User login

Nearly 10% of patients with candidemia had CDI

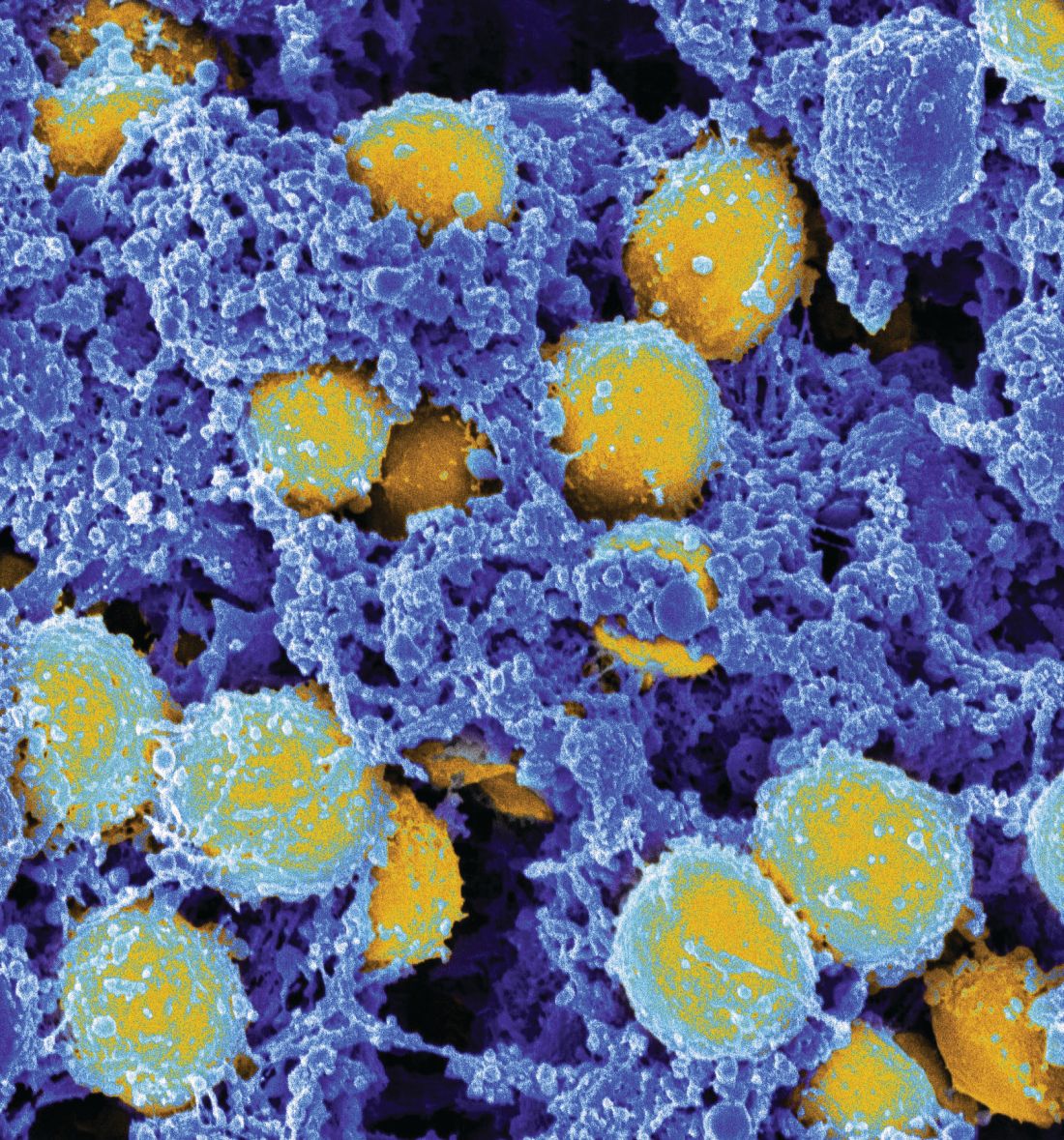

SAN DIEGO – Nearly one in ten adults hospitalized with candidemia had Clostridium difficile coinfections in a large multistate study.

“,” Sharon Tsay, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “In patients with CDI, one in 100 developed candidemia, but in patients with candidemia, nearly one in 10 had CDI,” she said. Patients with diabetes, hemodialysis, solid organ transplantation, or a prior recent hospital stay were significantly more likely to have a CDI coinfection even after the researchers controlled for potential confounders, she reported.

Both candidemia and CDI are serious health care–associated infections that disproportionately affect older, severely ill, and immunosuppressed patients, noted Dr. Tsay, an Epidemic Intelligence Service officer in the mycotic diseases branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. Every year in the United States, about 50,000 individuals are hospitalized with candidemia, and about 30% die within 30 days of diagnosis. The prevalence of CDI is about tenfold higher, and 30-day mortality rates range between about 1% and 9%.

To understand why candidemia and CDI occur together, consider the effects of oral vancomycin therapy, Dr. Tsay said. Antibiotic pressure disrupts normal gut flora, leading to decreased immunity and Candida colonization. Disrupting the gut microbiome also increases the risk of CDI, which can damage gut mucosa, especially in hypervirulent cases such as C. difficile ribotype 027. Vancomycin can also directly damage the gut mucosa, after which Candida can translocate into the bloodstream.

To better characterize CDI and candidemia coinfections in the United States, Dr. Tsay and her associates analyzed data from CDC’s Emerging Infections Program, which tracks infections of high public health significance in 10 states across the country. Among 2,129 patients with a positive blood culture for Candida from 2014 through 2016, 193 (9%) had a diagnosis of CDI within 90 days. Two-thirds of CDI cases preceded candidemia (median, 10 days) and one-third occurred afterward (median, 7 days). Rates of 30-day mortality rates were 25% in patients with and without CDI. For both groups, Candida albicans was the most commonly identified species, followed by C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis.

A multivariate model identified four risk factors for CDI in patients with candidemia – solid organ transplantation (odds ratio, 3.0), hemodialysis (OR, 1.8), prior hospital stay (OR, 1.7), and diabetes (OR, 1.4). Data were limited to case report forms and did not include information about CDI severity or treatment, Dr. Tsay said.

Dr. Tsay and her associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Nearly one in ten adults hospitalized with candidemia had Clostridium difficile coinfections in a large multistate study.

“,” Sharon Tsay, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “In patients with CDI, one in 100 developed candidemia, but in patients with candidemia, nearly one in 10 had CDI,” she said. Patients with diabetes, hemodialysis, solid organ transplantation, or a prior recent hospital stay were significantly more likely to have a CDI coinfection even after the researchers controlled for potential confounders, she reported.

Both candidemia and CDI are serious health care–associated infections that disproportionately affect older, severely ill, and immunosuppressed patients, noted Dr. Tsay, an Epidemic Intelligence Service officer in the mycotic diseases branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. Every year in the United States, about 50,000 individuals are hospitalized with candidemia, and about 30% die within 30 days of diagnosis. The prevalence of CDI is about tenfold higher, and 30-day mortality rates range between about 1% and 9%.

