User login

Diagnosis at a Glance: Partial Hydatidiform Molar Pregnancy

Case

A 26-year-old gravida 3, para 2-0-0-2, aborta 0 whose last menstrual period was 15 weeks 5 days, presented to the ED with complaints of mild vaginal spotting, which she first noted postcoitally the previous day. The patient denied fatigue, lightheadedness, dyspnea, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing patient with normal vital signs. The abdomen was soft and nontender, and the fundus was palpable at the level of the umbilicus. A speculum examination was unremarkable, with normal external genitalia, a closed cervical os, no adnexal masses or tenderness, and no blood in the vaginal vault. Laboratory studies were significant for a serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) of 7,442 mIU/mL (reference range for 15 weeks: 12,039-70,971 mIU/mL). The patient was Rh positive with a stable hematocrit.

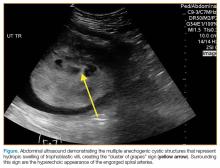

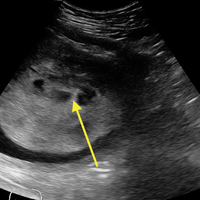

A bedside ultrasound, performed by an ultrasound-]trained emergency physician (EP), was noted to demonstrate a complex intrauterine mass comprised of several small, rounded anechoic clusters (Figure).

An obstetric consultation was made and the patient was taken to the operating room the following day for a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure. She was discharged home the next day without complications. The products of conception were sent to pathology, and confirmed a triploid karyotype and p57 trophoblastic immunopositivity, diagnostic of a partial hydatidiform mole.

Discussion

Hydatidiform moles are a subset of abnormal pregnancies termed gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). The two greatest risk factors for GTD are previous GTD and extremis of maternal age.1 Patients often present to the ED because of painless heavy vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis gravidarum, symptoms of hyperthyroidism, or preeclampsia before 20 weeks.2 Clinically, these patients present with an enlarged uterus for gestational age and very high beta-hCG levels, often greater than 100,000 mIU/mL.3 The high beta-hCG levels can lead the patient to present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as severe hypertension, given the similar chemical structures of beta-hCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone.4

After a D&C, interval beta-hCG levels need to be obtained to ensure resolution. A patient with beta-hCG levels that do not fall by 10% after 3 weeks, or are still present after 6 months, should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.5,6 Furthermore, a chest X-ray is strongly suggested, as the lungs are often the first place of metastasis.7

Partial hydatidiform moles are formed by a dispermic fertilization of a normal ovum leading to a triploid pattern, and are clinically distinguished from complete molar pregnancies because affected patients have a uterus that is often small for gestational age.8 Also, while the beta-hCG is also abnormally elevated, the median value is more modest at approximately 50,000 mIU/mL.3

According to the American College of Radiology’s Appropriateness Criteria, ultrasound is the gold standard for evaluating gestational trophoblastic disease. While the classic sonographic appearance of a molar pregnancy is described as a “snowstorm” appearance, advancement in technology more clearly demonstrates a “cluster of grapes” or “honeycomb” appearance.9 On Doppler mode, increased vascularity peripherally can also be detected due to engorgement of the spiral arteries. While partial moles tend to have more focal lesions, the greatest distinguishing factor is the presence of embryonic or fetal tissue, which is not seen in complete moles. However, due to the heterogeneous appearance of the uterus in all GTD, molar pregnancies can sometimes be misinterpreted as missed abortions or clotted blood, so that pathological confirmation is mandatory for all products of conception in the United States and Canada.2,10

Summary

This case is of particular interest because it demonstrates an atypical presentation of a partial hydatidiform mole. While most classic presentations include older patients with heavy vaginal bleeding, a smaller uterus than expected, significantly elevated beta-hCGs, and hyperemesis gravidarum, our patient was relatively young with no history of molar pregnancies in the past, a larger-than-expected uterus, and no vaginal bleeding noted. Laboratory values also indicated a significantly lower-than-expected beta-hCG level. As such, bedside ultrasound findings were unexpected but resulted in the prompt diagnosis, an emergent obstetric consultation, and confirmatory radiology imaging. The ED bedside ultrasound findings did demonstrate the characteristic “cluster of grapes” appearance surrounded by the hyperechoic appearance of the spiral arteries (Figure). An intrauterine yolk sac was also identified by ultrasound, which strongly suggested a partial rather than a complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy.

While hydatidiform pregnancies are relatively rare, EPs should be aware of the clinical and sonographic features of these diseases. This case, particularly given the atypical clinical presentation for a partial molar pregnancy, highlights the importance of ultrasound in pregnancy, and the utility of bedside ultrasound in the evaluation of the etiology of vaginal bleeding in the early pregnant patient that presents to the ED.

1. Ngan H, Bender H, Benedet JL, et al. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, FIGO 2000 staging and classification. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83 Suppl 1:175-177.

2. Tie W, Tajnert K, Plavsic SK. Ultrasound imaging of gestational trophoblastic disease. Donald School J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;7(1):105-112.

3. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current advances in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):3-5.

4. Cole LA, Butler S. Detection of hCG in trophoblastic disease: The USA hCG reference service experience. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(6):433-444.

5. Lavie I, Rao GG, Castrillon DH, Miller DS, Schorge JO. Duration of human chorionic gonadotropin surveillance for partial hydatidiform moles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1362-1364.

6. Kenny L, Seckl MJ. Treatments for gestational trophoblastic disease. Expert Rev of Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(2):215-225.

7. Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(5):775-779.

8. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Clinical practice. Molar pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1639-1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0900696.

9. Kirk E, Papageorghiou AT, Condous G, Bottomley C, Bourne T. The accuracy of first trimester ultrasound in the diagnosis of hydatidiform mole. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(1):70-75.

10. Wang Y, Zhao S. Vascular Biology of the Placenta. Chapter 4. Cell Types of the Placenta. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010.

Case

A 26-year-old gravida 3, para 2-0-0-2, aborta 0 whose last menstrual period was 15 weeks 5 days, presented to the ED with complaints of mild vaginal spotting, which she first noted postcoitally the previous day. The patient denied fatigue, lightheadedness, dyspnea, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing patient with normal vital signs. The abdomen was soft and nontender, and the fundus was palpable at the level of the umbilicus. A speculum examination was unremarkable, with normal external genitalia, a closed cervical os, no adnexal masses or tenderness, and no blood in the vaginal vault. Laboratory studies were significant for a serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) of 7,442 mIU/mL (reference range for 15 weeks: 12,039-70,971 mIU/mL). The patient was Rh positive with a stable hematocrit.

A bedside ultrasound, performed by an ultrasound-]trained emergency physician (EP), was noted to demonstrate a complex intrauterine mass comprised of several small, rounded anechoic clusters (Figure).

An obstetric consultation was made and the patient was taken to the operating room the following day for a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure. She was discharged home the next day without complications. The products of conception were sent to pathology, and confirmed a triploid karyotype and p57 trophoblastic immunopositivity, diagnostic of a partial hydatidiform mole.

