User login

Use of Intravenous Tranexamic Acid Improves Early Ambulation After Total Knee Arthroplasty and Anterior and Posterior Total Hip Arthroplasty

Take-Home Points

- IV-TXA significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss following TJA.

- Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of postoperative complications.

- IV-TXA minimizes postoperative anemia, facilitating improved early ambulation following TJA.

- IV-TXA significantly reduces the need for postoperative transfusions.

- IV-TXA is safe to use with no adverse events noted.

By the year 2020, use of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United States will increase an estimated 110%, to 1.375 million procedures annually, and use of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) will increase an estimated 75%, to more than 500,000 procedures.1 Minimizing perioperative blood loss and improving early postoperative ambulation both correlate with reduced postoperative morbidity, allowing patients to return to their daily lives expeditiously.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, competitively blocks lysine receptor binding sites of plasminogen, sustaining and stabilizing the fibrin architecture.2 TXA must be present to occupy binding sites before plasminogen binds to fibrin, validating the need for preoperative administration so the drug is available early in the fibrinolytic cascade.3 Intravenous (IV) TXA diffuses rapidly into joint fluid and the synovial membrane.4 Drug concentration and elimination half-life in joint fluid are equivalent to those in serum. Elimination of TXA occurs by glomerular filtration, with about 30% of a 10-mg/kg dose removed in 1 hour, 55% over the first 3 hours, and 90% within 24 hours of IV administration.5

The efficacy of IV-TXA in minimizing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perioperative blood loss has been proved in small studies and meta-analyses.6-9 TXA-induced blood conservation decreases or eliminates the need for postoperative transfusion, which can impede valuable, early ambulation.10 In addition, the positive clinical safety profile of TXA supports routine use of TXA in TJA.6,11-15

The benefits of early ambulation after TJA are well established. Getting patients to walk on the day of surgery is a key part of effective and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of venous thrombosis and postoperative complications.16 In contrast to bed rest, sitting and standing promotes oxygen saturation, which improves tissue healing and minimizes adverse pulmonary events. Oxygen saturation also preserves muscle strength and blood flow, reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism and ulcers. Muscle strength must be maintained so normal gait can be regained.17 Compared with rehabilitation initiated 48 to 72 hours after TKA, rehabilitation initiated within 24 hours reduced the number of sessions needed to achieve independence and normal gait; in addition, early mobilization improved patient reports of pain after surgery.18 An evaluation of Denmark registry data revealed that mobilization to walking and use of crutches or canes was achieved earlier when ambulation was initiated on day of surgery.19 Finally, mobilization on day of surgery and during the immediate postoperative period improved long-term quality of life after TJA.20

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if use of IV-TXA improves early ambulation and reduces blood loss after TKA and anterior and posterior THA. We hypothesized that IV-TXA use would reduce postoperative anemia and improve early ambulation and outcomes without producing adverse events during the immediate postoperative period. TXA reduces bleeding, and reduced incidence of hemarthrosis, wound swelling, and anemia could facilitate ambulation, reduce complications, and shorten recovery in patients who undergo TJA.

Patients and Methods

In February 2014, this retrospective cohort study received Institutional Review Board approval to compare the safety and efficacy of IV-TXA (vs no TXA) in patients who underwent TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA.

In March 2012, multidisciplinary protocols were standardized to ensure a uniform hospital course for patients at our institution. All patients underwent preoperative testing and evaluation by a nurse practitioner and an anesthesiologist. In March 2013, IV-TXA became our standard of care. TXA use was contraindicated in patients with thromboembolic disease or with hypersensitivity to TXA. Patients without a contraindication were given two 10-mg/kg IV-TXA doses, each administered over 15 to 30 minutes; the first dose was administered before incision, and the second was infused at case close and/or at least 60 minutes after the first dose. Most TKA patients received regional (femoral) anesthesia and analgesia, and most THA patients received spinal or epidural anesthesia and analgesia. In a small percentage of cases, IV analgesia was patient-controlled, as determined by the pain service. There were no significant differences in anesthesia/analgesia modality between the 2 study groups—patients who received TXA and those who did not. Patients were then transitioned to oral opioids for pain management, unless otherwise contraindicated, and were ambulated 4 hours after end of surgery, unless medically unstable. Hematology and chemistry laboratory values were monitored daily during admission.

Patients underwent physical therapy (PT) after surgery and until hospital discharge. Physical therapists blinded to patients’ intraoperative use or no use of TXA measured ambulation. After initial evaluation on postoperative day 0 (POD-0), patients were ambulated twice daily. The daily ambulation distance used for the study was the larger of the 2 daily PT distances (occasionally, patients were unable to participate fully in both sessions). Patients received either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for postoperative thromboprophylaxis (the anticoagulant used was based on surgeon preference). Enoxaparin was subcutaneously administered at 30 mg every 12 hours for TKA, 40 mg once daily for THA, 30 mg once daily for calculated creatinine clearance under 30 mL/min, or 40 mg every 12 hours for body mass index (BMI) 40 or above. With enoxaparin, therapy duration was 14 days. Oral rivaroxaban was administered at 10 mg once daily for 12 days for TKA and 35 days for THA unless contraindicated.

The primary outcome variables were ambulation measured on POD-1 and POD-2 and intraoperative blood loss. In addition, hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured on POD-0, POD-1, and POD-2. Ambulation was defined as number of feet walked during postoperative hospitalization. To calculate intraoperative blood loss, the anesthesiologist subtracted any saline irrigation volume from the total volume in the suction canister. Also noted were postoperative transfusions and any diagnosis of postoperative venous thromboembolism—specifically, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the TXA and no-TXA groups were compared using either 2-sample t test (for continuous variables) or χ2 test (for categorical variables).

The ambulation outcome was log-transformed to meet standard assumptions of Gaussian residuals and equality of variance. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the log scale and were anti-logged so the results could be presented in their original units.

A linear mixed model was used to model intraoperative blood loss as a function of group (TXA, no TXA), procedure (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA), and potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time).

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare outcomes (hemoglobin, hematocrit) between groups (TXA, no TXA) and procedures (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA) and to compare changes in outcomes over time. Group, procedure, and operative time interactions were explored. Potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time) were included in the model as well.

A χ2 test was used to compare the groups (TXA, no TXA) on postoperative blood transfusion (yes, no). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used. Need for transfusion was clinically assessed case by case. Symptomatic anemia (dyspnea on exertion, headaches, tachycardia) was used as the primary indication for transfusion once hemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL or hematocrit below 24%. Number of patients with a postoperative thrombus formation was minimal. Therefore, this outcome was described with summary statistics and was not formally analyzed.

Results

Of the 477 patients who underwent TJAs (275 TKAs, 98 anterior THAs, 104 posterior THAs; all unilateral), 111 did not receive TXA (June 2012-February 2013), and 366 received TXA (March 2013-January 2014). Other than for the addition of IV-TXA, the same standardized protocols instituted in March 2012 continued throughout the study period. The difference in sample size between the TXA and no-TXA groups was not statistically significant and did not influence the outcome measures.

