whether someone is withdrawn or feeling disconnected focuses on commonplace characteristics among people with ASD.

The recognition that people with ASD need tailored methods for both identifying and intervening with suicidality appears to be part of an emerging appreciation by clinicians who work on suicide prevention of the “need to meet people where they are,” Dr. Ackerman said. Similar approaches might be needed for various ethnic and racial groups, gays, transgender people, those who are hearing impaired, and others who might respond better to novel approaches.

Dr. Wynn and Dr. Ackerman had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE AAS ANNUAL CONFERENCE

CMS floats Medicare direct provider contracting

Under a direct provider contracting (DPC) arrangement, Medicare could pay physicians or physician groups a monthly fee to deliver a specific set of services to beneficiaries, who would gain greater access to the physicians. The physicians would be accountable for those Medicare patients’ costs and care quality.

CMS is looking at how to incorporate this concept into the Medicare ranks. On April 23, CMS issued a request for information (RFI) seeking input across a wide range of topics, including provider/state participation, beneficiary participation, payment, general model design, program integrity and beneficiary protection, and how such models would fit within the existing accountable care organization framework.

The RFI offered one possible vision on how a direct provider contracting model could work.

“Under a primary care–focused DPC model, CMS could enter into arrangements with primary care practices under which CMS would pay these participating practices a fixed per beneficiary per month (PBPM) payment to cover the primary care services the practice would be expected to furnish under the model, which may include office visits, certain office-based procedures, and other non–visit-based services covered under the physician fee schedule, and flexibility in how otherwise billable services are delivered,” the RFI states.

Physicians could also earn performance bonuses, depending on how the DPC is structured, through “performance-based incentives for total cost of care and quality.”

CMS noted it also “could test ways to reduce administrative burden though innovative changes to claims submission processes for services included in the PBPM payment under these models.”

The direct provider contracting idea grew out of a previous RFI issued in 2017 by CMS’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to collect ideas on new ways to deliver patient-centered care. The agency released the more than 1,000 comments received from that request on the same day it issued the RFI on direct provider contracting.

In those comments, a number of physician groups offered support for a direct-contracting approach.

For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that it “sees continued growth and interest in family physicians adopting this practice model in all settings types, including rural and underserved communities.” And the AAFP suggested that the innovation center should work with DPC organizations to learn more about them.

The American College of Physicians reiterated its previous position that it “supports physician and patient choice of practice and delivery models that are accessible, ethical, and viable and that strengthen the patient-physician relationship.” But the ACP raised a number of issues that could impede access to care or result in lower quality care.

The American Medical Association offered support for “testing of models in which physicians have the ability to deliver more or different services to patients who need them and to be paid more for doing so.”

The AMA suggested that some of the models to be tested include allowing patients to contract directly with physicians, with Medicare paying its fee schedule rates and patients paying the difference; allowing patients to receive their care from DPC practices and get reimbursed by Medicare; or allowing “physicians to define a team of providers who will provide all of the treatment needed for an acute condition or management of a chronic condition, and then allowing patients who select the team to receive all of the services related to their condition from the team in return for a single predefined cost-sharing amount.”

Comments on the RFI are due May 25.

Under a direct provider contracting (DPC) arrangement, Medicare could pay physicians or physician groups a monthly fee to deliver a specific set of services to beneficiaries, who would gain greater access to the physicians. The physicians would be accountable for those Medicare patients’ costs and care quality.

CMS is looking at how to incorporate this concept into the Medicare ranks. On April 23, CMS issued a request for information (RFI) seeking input across a wide range of topics, including provider/state participation, beneficiary participation, payment, general model design, program integrity and beneficiary protection, and how such models would fit within the existing accountable care organization framework.

The RFI offered one possible vision on how a direct provider contracting model could work.

“Under a primary care–focused DPC model, CMS could enter into arrangements with primary care practices under which CMS would pay these participating practices a fixed per beneficiary per month (PBPM) payment to cover the primary care services the practice would be expected to furnish under the model, which may include office visits, certain office-based procedures, and other non–visit-based services covered under the physician fee schedule, and flexibility in how otherwise billable services are delivered,” the RFI states.

Physicians could also earn performance bonuses, depending on how the DPC is structured, through “performance-based incentives for total cost of care and quality.”

CMS noted it also “could test ways to reduce administrative burden though innovative changes to claims submission processes for services included in the PBPM payment under these models.”