Discussion

Hydatidiform moles are a subset of abnormal pregnancies termed gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). The two greatest risk factors for GTD are previous GTD and extremis of maternal age.1 Patients often present to the ED because of painless heavy vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis gravidarum, symptoms of hyperthyroidism, or preeclampsia before 20 weeks.2 Clinically, these patients present with an enlarged uterus for gestational age and very high beta-hCG levels, often greater than 100,000 mIU/mL.3 The high beta-hCG levels can lead the patient to present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as severe hypertension, given the similar chemical structures of beta-hCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone.4

After a D&C, interval beta-hCG levels need to be obtained to ensure resolution. A patient with beta-hCG levels that do not fall by 10% after 3 weeks, or are still present after 6 months, should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.5,6 Furthermore, a chest X-ray is strongly suggested, as the lungs are often the first place of metastasis.7

Partial hydatidiform moles are formed by a dispermic fertilization of a normal ovum leading to a triploid pattern, and are clinically distinguished from complete molar pregnancies because affected patients have a uterus that is often small for gestational age.8 Also, while the beta-hCG is also abnormally elevated, the median value is more modest at approximately 50,000 mIU/mL.3

According to the American College of Radiology’s Appropriateness Criteria, ultrasound is the gold standard for evaluating gestational trophoblastic disease. While the classic sonographic appearance of a molar pregnancy is described as a “snowstorm” appearance, advancement in technology more clearly demonstrates a “cluster of grapes” or “honeycomb” appearance.9 On Doppler mode, increased vascularity peripherally can also be detected due to engorgement of the spiral arteries. While partial moles tend to have more focal lesions, the greatest distinguishing factor is the presence of embryonic or fetal tissue, which is not seen in complete moles. However, due to the heterogeneous appearance of the uterus in all GTD, molar pregnancies can sometimes be misinterpreted as missed abortions or clotted blood, so that pathological confirmation is mandatory for all products of conception in the United States and Canada.2,10

Summary

This case is of particular interest because it demonstrates an atypical presentation of a partial hydatidiform mole. While most classic presentations include older patients with heavy vaginal bleeding, a smaller uterus than expected, significantly elevated beta-hCGs, and hyperemesis gravidarum, our patient was relatively young with no history of molar pregnancies in the past, a larger-than-expected uterus, and no vaginal bleeding noted. Laboratory values also indicated a significantly lower-than-expected beta-hCG level. As such, bedside ultrasound findings were unexpected but resulted in the prompt diagnosis, an emergent obstetric consultation, and confirmatory radiology imaging. The ED bedside ultrasound findings did demonstrate the characteristic “cluster of grapes” appearance surrounded by the hyperechoic appearance of the spiral arteries (Figure). An intrauterine yolk sac was also identified by ultrasound, which strongly suggested a partial rather than a complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy.

While hydatidiform pregnancies are relatively rare, EPs should be aware of the clinical and sonographic features of these diseases. This case, particularly given the atypical clinical presentation for a partial molar pregnancy, highlights the importance of ultrasound in pregnancy, and the utility of bedside ultrasound in the evaluation of the etiology of vaginal bleeding in the early pregnant patient that presents to the ED.

Case

A 26-year-old gravida 3, para 2-0-0-2, aborta 0 whose last menstrual period was 15 weeks 5 days, presented to the ED with complaints of mild vaginal spotting, which she first noted postcoitally the previous day. The patient denied fatigue, lightheadedness, dyspnea, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing patient with normal vital signs. The abdomen was soft and nontender, and the fundus was palpable at the level of the umbilicus. A speculum examination was unremarkable, with normal external genitalia, a closed cervical os, no adnexal masses or tenderness, and no blood in the vaginal vault. Laboratory studies were significant for a serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) of 7,442 mIU/mL (reference range for 15 weeks: 12,039-70,971 mIU/mL). The patient was Rh positive with a stable hematocrit.

A bedside ultrasound, performed by an ultrasound-]trained emergency physician (EP), was noted to demonstrate a complex intrauterine mass comprised of several small, rounded anechoic clusters (Figure).

An obstetric consultation was made and the patient was taken to the operating room the following day for a dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure. She was discharged home the next day without complications. The products of conception were sent to pathology, and confirmed a triploid karyotype and p57 trophoblastic immunopositivity, diagnostic of a partial hydatidiform mole.

Discussion

Hydatidiform moles are a subset of abnormal pregnancies termed gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD). The two greatest risk factors for GTD are previous GTD and extremis of maternal age.1 Patients often present to the ED because of painless heavy vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis gravidarum, symptoms of hyperthyroidism, or preeclampsia before 20 weeks.2 Clinically, these patients present with an enlarged uterus for gestational age and very high beta-hCG levels, often greater than 100,000 mIU/mL.3 The high beta-hCG levels can lead the patient to present with symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as severe hypertension, given the similar chemical structures of beta-hCG and thyroid-stimulating hormone.4

After a D&C, interval beta-hCG levels need to be obtained to ensure resolution. A patient with beta-hCG levels that do not fall by 10% after 3 weeks, or are still present after 6 months, should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.5,6 Furthermore, a chest X-ray is strongly suggested, as the lungs are often the first place of metastasis.7

Partial hydatidiform moles are formed by a dispermic fertilization of a normal ovum leading to a triploid pattern, and are clinically distinguished from complete molar pregnancies because affected patients have a uterus that is often small for gestational age.8 Also, while the beta-hCG is also abnormally elevated, the median value is more modest at approximately 50,000 mIU/mL.3

According to the American College of Radiology’s Appropriateness Criteria, ultrasound is the gold standard for evaluating gestational trophoblastic disease. While the classic sonographic appearance of a molar pregnancy is described as a “snowstorm” appearance, advancement in technology more clearly demonstrates a “cluster of grapes” or “honeycomb” appearance.9 On Doppler mode, increased vascularity peripherally can also be detected due to engorgement of the spiral arteries. While partial moles tend to have more focal lesions, the greatest distinguishing factor is the presence of embryonic or fetal tissue, which is not seen in complete moles. However, due to the heterogeneous appearance of the uterus in all GTD, molar pregnancies can sometimes be misinterpreted as missed abortions or clotted blood, so that pathological confirmation is mandatory for all products of conception in the United States and Canada.2,10

Summary

This case is of particular interest because it demonstrates an atypical presentation of a partial hydatidiform mole. While most classic presentations include older patients with heavy vaginal bleeding, a smaller uterus than expected, significantly elevated beta-hCGs, and hyperemesis gravidarum, our patient was relatively young with no history of molar pregnancies in the past, a larger-than-expected uterus, and no vaginal bleeding noted. Laboratory values also indicated a significantly lower-than-expected beta-hCG level. As such, bedside ultrasound findings were unexpected but resulted in the prompt diagnosis, an emergent obstetric consultation, and confirmatory radiology imaging. The ED bedside ultrasound findings did demonstrate the characteristic “cluster of grapes” appearance surrounded by the hyperechoic appearance of the spiral arteries (Figure). An intrauterine yolk sac was also identified by ultrasound, which strongly suggested a partial rather than a complete hydatidiform molar pregnancy.

While hydatidiform pregnancies are relatively rare, EPs should be aware of the clinical and sonographic features of these diseases. This case, particularly given the atypical clinical presentation for a partial molar pregnancy, highlights the importance of ultrasound in pregnancy, and the utility of bedside ultrasound in the evaluation of the etiology of vaginal bleeding in the early pregnant patient that presents to the ED.

1. Ngan H, Bender H, Benedet JL, et al. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, FIGO 2000 staging and classification. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83 Suppl 1:175-177.

2. Tie W, Tajnert K, Plavsic SK. Ultrasound imaging of gestational trophoblastic disease. Donald School J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;7(1):105-112.

3. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current advances in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):3-5.

4. Cole LA, Butler S. Detection of hCG in trophoblastic disease: The USA hCG reference service experience. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(6):433-444.

5. Lavie I, Rao GG, Castrillon DH, Miller DS, Schorge JO. Duration of human chorionic gonadotropin surveillance for partial hydatidiform moles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1362-1364.

6. Kenny L, Seckl MJ. Treatments for gestational trophoblastic disease. Expert Rev of Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(2):215-225.

7. Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(5):775-779.

8. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Clinical practice. Molar pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1639-1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0900696.

9. Kirk E, Papageorghiou AT, Condous G, Bottomley C, Bourne T. The accuracy of first trimester ultrasound in the diagnosis of hydatidiform mole. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(1):70-75.

10. Wang Y, Zhao S. Vascular Biology of the Placenta. Chapter 4. Cell Types of the Placenta. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010.

1. Ngan H, Bender H, Benedet JL, et al. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia, FIGO 2000 staging and classification. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83 Suppl 1:175-177.

2. Tie W, Tajnert K, Plavsic SK. Ultrasound imaging of gestational trophoblastic disease. Donald School J Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;7(1):105-112.

3. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Current advances in the management of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(1):3-5.

4. Cole LA, Butler S. Detection of hCG in trophoblastic disease: The USA hCG reference service experience. J Reprod Med. 2002;47(6):433-444.

