User login

Pseudomyogenic Hemangioendothelioma

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.

- Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. a fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382-1395.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190-201.

- Sheng W, Pan Y, Wang J. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: report of an additional case with aggressive clinical course. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:597-600.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48-57.

- Pradhan D, Schoedel K, McGough RL, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma of skin, bone and soft tissue—a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization study [published online November 2, 2017]. Hum Pathol. 2017. doi:0.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.023.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- McGinity M, Bartanusz V, Dengler B, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma) of the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(suppl 3):S506-S511.

- Stuart LN, Gardner JM, Lauer SR, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma, clinically mimicking dermatofibroma, diagnosed by skin biopsy in a 30-year-old man. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:909-913.

- Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:947-957.

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542-550.

- Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:222-227.

- Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211-215.

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE), also referred to as epithelioid sarcoma–like hemangioendothelioma,1 is a rare soft tissue tumor that was described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. It predominantly affects males between the second and fifth decades of life and most commonly presents as multiple nodules that may involve either the superficial or deep soft tissues of the legs and less often the arms. It also can arise on the trunk. We present a case of PMHE occurring in a young man and briefly review the literature on clinical presentation and histologic differentiation of this unique tumor, comparing these findings to its mimickers.

Case Report

A 20-year-old man presented with skin lesions on the left leg that had been present for 1 year. The patient described the lesions as tender pimples that would drain yellow discharge on occasion but had now transformed into large brown plaques. Physical examination showed 4 verrucous plaques ranging in size from 1 to 3 cm with hyperpigmentation and a central crust (Figure 1). Initially, the patient thought the lesions appeared due to shaving his legs for sports. He presented to the emergency department multiple times over the past year; pain control was provided and local skin care was recommended. Culture of the discharge had been performed 6 months prior to biopsy with negative results. No biopsy was performed on initial presentation and the lesions were diagnosed in the emergency department clinically as boils.

After failing to improve, the patient was seen by an outside dermatologist and the clinical differential diagnosis included deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, and keloids. A 4-mm punch biopsy was taken from the periphery of one of the lesions and demonstrated hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Within the superficial and deep dermis and focally extending into the subcutaneous tissue, there were sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with moderate cytologic atypia (Figure 3). The tumor showed infiltrative margins. There was moderate cellularity. The individual cells had a rhabdoid appearance with large eccentric vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 4). No definitive evidence of glandular, squamous, or vascular differentiation was present. There was an associated moderate inflammatory host response composed of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Occasional extravasated red blood cells were present. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed and the atypical cells demonstrated diffuse positive staining for friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI-1), erythroblastosis virus E26 transforming sequence-related gene (ERG)(Figure 5), CD31, and CD68. There was patchy positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD10, and factor VIII. There was no remarkable staining for human herpesvirus 8, epithelial membrane antigen, S-100, CD34, cytokeratin 903, and desmin. Overall, the histologic features in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry staining were consistent with a diagnosis of PMHE.

Magnetic resonance imaging was then performed to evaluate the depth and extent of the lesions for surgical excision planning (Figure 6), which showed 5 nodular lesions within the dermis and subcutis adjacent to the proximal aspect of the left tibia and medial aspect of the left knee. An additional lesion was noted between the sartorius and semimembranosus muscles, which was thought to represent either a lymph node or an additional neoplastic lesion. Chest computed tomography also displayed indeterminate lesions in the lungs.

Excision of the superficial lesions was performed. All of the lesions demonstrated similar histologic changes to the previously described biopsy specimen. The tumor was limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The patient was lost to follow-up and the etiology of the lung lesions was unknown.