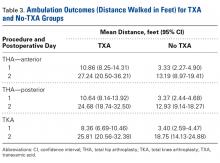

Ambulation

There was a significant (P = .0066) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P < .0001), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .8308). Regarding TKA, mean ambulation was higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-1 (8.36 vs 3.40 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (25.81 vs 18.75 feet; P = .0054). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (10.86 vs 3.33 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (27.24 vs 13.19 feet; P < .0001) and posterior THA at POD-1 (10.64 vs 3.37 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (24.68 vs 12.93 feet; P = .0002). See Table 3.

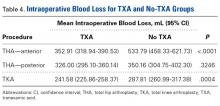

Intraoperative Blood Loss

There was a significant 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure (P < .0053), and operative time (P < .0001) after adjusting for age (P < .6136), sex (P = .1147), and BMI (P = .6180). Regarding TKA, mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group (241.58 vs 287.81 mL; P = .0004). The same was true for anterior THA (352.91 vs 533.79 mL; P < .0001). Regarding posterior THA, there was no significant difference between the TXA and no-TXA groups (326.00 vs 350.16 mL; P = .3246). See Table 4.

Hemoglobin

There was a significant (P = .0008) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .0174), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P = .0007), and operative time (P = .0002). Regarding TKA, postoperative hemoglobin levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (12.10 vs 11.68 g/dL; P = .0135), POD-1 (11.62 vs 10.67 g/dL; P < .0001), and POD-2 (11.02 vs 10.11 g/dL; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (11.03 vs 10.19 g/dL; P = .0034) and POD-2 (10.57 vs 9.64 g/dL; P = .0009) and posterior THA at POD-2 (11.04 vs 10.16 g/dL; P = .0003). See Table 5.

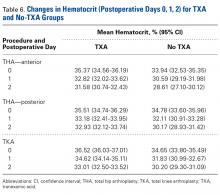

Hematocrit

There was a significant (P < .0006) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .1597), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .0003). Regarding TKA, postoperative hematocrit levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (36.52% vs 34.65%; P < .0001), POD-1 (34.62% vs 31.83%; P < .0001), and POD-2 (33.01% vs 30.20%; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (32.82% vs 30.59%; P = .0037) and POD-2 (31.58% vs 28.61%; P = .0004) and posterior THA at POD-2 (32.93% vs 30.17%; P < .0001). See Table 6.

Postoperative Transfusions

Of the 477 patients, 25 (5.24%) required a postoperative transfusion. Postoperative transfusions were less likely (P < .0001) required in the TXA group (1.64%, 6/366) than in the no-TXA group (17.12%, 19/111). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used, and the different procedures were not evaluated separately.

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

Of the 477 patients, 2 developed a DVT, and 5 developed a PE. Both DVTs occurred in the TXA group (2/366, 0.55%; 95% CI, 0.07%-1.96%). Of the 5 PEs, 4 occurred in the TXA group (4/366, 1.09%; 95% CI, 0.30%-2.77%), and 1 occurred in the no-TXA group (1/111, 0.90%; 95% CI, 0.02%-4.92%). Given the exceedingly small number of events, no statistical significance was noted between groups.

Discussion

Orthopedic surgeons carefully balance patient expectations, societal needs, and regulatory mandates while providing excellent care and working under payers’ financial restrictions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that, starting in 2016, TJAs will be reimbursed in total as a single bundled payment, adding to the need to provide optimal care in a fiscally responsible manner.21 Standardized protocols implementing multimodal therapies are pivotal in achieving favorable postoperative outcomes.

Our study results showed that IV-TXA use minimized hemoglobin and hematocrit reductions after TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. Postoperative anemia correlates with decreased ambulation ability and performance during the early postoperative period. In general, higher postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result in improved motor performance and shorter recovery.22 In addition, early ambulation is a validated predictor of favorable TJA outcomes. In our study, for TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA, ambulation on POD-1 and POD-2 was significantly better for patients who received TXA than for patients who did not.

Transfusion rates were markedly lower for our TXA group than for our no-TXA group (1.64% vs 17.12%), confirming the findings of numerous other studies on outcomes of TJA with TXA.2,3,6-12,14,15 Transfusions impede physical therapy and affect hospitalization costs.

Although potential thrombosis-related adverse events remain an endpoint in studies involving TXA, we found a comparably low incidence of postoperative venous thrombosis in our TXA and no-TXA groups (1.09% and 0.90%, respectively). In addition, no patient in either group developed a postoperative arterial thrombosis.

This is the largest single-center study of TXA use in TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. The effect of TXA use on postoperative ambulation was not previously found with TJA.

This study had its limitations. First, it was not prospective, randomized, or double-blinded. However, the physical therapists who mobilized patients and recorded ambulation data were blinded to the study and its hypothesis and followed a standardized protocol for all patients. In addition, intraoperative blood loss was recorded by an anesthesiologist using a standardized protocol, and patients received TXA per orthopedic protocol and surgeon preference, without selection bias. Another limitation was that ambulation data were captured only for POD-1 and POD-2 (most patients were discharged by POD-3). However, a goal of the study was to capture immediate postoperative data in order to determine the efficacy of intraoperative TXA. Subsequent studies can determine if this early benefit leads to long-term clinical outcome improvements.

In reducing blood loss and transfusion rates, intra-articular TXA is as efficacious as IV-TXA.23-25 We anticipate that the improved clinical outcomes found with IV-TXA in our study will be similar with intra-articular TXA, but more study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study found that use of IV-TXA in TJA improved early ambulation and clinical outcomes (reduced anemia, fewer transfusions) in the initial postoperative period, without producing adverse events.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Jansen AJ, Andreica S, Claeys M, D’Haese J, Camu F, Jochmans K. Use of tranexamic acid for an effective blood conservation strategy after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(4):596-601.

3. Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P. Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):442-448.

4. Tanaka N, Sakahashi, H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(5):702-705.

5. Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol). 1980;14:41-47.

6. George DA, Sarraf KM, Nwaboku H. Single perioperative dose of tranexamic acid in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(1):129-133.

7. Vigna-Taglianti F, Basso L, Rolfo P, et al. Tranexamic acid for reducing blood transfusions in arthroplasty interventions: a cost-effective practice. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):545-551.

8. Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31(5):529-537.

9. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829.

10. Sculco PK, Pagnano MW. Perioperative solutions for rapid recovery joint arthroplasty: get ahead and stay ahead. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(4):518-520.

11. Lozano M, Basora M, Peidro L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2008;95(1):39-44.

12. Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE. The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(6):776-783.

13. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585.

14. Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2874-2880.

15. Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):39-46.

16. Stowers M, Lemanu DP, Coleman B, Hill AG, Munro JT. Review article: perioperative care in enhanced recovery for total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2014;22(3):383-392.

17. Larsen K, Hansen TB, Søballe K. Hip arthroplasty patients benefit from accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(5):624-630.

