User login

HSPCs shape their own environment, team says

in the bone marrow

New research has revealed a mechanism through which hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) control both their own proliferation and the characteristics of the niche that houses them.

Researchers detected high expression of the protein E-selectin ligand-1 (ESL-1) in HSPCs and also found that ESL-1 controls HSPCs’ production of the cytokine TGF-β.

The team said this is important because TGF-β has antiproliferative properties and is essential for impeding the loss of HSPCs in some diseases, such as some types of anemia.

The researchers also showed that HSPCs lacking ESL-1 are resistant to chemotherapeutic and cytotoxic agents.

These results suggest ESL-1 is a potential target for therapies aimed at improving bone marrow regeneration after chemotherapy or for expanding the HSPC population in preparation for donation.

Magdalena Leiva, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares in Madrid, Spain, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

The researchers first found that ESL-1 deficiency causes HSPC quiescence and expansion, and elevated TGF-β causes quiescence in the absence of ESL-1. In addition, ESL-1 controls HSPC proliferation independently of E-selectin, and HSPCs are a relevant source of TGF-β.

The team also discovered that ESL-1 exerts local effects on distinct cell populations in the stromal niche. They found that hematopoietic-borne ESL-1 can control HSPC proliferation directly through cytokine secretion, and/or indirectly through repressive effects on supportive niche cells.

According to Dr Leiva, this finding opens the path to new therapies “that use genetically modified stem cells to treat hematological diseases, such as certain types of leukemia, in which the hematopoietic niche and HSPCs are very affected.”

The researchers made these discoveries by analyzing the bone marrow of mice deficient in ESL-1. In the absence of ESL-1, HSPCs proliferated less and were therefore of superior quality and more suitable for potential therapeutic applications, the team found.

“We see that these cells are resistant to processes associated with bone marrow damage, such as cell death triggered by cytotoxic agents,” Dr Leiva said.

She and her colleagues found that stem cells lacking ESL-1 were resistant to the deleterious effects of 5-fluorouracil and hydroxyurea. They said this suggests ESL-1 is a possible therapeutic target for improved regeneration of the bone marrow during chemotherapy. ![]()

in the bone marrow

New research has revealed a mechanism through which hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) control both their own proliferation and the characteristics of the niche that houses them.

Researchers detected high expression of the protein E-selectin ligand-1 (ESL-1) in HSPCs and also found that ESL-1 controls HSPCs’ production of the cytokine TGF-β.

The team said this is important because TGF-β has antiproliferative properties and is essential for impeding the loss of HSPCs in some diseases, such as some types of anemia.

The researchers also showed that HSPCs lacking ESL-1 are resistant to chemotherapeutic and cytotoxic agents.

These results suggest ESL-1 is a potential target for therapies aimed at improving bone marrow regeneration after chemotherapy or for expanding the HSPC population in preparation for donation.

Magdalena Leiva, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares in Madrid, Spain, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

The researchers first found that ESL-1 deficiency causes HSPC quiescence and expansion, and elevated TGF-β causes quiescence in the absence of ESL-1. In addition, ESL-1 controls HSPC proliferation independently of E-selectin, and HSPCs are a relevant source of TGF-β.

The team also discovered that ESL-1 exerts local effects on distinct cell populations in the stromal niche. They found that hematopoietic-borne ESL-1 can control HSPC proliferation directly through cytokine secretion, and/or indirectly through repressive effects on supportive niche cells.

According to Dr Leiva, this finding opens the path to new therapies “that use genetically modified stem cells to treat hematological diseases, such as certain types of leukemia, in which the hematopoietic niche and HSPCs are very affected.”

The researchers made these discoveries by analyzing the bone marrow of mice deficient in ESL-1. In the absence of ESL-1, HSPCs proliferated less and were therefore of superior quality and more suitable for potential therapeutic applications, the team found.

“We see that these cells are resistant to processes associated with bone marrow damage, such as cell death triggered by cytotoxic agents,” Dr Leiva said.

She and her colleagues found that stem cells lacking ESL-1 were resistant to the deleterious effects of 5-fluorouracil and hydroxyurea. They said this suggests ESL-1 is a possible therapeutic target for improved regeneration of the bone marrow during chemotherapy. ![]()

in the bone marrow

New research has revealed a mechanism through which hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) control both their own proliferation and the characteristics of the niche that houses them.

Researchers detected high expression of the protein E-selectin ligand-1 (ESL-1) in HSPCs and also found that ESL-1 controls HSPCs’ production of the cytokine TGF-β.

The team said this is important because TGF-β has antiproliferative properties and is essential for impeding the loss of HSPCs in some diseases, such as some types of anemia.

The researchers also showed that HSPCs lacking ESL-1 are resistant to chemotherapeutic and cytotoxic agents.

These results suggest ESL-1 is a potential target for therapies aimed at improving bone marrow regeneration after chemotherapy or for expanding the HSPC population in preparation for donation.

Magdalena Leiva, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares in Madrid, Spain, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

The researchers first found that ESL-1 deficiency causes HSPC quiescence and expansion, and elevated TGF-β causes quiescence in the absence of ESL-1. In addition, ESL-1 controls HSPC proliferation independently of E-selectin, and HSPCs are a relevant source of TGF-β.

The team also discovered that ESL-1 exerts local effects on distinct cell populations in the stromal niche. They found that hematopoietic-borne ESL-1 can control HSPC proliferation directly through cytokine secretion, and/or indirectly through repressive effects on supportive niche cells.