To understand why candidemia and CDI occur together, consider the effects of oral vancomycin therapy, Dr. Tsay said. Antibiotic pressure disrupts normal gut flora, leading to decreased immunity and Candida colonization. Disrupting the gut microbiome also increases the risk of CDI, which can damage gut mucosa, especially in hypervirulent cases such as C. difficile ribotype 027. Vancomycin can also directly damage the gut mucosa, after which Candida can translocate into the bloodstream.

To better characterize CDI and candidemia coinfections in the United States, Dr. Tsay and her associates analyzed data from CDC’s Emerging Infections Program, which tracks infections of high public health significance in 10 states across the country. Among 2,129 patients with a positive blood culture for Candida from 2014 through 2016, 193 (9%) had a diagnosis of CDI within 90 days. Two-thirds of CDI cases preceded candidemia (median, 10 days) and one-third occurred afterward (median, 7 days). Rates of 30-day mortality rates were 25% in patients with and without CDI. For both groups, Candida albicans was the most commonly identified species, followed by C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis.

A multivariate model identified four risk factors for CDI in patients with candidemia – solid organ transplantation (odds ratio, 3.0), hemodialysis (OR, 1.8), prior hospital stay (OR, 1.7), and diabetes (OR, 1.4). Data were limited to case report forms and did not include information about CDI severity or treatment, Dr. Tsay said.

Dr. Tsay and her associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Nearly one in ten adults hospitalized with candidemia had Clostridium difficile coinfections in a large multistate study.

“,” Sharon Tsay, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “In patients with CDI, one in 100 developed candidemia, but in patients with candidemia, nearly one in 10 had CDI,” she said. Patients with diabetes, hemodialysis, solid organ transplantation, or a prior recent hospital stay were significantly more likely to have a CDI coinfection even after the researchers controlled for potential confounders, she reported.

Both candidemia and CDI are serious health care–associated infections that disproportionately affect older, severely ill, and immunosuppressed patients, noted Dr. Tsay, an Epidemic Intelligence Service officer in the mycotic diseases branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. Every year in the United States, about 50,000 individuals are hospitalized with candidemia, and about 30% die within 30 days of diagnosis. The prevalence of CDI is about tenfold higher, and 30-day mortality rates range between about 1% and 9%.

To understand why candidemia and CDI occur together, consider the effects of oral vancomycin therapy, Dr. Tsay said. Antibiotic pressure disrupts normal gut flora, leading to decreased immunity and Candida colonization. Disrupting the gut microbiome also increases the risk of CDI, which can damage gut mucosa, especially in hypervirulent cases such as C. difficile ribotype 027. Vancomycin can also directly damage the gut mucosa, after which Candida can translocate into the bloodstream.

To better characterize CDI and candidemia coinfections in the United States, Dr. Tsay and her associates analyzed data from CDC’s Emerging Infections Program, which tracks infections of high public health significance in 10 states across the country. Among 2,129 patients with a positive blood culture for Candida from 2014 through 2016, 193 (9%) had a diagnosis of CDI within 90 days. Two-thirds of CDI cases preceded candidemia (median, 10 days) and one-third occurred afterward (median, 7 days). Rates of 30-day mortality rates were 25% in patients with and without CDI. For both groups, Candida albicans was the most commonly identified species, followed by C. glabrata and C. parapsilosis.

A multivariate model identified four risk factors for CDI in patients with candidemia – solid organ transplantation (odds ratio, 3.0), hemodialysis (OR, 1.8), prior hospital stay (OR, 1.7), and diabetes (OR, 1.4). Data were limited to case report forms and did not include information about CDI severity or treatment, Dr. Tsay said.

Dr. Tsay and her associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT IDWEEK 2017

Key clinical point: Look for candidemia and Clostridium difficile infection occurring together.

Major finding: Among 2,129 patients with a positive blood culture for Candida, 193 (9%) had a diagnosis of CDI within 90 days. Risk factors for coinfection included solid organ transplant, hemodialysis, recent hospital stay, and diabetes.

Data source: A multistate analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control’s Emerging Infections Program.

Disclosures: Dr. Tsay and her associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

Research progress in a short time window

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

My research experience this summer has been full of learning both clinical and academic aspects of medicine. I had the opportunity to observe my mentor plus other hospitalists rounding on patients, and sit in on presentations to hear about the spectacular work that different faculty members are implementing. This has helped me gain a better understanding of hospital medicine, and really sparked my interest in the field.

I love that hospitalists can play a major role in treating the sickest of patients, while at the same time work to investigate ways to make the patients’ time at a hospital a better experience.

My mentor, Dr. Patrick Brady, has been very helpful giving me insight on research methods for our project and how best to use the data we have collected. We were able to make some adjustments in our exclusion criteria for the patients included in the retrospective case control study, so that I have time to collect several clinical characteristics of each patient who underwent an emergency transfer. While going over several emergency transfer cases, I have learned quite a bit of clinical information. One example of what I’ve learned involves rapid sequence intubation drugs when endotracheal intubation procedures are done. The procedure requires quick onset sedatives and pain medications in addition to neuromuscular blocking agents to rapidly numb and sedate the patient in order to put in the tube.

We are wrapping up this week and beginning to run some simple statistical analyses on the data. I hope to have some insight on the incidence and descriptors of emergency transfer cases in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital by the end of the week. I am preparing to begin writing and creating presentations for dissemination.

Reflecting back on my work this summer, I am encouraged by the amount of progress that I was able to make in the short period of time. Completing a research project over a nine-week period is a very challenging task as it comes with many limitations. However, Dr. Brady helped me realize that important questions can still be answered if the project is designed efficiently. I could see myself doing similar research in my future as a physician. I very much like the idea of studying what is clinically right in front of you.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

My research experience this summer has been full of learning both clinical and academic aspects of medicine. I had the opportunity to observe my mentor plus other hospitalists rounding on patients, and sit in on presentations to hear about the spectacular work that different faculty members are implementing. This has helped me gain a better understanding of hospital medicine, and really sparked my interest in the field.

I love that hospitalists can play a major role in treating the sickest of patients, while at the same time work to investigate ways to make the patients’ time at a hospital a better experience.

My mentor, Dr. Patrick Brady, has been very helpful giving me insight on research methods for our project and how best to use the data we have collected. We were able to make some adjustments in our exclusion criteria for the patients included in the retrospective case control study, so that I have time to collect several clinical characteristics of each patient who underwent an emergency transfer. While going over several emergency transfer cases, I have learned quite a bit of clinical information. One example of what I’ve learned involves rapid sequence intubation drugs when endotracheal intubation procedures are done. The procedure requires quick onset sedatives and pain medications in addition to neuromuscular blocking agents to rapidly numb and sedate the patient in order to put in the tube.

We are wrapping up this week and beginning to run some simple statistical analyses on the data. I hope to have some insight on the incidence and descriptors of emergency transfer cases in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital by the end of the week. I am preparing to begin writing and creating presentations for dissemination.

Reflecting back on my work this summer, I am encouraged by the amount of progress that I was able to make in the short period of time. Completing a research project over a nine-week period is a very challenging task as it comes with many limitations. However, Dr. Brady helped me realize that important questions can still be answered if the project is designed efficiently. I could see myself doing similar research in my future as a physician. I very much like the idea of studying what is clinically right in front of you.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

My research experience this summer has been full of learning both clinical and academic aspects of medicine. I had the opportunity to observe my mentor plus other hospitalists rounding on patients, and sit in on presentations to hear about the spectacular work that different faculty members are implementing. This has helped me gain a better understanding of hospital medicine, and really sparked my interest in the field.