18. Labraca NS, Castro-Sánchez AM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, Arroyo-Morales M, Sánchez-Joya Mdel M, Moreno-Lorenzo C. Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(6):557-566.

19. Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(2):263-268.

20. Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2012;83(346):1-39.

21. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. CMS.gov. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr. Updated October 5, 2017.

22. Wang X, Rintala DH, Garber SL, Henson H. Association of hemoglobin levels, acute hemoglobin decrease, age, and co-morbidities with rehabilitation outcomes after total knee replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(6):451-456.

23. Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1937-1944.

24. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

25. Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, et al. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1969-1974.

Take-Home Points

- IV-TXA significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss following TJA.

- Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of postoperative complications.

- IV-TXA minimizes postoperative anemia, facilitating improved early ambulation following TJA.

- IV-TXA significantly reduces the need for postoperative transfusions.

- IV-TXA is safe to use with no adverse events noted.

By the year 2020, use of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United States will increase an estimated 110%, to 1.375 million procedures annually, and use of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) will increase an estimated 75%, to more than 500,000 procedures.1 Minimizing perioperative blood loss and improving early postoperative ambulation both correlate with reduced postoperative morbidity, allowing patients to return to their daily lives expeditiously.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, competitively blocks lysine receptor binding sites of plasminogen, sustaining and stabilizing the fibrin architecture.2 TXA must be present to occupy binding sites before plasminogen binds to fibrin, validating the need for preoperative administration so the drug is available early in the fibrinolytic cascade.3 Intravenous (IV) TXA diffuses rapidly into joint fluid and the synovial membrane.4 Drug concentration and elimination half-life in joint fluid are equivalent to those in serum. Elimination of TXA occurs by glomerular filtration, with about 30% of a 10-mg/kg dose removed in 1 hour, 55% over the first 3 hours, and 90% within 24 hours of IV administration.5

The efficacy of IV-TXA in minimizing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perioperative blood loss has been proved in small studies and meta-analyses.6-9 TXA-induced blood conservation decreases or eliminates the need for postoperative transfusion, which can impede valuable, early ambulation.10 In addition, the positive clinical safety profile of TXA supports routine use of TXA in TJA.6,11-15

The benefits of early ambulation after TJA are well established. Getting patients to walk on the day of surgery is a key part of effective and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of venous thrombosis and postoperative complications.16 In contrast to bed rest, sitting and standing promotes oxygen saturation, which improves tissue healing and minimizes adverse pulmonary events. Oxygen saturation also preserves muscle strength and blood flow, reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism and ulcers. Muscle strength must be maintained so normal gait can be regained.17 Compared with rehabilitation initiated 48 to 72 hours after TKA, rehabilitation initiated within 24 hours reduced the number of sessions needed to achieve independence and normal gait; in addition, early mobilization improved patient reports of pain after surgery.18 An evaluation of Denmark registry data revealed that mobilization to walking and use of crutches or canes was achieved earlier when ambulation was initiated on day of surgery.19 Finally, mobilization on day of surgery and during the immediate postoperative period improved long-term quality of life after TJA.20

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if use of IV-TXA improves early ambulation and reduces blood loss after TKA and anterior and posterior THA. We hypothesized that IV-TXA use would reduce postoperative anemia and improve early ambulation and outcomes without producing adverse events during the immediate postoperative period. TXA reduces bleeding, and reduced incidence of hemarthrosis, wound swelling, and anemia could facilitate ambulation, reduce complications, and shorten recovery in patients who undergo TJA.

Patients and Methods

In February 2014, this retrospective cohort study received Institutional Review Board approval to compare the safety and efficacy of IV-TXA (vs no TXA) in patients who underwent TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA.

In March 2012, multidisciplinary protocols were standardized to ensure a uniform hospital course for patients at our institution. All patients underwent preoperative testing and evaluation by a nurse practitioner and an anesthesiologist. In March 2013, IV-TXA became our standard of care. TXA use was contraindicated in patients with thromboembolic disease or with hypersensitivity to TXA. Patients without a contraindication were given two 10-mg/kg IV-TXA doses, each administered over 15 to 30 minutes; the first dose was administered before incision, and the second was infused at case close and/or at least 60 minutes after the first dose. Most TKA patients received regional (femoral) anesthesia and analgesia, and most THA patients received spinal or epidural anesthesia and analgesia. In a small percentage of cases, IV analgesia was patient-controlled, as determined by the pain service. There were no significant differences in anesthesia/analgesia modality between the 2 study groups—patients who received TXA and those who did not. Patients were then transitioned to oral opioids for pain management, unless otherwise contraindicated, and were ambulated 4 hours after end of surgery, unless medically unstable. Hematology and chemistry laboratory values were monitored daily during admission.

Patients underwent physical therapy (PT) after surgery and until hospital discharge. Physical therapists blinded to patients’ intraoperative use or no use of TXA measured ambulation. After initial evaluation on postoperative day 0 (POD-0), patients were ambulated twice daily. The daily ambulation distance used for the study was the larger of the 2 daily PT distances (occasionally, patients were unable to participate fully in both sessions). Patients received either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for postoperative thromboprophylaxis (the anticoagulant used was based on surgeon preference). Enoxaparin was subcutaneously administered at 30 mg every 12 hours for TKA, 40 mg once daily for THA, 30 mg once daily for calculated creatinine clearance under 30 mL/min, or 40 mg every 12 hours for body mass index (BMI) 40 or above. With enoxaparin, therapy duration was 14 days. Oral rivaroxaban was administered at 10 mg once daily for 12 days for TKA and 35 days for THA unless contraindicated.

The primary outcome variables were ambulation measured on POD-1 and POD-2 and intraoperative blood loss. In addition, hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured on POD-0, POD-1, and POD-2. Ambulation was defined as number of feet walked during postoperative hospitalization. To calculate intraoperative blood loss, the anesthesiologist subtracted any saline irrigation volume from the total volume in the suction canister. Also noted were postoperative transfusions and any diagnosis of postoperative venous thromboembolism—specifically, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the TXA and no-TXA groups were compared using either 2-sample t test (for continuous variables) or χ2 test (for categorical variables).

The ambulation outcome was log-transformed to meet standard assumptions of Gaussian residuals and equality of variance. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the log scale and were anti-logged so the results could be presented in their original units.

A linear mixed model was used to model intraoperative blood loss as a function of group (TXA, no TXA), procedure (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA), and potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time).

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare outcomes (hemoglobin, hematocrit) between groups (TXA, no TXA) and procedures (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA) and to compare changes in outcomes over time. Group, procedure, and operative time interactions were explored. Potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time) were included in the model as well.

A χ2 test was used to compare the groups (TXA, no TXA) on postoperative blood transfusion (yes, no). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used. Need for transfusion was clinically assessed case by case. Symptomatic anemia (dyspnea on exertion, headaches, tachycardia) was used as the primary indication for transfusion once hemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL or hematocrit below 24%. Number of patients with a postoperative thrombus formation was minimal. Therefore, this outcome was described with summary statistics and was not formally analyzed.

