User login

CVS selling low-cost generic epinephrine autoinjector

CVS Pharmacy is currently selling a generic epinephrine autoinjector for a price of $109.99 per two-pack, which is about one-sixth the cost of Mylan’s EpiPen two-pack.

The product, an authorized generic for Adrenaclick, is manufactured by Lineage Therapeutics, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of Fort Washington, Pa.–based Impax Laboratories. CVS Pharmacy characterized the product as having “the lowest cash price in the market” and said in a Jan. 12 statement that the move was undertaken to address the “urgent need for a less-expensive epinephrine autoinjector.”

Data from a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis found that the average total Part D Medicare spending per EpiPen prescription increased nearly fivefold, from an average of $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014. This trend continued, and in September 2016, Mylan’s CEO Heather Bresch faced questioning on Capitol Hill about the price hikes from members of the House Oversight Committee.

“We’re encouraged to see national efforts to make epinephrine autoinjectors more affordable and more available to Americans across the country,” Cary Sennett, MD, PhD, president and CEO of the Landover, Md.–based Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, said in the CVS statement. “Partnerships that increase access to vital medications are key in helping those suffering from life-threatening allergies.”

CVS Pharmacy is currently selling a generic epinephrine autoinjector for a price of $109.99 per two-pack, which is about one-sixth the cost of Mylan’s EpiPen two-pack.

The product, an authorized generic for Adrenaclick, is manufactured by Lineage Therapeutics, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of Fort Washington, Pa.–based Impax Laboratories. CVS Pharmacy characterized the product as having “the lowest cash price in the market” and said in a Jan. 12 statement that the move was undertaken to address the “urgent need for a less-expensive epinephrine autoinjector.”

Data from a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis found that the average total Part D Medicare spending per EpiPen prescription increased nearly fivefold, from an average of $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014. This trend continued, and in September 2016, Mylan’s CEO Heather Bresch faced questioning on Capitol Hill about the price hikes from members of the House Oversight Committee.

“We’re encouraged to see national efforts to make epinephrine autoinjectors more affordable and more available to Americans across the country,” Cary Sennett, MD, PhD, president and CEO of the Landover, Md.–based Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, said in the CVS statement. “Partnerships that increase access to vital medications are key in helping those suffering from life-threatening allergies.”

CVS Pharmacy is currently selling a generic epinephrine autoinjector for a price of $109.99 per two-pack, which is about one-sixth the cost of Mylan’s EpiPen two-pack.

The product, an authorized generic for Adrenaclick, is manufactured by Lineage Therapeutics, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of Fort Washington, Pa.–based Impax Laboratories. CVS Pharmacy characterized the product as having “the lowest cash price in the market” and said in a Jan. 12 statement that the move was undertaken to address the “urgent need for a less-expensive epinephrine autoinjector.”

Data from a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis found that the average total Part D Medicare spending per EpiPen prescription increased nearly fivefold, from an average of $71 in 2007 to $344 in 2014. This trend continued, and in September 2016, Mylan’s CEO Heather Bresch faced questioning on Capitol Hill about the price hikes from members of the House Oversight Committee.

“We’re encouraged to see national efforts to make epinephrine autoinjectors more affordable and more available to Americans across the country,” Cary Sennett, MD, PhD, president and CEO of the Landover, Md.–based Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, said in the CVS statement. “Partnerships that increase access to vital medications are key in helping those suffering from life-threatening allergies.”

‘Anxiety sensitivity’ tied to psychodermatologic disorders

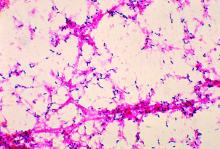

Adult patients who experience stress in the form of “anxiety sensitivity” are more likely to develop psychodermatological conditions than those that are not psychodermatological, a cross-sectional study of 115 participants shows.

“The results suggest that [anxiety sensitivity] interventions combined with dermatology treatments may be beneficial for psychodermatological patients,” wrote Laura J. Dixon, PhD, of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and her associates. “There is strong evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduces [anxiety sensitivity] through strategies such as psychoeducation, interoceptive exposure, and cognitive therapy.”

Dr. Dixon and her associates recruited 123 dermatologic patients aged 18-83 years over 30 weeks through three outpatient university dermatology clinics in Central Mississippi. Sixty-five percent of the participants were white, 33% were black, 1% were Asian, and 1% were Native American; 65% were female. Most of the patients were married and living with their spouses. The final sample of participants comprised 63 psychodermatological patients and 52 nonpsychodermatological patients (Psychosomatics. 2016;57:498-504).

The investigators assessed general anxiety symptoms using the 7-item depression, anxiety, and stress subscale (DASS-A) from the 21-item version of the questionnaire (DASS-21). Anxiety sensitivity – which refers to the “extent of beliefs that anxiety symptoms or arousal can have harmful consequences” (Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2011 Fall;22[3]:187-93) – was measured using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index–3 (ASI-3, an 18-item self-report instrument that assesses physical manifestations of anxiety, such as blushing and fast heart beating.

Psychodermatological conditions were classified as disorders that might be rooted in or made worse by psychological, behavioral, or stress-related factors. Conditions in this category include acne, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, eczema, hidradenitis, prurigo, psoriasis, and rosacea. Dermatologic conditions not tied to psychological factors and classified as biologically based include brittle fingernails, cysts, keloids, rashes, skin cancer, skin lesions, spider veins, and warts, reported Dr. Dixon.

No significant differences were observed on the DASS-A scores between the two groups.

The mean scores of psychodermatological patients on the ASI-3 were significantly higher than the scores of patients with nonpsychodermatological conditions (21.1 vs. 13.7; P = .013). In fact, Dr. Dixon and her associates found that “each 1-unit increment in the ASI-3 social subscale score was associated with a 12.7% increased odds of patients having a psychodermatological condition.”

“Taken together, these results are supported by existing theoretical models of psychodermatological disorders that highlight the importance of stress among patients with certain dermatological conditions,” the researchers wrote.

One of the authors, dermatologist Robert T. Brodell, disclosed receiving honoraria from Allergan, Galderma Laboratories, and PharmaDerm; he also disclosed receiving consultant fees and performing clinical trials for other pharmaceutical companies. Neither Dr. Dixon nor any of the other authors declared relevant financial disclosures.

Adult patients who experience stress in the form of “anxiety sensitivity” are more likely to develop psychodermatological conditions than those that are not psychodermatological, a cross-sectional study of 115 participants shows.

“The results suggest that [anxiety sensitivity] interventions combined with dermatology treatments may be beneficial for psychodermatological patients,” wrote Laura J. Dixon, PhD, of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and her associates. “There is strong evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduces [anxiety sensitivity] through strategies such as psychoeducation, interoceptive exposure, and cognitive therapy.”

Dr. Dixon and her associates recruited 123 dermatologic patients aged 18-83 years over 30 weeks through three outpatient university dermatology clinics in Central Mississippi. Sixty-five percent of the participants were white, 33% were black, 1% were Asian, and 1% were Native American; 65% were female. Most of the patients were married and living with their spouses. The final sample of participants comprised 63 psychodermatological patients and 52 nonpsychodermatological patients (Psychosomatics. 2016;57:498-504).

The investigators assessed general anxiety symptoms using the 7-item depression, anxiety, and stress subscale (DASS-A) from the 21-item version of the questionnaire (DASS-21). Anxiety sensitivity – which refers to the “extent of beliefs that anxiety symptoms or arousal can have harmful consequences” (Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2011 Fall;22[3]:187-93) – was measured using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index–3 (ASI-3, an 18-item self-report instrument that assesses physical manifestations of anxiety, such as blushing and fast heart beating.

Psychodermatological conditions were classified as disorders that might be rooted in or made worse by psychological, behavioral, or stress-related factors. Conditions in this category include acne, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, eczema, hidradenitis, prurigo, psoriasis, and rosacea. Dermatologic conditions not tied to psychological factors and classified as biologically based include brittle fingernails, cysts, keloids, rashes, skin cancer, skin lesions, spider veins, and warts, reported Dr. Dixon.

No significant differences were observed on the DASS-A scores between the two groups.

The mean scores of psychodermatological patients on the ASI-3 were significantly higher than the scores of patients with nonpsychodermatological conditions (21.1 vs. 13.7; P = .013). In fact, Dr. Dixon and her associates found that “each 1-unit increment in the ASI-3 social subscale score was associated with a 12.7% increased odds of patients having a psychodermatological condition.”

“Taken together, these results are supported by existing theoretical models of psychodermatological disorders that highlight the importance of stress among patients with certain dermatological conditions,” the researchers wrote.

One of the authors, dermatologist Robert T. Brodell, disclosed receiving honoraria from Allergan, Galderma Laboratories, and PharmaDerm; he also disclosed receiving consultant fees and performing clinical trials for other pharmaceutical companies. Neither Dr. Dixon nor any of the other authors declared relevant financial disclosures.