Comment

Nomenclature

Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma is a relatively new type of vascular tumor that has been included in the updated 2013 edition of the World Health Organization classification as an intermediate malignant tumor that rarely metastasizes.3 It typically involves multiple tissue planes, most notably the dermis and subcutaneous layers but also muscle and bone.4 The term pseudomyogenic refers to the histologic resemblance of some of the cells to rhabdomyoblasts; however, these tumors are negative for all immunohistochemical muscle markers, most notably myogenin, desmin, and α-smooth muscle actin.5

Clinical Presentation

Gross features of PMHE typically include multiple firm nodules with ill-defined margins. The tumor was initially described in 1992 by Mirra et al2 as a fibromalike variant of epithelioid sarcoma. In 2003, a series of 7 cases of PMHE was reported by Billings et al6 under the term epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma. Other than the predominance of an epithelioid morphology, the cases reported as epithelioid sarcomalike hemangioendothelioma had similar clinical features and immunophenotype to what has been reported as PMHE.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, the 2 largest case series were reported by Pradhan et al7 (N=8) in 2017 and Hornick and Fletcher4 (N=50) in 2011. Hornick and Fletcher4 reported a male (41/50 [82.0%]) to female (9/50 [18.0%]) ratio of 4.6 to 1, and an average age at presentation of 31 years with 82% (41/50) of patients 40 years or younger. Pradhan et al7 also reported a male predominance (7/8 [87.5%]) with a similar average age at presentation of 29 years (age range, 9–62 years). The size of individual tumors ranged from 0.3 to 5.5 cm (mean size, 1.9 cm) in the series by Hornick and Fletcher4 and 0.3 to 6.0 com in the series by Pradhan et al.7 Hornick and Fletcher4 reported the most common site of involvement was the leg (27/50 [54.0%]), followed by the arm (12/50 [24.0%]), trunk (9/50 [18.0%]), and head and neck (2/50 [4.0%]). The leg (6/8 [75.0%]) also was the most common site of involvement in the series by Pradhan et al,7 with 2 cases occurring on the arm. In the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 the tumors typically involved the dermis and subcutaneous tissue (26/50 [52%]) with a smaller number involving skeletal muscle (17/50 [34%]) and bone (7/50 [14%]). They reported 66% of their patients (33/50) had multifocal disease at presentation.4 Pradhan et al7 also reported 2 (25.0%) cases being limited to the superficial soft tissue, 2 (25.0%) being limited to the deep soft tissue, and 4 (50.0%) involving the bone; 5 (62.5%) patients had multifocal disease at presentation. The presentation of our patient in regards to gender, age, and tumor characteristics is consistent with other published cases.5-10

Histopathology

Microscopic features of PMHE include sheets of spindled to epithelioid-appearing cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor has an infiltrative growth pattern. Some of the cells may resemble rhabdomyoblastlike cells, hence the moniker pseudomyogenic. There is no recapitulation of vascular structures or remarkable cytoplasmic vacuolization. Mitotic rate is low and there is no tumor necrosis.4 The tumor cells do not appear to arise from a vessel or display an angiocentric growth pattern. Many cases report the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate containing neutrophils interspersed within the tumor.4,5,7 The overlying epidermis will commonly show hyperkeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, and acanthosis.4,11

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis would include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and to a lesser extent dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is the most commonly encountered of these tumors. Histologically, DFSP is characterized by a cellular proliferation of small spindle cells with plump nuclei arranged in a storiform or cartwheel pattern. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to be limited to the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and only rarely involves underlying skeletal muscle. The presence of the storiform growth pattern in conjunction with the lack of rhabdoid changes would favor a diagnosis of DFSP. Another characteristic histologic finding typically only associated with DFSP is the interdigitating growth pattern of the spindle cells within the lobules of the subcutaneous tissue, creating a lacelike or honeycomb appearance.

Immunohistochemistry staining is necessary to help differentiate PMHE from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma stains positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3; integrase interactor 1; and vascular markers FLI-1, CD31, and ERG, and negative for CD34.4,6,12-15 In contrast to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, DFSP, and to a lesser extent epithelioid sarcoma, all of which are positive for CD34, epithelioid sarcoma is negative for both CD31 and integrase interactor 1. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Rhabdomyosarcomas are positive for myogenic markers such as MyoD1 and myogenin, unlike any of the other tumors mentioned. Histologically, epithelioid sarcomas will tend to have a granulomalike growth pattern with central necrosis, unlike PMHE.12 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma often will have a cordlike growth pattern in a myxochondroid background. Unlike PMHE, these tumors often will appear to be arising from vessels, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are common. Three cases of PMHE have been reported to have a t(7;19)(q22;q13) chromosomal anomaly, which is not consistent with every case.16