I love that hospitalists can play a major role in treating the sickest of patients, while at the same time work to investigate ways to make the patients’ time at a hospital a better experience.

My mentor, Dr. Patrick Brady, has been very helpful giving me insight on research methods for our project and how best to use the data we have collected. We were able to make some adjustments in our exclusion criteria for the patients included in the retrospective case control study, so that I have time to collect several clinical characteristics of each patient who underwent an emergency transfer. While going over several emergency transfer cases, I have learned quite a bit of clinical information. One example of what I’ve learned involves rapid sequence intubation drugs when endotracheal intubation procedures are done. The procedure requires quick onset sedatives and pain medications in addition to neuromuscular blocking agents to rapidly numb and sedate the patient in order to put in the tube.

We are wrapping up this week and beginning to run some simple statistical analyses on the data. I hope to have some insight on the incidence and descriptors of emergency transfer cases in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital by the end of the week. I am preparing to begin writing and creating presentations for dissemination.

Reflecting back on my work this summer, I am encouraged by the amount of progress that I was able to make in the short period of time. Completing a research project over a nine-week period is a very challenging task as it comes with many limitations. However, Dr. Brady helped me realize that important questions can still be answered if the project is designed efficiently. I could see myself doing similar research in my future as a physician. I very much like the idea of studying what is clinically right in front of you.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Thirty-one percent of multidrug-resistant infections were community acquired

SAN DIEGO – Thirty-one percent of multidrug-resistant infections were acquired from the community in a prospective single-center study of a regional hospital.

“Multidrug-resistant organisms have escaped the hospital,” Nicholas A. Turner, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and his associates wrote in a poster presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Community acquisition of multidrug-resistant organisms [MDROs] is increasing, not just within referral centers but also community hospitals. Providers will need to be increasingly aware of this trend.”

Infections of MDROs cause about 2,000,000 illnesses and 23,000 deaths annually in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Until recently, MDROs were considered a plague of hospitals. Amid reports of increasing levels of community acquisition, the researchers studied adults admitted to a 202-bed regional hospital between 2013 and 2016. They defined MDROs as infections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), gram-negative bacteria resistant to more than three antimicrobial classes, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), or diarrhea with a positive stool culture for Clostridium difficile.

A total of 285 patients had MDROs. Clostridium difficile (45%) and MRSA (35%) were most common. In all, 88 (31%) MDROs were community-acquired – that is, diagnosed within 48 hours of admission in patients who were not on dialysis, did not live in a long-term care facility, and had not been hospitalized for more than 48 hours in the past 90 days. A total of 36% of MRSA and multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections were community acquired, as were 25% of Clostridium difficile infections. There were only 10 VRE infections, of which none were community-acquired.

After the researchers controlled for clinical and demographic variables, the only significant predictor of community-acquired MDRO was cancer (odds ratio [OR], 2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-5.2). Surgery within the previous 12 months was significantly associated with hospital-acquired MDRO (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.05-0.5).

Traditional risk factors for community-acquired MRSA or C. difficile infection did not achieve statistical significance in the multivariable analysis, the researchers noted. “Similar to data from large tertiary care centers, our findings suggest that MDROs are increasingly acquired in the community setting, even at smaller regional hospitals,” they concluded. “Further study is needed to track the expansion of MDROs in the community setting.”

Dr. Turner reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Thirty-one percent of multidrug-resistant infections were acquired from the community in a prospective single-center study of a regional hospital.

“Multidrug-resistant organisms have escaped the hospital,” Nicholas A. Turner, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and his associates wrote in a poster presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Community acquisition of multidrug-resistant organisms [MDROs] is increasing, not just within referral centers but also community hospitals. Providers will need to be increasingly aware of this trend.”

Infections of MDROs cause about 2,000,000 illnesses and 23,000 deaths annually in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Until recently, MDROs were considered a plague of hospitals. Amid reports of increasing levels of community acquisition, the researchers studied adults admitted to a 202-bed regional hospital between 2013 and 2016. They defined MDROs as infections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), gram-negative bacteria resistant to more than three antimicrobial classes, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), or diarrhea with a positive stool culture for Clostridium difficile.

A total of 285 patients had MDROs. Clostridium difficile (45%) and MRSA (35%) were most common. In all, 88 (31%) MDROs were community-acquired – that is, diagnosed within 48 hours of admission in patients who were not on dialysis, did not live in a long-term care facility, and had not been hospitalized for more than 48 hours in the past 90 days. A total of 36% of MRSA and multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections were community acquired, as were 25% of Clostridium difficile infections. There were only 10 VRE infections, of which none were community-acquired.

After the researchers controlled for clinical and demographic variables, the only significant predictor of community-acquired MDRO was cancer (odds ratio [OR], 2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-5.2). Surgery within the previous 12 months was significantly associated with hospital-acquired MDRO (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.05-0.5).

Traditional risk factors for community-acquired MRSA or C. difficile infection did not achieve statistical significance in the multivariable analysis, the researchers noted. “Similar to data from large tertiary care centers, our findings suggest that MDROs are increasingly acquired in the community setting, even at smaller regional hospitals,” they concluded. “Further study is needed to track the expansion of MDROs in the community setting.”

Dr. Turner reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Thirty-one percent of multidrug-resistant infections were acquired from the community in a prospective single-center study of a regional hospital.

“Multidrug-resistant organisms have escaped the hospital,” Nicholas A. Turner, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and his associates wrote in a poster presented at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “Community acquisition of multidrug-resistant organisms [MDROs] is increasing, not just within referral centers but also community hospitals. Providers will need to be increasingly aware of this trend.”

Infections of MDROs cause about 2,000,000 illnesses and 23,000 deaths annually in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Until recently, MDROs were considered a plague of hospitals. Amid reports of increasing levels of community acquisition, the researchers studied adults admitted to a 202-bed regional hospital between 2013 and 2016. They defined MDROs as infections of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), gram-negative bacteria resistant to more than three antimicrobial classes, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), or diarrhea with a positive stool culture for Clostridium difficile.

A total of 285 patients had MDROs. Clostridium difficile (45%) and MRSA (35%) were most common. In all, 88 (31%) MDROs were community-acquired – that is, diagnosed within 48 hours of admission in patients who were not on dialysis, did not live in a long-term care facility, and had not been hospitalized for more than 48 hours in the past 90 days. A total of 36% of MRSA and multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections were community acquired, as were 25% of Clostridium difficile infections. There were only 10 VRE infections, of which none were community-acquired.

After the researchers controlled for clinical and demographic variables, the only significant predictor of community-acquired MDRO was cancer (odds ratio [OR], 2.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.02-5.2). Surgery within the previous 12 months was significantly associated with hospital-acquired MDRO (OR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.05-0.5).

Traditional risk factors for community-acquired MRSA or C. difficile infection did not achieve statistical significance in the multivariable analysis, the researchers noted. “Similar to data from large tertiary care centers, our findings suggest that MDROs are increasingly acquired in the community setting, even at smaller regional hospitals,” they concluded. “Further study is needed to track the expansion of MDROs in the community setting.”