Adult patients who experience stress in the form of “anxiety sensitivity” are more likely to develop psychodermatological conditions than those that are not psychodermatological, a cross-sectional study of 115 participants shows.

“The results suggest that [anxiety sensitivity] interventions combined with dermatology treatments may be beneficial for psychodermatological patients,” wrote Laura J. Dixon, PhD, of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, and her associates. “There is strong evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduces [anxiety sensitivity] through strategies such as psychoeducation, interoceptive exposure, and cognitive therapy.”

Dr. Dixon and her associates recruited 123 dermatologic patients aged 18-83 years over 30 weeks through three outpatient university dermatology clinics in Central Mississippi. Sixty-five percent of the participants were white, 33% were black, 1% were Asian, and 1% were Native American; 65% were female. Most of the patients were married and living with their spouses. The final sample of participants comprised 63 psychodermatological patients and 52 nonpsychodermatological patients (Psychosomatics. 2016;57:498-504).

The investigators assessed general anxiety symptoms using the 7-item depression, anxiety, and stress subscale (DASS-A) from the 21-item version of the questionnaire (DASS-21). Anxiety sensitivity – which refers to the “extent of beliefs that anxiety symptoms or arousal can have harmful consequences” (Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2011 Fall;22[3]:187-93) – was measured using the Anxiety Sensitivity Index–3 (ASI-3, an 18-item self-report instrument that assesses physical manifestations of anxiety, such as blushing and fast heart beating.

Psychodermatological conditions were classified as disorders that might be rooted in or made worse by psychological, behavioral, or stress-related factors. Conditions in this category include acne, alopecia, atopic dermatitis, eczema, hidradenitis, prurigo, psoriasis, and rosacea. Dermatologic conditions not tied to psychological factors and classified as biologically based include brittle fingernails, cysts, keloids, rashes, skin cancer, skin lesions, spider veins, and warts, reported Dr. Dixon.

No significant differences were observed on the DASS-A scores between the two groups.

The mean scores of psychodermatological patients on the ASI-3 were significantly higher than the scores of patients with nonpsychodermatological conditions (21.1 vs. 13.7; P = .013). In fact, Dr. Dixon and her associates found that “each 1-unit increment in the ASI-3 social subscale score was associated with a 12.7% increased odds of patients having a psychodermatological condition.”

“Taken together, these results are supported by existing theoretical models of psychodermatological disorders that highlight the importance of stress among patients with certain dermatological conditions,” the researchers wrote.

One of the authors, dermatologist Robert T. Brodell, disclosed receiving honoraria from Allergan, Galderma Laboratories, and PharmaDerm; he also disclosed receiving consultant fees and performing clinical trials for other pharmaceutical companies. Neither Dr. Dixon nor any of the other authors declared relevant financial disclosures.

Smoking-cessation interest and success vary by race, ethnicity

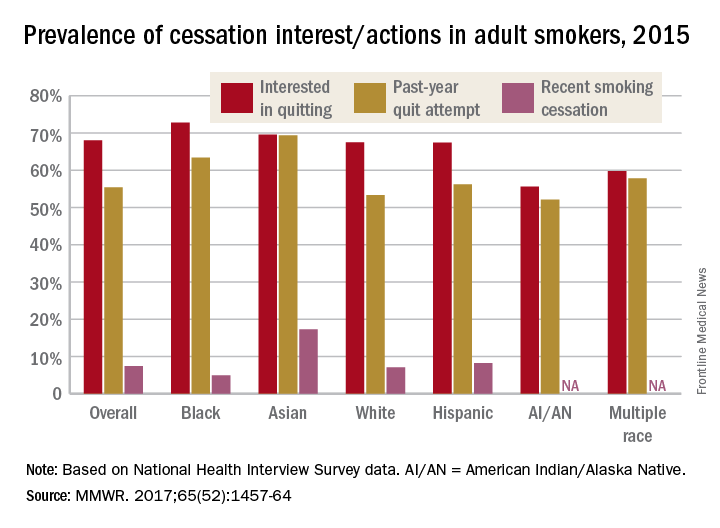

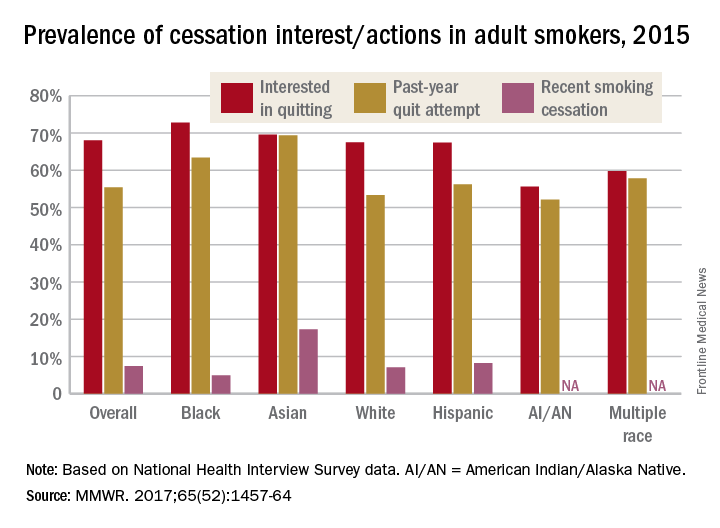

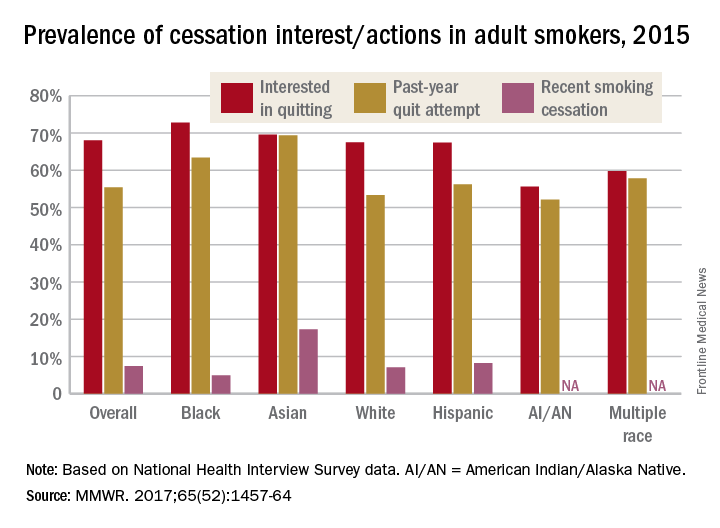

Just over 55% of adult cigarette smokers made an attempt to quit in the past year, and 7.4% said that they recently quit, according to investigators from the Centers or Disease Control and Prevention.

Data from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that 68% of cigarette smokers were interested in quitting, with considerable variation seen according to race and ethnicity (MMWR. 2017;65[52]:1457-64).

American Indian/Alaska Native smokers were the least likely to be interested in quitting (55.6%) and to have attempted to quit (52.1%), but the sample size was too small to report a reliable quit rate. The amount of survey participants of multiple races was also too small to report a reliable quit rate. Among that group, 59.8% were interested in quitting and 57.8% had attempted to quit in the past year, the NHIS data showed.

The sizes of surveyed populations for individual races and ethnicities were not reported, but the total sample size for the 2015 NHIS was 33,672.

Just over 55% of adult cigarette smokers made an attempt to quit in the past year, and 7.4% said that they recently quit, according to investigators from the Centers or Disease Control and Prevention.

Data from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that 68% of cigarette smokers were interested in quitting, with considerable variation seen according to race and ethnicity (MMWR. 2017;65[52]:1457-64).

American Indian/Alaska Native smokers were the least likely to be interested in quitting (55.6%) and to have attempted to quit (52.1%), but the sample size was too small to report a reliable quit rate. The amount of survey participants of multiple races was also too small to report a reliable quit rate. Among that group, 59.8% were interested in quitting and 57.8% had attempted to quit in the past year, the NHIS data showed.

The sizes of surveyed populations for individual races and ethnicities were not reported, but the total sample size for the 2015 NHIS was 33,672.

Just over 55% of adult cigarette smokers made an attempt to quit in the past year, and 7.4% said that they recently quit, according to investigators from the Centers or Disease Control and Prevention.

Data from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that 68% of cigarette smokers were interested in quitting, with considerable variation seen according to race and ethnicity (MMWR. 2017;65[52]:1457-64).

American Indian/Alaska Native smokers were the least likely to be interested in quitting (55.6%) and to have attempted to quit (52.1%), but the sample size was too small to report a reliable quit rate. The amount of survey participants of multiple races was also too small to report a reliable quit rate. Among that group, 59.8% were interested in quitting and 57.8% had attempted to quit in the past year, the NHIS data showed.