5. Lavie I, Rao GG, Castrillon DH, Miller DS, Schorge JO. Duration of human chorionic gonadotropin surveillance for partial hydatidiform moles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1362-1364.

6. Kenny L, Seckl MJ. Treatments for gestational trophoblastic disease. Expert Rev of Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(2):215-225.

7. Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86(5):775-779.

8. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP. Clinical practice. Molar pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1639-1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0900696.

9. Kirk E, Papageorghiou AT, Condous G, Bottomley C, Bourne T. The accuracy of first trimester ultrasound in the diagnosis of hydatidiform mole. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(1):70-75.

10. Wang Y, Zhao S. Vascular Biology of the Placenta. Chapter 4. Cell Types of the Placenta. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010.

Cardiofaciocutaneous Syndrome and the Dermatologist’s Contribution to Diagnosis

To the Editor:

RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Each syndrome exhibits its phenotypic features; however, because all of them cause dysregulation of the RAS/MAPK pathway, there are numerous overlapping phenotypic features between the syndromes including cardiac defects, cutaneous abnormalities, characteristic facial features, neurocognitive impairment, and increased risk for developing some neoplastic disorders.

Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy and is a genetic sporadic disease characterized by multiple congenital anomalies associated with mental retardation. It has a complex dermatological phenotype with many cutaneous features that can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes, which also are classified as RASopathies.

A 3-year-old girl presented with skin xerosis and follicular hyperkeratosis of the face, neck, trunk, and limbs (Figure 1). Facial follicular hyperkeratotic papules on an erythematous base were associated with alopecia of the eyebrows (ulerythema ophryogenes). Hair was sparse and curly (Figure 2A). Facial dysmorphic features included a prominent forehead with bitemporal constriction, bilateral ptosis, a broad nasal base, lip contour in a Cupid’s bow, low-set earlobes with creases (Figure 2B), and a short and webbed neck.

Congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, bilateral hydronephrosis, delayed motor development, and seizures were noted for the first 2 years. Brain computed tomography detected a dilated ventricular system with hydrocephalus. There was no family history of consanguinity.

Pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and preeclampsia. The neonate was delivered at full-term and was readmitted at 6 days of age due to respiratory failure secondary to congenital chylothorax. Cardiac malformation was diagnosed as the ostium secundum atrial septal defect and interventricular and atrioventricular septal defects. Up to this point she was being treated for Turner syndrome.

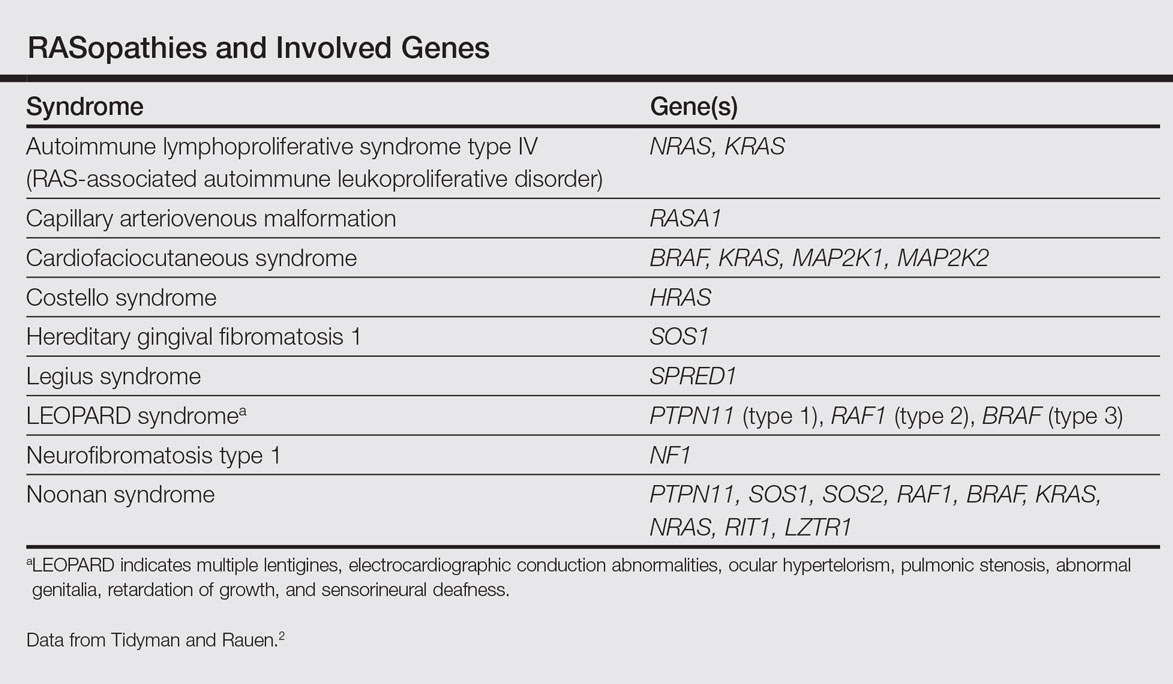

The RASopathies are a class of human genetic syndromes that are caused by germ line mutations in genes that encode components of the RAS/MAPK pathway.1 There are many syndromes classified as RASopathies (Table).2,3

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 115150) is a genetic disorder first described by Reynolds et al4 and is characterized by several cutaneous abnormalities, cardiac defects, dysmorphic craniofacial features, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and mental retardation. It occurs sporadically and is caused by functional activation of mutations in 4 different genes—BRAF, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2—of the RAS extracellular signal–regulated kinase molecular cascade that regulates cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.1

As a RASopathy, CFC syndrome is a member of a family of syndromes with similar phenotypes, which includes mainly Noonan and Costello syndromes. Psychomotor retardation and physical anomalies, the common denominator of all syndromes, may be explained by the effects of the mutations during early development.5,6

In CFC, relative macrocephaly, prominent forehead, bitemporal constriction, absence of eyebrows, palpebral ptosis, broad nasal root, bulbous nasal tip, and small chin commonly are found. The eyes are widely spaced and the palpebral fissures are downward slanting with epicanthic folds.1,4,7

Follicular keratosis of the arms, legs, and face occurs in 80% of cases of CFC and ulerythema ophryogenes with sparse eyebrows in 90% of cases. Sparse, curly, and slow-growing hair is found in 93% of patients. Xerotic scaly skin, hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, infantile hemangiomas, and multiple melanocytic nevi also may occur.8

Cardiac abnormalities are seen in 75.7% of patients.1 Other features include mental retardation, delayed motor development, and structural abnormalities in the central nervous system, as well as seizures and electroencephalogram abnormalities. Unlike Noonan and Costello syndromes, it is unclear if patients with CFC syndrome are at an increased risk for cancer.1

Noonan syndrome (OMIM #163950) is a disorder characterized by congenital heart defects, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, distinctive facial dysmorphic features, and variable cognitive deficits. Other associated features include cryptorchidism, lymphatic dysplasia, bleeding tendency, and occasional hematologic malignancies during childhood. This syndrome is related to mutations in the PTPN11, SOS1, SOS2, RAF1, BRAF, KRAS, NRAS, RIT1, and LZTR1 genes.2,9-11 The typical ear shape and placement in Noonan syndrome is oval with an overfolded helix that is low set and posteriorly angulated, which is uncommon in CFC syndrome. Noonan syndrome is characterized by an inverted triangular face; hypertelorism; blue or blue-green iris color; webbed neck; limited skin involvement, mainly represented by multiple nevi; and a much milder developmental delay compared to CFC and Costello syndromes.1,11

Costello syndrome (OMIM #218040) is a rare condition comprised of severe postnatal feeding difficulties, mental retardation, coarse facial features, cardiovascular abnormalities (eg, pulmonic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial tachycardia), tumor predisposition, and skin and musculoskeletal abnormalities.12 Costello syndrome is clinically diagnosed. This syndrome shows coarse facies with macrocephaly, downward-slanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, bulbous nose with anteversed nostrils and low nasal bridge, full cheeks, large mouth, thick lips, large tongue, nasal papillomas, cutis laxa, low-set ears, short neck, diffuse skin hyperpigmentation, ulnar deviation of the hands, and nail dystrophy that are not observed in CFC. It is now accepted that the term Costello syndrome should be reserved for patients with HRAS mutation because of the specific risk profile of these patients.12 Remarkably, patients with Costello syndrome are at increased tumor risk (eg, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, bladder carcinoma).2,12

The diagnosis of CFC syndrome is purely clinical. There have been many attempts to delineate the syndrome, but none of the described traits are pathognomonic. In 2002, Kavamura et al7 created the CFC index, a useful diagnostic approach based on 82 clinical characteristics and their frequencies in the CFC population.