Results

Of the 477 patients who underwent TJAs (275 TKAs, 98 anterior THAs, 104 posterior THAs; all unilateral), 111 did not receive TXA (June 2012-February 2013), and 366 received TXA (March 2013-January 2014). Other than for the addition of IV-TXA, the same standardized protocols instituted in March 2012 continued throughout the study period. The difference in sample size between the TXA and no-TXA groups was not statistically significant and did not influence the outcome measures.

Ambulation

There was a significant (P = .0066) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P < .0001), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .8308). Regarding TKA, mean ambulation was higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-1 (8.36 vs 3.40 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (25.81 vs 18.75 feet; P = .0054). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (10.86 vs 3.33 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (27.24 vs 13.19 feet; P < .0001) and posterior THA at POD-1 (10.64 vs 3.37 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (24.68 vs 12.93 feet; P = .0002). See Table 3.

Intraoperative Blood Loss

There was a significant 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure (P < .0053), and operative time (P < .0001) after adjusting for age (P < .6136), sex (P = .1147), and BMI (P = .6180). Regarding TKA, mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group (241.58 vs 287.81 mL; P = .0004). The same was true for anterior THA (352.91 vs 533.79 mL; P < .0001). Regarding posterior THA, there was no significant difference between the TXA and no-TXA groups (326.00 vs 350.16 mL; P = .3246). See Table 4.

Hemoglobin

There was a significant (P = .0008) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .0174), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P = .0007), and operative time (P = .0002). Regarding TKA, postoperative hemoglobin levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (12.10 vs 11.68 g/dL; P = .0135), POD-1 (11.62 vs 10.67 g/dL; P < .0001), and POD-2 (11.02 vs 10.11 g/dL; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (11.03 vs 10.19 g/dL; P = .0034) and POD-2 (10.57 vs 9.64 g/dL; P = .0009) and posterior THA at POD-2 (11.04 vs 10.16 g/dL; P = .0003). See Table 5.

Hematocrit

There was a significant (P < .0006) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .1597), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .0003). Regarding TKA, postoperative hematocrit levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (36.52% vs 34.65%; P < .0001), POD-1 (34.62% vs 31.83%; P < .0001), and POD-2 (33.01% vs 30.20%; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (32.82% vs 30.59%; P = .0037) and POD-2 (31.58% vs 28.61%; P = .0004) and posterior THA at POD-2 (32.93% vs 30.17%; P < .0001). See Table 6.

Postoperative Transfusions

Of the 477 patients, 25 (5.24%) required a postoperative transfusion. Postoperative transfusions were less likely (P < .0001) required in the TXA group (1.64%, 6/366) than in the no-TXA group (17.12%, 19/111). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used, and the different procedures were not evaluated separately.

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

Of the 477 patients, 2 developed a DVT, and 5 developed a PE. Both DVTs occurred in the TXA group (2/366, 0.55%; 95% CI, 0.07%-1.96%). Of the 5 PEs, 4 occurred in the TXA group (4/366, 1.09%; 95% CI, 0.30%-2.77%), and 1 occurred in the no-TXA group (1/111, 0.90%; 95% CI, 0.02%-4.92%). Given the exceedingly small number of events, no statistical significance was noted between groups.

Discussion

Orthopedic surgeons carefully balance patient expectations, societal needs, and regulatory mandates while providing excellent care and working under payers’ financial restrictions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that, starting in 2016, TJAs will be reimbursed in total as a single bundled payment, adding to the need to provide optimal care in a fiscally responsible manner.21 Standardized protocols implementing multimodal therapies are pivotal in achieving favorable postoperative outcomes.

Our study results showed that IV-TXA use minimized hemoglobin and hematocrit reductions after TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. Postoperative anemia correlates with decreased ambulation ability and performance during the early postoperative period. In general, higher postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result in improved motor performance and shorter recovery.22 In addition, early ambulation is a validated predictor of favorable TJA outcomes. In our study, for TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA, ambulation on POD-1 and POD-2 was significantly better for patients who received TXA than for patients who did not.

Transfusion rates were markedly lower for our TXA group than for our no-TXA group (1.64% vs 17.12%), confirming the findings of numerous other studies on outcomes of TJA with TXA.2,3,6-12,14,15 Transfusions impede physical therapy and affect hospitalization costs.

Although potential thrombosis-related adverse events remain an endpoint in studies involving TXA, we found a comparably low incidence of postoperative venous thrombosis in our TXA and no-TXA groups (1.09% and 0.90%, respectively). In addition, no patient in either group developed a postoperative arterial thrombosis.

This is the largest single-center study of TXA use in TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. The effect of TXA use on postoperative ambulation was not previously found with TJA.

This study had its limitations. First, it was not prospective, randomized, or double-blinded. However, the physical therapists who mobilized patients and recorded ambulation data were blinded to the study and its hypothesis and followed a standardized protocol for all patients. In addition, intraoperative blood loss was recorded by an anesthesiologist using a standardized protocol, and patients received TXA per orthopedic protocol and surgeon preference, without selection bias. Another limitation was that ambulation data were captured only for POD-1 and POD-2 (most patients were discharged by POD-3). However, a goal of the study was to capture immediate postoperative data in order to determine the efficacy of intraoperative TXA. Subsequent studies can determine if this early benefit leads to long-term clinical outcome improvements.

In reducing blood loss and transfusion rates, intra-articular TXA is as efficacious as IV-TXA.23-25 We anticipate that the improved clinical outcomes found with IV-TXA in our study will be similar with intra-articular TXA, but more study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study found that use of IV-TXA in TJA improved early ambulation and clinical outcomes (reduced anemia, fewer transfusions) in the initial postoperative period, without producing adverse events.

Take-Home Points

- IV-TXA significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss following TJA.

- Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of postoperative complications.

- IV-TXA minimizes postoperative anemia, facilitating improved early ambulation following TJA.

- IV-TXA significantly reduces the need for postoperative transfusions.

- IV-TXA is safe to use with no adverse events noted.