The sizes of surveyed populations for individual races and ethnicities were not reported, but the total sample size for the 2015 NHIS was 33,672.

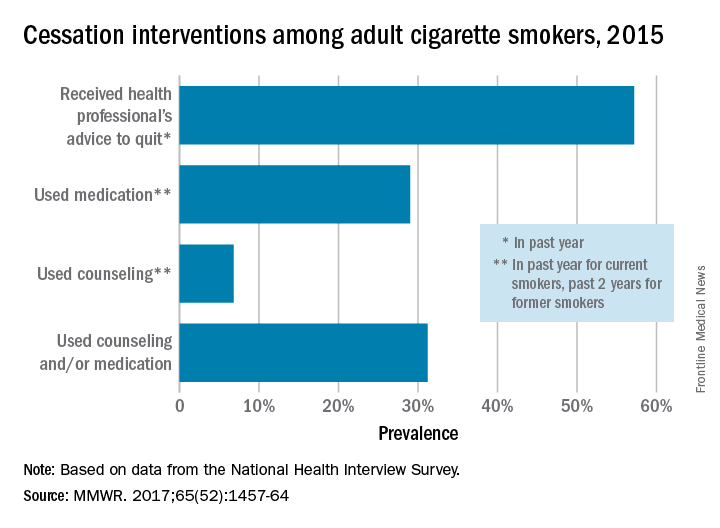

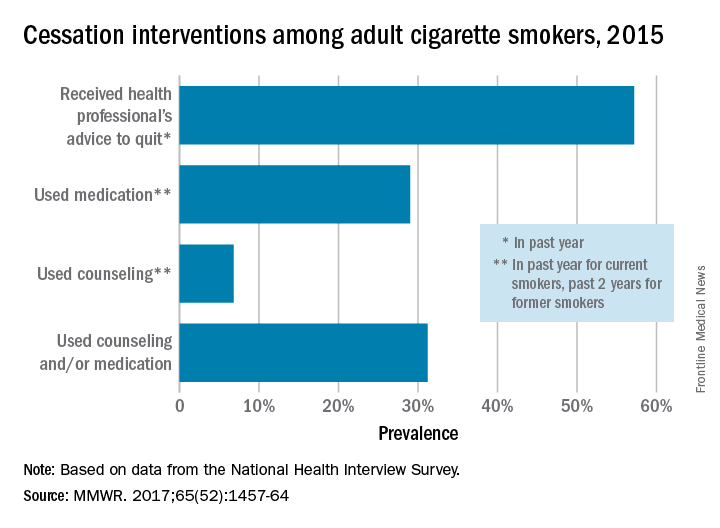

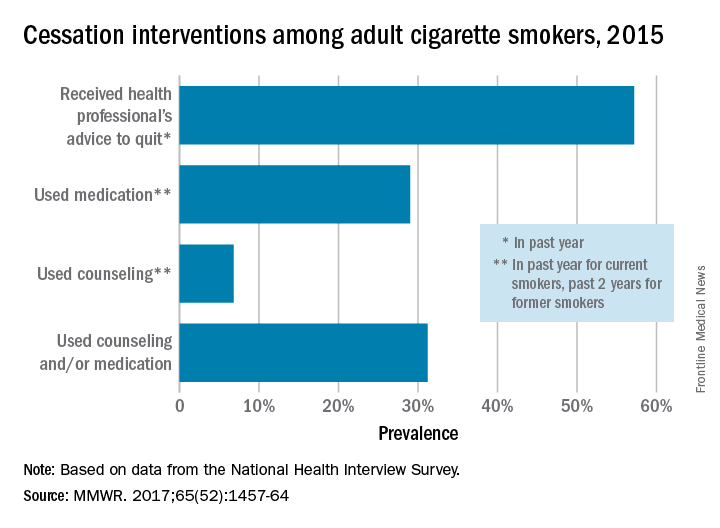

Most cigarette smokers attempt to quit without evidence-based techniques

More than half of cigarette smokers have received advice to quit from a health care professional, but less than a third used medication or counseling in their cessation attempt, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, just over 57% of adult smokers said that a health care professional had advised them to quit in the past year. Of those who tried to quit, 29% used medication such as nicotine patches or gum, varenicline, or bupropion; 7% used counseling (including a stop-smoking clinic, class, or support group and a telephone help line); and 31% used counseling and/or medication, the investigators reported (MMWR 2017;65[52]:1457-64).

With the overall cessation rate at less than 10%, “it is critical for health care providers to consistently identify smokers, advise them to quit, and offer evidence-based cessation treatments, and for insurers to cover and promote the use of these treatments and remove barriers to accessing them,” the investigators wrote.

More than half of cigarette smokers have received advice to quit from a health care professional, but less than a third used medication or counseling in their cessation attempt, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, just over 57% of adult smokers said that a health care professional had advised them to quit in the past year. Of those who tried to quit, 29% used medication such as nicotine patches or gum, varenicline, or bupropion; 7% used counseling (including a stop-smoking clinic, class, or support group and a telephone help line); and 31% used counseling and/or medication, the investigators reported (MMWR 2017;65[52]:1457-64).

With the overall cessation rate at less than 10%, “it is critical for health care providers to consistently identify smokers, advise them to quit, and offer evidence-based cessation treatments, and for insurers to cover and promote the use of these treatments and remove barriers to accessing them,” the investigators wrote.

More than half of cigarette smokers have received advice to quit from a health care professional, but less than a third used medication or counseling in their cessation attempt, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, just over 57% of adult smokers said that a health care professional had advised them to quit in the past year. Of those who tried to quit, 29% used medication such as nicotine patches or gum, varenicline, or bupropion; 7% used counseling (including a stop-smoking clinic, class, or support group and a telephone help line); and 31% used counseling and/or medication, the investigators reported (MMWR 2017;65[52]:1457-64).

With the overall cessation rate at less than 10%, “it is critical for health care providers to consistently identify smokers, advise them to quit, and offer evidence-based cessation treatments, and for insurers to cover and promote the use of these treatments and remove barriers to accessing them,” the investigators wrote.

FROM MMWR

Circulating microRNAs may predict breast cancer treatment response

SAN ANTONIO – Circulating microRNAs may predict treatment response in HER2-positive breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy, according to findings from the randomized phase III NeoALTTO trial.

Specifically, four circulating tumor microRNA signatures were found to predict pathologic complete response to specific treatments at specific time points in a “testing set” of patients from the study, Serena Di Cosimo, MD, of Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Overall results from the trial, which were reported in 2012 (The Lancet. 379[9816]:633-40) showed that the combination of lapatinib and trastuzumab significantly improved rates of pathologic complete response, compared with either drug alone in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer, and the authors concluded that dual inhibition of HER2 might be a valid approach in such patients in the neoadjuvant treatment setting.

For the current analysis of NeoALTTO data, microRNA from plasma samples from 435 women – 141 treated with lapatinib, 151 treated with trastuzumab, and 143 treated with a combination of the two – were monitored longitudinally, as NeoALTTO “was done thinking about future translational studies, so blood samples were collected prospectively at baseline, after 2 weeks of treatment, at surgery, and at the time of relapse,” she noted.

Potential microRNAs associated with pathologic complete response were identified for each treatment arm and time point, and a multivariate model was used to identify specific signatures and their predictive capability.

A total of 30 microRNAs and 6 microRNA signatures were found to be predict pathologic complete response in a “training population,” and the predictive ability of 4 of those was confirmed in the testing set for lapatinib at baseline (area under the curve [AUC] = .86), lapatinib after 2 weeks (AUC = .71), trastuzumab after 2 weeks (AUC=.81), and lapatinib and trastuzumab after 2 weeks (AUC = .67), Dr. Di Cosimo said.

“Results obtained early post treatment are of special value,” she said, explaining that “women with unfavorable microRNA signatures can be expected to have poor response after just 2 weeks of treatment.”

The findings are of note because a significant proportion of breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant setting do not achieve pathologic complete response and have an increased risk of relapse after surgery. Further, there is a lack of reliable predictors of response to help guide therapy in clinical practice, Dr. Ci Cosimo said.

“This is the first evidence of the potential of circulating microRNAs to discriminate between responsive and unresponsive HER2+ breast cancer patients,” she said.

At present, the signatures, overall, have been associated with pathologic complete response, but not event-free survival. However, one microRNA signature (140-5p) appeared to be associated with event-free survival after 2 weeks among patients treated with trastuzumab, she said, adding that functional studies are ongoing to investigate the biological role of microRNAs, and independent validation studies are planned.

Dr. Di Cosimo reported having no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Circulating microRNAs may predict treatment response in HER2-positive breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy, according to findings from the randomized phase III NeoALTTO trial.

