User login

Many children with COVID-19 don’t have cough or fever

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

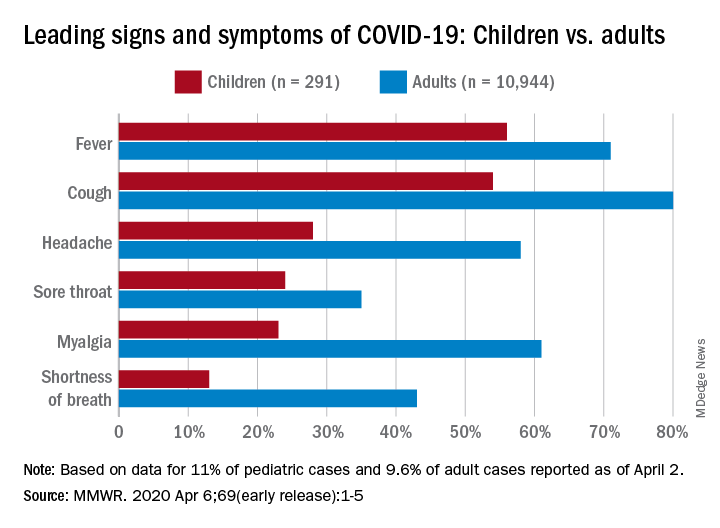

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

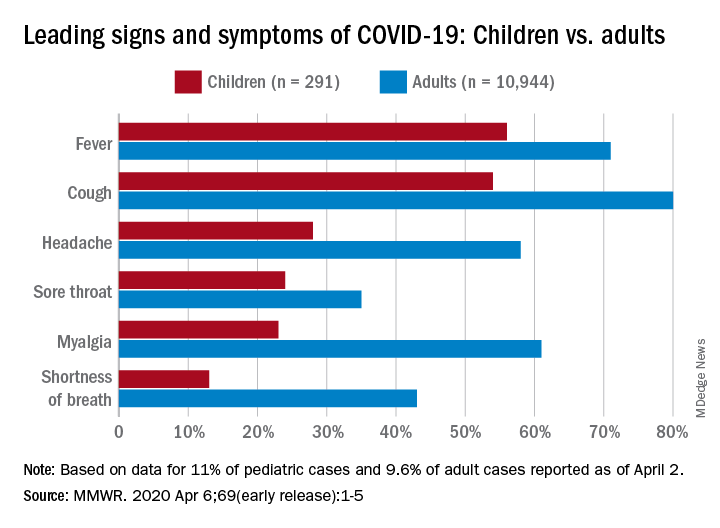

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

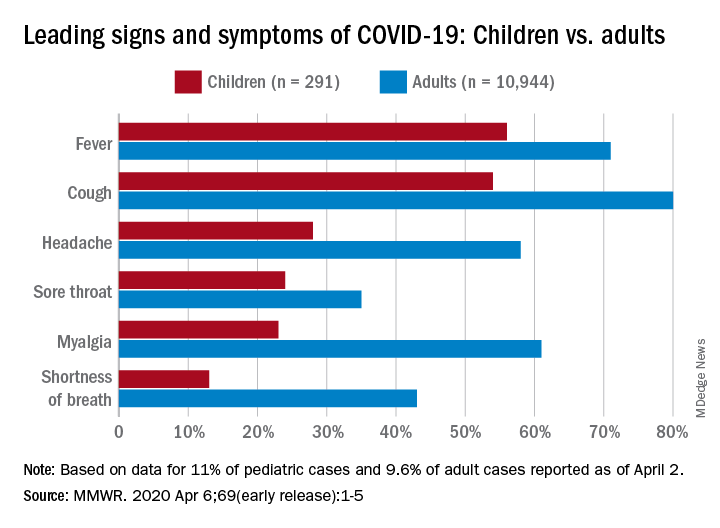

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

FROM MMWR

AAP issues guidance on managing infants born to mothers with COVID-19

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

Is protocol-driven COVID-19 respiratory therapy doing more harm than good?

Physicians in the COVID-19 trenches are beginning to question whether standard respiratory therapy protocols for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are the best approach for treating patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

At issue is the standard use of ventilators for a virus whose presentation has not followed the standard for ARDS, but is looking more like high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) in some patients.

In a letter to the editor published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine on March 30, and in an editorial accepted for publication in Intensive Care Medicine, Luciano Gattinoni, MD, of the Medical University of Göttingen in Germany and colleagues make the case that protocol-driven ventilator use for patients with COVID-19 could be doing more harm than good.

Dr. Gattinoni noted that COVID-19 patients in ICUs in northern Italy had an atypical ARDS presentation with severe hypoxemia and well-preserved lung gas volume. He and colleagues suggested that instead of high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), physicians should consider the lowest possible PEEP and gentle ventilation–practicing patience to “buy time with minimum additional damage.”

Similar observations were made by Cameron Kyle-Sidell, MD, a critical care physician working in New York City, who has been speaking out about this issue on Twitter and who shared his own experiences in this video interview with WebMD chief medical officer John Whyte, MD.

The bottom line, as Dr. Kyle-Sidell and Dr. Gattinoni agree, is that protocol-driven ventilator use may be causing lung injury in COVID-19 patients.

Consider disease phenotype

In the editorial, Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues explained further that ventilator settings should be based on physiological findings – with different respiratory treatment based on disease phenotype rather than using standard protocols.

‘“This, of course, is a conceptual model, but based on the observations we have this far, I don’t know of any model which is better,” he said in an interview.

Anecdotal evidence has increasingly demonstrated that this proposed physiological approach is associated with much lower mortality rates among COVID-19 patients, he said.