The direct provider contracting idea grew out of a previous RFI issued in 2017 by CMS’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to collect ideas on new ways to deliver patient-centered care. The agency released the more than 1,000 comments received from that request on the same day it issued the RFI on direct provider contracting.

In those comments, a number of physician groups offered support for a direct-contracting approach.

For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that it “sees continued growth and interest in family physicians adopting this practice model in all settings types, including rural and underserved communities.” And the AAFP suggested that the innovation center should work with DPC organizations to learn more about them.

The American College of Physicians reiterated its previous position that it “supports physician and patient choice of practice and delivery models that are accessible, ethical, and viable and that strengthen the patient-physician relationship.” But the ACP raised a number of issues that could impede access to care or result in lower quality care.

The American Medical Association offered support for “testing of models in which physicians have the ability to deliver more or different services to patients who need them and to be paid more for doing so.”

The AMA suggested that some of the models to be tested include allowing patients to contract directly with physicians, with Medicare paying its fee schedule rates and patients paying the difference; allowing patients to receive their care from DPC practices and get reimbursed by Medicare; or allowing “physicians to define a team of providers who will provide all of the treatment needed for an acute condition or management of a chronic condition, and then allowing patients who select the team to receive all of the services related to their condition from the team in return for a single predefined cost-sharing amount.”

Comments on the RFI are due May 25.

Under a direct provider contracting (DPC) arrangement, Medicare could pay physicians or physician groups a monthly fee to deliver a specific set of services to beneficiaries, who would gain greater access to the physicians. The physicians would be accountable for those Medicare patients’ costs and care quality.

CMS is looking at how to incorporate this concept into the Medicare ranks. On April 23, CMS issued a request for information (RFI) seeking input across a wide range of topics, including provider/state participation, beneficiary participation, payment, general model design, program integrity and beneficiary protection, and how such models would fit within the existing accountable care organization framework.

The RFI offered one possible vision on how a direct provider contracting model could work.

“Under a primary care–focused DPC model, CMS could enter into arrangements with primary care practices under which CMS would pay these participating practices a fixed per beneficiary per month (PBPM) payment to cover the primary care services the practice would be expected to furnish under the model, which may include office visits, certain office-based procedures, and other non–visit-based services covered under the physician fee schedule, and flexibility in how otherwise billable services are delivered,” the RFI states.

Physicians could also earn performance bonuses, depending on how the DPC is structured, through “performance-based incentives for total cost of care and quality.”

CMS noted it also “could test ways to reduce administrative burden though innovative changes to claims submission processes for services included in the PBPM payment under these models.”

The direct provider contracting idea grew out of a previous RFI issued in 2017 by CMS’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to collect ideas on new ways to deliver patient-centered care. The agency released the more than 1,000 comments received from that request on the same day it issued the RFI on direct provider contracting.

In those comments, a number of physician groups offered support for a direct-contracting approach.

For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians wrote that it “sees continued growth and interest in family physicians adopting this practice model in all settings types, including rural and underserved communities.” And the AAFP suggested that the innovation center should work with DPC organizations to learn more about them.

The American College of Physicians reiterated its previous position that it “supports physician and patient choice of practice and delivery models that are accessible, ethical, and viable and that strengthen the patient-physician relationship.” But the ACP raised a number of issues that could impede access to care or result in lower quality care.

The American Medical Association offered support for “testing of models in which physicians have the ability to deliver more or different services to patients who need them and to be paid more for doing so.”

The AMA suggested that some of the models to be tested include allowing patients to contract directly with physicians, with Medicare paying its fee schedule rates and patients paying the difference; allowing patients to receive their care from DPC practices and get reimbursed by Medicare; or allowing “physicians to define a team of providers who will provide all of the treatment needed for an acute condition or management of a chronic condition, and then allowing patients who select the team to receive all of the services related to their condition from the team in return for a single predefined cost-sharing amount.”

Comments on the RFI are due May 25.

Liquid nicotine for e-cigarettes may poison young children

said Preethi Govindarajan of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his associates.

Since January 2015, pediatric exposures to liquid nicotine have decreased, which may be attributable to legislation requiring child-resistant packaging for liquid nicotine containers and also greater public awareness of the risks associated with e-cigarette products, they noted.

There was a significant increase in the monthly number of liquid nicotine exposures of 2,390% (P less than .001) from November 2012 through January 2015, and a significant decrease of 48% (P less than .001) from January 2015 through April 2017. “From August 2016 (175 exposures), the first month after the federal Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act went into effect, to April 2017 (142 exposures), there was an 18.9% decrease in the number of monthly liquid nicotine exposures,” Mr. Govindarajan and his associates said.