According to Dr Leiva, this finding opens the path to new therapies “that use genetically modified stem cells to treat hematological diseases, such as certain types of leukemia, in which the hematopoietic niche and HSPCs are very affected.”

The researchers made these discoveries by analyzing the bone marrow of mice deficient in ESL-1. In the absence of ESL-1, HSPCs proliferated less and were therefore of superior quality and more suitable for potential therapeutic applications, the team found.

“We see that these cells are resistant to processes associated with bone marrow damage, such as cell death triggered by cytotoxic agents,” Dr Leiva said.

She and her colleagues found that stem cells lacking ESL-1 were resistant to the deleterious effects of 5-fluorouracil and hydroxyurea. They said this suggests ESL-1 is a possible therapeutic target for improved regeneration of the bone marrow during chemotherapy. ![]()

Itchy Papules and Plaques on the Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

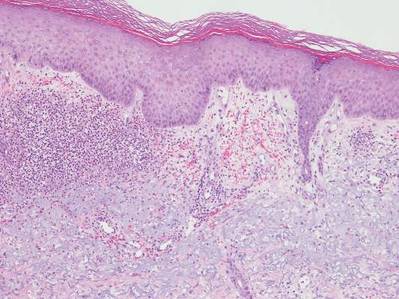

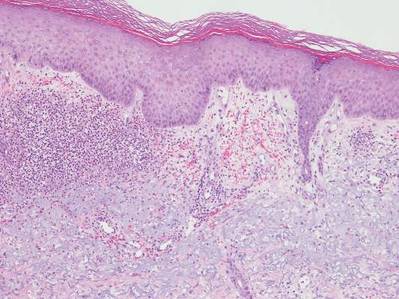

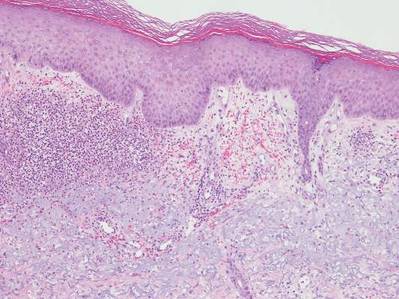

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

The Diagnosis: Neutrophilic Dermatosis of the Dorsal Hands

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) is considered to be an uncommon localized variant of Sweet syndrome (SS). The term pustular vasculitis originally was used to describe this condition by Strutton et al1 in 1995 due to the presence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histology. In 2000, Galaria et al2 suggested this eruption was a localized variant of SS based on clinical presentations that demonstrated associated fever and lack of necrotizing vasculitis and proposed the term neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands to describe the condition. Cases of similar cutaneous eruptions on the hands associated with fever, leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocytoclasis have since been reported.3-5 Some authors have concluded that these eruptions, previously termed atypical pyoderma gangrenosum and pustular vasculitis of the hands, represent a single disease entity and should be designated as NDDH.3,4

Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands characteristically presents with hemorrhagic pustular ulcerations limited to or predominantly located on the dorsal hands, as seen in our patient. Histopathologically, NDDH demonstrates a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the upper dermis and marked papillary dermal edema; a punch biopsy specimen from our patient was consistent with these features (Figure). Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Vasculitis, if present, is more commonly seen in eruptions of longer duration (ie, months to years) and is thought to be secondary to the dense neutrophilic infiltrate and not a primary vasculitis.3,6,7 Similar to classic SS, NDDH is inherently responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Successful treatment also has been reported with dapsone, colchicine, sulfapyridine, potassium iodide, intralesional and topical corticosteroids, and topical tacrolimus.2-8 Oral minocycline has shown variable results.3,4

Numerous case series have demonstrated that a majority of cases of NDDH are associated with hematologic or solid organ malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), inflammatory bowel disease, or other underlying systemic diseases.3,5,9 It is important for dermatologists to recognize NDDH, distinguish it from localized infection, and perform the appropriate workup (eg, basic laboratory tests [complete blood count, complete metabolic panel], age-appropriate malignancy screening, colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy) to exclude associated systemic diseases.

Our patient demonstrated characteristic clinical and histopathologic findings of NDDH in association with early MDS and possible common bile duct (CBD) malignancy. The lesions showed a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. The initial differential diagnoses included NDDH or other neutrophilic dermatosis, phototoxic drug eruption, and atypical mycobacterial or fungal infection (cultures were negative in our patient). Physical examination and histopathologic findings along with the patient’s clinical course and rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy supported the diagnosis of NDDH. Our patient’s multiple comorbidities, including macrocytic anemia, MDS, and potential CBD malignancy, presented a therapeutic challenge. Oral dapsone, an ideal steroid-sparing agent for neutrophilic dermatoses including NDDH, was avoided given its associated hematologic side effects including hemolysis, methemoglobinemia, and possible agranulocytosis. To date, the patient has not received any further treatment for MDS or the CBD mass and continues regular follow-up with hematology, gastroenterology, and dermatology.

This case highlights the importance of including NDDH in the differential diagnosis of papules and plaques on the hands, especially in patients with known malignancies, and emphasizes the association of neutrophilic dermatoses with malignancy and systemic disease.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

- Strutton G, Weedon D, Robertson I. Pustular vasculitis of the hands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:192-198.

- Galaria NA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Kligman D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: pustular vasculitis revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:870-874.

- Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

- DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM. Neutrophilic dermatosis (pustular vasculitis) of the dorsal hands. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:361-365.

- Weening RH, Bruce AJ, McEvoy MT, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: four new cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:95-102.

- Malone JC, Slone SP, Wills-Frank LA, et al. Vascular inflammation (vasculitis) in Sweet syndrome: a clinicopathologic study of 28 biopsy specimens from 21 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:345-349.