Dr. Turner reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT IDWEEK 2017

Key clinical point: Multidrug resistant infections are increasingly being acquired in communities.

Major finding:

Data source: A prospective study of 285 patients with multidrug-resistant infections at a 202-bed hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Turner reported having no conflicts of interest.

Simple rule boosted yield of molecular tests for enteric pathogens

SAN DIEGO – For adult outpatients with diarrhea, consider limiting molecular testing for enteric pathogens to cases in which patients are immunocompromised or have abdominal pain or fever without vomiting, said Stephen Clark, MD.

“This simple clinical decision rule would reduce testing by 43% while retaining a high sensitivity for clinically relevant infections,” Dr. Clark said at an annual meeting on infectious diseases. In a single-center retrospective cohort study, the decision rule covered 96% of patients with molecular evidence of clinically relevant pathogens.

Several Food and Drug and Administration–approved molecular diagnostic panels for enteric pathogens have become available in the United States during the past 4 years. These panels are fast and sensitive, but costly and not clinically relevant unless they detect a pathogen that merits a change in treatment, such as titrating immunosuppressive drugs or prescribing a course of antimicrobial therapy, said Dr. Clark, a third-year resident at the department of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Physicians at the University of Virginia often order the FilmArray Gastrointestinal Panel (Biofire Diagnostics) for adult outpatients, especially if they have persistent diarrhea, Dr. Clark said. However, medical records from 452 tested patients showed that only 88 (20%) tested positive for an enteric pathogen and only 4% had an infection clearly meriting antimicrobial therapy. Therefore, the researchers sought predictors of clinically relevant FilmArray results.

Among 376 immunocompetent patients in this cohort, only 12 (3%) had a treatable pathogen detected. None of these 12 patients reported vomiting, while 11 (92%) reported fever or abdominal pain without vomiting, compared with only 47% of immunocompetent patients with no treatable pathogen (P = .002). For immunocompetent patients, the combination of subjective fever or abdominal pain without vomiting was the only demographic or clinical predictor of a clinically relevant positive test result, Dr. Clark said.

Importantly, the FilmArray GI panel showed a much higher clinical yield (about 20%) in immunocompromised patients, who often lacked clinical signs of gastrointestinal infection. “Thinking about this overall, we would recommend testing if patients are either immunocompromised, or if they have abdominal pain or fever in the absence of vomiting,” Dr. Clark said. For this cohort, this decision rule had a sensitivity of 96% (95% confidence interval [CI], 81%-100%) and a negative predictive value of 99% (95% CI, 97%-100%). Specificity was only 45% (95% CI, 41%-51%), but “the aim of this rule was more to help clinicians think about whether it’s possible that there could be a detection, instead of pinpointing what it might be,” Dr. Clark said.

Applying guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology did not increase testing efficiency, Dr. Clark said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers are now reviewing another 6 months of medical records to create a validation cohort for the decision rule.

Dr. Clark and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – For adult outpatients with diarrhea, consider limiting molecular testing for enteric pathogens to cases in which patients are immunocompromised or have abdominal pain or fever without vomiting, said Stephen Clark, MD.

“This simple clinical decision rule would reduce testing by 43% while retaining a high sensitivity for clinically relevant infections,” Dr. Clark said at an annual meeting on infectious diseases. In a single-center retrospective cohort study, the decision rule covered 96% of patients with molecular evidence of clinically relevant pathogens.

Several Food and Drug and Administration–approved molecular diagnostic panels for enteric pathogens have become available in the United States during the past 4 years. These panels are fast and sensitive, but costly and not clinically relevant unless they detect a pathogen that merits a change in treatment, such as titrating immunosuppressive drugs or prescribing a course of antimicrobial therapy, said Dr. Clark, a third-year resident at the department of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Physicians at the University of Virginia often order the FilmArray Gastrointestinal Panel (Biofire Diagnostics) for adult outpatients, especially if they have persistent diarrhea, Dr. Clark said. However, medical records from 452 tested patients showed that only 88 (20%) tested positive for an enteric pathogen and only 4% had an infection clearly meriting antimicrobial therapy. Therefore, the researchers sought predictors of clinically relevant FilmArray results.

Among 376 immunocompetent patients in this cohort, only 12 (3%) had a treatable pathogen detected. None of these 12 patients reported vomiting, while 11 (92%) reported fever or abdominal pain without vomiting, compared with only 47% of immunocompetent patients with no treatable pathogen (P = .002). For immunocompetent patients, the combination of subjective fever or abdominal pain without vomiting was the only demographic or clinical predictor of a clinically relevant positive test result, Dr. Clark said.

Importantly, the FilmArray GI panel showed a much higher clinical yield (about 20%) in immunocompromised patients, who often lacked clinical signs of gastrointestinal infection. “Thinking about this overall, we would recommend testing if patients are either immunocompromised, or if they have abdominal pain or fever in the absence of vomiting,” Dr. Clark said. For this cohort, this decision rule had a sensitivity of 96% (95% confidence interval [CI], 81%-100%) and a negative predictive value of 99% (95% CI, 97%-100%). Specificity was only 45% (95% CI, 41%-51%), but “the aim of this rule was more to help clinicians think about whether it’s possible that there could be a detection, instead of pinpointing what it might be,” Dr. Clark said.

Applying guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology did not increase testing efficiency, Dr. Clark said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers are now reviewing another 6 months of medical records to create a validation cohort for the decision rule.

Dr. Clark and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – For adult outpatients with diarrhea, consider limiting molecular testing for enteric pathogens to cases in which patients are immunocompromised or have abdominal pain or fever without vomiting, said Stephen Clark, MD.

“This simple clinical decision rule would reduce testing by 43% while retaining a high sensitivity for clinically relevant infections,” Dr. Clark said at an annual meeting on infectious diseases. In a single-center retrospective cohort study, the decision rule covered 96% of patients with molecular evidence of clinically relevant pathogens.

Several Food and Drug and Administration–approved molecular diagnostic panels for enteric pathogens have become available in the United States during the past 4 years. These panels are fast and sensitive, but costly and not clinically relevant unless they detect a pathogen that merits a change in treatment, such as titrating immunosuppressive drugs or prescribing a course of antimicrobial therapy, said Dr. Clark, a third-year resident at the department of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Physicians at the University of Virginia often order the FilmArray Gastrointestinal Panel (Biofire Diagnostics) for adult outpatients, especially if they have persistent diarrhea, Dr. Clark said. However, medical records from 452 tested patients showed that only 88 (20%) tested positive for an enteric pathogen and only 4% had an infection clearly meriting antimicrobial therapy. Therefore, the researchers sought predictors of clinically relevant FilmArray results.

Among 376 immunocompetent patients in this cohort, only 12 (3%) had a treatable pathogen detected. None of these 12 patients reported vomiting, while 11 (92%) reported fever or abdominal pain without vomiting, compared with only 47% of immunocompetent patients with no treatable pathogen (P = .002). For immunocompetent patients, the combination of subjective fever or abdominal pain without vomiting was the only demographic or clinical predictor of a clinically relevant positive test result, Dr. Clark said.