By the year 2020, use of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United States will increase an estimated 110%, to 1.375 million procedures annually, and use of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) will increase an estimated 75%, to more than 500,000 procedures.1 Minimizing perioperative blood loss and improving early postoperative ambulation both correlate with reduced postoperative morbidity, allowing patients to return to their daily lives expeditiously.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, competitively blocks lysine receptor binding sites of plasminogen, sustaining and stabilizing the fibrin architecture.2 TXA must be present to occupy binding sites before plasminogen binds to fibrin, validating the need for preoperative administration so the drug is available early in the fibrinolytic cascade.3 Intravenous (IV) TXA diffuses rapidly into joint fluid and the synovial membrane.4 Drug concentration and elimination half-life in joint fluid are equivalent to those in serum. Elimination of TXA occurs by glomerular filtration, with about 30% of a 10-mg/kg dose removed in 1 hour, 55% over the first 3 hours, and 90% within 24 hours of IV administration.5

The efficacy of IV-TXA in minimizing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perioperative blood loss has been proved in small studies and meta-analyses.6-9 TXA-induced blood conservation decreases or eliminates the need for postoperative transfusion, which can impede valuable, early ambulation.10 In addition, the positive clinical safety profile of TXA supports routine use of TXA in TJA.6,11-15

The benefits of early ambulation after TJA are well established. Getting patients to walk on the day of surgery is a key part of effective and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of venous thrombosis and postoperative complications.16 In contrast to bed rest, sitting and standing promotes oxygen saturation, which improves tissue healing and minimizes adverse pulmonary events. Oxygen saturation also preserves muscle strength and blood flow, reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism and ulcers. Muscle strength must be maintained so normal gait can be regained.17 Compared with rehabilitation initiated 48 to 72 hours after TKA, rehabilitation initiated within 24 hours reduced the number of sessions needed to achieve independence and normal gait; in addition, early mobilization improved patient reports of pain after surgery.18 An evaluation of Denmark registry data revealed that mobilization to walking and use of crutches or canes was achieved earlier when ambulation was initiated on day of surgery.19 Finally, mobilization on day of surgery and during the immediate postoperative period improved long-term quality of life after TJA.20

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if use of IV-TXA improves early ambulation and reduces blood loss after TKA and anterior and posterior THA. We hypothesized that IV-TXA use would reduce postoperative anemia and improve early ambulation and outcomes without producing adverse events during the immediate postoperative period. TXA reduces bleeding, and reduced incidence of hemarthrosis, wound swelling, and anemia could facilitate ambulation, reduce complications, and shorten recovery in patients who undergo TJA.

Patients and Methods

In February 2014, this retrospective cohort study received Institutional Review Board approval to compare the safety and efficacy of IV-TXA (vs no TXA) in patients who underwent TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA.

In March 2012, multidisciplinary protocols were standardized to ensure a uniform hospital course for patients at our institution. All patients underwent preoperative testing and evaluation by a nurse practitioner and an anesthesiologist. In March 2013, IV-TXA became our standard of care. TXA use was contraindicated in patients with thromboembolic disease or with hypersensitivity to TXA. Patients without a contraindication were given two 10-mg/kg IV-TXA doses, each administered over 15 to 30 minutes; the first dose was administered before incision, and the second was infused at case close and/or at least 60 minutes after the first dose. Most TKA patients received regional (femoral) anesthesia and analgesia, and most THA patients received spinal or epidural anesthesia and analgesia. In a small percentage of cases, IV analgesia was patient-controlled, as determined by the pain service. There were no significant differences in anesthesia/analgesia modality between the 2 study groups—patients who received TXA and those who did not. Patients were then transitioned to oral opioids for pain management, unless otherwise contraindicated, and were ambulated 4 hours after end of surgery, unless medically unstable. Hematology and chemistry laboratory values were monitored daily during admission.

Patients underwent physical therapy (PT) after surgery and until hospital discharge. Physical therapists blinded to patients’ intraoperative use or no use of TXA measured ambulation. After initial evaluation on postoperative day 0 (POD-0), patients were ambulated twice daily. The daily ambulation distance used for the study was the larger of the 2 daily PT distances (occasionally, patients were unable to participate fully in both sessions). Patients received either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for postoperative thromboprophylaxis (the anticoagulant used was based on surgeon preference). Enoxaparin was subcutaneously administered at 30 mg every 12 hours for TKA, 40 mg once daily for THA, 30 mg once daily for calculated creatinine clearance under 30 mL/min, or 40 mg every 12 hours for body mass index (BMI) 40 or above. With enoxaparin, therapy duration was 14 days. Oral rivaroxaban was administered at 10 mg once daily for 12 days for TKA and 35 days for THA unless contraindicated.

The primary outcome variables were ambulation measured on POD-1 and POD-2 and intraoperative blood loss. In addition, hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured on POD-0, POD-1, and POD-2. Ambulation was defined as number of feet walked during postoperative hospitalization. To calculate intraoperative blood loss, the anesthesiologist subtracted any saline irrigation volume from the total volume in the suction canister. Also noted were postoperative transfusions and any diagnosis of postoperative venous thromboembolism—specifically, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the TXA and no-TXA groups were compared using either 2-sample t test (for continuous variables) or χ2 test (for categorical variables).

The ambulation outcome was log-transformed to meet standard assumptions of Gaussian residuals and equality of variance. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the log scale and were anti-logged so the results could be presented in their original units.

A linear mixed model was used to model intraoperative blood loss as a function of group (TXA, no TXA), procedure (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA), and potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time).

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare outcomes (hemoglobin, hematocrit) between groups (TXA, no TXA) and procedures (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA) and to compare changes in outcomes over time. Group, procedure, and operative time interactions were explored. Potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time) were included in the model as well.

A χ2 test was used to compare the groups (TXA, no TXA) on postoperative blood transfusion (yes, no). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used. Need for transfusion was clinically assessed case by case. Symptomatic anemia (dyspnea on exertion, headaches, tachycardia) was used as the primary indication for transfusion once hemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL or hematocrit below 24%. Number of patients with a postoperative thrombus formation was minimal. Therefore, this outcome was described with summary statistics and was not formally analyzed.

Results

Of the 477 patients who underwent TJAs (275 TKAs, 98 anterior THAs, 104 posterior THAs; all unilateral), 111 did not receive TXA (June 2012-February 2013), and 366 received TXA (March 2013-January 2014). Other than for the addition of IV-TXA, the same standardized protocols instituted in March 2012 continued throughout the study period. The difference in sample size between the TXA and no-TXA groups was not statistically significant and did not influence the outcome measures.

Ambulation

There was a significant (P = .0066) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P < .0001), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .8308). Regarding TKA, mean ambulation was higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-1 (8.36 vs 3.40 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (25.81 vs 18.75 feet; P = .0054). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (10.86 vs 3.33 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (27.24 vs 13.19 feet; P < .0001) and posterior THA at POD-1 (10.64 vs 3.37 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (24.68 vs 12.93 feet; P = .0002). See Table 3.

Intraoperative Blood Loss

There was a significant 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure (P < .0053), and operative time (P < .0001) after adjusting for age (P < .6136), sex (P = .1147), and BMI (P = .6180). Regarding TKA, mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group (241.58 vs 287.81 mL; P = .0004). The same was true for anterior THA (352.91 vs 533.79 mL; P < .0001). Regarding posterior THA, there was no significant difference between the TXA and no-TXA groups (326.00 vs 350.16 mL; P = .3246). See Table 4.

Hemoglobin

There was a significant (P = .0008) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .0174), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P = .0007), and operative time (P = .0002). Regarding TKA, postoperative hemoglobin levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (12.10 vs 11.68 g/dL; P = .0135), POD-1 (11.62 vs 10.67 g/dL; P < .0001), and POD-2 (11.02 vs 10.11 g/dL; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (11.03 vs 10.19 g/dL; P = .0034) and POD-2 (10.57 vs 9.64 g/dL; P = .0009) and posterior THA at POD-2 (11.04 vs 10.16 g/dL; P = .0003). See Table 5.