While not willing to name the hospitals at this time, he said that one center in Europe has had a 0% mortality rate among COVID-19 patients in the ICU when using this approach, compared with a 60% mortality rate at a nearby hospital using a protocol-driven approach.

In his editorial, Dr. Gattinoni disputed the recently published recommendation from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign that “mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 should be managed similarly to other patients with acute respiratory failure in the ICU.”

“Yet, COVID-19 pneumonia, despite falling in most of the circumstances under the Berlin definition of ARDS, is a specific disease, whose distinctive features are severe hypoxemia often associated with near normal respiratory system compliance,” Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues wrote, noting that this was true for more than half of the 150 patients he and his colleagues had assessed, and that several other colleagues in northern Italy reported similar findings. “This remarkable combination is almost never seen in severe ARDS.”

Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues hypothesized that COVID-19 patterns at patient presentation depend on interaction between three sets of factors: 1) disease severity, host response, physiological reserve and comorbidities; 2) ventilatory responsiveness of the patient to hypoxemia; and 3) time elapsed between disease onset and hospitalization.

They identified two primary phenotypes based on the interaction of these factors: Type L, characterized by low elastance, low ventilator perfusion ratio, low lung weight, and low recruitability; and Type H, characterized by high elastance, high right-to-left shunt, high lung weight, and high recruitability.

“Given this conceptual model, it follows that the respiratory treatment offered to Type L and Type H patients must be different,” Dr. Gattinoni said.

Patients may transition between phenotypes as their disease evolves. “If you start with the wrong protocol, at the end they become similar,” he said.

Rather, it is important to identify the phenotype at presentation to understand the pathophysiology and treat accordingly, he advised.

The phenotypes are best identified by CT scan, but signs implicit in each of the phenotypes, including respiratory system elastance and recruitability, can be used as surrogates if CT is unavailable, he noted.

“This is a kind of disease in which you don’t have to follow the protocol – you have to follow the physiology,” he said. “Unfortunately, many, many doctors around the world cannot think outside the protocol.”

In his interview with Dr. Whyte, Dr. Kyle-Sidell stressed that doctors must begin to consider other approaches. “We are desperate now, in the sense that everything we are doing does not seem to be working,” Dr. Kyle-Sidell said, noting that the first step toward improving outcomes is admitting that “this is something new.”

“I think it all starts from there, and I think we have the kind of scientific technology and the human capital in this country to solve this or at least have a very good shot at it,” he said.

Proposed treatment model

Dr. Gattinoni and his colleagues offered a proposed treatment model based on their conceptualization:

- Reverse hypoxemia through an increase in FiO2 to a level at which the Type L patient responds well, particularly for Type L patients who are not experiencing dyspnea.

- In Type L patients with dyspnea, try noninvasive options such as high-flow nasal cannula, continuous positive airway pressure, or noninvasive ventilation, and be sure to measure inspiratory esophageal pressure using esophageal manometry or surrogate measures. In intubated patients, determine P0.1 and P occlusion. High PEEP may decrease pleural pressure swings “and stop the vicious cycle that exacerbates lung injury,” but may be associated with high failure rates and delayed intubation.

- Intubate as soon as possible for esophageal pressure swings that increase from 5-10 cm H2O to above 15 cm H2O, which marks a transition from Type L to Type H phenotype and represents the level at which lung injury risk increases.

- For intubated and deeply sedated Type L patients who are hypercapnic, ventilate with volumes greater than 6 mL/kg up to 8-9 mL/kg as this high compliance results in tolerable strain without risk of ventilator-associated lung injury. Prone positioning should be used only as a rescue maneuver. Reduce PEEP to 8-10 cm H2O, given that the recruitability is low and the risk of hemodynamic failure increases at higher levels. Early intubation may avert the transition to Type H phenotype.

- Treat Type H phenotype like severe ARDS, including with higher PEEP if compatible with hemodynamics, and with prone positioning and extracorporeal support.

Dr. Gattinoni reported having no financial disclosures.

sworcester@mdedge.com

Physicians in the COVID-19 trenches are beginning to question whether standard respiratory therapy protocols for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are the best approach for treating patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

At issue is the standard use of ventilators for a virus whose presentation has not followed the standard for ARDS, but is looking more like high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) in some patients.

In a letter to the editor published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine on March 30, and in an editorial accepted for publication in Intensive Care Medicine, Luciano Gattinoni, MD, of the Medical University of Göttingen in Germany and colleagues make the case that protocol-driven ventilator use for patients with COVID-19 could be doing more harm than good.

Dr. Gattinoni noted that COVID-19 patients in ICUs in northern Italy had an atypical ARDS presentation with severe hypoxemia and well-preserved lung gas volume. He and colleagues suggested that instead of high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), physicians should consider the lowest possible PEEP and gentle ventilation–practicing patience to “buy time with minimum additional damage.”

Similar observations were made by Cameron Kyle-Sidell, MD, a critical care physician working in New York City, who has been speaking out about this issue on Twitter and who shared his own experiences in this video interview with WebMD chief medical officer John Whyte, MD.

The bottom line, as Dr. Kyle-Sidell and Dr. Gattinoni agree, is that protocol-driven ventilator use may be causing lung injury in COVID-19 patients.

Consider disease phenotype

In the editorial, Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues explained further that ventilator settings should be based on physiological findings – with different respiratory treatment based on disease phenotype rather than using standard protocols.

‘“This, of course, is a conceptual model, but based on the observations we have this far, I don’t know of any model which is better,” he said in an interview.

Anecdotal evidence has increasingly demonstrated that this proposed physiological approach is associated with much lower mortality rates among COVID-19 patients, he said.