Importantly, the FilmArray GI panel showed a much higher clinical yield (about 20%) in immunocompromised patients, who often lacked clinical signs of gastrointestinal infection. “Thinking about this overall, we would recommend testing if patients are either immunocompromised, or if they have abdominal pain or fever in the absence of vomiting,” Dr. Clark said. For this cohort, this decision rule had a sensitivity of 96% (95% confidence interval [CI], 81%-100%) and a negative predictive value of 99% (95% CI, 97%-100%). Specificity was only 45% (95% CI, 41%-51%), but “the aim of this rule was more to help clinicians think about whether it’s possible that there could be a detection, instead of pinpointing what it might be,” Dr. Clark said.

Applying guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology did not increase testing efficiency, Dr. Clark said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers are now reviewing another 6 months of medical records to create a validation cohort for the decision rule.

Dr. Clark and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT IDWEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: This approach would have identified 26 of 27 (96%) infections of clinically relevant pathogens, while cutting testing by 43%.

Data source: A single-center retrospective study of 452 adult outpatients with diarrhea.

Disclosures: Dr. Clark and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest.

Wait at least 2 days to replace central venous catheters in patients with candidemia

SAN DIEGO – Wait at least 2 days before replacing central venous catheters (CVC) in patients with catheter-associated candidemia, according to the results of a single-center retrospective cohort study of 228 patients.

Waiting less than 2 days to replace a CVC increased the odds of 30-day mortality nearly sixfold among patients with catheter-related bloodstream infections due to candidemia, even after controlling for potential confounders, Takahiro Matsuo, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. No other factor significantly predicted mortality in univariate or multivariate analyses, he said. “This is the first study to demonstrate the optimal timing of central venous catheter replacement in catheter-related [bloodstream infection] due to Candida.”

Invasive candidiasis is associated with mortality rates of up to 50%, noted Dr. Matsuo, who is a fellow in infectious diseases at St. Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo. Antifungal therapy improves outcomes, and most physicians agree that removing a CVC does, too. To better pinpoint optimal timing of catheter replacement, Dr. Matsuo and his associates examined risk factors for 30-day mortality among patients with candidemia who were treated at St. Luke’s between 2004 and 2015.

Among 228 patients with candidemia, 166 had CVCs, and 144 had their CVC removed. Among 71 patients who needed their CVC replaced, 15 died within 30 days. Central venous catheters were replaced less than 2 days after removal in 87% of patients who died and in 54% of survivors (P = .04). The association remained statistically significant after the researchers accounted for potential confounders (adjusted odds ratio, 5.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-29.7; P = .03).

Patients who died within 30 days of CVC replacement also were more likely to have hematologic malignancies (20% versus 4%), diabetes (13% vs. 11%), to be on hemodialysis (27% vs. 16%), and to have a history of recent corticosteroid exposure (20% versus 11%) compared with survivors, but none of these associations reached statistical significance. Furthermore, 30-day mortality was not associated with gender, age, Candida species, endophthalmitis, or type of antifungal therapy, said Dr. Matsuo, who spoke at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

An infectious disease consultation was associated with about a 70% reduction in the odds of mortality in the multivariate analysis, but the 95% confidence interval crossed 1.0, rendering the link statistically insignificant.

Given the small sample size and single-center design of this study, its findings ideally should be confirmed in a larger randomized controlled trial, Dr. Matsuo said. The investigators also did not track whether patients were fungemic at the time of CVC replacement, he noted.

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Wait at least 2 days before replacing central venous catheters (CVC) in patients with catheter-associated candidemia, according to the results of a single-center retrospective cohort study of 228 patients.

Waiting less than 2 days to replace a CVC increased the odds of 30-day mortality nearly sixfold among patients with catheter-related bloodstream infections due to candidemia, even after controlling for potential confounders, Takahiro Matsuo, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. No other factor significantly predicted mortality in univariate or multivariate analyses, he said. “This is the first study to demonstrate the optimal timing of central venous catheter replacement in catheter-related [bloodstream infection] due to Candida.”

Invasive candidiasis is associated with mortality rates of up to 50%, noted Dr. Matsuo, who is a fellow in infectious diseases at St. Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo. Antifungal therapy improves outcomes, and most physicians agree that removing a CVC does, too. To better pinpoint optimal timing of catheter replacement, Dr. Matsuo and his associates examined risk factors for 30-day mortality among patients with candidemia who were treated at St. Luke’s between 2004 and 2015.

Among 228 patients with candidemia, 166 had CVCs, and 144 had their CVC removed. Among 71 patients who needed their CVC replaced, 15 died within 30 days. Central venous catheters were replaced less than 2 days after removal in 87% of patients who died and in 54% of survivors (P = .04). The association remained statistically significant after the researchers accounted for potential confounders (adjusted odds ratio, 5.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-29.7; P = .03).

Patients who died within 30 days of CVC replacement also were more likely to have hematologic malignancies (20% versus 4%), diabetes (13% vs. 11%), to be on hemodialysis (27% vs. 16%), and to have a history of recent corticosteroid exposure (20% versus 11%) compared with survivors, but none of these associations reached statistical significance. Furthermore, 30-day mortality was not associated with gender, age, Candida species, endophthalmitis, or type of antifungal therapy, said Dr. Matsuo, who spoke at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

An infectious disease consultation was associated with about a 70% reduction in the odds of mortality in the multivariate analysis, but the 95% confidence interval crossed 1.0, rendering the link statistically insignificant.

Given the small sample size and single-center design of this study, its findings ideally should be confirmed in a larger randomized controlled trial, Dr. Matsuo said. The investigators also did not track whether patients were fungemic at the time of CVC replacement, he noted.

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Wait at least 2 days before replacing central venous catheters (CVC) in patients with catheter-associated candidemia, according to the results of a single-center retrospective cohort study of 228 patients.

Waiting less than 2 days to replace a CVC increased the odds of 30-day mortality nearly sixfold among patients with catheter-related bloodstream infections due to candidemia, even after controlling for potential confounders, Takahiro Matsuo, MD, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. No other factor significantly predicted mortality in univariate or multivariate analyses, he said. “This is the first study to demonstrate the optimal timing of central venous catheter replacement in catheter-related [bloodstream infection] due to Candida.”

Invasive candidiasis is associated with mortality rates of up to 50%, noted Dr. Matsuo, who is a fellow in infectious diseases at St. Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo. Antifungal therapy improves outcomes, and most physicians agree that removing a CVC does, too. To better pinpoint optimal timing of catheter replacement, Dr. Matsuo and his associates examined risk factors for 30-day mortality among patients with candidemia who were treated at St. Luke’s between 2004 and 2015.

Among 228 patients with candidemia, 166 had CVCs, and 144 had their CVC removed. Among 71 patients who needed their CVC replaced, 15 died within 30 days. Central venous catheters were replaced less than 2 days after removal in 87% of patients who died and in 54% of survivors (P = .04). The association remained statistically significant after the researchers accounted for potential confounders (adjusted odds ratio, 5.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-29.7; P = .03).

Patients who died within 30 days of CVC replacement also were more likely to have hematologic malignancies (20% versus 4%), diabetes (13% vs. 11%), to be on hemodialysis (27% vs. 16%), and to have a history of recent corticosteroid exposure (20% versus 11%) compared with survivors, but none of these associations reached statistical significance. Furthermore, 30-day mortality was not associated with gender, age, Candida species, endophthalmitis, or type of antifungal therapy, said Dr. Matsuo, who spoke at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

An infectious disease consultation was associated with about a 70% reduction in the odds of mortality in the multivariate analysis, but the 95% confidence interval crossed 1.0, rendering the link statistically insignificant.