Skin abnormalities are helpful manifestations to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes. Patients with CFC syndrome present with follicular hyperkeratosis and absent eyebrows. Absent eyebrows, narrowed temples, and Cupid’s bow lip are hallmark features of CFC syndrome and are absent in Noonan and Costello syndromes. The presentation of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis also is a differentiating feature; in patients with Costello syndrome, it is found outside the pressure zones, whereas in those with CFC syndrome, it is present mainly in the pressure zones.1 Dermatologists can assist geneticists in the differential diagnosis of these syndromes.

The treatment of disorders with follicular plugging and xerosis is challenging. Emollients with urea, glycolic acid, and lactic acid could improve the appearance of the skin. Treatment with mutated MEK gene inhibitors is under investigation to restore normal development of affected embryos with CFC.2,13 This case and theoretical data show that skin manifestations can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from other RASopathies such as Noonan and Costello syndromes.

- Roberts A, Allanson J, Jadico SK, et al. The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:833-842.

- Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. The RASopathies: developmental syndromes of Ras/MAPK pathway dysregulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:230-236.

- Stevenson D, Viskochil D, Mao R, et al. Legius syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47312.

- Reynolds JF, Neri G, Herrmann JP, et al. New multiple congenital anomalies/mental retardation syndrome with cardio-facio-cutaneous involvement—the CFC syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:413-427.

- Zenker M, Lehmann K, Schulz AL, et al. Expansion of the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum in patients with KRAS germline mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44:131-135.

- Rodriguez-Viciana P, Tetsu O, Tidyman WE, et al. Germline mutations in genes within the MAPK pathway cause cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Science. 2006;311:1287-1290.

- Kavamura MI, Peres CA, Alchorne MM, et al. CFC index for the diagnosis of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:12-16.

- Siegel DH, McKenzie J, Frieden IJ, et al. Dermatological findings in 61 mutation-positive individuals with cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:521-529.

- Tartaglia M, Zampino G, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1:2-26.

- Lo FS, Lin JL, Kuo MT, et al. Noonan syndrome caused by germline KRAS mutation in Taiwan: report of two patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:919-923.

- Allanson JE, Roberts AE. Noonan syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1124/.

- Gripp KW, Lin AE. Costello syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1507/.

- Inoue S, Moriya M, Watanabe Y, et al. New BRAF knockin mice provide a pathogenetic mechanism of developmental defects and a therapeutic approach in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6553-6566.

To the Editor:

RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Each syndrome exhibits its phenotypic features; however, because all of them cause dysregulation of the RAS/MAPK pathway, there are numerous overlapping phenotypic features between the syndromes including cardiac defects, cutaneous abnormalities, characteristic facial features, neurocognitive impairment, and increased risk for developing some neoplastic disorders.

Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy and is a genetic sporadic disease characterized by multiple congenital anomalies associated with mental retardation. It has a complex dermatological phenotype with many cutaneous features that can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes, which also are classified as RASopathies.

A 3-year-old girl presented with skin xerosis and follicular hyperkeratosis of the face, neck, trunk, and limbs (Figure 1). Facial follicular hyperkeratotic papules on an erythematous base were associated with alopecia of the eyebrows (ulerythema ophryogenes). Hair was sparse and curly (Figure 2A). Facial dysmorphic features included a prominent forehead with bitemporal constriction, bilateral ptosis, a broad nasal base, lip contour in a Cupid’s bow, low-set earlobes with creases (Figure 2B), and a short and webbed neck.

Congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, bilateral hydronephrosis, delayed motor development, and seizures were noted for the first 2 years. Brain computed tomography detected a dilated ventricular system with hydrocephalus. There was no family history of consanguinity.

Pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and preeclampsia. The neonate was delivered at full-term and was readmitted at 6 days of age due to respiratory failure secondary to congenital chylothorax. Cardiac malformation was diagnosed as the ostium secundum atrial septal defect and interventricular and atrioventricular septal defects. Up to this point she was being treated for Turner syndrome.

The RASopathies are a class of human genetic syndromes that are caused by germ line mutations in genes that encode components of the RAS/MAPK pathway.1 There are many syndromes classified as RASopathies (Table).2,3

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 115150) is a genetic disorder first described by Reynolds et al4 and is characterized by several cutaneous abnormalities, cardiac defects, dysmorphic craniofacial features, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and mental retardation. It occurs sporadically and is caused by functional activation of mutations in 4 different genes—BRAF, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2—of the RAS extracellular signal–regulated kinase molecular cascade that regulates cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.1

As a RASopathy, CFC syndrome is a member of a family of syndromes with similar phenotypes, which includes mainly Noonan and Costello syndromes. Psychomotor retardation and physical anomalies, the common denominator of all syndromes, may be explained by the effects of the mutations during early development.5,6

In CFC, relative macrocephaly, prominent forehead, bitemporal constriction, absence of eyebrows, palpebral ptosis, broad nasal root, bulbous nasal tip, and small chin commonly are found. The eyes are widely spaced and the palpebral fissures are downward slanting with epicanthic folds.1,4,7

Follicular keratosis of the arms, legs, and face occurs in 80% of cases of CFC and ulerythema ophryogenes with sparse eyebrows in 90% of cases. Sparse, curly, and slow-growing hair is found in 93% of patients. Xerotic scaly skin, hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, infantile hemangiomas, and multiple melanocytic nevi also may occur.8

Cardiac abnormalities are seen in 75.7% of patients.1 Other features include mental retardation, delayed motor development, and structural abnormalities in the central nervous system, as well as seizures and electroencephalogram abnormalities. Unlike Noonan and Costello syndromes, it is unclear if patients with CFC syndrome are at an increased risk for cancer.1

Noonan syndrome (OMIM #163950) is a disorder characterized by congenital heart defects, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, distinctive facial dysmorphic features, and variable cognitive deficits. Other associated features include cryptorchidism, lymphatic dysplasia, bleeding tendency, and occasional hematologic malignancies during childhood. This syndrome is related to mutations in the PTPN11, SOS1, SOS2, RAF1, BRAF, KRAS, NRAS, RIT1, and LZTR1 genes.2,9-11 The typical ear shape and placement in Noonan syndrome is oval with an overfolded helix that is low set and posteriorly angulated, which is uncommon in CFC syndrome. Noonan syndrome is characterized by an inverted triangular face; hypertelorism; blue or blue-green iris color; webbed neck; limited skin involvement, mainly represented by multiple nevi; and a much milder developmental delay compared to CFC and Costello syndromes.1,11

Costello syndrome (OMIM #218040) is a rare condition comprised of severe postnatal feeding difficulties, mental retardation, coarse facial features, cardiovascular abnormalities (eg, pulmonic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial tachycardia), tumor predisposition, and skin and musculoskeletal abnormalities.12 Costello syndrome is clinically diagnosed. This syndrome shows coarse facies with macrocephaly, downward-slanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, bulbous nose with anteversed nostrils and low nasal bridge, full cheeks, large mouth, thick lips, large tongue, nasal papillomas, cutis laxa, low-set ears, short neck, diffuse skin hyperpigmentation, ulnar deviation of the hands, and nail dystrophy that are not observed in CFC. It is now accepted that the term Costello syndrome should be reserved for patients with HRAS mutation because of the specific risk profile of these patients.12 Remarkably, patients with Costello syndrome are at increased tumor risk (eg, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, bladder carcinoma).2,12

The diagnosis of CFC syndrome is purely clinical. There have been many attempts to delineate the syndrome, but none of the described traits are pathognomonic. In 2002, Kavamura et al7 created the CFC index, a useful diagnostic approach based on 82 clinical characteristics and their frequencies in the CFC population.