While not willing to name the hospitals at this time, he said that one center in Europe has had a 0% mortality rate among COVID-19 patients in the ICU when using this approach, compared with a 60% mortality rate at a nearby hospital using a protocol-driven approach.

In his editorial, Dr. Gattinoni disputed the recently published recommendation from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign that “mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 should be managed similarly to other patients with acute respiratory failure in the ICU.”

“Yet, COVID-19 pneumonia, despite falling in most of the circumstances under the Berlin definition of ARDS, is a specific disease, whose distinctive features are severe hypoxemia often associated with near normal respiratory system compliance,” Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues wrote, noting that this was true for more than half of the 150 patients he and his colleagues had assessed, and that several other colleagues in northern Italy reported similar findings. “This remarkable combination is almost never seen in severe ARDS.”

Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues hypothesized that COVID-19 patterns at patient presentation depend on interaction between three sets of factors: 1) disease severity, host response, physiological reserve and comorbidities; 2) ventilatory responsiveness of the patient to hypoxemia; and 3) time elapsed between disease onset and hospitalization.

They identified two primary phenotypes based on the interaction of these factors: Type L, characterized by low elastance, low ventilator perfusion ratio, low lung weight, and low recruitability; and Type H, characterized by high elastance, high right-to-left shunt, high lung weight, and high recruitability.

“Given this conceptual model, it follows that the respiratory treatment offered to Type L and Type H patients must be different,” Dr. Gattinoni said.

Patients may transition between phenotypes as their disease evolves. “If you start with the wrong protocol, at the end they become similar,” he said.

Rather, it is important to identify the phenotype at presentation to understand the pathophysiology and treat accordingly, he advised.

The phenotypes are best identified by CT scan, but signs implicit in each of the phenotypes, including respiratory system elastance and recruitability, can be used as surrogates if CT is unavailable, he noted.

“This is a kind of disease in which you don’t have to follow the protocol – you have to follow the physiology,” he said. “Unfortunately, many, many doctors around the world cannot think outside the protocol.”

In his interview with Dr. Whyte, Dr. Kyle-Sidell stressed that doctors must begin to consider other approaches. “We are desperate now, in the sense that everything we are doing does not seem to be working,” Dr. Kyle-Sidell said, noting that the first step toward improving outcomes is admitting that “this is something new.”

“I think it all starts from there, and I think we have the kind of scientific technology and the human capital in this country to solve this or at least have a very good shot at it,” he said.

Proposed treatment model

Dr. Gattinoni and his colleagues offered a proposed treatment model based on their conceptualization:

- Reverse hypoxemia through an increase in FiO2 to a level at which the Type L patient responds well, particularly for Type L patients who are not experiencing dyspnea.

- In Type L patients with dyspnea, try noninvasive options such as high-flow nasal cannula, continuous positive airway pressure, or noninvasive ventilation, and be sure to measure inspiratory esophageal pressure using esophageal manometry or surrogate measures. In intubated patients, determine P0.1 and P occlusion. High PEEP may decrease pleural pressure swings “and stop the vicious cycle that exacerbates lung injury,” but may be associated with high failure rates and delayed intubation.

- Intubate as soon as possible for esophageal pressure swings that increase from 5-10 cm H2O to above 15 cm H2O, which marks a transition from Type L to Type H phenotype and represents the level at which lung injury risk increases.

- For intubated and deeply sedated Type L patients who are hypercapnic, ventilate with volumes greater than 6 mL/kg up to 8-9 mL/kg as this high compliance results in tolerable strain without risk of ventilator-associated lung injury. Prone positioning should be used only as a rescue maneuver. Reduce PEEP to 8-10 cm H2O, given that the recruitability is low and the risk of hemodynamic failure increases at higher levels. Early intubation may avert the transition to Type H phenotype.

- Treat Type H phenotype like severe ARDS, including with higher PEEP if compatible with hemodynamics, and with prone positioning and extracorporeal support.

Dr. Gattinoni reported having no financial disclosures.

sworcester@mdedge.com

Physicians in the COVID-19 trenches are beginning to question whether standard respiratory therapy protocols for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are the best approach for treating patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

At issue is the standard use of ventilators for a virus whose presentation has not followed the standard for ARDS, but is looking more like high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) in some patients.

In a letter to the editor published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine on March 30, and in an editorial accepted for publication in Intensive Care Medicine, Luciano Gattinoni, MD, of the Medical University of Göttingen in Germany and colleagues make the case that protocol-driven ventilator use for patients with COVID-19 could be doing more harm than good.

Dr. Gattinoni noted that COVID-19 patients in ICUs in northern Italy had an atypical ARDS presentation with severe hypoxemia and well-preserved lung gas volume. He and colleagues suggested that instead of high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), physicians should consider the lowest possible PEEP and gentle ventilation–practicing patience to “buy time with minimum additional damage.”

Similar observations were made by Cameron Kyle-Sidell, MD, a critical care physician working in New York City, who has been speaking out about this issue on Twitter and who shared his own experiences in this video interview with WebMD chief medical officer John Whyte, MD.

The bottom line, as Dr. Kyle-Sidell and Dr. Gattinoni agree, is that protocol-driven ventilator use may be causing lung injury in COVID-19 patients.

Consider disease phenotype

In the editorial, Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues explained further that ventilator settings should be based on physiological findings – with different respiratory treatment based on disease phenotype rather than using standard protocols.

‘“This, of course, is a conceptual model, but based on the observations we have this far, I don’t know of any model which is better,” he said in an interview.

Anecdotal evidence has increasingly demonstrated that this proposed physiological approach is associated with much lower mortality rates among COVID-19 patients, he said.