Treatment Options

Standard treatment typically includes wide excision of the lesions, as was done in our case. Because of the substantial risk of local recurrence, which was up to 58% in the series by Hornick and Fletcher,4 adjuvant therapy may be considered if positive margins are found on excision. Metastasis to lymph nodes and the lungs has been reported but is rare.2,4 Most cases have been shown to have a favorable prognosis; however, local recurrence seems to be common. Rarely, amputation of the limb may be required.5 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas have been found to spread to lymph nodes and the lungs in up to 50% of cases with a 5-year survival rate of 10% to 30%.13

Conclusion

In summary, we describe a case of PMHE involving the lower leg in a 20-year-old man. These tumors often are multinodular and multiplanar, with the dermis and subcutaneous tissues being the most common areas affected. It has a high rate of local recurrence but rarely has distant metastasis. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, similar to other soft tissue tumors, can be difficult to diagnose on shave biopsy or superficial punch biopsy not extending into subcutaneous tissue. Deep incisional or punch biopsies are required to more definitively diagnose these types of tumors. The diagnosis of PMHE versus other soft tissue tumors requires correlation of histology and immunohistochemistry staining with clinical information and radiographic findings.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.

- Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. a fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382-1395.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190-201.

- Sheng W, Pan Y, Wang J. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: report of an additional case with aggressive clinical course. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:597-600.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48-57.

- Pradhan D, Schoedel K, McGough RL, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma of skin, bone and soft tissue—a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization study [published online November 2, 2017]. Hum Pathol. 2017. doi:0.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.023.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- McGinity M, Bartanusz V, Dengler B, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma) of the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(suppl 3):S506-S511.

- Stuart LN, Gardner JM, Lauer SR, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma, clinically mimicking dermatofibroma, diagnosed by skin biopsy in a 30-year-old man. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:909-913.

- Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:947-957.

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542-550.

- Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:222-227.

- Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211-215.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma (pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma). Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1088; author reply 1088-1089.

- Mirra JM, Kessler S, Bhuta S, et al. The fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma. a fibrohistiocytic/myoid cell lesion often confused with benign and malignant spindle cell tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:1382-1395.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95-104.

- Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: a distinctive, often multicentric tumor with indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:190-201.

- Sheng W, Pan Y, Wang J. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma: report of an additional case with aggressive clinical course. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:597-600.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:48-57.

- Pradhan D, Schoedel K, McGough RL, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma of skin, bone and soft tissue—a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization study [published online November 2, 2017]. Hum Pathol. 2017. doi:0.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.023.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- McGinity M, Bartanusz V, Dengler B, et al. Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (epithelioid sarcoma-like hemangioendothelioma, fibroma-like variant of epithelioid sarcoma) of the thoracic spine. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(suppl 3):S506-S511.

- Stuart LN, Gardner JM, Lauer SR, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma-like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma, clinically mimicking dermatofibroma, diagnosed by skin biopsy in a 30-year-old man. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:909-913.

- Amary MF, O’Donnell P, Berisha F, et al. Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma-like) hemangioendothelioma: characterization of five cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:947-957.

- Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Fletcher CD. Loss of INI1 expression is characteristic of both conventional and proximal-type epithelioid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:542-550.

- Chbani L, Guillou L, Terrier P, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 106 cases from the French Sarcoma Group. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;131:222-227.

- Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma of Enzinger. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:114-121.

- Requena L, Santonja C, Martinez-Amo JL, et al. Cutaneous epithelioid sarcoma like (pseudomyogenic) hemangioendothelioma: a little-known low-grade cutaneous vascular neoplasm. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:459-465.

- Trombetta D, Magnusson L, von Steyern FV, et al. Translocation t(7;19)(q22;q13)—a recurrent chromosome aberration in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma? Cancer Genet. 2011;204:211-215.

Practice Points

- Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (PMHE) is an uncommon vascular tumor that most often presents as multiple distinct nodules on the legs in young men.

- Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma has an unusual immunohistochemistry staining pattern, with positive staining for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CD31, and ERG but negative for CD34.

- Although local reoccurrence is common, PMHE metastasis is very uncommon.

Sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy may be best in locally advanced NSCLC with negative margins

Chemotherapy followed by radiation resulted in superior outcomes compared with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had negative margins after surgery and pN2 disease, according to results of a retrospective analysis.