“Child-resistant e-cigarette devices, use of flow restrictors on liquid nicotine containers, and regulations on e-cigarette liquid flavoring, labeling, and concentrations could further reduce the incidence of these exposures and the likelihood of serious medical outcomes when exposures do occur,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Govindarajan P et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173361.

said Preethi Govindarajan of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his associates.

Since January 2015, pediatric exposures to liquid nicotine have decreased, which may be attributable to legislation requiring child-resistant packaging for liquid nicotine containers and also greater public awareness of the risks associated with e-cigarette products, they noted.

There was a significant increase in the monthly number of liquid nicotine exposures of 2,390% (P less than .001) from November 2012 through January 2015, and a significant decrease of 48% (P less than .001) from January 2015 through April 2017. “From August 2016 (175 exposures), the first month after the federal Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act went into effect, to April 2017 (142 exposures), there was an 18.9% decrease in the number of monthly liquid nicotine exposures,” Mr. Govindarajan and his associates said.

“Child-resistant e-cigarette devices, use of flow restrictors on liquid nicotine containers, and regulations on e-cigarette liquid flavoring, labeling, and concentrations could further reduce the incidence of these exposures and the likelihood of serious medical outcomes when exposures do occur,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Govindarajan P et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173361.

said Preethi Govindarajan of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his associates.

Since January 2015, pediatric exposures to liquid nicotine have decreased, which may be attributable to legislation requiring child-resistant packaging for liquid nicotine containers and also greater public awareness of the risks associated with e-cigarette products, they noted.

There was a significant increase in the monthly number of liquid nicotine exposures of 2,390% (P less than .001) from November 2012 through January 2015, and a significant decrease of 48% (P less than .001) from January 2015 through April 2017. “From August 2016 (175 exposures), the first month after the federal Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act went into effect, to April 2017 (142 exposures), there was an 18.9% decrease in the number of monthly liquid nicotine exposures,” Mr. Govindarajan and his associates said.

“Child-resistant e-cigarette devices, use of flow restrictors on liquid nicotine containers, and regulations on e-cigarette liquid flavoring, labeling, and concentrations could further reduce the incidence of these exposures and the likelihood of serious medical outcomes when exposures do occur,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Govindarajan P et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173361.

Targeting inactivity, mood, and cognition could be key to reducing OA mortality

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Osteoarthritis is associated with an increased risk in mortality, but three factors – inactivity, low mood, and cognitive ability – could be important targets to reduce this risk, according to the results of a study presented at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

“There’s recently been increasing interest in whether osteoarthritis (OA) is associated with mortality as the literature has failed to find a consistent link,” said Simran Parmar, a third-year medical student at Keele University, Newcastle-Under-Lyme, U.K.

Three years later, data from another study (BMJ. 2011;342:d1165) suggested an increased risk, with standardized mortality ratios calculated to be 1.55 for all-cause mortality and 1.71 for cardiovascular-specific mortality when comparing those with OA to those without OA in the general population.

However, more recent meta-analyses, performed in 2016, have failed to show a relationship between mortality and OA (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46[2]:160–7; Sci Rep. 2016;6:24393).

“This could be because of heterogeneity among the studies,” Mr. Parmar reasoned, adding that there was still an unclear relationship between OA and mortality.

So the aim of the current study was not only to take another look at the association to determine its strength but also to see what factors might be mediating the association in order to perhaps explain why OA might be associated with an increased risk of death.

The analysis used data on more than 8,000 individuals participating in the NorStOP (North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project). This is a large, population-based, prospective cohort initiated in 2002 that includes adults aged 50 years or older who are registered at any of six general practices.

At baseline, the mean age of participants was 65 years, 51% were female, and just under 30% had OA. During 10 years of follow-up, 1,188 (14.7%) participants died.

Osteoarthritis was significantly associated with mortality in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

“For the average person presenting to general practice in North Staffordshire, there’s a 39.4% increased risk of mortality if they have osteoarthritis compared to if they don’t,” Mr. Parmar said.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, such as age, NSAID use, and common comorbidities, the increased mortality risk remained, with around a 15% increased risk of death for those with OA versus those without.

“We proposed six different mediators of this relationship,” Mr. Parmar said. These were depression, anxiety, low walking frequency, cognitive impairment, insomnia, and obesity. “The reason we chose these is because they can be targets for therapy in primary care.”