While not willing to name the hospitals at this time, he said that one center in Europe has had a 0% mortality rate among COVID-19 patients in the ICU when using this approach, compared with a 60% mortality rate at a nearby hospital using a protocol-driven approach.

In his editorial, Dr. Gattinoni disputed the recently published recommendation from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign that “mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 should be managed similarly to other patients with acute respiratory failure in the ICU.”

“Yet, COVID-19 pneumonia, despite falling in most of the circumstances under the Berlin definition of ARDS, is a specific disease, whose distinctive features are severe hypoxemia often associated with near normal respiratory system compliance,” Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues wrote, noting that this was true for more than half of the 150 patients he and his colleagues had assessed, and that several other colleagues in northern Italy reported similar findings. “This remarkable combination is almost never seen in severe ARDS.”

Dr. Gattinoni and colleagues hypothesized that COVID-19 patterns at patient presentation depend on interaction between three sets of factors: 1) disease severity, host response, physiological reserve and comorbidities; 2) ventilatory responsiveness of the patient to hypoxemia; and 3) time elapsed between disease onset and hospitalization.

They identified two primary phenotypes based on the interaction of these factors: Type L, characterized by low elastance, low ventilator perfusion ratio, low lung weight, and low recruitability; and Type H, characterized by high elastance, high right-to-left shunt, high lung weight, and high recruitability.

“Given this conceptual model, it follows that the respiratory treatment offered to Type L and Type H patients must be different,” Dr. Gattinoni said.

Patients may transition between phenotypes as their disease evolves. “If you start with the wrong protocol, at the end they become similar,” he said.

Rather, it is important to identify the phenotype at presentation to understand the pathophysiology and treat accordingly, he advised.

The phenotypes are best identified by CT scan, but signs implicit in each of the phenotypes, including respiratory system elastance and recruitability, can be used as surrogates if CT is unavailable, he noted.

“This is a kind of disease in which you don’t have to follow the protocol – you have to follow the physiology,” he said. “Unfortunately, many, many doctors around the world cannot think outside the protocol.”

In his interview with Dr. Whyte, Dr. Kyle-Sidell stressed that doctors must begin to consider other approaches. “We are desperate now, in the sense that everything we are doing does not seem to be working,” Dr. Kyle-Sidell said, noting that the first step toward improving outcomes is admitting that “this is something new.”

“I think it all starts from there, and I think we have the kind of scientific technology and the human capital in this country to solve this or at least have a very good shot at it,” he said.

Proposed treatment model

Dr. Gattinoni and his colleagues offered a proposed treatment model based on their conceptualization:

- Reverse hypoxemia through an increase in FiO2 to a level at which the Type L patient responds well, particularly for Type L patients who are not experiencing dyspnea.

- In Type L patients with dyspnea, try noninvasive options such as high-flow nasal cannula, continuous positive airway pressure, or noninvasive ventilation, and be sure to measure inspiratory esophageal pressure using esophageal manometry or surrogate measures. In intubated patients, determine P0.1 and P occlusion. High PEEP may decrease pleural pressure swings “and stop the vicious cycle that exacerbates lung injury,” but may be associated with high failure rates and delayed intubation.

- Intubate as soon as possible for esophageal pressure swings that increase from 5-10 cm H2O to above 15 cm H2O, which marks a transition from Type L to Type H phenotype and represents the level at which lung injury risk increases.

- For intubated and deeply sedated Type L patients who are hypercapnic, ventilate with volumes greater than 6 mL/kg up to 8-9 mL/kg as this high compliance results in tolerable strain without risk of ventilator-associated lung injury. Prone positioning should be used only as a rescue maneuver. Reduce PEEP to 8-10 cm H2O, given that the recruitability is low and the risk of hemodynamic failure increases at higher levels. Early intubation may avert the transition to Type H phenotype.

- Treat Type H phenotype like severe ARDS, including with higher PEEP if compatible with hemodynamics, and with prone positioning and extracorporeal support.

Dr. Gattinoni reported having no financial disclosures.