Skin abnormalities are helpful manifestations to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes. Patients with CFC syndrome present with follicular hyperkeratosis and absent eyebrows. Absent eyebrows, narrowed temples, and Cupid’s bow lip are hallmark features of CFC syndrome and are absent in Noonan and Costello syndromes. The presentation of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis also is a differentiating feature; in patients with Costello syndrome, it is found outside the pressure zones, whereas in those with CFC syndrome, it is present mainly in the pressure zones.1 Dermatologists can assist geneticists in the differential diagnosis of these syndromes.

The treatment of disorders with follicular plugging and xerosis is challenging. Emollients with urea, glycolic acid, and lactic acid could improve the appearance of the skin. Treatment with mutated MEK gene inhibitors is under investigation to restore normal development of affected embryos with CFC.2,13 This case and theoretical data show that skin manifestations can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from other RASopathies such as Noonan and Costello syndromes.

To the Editor:

RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Each syndrome exhibits its phenotypic features; however, because all of them cause dysregulation of the RAS/MAPK pathway, there are numerous overlapping phenotypic features between the syndromes including cardiac defects, cutaneous abnormalities, characteristic facial features, neurocognitive impairment, and increased risk for developing some neoplastic disorders.

Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy and is a genetic sporadic disease characterized by multiple congenital anomalies associated with mental retardation. It has a complex dermatological phenotype with many cutaneous features that can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes, which also are classified as RASopathies.

A 3-year-old girl presented with skin xerosis and follicular hyperkeratosis of the face, neck, trunk, and limbs (Figure 1). Facial follicular hyperkeratotic papules on an erythematous base were associated with alopecia of the eyebrows (ulerythema ophryogenes). Hair was sparse and curly (Figure 2A). Facial dysmorphic features included a prominent forehead with bitemporal constriction, bilateral ptosis, a broad nasal base, lip contour in a Cupid’s bow, low-set earlobes with creases (Figure 2B), and a short and webbed neck.

Congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, bilateral hydronephrosis, delayed motor development, and seizures were noted for the first 2 years. Brain computed tomography detected a dilated ventricular system with hydrocephalus. There was no family history of consanguinity.

Pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and preeclampsia. The neonate was delivered at full-term and was readmitted at 6 days of age due to respiratory failure secondary to congenital chylothorax. Cardiac malformation was diagnosed as the ostium secundum atrial septal defect and interventricular and atrioventricular septal defects. Up to this point she was being treated for Turner syndrome.

The RASopathies are a class of human genetic syndromes that are caused by germ line mutations in genes that encode components of the RAS/MAPK pathway.1 There are many syndromes classified as RASopathies (Table).2,3

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 115150) is a genetic disorder first described by Reynolds et al4 and is characterized by several cutaneous abnormalities, cardiac defects, dysmorphic craniofacial features, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and mental retardation. It occurs sporadically and is caused by functional activation of mutations in 4 different genes—BRAF, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2—of the RAS extracellular signal–regulated kinase molecular cascade that regulates cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.1

As a RASopathy, CFC syndrome is a member of a family of syndromes with similar phenotypes, which includes mainly Noonan and Costello syndromes. Psychomotor retardation and physical anomalies, the common denominator of all syndromes, may be explained by the effects of the mutations during early development.5,6

In CFC, relative macrocephaly, prominent forehead, bitemporal constriction, absence of eyebrows, palpebral ptosis, broad nasal root, bulbous nasal tip, and small chin commonly are found. The eyes are widely spaced and the palpebral fissures are downward slanting with epicanthic folds.1,4,7

Follicular keratosis of the arms, legs, and face occurs in 80% of cases of CFC and ulerythema ophryogenes with sparse eyebrows in 90% of cases. Sparse, curly, and slow-growing hair is found in 93% of patients. Xerotic scaly skin, hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, infantile hemangiomas, and multiple melanocytic nevi also may occur.8

Cardiac abnormalities are seen in 75.7% of patients.1 Other features include mental retardation, delayed motor development, and structural abnormalities in the central nervous system, as well as seizures and electroencephalogram abnormalities. Unlike Noonan and Costello syndromes, it is unclear if patients with CFC syndrome are at an increased risk for cancer.1

Noonan syndrome (OMIM #163950) is a disorder characterized by congenital heart defects, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, distinctive facial dysmorphic features, and variable cognitive deficits. Other associated features include cryptorchidism, lymphatic dysplasia, bleeding tendency, and occasional hematologic malignancies during childhood. This syndrome is related to mutations in the PTPN11, SOS1, SOS2, RAF1, BRAF, KRAS, NRAS, RIT1, and LZTR1 genes.2,9-11 The typical ear shape and placement in Noonan syndrome is oval with an overfolded helix that is low set and posteriorly angulated, which is uncommon in CFC syndrome. Noonan syndrome is characterized by an inverted triangular face; hypertelorism; blue or blue-green iris color; webbed neck; limited skin involvement, mainly represented by multiple nevi; and a much milder developmental delay compared to CFC and Costello syndromes.1,11

Costello syndrome (OMIM #218040) is a rare condition comprised of severe postnatal feeding difficulties, mental retardation, coarse facial features, cardiovascular abnormalities (eg, pulmonic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial tachycardia), tumor predisposition, and skin and musculoskeletal abnormalities.12 Costello syndrome is clinically diagnosed. This syndrome shows coarse facies with macrocephaly, downward-slanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, bulbous nose with anteversed nostrils and low nasal bridge, full cheeks, large mouth, thick lips, large tongue, nasal papillomas, cutis laxa, low-set ears, short neck, diffuse skin hyperpigmentation, ulnar deviation of the hands, and nail dystrophy that are not observed in CFC. It is now accepted that the term Costello syndrome should be reserved for patients with HRAS mutation because of the specific risk profile of these patients.12 Remarkably, patients with Costello syndrome are at increased tumor risk (eg, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, bladder carcinoma).2,12

The diagnosis of CFC syndrome is purely clinical. There have been many attempts to delineate the syndrome, but none of the described traits are pathognomonic. In 2002, Kavamura et al7 created the CFC index, a useful diagnostic approach based on 82 clinical characteristics and their frequencies in the CFC population.

Skin abnormalities are helpful manifestations to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes. Patients with CFC syndrome present with follicular hyperkeratosis and absent eyebrows. Absent eyebrows, narrowed temples, and Cupid’s bow lip are hallmark features of CFC syndrome and are absent in Noonan and Costello syndromes. The presentation of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis also is a differentiating feature; in patients with Costello syndrome, it is found outside the pressure zones, whereas in those with CFC syndrome, it is present mainly in the pressure zones.1 Dermatologists can assist geneticists in the differential diagnosis of these syndromes.

The treatment of disorders with follicular plugging and xerosis is challenging. Emollients with urea, glycolic acid, and lactic acid could improve the appearance of the skin. Treatment with mutated MEK gene inhibitors is under investigation to restore normal development of affected embryos with CFC.2,13 This case and theoretical data show that skin manifestations can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from other RASopathies such as Noonan and Costello syndromes.

- Roberts A, Allanson J, Jadico SK, et al. The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:833-842.

- Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. The RASopathies: developmental syndromes of Ras/MAPK pathway dysregulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:230-236.

- Stevenson D, Viskochil D, Mao R, et al. Legius syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47312.

- Reynolds JF, Neri G, Herrmann JP, et al. New multiple congenital anomalies/mental retardation syndrome with cardio-facio-cutaneous involvement—the CFC syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:413-427.

- Zenker M, Lehmann K, Schulz AL, et al. Expansion of the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum in patients with KRAS germline mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44:131-135.

- Rodriguez-Viciana P, Tetsu O, Tidyman WE, et al. Germline mutations in genes within the MAPK pathway cause cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Science. 2006;311:1287-1290.

- Kavamura MI, Peres CA, Alchorne MM, et al. CFC index for the diagnosis of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:12-16.