- Cohen PR. Skin lesions of Sweet syndrome and its dorsal hand variant contain vasculitis: an oxymoron or an epiphenomenon? Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:400-403.

- Del Pozo J, Sacristán F, Martínez W, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol. 2007;34:243-247.

- Callen JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:409-419.

A 69-year-old man presented with tender, itchy papules and plaques on the bilateral dorsal hands of 2 months’ duration. The plaques had started as small papules that gradually enlarged and then became ulcerated. The patient denied prior trauma or constitutional symptoms. Laboratory testing revealed macrocytic anemia, thrombocytosis, and hypoalbuminemia. A complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were otherwise unremarkable. A recent bone marrow biopsy for macrocytic anemia performed prior to the current presentation suggested early myelodysplastic syndrome, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography revealed a large mass in the common bile duct that was suspicious for malignancy. Two punch biopsies were performed and were negative for fungus and acid-fast bacteria and positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Treatment with topical clobetasol 0.05% twice daily was initiated with complete healing of the plaques on the hands after 2 weeks of use; however, the patient continued to develop new ulcerated papulonodules distally.

Dermal Fillers for Aesthetic Rejuvenation

What does your patient need to know at the first consultation?

Several things are important. First, I have a discussion with the patient to find out exactly what bothers him or her the most. Some patients have very specific areas they would like to address while others simply come in and say, “Please make me look better/less tired/younger.” It’s very important to review all of the treatment options with the patient. Not only are there many different types of fillers, but there also are differences among the products within each category; for example, some hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers have similar clinical properties and applications (eg, Juvéderm Voluma XC [Allergan, Inc], Restylane Lyft [Galderma Laboratories, LP]), but they differ from other similar HA fillers (eg, Juvéderm Ultra XC [Allergan, Inc], Restylane [Galderma Laboratories, LP], Belotero Balance [Merz North America, Inc]) with regard to G′, molecular weight, and crosslinking. I also discuss longer-lasting filler materials such as calcium hydroxylapatite (eg, Radiesse [Merz North America, Inc]) and injectable poly-L-lactic acid (Sculptra Aesthetic [Galderma Laboratories, LP]), which stimulates collagen production.

For patients that have never had filler treatments before, I may try to steer them in the direction of using an HA filler simply because the effects can be reversed if they aren’t happy with the results. It’s also important to discuss how much filler the patient will need to achieve the desired effect. It’s important to take the patient’s budget into account when formulating a treatment plan. I also tell my patients that fillers alone may not achieve the desired results and that they also may need toxin treatment (eg, onabotulinumtoxinA [Botox Cosmetic (Allergan, Inc)], incobotulinumtoxinA [Xeomin (Merz North America, Inc)], abobotulinumtoxinA [Dysport (Galderma Laboratories, LP)]), and possibly laser treatment to improve the overall skin appearance. Additionally, I always discuss a skin care routine and the need for daily sunscreen use.

What procedures are most commonly requested in your practice?

In my practice, patients present with several common complaints. Thin, downturned lips are a common treatment area, and many patients are concerned about jowls and flattened cheeks. Patients also often seek treatment for prominent nasolabial and melolabial folds and “smoker’s lines.” I typically discuss contouring and shaping more than simply filling lines. We try to take a wholistic approach to improve the overall appearance of the face as opposed to just focusing on certain lines and wrinkles.

What are your go-to injection techniques?

All fillers have a place in my practice. I use Juvéderm Ultra XC, Restylane, and Belotero Balance to improve the appearance of tear troughs. Juvéderm Ultra Plus XC and Restylane are really great for deep creases like nasolabial folds. Belotero Balance and Restylane Silk are especially good for treating perioral wrinkles and lines. I use Juvéderm Voluma XC, Restylane Lyft, and Radiesse more for shaping and contouring, but these products also work great for adding volume. I use Sculptra Aesthetic as a foundation for patients who need volume and collagen stimulation. Radiesse is a great option for hand rejuvenation and was recently approved for this treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration.

There are numerous injection techniques that I find useful, including depot, serial puncture, fanning, and tower techniques. I recommend learning all of these and then picking what works for you. As an overall principle, I try to minimize tissue trauma and the possibility of bruising. Most importantly, one has to know the anatomic location of the injection site and stay away from danger zones. It’s also very important to always draw back to ensure that one isn’t injecting into a vessel.

I think it’s smart to start with HA fillers since the effects are reversible. After the physician becomes more comfortable with performing filler procedures, I would recommend moving on to longer-lasting fillers.

What complications/side effects should physicians be aware of?

The most common complications associated with dermal fillers are bruising and swelling. The risks for these side effects can be decreased by icing the treatment area immediately before and after the procedure. Also, I often recommend products containing arnica (topical and/or oral) for patients who tend to bruise. Nodule formation, skin necrosis, infection, and vascular occlusion in the immediate or distal areas can be avoided with proper training and knowledge of local anatomy; for example, it’s important to always draw back before injecting to ensure you aren’t injecting into a vascular structure. Knowledge of local anatomy and its variations also is important in order to avoid these danger zones. In very rare cases, blindness and stroke may occur following treatment with dermal fillers.

Suggested Readings

Sadick N, ed. Augmentation Fillers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Small R, Hoang D. A Practical Guide to Dermal Filler Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Willams & Wilkins; 2011.

What does your patient need to know at the first consultation?