sworcester@mdedge.com

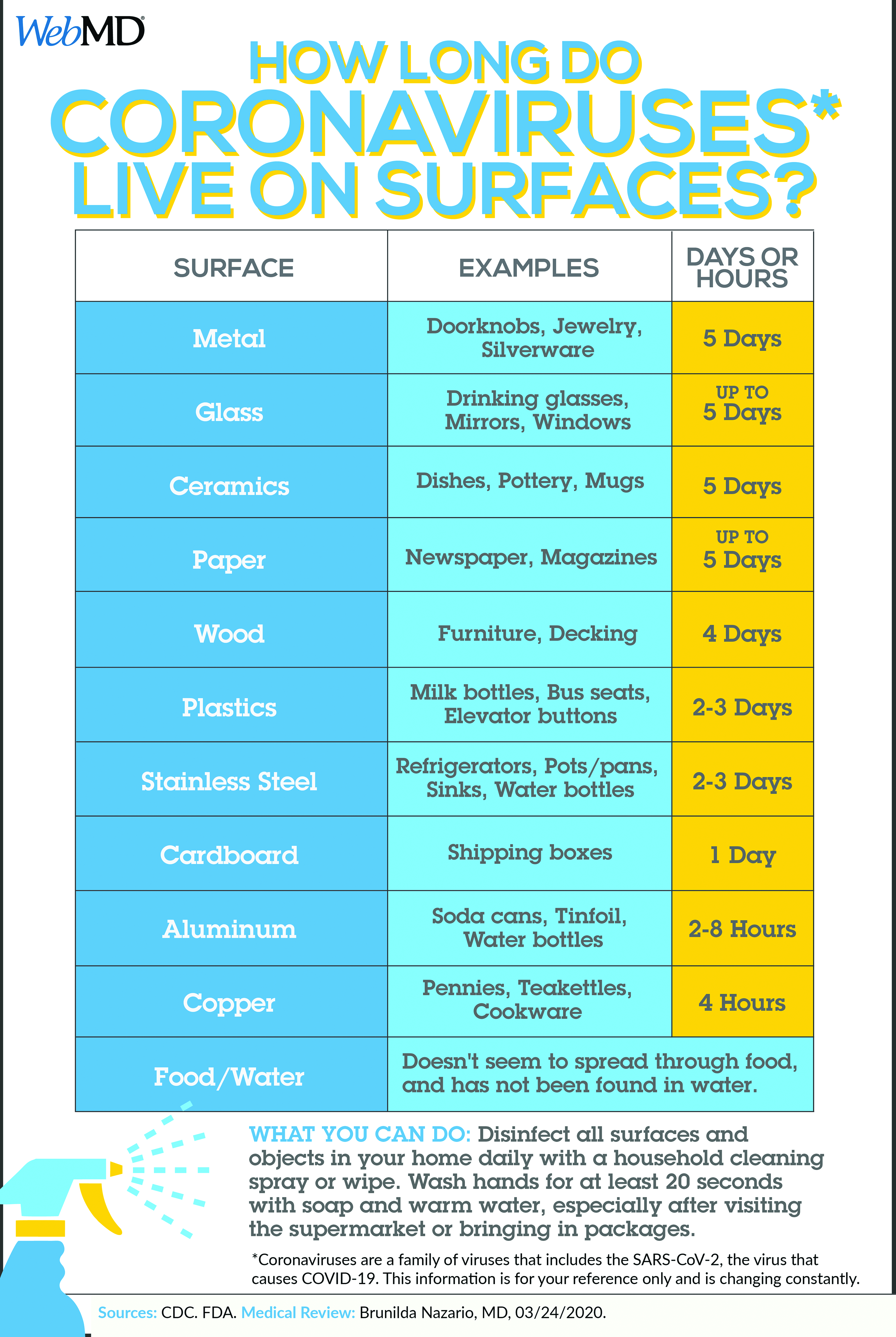

Coronavirus on fabric: What you should know

Many emergency room workers remove their clothes as soon as they get home – some before they even enter. Does that mean you should worry about COVID-19 transmission from your own clothing, towels, and other textiles?

While researchers found that the virus can remain on some surfaces for up to 72 hours, the study didn’t include fabric. “So far, evidence suggests that it’s harder to catch the virus from a soft surface (such as fabric) than it is from frequently touched hard surfaces like elevator buttons or door handles,” wrote Lisa Maragakis, MD, senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System.

The best thing you can do to protect yourself is to stay home. And if you do go out, practice social distancing.

“This is a very powerful weapon,” Robert Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, told National Public Radio. “This virus cannot go from person to person that easily. It needs us to be close. It needs us to be within 6 feet.”

And don’t forget to use hand sanitizer while you’re out, avoid touching your face, and wash your hands when you get home.

If nobody in your home has symptoms of COVID-19 and you’re all staying home, the CDC recommends routine cleaning, including laundry. Even if you go out and maintain good social distancing – at least 6 feet from anyone who’s not in your household – you should be fine.

But if you suspect you got too close for too long, or someone coughed on you, there’s no harm in changing your clothing and washing it right away, especially if there are hard surfaces like buttons and zippers where the virus might linger. Wash your hands again after you put everything into the machine. Dry everything on high, since the virus dies at temperatures above 133 F. File these steps under “abundance of caution”: They’re not necessary, but if it gives you peace of mind, it may be worth it.

Using the laundromat

Got your own washer and dryer? You can just do your laundry. But for those who share a communal laundry room or visit the laundromat, some extra precautions make sense:

- Consider social distancing. Is your building’s laundry room so small that you can’t stand 6 feet away from anyone else? Don’t enter if someone’s already in there. You may want to ask building management to set up a schedule for laundry, to keep everyone safe.

- Sort your laundry before you go, and fold clean laundry at home, to lessen the amount of time you spend there and the number of surfaces you touch, suggests a report in The New York Times.

- Bring sanitizing wipes or hand sanitizer with you to wipe down the machines’ handles and buttons before you use them. Or, since most laundry spaces have a sink, wash your hands with soap right after loading the machines.

- If you have your own cart, use it. A communal cart shouldn’t infect your clothes, but touching it with your hands may transfer the virus to you.

- Don’t touch your face while doing laundry. (You should be getting good at this by now.)

- Don’t hang out in the laundry room or laundromat while your clothes are in the machines. The less time you spend close to others, the better. Step outside, go back to your apartment, or wait in your car.

If someone is sick

The guidelines change when someone in your household has a confirmed case or symptoms. The CDC recommends:

- Wear disposable gloves when handling dirty laundry, and wash your hands right after you take them off.

- Try not to shake the dirty laundry to avoid sending the virus into the air.

- Follow the manufacturers’ instructions for whatever you’re cleaning, using the warmest water possible. Dry everything completely.

- It’s fine to mix your own laundry in with the sick person’s. And don’t forget to include the laundry bag, or use a disposable garbage bag instead.

Wipe down the hamper, following the appropriate instructions.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

Many emergency room workers remove their clothes as soon as they get home – some before they even enter. Does that mean you should worry about COVID-19 transmission from your own clothing, towels, and other textiles?

While researchers found that the virus can remain on some surfaces for up to 72 hours, the study didn’t include fabric. “So far, evidence suggests that it’s harder to catch the virus from a soft surface (such as fabric) than it is from frequently touched hard surfaces like elevator buttons or door handles,” wrote Lisa Maragakis, MD, senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System.