Hematocrit

There was a significant (P < .0006) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .1597), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .0003). Regarding TKA, postoperative hematocrit levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (36.52% vs 34.65%; P < .0001), POD-1 (34.62% vs 31.83%; P < .0001), and POD-2 (33.01% vs 30.20%; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (32.82% vs 30.59%; P = .0037) and POD-2 (31.58% vs 28.61%; P = .0004) and posterior THA at POD-2 (32.93% vs 30.17%; P < .0001). See Table 6.

Postoperative Transfusions

Of the 477 patients, 25 (5.24%) required a postoperative transfusion. Postoperative transfusions were less likely (P < .0001) required in the TXA group (1.64%, 6/366) than in the no-TXA group (17.12%, 19/111). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used, and the different procedures were not evaluated separately.

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

Of the 477 patients, 2 developed a DVT, and 5 developed a PE. Both DVTs occurred in the TXA group (2/366, 0.55%; 95% CI, 0.07%-1.96%). Of the 5 PEs, 4 occurred in the TXA group (4/366, 1.09%; 95% CI, 0.30%-2.77%), and 1 occurred in the no-TXA group (1/111, 0.90%; 95% CI, 0.02%-4.92%). Given the exceedingly small number of events, no statistical significance was noted between groups.

Discussion

Orthopedic surgeons carefully balance patient expectations, societal needs, and regulatory mandates while providing excellent care and working under payers’ financial restrictions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that, starting in 2016, TJAs will be reimbursed in total as a single bundled payment, adding to the need to provide optimal care in a fiscally responsible manner.21 Standardized protocols implementing multimodal therapies are pivotal in achieving favorable postoperative outcomes.

Our study results showed that IV-TXA use minimized hemoglobin and hematocrit reductions after TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. Postoperative anemia correlates with decreased ambulation ability and performance during the early postoperative period. In general, higher postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result in improved motor performance and shorter recovery.22 In addition, early ambulation is a validated predictor of favorable TJA outcomes. In our study, for TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA, ambulation on POD-1 and POD-2 was significantly better for patients who received TXA than for patients who did not.

Transfusion rates were markedly lower for our TXA group than for our no-TXA group (1.64% vs 17.12%), confirming the findings of numerous other studies on outcomes of TJA with TXA.2,3,6-12,14,15 Transfusions impede physical therapy and affect hospitalization costs.

Although potential thrombosis-related adverse events remain an endpoint in studies involving TXA, we found a comparably low incidence of postoperative venous thrombosis in our TXA and no-TXA groups (1.09% and 0.90%, respectively). In addition, no patient in either group developed a postoperative arterial thrombosis.

This is the largest single-center study of TXA use in TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. The effect of TXA use on postoperative ambulation was not previously found with TJA.

This study had its limitations. First, it was not prospective, randomized, or double-blinded. However, the physical therapists who mobilized patients and recorded ambulation data were blinded to the study and its hypothesis and followed a standardized protocol for all patients. In addition, intraoperative blood loss was recorded by an anesthesiologist using a standardized protocol, and patients received TXA per orthopedic protocol and surgeon preference, without selection bias. Another limitation was that ambulation data were captured only for POD-1 and POD-2 (most patients were discharged by POD-3). However, a goal of the study was to capture immediate postoperative data in order to determine the efficacy of intraoperative TXA. Subsequent studies can determine if this early benefit leads to long-term clinical outcome improvements.

In reducing blood loss and transfusion rates, intra-articular TXA is as efficacious as IV-TXA.23-25 We anticipate that the improved clinical outcomes found with IV-TXA in our study will be similar with intra-articular TXA, but more study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study found that use of IV-TXA in TJA improved early ambulation and clinical outcomes (reduced anemia, fewer transfusions) in the initial postoperative period, without producing adverse events.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Jansen AJ, Andreica S, Claeys M, D’Haese J, Camu F, Jochmans K. Use of tranexamic acid for an effective blood conservation strategy after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(4):596-601.

3. Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P. Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):442-448.

4. Tanaka N, Sakahashi, H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(5):702-705.

5. Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol). 1980;14:41-47.

6. George DA, Sarraf KM, Nwaboku H. Single perioperative dose of tranexamic acid in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(1):129-133.

7. Vigna-Taglianti F, Basso L, Rolfo P, et al. Tranexamic acid for reducing blood transfusions in arthroplasty interventions: a cost-effective practice. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):545-551.

8. Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31(5):529-537.

9. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829.

10. Sculco PK, Pagnano MW. Perioperative solutions for rapid recovery joint arthroplasty: get ahead and stay ahead. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(4):518-520.

11. Lozano M, Basora M, Peidro L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2008;95(1):39-44.

12. Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE. The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(6):776-783.

13. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585.

14. Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2874-2880.

15. Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):39-46.

16. Stowers M, Lemanu DP, Coleman B, Hill AG, Munro JT. Review article: perioperative care in enhanced recovery for total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2014;22(3):383-392.

17. Larsen K, Hansen TB, Søballe K. Hip arthroplasty patients benefit from accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(5):624-630.

18. Labraca NS, Castro-Sánchez AM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, Arroyo-Morales M, Sánchez-Joya Mdel M, Moreno-Lorenzo C. Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(6):557-566.

19. Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(2):263-268.

20. Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2012;83(346):1-39.

21. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. CMS.gov. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr. Updated October 5, 2017.

22. Wang X, Rintala DH, Garber SL, Henson H. Association of hemoglobin levels, acute hemoglobin decrease, age, and co-morbidities with rehabilitation outcomes after total knee replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(6):451-456.

23. Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1937-1944.

24. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

25. Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, et al. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1969-1974.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Jansen AJ, Andreica S, Claeys M, D’Haese J, Camu F, Jochmans K. Use of tranexamic acid for an effective blood conservation strategy after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(4):596-601.

3. Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P. Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):442-448.

4. Tanaka N, Sakahashi, H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(5):702-705.

5. Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol). 1980;14:41-47.

6. George DA, Sarraf KM, Nwaboku H. Single perioperative dose of tranexamic acid in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(1):129-133.

7. Vigna-Taglianti F, Basso L, Rolfo P, et al. Tranexamic acid for reducing blood transfusions in arthroplasty interventions: a cost-effective practice. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):545-551.

8. Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31(5):529-537.

9. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829.

10. Sculco PK, Pagnano MW. Perioperative solutions for rapid recovery joint arthroplasty: get ahead and stay ahead. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(4):518-520.

11. Lozano M, Basora M, Peidro L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2008;95(1):39-44.

12. Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE. The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(6):776-783.

13. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585.

14. Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2874-2880.

15. Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):39-46.

16. Stowers M, Lemanu DP, Coleman B, Hill AG, Munro JT. Review article: perioperative care in enhanced recovery for total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2014;22(3):383-392.