Several things are important. First, I have a discussion with the patient to find out exactly what bothers him or her the most. Some patients have very specific areas they would like to address while others simply come in and say, “Please make me look better/less tired/younger.” It’s very important to review all of the treatment options with the patient. Not only are there many different types of fillers, but there also are differences among the products within each category; for example, some hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers have similar clinical properties and applications (eg, Juvéderm Voluma XC [Allergan, Inc], Restylane Lyft [Galderma Laboratories, LP]), but they differ from other similar HA fillers (eg, Juvéderm Ultra XC [Allergan, Inc], Restylane [Galderma Laboratories, LP], Belotero Balance [Merz North America, Inc]) with regard to G′, molecular weight, and crosslinking. I also discuss longer-lasting filler materials such as calcium hydroxylapatite (eg, Radiesse [Merz North America, Inc]) and injectable poly-L-lactic acid (Sculptra Aesthetic [Galderma Laboratories, LP]), which stimulates collagen production.

For patients that have never had filler treatments before, I may try to steer them in the direction of using an HA filler simply because the effects can be reversed if they aren’t happy with the results. It’s also important to discuss how much filler the patient will need to achieve the desired effect. It’s important to take the patient’s budget into account when formulating a treatment plan. I also tell my patients that fillers alone may not achieve the desired results and that they also may need toxin treatment (eg, onabotulinumtoxinA [Botox Cosmetic (Allergan, Inc)], incobotulinumtoxinA [Xeomin (Merz North America, Inc)], abobotulinumtoxinA [Dysport (Galderma Laboratories, LP)]), and possibly laser treatment to improve the overall skin appearance. Additionally, I always discuss a skin care routine and the need for daily sunscreen use.

What procedures are most commonly requested in your practice?

In my practice, patients present with several common complaints. Thin, downturned lips are a common treatment area, and many patients are concerned about jowls and flattened cheeks. Patients also often seek treatment for prominent nasolabial and melolabial folds and “smoker’s lines.” I typically discuss contouring and shaping more than simply filling lines. We try to take a wholistic approach to improve the overall appearance of the face as opposed to just focusing on certain lines and wrinkles.

What are your go-to injection techniques?

All fillers have a place in my practice. I use Juvéderm Ultra XC, Restylane, and Belotero Balance to improve the appearance of tear troughs. Juvéderm Ultra Plus XC and Restylane are really great for deep creases like nasolabial folds. Belotero Balance and Restylane Silk are especially good for treating perioral wrinkles and lines. I use Juvéderm Voluma XC, Restylane Lyft, and Radiesse more for shaping and contouring, but these products also work great for adding volume. I use Sculptra Aesthetic as a foundation for patients who need volume and collagen stimulation. Radiesse is a great option for hand rejuvenation and was recently approved for this treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration.

There are numerous injection techniques that I find useful, including depot, serial puncture, fanning, and tower techniques. I recommend learning all of these and then picking what works for you. As an overall principle, I try to minimize tissue trauma and the possibility of bruising. Most importantly, one has to know the anatomic location of the injection site and stay away from danger zones. It’s also very important to always draw back to ensure that one isn’t injecting into a vessel.

I think it’s smart to start with HA fillers since the effects are reversible. After the physician becomes more comfortable with performing filler procedures, I would recommend moving on to longer-lasting fillers.

What complications/side effects should physicians be aware of?

The most common complications associated with dermal fillers are bruising and swelling. The risks for these side effects can be decreased by icing the treatment area immediately before and after the procedure. Also, I often recommend products containing arnica (topical and/or oral) for patients who tend to bruise. Nodule formation, skin necrosis, infection, and vascular occlusion in the immediate or distal areas can be avoided with proper training and knowledge of local anatomy; for example, it’s important to always draw back before injecting to ensure you aren’t injecting into a vascular structure. Knowledge of local anatomy and its variations also is important in order to avoid these danger zones. In very rare cases, blindness and stroke may occur following treatment with dermal fillers.

Suggested Readings

Sadick N, ed. Augmentation Fillers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Small R, Hoang D. A Practical Guide to Dermal Filler Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Willams & Wilkins; 2011.

What does your patient need to know at the first consultation?

Several things are important. First, I have a discussion with the patient to find out exactly what bothers him or her the most. Some patients have very specific areas they would like to address while others simply come in and say, “Please make me look better/less tired/younger.” It’s very important to review all of the treatment options with the patient. Not only are there many different types of fillers, but there also are differences among the products within each category; for example, some hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers have similar clinical properties and applications (eg, Juvéderm Voluma XC [Allergan, Inc], Restylane Lyft [Galderma Laboratories, LP]), but they differ from other similar HA fillers (eg, Juvéderm Ultra XC [Allergan, Inc], Restylane [Galderma Laboratories, LP], Belotero Balance [Merz North America, Inc]) with regard to G′, molecular weight, and crosslinking. I also discuss longer-lasting filler materials such as calcium hydroxylapatite (eg, Radiesse [Merz North America, Inc]) and injectable poly-L-lactic acid (Sculptra Aesthetic [Galderma Laboratories, LP]), which stimulates collagen production.

For patients that have never had filler treatments before, I may try to steer them in the direction of using an HA filler simply because the effects can be reversed if they aren’t happy with the results. It’s also important to discuss how much filler the patient will need to achieve the desired effect. It’s important to take the patient’s budget into account when formulating a treatment plan. I also tell my patients that fillers alone may not achieve the desired results and that they also may need toxin treatment (eg, onabotulinumtoxinA [Botox Cosmetic (Allergan, Inc)], incobotulinumtoxinA [Xeomin (Merz North America, Inc)], abobotulinumtoxinA [Dysport (Galderma Laboratories, LP)]), and possibly laser treatment to improve the overall skin appearance. Additionally, I always discuss a skin care routine and the need for daily sunscreen use.