“We also found that sequential therapy is becoming the more frequent practice pattern over time for patients with R0 pN2 disease, and our results support this practice,” wrote Samual Francis, MD, of the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, and his coauthors.

By contrast, there was no clear association between treatment sequence and survival among patients who had positive margins after surgery in this analysis, authors of the study reported (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Dec 13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4771).

The study included 1,024 patients in National Cancer Database who received a diagnosis of nonmetastatic NSCLC and received chemotherapy and radiation concurrently or sequentially after surgery. Of those patients, 747 had R0 resections and pN2 nodal status, and the remainder had R1 or R2 resections and pN0-N2 disease.

For patients with R0 pN2 NSCLC, median overall survival was 58.8 months for sequential chemotherapy followed by radiation, versus 40.4 months for concurrent chemoradiotherapy (log-rank P less than .001), data show.

That association between sequential treatment and improved overall survival remained significant even after propensity score matching (hazard ratio [HR], 1.35; P = .019), investigators reported.

However, for the remaining cohort of patients with positive margins regardless of nodal status, there was no significant difference in overall survival favoring either approach (42.6 months for sequential versus 38.5 months for concurrent; log-rank P = .42), they added, and no clear association between treatment approaches (HR 1.35; P = .19).

The analysis covered patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2012, the most recent data period available.

Investigators were also able to identify changes in practice patterns over time using this data set. Between 2006 and 2012, there was an increase in the use of sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy for patients with R0 resection and pN2 disease, and a decrease in the use of concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Conversely, they found that for patients with positive margins, there was an increase over time in use of the concurrent approach and decrease in the sequential approach.

“These findings suggest practice patterns have shifted toward concordance with consensus guideline recommendations over time,” Dr. Francis and his colleagues said in their report.

Current guidelines advocate for chemotherapy followed by postoperative radiotherapy for patients with negative margins and pN2 disease, but suggest concurrent chemoradiotherapy for patients with positive margins, they added.

Dr. Francis had no relationships to disclose. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Elekta, ProLung, Merit Medical Systems, and Bard Medical.

Chemotherapy followed by radiation resulted in superior outcomes compared with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had negative margins after surgery and pN2 disease, according to results of a retrospective analysis.

“We also found that sequential therapy is becoming the more frequent practice pattern over time for patients with R0 pN2 disease, and our results support this practice,” wrote Samual Francis, MD, of the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, and his coauthors.

By contrast, there was no clear association between treatment sequence and survival among patients who had positive margins after surgery in this analysis, authors of the study reported (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Dec 13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4771).

The study included 1,024 patients in National Cancer Database who received a diagnosis of nonmetastatic NSCLC and received chemotherapy and radiation concurrently or sequentially after surgery. Of those patients, 747 had R0 resections and pN2 nodal status, and the remainder had R1 or R2 resections and pN0-N2 disease.

For patients with R0 pN2 NSCLC, median overall survival was 58.8 months for sequential chemotherapy followed by radiation, versus 40.4 months for concurrent chemoradiotherapy (log-rank P less than .001), data show.

That association between sequential treatment and improved overall survival remained significant even after propensity score matching (hazard ratio [HR], 1.35; P = .019), investigators reported.

However, for the remaining cohort of patients with positive margins regardless of nodal status, there was no significant difference in overall survival favoring either approach (42.6 months for sequential versus 38.5 months for concurrent; log-rank P = .42), they added, and no clear association between treatment approaches (HR 1.35; P = .19).

The analysis covered patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2012, the most recent data period available.

Investigators were also able to identify changes in practice patterns over time using this data set. Between 2006 and 2012, there was an increase in the use of sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy for patients with R0 resection and pN2 disease, and a decrease in the use of concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Conversely, they found that for patients with positive margins, there was an increase over time in use of the concurrent approach and decrease in the sequential approach.

“These findings suggest practice patterns have shifted toward concordance with consensus guideline recommendations over time,” Dr. Francis and his colleagues said in their report.

Current guidelines advocate for chemotherapy followed by postoperative radiotherapy for patients with negative margins and pN2 disease, but suggest concurrent chemoradiotherapy for patients with positive margins, they added.