Specifically, four circulating tumor microRNA signatures were found to predict pathologic complete response to specific treatments at specific time points in a “testing set” of patients from the study, Serena Di Cosimo, MD, of Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Overall results from the trial, which were reported in 2012 (The Lancet. 379[9816]:633-40) showed that the combination of lapatinib and trastuzumab significantly improved rates of pathologic complete response, compared with either drug alone in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer, and the authors concluded that dual inhibition of HER2 might be a valid approach in such patients in the neoadjuvant treatment setting.

For the current analysis of NeoALTTO data, microRNA from plasma samples from 435 women – 141 treated with lapatinib, 151 treated with trastuzumab, and 143 treated with a combination of the two – were monitored longitudinally, as NeoALTTO “was done thinking about future translational studies, so blood samples were collected prospectively at baseline, after 2 weeks of treatment, at surgery, and at the time of relapse,” she noted.

Potential microRNAs associated with pathologic complete response were identified for each treatment arm and time point, and a multivariate model was used to identify specific signatures and their predictive capability.

A total of 30 microRNAs and 6 microRNA signatures were found to be predict pathologic complete response in a “training population,” and the predictive ability of 4 of those was confirmed in the testing set for lapatinib at baseline (area under the curve [AUC] = .86), lapatinib after 2 weeks (AUC = .71), trastuzumab after 2 weeks (AUC=.81), and lapatinib and trastuzumab after 2 weeks (AUC = .67), Dr. Di Cosimo said.

“Results obtained early post treatment are of special value,” she said, explaining that “women with unfavorable microRNA signatures can be expected to have poor response after just 2 weeks of treatment.”

The findings are of note because a significant proportion of breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant setting do not achieve pathologic complete response and have an increased risk of relapse after surgery. Further, there is a lack of reliable predictors of response to help guide therapy in clinical practice, Dr. Ci Cosimo said.

“This is the first evidence of the potential of circulating microRNAs to discriminate between responsive and unresponsive HER2+ breast cancer patients,” she said.

At present, the signatures, overall, have been associated with pathologic complete response, but not event-free survival. However, one microRNA signature (140-5p) appeared to be associated with event-free survival after 2 weeks among patients treated with trastuzumab, she said, adding that functional studies are ongoing to investigate the biological role of microRNAs, and independent validation studies are planned.

Dr. Di Cosimo reported having no disclosures.

SAN ANTONIO – Circulating microRNAs may predict treatment response in HER2-positive breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy, according to findings from the randomized phase III NeoALTTO trial.

Specifically, four circulating tumor microRNA signatures were found to predict pathologic complete response to specific treatments at specific time points in a “testing set” of patients from the study, Serena Di Cosimo, MD, of Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Overall results from the trial, which were reported in 2012 (The Lancet. 379[9816]:633-40) showed that the combination of lapatinib and trastuzumab significantly improved rates of pathologic complete response, compared with either drug alone in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer, and the authors concluded that dual inhibition of HER2 might be a valid approach in such patients in the neoadjuvant treatment setting.

For the current analysis of NeoALTTO data, microRNA from plasma samples from 435 women – 141 treated with lapatinib, 151 treated with trastuzumab, and 143 treated with a combination of the two – were monitored longitudinally, as NeoALTTO “was done thinking about future translational studies, so blood samples were collected prospectively at baseline, after 2 weeks of treatment, at surgery, and at the time of relapse,” she noted.

Potential microRNAs associated with pathologic complete response were identified for each treatment arm and time point, and a multivariate model was used to identify specific signatures and their predictive capability.

A total of 30 microRNAs and 6 microRNA signatures were found to be predict pathologic complete response in a “training population,” and the predictive ability of 4 of those was confirmed in the testing set for lapatinib at baseline (area under the curve [AUC] = .86), lapatinib after 2 weeks (AUC = .71), trastuzumab after 2 weeks (AUC=.81), and lapatinib and trastuzumab after 2 weeks (AUC = .67), Dr. Di Cosimo said.

“Results obtained early post treatment are of special value,” she said, explaining that “women with unfavorable microRNA signatures can be expected to have poor response after just 2 weeks of treatment.”

The findings are of note because a significant proportion of breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant setting do not achieve pathologic complete response and have an increased risk of relapse after surgery. Further, there is a lack of reliable predictors of response to help guide therapy in clinical practice, Dr. Ci Cosimo said.

“This is the first evidence of the potential of circulating microRNAs to discriminate between responsive and unresponsive HER2+ breast cancer patients,” she said.

At present, the signatures, overall, have been associated with pathologic complete response, but not event-free survival. However, one microRNA signature (140-5p) appeared to be associated with event-free survival after 2 weeks among patients treated with trastuzumab, she said, adding that functional studies are ongoing to investigate the biological role of microRNAs, and independent validation studies are planned.

Dr. Di Cosimo reported having no disclosures.

AT SABCS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 30 microRNAs and 6 microRNA signatures were found to predict pathologic complete response in a “training population,” and the predictive ability of 4 of those was confirmed in the testing set.

Data source: An analysis of data from the randomized phase III NeoALTTO trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Di Cosimo reported having no disclosures.

Senate, House take first step toward repealing ACA

With a Jan. 12 early morning procedural passed on party lines, the Senate has set the stage for the repeal of the revenue aspects of the Affordable Care Act. The House of Representatives passed similar legislation Jan. 13.*

Republicans will be using the budget reconciliation process, which will allow them to move forward with repealing certain provisions of the health care reform law without any Democratic support, although passage of any replacement will require some bipartisan support as Republicans do not have the required 60 votes to guarantee passage in the Senate.

The budget resolutions contain no details about what could be repealed or whether there will be a replacement, but it does direct the key committees to write draft legislation by Jan. 27.

Senate Republicans “plan to rescue those trapped in a failing system, to replace that system with a functional market, or markets, and then repeal Obamacare for good,” he said.

Sen. Alexander said the process will come in three parts. The first will protect the 11 million people who have purchased health insurance through the exchanges so that they don’t lose coverage.

“Second, we will build better systems providing Americans with more choices that cost less,” he said. “Note I say systems, not one system. If anyone is expecting [Senate Majority Leader Mitch] McConnell [R-Ky.] to roll a wheelbarrow on the Senate floor with a comprehensive Republican health care plan, they’re going to be waiting a long time because we don’t believe in that. We don’t want to replace a failed Obamacare federal system with another failed federal system.”

The last part will be to repeal what remains of the law after the new plan is in place.

Sen. Alexander reiterated that any future bill will keep the ban on coverage denials for preexisting conditions and the allowance of coverage of children up to the age of 26 who are on their parents’ plans.

He stated that this reform effort will not address Medicare reform, which will be the subject of separate legislative action.

*This story was updated Jan. 13 at 4:30 pm.

With a Jan. 12 early morning procedural passed on party lines, the Senate has set the stage for the repeal of the revenue aspects of the Affordable Care Act. The House of Representatives passed similar legislation Jan. 13.*

Republicans will be using the budget reconciliation process, which will allow them to move forward with repealing certain provisions of the health care reform law without any Democratic support, although passage of any replacement will require some bipartisan support as Republicans do not have the required 60 votes to guarantee passage in the Senate.

The budget resolutions contain no details about what could be repealed or whether there will be a replacement, but it does direct the key committees to write draft legislation by Jan. 27.

Senate Republicans “plan to rescue those trapped in a failing system, to replace that system with a functional market, or markets, and then repeal Obamacare for good,” he said.

Sen. Alexander said the process will come in three parts. The first will protect the 11 million people who have purchased health insurance through the exchanges so that they don’t lose coverage.

“Second, we will build better systems providing Americans with more choices that cost less,” he said. “Note I say systems, not one system. If anyone is expecting [Senate Majority Leader Mitch] McConnell [R-Ky.] to roll a wheelbarrow on the Senate floor with a comprehensive Republican health care plan, they’re going to be waiting a long time because we don’t believe in that. We don’t want to replace a failed Obamacare federal system with another failed federal system.”

The last part will be to repeal what remains of the law after the new plan is in place.

Sen. Alexander reiterated that any future bill will keep the ban on coverage denials for preexisting conditions and the allowance of coverage of children up to the age of 26 who are on their parents’ plans.

He stated that this reform effort will not address Medicare reform, which will be the subject of separate legislative action.

*This story was updated Jan. 13 at 4:30 pm.

With a Jan. 12 early morning procedural passed on party lines, the Senate has set the stage for the repeal of the revenue aspects of the Affordable Care Act. The House of Representatives passed similar legislation Jan. 13.*

Republicans will be using the budget reconciliation process, which will allow them to move forward with repealing certain provisions of the health care reform law without any Democratic support, although passage of any replacement will require some bipartisan support as Republicans do not have the required 60 votes to guarantee passage in the Senate.

The budget resolutions contain no details about what could be repealed or whether there will be a replacement, but it does direct the key committees to write draft legislation by Jan. 27.