- Siegel DH, McKenzie J, Frieden IJ, et al. Dermatological findings in 61 mutation-positive individuals with cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:521-529.

- Tartaglia M, Zampino G, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1:2-26.

- Lo FS, Lin JL, Kuo MT, et al. Noonan syndrome caused by germline KRAS mutation in Taiwan: report of two patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:919-923.

- Allanson JE, Roberts AE. Noonan syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1124/.

- Gripp KW, Lin AE. Costello syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1507/.

- Inoue S, Moriya M, Watanabe Y, et al. New BRAF knockin mice provide a pathogenetic mechanism of developmental defects and a therapeutic approach in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6553-6566.

- Roberts A, Allanson J, Jadico SK, et al. The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:833-842.

- Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. The RASopathies: developmental syndromes of Ras/MAPK pathway dysregulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:230-236.

- Stevenson D, Viskochil D, Mao R, et al. Legius syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47312.

- Reynolds JF, Neri G, Herrmann JP, et al. New multiple congenital anomalies/mental retardation syndrome with cardio-facio-cutaneous involvement—the CFC syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:413-427.

- Zenker M, Lehmann K, Schulz AL, et al. Expansion of the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum in patients with KRAS germline mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44:131-135.

- Rodriguez-Viciana P, Tetsu O, Tidyman WE, et al. Germline mutations in genes within the MAPK pathway cause cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Science. 2006;311:1287-1290.

- Kavamura MI, Peres CA, Alchorne MM, et al. CFC index for the diagnosis of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:12-16.

- Siegel DH, McKenzie J, Frieden IJ, et al. Dermatological findings in 61 mutation-positive individuals with cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:521-529.

- Tartaglia M, Zampino G, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1:2-26.

- Lo FS, Lin JL, Kuo MT, et al. Noonan syndrome caused by germline KRAS mutation in Taiwan: report of two patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:919-923.

- Allanson JE, Roberts AE. Noonan syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1124/.

- Gripp KW, Lin AE. Costello syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1507/.

- Inoue S, Moriya M, Watanabe Y, et al. New BRAF knockin mice provide a pathogenetic mechanism of developmental defects and a therapeutic approach in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6553-6566.

Practice Points

- RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy.

- Skin manifestations may help in differentiating CFC syndrome from other RASopathies.

Bedside Cardiac Ultrasound to Aid in Diagnosing Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

Cardiac ultrasound is among the many beneficial applications of point-of-care (POC) ultrasound in the ED. This modality can prove extremely beneficial in evaluating the critically ill patient. For example, POC cardiac ultrasound not only permits the emergency physician (EP) to diagnose a pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade, but also perform a pericardiocentesis.1 The EP can also employ beside ultrasound to estimate an ejection fraction (EF) almost as well as cardiology services,2 look for signs of right-heart strain in patients with pulmonary embolism (PE),3 and guide fluid management in patients who have septic shock.4 In addition to only taking a few minutes to perform, POC cardiac ultrasound can also drastically change the course of management in some patients. Our case illustrates the use of POC ultrasound to diagnose Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a 64-year-old patient and guide management when she became unstable prior to cardiac catheterization.

Case

A 64-year-old white woman with a medical history of diabetes, obesity, and nephrolithiasis presented to the ED with chest pain and shortness of breath, which she stated had begun earlier in the day. The patient’s chest pain did not intensify upon exertion, but the shortness of breath worsened when she was in the supine position.

Three months prior, the patient had also presented to our ED with chest pain. Evaluation during that visit included a negative stress echocardiogram with an EF of 55%. At this second visit, an electrocardiogram (ECG) showed new T-wave inversions in the anterior, lateral, and inferior leads. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 107/63 mm Hg; heart rate, 100 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.9°F. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air when patient was sitting upright, but decreased to 90% when she was supine. A chest X-ray showed left basilar atelectasis with a trace effusion. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable for the following: troponin I, 2.99 ng/mL; D-dimer, 294 ng/mL; and brain natriuretic peptide, 559 pg/mL.

Given the patient’s vital signs and positive troponin I level, a computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered to assess for a PE. This was done despite the patient’s negative D-dimer results, as it was felt that she was not low-risk for PE. At the same time the CT scan was ordered, a POC cardiac ultrasound was performed to assess for signs of right heart strain.

Based on the ultrasound findings and a normal EF 3 months prior, there was concern for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The patient was further questioned as to the events surrounding the onset of her chest pain. She informed the EP the pain started when she learned that she might be evicted from her home.

The CT scan was negative for PE. The consulting cardiologist was informed of the results of the ultrasound findings, and the patient was given aspirin, heparin, morphine, and furosemide, and was admitted to the cardiac progressive unit. She was also initially given morphine for pain management, but due to intolerance, she was switched to nitroglycerin.

During the first evening of her inpatient stay, the patient experienced acute changes in her chest pain that resulted in activating the rapid response team. Secondary to the information gathered in the ED, the patient was managed conservatively and was evaluated by a physician extender who repeated laboratory studies, provided supplemental potassium and magnesium, and ordered another ECG in consultation with the cardiologist (who was caring for the patient via telephone). In the morning, the patient continued to have chest pain, and a repeat ECG showed worsening of previous T-wave inversions. Based on these findings, the cardiologist ordered cardiac catheterization.

On hospital day 2, the cardiologist performed another echocardiogram, which confirmed the low EF of 20% with severe global hypokinesis with sparing of the basal segments. Cardiac catheterization showed no significant disease (20% lesion in the mid-left anterior descending artery) with the left ventriculogram showing an EF of 10%, cardiac output of 3.7, and cardiac index of 1.8, confirming the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The patient remained in the hospital for a total of 8 days while awaiting a life vest; however, a repeat echocardiogram on hospital day 8 showed an EF of 55%.

Discussion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is an acute, stress-induced cardiomyopathy that was first described in Japan in the early 1990s.5 It is thought to be due to catecholamine-induced dysfunction from a stressful event,6-8 such as the death of a loved one, which is why it is often referred to as “broken heart syndrome.” However there are case reports highlighting other causes of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, such as cocaine use,9 scuba diving,10 and diabetic ketoacidosis combined with hypothermia.11

Patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy will frequently have ECG abnormalities, including ST-segment elevation or depression, or T-wave changes; troponin levels also may be elevated. The majority of patients (>80%) are postmenopausal women, typically aged 50 to 75 years.6,12 Echocardiogram findings in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy show significant left ventricular (LV) dysfunction or regional dysfunction that is not in one coronary artery distribution.12,13 There will often be apical dilation or ballooning with dyskinesia but more preserved function at the base and normal dimensions.14,15 A negative cardiac catheterization or catheterization in the absence of significant disease is required to confirm the diagnosis.16 The LV function usually returns to baseline in 1 to 4 weeks, but there can be recurrence in some patients.6,17 The condition is also associated with a large burden of morbidity and mortality.6,18 In a case series by Gopalakrishnan et al6 of 56 patients, there was an 8.9% in-hospital mortality rate and an additional 17.9% out-of-hospital mortality rate even in patients in whom LV function had returned to normal.

In a review by Gianni et al,19 4.2% of patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy present with or go into cardiogenic shock at some point during admission, and up to 2% of patients who present with acute myocardial infarction have Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Patients can go into cardiogenic shock due to depressed EF or LV outflow tract obstruction from hyperkinesis of the basilar segments. Some of these patients may be sent directly to the catheter laboratory based on ST elevations on ECG, in which case the diagnosis is made there. Our patient, however, did not have ST elevation and later became unstable on the floor. Citro et al20 suggest that a patient with a predisposition for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (eg, postmenopausal patients, those who experienced a trigger event), in the right clinical setting and without ST-segment elevation on ECG, could be managed more conservatively with delayed cardiac angiography or CT angiography (CTA) evaluation of the coronary arteries (sparing the patient an invasive procedure)—as long as ultrasound was consistent with typical Takotsubo cardiomyopathy findings. However, CTA is still needed to make the diagnosis.