Dr. Francis had no relationships to disclose. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Elekta, ProLung, Merit Medical Systems, and Bard Medical.

Chemotherapy followed by radiation resulted in superior outcomes compared with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had negative margins after surgery and pN2 disease, according to results of a retrospective analysis.

“We also found that sequential therapy is becoming the more frequent practice pattern over time for patients with R0 pN2 disease, and our results support this practice,” wrote Samual Francis, MD, of the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, and his coauthors.

By contrast, there was no clear association between treatment sequence and survival among patients who had positive margins after surgery in this analysis, authors of the study reported (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Dec 13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4771).

The study included 1,024 patients in National Cancer Database who received a diagnosis of nonmetastatic NSCLC and received chemotherapy and radiation concurrently or sequentially after surgery. Of those patients, 747 had R0 resections and pN2 nodal status, and the remainder had R1 or R2 resections and pN0-N2 disease.

For patients with R0 pN2 NSCLC, median overall survival was 58.8 months for sequential chemotherapy followed by radiation, versus 40.4 months for concurrent chemoradiotherapy (log-rank P less than .001), data show.

That association between sequential treatment and improved overall survival remained significant even after propensity score matching (hazard ratio [HR], 1.35; P = .019), investigators reported.

However, for the remaining cohort of patients with positive margins regardless of nodal status, there was no significant difference in overall survival favoring either approach (42.6 months for sequential versus 38.5 months for concurrent; log-rank P = .42), they added, and no clear association between treatment approaches (HR 1.35; P = .19).

The analysis covered patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2012, the most recent data period available.

Investigators were also able to identify changes in practice patterns over time using this data set. Between 2006 and 2012, there was an increase in the use of sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy for patients with R0 resection and pN2 disease, and a decrease in the use of concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Conversely, they found that for patients with positive margins, there was an increase over time in use of the concurrent approach and decrease in the sequential approach.

“These findings suggest practice patterns have shifted toward concordance with consensus guideline recommendations over time,” Dr. Francis and his colleagues said in their report.

Current guidelines advocate for chemotherapy followed by postoperative radiotherapy for patients with negative margins and pN2 disease, but suggest concurrent chemoradiotherapy for patients with positive margins, they added.

Dr. Francis had no relationships to disclose. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Elekta, ProLung, Merit Medical Systems, and Bard Medical.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: In patients with pN2 non–small-cell lung cancer who have negative margins after surgery, sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy provided superior outcomes compared with concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Major finding: Median overall survival was 58.8 months for the sequential approach and 40.4 months for concurrent (log-rank P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective analysis including 1,024 patients with nonmetastatic NSCLC who received chemotherapy and radiation concurrently or sequentially after surgery.

Disclosures: Study authors reported disclosures related to Elekta, ProLung, Merit Medical Systems, and Bard Medical.