What procedures are most commonly requested in your practice?

In my practice, patients present with several common complaints. Thin, downturned lips are a common treatment area, and many patients are concerned about jowls and flattened cheeks. Patients also often seek treatment for prominent nasolabial and melolabial folds and “smoker’s lines.” I typically discuss contouring and shaping more than simply filling lines. We try to take a wholistic approach to improve the overall appearance of the face as opposed to just focusing on certain lines and wrinkles.

What are your go-to injection techniques?

All fillers have a place in my practice. I use Juvéderm Ultra XC, Restylane, and Belotero Balance to improve the appearance of tear troughs. Juvéderm Ultra Plus XC and Restylane are really great for deep creases like nasolabial folds. Belotero Balance and Restylane Silk are especially good for treating perioral wrinkles and lines. I use Juvéderm Voluma XC, Restylane Lyft, and Radiesse more for shaping and contouring, but these products also work great for adding volume. I use Sculptra Aesthetic as a foundation for patients who need volume and collagen stimulation. Radiesse is a great option for hand rejuvenation and was recently approved for this treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration.

There are numerous injection techniques that I find useful, including depot, serial puncture, fanning, and tower techniques. I recommend learning all of these and then picking what works for you. As an overall principle, I try to minimize tissue trauma and the possibility of bruising. Most importantly, one has to know the anatomic location of the injection site and stay away from danger zones. It’s also very important to always draw back to ensure that one isn’t injecting into a vessel.

I think it’s smart to start with HA fillers since the effects are reversible. After the physician becomes more comfortable with performing filler procedures, I would recommend moving on to longer-lasting fillers.

What complications/side effects should physicians be aware of?

The most common complications associated with dermal fillers are bruising and swelling. The risks for these side effects can be decreased by icing the treatment area immediately before and after the procedure. Also, I often recommend products containing arnica (topical and/or oral) for patients who tend to bruise. Nodule formation, skin necrosis, infection, and vascular occlusion in the immediate or distal areas can be avoided with proper training and knowledge of local anatomy; for example, it’s important to always draw back before injecting to ensure you aren’t injecting into a vascular structure. Knowledge of local anatomy and its variations also is important in order to avoid these danger zones. In very rare cases, blindness and stroke may occur following treatment with dermal fillers.

Suggested Readings

Sadick N, ed. Augmentation Fillers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Small R, Hoang D. A Practical Guide to Dermal Filler Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Willams & Wilkins; 2011.

Denosumab boosts BMD in kidney transplant recipients

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients in the POSTOP trial.

Major finding: After 12 months, total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001).

Data source: POSTOP, a study of 90 patients who were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Daratumumab clinically active, well tolerated in heavily treated multiple myeloma

In patients with multiple myeloma who were treated with at least three prior therapies (median five), daratumumab demonstrated substantial clinical activity and was well tolerated, investigators reported in the Lancet.

Overall response rates were observed in 31 of 106 people (ORR 29.2%; 95% confidence interval, 20.8-38.9), stringent complete responses in 3, and very good partial responses in 10 people. In total, 87 patients (82%) had received more than three lines of therapy: all patients had been treated previously with proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, and dexamethasone. In addition, 103 (97%) were refractory to the last line of therapy before study enrollment, and 95% were refractory to the most recent proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs.

“Resistance to any previous therapy had no effect on the activity of daratumumab, lending support to a novel mechanism of action, but these findings need to be confirmed in larger studies,” wrote Dr. Sagar Lonial, executive vice chair of the department of hematology medical oncology, Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues (Lancet. 2016 Jan 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[15]01120-4).

Daratumumab was well tolerated. The most common hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade were anemia (33%), thrombocytopenia (25%), and neutropenia (23%). The overall favorable safety profile makes it a promising candidate for combination regimens, and the monoclonal IgG1 antibody has shown early activity in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, according to the researchers.

The open-label, multicenter, phase II trial included 106 patients who received daratumumab 16 mg/kg. The median time since initial diagnosis was 4.8 years (1.1-23.8 years), median number of previous therapies was 5 (2-14), and 80% of patients had received autologous stem cell transplantation.

In patients with multiple myeloma who were treated with at least three prior therapies (median five), daratumumab demonstrated substantial clinical activity and was well tolerated, investigators reported in the Lancet.

Overall response rates were observed in 31 of 106 people (ORR 29.2%; 95% confidence interval, 20.8-38.9), stringent complete responses in 3, and very good partial responses in 10 people. In total, 87 patients (82%) had received more than three lines of therapy: all patients had been treated previously with proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, and dexamethasone. In addition, 103 (97%) were refractory to the last line of therapy before study enrollment, and 95% were refractory to the most recent proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs.

“Resistance to any previous therapy had no effect on the activity of daratumumab, lending support to a novel mechanism of action, but these findings need to be confirmed in larger studies,” wrote Dr. Sagar Lonial, executive vice chair of the department of hematology medical oncology, Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues (Lancet. 2016 Jan 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[15]01120-4).

Daratumumab was well tolerated. The most common hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade were anemia (33%), thrombocytopenia (25%), and neutropenia (23%). The overall favorable safety profile makes it a promising candidate for combination regimens, and the monoclonal IgG1 antibody has shown early activity in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, according to the researchers.

The open-label, multicenter, phase II trial included 106 patients who received daratumumab 16 mg/kg. The median time since initial diagnosis was 4.8 years (1.1-23.8 years), median number of previous therapies was 5 (2-14), and 80% of patients had received autologous stem cell transplantation.