The best thing you can do to protect yourself is to stay home. And if you do go out, practice social distancing.

“This is a very powerful weapon,” Robert Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, told National Public Radio. “This virus cannot go from person to person that easily. It needs us to be close. It needs us to be within 6 feet.”

And don’t forget to use hand sanitizer while you’re out, avoid touching your face, and wash your hands when you get home.

If nobody in your home has symptoms of COVID-19 and you’re all staying home, the CDC recommends routine cleaning, including laundry. Even if you go out and maintain good social distancing – at least 6 feet from anyone who’s not in your household – you should be fine.

But if you suspect you got too close for too long, or someone coughed on you, there’s no harm in changing your clothing and washing it right away, especially if there are hard surfaces like buttons and zippers where the virus might linger. Wash your hands again after you put everything into the machine. Dry everything on high, since the virus dies at temperatures above 133 F. File these steps under “abundance of caution”: They’re not necessary, but if it gives you peace of mind, it may be worth it.

Using the laundromat

Got your own washer and dryer? You can just do your laundry. But for those who share a communal laundry room or visit the laundromat, some extra precautions make sense:

- Consider social distancing. Is your building’s laundry room so small that you can’t stand 6 feet away from anyone else? Don’t enter if someone’s already in there. You may want to ask building management to set up a schedule for laundry, to keep everyone safe.

- Sort your laundry before you go, and fold clean laundry at home, to lessen the amount of time you spend there and the number of surfaces you touch, suggests a report in The New York Times.

- Bring sanitizing wipes or hand sanitizer with you to wipe down the machines’ handles and buttons before you use them. Or, since most laundry spaces have a sink, wash your hands with soap right after loading the machines.

- If you have your own cart, use it. A communal cart shouldn’t infect your clothes, but touching it with your hands may transfer the virus to you.

- Don’t touch your face while doing laundry. (You should be getting good at this by now.)

- Don’t hang out in the laundry room or laundromat while your clothes are in the machines. The less time you spend close to others, the better. Step outside, go back to your apartment, or wait in your car.

If someone is sick

The guidelines change when someone in your household has a confirmed case or symptoms. The CDC recommends:

- Wear disposable gloves when handling dirty laundry, and wash your hands right after you take them off.

- Try not to shake the dirty laundry to avoid sending the virus into the air.

- Follow the manufacturers’ instructions for whatever you’re cleaning, using the warmest water possible. Dry everything completely.

- It’s fine to mix your own laundry in with the sick person’s. And don’t forget to include the laundry bag, or use a disposable garbage bag instead.

Wipe down the hamper, following the appropriate instructions.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

Many emergency room workers remove their clothes as soon as they get home – some before they even enter. Does that mean you should worry about COVID-19 transmission from your own clothing, towels, and other textiles?

While researchers found that the virus can remain on some surfaces for up to 72 hours, the study didn’t include fabric. “So far, evidence suggests that it’s harder to catch the virus from a soft surface (such as fabric) than it is from frequently touched hard surfaces like elevator buttons or door handles,” wrote Lisa Maragakis, MD, senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System.

The best thing you can do to protect yourself is to stay home. And if you do go out, practice social distancing.

“This is a very powerful weapon,” Robert Redfield, MD, director of the CDC, told National Public Radio. “This virus cannot go from person to person that easily. It needs us to be close. It needs us to be within 6 feet.”

And don’t forget to use hand sanitizer while you’re out, avoid touching your face, and wash your hands when you get home.

If nobody in your home has symptoms of COVID-19 and you’re all staying home, the CDC recommends routine cleaning, including laundry. Even if you go out and maintain good social distancing – at least 6 feet from anyone who’s not in your household – you should be fine.

But if you suspect you got too close for too long, or someone coughed on you, there’s no harm in changing your clothing and washing it right away, especially if there are hard surfaces like buttons and zippers where the virus might linger. Wash your hands again after you put everything into the machine. Dry everything on high, since the virus dies at temperatures above 133 F. File these steps under “abundance of caution”: They’re not necessary, but if it gives you peace of mind, it may be worth it.

Using the laundromat

Got your own washer and dryer? You can just do your laundry. But for those who share a communal laundry room or visit the laundromat, some extra precautions make sense:

- Consider social distancing. Is your building’s laundry room so small that you can’t stand 6 feet away from anyone else? Don’t enter if someone’s already in there. You may want to ask building management to set up a schedule for laundry, to keep everyone safe.

- Sort your laundry before you go, and fold clean laundry at home, to lessen the amount of time you spend there and the number of surfaces you touch, suggests a report in The New York Times.

- Bring sanitizing wipes or hand sanitizer with you to wipe down the machines’ handles and buttons before you use them. Or, since most laundry spaces have a sink, wash your hands with soap right after loading the machines.

- If you have your own cart, use it. A communal cart shouldn’t infect your clothes, but touching it with your hands may transfer the virus to you.

- Don’t touch your face while doing laundry. (You should be getting good at this by now.)

- Don’t hang out in the laundry room or laundromat while your clothes are in the machines. The less time you spend close to others, the better. Step outside, go back to your apartment, or wait in your car.

If someone is sick

The guidelines change when someone in your household has a confirmed case or symptoms. The CDC recommends:

- Wear disposable gloves when handling dirty laundry, and wash your hands right after you take them off.

- Try not to shake the dirty laundry to avoid sending the virus into the air.

- Follow the manufacturers’ instructions for whatever you’re cleaning, using the warmest water possible. Dry everything completely.