Sleepless in adolescence

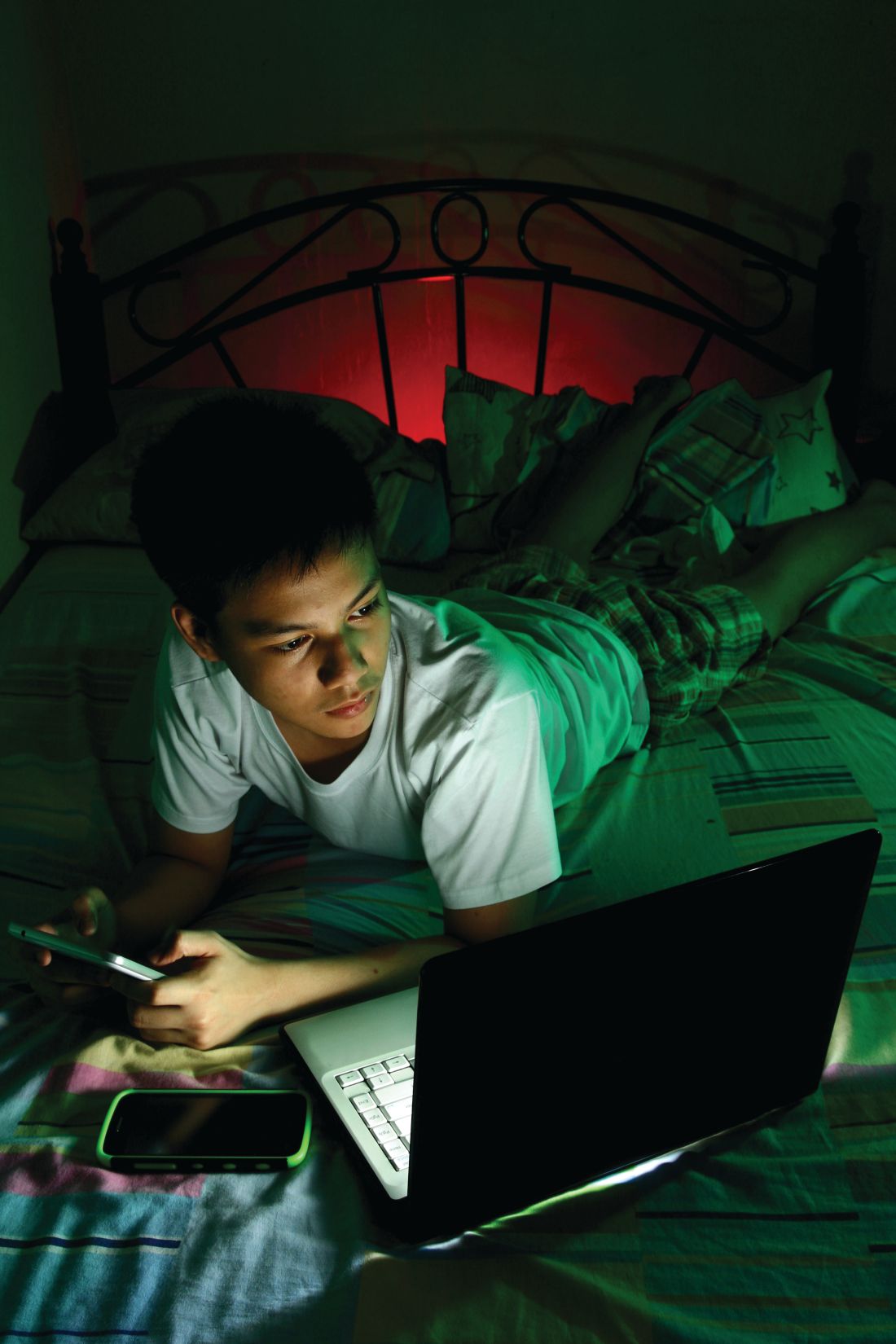

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients with Diabetes

The Cardiovascular Insights for Primary Care Physicians eNewsletter Series summarizes key information and data on common cardiovascular issues facing primary care physicians today.

Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients with Diabetes is the fifth eNewsletter in this series.

The Cardiovascular Insights for Primary Care Physicians eNewsletter Series summarizes key information and data on common cardiovascular issues facing primary care physicians today.

Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients with Diabetes is the fifth eNewsletter in this series.

The Cardiovascular Insights for Primary Care Physicians eNewsletter Series summarizes key information and data on common cardiovascular issues facing primary care physicians today.

Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients with Diabetes is the fifth eNewsletter in this series.

HERCULES: Caplacizumab improved platelet response in aTTP

ATLANTA – Adding caplacizumab to standard therapy for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP) significantly improved platelet response and prevented recurrent episodes in an international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 placebo-controlled trial.

“Patients were 55% more likely to achieve normalization of platelet count in the caplacizumab group, and this was highly significant,” Marie Scully, MD, said during a late-breaking presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“So far, phase 2 and phase 3 studies confirm no deaths in patients treated with caplacizumab,” said Dr. Scully of University College London Hospitals NHS Trust.

Acquired TTP is an acute, life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy that occurs when inhibitory autoantibodies cause a deficiency of ADAMTS13, an enzyme that cleaves von Willebrand factor (vWF). Inadequate levels of ADAMTS13 activity lead to the formation of ultra-large vWF multimers, platelet strings, and microthrombi. Caplacizumab is a humanized immunoglobulin that helps stop this process by binding the A1 domain of vWF.

“Caplacizumab addresses the pathophysiological platelet aggregation that leads to the formation of microthrombi,” Dr. Scully said.