In patients with multiple myeloma who were treated with at least three prior therapies (median five), daratumumab demonstrated substantial clinical activity and was well tolerated, investigators reported in the Lancet.

Overall response rates were observed in 31 of 106 people (ORR 29.2%; 95% confidence interval, 20.8-38.9), stringent complete responses in 3, and very good partial responses in 10 people. In total, 87 patients (82%) had received more than three lines of therapy: all patients had been treated previously with proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, and dexamethasone. In addition, 103 (97%) were refractory to the last line of therapy before study enrollment, and 95% were refractory to the most recent proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs.

“Resistance to any previous therapy had no effect on the activity of daratumumab, lending support to a novel mechanism of action, but these findings need to be confirmed in larger studies,” wrote Dr. Sagar Lonial, executive vice chair of the department of hematology medical oncology, Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues (Lancet. 2016 Jan 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[15]01120-4).

Daratumumab was well tolerated. The most common hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade were anemia (33%), thrombocytopenia (25%), and neutropenia (23%). The overall favorable safety profile makes it a promising candidate for combination regimens, and the monoclonal IgG1 antibody has shown early activity in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, according to the researchers.

The open-label, multicenter, phase II trial included 106 patients who received daratumumab 16 mg/kg. The median time since initial diagnosis was 4.8 years (1.1-23.8 years), median number of previous therapies was 5 (2-14), and 80% of patients had received autologous stem cell transplantation.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Daratumumab monotherapy was clinically active and well tolerated in patients with multiple myeloma who were treated with at least three prior therapies.

Major finding: In the 16 mg/kg group, 31 of 106 patients achieved an overall response rate (ORR 29.2%; 95% confidence interval, 20.8-38.9); 3 achieved a stringent complete response; 10 achieved a very good partial response.

Data source: The open-label, multicenter, phase II trial included 106 patients who received daratumumab 16 mg/kg.

Disclosures: Janssen Research & Development contributed to the design of the study. Dr. Lonial reported ties Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Millennium, Novartis, and Onyx. Several of his coauthors reported ties to industry.

Early Invasive Strategy for Acute Coronary Syndrome May, or May Not, Improve Outcomes

Clinical question: Does an early invasive strategy for acute coronary syndrome improve short-term outcomes?

Bottom line: According to this real-world observational study, an early invasive strategy—coronary angiogram within 72 hours of presentation—is associated with lower risks of short-term cardiac death and rehospitalization for myocardial infarction (MI). However, this inference may not be valid because of a lack of key clinical information that may have influenced the data. (LOE = 2b-)

Reference: Hansen KW, Sorensen R, Madsen M, et al. Effectiveness of an early versus a conservative invasive treatment strategy in acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):737-746.

Study design: Cohort (retrospective)

Funding source: Foundation

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis: Using data from a Danish national registry, these investigators included patients aged 30 years to 90 years who were hospitalized with a first episode of unstable angina or acute MI. Patients were identified as having had an early invasive strategy (diagnostic coronary angiogram within 72 hours of hospitalization) or a conservative invasive strategy (coronary angiogram after 72 hours or no angiogram). The primary outcome was cardiac death or rehospitalization for MI within 60 days.

The investigators used propensity score matching to balance the baseline characteristics of the 2 groups in the initial cohort of 54,000 patients, resulting in 9852 matched patient-pairs. Notably, 42% of the conservative-strategy patients in the propensity-matched cohort received no cardiac catheterization. Overall, treatment with an early invasive strategy was associated with lower risks of cardiac death (5.9% vs 7.6%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; P < .001), all-cause death (7.3% vs 10.6%; NNT = 30; P < .001), and rehospitalization for MI (3.4% vs 5%; NNT = 63; P < .001).

However, as an accompanying editorial suggests, the causal inference is not necessarily valid. Given the use of an administrative database, the investigators lacked important clinical information, including indications for the angiograms performed, troponin levels, ejection fractions, and electrocardiogram findings. Without these key data, it is difficult to say whether they were comparing apples to apples, even after propensity score matching. Additionally, the study really just measures the timing of the initial angiogram without taking into account procedures done later that may have affected outcomes. As such, the validity of this study is questionable and, although the results agree with previous randomized clinical trial outcomes, it neither strengthens nor weakens what is already known.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Does an early invasive strategy for acute coronary syndrome improve short-term outcomes?

Bottom line: According to this real-world observational study, an early invasive strategy—coronary angiogram within 72 hours of presentation—is associated with lower risks of short-term cardiac death and rehospitalization for myocardial infarction (MI). However, this inference may not be valid because of a lack of key clinical information that may have influenced the data. (LOE = 2b-)

Reference: Hansen KW, Sorensen R, Madsen M, et al. Effectiveness of an early versus a conservative invasive treatment strategy in acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):737-746.

Study design: Cohort (retrospective)

Funding source: Foundation

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis: Using data from a Danish national registry, these investigators included patients aged 30 years to 90 years who were hospitalized with a first episode of unstable angina or acute MI. Patients were identified as having had an early invasive strategy (diagnostic coronary angiogram within 72 hours of hospitalization) or a conservative invasive strategy (coronary angiogram after 72 hours or no angiogram). The primary outcome was cardiac death or rehospitalization for MI within 60 days.