Senate Republicans “plan to rescue those trapped in a failing system, to replace that system with a functional market, or markets, and then repeal Obamacare for good,” he said.

Sen. Alexander said the process will come in three parts. The first will protect the 11 million people who have purchased health insurance through the exchanges so that they don’t lose coverage.

“Second, we will build better systems providing Americans with more choices that cost less,” he said. “Note I say systems, not one system. If anyone is expecting [Senate Majority Leader Mitch] McConnell [R-Ky.] to roll a wheelbarrow on the Senate floor with a comprehensive Republican health care plan, they’re going to be waiting a long time because we don’t believe in that. We don’t want to replace a failed Obamacare federal system with another failed federal system.”

The last part will be to repeal what remains of the law after the new plan is in place.

Sen. Alexander reiterated that any future bill will keep the ban on coverage denials for preexisting conditions and the allowance of coverage of children up to the age of 26 who are on their parents’ plans.

He stated that this reform effort will not address Medicare reform, which will be the subject of separate legislative action.

*This story was updated Jan. 13 at 4:30 pm.

Complications and Risk Factors for Morbidity in Elective Hip Arthroscopy: A Review of 1325 Cases

Take-Home Points

- Using the NSQIP database, the authors report that the overall complication rate was 1.21% after hip arthroscopy.

- The most common complications cited were bleeding requiring transfusion (0.45%), return to OR (0.23%), superficial infection (0.23%), and thrombophlebitis (0.15).

- Most common 10CPT code was arthroscopic débridement in 50% of cases, reflecting the types of cases being performed in the time period.

- FAI codes were less common in this database–labral repair in 24%, femoral osteochondroplasty in 16%, and acetabuloplasty in 9%.

- Use caution in patients over age 65 years as this appears to be a risk factor for morbidity.

Hip arthroscopy is a well-described method for treating a number of pathologies.1-3 Surgical indications are wide-ranging and include femoral acetabular impingement (FAI), labral tears, loose bodies, osteochondral injuries, ruptured ligamentum teres, and synovitis, as well as extra-articular injuries, including hip abductor tears and sciatic nerve entrapment.2,4-6 Authors have suggested that the advantages of hip arthroscopy over open procedures include less traumatic access to the hip joint and faster recovery,7,8 and hip arthroscopy has been found cost-effective in select groups of patients.9

Overall complications have been reported in 1% to 20% of hip arthroscopy patients,6,8,10,11 and a meta-analysis identified an overall complication rate of 4%.8 Complications include iatrogenic chondrolabral injury, nerve injury, superficial surgical-site infection, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), instrument failure, portal wound bleeding, soft-tissue injury, and intra-abdominal fluid extravasation.6,8,10-13 Rates of major complications are relatively low, 0.3% to 0.58%, according to several recent systematic reviews.8,12 Given the lack of universally accepted definitions, reports of minor complications (eg, iatrogenic chondrolabral injury, neuropraxia) in hip arthroscopy vary widely.8 Furthermore, many of the series with high complication rates represent early experience with the technique, and later authors suggested that complications should decrease with improvements in technique and technology.12,14,15The literature is lacking in reports of risk factors for patient morbidity and large multi-institutional cohorts in the setting of hip arthroscopy. We conducted a study of elective hip arthroscopy patients to determine type and incidence of complications and rates of and risk factors for minor and major morbidity.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was deemed compliant with HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) and exempt from the need for Institutional Review Board approval. In the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), academic and private medical institutions prospectively collect patient preoperative and operative data as well as 30-day outcome data from more than 500 hospitals throughout the United States.16-21 Surgical clinical reviewers, who are responsible for data acquisition, prospectively collect morbidity data for 30 days after surgery through a chart review of patient progress notes, operative notes, and follow-up clinic visits. Patients may be contacted by a surgical clinical reviewer if they have not had a clinic visit within 30 days after a procedure to verify the presence or absence of complications or admissions at outside institutions, and in this way even outpatient complications should be captured. If the medical record is unclear, the reviewer may also contact the surgeon directly. In addition, NSQIP data are routinely audited; the interobserver disagreement rate is 1.56%.22

We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) billing codes to retrospectively survey the NSQIP database for hip arthroscopies performed between 2006 and 2013. Excluding cases of compromised surgical wounds, emergent surgeries, surgeries involving fracture, hip dislocations, preoperative sepsis, septic joints, and osteomyelitis, we identified 1325 cases with CPT codes 29861 (hip arthroscopy), 29862 (arthroscopic hip débridement, shaving), 29914 (arthroscopic femoroplasty), 29915 (arthroscopic acetabuloplasty), and 29916 (arthroscopic labral repair). Postoperative outcomes were categorized as major morbidity or mortality, minor morbidity, and any complication. A major complication was a systemic life-threatening event or a substantial threat to a vital organ, whereas a minor complication did not pose a major systemic threat and was localized to the operative extremity (previously used definitions23,24). We have used similar methods to report the rates of and risk factors for complications of knee arthroscopy, shoulder arthroscopy, and total shoulder arthroplasty.16,20,21 For any-complication outcomes, we included both major and minor morbidities, and mortality. NSQIP applies strict definitions (listed in its user file17) to patient comorbidities and complications. Data points collected included patient demographics, medical comorbidities, laboratory values, and surgical characteristics.

Initially, we performed a univariate analysis that considered age, sex, race, body mass index, current alcohol abuse, current smoking status, recent weight loss, dyspnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CPT code, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, esophageal varices, disseminated cancer, steroid use, bleeding disorder, dialysis, chemotherapy within previous 30 days, radiation therapy within previous 90 days, operation within previous 30 days, American Society of Anesthesiologists class, operative time, resident involvement, and patient functional status. We also included mean preoperative sodium, blood urea nitrogen, and albumin levels; white blood cell count; hematocrit; platelet count; and international normalized ratio. The analysis revealed unadjusted differences between patients with and without complications (t test was used for continuous variables, χ2 test for categorical variables). Any variable with P < .2 in the univariate analysis and more than 80% complete data was considered fit for our multivariate model. We controlled for confounders by performing a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Three separate analyses were performed; the outcome variables were major morbidity or mortality, minor morbidity, and any complication. P < .05 was used for statistical significance across all models. We used SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute) for statistical analysis. Model quality was evaluated for calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow test) and discrimination (C statistics). The calibration test yielded a modified χ2 statistic, and P > .05 indicated the model was appropriate and fit the data well. Good discrimination is commonly reported to be between 0.65 and 0.85.

Results

Of the 1325 patients who underwent hip arthroscopy, 60% were female. Regarding age, 52% were younger than 40 years, and 45% were between 45 years and 60 years. The most common diagnoses were articular cartilage disorder involving the pelvic region (15%), enthesopathy of the hip (12%), and joint pain involving the pelvic region or thigh (11%). The most common primary CPT code (50%) was for hip arthroscopic débridement (29862), followed by 24% for arthroscopic labral repair (29916), 16% for arthroscopic femoroplasty (29914), and 9% for arthroscopic acetabuloplasty (29915). Of the 16 complications found, 12 involved hip arthroscopic débridement, and 4 involved hip arthroscopic femoroplasty. There were no complications of arthroscopic acetabuloplasty (29915), arthroscopic labral repair (29916), or hip arthroscopy (29861).

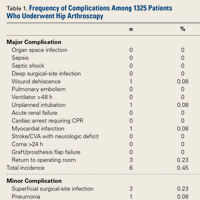

Of the 1325 hip arthroscopy patients, 16 (1.21%) had at least 1 complication (Table 1).

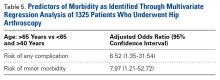

Univariate analysis identified age (P = .014), CPT code (P = .036), hypertension (P = .128), and steroid use (P = .188) as risk factors for any complication (Table 2).

Discussion

Earlier reports on hip arthroscopy did not consider risk factors for systemic morbidity and were mainly single-institution case series.3,10,11,13,25 Given a renewed focus on outcomes measurement and quality assessment in orthopedic surgery, we wanted to describe short-term complications of and risk factors for morbidity in hip arthroscopy. In this article, we report baseline data from a large multicenter cohort. For hip arthroscopy, we found low rates of short-term complications (1.21%) and major morbidities (0.45%). We considered many modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for complications and found age over 65 years to be an independent risk factor for any complication and minor morbidity. Several of our findings merit further discussion.