Three mediators significantly affected the relationship: low walking frequency, depression, and cognitive impairment; the respective hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were 1.12 (1.09-1.15), 1.11 (1.08-1.15), and 1.06 (1.03-1.09).

“This tells us that these could possibly be on the pathway between osteoarthritis and mortality, and this could provide further evidence that they could be used for targeted therapy of osteoarthritis,” Mr. Parmar suggested.

“This type of mediation analysis has not been done in the osteoarthritis field before,” Mr. Parmar observed. He conceded that the mediators found might actually have contributed to the development of OA and that pain interference used in the definition of OA could have been caused by other factors.

Nevertheless, these data suggest that there may be actionable factors that could be used in primary care to reduce mortality in OA.

Mr. Parmar suggested that “encouraging physical activity and considering the impact of comorbidities can help reduce the risk of mortality in adults with osteoarthritis.”

The study was funded by Arthritis Research UK, the North Staffordshire Primary Care Consortium, and the Medical Research Council. Mr. Parmar had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Parmar S et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(1):S14-15.

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Osteoarthritis is associated with an increased risk in mortality, but three factors – inactivity, low mood, and cognitive ability – could be important targets to reduce this risk, according to the results of a study presented at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

“There’s recently been increasing interest in whether osteoarthritis (OA) is associated with mortality as the literature has failed to find a consistent link,” said Simran Parmar, a third-year medical student at Keele University, Newcastle-Under-Lyme, U.K.

Three years later, data from another study (BMJ. 2011;342:d1165) suggested an increased risk, with standardized mortality ratios calculated to be 1.55 for all-cause mortality and 1.71 for cardiovascular-specific mortality when comparing those with OA to those without OA in the general population.

However, more recent meta-analyses, performed in 2016, have failed to show a relationship between mortality and OA (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46[2]:160–7; Sci Rep. 2016;6:24393).

“This could be because of heterogeneity among the studies,” Mr. Parmar reasoned, adding that there was still an unclear relationship between OA and mortality.

So the aim of the current study was not only to take another look at the association to determine its strength but also to see what factors might be mediating the association in order to perhaps explain why OA might be associated with an increased risk of death.

The analysis used data on more than 8,000 individuals participating in the NorStOP (North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project). This is a large, population-based, prospective cohort initiated in 2002 that includes adults aged 50 years or older who are registered at any of six general practices.

At baseline, the mean age of participants was 65 years, 51% were female, and just under 30% had OA. During 10 years of follow-up, 1,188 (14.7%) participants died.

Osteoarthritis was significantly associated with mortality in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

“For the average person presenting to general practice in North Staffordshire, there’s a 39.4% increased risk of mortality if they have osteoarthritis compared to if they don’t,” Mr. Parmar said.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, such as age, NSAID use, and common comorbidities, the increased mortality risk remained, with around a 15% increased risk of death for those with OA versus those without.

“We proposed six different mediators of this relationship,” Mr. Parmar said. These were depression, anxiety, low walking frequency, cognitive impairment, insomnia, and obesity. “The reason we chose these is because they can be targets for therapy in primary care.”

Three mediators significantly affected the relationship: low walking frequency, depression, and cognitive impairment; the respective hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were 1.12 (1.09-1.15), 1.11 (1.08-1.15), and 1.06 (1.03-1.09).

“This tells us that these could possibly be on the pathway between osteoarthritis and mortality, and this could provide further evidence that they could be used for targeted therapy of osteoarthritis,” Mr. Parmar suggested.

“This type of mediation analysis has not been done in the osteoarthritis field before,” Mr. Parmar observed. He conceded that the mediators found might actually have contributed to the development of OA and that pain interference used in the definition of OA could have been caused by other factors.

Nevertheless, these data suggest that there may be actionable factors that could be used in primary care to reduce mortality in OA.

Mr. Parmar suggested that “encouraging physical activity and considering the impact of comorbidities can help reduce the risk of mortality in adults with osteoarthritis.”

The study was funded by Arthritis Research UK, the North Staffordshire Primary Care Consortium, and the Medical Research Council. Mr. Parmar had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Parmar S et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(1):S14-15.

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND – Osteoarthritis is associated with an increased risk in mortality, but three factors – inactivity, low mood, and cognitive ability – could be important targets to reduce this risk, according to the results of a study presented at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

“There’s recently been increasing interest in whether osteoarthritis (OA) is associated with mortality as the literature has failed to find a consistent link,” said Simran Parmar, a third-year medical student at Keele University, Newcastle-Under-Lyme, U.K.