The investigators used propensity score matching to balance the baseline characteristics of the 2 groups in the initial cohort of 54,000 patients, resulting in 9852 matched patient-pairs. Notably, 42% of the conservative-strategy patients in the propensity-matched cohort received no cardiac catheterization. Overall, treatment with an early invasive strategy was associated with lower risks of cardiac death (5.9% vs 7.6%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; P < .001), all-cause death (7.3% vs 10.6%; NNT = 30; P < .001), and rehospitalization for MI (3.4% vs 5%; NNT = 63; P < .001).

However, as an accompanying editorial suggests, the causal inference is not necessarily valid. Given the use of an administrative database, the investigators lacked important clinical information, including indications for the angiograms performed, troponin levels, ejection fractions, and electrocardiogram findings. Without these key data, it is difficult to say whether they were comparing apples to apples, even after propensity score matching. Additionally, the study really just measures the timing of the initial angiogram without taking into account procedures done later that may have affected outcomes. As such, the validity of this study is questionable and, although the results agree with previous randomized clinical trial outcomes, it neither strengthens nor weakens what is already known.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question: Does an early invasive strategy for acute coronary syndrome improve short-term outcomes?

Bottom line: According to this real-world observational study, an early invasive strategy—coronary angiogram within 72 hours of presentation—is associated with lower risks of short-term cardiac death and rehospitalization for myocardial infarction (MI). However, this inference may not be valid because of a lack of key clinical information that may have influenced the data. (LOE = 2b-)

Reference: Hansen KW, Sorensen R, Madsen M, et al. Effectiveness of an early versus a conservative invasive treatment strategy in acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):737-746.

Study design: Cohort (retrospective)

Funding source: Foundation

Allocation: Uncertain

Setting: Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis: Using data from a Danish national registry, these investigators included patients aged 30 years to 90 years who were hospitalized with a first episode of unstable angina or acute MI. Patients were identified as having had an early invasive strategy (diagnostic coronary angiogram within 72 hours of hospitalization) or a conservative invasive strategy (coronary angiogram after 72 hours or no angiogram). The primary outcome was cardiac death or rehospitalization for MI within 60 days.

The investigators used propensity score matching to balance the baseline characteristics of the 2 groups in the initial cohort of 54,000 patients, resulting in 9852 matched patient-pairs. Notably, 42% of the conservative-strategy patients in the propensity-matched cohort received no cardiac catheterization. Overall, treatment with an early invasive strategy was associated with lower risks of cardiac death (5.9% vs 7.6%; number needed to treat [NNT] = 59; P < .001), all-cause death (7.3% vs 10.6%; NNT = 30; P < .001), and rehospitalization for MI (3.4% vs 5%; NNT = 63; P < .001).

However, as an accompanying editorial suggests, the causal inference is not necessarily valid. Given the use of an administrative database, the investigators lacked important clinical information, including indications for the angiograms performed, troponin levels, ejection fractions, and electrocardiogram findings. Without these key data, it is difficult to say whether they were comparing apples to apples, even after propensity score matching. Additionally, the study really just measures the timing of the initial angiogram without taking into account procedures done later that may have affected outcomes. As such, the validity of this study is questionable and, although the results agree with previous randomized clinical trial outcomes, it neither strengthens nor weakens what is already known.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

New guidelines update VTE treatment recommendations

Updated guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism advise abandoning the routine use of compression stockings for prevention of postthrombotic syndrome in patients who have had an acute deep vein thrombosis, according to Dr. Clive Kearon, lead author of the American College of Chest Physicians’ 10th edition of “Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease” (Chest. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026).

The VTE guidelines include 12 recommendations. Two other key changes from the previous guidelines include new treatment recommendations about which patients with isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE) should, and should not, receive anticoagulant therapy, and as a recommendation for the use of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) instead of warfarin for initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer.

It is another of the group’s “living guidelines,” intended to be flexible, easy-to-update recommendations … based on the best available evidence, and to identify gaps in our knowledge and areas for future research,” Dr. Kearon of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

“Clinicians and guideline developers would like clinician decisions to be supported by very strong, or almost irrefutable, evidence,” he said. ”It’s difficult to do studies that provide irrefutable evidence, however,” and most of the updated recommendations are not based on the highest level of study evidence – large, randomized controlled trials.

Nevertheless, “the quality of evidence that supports guidelines and clinical decision making is much better now than it was 20 or 30 years ago,” Dr. Kearon said, mainly because more recent studies are considerably larger and involve multiple clinical centers. Plus, “we’re continually improving our skills at doing high-quality studies and studies that have a low potential for bias.”

The old recommendation to use graduated compression stockings for 2 years after DVT to reduce the risk of postthrombotic syndrome was mainly based on findings of two small single-center randomized trials, published in the Lancet and Annals of Internal Medicine, in which patients and study personnel were not blinded to stocking use. Since then, a much larger multicenter, placebo-controlled trial found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce postthrombotic syndrome or have other important benefits in 410 patients with a first proximal DVT randomized to receive either active or placebo compression stockings. The incidence of postthrombotic syndrome was 14% in the active group and 13% in the placebo group – a nonsignificant difference. The same study also found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce leg pain during the 3 months after a DVT – although the stockings were still able to reduce acute symptoms of DVT, and chronic symptoms in patients with postthrombotic syndrome.

The recommendation to replace warfarin with NOACs is based on new data suggesting that the agents are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, and on observations that NOACs are much easier for patients and clinicians to use. Several of the studies upon which earlier guidelines were based have been reanalyzed, Dr. Kearon and his coauthors wrote. There are also now extensive data on the comparative safety of NOACs and warfarin.

“Based on less bleeding with NOACs and greater convenience for patients and health care providers, we now suggest that a NOAC is used in preference to VKA [vitamin K antagonist] for the initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer,” they wrote.