Given the small sample size and single-center design of this study, its findings ideally should be confirmed in a larger randomized controlled trial, Dr. Matsuo said. The investigators also did not track whether patients were fungemic at the time of CVC replacement, he noted.

The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT IDWEEK 2017

Key clinical point: Consider waiting at least 2 days to replace a central venous catheter that has been removed because of candidemia.

Major finding: (odds ratio, 5.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-27.3).

Data source: A single-center retrospective cohort study of 228 patients with candidemia.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no conflicts of interest.

A game of telephone?

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The transfer of information from floor to the MICU team is a very interesting process: outside of the patient record, the person performing the handoff is highly responsible in the appropriate transfer of information.

One of the challenges encountered within the project is the way in which we are categorizing agreement between groups. Previously, we created a set of categories based upon recurring themes present within the free-text provider responses, and created categories, such as “cardiac management” and “diabetes management.” Upon creating these categories, I would then group them based upon concordance. However, responses such as “bipap during the night” and “not giving her bipap” would both be coded under “respiratory management,” but those two responses would not show the providers being in concordance. Upon consulting with my mentors Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, we decided that it would be more accurate to categorize concordance based upon the original answers, keeping the breadth of the original data intact.

As I continue to organize the data based on concordance, I have to modify my frame of thought and focus on appropriately representing the responses. There is no such thing as perfect data, and this project is no exception; in this case, not every provider was able to be reached for a response, which requires more nuance as I categorize the degree of concordance within the data and think of appropriate categories. I am very glad to learn the skill of appropriate data representation, as we want it to demonstrate both the potential lack or presence of clarity in handoffs, as well as the represented responding providers.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The transfer of information from floor to the MICU team is a very interesting process: outside of the patient record, the person performing the handoff is highly responsible in the appropriate transfer of information.

One of the challenges encountered within the project is the way in which we are categorizing agreement between groups. Previously, we created a set of categories based upon recurring themes present within the free-text provider responses, and created categories, such as “cardiac management” and “diabetes management.” Upon creating these categories, I would then group them based upon concordance. However, responses such as “bipap during the night” and “not giving her bipap” would both be coded under “respiratory management,” but those two responses would not show the providers being in concordance. Upon consulting with my mentors Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, we decided that it would be more accurate to categorize concordance based upon the original answers, keeping the breadth of the original data intact.

As I continue to organize the data based on concordance, I have to modify my frame of thought and focus on appropriately representing the responses. There is no such thing as perfect data, and this project is no exception; in this case, not every provider was able to be reached for a response, which requires more nuance as I categorize the degree of concordance within the data and think of appropriate categories. I am very glad to learn the skill of appropriate data representation, as we want it to demonstrate both the potential lack or presence of clarity in handoffs, as well as the represented responding providers.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

The transfer of information from floor to the MICU team is a very interesting process: outside of the patient record, the person performing the handoff is highly responsible in the appropriate transfer of information.

One of the challenges encountered within the project is the way in which we are categorizing agreement between groups. Previously, we created a set of categories based upon recurring themes present within the free-text provider responses, and created categories, such as “cardiac management” and “diabetes management.” Upon creating these categories, I would then group them based upon concordance. However, responses such as “bipap during the night” and “not giving her bipap” would both be coded under “respiratory management,” but those two responses would not show the providers being in concordance. Upon consulting with my mentors Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, we decided that it would be more accurate to categorize concordance based upon the original answers, keeping the breadth of the original data intact.

As I continue to organize the data based on concordance, I have to modify my frame of thought and focus on appropriately representing the responses. There is no such thing as perfect data, and this project is no exception; in this case, not every provider was able to be reached for a response, which requires more nuance as I categorize the degree of concordance within the data and think of appropriate categories. I am very glad to learn the skill of appropriate data representation, as we want it to demonstrate both the potential lack or presence of clarity in handoffs, as well as the represented responding providers.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Thinking about the basic science of quality improvement

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

I reviewed recent literature about my research topic, which is clinical pathways for hospitalized injection drug users due to injection-related infection sequelae and came up with my research proposal. As part of a scholarly pursuit, I believe having a theoretical background of quality improvement to be important. Before further diving into the research topic, I also generated a small reading list of the “basic science” of quality improvement, which covers topics of general operational science and those in health care applications.

What makes standardization in health care difficult? In my operations class at Tuck School of Business, we watched a video showing former Soviet Union ophthalmologists performing “assembly line” cataract surgery. It includes multiple surgeons sitting around multiple rotating tables, each surgeon performing exactly one step of the cataract surgery. I recall all my classmates were amused by the video, because it appeared both impractical (as one surgeon was almost chasing the table) as well as slightly de-humanizing. In the health care setting, standardization can be difficult. The service is intrinsically complex, it is difficult to define processes and to measure outcomes, and standardization can create tension secondary to physician autonomy and organizational culture.

In service delivery, the person (the patient in health care organizations) is part of the production process. Patients by nature are not standard inputs. They assume different pre-existing conditions and have different preferences for clinical and non-clinical services/processes. The medical service itself, consisting of both clinical and operational processes, sometimes can be difficult to qualify and measure. A hospital can control patient flow by managing appointment and beds allocation. Clinical pathways can be defined for different diseases. However, patients can encounter undiscovered diseases or complications during the treatment, making the clinical service different and unpredictable.

Lastly standardization can encounter resistance from physicians and other health care providers. “Patients are not cars” is a phrase commonly used when discussing standardization. A health care organization needs to have not only tools, but also the cultural and managerial foundations to carry out changes. I am looking forward to using this project opportunity to further explore the local application of quality improvement.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the US or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

I reviewed recent literature about my research topic, which is clinical pathways for hospitalized injection drug users due to injection-related infection sequelae and came up with my research proposal. As part of a scholarly pursuit, I believe having a theoretical background of quality improvement to be important. Before further diving into the research topic, I also generated a small reading list of the “basic science” of quality improvement, which covers topics of general operational science and those in health care applications.

What makes standardization in health care difficult? In my operations class at Tuck School of Business, we watched a video showing former Soviet Union ophthalmologists performing “assembly line” cataract surgery. It includes multiple surgeons sitting around multiple rotating tables, each surgeon performing exactly one step of the cataract surgery. I recall all my classmates were amused by the video, because it appeared both impractical (as one surgeon was almost chasing the table) as well as slightly de-humanizing. In the health care setting, standardization can be difficult. The service is intrinsically complex, it is difficult to define processes and to measure outcomes, and standardization can create tension secondary to physician autonomy and organizational culture.

In service delivery, the person (the patient in health care organizations) is part of the production process. Patients by nature are not standard inputs. They assume different pre-existing conditions and have different preferences for clinical and non-clinical services/processes. The medical service itself, consisting of both clinical and operational processes, sometimes can be difficult to qualify and measure. A hospital can control patient flow by managing appointment and beds allocation. Clinical pathways can be defined for different diseases. However, patients can encounter undiscovered diseases or complications during the treatment, making the clinical service different and unpredictable.