Three years later, data from another study (BMJ. 2011;342:d1165) suggested an increased risk, with standardized mortality ratios calculated to be 1.55 for all-cause mortality and 1.71 for cardiovascular-specific mortality when comparing those with OA to those without OA in the general population.

However, more recent meta-analyses, performed in 2016, have failed to show a relationship between mortality and OA (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46[2]:160–7; Sci Rep. 2016;6:24393).

“This could be because of heterogeneity among the studies,” Mr. Parmar reasoned, adding that there was still an unclear relationship between OA and mortality.

So the aim of the current study was not only to take another look at the association to determine its strength but also to see what factors might be mediating the association in order to perhaps explain why OA might be associated with an increased risk of death.

The analysis used data on more than 8,000 individuals participating in the NorStOP (North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project). This is a large, population-based, prospective cohort initiated in 2002 that includes adults aged 50 years or older who are registered at any of six general practices.

At baseline, the mean age of participants was 65 years, 51% were female, and just under 30% had OA. During 10 years of follow-up, 1,188 (14.7%) participants died.

Osteoarthritis was significantly associated with mortality in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses.

“For the average person presenting to general practice in North Staffordshire, there’s a 39.4% increased risk of mortality if they have osteoarthritis compared to if they don’t,” Mr. Parmar said.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, such as age, NSAID use, and common comorbidities, the increased mortality risk remained, with around a 15% increased risk of death for those with OA versus those without.

“We proposed six different mediators of this relationship,” Mr. Parmar said. These were depression, anxiety, low walking frequency, cognitive impairment, insomnia, and obesity. “The reason we chose these is because they can be targets for therapy in primary care.”

Three mediators significantly affected the relationship: low walking frequency, depression, and cognitive impairment; the respective hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were 1.12 (1.09-1.15), 1.11 (1.08-1.15), and 1.06 (1.03-1.09).

“This tells us that these could possibly be on the pathway between osteoarthritis and mortality, and this could provide further evidence that they could be used for targeted therapy of osteoarthritis,” Mr. Parmar suggested.

“This type of mediation analysis has not been done in the osteoarthritis field before,” Mr. Parmar observed. He conceded that the mediators found might actually have contributed to the development of OA and that pain interference used in the definition of OA could have been caused by other factors.

Nevertheless, these data suggest that there may be actionable factors that could be used in primary care to reduce mortality in OA.

Mr. Parmar suggested that “encouraging physical activity and considering the impact of comorbidities can help reduce the risk of mortality in adults with osteoarthritis.”

The study was funded by Arthritis Research UK, the North Staffordshire Primary Care Consortium, and the Medical Research Council. Mr. Parmar had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Parmar S et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(1):S14-15.

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: OA is associated with a 15% increased risk of mortality in the general population.

Study details: A large, prospective cohort study that included more than 8,000 adults older than 50 years in the general population who participated.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Arthritis Research UK, the North Staffordshire Primary Care Consortium, and the Medical Research Council. Mr. Parmar had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source: Parmar S et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(1):S14-15.

May 2018 - What's your diagnosis?

By Umberto G. Rossi, MD, Paolo Rigamonti, MD, and Maurizio Cariati, MD

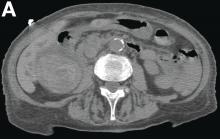

Intraluminal gallbladder arterial hemorrhage as a complication of arteriosclerosis and anticoagulant therapy

This radiologic sign on multiphasic contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography with axial images (Figure A-C), coronal multiplanar reconstruction (Figure D) and coronal volume rendering technique were indicative for active hemorrhage of gallbladder wall. During the urgent surgical treatment, there was confirmation of that distended gallbladder. Postoperatively, opening of the gallbladder revealed in its lumen the presence of bile mixed with dishomogeneous blood clots. Pathologic evaluation demonstrated arteriosclerosis of the cystic artery, with a pseudoaneurysmatic tear of one of its collateral branches with focal surround inflammatory tissue of gallbladder wall. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on day 8.