17. Larsen K, Hansen TB, Søballe K. Hip arthroplasty patients benefit from accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(5):624-630.

18. Labraca NS, Castro-Sánchez AM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, Arroyo-Morales M, Sánchez-Joya Mdel M, Moreno-Lorenzo C. Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(6):557-566.

19. Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(2):263-268.

20. Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2012;83(346):1-39.

21. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. CMS.gov. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr. Updated October 5, 2017.

22. Wang X, Rintala DH, Garber SL, Henson H. Association of hemoglobin levels, acute hemoglobin decrease, age, and co-morbidities with rehabilitation outcomes after total knee replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(6):451-456.

23. Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1937-1944.

24. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

25. Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, et al. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1969-1974.

International parental attitudes of HPV vaccination have similarities, differences

A study comparing parental attitudes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in three countries indicates both low and high HPV knowledge may be associated with lower rates of vaccination, and parents’ country and gender also impact the likelihood of adolescents being immunized, reported Brooke Nickel, of the University of Sydney, and associates.

Of 179 parents with a daughter aged 9-17 years from the United States, United Kingdom, or Australia who took part in an online HPV vaccine opinion survey in 2011, 59% reported that their daughters had received HPV vaccination – 43% in the United States cohort, 63% in the United Kingdom cohort, and 76% in the Australian cohort.

(P less than .001). Parents who had either low knowledge scores or high knowledge scores were less likely to have their daughters vaccinated; U.S. parents and men across all countries also were less likely to vaccinate their daughters.

Among the parents whose daughters did not receive the HPV vaccine, worry about the vaccine’s side effects was significantly more prevalent among the U.S. parents (61%) than among parents in the United Kingdom (36%) or among parents in Australia (15%) (P less than .05). U.S. parents who did not have their daughters get the HPV vaccine also were more likely to agree that getting all three HPV vaccine doses would be a “big hassle” (21%), compared with the United Kingdom cohort (0%) and the Australian cohort (8%) (P less than .05).

Parents from the United States also were significantly more likely to agree that the HPV vaccine was too new so they would want to wait before deciding to get it for their daughters (45%), compared with the parents in the United Kingdom (23%) and those in Australia (8%) (P less than .05).

“This finding was unexpected, given that advertising about HPV contributed to an increased awareness of HPV in the United States at the time of data collection. It is important to note, however, that this survey was conducted in 2011, and therefore attitudes of U.S. parents now may differ,” the researchers wrote.

Nonetheless, parents of unvaccinated daughters with higher knowledge scores overall were more likely to believe that they would want to be on the safe side and vaccinate their daughters at some time (74%) compared with parents who had lower knowledge scores (27%) (P less than .001).

“Parents from the United States with unvaccinated daughters more often believed that getting all three doses of the HPV vaccine would be a significant obstacle, not surprisingly as the HPV vaccine distribution in the United States is predominantly available through physicians’ clinics and medical centers, whereas in the United Kingdom and Australia, free school-based and catch-up programs are offered,” the investigators said.

Read more in Preventive Medicine Reports (2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.10.005).

A study comparing parental attitudes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in three countries indicates both low and high HPV knowledge may be associated with lower rates of vaccination, and parents’ country and gender also impact the likelihood of adolescents being immunized, reported Brooke Nickel, of the University of Sydney, and associates.

Of 179 parents with a daughter aged 9-17 years from the United States, United Kingdom, or Australia who took part in an online HPV vaccine opinion survey in 2011, 59% reported that their daughters had received HPV vaccination – 43% in the United States cohort, 63% in the United Kingdom cohort, and 76% in the Australian cohort.

(P less than .001). Parents who had either low knowledge scores or high knowledge scores were less likely to have their daughters vaccinated; U.S. parents and men across all countries also were less likely to vaccinate their daughters.

Among the parents whose daughters did not receive the HPV vaccine, worry about the vaccine’s side effects was significantly more prevalent among the U.S. parents (61%) than among parents in the United Kingdom (36%) or among parents in Australia (15%) (P less than .05). U.S. parents who did not have their daughters get the HPV vaccine also were more likely to agree that getting all three HPV vaccine doses would be a “big hassle” (21%), compared with the United Kingdom cohort (0%) and the Australian cohort (8%) (P less than .05).

Parents from the United States also were significantly more likely to agree that the HPV vaccine was too new so they would want to wait before deciding to get it for their daughters (45%), compared with the parents in the United Kingdom (23%) and those in Australia (8%) (P less than .05).

“This finding was unexpected, given that advertising about HPV contributed to an increased awareness of HPV in the United States at the time of data collection. It is important to note, however, that this survey was conducted in 2011, and therefore attitudes of U.S. parents now may differ,” the researchers wrote.

Nonetheless, parents of unvaccinated daughters with higher knowledge scores overall were more likely to believe that they would want to be on the safe side and vaccinate their daughters at some time (74%) compared with parents who had lower knowledge scores (27%) (P less than .001).

“Parents from the United States with unvaccinated daughters more often believed that getting all three doses of the HPV vaccine would be a significant obstacle, not surprisingly as the HPV vaccine distribution in the United States is predominantly available through physicians’ clinics and medical centers, whereas in the United Kingdom and Australia, free school-based and catch-up programs are offered,” the investigators said.

Read more in Preventive Medicine Reports (2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.10.005).

A study comparing parental attitudes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in three countries indicates both low and high HPV knowledge may be associated with lower rates of vaccination, and parents’ country and gender also impact the likelihood of adolescents being immunized, reported Brooke Nickel, of the University of Sydney, and associates.

Of 179 parents with a daughter aged 9-17 years from the United States, United Kingdom, or Australia who took part in an online HPV vaccine opinion survey in 2011, 59% reported that their daughters had received HPV vaccination – 43% in the United States cohort, 63% in the United Kingdom cohort, and 76% in the Australian cohort.

(P less than .001). Parents who had either low knowledge scores or high knowledge scores were less likely to have their daughters vaccinated; U.S. parents and men across all countries also were less likely to vaccinate their daughters.

Among the parents whose daughters did not receive the HPV vaccine, worry about the vaccine’s side effects was significantly more prevalent among the U.S. parents (61%) than among parents in the United Kingdom (36%) or among parents in Australia (15%) (P less than .05). U.S. parents who did not have their daughters get the HPV vaccine also were more likely to agree that getting all three HPV vaccine doses would be a “big hassle” (21%), compared with the United Kingdom cohort (0%) and the Australian cohort (8%) (P less than .05).

Parents from the United States also were significantly more likely to agree that the HPV vaccine was too new so they would want to wait before deciding to get it for their daughters (45%), compared with the parents in the United Kingdom (23%) and those in Australia (8%) (P less than .05).

“This finding was unexpected, given that advertising about HPV contributed to an increased awareness of HPV in the United States at the time of data collection. It is important to note, however, that this survey was conducted in 2011, and therefore attitudes of U.S. parents now may differ,” the researchers wrote.