In this phase 3 trial (HERCULES), 145 patients who had received plasma exchange (PE) at least once for an acute episode of aTTP were randomly assigned to receive caplacizumab or placebo injections plus daily PE and corticosteroids. Caplacizumab (10-mg) therapy consisted of one IV bolus followed by subcutaneous treatment for 30 days. Patients whose ADAMTS13 activity remained below 10% were able to continue treatment for another 28 days, after which all patients were followed for another 28 days without treatment.

At any given time, platelet normalization was 55% more likely with caplacizumab (10 mg) than placebo (platelet normalization rate ratio, 1.55; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-2.20; P less than .01).

Rates of a key combined secondary endpoint – aTTP-related death/recurrence/major thrombotic events – were 12.7% with caplacizumab and 49.3% with placebo (P less than .0001).

Rates of major thrombotic events were 8% in each arm, and deaths were rare overall, meaning that the difference in rates of recurrence drove most of the effect on the combined secondary endpoint. However, patients who received caplacizumab also received 41% less plasma and had 38% fewer days of PE, 65% fewer days in the intensive care unit, and 31% fewer days in the hospital than patients in the placebo arm.

Refractory aTTP affected 4.2% of placebo patients and no caplacizumab patients, which trended toward statistical significance (P = .057). Caplacizumab therapy also led to a faster normalization of several markers of organ damage, including lactate dehydrogenase, cardiac troponin 1, and serum creatinine.

Safety findings reflected earlier-phase studies and caplacizumab’s mechanism of action, Dr. Scully said. Nearly all trial participants experienced at least one treatment-emergent adverse event. Such events led 7% of patients to stop caplacizumab and 12% to stop placebo. Caplacizumab was associated with a range of bleeding-related events, most commonly epistaxis (23.9 vs. 1.4% with placebo), gingival bleeding (11.3% vs. 0%), bruising (7.0% vs. 4.1%), and hematuria (5.6% vs. 1.4%).

Patients in both arms tended to be in their 40s and two-thirds were female. At baseline, about 85% had less than 10% ADAMTS13 activity, and about 40% had severe aTTP (French severity scores of at least 3 or severe neurologic or cardiac involvement).

“Most [66%] patients in the caplacizumab group presented with de novo aTTP, and this is relevant because patients who are in their first episode are much harder to treat,” Dr. Scully said. About half of placebo patients had de novo disease.

In July 2017, caplacizumab received a fast-track designation from the Food and Drug Administration for aTTP after a phase 2 trial showed that platelet counts normalized 39% faster with caplacizumab versus placebo plus standard of care (P = .005). Of eight patients in that study who relapsed within a month of stopping caplacizumab, seven still had less than 10% ADAMTS13 activity, “suggesting unresolved autoimmune activity,” the investigators wrote at the time in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016;374:511-22).

Dr. Scully reported similar findings in the phase 3 HERCULES trial, noting that all patients had ADAMTS13 levels less than 5% on stopping caplacizumab.

Ablynx provided funding for the study. Dr. Scully reported financial relationships with Ablynx, Shire, Novartis, and Alexion.

SOURCE: Scully M et al., ASH 2017 Abstract LBA-1.

ATLANTA – Adding caplacizumab to standard therapy for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP) significantly improved platelet response and prevented recurrent episodes in an international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 placebo-controlled trial.

“Patients were 55% more likely to achieve normalization of platelet count in the caplacizumab group, and this was highly significant,” Marie Scully, MD, said during a late-breaking presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“So far, phase 2 and phase 3 studies confirm no deaths in patients treated with caplacizumab,” said Dr. Scully of University College London Hospitals NHS Trust.

Acquired TTP is an acute, life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy that occurs when inhibitory autoantibodies cause a deficiency of ADAMTS13, an enzyme that cleaves von Willebrand factor (vWF). Inadequate levels of ADAMTS13 activity lead to the formation of ultra-large vWF multimers, platelet strings, and microthrombi. Caplacizumab is a humanized immunoglobulin that helps stop this process by binding the A1 domain of vWF.

“Caplacizumab addresses the pathophysiological platelet aggregation that leads to the formation of microthrombi,” Dr. Scully said.