Hemorrhage from the gallbladder is not a frequent event.1 The etiologies for hemorrhage of the gallbladder are trauma, neoplasms, inflammation of the wall with gallstones, aneurysms, varicose veins with portal hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and coagulopathy. However, isolated gallbladder arterial hemorrhage owing to anticoagulation therapy has been reported rarely. This pathologic state can be detected by contrast-enhanced ultrasound, contrast-enhanced computed tomography, and digital subtraction angiography.2,3

References

1. Hudson, P.B., Johnson, P.P. Hemorrhage from the gall bladder. N Engl J Med. 1946;234:438-41.

2. Krudy, A.G., Doppman, J.L., Bissonette, M.B., et al. Hemobilia: computed tomographic diagnosis. Radiology. 1983;148:785-9.

3. Pandya, R., O'Malley, C. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis as a complication of anticoagulant therapy: role of CT in its diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:652-3.

By Umberto G. Rossi, MD, Paolo Rigamonti, MD, and Maurizio Cariati, MD

Intraluminal gallbladder arterial hemorrhage as a complication of arteriosclerosis and anticoagulant therapy

This radiologic sign on multiphasic contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography with axial images (Figure A-C), coronal multiplanar reconstruction (Figure D) and coronal volume rendering technique were indicative for active hemorrhage of gallbladder wall. During the urgent surgical treatment, there was confirmation of that distended gallbladder. Postoperatively, opening of the gallbladder revealed in its lumen the presence of bile mixed with dishomogeneous blood clots. Pathologic evaluation demonstrated arteriosclerosis of the cystic artery, with a pseudoaneurysmatic tear of one of its collateral branches with focal surround inflammatory tissue of gallbladder wall. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on day 8.

Hemorrhage from the gallbladder is not a frequent event.1 The etiologies for hemorrhage of the gallbladder are trauma, neoplasms, inflammation of the wall with gallstones, aneurysms, varicose veins with portal hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and coagulopathy. However, isolated gallbladder arterial hemorrhage owing to anticoagulation therapy has been reported rarely. This pathologic state can be detected by contrast-enhanced ultrasound, contrast-enhanced computed tomography, and digital subtraction angiography.2,3

References

1. Hudson, P.B., Johnson, P.P. Hemorrhage from the gall bladder. N Engl J Med. 1946;234:438-41.

2. Krudy, A.G., Doppman, J.L., Bissonette, M.B., et al. Hemobilia: computed tomographic diagnosis. Radiology. 1983;148:785-9.

3. Pandya, R., O'Malley, C. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis as a complication of anticoagulant therapy: role of CT in its diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:652-3.

By Umberto G. Rossi, MD, Paolo Rigamonti, MD, and Maurizio Cariati, MD

Intraluminal gallbladder arterial hemorrhage as a complication of arteriosclerosis and anticoagulant therapy

This radiologic sign on multiphasic contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography with axial images (Figure A-C), coronal multiplanar reconstruction (Figure D) and coronal volume rendering technique were indicative for active hemorrhage of gallbladder wall. During the urgent surgical treatment, there was confirmation of that distended gallbladder. Postoperatively, opening of the gallbladder revealed in its lumen the presence of bile mixed with dishomogeneous blood clots. Pathologic evaluation demonstrated arteriosclerosis of the cystic artery, with a pseudoaneurysmatic tear of one of its collateral branches with focal surround inflammatory tissue of gallbladder wall. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on day 8.

Hemorrhage from the gallbladder is not a frequent event.1 The etiologies for hemorrhage of the gallbladder are trauma, neoplasms, inflammation of the wall with gallstones, aneurysms, varicose veins with portal hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and coagulopathy. However, isolated gallbladder arterial hemorrhage owing to anticoagulation therapy has been reported rarely. This pathologic state can be detected by contrast-enhanced ultrasound, contrast-enhanced computed tomography, and digital subtraction angiography.2,3

References

1. Hudson, P.B., Johnson, P.P. Hemorrhage from the gall bladder. N Engl J Med. 1946;234:438-41.

2. Krudy, A.G., Doppman, J.L., Bissonette, M.B., et al. Hemobilia: computed tomographic diagnosis. Radiology. 1983;148:785-9.

3. Pandya, R., O'Malley, C. Hemorrhagic cholecystitis as a complication of anticoagulant therapy: role of CT in its diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:652-3.

She had a medical history of cardiac arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation) with pacemaker insertion and anticoagulant therapy (warfarin 2.5 mg/d).

There was no alteration in liver function tests.

She underwent abdominal multiphasic contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography.

On the arterial phase (Figure B, arrowhead) it appeared inside the lumen of the gallbladder at the middle third of the inferior wall, a focal contrast media area, which become more evident on venous phase (Figure C, D, arrowhead).