Other authors have reported hip arthroscopy complication rates of 1% to 20%, citing both systemic and local complications,6,8,10-12 and major complication rates of 0.3% to 0.58%.8,12 Minor complications of hip arthroscopy vary, and depend on definition, with long-term consequences unknown in some cases.8 Sensory neuropraxia, a relatively common minor complication in hip arthroscopy, is thought to be affected by the amount of traction against a perineal post and by increased operative time, with operative time under 2 hours previously suggested.3,6,10,11,13,25,26

In the present study, the overall rate of any complication of hip arthroscopy was 1.21%, and the most common complications were bleeding resulting in transfusion, return to operating room, superficial surgical-site infection, and DVT/thrombophlebitis. When we excluded bleeding resulting in transfusion, the overall complication rate fell to 0.75%. Operative time was relatively short, <2 hours for 70% of patients. Last, there were no mortalities. As our data set did not include variables encompassing sensory neuropraxia or iatrogenic chondrolabral injury, we were unable to report on these data.

Surgeons and healthcare systems should be advised that rates of systemic complications in hip arthroscopy are low and that hip arthroscopy is a relatively safe procedure. Surgeons and healthcare systems can refer to our reported complication rates and risk factors when assessing quality and performing cost analysis in hip arthroscopy. For our 1325 patients, the major morbidity rate was 0.45%, within the range of previous reports.8,12 There were no nerve injuries in our patient cohort, likely because of the strict NSQIP definitions of nerve injury. We cannot report on sensory neuropraxia and iatrogenic chondrolabral injury. We speculate that lack of these variables may have artificially lowered our minor complication rate.

Some authors have reported clinical benefits of hip arthroscopy in older patients,27-29 whereas others have suggested age may be a negative prognostic factor.27,30 Suggested indications for hip arthroscopy in an elderly population include chondral defects, labral tears, and FAI in the absence of significant arthritic changes.28,29 Larson and colleagues,30 who reported a 52% failure rate for osteoarthritis patients who underwent hip arthroscopy for FAI, concluded that arthroscopy should not be offered to patients with evidence of advanced radiographic joint space narrowing. Others have noted that patients who were under age 55 years and had minimal osteoarthritic changes had a longer interval between hip arthroscopy and total hip arthroplasty in comparison with patients over age 55 years.31 Previous work in knee arthroscopy found older age (40-65 years vs <40 years) was an independent predictor of short-term complications (1.5 times increased risk).21 In the present study, 7.69% of patients who were over age 65 years when they underwent hip arthroscopy had a complication, and we report age over 65 years as an independent risk factor for any complication (OR, 6.52) and minor morbidity (OR, 7.97). Surgeons should be aware that advanced age is an independent risk factor for complications in hip arthroscopy. Potential benefits of hip arthroscopy should be carefully weighed against the increased risk in this patient cohort, and surgeons should ascertain the scope of an elderly patient’s disease to determine if hip arthroscopy is indicated and worth the potential risks.

To our knowledge, bleeding resulting in transfusion was not previously described as a complication of hip arthroscopy. In the present study, bleeding resulting in transfusion was the most common complication (6 patients, 0.45%), and all the affected patients had a primary CPT code for arthroscopic débridement (29862). The 6 primary diagnoses were hip osteoarthrosis (3), thigh/pelvis pain (1), unspecified injury (1), and congenital hip deformity (1). The 6 transfusion patients also tended to be older (ages 30, 53, 64, 67, 76, and 90 years). Although drawing firm conclusions from so few patients would be inappropriate, we acknowledge that the majority who received a transfusion were older, underwent arthroscopic débridement of a hip, and had a primary diagnosis of osteoarthrosis or pain. As transfusion practices can differ between surgeons and groups, we conclude that the risk for bleeding requiring transfusion is low in hip arthroscopy. Patients who are older and who undergo arthroscopic débridement of an osteoarthritic hip may be at elevated risk for transfusion.

This study had several limitations. First, with use of the NSQIP database, follow-up was limited to 30 days. We speculate that longer follow-up might yield higher complication rates and additional risk factors. Second, we could not distinguish individual surgeon or site data and acknowledge complications might differ between surgeons and sites that perform hip arthroscopy more frequently. Third, as data were limited to medical and broadly applicable surgical variables included in the NSQIP database, they might not be specific to hip arthroscopy, and we cannot report on iatrogenic chondrolabral injury and neuropraxia, 2 previously reported minor complications in hip arthroscopy. We speculate that data collection focused on problems specific to hip arthroscopy would yield more complications and risk factors.

Conclusion

According to the NSQIP data, the rate of short-term morbidity after elective hip arthroscopy was low, 1.21%. Surgeons may use our reported complications and risk factors when counseling patients, and healthcare systems may use our data when assessing quality and performance in hip arthroscopy. Surgeons who perform elective hip arthroscopy should be aware that age over 65 years is an independent predictor of complications. Careful attention should be given to this patient group when indicating hip arthroscopy procedures.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E1-E9. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy utilizing the supine position. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(3):275-280.

2. Byrd JW, Jones KS. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 10-year followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(3):741-746.

3. Griffin DR, Villar RN. Complications of arthroscopy of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(4):604-606.

4. de Sa D, Alradwan H, Cargnelli S, et al. Extra-articular hip impingement: a systematic review examining operative treatment of psoas, subspine, ischiofemoral, and greater trochanteric/pelvic impingement. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(8):1026-1041.

5. de Sa D, Phillips M, Philippon MJ, Letkemann S, Simunovic N, Ayeni OR. Ligamentum teres injuries of the hip: a systematic review examining surgical indications, treatment options, and outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(12):1634-1641.

6. Oak N, Mendez-Zfass M, Lesniak BP, Larson CM, Kelly BT, Bedi A. Complications in hip arthroscopy. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2013;21(2):97-105.

7. Botser IB, Smith TW Jr, Nasser R, Domb BG. Open surgical dislocation versus arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement: a comparison of clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(2):270-278.

8. Kowalczuk M, Bhandari M, Farrokhyar F, et al. Complications following hip arthroscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(7):1669-1675.

9. Shearer DW, Kramer J, Bozic KJ, Feeley BT. Is hip arthroscopy cost-effective for femoroacetabular impingement? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(4):1079-1089.

10. Clarke MT, Arora A, Villar RN. Hip arthroscopy: complications in 1054 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(406):84-88.

11. Pailhé R, Chiron P, Reina N, Cavaignac E, Lafontan V, Laffosse JM. Pudendal nerve neuralgia after hip arthroscopy: retrospective study and literature review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(7):785-790.

12. Harris JD, McCormick FM, Abrams GD, et al. Complications and reoperations during and after hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of 92 studies and more than 6,000 patients. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):589-595.

13. Sampson TG. Complications of hip arthroscopy. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20(4):831-835.

14. Konan S, Rhee SJ, Haddad FS. Hip arthroscopy: analysis of a single surgeon’s learning experience. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(suppl 2):52-56.

15. Souza BG, Dani WS, Honda EK, et al. Do complications in hip arthroscopy change with experience? Arthroscopy. 2010;26(8):1053-1057.

16. Anthony CA, Westermann RW, Gao Y, Pugely AJ, Wolf BR, Hettrich CM. What are risk factors for 30-day morbidity and transfusion in total shoulder arthroplasty? A review of 1922 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2099-2105.

17. Daley J, Khuri SF, Henderson W, et al. Risk adjustment of the postoperative morbidity rate for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care: results of the National Veterans Affairs Surgical Risk Study. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185(4):328-340.

18. Fink AS, Campbell DA, Mentzer RM, et al. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in non-Veterans Administration hospitals: initial demonstration of feasibility. Ann Surg. 2002;236(3):344-353.

19. Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, et al. The National Veterans Administration Surgical Risk Study: risk adjustment for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180(5):519-531.

20. Martin CT, Gao Y, Pugely AJ, Wolf BR. 30-day morbidity and mortality after elective shoulder arthroscopy: a review of 9410 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1667-1675.

21. Martin CT, Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Wolf BR. Risk factors for thirty-day morbidity and mortality following knee arthroscopy: a review of 12,271 patients from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):e98.

22. Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):6-16.

23. Schoenfeld AJ, Ochoa LM, Bader JO, Belmont PJ Jr. Risk factors for immediate postoperative complications and mortality following spine surgery: a study of 3475 patients from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(17):1577-1582.

24. Yadla S, Malone J, Campbell PG, et al. Obesity and spine surgery: reassessment based on a prospective evaluation of perioperative complications in elective degenerative thoracolumbar procedures. Spine J. 2010;10(7):581-587.

25. Lo YP, Chan YS, Lien LC, Lee MS, Hsu KY, Shih CH. Complications of hip arthroscopy: analysis of seventy three cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2006;29(1):86-92.

26. Ilizaliturri VM Jr. Complications of arthroscopic femoroacetabular impingement treatment: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(3):760-768.

27. Domb BG, Linder D, Finley Z, et al. Outcomes of hip arthroscopy in patients aged 50 years or older compared with a matched-pair control of patients aged 30 years or younger. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(2):231-238.

28. Javed A, O’Donnell JM. Arthroscopic femoral osteochondroplasty for cam femoroacetabular impingement in patients over 60 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(3):326-331.