- It’s fine to mix your own laundry in with the sick person’s. And don’t forget to include the laundry bag, or use a disposable garbage bag instead.

Wipe down the hamper, following the appropriate instructions.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

Neurologic symptoms and COVID-19: What’s known, what isn’t

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed the first US case of novel coronavirus infection on January 20, much of the clinical focus has naturally centered on the virus’ prodromal symptoms and severe respiratory effects.

However,

“I am hearing about strokes, ataxia, myelitis, etc,” Stephan Mayer, MD, a neurointensivist in Troy, Michigan, posted on Twitter on March 26.

Other possible signs and symptoms include subtle neurologic deficits, severe fatigue, trigeminal neuralgia, complete/severe anosmia, and myalgia as reported by clinicians who responded to the tweet.

On March 31, the first presumptive case of encephalitis linked to COVID-19 was documented in a 58-year-old woman treated at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Physicians who reported the acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy case in the journal Radiology counseled neurologists to suspect the virus in patients presenting with altered levels of consciousness.

Researchers in China also reported the first presumptive case of Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) associated with COVID-19. A 61-year-old woman initially presented with signs of the autoimmune neuropathy GBS, including leg weakness, and severe fatigue after returning from Wuhan, China. She did not initially present with the common COVID-19 symptoms of fever, cough, or chest pain.

Her muscle weakness and distal areflexia progressed over time. On day 8, the patient developed more characteristic COVID-19 signs, including ‘ground glass’ lung opacities, dry cough, and fever. She was treated with antivirals, immunoglobulins, and supportive care, recovering slowly until discharge on day 30.

“Our single-case report only suggests a possible association between GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. It may or may not have causal relationship. More cases with epidemiological data are necessary,” said senior author Sheng Chen, MD, PhD.

However, “we still suggest physicians who encounter acute GBS patients from pandemic areas protect themselves carefully and test for the virus on admission. If the results are positive, the patient needs to be isolated,” added Dr. Chen, a neurologist at Shanghai Ruijin Hospital and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in China.

Neurologic presentations of COVID-19 “are not common, but could happen,” Dr. Chen added. Headache, muscle weakness, and myalgias have been documented in other patients in China, he said.

Early days

Despite this growing number of anecdotal reports and observational data documenting neurologic effects, the majority of patients with COVID-19 do not present with such symptoms.

“Most COVID-19 patients we have seen have a normal neurological presentation. Abnormal neurological findings we have seen include loss of smell and taste sensation, and states of altered mental status including confusion, lethargy, and coma,” said Robert Stevens, MD, who focuses on neuroscience critical care at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Other groups are reporting seizures, spinal cord disease, and brain stem disease. It has been suggested that brain stem dysfunction may account for the loss of hypoxic respiratory drive seen in a subset of patients with severe COVID-19 disease, he added.

However, Dr. Stevens, who plans to track neurologic outcomes in COVID-19 patients, also cautioned that it’s still early and these case reports are preliminary.

“An important caveat is that our knowledge of the different neurological presentations reported in association with COVID-19 is purely descriptive. We know almost nothing about the potential interactions between COVID-19 and the nervous system,” he noted.

He added it’s likely that some of the neurologic phenomena in COVID-19 are not causally related to the virus.

“This is why we have decided to establish a multisite neuro–COVID-19 data registry, so that we can gain epidemiological and mechanistic insight on these phenomena,” he said.

Nevertheless, in an online report February 27 in the Journal of Medical Virology, Yan-Chao Li, MD, and colleagues wrote that “increasing evidence shows that coronaviruses are not always confined to the respiratory tract and that they may also invade the central nervous system, inducing neurological diseases.”

Dr. Li is affiliated with the Department of Histology and Embryology, College of Basic Medical Sciences, Norman Bethune College of Medicine, Jilin University, Changchun, China.

A global view

Scientists observed SARS-CoV in the brains of infected people and animals, particularly the brainstem, they noted. Given the similarity of SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the researchers suggest a similar invasive mechanism could be occurring in some patients.

Although it hasn’t been proven, Dr. Li and colleagues suggest COVID-19 could act beyond receptors in the lungs, traveling via “a synapse‐connected route to the medullary cardiorespiratory center” in the brain. This action, in turn, could add to the acute respiratory failure observed in many people with COVID-19.

Other neurologists tracking and monitoring case reports of neurologic symptoms potentially related to COVID-19 include Dr. Mayer and Amelia Boehme, PhD, MSPH, an epidemiologist at Columbia University specializing in stroke and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Boehme suggested on Twitter that the neurology community conduct a multicenter study to examine the relationship between the virus and neurologic symptoms/sequelae.

Medscape Medical News interviewed Michel Dib, MD, a neurologist at the Pitié Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, who said primary neurologic presentations of COVID-19 occur rarely – and primarily in older adults. As other clinicians note, these include confusion and disorientation. He also reports cases of encephalitis and one patient who initially presented with epilepsy.

Initial reports also came from neurologists in countries where COVID-19 struck first. For example, stroke, delirium, epileptic seizures and more are being treated by neurologists at the University of Brescia in Italy in a dedicated unit designed to treat both COVID-19 and neurologic syndromes, Alessandro Pezzini, MD, reported in Neurology Today, a publication of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Pezzini noted that the mechanisms behind the observed increase in vascular complications warrant further investigation. He and colleagues are planning a multicenter study in Italy to dive deeper into the central nervous system effects of COVID-19 infection.

Clinicians in China also report neurologic symptoms in some patients. A study of 221 consecutive COVID-19 patients in Wuhan revealed 11 patients developed acute ischemic stroke, one experienced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, and another experienced cerebral hemorrhage.