At this time, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy should remain an important part of the differential diagnosis for emergency patients who have chest pain—especially for postmenopausal women with a history of significant stressor—as early recognition can lead to better patient care.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of POC ultrasound in the management of patients in the ED and after admission. The care of our patient was enhanced by the ability to take a real-time look at her EF and cardiac function at the time of admission through bedside ultrasound. This information guided her management and optimized stabilization.

1. Goodman A, Perera P, Mailhot T, Mandavia D. The role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5(1):72-75. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.93118.

2. Unlüer EE, Karagöz A, Akoğlu H, Bayata S. Visual estimation of bedside echocardiographic ejection fraction by emergency physicians. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(2):221-226. doi:10.5811/westjem.2013.9.16185.

3. McConnell MV, Solomon SD, Rayan ME, Come PC, Goldhaber SZ, Lee RT. Regional right ventricular dysfunction detected by echocardiography in acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(4):469-473.

4. Coen D, Cortellaro F, Pasini S, et al. Towards a less invasive approach to the early goal-directed treatment of septic shock in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(6):563-568. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.011.

5. Dote K, Sato H, Tateishi H, Uchida T, Ishihara M. [Myocardial stunning due to simultaneous multivessel coronary spasms: a review of 5 cases.] J Cardiol. 1991;21(2):203-214.

6. Gopalakrishnan M, Hassan A, Villines D, Nasr S, Chandrasekaran M, Klein LW. Predictors of short- and long-term outcomes of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(10):1586-1590. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.08.024.

7. Paur H, Wright PT, Sikkel MB, et al. High levels of circulating epinephrine trigger apical cardiodepression in a β2-adrenergic receptor/Gi-dependent manner: a new model of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2012;126(6):697-706. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.111591.

8. Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):539-548. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043046.

9. Butterfield M, Riguzzi C, Frenkel O, Nagdev A. Stimulant-related Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(3):476.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2014.08.058.

10. Baber A, Nair SU, Duggal S, Bhatti S, Sundlof DW. Stress cardiomyopathy caused by diving: case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(2):277-280. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.09.045.

11. Katayama Y, Hifumi T, Inoue J, Koido Y. A case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy induced by accidental hypothermia and diabetic ketoacidosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:1-3. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-008143.

12. Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):858-865.

13. Virani SS, Khan AN, Mendoza CE, Ferreira AC, de Marchena E. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, or brokenheart syndrome. Tex Heart Inst J. 2007;34(1):76-79.

14. Okura H. Echocardiographic assessment of takotsubo cardiomyopathy: beyond apical ballooning. J Echocardiogr. 2016;14(1):13-20. doi:10.1007/s12574-015-0271-3.

15. Naser N, Buksa M, Kusljugic Z, Terzic I, Sokolovic S, Hodzic E. The role of echocardiography in diagnosis and follow up of patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy or acute ballooning syndrome. Med Arh. 2011;65(5):287-290.

16. Ono R, Falcão LM. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy systematic review: Pathophysiologic process, clinical presentation and diagnostic approach to Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2016;209:196-205. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.012.

17. Opolski G, Budnik M, Kochanowski J, Kowalik R, Piatkowski R, Kochman J. Four episodes of takotsubo cardiomyopathy in one patient. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:53-54. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.048.

18. Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929-938.

19. Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(13):1523-1529. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032.

20. Citro R, Lyon AR, Meimoun P, et al. Standard and advanced echocardiography in Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy: clinical and prognostic implications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(1):57-74. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2014.08.020.

Cardiac ultrasound is among the many beneficial applications of point-of-care (POC) ultrasound in the ED. This modality can prove extremely beneficial in evaluating the critically ill patient. For example, POC cardiac ultrasound not only permits the emergency physician (EP) to diagnose a pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade, but also perform a pericardiocentesis.1 The EP can also employ beside ultrasound to estimate an ejection fraction (EF) almost as well as cardiology services,2 look for signs of right-heart strain in patients with pulmonary embolism (PE),3 and guide fluid management in patients who have septic shock.4 In addition to only taking a few minutes to perform, POC cardiac ultrasound can also drastically change the course of management in some patients. Our case illustrates the use of POC ultrasound to diagnose Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a 64-year-old patient and guide management when she became unstable prior to cardiac catheterization.

Case

A 64-year-old white woman with a medical history of diabetes, obesity, and nephrolithiasis presented to the ED with chest pain and shortness of breath, which she stated had begun earlier in the day. The patient’s chest pain did not intensify upon exertion, but the shortness of breath worsened when she was in the supine position.

Three months prior, the patient had also presented to our ED with chest pain. Evaluation during that visit included a negative stress echocardiogram with an EF of 55%. At this second visit, an electrocardiogram (ECG) showed new T-wave inversions in the anterior, lateral, and inferior leads. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 107/63 mm Hg; heart rate, 100 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.9°F. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air when patient was sitting upright, but decreased to 90% when she was supine. A chest X-ray showed left basilar atelectasis with a trace effusion. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable for the following: troponin I, 2.99 ng/mL; D-dimer, 294 ng/mL; and brain natriuretic peptide, 559 pg/mL.

Given the patient’s vital signs and positive troponin I level, a computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered to assess for a PE. This was done despite the patient’s negative D-dimer results, as it was felt that she was not low-risk for PE. At the same time the CT scan was ordered, a POC cardiac ultrasound was performed to assess for signs of right heart strain.

Based on the ultrasound findings and a normal EF 3 months prior, there was concern for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The patient was further questioned as to the events surrounding the onset of her chest pain. She informed the EP the pain started when she learned that she might be evicted from her home.

The CT scan was negative for PE. The consulting cardiologist was informed of the results of the ultrasound findings, and the patient was given aspirin, heparin, morphine, and furosemide, and was admitted to the cardiac progressive unit. She was also initially given morphine for pain management, but due to intolerance, she was switched to nitroglycerin.

During the first evening of her inpatient stay, the patient experienced acute changes in her chest pain that resulted in activating the rapid response team. Secondary to the information gathered in the ED, the patient was managed conservatively and was evaluated by a physician extender who repeated laboratory studies, provided supplemental potassium and magnesium, and ordered another ECG in consultation with the cardiologist (who was caring for the patient via telephone). In the morning, the patient continued to have chest pain, and a repeat ECG showed worsening of previous T-wave inversions. Based on these findings, the cardiologist ordered cardiac catheterization.

On hospital day 2, the cardiologist performed another echocardiogram, which confirmed the low EF of 20% with severe global hypokinesis with sparing of the basal segments. Cardiac catheterization showed no significant disease (20% lesion in the mid-left anterior descending artery) with the left ventriculogram showing an EF of 10%, cardiac output of 3.7, and cardiac index of 1.8, confirming the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The patient remained in the hospital for a total of 8 days while awaiting a life vest; however, a repeat echocardiogram on hospital day 8 showed an EF of 55%.

Discussion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is an acute, stress-induced cardiomyopathy that was first described in Japan in the early 1990s.5 It is thought to be due to catecholamine-induced dysfunction from a stressful event,6-8 such as the death of a loved one, which is why it is often referred to as “broken heart syndrome.” However there are case reports highlighting other causes of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, such as cocaine use,9 scuba diving,10 and diabetic ketoacidosis combined with hypothermia.11

Patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy will frequently have ECG abnormalities, including ST-segment elevation or depression, or T-wave changes; troponin levels also may be elevated. The majority of patients (>80%) are postmenopausal women, typically aged 50 to 75 years.6,12 Echocardiogram findings in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy show significant left ventricular (LV) dysfunction or regional dysfunction that is not in one coronary artery distribution.12,13 There will often be apical dilation or ballooning with dyskinesia but more preserved function at the base and normal dimensions.14,15 A negative cardiac catheterization or catheterization in the absence of significant disease is required to confirm the diagnosis.16 The LV function usually returns to baseline in 1 to 4 weeks, but there can be recurrence in some patients.6,17 The condition is also associated with a large burden of morbidity and mortality.6,18 In a case series by Gopalakrishnan et al6 of 56 patients, there was an 8.9% in-hospital mortality rate and an additional 17.9% out-of-hospital mortality rate even in patients in whom LV function had returned to normal.