Nonetheless, parents of unvaccinated daughters with higher knowledge scores overall were more likely to believe that they would want to be on the safe side and vaccinate their daughters at some time (74%) compared with parents who had lower knowledge scores (27%) (P less than .001).

“Parents from the United States with unvaccinated daughters more often believed that getting all three doses of the HPV vaccine would be a significant obstacle, not surprisingly as the HPV vaccine distribution in the United States is predominantly available through physicians’ clinics and medical centers, whereas in the United Kingdom and Australia, free school-based and catch-up programs are offered,” the investigators said.

Read more in Preventive Medicine Reports (2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.10.005).

FROM PREVENTIVE MEDICINE REPORTS

Missed opportunities abound to give HPV vaccine to adolescent girls

, in a study of more than 14,000 fully insured teen girls, reported Claudia M. Espinosa, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Louisville (Ky.), and her associates.

In a study of 14,588 girls in a fully insured commercial or Medicaid plan who turned 11 years old between Jan. 1, 2010, and Sept. 31, 2015, it was documented whether or not the girls received an HPV vaccine when they were given another adolescent vaccine – one or more doses of the Tdap vaccine and/or one or more doses of the 4-valent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY vaccine).

Girls who started HPV vaccination were more likely than those who didn’t to receive the MenACWY (86% vs. 64%, respectively; P less than .0001) and Tdap (86% vs. 73%, respectively; P less than .0001) vaccines.

“A missed opportunity was defined as the absence of an HPV vaccine dose administered during any visit with a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine claim, any well-adolescent visit, or any encounter with a primary care provider, regardless of visit type,” the investigators said.

Of 10,987 visits when a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine dose was given, HPV vaccine was given at the same visit in only 37% of cases. An HPV vaccine was administered at only 26% of 12,621 of well-adolescent visits, and 42% of 14,195 other visits with primary care providers.

“The data also suggest that pediatricians and nonpediatricians alike are missing opportunities to administer the HPV vaccine when other adolescent vaccines are given,” Dr. Espinosa and her associates noted. “Future research should focus on communication strategies that might facilitate the conceptual ‘bundling’ of HPV vaccine with other adolescent vaccines in the provider’s office.”

Read more in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2017 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix067).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

, in a study of more than 14,000 fully insured teen girls, reported Claudia M. Espinosa, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Louisville (Ky.), and her associates.

In a study of 14,588 girls in a fully insured commercial or Medicaid plan who turned 11 years old between Jan. 1, 2010, and Sept. 31, 2015, it was documented whether or not the girls received an HPV vaccine when they were given another adolescent vaccine – one or more doses of the Tdap vaccine and/or one or more doses of the 4-valent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY vaccine).

Girls who started HPV vaccination were more likely than those who didn’t to receive the MenACWY (86% vs. 64%, respectively; P less than .0001) and Tdap (86% vs. 73%, respectively; P less than .0001) vaccines.

“A missed opportunity was defined as the absence of an HPV vaccine dose administered during any visit with a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine claim, any well-adolescent visit, or any encounter with a primary care provider, regardless of visit type,” the investigators said.

Of 10,987 visits when a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine dose was given, HPV vaccine was given at the same visit in only 37% of cases. An HPV vaccine was administered at only 26% of 12,621 of well-adolescent visits, and 42% of 14,195 other visits with primary care providers.

“The data also suggest that pediatricians and nonpediatricians alike are missing opportunities to administer the HPV vaccine when other adolescent vaccines are given,” Dr. Espinosa and her associates noted. “Future research should focus on communication strategies that might facilitate the conceptual ‘bundling’ of HPV vaccine with other adolescent vaccines in the provider’s office.”

Read more in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2017 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix067).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

, in a study of more than 14,000 fully insured teen girls, reported Claudia M. Espinosa, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Louisville (Ky.), and her associates.

In a study of 14,588 girls in a fully insured commercial or Medicaid plan who turned 11 years old between Jan. 1, 2010, and Sept. 31, 2015, it was documented whether or not the girls received an HPV vaccine when they were given another adolescent vaccine – one or more doses of the Tdap vaccine and/or one or more doses of the 4-valent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY vaccine).

Girls who started HPV vaccination were more likely than those who didn’t to receive the MenACWY (86% vs. 64%, respectively; P less than .0001) and Tdap (86% vs. 73%, respectively; P less than .0001) vaccines.

“A missed opportunity was defined as the absence of an HPV vaccine dose administered during any visit with a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine claim, any well-adolescent visit, or any encounter with a primary care provider, regardless of visit type,” the investigators said.

Of 10,987 visits when a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine dose was given, HPV vaccine was given at the same visit in only 37% of cases. An HPV vaccine was administered at only 26% of 12,621 of well-adolescent visits, and 42% of 14,195 other visits with primary care providers.

“The data also suggest that pediatricians and nonpediatricians alike are missing opportunities to administer the HPV vaccine when other adolescent vaccines are given,” Dr. Espinosa and her associates noted. “Future research should focus on communication strategies that might facilitate the conceptual ‘bundling’ of HPV vaccine with other adolescent vaccines in the provider’s office.”

Read more in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2017 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix067).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SOCIETY

What to do about the problem of non-FDA approved compounded bioidentical hormones

VIDEO: Intermittent furosemide during acute HFpEF favors kidneys

DALLAS – Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction who were hospitalized for acute decompensation had a significantly smaller rise in serum creatinine when treated with intermittent, bolus doses of furosemide, compared with patients who received a continuous furosemide infusion in a single-center, randomized trial with 90 patients.

Intermittent furosemide also resulted in many fewer episodes of worsening renal function. In the trial, 12% of patients who received bolus furosemide doses developed worsening renal function during hospitalization compared with 36% of patients treated with a continuous furosemide infusion, Kavita Sharma, MD, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

While acknowledging that this finding is preliminary because it was made in a relatively small, single-center study, “I’d be cautious about continuous infusion” in acute decompensated patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF); “bolus is preferred,” Dr. Sharma said in a video interview.

Results from the prior Diuretic Optimization Strategies Evaluation (DOSE) trial, published in 2011, had shown no significant difference in renal function in hospitalized heart failure patients randomized to receive either bolus or continuous furosemide, but that study largely enrolled patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 3;364[9]:797-805).

“When patients with HFpEF are hospitalized with acute heart failure there is a high rate of kidney injury, that often results in slowing diuresis leading to longer hospital stays. With adjustment for changes in blood pressure and volume of diuresis we saw a fourfold increase in worsening renal failure [with continuous infusion], so you should think twice before using continuous dosing,” said Dr. Sharma, a heart failure cardiologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

She presented results from Diuretics and Dopamine in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (ROPA-DOP), which randomized 90 hospitalized heart failure patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of at least 50% and an estimated glomerular filtration rate of more than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2. The enrolled patients averaged 66 years old, 61% were women, their average body mass index was 41 kg/m2, and their average estimated glomerular filtration rate was 58 mL/min/1.73 m2.