Older age and more severe disease were associated with a greater likelihood for cerebrovascular disease, the authors reported.

Drs. Chen and Li have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 less severe in children, yet questions for pediatricians remain

COVID-19 is less severe in children, compared with adults, early data suggest. “Yet many questions remain, especially regarding the effects on children with special health care needs,” according to a viewpoint recently published in JAMA Pediatrics.

The COVID-19 pandemic also raises questions about clinic visits for healthy children in communities with widespread transmission and about the unintended effects of school closures and other measures aimed at slowing the spread of the disease, wrote Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, and Lindsay A. Thompson, MD, both of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

In communities with widespread outbreaks, telephone triage and expanded use of telehealth may be needed to limit nonurgent clinic visits, they suggested.

“Community mitigation interventions, such as school closures, cancellation of mass gatherings, and closure of public places are appropriate” in places with widespread transmission, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “If these measures are required, pediatricians need to advocate to alleviate unintended consequences or inadvertent expansion of health disparities on children, such as by finding ways to maintain nutrition for those who depend on school lunches and provide online mental health services for stress management for families whose routines might be severely interrupted for an extended period of time.”

Continued preventive care for infants and vaccinations for younger children may be warranted, they wrote.

Clinical course

Overall, children have experienced lower-than-expected rates of COVID-19 disease, and deaths in this population appear to be rare, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote.

Common symptoms of COVID-19 in adults include fever, cough, myalgia, shortness of breath, headache, and diarrhea, and children have similar manifestations. In adults, older age and underlying illness increase the risk of severe disease. There has not been convincing evidence of intrauterine transmission of COVID-19, and whether breastfeeding can transmit the virus is unknown, they noted.

An analysis of more than 72,000 cases from China found that 1.2% were in patients aged 10-19 years, and 0.9% were in patients younger than 10 years. One death occurred in the adolescent age range. A separate analysis of 2,143 confirmed and suspected pediatric cases in China indicated that infants were at higher risk of severe disease (11%), compared with older children – 4% for those aged 11-15 years, and 3% in those 16 years and older.

There is less data available about the clinical course of COVID-19 in children in the United States, the authors noted. But among more than 4,000 patients with COVID-19 in the United States through March 16, no ICU admissions or deaths were reported for patients aged younger than 19 years (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 26;69[12]:343-6).

Still, researchers have suggested that children with underlying illness may be at greater risk of COVID-19. In a study of 20 children with COVID-19 in China, 7 of the patients had a history of congenital or acquired disease, potentially indicating that they were more susceptible to the virus (Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718). Chest CT consolidations with surrounding halo sign was evident in half of the patients, and procalcitonin elevation was seen in 80% of the children; these were signs common in children, but not in adults with COVID-19.

“About 10% of children in the U.S. have asthma; many children live with other pulmonary, cardiac, neuromuscular, or genetic diseases that affect their ability to handle respiratory disease, and other children are immunosuppressed because of illness or its treatment,” Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “It is possible that these children will experience COVID-19 differently than counterparts of the same ages who are healthy.”

The authors reported that they had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Rasmussen SA, Thompson LA. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1224.

COVID-19 is less severe in children, compared with adults, early data suggest. “Yet many questions remain, especially regarding the effects on children with special health care needs,” according to a viewpoint recently published in JAMA Pediatrics.

The COVID-19 pandemic also raises questions about clinic visits for healthy children in communities with widespread transmission and about the unintended effects of school closures and other measures aimed at slowing the spread of the disease, wrote Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, and Lindsay A. Thompson, MD, both of the University of Florida, Gainesville.

In communities with widespread outbreaks, telephone triage and expanded use of telehealth may be needed to limit nonurgent clinic visits, they suggested.

“Community mitigation interventions, such as school closures, cancellation of mass gatherings, and closure of public places are appropriate” in places with widespread transmission, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote. “If these measures are required, pediatricians need to advocate to alleviate unintended consequences or inadvertent expansion of health disparities on children, such as by finding ways to maintain nutrition for those who depend on school lunches and provide online mental health services for stress management for families whose routines might be severely interrupted for an extended period of time.”

Continued preventive care for infants and vaccinations for younger children may be warranted, they wrote.

Clinical course

Overall, children have experienced lower-than-expected rates of COVID-19 disease, and deaths in this population appear to be rare, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Thompson wrote.

Common symptoms of COVID-19 in adults include fever, cough, myalgia, shortness of breath, headache, and diarrhea, and children have similar manifestations. In adults, older age and underlying illness increase the risk of severe disease. There has not been convincing evidence of intrauterine transmission of COVID-19, and whether breastfeeding can transmit the virus is unknown, they noted.

An analysis of more than 72,000 cases from China found that 1.2% were in patients aged 10-19 years, and 0.9% were in patients younger than 10 years. One death occurred in the adolescent age range. A separate analysis of 2,143 confirmed and suspected pediatric cases in China indicated that infants were at higher risk of severe disease (11%), compared with older children – 4% for those aged 11-15 years, and 3% in those 16 years and older.

There is less data available about the clinical course of COVID-19 in children in the United States, the authors noted. But among more than 4,000 patients with COVID-19 in the United States through March 16, no ICU admissions or deaths were reported for patients aged younger than 19 years (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Mar 26;69[12]:343-6).

Still, researchers have suggested that children with underlying illness may be at greater risk of COVID-19. In a study of 20 children with COVID-19 in China, 7 of the patients had a history of congenital or acquired disease, potentially indicating that they were more susceptible to the virus (Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718). Chest CT consolidations with surrounding halo sign was evident in half of the patients, and procalcitonin elevation was seen in 80% of the children; these were signs common in children, but not in adults with COVID-19.