The recommendation to employ watchful waiting over anticoagulation in some patients with subsegmental pulmonary embolism is based on a compendium of clinical evidence rather than on large studies. A true subsegmental PE is unlikely to need anticoagulation, because it will have arisen from a small clot and thus carry a small risk of progression or recurrence.

“There is, however, high-quality evidence for the efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy in patients with larger PE, and this is expected to apply similarly to patients with subsegmental PE,” the authors wrote. “Whether the risk of progressive or recurrent VTE is high enough to justify anticoagulation in patients with subsegmental PE is uncertain.”

If clinical assessment suggests that anticoagulation isn’t appropriate, these patients should have a confirmatory bilateral ultrasound to rule out proximal DVTs, especially in high-risk locations. If a DVT is detected, clinicians may choose to conduct subsequent ultrasounds to identify and treat any evolving proximal clots.

The guideline has been endorsed by the American Association for Clinical Chemistry, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Dr. Kearon has been compensated for speaking engagements sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer Healthcare related to VTE therapy. Some of the other guideline authors also disclosed relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Updated guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism advise abandoning the routine use of compression stockings for prevention of postthrombotic syndrome in patients who have had an acute deep vein thrombosis, according to Dr. Clive Kearon, lead author of the American College of Chest Physicians’ 10th edition of “Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease” (Chest. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026).

The VTE guidelines include 12 recommendations. Two other key changes from the previous guidelines include new treatment recommendations about which patients with isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE) should, and should not, receive anticoagulant therapy, and as a recommendation for the use of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) instead of warfarin for initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer.

It is another of the group’s “living guidelines,” intended to be flexible, easy-to-update recommendations … based on the best available evidence, and to identify gaps in our knowledge and areas for future research,” Dr. Kearon of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.

“Clinicians and guideline developers would like clinician decisions to be supported by very strong, or almost irrefutable, evidence,” he said. ”It’s difficult to do studies that provide irrefutable evidence, however,” and most of the updated recommendations are not based on the highest level of study evidence – large, randomized controlled trials.

Nevertheless, “the quality of evidence that supports guidelines and clinical decision making is much better now than it was 20 or 30 years ago,” Dr. Kearon said, mainly because more recent studies are considerably larger and involve multiple clinical centers. Plus, “we’re continually improving our skills at doing high-quality studies and studies that have a low potential for bias.”

The old recommendation to use graduated compression stockings for 2 years after DVT to reduce the risk of postthrombotic syndrome was mainly based on findings of two small single-center randomized trials, published in the Lancet and Annals of Internal Medicine, in which patients and study personnel were not blinded to stocking use. Since then, a much larger multicenter, placebo-controlled trial found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce postthrombotic syndrome or have other important benefits in 410 patients with a first proximal DVT randomized to receive either active or placebo compression stockings. The incidence of postthrombotic syndrome was 14% in the active group and 13% in the placebo group – a nonsignificant difference. The same study also found that routine use of graduated compression stockings did not reduce leg pain during the 3 months after a DVT – although the stockings were still able to reduce acute symptoms of DVT, and chronic symptoms in patients with postthrombotic syndrome.

The recommendation to replace warfarin with NOACs is based on new data suggesting that the agents are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, and on observations that NOACs are much easier for patients and clinicians to use. Several of the studies upon which earlier guidelines were based have been reanalyzed, Dr. Kearon and his coauthors wrote. There are also now extensive data on the comparative safety of NOACs and warfarin.

“Based on less bleeding with NOACs and greater convenience for patients and health care providers, we now suggest that a NOAC is used in preference to VKA [vitamin K antagonist] for the initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer,” they wrote.

The recommendation to employ watchful waiting over anticoagulation in some patients with subsegmental pulmonary embolism is based on a compendium of clinical evidence rather than on large studies. A true subsegmental PE is unlikely to need anticoagulation, because it will have arisen from a small clot and thus carry a small risk of progression or recurrence.

“There is, however, high-quality evidence for the efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy in patients with larger PE, and this is expected to apply similarly to patients with subsegmental PE,” the authors wrote. “Whether the risk of progressive or recurrent VTE is high enough to justify anticoagulation in patients with subsegmental PE is uncertain.”

If clinical assessment suggests that anticoagulation isn’t appropriate, these patients should have a confirmatory bilateral ultrasound to rule out proximal DVTs, especially in high-risk locations. If a DVT is detected, clinicians may choose to conduct subsequent ultrasounds to identify and treat any evolving proximal clots.

The guideline has been endorsed by the American Association for Clinical Chemistry, the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis, and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

Dr. Kearon has been compensated for speaking engagements sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer Healthcare related to VTE therapy. Some of the other guideline authors also disclosed relationships with pharmaceutical companies.

Updated guidelines regarding the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism advise abandoning the routine use of compression stockings for prevention of postthrombotic syndrome in patients who have had an acute deep vein thrombosis, according to Dr. Clive Kearon, lead author of the American College of Chest Physicians’ 10th edition of “Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease” (Chest. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026).

The VTE guidelines include 12 recommendations. Two other key changes from the previous guidelines include new treatment recommendations about which patients with isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism (PE) should, and should not, receive anticoagulant therapy, and as a recommendation for the use of non–vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) instead of warfarin for initial and long-term treatment of VTE in patients without cancer.

It is another of the group’s “living guidelines,” intended to be flexible, easy-to-update recommendations … based on the best available evidence, and to identify gaps in our knowledge and areas for future research,” Dr. Kearon of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in an interview.