29. Philippon MJ, Schroder E Souza BG, Briggs KK. Hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in patients aged 50 years or older. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(1):59-65.

30. Larson CM, Giveans MR, Taylor M. Does arthroscopic FAI correction improve function with radiographic arthritis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(6):1667-1676.

31. Haviv B, O’Donnell J. The incidence of total hip arthroplasty after hip arthroscopy in osteoarthritic patients. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2010;2:18.

Take-Home Points

- Using the NSQIP database, the authors report that the overall complication rate was 1.21% after hip arthroscopy.

- The most common complications cited were bleeding requiring transfusion (0.45%), return to OR (0.23%), superficial infection (0.23%), and thrombophlebitis (0.15).

- Most common 10CPT code was arthroscopic débridement in 50% of cases, reflecting the types of cases being performed in the time period.

- FAI codes were less common in this database–labral repair in 24%, femoral osteochondroplasty in 16%, and acetabuloplasty in 9%.

- Use caution in patients over age 65 years as this appears to be a risk factor for morbidity.

Hip arthroscopy is a well-described method for treating a number of pathologies.1-3 Surgical indications are wide-ranging and include femoral acetabular impingement (FAI), labral tears, loose bodies, osteochondral injuries, ruptured ligamentum teres, and synovitis, as well as extra-articular injuries, including hip abductor tears and sciatic nerve entrapment.2,4-6 Authors have suggested that the advantages of hip arthroscopy over open procedures include less traumatic access to the hip joint and faster recovery,7,8 and hip arthroscopy has been found cost-effective in select groups of patients.9

Overall complications have been reported in 1% to 20% of hip arthroscopy patients,6,8,10,11 and a meta-analysis identified an overall complication rate of 4%.8 Complications include iatrogenic chondrolabral injury, nerve injury, superficial surgical-site infection, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), instrument failure, portal wound bleeding, soft-tissue injury, and intra-abdominal fluid extravasation.6,8,10-13 Rates of major complications are relatively low, 0.3% to 0.58%, according to several recent systematic reviews.8,12 Given the lack of universally accepted definitions, reports of minor complications (eg, iatrogenic chondrolabral injury, neuropraxia) in hip arthroscopy vary widely.8 Furthermore, many of the series with high complication rates represent early experience with the technique, and later authors suggested that complications should decrease with improvements in technique and technology.12,14,15The literature is lacking in reports of risk factors for patient morbidity and large multi-institutional cohorts in the setting of hip arthroscopy. We conducted a study of elective hip arthroscopy patients to determine type and incidence of complications and rates of and risk factors for minor and major morbidity.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was deemed compliant with HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) and exempt from the need for Institutional Review Board approval. In the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), academic and private medical institutions prospectively collect patient preoperative and operative data as well as 30-day outcome data from more than 500 hospitals throughout the United States.16-21 Surgical clinical reviewers, who are responsible for data acquisition, prospectively collect morbidity data for 30 days after surgery through a chart review of patient progress notes, operative notes, and follow-up clinic visits. Patients may be contacted by a surgical clinical reviewer if they have not had a clinic visit within 30 days after a procedure to verify the presence or absence of complications or admissions at outside institutions, and in this way even outpatient complications should be captured. If the medical record is unclear, the reviewer may also contact the surgeon directly. In addition, NSQIP data are routinely audited; the interobserver disagreement rate is 1.56%.22

We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) billing codes to retrospectively survey the NSQIP database for hip arthroscopies performed between 2006 and 2013. Excluding cases of compromised surgical wounds, emergent surgeries, surgeries involving fracture, hip dislocations, preoperative sepsis, septic joints, and osteomyelitis, we identified 1325 cases with CPT codes 29861 (hip arthroscopy), 29862 (arthroscopic hip débridement, shaving), 29914 (arthroscopic femoroplasty), 29915 (arthroscopic acetabuloplasty), and 29916 (arthroscopic labral repair). Postoperative outcomes were categorized as major morbidity or mortality, minor morbidity, and any complication. A major complication was a systemic life-threatening event or a substantial threat to a vital organ, whereas a minor complication did not pose a major systemic threat and was localized to the operative extremity (previously used definitions23,24). We have used similar methods to report the rates of and risk factors for complications of knee arthroscopy, shoulder arthroscopy, and total shoulder arthroplasty.16,20,21 For any-complication outcomes, we included both major and minor morbidities, and mortality. NSQIP applies strict definitions (listed in its user file17) to patient comorbidities and complications. Data points collected included patient demographics, medical comorbidities, laboratory values, and surgical characteristics.

Initially, we performed a univariate analysis that considered age, sex, race, body mass index, current alcohol abuse, current smoking status, recent weight loss, dyspnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CPT code, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, esophageal varices, disseminated cancer, steroid use, bleeding disorder, dialysis, chemotherapy within previous 30 days, radiation therapy within previous 90 days, operation within previous 30 days, American Society of Anesthesiologists class, operative time, resident involvement, and patient functional status. We also included mean preoperative sodium, blood urea nitrogen, and albumin levels; white blood cell count; hematocrit; platelet count; and international normalized ratio. The analysis revealed unadjusted differences between patients with and without complications (t test was used for continuous variables, χ2 test for categorical variables). Any variable with P < .2 in the univariate analysis and more than 80% complete data was considered fit for our multivariate model. We controlled for confounders by performing a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Three separate analyses were performed; the outcome variables were major morbidity or mortality, minor morbidity, and any complication. P < .05 was used for statistical significance across all models. We used SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute) for statistical analysis. Model quality was evaluated for calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow test) and discrimination (C statistics). The calibration test yielded a modified χ2 statistic, and P > .05 indicated the model was appropriate and fit the data well. Good discrimination is commonly reported to be between 0.65 and 0.85.

Results

Of the 1325 patients who underwent hip arthroscopy, 60% were female. Regarding age, 52% were younger than 40 years, and 45% were between 45 years and 60 years. The most common diagnoses were articular cartilage disorder involving the pelvic region (15%), enthesopathy of the hip (12%), and joint pain involving the pelvic region or thigh (11%). The most common primary CPT code (50%) was for hip arthroscopic débridement (29862), followed by 24% for arthroscopic labral repair (29916), 16% for arthroscopic femoroplasty (29914), and 9% for arthroscopic acetabuloplasty (29915). Of the 16 complications found, 12 involved hip arthroscopic débridement, and 4 involved hip arthroscopic femoroplasty. There were no complications of arthroscopic acetabuloplasty (29915), arthroscopic labral repair (29916), or hip arthroscopy (29861).

Of the 1325 hip arthroscopy patients, 16 (1.21%) had at least 1 complication (Table 1).

Univariate analysis identified age (P = .014), CPT code (P = .036), hypertension (P = .128), and steroid use (P = .188) as risk factors for any complication (Table 2).

Discussion

Earlier reports on hip arthroscopy did not consider risk factors for systemic morbidity and were mainly single-institution case series.3,10,11,13,25 Given a renewed focus on outcomes measurement and quality assessment in orthopedic surgery, we wanted to describe short-term complications of and risk factors for morbidity in hip arthroscopy. In this article, we report baseline data from a large multicenter cohort. For hip arthroscopy, we found low rates of short-term complications (1.21%) and major morbidities (0.45%). We considered many modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for complications and found age over 65 years to be an independent risk factor for any complication and minor morbidity. Several of our findings merit further discussion.

Other authors have reported hip arthroscopy complication rates of 1% to 20%, citing both systemic and local complications,6,8,10-12 and major complication rates of 0.3% to 0.58%.8,12 Minor complications of hip arthroscopy vary, and depend on definition, with long-term consequences unknown in some cases.8 Sensory neuropraxia, a relatively common minor complication in hip arthroscopy, is thought to be affected by the amount of traction against a perineal post and by increased operative time, with operative time under 2 hours previously suggested.3,6,10,11,13,25,26

In the present study, the overall rate of any complication of hip arthroscopy was 1.21%, and the most common complications were bleeding resulting in transfusion, return to operating room, superficial surgical-site infection, and DVT/thrombophlebitis. When we excluded bleeding resulting in transfusion, the overall complication rate fell to 0.75%. Operative time was relatively short, <2 hours for 70% of patients. Last, there were no mortalities. As our data set did not include variables encompassing sensory neuropraxia or iatrogenic chondrolabral injury, we were unable to report on these data.

Surgeons and healthcare systems should be advised that rates of systemic complications in hip arthroscopy are low and that hip arthroscopy is a relatively safe procedure. Surgeons and healthcare systems can refer to our reported complication rates and risk factors when assessing quality and performing cost analysis in hip arthroscopy. For our 1325 patients, the major morbidity rate was 0.45%, within the range of previous reports.8,12 There were no nerve injuries in our patient cohort, likely because of the strict NSQIP definitions of nerve injury. We cannot report on sensory neuropraxia and iatrogenic chondrolabral injury. We speculate that lack of these variables may have artificially lowered our minor complication rate.