Lastly standardization can encounter resistance from physicians and other health care providers. “Patients are not cars” is a phrase commonly used when discussing standardization. A health care organization needs to have not only tools, but also the cultural and managerial foundations to carry out changes. I am looking forward to using this project opportunity to further explore the local application of quality improvement.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the US or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

I reviewed recent literature about my research topic, which is clinical pathways for hospitalized injection drug users due to injection-related infection sequelae and came up with my research proposal. As part of a scholarly pursuit, I believe having a theoretical background of quality improvement to be important. Before further diving into the research topic, I also generated a small reading list of the “basic science” of quality improvement, which covers topics of general operational science and those in health care applications.

What makes standardization in health care difficult? In my operations class at Tuck School of Business, we watched a video showing former Soviet Union ophthalmologists performing “assembly line” cataract surgery. It includes multiple surgeons sitting around multiple rotating tables, each surgeon performing exactly one step of the cataract surgery. I recall all my classmates were amused by the video, because it appeared both impractical (as one surgeon was almost chasing the table) as well as slightly de-humanizing. In the health care setting, standardization can be difficult. The service is intrinsically complex, it is difficult to define processes and to measure outcomes, and standardization can create tension secondary to physician autonomy and organizational culture.

In service delivery, the person (the patient in health care organizations) is part of the production process. Patients by nature are not standard inputs. They assume different pre-existing conditions and have different preferences for clinical and non-clinical services/processes. The medical service itself, consisting of both clinical and operational processes, sometimes can be difficult to qualify and measure. A hospital can control patient flow by managing appointment and beds allocation. Clinical pathways can be defined for different diseases. However, patients can encounter undiscovered diseases or complications during the treatment, making the clinical service different and unpredictable.

Lastly standardization can encounter resistance from physicians and other health care providers. “Patients are not cars” is a phrase commonly used when discussing standardization. A health care organization needs to have not only tools, but also the cultural and managerial foundations to carry out changes. I am looking forward to using this project opportunity to further explore the local application of quality improvement.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the US or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Everolimus has long-term efficacy in tuberous sclerosis complex

SAN DIEGO – Everolimus reduces the frequency of epileptic seizures in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), and its effect appears to gain strength over time. By the end of an extension study, half of patients had at least a 31.7% reduction in seizure frequency at 18 weeks, and that percentage rose to 56.9% at 2 years.

The drug was chosen because it inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which plays a central role in protein synthesis, cell division, and other vital processes. In patients with TSC, the kinase is overactive, and this leads to abnormalities in brain development. Overall, 85% of TSC patients experience seizures, and 60% are refractory to antiepileptic drugs.

The success of everolimus (Afinitor) is encouraging, and it’s the first epilepsy drug to be chosen for its mechanism of action, David Neal Franz, MD, said in an interview. “It has been used off label, but this study really shows that it has a statistically significant benefit that improves over time. A lot of things are used off label, but most don’t have this kind of class II evidence to support being used,” said Dr. Franz, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

The drug was particularly effective in children, who experienced a greater reduction in seizure frequency over time. That suggests that earlier treatment with everolimus could counter some of the damage in these patients before it becomes entrenched. “We’re planning to do studies to evaluate that. Because if you can avoid intractable epilepsy and its effects on development, there’s the potential to have a very significant benefit for children,” said Dr. Franz, who is a professor of pediatrics and neurology and founding director of the Tuberous Sclerosis Clinic at the University of Cincinnati. He noted that some previous studies showed that early treatment of infantile spasms is associated with lower risk of intellectual disability and autism.

The study enrolled 361 TSC patients with epilepsy across a wide age range (2-65 years). Their epilepsy had remained uncontrolled following treatment with at least six previous drugs. The core phase of the trial lasted 18 weeks, followed by an extension phase in which patients in the placebo group were switched to everolimus with a target dose of 3-15 ng/mL.

The primary efficacy outcome was the change in weekly seizure frequency. The researchers defined a response as a 50% or higher reduction.

In the original pivotal trial (EXIST-3), 15.1% of patients on placebo responded (95% confidence interval, 9.2%-22.8%) at week 18, compared with 28.2% of patients receiving a 3-7 ng/mL dose of everolimus (95% CI, 20.3%-37.3%; P = .0077) and 40% of patients receiving a 9-15 ng/mL dose of everolimus (95% CI, 31.5%-49%; P less than .0001).

The response rate at 18 weeks of treatment when combining both the original everolimus-treated patients and also the group switching over to everolimus in the extension phase was 31% (95% CI, 26.2%-36.1%). By 1 year, 46.6% had responded (95% CI, 40.9%-52.5%), and 57.7% had responded at 2 years (95% CI, 49.7%-65.4%).

The median percentage reduction in seizure frequency rose from 31.7% at week 18 (95% CI, 28.5%-36.1%) to 46.7% at 1 year (95% CI, 40.2%-54.0%) and 56.9% at 2 years (95% CI, 50%-68.4%).

Younger patients experienced greater improvements over time. At 2 years, 76% of 101 patients aged 0-6 years had responded (95% CI, 58.8%-88.2%), compared with 58.5% of patients aged 6-12 years (95% CI, 44.1%-71.9%), 51.1% of patients aged 12-18 years (95% CI, 35.8%-66.3%), and 43% of patients 18 years and older (95% CI, 24.5%-62.8%).

A sensitivity analysis of patients who discontinued the drug and were categorized as nonresponders showed the drug was still associated with a risk reduction of 30.2% at week 18 (95% CI, 25.5%-35.2%), 38.8% at 1 year (95% CI, 33.7%-44.1%), and 41% at 2 years (95% CI, 34.6%-47.7%).

Adverse events declined over time from 76.1% during the first 6 months of treatment to 46.8% at 1 year and 45.2% at 2 years. A total of 40.2% of patients experienced grade III/IV adverse events, and 13% of patients discontinued medication as a result. Another 1.7% experienced pneumonia, and 1.4% experienced stomatitis.

The most concerning side effects noted were tied to infection risk, which was not surprising given that everolimus is an immunosuppressive agent that is also used to prevent organ rejection. “The good thing is that you can hold everolimus when patients get sick or have a fever, and it doesn’t immediately lose efficacy. It binds avidly to mTOR, and so you can often go several weeks off the drug before you see loss of seizure control,” Dr. Franz said.

The study was funded by Novartis. Dr. Franz has received travel funding and honoraria from Novartis.

SAN DIEGO – Everolimus reduces the frequency of epileptic seizures in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), and its effect appears to gain strength over time. By the end of an extension study, half of patients had at least a 31.7% reduction in seizure frequency at 18 weeks, and that percentage rose to 56.9% at 2 years.

The drug was chosen because it inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which plays a central role in protein synthesis, cell division, and other vital processes. In patients with TSC, the kinase is overactive, and this leads to abnormalities in brain development. Overall, 85% of TSC patients experience seizures, and 60% are refractory to antiepileptic drugs.