In a review by Gianni et al,19 4.2% of patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy present with or go into cardiogenic shock at some point during admission, and up to 2% of patients who present with acute myocardial infarction have Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Patients can go into cardiogenic shock due to depressed EF or LV outflow tract obstruction from hyperkinesis of the basilar segments. Some of these patients may be sent directly to the catheter laboratory based on ST elevations on ECG, in which case the diagnosis is made there. Our patient, however, did not have ST elevation and later became unstable on the floor. Citro et al20 suggest that a patient with a predisposition for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (eg, postmenopausal patients, those who experienced a trigger event), in the right clinical setting and without ST-segment elevation on ECG, could be managed more conservatively with delayed cardiac angiography or CT angiography (CTA) evaluation of the coronary arteries (sparing the patient an invasive procedure)—as long as ultrasound was consistent with typical Takotsubo cardiomyopathy findings. However, CTA is still needed to make the diagnosis.

At this time, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy should remain an important part of the differential diagnosis for emergency patients who have chest pain—especially for postmenopausal women with a history of significant stressor—as early recognition can lead to better patient care.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of POC ultrasound in the management of patients in the ED and after admission. The care of our patient was enhanced by the ability to take a real-time look at her EF and cardiac function at the time of admission through bedside ultrasound. This information guided her management and optimized stabilization.

Cardiac ultrasound is among the many beneficial applications of point-of-care (POC) ultrasound in the ED. This modality can prove extremely beneficial in evaluating the critically ill patient. For example, POC cardiac ultrasound not only permits the emergency physician (EP) to diagnose a pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade, but also perform a pericardiocentesis.1 The EP can also employ beside ultrasound to estimate an ejection fraction (EF) almost as well as cardiology services,2 look for signs of right-heart strain in patients with pulmonary embolism (PE),3 and guide fluid management in patients who have septic shock.4 In addition to only taking a few minutes to perform, POC cardiac ultrasound can also drastically change the course of management in some patients. Our case illustrates the use of POC ultrasound to diagnose Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a 64-year-old patient and guide management when she became unstable prior to cardiac catheterization.

Case

A 64-year-old white woman with a medical history of diabetes, obesity, and nephrolithiasis presented to the ED with chest pain and shortness of breath, which she stated had begun earlier in the day. The patient’s chest pain did not intensify upon exertion, but the shortness of breath worsened when she was in the supine position.

Three months prior, the patient had also presented to our ED with chest pain. Evaluation during that visit included a negative stress echocardiogram with an EF of 55%. At this second visit, an electrocardiogram (ECG) showed new T-wave inversions in the anterior, lateral, and inferior leads. Vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure, 107/63 mm Hg; heart rate, 100 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 97.9°F. Oxygen saturation was 97% on room air when patient was sitting upright, but decreased to 90% when she was supine. A chest X-ray showed left basilar atelectasis with a trace effusion. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable for the following: troponin I, 2.99 ng/mL; D-dimer, 294 ng/mL; and brain natriuretic peptide, 559 pg/mL.

Given the patient’s vital signs and positive troponin I level, a computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered to assess for a PE. This was done despite the patient’s negative D-dimer results, as it was felt that she was not low-risk for PE. At the same time the CT scan was ordered, a POC cardiac ultrasound was performed to assess for signs of right heart strain.

Based on the ultrasound findings and a normal EF 3 months prior, there was concern for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The patient was further questioned as to the events surrounding the onset of her chest pain. She informed the EP the pain started when she learned that she might be evicted from her home.

The CT scan was negative for PE. The consulting cardiologist was informed of the results of the ultrasound findings, and the patient was given aspirin, heparin, morphine, and furosemide, and was admitted to the cardiac progressive unit. She was also initially given morphine for pain management, but due to intolerance, she was switched to nitroglycerin.

During the first evening of her inpatient stay, the patient experienced acute changes in her chest pain that resulted in activating the rapid response team. Secondary to the information gathered in the ED, the patient was managed conservatively and was evaluated by a physician extender who repeated laboratory studies, provided supplemental potassium and magnesium, and ordered another ECG in consultation with the cardiologist (who was caring for the patient via telephone). In the morning, the patient continued to have chest pain, and a repeat ECG showed worsening of previous T-wave inversions. Based on these findings, the cardiologist ordered cardiac catheterization.

On hospital day 2, the cardiologist performed another echocardiogram, which confirmed the low EF of 20% with severe global hypokinesis with sparing of the basal segments. Cardiac catheterization showed no significant disease (20% lesion in the mid-left anterior descending artery) with the left ventriculogram showing an EF of 10%, cardiac output of 3.7, and cardiac index of 1.8, confirming the diagnosis of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The patient remained in the hospital for a total of 8 days while awaiting a life vest; however, a repeat echocardiogram on hospital day 8 showed an EF of 55%.

Discussion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is an acute, stress-induced cardiomyopathy that was first described in Japan in the early 1990s.5 It is thought to be due to catecholamine-induced dysfunction from a stressful event,6-8 such as the death of a loved one, which is why it is often referred to as “broken heart syndrome.” However there are case reports highlighting other causes of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, such as cocaine use,9 scuba diving,10 and diabetic ketoacidosis combined with hypothermia.11

Patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy will frequently have ECG abnormalities, including ST-segment elevation or depression, or T-wave changes; troponin levels also may be elevated. The majority of patients (>80%) are postmenopausal women, typically aged 50 to 75 years.6,12 Echocardiogram findings in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy show significant left ventricular (LV) dysfunction or regional dysfunction that is not in one coronary artery distribution.12,13 There will often be apical dilation or ballooning with dyskinesia but more preserved function at the base and normal dimensions.14,15 A negative cardiac catheterization or catheterization in the absence of significant disease is required to confirm the diagnosis.16 The LV function usually returns to baseline in 1 to 4 weeks, but there can be recurrence in some patients.6,17 The condition is also associated with a large burden of morbidity and mortality.6,18 In a case series by Gopalakrishnan et al6 of 56 patients, there was an 8.9% in-hospital mortality rate and an additional 17.9% out-of-hospital mortality rate even in patients in whom LV function had returned to normal.

In a review by Gianni et al,19 4.2% of patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy present with or go into cardiogenic shock at some point during admission, and up to 2% of patients who present with acute myocardial infarction have Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Patients can go into cardiogenic shock due to depressed EF or LV outflow tract obstruction from hyperkinesis of the basilar segments. Some of these patients may be sent directly to the catheter laboratory based on ST elevations on ECG, in which case the diagnosis is made there. Our patient, however, did not have ST elevation and later became unstable on the floor. Citro et al20 suggest that a patient with a predisposition for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (eg, postmenopausal patients, those who experienced a trigger event), in the right clinical setting and without ST-segment elevation on ECG, could be managed more conservatively with delayed cardiac angiography or CT angiography (CTA) evaluation of the coronary arteries (sparing the patient an invasive procedure)—as long as ultrasound was consistent with typical Takotsubo cardiomyopathy findings. However, CTA is still needed to make the diagnosis.

At this time, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy should remain an important part of the differential diagnosis for emergency patients who have chest pain—especially for postmenopausal women with a history of significant stressor—as early recognition can lead to better patient care.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of POC ultrasound in the management of patients in the ED and after admission. The care of our patient was enhanced by the ability to take a real-time look at her EF and cardiac function at the time of admission through bedside ultrasound. This information guided her management and optimized stabilization.

1. Goodman A, Perera P, Mailhot T, Mandavia D. The role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5(1):72-75. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.93118.

2. Unlüer EE, Karagöz A, Akoğlu H, Bayata S. Visual estimation of bedside echocardiographic ejection fraction by emergency physicians. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(2):221-226. doi:10.5811/westjem.2013.9.16185.

3. McConnell MV, Solomon SD, Rayan ME, Come PC, Goldhaber SZ, Lee RT. Regional right ventricular dysfunction detected by echocardiography in acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(4):469-473.

4. Coen D, Cortellaro F, Pasini S, et al. Towards a less invasive approach to the early goal-directed treatment of septic shock in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(6):563-568. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.011.