Some authors have reported clinical benefits of hip arthroscopy in older patients,27-29 whereas others have suggested age may be a negative prognostic factor.27,30 Suggested indications for hip arthroscopy in an elderly population include chondral defects, labral tears, and FAI in the absence of significant arthritic changes.28,29 Larson and colleagues,30 who reported a 52% failure rate for osteoarthritis patients who underwent hip arthroscopy for FAI, concluded that arthroscopy should not be offered to patients with evidence of advanced radiographic joint space narrowing. Others have noted that patients who were under age 55 years and had minimal osteoarthritic changes had a longer interval between hip arthroscopy and total hip arthroplasty in comparison with patients over age 55 years.31 Previous work in knee arthroscopy found older age (40-65 years vs <40 years) was an independent predictor of short-term complications (1.5 times increased risk).21 In the present study, 7.69% of patients who were over age 65 years when they underwent hip arthroscopy had a complication, and we report age over 65 years as an independent risk factor for any complication (OR, 6.52) and minor morbidity (OR, 7.97). Surgeons should be aware that advanced age is an independent risk factor for complications in hip arthroscopy. Potential benefits of hip arthroscopy should be carefully weighed against the increased risk in this patient cohort, and surgeons should ascertain the scope of an elderly patient’s disease to determine if hip arthroscopy is indicated and worth the potential risks.

To our knowledge, bleeding resulting in transfusion was not previously described as a complication of hip arthroscopy. In the present study, bleeding resulting in transfusion was the most common complication (6 patients, 0.45%), and all the affected patients had a primary CPT code for arthroscopic débridement (29862). The 6 primary diagnoses were hip osteoarthrosis (3), thigh/pelvis pain (1), unspecified injury (1), and congenital hip deformity (1). The 6 transfusion patients also tended to be older (ages 30, 53, 64, 67, 76, and 90 years). Although drawing firm conclusions from so few patients would be inappropriate, we acknowledge that the majority who received a transfusion were older, underwent arthroscopic débridement of a hip, and had a primary diagnosis of osteoarthrosis or pain. As transfusion practices can differ between surgeons and groups, we conclude that the risk for bleeding requiring transfusion is low in hip arthroscopy. Patients who are older and who undergo arthroscopic débridement of an osteoarthritic hip may be at elevated risk for transfusion.

This study had several limitations. First, with use of the NSQIP database, follow-up was limited to 30 days. We speculate that longer follow-up might yield higher complication rates and additional risk factors. Second, we could not distinguish individual surgeon or site data and acknowledge complications might differ between surgeons and sites that perform hip arthroscopy more frequently. Third, as data were limited to medical and broadly applicable surgical variables included in the NSQIP database, they might not be specific to hip arthroscopy, and we cannot report on iatrogenic chondrolabral injury and neuropraxia, 2 previously reported minor complications in hip arthroscopy. We speculate that data collection focused on problems specific to hip arthroscopy would yield more complications and risk factors.

Conclusion

According to the NSQIP data, the rate of short-term morbidity after elective hip arthroscopy was low, 1.21%. Surgeons may use our reported complications and risk factors when counseling patients, and healthcare systems may use our data when assessing quality and performance in hip arthroscopy. Surgeons who perform elective hip arthroscopy should be aware that age over 65 years is an independent predictor of complications. Careful attention should be given to this patient group when indicating hip arthroscopy procedures.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E1-E9. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Using the NSQIP database, the authors report that the overall complication rate was 1.21% after hip arthroscopy.

- The most common complications cited were bleeding requiring transfusion (0.45%), return to OR (0.23%), superficial infection (0.23%), and thrombophlebitis (0.15).

- Most common 10CPT code was arthroscopic débridement in 50% of cases, reflecting the types of cases being performed in the time period.

- FAI codes were less common in this database–labral repair in 24%, femoral osteochondroplasty in 16%, and acetabuloplasty in 9%.

- Use caution in patients over age 65 years as this appears to be a risk factor for morbidity.

Hip arthroscopy is a well-described method for treating a number of pathologies.1-3 Surgical indications are wide-ranging and include femoral acetabular impingement (FAI), labral tears, loose bodies, osteochondral injuries, ruptured ligamentum teres, and synovitis, as well as extra-articular injuries, including hip abductor tears and sciatic nerve entrapment.2,4-6 Authors have suggested that the advantages of hip arthroscopy over open procedures include less traumatic access to the hip joint and faster recovery,7,8 and hip arthroscopy has been found cost-effective in select groups of patients.9

Overall complications have been reported in 1% to 20% of hip arthroscopy patients,6,8,10,11 and a meta-analysis identified an overall complication rate of 4%.8 Complications include iatrogenic chondrolabral injury, nerve injury, superficial surgical-site infection, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), instrument failure, portal wound bleeding, soft-tissue injury, and intra-abdominal fluid extravasation.6,8,10-13 Rates of major complications are relatively low, 0.3% to 0.58%, according to several recent systematic reviews.8,12 Given the lack of universally accepted definitions, reports of minor complications (eg, iatrogenic chondrolabral injury, neuropraxia) in hip arthroscopy vary widely.8 Furthermore, many of the series with high complication rates represent early experience with the technique, and later authors suggested that complications should decrease with improvements in technique and technology.12,14,15The literature is lacking in reports of risk factors for patient morbidity and large multi-institutional cohorts in the setting of hip arthroscopy. We conducted a study of elective hip arthroscopy patients to determine type and incidence of complications and rates of and risk factors for minor and major morbidity.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was deemed compliant with HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) and exempt from the need for Institutional Review Board approval. In the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP), academic and private medical institutions prospectively collect patient preoperative and operative data as well as 30-day outcome data from more than 500 hospitals throughout the United States.16-21 Surgical clinical reviewers, who are responsible for data acquisition, prospectively collect morbidity data for 30 days after surgery through a chart review of patient progress notes, operative notes, and follow-up clinic visits. Patients may be contacted by a surgical clinical reviewer if they have not had a clinic visit within 30 days after a procedure to verify the presence or absence of complications or admissions at outside institutions, and in this way even outpatient complications should be captured. If the medical record is unclear, the reviewer may also contact the surgeon directly. In addition, NSQIP data are routinely audited; the interobserver disagreement rate is 1.56%.22

We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) billing codes to retrospectively survey the NSQIP database for hip arthroscopies performed between 2006 and 2013. Excluding cases of compromised surgical wounds, emergent surgeries, surgeries involving fracture, hip dislocations, preoperative sepsis, septic joints, and osteomyelitis, we identified 1325 cases with CPT codes 29861 (hip arthroscopy), 29862 (arthroscopic hip débridement, shaving), 29914 (arthroscopic femoroplasty), 29915 (arthroscopic acetabuloplasty), and 29916 (arthroscopic labral repair). Postoperative outcomes were categorized as major morbidity or mortality, minor morbidity, and any complication. A major complication was a systemic life-threatening event or a substantial threat to a vital organ, whereas a minor complication did not pose a major systemic threat and was localized to the operative extremity (previously used definitions23,24). We have used similar methods to report the rates of and risk factors for complications of knee arthroscopy, shoulder arthroscopy, and total shoulder arthroplasty.16,20,21 For any-complication outcomes, we included both major and minor morbidities, and mortality. NSQIP applies strict definitions (listed in its user file17) to patient comorbidities and complications. Data points collected included patient demographics, medical comorbidities, laboratory values, and surgical characteristics.

Initially, we performed a univariate analysis that considered age, sex, race, body mass index, current alcohol abuse, current smoking status, recent weight loss, dyspnea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CPT code, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, esophageal varices, disseminated cancer, steroid use, bleeding disorder, dialysis, chemotherapy within previous 30 days, radiation therapy within previous 90 days, operation within previous 30 days, American Society of Anesthesiologists class, operative time, resident involvement, and patient functional status. We also included mean preoperative sodium, blood urea nitrogen, and albumin levels; white blood cell count; hematocrit; platelet count; and international normalized ratio. The analysis revealed unadjusted differences between patients with and without complications (t test was used for continuous variables, χ2 test for categorical variables). Any variable with P < .2 in the univariate analysis and more than 80% complete data was considered fit for our multivariate model. We controlled for confounders by performing a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Three separate analyses were performed; the outcome variables were major morbidity or mortality, minor morbidity, and any complication. P < .05 was used for statistical significance across all models. We used SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute) for statistical analysis. Model quality was evaluated for calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow test) and discrimination (C statistics). The calibration test yielded a modified χ2 statistic, and P > .05 indicated the model was appropriate and fit the data well. Good discrimination is commonly reported to be between 0.65 and 0.85.

Results