The success of everolimus (Afinitor) is encouraging, and it’s the first epilepsy drug to be chosen for its mechanism of action, David Neal Franz, MD, said in an interview. “It has been used off label, but this study really shows that it has a statistically significant benefit that improves over time. A lot of things are used off label, but most don’t have this kind of class II evidence to support being used,” said Dr. Franz, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

The drug was particularly effective in children, who experienced a greater reduction in seizure frequency over time. That suggests that earlier treatment with everolimus could counter some of the damage in these patients before it becomes entrenched. “We’re planning to do studies to evaluate that. Because if you can avoid intractable epilepsy and its effects on development, there’s the potential to have a very significant benefit for children,” said Dr. Franz, who is a professor of pediatrics and neurology and founding director of the Tuberous Sclerosis Clinic at the University of Cincinnati. He noted that some previous studies showed that early treatment of infantile spasms is associated with lower risk of intellectual disability and autism.

The study enrolled 361 TSC patients with epilepsy across a wide age range (2-65 years). Their epilepsy had remained uncontrolled following treatment with at least six previous drugs. The core phase of the trial lasted 18 weeks, followed by an extension phase in which patients in the placebo group were switched to everolimus with a target dose of 3-15 ng/mL.

The primary efficacy outcome was the change in weekly seizure frequency. The researchers defined a response as a 50% or higher reduction.

In the original pivotal trial (EXIST-3), 15.1% of patients on placebo responded (95% confidence interval, 9.2%-22.8%) at week 18, compared with 28.2% of patients receiving a 3-7 ng/mL dose of everolimus (95% CI, 20.3%-37.3%; P = .0077) and 40% of patients receiving a 9-15 ng/mL dose of everolimus (95% CI, 31.5%-49%; P less than .0001).

The response rate at 18 weeks of treatment when combining both the original everolimus-treated patients and also the group switching over to everolimus in the extension phase was 31% (95% CI, 26.2%-36.1%). By 1 year, 46.6% had responded (95% CI, 40.9%-52.5%), and 57.7% had responded at 2 years (95% CI, 49.7%-65.4%).

The median percentage reduction in seizure frequency rose from 31.7% at week 18 (95% CI, 28.5%-36.1%) to 46.7% at 1 year (95% CI, 40.2%-54.0%) and 56.9% at 2 years (95% CI, 50%-68.4%).

Younger patients experienced greater improvements over time. At 2 years, 76% of 101 patients aged 0-6 years had responded (95% CI, 58.8%-88.2%), compared with 58.5% of patients aged 6-12 years (95% CI, 44.1%-71.9%), 51.1% of patients aged 12-18 years (95% CI, 35.8%-66.3%), and 43% of patients 18 years and older (95% CI, 24.5%-62.8%).

A sensitivity analysis of patients who discontinued the drug and were categorized as nonresponders showed the drug was still associated with a risk reduction of 30.2% at week 18 (95% CI, 25.5%-35.2%), 38.8% at 1 year (95% CI, 33.7%-44.1%), and 41% at 2 years (95% CI, 34.6%-47.7%).

Adverse events declined over time from 76.1% during the first 6 months of treatment to 46.8% at 1 year and 45.2% at 2 years. A total of 40.2% of patients experienced grade III/IV adverse events, and 13% of patients discontinued medication as a result. Another 1.7% experienced pneumonia, and 1.4% experienced stomatitis.

The most concerning side effects noted were tied to infection risk, which was not surprising given that everolimus is an immunosuppressive agent that is also used to prevent organ rejection. “The good thing is that you can hold everolimus when patients get sick or have a fever, and it doesn’t immediately lose efficacy. It binds avidly to mTOR, and so you can often go several weeks off the drug before you see loss of seizure control,” Dr. Franz said.

The study was funded by Novartis. Dr. Franz has received travel funding and honoraria from Novartis.

SAN DIEGO – Everolimus reduces the frequency of epileptic seizures in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), and its effect appears to gain strength over time. By the end of an extension study, half of patients had at least a 31.7% reduction in seizure frequency at 18 weeks, and that percentage rose to 56.9% at 2 years.

The drug was chosen because it inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which plays a central role in protein synthesis, cell division, and other vital processes. In patients with TSC, the kinase is overactive, and this leads to abnormalities in brain development. Overall, 85% of TSC patients experience seizures, and 60% are refractory to antiepileptic drugs.

The success of everolimus (Afinitor) is encouraging, and it’s the first epilepsy drug to be chosen for its mechanism of action, David Neal Franz, MD, said in an interview. “It has been used off label, but this study really shows that it has a statistically significant benefit that improves over time. A lot of things are used off label, but most don’t have this kind of class II evidence to support being used,” said Dr. Franz, who presented the study at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

The drug was particularly effective in children, who experienced a greater reduction in seizure frequency over time. That suggests that earlier treatment with everolimus could counter some of the damage in these patients before it becomes entrenched. “We’re planning to do studies to evaluate that. Because if you can avoid intractable epilepsy and its effects on development, there’s the potential to have a very significant benefit for children,” said Dr. Franz, who is a professor of pediatrics and neurology and founding director of the Tuberous Sclerosis Clinic at the University of Cincinnati. He noted that some previous studies showed that early treatment of infantile spasms is associated with lower risk of intellectual disability and autism.

The study enrolled 361 TSC patients with epilepsy across a wide age range (2-65 years). Their epilepsy had remained uncontrolled following treatment with at least six previous drugs. The core phase of the trial lasted 18 weeks, followed by an extension phase in which patients in the placebo group were switched to everolimus with a target dose of 3-15 ng/mL.

The primary efficacy outcome was the change in weekly seizure frequency. The researchers defined a response as a 50% or higher reduction.

In the original pivotal trial (EXIST-3), 15.1% of patients on placebo responded (95% confidence interval, 9.2%-22.8%) at week 18, compared with 28.2% of patients receiving a 3-7 ng/mL dose of everolimus (95% CI, 20.3%-37.3%; P = .0077) and 40% of patients receiving a 9-15 ng/mL dose of everolimus (95% CI, 31.5%-49%; P less than .0001).

The response rate at 18 weeks of treatment when combining both the original everolimus-treated patients and also the group switching over to everolimus in the extension phase was 31% (95% CI, 26.2%-36.1%). By 1 year, 46.6% had responded (95% CI, 40.9%-52.5%), and 57.7% had responded at 2 years (95% CI, 49.7%-65.4%).

The median percentage reduction in seizure frequency rose from 31.7% at week 18 (95% CI, 28.5%-36.1%) to 46.7% at 1 year (95% CI, 40.2%-54.0%) and 56.9% at 2 years (95% CI, 50%-68.4%).

Younger patients experienced greater improvements over time. At 2 years, 76% of 101 patients aged 0-6 years had responded (95% CI, 58.8%-88.2%), compared with 58.5% of patients aged 6-12 years (95% CI, 44.1%-71.9%), 51.1% of patients aged 12-18 years (95% CI, 35.8%-66.3%), and 43% of patients 18 years and older (95% CI, 24.5%-62.8%).

A sensitivity analysis of patients who discontinued the drug and were categorized as nonresponders showed the drug was still associated with a risk reduction of 30.2% at week 18 (95% CI, 25.5%-35.2%), 38.8% at 1 year (95% CI, 33.7%-44.1%), and 41% at 2 years (95% CI, 34.6%-47.7%).

Adverse events declined over time from 76.1% during the first 6 months of treatment to 46.8% at 1 year and 45.2% at 2 years. A total of 40.2% of patients experienced grade III/IV adverse events, and 13% of patients discontinued medication as a result. Another 1.7% experienced pneumonia, and 1.4% experienced stomatitis.